Abstract

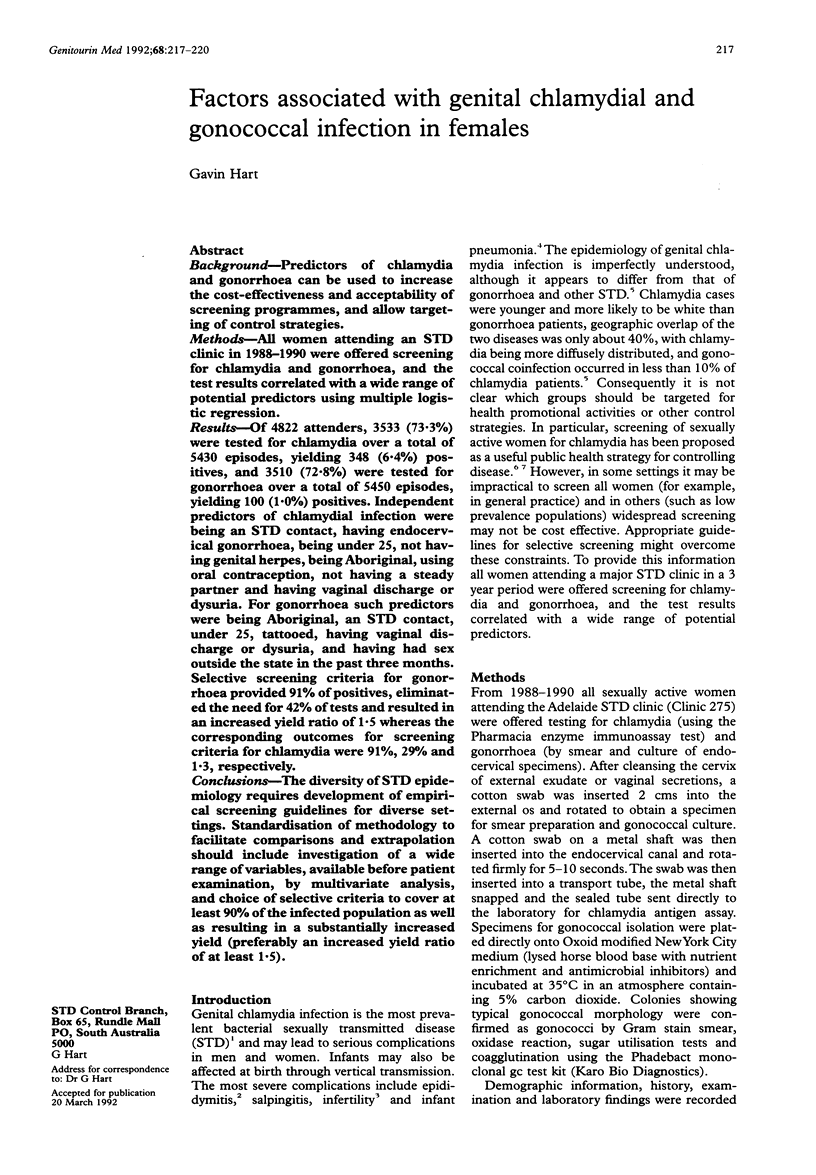

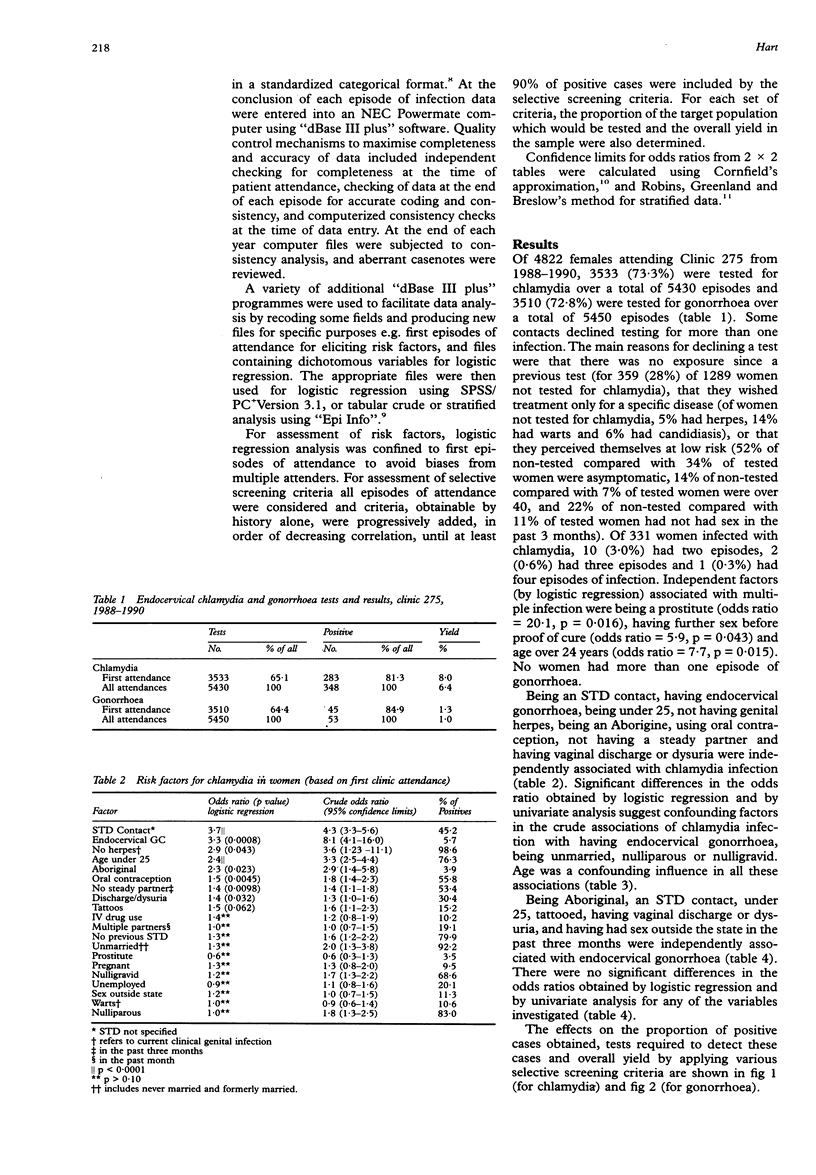

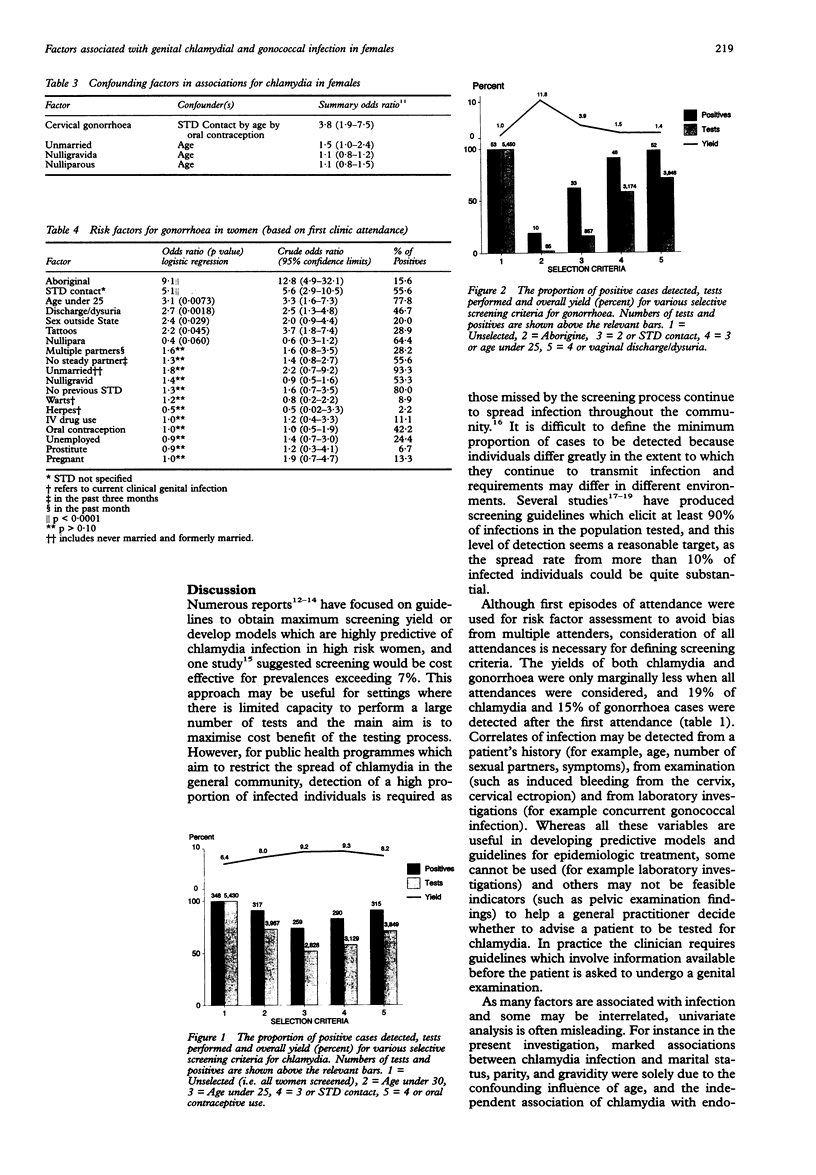

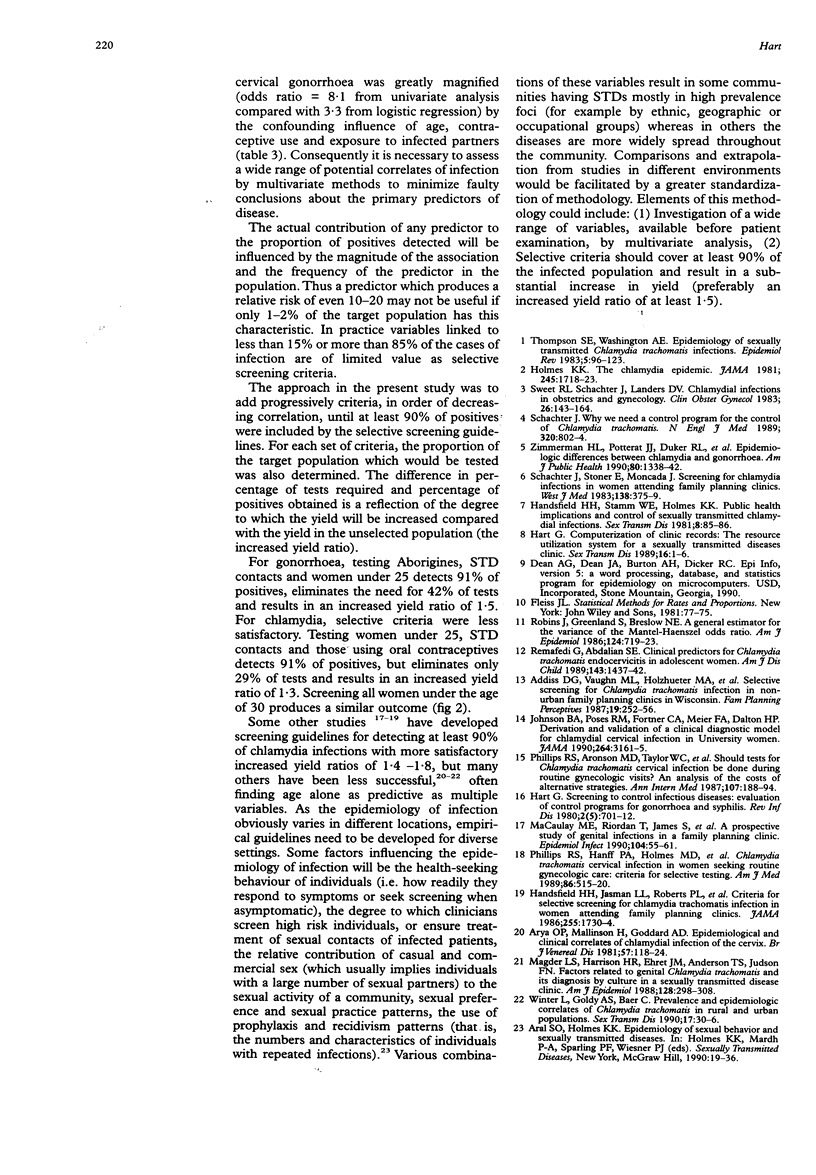

BACKGROUND--Predictors of chlamydia and gonorrhoea can be used to increase the cost-effectiveness and acceptability of screening programmes, and allow targeting of control strategies. METHODS--All women attending an STD clinic in 1988-1990 were offered screening for chlamydia and gonorrhoea, and the test results correlated with a wide range of potential predictors using multiple logistic regression. RESULTS--Of 4822 attenders, 3533 (73.3%) were tested for chlamydia over a total of 5430 episodes, yielding 348 (6.4%) positives, and 3510 (72.8%) were tested for gonorrhoea over a total of 5450 episodes, yielding 100 (1.0%) positives. Independent predictors of chlamydial infection were being an STD contact, having endocervical gonorrhoea, being under 25, not having genital herpes, being Aboriginal, using oral contraception, not having a steady partner and having vaginal discharge or dysuria. For gonorrhoea such predictors were being Aboriginal, an STD contact, under 25, tattooed, having vaginal discharge or dysuria, and having had sex outside the state in the past three months. Selective screening criteria for gonorrhoea provided 91% of positives, eliminated the need for 42% of tests and resulted in an increased yield ratio of 1.5 whereas the corresponding outcomes for screening criteria for chlamydia were 91%, 29% and 1.3, respectively. CONCLUSIONS--The diversity of STD epidemiology requires development of empirical screening guidelines for diverse settings. Standardisation of methodology to facilitate comparisons and extrapolation should include investigation of a wide range of variables, available before patient examination, by multivariate analysis, and choice of selective criteria to cover at least 90% of the infected population as well as resulting in a substantially increased yield (preferably an increased yield ratio of at least 1.5).

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Addiss D. G., Vaughn M. L., Holzhueter M. A., Bakken L. L., Davis J. P. Selective screening for Chlamydia trachomatis infection in nonurban family planning clinics in Wisconsin. Fam Plann Perspect. 1987 Nov-Dec;19(6):252–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arya O. P., Mallinson H., Goddard A. D. Epidemiological and clinical correlates of chlamydial infection of the cervix. Br J Vener Dis. 1981 Apr;57(2):118–124. doi: 10.1136/sti.57.2.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handsfield H. H., Jasman L. L., Roberts P. L., Hanson V. W., Kothenbeutel R. L., Stamm W. E. Criteria for selective screening for Chlamydia trachomatis infection in women attending family planning clinics. JAMA. 1986 Apr 4;255(13):1730–1734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handsfield H. H., Stamm W. E., Holmes K. K. Public health implications and control of sexually transmitted chlamydial infections. Sex Transm Dis. 1981 Apr-Jun;8(2):85–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart G. Computerization of clinic records: the resource utilization system for a sexually transmitted diseases clinic. Sex Transm Dis. 1989 Jan-Mar;16(1):1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart G. Screening to control infectious diseases: evaluation of control programs for gonorrhea and syphilis. Rev Infect Dis. 1980 Sep-Oct;2(5):701–712. doi: 10.1093/clinids/2.5.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes K. K. The Chlamydia epidemic. JAMA. 1981 May 1;245(17):1718–1723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B. A., Poses R. M., Fortner C. A., Meier F. A., Dalton H. P. Derivation and validation of a clinical diagnostic model for chlamydial cervical infection in university women. JAMA. 1990 Dec 26;264(24):3161–3165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macaulay M. E., Riordan T., James J. M., Leventhall P. A., Morris E. M., Neal B. R., Ellis D. A. A prospective study of genital infections in a family-planning clinic. 2. Chlamydia infection--the identification of a high-risk group. Epidemiol Infect. 1990 Feb;104(1):55–61. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800054522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magder L. S., Harrison H. R., Ehret J. M., Anderson T. S., Judson F. N. Factors related to genital Chlamydia trachomatis and its diagnosis by culture in a sexually transmitted disease clinic. Am J Epidemiol. 1988 Aug;128(2):298–308. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips R. S., Aronson M. D., Taylor W. C., Safran C. Should tests for Chlamydia trachomatis cervical infection be done during routine gynecologic visits? An analysis of the costs of alternative strategies. Ann Intern Med. 1987 Aug;107(2):188–194. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-107-2-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips R. S., Hanff P. A., Holmes M. D., Wertheimer A., Aronson M. D. Chlamydia trachomatis cervical infection in women seeking routine gynecologic care: criteria for selective testing. Am J Med. 1989 May;86(5):515–520. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(89)90377-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remafedi G., Abdalian S. E. Clinical predictors of Chlamydia trachomatis endocervicitis in adolescent women. Looking for the right combination. Am J Dis Child. 1989 Dec;143(12):1437–1442. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1989.02150240059017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins J., Greenland S., Breslow N. E. A general estimator for the variance of the Mantel-Haenszel odds ratio. Am J Epidemiol. 1986 Nov;124(5):719–723. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachter J., Stoner E., Moncada J. Screening for chlamydial infections in women attending family planning clinics. West J Med. 1983 Mar;138(3):375–379. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachter J. Why we need a program for the control of Chlamydia trachomatis. N Engl J Med. 1989 Mar 23;320(12):802–804. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198903233201210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet R. L., Schachter J., Landers D. V. Chlamydial infections in obstetrics and gynecology. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1983 Mar;26(1):143–164. doi: 10.1097/00003081-198303000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson S. E., Washington A. E. Epidemiology of sexually transmitted Chlamydia trachomatis infections. Epidemiol Rev. 1983;5:96–123. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter L., Goldy A. S., Baer C. Prevalence and epidemiologic correlates of Chlamydia trachomatis in rural and urban populations. Sex Transm Dis. 1990 Jan-Mar;17(1):30–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman H. L., Potterat J. J., Dukes R. L., Muth J. B., Zimmerman H. P., Fogle J. S., Pratts C. I. Epidemiologic differences between chlamydia and gonorrhea. Am J Public Health. 1990 Nov;80(11):1338–1342. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.11.1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]