Abstract

Morinda citrifolia L. (M. citrifolia), commonly referred to as noni, a Polynesian medicinal plant with over 2000 years of traditional use, has garnered global interest for its rich repertoire of antioxidant phytochemicals, including flavonoids (kaempferol, rutin), iridoids (aucubin, asperulosidic acid, deacetylasperulosidic acid, asperuloside), polysaccharides (nonioside A), and coumarins (scopoletin). This comprehensive review synthesizes recent advances (2018–2023) on noni’s bioactive constituents, pharmacological properties, and molecular mechanisms, with a focus on its antioxidant potential. Systematic analyses reveal that noni-derived compounds exhibit potent free radical scavenging capacity (e.g., 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl/2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonicacid) (DPPH/ABTS) inhibition), upregulate endogenous antioxidant enzymes (Superoxide Dismutase (SOD), Catalase (CAT), Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx)), and modulate key pathways such as Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2/Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Nrf2/Keap1) and Nuclear Factor kappa-B (NF-κB). Notably, polysaccharides and iridoids demonstrate dual antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects via gut microbiota regulation. This highlights the plant’s potential for innovation in the medical and pharmaceutical fields. However, it is also recognized that further research is needed to clarify its mechanisms of action and ensure its safety for widespread application. We emphasize the need for mechanistic studies to bridge traditional knowledge with modern applications, particularly in developing antioxidant-rich nutraceuticals and sustainable livestock feed additives. This review underscores noni’s role as a multi-target antioxidant agent and provides a roadmap for future research to optimize its health benefits.

Keywords: Morinda citrifolia L., antioxidant activity, oxidative stress, chemical composition, extraction method

1. Introduction

In the realm of natural resources, plants have long been a source of remarkable substances with diverse applications. Morinda citrifolia L. (M. citrifolia), well-known as noni, belongs to the Morinda genus, Rubiaceae family. The scientific plant names were provided by “the Plants of the World Online database” (POWO, https://powo.science.kew.org/ (accessed on 26 June 2024)) and “The World Flora Online” (https://www.worldfloraonline.org/ (accessed on 26 June 2024)). M. citrifolia is a green shrub or small tree naturalized in tropical climates, distributed along the southeast coast of China, Southeast Asia, Australia, the Pacific Ocean, and the Caribbean [1].

The fruit of M. citrifolia is a traditional Polynesian remedy frequently employed to alleviate symptoms of scabies, abscesses, constipation, diarrhea, and inflammation stemming from diverse etiologies [2]. The rhizome of M. citrifolia showcases medicinal properties that are quite similar to those of the traditional Chinese herb Morinda officinalis. Emerging evidence indicates that M. citrifolia possesses anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anticancer, and antibacterial properties [2,3,4,5,6]. Anthraquinones, flavonoids, coumarins, polysaccharides, and iridoids have been extracted from various parts of M. citrifolia, such as the fruits, roots, and stems exhibiting diverse pharmacological effects [7,8,9,10,11,12]. Juice products have been commercially available in the U.S. market since 1996. In modern medicine, M. citrifolia has been utilized to treat various conditions, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, inflammatory disorders, cancer, obesity, pain relief, and malaria [13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Multiple studies have shown that Morinda citrifolia has antioxidant activity at the same level as vitamin C [20].

The scientific exploration of Morinda citrifolia (noni) has garnered significant global research attention, as evidenced by bibliometric analyses. According to Web of Science data, China leads global research output with 129 peer-reviewed publications (as of July 2024); the United States has also provided 127 documents, contributing substantial empirical evidence on its phytochemistry and bioactivity. Emerging research economies, including India (66 publications), Brazil (57 publications), and Thailand (35 publications), have also made notable contributions, particularly in pharmacological validation and food science technology. This robust body of multinational research conclusively positions noni as a plant of exceptional therapeutic and agricultural promise, meriting prioritization as a species for multidisciplinary investigation—spanning ethnopharmacology, metabolic engineering, and sustainable cultivation strategies. The geographical diversity of research efforts underscores its adaptability to tropical ecosystems and its potential to address region-specific health and economic challenges.

In the context of livestock farming, oxidative stress is equally a major challenge. Challenges from environmental, technological, nutritional, and biological stressors lead to excessive production of reactive oxygen species in livestock, which in turn affects their growth, reproduction, and overall health. Exploring the antioxidant potential of natural products like noni in animal husbandry has become an emerging and promising area of research, given the growing demand for sustainable and healthy livestock production. With its proven antioxidant activity, noni may offer new solutions to enhance livestock health and performance by effectively reducing oxidative stress.

This literature review seeks to inform the development and utilization of noni fruit in livestock farming by consolidating existing knowledge on its nutritional and bioactive composition and therapeutic potential, facilitating further in-depth investigations into its mechanism of action. This paper reviews the botanical characterization, traditional uses, phytochemical constituents, compositional analyses, pharmacological properties, and safety studies to provide detailed insights into the biologically active compounds present in M. citrifolia based on research published between 2018 and 2023.

2. Methodological

This review comprehensively examines all published articles from the past five years about botanical characterization, traditional uses, phytochemical composition, pharmacological properties, and toxicological studies of M. citrifolia in PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 17 June 2024)), Science-Direct (https://www.sciencedirect.com/ (accessed on 18 June 2024)), and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) (https://www.cnki.net/ (accessed on 17 June 2024)). The search terms such as “Morinda citrifolia L.”, “Noni”, “Phytochemistry”, “Pharmacology”, and “safety” were employed, and articles were screened and evaluated for relevance based on their titles, abstracts, and keywords. With the application of preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Figure 1), a total of 147 articles were screened for this review. These articles come from various countries, with 68 articles of noni studied in China, 33 from the U.S., 30 from Brazil, 23 from India, 17 from Cuba, 17 from Indonesia, 16 from Malaysia, 16 from Thailand, and 10 from South Korea. They will be used to provide an in-depth analysis of the phytochemical composition, ethnomedicinal value, and phytopharmacological activity of M. citrifolia, offering a comprehensive overview of the current research landscape.

Figure 1.

Demonstrating the steps of choosing appropriate articles.

3. Botanical Features

M. citrifolia belongs to the Rubiaceae family, known as “Hai Ba Ji Tian” in China. M. citrifolia is native to Southeast Asia, widely distributed in the west to India and Sri Lanka, east to Polynesia, south to northern Australia, and north to Jiangsu, China. It is also distributed in the Caribbean, Mexico, and South America. China’s main producing areas are Yunnan, Hainan, and Taiwan. M. citrifolia is an evergreen tropical plant, fruiting throughout the year [21]. M. citrifolia is a perennial shrub or small arbor with a height of up to 1–5 m and straight stems and branches similar to the shape of a quadrangular column. It can adapt to harsh weather and soil conditions, even at altitudes up to 215 m [1]. M. citrifolia is widely distributed because of its light seeds and specialized structure, which enables it to spread by wind or water currents [22]. The global geographic distribution of M. citrifolia is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Global distribution of M. citrifolia (Source: https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:756359-1 (accessed on 20 June 2024)).

The fruit of M. citrifolia (noni) is a multiple fruit consisting of fused drupes, each containing four seeds, which develop between 9 months and 1 year after the tree is planted [23]. Noni is known as “nuna” in India [21], “mengkudu” in Malaysia [24], and “cheese fruit” in Australia [25]. Noni is oval in shape and consists of many small fruits clustered together, which measure approximately 5 to 10 cm in length and 3 to 6 cm in width. Each fruit may contain up to 260 seeds [1]. Initially, the fruits are green when young, and the skin is hard and rough in the early stage of maturity, turning white when ripe and finally turning yellowish–white and softening after ripening [21]. When the fruits are in the late stage of ripening, they have a rather unpleasant odor. The M. citrifolia bears fruit throughout the year, although the yield decreases in winter. The leaves of M. citrifolia are abundant and dark green in color, with rounded, spindly blades ranging from 8 to 25 cm in length [26]. Its flowers are white, tubular, smaller, clustered, and borne on peduncles.

4. Phytochemistry

The diverse chemical composition of medicinal plants is the key to their pharmacological activity. Studies on the phytochemistry of M. citrifolia have focused on the roots, leaves, and fruits, with anthraquinones, iridoids, flavonoids, and coumarins as the main compounds; among these, damnacanthal, scopoletin, rutin, ursolic acid, and asperuloside are the main components of M. citrifolia [26,27,28]. The compounds isolated from the roots are dominated by anthraquinone compounds [29] (e.g., damnacanthal [12] and sterols [30]). The M. citrifolia leaves contain a variety of iridoids, flavonoids, and triterpenoids [9,31,32,33]. Noni juice as a dietary supplement is the reason why more focus has been placed on the compositional analysis of the fruit, including phenols, polysaccharides, coumarins, fatty acids, cyclic enol ether terpenes, flavonoids, carotenoids, essential oils, and more [10,11,34], and the composition of vitamins, amino acids, and trace minerals has also been reported [1]. Table 1 summarizes the information on the chemical composition of M. citrifolia from different studies.

Table 1.

Compounds isolated from M. citrifolia.

| Class | No. | Compounds | Molecular Formula | Parts | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aminoacids | 1 | Alanine | C3H7NO2 | Fruits | [35] |

| 2 | Arginine | C6H14N4O2 | Fruits | ||

| 3 | Aspartic acid | C4H7NO4 | Fruits | ||

| 4 | Cysteine | C3H7NO2S | Fruits | ||

| 5 | Glutamic acid | C5H9NO4 | Fruits | ||

| 6 | Glycine | C2H5NO2 | Fruits | ||

| 7 | Histidine | C6H9N3O2 | Fruits | ||

| 8 | Isoleucine | C6H13NO2 | Fruits | ||

| 9 | Leucine | C6H13NO2 | Fruits | ||

| 10 | Lysine | C6H14N2O2 | Fruits | ||

| 11 | Methionine | C5H11NO2S | Fruits | ||

| 12 | Phenylalanine | C9H11NO2 | Fruits | ||

| 13 | Proline | C5H9NO2 | Fruits | ||

| 14 | Serine | C3H7NO3 | Fruits | ||

| 15 | Threonine | C4H9NO3 | Fruits | ||

| 16 | Tryptophan | C11H12N2O2 | Fruits | ||

| 17 | Tyrosine | C9H11NO3 | Fruits | ||

| 18 | Valine | C9H11NO2 | Fruits | ||

| Anthraquinones | 19 | 1,2-Dihydroxy-3-methoxy-anthraquinone | C15H10O5 | Roots | [1] |

| 21 | 1,3,6-Trihydroxy-2-methylanthraquinone | C15H10O4 | Roots | [36] | |

| 22 | 1,3-Dihydroxy-2-methoxy-anthraquinone | C15H10O5 | Roots | [37] | |

| 23 | 1,3-Dihydroxy-5-methoxy-2,6-bismethoxymethyl-9,10-anthraquinone | C19H18O7 | Barks | [38] | |

| 24 | 1,3-Dihydroxy-5-methoxy-6-methoxymethyl-2-methyl-9,10-anthraquinone | C18H16O6 | Barks | ||

| 25 | 1,3-Dimethoxy-2-methoxymethylanthraquinone | C18H16O5 | Roots | [29] | |

| 26 | 1,3-Dimethoxyanthraquinone | C16H12O4 | Fruits | [39] | |

| 27 | 1,4-Dimethoxyl-2-hydroxyanthraquinone | C16H12O5 | Barks | [38] | |

| 28 | 1,5,15-Trimethylmorindol | C18H16O6 | Barks, Fruits, Leaves | ||

| 30 | 1,5,7-Trihydroxy-6-methoxy-2-methoxymethylanthraquinone | C17H14O7 | Fruits | [8] | |

| 31 | 1,8-Dihydroxy-2-hydroxymethyl-5-methoxyanthraquinone | C16H12O6 | Fruits | [28] | |

| 32 | 1,8-Dihydroxy-2-methyl-3,7-dimethoxyanthraquinone | C17H14O6 | Plants | [40] | |

| 33 | 1-Hydroxy-2-methyl-9,10-anthraquinone | C15H10O3 | Roots, Fruits | [1,37] | |

| 35 | 1-Hydroxy-2-methylol-anthraquinone | C15H10O3 | Roots | [39] | |

| 36 | 1-Hydroxy-2-primeverosyloxymethyl-anthraquinone-3-olate | C26H27O14 | Roots | [41] | |

| 37 | 1-Hydroxy-5,6-dimethoxy-2-methyl-7-primeverosyloxyanthraquinone | C28H32O15 | Roots | ||

| 38 | 1-Hydroxy-5-methoxyanthraquinone | C15H10O4 | Barks | [38] | |

| 39 | 1-Methoxy-2′,2′-dimethyldioxine-(5,6′:2,3)-anthraquinone | N/A | Roots | [1] | |

| 40 | 1-Methoxy-2-primeverosyloxymethyl-anthraquinone-3-olate | C27H29O14 | Roots | [41] | |

| 41 | 1-Methoxy-3-hydroxyanthraquinone | C15H10O4 | Roots | [39] | |

| 42 | 1-Methyl-3-hydroxy-anthraquinone | C15H10O3 | Roots | ||

| 43 | 1-O-gentiobiose-2-methylol-anthraquinone | C27H30O14 | Roots | [37] | |

| 44 | 1-O-gentiobiose-3-hydroxy-2-methyl-anthraquinone | C27H30O13 | Roots | ||

| 45 | 1-O-gentiobiose-8-methoxy-aloeemodin | C28H32O15 | Roots | ||

| 46 | 1-O-gentiobiose-emodin | C27H30O15 | Roots | ||

| 47 | 1-O-primeverose-2-methyl-3,6,8-trihydroxy-anthraquinone | C26H28O15 | Roots | ||

| 48 | 1-O-primeverose-2-methylol-3-hydroxy-8-methoxy-anthraquinone | C27H30O14 | Roots | ||

| 49 | 1-O-primeverose-2-methylol-anthraquinone | C26H28O13 | Roots | ||

| 50 | 1-O-primeverose-3,8-dihydroxy-2-methyl-anthraquinone | C26H28O14 | Roots | ||

| 51 | 1-O-primeverose-3,8-dimethoxy-2-methyl-anthraquinone | C28H32O14 | Roots | ||

| 52 | 1-O-primeverose-3-methoxy-8-hydroxy-2-methylol-anthraquinone | C27H30O15 | Roots | ||

| 53 | 1-O-primeverose-8-hydroxy-ibericin | C28H32O15 | Roots | ||

| 54 | 1-O-primeverose-aloeemodin | C26H28O14 | Roots | ||

| 55 | 1-O-primeverose-emodin | C26H28O14 | Roots | ||

| 56 | 1-O-primeverose-rubiadin | C26H28O13 | Roots | ||

| 57 | 1-O-β-D-glycopyranosyl-8-methoxy-emodin | C22H22O10 | Roots | ||

| 58 | 1-O-β-D-glycopyranosyl-emodin | C21H20O10 | Roots | ||

| 59 | 1-O-β-D-glycopyranosylrubiadin-3-methyl ether | C22H22O9 | Roots | ||

| 60 | 2-Ethoxy-1-hydroxyanthraquinone | C16H12O9 | Roots | [39] | |

| 61 | 2-Formyl-1-hydroxyanthraquinone | C15H8O4 | Roots | ||

| 62 | 2-Formylanthraquinone | C15H8O3 | Roots | ||

| 63 | 2-Methoxy-1,3,6-trihydroxyanthraquinone | C15H10O6 | Roots | [28] | |

| 64 | 2-Methoxy-3-methyl-anthraquinone | C16H12O3 | Roots | [38] | |

| 65 | 2-Methyl-4-hydroxy-5,7-dimethoxyanthraquinon | N/A | Flowers | [14] | |

| 66 | 3-Hydroxy-2-hydroxymethyl- anthraquinone | N/A | Roots | [39] | |

| 67 | 3-O-gentiobiose-1-hydroxy-2-methyl-anthraquinone | C27H30O14 | Roots | [37] | |

| 68 | 3-O-primeverose-1,6,8-trihydroxy-2-methyl-anthraquinone | C26H28O15 | Roots | ||

| 69 | 5,15-Di-O-methylmorindol | C17H14O6 | Fruits | [39] | |

| 70 | 6-Hydroxy-anthragallol-1,3-dimethylether | C16H12O6 | Fruits | ||

| 71 | 8-O-gentiobiose-emodin | C27H30O15 | Roots | [37] | |

| 72 | Alizarin | C14H8O4 | Fruits, Roots | [42] | |

| 73 | Alizarin-1-methyl ether | C15H10O4 | Fruits, Roots | [39] | |

| 74 | Aloe-emodin | C15H10O5 | Roots | [37] | |

| 75 | Anthragallol-2-methyl ether | C15H10O5 | Fruits | [39] | |

| 76 | Damnacanthal | C16H10O5 | Leaves, Roots | [29,42] | |

| 77 | Damnacanthol-11-O-β-primeveroside | N/A | Roots | [41] | |

| 78 | Damnacanthol-3-O-β-D-primeveroside | N/A | Roots | [43] | |

| 79 | Damnacanthol-ω-ethyl ether | N/A | Roots | [44] | |

| 80 | Degiferruginol-11-O-β-Primeveroside | N/A | Roots | [41] | |

| 81 | Digiferruginol-1-Methylether-11-O-β-gentiobioside | N/A | Roots | ||

| 82 | Emodin | C15H10O5 | Roots | [37] | |

| 83 | Emodin 1-O-β-D-glycopyranosyl | C21H20O10 | Roots | ||

| 84 | Fridamycin E | C19H16O7 | Roots | ||

| 85 | Ibericin | C17H14O5 | Roots | [29] | |

| 86 | Lucidin | C15H10O5 | Fruits | [1] | |

| 87 | Lucidin 1,3-dimethyl ether | N/A | Barks | [38] | |

| 88 | Lucidin 3-methyl ether | C16H11O5 | Barks | ||

| 89 | Lucidin-3-O-β-D-Primeveroside | N/A | Roots | [43] | |

| 90 | Lucidin-ω-butyl ether | N/A | Roots | [44] | |

| 91 | Morindadiol | N/A | Fruits | [45] | |

| 92 | Morindicininone | C17H14O5 | Stems | [39] | |

| 93 | Morindicinone | C18H16O6 | Stems | ||

| 94 | Morindone | C15H10O5 | Fruits | ||

| 95 | Morindone-5-methylether | C16H12O5 | Fruits | ||

| 96 | Morindone-6-methyl-ether | C16H12O5 | Barks, Roots | [12] | |

| 97 | Morindone-6-O-β-D-primeveroside | N/A | Roots | [43] | |

| 98 | Nordamnacanthal | C15H8O5 | Stem, Fruits | [46] | |

| 99 | Rubiadin | C15H10O4 | Roots | [29] | |

| 100 | Rubiadin-1-methyl ether | C16H12O4 | Fruits, Roots | [37,40] | |

| 101 | Rubiadin-3-methyl ether | C16H12O4 | N/A | [1] | |

| 102 | Rubiadin-dimethyl ether | C17H14O4 | N/A | ||

| 103 | Tectoquinone | C15H10O2 | Roots | ||

| Anthrone | 104 | 1,8-Dihydroxy-6-methoxy-3-methyl-9-anthrone | N/A | Fruits | [47] |

| 105 | 2,4-Dimethoxy-9-anthrone | N/A | Fruits | ||

| Carotenoids | 106 | β-Carotene | C40H56 | Leaves, Fruit | [48] |

| Coumarins | 107 | Esculetin | C9H6O4 | Fruits | [14] |

| 108 | Fraxidin | C11H10O5 | Barks | [38] | |

| 109 | Isofraxidin | C11H10O5 | Barks | ||

| 110 | Isoscopoletin | C10H8O4 | Fruits | [14] | |

| 111 | Peucedanocoumarin III | C21H22O7 | Fruits | ||

| 112 | Pteryxin | C21H22O7 | Fruits | ||

| 113 | Scopoletin | C10H8O4 | Leaves, Fruit | [35] | |

| Fatty acids | 114 | Caproic acid | C6H12O2 | Fruits | [14] |

| 115 | Caprylic acid | C8H16O2 | Fruits | [45] | |

| 116 | Eicosanoic acid | C20H40O2 | Fruits | [49] | |

| 117 | Hexanoic acid | N/A | Fruits | [45] | |

| 118 | Lauric acid | C12H24O2 | Seeds | [49] | |

| 119 | Linoleic acid | C18H32O2 | Seeds | ||

| 120 | Methyl octanoate | C9H18O2 | Fruits | [45] | |

| 121 | Octanoic | C8H16O2 | Fruits | ||

| 122 | Oleic acid | C18H34O2 | Seeds | [49] | |

| 123 | Palmitoleic acid | C16H30O2 | Seeds | ||

| 124 | Stearic acid | C18H36O2 | Seeds | ||

| Flavonoids | 125 | 5,8-Dimethyl-apigenin 4′-O-β-D-galacatopyranoside | N/A | Flowers | [14] |

| 126 | Acacetin-7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | N/A | Fruits, Flowers | ||

| 127 | Anthocyanin | C27H31O16 | Fruits | [15] | |

| 128 | Apigenin-5,7-dimethyl-4′-O-β-galactopyranoside | N/A | Fruits | [14] | |

| 129 | Catechin | C15H14O6 | Fruits | [50] | |

| 130 | Epicatechin | C15H11O6 | Fruits | [51] | |

| 131 | Kaempferol | C15H10O6 | Leaves, Fruits | [31] | |

| 132 | Kaempferol-3-O-α-l-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-D-glucopyranoside | N/A | Leaves, Fruits | ||

| 133 | Narcissoside | C28H32O16 | Fruits | [30] | |

| 134 | Nicotifloroside | C27H30O15 | Fruits | ||

| 135 | Quercetin | C15H10O7 | Fruits | [35] | |

| 136 | Quercetin-3-O-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-D-glucopyranoside | N/A | Leaves, Flowers | [14,52] | |

| 137 | Quercetin-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | C21H20O12 | Fruits | [52] | |

| 138 | Rutin | C27H30O16 | Fruits, Leaves | [35] | |

| Glycosides | 139 | (2E,4E,7Z)-Deca-2,4,7-trienoate-2-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-β-D-glucopyra-noside | C22H34O13 | Fruits | [53] |

| 140 | 3-Methylbut-3-enyl 6-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-β-D-glucopyranoside | C17H30O11 | Fruits | [54] | |

| 141 | 6-O-(β-D-glucopyranosyl)-1-O-octanoyl-β-D-glucopyranose | C20H36O12 | Fruits | ||

| 142 | 6-O-(β-D-glucopyranosyl)-1-O-hexanoyl-β-D-glucopyranose | C18H32O12 | Fruits | ||

| 143 | Amyl-1-O-β-D-apio-furanosyl-1,6-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | C16H30O10 | Fruits | [53] | |

| Iridoids | 144 | 6α-Hydroxyadoxoside | N/A | Fruits | [30] |

| 145 | 6β,7β-Epoxy-8-epi-splendoside | N/A | Fruits | ||

| 146 | 9-epi-6α-Methoxy geniposidic acid | N/A | Fruits | [55] | |

| 147 | Asperuloside | C18H22O11 | Fruits, Roots | [37] | |

| 148 | Asperulosidic acid | C18H24O12 | Fruits, Roots | [35] | |

| 149 | Asperulosidic acid methyl ester | N/A | Fruits, Leaves | [52] | |

| 150 | Aucubin | C15H22O9 | Fruits | [1] | |

| 151 | Borreriagenin | C10H14O5 | Fruits | [30] | |

| 152 | Citrifolinin B | N/A | Leaves | [56] | |

| 153 | Citrifolinoside A | C26H28O14 | Leaves | [57] | |

| 154 | Citrifoside | N/A | Leaves | [32] | |

| 155 | Deacetyl asperulosidic acid | C16H22O11 | Fruits | [35] | |

| 156 | Deacetylasperuloside | N/A | Fruits, Leaves | [52] | |

| 157 | Dehydromethoxygaertneroside | N/A | Fruits | [30] | |

| 158 | Diacetylasperulosidic acid | C16H22O11 | Roots | [37] | |

| 159 | epi-Dihydrocornin | N/A | Fruits | [30] | |

| 160 | Geniposidic acid | C16H22O10 | Roots | [37] | |

| 161 | Harpagide acetate | C17H26O11 | Roots | ||

| 162 | Isoasperulosidic acid | C18H24O12 | Roots | ||

| 163 | Loganic acid | C16H24O10 | Seeds | [58] | |

| 164 | Monotropein | C16H22O11 | Roots | [37] | |

| 165 | Morindacin | C10H14O5 | Fruits | [59] | |

| 166 | Rehmannioside A | C21H32O15 | Roots | [37] | |

| 167 | Rhodolatouside | N/A | Seeds | ||

| 168 | Scandoside methyl ester | C17H24O11 | Fruits | [55] | |

| 169 | Ursolic Acid | C30H48O3 | Fruits | [60] | |

| Lactone | 170 | 3,4,3′,4′-Tetrahydroxy-9,7′α-epoxylignano-7α,9′-lactone | C18H16O7 | Fruits | |

| Lignans | 171 | (-)-3,3′-Bisdemethylpinoresinol | C18H18O6 | Fruits | |

| 172 | (7R,8R)-3,4,9-Trihydroxy-4′,7-epoxy-8,3′-oxyneolignan-1′-al | C16H14O6 | Fruits | ||

| 173 | (7R,8R)-3-Methoxy-1′-carboxy-4′,7-epoxy-8,3′-oxyneolignan-4,9-diol | C17H16O7 | Fruits | ||

| 174 | Americanin A | C18H16O6 | Fruits | [30] | |

| 175 | Episesamin 2,6-dicatechol | N/A | Fruits | [60] | |

| 176 | Isoprincepin | C27H26O9 | Fruits | [61] | |

| 177 | Lirioresinol B | N/A | Fruits | [60] | |

| 178 | Morindolin | N/A | Fruits | [61] | |

| 179 | Pinoresinol | C20H22O6 | Fruits | [60] | |

| 180 | trans-(3)E-3-(3,4-dihydroxybenzylidene)-5-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-4-(hydroxymethyl) dihydrofuran-2(3H)-one | C18H16O7 | Fruits | [60] | |

| 181 | β-Hydroxypropiovanillone | N/A | Fruits | [14] | |

| Minerals | 182 | Calcium | N/A | Leaves, Fruits | [62] |

| 183 | Cobalt | N/A | Fruits | [1] | |

| 184 | Copper | N/A | Fruits | [62] | |

| 185 | Iron | N/A | Fruits | ||

| 186 | Magnesium | N/A | Fruits | ||

| 187 | Molybdenum | N/A | Fruits | [1] | |

| 188 | Phosphor | N/A | Fruits | [62] | |

| 189 | Potassium | N/A | Fruits | [63] | |

| 190 | Selenium | N/A | Fruits | [1] | |

| 191 | Sodium | N/A | Fruits | ||

| 192 | Zinc | N/A | Fruits | ||

| Nucleoside | 193 | Cytidine | C9H13N3O5 | Leaves | [52] |

| Phenolic acid | 194 | Chlorogenic acid | C16H18O9 | Fruits | [64] |

| 195 | Gentisic acid | C7H6O4 | Fruits | ||

| 196 | p-Hydroxybenzoic acid | C7H6O3 | Fruits | ||

| Phenylpropanoids | 197 | Butyl 3-(2,4-dihydroxy-5-methoxyphenyl) propionate | C14H20O5 | Fruits | [65] |

| 198 | Methyl 3-(2,4-dihydroxy-5-methoxyphenyl) propionate | C11H14O5 | Fruits | ||

| Saccharides | 199 | D-Glucose | C6H12O6 | Fruits | [30] |

| 200 | Methyl β-D-fructofuranoside | C7H14O6 | Fruits | ||

| 201 | Methyl α-D-fructofuranoside | C7H13O6 | Fruits | [1] | |

| 202 | Nonioside A | C17H30O11 | Fruits | ||

| 203 | Nonioside B | C26H46O17 | Fruits | ||

| 204 | Nonioside C | C20H36O12 | Fruits | ||

| 205 | Nonioside D | C18H32O12 | Fruits | ||

| 206 | Noniosides E | C24H42O17 | Fruits | [66] | |

| 207 | Noniosides F | C28H50O17 | Fruits | ||

| 208 | Noniosides G | C34H60O18 | Fruits | ||

| 209 | Noniosides H | C32H56O18 | Fruits | ||

| Sterols | 210 | β-sitosterol 3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | C35H60O6 | Fruits | [30] |

| 211 | Stigmasterol | C29H48O | Leaves | [67] | |

| Vitamins | 212 | Ascorbic acid (C) | C6H8O6 | Fruits | [14] |

| 213 | Biotin (B7) | C10H16N2O3S | Fruits | [1] | |

| 214 | Cobalamin (B12) | C63H88CoN14O14P | Fruits | ||

| 215 | Folic Acid (B9) | C19H19N7O6 | Fruits | ||

| 216 | Niacin (B3) | C6H5NO2 | Fruits | ||

| 217 | Pantothenic Acid (B5) | C9H17NO5 | Fruits | ||

| 218 | Pyridoxine (B6) | C8H11NO3 | Fruits | ||

| 219 | Riboflavin (B2) | C17H20N4O6 | Fruits | ||

| 220 | Thiamine (B1) | C12H17N4OS | Fruits | ||

| 221 | Tocopherol (E) | C29H50O2 | Fruits | ||

| 222 | Vitamin K | C31H46O2 | Fruits | ||

| Others | 223 | 2,6-Di-O-(β-D-glucopyranosyl)-1-O-octanoy-1-β-D-glucopyranose | N/A | N/A | [14] |

| 224 | 4-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→4)-α-L-rhamnopyranoside | N/A | Flowers | ||

| 225 | Morinaphthalene | N/A | Fruits | [47] | |

| 226 | Morinaphthalenone | N/A | Fruits | ||

| 227 | Morindafurone | N/A | Fruits | ||

| 228 | Morinthone | C31H44O3 | Fruits | [14] | |

| 229 | β-D-glucopyranose-penta-acetate | N/A | Fruits |

Notes: N/A, data not available.

4.1. Iridoids

Iridoids are a fascinating group of compounds that can be found in many different types of plants and insects, such as the Aspidistra, Gentianae, Lamiaceae, Lauraceae, Rubiaceae, Sedum, and Verbenaceae families, as well as in insects, including butterflies [68]. Iridoids are a subclass of monoterpenoids and are acetal derivatives of iridodial. Natural iridoids possess the basic skeleton of a cyclopentadiene-fused pyran ring. Iridoids can be divided into iridoid glycosides, secoiridoids glycosides, bis-iridoids, and non-glycosidic iridoids. Iridoids have been shown to have many different biological activities, including anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antiviral, neuroprotective, hepatoprotective, hypoglycemic, antitumor, and antioxidant activities [69,70].

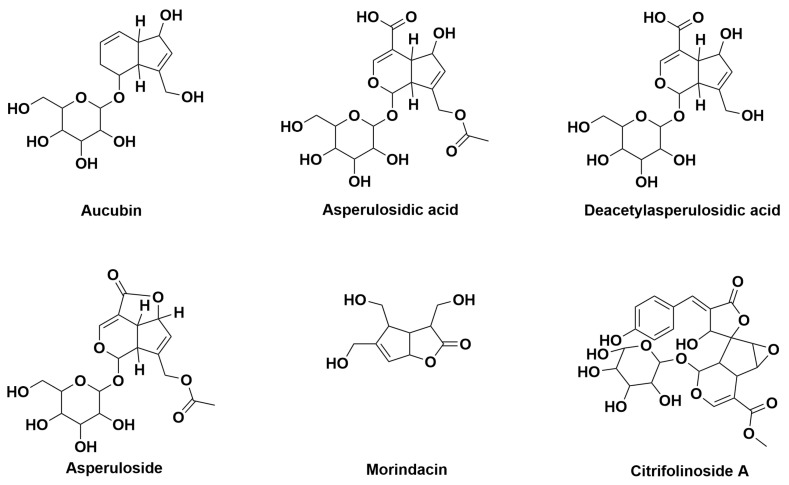

Figure 3 shows the six main types of iridoids contained in M. citrifolia: aucubin, asperulosidic acid, deacetylasperulosidic acid, asperuloside, morindacin, citrifolinoside A.

Figure 3.

Structures of iridoids from M. citrifolia.

4.2. Anthraquinones

Anthraquinones are a class of chemical compounds that consist of three benzene rings fused together in a specific arrangement. They are widely found in nature and can be found in various plants such as Polygonum and Rubiaceae, particularly in the rhizomes and bark of plants, as well as in certain fungi [71]. In M. citrifolia, anthraquinones are one of its primary bioactive substances [72]. They are primarily present in the roots of M. citrifolia.

The presence of hydroxyl groups on the anthraquinone ring is associated with a range of biological activities, including anti-tumor, antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-osteoporosis effects. The polarity of the substituent groups on the anthraquinone ring is directly related to its antimicrobial activity; generally, the stronger the polarity of the substituent, the more effective the antimicrobial ability. However, the substitution of sugar chains on anthraquinones tends to reduce their antioxidant activity [73].

The most significant anthraquinone found in M. citrifolia is damnacanthal. Its ability to target various tyrosine kinases shows promising anti-cancer activity [74]. Other anthraquinones isolated from M. citrifolia include alizarin, morindadiol, nordamnacanthal, rubiadin, ibericin, tectoquinone, lucidin, damnacanthol-ω-ethyl ether, lucidin-ω-butyl ether, rubiadin-dimethyl ether, rubiadin-1-methyl ether, rubiadin-3-methyl ether, and 1-hydroxy-2-methyl-9,10-anthraquinone. For more information on the detailed chemical structure formula of these compounds, please refer to Figure 4 and Table 2.

Figure 4.

Structures of anthraquinones from M. citrifolia.

Table 2.

Anthraquinones isolated from M. citrifolia.

| Anthraquinones | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 | R7 | R8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,2-Dihydroxy-3-methoxy-anthraquinone | OH | OH | OCH3 | H | H | H | H | H |

| 1,3,6-Trihydroxy-2-methylanthraquinone | OH | CH3 | OH | H | H | OH | H | H |

| 1,3-Dihydroxy-2-methoxy-anthraquinone | OH | OCH3 | OH | H | H | H | H | H |

| 1,3-Dihydroxy-5-methoxy-2,6-bismethoxymethyl-9,10-anthraquinone | OH | CH2OCH3 | OH | H | OCH3 | CH2OCH3 | H | H |

| 1,3-Dihydroxy-5-methoxy-6-methoxymethyl-2-methyl-9,10-anthraquinone | OH | CH3 | OH | H | OCH3 | CH2OCH3 | H | H |

| 1,3-Dimethoxy-2-methoxymethylanthraquinone | OCH3 | CH2OCH3 | OCH3 | H | H | H | H | H |

| 1,3-Dimethoxyanthraquinone | OCH3 | H | OCH3 | H | H | H | H | H |

| 1,4-Dimethoxyl-2-hydroxyanthraquinone | OCH3 | OH | H | OCH3 | H | H | H | H |

| 1,5,15-Trimethylmorindol | OCH3 | CH2OCH3 | H | H | OCH3 | OH | H | H |

| 1,5,7-Trihydroxy-6-methoxy-2-methoxymethylanthraquinone | OH | OCH3 | OH | H | OH | CH2OCH3 | H | H |

| 1,8-Dihydroxy-2-hydroxymethyl-5-methoxyanthraquinone | OH | CH2OH | H | H | OCH3 | H | H | OH |

| 1,8-Dihydroxy-2-methyl-3,7-dimethoxyanthraquinone | OH | CH3 | OCH3 | H | H | H | OCH3 | OH |

| 1-Hydroxy-2-methyl-9,10-anthraquinone | OH | CH3 | H | H | H | H | H | H |

| 1-Hydroxy-2-primeverosyloxymethyl-anthraquinone-3-olate | OH | CH2O-prime | O | H | H | H | H | H |

| 1-Hydroxy-5,6-dimethoxy-2-methyl-7-primeverosyloxyanthraquinone | OH | CH3 | H | H | OCH3 | OCH3 | O-prime | H |

| 1-Hydroxy-5-methoxyanthraquinone | OCH3 | H | H | H | OH | H | H | H |

| 1-Methoxy-2-primeverosyloxymethyl-anthraquinone-3-olate | OCH3 | CH2O-prime | O | H | H | H | H | H |

| 1-Methoxy-3-hydroxyanthraquinone | OCH3 | H | OH | H | H | H | H | H |

| 1-Methyl-3-hydroxy-anthraquinone | CH3 | H | OH | H | H | H | H | H |

| 1-O-gentiobiose-2-methylol-anthraquinone | O-gent | CH2OH | H | H | H | H | H | H |

| 1-O-gentiobiose-3-hydroxy-2-methyl-anthraquinone | O-gent | CH3 | OH | H | H | H | H | H |

| 1-O-gentiobiose-8-methoxy-aloeemodin | O-gent | H | CH2OH | H | H | H | H | OCH3 |

| 1-O-gentiobiose-emodin | O-gent | H | CH3 | H | H | OH | H | OH |

| 1-O-primeverose-2-methyl-3,6,8-trihydroxy-anthraquinone | O-prime | CH3 | OH | H | H | OH | H | OH |

| 1-O-primeverose-2-methylol-3-hydroxy-8-methoxy-anthraquinone | O-prime | CH2OH | OH | H | H | H | H | OCH3 |

| 1-O-primeverose-2-methylol-anthraquinone | O-prime | CH2OH | H | H | H | H | H | H |

| 1-O-primeverose-3,8-dihydroxy-2-methyl-anthraquinone | O-prime | CH3 | OH | H | H | H | H | OH |

| 1-O-primeverose-3,8-dimethoxy-2-methyl-anthraquinone | O-prime | CH3 | OH | H | H | H | H | OCH3 |

| 1-O-primeverose-3-methoxy-8-hydroxy-2-methylol-anthraquinone | O-prime | CH2OH | OCH3 | H | H | H | H | OH |

| 1-O-primeverose-8-hydroxy-ibericin | O-prime | CH2OCH2CH3 | OH | H | H | H | H | OH |

| 1-O-primeverose-aloeemodin | O-prime | H | CH2OH | H | H | H | H | OH |

| 1-O-primeverose-emodin | O-prime | H | CH3 | H | H | OH | H | OH |

| 1-O-primeverose-rubiadin | O-prime | CH3 | OH | H | H | H | H | H |

| 1-O-β-D-glycopyranosyl-8-methoxy-emodin | O-glu | H | CH2OH | H | H | OH | H | OCH3 |

| 1-O-β-D-glycopyranosyl-emodin | O-glu | H | CH3 | H | H | OH | H | OH |

| 1-O-β-D-glycopyranosylrubiadin-3-methyl ether | O-glu | CH3 | OCH3 | H | H | H | H | H |

| 2-Ethoxy-1-hydroxyanthraquinone | OH | OCH2CH3 | H | H | H | H | H | H |

| 2-Formyl-1-hydroxyanthraquinone | OH | CHO | H | H | H | H | H | H |

| 2-Formylanthraquinone | H | CHO | H | H | H | H | H | H |

| 2-Methoxy-1,3,6-trihydroxyanthraquinone | OH | OCH3 | OH | H | H | OH | H | H |

| 2-Methoxy-3-methyl-anthraquinone | H | OCH3 | CH3 | H | H | H | H | H |

| 3-O-gentiobiose-1-hydroxy-2-methyl-anthraquinone | OH | CH3 | O-gent | H | H | H | H | H |

| 3-O-primeverose-1,6,8-trihydroxy-2-methyl-anthraquinone | OH | CH3 | O-prime | H | H | OH | H | OH |

| 5,15-Di-O-methylmorindol | OH | CH2OCH3 | H | H | OCH3 | OH | H | H |

| 6-Hydroxy-anthragallol-1,3-dimethylether | OCH3 | OH | OCH3 | H | H | OH | H | H |

| 8-O-gentiobiose-emodin | OH | H | CH3 | H | H | OH | H | O-gent |

| Alizarin | OH | OH | H | H | H | H | H | H |

| Alizarin-1-methyl ether | OCH3 | OH | H | H | H | H | H | H |

| Aloe-emodin | OH | H | CH2OH | H | H | H | H | OH |

| Anthragallol-2-methyl ether | OH | OCH3 | OH | H | H | H | H | H |

| Damnacanthal | OCH3 | CHO | OH | H | H | H | H | H |

| Emodin | OH | H | OH | H | H | CH3 | H | OH |

| Emodin 1-O-β-D-glycopyranosyl | OH | H | CH3 | H | H | OH | H | O-glu |

| Fridamycin E | OH | CH2COH(CH3)CH2COOH | H | H | OH | H | H | H |

| Ibericin | OH | CH2OCH2CH3 | OH | H | H | H | H | H |

| Lucidin | OH | CH2OH | OH | H | H | H | H | H |

| Lucidin 3-methyl ether | OH | CH2OH | OCH3 | H | H | H | H | H |

| Morindicininone | OCH3 | H | OCH3 | CH2OH | H | H | H | H |

| Morindicinone | OCH3 | OH | H | H | H | H | CH2OCH3 | OCH3 |

| Morindone | OH | OH | H | H | OH | CH3 | H | H |

| Morindone-5-methylether | OH | CH3 | H | H | OCH3 | OH | H | H |

| Morindone-6-methyl-ether | OH | CH3 | H | H | OH | OCH3 | H | H |

| Morindone-6-O-β-D-primeveroside | OH | CH3 | H | H | OH | O-prime | H | H |

| Nordamnacanthal | OH | CHO | OH | H | H | H | H | H |

| Rubiadin | OH | CH3 | OH | H | H | H | H | H |

| Rubiadin-1-methyl ether | OCH3 | CH3 | OH | H | H | H | H | H |

| Rubiadin-3-methyl ether | OH | CH3 | OCH3 | H | H | H | H | H |

| Rubiadin-dimethyl ether | OCH3 | CH3 | OCH3 | H | H | H | H | H |

| Tectoquinone | H | CH3 | H | H | H | H | H | H |

4.3. Coumarins

Coumarins possess a unique bicyclic structure consisting of a benzene ring and a pyran ring. Variations in the substituents on the bicyclic ring contribute to a diverse range of biological properties and activities, including antioxidant, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory effects. Coumarins are commonly found in plants from the Leguminosae, Rosaceae, and Cuscuta families [75]. For instance, scopoletin is the primary coumarin present in M. citrifolia, and there is 6 mg/g in the water extract of its leaves [76]. The structural formula of scopoletin is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Structures of scopoletin from M. citrifolia.

4.4. Flavonoids

Flavonoids are plant-specific secondary metabolites, which are small-molecule natural products with a variety of pharmacological effects such as anticancer, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and reducing vascular fragility. The basic structure of flavonoids is two aromatic rings and a three-carbon bridge connected to a diphenylpropane structure with phenolic or polyphenolic groups in various positions. Assessing the quality of noni extract involves considering its total flavonoid content [14], which is typically measured using rutin standards for assays [77]. Interestingly, the flavonoid content of noni extract can vary slightly depending on the ripeness of the fruit, with a consistent upward trend observed as noni ripens. In a study by Zhang [78] and Chen [77], the total flavonoid content of noni juice and noni fruits was found to be 234.42 mg/L and 12.56–14.48 g/kg.

The following flavonoid compounds are found in M. citrifolia (Figure 6): acacetin-7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, kaempferol, rutin, narcissoside, quercetin, quercetin-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, quercetin-3-O-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-D-glucopyranoside, and 5,7-dumethyl-apigenin-4′-O-β-D-galactopyranoside.

Figure 6.

Structures of flavonoids from M. citrifolia.

4.5. Polysaccharide

Polysaccharides are molecules containing more than ten monosaccharides connected by glycosidic bond polymerization and are important biomolecules in nature. They have biological activities such as immunomodulation, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor, and hypoglycemic activity. Various types of noni extracts have been researched and found to have good anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties because of polysaccharides. Extraction of noni polysaccharides is usually done by extracting the juice or puree with distilled water, centrifugation of the extract, and precipitation with alcohol [20,79,80,81,82]. The crude polysaccharide content in noni fruit decreases significantly as it matures, from 1.72 g/100 g to 1.07 g/100 g. Research suggests that enzymes in noni break down the polysaccharides in the cell wall, resulting in a gradual decrease in polysaccharide content as the fruit softens. Figure 7 shows the structure of polysaccharides isolated from M. citrifolia fruits.

Figure 7.

Structures of polysaccharide from M. citrifolia.

4.6. Nutrients

Minerals account for approximately 8.4% of the dry matter of noni fruit and can vary depending on the fruit’s maturity. West et al. [35] found that potassium is the most abundant mineral in noni puree, with a content of approximately 214.34 mg/100 g. In addition, other minerals such as calcium, iron, sodium, and selenium have also been detected. Vitamins have been identified in studies related to noni fruit as well. Noni fruit has the highest content of vitamin C, ranging from 24 to 158 mg per 100 g of dry matter [21]. The vitamin C content in noni puree is approximately 1.13 mg/g.

5. Extraction Method for M. citrifolia

In order to explore the phytochemistry of M. citrifolia and conduct pharmacological research, numerous methods have been employed to extract the various compounds present in M. citrifolia. These techniques encompass Soxhlet extraction [83], ultrasound-assisted extraction [84], solid-phase microextraction [11], cold-soak extraction [85], subcritical water extraction [86], and microwave-assisted extraction [87]. The choice of solvent plays a pivotal role in the extraction of phytochemicals. The polarity of the solvent is closely related to the solubility of the target ingredient. Fat-soluble ingredients (e.g., anthraquinones) are commonly used, such as n-hexane [12], dichloromethane [88], and ethyl acetate. Medium polar components (e.g., flavonoid glycosides) are mostly solvated with methanol [47,55], ethanol [31,56,68] (95%), or a mixture [84] thereof. Water-soluble components (e.g., polysaccharides [29]) are enriched by high-temperature aqueous [89] extraction combined with ethanol precipitation (4 °C), supplemented by large-pore resin decolorization/deproteinization for purification [79,90,91].

Column chromatography, liquid chromatography, and thin-layer chromatography have been utilized to isolate specific compounds [47]. In column chromatography, mobile phases like H2O-MeOH, EtOAc-MeOH, n-hexane-chloroform, and chloroform-ethyl acetate are commonly employed. Medium-pressure liquid chromatography (MPLC) is also used to extract phytochemicals from dichloromethane extracts of M. citrifolia, employing gradient elution with petroleum ether, chloroform, and chloroform enriched with methanol (1%, 2%, and 5%) [88]. Sigma-Aldrich thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plate preparation thin-layer chromatography is utilized to purify bioactive phytochemicals from distinct fractions [29]. Tan [92] utilized a mobile phase of toluene/ethyl acetate/formic acid in the ratio of 5:4:1 to extract compounds like caffeic acid, linalool, kaempferol, and gallic acid in combinations of noni, Coriandrum sativum L., and Aegle marmelos (L.) Corrêa.

The identification of both quantitative and qualitative aspects of isolated products is conventionally carried out through the use of high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with ultraviolet and mass spectrometry (HPLC-UV/MS) [31] and HPLC-MS. Identification of different compounds is achieved by comparing their HPLC retention time, UV absorbance of target peaks, and mass/charge ratio. Deng [31] extracted noni leaves by diafiltration, and the extracts were analyzed by HPLC. Four flavonoids in the extracts were identified by comparing the retention times and the subsequent characterization of the target peaks by MS and UV spectroscopy against the standards. For compounds of unknown structure, after isolation and purification, structural analysis is usually carried out by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and high-resolution fast atom bombardment- mass spectrometry (HRFAB-MS) spectroscopy. Hu [56] isolated and purified two white powders from the ethanolic extract of noni fruit, and the two glycosides were identified by NMR spectroscopy as (2E,4E,7Z)-deca-2,4,7-trienoate-2-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-β-D-glucopyra-noside and amyl-1-O-β-D-apio-furanosyl-1,6-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, and Wang [68] analyzed three new compounds using 1D and 2D NMR spectra with TMS as an internal standard: methyl 3-(2,4-dihydroxy-5-methoxyphenyl) propionate, butyl 3-(2,4-dihydroxy-5-methoxyphenyl)propionate, and 5-hydroxyhexyl 2-hydroxypropanoate.

The antioxidant efficacy of M. citrifolia extracts is critically influenced by the following extraction techniques:

Ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) achieves higher yields of polyphenols (e.g., scopoletin) and iridoids (e.g., asperulosidic acid) due to cavitation-induced cell wall disruption, preserving thermo-sensitive antioxidants [11].

Microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) excels in polysaccharide recovery (∼85% efficiency) through rapid dielectric heating yet may degrade heat-labile flavonoids [80].

A recent comparative study demonstrated that UAE extracts exhibited superior DPPH radical scavenging activity (IC50: 12.3 μg/mL) compared to MAE (IC50: 18.7 μg/mL), highlighting the need for method-specific optimization based on target compounds [20].

6. Traditional Use

The Tahitians discovered the medicinal value of M. citrifolia around 400 A.D. Traditional remedies mainly utilize the bark, leaves, and green fruits primarily for localized disease treatment [2]. Figure 8 shows images of different parts of the M. citrifolia plant. The bark of M. citrifolia is used for bacterial infections or abortions. M. citrifolia leaves are employed in addressing bacterial infections, inflammation, abdominal pain, and diarrhea [93]. Green fruits are utilized for various purposes, including combating bad breath, bacterial or fungal infections, menstrual cramps, arthritis, stomach ulcers, mouth ulcers, toothache, and indigestion. Ripe fruits can treat parasitic or bacterial infections and serve as an emmenagogue or for bowel cleansing. In the Republic of Palau, noni is frequently utilized as a traditional remedy for diabetes and hypertension. These remedies are typically available in the form of decoctions, juices, or can be chewed directly [94]. Pikad Tri-phol-sa-mut-than is an ancient traditional herbal formula [95], also written as Phikud Tri-Phon (PTP), a combination of noni, coriander, and dried mukul fruits in a 1:1:1 ratio (w:w), which can be used as a tonic for treating gastrointestinal ailments, fevers, and trichotomies as well as an antiemetic or laxative.

Figure 8.

The green fruits (A), leaves (B), and bark (C) of M. citrifolia.

Despite their unpleasant taste and bitter flavor, noni serves as a viable option during periods of crop failure and food scarcity. Locals on certain Pacific islands consume fresh or cooked noni as a staple food [96]. Additionally, indigenous populations in Southeast Asia and Australia enjoy the raw fruits with salt or incorporate them into curry dishes. The seeds of noni are edible as well, but they should be toasted over a fire before consumption. Rich in vitamins, noni has been used as a health tonic or medicinal beverage by South Pacific islanders for over two thousand years, making it a valuable tropical fruit resource [26].

7. Pharmacological Activity of M. citrifolia

A systematic analysis of the existing literature reveals that current investigations on Morinda citrifolia predominantly focus on its multifaceted pharmacological activities, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anticancer, and antimicrobial effects. These properties are mechanistically linked to its rich repertoire of bioactive compounds, such as anthraquinones, flavonoids, and polysaccharides. As summarized in Figure 9, the pharmacological profile of M. citrifolia encompasses both in vitro and in vivo evidence, highlighting its therapeutic potential across diverse disease models.

Figure 9.

Pharmacological activities of M. citrifolia. Upward-pointing arrows denote upregulated expression levels of cytokines/proteins or elevated damage indicators, whereas downward-pointing arrows represent corresponding downregulation of these biological parameters.

7.1. Antioxidant Activity

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced under physiological conditions as a byproduct of mitochondrial energy production and as an important “weapon” in phagocytosis. The antioxidant defense network is responsible for maintaining low basal levels of ROS by scavenging and converting them into nontoxic products and other mechanisms. Oxidative stress, triggered by the accumulation of excess ROS, is a well-documented contributor to various inflammatory and necrotic processes that are pivotal in the development of numerous diseases and injuries. To assess the antioxidant potential of compounds, DPPH and ABTS scavenging, as well as the measurement of antioxidant enzyme expression (like SOD and GPx), analyses are conducted in vitro. Animal models of high-fat diet-induced oxidative damage in the liver are used in vivo. In the case of M. citrifolia, polyphenol, iridoids, scopoletin, and polysaccharide components are recognized as the main antioxidants. Phenolic extract of M. citrifolia fruits significantly increases the activities of antioxidant enzymes to effectively attenuate oxidative stress in a high-fat diet-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) mouse, such as glutathione (GSH) and catalase (CAT) [97]. In another study, antioxidant properties of silver nanoparticles synthesized from Gerbera leaf extract were observed in vitro [98]. Additionally, the DPPH free radical scavenging capacity of the Thai traditional group formula PTP (consisting of A. marmelos, M. citrifolia, and C. sativum) was assayed with an IC50 of 92.4 ± 6.6 μg/mL [99]. Noni wine was found to regulate the Nrf2 pathway and increase the expression of antioxidant enzyme genes in high-fat diet mice [78].

Notably, the molecular weight of noni polysaccharides has a significant impact on their antioxidant efficacy [100]. Recent studies demonstrate that noni polysaccharides (NFP) exert potent antioxidant effects by scavenging ROS (e.g., DPPH radical inhibition rate > 70%) and activating the Nrf2/Keap1 pathway. In high-fat diet models, NFP significantly upregulated hepatic SOD and CAT levels while reducing malondialdehyde (MDA), suggesting its dual role in mitigating oxidative stress and inflammation via gut microbiota modulation [79]. The preservation of noni through fermentation is an ancient technique that not only reduces its unpleasant odor but also enhances its immune-boosting and antioxidant properties. Zhou [20], Li [80], and Zhang [101] found that noni polysaccharides and their derivatives have DPPH radical neutralization rates over 70% in vitro. This scavenging capacity highlights the potential of noni polysaccharides as potent antioxidants capable of reducing oxidative stress in biological systems.

In one study [102], the ethanolic extract of M. citrifolia leaves treated liver damage rats by elevating liver antioxidant enzymes. Further research investigated the antioxidant activity of lignin present in M. citrifolia leaves; the findings suggest that lignin is highly effective in capturing free radicals because of phenolic groups [103]. A summary of antioxidant activity studies for M. citrifolia can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of antioxidant activity studies of M. citrifolia.

| No. | Parts | Animal/Cell | Model | Application Part or Compounds | Dose | Pharmacological Activity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Leaves | N/A | In vitro: DPPH, ABTS | M. citrifolia leaf extract silver nanoparticles | 17.70, 13.37 μg/mL | Scavenging radical | [98] |

| 2 | Fruits | N/A | In vitro: DPPH, ABTS | Polysaccharide | 0.2–1 mg/mL | Scavenging radical | [100] |

| 3 | Fruits | N/A | In vitro: DPPH | PTP | 3.91–2000 µg/mL | Scavenging radical | [99] |

| 4 | Fruits | C57BL/6 mice | High-fat diet-induced fatty liver | Phenolic extract | 100, 200 mg/kg | Elevating MDA levels and decreasing GSH levels and CAT activity in mice with NAFLD | [97] |

| 5 | Fruits | C57BLKS mice, HepG2 cells | In vitro: 50 mM high glucose established insulin-resistant In vivo: 10 mg/kg/d rosiglitazone (ROSI)-induced oxidative stress model |

Fermented noni juice (FNJ) | 6.5, 13 mL/kg | Activation of the Nrf2/ARE (Antioxidant Response Element) signaling pathway and modulation of intestinal flora in db/db mice and IR-HepG2 cells | [101] |

| 6 | Fruits | N/A | In vitro: hydroxyl radical scavenging capacity, superoxide anion scavenging capacity and anti-lipid peroxidation capacity | Polysaccharide | 0.2–3.2 g/L | Scavenging radical | [20] |

| 7 | Leaves, Fruits | N/A | In vitro: DPPH | Methanol extract | 300 µg/mL | Scavenging radical | [104] |

| 8 | Leaves | N/A | In vitro: DPPH, ABTS | Lignin | 175.34 μg/mL | Scavenging radical | [103] |

| 9 | Leaves | The freshwater catfish, P. sutchi | Freshwater catfish fed 5.75 mg/L cadmium | Methanol extract | 200 mg/kg | Reducing oxidative stress in a time-dependent manner | [105] |

| 10 | Fruits | N/A | Total antioxidant capacity test | M. citrifolia fruit ethanol extracts | 0.823–2.106 U/mL | Antioxidant activity | [106] |

| 11 | Leaves | N/A | Phospho molybdenum-based method | Flavonoid-rich M. citrifolia methanol extracts | 350 μg/mL | Intracellular membrane damage, cell cycle blockade | [107] |

| 12 | Fruits | C57BL/6J mice | High-fat diet-induced oxidative stress and disorders of lipid metabolism | Fruit wine | 10, 20, 40 mL/kg | Reduction of hepatic ROS and MDA levels and increasing serum and hepatic antioxidant enzyme activities | [78] |

| 13 | Fruits | Sprague-Dawley (SD) Rat | High-fat diet-induced oxidative stress and disorders of lipid metabolism | Polysaccharide | 100 mg/kg | Modulation of intestinal flora and SCFA production reduction of colonic barrier permeability and metabolic endotoxemia, thereby attenuating hepatic oxidative stress and inflammation in High-Fat Diet (HFD) rats | [79] |

| 14 | Fruits | N/A | In vitro: DPPH, ABTS | Polysaccharide | 0.2–5 mg/mL | Scavenging radical | [80] |

| 15 | Fruits | Kunming mice | High-fat diet-induced oxidative stress and disorders of lipid metabolism | Noni fruit water extract (NFW), Noni fruit polysaccharide (NFP) | 50, 100, 200 mg/kg | Increasing the hepatic nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor level | [81] |

| 16 | Leaves | SD rat | Obesity and hepatic oxidative stress induced by thermoxidized palm oil diet | Ethanol extract | 500, 1000 mg/kg | Elevating liver antioxidant enzymes | [102] |

Notes: N/A, data not available.

7.2. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of M. citrifolia

Inflammation is a crucial factor in the development of many chronic and severe diseases. Available research suggests that M. citrifolia exerts its anti-inflammatory effects through multiple pathways (Table 4) via its active components, including phenolic compounds, polysaccharides, and specific proteins. The anti-inflammatory effects of M. citrifolia have been validated in multidimensional experimental models such as those for lipopolysaccharide-induced cellular models, inflammatory bowel disease, mouse esophagitis models, rheumatoid arthritis, pneumonia in mice, edema models, and steatohepatitis.

In an in vitro cellular model, noni seed extract reduced tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells [108]. Furthermore, PTP, a traditional Thai herbal formulation containing M. citrifolia, demonstrated notable inhibitory effects on various inflammatory models. PTP extract exhibited significant inhibitory effects on ethyl phenylpropionate-induced rat ear edema and carrageenan or arachidonic acid-induced rat hind paw edema [92]. In another study, fermented noni juice reduced the expression of NLR family pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) and TNF-α and attenuated ankle edema caused by monosodium urate, demonstrating its therapeutic activity in acute gouty arthritis [109]. Phenolic compounds extracted from ripe fruits can reduce the level of intestinal inflammatory factors caused by a high-fat diet [110]. This finding corroborates the research conducted by Dyah Aninta Kustiarini [111]. M. citrifolia polysaccharide can inhibit the NF-κB signaling pathway and regulate the intestinal flora, which reduces intestinal damage and treats inflammatory bowel disease [91]. Lastly, deacetylasperulosidic acid (DAA), a cyclic enol ether terpene compound abundant in M. citrifolia fruits, concentration-dependently controlled mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) phosphorylation in TNF-α and interferon-γ (IFN-γ)-treated human adult cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (HaCaT) cells during in vitro studies, suggesting that DAA is a potential anti-atopic dermatitis candidate for restoring T helper cell 1/T helper cell 2 (Th1/Th2) immune balance and enhancing skin barrier function [112].

The stems and seeds of M. citrifolia, the non-medicinal parts, had anti-inflammation activity due to bioactive compounds. It has been found that noni stem bark effectively iNOS, thereby inhibiting nitric oxide (NO) production and exerting anti-inflammatory activity [113]. Research has revealed that noni seeds, typically discarded in the juice production process, exhibit significant anti-inflammatory capabilities. Further investigation [18] identified a heat-stable anti-inflammatory lipid transfer protein, M. citrifolia lipid transfer protein (McLTP1), present in noni seeds, which was confirmed to mitigate the side effects associated with irinotecan-induced intestinal mucositis [114].

Table 4.

Summary of studies on anti-inflammatory activity of M. citrifolia.

| No. | Parts | Animal/Cell | Model | Application Part or Compounds | Dose | Pharmacological Activity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Seeds | RAW 264.7 cells | LPS-induced inflammation | Cannabidiol, M. citrifolia seed extract | 100 μg/mL | Reduction of the expression of inflammatory mediators | [113] |

| 2 | Fruits | C57BL/6 mice | High-fat diet-induced obesity | Phenol extract | 100, 200 mg/kg | Enhancement of gut microbiome balance and intestinal barrier integrity, coupled with a decrease in inflammatory responses | [110] |

| 3 | Fruits | MH7A cells | N/A | Pyranone derivatives, alkaloids, lignans, glycosides | 3.69–168.96 µmol/L | Inhibition of MH7A synovial fibroblast proliferation in vitro | [85] |

| 4 | Fruits | SD rat | Ethyl phenylpropiolate-induced ear edema, carrageenan- and arachidonic acid-induced hind paw edema | PTP extract | 150, 300, 600 mg/kg | Effective reduction of various inflammatory mediators | [115] |

| 5 | Seeds | Swiss mice | Irinotecan-stimulated intestinal mucositis | McLTP1 | 8 mg/kg | Lipid transfer protein McLTP1 significantly prevents irinotecan-induced intestinal damage, reduces intestinal muscle hypercontractility, and has anti-inflammatory activity | [92] |

| 6 | Fruits | Kunming mice | Sodium urate-induced acute gouty arthritis | M. citrifolia L. fruit juice | 7.8 mL/kg | Modulation of miRNA molecules with the ability to regulate the development of acute gouty arthritis and reduction in inflammatory cytokines interleukin 6 (IL-6), interleukin 8 (IL-8), and TNF-α in acute gouty arthritis in mice | [114] |

| 7 | Fruits | C57BL/6 mice | Dextran sulfate sodium induced inflammatory bowel disease | Polysaccharide | 10 mg/kg | Noni polysaccharides containing homogalacturonan and rhamnogalacturonan-I structural domains may alleviate inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) by modulating the gut microbiota and inhibiting inflammation-related signaling pathways | [91,109] |

| 8 | Stems, Leaves | MH7A cells | N/A | Sesquiterpenes, steroids, lignans, and fatty acids | 38.69–203.45 μmol/L | Inhibition of MH7A synovial fibroblast proliferation | [91] |

| 9 | Seeds | RAW 264.7 cells | N/A | Cannabidiol, M. citrifolia seed extract | 100 μg/mL | Reduction in the expression of inflammatory mediators | [116] |

| 10 | Fruits | HaCaT, Human Mast Cell-1 (HMC-1) and Eosinophilic Leukemia-1 (EOL-1) Cells | LPS-induced inflammation | Deacetyl asperulosidic acid, asperulosidic acid | 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2 μmol/L | Activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway, regulation of Th1/Th2 immune balance, and enhancement of skin barrier function | [112] |

| 11 | Fruits, Leaves, Seeds | RAW 264.7 cells | High-fat diet induced oxidative stress, inflammation, and intestinal dysbiosis in the liver | Noni fruit, leaf extract, noni fruit seed extract, noni fruit essential oil | 100 μg/mL | Reduction in expression of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α | [108] |

| 12 | Fruits | SD rat | Acetic acid-induced colitis | Polysaccharide | 100 mg/kg | Modulation of intestinal flora and SCFA production, reduction of colonic barrier permeability and metabolic endotoxemia, thereby attenuating hepatic oxidative stress and inflammation in HFD rats | [79] |

| 13 | Fruits | Swiss mice | LPS-induced inflammation | Polysaccharide | 3 mg/kg | Reduction in inflammatory cell infiltration, oxidative stress, pro-inflammatory cytokines, COX-2, and iNOS expression in the inflamed colon | [90] |

| 14 | Fruits | RAW 264.7 cells | Intra-articular monosodium iodoacetate injection into the right knee induced osteoarthritis | Asperulosidic acid, rutin, nonioside A, (2E,4E,7Z)-deca-2,4,7-trienoate-2-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-β-D-glucopyranoside, tricetin | 50 µg | Activation of iNOS and COX-2 and regulation of NO production | [117] |

| 15 | Leaves | SD rat | Mannitol-induced arthritis | M. citrifolia leaves extract | 400 mg/kg | Inhibition of inflammation, NO production, protease-induced joint catabolism, and oxidative stress | [118] |

| 16 | Fruits | Saccharomyces cerevisiae Kinase Gene (SKG) mice | IBD induced by 2% sucrose solution | Noni fruit juice | Fruit juice mixed with drinking water in equal proportions | Suppression of arthritis and histopathology scores | [111] |

| 17 | Fruits | Wild-type Groningen rat | COVID-19 | 30.56% Colostrum and 11.11% M. citrifolia juice blend | 0.5 g/kg | Reduction in interleukin-10 (IL-10), interleukin-12 (IL-12), and TNF-α protein | [119] |

| 18 | Fruits | Patients | N/A | Papaya and noni fruit fermented syrup | 14 g/d | Reduction in IL-6, IL-8, and NO metabolites | [120] |

| 19 | Fruits | RAW 264.7 cells, Balb/c mice | N/A | Fermented noni fruit polysaccharide | 100, 200 mg/kg | Increasing NO and pro-inflammatory cytokine release, activation of COX-2 and iNOS | [121] |

| 20 | Fruits | RAW 264.7 cells, C57BL/6 mice | Prednisolone-induced immunosuppression in rats LPS-induced Tohoku hospital pediatrics-1 (THP-1) macrophages | Noni fruit ethanol extract | 50, 200 mg/kg | Activation of NF-κB and Activator Protein-1 (AP-1) pathways and increasing mRNA expression of IL-6, IFN-β, TNF-α, interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) and IL-12b in RAW 264.7 cells | [122] |

| 21 | Fruits | Balb/c mice, The human monocyte cell line (THP-1, ATCC TIB-202) | 2,6-Dinitro-1-chlorobenzene (DNCB) induced atopic dermatitis-like lesions | Noni fruit ethanol extract | 200 mg/kg | Downregulating LPS-induced TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6/IL-10, while attenuating iNOS and NF-κB expression | [123] |

| 22 | Fruits | NC/Nga mice | N/A | Fermented Noni Juice | 250, 500, 1000 mg/kg | Regulation of the Th1/Th2 immune balance as well as the T helper cell 17 (Th17) and T helper cell 22 (Th22) immune responses and reduction of the infiltration of inflammatory cells | [124] |

| 23 | Fruits | RAW264.7 cells, C57BL/6 mice | LPS-induced inflammation | M. citrifolia fruit water extract | 0–400 μg/mL | Activation of NF-κB and AP-1 signaling pathways, induction of NO, regulation of immune cell populations, induction of pro-inflammatory cytokine gene expression, and inhibition of IL-10 expression |

[125] |

Notes: N/A, data not available.

7.3. Anticancer Activity of M. citrifolia

Over the last five years, hot spots on noni juice and its extracts have included anticancer studies. Utilizing various cancer cell lines and combining computer simulation technology, these studies aim to explore the inhibitory effects of M. citrifolia on cancer cell growth and proliferation (Table 5). Compounds in M. citrifolia, like anthraquinone, have shown excellent anticancer activity, such as nordamnacanthal, damnacanthal morindone, and rubiadin [126]. In a comprehensive study, researchers identified eight anthraquinone compounds that demonstrated in vitro proliferative suppression comparable to that of adriamycin on various tumor cell lines, HL-60 human promyelocytic leukemia cell line (HL-60), Shanghai Medical College of Fudan University hepatocellular carcinoma-7721 (SMMC-7721), A-549, michigan cancer foundation-7 (MCF-7), and SW480 human colon cancer cell line (SW480), owing to the interaction of these compounds with key residues of multiple targets via carbonyl oxygen or van der Waals forces, which has been elucidated by molecular docking methods [127].

Reports indicate that the anthraquinone compounds extracted from M. citrifolia have selective activity against colorectal cancer cells [6]; morindone and rubiadin exhibited binding affinity towards targets like β-catenin, murine double minute 2-p53 protein (MDM2-p53), and kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS). By molecular docking, pharmacophore modeling, induced-fit docking, and molecular dynamics simulations, five compounds with anti-hepatocellular carcinoma activities, namely soranjidiol, thiamine, lucidin, 2-methyl-1,3,5-Trihydroxyanthraquinone, and rubiadin, could be screened out from the compounds of M. citrifolia by using B-Raf kinase as a target [128]. A study of lung cancer further found that noni juice inhibits the expression of proliferation proteins such as Ki67 in tumor cells and promotes the expression of apoptosis-related genes to play an anti-lung cancer role [129], the promotion of apoptosis of cancer cells by M. citrifolia extract was also observed in leukemic mice [130]. However, further research is needed to fully explore their efficacy against human cancer.

Table 5.

Summary of studies on anticancer activity of M. citrifolia.

| No. | Parts | Animal/Cell | Model | Application Part or Compounds | Dose | Pharmacological Activity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fruits | HL-60, SMMC-7721, A-549, MCF-7, and SW480 tumor cell lines | N/A | New anthraquinone: moricitrifone and 7 other known anthraquinones | 0.26–16.58 μmol/L | Antiproliferative activities | [127] |

| 2 | Roots | HCT116 human colon cancer cell line (HCT116), LS174T human colon cancer cell line (LS174T), HT29 human colon cancer cell line (HT29) | N/A | Morindone, rubiadin | 0.25–64 μM | Cytotoxicity to colorectal cancer cells | [6] |

| 3 | Fruits | A-549 cells, BLAB/c nu/nu mice | A-549 cells were inoculated into the right axilla | Noni juice | in vitro: 50 μL/mL; in vivo: 0.2 mL/10 g, 0.4 mL/10 g | AKT/NF-κB signaling pathway | [129] |

| 4 | Seeds | A-549 and human prostate cancer (LNCaP) cell lines | N/A | MCEO-CHs NPs (nanoparticles of noni fruit essential oil loaded with chitosan) | 5–25 μL/mL | Cytotoxicity to cancer cells | [131] |

| 5 | Leaves | In vitro: Jurkat leukemia and Walter and Eliza Hall institute-3B (WEHI-3B) cell lines; in vivo: Balb/c mice | Leukemic | Ethanol extract | in vitro: 1.562–100 μg/mL; in vivo: 100, 200 mg/kg | Affecting immunity, suppressing inflammation, and upregulating apoptosis | [130] |

Notes: N/A, data not available.

7.4. Hypoglycemic Activity of M. citrifolia

For many years, noni has been used in Indonesia and Polynesia as a natural remedy for diabetes. To investigate this traditional use scientifically, diabetes models are usually induced using a combination of a high-fat, high-sugar diet, streptozotocin (50 mg/kg BW), and tetracycline (Table 6). The study revealed that noni components had therapeutic activity for type 2 diabetes by inhibiting α-amylase and α-glucosidase activities and exerting insulin-like effects [132]. Human pancreatic α-amylase is a crucial target for treating type 2 diabetes mellitus. In this context, utilizing molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations [133], ursolic acid demonstrated optimal binding energy in molecular docking simulations with α-amylase, and molecular dynamics confirmed this, suggesting its potential as a therapeutic agent for diabetes management. Xu [134] identified 15 compounds in noni seeds that showed α-glucosidase inhibitory activity. Another study [135] examined the mixtures of noni, mango, and pineapple; the sample was tested for α-glucosidase inhibitory activity, as well as α-amylase inhibitory activity using acarbose as a control. The results of this study suggested that the combination of these three fruit extracts possessed exceptional in vitro antidiabetic activity and was further confirmed in an in vivo validation assay of the streptozotocin-induced diabetes model in SD rats.

Table 6.

Summary of studies on hypoglycemic activity of M. citrifolia.

| No. | Parts | Animal/Cell | Model | Application Part or Compounds | Dose | Pharmacological Activity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fruits | Mice | Streptozotocin-induced diabetes | Ursolic acid, sterol compound | N/A | Inhibiting glucose | [133] |

| 2 | Seeds | N/A | N/A | Compounds isolated by ethyl acetate and petroleum ether extraction of noni seeds | 160, 133, 120 μmol/L | α-Glucosidase inhibitory activity | [134] |

| 3 | Fruits | SD rat | Diabetes conditions were induced by streptozotocin | Plant extracts made up of noni (M. citrifolia), pineapple (Ananas comosus), and mango (Mangifera indica) | 4.04 ± 0.03 mg/mL 3.42 ± 0.02 mg/mL |

Inhibition of α-glucosidase and α-amylase | [135] |

| 4 | Fruits | Swiss mice | High-sugar, high-fat diet (21.20% carbohydrate; 18.86% protein; 4% soybean oil, 31% lard, and 20% fructose) | Fruit water extract | 500 mg/kg | Up-regulation of peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor alpha (PPAR-α) expression in adipose tissue and down-regulation of peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ), PPAR-α, sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c), and fetuin-A expression in liver | [136] |

Notes: N/A, data not available.

7.5. Antimicrobial Activity of M. citrifolia

Antimicrobial activity is usually assessed using the disk diffusion method (Table 7). Dried M. citrifolia root powders were sequentially extracted by hexane, dichloromethane, ethyl acetate, and ethanol; the inhibition zone showed that hexane extracts have inhibitory effects on S. aureus, S. epidermidis, and B. cereus, while the dichloromethane extract exhibited the inhibition of E. coli with an inhibition zone of 5.5 mm, the ethyl acetate extract of the root showed inhibition against P. aeruginosa and S. epidermidis. They also tested the antitubercular activity of M. citrifolia using a microplate Alamar Blue assay and found that the ethanol extract of M. citrifolia leaves showed 89% inhibition of M. tuberculosis at a 100 μg/mL concentration [3]. As a dental disinfectant [137], the water extract of M. citrifolia was shown to disinfect better than conventional disinfectant and photodynamic therapy in a model of dental metal–ceramic crown disinfection. Because of this, the cerium oxide nanoparticles of noni assembled exhibit bacteriostatic activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and were more effective than amoxicillin [138].

Table 7.

Summary of studies on the antimicrobial activity of M. citrifolia.

| No. | Parts | Animal/Cell/Microbiology | Method | Application Part or Compounds | Inhibition Zone | Pharmacological Activity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Roots | B. cereus, S. aureus, S. epidermidis, E. coli, M. tuberculosis, and P. aeruginosa | Disk diffusion method | Dichloromethane root extract (10 μL) hexane root extract (10 μL) ethyl acetate root extract (10 μL) |

E. coli (5.5 mm) S. aureus (4.0 mm) B. cereus (5.0 mm) P. aeruginosa (5.5 mm) |

Inhibitory of E. coli, S. aureus, B. cereus, and P. aeruginosa | [3] |

| 2 |

M. citrifolia extract |

S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and C. albicans | Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) | M. citrifolia extract (6.25%), zinc oxide |

S. aureus (16.33 mm) P. aeruginosa (28.5 mm) C. albicans (10 mm) |

Strong inhibitory effect on S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and C. albicans | [139] |

| 3 | Fruits | Fusobacterium, Candida albicans, and Prevotella | Antimicrobial susceptibility testing | Noni fruit juice |

Fusobacterium (12.8 mm) Candida albicans (11.6 mm) Prevotella (12.4 mm) |

Antibacterial activity | [140] |

8. Safety Studies on M. citrifolia

As of July 2024, no prescription or over-the-counter (OTC) drug using noni as the main active ingredient has been formally approved by mainstream international drug regulatory agencies (e.g., U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), European Medicines Agency (EMA) of the European Union, China National Medical Products Administration (NMPA)). Currently, the drug-level development of noni-related ingredients is still in the early research stage, and some of the progress includes the following: Animal experiments have shown that noni polysaccharides may improve insulin resistance, but they have not yet entered the anti-diabetic clinical trials. Anthraquinone components (e.g., damnacanthal) have shown in vitro inhibitory effects on hepatocellular carcinoma and colon cancer cells, but clinical data are lacking. Iridoids (e.g., asperuloside) are well-studied for their anti-inflammatory mechanisms but have not entered the drug development pipeline.

Although M. citrifolia has been used as a complementary treatment for cancer and is liver protective [141,142,143], the safety of M. citrifolia is controversial. Cases of M. citrifolia acute hepatitis-like illnesses have been reported [144,145], while in vivo and in vitro studies have shown no evidence of hepatotoxicity or acute hepatocellular injury [146]. The research on genotoxicity found that M. citrifolia fruit and seed substances have no mutagenic potential to induce chromosome damage [147]. Similarly, the safety tests on commercial noni juice demonstrated no adverse effects on the liver for both humans and animals. These findings suggest that noni fruits and seeds are not mutagenic or disruptive [148].

Meanwhile, in a reproductive toxicity test [149], it was observed that the administration of high doses of M. citrifolia water extracts to pregnant rats resulted in liver damage, along with adverse reproductive effects. These effects included anticonception properties, intrauterine growth restriction, and fetal malformations, highlighting potential risks to both the mother and the fetus. This is contrary to the results that the subcutaneous injection of water extracts of M. citrifolia in mice does not cause toxicity to the reproductive system [150]. This discrepancy between the studies underscores the complexity of the impact of noni on the reproductive system. Given these conflicting results, further toxicological research is warranted. Such studies will be crucial for establishing a comprehensive safety profile and guiding the responsible use of noni extracts.

9. Discussion

The primary thrust of M. citrifolia research is to unravel the health benefits of noni juice or its extracts, aiming to pinpoint its potential as a remedy for various human diseases [151,152,153]. In diseases, M. citrifolia extracts activate NF-κB and AP-1 pathways and down-regulate inflammatory factors (IL-6, IFN-β, TNF-α, and IL-1β) [112].

M. citrifolia polysaccharides (NFPs) have emerged as key bioactive compounds that mitigate oxidative stress through dual mechanisms: direct free radical scavenging and indirect modulation of gut microbiota. Studies reveal that NFP promotes the proliferation of beneficial bacteria (e.g., Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium), which ferment dietary fiber to produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate. Butyrate activates the Nrf2/Keap1 pathway, upregulating antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT, GPx) while suppressing ROS generation. Additionally, NFP enhances intestinal barrier integrity by increasing tight junction proteins (e.g., occludin), thereby reducing systemic endotoxin leakage and subsequent oxidative damage [91]. These findings position M. citrifolia as a potent modulator of the gut–liver axis in combating oxidative stress-related pathologies.

This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview that bridges the gap between traditional knowledge and scientific understanding, shedding light on the multifaceted applications of M. citrifolia across human and animal healthcare. The multifaceted antioxidant properties of M. citrifolia underpin its potential in diverse industries, such as the following.

Functional Foods: Incorporation of noni polysaccharides into nutraceuticals could address diet-induced oxidative stress, significantly increasing the antioxidant liver enzymes SOD and GPx [81].

Cosmeceuticals: Topical formulations containing noni seed (50%) ethanolic extract demonstrate anti-aging effects by inhibiting matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) and down-regulation of MAPK phosphorylation in UVA-irradiated normal human dermal fibroblasts [154].

Livestock Production: As a feed additive, noni powder (0.2% w/w) reduced oxidative damage in broilers exposed to heat stress, improving feed conversion ratio and meat quality via lipid peroxidation inhibition [155]. Challenges such as odor palatability may be overcome through microencapsulation or fermentation-based masking techniques. It can improve livestock physiology and performance [156]. Adding noni fruit powder to the diet could promote the growth of black goats and improve immunity and antioxidant ability [157] because noni fruit polysaccharides may help ruminants metabolize nutrients [158] and alleviate rumen acidosis [159]. The addition of noni has also been reported in broiler and Holstein cow diets [155,160]. M. citrifolia is an extremely valuable natural source of antioxidants. Studies have found that coccidian infections can cause oxidative stress due to the production of ROS; certain phytopharmaceuticals with anticoccidial properties can provide some protection against this stress. For instance, the acetone extract of the traditional Chinese medicine Morinda officinalis has been shown to reduce oxidative damage and effectively prevent and control avian coccidiosis [161]. Noni and Morinda officinalis are closely related as they both belong to the genus Morinda. M. citrifolia contains phenolic compounds, saponins, essential oils (including terpenes and their derivatives) [162], and other compounds that have demonstrated anticoccidial effects through various mechanisms of action.

10. Conclusions

Future research should prioritize three key areas. Firstly, it is crucial to gain mechanistic depth by elucidating how noni-derived compounds synergistically regulate the crosstalk between oxidative stress and inflammation. Secondly, application-driven studies are needed to develop nanoformulations or fermented products to enhance the bioavailability and stability of antioxidant constituents. Thirdly, sustainable utilization should be emphasized, specifically by validating noni’s role as a livestock feed additive to mitigate oxidative damage in agriculture, which aligns with One Health initiatives. By integrating traditional wisdom with cutting-edge science, M. citrifolia holds immense potential as a sustainable, multi-target antioxidant agent, offering novel strategies for combating oxidative stress-related diseases and promoting global health.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| A-549 | Human non-small cell lung cancer cells |

| ABTS | 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonicacid) |

| AP-1 | Activator Protein-1 |

| ARE | Antioxidant Response Element |

| CAT | Catalase |

| CNKI | China National Knowledge Infrastructure |

| DAA | Deacetylasperulosidic Acid |

| DNCB | 2,6-Dinitro-1-chlorobenzene |

| DPPH | 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| EMA | European Medicine Agency |

| EOL-1 | Eosinophilic Leukemia-1 |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FNJ | Fermented Noni Juice |

| GPx | Glutathione Peroxidase |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| HaCaT | Human Adult Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma |

| HCT116 | HCT116 human colon cancer cell line |

| HFD | High-Fat Diet |

| HL-60 | HL-60 human promyelocytic leukemia cell line |

| HMC-1 | Human Mast Cell-1 |

| HPLC | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| HRFAB | High-Resolution Fast Atom Bombardment |

| HT29 | HT29 human colon cancer cell line |

| IBD | Inflammatory Bowel Disease |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-γ |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| IL-12 | Interleukin-12 |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-8 | Interleukin-8 |

| iNOS | Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| Keap1 | Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 |

| KRAS | Kirsten Rat Sarcoma Viral Oncogene Homolog |

| LNCaP | Human prostate cancer |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| LS174T | LS174T human colon cancer cell line |

| M. citrifolia | Morinda citrifolia L. |

| MAE | Microwave-Assisted Extraction |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |