Abstract

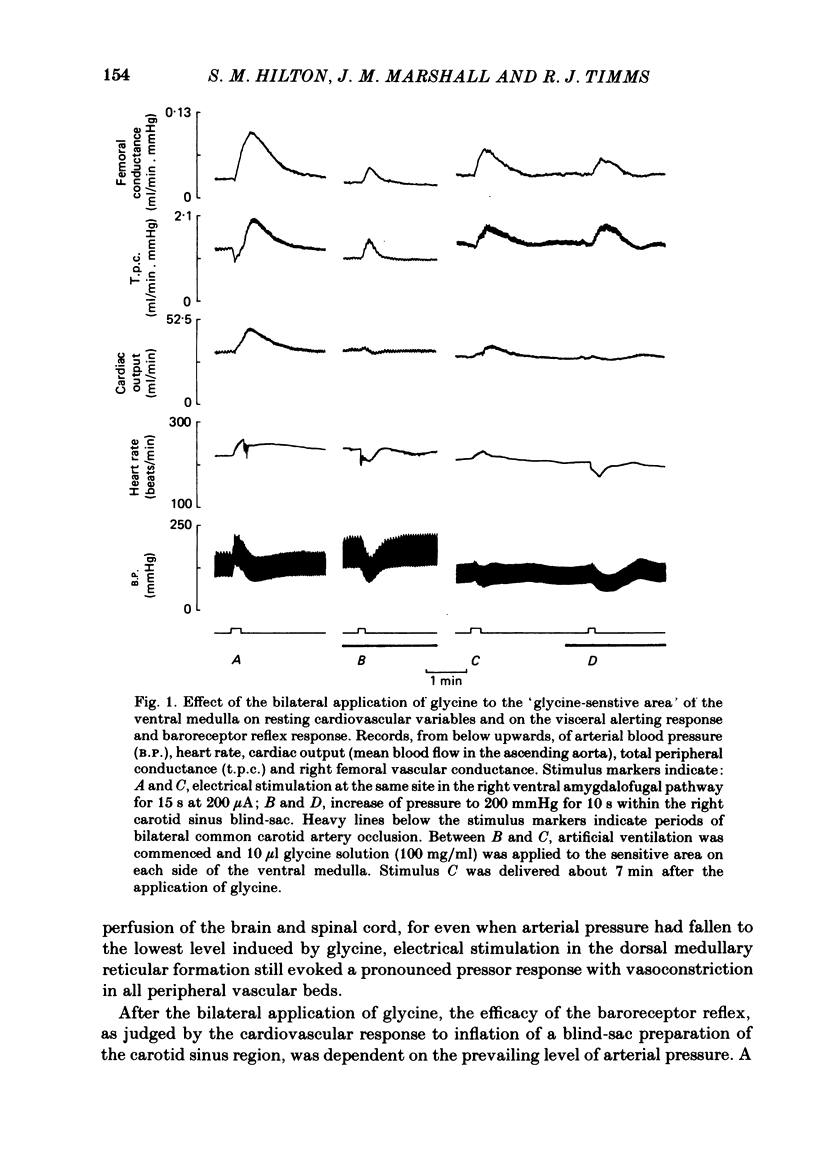

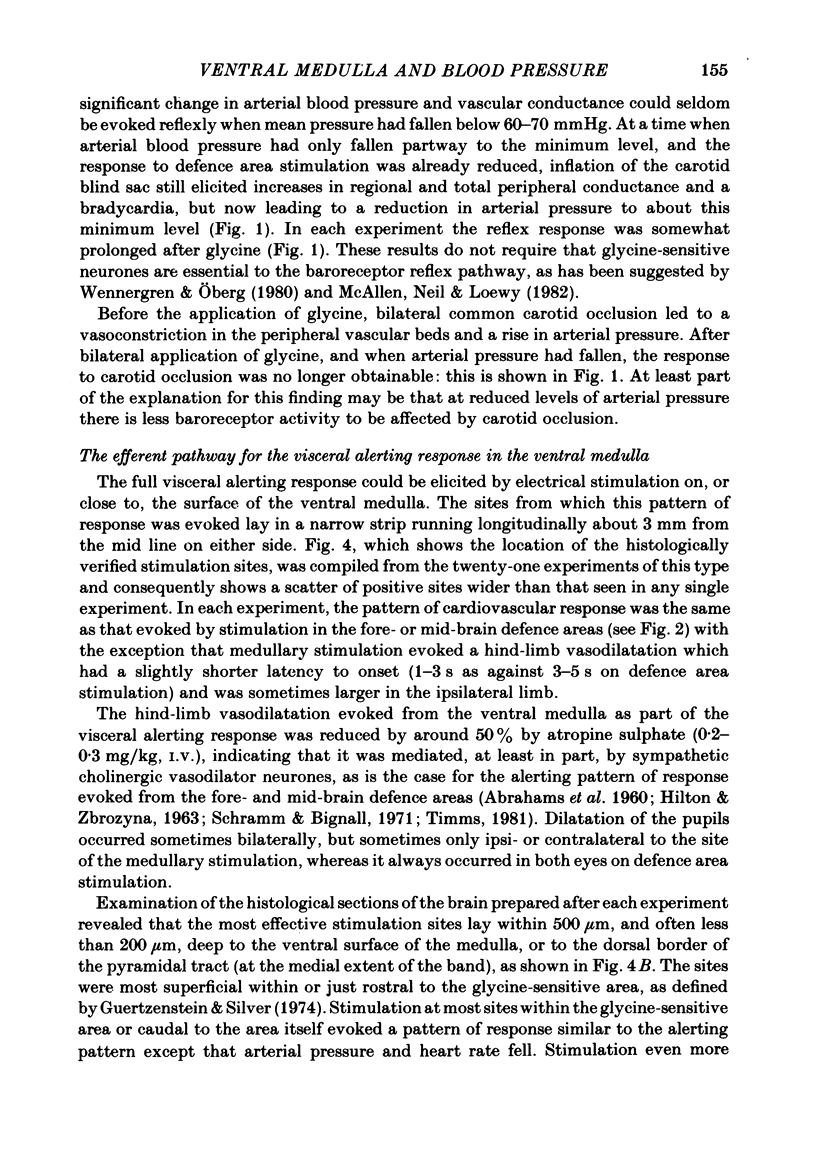

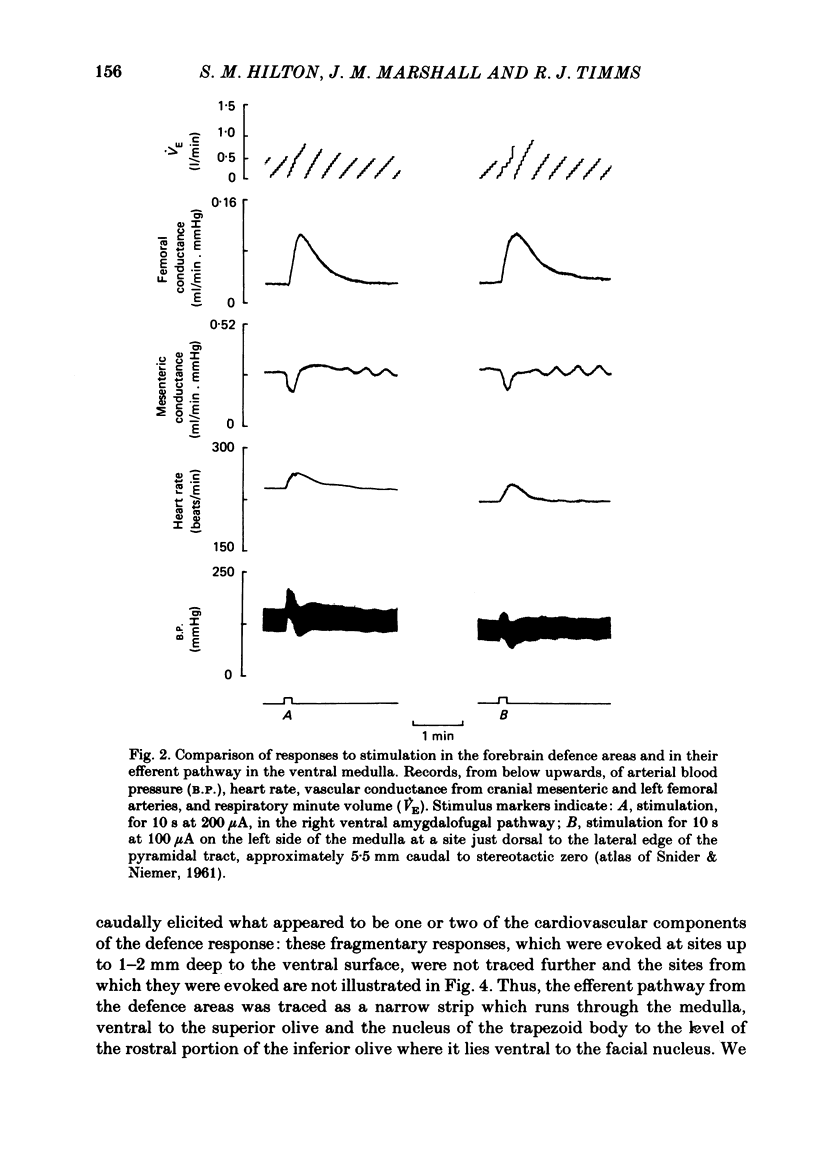

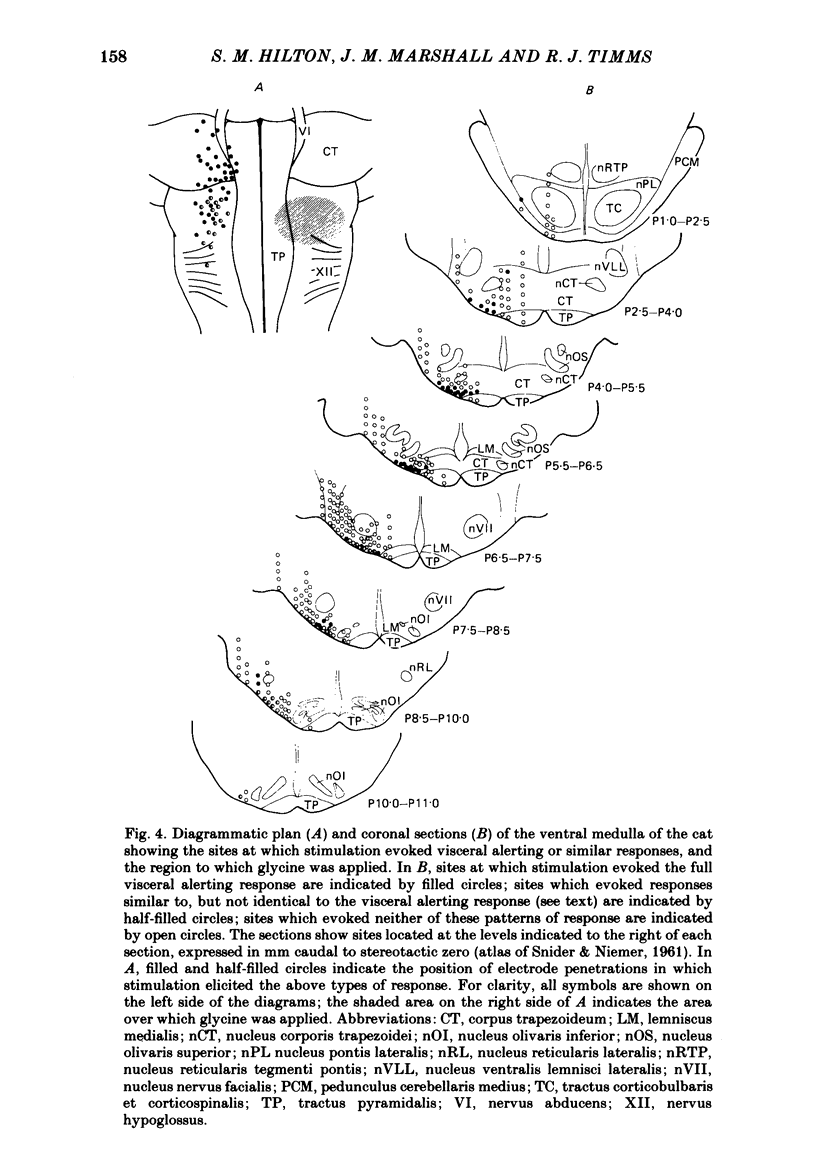

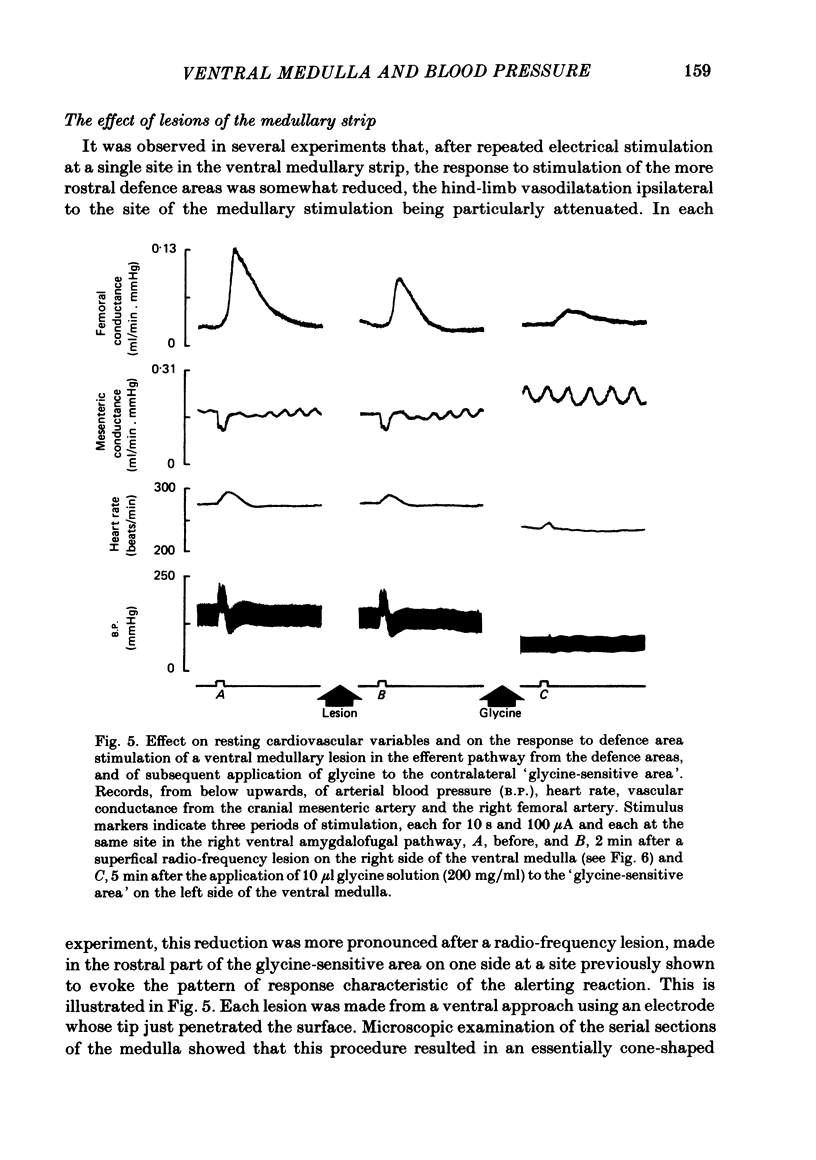

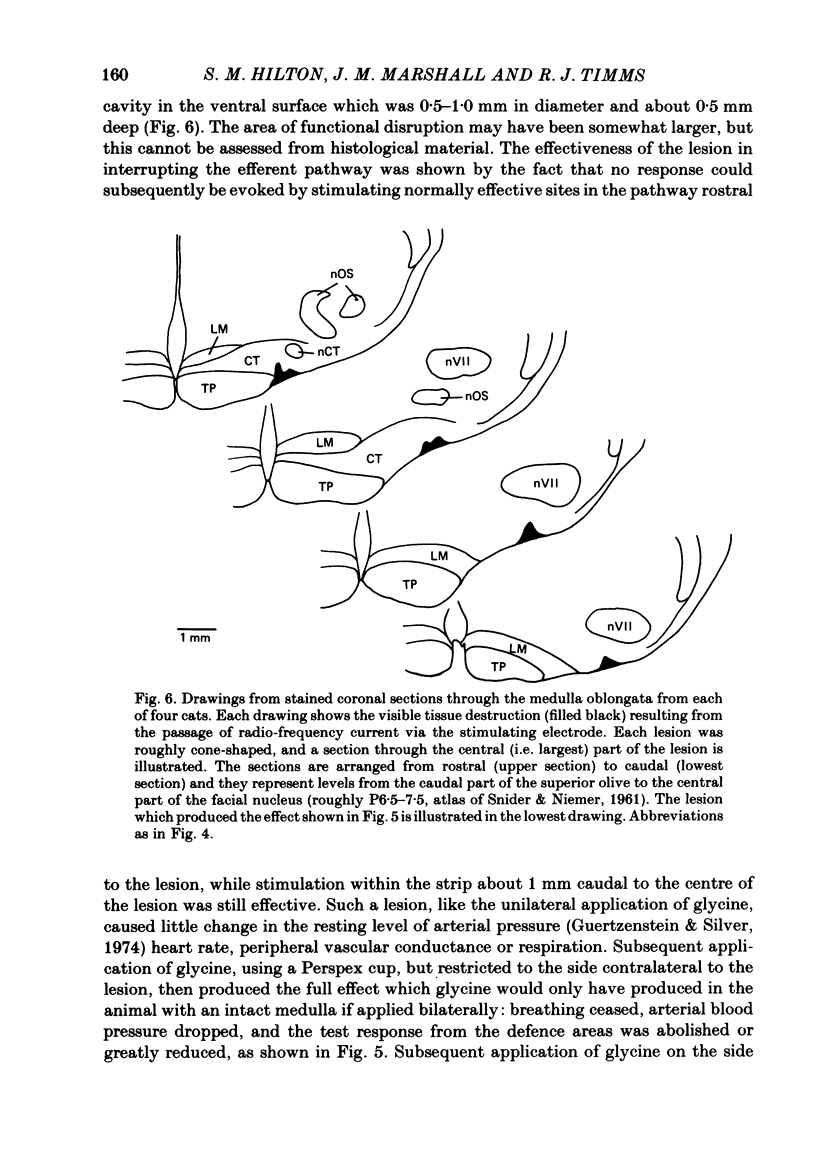

In cats anaesthetized with Althesin, the efferent descending pathway from the brain-stem defence areas has been traced through the medulla by identifying sites at which electrical stimulation evoked the characteristic pattern of the visceral alerting (defence) response. This response includes an increase in arterial blood pressure resulting from increased heart rate and cardiac output and vasoconstriction in renal and splanchnic beds, accompanied by active vasodilation in skeletal muscle. The efferent pathway runs as a narrow strip, about 3 mm from the mid line, ventral to the superior olive and the nucleus of the trapezoid body, extending caudally to the rostral portion of the inferior olive where it lies ventral to the facial nucleus. It was found to lie very close to the ventral medullary surface just rostral to and within the area at which bilateral topical application of glycine results in a profound fall in arterial blood pressure and cessation of respiration. On bilateral application of glycine to the sensitive area of the ventral medulla, the visceral alerting response evoked by stimulation in the defence areas of the amygdalo-hypothalamic complex, or the mid-brain central grey or tegmentum, was attenuated in parallel with the fall in arterial pressure, the vasoconstrictor responses being most strongly reduced. As soon as arterial blood pressure had fallen to its lowest level the visceral alerting response was virtually abolished. A small radio-frequency lesion made in the ventral medullary efferent pathway, in the rostral part of the 'glycine-sensitive area', had the same effect as that produced by unilateral application of glycine: it resulted in little respiratory or cardiovascular effect itself, but application of glycine to the contralateral area then produced the full effect otherwise seen only on bilateral application of glycine. It is suggested (1) that the effects of glycine result from blockade of a synaptic relay, close to the ventral surface of the medulla, in the efferent pathway from the defence areas to the preganglionic sympathetic neurones, and (2) that the neurones which receive an input from the alerting (defence) areas normally provide an essential, tonic excitatory drive to the sympathetic output and probably to respiration also. After sudden withdrawal of this drive, vasomotor tone and the normal level of arterial blood pressure are not maintained.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- ABRAHAMS V. C., HILTON S. M. THE ROLE OF ACTIVE MUSCLE VASODILATATION IN THE ALERTING STAGE OF THE DEFENCE REACTION. J Physiol. 1964 Jun;171:189–202. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1964.sp007371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ABRAHAMS V. C., HILTON S. M., ZBROZYNA A. Active muscle vasodilatation produced by stimulation of the brain stem: its significance in the defence reaction. J Physiol. 1960 Dec;154:491–513. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1960.sp006593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARONOW S. The use of radio-frequency power in making lesions in the brain. J Neurosurg. 1960 May;17:431–438. doi: 10.3171/jns.1960.17.3.0431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caraffa-Braga E., Granata L., Pinotti O. Changes in blood-flow distribution during acute emotional stress in dogs. Pflugers Arch. 1973 Mar 30;339(3):203–216. doi: 10.1007/BF00587372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai C. Y., Wang S. C. Integration of sympathetic cardiovascular mechanisms in medulla oblongata of the cat. Am J Physiol. 1968 Dec;215(6):1310–1315. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1968.215.6.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherniack N. S., von Euler C., Homma I., Kao F. F. Graded changes in central chemoceptor input by local temperature changes on the ventral surface of medulla. J Physiol. 1979 Feb;287:191–211. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cragg P., Patterson L., Purves M. J. The pH of brain extracellular fluid in the cat. J Physiol. 1977 Oct;272(1):137–166. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp012038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldberg W., Guertzenstein P. G. A vasodepressor effect of pentobarbitone sodium. J Physiol. 1972 Jul;224(1):83–103. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GREEN J. D. A simple microelectrode for recording from the central nervous system. Nature. 1958 Oct 4;182(4640):962–962. doi: 10.1038/182962a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guertzenstein P. G. Blood pressure effects obtained by drugs applied to the ventral surface of the brain stem. J Physiol. 1973 Mar;229(2):395–408. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guertzenstein P. G., Hilton S. M., Marshall J. M., Timms R. J. Experiments on the origin of vasomotor tone [proceedings]. J Physiol. 1978 Feb;275:78P–79P. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guertzenstein P. G., Silver A. Fall in blood pressure produced from discrete regions of the ventral surface of the medulla by glycine and lesions. J Physiol. 1974 Oct;242(2):489–503. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HILTON S. M., ZBROZYNA A. W. Amygdaloid region for defence reactions and its efferent pathway to the brain stem. J Physiol. 1963 Jan;165:160–173. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1963.sp007049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna B. D., Lioy F., Polosa C. The effect of cold blockade of the medullary chemoreceptors on the CO2 modulation of vascular tone and heart rate. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1979 May;57(5):461–468. doi: 10.1139/y79-070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton S. M., Marshall J., Timms R. J. The central nervous regulation of arterial blood pressure. Acta Physiol Pol. 1980;31 (Suppl 20):133–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton S. M. Ways of viewing the central nervous control of the circulation--old and new. Brain Res. 1975 Apr 11;87(2-3):213–219. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90418-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King G. W. Brain stem blood vessels and the organization of the lateral reticular formation in the medulla oblongata of the cat. Brain Res. 1980 Jun 2;191(1):253–259. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90329-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumazawa T., Baccelli G., Guazzi M., Mancia G., Zanchetti A. Hemodynamic patterns during desynchronized sleep in intact cats and in cats with sinoaortic deafferentation. Circ Res. 1969 Jun;24(6):923–927. doi: 10.1161/01.res.24.6.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINDGREN P., ROSEN A., STRANDBERG P., UVNAS B. The sympathetic vasodilator outflow: a cortico-spinal autonomic pathway. J Comp Neurol. 1956 Aug;105(1):95–109. doi: 10.1002/cne.901050105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINDGREN P., UVNAS B. Activation of sympathetic vasodilator and vasoconstrictor neurons by electric stimulation in the medulla of the dog and cat. Circ Res. 1953 Nov;1(6):479–485. doi: 10.1161/01.res.1.6.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANNING J. W. CARDIOVASCULAR REFLEXES FOLLOWING LESIONS IN MEDULLARY RETICULAR FORMATION. Am J Physiol. 1965 Feb;208:283–288. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1965.208.2.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancia G., Baccelli G., Adams D. B., Zanchetti A. Vasomotor regulation during sleep in the cat. Am J Physiol. 1971 Apr;220(4):1086–1093. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1971.220.4.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllen R. M., Neil J. J., Loewy A. D. Effects of kainic acid applied to the ventral surface of the medulla oblongata on vasomotor tone, the baroreceptor reflex and hypothalamic autonomic responses. Brain Res. 1982 Apr 22;238(1):65–76. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90771-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millhorn D. E., Eldridge F. L., Waldrop T. G. Effects of medullary area I(s) cooling on respiratory response to chemoreceptor inputs. Respir Physiol. 1982 Jul;49(1):23–39. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(82)90101-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saper C. B., Loewy A. D., Swanson L. W., Cowan W. M. Direct hypothalamo-autonomic connections. Brain Res. 1976 Nov 26;117(2):305–312. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90738-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaefke M. E. Central chemosensitivity: a respiratory drive. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 1981;90:171–244. doi: 10.1007/BFb0034080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timms R. J. A study of the amygdaloid defence reaction showing the value of Althesin anaesthesia in studies of the functions of the fore-brain in cats. Pflugers Arch. 1981 Jul;391(1):49–56. doi: 10.1007/BF00580694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trouth C. O., Odek-Ogunde M., Holloway J. A. Morphological observations on superficial medullary CO2--chemosensitive areas. Brain Res. 1982 Aug 19;246(1):35–45. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90139-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wennergren G., Oberg B. Cardiovascular effects elicited from the ventral surface of medulla oblongata in the cat. Pflugers Arch. 1980 Sep;387(2):189–195. doi: 10.1007/BF00584271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werman R., Davidoff R. A., Aprison M. H. Inhibitory of glycine on spinal neurons in the cat. J Neurophysiol. 1968 Jan;31(1):81–95. doi: 10.1152/jn.1968.31.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]