Abstract

Background

An accurate calculation of energy expenditure (REE) is necessary for estimating energy needs in malign prostate cancer. The purpose of this research was to evaluate the accuracy of the established novel equation for predicting REE in malign and benign prostate patients versus the accuracy of the previously used predictive equations based on REE measured by indirect calorimetry.

Methods

The study was conducted as a cross-sectional case-control study and between December 2020 and May 2021 with 40 individuals over the age of 40 who applied to the Urology Clinic of Gazi University Faculty of Medicine. Subjects with 41 malign prostate and 42 benign prostate patients were both over the age of 40 (65.3 ± 6.30 years) and recruited for the study. Cosmed-FitMate GS Indirect Calorimetry with Canopyhood (Rome, Italy) was used to measure REE. A full body composition analysis and anthropometric measurements were taken. Clinical trial number: Not applicable.

Results

Malign prostate group PSA Total and measured REE values (4.93 ± 5.44 ng/ml, 1722.9 ± 272.69 kcal/d, respectively) were statistically significantly higher than benign group (1.76 ± 0.73 ng/ml, 1670.5 ± 266.76 kcal/d, respectively) (p = 0.022). Malign prostate group (MPG) and benign prostate group (BPG) have the highest percentage of the accurate prediction value of Eq. 80.9% (novel equation MPG) and 64.2% (novel equation BPG). The bias of the equations varied from − 36.5% (Barcellos II Equation) to 19.2% (Mifflin-St. Jeor equation) for the malign prostate group and varied from − 41.1% (Barcellos II Equation) to 17.7% (Mifflin-St. Jeor equation) in the benign prostate group. The smallest root mean squared error (RMSE) values in the malign and benign prostate groups were novel equation MPG (149 kcal/d) and novel equation BPG (202 kcal/d). The new specific equation for malign prostate cancer: REE = 3192,258+ (208,326* body weight (WT)) - (20,285* height (HT)) - (187,549* fat free mass (FFM)) - (203,214* fat mass (FM)) + (4,194* prostate specific antigen total (PSAT)). The new specific equation for the benign prostate group is REE = 615,922+ (13,094*WT). Bland-Altman plots reveal an equally random distribution of novel equations in the malign and benign prostate groups.

Conclusions

Previously established prediction equations for REE may be inconsistent. Utilising the PSAT parameter, we formulated novel energy prediction equations specific to prostate cancer. In any case, the novel predictive equations enable clinicians to estimate REE in people with malign and benign prostate groups with sufficient and most acceptable accuracy.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, Resting energy expenditure, Indirect calorimetry, Novel predictive equations

Background

An increased risk of prostate cancer is discussed in relation to an excessive energy intake in comparison to energy expenditure [1]. Total energy expenditure is defined as the sum of all energy consumed by an organism over the course of a day [2] The majority of energy needs are met by basal/resting metabolic rate (BMR/REE), which accounts for roughly 60–70% of total energy expenditure [3]. Researchers have linked inaccurate estimates of total energy requirements to reduced physical performance and metabolic response, fatigue, increased inflammation, weight loss, malnutrition, and even obesity [4]. Prostate cancer patients may experience metabolic changes that alter their overall energy expenditure depending on the stage and type of the disease. The significance of resting energy expenditure in an individual’s total energy expenditure is increased by the advanced age and declining physical activity of cancer patients [5].

For the patients’ survival and mobilization, it was critical to receive adequate and balanced nutrition tailored to their particular cancer [6]. The accuracy of using predictive equations to estimate the energy requirements of patients with various cancer types may be low due to their fluctuating energy metabolism and metabolic variations [7]. As a result, whenever possible, the primary strategy should be to evaluate each patient individually while measuring energy expenditure via indirect calorimetry. It will be more accurate to plan a unique nutrition therapy program by measuring REE with indirect calorimetry for the patient’s treatment and essential comfort in order to prevent negative energy balance in those with prostate cancer [8]. Since the 1980’s, researchers have developed equations to predict REE across all age groups. Researchers have developed several REE prediction equations for both healthy and clinical use, such as the Harrise-Benedict (1919), Schofield (1985), Iretone Jones (2002), Mifflin-St. Jeor (1990), Barcellos Equation II (2020), Cunningham (1991), Owen (1986), Wang (2000), IOM (2004), Henry (2004), and 21 kcal/kg/d Silver (2013) models. Many studies have evaluated the accuracy of the resting energy expenditure prediction equations in different patient groups [9, 10]. This study discussed the use of previous predictive equations shown in Table 1 in the malign and benign prostate groups. The gold standard for measuring energy expenditure via pulmonary gas exchanges is indirect calorimetry (IC). It’s a non-invasive method that improves clinical outcomes by tailoring nutritional support prescriptions to patients’ individual metabolic requirements [11] Indirect calorimetric methods are more challenging to implement on a large scale due to the higher cost of measurement equipment and the need for trained personnel [12]. Other indirect measuring devices were difficult for cancer patients to use because of their mouthpieces and nasal designs. Portable indirect measurement tools, such as those with a Canopyhood rather than a face mask, are ideal when it comes to comfort and ease of measurement [13]. Indirect calorimetric measurement values were the dependent variable, while demographics (age, gender, ethnicity), anthropometrics (weight, height), and body composition are the independent variables in these equations (adipose tissue, lean tissue). Similar to the regression analysis-based equations, these equations were developed using data collected from the population of healthy people at large to provide fast and easy solutions and he use of predictive equations in REE predictions has become widespread [14].

Table 1.

Predictive equations for REE in malign and benign prostate group used in the present study

| Author and Year | Gender | Age (years) | Predictive Equation for REE | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HarriseBenedict, 1919 | Male | - | kcal/d: 66.4730 + (13.7516WT) + (5.0033 HT) - (6.7550 AGE) | WT: kg, HT: cm, AGE: years |

| Schofield, 1985 | Male | 30–60 | kcal/d: (( 0.048 *WT + 3.653) * 239) | WT: kg, |

| IretoneJones, 2002 | All | - | kcal/d: 1784 - (11 AGE ) + (5 WT) + (244 SEX) + (239T) + (804B) | WT: kg AGE: years SEX: Male:0, Female:1 T: trauma (absence : 0 and presence : 1) B : burnt (absence : 0 and presence : 1) |

| Mifflin-St.Jeor, 1990 | Male | - | kcal/d: (10*WT) + (6.25*HT) – (5*AGE) + 5 | WT: kg, HT: cm, AGE: years |

| Barcellos Equation II, 2020 | All | - | kcal/d: 58(MUAC) + 621.4( SEX ) − 425(O) − 19 | MUAC: mid-upper arm circumference SEX: Male:0, Female:1 O: obesity (0: BMI < 30 and 1: BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2). |

| Cunningham1, 1991 | All | 18–65 | kcal/d: 370 + 21.6*FM | FM: kg |

| Owen, 1986 | Male | 18–65 | kcal/d: 879 + 10.2*WT | WT: kg, |

| Wang, 2000 | All | 18–65 | kcal/d: 24.6*FFM + 175 | FFM: kg |

| IOM, 2004 | Male | - | kcal/d: 293 - (3.8*AGE) + (456.4 *HT) + (10.12*WT) | WT: kg, HT: cm, AGE: years |

|

Henry, 2004 height and weight |

Male |

30–60 > 60 |

kcal/d: Men age 30–60 years: 11.4 × WT + 541 × HT − 137 kcal/d: Men age > 60 years: 11.4 × WT + 541 × HT − 256 |

HT: meters |

| 21 kcal/kg/d Silver, 2013 | All | - | kcal/d: 21 × WT | WT: kg |

WT Weight, HT Height, FM Fat mass

In conclusion researchers developed a number of equations in healthy cancer populations to determine REE for cancer patients. But there was still no agreement on what the best equation was for determining REE for different types of cancer [9, 10, 15]. Some studies examining the accuracy of REE prediction equations have concluded that current equations are not providing valid and accurate predictions in cancer patients [9, 16, 17]. The aim of the present study was to establish a novel REE equation for comparison with previous prediction equations in patients with malign and benign prostate disease using resting energy expenditure (REE) measured with the gold standard indirect calorimetry model (FitMate GS with canopyhood).

Methods

Ethical Standards

The Gazi University Faculty of Medicine Clinical Research Ethics Committee issued decision number 4 on 7 April 2020, approving the study. All patients signed informed consent, and the Declaration of Helsinki guided the conduct of this study.

The study’s design and participants

The study was conducted between December 2020 and May 2021 with 40 individuals over the age of 40 who applied to the Urology Clinic of Gazi University Faculty of Medicine, with new diagnosis malign prostate cancer according to the pathology result and new diagnosis benign prostate prostate cancer in the pathology result. In order to measure REE in individuals with malign and benign prostate cancer by the indirect calorimetry method, compare with REE values estimated by equations and develop the most appropriate equation for this group. The study recruited 83 volunteers aged over 40 (65.3 ± 6.30 years) (41 malign prostate cancer and 42 benign prostate cancer).

The inclusion criteria were being over the age of 40, male, having pathology results indicating either prostate cancer (malign prostate tissue) or benign prostate tissue (without prostate cancer), and not having undergone surgical intervention. The exclusion criteria included having endocrine and metabolic disorders; chronic kidney and liver disease; sleep disorders; psychiatric and cognitive disorders; heart failure; respiratory diseases such as asthma, influenza, and colds; regular medication; and having received chemotherapy and radiation during all measurements. The flow chart of the study is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the study

Anthropometric measurements and body composition analysis

Anthropometric measurements and body composition analysis were performed by the researcher, who is a specialist dietitian, in the early morning hours after at least 8 h of night fasting. The researcher used the TANITA BC 601 to measure body weight and analyse body composition, including fat mass, percentage fat, and fat-free mass (FFM). The scale’s specifications include a frequency measurement range of 50 kHz, a current measurement range of 100 µA, and a voltage measurement range of 150–1200 °C. We measured the height (cm) with the feet close together and the head at the Frankfort plane using a 0.1 cm sensitive portable stadiometer. We recorded an individual’s waist circumference (in centimetres) to the nearest 0.1 centimetre by placing a nonelastic tape measure midway between the lowest rib border margin and the iliac crest at the end of a normal expiration, ensuring the tape did not compress the skin.

Resting energy expenditure

The Fitmate GS measures VO2 consumption and calculates the RMR by estimating VCO2 production from a fixed RQ of 0.85 based on the abbreviated Weir equation, as it does not contain a VCO2 sensor [18]. Resting energy expenditure measurements were made by using the Cosmed-FitMate GS Indirect Calorimetry with Canopyhood (It is an advanced metabolic measurement system option) (Rome, Italy). FitMate is a reliable and valid system for measuring RMR in many studies [19, 20]. In healthy adults and outpatients, Fitmate GS with Canopyhood has been validated against the gold standard device DELTATRAC and Douglas bag [21–23]. Routine procedures for measuring RMR were followed. Calibration was carried out before each measurement in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. A Canopyhood was then placed over the patient’s head. When the VO2 coefficient of variation was less than 10%, a steady state was achieved. After the instrument stabilized for 15 min, RMR readings were taken. During the canopyhood measurement, outpatients were lying in a supine position for 15 min and instructed to limit movement, talk, and avoid sleeping [24]. The measurements were made during the early morning period between 8.00am and 10.00am in the morning after at least 8 h of night hunger. The participant did not engage in heavy exercise and consumed their usual diet in the day leading up to the REE measurement. Specifically, the method developed by Compher et al. (2006) [25].

As a result, FitMate GS with Canopyhood REE (kcal/day), VO2 (ml/min), Vp (l/min), and FeO2 (%) measurements were evaluated.

Resting energy expenditure prediction equations

Eleven different REE calculation equations were used to evaluate the accuracy of the measured and calculated REE values. The study included these equations: HarriseBenedict-1919, Schofield-1985, Iretone Jones-2002, Mifflin-St. Jean-1990, Barcellos Equation II-2020, Cunningham-1991, Owen-1986, Wang-2000, Institutes of Medicine (IOM)−2004, Henry-2004, and 21 kcal/kg/day (Table 1).

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (The Statistical Package for Social Sciences) Version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data were presented as mean and standard deviation (SD). We evaluated the normality of the data distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk or tests. We used the two-tailed Student’s t-test to compare the mean values of normally distributed variables between the malign and benign prostate groups. We utilized the Mann-Whitney U test to contrast the non-normally distributed malign and benign prostate groups. We statistically analysed the measured REE-related variables using simple linear regression. We used measured REE in a stepwise multiple regression analysis (backward selection technique), integrating all factors with a p value in the simple linear regression analysis of less than 0.20.

We determined the accuracy of the predictive equations for both individuals and the entire population. We determined the accuracy at the group level by calculating the average percentage difference between the predicted and measured REE. We evaluated individual accuracy by calculating the proportion of patients whose predicted REE fell within less than 10% of their measured REE. We determined that accurate predictions ranged from 90 to 110% of the measured REE, classifying values below 90% as an underprediction and values above 110% as a verprediction. We calculated this model’s RMSE to find a more accurate representation of its prediction in our data set. Furthermore, we calculated the bias (mean difference and standard deviation of the differences), along with the 95% confidence intervals, to assess the level of agreement between indirect calorimetry and the 11 equations of interest. In this study, we used a Bland-Altman plot and analysis to compare patients with malign and benign prostate cancer who measured their REE using an indirect calorimeter with those who calculated their REE using different predictive equations. We displayed the mean difference and the limits of agreement as horizontal lines in Bland-Altman plots of individuals with cancerous and noncancerous prostates. We determined the limits of agreement by taking the mean difference plus or minus two times the standard deviation of the differences. We determined significance in all cases using a two-tailed p value of less than 0.05.

Results

The primary characteristics of the prostate subjects are shown in Table 2. The mean age, body weight, BMI, fat percentage, body fat mass, and FFM were not significantly different between the two groups (p > 0.05). It was found that the PSA Total (PSAT) and measured REE values for the malign prostate patient group were significantly higher than those for the benign group (1.76 ± 0.73 ng/ml and 1670.5 ± 266.76 kcal/d, respectively) (p < 0.05).

Table 2.

The main characteristics of subjects

| Variables | Malign prostate patient group (n:41) | Benign prostate patient group (n:42) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| Age (year) | 66.0±6.64 | 64.5±5.94 |

| Weight (kg) | 82.0±12.50 | 80.5±12.72 |

| Height (cm) | 170.0±5.12 | 168.2±5.24 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.3±3.99 | 28.5±4.44 |

| Percent of body fat (%) | 26.8±4.97 | 26.7±6.27 |

| FM (kg) | 22.3±6.80 | 22.0±7.86 |

| FFM (kg) | 56.8±6.67 | 55.6±6.80 |

| PSA Total (ng/ml)** | 4.93±5.44 | 1.76±0.73 |

| Measured REE (kcal/day) ** | 1722.9±272.65 | 1670.7±266.76 |

| VO2 (ml/min) | 250.2±40.70 | 240.4±40.92 |

| Vp (l/min) | 32.5±5.37 | 33.0±6.50 |

| FeO2 (%) | 19.8±0.13 | 19.9±0.13 |

| Tumor Grade (%) | ||

| 1 | 9 (22,0) | - |

| 2 | 6 (14,5) | - |

| 3 | 9 (22,0) | - |

| 4 | 13 (31,7) | - |

| 5 | 4 (9,8) | - |

| D’Amico risk classification (%) | ||

| Low Risk | 10 (24,4) | - |

| Medium Risk | 14 (34,1) | - |

| High Risk | 17 (41,5) | - |

BMI Body Mass Index, FM Fat Mass, FFM Fat Free Mass, PSA Prostate Specific Antigen, REE Resting Energy Expenditure

** The difference between male and female groups were found statistically significant (p < 0.05)

Two standard deviations (SDs) above and below the mean are shown by the dashed lines (limits of agreement).

Table 3 shows measured and calculated REE values of malign and benign prostate groups In our comparison of the Canopyhood measurement with the REE prediction equations for the malign snd benign prostate cancer groups the Novel Equation demonstrated superior results in predicting REE, as evidenced by the variables: predicted-measured REE kcal/d, standard deviation, accuracy percentage, under-prediction percentage, over-prediction percentage, bias percentage, maximum negative error percentage, maximum positive error percentage, and root mean square error. (Table 3).

Table 3.

Evaluation of measured REE with different predictive equations malign and benign prostate group based on differences predicted-measured, SD of predictive REE, percentage of accuracy, under-prediction, over-prediction, bias, maximum negative error, maximum positive error, and RMSE

| REE predictive equations | Difference predicted-measured REE kcal/d |

SD | Accurate-prediction % | Under-prediction % | Over-prediction % | BIAS % | Maximum negative Error % |

Maximum positive Error % |

RMSE* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malign prostate group (MPG) | |||||||||

| Harris Benedict | 123 | 192 | 43.9 | 36.3 | 9.8 | 7.1 | −16.6 | 22.3 | 226 |

| Schofield | −91 | 194 | 60.9 | 2.4 | 36.7 | −5.3 | −43.0 | 13.8 | 212 |

| IretoneJones | 11 | 235 | 48.8 | 26.8 | 24.4 | −0.6 | −47.4 | 21.0 | 233 |

| Mifflin-St.Jeor | 330 | 198 | 26.8 | - | 73.2 | 19.2 | −0.3 | 33.6 | 384 |

| Barcellos Equation II | −630 | 288 | 7.3 | - | 92.7 | −36.5 | −103.2 | 4.4 | 691 |

| Cunningham | 125 | 196 | 56.1 | 39.0 | 4.9 | 7.2 | −26.3 | 21.9 | 231 |

| Owen, | 11 | 199 | 58.5 | 19.5 | 22.0 | −0.6 | −36.8 | 18.9 | 197 |

| Wang, | 93 | 196 | 56.1 | 31.7 | 12.2 | 5.4 | −29.5 | 20.6 | 215 |

| IOM | 74 | 197 | 53.7 | 31.7 | 14.6 | 4.3 | −23.6 | 22.0 | 208 |

| Henry | 100 | 213 | 43.9 | 39.0 | 17,1 | 5.8 | −21.5 | 23.8 | 234 |

| 21 kcal/kg/d | 0.9 | 196 | 58.5 | 17.1 | 24.4 | 0.0 | −28.2 | 15.5 | 194 |

| New Equation MPG | 0.6 | 151 | 80.9 | 7.0 | 12.1 | 0.0 | −28.0 | 11.7 | 149 |

| Benign prostate group (BPG) | |||||||||

| Harris Benedict | 90 | 214 | 50.0 | 33.3 | 16.7 | 5.4 | −31.7 | 27.2 | 230 |

| Schofield | −126 | 209 | 57.1 | 4.8 | 38.1 | −7.5 | −66.8 | 12.2 | 242 |

| IretoneJones | −49 | 234 | 54.8 | 14.2 | 31.0 | −2.9 | −66.6 | 15.2 | 237 |

| Mifflin-St.Jeor | 297 | 213 | 14.2 | 4.8 | 81.0 | 17.7 | −18.2 | 35.4 | 364 |

| Barcellos Equation II | −687 | 261 | 2.4 | - | 97.6 | −41.1 | −131.7 | 3.1 | 734 |

| Cunningham | 99 | 212 | 42.9 | 40.5 | 16.7 | 5.9 | −45.5 | 20.7 | 231 |

| Owen, | −25 | 211 | 61.9 | 14.3 | 23.8 | −1.5 | −58.8 | 17.3 | 210 |

| Wang, | 67 | 212 | 46.7 | 35.7 | 16.7 | 4.0 | −49.0 | 18.8 | 220 |

| IOM | 39 | 211 | 59.5 | 23.8 | 16.7 | 2.3 | −47.2 | 21.0 | 213 |

| Henry | 69 | 217 | 43.9 | 39.0 | 17.1 | 4.1 | −39.8 | 24.9 | 226 |

| 21 kcal/kg/d | −21 | 231 | 50.0 | 23.8 | 26.2 | −1.2 | −34.2 | 22.4 | 229 |

| New Equation BPG | −12 | 208 | 64.2 | 19.0 | 16.8 | 0.0 | −49.0 | 19.9 | 202 |

REE Resting Energy Expenditure and BIAS: mean difference between measured and predicted, BPG Benign Prostate Group, MPG Malign prostate cancer group, İOM Institute of Medicine

*RMSE (kcal/d): Root mean squared error

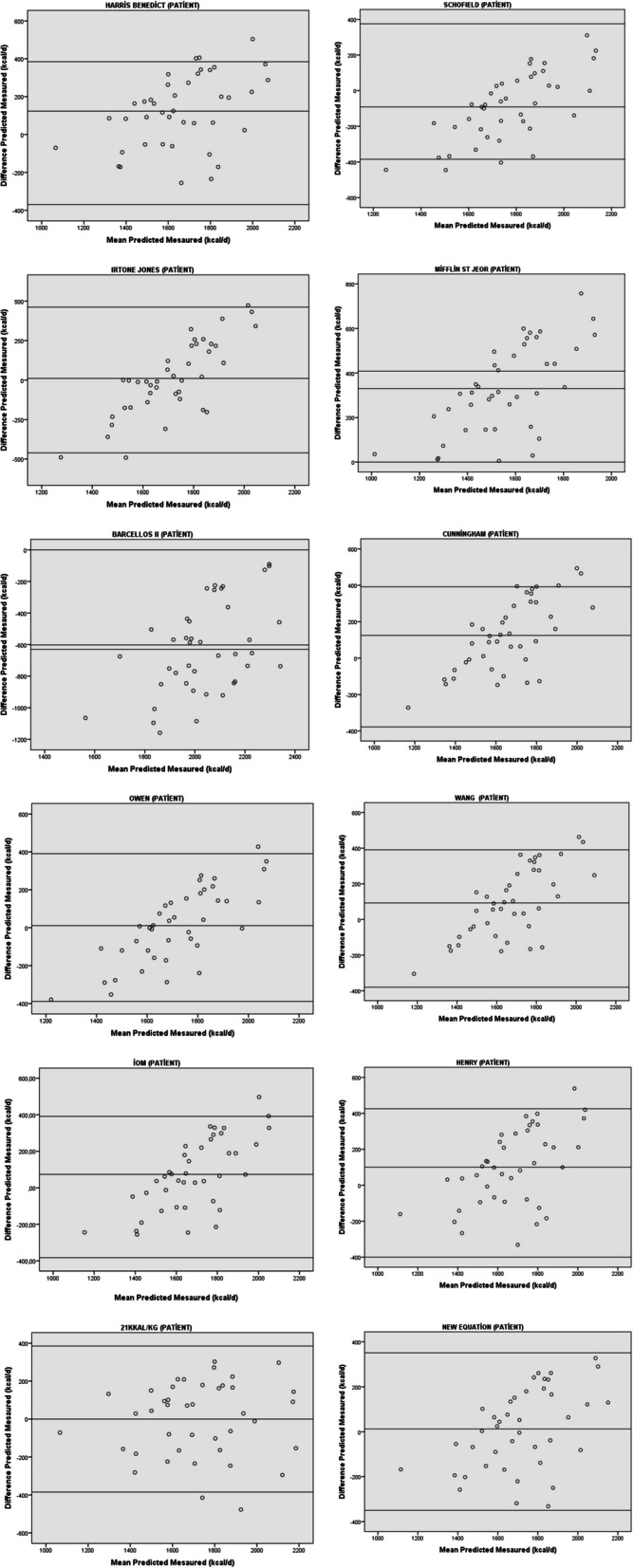

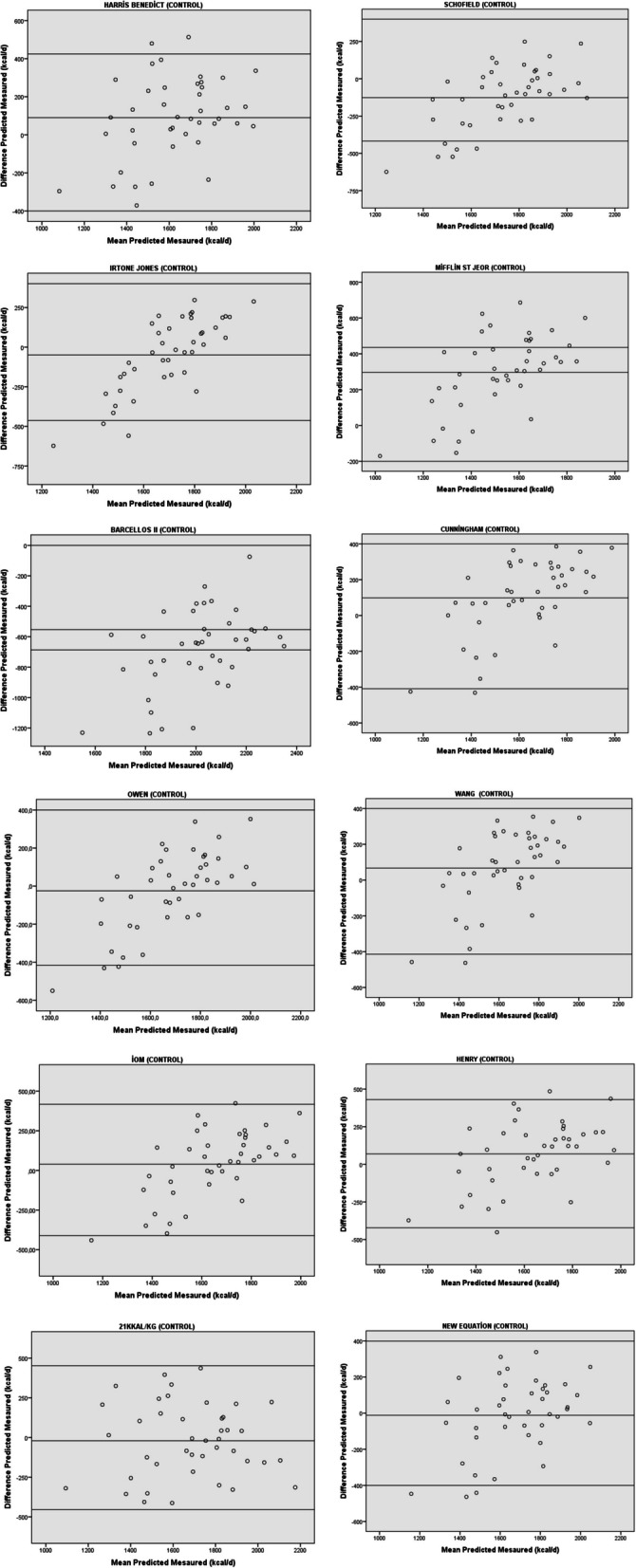

Most equations showed a drift, indicating a systematic error: the larger range of the measured values, the greater discrepancy between the highest and lowest values (Tables 3 and 4). Differences, as well as lower and upper equalisation limits and malign and benign prostate group values calculated with different equations and measures using the direct incalorimetric method, are shown in Bland-Altman plots (Figs. 1 and 2, respectively). Only the Owen equation of 21 kcal/kg/day and the novel equation-MPG were found to have a normally distributed sample of malignant prostate cancer subjects and were therefore approved for use based on Bland-Altman plots. However, only the equation of 21 kcal/kg/day and the Novel Equation-BPG showed a random distribution in prostate benign cancer subjects, so the other equations were deemed unsuitable for use in REE estimation (Fig. 3).

Table 4.

Result of malign and benign prostate group univariate regression analysis

| Variable malign prostate group | Coefficients (95% CI) | Adjusted R2 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | −4.650 | (−17.860; 8.559) | 0.000 | 0.481 |

| Body Weight (kg) | 15.906 | (11.098; 20.714) | 0.523 | < 0.001 |

| Height (cm) | 17.248 | (0.932; 33.564) | 0.082 | 0.039 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 16.811 | (8.618; 25.003) | 0.306 | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 45.999 | (29.701; 62.298) | 0.411 | < 0.001 |

| FFM (kg) | 29.335 | (20.124; 38.546) | 0.503 | < 0.001 |

| Fat Mass (kg) | 21.894 | (11.035; 32.752) | 0.281 | < 0.001 |

| Body Fat Percentage (%) | 16.283 | (−0.681; 33.247) | 0.065 | 0.059 |

| PSA Total (ng/ml) | −1.405 | (−3.691; 0.881) | 0.013 | 0.221 |

| Variable benign prostate group | Coefficients (95% CI) | Adjusted R2 | p value | |

| Age (years) | −6.270 | (−20.463; 7.922) | 0.000 | 0.377 |

| Body Weight (kg) | 13.094 | (7.864; 18.324) | 0.376 | < 0.001 |

| Height (cm) | 9.725 | (−6.227; 25.677) | 0.012 | 0.225 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 11.806 | (4.644; 18.948) | 0.218 | 0.002 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 33.961 | (18.169; 49.761) | 0.304 | < 0.001 |

| FFM (kg) | 23.902 | (13.964; 33.839) | 0.356 | < 0.001 |

| Fat Mass (kg) | 15.516 | (5.870; 25.162) | 0.189 | 0.002 |

| Body Fat Percentage (%) | 11.971 | (−1.070; 25.012) | 0.056 | 0.071 |

| PSA Total (ng/ml) | 9.112 | (−8.284; 26.508) | 0.003 | 0.296 |

Fig. 2.

Bland-Altman a scatter plot comparing the 11 different predictive equations for REE using data from a group of prostate cancer patients who were measured using an indirect calorimeter with a canopy. Two standard deviations (SDs) above and below the mean are shown by the dashed lines (limits of agreement)

Fig. 3.

Bland-Altman a scatter plot comparing the 11 different predictive equations for REE using data from a group of prostate cancer control group who were measured using an indirect calorimeter with a canopy. Two standard deviations (SDs) above and below the mean are shown by the dashed lines (limits of agreement)

Development and Validation of the Novel REE Predictive Equations

At first, we treated REE as the dependent variable and each of the other variables listed in Table 4 as the independent variables, running a univariate regression for each independent variable on its own. Univariate regression analysis revealed that all factors, besides groups, were statistically significant.

Modelling and multiple regression analysis were performed on all relevant variables. The analysis variables were selected using the backwards method. In the end, the model included both body weight (WT), height (HT), fat-free mass (FFM), fat mass (FM), and prostate-specific antigen total (PSAT) as independent variables. Table 5 shows the outcomes of a multiple regression analysis.

Table 5.

Result of malign and benign prostate group canopy multiple regression analysis

| Variable malign prostate group |

Coefficients (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 3192,258 | (909,754; 5474,671) | 0.007 |

| WT | 208,326 | (103,911; 312,741) | < 0.001 |

| HT | −20,285 | (−35,329; 5,042) | 0.011 |

| FFM | −187,549 | (−295,044; 80,754) | 0.001 |

| FM | −203,241 | (−309,408; 97,074) | < 0.001 |

| PSAT | 4,194 | (1,654; 6,818) | 0.003 |

| Variable benign prostate group | Coefficients (95% CI) | p value | |

| Constant | 615,922 | (189,491; 1042,353) | 0.006 |

| WT | 13,094 | (7,864; 18,324) | < 0.001 |

WT Body Weight, FM Fat Mass, HT Height and PSAT PSA Total

Adjusted R2 for the model malign prostate cancer patient: 0.548

Adjusted R2 for the model benign prostate cancer patient: 0.375

We present the equation and results from Table V below.

Novel prediction equation for malign prostate patient

Novel prediction equation for benign prostate patient

Discussion

An accurate calculation of energy expenditure REE is necessary for estimating energy needs in prostate cancer. The purpose of this research was to evaluate the accuracy of the established novel equation for predicting REE in malign and benign prostate patients versus the accuracy of the previously used predictive equations based on REE measured by indirect calorimetry. In the present study, findings demonstrated that the previous equations used to predict the REEs of adults with prostate cancer (over the age of 40) show a large disparity between the two, contain a large number of errors, and frequently result in over- or underestimating REE.

Cancer-induced metabolic alterations can influence both REE and energy intake, potentially resulting in either a negative or positive energy balance. Due to the challenges in directly measuring TEE, REE the predominant component of TEE, is frequently assessed to estimate energy consumption [26]. Resting energy expenditure is varied in cancer and may be affected by alterations in tumour burden, systemic inflammation, and body composition. The tumor’s energetic requirement can significantly influence energy metabolism, particularly in the context of metastases [27]. In cancer patients, additional energy expenditure is estimated to be 100–1400 kcal/day, depending on tumor burden [26].The factors of fat-free mass (FFM), body size, age, gender, and body fat, among others, are the most important in determining resting metabolic rate [28]. In another study. study emphasised the importance of total body fat mass, fat-free mass, and abdominal adiposity in determining RMR [29]. The modified metabolic processes induced by a high-calorie diet and a sedentary lifestyle can result in obesity, diabetes, dyslipidaemia, hypertension, and perhaps MetS, accompanied by alterations in REE and TEE expenditure, which may correlate with an elevated risk of PCa diagnosis and severity [30]. Emerging research indicates that adipocytes generated from escalating obesity serve as a lipid reservoir for neighbouring prostate cancer cells [31]. In our study, people were classified as overweight based on their BMI results, and their body fat percentages above typical thresholds. While it is believed that elevated fat mass influences resting energy expenditure (REE), the recently diagnosed status of the patients and their low tumour risk and stage classifications are considered to have a negligible impact on REE.Table 2 presents the subjects’ primary characteristics, but no statistical significance was found. This situation was thought to be related to the homogeneous distribution of the groups.

Metabolic anomalies that could lead to inaccuracies in the measurement of resting energy expenditure (REE) in cancer patients may influence the efficacy of REE estimation Eqs. [32–34]. When making nutritional recommendations for cancer patients, it is important to first determine whether or not their metabolism and energy expenditure have been altered [35]. With so many equations involved in estimating energy expenditure, it’s easy to see how mistakes can add up over time, which can reduce the impact of the intervention. Consequently, the best equation for estimating REE has not yet been determined [36, 37]. Evaluation of FitMate GS with Canopyhood REE with different predictive equations in malign and benign prostate group values was presented in Table 3. An accurate prediction was defined as one that fell between 90% and 110% of the actual REE. Underprediction was defined as a prediction of less than 90%, and overprediction was defined as a prediction of more than 110%. It was found that the percentage of adult hospital patients whose REE were correctly predicted was low, ranging from 8 to 49% across all equations in a study [37]. Another study found that the accuracy of correctly predicted REE varied between 9.6% and 62% across all equations [38]. The study revealed that the REE measured by IC exhibited lower average discrepancies of + 59 and + 52 kcal when compared to Barcellos I and II, respectively; however, it also demonstrated broad limitations of agreement ranging from + 1542 to -1424 kcal and + 1429 to -1326 kcal, respectively [39]. In the present study (Tables 3 and 4) Upon comparing the unique energy predicting equation we derived with prior REE estimation equations, we believe that its validity and reliability are substantial.

Bias was calculated as the percentage disparity between the predicted and measured REE. It was found in a study that the REE from FitMate GS exhibited a fanning effect, with smaller REE values exhibiting a narrower spread of biases and a positive proportional bias being present. The FitMate GS showed little individual variation and high group precision because of its low bias [19]. As one study found in a sample of cancer patients, just over half had their REE predicted correctly using the Harris-Benedict, Owen et al., Mifflin et al., or 21 kcal/kg methods. Spread of bias was clearly visible for the group of cancer patients, with increasing REE values between measured REE and REE predicted by the equations of Cunningham et al. and Wang et al. The observed bias with REE predicted by the equation of Schofield showed a tendency toward underestimating measured REE with increasing REE values, but this trend was not statistically significant [35]. Using classical equations (Harris Benedict, Schofield, Iretone Jones, and Mifflin-St. Jeor), researchers found that the mean of the measured REE was greater than the classical equations in a study of patients with digestive cancer [10]. Upon comparing the unique energy estimation equation we derived with the BIAS value and existing REE estimation equations, we conclude that the REE estimate demonstrates its optimality.

Numerous studies have verified the Schofield Eq. (1985), making it one of the most widely used equations to date. When applied to critically ill patients and the majority of patients overall, it was deemed inadequate for estimating REEs [40, 41]. Although not statistically significant, the bias observed with REE predicted from the equation of Schofield showed a tendency toward underestimation of measured REE with increasing REE values in a study on the determination of resting energy expenditure in patients receiving anticancer treatment [35]. Except for men over the age of 60, Henry and equations gave lower values than Schofield equations. Henry’s equations were the most reliable in males [42]. One study highlighted the fact that the Schofield equation is most suitable for adults [43]. The relevance of measuring REE by indirect calorimetry in order to better adequately provide nutritional support to cancer patients is supported by the Barcellos equations, allowing for less predictive and more accurate mean REE estimation in cancer patients [10]. The results of this research showed that the Barcellos II equation is more accurate than the existing equations for estimating REEs. Patients in hospitals were less likely to develop malnutrition when REE was accurately estimated and used to guide nutritional intervention [44]. Cunningham proposed an alternative equation that takes into account the correlation between RMR and FFM. In a study involving both normal-weight and obese male subjects, served as the basis in equation [45]. In the study, Cunningham equation gave the last one in the estimation of REE of male individuals [46]. Similarly, the IOM equation, used for predicting the REEs was found to have low accuracy and high bias and RMSE values [14]. The result, related to the all equation, was presented in Tables 3 and 4. This is widely assumed to have its RMSE in racial and genetic predispositions. Many studies, have recommended that individual societies adopt the equations that have been tailored to their needs. We assert that the newly derived energy estimation equation will demonstrate a strong and significant correlation with all variables pertinent to the synthesis of rare earth element (REE) estimation, thereby yielding optimal REE results in individuals with prostate cancer (PCa) by incorporating disease-specific variables. Subsequent research utilising the unique energy equation will validate this concept.

Since none of the existing prediction equations were appropriate for a population of men with prostate cancer, in this study was developed a novel prediction equation. Consistent with expectations, the novel equation found that WT, height, FFM, FM and PSA Total were the strongest predictors of REE, accounting for R2:54,8% of the variance in REE among men with malign prostate group and accounting for R2:37,5% of the variance in REE among men with benign prostate group in Table 5. The findings here corroborate those of other studies. This study’s findings were consistent with those of a previous one, which also found that FM was a major factor in determining adults’ REEs [47]. Genetics may also account for the variation in REE between populations, which is known to be linked to FM and WT. Since body composition equations are usually population-specific, they should be more appropriate for use as predictive equations for REE [48]. In our opinion, the information we gleaned from the outcomes of the malign and benign prostate group FitMate GS with Canopyhood multiple regression analysis will provide us with more precision in predicting the REE particular to this group of PSAT values, which is incorporated into the malign prostate group equation.

This study had some strengths and limitations. This is the first research to examine the REEs of patients with benign and malign prostate cancer as determined by indirect calorimetry. The current study is the initial step in evaluating REE using novel predictive equations in these groups. Our study shown strength through the strong association between age, body weight, height, BMI, percentage of fat mass and fat-free mass, tumour grade and stage, and PSAT, all of which were utilised in the RMR assessment of malign and benign prostate cancer patients and indicated significant correlations with changes in REE. Furthermore, the PSAT parameter, utilised in regression analysis, delineated the novel REE prediction equation. Furthermore, the utilisation of the gold standard for assessing energy expenditure, specifically the indirect calorimetry model (FitMate GS with canopy hood), in evaluating the resting metabolic rate of patients with malign and benign prostate cancer is another strength of our study. Notwithstanding these strengths, the G Power analysis indicated a low number of malign and benign patients, as assessed by the reviwer. The findings are representative of this sample population, and it would be advantageous to apply the equations created for prostate cancer patients in studies with larger samples. Furthermore, the absence of an advanced bioelectrical impedance device in our study precluded the acquisition of phase angle and body composition data, yet this limitation did not compromise the accuracy of the novel REE prediction equation. This could represent a limitation of our study.

Conclusion and future directions

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that there was substantial variation in REE estimation precision across the predictive equations. As a result, estimating REEs is necessary to optimize treatment and survival rates for people with prostate cancer. Our research was the first to synthesise a large number of REE predictive equations and use FitMate GS with Canopyhood to create a novel prediction equation specifically for malign and benign prostate cancer patients. When indirect calorimetry was unavailable, we recommended a novel prediction equation to accurately predict the REEs of prostate cancer. It would be practical to determine the energy requirement for treating malign and benign prostate cancer by using the novelly developed equations in the prediction of REE in the clinic.

Acknowledgements

All the men with malign and benign prostate cancer who agreed to take part in this study are deeply appreciated. Sincere gratitude is extended for their timely and enthusiastic assistance. None of the authors had a personal or financial conflict of interest. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The Cosmed-FitMate GS Indirect Calorimetry with canopy-hood (Rome, Italy) system was made available to us by the Elsa Ortopedi firm, and we would also like to thank Mithat EMRİ and Erdem BİLİR for their essential contributions to the our study.

Abbreviations

- BMR

Basal Metabolic Rate

- FFM

Fat Free Mass

- IOM

Institutes of Medicine

- REE

Resting Energy Expenditure

- RMSE

The root mean squared error

- SD

Strandard Deviation

- PSAT

Prostate Specific Antigen Total

Authors’ contributions

T.K.; investigation, conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, writing - review & editing. N.A.T; investigation, conceptualization, methodology, supervision, project administration. S.Y. and T.S.S; supervision, review, and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Gazi University Ethic Committie with decision number 4 on 7 April 2020. Clear explanations were provided for the parents with regard to the purpose of the study, after which written informed consent was obtained from all the parents in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Platz EA. Energy imbalance and prostate cancer. J Nutr. 2002;132(11):S3471-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernández-Verdejo R, Sanchez-Delgado G, Ravussin E. Energy expenditure in humans: principles, methods, and changes throughout the life course. Annu Rev Nutr. 2024;44:51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee on the Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2023. 4, Factors Affecting Energy Expenditure and Requirements. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK591031/. [PubMed]

- 4.Osborne MT, Edgar APD, Fairchild APT, Galna DB, Wood WPF, Allan MB, Huray MTL, Wall APB. Concurrent validity of clinical equations to predict resting energy expenditure compared to indirect calorimetry in non-severe burn patients. J Clin Exerc Physiol. 2024;13(s2):468–468. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McNeil J. Energy balance in cancer survivors at risk of weight gain: a review. Eur J Nutr. 2023;62(1):17–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yébenes JC, Bordeje-Laguna ML, Lopez-Delgado JC, Lorencio-Cardenas C, Martinez De Lagran Zurbano I, Navas-Moya E, Servia-Goixart L. Smartfeeding: a dynamic strategy to increase nutritional efficiency in critically ill patients—positioning document of the Metabolism and Nutrition Working Group and the Early Mobilization Working Group of the Catalan Society of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine (SOCMiC). Nutrients. 2024;16(8):1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Soom T, Tjalma W, Van Daele U, Gebruers N, van Breda E. Resting energy expenditure, body composition, and metabolic alterations in breast cancer survivors vs. healthy controls: a cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2024;24(1):117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tüccar TB, Tek NA. Determining the factors affecting energy metabolism and energy requirement in cancer patients. J Res Med Sciences. 2021;26:124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Purcell SA, Elliott SA, Baracos VE, Chu QS, Sawyer MB, Mourtzakis M, Easaw JC, Spratlin JL, Siervo M, Prado CM. Accuracy of resting energy expenditure predictive equations in patients with cancer. Nutr Clin Pract. 2019;34(6):922–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barcellos PS, Borges N, Torres DP. Resting energy expenditure in cancer patients: agreement between predictive equations and indirect calorimetry. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2021;42:286–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D’Oria V, Spolidoro GCI, Agostoni CV, Montani C, Ughi L, Villa C, Marchesi T, Babini G, Scalia Catenacci S, Donà G. Validation of indirect calorimetry in children undergoing single-limb non-invasive ventilation: a proof of concept, cross-over study. Nutrients. 2024;16(2): 230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delsoglio M, Achamrah N, Berger MM, Pichard C. Indirect calorimetry in clinical practice. J Clin Med. 2019;8(9):1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muthuraju S: Assessment of energy requirements in patients diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma. Denton: Texas Woman’s University; 2023. vol 4 p. 34. https://twu-ir.tdl.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/8daae120-1c75-47f4-8d3b-70a0f8cdc3d2/content.

- 14.Acar-Tek N, Ağagündüz D, Çelik B, Bozbulut R. Estimation of resting energy expenditure: validation of previous and new predictive equations in obese children and adolescents. J Am Coll Nutr. 2017;36(6):470–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tek NA, Yurtdaş G, Cemali Ö, Bayazıt AD, Çelik ÖM, Uyar GÖ, Güneş BD, Özbaş B, Erten Y. A comparison of the indirect calorimetry and different energy equations for the determination of resting energy expenditure of patients with renal transplantation. J Ren Nutr. 2021;31(3):296–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin Y-C, Wang C-H, Ling HH, Pan Y-P, Chang P-H, Chou W-C, Chen F-P, Yeh K-Y. Inflammation status and body composition predict two-year mortality of patients with locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma under provision of recommended energy intake during concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Biomedicines. 2022;10(2): 388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.da Silva BR, Pagano AP, Kirkham AA, Gonzalez MC, Haykowsky MJ, Joy AA, King K, Singer P, Cereda E, Paterson I. Evaluating predictive equations for energy requirements throughout breast cancer trajectory: a comparative study. Clin Nutr. 2024;43(9):2073–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weir JV. New methods for calculating metabolic rate with special reference to protein metabolism. J Physiol. 1949;109(1–2):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Purcell SA, Elliott SA, Ryan AM, Sawyer MB, Prado CM. Accuracy of a portable indirect calorimeter for measuring resting energy expenditure in individuals with cancer. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2019;43(1):145–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Purcell SA, Johnson-Stoklossa C, Tibaes JRB, Frankish A, Elliott SA, Padwal R, Prado CM. Accuracy and reliability of a portable indirect calorimeter compared to whole-body indirect calorimetry for measuring resting energy expenditure. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2020;39:67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blond E, Maitrepierre C, Normand S, Sothier M, Roth H, Goudable J, Laville M. A new indirect calorimeter is accurate and reliable for measuring basal energy expenditure, thermic effect of food and substrate oxidation in obese and healthy subjects. e-SPEN Eur E-J Clin Nutr Metabolism. 2011;6(1):e7-15. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lupinsky L, Singer P, Theilla M, Grinev M, Hirsh R, Lev S, Kagan I, Attal-Singer J. Comparison between two metabolic monitors in the measurement of resting energy expenditure and oxygen consumption in diabetic and non-diabetic ambulatory and hospitalized patients. Nutrition. 2015;31(1):176–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nieman DC, Austin MD, Benezra L, Pearce S, McInnis T, Unick J, Gross SJ. Validation of Cosmed’s FitMate™ in measuring oxygen consumption and estimating resting metabolic rate. Res Sports Med. 2006;14(2):89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yeung SS, Trappenburg MC, Meskers CG, Maier AB, Reijnierse EM. Inadequate energy and protein intake in geriatric outpatients with mobility problems. Nutr Res. 2020;84:33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Compher C, Frankenfield D, Keim N, Roth-Yousey L, Group EAW. Best practice methods to apply to measurement of resting metabolic rate in adults: a systematic review. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106(6):881–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bulmuş Tüccar T, Acar Tek N. Determining the factors affecting energy metabolism and energy requirement in cancer patients. J Res Med Sci. 2021;26:124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Purcell SA, Wallengren O, Baracos VE, Lundholm K, Iresjö B-M, Chu QS, Ghosh SS, Prado CM. Determinants of change in resting energy expenditure in patients with stage III/IV colorectal cancer. Clin Nutr. 2020;39(1):134–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maury-Sintjago E, Muñoz-Mendoza C, Rodríguez-Fernández A. Ruíz-De La Fuente M. Predictive equation to estimate resting metabolic rate in older Chilean women. Nutrients. 2022;14(15):3199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weststrate JA, Dekker J, Stoel M, Begheijn L, Deurenberg P, Hautvast JG. Resting energy expenditure in women: impact of obesity and body-fat distribution. Metabolism. 1990;39(1):11–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Nunzio C, Brassetti A, Cancrini F, Prata F, Cindolo L, Sountoulides P, Toutziaris C, Gacci M, Lombardo R, Cicione A. Physical inactivity, metabolic syndrome and prostate cancer diagnosis: development of a predicting nomogram. Metabolites. 2023;13(1): 111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saha A, Kolonin MG, DiGiovanni J. Obesity and prostate cancer—microenvironmental roles of adipose tissue. Nat Reviews Urol. 2023;20(10):579–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin L, Birdsell L, MacDonald N, Reiman T, Clandinin MT, McCargar LJ, Murphy R, Ghosh S, Sawyer MB, Baracos VE. Cancer cachexia in the age of obesity: skeletal muscle depletion is a powerful prognostic factor, independent of body mass index. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(12):1539–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Purcell S, Elliott S, Baracos V, Chu Q, Prado C. Key determinants of energy expenditure in cancer and implications for clinical practice. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70(11):1230–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheas MN, Ali SR, Safdar W, Tariq MR, Ahmed S, Ahmad N, Hameed A, Qazi AS. Nutritional assessment in cancer patients. In: Therapeutic approaches in cancer treatment. Cham: Springer; 2023. p. 285–310. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Reeves MM, Battistutta D, Capra S, Bauer J, Davies PS. Resting energy expenditure in patients with solid tumors undergoing anticancer therapy. Nutrition. 2006;22(6):609–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cordoza M, Chan L-N, Bridges E, Thompson H. Methods for estimating energy expenditure in critically ill adults. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2020;31(3):254–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kruizenga HM, Hofsteenge GH, Weijs PJ. Predicting resting energy expenditure in underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese adult hospital patients. Nutr Metabolism. 2016;13(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Almajwal AM, Abulmeaty M. New predictive equations for resting energy expenditure in normal to overweight and obese population. Int J Endocrinol. 2019;(57274960):15. 10.1155/2019/5727496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Barcellos PS, Borges N, Torres DPM. Resting energy expenditure in cancer patients: agreement between predictive equations and indirect calorimetry. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2021;42:286–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kamimura MA, Avesani CM, Bazanelli AP, Baria F, Draibe SA, Cuppari L. Are prediction equations reliable for estimating resting energy expenditure in chronic kidney disease patients? Nephrol Dialysis Transplantation. 2011;26(2):544–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reeves MM. Estimating patients’ energy requirements: cancer as a case study. Queensland University of Technology; 2004.

- 42.Ramirez-Zea M. Validation of three predictive equations for basal metabolic rate in adults. Public Health Nutr. 2005;8(7a):1213–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xue J, Li S, Zhang Y, Hong P. Accuracy of predictive resting-metabolic-rate equations in Chinese mainland adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(15): 2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barcellos PS, Borges N, Torres DP. New equation to estimate resting energy expenditure in non-critically ill patients. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2020;37:240–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buch A, Diener J, Stern N, Rubin A, Kis O, Sofer Y, Yaron M, Greenman Y, Eldor R, Eilat-Adar S. Comparison of equations estimating resting metabolic rate in older adults with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Med. 2021;10(8):1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schusdziarra V, Wolfschläger K, Hausmann M, Wagenpfeil S, Erdmann J. Accuracy of resting energy expenditure calculations in unselected overweight and obese patients. Annals Nutr Metabolism. 2014;65(4):299–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bosy-Westphal A, Müller MJ, Boschmann M, Klaus S, Kreymann G, Lührmann PM, Neuhäuser-Berthold M, Noack R, Pirke KM, Platte P. Grade of adiposity affects the impact of fat mass on resting energy expenditure in women. Br J Nutr. 2008;101(4):474–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products N, Allergies. Scientific opinion on dietary reference values for energy. EFSA J. 2013;11(1):3005. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.