Abstract

Background

Lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) may uncover incidental findings (IFs) unrelated to lung cancer. There may be potential benefits from identifying clinically significant IFs that warrant intervention and potential harms related to identifying IFs that are not clinically significant but may result in additional evaluation, clinician effort, patient anxiety, complications, and excess cost.

Objectives

To identify knowledge and research gaps and develop and prioritize research questions to address the approach to and management of IFs.

Methods

We convened a multidisciplinary panel to review the available literature on IFs detected in lung cancer screening LDCT examinations, focusing on variability and standardizing reporting, management of IFs, and evaluation of the benefits and harms of IFs, particularly cardiovascular-related IFs. We used a three-round modified Delphi process to prioritize research questions.

Results

This statement identifies knowledge gaps in 1) reporting of IFs, 2) management of IFs, and 3) identifying and reporting coronary artery calcification found on lung cancer screening LDCT. Finally, we present the panel’s initial 36 research questions and the final 20 prioritized questions.

Conclusions

This statement provides a prioritized research agenda to further efforts focused on evaluating, managing, and increasing awareness of IFs in lung cancer screening.

Keywords: lung cancer screening, incidental findings, cardiovascular disease, net benefits

Contents

Overview

Key Points

Introduction

Methods

- Results

- Section I: Prevalence of IFs in LCS

- Section II: Variability and Need for Standardizing the Reporting of IFs

- Section III: Management of IFs: Stakeholder Perspectives

- Section IV: Identifying and Reporting CAC on LCS LDCT

Conclusions

Overview

Lung cancer remains a significant global health concern, necessitating effective screening strategies for early detection. Although lung cancer screening (LCS) focuses primarily on identifying pulmonary nodules that may represent early-stage lung cancer, several studies suggest that low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) screening results in a high prevalence of incidental findings (IFs), unrelated to lung cancer, with unknown or uncertain clinical significance. An IF is defined as an imaged abnormality in a healthy asymptomatic individual or a symptomatic patient whose symptoms have no relationship with the abnormality. IFs encompass a spectrum of pulmonary and extrapulmonary abnormalities in any organ or structure imaged in a chest computed tomography (CT) scan. Understanding the clinical significance of IFs is paramount. Although many IFs may be benign and of little clinical concern, others may warrant further diagnostic investigation and management. Distinguishing between IFs that require intervention and those that can be safely monitored remains a significant challenge.

Key Points

Section I: Prevalence of IFs in LCS

The reported prevalence of IFs identified on LCS LDCT is highly variable.

Section II: Variability and Need for Standardizing the Reporting on IFs

There are no straightforward definitions of “significant” and “potentially significant” IFs identified on LCS LDCT.

There is a lack of understanding of how radiologists apply Lung Computed Tomography Screening Reporting and Data System (Lung-RADS) directives relating to IFs, including reporting of “expected” versus “unexpected” findings.

Multilevel factors contribute to the wide variability in reporting IFs.

The lack of clarity in the definition of IFs and the appropriate application of the Lung-RADS S modifier, intended to identify clinically significant or potentially clinically significant findings unrelated to lung cancer, contribute to variation and inconsistency in its use by radiologists.

There is a lack of understanding of whether the broad community of practitioners is aware of the American College of Radiology (ACR) white paper recommendations for IFs.

There is a lack of evidence addressing whether the ACR white paper recommendations for IFs are applicable to an LCS population.

There is a lack of radiologist training requirements specific to LDCT LCS interpretation overall and regarding IFs.

The Lung-RADS reporting structure may not be sufficient in all healthcare settings to identify significant IFs (SIFs) that are actionable and warrant additional workup.

There is a lack of understanding as to how the Lung-RADS recommendations for reporting expected versus unexpected IFs influence radiologists’ reporting of findings that would be anticipated in a heavy smoking–exposed population, such as emphysema.

Section III: Management of IFs: Stakeholder Perspectives

There are no data on the benefits and harms of managing and treating IFs detected on LCS.

Gaps in knowledge and areas for future research should include information about outcomes (i.e., follow-up of a particular IF likely to result in benefit or harm), decision support (do point-of-care tools to aid decision making increase benefit and reduce harm?), and shared decision making (how can patients best be engaged?).

There are limited data on ordering clinicians’ attitudes, beliefs, and preferences regarding LCS IFs, as most of the available data comes from general studies of IFs that are not specific to the LCS setting and population.

There are limited data on the consequences of IFs identified during LCS on ordering clinicians, including the impact on clinician effort and availability of resources to guide clinician decision making.

There are limited data on the consequences of IFs detected on LCS on patients, including concerns and/or expectations related to IF reporting and the availability of resources for patient education.

There are no known standardized tools for reporting and tracking LCS IFs at the healthcare system level.

There are limited data regarding resource use and cost associated with managing IFs detected on LCS and the effectiveness of evaluating IFs detected on LCS.

Section IV: Identifying and Reporting CAC on LDCT

There is a lack of clarity as to whether nongated LDCT done for LCS can provide a reliable assessment of coronary artery calcification (CAC).

There is a lack of understanding of whether currently available coronary artery calcium scoring systems can be applied reliably to LDCT performed for LCS.

There is a lack of research addressing how combined screening for lung cancer and screening for CAC might affect patient behavior, medication use, and clinical outcomes.

There is a lack of understanding as to how the Lung-RADS recommendations for reporting expected versus unexpected IFs influence radiologists’ reporting of findings that would be anticipated in a heavy smoking–exposed population, such as CAC.

Introduction

The NLST (National Lung Screening Trial) demonstrated a 20% relative reduction in lung cancer mortality in individuals who currently m or formerly smoked and were randomly assigned to three annual LCS examinations with LDCT compared with chest radiography (1). The NLST also demonstrated a reduction in all-cause mortality due to reductions in mortality from cardiovascular disease (CVD) (1). In addition, the Dutch–Belgian LCS trial (NELSON [Nederlands-Leuvens Longkanker Screenings Onderzoek]) reported reduced lung cancer mortality among high-risk individuals (2). In 2013, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended annual LDCT for LCS in individuals 55–80 years of age who currently or formerly (quit within the past 15 yr) smoked heavily (30 pack-years) (3). The 2021 modified Preventive Services Task Force LCS recommendations expanded eligibility to include adults 50–80 years of age with smoking histories of 20 pack-years (4). The estimated currently eligible population on the basis of these guidelines is 13.5 million U.S. adults (5). In addition to detecting lung cancer, the technical components of LDCT (including its cross-sectional nature, high resolution, and extensive anatomic range from the neck to the upper abdomen) allow the identification of lung and nonlung findings unrelated to lung cancer, referred to as IFs. IFs have the potential to benefit patients when an abnormality with a significant clinical consequence is detected and acted on. However, IFs also have the potential to cause harm through additional potentially unwarranted diagnostic and invasive testing, incur costs associated with testing, consume clinician effort, and trigger patient anxiety and stress.

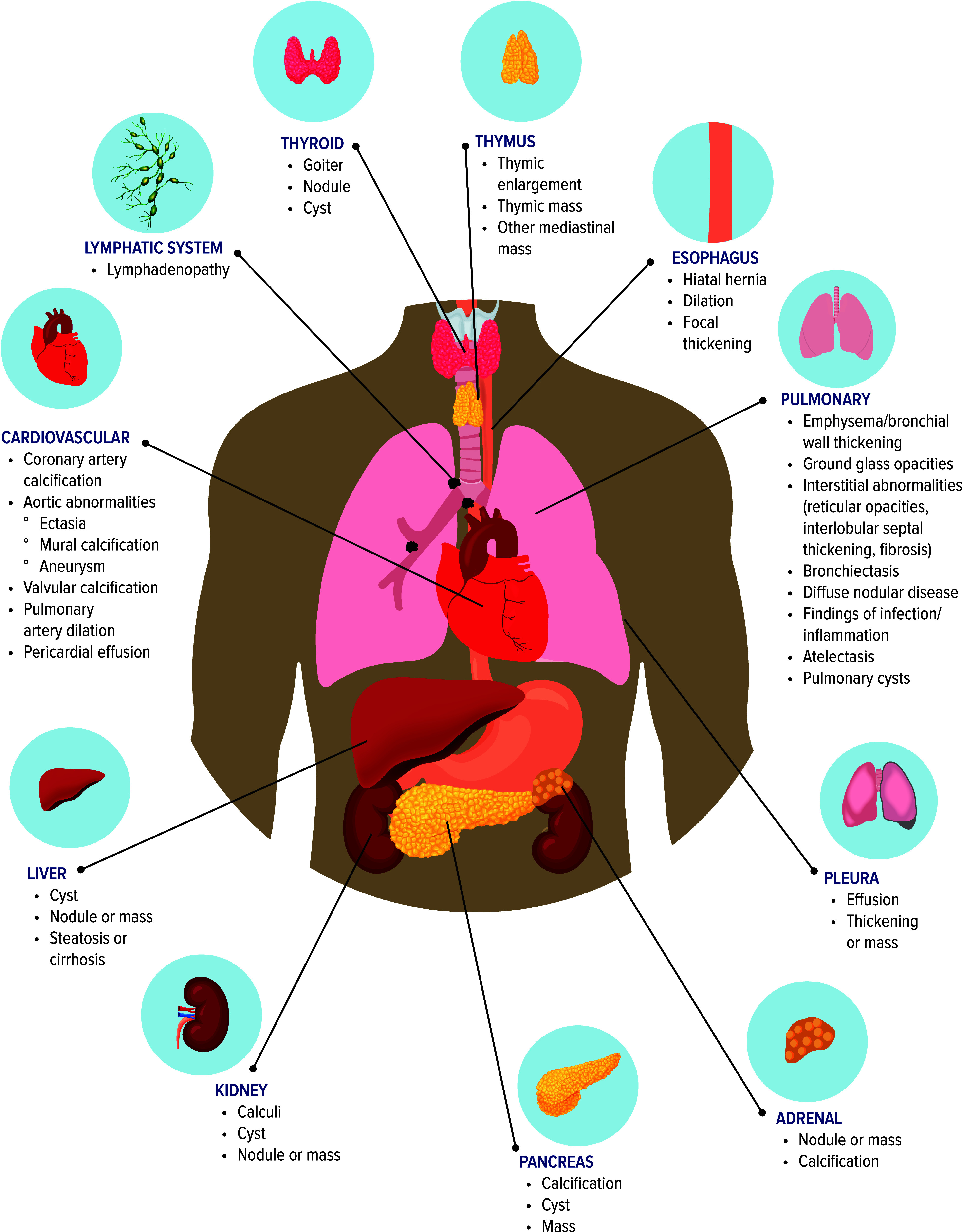

Multiple IFs are identifiable on chest CT, including CAC, thyroid nodules, adrenal nodules, aortic abnormalities, and lymphadenopathy, among many others. Beyond increasing the risk of developing lung cancer, smoking is a significant risk factor for CVD, including coronary artery disease (CAD), CAC, aortic dilation or aneurysm, and emphysema (6).

A meta-analysis of studies reporting CAC scores among participants undergoing screening LDCT found that men were 1.49 times more likely to have CAC than women. Individuals with CAC scores >0 had a higher risk of cardiovascular (CV) and all-cause mortality, with relative risks of 2.02 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.23–3.32) and 2.29 (95% CI, 1.00–5.21), respectively. CV and all-cause mortality rates were increased further in those with high CAC scores (>400 or 1,000) (7). In the NLST, CVD was the leading cause of death, accounting for 956 deaths compared with 930 deaths of lung cancer (8). The all-cause mortality reduction of LDCT versus chest radiography observed in the NLST differed by race, with significant reductions observed for Black individuals (hazard ratio [HR], 0.81 [95% CI, 0.65–1.00]) and individuals of other races (HR, 0.78 [95% CI, 0.62–0.99]) but not for White individuals (HR, 0.95 [95% CI, 0.89–1.02]) (9). Data from the NLST indicate that visual assessment and scoring of CAC on LDCT were reliable for cardiac risk stratification, mortality from CVD, and all-cause mortality (10). In addition, smoking substantially increases the risk of emphysema and multiple nonlung cancers (i.e., head and neck, esophageal, gastric, pancreatic, and colon cancers) (11). In the NLST, kidney, thyroid, or liver cancers were diagnosed in 0.39% of those in the LDCT arm (12). Thus, LDCT could play an essential role in identifying previously unknown IFs related to tobacco use, particularly CAC, and may help reduce racial disparities in healthcare outcomes, notably CVD (10).

The ACR developed Lung-RADS specifically for LCS to standardize reporting and management of lung nodules detected on LDCT (13, 14). In Lung-RADS, a radiologist may report clinically significant or potentially clinically significant non–lung cancer IFs using the S modifier (14). The ACR estimates the prevalence of the Lung-RADS S modifier at 10% (15). However, the S modifier appears to underreport Ifs, as studies have shown that radiologists may report IFs without invoking the S modifier or may inconsistently use the S modifier (16, 17). There is potential further lack of clarity, as Lung-RADS indicates that expected findings in an LCS population should not be reported with the S modifier, which could lead to variation related to individual interpretation as to whether smoking-related issues such as emphysema or CAC warrant reporting or not. Despite an established structure, Lung-RADS may not be sufficiently directive to ensure consistent use by radiologists in all healthcare settings to identify SIFs that may warrant additional workup. Moreover, identifying IFs with or without the S modifier may trigger further concern on the part of clinicians, patients, or both, resulting in potentially unwarranted evaluation or concern. Because IFs are common occurrences in many radiologic studies, the ACR Incidental Findings Committee has published several white papers to generate consistent terminology and algorithms for managing IFs detected on diagnostic imaging, including thoracic, abdominal, and pelvic CT and/or magnetic resonance imaging (18–22). These white papers address various IFs, including thyroid nodules (23), liver lesions (24), renal and adrenal masses (25, 26), pancreatic cysts (27), mediastinal lymph nodes, and CVD findings (28). In 2023, the ACR published a quick reference guide based on 12 previously published ACR white papers on IFs (29). It is important to note that IFs detected on LCS are inherently different from IFs detected outside of screening, as LCS should occur annually, and there is the ability to track IFs longitudinally. However, this highlights why guidance on the management of SIFs is important and critical, as we recognize that adherence to LCS is low, and thus we should not rely on individuals’ returning for LCS to monitor SIFs.

We developed this American Thoracic Society (ATS) research statement to determine the knowledge gaps around IFs found on LCS in the United States and worldwide to meet the needs of our members as they evaluate LCS studies and approach the management of IFs detected on LCS. We conducted systematic literature reviews, formative evaluations of existing LCS programs and their experiences with IFs, and a Delphi approach to reach consensus around the most important research questions.

Methods

We convened a multidisciplinary and international panel, including several members of the ATS Assembly on Thoracic Oncology and other experts not affiliated with the assembly (Table 1). The panel included experts in pulmonary medicine, radiology, nursing, primary care, epidemiology, screening implementation, and cardiology, with expertise in multidisciplinary lung cancer care, developing LCS programs, and managing IFs to maximize informed input and breadth of expertise. Because of panel size limitations, the panel did not include representatives from surgery subspecialities. We do not focus on SIFs relevant to specific subspecialities but instead take the approach of multidisciplinary expertise.

Table 1.

Panel Members and Expertise

| Participant | Institution, Country | Role | Discipline and Expertise |

|---|---|---|---|

| Louise M. Henderson, Ph.D. | University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, United States | Co-chair | Epidemiology; health services research; cancer screening |

| M. Patricia Rivera, M.D., A.T.S.F. | University of Rochester Medical Center, United States | Co-chair | Pulmonary medicine; lung cancer screening clinical practice and research |

| Lynn T. Tanoue, M.D. | Yale University, United States | Co-chair | Pulmonary medicine; lung cancer screening, clinical practice, research, and administration |

| Roger Y. Kim, M.D. | University of Pennsylvania, United States | Small writing group | Interventional pulmonology; epidemiology; lung cancer screening clinical practice and research |

| Nichole T. Tanner, M.D. | Medical University of South Carolina, United States | Small writing group | Pulmonary medicine; lung cancer screening clinical practice and research |

| Emily B. Tsai, M.D. | Stanford University, United States | Presenter | Cardiothoracic radiology; lung cancer screening |

| Abbie Begnaud, M.D. | University of Minnesota, United States | Presenter | Pulmonary medicine; lung cancer screening clinical practice and research |

| Farouk Dako, M.D., M.P.H. | University of Pennsylvania, United States | Presenter | Cardiothoracic radiologist; lung cancer screening clinical practice and research |

| Michael Gieske, M.D. | St. Elizabeth Healthcare Kentucky, United States | Presenter | Family medicine and PCP; lung cancer screening; incidental pulmonary nodules, policy, advocacy, research |

| Kimberly Kallianos, M.D. | University of California, San Francisco, United States | Presenter | Cardiothoracic radiologist; lung cancer screening clinical practice |

| Ilana Richman, M.D. | Yale University, United States | Presenter | Primary care; lung cancer screening research and practice |

| Lori C. Sakoda, Ph.D., M.P.H. | Kaiser Permanente Northern California, United States | Presenter | Epidemiology; lung cancer screening; health care disparities |

| Ronald G. Schwartz, M.D., M.S. | University of Rochester Medical Center, United States | Presenter | Cardiovascular disease; CVD risk assessment; primary and secondary CVD prevention |

| Joseph Yeboah, M.D. | Wake Forest University School of Medicine, United States | Presenter | Cardiovascular diseases; CVD risk assessment; primary and secondary CVD prevention |

| Kwun M. Fong, M.D. | University of Queensland, Australia | Member | Pulmonology medicine; LDCT screening and clinical practice |

| Stephen Lam, M.D. | University of British Columbia, Canada | Member | Pulmonary medicine; lung cancer screening |

| Pyng Lee, M.D. | Singapore | Member | Pulmonary medicine; lung cancer screening |

| Mary Pasquinelli, D.N.P. | University of Illinois Chicago, United States | Member | Lung screening; incidental pulmonary nodules; lung cancer clinical practice and research |

| Robert A. Smith, Ph.D. | American Cancer Society, United States | Member | Epidemiology; lung cancer screening |

| Matthew Triplette, M.D. | Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, University of Washington, United States | Member | Pulmonary medicine; lung cancer screening clinical practice, administration and research |

Definition of abbreviations: CVD = cardiovascular disease; LDCT = low-dose computed tomography; PCP = primary care provider.

Conflicts of interest were disclosed and managed according to ATS policies and procedures. The co-chairs (L.M.H., L.T.T., and M.P.R.) developed an overview of current knowledge gaps around IFs in LCS. The co-chairs conducted a literature review before drafting the proposal and updated it before the workshops. We disseminated the papers to the panel before the workshops. The speakers conducted their own literature searches before their presentations. These themes were further defined during premeeting conference calls with select panel members. We held two virtual meetings with the entire panel (August 31, 2023, and September 15, 2023), and these meetings consisted of eight presentations, three discussion sessions, and a conclusion session to expand discussions related to three overarching themes in IFs in LCS. The three themes were 1) variability in the reporting of IFs and the need for standardization of reporting; 2) management of IFs from the perspectives of stakeholders including radiologists, primary care and other clinicians ordering LDCT, patients, and healthcare systems; and 3) identifying and reporting of CAC on LDCT. A specific focus on CAC was warranted because of its high prevalence in the population eligible for LCS and the finding that CV mortality was the leading cause of death in participants in LCS trials. The discussion sessions were moderated by one co-chair, with another co-chair compiling and synthesizing the discussion in real time via screen sharing. The discussion sessions were conducted online, with the entire panel invited to attend and recordings of the sessions shared with panel members. The panel discussed knowledge gaps and research priorities around the reporting of IFs detected on LCS in session 1; management from the perspective of varied stakeholders of IFs detected on LCS in session 2; and, using CAC detected on LCS as an example, identifying the potential benefits and harms of IFs in session 3. During the conclusion session, the panel summarized the identified gaps and possible research topics. After the meetings, the co-chairs compiled a comprehensive summary of the virtual meetings’ discussions and research topics. On the basis of the synopsis and knowledge gaps, the chairs drafted 36 research questions, further refined by writing committee members (R.Y.K. and N.T.T.).

We used a modified Delphi process (30, 31) to prioritize each question, with the goal of achieving consensus through online surveys. We invited all panel members (n = 20) to participate in each round, with 100% responding in round 1, 95% responding in round 2, and 95% responding in round 3. In round 1, each panel member was asked to independently score all questions (n = 36) for importance using a 7-point scale (1 = unimportant, 2 = neither unimportant nor important, 3 = maybe important, 4 = somewhat important, 5 = important, 6 = very important, and 7 = extremely important). Questions that had ≥80% of scores with a ranking of 5 or higher (important, very important, or extremely important) were retained for round 2 (n = 20). In round 2, panel members were asked to independently rank the 20 questions using the 7-point scale. Results from round 2 indicated a lack of consensus using the 7-point scale. Given this, for round 3, all panel members were asked to rank the 20 questions from most to least important. We present the 20 prioritized research questions on the basis of the highest mean ranking (Table 2). Key points were derived via panel member consensus.

Table 2.

Research Questions by Delphi Survey Round

| Research Question | Delphi Survey Round |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 Rank | |

| Number of questions | 36 | 20 | 20 |

| Section II: Variability and standardization of reporting of IFs | |||

| Q1. What external factors may contribute to variability in IF reporting by radiologists in clinical practice (type of radiology practice, type of screening program [if any], Lung-RADS category, etc.)? | ✓ | — | — |

| Q2. What radiologist factors may contribute to variability in IF reporting (interpretation of Lung-RADS instructions for applying the S modifier, knowledge about IFs, opinions/attitudes/beliefs about expectations for reporting IFs, etc.)? | ✓ | ✓ | 13 |

| Q3. What are the facilitators and barriers to using the S modifier in reporting (Lung-RADS category 1 and 2 vs. category 3 and 4 nodule findings, radiologist training, type of radiology practice)? | ✓ | ✓ | 14 |

| Q4. What are potential educational opportunities and practical tools for improving radiologists’ use of the S modifier? | ✓ | ✓ | 15 |

| Q5. What are the facilitators and barriers to radiologists’ using the ACR IF white papers to provide recommendations for SIFs detected on LCS? | ✓ | — | — |

| Q6. What are the barriers to developing a more robust version of the ACR quick guide that incorporates the relevant ACR IF white papers, which radiologists could use for reporting and ordering clinicians to manage SIFs? | ✓ | ✓ | 20 |

| Q7. What are the barriers to radiologists examining prior records and/or imaging to identify IFs that are “de novo” vs. previously known? | ✓ | — | — |

| Q8. Should radiologists be making nonimaging follow-up recommendations for SIFs? | ✓ | ✓ | 17 |

| Q9. What is the potential role of artificial intelligence or computer-aided detection in identifying, quantifying, and reporting IFs? | ✓ | ✓ | 11* |

| Section III: Implementation of standardized reporting and impact on the management of IFs from perspectives of radiologists, primary care providers, and other ordering clinicians, patients, and the healthcare system | |||

| Q1. What are the benefits and harms of detecting, reporting, and working up IFs found on LDCT in real-world settings, and how do these differ from trial settings? | ✓ | ✓ | 2 |

| Q2. What are ordering clinician factors that may affect the management of IFs (type of clinician, understanding of the purpose of the Lung-RADS S modifier, knowledge of IFs, type of practice, degree of access to radiologists, extent of reliance on radiology recommendations for decision making, type of screening program, etc.)? | ✓ | ✓ | 8† |

| Q3. What patient factors may affect the management of IFs (age, comorbid conditions, experience with lung cancer screening, patient access to reports, patient knowledge of IFs, beliefs, type of screening program, etc.) (may need qualitative/mixed methods evaluation)? | ✓ | ✓ | 10 |

| Q4. What health system factors may affect the management of IFs (type of screening program, degree of patient access to reports, etc.)? | ✓ | — | — |

| Q5. Does using the Lung-RADS category S modifier have a significant association with the follow-up of SIFs? | ✓ | ✓ | 3 |

| Q6. Does reporting of IFs with or without the S modifier influence clinical outcomes? | ✓ | — | — |

| Q7. What are the potential benefits and harms/burdens imposed on radiologists by reporting SIFs? | ✓ | — | — |

| Q8. What are the potential benefits and harms/burdens imposed on ordering clinicians by reporting SIFs? | ✓ | — | — |

| Q9. What are the potential benefits and harms/burdens imposed on patients by reporting SIFs? | ✓ | ✓ | 1 |

| Q10. What are the potential benefits and harms/burdens imposed on health systems by reporting SIFs? | ✓ | — | — |

| Q11. What is the best approach for radiologists and clinicians ordering LDCT to communicate IFs to one another and to patients? | ✓ | ✓ | 5 |

| Q12. What tools are available to clinicians to facilitate discussions with patients about IFs efficiently? | ✓ | ✓ | 16 |

| Q13. Do radiologists phrase recommendations differently according to the type of clinician who ordered the LDCT, and what impact does this have on downstream care/outcomes? | ✓ | — | — |

| Q14. What are the impacts of providing feedback to interpreting radiologists about IFs detected on LCS? For example, does feedback encourage better adherence to reporting guidelines? | ✓ | ✓ | 19 |

| Q15. For SIFs, what is the correlation between the ACR quick reference guide and actionable findings vs. the European Society of Radiologists and European Respiratory Society recommendations? | ✓ | — | — |

| Q16. What is the understanding of ordering clinicians regarding the likelihood that IFs and SIFs will be identified on lung cancer screening LDCT? | ✓ | — | — |

| Q17. Does fear of the discovery of SIFs prevent clinicians from ordering LDCT? Has this concern lessened over the years as familiarity with lung cancer screening has improved? | ✓ | — | — |

| Q18. What are the strengths/limitations (better communication or hindrance for patients receiving care in multiple systems) of a healthcare system–wide EHR-based IF solution in clinical care? | ✓ | — | — |

| Q19. What is the role of a multidisciplinary care team in the context of managing IFs detected on LCS? | ✓ | ✓ | 18 |

| Q20. What is the best approach to incorporating information about IFs detected on LDCT into SDM or tobacco treatment discussions? | ✓ | — | — |

| Q21. What factors should be included when evaluating health system–wide resource needs and associated costs to manage SIFs? | ✓ | — | — |

| Section IV: Detection of CAC on LDCT LCS and the potential impact on racial disparities | |||

| Q1. Does the presence or absence of CAC on LCS LDCT influence cardiac management decisions made by ordering clinicians? | ✓ | ✓ | 8† |

| Q2. Is coronary calcium scoring reliably achievable on LCS LDCT? If so, can LCS LDCT serve a dual purpose for coronary calcium scoring? If so, what are the potential benefits and harms? | ✓ | ✓ | 4 |

| Q3. Considering the variability in methods and software costs, what strategies can be used to standardize CAC evaluation on LDCT? | ✓ | ✓ | 6 |

| Q4. If CAC does not improve discrimination in this population, is there harm associated with reporting zero CAC? Especially if everyone undergoing LDCT is essentially high risk anyway? | ✓ | — | — |

| Q5. Does reporting the presence or absence of CAC on LCS LDCT influence the behavior of patients (tobacco cessation, other cardiac prevention interventions, adherence to LCS, etc.)? | ✓ | ✓ | 11* |

| Q6. Given racial disparities in CVD incidence and mortality (with Black individuals having worse outcomes than White individuals), will detection and possible treatment of CAC increase or reduce these differences? | ✓ | ✓ | 7 |

Definition of abbreviations: ACR = American College of Radiology; CAC = coronary artery calcification; CVD = cardiovascular disease; EHR = electronic health record; IF = incidental finding; LCS = lung cancer screening; LDCT = low-dose computed tomography; Lung-RADS = Lung Computed Tomography Screening Reporting and Data System; SDM = shared decision making; SIF = significant incidental finding.

Checkmarks indicates questions included in the indicated round of voting.

Tie for 11th.

Tie for eighth.

Results

In this section, we summarize the relevant literature, present the knowledge gaps and research opportunities identified by the panel, and provide the proposed research question needs.

Section I: Prevalence of IFs in LCS

A retrospective analysis of 17,309 of the 26,455 participants undergoing LDCT in the NLST identified that 59% had extrapulmonary IFs reported, and 20% had potentially clinically significant extrapulmonary IFs detected (32). CVD abnormalities were the most common, with 8% of participants identified as having potentially significant CVD IFs and 15% as having potentially significant or minor CVD IFs. A separate study of 25,002 participants in the LDCT-screened arm of the NLST evaluating the prevalence of pulmonary IFs reported that 44% had radiographic findings of emphysema, while 37% had reticular or reticulonodular opacities, honeycombing, fibrosis, or scar (33). The most complete study of IFs in the NLST was a retrospective review of all 26,455 participants in the LDCT invited screening arm (34). Pulmonary and extrapulmonary IFs were identified by an expert radiology panel reviewing participant case reports and were classified according to published ACR white papers on managing IFs (23–25, 27, 28). During the trial, 4% of participants had significant or potentially SIFs on at least one screening examination, with 89% of these considered reportable to the referring clinician. Furthermore, 18% of all LDCT examinations had at least one SIF. The prevalence of SIFs was higher in participants with positive screen results for lung cancer (45%) compared with those with negative results (10%). Pulmonary findings were the most common SIFs, with 43% of participants reported as having evidence of emphysema, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or hyperinflation, followed by CAC in the absence of evidence of a prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery or coronary artery stent (12%) and masses or suspicious lesions (7%). Lower rates of SIFs were reported in the NELSON trial: 2,060 IFs were identified among 1,929 participants, with 8% considered clinically relevant (35). The Italian COSMOS (Continuous Observation of Smoking Subjects) study reported 436 potentially SIFs in 5,201 subjects (8%) (36).

As LCS has been implemented into clinical practice, the reported real-world prevalence of IFs has been widely variable. In the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs demonstration project, 41% of screened individuals were reported to have IFs (37). In a centralized LCS program in a large healthcare system, 94% of screened individuals had at least one IF reported, with the most common being in the respiratory (70%) and CV systems (68%), with 15% resulting in further evaluation (38). In a study of a decentralized LCS program with academic and community imaging sites, the prevalence of SIFs was 67% and 27%, respectively, with CAC (29% and 17%) being the most common (39). At a single-center LCS program in an academic medical center, 49% of screened individuals had SIFs reported, but a retrospective review of IFs estimated that the true prevalence was as high as 69% (17).

On the basis of the evaluation of participants in the LDCT screening arm of NLST and the published experience of LCS programs after implementation, SIFs occur with a prevalence that appears to be substantially higher than the 10% estimate anticipated in the ACR Lung-RADS reporting structure.

Section II: Variability and Need for Standardizing the Reporting of IFs

The wide variability in the reporting of IFs in general and Lung-RADS category S findings in particular highlights recognition that the actual prevalence of clinically significant IFs identified through LCS is unclear. Moreover, it is unknown whether the discovery of meaningful clinical diseases, identified as SIFs, benefits patients from earlier diagnosis. Furthermore, inconsistent use of the S modifier will make it very difficult to reliably answer both questions. This highlights the importance of identifying and reporting using the Lung-RADS S modifier and providing guidance for IFs that are significant. Insufficient reporting may lead to underrecognition and undertreatment of clinically relevant diseases, with attendant harm. Overreporting nonsignificant IFs may provoke anxiety in clinicians and patients and trigger further avoidable evaluation with inherent risks and potential harms. In either case, such inaccuracies may result in added burden and cost to healthcare systems.

The ACR and other professional societies have committed to providing clinicians with recommendations for managing organ-specific IFs. These guidelines are often aligned among societies, yet in some cases, they differ. For LCS specifically, the population of patients eligible for screening has heavy smoking exposure and a high prevalence of comorbid conditions related to smoking, which are often not taken into consideration by societal guidelines (29).

The published experiences of real-world LCS programs suggest that the reporting of IFs on LDCT scans is highly variable. An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies identified considerable heterogeneity in reporting IFs among studies (40). In addition, radiologists’ application of the Lung-RADS S modifier in reporting appears inconsistent. In a prospective study of 4,492 baseline LCS LDCT examinations performed at six predominantly community settings (69%) and interpreted mainly by radiologists without fellowship training in cardiothoracic imaging (81%), the Lung-RADS S modifier was reported and/or an IF-specific follow-up recommendation was given in 17% of scans (16). In 3% of LDCT reports, the S modifier was used, and IF-specific follow-up recommendations were given; in 10% of reports, the S modifier was used, but no IF-specific follow-up was given; and in 4% of reports, the S modifier was not used, but IF-specific follow-up recommendations were given. Moreover, this study revealed that the use of the S modifier and recommendations for follow-up varied according to Lung-RADS categories (categories 1–4) and facility type (academic vs. community). In another study of 901 individuals undergoing baseline LCS in a single Department of Veterans Affairs system, IFs were reported in 94% of all studies, with retrospective chart review identifying SIFs in 786 scans (34%) (41). In 37% of the latter group, the S modifier had been invoked, and radiologist recommendations for the SIFs were made in 52% of individuals. Of note, there was substantial variation among the 11 radiologists included in the study relating to the use of the S modifier (0–51% of all examinations read), number of SIFs reported (0–75%), and provision of recommendations (34–69%).

The wide variability in reporting IFs and in using the S modifier likely reflects multiple factors, which include but are not limited to the following:

The definition of the S modifier in Lung-RADS is vague, as it does not include a functional explanation of significant or potentially significant. This leaves the interpretation of when to apply the modifier to the individual reporting radiologist.

The array of potential organ-specific IFs discoverable on LDCT is extensive (Figure 1). It is unrealistic to expect that radiologists and/or referring clinicians can independently manage the burden of work necessary to address all IFs optimally without a system of shared responsibility, clearer evaluation protocols, and a multidisciplinary team approach.

For many IFs, ACR and other societal guidelines for reporting, evaluation and management exist, but they are separate, stand-alone documents that are periodically updated. It is not realistic or feasible to expect radiologists and/or referring clinicians to independently keep up to date with all such guidelines.

There is no specific ACR white paper to guide the reporting of IFs on LDCT for LCS.

Figure 1.

Incidental findings found on lung cancer screening.

The definition of the S modifier in Lung-RADS further includes the statement, “Findings that are already known and have been or are in the process of clinical evaluation DO NOT require an S-modifier.” Radiologists may consider IFs such as emphysema or CAC as expected and/or already known in a heavily smoking population, as opposed to incidental, which may influence reporting (15, 41). This is especially true in scenarios in which there are prior imaging studies demonstrating the IFs. This further assumes that diseases evident radiographically, such as emphysema and CAC, are known to the clinician and the patient, which may not be the case. At present, there is no recommendation to screen asymptomatic individuals who smoke or who ever smoked for the presence of emphysema. If an individual being screened for lung cancer is found to have emphysema on imaging, 1) the radiologist reporting the LDCT findings is unlikely to know whether there is a prior clinical history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and 2) the clinician caring for the individual might elect to quantify the severity of the emphysema by physiologic testing if not already done. IFs such as CAC or emphysema with expected high prevalence in a population with a history of heavy smoking are difficult to characterize because of the lack of standardized approaches to severity scoring, even when validated approaches and/or guidelines may be available (10, 42). If all CAC, regardless of severity, were considered significant and assigned an S modifier, then the prevalence of CAC reported as a SIF would be very high. If only severe CAC, as determined by using an available scoring system, is considered clinically significant, then the prevalence of CAC reported as a SIF would be much lower, and the opportunity to intervene early in the course of CAD may be lost. If CAC is regarded as an expected finding instead of an IF, as might be assumed in a population with heavy smoking exposure, CAC of any severity would never be reported.

Knowledge gaps and research opportunities

There is a lack of straightforward definitions of SIFs identified on LCS LDCT. This contributes to the variation observed in the reporting of SIFs and emphasizes the need for a standardized definition of IFs that are clinically significant and warrant the application of the Lung-RADS S modifier. There is also a knowledge gap in how radiologists apply the directives of Lung-RADS relating to IFs, including the reporting of expected versus unexpected findings and the consistency with which the recommendations of the ACR white papers or other professional societal guidelines are provided by the radiologist to the ordering clinician. Although the current literature identifies wide variation in IF reporting and use of the S modifier, it is impossible to know the extent of variation or to measure the quality of interventions if no universal standard exists. This problem is further compounded by the lack of standardized severity scoring systems for conditions such as emphysema that may be common in an LCS population or for conditions such as CAC, where several validated severity scoring systems exist but without a consensus as to which system should be used for LDCT done in the context of LCS (see Section III).

The European Society of Radiology and the European Respiratory Society provide a general definition of a “clinically significant” finding as having a major or adverse clinical impact or for which there is an established intervention that benefits the patient (43, 44). The American College of Chest Physicians updated guideline for LCS offers potential categorizations of clinical relevance for nonnodule IFs (45). There is a pressing need for structured reporting of IFs that will clearly distinguish those that are potentially clinically significant from those that are not, improve the consistency and accuracy of reporting by radiologists, and provide clarity and direction for referring clinicians and patients. This expectation highlights the potential need for LCS-specific radiologist training and minimum interpretation volumes, a model established by the Mammography Quality Standards Act for breast cancer screening (46, 47). Standardization of classification, reporting, and management of IFs has enormous potential to improve the clarity of written communication and clinical care. Moreover, establishing standards will help facilitate research to understand the potential benefits and value and the risks and harms of IFs identified during LCS.

Prioritized research questions

Of the initial nine questions in Sections I and II, voting results indicated that the following questions were the highest priority (Table 2):

Section II, Q2: What radiologist factors may contribute to variability in IF reporting (interpretation of Lung-RADS instructions for applying the S modifier, knowledge about IFs, opinions/attitudes/beliefs about expectations for reporting IFs, etc.)?

Section II, Q3: What are the facilitators and barriers to using the S modifier in reporting (Lung-RADS category 1 and 2 vs. category 3 and 4 nodule findings, radiologist training, type of radiology practice)?

Section II, Q4: What are potential educational opportunities and practical tools for improving radiologists’ use of the S modifier?

Section II Q6: What are the barriers to developing a more robust version of the ACR quick guide that incorporates the relevant ACR IF white papers, which radiologists could use for reporting and ordering clinicians to manage SIFs?

Section II, Q8: Should radiologists be making nonimaging follow-up recommendations for SIFs?

Section II, Q9: What is the potential role of artificial intelligence or computer-aided detection in identifying, quantifying, and reporting IFs?

Section III: Management of IFs: Stakeholder Perspectives

As noted above, the ACR Lung-RADS lexicon has been widely adopted and is intended to standardize clinical reporting and management of LDCT findings from LCS. However, the use of the S modifier has yet to be standardized across systems because of a lack of agreement on what is clinically significant or potentially clinically significant. This variation is driven by 1) what an individual radiologist may determine and identify as clinically significant or insignificant, 2) what the end-using clinician decides is clinically significant or insignificant, and also potentially 3) what the patient’s response is to reading about IFs in the LDCT report.

IIIa. The radiologist’s perspective

As radiologic images contain many findings, some of which may not be relevant to the care of the patient, the radiologist may include only some IFs in the report and must use clinical judgment and experience to limit what is reported to clinically actionable IFs. The challenge for radiologists is not in identifying IFs but rather in avoiding “underreporting” or “overreporting” such that IFs that are unlikely to be relevant to the patient’s management are identified and documented. There are currently differing opinions on the extent to which radiologists should tailor reporting to draw attention to those findings where clinically impactful interventions are available or if all IFs present on imaging should be described in the LDCT LCS report even though they may lead to potentially unnecessary investigations or generate anxiety in patients. Lung-RADS recommends that the interpreting radiologist include SIFs that warrant attention, with recommended follow-up, in the “impression” section of the report (13). In addition, the extent to which IFs should be documented once at first occurrence or documented at each annual screening examination even if there is no progression has not been assessed.

The ACR recently published a quick reference guide based on 12 previously published ACR white papers on IFs (29). It is important to note that this guide is meant for use by LCS program coordinators and nurse navigators. The ACR quick reference guide refers explicitly to the use of the Lung-RADS S modifier to indicate actionable IFs, but within the guide, there are many IFs for which there is no specific management recommendation. Of note, the ACR guide recommends reporting of CAC detected on LDCT and suggests referral to a primary care physician (PCP) or a cardiologist for further assessment. Reliably using and including ACR quick reference guide recommendations into LCS LDCT reporting could help interpreting radiologists provide guidance to clinicians ordering LDCT. Given its recent publication, implementation efforts in practice and impact on management decisions are unknown.

One area of interest to radiologists is the potential role of automation in detecting IFs, particularly related to the detection and quantification of CAC, emphysema, pulmonary fibrosis, aortic size, and thoracic aortic aneurysm. These IFs are more common in an LCS population and have potential clinical actionability that may lead to improved patient outcomes. Algorithms or programs to reduce radiologists’ burden of identification and reporting would be helpful.

IIIb. The PCP perspective

Prior work has more broadly focused on PCP management and perceptions of IFs identified by any imaging modality without a specific focus on those found during LCS. Although some of the themes identified likely translate to LCS, there may be unique aspects of IFs detected on LCS. Regarding IFs in general, PCPs report anxiety, frustration, and time wasted. PCPs also tend to follow up on IFs even when they do not believe them to be clinically important, because of community norms, concern about litigation, advice from other doctors, and patient requests (48). A qualitative study of 30 PCPs focused on IFs identified patient-level characteristics (i.e., patient age, life expectancy, patient anxiety, health literacy, insurance status) and physician comfort and experience as factors influencing decisions to follow-up IFs (49). One qualitative study of 15 PCPs focused on primary care perceptions and barriers to managing IFs detected on LCS (50). The themes that emerged included the following:

Concern that inadequate information was provided in reporting about the probability that an IF was either malignant or clinically significant.

Concern about loss to follow-up and harm to patients.

Belief that current systems for tracking patients are inadequate and that health systems should develop these tracking and monitoring systems.

Concern that primary care clinicians may communicate the type and timing of follow-up needed for incidentally detected pulmonary nodules rather than discuss options and engage in shared decision making with patients. The same may be occurring in communication regarding noncancer IFs detected on LDCT.

IIIc. The patient’s perspective

There is a dearth of knowledge relating to patients’ perspectives on IFs detected on LCS. Several studies have explored patients’ perspectives on pulmonary nodules found on chest imaging but are not specific to the screening setting (51–55). Although pulmonary nodules discovered during LCS are not IFs per se, the discovery of nodules shares common features with other kinds of IFs. For example, nodules may be of uncertain etiology, require follow-up, and may be surprising. There is a lack of work focused on patient-centered outcomes or the financial burden associated with IF.

IIId. The healthcare system perspective

Detecting and managing IFs is an important component of a high-quality LCS program, the goal of which is to maximize effectiveness and minimize inefficiencies, all while leveraging available finite resources. From the healthcare system perspective, there is a need to understand the magnitude and downstream impact of IF detection and reporting to identify the best approaches to support management. Data on resource needs and costs associated with managing IFs detected on LCS are relatively sparse. The Cleveland Clinic LCS program found that nearly half of the per-patient reimbursement for LCS is related to the evaluation and treatment of IFs (38). In contrast, the Italian LCS trial reported that the average per-patient cost of radiologic follow-up for IFs is relatively modest (56). These differences are likely due to variations in the definition and management of IFs, highlighting the need to establish standards and international exchange on best practices to improve efficiency and patient outcomes. Standardized reporting that consistently distinguishes clinically significant IFs from those that are insignificant or do not warrant additional follow-up will allow more reliable measurement and comparisons of potentially avoidable resource use and costs. From a learning healthcare system perspective, evidence is critical to promoting effective management of IFs in LCS (57). More important, evolving evidence-based best practices in the management of IFs need timely, widespread dissemination across healthcare systems.

IIIe. Benefits and harms of IFs detected on LCS

The long-term outcomes of clinically significant IFs detected on LCS are relatively unknown. In an evaluation of a single-center, community-based, nonacademic LCS program, the rate of invasive procedures and complications was low among the 3,771 individuals screened. Specifically, invasive procedures were performed in 1.7% of those screened who had benign disease. Invasive procedures were performed in 19 individuals (>1% of those screened) for IFs considered benign but clinically important, and medical management was changed in up to 68%, suggesting a benefit (58).

Knowledge gaps and research opportunities

Large-scale population data on the benefits and harms of detecting, managing, and treating IF detected on LCS are lacking. Gaps in knowledge and areas for future research include the following:

Radiologist perceptions, facilitators, and barriers to IF reporting have yet to be evaluated in detail.

There are limited data on ordering clinicians’ attitudes, beliefs, and preferences around IFs specifically detected on LCS; most of the available data come from studies of IFs identified on all diagnostic imaging.

Patient preferences around the communication and workup of IFs detected on LCS are poorly understood.

There is a lack of standardized tools at the healthcare system level for reporting and tracking the follow-up of LCS IF.

There is a need to evaluate downstream specialist consultation, diagnostic testing, invasive procedures, and patient-level outcomes to assess if detection, reporting, and follow-up of a particular IF will likely result in benefit or harm.

There is a need to evaluate how patients can best be engaged in the decision-making process relating to IFs identified through LCS. There is a need to develop and evaluate point-of-care tools to aid that process that can be studied from the perspective of potential benefit and harm.

Prioritized research questions

Of the initial 21 questions in Section III, voting results indicated that the following questions were the highest priority (Table 2):

Section III, Q1: What are the benefits and harms of detecting, reporting, and working up IFs found on LDCT in real-world settings, and how do these differ from trial settings?

Section III, Q2: What are ordering clinician factors that may affect the management of IFs (type of clinician, understanding of the purpose of the Lung-RADS S modifier, knowledge of IFs, type of practice, degree of access to radiologists, extent of reliance on radiology recommendations for decision making, type of screening program, etc.)?

Section III, Q3: What patient factors may affect the management of IFs (age, comorbid conditions, experience with LCS, patient access to reports, patient knowledge of IFs, beliefs, type of screening program, etc.) (may need qualitative/mixed methods evaluation)?

Section III, Q5: Does using the Lung-RADS category S modifier have a significant association with the follow-up of SIFs?

Section III, Q9: What are the potential benefits and harms/burdens imposed on patients by reporting SIFs?

Section III, Q11: What is the best approach for radiologists and clinicians ordering LDCT to communicate IFs to one another and to patients?

Section III, Q12: What tools are available to clinicians to facilitate discussions with patients about IFs efficiently?

Section III, Q14: What are the impacts of providing feedback to interpreting radiologists about IFs detected on LCS? For example, does feedback encourage better adherence to reporting guidelines?

Section III, Q19: What is the role of a multidisciplinary care team in the context of managing IFs detected on LCS?

Section IV: Identifying and Reporting CAC on LCS LDCT

The identification of CAC as an IF on LDCT LCS is somewhat unique in that, in contrast to other common IFs such as emphysema or interstitial lung abnormalities, screening for CAC with CT in asymptomatic individuals has had considerable uptake in clinical practice. This raises the interesting possibility that, given the common risk factor of smoking, LDCT LCS may present an opportunity to screen for both lung cancer and CAC.

About half of deaths related to CVD occur in individuals who have no histories of heart disease or clinical symptoms, underscoring the critical need for accurate risk assessment in individuals without symptoms (59, 60). Initial clinical evaluation for CVD risk involves identifying established atherosclerotic CVD and diabetes requiring treatment. If these conditions are absent, other risk factors should be evaluated, using either the Pooled Cohort Equations (in the United States) or the Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation (in Europe), to estimate the 10-year risk of CVD, categorizing individuals as high, borderline, intermediate, or low risk (59, 61). The intermediate-risk category poses a challenge, as it requires a careful balance between the potential benefits of preventive therapy and the associated costs and adverse effects imposed on the patient.

Detection of CAC on CT scans is important to stratifying CV risk (61, 62), as it serves as an indicator of atherosclerotic burden and helps estimate the likelihood of CAD that might warrant intervention such as antiplatelet therapy and risk factor modification including intensive low-density lipoprotein lowering to <55 mg/dl per current guidelines (63, 64). Furthermore, CAC independently predicts the risk of major CV events and is linked to both all-cause and cardiac mortality (65). According to the 2019 American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association guidelines, CAC receives a class 2a recommendation for use alongside clinical risk assessment in asymptomatic individuals with intermediate 10-year atherosclerotic CVD risk (64). Similarly, the 2019 European Society of Cardiology guidelines for dyslipidemia management give a class 2a recommendation for CAC testing in asymptomatic individuals with low or intermediate CVD risk (63). Moreover, the ACR guide requires reporting of CAC detected on LCS LDCT (63), and reporting of CAC has been shown to increase statin prescriptions within an LCS population (66).

Conventional CAC scoring is done with CT scans performed via an ECG-gated breath-hold technique to minimize heart motion and with 2.5- to 3-mm slice thickness (Table 3). The Agatston method of scoring, based on the area and attenuation of calcified plaque, is the most widely used and validated scoring method (67). Incidentally detected CAC on nongated chest CT is typically assessed qualitatively into categories of none, mild, moderate, or severe. Higher CAC scores correlate with a higher risk of coronary events on both dedicated and nondedicated CT, including in LCS trial participants (10, 68, 69). LCS LDCT scans are performed with a single breath-hold technique, thinner slice thickness to allow better lung evaluation, and a lower radiation dose (≤3 mGy). They are not ECG gated, resulting in more heart motion. It is unclear if the nongated, thinner slice LDCT performed for LCS may accurately estimate CAC (70–73).

Table 3.

Coronary Artery Calcification Scoring

| Coronary Calcium Scoring CT | Lung Cancer Screening CT | |

|---|---|---|

| Imaging technique |

|

|

| CAC scoring methods |

|

|

| Limitations of CAC scoring |

|

|

Definition of abbreviations: CAC = coronary artery calcification; CT = computed tomography; HU = Hounsfield units; i.v. = intravenous.

Nonetheless, LDCT screening not only aids in the detection of lung cancer but may also detect CAC that can be quantified and reported. CAC scoring provides incremental risk assessment of coronary events compared with traditional Framingham risk factors. It can help clinicians identify individuals at increased cardiac risk who may benefit from intensive lifestyle and medical interventions to reduce clinical events, potentially reducing all-cause mortality. In the NLST, CVD emerged as the leading cause of death, surpassing deaths from lung cancer (8). Compared with chest radiographs, LDCT LCS led to a reduction in all-cause mortality. As noted above, this reduction varied by race, with significant decreases observed for Black individuals and individuals of other races (but not for White individuals) (9).

Although technical differences between image acquisition in coronary calcium CT and LDCT examinations affect CAC assessment, several studies have addressed CAC reporting in the LCS population (10, 68, 69, 74). Although the studies are heterogeneous, with some reporting outcomes, including CVD, cardiac mortality, and all-cause mortality (NLST, MILD [Multicentric Italian Lung Detection], NELSON) and others reporting various imaging methods to detect CAC (NLST, K-LUCAS [Korean Lung Cancer Screening Project]), in general, all demonstrated that CAC scores reported on LDCT scans correlate with outcomes. A meta-analysis of six LCS studies reporting Agatston CAC score and CV mortality (NLST, NELSON, MILD, ELCAP [Early Lung Cancer Action Project], DLCST [Danish Lung Cancer Screening Trial], ITALUNG [Italian Lung Cancer Screening Trial])/ITALUNG [Italian Lung Cancer Screening Trial]) demonstrated that men and women with CAC scores greater than zero had higher CV and all-cause mortality rates, with relative risks of 2.02 and 2.29, respectively (7).

A retrospective analysis of the NLST revealed that the scoring of CAC on LDCT images using visual assessment, ordinal scores, or the Agatston method was reliable for cardiac risk stratification, predicting mortality from CVD and overall all-cause mortality (10). An analysis evaluating the value of the number and maximum volume of CAC compared with modified Agatston in male individuals undergoing LDCT showed that CV events increased with larger numbers of calcified coronary arteries. Furthermore, the number but not the maximum volume of CAC provided minimal prognostic value over the modified Agatston score (68). Because of its feasibility, visual assessment of CAC using a mild, moderate, or severe scoring system is most widely used for nongated chest CT examinations (such as LDCT); it is fast, more accessible for a radiologist to perform, and requires no additional software or technologist processing and achieved moderate to substantial interobserver agreement (74). However, interobserver agreement among radiologists for visual assessment compared with alternative artery-based and segment-based grading systems was lower (74).

The aim of the CAC Data and Reporting System (CAC-DRS) is to standardize the reporting of CAC on gated cardiac and nongated chest CT scans (75). CAC-DRS uses categories 0–3, aligning with Agatston score categories 0 (very low risk), 1 (mild risk, 1–99), 2 (moderate risk, 100–299), and 3 (severe risk, ≥300). The efficacy of CAC-DRS to predict the risk of CVD has been validated in several datasets, showing its superior discrimination of the risk for coronary events and all-cause mortality compared with the Agatston score alone (76).

Professional societies’ recommendations on reporting incidental CAC

Several organizations provide recommendations for assessing incidental CAC on chest CT examinations (70–73). The Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography and the Society of Thoracic Radiology issued recommendations stating that CAC should be reported on all noncardiac chest CT examinations using the Agatston scoring method or estimated as none, mild, moderate, or severe and reported on all noncardiac chest CT examinations (29). The ACR recommended that CAC scoring be evaluated using the Agatston or a visual method, estimated as none, mild, moderate, heavy, or severe, and reported when it is likely to affect patient management. The ACR quick reference guide states that CAC should be reported as none, mild, moderate, or severe and that only moderate or severe CAC is significant and should be assigned a Lung-RADS S modifier. Yet the guide also indicates that even patients with mild CAC, not requiring the S modifier, may benefit from a CVD risk assessment.

Knowledge gaps and research opportunities

Although integrating CAC scores into risk assessment for CVD in screen-eligible individuals holds promise, there are knowledge gaps and areas for future research, including the following:

It is unclear whether radiologists are aware of current recommendations for assessing incidental CAC on chest CT examinations.

It is poorly understood whether reporting CAC with quantification is standard practice for radiologists or if it is considered an expected finding in individuals who smoke and, therefore, not described by radiologists or not included in the study impression.

Data are needed to understand whether reporting of severe CAC and/or high risk scores identified during LCS of asymptomatic patients results in preventive interventions such as lifestyle modification or initiation of statin or antiplatelet therapies.

It is unclear whether CAC reporting in asymptomatic patients undergoing LCS screening will influence clinical outcomes, for example, all-cause mortality.

The overall impact of preventive therapy on the basis of risk assessments, including traditional tools and CAC quantification, on CVD outcomes is not known.

Larger prospective studies are needed to evaluate and assess the role of CVD risk calculators and CAC reporting in screen-eligible populations.

Further research is needed to address the significance of an incremental increase in CAC score in patients taking or not taking high-intensity lipid-lowering drugs. The implication is that endothelial healing is accelerated with statin therapy, which can cause treatment-related increases in CAC concurrent with lowering residual event risk.

Prioritized research questions

Of the initial six questions in Section IV, voting results indicated that all but one question were highest priority (Table 2):

Section IV, Q1: Does the presence or absence of CAC on LCS LDCT influence cardiac management decisions made by ordering clinicians?

Section IV, Q2: Is coronary calcium scoring reliably achievable on LCS LDCT? If so, can LCS LDCT serve a dual purpose for coronary calcium scoring? If so, what are the potential benefits and harms?

Section IV, Q3: Considering the variability in methods and software costs, what strategies can be used to standardize CAC evaluation on LDCT?

Section IV, Q5: Does reporting the presence or absence of CAC on LCS LDCT influence the behavior of patients (tobacco cessation, other cardiac prevention interventions, adherence to LCS, etc.)?

Section IV, Q6: Given racial disparities in CVD incidence and mortality (with Black individuals having worse outcomes than White individuals), will detection and possible treatment of CAC increase or reduce these differences?

Conclusions

LCS with LDCT detects lung and nonlung IFs unrelated to lung cancer, with both potential benefits and harms. Through this multidisciplinary workshop, the panel identified knowledge gaps across three areas: 1) reporting of IFs, 2) management of IFs, and 3) identifying and reporting CAC on LCS LDCT. This statement provides a research agenda to further efforts focused on evaluating, managing, and increasing awareness of IFs in LCS. Standardized and consistent reporting of SIFs on LDCT will allow further research in clinical outcomes, including harms and benefits, as well as study of implementation approaches across healthcare systems.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Rachel Kaye and John Harmon of the ATS and Nicole Cruz, Lindsay Lane, and Elizabeth Paget for their help in supporting the preworkshop and workshop meetings and the scheduling of subsequent meetings between the co-chairs and the co-chairs and the writing panel. The authors also thank Michael Pritchard for assistance in the Delphi survey administration to develop this statement, as well as the Yale School of Medicine Multimedia Team, which provided assistance with graphics for Figure 1.

This research statement was prepared by an ad hoc subcommittee of the ATS Assembly on Thoracic Oncology.

Members of the subcommittee are as follows:

Louise M. Henderson, Ph.D., M.S.P.H. (Co-Chair)1

M. Patricia Rivera, M.D. (Co-Chair)2

Lynn T. Tanoue, M.D., M.B.A. (Co-Chair)5

Abbie Begnaud, M.D.7*

Farouk Dako, M.D., M.P.H.8*

Kwun M. Fong, M.B. B.S., Ph.D., F.R.A.C.P.10‡

Michael Gieske, M.D.11,12*

Kimberly Kallianos, M.D.13*

Roger Y. Kim, M.D., M.S.C.E.9§

Stephen Lam, M.D., F.R.C.P.C.14,15‡

Pyng Lee, M.D., Ph.D.16,17‡

Mary Pasquinelli, D.N.P., F.N.P.-B.C.18‡

Ilana Richman, M.D., M.H.S.6*

Lori C. Sakoda, Ph.D., M.P.H.19,20*

Ronald G. Schwartz, M.D., M.S.3,4*

Robert A. Smith, Ph.D.21‡

Nichole T. Tanner, M.D., M.S.C.R.22,23§

Matthew Triplette, M.D., M.P.H.24,25‡

Emily B. Tsai, M.D.26*

Joseph Yeboah, M.D., M.S.27*

*Presenter.

‡Member.

§Small writing group.

1Department of Radiology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina; 2Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine and 3Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, and 4Nuclear Medicine Division, Department of Imaging Sciences, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, New York; 5Section of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine and 6Section of General Internal Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut; 7Department of Medicine, University of Minnesota Twin Cities, Minneapolis, Minnesota; 8Division of Cardiothoracic Imaging, Department of Radiology, and 9Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care, Department of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; 10University of Queensland Thoracic Research Center, School of Medicine, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia; 11St. Elizabeth Healthcare Northern Kentucky, Erlanger, Kentucky; 12St. Elizabeth Healthcare Southeast Indiana, Dearborn, Indiana; 13Department of Radiology and Biomedical Imaging, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, California; 14Department of Medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; 15BC Cancer, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; 16Division of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, National University Hospital, Singapore; 17National University of Singapore, Singapore; 18Department of Medicine, University of Illinois Chicago, Chicago, Illinois; 19Division of Research, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Pleasanton, California; 20Department of Health Systems Science, Kaiser Permanente Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine, Pasadena, California; 21Center for Early Cancer Detection Science, American Cancer Society, Atlanta, Georgia; 22Ralph H. Johnson VA Healthcare System, Charleston, South Carolina; 23Division of Pulmonary Critical Care Medicine, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina; 24Division of Public Health Sciences, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle, Washington; 25Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington; 26Department of Radiology, Stanford University, Stanford, California; and 27Section on Cardiovascular Medicine, School of Medicine, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, North Carolina

Footnotes

This Official Research Statement of the American Thoracic Society was approved December 2024

Supported by the American Thoracic Society.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202501-0011ST on February 10, 2025

Subcommittee Disclosures: L.M.H. is employed by the University of North Carolina School of Medicine; and received research support from NIH/NCI and Stand Up To Cancer. R.Y.K. received research support from the American Cancer Society, the National Cancer Institute, the Respiratory Health Association, Siemens, and the University of Pennsylvania; holds stock in Amgen; and received travel support from Intuitive. N.L.T. received research support from Biodesix, Delphi Diagnostics, Eon, and Nucleix. E.B.T. served as a consultant for Genentech; and received royalties from a textbook. A.B. served on a data safety monitoring board for Biodesix; served as fiduciary officer for A Breath of Hope Lung Foundation; and received research support from AHRQ and the Minnesota Cancer Clinical Trials Network. M.G. served as a board member for the White Ribbon Project; served as a consultant for the Association of Cancer Care Centers, the Lung Ambition Alliance, and the Rural Appalachian Lung Cancer Screening Initiative; and received travel support for the Association of Cancer Care Centers and the National Lung Cancer Roundtable. I.R. received research support from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the NIH/NCI. L.C.S. received research support from AstraZeneca and the National Cancer Institute. J.Y. is an employee of Wake Forest University. K.M.F. received research support from the Australian Cancer Research Foundation, the Cancer Council Queensland, Mevis Veolity, the National Health and Medical Research Council, and Olympus; and served as a speaker and received travel support from multiple society and conference organizers. M.P. served as a consultant for CARES and the Center for Business Models in Healthcare; received honoraria from APPOS and GO2 for Lung Cancer; served in a leadership role for the National Lung Cancer Roundtable, and the Prevent Cancer QIW Workshop; received research support from the American Lung Association, the Coleman Foundation, and VA LPOP; received travel support from the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, GO2 for Lung Cancer, the Rescue Lung Rescue Life, and the World Conference of Lung Cancer. M.T. served on an advisory board and as a consultant for the GO2 Foundation; served as a consultant for Quane McColl; and received research support from Bristol Myers Squibb. L.T.T. served in a leadership role for the American Board of Internal Medicine; and served as a section author for UpToDate. M.P.R. is an employee of the University of Rochester Medical Center; and served as a consultant for the American Board of Internal Medicine and the American Cancer Society. F.D., K.K., R.G.S., S.L., P.L., and R.A.S. reported no commercial or relevant non-commercial interests from ineligible companies.

References

- 1. Aberle DR, Berg CD, Black WC, Church TR, Fagerstrom RM, Galen B, et al. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team The National Lung Screening Trial: overview and study design. Radiology . 2011;258:243–253. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. de Koning HJ, van der Aalst CM, de Jong PA, Scholten ET, Nackaerts K, Heuvelmans MA, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with volume CT screening in a randomized trial. N Engl J Med . 2020;382:503–513. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moyer VA, Force USPST Screening for lung cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med . 2014;160:330–338. doi: 10.7326/M13-2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Krist AH, Davidson KW, Mangione CM, Barry MJ, Cabana M, Caughey AB, et al. US Preventive Services Task Force Screening for Lung Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA . 2021;325:962–970. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Henderson LM, Su I-H, Rivera MP, Pak J, Chen X, Reuland DS, et al. Prevalence of lung cancer screening in the US, 2022. JAMA Netw Open . 2024;7:e243190. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.3190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Roth GA, Forouzanfar MH, Moran AE, Barber R, Nguyen G, Feigin VL, et al. Demographic and epidemiologic drivers of global cardiovascular mortality. N Engl J Med . 2015;372:1333–1341. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gendarme S, Goussault H, Assie JB, Taleb C, Chouaid C, Landre T. Impact on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality rates of coronary artery calcifications detected during organized, low-dose, computed-tomography screening for lung cancer: systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel) . 2021;13:1553. doi: 10.3390/cancers13071553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Church TR, Black WC, Aberle DR, Berg CD, Clingan KL, Duan F, et al. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team Results of initial low-dose computed tomographic screening for lung cancer. N Engl J Med . 2013;368:1980–1991. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tanner NT, Gebregziabher M, Hughes Halbert C, Payne E, Egede LE, Silvestri GA. Racial differences in outcomes within the National Lung Screening Trial: implications for widespread implementation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2015;192:200–208. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201502-0259OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chiles C, Duan F, Gladish GW, Ravenel JG, Baginski SG, Snyder BS, et al. NLST Study Team Association of coronary artery calcification and mortality in the National Lung Screening Trial: a comparison of three scoring methods. Radiology . 2015;276:82–90. doi: 10.1148/radiol.15142062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li LF, Chan RLY, Lu L, Shen J, Zhang L, Wu WKK, et al. Cigarette smoking and gastrointestinal diseases: the causal relationship and underlying molecular mechanisms (review) Int J Mol Med . 2014;34:372–380. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jonas DE, Reuland DS, Reddy SM, Nagle M, Clark SD, Weber RP, et al. Screening for lung cancer with low-dose computed tomography: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA . 2021;325:971–987. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.0377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American College of Radiology. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2024. Lung CT Screening Reporting & Data System (Lung-RADS®.https://www.acr.org/Clinical-Resources/Clinical-Tools-and-Reference/Practice-Parameters-and-Technical-Standards/ [Google Scholar]

- 14.American College of Radiology. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2022. https://www.acr.org/-/media/ACR/Files/RADS/Lung-RADS/Lung-RADS-2022.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tsai EB, Chiles C, Carter BW, Godoy MCB, Shroff GS, Munden RF, et al. Incidental findings on lung cancer screening: significance and management. Semin Ultrasound CT MR . 2018;39:273–281. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2018.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Henderson LM, Chiles C, Perera P, Durham DD, Lamb D, Lane LM, et al. Variability in reporting of incidental findings detected on lung cancer screening. Ann Am Thorac Soc . 2023;20:617–620. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202206-486RL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Reiter MJ, Nemesure A, Madu E, Reagan L, Plank A. Frequency and distribution of incidental findings deemed appropriate for S modifier designation on low-dose CT in a lung cancer screening program. Lung Cancer . 2018;120:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Berland LL, Silverman SG, Gore RM, Mayo-Smith WW, Megibow AJ, Yee J, et al. Managing incidental findings on abdominal CT: white paper of the ACR Incidental Findings Committee. J Am Coll Radiol . 2010;7:754–773. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Heller MT, Harisinghani M, Neitlich JD, Yeghiayan P, Berland LL. Managing incidental findings on abdominal and pelvic CT and MRI, part 3: white paper of the ACR Incidental Findings Committee II on splenic and nodal findings. J Am Coll Radiol . 2013;10:833–839. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2013.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Khosa F, Krinsky G, Macari M, Yucel EK, Berland LL. Managing incidental findings on abdominal and pelvic CT and MRI, part 2: white paper of the ACR Incidental Findings Committee II on vascular findings. J Am Coll Radiol . 2013;10:789–794. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2013.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Patel MD, Ascher SM, Paspulati RM, Shanbhogue AK, Siegelman ES, Stein MW, et al. Managing incidental findings on abdominal and pelvic CT and MRI, part 1: white paper of the ACR Incidental Findings Committee II on adnexal findings. J Am Coll Radiol . 2013;10:675–681. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2013.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sebastian S, Araujo C, Neitlich JD, Berland LL. Managing incidental findings on abdominal and pelvic CT and MRI, part 4: white paper of the ACR Incidental Findings Committee II on gallbladder and biliary findings. J Am Coll Radiol . 2013;10:953–956. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2013.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hoang JK, Langer JE, Middleton WD, Wu CC, Hammers LW, Cronan JJ, et al. Managing incidental thyroid nodules detected on imaging: white paper of the ACR Incidental Thyroid Findings Committee. J Am Coll Radiol . 2015;12:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2014.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gore RM, Pickhardt PJ, Mortele KJ, Fishman EK, Horowitz JM, Fimmel CJ, et al. Management of incidental liver lesions on CT: a white paper of the ACR Incidental Findings Committee. J Am Coll Radiol . 2017;14:1429–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2017.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]