Abstract

Objective

To assess the evidence for the efficacy of local treatments for cutaneous warts.

Methods

Systematic review of randomised controlled trials.

Main outcomes measures

Total clearance of warts and adverse effects such as irritation, pain, and blistering.

Study selection

Randomised controlled trials of any local treatment for uncomplicated cutaneous warts. All published and unpublished material was considered, with no restriction on date or language.

Results

50 included trials provided generally weak evidence because of poor methods and reporting. The best evidence was for topical treatments containing salicylic acid. Data pooled from six placebo controlled trials showed a cure rate of 75% (144 of 191) in cases compared with 48% (89 of 185) in controls (odds ratio 3.91, 95% confidence interval 2.40 to 6.36). Some evidence for the efficacy of contact immunotherapy was provided by two small trials comparing dinitrochlorobenzene with placebo. Evidence for the efficacy of cryotherapy was limited. No consistent evidence was found for the efficacy of intralesional bleomycin, and only limited evidence was found for the efficacy of topical fluorouracil, intralesional interferons, photodynamic therapy, and pulsed dye laser.

Conclusions

Reviewed trials of local treatments for cutaneous warts were highly variable in methods and quality, and there was a paucity of evidence from randomised, placebo controlled trials on which to base the rational use of the treatments. There is good evidence that topical treatments containing salicylic acid have a therapeutic effect and some evidence for the efficacy of dinitrochlorobenzene. Less evidence was found for the efficacy of all the other treatments reviewed, including cryotherapy.

What is already known on this topic

A wide range of local treatments is available for treating warts

No one treatment is strikingly effective and little is known about the absolute and relative efficacy of these treatments

What this study adds

High quality research on the efficacy of various local treatments for warts is lacking

Evidence, which is generally of a poor quality, shows a beneficial effect of topical salicylic acid and contact immunotherapy with dinitrochlorobenzene

Little evidence exists for the efficacy of cryotherapy and no consistent evidence for the efficacy of all the other treatments reviewed

Introduction

Viral warts are common, benign, and usually self limiting skin lesions that occur usually on the hands and feet.1 Extragenital warts in people who are immunocompetant are harmless and usually resolve spontaneously within months or years owing to natural immunity. In view of this, a policy of not treating them is often advised. However there is considerable social stigma associated with warts on the face and hands, and they can be painful on the soles of the feet and near the nails. Many patients request treatment for their warts.

Many local treatments are used for warts, but knowledge on the absolute and relative efficacy of these is incomplete. We systematically reviewed randomised controlled trials of any local treatment for uncomplicated warts to assess the evidence for their efficacy.

Methods

We conducted computer searches with standardised search strategies.2 We searched Medline (from 1966 to May 2000), Embase (from 1980 to August 2000), and the Cochrane controlled trials register (March 1999). We manually searched cited references from identified trials and recent review articles. We contacted pharmaceutical companies and experts in the specialty. We included non-English papers, which we had translated.

Two reviewers (SG and IH) independently examined the full text of all studies identified as possible randomised controlled trials. All studies in which participants were randomised to different interventions were included.

The reviewers assessed the quality of the methods from concealment of allocation, blinding of outcome assessment and handling of withdrawals, and dropouts.3 They also considered the adequacy of sample size, comparability of treatment groups at baseline, overall quality of reporting, and handling of data. Trial quality was classified subjectively and then by consensus as high, medium, or low quality. Trials clearly showing adequate concealment, blinding, and intention to treat analysis were classified as high quality.

The trials were then examined in detail and a descriptive synthesis drawn up, with pooling of dichotomous data when trials had a similar design, methods, and outcome. The main outcome examined was the complete clearance of warts. Data were pooled with the Cochrane Collaboration's review manager software. Because of the overall heterogeneity of the trials we used odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals as the main measure of effect with a random effects model.

Results

Fifty trials were identified from 45 papers (table).4–48 Further details of included and excluded trials are available in the Cochrane Library.49 Evidence from these studies was generally weak largely because of a lack of high quality trials. Overall, 41 (82%) trials were classified as low quality and seven as intermediate quality. Only two were classified as high quality.41,43 Moreover, the heterogeneity of the methods, particularly the unit of analysis used, hindered the pooling of data for many treatments. Despite this, some useful pooling of data was possible.

Placebo

Seventeen trials with placebo groups used individuals as the unit of analysis. The average cure rate of placebo preparations was 30% after an average period of 10 weeks.

Salicylic acid

Thirteen trials assessed topical salicylic acid. Various preparations were used, with salicylic acid ranging from 15% to 60%; only one trial used 60% salicylic acid, most using standard preparations of between 15% and 26% with or without lactic acid.

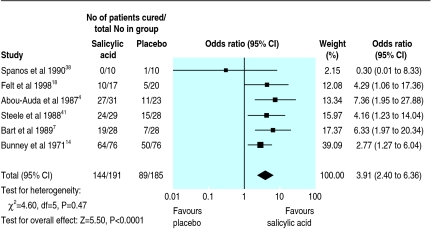

Data pooled from six placebo controlled trials showed a cure rate of 75% (144 of 191) in cases compared with 48% (89 of 185) in controls (odds ratio 3.91, 95% confidence interval 2.40 to 6.36; fig 1).

Figure 1.

Cure rates in trials comparing topical salicylic acid with placebo for treatment of cutaneous warts

In one placebo controlled trial one of 29 patients treated with a mixture of monochloroacetic acid and 60% salicylic acid developed cellulitis.41 Minor skin irritation was reported occasionally in some of the other trials, but generally there were no major harmful effects of topical salicylic acid.

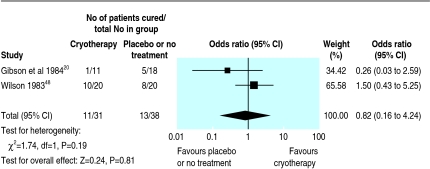

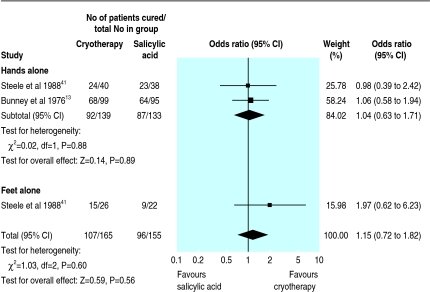

Cryotherapy

Sixteen trials assessed cryotherapy. Most of these studied different regimens rather than comparing cryotherapy with other treatments or placebo. Pooled data from two small trials including cryotherapy and placebo or no treatment showed no significant difference in cure rates (fig 2). In two other larger trials no significant difference in efficacy was found between cryotherapy and salicylic acid (fig 3).

Figure 2.

Cure rates in trials with cryotherapy and placebo or no treatment for treatment of cutaneous warts

Figure 3.

Cure rates in trials comparing cryotherapy with salicylic acid for treatment of cutaneous warts

Pooling of data from four trials showed “aggressive” cryotherapy (various definitions) to be significantly more effective than “gentle” cryotherapy, with cure rates of 52% (159 of 304) and 31% (89 of 288), respectively (3.69, 1.45 to 9.41).9,16,21,37 Reporting of side effects was less complete, but pain and blistering seemed to be more common with aggressive cryotherapy. Pain or blistering was noted in 64 of 100 (64%) participants treated with an aggressive (10 second) regimen compared with 44 of 100 (44%) treated with a gentle (brief freeze) regimen (2.26, 1.28 to 3.99).16 Five participants withdrew from the aggressive group and one from the gentle group because of pain and blistering.

Three trials examined the optimum treatment interval.11,13,24 No significant difference was found in long term cure rates between treatment at 2, 3, and 4 weekly intervals. In one trial pain or blistering was reported in 29%, 7%, and 0% of those treated at 1, 2, and 3 weekly intervals, respectively.11 The higher rate of adverse effects with a shorter interval between treatments might have been a reporting artefact due to participants being seen soon after each treatment.

Only one trial examined the optimum number of treatments.10 This trial showed no significant benefit of prolonging 3 weekly cryotherapy beyond 3 months (about four freezes) in participants with warts on the hands and feet.

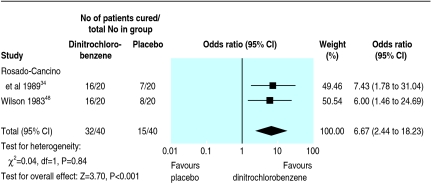

Topical immunotherapy with dinitrochlorobenzene

Two small trials comparing the potent contact sensitiser dinitrochlorobenzene with placebo showed some evidence for the efficacy of the active treatment.34,48 Pooled data showed cure rates of 80% (32 of 40) and 38% (15 of 40), respectively (6.67, 2.44 to 18.23; fig 4).

Figure 4.

Cure rates in trials comparing topical dinitrochlorobenzene with placebo for treatment of cutaneous warts

No precise data were found on adverse effects in either of these trials. One trial found that six of 20 participants treated with 2% dinitrochlorobenzene became sensitised only after a second application.34 All of them subsequently experienced major local irritation with or without blistering when they were treated with 1% dinitrochlorobenzene. None withdrew from the study.

Intralesional bleomycin

No consistent evidence was found for the effectiveness of intralesional bleomycin in five trials.12,22,28,32,35 Four of the trials, with widely varying results, used warts rather than individuals as the unit of analysis and could not be meaningfully pooled.12,22,28,35 Cure rates in all five studies ranged from 16% to 94%. Two trials showed higher cure rates with bleomycin than with placebo, one showed no significant difference between bleomycin and placebo, and one showed higher cure rates with placebo than with bleomycin.

None of these trials provided precise data on adverse affects. One trial reported adverse events in 19 of 62 (31%) participants but did not specify what the adverse events were or their distribution between the active treatment and placebo groups.28 Three of the other four trials reported pain in most participants.12,22,35 In two of the five trials, local anaesthetic was used routinely before the injection of bleomycin. One trial reported pain in most participants irrespective of dose.22 In another trial, two of 24 participants receiving bleomycin withdrew either because of the pain of the injections or because of pain after the injections.12

Fluorouracil and intralesional interferons

As treatments for ordinary warts, fluorouracil and intralesional interferons are more of historical interest, with most of the trials reviewed from the 1970s and '80s. Evidence provided by all the trials was limited by the heterogeneity of the methods and design. Overall, neither treatment was strikingly effective.

Photodynamic therapy

Four trials reported varying success with different types of photodynamic therapy.39,42,43,46 The heterogeneity in methods and variations in trial quality made it impossible to draw firm conclusions. One well designed trial in 40 adults reported cure in 56% of warts treated with aminolaevulinic acid photodynamic therapy compared with 42% treated by placebo photodynamic therapy.43 Topical salicylic acid was also used for all participants.

Two trials provided no data on adverse effects. In one trial, burning and itching during treatment and mild discomfort afterwards was reported universally with aminolaevulinic acid photodynamic therapy.42 All participants with plantar warts were able to walk after treatment. In another study severe or unbearable pain during treatment was reported in about 17% of warts with active treatment and about 4% of with placebo photodynamic therapy.43

Factors contributing to heterogeneity of wart trials

Factors related to participants

Age: spontaneous and therapeutic cure rates are probably higher in children than in adults

Site of lesions: plantar warts tend to be more resistant to treatment than warts at other sites

Type of lesion: mosaic plantar warts differ in response to treatment from simple plantar warts as do plane warts from common warts

Length of history and previous treatment: longstanding warts that have not cleared with previous treatments are likely to be the result of a suboptimal immune response to human papillomavirus

Trial populations: trials conducted in hospital clinics dealing with warts are likely to have had very different proportions of incident and refractory warts depending on referral patterns at the time of the trial

Factors related to treatment

Topical treatments: different concentrations, formulations, and methods of application of salicylic acid and other topical agents

Cryotherapy: different delivery systems, methods, regimens, and interpretations of techniques for giving cryotherapy

Intralesional treatments: different concentrations, vehicles, intervals between treatments, and numbers of injections

Follow up period: different periods of treatment and different periods before assessment of outcome

Other treatments

One trial of 40 patients treated by pulsed dye laser showed no significant difference in cure rates between four treatments at monthly intervals and “conventional” treatment with either cryotherapy or cantharidin, a potent irritant.33

Six trials of more obscure local treatments (two trials of ultrasonography, one of silver nitrate, one of topical thuja, one of 0.05% tretinoin cream, and one of heat) were not included in the review.49

No randomised trials were identified that studied the efficacy of carbon dioxide laser, surgical excision, curettage or cautery, formaldehyde, podophyllin, or podophyllotoxin.

Discussion

Most of the trials reviewed concerning local treatment for cutaneous warts were of low quality. We had difficulty reviewing the research systematically because of the heterogeneity of study design, methods, and outcome. This hindered the pooling of data.

A large number of important variables distinguished these trials from one another (box). Some used subgroup analysis to allow for these variables (for example, warts on the hands or feet). Others excluded particular subgroups such as mosaic plantar warts or participants with multiple warts. Few trials made a distinction between plane warts and common warts.

In view of this heterogeneity and the low quality of most of the trials, the descriptive synthesis and pooled data in our review should be interpreted with caution.

Implications for practice

A dearth of high quality evidence prevents the rational use of treatments for common warts. Simple topical treatments containing salicylic acid seem to be both effective and safe. No clear evidence was found that any of the other treatments have a particular advantage of either higher cure rates or fewer adverse effects.

Although it is widely believed that cryotherapy may succeed when topical salicylic acid has failed, there was no clear evidence to support this. Indeed some evidence shows that at best cryotherapy is only equal in efficacy to topical salicylic acid.

Intralesional bleomycin is a popular third line treatment with some dermatologists, but evidence for its efficacy is limited. Topical immunotherapy with agents such as dinitrochlorobenzene is best confined to specialist centres at present in view of its adverse effects. Photodynamic therapy and the use of pulsed dye lasers may hold promise for the future.

Table.

Details of included trials

| Reference

|

Setting, design*

|

No of participants randomised (dropouts or withdrawals), age, type† and site of warts

|

Interventions

|

Outcomes

|

Notes

|

Quality

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salicylic acid | ||||||

| Abou-Auda et al 19874 | Primary care, multicentre, blind | ?100 (46) (54 analysed), adults and children, ordinary, hands and feet | 15% salicylic acid patch v placebo patch | Successful treatment in 27/31 (87%) v 11/23 (48%) at 12 weeks | Successful treatment rather than cure as end point. Number of withdrawals and dropouts not clear | Low |

| Auken et al 19756 | ?Secondary care, multicentre, blind | 240 (55), adults and children, not stated, hands and feet | Lactic acid and salicylic acid v “conventional” (anything else or no treatment) | Cure in 43/84 (51%) v 54/101 (54%) at 3 months | Low | |

| Bart et al 19897 | Secondary care, blind | 61 (8), adults, ordinary hands only |

Salicylic acid patch v placebo patch | Cure in 19/28 (68%) v 7/25 (28%) at 12 weeks | Low | |

| Bunney et al 197114 | Secondary care, blind | 382 (86), adults and children, not stated, feet only | Salicylic acid and lactic acid v collodion v callusolve‡v 50% podophyllin | Cure in 64/76 (84%), 50/76 (66%), 47/70 (67%), and 60/74 (81%) at 12 weeks | Lower cure rates for mosaic plantar v simple plantar warts with all treatments, 58% v 75% | Low |

| Bunney et al 197613 | Secondary care, blind | 156 (18), adults and children, not stated, feet (simple plantar) | Salicylic acid and lactic acid v salicylic acid and lactic acid plus polyoxyethylene | Cure in 55/71 (77%) v 50/67 (75%) at 12 weeks | Low | |

| Bunney et al 197613 | Secondary care, blind | 94 (13), adults and children, not stated, feet (mosaic plantar) | 10% glutaraldehyde v salicylic acid and lactic acid | Cure in 18/38 (47%) v 19/43 (44%) at 12 weeks | Low | |

| Bunney et al 197613 | Secondary care, blind | 110 (17), adults and children, not stated, feet (mosaic plantar) | 40% salicylic acid v salicylic acid and lactic acid | Cure in 15/50 (30%) v 17/43 (40%) at 12 weeks | Low | |

| Felt et al 199818 | Secondary care, open | 61 (10), children, ordinary, anywhere | Relaxation imagery v salicylic acid v no treatment | Cure in 7/14 (50%), 10/17 (59%), and 5/20 (25%) at 6-18 months | Only one index wart treated in each child | Low |

| Flindt-Hansen et al 198419 | Secondary care, open | 72 (14), adults and children, not stated, hands and feet | Anthralin v lactic acid and salicylic acid | Cure in 15/27 (56%) v 8/31 (26%) at 2 months | Low | |

| Parton and Sommerville 199430 | Primary care, open | 49 (0), children, ordinary, feet | Abrasion v salicylic acid | Mean time to cure of 2.1 weeks (2-4) v 18.2 weeks (8-38). Itching in 93% of abrasion group | Brief report. 100% cure rate implied by text | Medium |

| Spanos et al 199038 | Secondary care, blind | 40 (0), adults, not stated, hands and feet | Hypnosis v salicylic acid v placebo v nil | “Loss of warts” in 6/10 (60%), 0/10 (0%), 1/10 (10%), and 3/10 (30%) at 6 weeks | Medium | |

| Steele et al 198841 | Primary care, blind | 57 (0), adults and children, ordinary, feet (simple plantar) | Monochloroacetic acid crystals and 60% salicylic acid v placebo | Cure in 19/29 (66%) v 5/28 (18%) at 6 weeks, cure in 24/29 (83%) v 15/28 (54%) at 6 months | High | |

| Viein et al 199147 | Secondary care, open, intention to treat analysis | 250 (80), adults and children, not stated, feet (simple plantar) | Salicylic acid and lactic acid with occlusion v salicylic acid and lactic acid | Cure in 48% and 47% at 17 weeks | Results expressed as percentages only, higher cure rates in children noted | Low |

| Cryotherapy | ||||||

| Berth-Jones and Hutchinson 199210 | Secondary care, open | 400 (77), adults and children, mixed, hands and feet | 3 weekly cotton wool bud cryotherapy plus salicylic acid and lactic acid with paring v without paring | Cure in 46% v 50% of hands and 75% v 39% of feet at 3 months | Cure rate expressed as percentages only | Low |

| Berth-Jones et al 199210 | Secondary care, open | 155 (40), adults and children, refractory, hands and feet | 3 weekly cotton wool bud cryotherapy plus salicylic acid and lactic acid v no further treatment | Cure in 43% and 38% after a further 3 months | Second part of study above. Oral inosine pranobex also used for some patients, with no apparent benefit | Low |

| Berth-Jones et al 19949 | Secondary care, open, intention to treat analysis | 300 (93), adults and children, mixed, hands and feet | 3 weekly cotton wool bud cryotherapy plus salicylic acid and lactic acid: double v single freeze | Cure in 46/103 (45%) v 41/100 (41%) hands and 33/66 (50%) v 16/55 (29%) feet at 3 months | Low | |

| Bourke et al 199511 | Secondary care, open, intention to treat analysis | 245 (143), adults and children, mixed, hands and feet | Cotton wool bud cryotherapy plus salicylic acid and lactic acid: 1 v 2 v 3 weekly intervals between freezes | 43%, 48%, and 44% cured after 12 treatments. Faster cure with more frequent treatments | High attrition rate and cure rates only given as percentages | Low |

| Bunney et al 197613 | Secondary care, open | 100 (28), adults and children, not stated, hands only | Cotton wool bud cryotherapy: 2 v 3 v 4 weekly intervals between freezes | Cure in 18/34 (53%), 18/31 (58%), and 10/35 (29%) at 12 weeks (with intention to treat analysis). 87%, 78%, and 64% cured after 6 treatments | Low | |

| Bunney et al 197613 | Secondary care, open | 389 (95), adults and children, not stated, hands only | 3 weekly cotton wool bud cryotherapy v salicylic acid and lactic acid v both | Cure in 68/99 (69%), 64/95 (67%), and 78/100 (78%) at 12 weeks | Low | |

| Connolly et al 200116 | Secondary care, open | 200 (54), adults and children, not stated, hands and feet | Cryogun or cryospray: 10 second freeze v “gentle” freeze | Cure in 42/71 (59%) v 25/75 (33%) at 8 weeks | Low | |

Continued on next page

Table.

Details of included trials—continued

| Reference

|

Setting, design*

|

No of participants randomised (dropouts or withdrawals), age, type† and site of warts

|

Interventions

|

Outcomes

|

Notes

|

Quality

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erkens et al 199217 | Primary care, open, intention to treat analysis | 93 (18), adults and children, ordinary, hands only | Monthly cotton wool bud cryotherapy v bimonthly histofreezer | Cure in 25/43 (58%) v 14/50 (28%) at 2.5 months | Medium | |

| Gibson et al 198420 | Secondary care, blind (creams) | 52 (5), adults and children, not stated, feet only | Topical aciclovir v placebo cream v 2 weekly cryogun or cryospray plus glutarol | Cure in 7/18 (39%), 5/18 (28%),and 1/11 (9%) at 8 weeks | Low | |

| Hansen and Schmidt 198621 | Primary care, open, intention to treat analsysis | 77 (17), adults and children, ordinary, feet only | Cryoprobe: 2 minutes v 15 seconds | Cure in 24/33 (73%) v 7/27 (26%) at 9 weeks | Low | |

| Larsen and Laurberg 199624 | Secondary care, multicentre, open, intention to treat analysis | 185 (41), adults and children, ordinary hands only |

Cotton wool bud cryotherapy: 2 v 3 v 4 weekly intervals between freezes | Cure in 31/49 (63%), 32/46 (70%), and 31/49 (63%) at 6 months | Study done on one index wart per patient only | Low |

| Marroquin et al 199726 | Primary care, open, within patient study | 30 (?), adults and children, not stated, hands and feet | Jatropha sap v cryotherapy (×1 only) v petrolatum | 100%, 84.7%, and 0% of warts cured at 30 days | Warts used as unit of analysis; only three warts treated per patient | Low |

| Martinez et al 199627 | Primary care, open | 124 (3), adults and children, ordinary, anywhere | Dimethyl ether propane v cotton wool bud cryotherapy | Cure in 65/68 (96%) v 80/86 (93%) 15 days after last treatment | Warts used as unit of analysis | Low |

| Sonnex and Camp 198837 | Secondary care, open | 31 (0), adults, refractory, hands and feet | Cryogun or cryospray: aggressive (with local anaesthetic) v standard cryotherapy | Cure in 11/16 (69%) v 0/16 (0%) hands and 3/15 (20%) v 0/15 (0%) feet at 4 weeks | Published as abstract only | Low |

| Steele and Irwin 198840 | Primary care, open | 207 (18), adults and children, ordinary, hands and feet | Weekly cotton wool bud cryotherapy v salicylic acid and lactic acid v both | Cure in 24/40 (60%), 23/38 (61%), and 33/38 (87%) hands and 15/26 (58%), 9/22 (41%), and 14/25 (56%) feet at 6 months | Multiple and mosaic warts excluded | Low |

| Intralesional bleomycin | ||||||

| Bunney et al 198412 | Secondary care, blind, left and right comparison study | 24 (0), adults, refractory, hands only | 0.1% bleomycin v saline ×2 if necessary | Cure in 34/59 (58%) v 6/59 (10%) of warts at 6 weeks | Warts used as unit of analysis. Patients switched to active treatment after 6 weeks | Medium |

| Hayes and O'Keefe 198622 | Secondary care, blind | 26 (?), adults, refractory, hands only | Bleomycin: 0.25 v 0.5 v 1.0 U per wart up to 3× at 3 weekly intervals | Cure in 11/15 (73%), 21/24 (88%), and 9/10 (90%) of warts at 3 months | Warts used as unit of analysis. Number of dropouts not clear | Low |

| Munkvad et al 198328 | Secondary care, blind | 62 (?), adults, not stated, hands and feet | 1% bleomycin in saline v in oil v saline alone v oil alone using dermajet | Cure in 4/22 (18%), 5/36 (14%), 8/19 (42%), and 10/22 (45%) of warts at 3 months | Warts used as unit of analysis | Low |

| Perez et al 199232 | Secondary care, blind | 37 (6), adults and children, not stated, hands and feet | 0.1% bleomycin v saline ×2 if necessary | Cure in 15/16 (94%) v 11/15 ( 73%) at 30 days | Low | |

| Rossi et al 198135 | Secondary care, blind | 16 (0), adults and children, refractory, anywhere | Bleomycin 0.1% v saline placebo ×1 | Cure in 31/38 (82%) v 16/46 (35%) of warts at 1 month | Warts used as unit of analysis | Low |

| Fluorouracil | ||||||

| Artese et al 19945 | Secondary care, open, intention to treat analysis | 300 (6), adults and children, ordinary, hands and feet | Fluorouracil plus salicylic acid and lactic acid v cautery | Cure in 127/150 (85%) v 99/150 (66%) at 75 days | Low | |

| Bunney 197315 | Secondary care, blinding unclear | 95 analysed, not stated, not stated, feet (mosaic) | 2% fluorouracil v 5% fluorouracil v salicylic acid and lactic acid v 5% idoxuridine | Cure in 13/28 (46%), 8/15 (53%), 8/16 (50%), and 9/36 (25%) at 12 weeks | Low | |

| Hursthouse 197523 | Secondary care, blind, left and right comparison study | 66 (2), adults and children, not stated, hands and feet | 5% fluorouracil cream v placebo | Cure in 29/64 (45%) v 8/64 (13%) at 4 weeks | Medium | |

| Schmidt and Jacobsen 198136 | Secondary care, blind | 60 (5), adults, not stated, hands and feet | Fluorouracil and salicylic acid v vehicle alone | Cure in 13/28 (46%) v 5/27 (19%) | Low | |

| Intralesional interferons | ||||||

| Berman et al 19868 | Secondary care, blind | 8 (0), adults, refractory, not stated | Interferon alfa (0.1 ml of 1 million U/ml) v placebo | Cure in 2/4 (50%) v 1/4 (25%) at 8 weeks | Low | |

| Lee et al 199025 | Secondary care, blind, left and right comparison study | 74 (?), adults and children, refractory, hands and feet | Interferon gamma: high dose (5 million U/ml) v low dose (1 million U/ml) v placebo | Cure in 20/36 (56%) v 16/53 (30%) v 3/36 (17%) at 4 weeks | Low | |

| Niimura 199029 | Secondary care, blind, left and right comparison study | 80 (16), adults and children, not stated, hands and feet | Interferon beta (0.1 ml of 1 million U/ml weekly) v placebo | Cure in 42/64 (66%) v 7/64 (11%) at 10 weeks | Low | |

| Pazin et al 198231 | Secondary care, blind | 1 (0), adult, refractory, hands and feet | Interferon alfa v placebo (various regimens and doses) | Cure in 5/12 (42%) v 0/4 (0%) of warts at 15.5 weeks | Low | |

| Vance et al 198644 | Secondary care, multicentre, blind | 111 (11), adults, not stated, feet only | Interferon alfa: high dose (10 million U/ml) v low dose (1 million U/ml) v placebo | Cure in 4/30 (30%) v 7/32 (22%) v 8/38 (21%) at 12 weeks | Medium | |

Continued on next page

Table.

Details of included trials—continued

| Reference

|

Setting, design*

|

No of participants randomised (dropouts or withdrawals), age, type† and site of warts

|

Interventions

|

Outcomes

|

Notes

|

Quality

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Varnavides et al 199745 | Secondary care, blind | 51 (9), adults, refractory, hands and feet | Interferon alfa (10 IU/ml weekly ×12) v placebo | Cure in 12/23 (52%) v 12/19 (63%) at 24 weeks | Medium | |

| Dinitrochlorobenzene | ||||||

| Rosado-Cancino et al 198934 | Secondary care, open | 40 (0), children, refractory, anywhere | Dinitrochlorobenzene v placebo | Cure in 16/20 (80%) v 7/20 (35%) | Duration of trial unclear | Low |

| Wilson 198348 | Secondary care, open | 60 (0), adults, ordinary, hands only | Dinitrochlorobenzene v cryotherapy v no treatment | Cure in 16/20 (80%), 10/20 (50%), and 8/20 (40%) at 4 months | Published as abstract only | Low |

| Photodynamic therapy | ||||||

| Stahl et al 197939 | Secondary care, open | 149 (29), adults and children, ordinary, hands and feet | Methylene blue and dimethyl sulphoxide v salicylic acid and creosote | Cure in 5/65 (8%) v 8/56 (15%) at 8 weeks | Low | |

| Stender et al 199942 | Secondary care, blind, intention to treat analysis, within patient | 30 (2), adults, refractory, hands and feet | White (×3 and ×1), red (×3), and blue (×3) light v cryotherapy (×4) | Cure in 73%, 71%, 42%, 28%, and 20% of warts at 4-6 weeks | Warts used as unit of analysis, results in % only, no placebo groups, and salicylic acid used in all groups | Medium |

| Stender et al 200043 | Secondary care, blind, intention to treat analysis, within patient | 45 (5), adults, refractory, hands and feet | 20% aminolaevulinic acid and red light v placebo photodynamic therapy | Cure in 64/114 (56%) v 47/113 (42%) of warts at 18 weeks | High | |

| Viein et al 197746 | Secondary care, blind, left and right comparison study | 56 (6), adults and children, refractory, hands and feet | Proflavine and dimethyl sulphoxide or neutral red and dimethyl sulphoxide v placebo photodynamic therapy (×8) | Cure in 10/27 (37%) proflavine v 10/23 (43%) neutral red at 8 weeks | Placebo half cured in all responders and no placebo response in all non-responders | Medium |

| Pulsed dye laser | ||||||

| Robson et al 200033 | Secondary care, open | 40 (5), adults, not stated, any site | Monthly pulsed dye laser (up to ×4) v “conventional” treatment | Cure in 66% v 70% of warts | Warts used as unit of analysis and cure rates expressed as percentages only | Low |

All studies except left and right comparison studies and within patient design were parallel group randomised controlled trials. ?=not clear. Cryotherapy is with liquid nitrogen.

Blinding refers to assessment of outcome only and not blinding of participants

Refractory broadly defined as warts that did not respond to previous treatments.

Callusolve contains a quarternary ammonium germicide.

Footnotes

Funding: Norfolk Health Authority provided funding for the translation of some trials.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Sterling J, Kurtz JB. Viral infections. In: Champion RH, Burton JL, Burns DA, Breathnach SM, editors. Rook textbook of dermatology. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clarke M, Oxman AD. Cochrane reviewers' handbook 4.1. Oxford: Cochrane Collaboration; 2000. . [Updated Jun 2000.] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Juni P, Witschi A, Block R, Egger M. The hazards of scoring the quality of clinical trials for meta-analysis. JAMA. 1999;282:1054–1060. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.11.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abou-Auda H, Soutor C, Neveaux JL. Treatment of verruca infections (warts) with a new transcutaneous controlled release system. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 1987;41:552–556. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Artese O, Cazzato C, Cucchiarelli S, Iezzi D, Palazzi P, Ametetti M. Controlled study: medical therapy (5-fluouracil, salicylic acid) vs physical therapy (DTC) of warts. Dermatol Clinics. 1994;14:55–59. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Auken G, Gade M, Pilgaard CE. [Treatment of warts of the hands and feet with Verucid] Ugeskrift for Laeger. 1975;137:3036–3038. . [In Danish.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bart BJ, Biglow J, Vance JC, Neveaux JL. Salicylic acid in karaya gum patch as a treatment for verruca vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:74–76. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(89)70010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berman B, Davis-Reed L, Silverstein L, Jaliman D, France D, Lebwohl M. Treatment of verrucae vulgaris with alpha 2 interferon. J Infect Dis. 1986;154:328–330. doi: 10.1093/infdis/154.2.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berth-Jones J, Bourke J, Eglitis H, Harper C, Kirk P, Pavord S, et al. Value of a second freeze-thaw cycle in cryotherapy of common warts. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:883–886. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb08594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berth-Jones J, Hutchinson PE. Modern treatment of warts: cure rates at 3 and 6 months. Br J Dermatol. 1992;127:262–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1992.tb00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bourke JF, Berth-Jones J, Hutchinson PE. Cryotherapy of common viral warts at intervals of 1, 2 and 3 weeks. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:433–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb08678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bunney MH, Nolan MW, Buxton PK, Going SM, Prescott RJ. The treatment of resistant warts with intralesional bleomycin: a controlled clinical trial. Br J Dermatol. 1984;111:197–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1984.tb04044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bunney MH, Nolan MW, Williams DA. An assessment of methods of treating viral warts by comparative treatment trials based on a standard design. Br J Dermatol. 1976;94:667–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1976.tb05167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bunney MH, Hunter JA, Ogilvie MM, Williams DA. The treatment of plantar warts in the home. A critical appraisal of a new preparation. Practitioner. 1971;207:197–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bunney MH. The treatment of plantar warts with 5-fluorouracil. Br J Dermatol. 1973;89:96–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1973.tb01926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Connolly M, Basmi K, O'Connell M, Lyons JF, Bourke JF. Cryotherapy of warts: a sustained 10-s freeze is more effective than the traditional method. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:554–557. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erkens AMJL, Kuijpers RJAM, Knottnerus JA. Treatment of verrucae vulgares in general practice—a randomized controlled trial on the effectiveness of liquid nitrogen and the Histofreezer. J Dermatol Treatment. 1992;3:193–196. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Felt BT, Hall H, Olness K, Schmidt W, Kohen D, Berman BD, et al. Wart regression in children: comparison of relaxation imagery to topical treatment and equal time interventions. Am J Clin Hypnosis. 1998;41:130–137. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flindt-Hansen H, Tikjob G, Brandrup F. Wart treatment with anthralin. Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 1984;64:177–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gibson JR, Harvey SG, Barth J, Darley CR, Reshad H, Burke CA. A comparison of acyclovir cream versus placebo cream versus liquid nitrogen in the treatment of viral plantar warts. Dermatologica. 1984;168:178–181. doi: 10.1159/000249695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hansen JG, Schmidt H. [Plantar warts. Occurrence and cryosurgical treatment] Ugeskrift for Laeger. 1986;148:173–174. . [In Danish.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayes ME, O'Keefe EJ. Reduced dose of bleomycin in the treatment of recalcitrant warts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:1002–1006. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(86)70264-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hursthouse MW. A controlled trial on the use of topical 5-fluorouracil on viral warts. Br J Dermatol. 1975;92:93–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1975.tb03039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larsen PO, Laurberg G. Cryotherapy of viral warts. J Dermatol Treatment. 1996;7:29–31. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee SW, Houh D, Kim HO, Kim CW, Kim TY. Clinical trials of interferon-gamma in treating warts. Ann Dermatol. 1990;2:77–82. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marroquin EA, Blanco JA, Granados S, Caceres A, Morales C. Clinical trial of Jatropha curcas sap in the treatment of common warts. Fitoterapia. 1997;68:160–162. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez FC, Nohales CP, Canal CP, Martin MJ, Catalan MH, Canadas YG. Cutaneous cryosurgery in family medicine: dimethyl ether propane spray versus liquid nitrogen. Atencion Primaria. 1996;18:211–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Munkvad M, Genner J, Staberg B, Kongsholm H. Locally injected bleomycin in the treatment of warts. Dermatologica. 1983;167:86–89. doi: 10.1159/000249753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niimura M. Application of beta-interferon in virus-induced papillomas. J Invest Dermatol. 1990;95:149–51S. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12875129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parton AM, Sommerville RG. The treatment of plantar verrucae by triggering cell-mediated immunity. Br J Pod Med. 1994;131:883–886. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pazin GJ, Ho M, Haverkos HW, Armstrong JA, Breinig MC, Wechsler HL, et al. Effects of interferon-alpha on human warts. J Interferon Res. 1982;2:235–243. doi: 10.1089/jir.1982.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perez Alfonzo R, Weiss E, Piquero Martin J. Hypertonic saline solution vs intralesional bleomycin in the treatment of common warts. Dermatol Venez. 1992;30:176–178. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robson KJ, Cunningham NM, Kruzan KL. Pulsed dye laser versus conventional therapy for the treatment of warts: a prospective randomized trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:275–280. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2000.106365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosado-Cancino MA, Ruiz-Maldonado R, Tamayo L, Laterza AM. Treatment of multiple and stubborn warts in children with 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (DNCB) and placebo. Dermatol Rev Mex. 1989;33:245–252. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rossi E, Soto JH, Battan J, Villalba L. Intralesional bleomycin in verruca vulgaris. Double-blind study. Dermatol Rev Mex. 1981;25:158–165. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmidt H, Jacobsen FK. Double-blind randomized clinical study on treatment of warts with fluouracil-containing topical preparation. Z Hautkr. 1981;56:41–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sonnex TS, Camp RDR. The treatment of recalcitrant viral warts with high dose cryosurgery under local anaesthesia (abstract) Br J Dermatol. 1988;119(suppl 33):38–39. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spanos NP, Williams V, Gwynn MI. Effects of hypnotic, placebo, and salicylic acid treatments on wart regression. Psychosom Med. 1990;52:109–114. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199001000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stahl D, Veien NK, Wulf HC. Photodynamic inactivation of virus warts: a controlled clinical trial. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1979;4:81–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1979.tb01594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steele K, Irwin WG. Liquid nitrogen and salicylic/lactic acid paint in the treatment of cutaneous warts in general practice. J Roy Coll Gen Pract. 1988;38:256–258. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steele K, Shirodaria P, O'Hare M, Merrett JD, Irwin WG, Simpson DI, et al. Monochloroacetic acid and 60% salicylic acid as a treatment for simple plantar warts: effectiveness and mode of action. Br J Dermatol. 1988;118:537–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1988.tb02464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stender IM, Lock-Anderson J, Wulf HC. Recalcitrant hand and foot warts successfully treated with photodynamic therapy with topical 5-aminolaevulinic acid: a pilot study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1999;24:154–159. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.1999.00441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stender IM, Na R, Fogh H, Gluud C, Wulf HC. Photodynamic therapy with 5-aminolaevulinic acid or placebo for recalcitrant foot and hand warts: randomised double-blind trial. Lancet. 2000;355:963–966. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)90013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vance JC, Bart BJ, Hansen RC, Reichman RC, McEwen C, Hatch KD, et al. Intralesional recombinant alpha-2 interferon for the treatment of patients with condyloma acuminatum or verruca plantaris. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:272–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Varnavides CK, Henderson CA, Cunliffe WJ. Intralesional interferon: ineffective in common viral warts. J Dermatol Treatment. 1997;8:169–172. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Veien NK, Genner J, Brodthagen H, Wettermark G. Photodynamic inactivation of verrucae vulgares. II. Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 1977;57:445–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Veien NK, Madsen SM, Avrach W, Hammershoy O, Lindskov R, Niordson A-MMSD. The treatment of plantar warts with a keratolytic agent and occlusion. J Dermatol Treatment. 1991;2:59–61. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilson P. Immunotherapy v cryotherapy for hand warts; a controlled trial (abstract) Scottish Med J. 1983;28(2):191. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gibbs S, Harvey I, Sterling J, Stark R. Cochrane Library. Issue 2. Oxford: Update Software; 2001. Local treatments for cutaneous warts. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]