Abstract

Background:

Joint arthroplasty effectively treats osteoarthritis, providing pain relief and improving function, but postoperative venous thromboembolism (VTE) remains a common complication. This study therefore assessed the effectiveness and safety of aspirin compared with oral anticoagulants (OACs) for VTE prophylaxis after joint arthroplasty.

Methods:

A systematic review and meta-analysis was performed by searching PubMed, Embase, the Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) up to May 14, 2024, that compared the effect of aspirin versus OACs on VTE prophylaxis in adults undergoing joint arthroplasty. Data extraction followed the PRISMA guidelines. Two independent researchers conducted the literature searches and data extraction. A random-effects model was used to estimate effects. The primary outcome was the incidence of VTE, including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE); secondary outcomes included bleeding, wound complications, and mortality.

Results:

The meta-analysis included 11 RCTs with a total of 4,717 participants (55.1% female) from several continents. The relative risk (RR) of VTE following joint arthroplasty was 1.11 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.93 to 1.32) for aspirin compared with OACs. Similar results were observed for DVT (RR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.90 to 1.40) and PE (RR, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.51 to 2.71). There were no significant differences in the risks of bleeding, wound complications, or mortality between patients receiving aspirin and those receiving OACs. Subgroup analyses considering factors such as study region, type of joint surgery, type of VTE detection, year of publication, use of mechanical VTE prophylaxis, aspirin dose, type of OAC comparator, study quality, and funding also found no significant differences in VTE incidence between aspirin and OACs. The overall quality of evidence for VTE and DVT outcomes was high.

Conclusions:

Based on high-quality evidence from RCTs, aspirin is as effective and safe as OACs in preventing VTE, including DVT and PE, after joint arthroplasty, without increasing complications.

Level of Evidence:

Therapeutic Level I. See Instructions for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Joint arthroplasty is a definitive treatment for conditions such as late-stage osteoarthritis; it markedly alleviates pain, improves quality of life, and preserves joint function to the greatest extent possible. However, postoperative venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a typical complication. Reports indicate that without effective prophylactic measures, the incidence of VTE within 90 days after joint arthroplasty can be as high as 60%1. VTE development increases treatment costs and hospital stay and may lead to potentially life-threatening embolization of vital organs2.

Current literature confirms the efficacy of factor Xa inhibitors (e.g., rivaroxaban), low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), and warfarin in preventing postoperative VTE; however, there is no consensus on the optimal chemoprophylactic agent3,4. Existing medications reduce the incidence of VTE; however, excessive intervention may increase the risks of postoperative bleeding, wound infection, and internal hemorrhage5. In addition, LMWH requires long-term subcutaneous injections, which are inconvenient for patients after discharge. Oral anticoagulants such as rivaroxaban are expensive, and although warfarin is relatively affordable, patients receiving long-term warfarin therapy require regular monitoring of the international normalized ratio (INR).

Previous studies suggest that aspirin alone, as a chemoprophylactic agent for VTE after joint arthroplasty, is not less effective than other chemical prophylactics5,6. Similarly, Matharu et al. revealed no significant differences between aspirin and other agents in the prevention of VTE, including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), and in the rates of bleeding, infection, and mortality compared with alternative medications7. Moreover, aspirin administration is markedly less expensive compared with oral anticoagulants8,9. The American College of Chest Physicians guidelines state that aspirin can be used as a chemoprophylactic agent for VTE after hip and knee arthroplasty10, although using aspirin as the sole prophylactic agent for VTE after joint arthroplasty is relatively rare in current clinical practice. However, no meta-analysis has compared the efficacy of aspirin with that of oral anticoagulants (OACs). Therefore, we used that evidence-based medicine method to investigate the clinical effectiveness of aspirin compared with OACs in preventing VTE after joint arthroplasty.

Materials and Methods

This study followed the principles outlined in the Handbook of the Cochrane Collaboration11,12 and the guidelines established by the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement13. The protocol for this meta-analysis was registered in PROSPERO.

Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were (1) a randomized controlled trial (RCT) evaluating the efficacy and/or safety of aspirin and OACs for preventing VTE in adults (≥18 years old) undergoing primary and/or revision hip arthroplasty and/or knee arthroplasty; (2) reporting of outcomes including VTE, DVT, PE, and/or associated complications; (3) use of a combined VTE prevention strategy including aspirin as 1 of the medications in the aspirin arm (initial treatment with LMWH or an oral anticoagulant followed by a longer course of aspirin), to reflect current clinical practice; and (4) administration of the medication for VTE prophylaxis lasting ≥14 days.

Search Strategy

Two of the authors performed the search in PubMed, Embase, the Web of Science, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials from the inception date of each database to May 14, 2024, using the keywords (“hip arthroplasty” or “knee arthroplasty”), “aspirin” and “anticoagulant,” and (“venous thromboembolism” or “pulmonary embolism” or “deep vein thrombosis” or “complication”) in humans. Detailed search strategies are reported in the Appendix. No language restrictions were applied in the search.

Study Selection

After duplicates were removed, 2 independent researchers reviewed all titles and abstracts and evaluated the inclusion and exclusion criteria. For studies deemed potentially eligible, the full text was retrieved for additional screening. In addition, we reviewed the reference lists of all included articles to identify other potentially eligible studies. If the 2 researchers disagreed on a study’s eligibility and could not reach a consensus, the senior researcher made the final decision following a group discussion.

Data Extraction

Two researchers independently extracted relevant data from the selected trials using a standard form. The data included the first author’s name, publication year, country, study type, sample size, age, VTE prophylactic regimen, follow-up, and outcomes. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. For trials with >2 groups or with factorial designs, only the necessary information and data were extracted.

Assessment of Risk of Bias and Quality of Evidence

Two researchers independently assessed the quality of the RCTs using the Cochrane risk-of-bias criteria, grading each item as having low, high, or unclear risk11,14. The overall quality of each trial was then categorized as low (high risk in randomization and/or allocation concealment), high (low risk in both randomization and allocation concealment, with other criteria low or unclear), or moderate (not meeting high- or low-quality criteria). The GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) approach was also used to assess the overall quality of evidence based on study limitations, inconsistency, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias15.

Data Synthesis

A meta-analysis was performed using Stata (version 17; StataCorp) and R (version 4.4.0; R Core Team). Heterogeneity was evaluated using the Q test and calculation of the I2 value. Given the potential heterogeneity among the trials, analyses utilized a random-effects model. The relative risk (RR) with a corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) was used for assessing count outcomes. When dealing with multiple correlated comparisons in the same experiment, we combined groups to create a single pairwise comparison (e.g., if a study tested aspirin and multiple OACs, the OAC groups were combined), in accordance with the guidance provided by the Cochrane Handbook12. Subgroup analyses were performed on the basis of predetermined study-level characteristics (including study region, type of joint surgery, VTE identification type, publication year, use of mechanical VTE prophylaxis, aspirin dose, type of OAC comparator, study quality, and study funding) that could have introduced heterogeneity into the results. Potential publication bias was evaluated using established methods, including Begg funnel plots and Egger regression symmetry tests. We also performed a sensitivity analysis by excluding individual studies.

Results

Study Identification

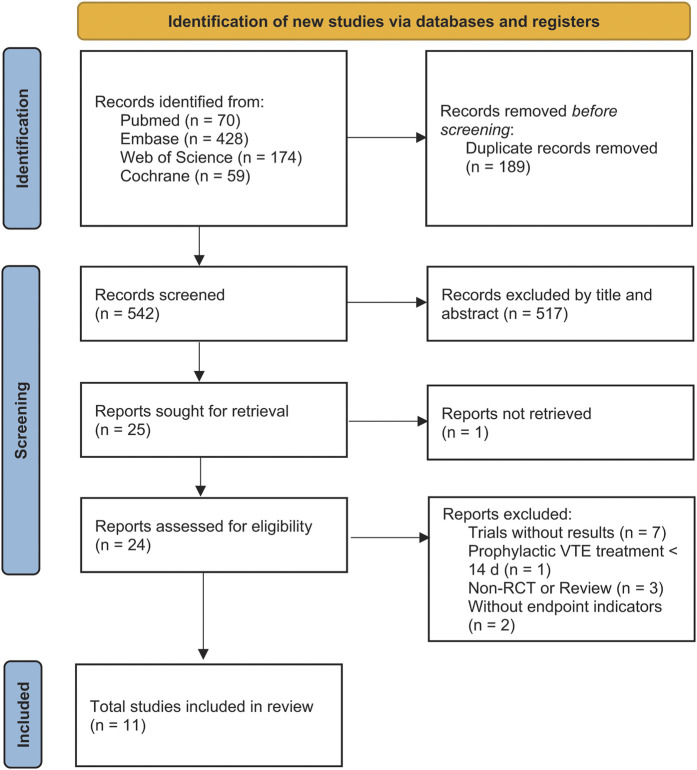

The initial search yielded 731 potentially relevant articles (Fig. 1). Following the screening of titles and abstracts, 24 articles were chosen for full-text review. Of these, 13 were excluded (see Appendix). The remaining 11 RCTs met the criteria for inclusion in the meta-analysis (Table I).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for the search and selection of included studies.

TABLE I.

Characteristics of the Included Studies*

| Study | Country | Participants | Duration | DVT Diagnostic Methods | Aspirin | OAC | Use of Mechanical VTE Prophylaxis | Mean Age (yr) | Females | Total No. of Subjects | Min. Follow-up | Funding | Outcomes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin | OAC | Aspirin | OAC | Aspirin | OAC | |||||||||||

| Anderson, 201816 | Canada | Primary and revision TKA and THA | 2013-2016 | Venous ultrasonography, lung scan, and CT pulmonary angiography | 10 mg rivaroxaban qd for 5 d + 81 mg aspirin qd for 30 d (hip) or 9 d (knee) | 10 mg rivaroxaban qd for 5 d + additional 30 d (hip) or 9 d (knee) | Per local policy (none, IPC, graduated stockings, or both) | 62.9 | 62.7 | 903 | 884 | 1,707 | 1,717 | 90 d | NS | VTE, DVT, PE, death, myocardial infarction, stroke, wound infection, bleeding |

| Colleoni, 201717 | Brazil | Primary TKA | NS | Venous ultrasonography | 150 mg aspirin bid for 14 d | 10 mg rivaroxaban qd for 14 d | NS | 71.21 | 67.11 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 18 | 4 wk | NS | DVT, wound complication, systemic complication, hemoglobin and hematocrit levels |

| Hongnaparak, 202118 | Thailand | Primary TKA | 2016-2018 | Venous ultrasonography or CT | 300 mg aspirin qd for 14 d | 10 mg rivaroxaban qd for 14 d | NS | 68.15 | 70.5 | 13 | 17 | 20 | 20 | 14 d | Yes | DVT, PE, wound complication |

| Jatoi, 202219 | Pakistan | Primary THA | NS | Venous ultrasonography | 2,000 U enoxaparin qd for 5 d + 100 mg aspirin qd for 16 d | 2,000 U enoxaparin qd for 5 d + 10 mg rivaroxaban qd for 16 d | NS | 58.87 | 59.44 | 42 | 25 | 80 | 80 | 10 mo | NS | DVT |

| Jiang, 201420 | China | Primary TKA | 2012-2013 | Venous ultrasonography | 100 mg aspirin qd for 14 d | 5,000 U LMWH qd for 5 d + 10 mg qd rivaroxaban for 9 d | IPC + thromboembolic deterrent stocking | 65.1 | 63.8 | 55 | 56 | 60 | 60 | 6 wk | NS | DVT, VTE, blood loss, wound complication, cost |

| Lotke, 199621 | U.S.A. | Primary and revision THA and TKA | 1989-1990 | Venograms and ventilation perfusion scans | 325 mg aspirin bid for 6 wk | Warfarin, maintaining prothrombin time of 1.2-1.5 INR, for 6 wk | NS | 66.4 | 67.1 | 100 | 92 | 166 | 146 | 6 mo | NS | DVT, PE, wound complication |

| Salzman, 197123 | England | Hip arthroplasty | NS | Lung perfusion scan and pulmonary angiography (no venogram or fibrinogen uptake test used for DVT detection) | 600 mg aspirin bid for 21-35 d | Warfarin (dosage adjusted for prothrombin time) for 21-35 d | NS | 51 | 48 | 22 | 22 | 43 | 43 | NA | NS | DVT, PE, VTE, blood loss, wound complication |

| Ren, 202122 | China | Primary THA | 2019-2020 | Venous ultrasonography | 100 mg aspirin bid for 5 wk | 10 mg rivaroxaban qd for 5 wk | IPC | 54.5 | 50 | 21 | 25 | 34 | 36 | 90 d | Yes | VTE, DVT, PE, bleeding events, blood test, HHS, complication |

| Woolson, 199124 | U.S.A. | Primary and revision THA | 1986-1989 | Venography or venous ultrasonography | 650 mg aspirin bid | Warfarin, maintaining prothrombin time 1.2-1.3 INR | IPC + graduated stockings | 62.3 | 67.6 | 36 | 38 | 72 | 69 | 90 d | NS | DVT, PE, wound complication |

| Zhou, 202325 | China | Primary TKA | 2020-2021 | Venous ultrasonography | 100 mg aspirin qd for 30 d | 10 mg rivaroxaban qd for 30 d | NS | 66.4 | 64.8 | 34 | 33 | 60 | 60 | 90 d | NS | VTE, PE, blood loss, hematologic parameters, blood transfusion rate, bleeding complication |

| Zou, 201426 | China | Primary TKA | 2011-2013 | Venous ultrasonography | 100 mg aspirin qd for 14 d | 10 mg rivaroxaban qd for 14 d | NS | 62.7 | 63.5 | 82 | 70 | 110 | 102 | 4 wk | NS | DVT, PE, wound complication, blood loss |

DVT = deep vein thrombosis, OAC = direct oral anticoagulant, VTE = venous thromboembolism, THA = total hip arthroplasty, TKA = total knee arthroplasty, CT = computed tomographic, qd = 4× daily, IPC = intermittent pneumatic compression, NS = not specified, PE = pulmonary embolism, bid = 2× daily, LMWH = low-molecular-weight heparin, HHS = Harris hip score.

Study Characteristics

The 11 RCTs16-26 included 4,717 participants (2,366 in the aspirin group and 2,351 in the control group), of whom 2,597 (55.1%) were female. The mean age of the participants was 62.8 years. Nine trials were open-label17,19-26, and the remaining 2 were double-blinded16,18. Six studies were conducted in Asia18-20,22,25,26; 4 in the Americas16,17,21,24; and 1 in Europe23. Four studies reported exclusively on patients undergoing hip arthroplasty19,22-24, 5 reported exclusively on patients undergoing knee arthroplasty17,18,20,25,26, and the remaining 2 included both procedures16,21.

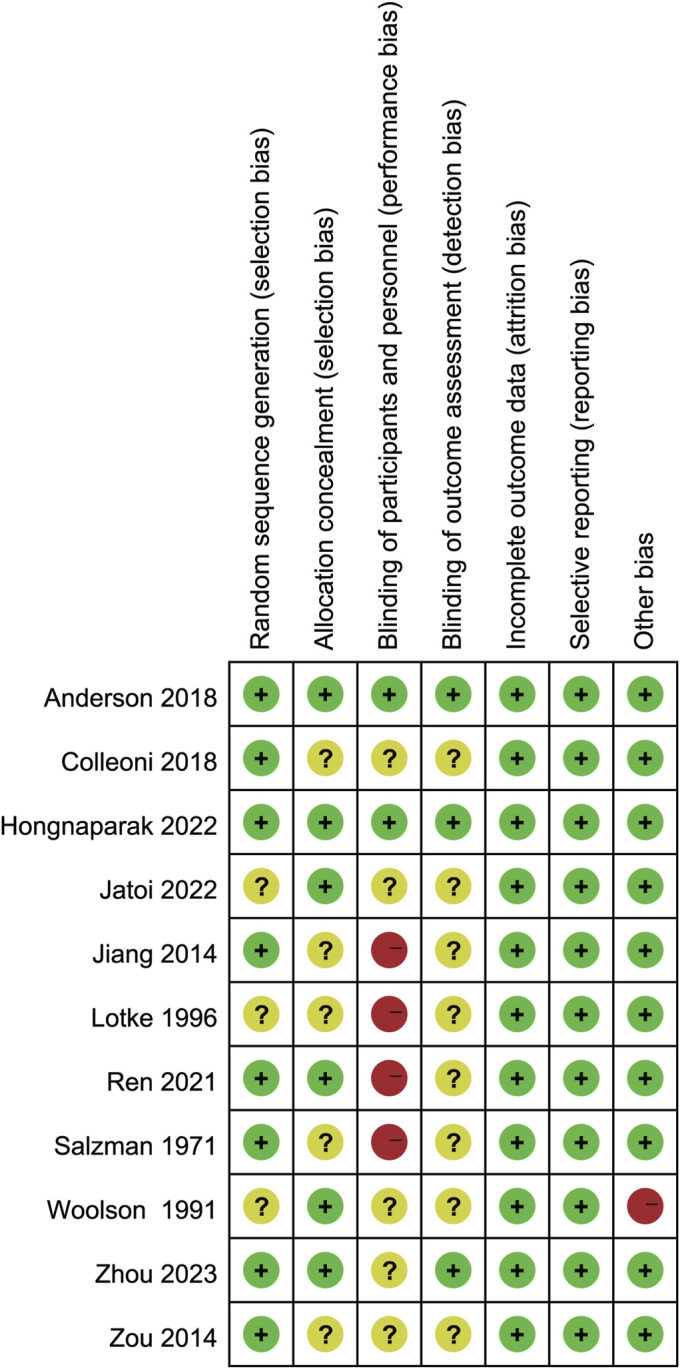

Study Quality

The quality of the included studies was assessed using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool. Five studies were of low quality20-24, 4 were of moderate quality17,19,25,26, and 2 were of high quality16,18. The primary sources of bias were the blinding of participants and personnel (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Risk-of-bias summary: the review authors’ judgments regarding each risk-of-bias item for each included study.

Primary VTE Outcomes

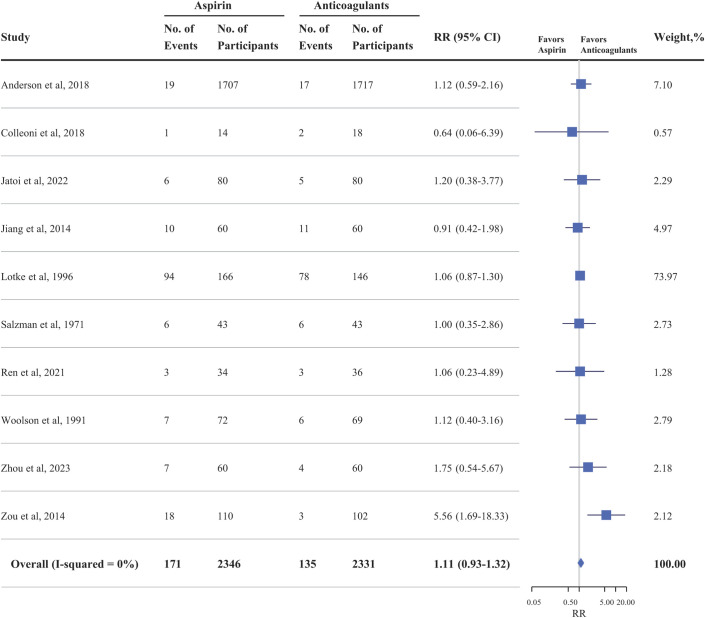

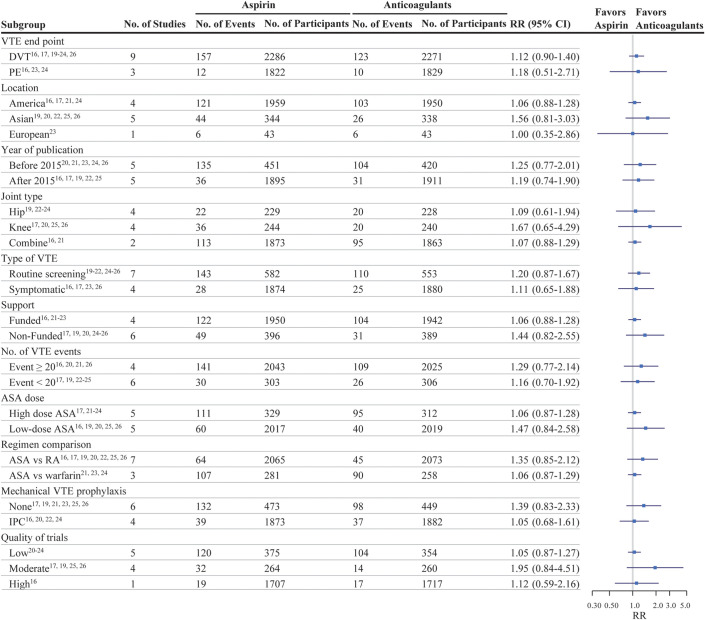

In the entire cohort16,17,19-26, the risk of VTE following joint replacement surgery was not significantly different in patients treated with aspirin compared with OACs (RR, 1.11; 95% CI, 0.93 to 1.32; p = 0.255) (Fig. 3). There was no heterogeneity among the included studies (I2 = 0%, p = 0.455). After excluding the trial with the greatest weight, which contributed most of the data to the analysis and was based on a noninferiority design21, the pooled result remained consistent (RR, 1.25; 95% CI, 0.89 to 1.75; I2 = 0%; p = 0.202). The pooled risk of DVT (9 studies16,17,19-24,26) among the patients treated with aspirin was not significantly different compared with that of the OAC group (RR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.90 to 1.40; I2 = 4.4%; p = 0.299) (Fig. 4). Similarly, there was no difference in the risk of PE (3 studies16,23,24) in the aspirin group compared with the OAC group (RR, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.51 to 2.71; I2 = 0%; p = 0.700) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Effectiveness of aspirin compared with oral anticoagulants with respect to the rate of venous thromboembolism (deep vein thrombosis plus pulmonary embolism) in randomized controlled trials of patients undergoing joint arthroplasty.

Fig. 4.

Effectiveness of aspirin (ASA) compared with oral anticoagulants with respect to the rate of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in randomized clinical trials of patients undergoing joint arthroplasty, grouped according to study-level characteristics. DVT = deep vein thrombosis, PE = pulmonary embolism, RA = rivaroxaban, IPC = intermittent pneumatic compression.

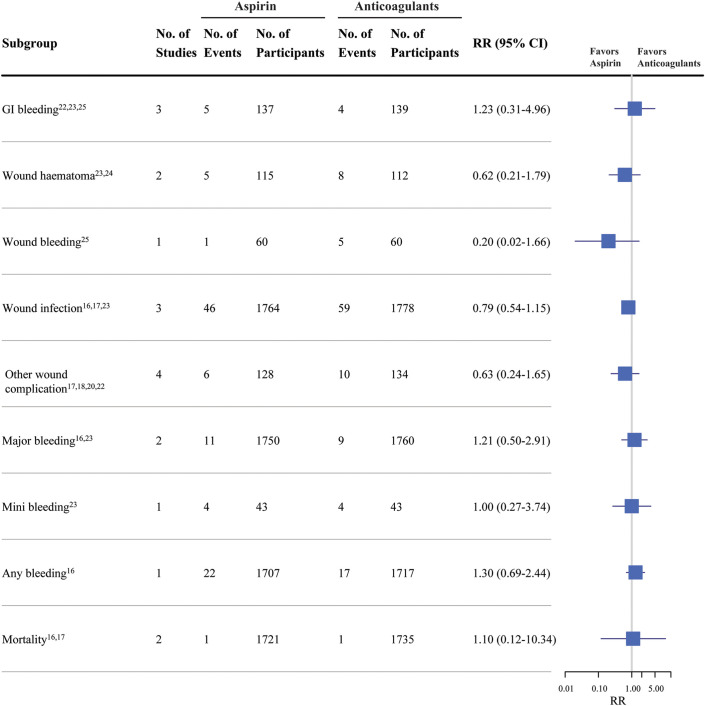

Complications

Reports of complications included gastrointestinal bleeding (3 studies22,23,25), wound hematoma (2 studies23,24), wound bleeding (1 study25), wound infection (3 studies16,17,23), other wound complications (4 studies17,18,20,22), major bleeding (2 studies16,23), minor bleeding (1 study23), any bleeding (1 study16), and mortality (2 studies16,17). The pooled results showed no significant differences in complications between patients using aspirin and those using OACs following joint arthroplasty (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Safety of aspirin compared with oral anticoagulants with respect to the rate of complications in randomized controlled trials of patients undergoing joint arthroplasty. GI = gastrointestinal.

Subgroups

We conducted subgroup analyses that considered several potential confounding variables to gain a more comprehensive understanding of our primary results. These variables included the country where the trial was conducted, type of joint surgery (knee arthroplasty, hip arthroplasty, or combined), VTE identification type (detected by routine screening or symptomatic), publication year, use of mechanical VTE prophylaxis (yes or no), aspirin dose (low or high), number of VTE events (<20 or ≥20), type of OAC comparator (rivaroxaban or warfarin), study quality (low, moderate, or high), and funding (yes or no). There was no indication that any of these study-level characteristics affected the difference in VTE between aspirin and OACs (Fig. 4).

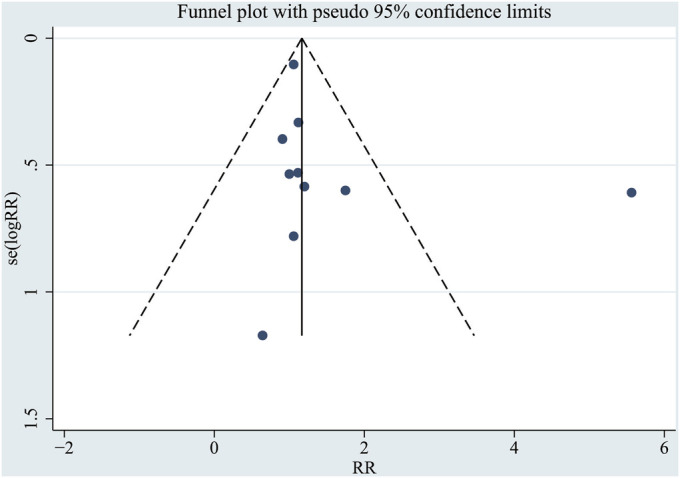

Publication Bias

For VTE, the only comparison that included ≥10 studies, visual inspection of the Begg funnel plot revealed symmetry (Fig. 6). This finding was supported by the Egger regression symmetry test, which also indicated no significant evidence of publication bias (p = 0.598).

Fig. 6.

Funnel plot for publication bias in studies reporting VTE rates. se = standard error.

Sensitivity Analysis

The results were not significantly affected by the deletion of any of the individual studies.

GRADE Ratings

The GRADE ratings for the 2 pooled analyses that included ≥5 studies, VTE and DVT, indicated that the quality of evidence was high for both (Table II).

TABLE II.

GRADE Summary of Findings*

| Outcome | Anticipated Absolute Effect†, per 1,000 | Relative Risk (95% CI) | No. of Participants (RCTs) | GRADE Certainty of the Evidence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk with Direct Oral Anticoagulant | Risk with Aspirin (95% CI) | ||||

| VTE | 58 | 64 (54 to 76) | 1.11 (0.93 to 1.32) | 4,677 (10) |

High‡ High‡

|

| DVT | 54 | 61 (49 to 76) | 1.12 (0.90 to 1.40) | 4,557 (9) |

High‡ High‡

|

GRADE = GRADE Working Group grade of evidence, CI = confidence interval, RCT = randomized controlled trial, VTE = venous thromboembolism, DVT = deep vein thrombosis. High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

The risk in the aspirin group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

Concerns existed about bias in the domain of allocation concealment.

Discussion

The meta-analyses of the efficacy and safety of aspirin versus OACs administered to prevent VTE following joint arthroplasty included 11 RCTs. The primary outcome analysis revealed no significant difference in the incidence of VTE in the aspirin group compared with the OAC group (RR, 1.11; 95% CI, 0.93 to 1.32), and no differences in DVT and PE. Previous meta-analyses, such as that by Zheng et al., reported a higher incidence of VTE with aspirin than with OACs in patients undergoing total joint replacement or hip surgery27, which likely differs from our results because the high heterogeneity of the included studies led to biased results. Our findings are consistent with those of Matharu et al. and Singjie et al.7,28. However, Singjie et al. included patients undergoing major orthopaedic lower-limb surgery, without a subgroup analysis of joint arthroplasty28. Matharu et al. included patients who underwent joint arthroplasty but compared aspirin with other oral and injectable anticoagulants7. The comparison of injectable medications and oral aspirin is challenging to anonymize, leading to lower study quality. In contrast, our primary analysis compared the efficacy of aspirin and OACs in patients who underwent joint arthroplasty. The comparison among oral medications facilitated blinding, resulting in higher-quality evidence. Matharu et al. did include a subgroup analysis of aspirin versus rivaroxaban (3 studies, 3,855 participants)7; however, our study included 11 RCTs with 4,717 patients, providing a broader range of studies and a larger sample size, and conducted a comprehensive analysis of aspirin versus OACs.

Additionally, we thoroughly assessed the methodological quality of the included studies. We conducted a rigorous analysis by systematically exploring potential sources of heterogeneity across various study-level characteristics and testing for evidence of effect modification. We also compared bleeding, wound complications, and mortality between the aspirin and OAC groups, and found no significant differences. These adverse-event findings were based on data from only a few studies, and some estimates were imprecise; therefore, these results should be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, the RCTs exhibited heterogeneity in the study populations (particularly hip and/or knee arthroplasty). However, formal subgroup analyses confirmed that study-level characteristics, including study region, type of joint surgery, VTE identification type, publication year, use of mechanical VTE prophylaxis, aspirin dose, study quality, and funding, did not influence the main findings. The quality of evidence for both VTE and DVT was rated as high.

Our results align with those of large observational cohort studies, which have shown that aspirin is effective in preventing VTE and offers efficacy and safety comparable to, or slightly better than, other common anticoagulants6,29. Thus, the current evidence supports the use of aspirin for VTE prophylaxis after joint replacement surgery. The American College of Chest Physicians guidelines has assigned a grade of 1B to their recommendation for the use of aspirin as a postoperative anticoagulant10, and aspirin has become an essential agent for DVT prevention following joint replacement surgery. Compared with other anticoagulants, aspirin is cost-effective8,9, does not require coagulation monitoring, and is convenient to use. Aspirin can cause gastrointestinal side effects30, which have limited its clinical use. However, our study did not observe an increased incidence of complications associated with aspirin use. Furthermore, the treatment cost is a crucial factor to consider. The daily cost of 20 mg of rivaroxaban is more than 300 times that of 325 mg of aspirin31. Aspirin is an affordable option preferred by public and private health-care systems to reduce costs while achieving similar outcomes. It can be used in patients with renal impairment, does not increase the risk of major bleeding intraoperatively, and can be reversed with platelet transfusions.

Strengths and Limitations

Previous studies have been conducted on the use of aspirin for preventing VTE, including comparisons of LMWH with aspirin and aspirin with a placebo. However, no meta-analyses have compared aspirin with OACs. Our pooled results showed essentially no heterogeneity, with the highest I2 value being 4.4%, and the conclusions were robust in all sensitivity analyses and subanalyses. The GRADE evidence level was high, indicating that it provides meaningful guidance for clinical practice. We used a thorough and rigorous search strategy encompassing multiple databases without language restrictions. By exclusively including RCTs, we eliminated the selection bias associated with observational studies. We also performed a thorough evaluation of the methodological quality of the included studies. We conducted a thorough analysis by systematically investigating the potential sources of heterogeneity across various study-level characteristics and testing for evidence of effect modification. Notably, our analyses included only patients undergoing joint arthroplasty, addressing the limitations we have noted in previous trials and systematic reviews.

Despite the high level of evidence, however, this study has some limitations, most of which are inherent to meta-analyses. First, only 2 of the included studies reported blinding of both participants and outcome assessors, 5 did not specify the blinding status of at least 1 of these, and the remaining 4 failed to blind at least 1 of these, resulting in a notable risk of bias. Second, differences in the patient inclusion and exclusion criteria used in the included studies may have led to heterogeneity in the study populations. Third, differences in drug dosage and duration, reported outcomes (such as the results of routine VTE screening versus symptomatic VTE), use of mechanical VTE prophylaxis, and follow-up times across the included studies could have resulted in biased outcomes. These factors were evaluated in the sensitivity analyses; however, they may still have resulted in biased estimates. Fourth, the reporting of adverse events appeared to be selective, as these data were reported in only a few of the included studies, potentially leading to a loss of power in demonstrating associations that did exist.

Conclusions

On the basis of existing evidence from RCTs, no significant differences were found in the clinical efficacy of aspirin compared with OACs with respect to the prevention of VTE, including DVT and PE, after joint arthroplasty. Additionally, aspirin did not increase the incidence of complications. The body of evidence was of high quality. Nonetheless, more large-scale, well-designed RCTs would be beneficial to strengthen these findings.

Appendix

Supporting material provided by the authors is posted with the online version of this article as a data supplement at jbjs.org (http://links.lww.com/JBJS/I368).

Footnotes

Zhenghua Hong, MD, and Yongwei Su, MM, contributed equally to this work.

Investigation performed at Taizhou Hospital of Zhejiang Province, Taizhou, Zhejiang, People’s Republic of China

Disclosure: This work was supported by Enze Medical Center (Group) Scientific Research (No. 23EZA04) and Zhejiang Medicine and Health Scientific Research Project (No. 2024KY531). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation. The Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest forms are provided with the online version of the article (http://links.lww.com/JBJS/I369).

Contributor Information

Zhenghua Hong, Email: z17826759237@126.com.

Yongwei Su, Email: suyongwei0826@163.com.

Liwei Zhang, Email: zhanglw3972@enzemed.com.

References

- 1.Nicholson M, Chan N, Bhagirath V, Ginsberg J. Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism in 2020 and Beyond. J Clin Med. 2020. Aug 1;9(8):2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pastori D, Cormaci VM, Marucci S, Franchino G, Del Sole F, Capozza A, Fallarino A, Corso C, Valeriani E, Menichelli D, Pignatelli P. A Comprehensive Review of Risk Factors for Venous Thromboembolism: From Epidemiology to Pathophysiology. Int J Mol Sci. 2023. Feb 5;24(4):3169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piple AS, Wang JC, Kang HP, Mills ES, Mayfield CK, Lieberman JR, Christ AB, Heckmann ND. Safety and Efficacy of Rivaroxaban in Primary Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2023. Aug;38(8):1613-1620.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Runner RP, Shau DN, Staley CA, Roberson JR. Utilization Patterns, Efficacy, and Complications of Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis Strategies in Revision Hip and Knee Arthroplasty as Reported by American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery Part II Candidates. J Arthroplasty. 2021. Jul;36(7):2364-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faour M, Piuzzi NS, Brigati DP, Klika AK, Mont MA, Barsoum WK, Higuera CA. Low-Dose Aspirin Is Safe and Effective for Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis Following Total Knee Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018. Jul;33(7S):S131-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simon SJ, Patell R, Zwicker JI, Kazi DS, Hollenbeck BL. Venous Thromboembolism in Total Hip and Total Knee Arthroplasty. JAMA Netw Open. 2023. Dec 1;6(12):e2345883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matharu GS, Kunutsor SK, Judge A, Blom AW, Whitehouse MR. Clinical Effectiveness and Safety of Aspirin for Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis After Total Hip and Knee Replacement: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2020. Mar 1;180(3):376-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cortes-De la Fuente AA, Villalobos-Campuzano C, Bucio-Paticio B, Valencia-Martínez G, Martínez-Montiel O. [Comparative study between enoxaparin and salicylic acetyl acid in antithrombotic prophylaxis for patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty]. Acta Ortop Mex. 2021. Mar-Apr;35(2):163-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gelfer Y, Tavor H, Oron A, Peer A, Halperin N, Robinson D. Deep vein thrombosis prevention in joint arthroplasties: continuous enhanced circulation therapy vs low molecular weight heparin. J Arthroplasty. 2006. Feb;21(2):206-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falck-Ytter Y, Francis CW, Johanson NA, Curley C, Dahl OE, Schulman S, Ortel TL, Pauker SG, Colwell CW, Jr. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012. Feb;141(2)(Suppl):e278S-325S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JA; Cochrane Bias Methods Group; Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011. Oct 18;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA. (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.5. 2024. Accessed 2024 Dec 5. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook [Google Scholar]

- 13.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021. Mar 29;372(71):n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Chandler J, Welch VA, Higgins JP, Thomas J. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019. Oct 3;10(10):ED000142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, Norris S, Falck-Ytter Y, Glasziou P, DeBeer H, Jaeschke R, Rind D, Meerpohl J, Dahm P, Schünemann HJ. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011. Apr;64(4):383-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson DR, Dunbar M, Murnaghan J, Kahn SR, Gross P, Forsythe M, Pelet S, Fisher W, Belzile E, Dolan S, Crowther M, Bohm E, MacDonald SJ, Gofton W, Kim P, Zukor D, Pleasance S, Andreou P, Doucette S, Theriault C, Abianui A, Carrier M, Kovacs MJ, Rodger MA, Coyle D, Wells PS, Vendittoli PA. Aspirin or Rivaroxaban for VTE Prophylaxis after Hip or Knee Arthroplasty. N Engl J Med. 2018. Feb 22;378(8):699-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colleoni JL, Ribeiro FN, Mos PAC, Reis JP, Oliveira HR, Miura BK. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after total knee arthroplasty (TKA): aspirin vs. rivaroxaban. Rev Bras Ortop. 2017. Dec 6;53(1):22-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hongnaparak T, Janejaturanon J, Iamthanaporn K, Tanutit P, Yuenyongviwat V. Aspirin versus Rivaroxaban to Prevent Venous Thromboembolism after Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Double-blinded, Randomized Controlled Trial. Rev Bras Ortop (Sao Paulo). 2021. Oct 25;57(5):741-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jatoi FS, Buriro MH, Ali S, Younis M, Ahmed F, Munir A. Comparison of the Efficacy of Aspirin with Rivaroxaban in Postoperative DVT Prophylaxis after Hip Arthroplasty in patients at tertiary care hospital. Pakistan Journal of Medical and Health Sciences. 2022;16(5):18-21. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang Y, Du H, Liu J, Zhou Y. Aspirin combined with mechanical measures to prevent venous thromboembolism after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Chin Med J (Engl). 2014;127(12):2201-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lotke PA, Palevsky H, Keenan AM, Meranze S, Steinberg ME, Ecker ML, Kelley MA. Aspirin and warfarin for thromboembolic disease after total joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996. Mar;(324):251-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ren Y, Cao SL, Li Z, Luo T, Feng B, Weng XS. Comparable efficacy of 100 mg aspirin twice daily and rivaroxaban for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis following primary total hip arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Chin Med J (Engl). 2021. Jan 5;134(2):164-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salzman EW, Harris WH, DeSanctis RW. Reduction in venous thromboembolism by agents affecting platelet function. N Engl J Med. 1971. Jun 10;284(23):1287-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woolson ST, Watt JM. Intermittent pneumatic compression to prevent proximal deep venous thrombosis during and after total hip replacement. A prospective, randomized study of compression alone, compression and aspirin, and compression and low-dose warfarin. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991. Apr;73(4):507-12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou LB, Wang CC, Zhang LT, Wu T, Zhang GQ. Effectiveness of different antithrombotic agents in combination with tranexamic acid for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and blood management after total knee replacement: a prospective randomized study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023. Jan 4;24(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zou Y, Tian SQ, Wang YH, Liu JJ, Sun K. Administration of aspirin and rivaroxaban prevents deep vein thrombosis after total knee arthroplasty. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research. 2014;18(13):2012-7. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng X, Nong L, Song Y, Han L, Zhang Y, Yin Q, Bian Y. Comparison of efficacy and safety between aspirin and oral anticoagulants for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after major orthopaedic surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Front Pharmacol. 2024. Jan 8;14:1326224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singjie LC, Halomoan R, Saleh I, Sumargono E, Kholinne E. Clinical effectiveness and safety of aspirin and other anticoagulants for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after major orthopedic surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. EFORT Open Rev. 2022. Dec 21;7(12):792-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coveney EI, Hutton C, Patel N, Whitehouse SL, Howell JR, Wilson MJ, Hubble MJ, Charity J, Kassam AM. Incidence of Symptomatic Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) in 8,885 Elective Total Hip Arthroplasty Patients Receiving Post-operative Aspirin VTE Prophylaxis. Cureus. 2023. Mar 21;15(3):e36464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Devereaux PJ, Mrkobrada M, Sessler DI, Leslie K, Alonso-Coello P, Kurz A, Villar JC, Sigamani A, Biccard BM, Meyhoff CS, Parlow JL, Guyatt G, Robinson A, Garg AX, Rodseth RN, Botto F, Lurati Buse G, Xavier D, Chan MT, Tiboni M, Cook D, Kumar PA, Forget P, Malaga G, Fleischmann E, Amir M, Eikelboom J, Mizera R, Torres D, Wang CY, VanHelder T, Paniagua P, Berwanger O, Srinathan S, Graham M, Pasin L, Le Manach Y, Gao P, Pogue J, Whitlock R, Lamy A, Kearon C, Baigent C, Chow C, Pettit S, Chrolavicius S, Yusuf S; POISE-2 Investigators. Aspirin in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2014. Apr 17;370(16):1494-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinazzi BJ, Kirchner GJ, Stauch CM, Lorenz FJ, Manto KM, Bonaddio V, Koroneos Z, Aynardi MC. Cost-Effective Modeling of Thromboembolic Chemoprophylaxis for Total Ankle Arthroplasty. Foot Ankle Int. 2022. Oct;43(10):1379-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]