Abstract

Background:

HCC is one of the most prevalent and deadliest malignancies worldwide, with a poor prognosis. Altered histone modifications have been shown to play a significant role in HCC. However, the biological roles and clinical relevance of specific histone modifications, such as the asymmetric dimethylation on arginine 3 of histone H4 (H4R3me2a), remain poorly understood in HCC.

Methods:

In this study, immunohistochemical staining was performed to assess histone H4R3me2a modification in 32 pairs of HCC tissues and corresponding adjacent nontumor liver tissues. Cellular-level experiments and subcutaneous xenograft models in nude mice were used to investigate the effects of silencing protein arginine methyltransferase 1 (PRMT1) with shRNA or pharmacologically blocking PRMT1 activity on HCC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. RNA-seq analysis combined with Chip-qPCR validation was employed to explore the regulatory mechanism of PRMT1 on SOX18 expression. The downstream target of SOX18 was identified using the JASPAR database and a dual-luciferase reporter system.

Results:

The level of histone H4R3me2a modification was significantly elevated in HCC tissues and closely associated with poor prognosis in patients with HCC. Silencing PRMT1 or pharmacologically inhibiting its activity effectively suppressed the proliferation, migration, and invasion of HCC cells. Mechanistically, PRMT1 was found to regulate SOX18 expression by modulating histone H4R3me2a modification in the SOX18 promoter region. LOXL1 was identified as a downstream target of the transcription factor SOX18.

Conclusions:

This study revealed the clinical relevance of histone H4R3me2a modification in HCC and demonstrated that PRMT1 promotes malignant behavior in HCC cells by modulating H4R3me2a modification in the SOX18 promoter region. The findings elucidate the role and molecular mechanism of PRMT1-mediated histone H4R3me2a modification in HCC progression and highlight the potential clinical applications of PRMT1 inhibitors. These results may provide new insights into the treatment of HCC.

Keywords: epigenetics, HCC, histone methylation modification, tumor proliferation

INTRODUCTION

HCC ranks as one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths globally, characterized by its high prevalence and mortality rates. 1 Despite advances in medical research and therapeutic interventions, the prognosis for patients with HCC remains poor. 2 Therefore, uncovering the pathogenesis of liver cancer and identifying therapeutic targets are central and urgent tasks worldwide.

The role of epigenetics in cancer development, particularly through modifications of histone proteins, has gained significant attention. Histone modifications, such as methylation, acetylation, and phosphorylation, play crucial roles in regulating gene expression by altering chromatin structure and accessibility.3,4 Among these, histone methylation has been implicated in various biological processes and diseases, including cancers. Recent studies suggest that epigenetic alterations can serve as biomarkers for HCC diagnosis and prognosis and as targets for therapeutic intervention.5–8 Among these histone methylation modifications, histone H4 at arginine 3 (H4R3me2a) plays a critical role. Studies indicate that the levels of H4R3me2a modification are associated with the occurrence, development, and drug resistance of various tumors.9–11 In prostate cancer, the methylation status of H4R3 is significantly associated with clinical characteristics such as tumor grading or the risk of prostate cancer recurrence. 8 In breast cancer, protein arginine methyltransferase 1 (PRMT1)-mediated H4R3me2a modification can influence the transcription of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), thereby affecting the sensitivity of breast cancer to chemotherapeutic drugs. However, its expression in liver cancer clinical samples and its relationship with prognosis remain unclear.

PRMT1 is the first and currently the only identified enzyme that introduces asymmetric methylation of histone H4 at the third arginine residue, resulting in the formation of the active histone mark, H4R3me2a.12–14 In HCC, previous studies indicate elevated PRMT1 expression correlates with adverse prognostic outcomes. In addition, increased PRMT1 expression is associated with alterations in the CDKN1A, TGF-β1, and Smad signaling pathways.15,16 However, the molecular mechanisms by which PRMT1 influences histone modifications and their biological functions through its arginine methyltransferase activity in liver cancer remain unclear.

This study aims to elucidate the clinical relevance of H4R3me2a modification in HCC and to explore the underlying molecular mechanisms by which PRMT1-mediated H4R3me2a influences the progression of HCC. By investigating the effects of PRMT1 and H4R3me2a on the regulation of crucial genes and signaling pathways involved in HCC progression, we seek to uncover new therapeutic strategies that could potentially improve the prognosis for patients with HCC.

METHODS

Cell lines and culture condition

The human liver cancer cells, SNU398, SK-Hep1, Hep3B, PLC/PRF/5, SNU387, SNU449, HUH7, Li7, Huh6, HCCLM3, MHCC97H, and HepG2, were cultured in high-glucose DMEM with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum, glutamine, and penicillin-streptomycin under standard culture conditions (37 °C, 5% CO2).

Clinical tissues and ethics statement

Thirty-two tumor tissues and matched adjacent normal tissues were collected from patients with pathologically and clinically confirmed HCC from the Huashan Hospital Affiliated to Fudan University, General Surgery Department, Fudan University, between July 2015 and August 2018. The Institutional Review Board of Huashan Hospital approved the use of the tumor samples in this study. All human tumor tissues were collected after obtaining written informed consent from patients.

Immunohistochemistry

A tissue microarray containing 32 HCC samples from the Huashan Hospital Affiliated to Fudan University was used for immunohistochemistry. The method of Immunohistochemical staining and the H-score algorithm was described in our previous study. 17 The patients were divided into high-expression or low-expression groups according to the median value of H-scores. The demographic data, including key clinicopathological parameters of 32 patients with HCC are shown in Supplemental Table S1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B888. All antibodies used in immunohistochemistry are listed in Supplemental Table S2, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B888.

Compounds

TC-E 5003 (S0855, Selleck) and MS023 (S8112, Selleck) were purchased from Selleck Chemicals. TC-E 5003 (HY-10757) and WP1066 (HY-15312) were purchased from MedChemExpress.

Plasmid construction and lentivirus production

Lentiviral vectors containing shRNAs against PRMT1, and SOX18 came from the TRC human shRNA (Lenti) Library. Empty pLKO.1 vector was used as a negative control. All shRNA Sense Sequences are listed in Supplemental Table S3, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B888. Wildtype human PRMT1 (PRMT1-WT) coding region was cloned into the pLX304-Blast-V5 Lentiviral plasmid. The PRMT1 (PRMT1-Mut, amino acids 86–90 [GSGTG] deleted) vector was constructed by site-directed mutagenesis. The oligonucleotide used to induce the deletion was 5′-GGTGGTGCTGGACGTCATCCTCTGCATGTTTGC-3′ as described before. 10 SOX18 (NM_018419.3) coding region was cloned into the PGMLV-CMV-MCS-3×Flag-EF1-ZsGreen1-T2A-Puro plasmid. An empty backbone vector was used as a negative control. Cells were transfected using jetPRIME transfection reagent (polyplus) with the vectors into 293T cells following the manufacturer’s instructions. The supernatant medium containing the virus was concentrated by Universal Virus Concentration Kit (Beyotime). Then viruses were used to infect indicated cells followed by 2 μg/mL puromycin selection for 3–5 days or 20 μg/mL Blasticidin selection for 7–10 days.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (Sangon Biotech) adding phosphatase and protease inhibitor cocktails (Sigma). Protein quantification was conducted using an enhanced BCA protein assay Kit (P0010, Beyotim). Quantified protein lysates were separated with 10%–15% Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis and transferred to the Polyvinylidene Fluoride membrane using a fast transfer buffer stock solution (Biofuraw). All procedures were conducted according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After blocking with 5% milk confining liquid at room temperature for 1–2 hours, the Polyvinylidene Fluoride membranes were incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C on a rocking platform shaker. The information on antibodies used in this project was referred to Supplemental Table S2, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B888. Secondary antibodies were used at a 1:5000–20000 dilution of anti-rabbit or anti-mouse HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Bound antibodies were visualized with the enhanced ECL kit (ShareBio).

RNA extraction and quantitative reverse-transcription PCR

EZ-press RNA Purification Kit (EZBioscience) was used to extract total RNA from cells and tissues. cDNA was acquired using a Color Reverse Transcription Kit with gDNA remover (EZBioscience). Quantitative PCR reactions were conducted using 2×Color SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (EZBioscience). The sequences of the primers for quantitative reverse-transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) are shown in Supplemental Table S3, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B888.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation and q-PCR assay

We immunoprecipitated chromatin fractions from MHCC97H cells with specific antibodies following the standard protocols as described. 18 Normal rabbit IgG served as the control. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (Chip) samples were analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR using 2×Color SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (EZBioscience). We calculated the percentage of Chip DNA relative to the input DNA. The relative enrichment assay was conducted following the previously described method. 19 The primer sequences for Chip q-PCR are listed in Supplemental Table S3, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B888.

Luciferase reporter assays

For promoter interactive identification, the luciferase reporter PGL4.10 plasmid was purchased from Promega, and the promoter region of LOXL1 and described truncated fragments were inserted into the plasmid between the Nhel and Xhol sites. Indicated cells were seeded into 96-well plates and transfected with 100 ng indicated reporter plasmid and 10 ng Renilla following the recommended protocol for the jetPRIME transfection system (Polyplus). After incubation for 48 hours, firefly and renilla luciferase activities in the cell lysates were measured according to the dual-luciferase reporter assay kit (TM040, Promega).

In vivo experiments

BALB/c nude mice used for xenograft models were purchased from Shanghai Jihui Laboratory Animal Care Company (Shanghai, China). Indicated MHCC97H cells (2 × 106 per mouse) or Hep3B (4 × 106 per mouse) were injected into the right shoulder of 6-week-old BALB/c nude mice. Based on the measurement of the vernier caliper, tumor volume was assessed by the modified ellipsoidal formula: volume = ½ (length × width2) every 2 days. For the in vivo proliferation assay, mice were euthanized at day 12. For the PRMT1 inhibitor in vivo experiment, when the tumor reached around 50 mm3, nude mice were randomly assigned to each group to receive different solvents, TC-E 5003 (100 mg/kg) and DMSO once daily for 16 days. All mice were raised on a 12-hour dark/light cycle and had sufficient access to food and water. All procedures of animal experiments were performed by The Animal Care and Use Committee of Renji Hospital affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism software (GraphPad Software Version 8.0). In vitro and in vivo data were shown as the mean ± SEM. Differences among variables were assessed by a 2-tailed Student t test. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to evaluate overall survival and progression-free survival rates of patients and the Log-Ran test was conducted for difference comparison.

RESULTS

Upregulation of H4R3me2a and prognostic significance in HCC

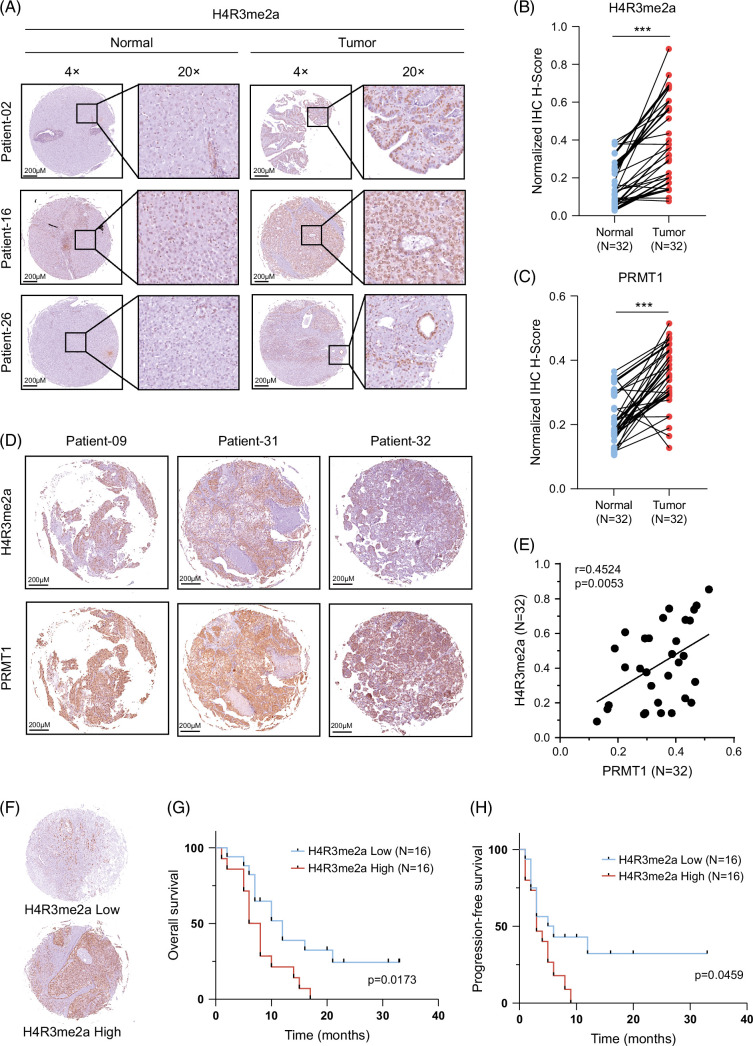

We analyzed the levels of H4R3me2a in 32 paired samples from patients with HCC through immunohistochemical staining. The level of staining was independently assessed by 2 pathologists who were blinded to all clinicopathological parameters. The methods for quantification of immunohistochemical results are described in the Methods section. The level of H4R3me2a is elevated in tumor tissue compared to paracancerous tissue (Figures 1A, B). PRMT1 is the first and the only identified enzyme currently that introduces asymmetric methylation of histone H4 at the third arginine residue, resulting in the formation of the active histone mark, H4R3me2a. We also examined the expressions of PRMT1 in the 32 paired samples. Results revealed a significant upregulation of PRMT1 in tumor tissues (Figure 1C), and there was a significant positive correlation between the levels of PRMT1 and H4R3me2a (r = 0.4524, p = 0.0053) (Figures 1D, E).

FIGURE 1.

Upregulation of H4R3me2a and prognostic significance in HCC. (A) Representative images of immunohistochemical analysis for H4R3me2a from tumor tissues and adjacent nontumor normal tissues of 32 paired samples from patients with HCC. (B, C) Quantified H-scores of H4R3me2a and PRMT1 in the tumor tissues and adjacent nontumor normal tissues of these 32 paired HCC samples. The p value is calculated by paired 2-sided t test. (D) Representative images of immunohistochemistry for H4R3me2a and PRMT1 from the tumor tissues of these 32 paired HCC samples. (E) Correlation between H4R3me2a and PRMT1 in HCC tissues. Pearson correlation coefficient, r = 0.4524, p = 0.0053. (F) Representative images for high or low levels of H4R3me2a in HCC tissues. (G, H) Kaplan-Meier analyses of overall survival rates and progression-free survival rates for patients with HCC were performed according to H4R3me2a H-scores. High and low levels of H4R3me2a were defined according to the median value of H-scores. The p value was calculated by the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. ***p < 0.001. Abbreviations: H4R3me2a, histone H4 at arginine 3; PRMT1, protein arginine methyltransferase 1.

We further analyzed the clinical significance of H4R3me2a. The 32 patients with HCC were divided into high-expression or low-expression groups according to the level of H4R3me2a (Figure 1F), and survival analysis was performed. In Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, we observed statistically significant differences in the risk of overall survival rates and progression-free survival rates between the 2 groups (Figures 1G, H); patients with high levels of H4R3me2a exhibit poor prognosis. Simultaneously, the levels of PRMT1 in our clinical cohort were also significantly correlated with prognosis (Supplemental Figures S1A, B, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B888). The H4R3me2a immunohistochemical scores and clinicopathological information were collected for univariate analysis (Supplemental Tables S1 and S4, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B888). The analysis revealed a potential correlation between H4R3me2a expression and tumor size (p = 0.053), while no significant associations were observed with sex (p = 0.522), age (p = 0.759), liver cirrhosis (p = 0.713), lymphatic metastasis (p = 0.29), or the number of tumors (p = 0.909).

These results first indicate that the level of histone H4R3me2a modification may be a promising biomarker for liver cancer diagnosis and a good predictor for clinical outcomes.

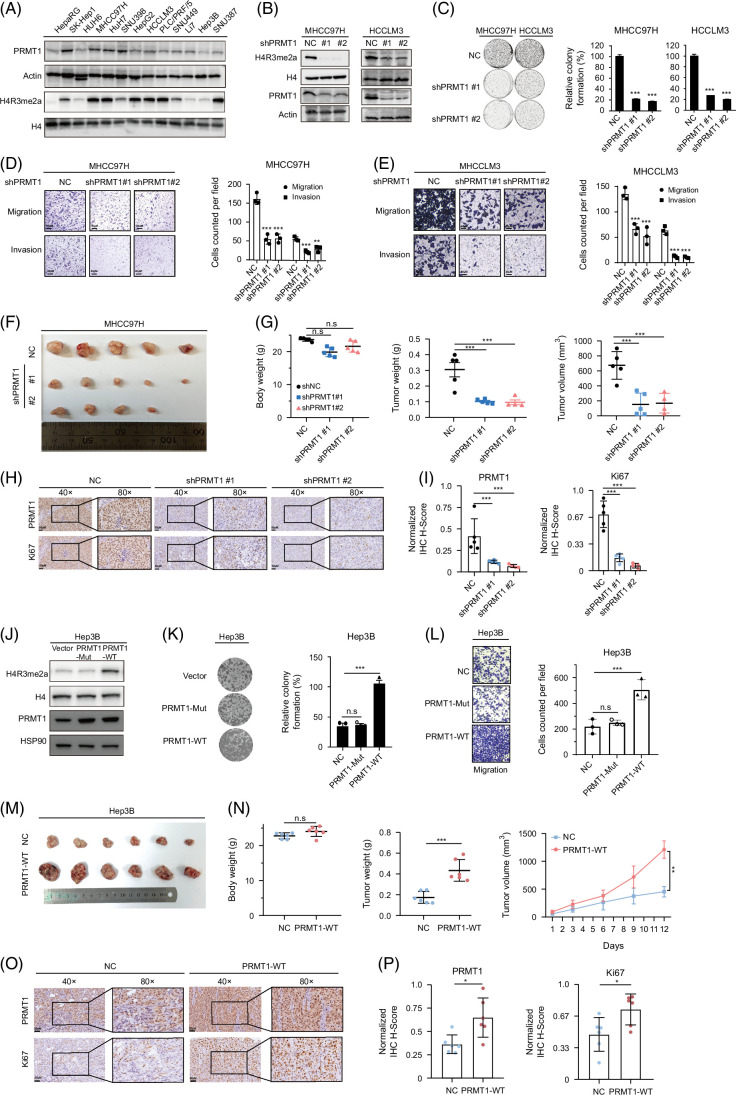

PRMT1-mediated modification of histone H4R3me2a is essential for the progression of liver cancer cells

PRMT1 is the key enzyme involved in mediating H4R3me2a modification. The online data from the Crispr-Cas9 database DepMap (https://depmap.org/portal/, Public 23Q2+Score, Chronos) showed that the Gene Effect of PRMT1 was <−1 in 86.9% liver cancer cell lines, indicating that PRMT1 plays an indispensable role in liver cancer cell survival and proliferation (Supplemental Figure S1C, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B888). We examined the protein levels of PRMT1 and H4R3me2a in liver cancer cell lines (Figure 2A). PRMT1 was efficiently knocked down in MHCC97H and HCCLM3 cells with consistent downregulation of H4R3me2a modification, as shown in Figure 2B. PRMT1 depletion markedly inhibited cell growth (Figure 2C) and impaired their migration and invasion capacities (Figures 2D, E). Subcutaneous tumor experiments in mice also showed that PRMT1 knockout significantly suppressed the proliferation of liver cancer cells in vivo (Figures 2F, G). The immunohistochemical staining of the subcutaneous tumor tissues from mice suggested a significant decrease in levels of PRMT1 and Ki67 in the PRMT1 knockout group (Figures 2H, I).

FIGURE 2.

PRMT1-mediated H4R3me2a promotes the progression of liver cancer. (A) Analysis for PRMT1 and H4R3me2a expression level in liver cancer cell lines. (B) PRMT1 knockdown reduced the levels of methylation mark H4R3me2a in HCC cells. (C) Long-term cell proliferation assay for HCC cells with PRMT1 knockdown. (D, E) Effects of HCC cells with PRMT1 knockdown on migration and invasion. (F, G) PRMT1 knockdown restrained tumor growth in the subcutaneous xenograft tumor model. Representative images of subcutaneous tumors (F); mice body weight, tumor weight, and tumor volume (G). (H, I) Immunohistochemical analysis for PRMT1 and Ki67 in tumor tissues from the subcutaneous xenograft tumors. (J) The plasmid of PRMT1 mutation (PRMT1-Mut), which mutated the arginine methylation active site (GSGTG, amino acids 86–90) of PRMT1 was employed to explore the effects of PRMT1 on the levels of methylation mark H4R3me2a. (K, L) Effects of HCC cells with enhanced H4R3me2a deposition on colony formation and migration. (M, N) Overexpression of PRMT1 effectively enhanced the H4R3me2a deposition and promoted tumor growth in the subcutaneous xenograft tumor model. Representative images of subcutaneous tumors (M); mouse weight, tumor weight, and tumor growth curve (N); (O, P) Immunohistochemical analysis for PRMT1 and Ki67 in tumor tissues from the subcutaneous xenograft tumors. n.s: no significance. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Abbreviations: H4R3me2a, histone H4 at arginine 3; PRMT1, protein arginine methyltransferase 1.

To further investigate whether the effect of PRMT1 on liver cancer cells relies on its enzyme activity for arginine methylation, we generated the plasmid of PRMT1 mutant with crucial enzymatic site deletion (PRMT1-Mut, amino acids 86–90 (GSGTG) deleted), following the methodologies described in the previous study.9,10 The expression of exogenous PRMT1 was confirmed in Hep3B cells (Figure 2J). Notably, only wildtype PRMT1 exhibited its arginine methylation activity on H4R3me2a, as shown in Figure 2J. The in vitro experiments indicated that the capabilities of proliferation and migration were significantly enhanced in wildtype PRMT1 overexpressed group (Figures 2K, L). In the subcutaneous tumor model, PRMT1 significantly promoted tumor growth (Figures 2M, N). Immunohistochemical staining revealed elevated levels of PRMT1 and Ki67 in the PRMT1 group (Figures 2O, P). These findings provide evidence for the crucial role of PRMT1-mediated H4R3me2a in the progression of HCC.

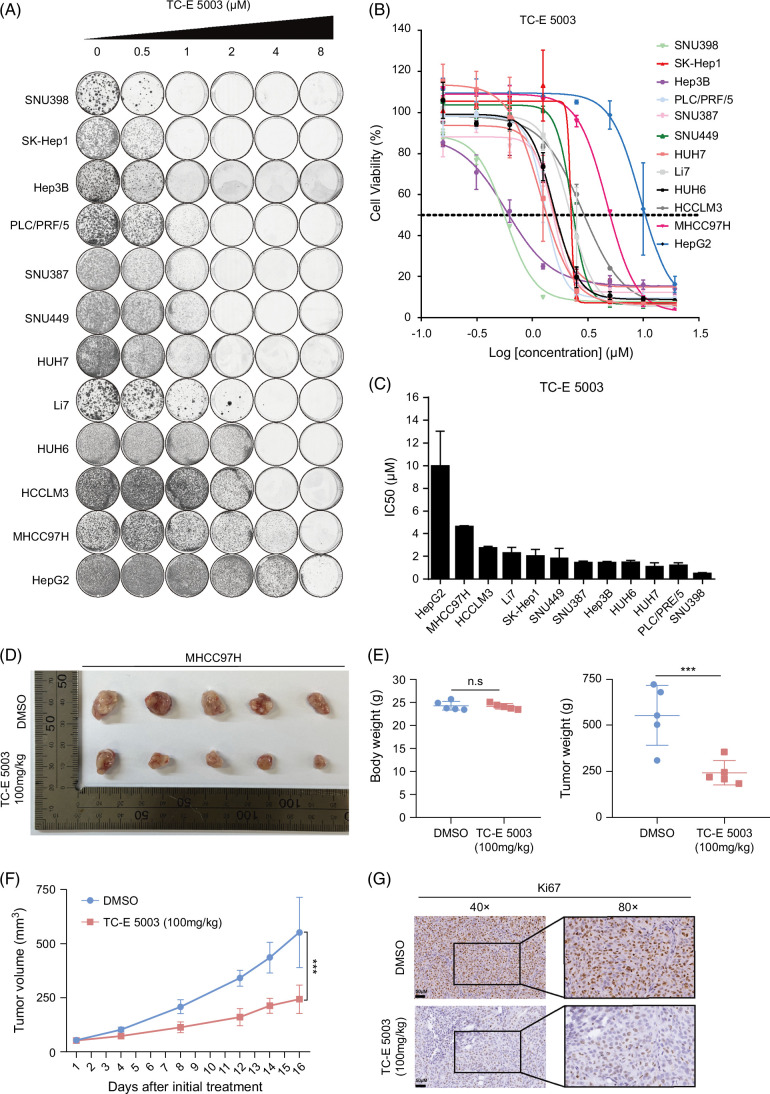

Pharmacological inhibitions of PRMT1 restrain HCC growth

In our study, we chose PRMT1-specific inhibitor (TC-E 5003) and Type-I PRMTs inhibitor (MS023) for inhibitor efficacy assessments in liver cancer cells. We found that treatment with TC-E 5003 or MS023 both led to a reduction of cell viability in a wide panel of liver cancer cell lines based on long-term and short-term proliferation assays (Figures 3A, B and Supplemental Figures S2A, B, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B888) and calculated their IC50 values across cells by short-term proliferation assays (Figure 3C and Supplemental Figure S2C1, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B888). Results indicated that PRMT1 inhibitors have antiproliferation effects on liver cancer cell lines with low expression of PRMT1. By contrast, the majority of liver cancer cell lines with the PRMT1 high expression exhibited resistance to TC-E 5003.

FIGURE 3.

TC-E 5003, as a PRMT1 inhibitor, suppresses the HCC growth. (A) Long-term cell proliferation assays for TC-E 5003 (PRMT1 inhibitor) in liver cancer cell lines. Cells were treated with indicated concentrations of TC-E 5003. Long-term cell proliferation assays were measured by colony formation. (B, C) In short-term cell proliferation assays, cells were treated with indicated concentrations of TC-E 5003 for 3 days and detected by CCK8. IC50 values of TC-E 5003 were determined. (D–G) TC-E 5003 restrained tumor growth in the subcutaneous xenograft tumor model. Representative images of subcutaneous tumors (D). Mice body weight and tumor volume (E). Tumor volume growth curve (F). Immunohistochemical analysis for Ki67 in tumor tissues from the subcutaneous xenograft tumors (G). n.s., no significance. ***p < 0.001. Abbreviations: H4R3me2a, histone H4 at arginine 3; IC50, half maximal inhibitory concentration; PRMT1, protein arginine methyltransferase 1.

Next, we utilized nude mouse xenograft models to evaluate the in vivo antitumor effects of PRMT1 inhibitors. Results revealed that TC-E 5003 at a concentration of 100 mg/kg effectively suppressed the subcutaneous tumor growth. Mouse body weight, tumor weight, tumor growth curve, and immunohistochemical staining of Ki67 were measured (Figures 3D–G). Results demonstrated that the PRMT1 inhibitor remarkably impaired the growth of liver tumors without causing a significant reduction in mice body weight. These findings indicate that targeting PRMT1 may represent a promising therapeutic approach for HCC.

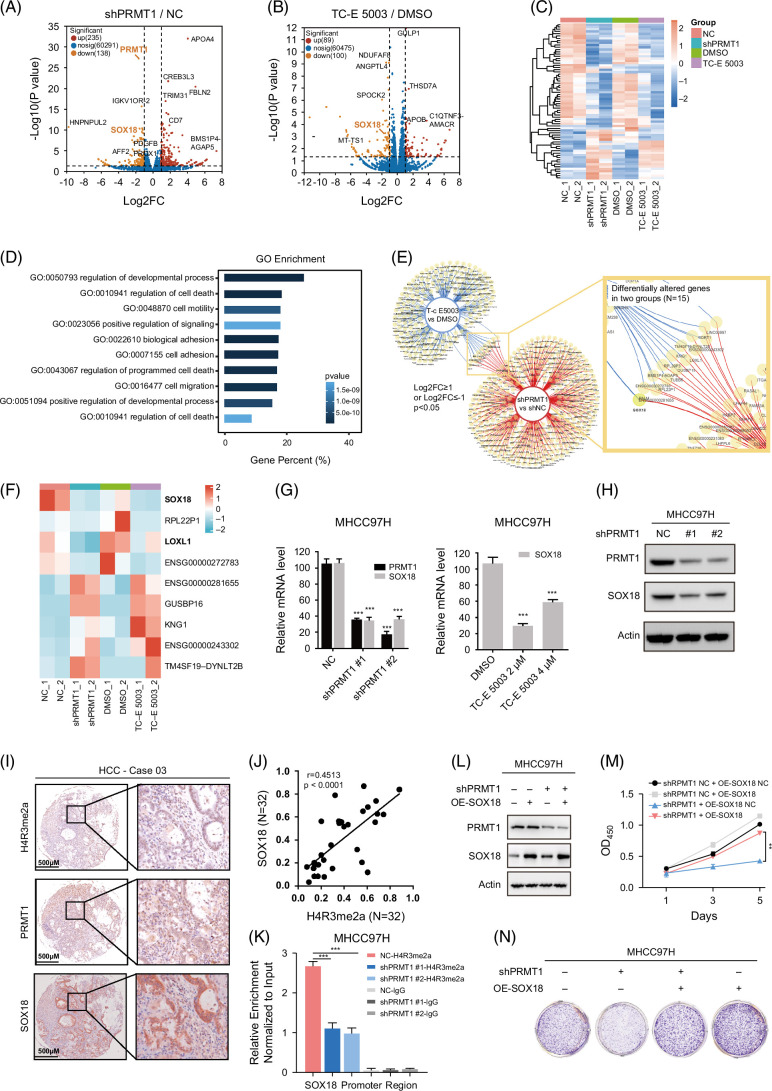

PRMT1 epigenetically regulates SOX18 to promote HCC proliferation

We performed RNA-seq analysis in MHCC97H cells with PRMT1 knockdown or TC-E 5003 treatment, respectively, to identify potential target genes and explore downstream signal pathways. The data of RNA-seq revealed dysregulated genes (Log2(Fold change) ≥1 or ≤−1, and p < 0.05) as shown in Figures 4A, B. Heatmap displaying the overall clustering feature for the groups of NC, shPRMT1, DMSO, and TC-E 5003 indicated that TC-E 5003 treatment effectively recapitulated effects of PRMT1-specific genetic ablation consistency within (Figure 4C). Meanwhile, principal component analysis demonstrated a satisfactory consistency within the sequencing results of the respective groups (Supplemental Figure S3A, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B888). Gene ontology enrichment analyses of differentially expressed genes identified that the regulation of developmental process and cell death was the top regulated pathway in shPRMT1 versus NC groups (Figure 4D), and gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) indicated significant changes in IL6-JAK-STAT3 signaling and epithelial to mesenchymal signaling induced by PRMT1 knockdown (Supplemental Figures S3B, C, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B888). Next, we identified 15 jointly changed genes in 2 RNA-seq systems by dynamic Venn diagram (Figure 4E). Heatmap shows the 9 changed genes with consistent trends and their expression differences among groups, and transcription factor SOX18 is the most significantly downregulated gene in PRMT1-depleted and TC-E 5003 treated cells (Figure 4F). We further analyzed the expressions of the 9 genes in paired samples from the TCGA-LIHC cohort, and results indicated that SOX18 displayed significant upregulations in tumor tissues (Supplemental Figure S3D, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B888). We performed RT-qPCR analysis to verify the downregulation of SOX18 mRNA in MHCC97H and HCCLM3 cells with PRMT1 knockdown or PRMT1 inhibitors treatment (Figure 4G and Supplemental Figure S3F, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B888). We found that the knockdown of PRMT1 also reduced the protein level of SOX18, indicating that PRMT1 is needed for SOX18 expression (Figure 4H). Subsequently, we generated the MHCC97H cells with SOX18 knockout to assess whether SOX18 could reciprocally regulate PRMT1. q-PCR analysis showed no significant change of PRMT1 expression in the MHCC97H cells with SOX18 knockdown (Supplemental Figure S3E, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B888).

FIGURE 4.

Enhanced H4R3me2a methylation at the promoter region of SOX18 stimulates HCC proliferation. (A, B) Volcano plots depicting differentially expressed genes identified by RNA-seq analysis in MHCC97H cells after knockdown of PRMT1 or treatment with PRMT1 inhibitor (TC-E 5003). The x-axis represented Log2 (Fold change), and the y-axis represented −Log10 (p value). Significant genes were defined as Log2 (Fold change) ≥1 or ≤−1, and p < 0.05. (C) Heatmap displaying the overall clustering feature of the 4 groups (NC, shPRMT1, DMSO, and TC-E 5003) based on RNA-seq data. (D) GO enrichment analysis of significantly changed genes from the shPRMT1 versus NC RNA-seq data. (E) Dynamic Venn diagram identified 15 changed genes between the shPRMT1 versus NC and TC-E 5003 versus DMSO group based on RNA-seq data. (F) Heatmap showing the 9 changed genes with consistent trends and their expression differences among groups. (G, H) Downregulation of SOX18 expression was validated by western blotting and q-PCR in MHCC97H cells with PRMT1 knockdown. (I) Representative images of immunohistochemical analysis for H4R3me2a, PRMT1, and SOX18 in 32 paired patients with HCC. (J) Correlation between H4R3me2a and SOX18 normalized H-scores in HCC tissues. Pearson correlation coefficient, r = 0.4513, p < 0.0001. (K) Differential levels of H4R3me2a binding to the promoter region of SOX18 were analyzed by Chip-qPCR in MHCC97H cells treated with NC or shPRMT1. (L–N) Long-term cell proliferation assay and western blotting of PRMT1 and SOX18 in MHCC97H cells treated with NC or shPRMT1 and oe-SOX18. n.s., no significance. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Abbreviations: Chip, chromatin immunoprecipitation; GO, gene ontology; H4R3me2a, histone H4 at arginine 3; PRMT1, protein arginine methyltransferase 1; q-PCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

Subsequently, we examined gene expressions in our clinical samples. Results showed that SOX18 was significantly upregulated in our cohort of the 32 paired samples of patients with HCC (Supplemental Figure S3G, H, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B888). Immunohistochemical analysis for H4R3me2a, PRMT1, and SOX18 showed a close relationship among 3 proteins in HCC tissues from our cohort of 32 paired samples of patients with HCC as shown in representative images of Figure 4I. The correlation between H4R3me2a and SOX18 in HCC tissues is shown in Figure 4J (r = 0.4513, p<0.0001). Based on these findings and previous studies,10,20 we hypothesized that PRMT1 may enhance the transcription of SOX18 by modulating the H4R3me2a mark. Our data of Chip-qPCR demonstrated the deposition of H4R3me2a at the SOX18 gene promoter in MHCC97H cells, while downregulation of PRMT1 dramatically reduced H4R3me2a enrichment at the SOX18 promoter region (Figure 4k). As observed in the long-term and short-term cell proliferation assays, the introduction of SOX18 partially reversed the inhibition of cell proliferation induced by PRMT1 knockdown in MHCC97H (Figures 4L–N). These data indicate that PRMT1 promotes cell proliferation by enhancing H4R3me2a deposition at the SOX18 promoter and activating its transcription.

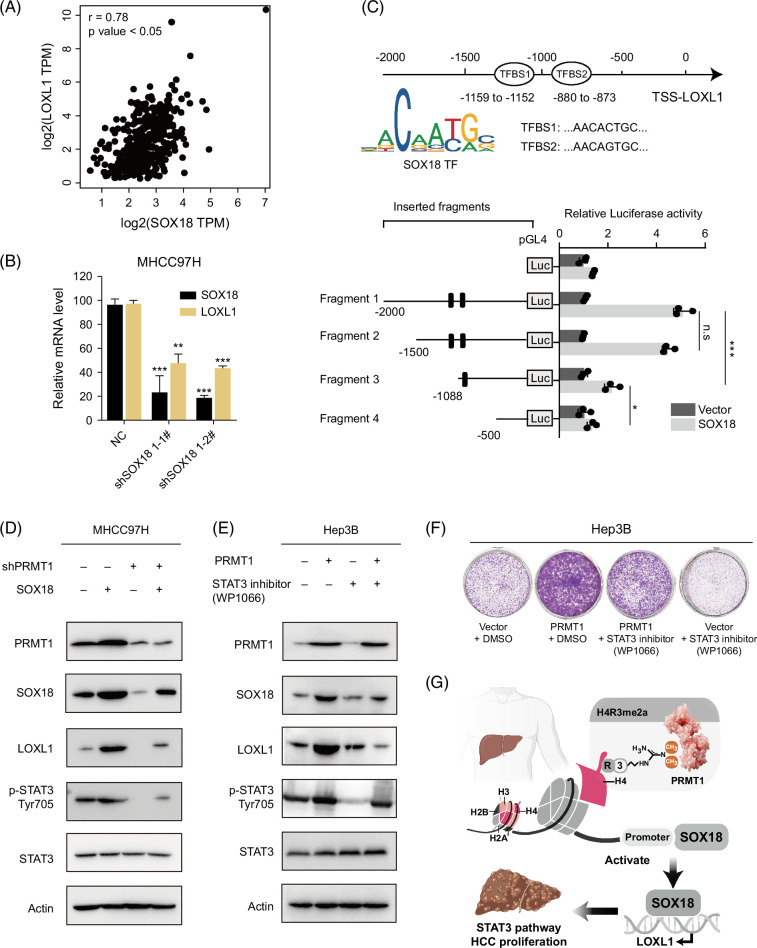

LOXL1 is identified as a direct target of SOX18 and promotes HCC through STAT3 signaling

As a transcription factor, previous research has reported the oncogenic role of SOX18 in various cancers.21,22 However, research on the direct binding of SOX18 to downstream genes, particularly the effects of PRMT1-mediated SOX18 regulation, remains limited. Bioinformatics analyses have identified the top 10 hub genes (POSTN, BGN, MMP2, THBS2, CD34, ESR1, VEGFC, AEBP1, CLDN5, and LOXL1), which have been reported to interact with the SOX family in liver cancer. 23 Interestingly, our data of RNA-seq show that LOXL1 is contained among the 9 consistently changed genes (Figure 4F). We retrieved the expression profiles of SOX18 and LOXL1 from the TCGA-LIHC data set and conducted correlation analysis. Results demonstrated a significant positive correlation in the expression of SOX18 and LOXL1 (Figure 5A). Furthermore, we observed a marked decrease in mRNA levels of LOXL1 after SOX18 knockdown in MHCC97H cells, suggesting that SOX18, as a transcription factor, may facilitate the transcription of LOXL1 (Figure 5B). We used the online database JASPAR (https://jaspar.genereg.net/) to predict the binding region of SOX18 to the promoter of LOXL1, and the results revealed a potential transcription factor binding site. Based on the scoring and results of matrix overlap (MA1563.1 and MA1563.2), we selected 2 potential transcription factor binding sites as shown in Figure 5C. A variety of reporter plasmids for truncated LOXL1 promoters were constructed. Results showed that SOX18 could influence the luciferase activities of the LOXL1 promoter and the transcription factor binding site 1 might be the most probable binding site (Figure 5C).

FIGURE 5.

PRMT1-H4R3me2a-SOX18 promotes liver cancer proliferation through the LOXL1/STAT3 signaling. (A) Correlation between SOX18 and LOXL1 mRNA levels in TCGA-LIHC HCC tissues. (B) Downregulation of LOXL1 expression was validated by q-PCR in MHCC97H cells with SOX18 knockdown. (C) Diagram of predicted transcription factor SOX18 binding sites to the LOXL1 promoter region. The activities of serially truncated LOXL1 promoter reporter vectors in the 293T cells cotransfected with PGMLV-CMV-SOX18. (D, E) Protein levels of PRMT1, SOX18, LOXL1, p-STAT3, and STAT3 in the indicated MHCC97H cells and Hep3B cells. (F) Long-term cell proliferation assay in indicated MHCC97H cells treated with DMSO or STAT3 inhibitor (WP1066). (G) Schematic diagram of this study. n.s., no significance. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Abbreviations: H4R3me2a, histone H4 at arginine 3; PRMT1, protein arginine methyltransferase 1; q-PCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

Finally, we aimed to briefly analyze the key signaling pathway affected by PRMT1-mediated H4R3me2a in liver cancer proliferation. Our GSEA analysis indicated significant enrichments in IL6/JAK/STAT3 signaling induced by PRMT1 (Supplemental Figure S3B, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B888). Interestingly, previous studies have linked the oncogenic roles of SOX18 and LOXL1 to the STAT3 signaling pathway. For example, research indicated downregulation of SOX18 inhibits the proliferation, migration, and invasion of laryngeal cancer cells through the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway. 24 Another study uncovered that miR-7-5p targets SOX18 to suppress the gp130/JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway, thereby exerting its inhibitory effect in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. 25 For LOXL1, the study indicated that LOXL1-AS1 promotes the progression of cholangiocarcinoma by inhibiting JAK2 ubiquitination through the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway, and the LOXL1-AS1/miR-515-5p/STAT3 positive feedback loop plays a vital role in atherosclerosis.26,27 Most importantly, recent studies have emphasized the role of STAT3 in liver cancer.28,29 Therefore, we aimed to investigate the alterations of STAT3 signaling in our research. Our results exhibited that PRMT1 knockdown inactivates the STAT3 pathway in MHC97H cells, while the overexpression of SOX18 could partially restore the levels of p-STAT3 (Figure 5D). The levels of p-STAT3 were effectively increased in Hep3B cells with PRMT1 overexpression while restored with the treatment of STAT3 inhibitor (WP1066) (Figure 5E). WP1066 could partially inhibit the PRMT1-induced proliferation in HCC (Figure 5F). These results indicate that SOX18 may exert an oncogenic effect by directly binding to LOXL1 and activating its transcription, leading to HCC promotion through STAT3 signaling in the process of PRMT1-mediated HCC proliferation (Figure 5G).

DISCUSSION

This study underscores the critical role of the histone modification H4R3me2a and its regulatory enzyme PRMT1 in the progression of HCC. Our findings first reveal that the upregulation of H4R3me2a is significantly associated with poor prognosis in patients with HCC.

This is crucial for revealing the clinical relevance of specific global histone modifications to liver cancer, facilitating the discovery of new liver cancer targets.

In general, histone H4R3me2a modification plays crucial roles in regulating gene expression and is closely associated with tumorigenesis, making it a promising biomarker for tumor diagnosis.3,4,30 For instance, Tudor domain-containing protein 3 (TDRD3) functions as a methylarginine “reader” recognizing methylated arginine residues to activate transcription. Its interaction with histone H4R3me2a facilitates the recruitment of methylated ubiquitin-specific protease 9 (USP9X), which is vital for the stability of TDRD3. 31 Furthermore, PRMT1-mediated H4R3me2a modification is linked to the regulation of EGFR expression in colorectal cancer and plays a role in the transcriptional activity of the MLL-EEN complex in acute myeloid leukemia, thereby promoting tumor growth.10,32 Alterations in histone modifications including H4R3me2a may serve as biomarkers for the diagnosis and prognosis of prostate cancer, suggesting that therapies targeting this modification could inhibit tumor growth and metastasis.8,33,34 Thus, H4R3me2a exhibits significant values in development and progression as well as in the clinical translation for human cancers.

As previously mentioned, PRMT1 is the most important member of the type I PRMT family, accounting for 85% of type I PRMT activity in mammals. 35 PRMT1 plays a role in regulating the compaction of chromatin, controlling chromatin remodeling complexes, and recruiting transcription factors, thereby influencing the activity of downstream regulatory factors. 36 Human PRMT1 arginine methyltransferase can target histone (producing the H4R3me2a mark) or non-histone substrates, affecting the function of the relevant substrates by methylating specific arginine sites on proteins.36,37 But the mechanism by which PRMT1 is elevated in tumors is not well understood. In general, the main factors that may contribute to the overexpression of PRMT1 include gene amplification, transcriptional regulation, and posttranscriptional regulation.36,38 According to previous research, the upregulated level of PRMT1 can be regulated by downregulated levels of miR-503 and E3 ubiquitin ligase F-box-only protein 7 (FBXO7) and upregulated levels of Thymidine kinase 1 (TK1) in liver cancer.39–41 In detail, TK1 could directly bind to PRMT1 and stabilize it by interrupting its interactions with tripartite-motif-containing 48 (TRIM48), which inhibits its ubiquitination-mediated degradation. 39 miR-503 was able to reduce the expression of PRMT1 at the levels of mRNA and protein in HCC. 40 The FBXO7 inhibits serine synthesis in HCC by binding PRMT1 inducing lysine 37 ubiquitination, and promoting proteosomal degradation of PRMT1. 41

In our study, we focus on the role of PRMT1-mediated histone H4R3me2a modifications in regulating the transcription of key downstream genes that influence HCC proliferation. However, PRMT1 also exerts its effects through the direct methylation of protein components. For instance, PRMT1 can affect the sensitivity to chemotherapy by modulating the transcription of EGFR or the methylation sites on the extracellular domain of the EGFR protein.10,11,42,43 In future studies, we plan to conduct a broader investigation, such as combining unbiased proteomic methylation screens, to further elucidate the mechanisms by which PRMT1 influences the proliferation of liver cancer.

In addition, the effectiveness of pharmacological inhibitors of PRMT1 in restraining HCC growth highlights the therapeutic potential of targeting this pathway. The inhibition of PRMT1 not only reduced H4R3me2a levels but also significantly curtailed the proliferation of HCC cells. These results suggest that PRMT1 inhibitors could serve as a promising approach for HCC treatment. GSK3368715 is a first-in-class reversible inhibitor of type I protein methyltransferases, demonstrating anticancer activity in preclinical studies. A phase 1 study (NCT03666988) was conducted to evaluate the safety, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and preliminary efficacy of GSK3368715 in adult patients with advanced solid tumors. However, based on a higher-than-expected incidence of adverse events, limited target engagement at lower doses, and a lack of observed clinical efficacy, the risk/benefit analysis led to the premature termination of this study. 44 Therefore, there is an urgent need to find more effective and safer PRMT1 inhibitors with anticancer activity.

The elucidation of SOX18 as a downstream effector regulated epigenetically by PRMT1-mediated H4R3me2a modification adds another layer of complexity to the regulatory networks influencing HCC progression. The transcription factor SOX18, a member of the SOX (SRY-related HMG box) family, exhibits predominant expression in endothelial cells and regulates the expression of genes involved in vascular development and angiogenesis.45,46 Moreover, SOX18 has been implicated in the progression of cancers, such as breast, prostate, and liver cancer. 23 Previous studies have indicated that SOX18 promotes cell proliferation and inhibits apoptosis in HCC, the precise mechanism underlying its oncogenic function remains largely unexplored.47,48 Research indicates that, under conditions of high FGF19 expression, FGF19 upregulates the expression of SOX18. The overexpression of SOX18 further promotes liver cancer metastasis by upregulating metastasis-related genes, including fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 and Fms-related tyrosine kinase 4 (FLT4). 49 Although the potential role of the FGF19-SOX18-fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 positive feedback loop in HCC metastasis has been revealed in previous studies, the regulatory mechanism of SOX18 in the context of PRMT1 alterations has not been reported yet. To our knowledge, there have been no previous studies on the oncogenic role of PRMT1 through SOX18 in HCC. Our identification of LOXL1 as a direct target of SOX18 further establishes a novel link between histone modification and gene expression regulation in HCC, enhancing our understanding of the transcriptional networks in liver cancer.

In conclusion, our research provides compelling evidence for the role of PRMT1 and H4R3me2a in HCC and highlights the therapeutic potential of targeting this epigenetic modification. Future studies should focus on further delineating the molecular mechanisms by which PRMT1 and H4R3me2a influence HCC, as well as on expanding the clinical samples to further investigate clinical significance between H4R3me2a modification and HCC clinicopathological information.

Supplementary Material

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jing Ling: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, validation, visualization, writing—original draft, and project administration. Siying Wang: project administration, formal analysis, validation, visualization, and writing—review and editing. Chenhe Yi: data curation, project administration, resources, and writing—review and editing. Xingling Zheng: conceptualization, formal analysis, project administration, and visualization. Yangyang Zhou: data curation, project administration, supervision, and validation. Shunjia Lou: data curation, validation, and visualization. Haoyu Li: formal analysis and validation. Ruobing Yu: project administration, validation, and visualization. Wei Wu: formal analysis and visualization. Qiangxin Wu: visualization. Xiaoxiao Sun: project administration and visualization. Yuanyuan Lv: data curation and project administration. Huijue Zhu: project administration. Qi Li: funding acquisition, project administration, and resources. Haojie Jin: funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, resources, and writing—review and editing. Jinhong Chen: resources, supervision, and writing—review and editing. Jiaojiao Zheng: conceptualization, formal analysis, project administration, writing—review and editing, and supervision. Wenxin Qin: conceptualization, resources, writing—review and editing, and funding acquisition.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was funded by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82330095, 81920108025, 82073214, and 82473306) and the State Key Laboratory of Systems Medicine for Cancer (ZZ-94-2301).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts to report.

Footnotes

Jing Ling, Siying Wang, and Chenhe Yi contributed equally.

Abbreviations: EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; H4R3me2a, histone H4 at arginine 3; PRMT1, protein arginine methyltransferase 1.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website, www.hepcommjournal.com.

Contributor Information

Jing Ling, Email: lingjing@sjtu.edu.cn.

Siying Wang, Email: 1773960824@sjtu.edu.cn.

Chenhe Yi, Email: 924534073@qq.com.

Xingling Zheng, Email: xlzzheng@ucdavis.edu.

Yangyang Zhou, Email: yqyoungchou@163.com.

Shunjia Lou, Email: lsj_0129@outlook.com.

Haoyu Li, Email: lihaoyu196@163.com.

Ruobing Yu, Email: robyn-y@sjtu.edu.cn.

Wei Wu, Email: wuwei294265864@sjtu.edu.cn.

Qiangxin Wu, Email: qiangxinwu@sjtu.edu.cn.

Xiaoxiao Sun, Email: smily5182@163.com.

Yuanyuan Lv, Email: yylv@shsci.org.

Huijue Zhu, Email: hjzhu@shsci.org.

Qi Li, Email: Leeqi2001@hotmail.com.

Haojie Jin, Email: hjjin1986@shsci.org.

Jinhong Chen, Email: jinhongch@hotmail.com.

Jiaojiao Zheng, Email: zhengjiaojiao@bjmu.edu.cn.

Wenxin Qin, Email: wxqin@sjtu.edu.cn.

REFERENCES

- 1. Siegel R, Giaquinto A, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:12–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anwanwan D, Singh SK, Singh S, Saikam V, Singh R. Challenges in liver cancer and possible treatment approaches. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2020;1873:188314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Esteller M. Cancer epigenomics: DNA methylomes and histone-modification maps. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:286–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hamamoto R, Nakamura Y. Dysregulation of protein methyltransferases in human cancer: An emerging target class for anticancer therapy. Cancer Sci. 2016;107:377–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fernández-Barrena M, Arechederra M, Colyn L, Berasain C, Avila M. Epigenetics in hepatocellular carcinoma development and therapy: The tip of the iceberg. JHEP Rep Innov Hepatol. 2020;2:100167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bayo J, Fiore E, Dominguez L, Real A, Malvicini M, Rizzo M, et al. A comprehensive study of epigenetic alterations in hepatocellular carcinoma identifies potential therapeutic targets. J Hepatol. 2019;71:78–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beacon T, Xu W, Davie J. Genomic landscape of transcriptionally active histone arginine methylation marks, H3R2me2s and H4R3me2a, relative to nucleosome depleted regions. Gene. 2020;742:144593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Seligson D, Horvath S, Shi T, Yu H, Tze S, Grunstein M, et al. Global histone modification patterns predict risk of prostate cancer recurrence. Nature. 2005;435:1262–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Feng G, Chen C, Luo Y. PRMT1 accelerates cell proliferation, migration, and tumor growth by upregulating ZEB1/H4R3me2as in thyroid carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2023;50:210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yao B, Gui T, Zeng X, Deng Y, Wang Z, Wang Y, et al. PRMT1-mediated H4R3me2a recruits SMARCA4 to promote colorectal cancer progression by enhancing EGFR signaling. Genome Med. 2021;13:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zeng X, Yao B, Liu J, Gong G, Liu M, Li J, et al. The SMARCA4 mutation facilitates chromatin remodeling and confers PRMT1/SMARCA4 inhibitors sensitivity in colorectal cancer. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2023;7:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lin W, Gary J, Yang M, Clarke S, Herschman H. The mammalian immediate-early TIS21 protein and the leukemia-associated BTG1 protein interact with a protein-arginine N-methyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:15034–15044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Weiss V, McBride A, Soriano M, Filman D, Silver P, Hogle J. The structure and oligomerization of the yeast arginine methyltransferase, Hmt1. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:1165–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huang S, Litt M, Felsenfeld G. Methylation of histone H4 by arginine methyltransferase PRMT1 is essential in vivo for many subsequent histone modifications. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1885–1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ryu J, Kim S, Son M, Jeon S, Oh J, Lim J, et al. Novel prognostic marker PRMT1 regulates cell growth via downregulation of CDKN1A in HCC. Oncotarget. 2017;8:115444–115455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wei H, Liu Y, Min J, Zhang Y, Wang J, Zhou M, et al. Protein arginine methyltransferase 1 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition via TGF-β1/Smad pathway in hepatic carcinoma cells. Neoplasma. 2019;66:918–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Haojie J, Yaoping S, Yuanyuan L, Shengxian Y, Christel FAR, Cor L, et al. EGFR activation limits the response of liver cancer to lenvatinib. Nature. 2021;595:730–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Quan Z, Gerhard R, Yuen TT, Haitao L, Robert LM, Richard JS, et al. PRMT5-mediated methylation of histone H4R3 recruits DNMT3A, coupling histone and DNA methylation in gene silencing. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:304–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cheng D, Yadav N, King R, Swanson M, Weinstein E, Bedford M. Small molecule regulators of protein arginine methyltransferases. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:23892–23899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Barrero M, Malik S. Two functional modes of a nuclear receptor-recruited arginine methyltransferase in transcriptional activation. Mol Cell. 2006;24:233–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen C, Zheng H, Luo Y, Kong Y, An M, Li Y, et al. SUMOylation promotes extracellular vesicle-mediated transmission of lncRNA ELNAT1 and lymph node metastasis in bladder cancer. J Clin Invest. 2021;131:e146431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moustaqil M, Fontaine F, Overman J, McCann A, Bailey T, Rudolffi Soto P, et al. Homodimerization regulates an endothelial specific signature of the SOX18 transcription factor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:11381–11395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Higashijima Y, Kanki Y. Molecular mechanistic insights: The emerging role of SOXF transcription factors in tumorigenesis and development. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020;67:39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xu Y, Zhang Q, Zhou J, Li Z, Guo J, Wang W, et al. Down-regulation of SOX18 inhibits laryngeal carcinoma cell proliferation, migration, and invasion through JAK2/STAT3 signaling. Biosci Rep. 2019;39:BSR20182480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhu W, Wang Y, Zhang D, Yu X, Leng X. MiR-7-5p functions as a tumor suppressor by targeting SOX18 in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;497:963–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yu S, Gao X, Liu S, Sha X, Zhang S, Zhang X, et al. LOXL1-AS1 inhibits JAK2 ubiquitination and promotes cholangiocarcinoma progression through JAK2/STAT3 signaling. Cancer Gene Ther. 2024;31:552–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Xie Q, Li F, Shen K, Luo C, Song G. LOXL1-AS1/miR-515-5p/STAT3 positive feedback loop facilitates cell proliferation and migration in atherosclerosis. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2020;76:151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jiang Y, Xu Y, Zhu C, Xu G, Xu L, Rao Z, et al. STAT3 palmitoylation initiates a positive feedback loop that promotes the malignancy of hepatocellular carcinoma cells in mice. Sci Signal. 2023;16:eadd2282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang X, Hu R, Song Z, Zhao H, Pan Z, Feng Y, et al. Sorafenib combined with STAT3 knockdown triggers ER stress-induced HCC apoptosis and cGAS-STING-mediated anti-tumor immunity. Cancer Lett. 2022;547:215880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li X, Hu X, Patel B, Zhou Z, Liang S, Ybarra R, et al. H4R3 methylation facilitates beta-globin transcription by regulating histone acetyltransferase binding and H3 acetylation. Blood. 2010;115:2028–2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Narayanan N, Wang Z, Li L, Yang Y. Arginine methylation of USP9X promotes its interaction with TDRD3 and its anti-apoptotic activities in breast cancer cells. Cell Discov. 2017;3:16048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cheung N, Fung T, Zeisig B, Holmes K, Rane J, Mowen K, et al. Targeting aberrant epigenetic networks mediated by PRMT1 and KDM4C in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2016;29:32–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Eram M, Shen Y, Szewczyk M, Wu H, Senisterra G, Li F, et al. A potent, selective, and cell-active inhibitor of human type I protein arginine methyltransferases. ACS Chem Biol. 2016;11:772–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Heinke R, Spannhoff A, Meier R, Trojer P, Bauer I, Jung M, et al. Virtual screening and biological characterization of novel histone arginine methyltransferase PRMT1 inhibitors. ChemMedChem. 2009;4:69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tang J, Frankel A, Cook R, Kim S, Paik W, Williams K, et al. PRMT1 is the predominant type I protein arginine methyltransferase in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:7723–7730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Thiebaut C, Eve L, Poulard C, Le Romancer M. Structure, activity, and function of PRMT1. Life (Basel, Switzerland). 2021;11:1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhu Y, Xia T, Chen D, Xiong X, Shi L, Zuo Y, et al. Promising role of protein arginine methyltransferases in overcoming anti-cancer drug resistance. Drug Resist Updat. 2024;72:101016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Blanc R, Richard S. Arginine methylation: The coming of age. Mol Cell. 2017;65:8–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Qing L, Liren Z, Qin Y, Mei L, Xiongxiong P, Jiali X, et al. Thymidine kinase 1 drives hepatocellular carcinoma in enzyme-dependent and -independent manners. Cell Metab. 2023;35:912–927.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li B, Liu L, Li X, Wu L. miR-503 suppresses metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma cell by targeting PRMT1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;464:982–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Luo L, Wu X, Fan J, Dong L, Wang M, Zeng Y, et al. FBXO7 ubiquitinates PRMT1 to suppress serine synthesis and tumor growth in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2024;15:4790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Samyuktha S, Solène H, Amélie B, Fariba N, Rayan D, Coralie P, et al. PRMT1 regulates EGFR and Wnt Signaling pathways and is a promising target for combinatorial treatment of breast cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. David ME, Elizabeth B. Old dog, new tricks: Extracellular domain arginine methylation regulates EGFR function. PG - 4320-2. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:4320–4322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. El-Khoueiry A, Clarke J, Neff T, Crossman T, Ratia N, Rathi C, et al. Phase 1 study of GSK3368715, a type I PRMT inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Br J Cancer. 2023;129:309–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. François M, Caprini A, Hosking B, Orsenigo F, Wilhelm D, Browne C, et al. Sox18 induces development of the lymphatic vasculature in mice. Nature. 2008;456:643–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Grimm D, Bauer J, Wise P, Krüger M, Simonsen U, Wehland M, et al. The role of SOX family members in solid tumours and metastasis. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020;67:122–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wang G, Wei Z, Jia H, Zhao W, Yang G, Zhao H. Knockdown of SOX18 inhibits the proliferation, migration and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncol Rep. 2015;34:1121–1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Qin S, Liu G, Jin H, Chen X, He J, Xiao J, et al. The dysregulation of SOX family correlates with DNA methylation and immune microenvironment characteristics to predict prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Dis Markers. 2022;2022:2676114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chen J, Du F, Dang Y, Li X, Qian M, Feng W, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 19-mediated up-regulation of SYR-related high-mobility group box 18 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis by transactivating fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 and Fms-related tyrosine kinase 4. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md). 2020;71:1712–1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]