Abstract

Blood-oxygenation-level-dependent (BOLD) functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has revolutionized our understanding of the brain activity landscape, bridging circuit neuroscience in animal models with noninvasive brain mapping in humans. This immensely utilized technique, however, faces challenges such as acoustic noise, electromagnetic interference, motion artifacts, magnetic-field inhomogeneity, and limitations in sensitivity and specificity. Here, we introduce Steady-state On-the-Ramp Detection of INduction-decay with Oversampling (SORDINO), a transformative fMRI technique that addresses these challenges by maintaining a constant total gradient amplitude while acquiring data during continuously changing gradient direction. When benchmarked against conventional fMRI on a 9.4T system, SORDINO is silent, sensitive, specific, and resistant to motion and susceptibility artifacts. SORDINO offers superior compatibility with multimodal experiments and carries novel contrast mechanisms distinct from BOLD. It also enables brain-wide activity and connectivity mapping in awake, behaving mice, overcoming stress- and motion-related confounds that are among the most challenging barriers in current animal fMRI studies.

Keywords: fMRI, tissue oxygen, cerebral blood volume, functional connectivity, brain networks, T1 contrast, rat, mouse, awake, behavior, social, acoustic noise, electromagnetic interference, motion artifacts, susceptibility artifacts, sensitivity, specificity

For nearly three decades, gradient-recalled echo (GRE)-based echo-planar imaging (EPI) has been the gold standard in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), largely due to its ability to rapidly acquire whole-brain volumes with T2* sensitivity to the blood-oxygenation-level-dependent (BOLD) contrast1–3 — a broadly utilized marker of brain activity4–6. However, despite its widespread use, this technique has several limitations: (1) acoustic noise7–9, (2) electromagnetic interference10–14; (3) artifacts related to ghosting, motion, and magnetic field inhomogeneity3,15; (4) lower sensitivity compared to other neuroimaging modalities16–18; and (5) poor spatial specificity due to its bias toward venous vasculature19,20. Overcoming these limitations would be groundbreaking for the growing rodent fMRI community6,21–23, where key challenges include: (a) acoustic noise from GRE-EPI that forces the use of anesthesia24,25, compromising brain function and limiting translational relevance to human fMRI; (b) stress and motion confounds that plague awake rodent fMRI studies unless extensive habituation protocols are implemented26–33; and (c) susceptibility artifacts in GRE-EPI that present under the high magnetic field strengths (> 7T) typically used in rodent studies22,34,35.

“Zero” acquisition delay imaging sequences, such as zero echo time (ZTE), RUFIS, PETRA, and MB-SWIFT, primarily known for structural MRI applications36–38, acquire data just a few microseconds after RF pulsing and offer potential solutions to some of the challenges faced in fMRI. In these sequences, imaging gradients ramp to a plateau, and center-out frequency-encoding spokes capture the free-induction-decay (FID) induced by RF pulses under steady gradients. The data from multiple radially oriented spokes are then reconstructed to form images. With proper encoding trajectories and the ZTE feature, these sequences are inherently less susceptible to acquisition-related acoustic noise, electromagnetic interference, and artifacts36,37. Although some of these zero acquisition delay techniques have been adapted for fMRI39–43, they still face a critical limitation: none have demonstrated robust sensitivity compared to the gold standard GRE-EPI. This lack of sensitivity hinders their broader adoption, as the compromised sensitivity requires compensation with more experimental repetitions or larger sample sizes. Additionally, due to their extremely short acquisition delays, these sequences are inherently insensitive to T2- or T2*-weighted BOLD contrast, highlighting the need to better understand alternative fMRI contrast mechanisms for functional neuroimaging.

In this study, we address several major barriers in fMRI, including acoustic noise, electromagnetic interference, ghosting, motion, susceptibility artifacts, sensitivity, and specificity by introducing a novel fMRI technique: Steady-state On-the-Ramp Detection of INduction-decay with Oversampling (SORDINO), named for its analogy to the muting of a musical instrument. Unlike existing ZTE techniques acquire data only on steady gradients, SORDINO takes a fundamentally different approach and further improves the benefits of zero-acquisition-delay sequences: it maintains constant gradient amplitudes throughout the entire sequence while continuously changing the gradient direction, providing minimal acoustic noise and gradient-related artifacts and maximal sensitivity by acquiring data exclusively during the gradient ramps. We benchmarked SORDINO against GRE-EPI and ZTE on a high-field preclinical MRI system (9.4T), demonstrated SORDINO’s exceptional compatibility with simultaneous electrophysiology, electrochemistry or calcium imaging at cellular resolution, modeled and revealed its contrast mechanisms for functional neuroimaging, and showcased its ability to measure brain-wide resting-state connectivity in awake mice. Furthermore, we demonstrated that SORDINO facilitates experiments that are otherwise highly challenging, if not impossible, including mapping naturalistic circuit activity in behaving, head-fixed mice and simultaneously imaging two mouse brains during social interactions. Our findings suggest that SORDINO offers robust sensitivity and is a transformative technique for functional brain mapping, particularly suited for subjects that cannot tolerate acoustic noise or are susceptible to magnetic field inhomogeneity and motion artifacts. Through this work, we release the SORDINO sequence and its corresponding database, providing the field with an accessible resource to enable new research opportunities and further technical advances.

RESULTS

SORDINO sequence

To date, no MRI technology has achieved imaging by clamping both total gradient amplitude (GTotalAmp) and gradient angular change (α) throughout the entire duration of a scan. Our creation of SORDINO started with one very simple thought: MRI scans produce loud acoustic noise due to vibrations in the gradient coils driven by rapidly switching electrical currents, and this is also the source of many Eddy-current-related artifacts, including ghosting and distortion in EPI. Thus, the question arises: How can we efficiently distribute the gradient changes needed for a 3D encoding without ever resetting the gradient? Following this thought, we identified the simplest strategy to achieve 3D encoding with the lowest possible α. The sequence requires a one-time initialization at the start of an fMRI experiment, as depicted in Figure 1a & Figure S1a. Following this initialization, both GTotalAmp and α remain constant throughout the entire acquisition (i.e., dGTotalAmp/dt=0 and dα/dt=0). This condition is held not only across all encoding datapoints within an imaging volume, but also across all volumes (i.e., all time points) during an fMRI experiment. An analogy for SORDINO’s gradient control to existing radial sampling methods is akin to the smooth, continuous motion of a modern clock’s second hand versus the discrete, ticking motion of a traditional clock. While the gradient direction constantly changes, we apply a phase-incrementing, spatially non-selective RF pulse to induce the FID signal while reducing spurious echoes (Figure S1b). Given the presence of the gradient field, the FID naturally realizes “frequency encoding” in the form of a curved, center-out k-space line (i.e., a spoke). Acquiring data during the ramping gradient incurs no noticeable penalty (Figure S1c&d). Figure 1b provides a conceptual representation of the spoke evolution in the 2D plane, illustrating that the end of each spoke points towards the beginning of the next spoke. Figure 1c & Video 1 visually demonstrate the precise gradient trajectory employed in SORDINO, where the last spoke of one volume aligns seamlessly with the first spoke of the next volume. This strategy ensures a constant, minimal change in gradient direction, eliminating the need for resets. This straightforward approach results in an ultra-low slew rate for fMRI (0.21 T/m/s), which is four orders of magnitude lower than EPI (1263.62 T/m/s) and nearly one hundred times lower than other 3D zero-acquisition-delay sequences such as ZTE or MB-SWIFT (15.66 T/m/s) at identical spatiotemporal resolution (see Methods for parameter details). Furthermore, by eliminating traditional gradient ramping and settling times (Figure S1a) while incorporating an oversampling anti-aliasing strategy (Figure S1e&f), SORDINO can achieve a lower bandwidth and maximize acquisition time, which translates directly to improved signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and having fewer datapoints that fall within the T-R switch dead time (Figure S1g–i) compared to other short acquisition delay fMRI methods. Further details for the SORDINO sequence are presented in Methods.

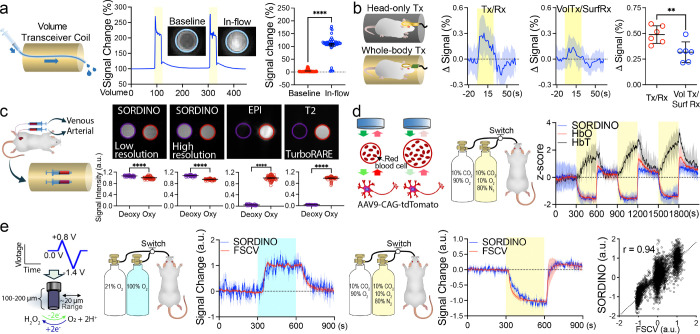

Figure 1. SORDINO sequence and modeling of its functional contrast.

(a) In SORDINO, the gradient changes constantly at an angular change rate α and has an extremely low slew rate, thus eliminating acoustic noise and Eddy current artifacts. Data acquisition commences exclusively and continuously throughout the non-stop gradient ramping, thus enhancing SNR. In this conceptual plot, dark green datapoints represent acquisition at nominal bandwidth and light blue datapoints represent the oversampled digitized datapoints. (b) Conceptual spoke evolution in a 2D plane, showing multiple curved spokes in k-space. (c) SORDINO gradient trajectory in 3D. (d) In the case of using a head-only excitation coil, the measured voxel signal is comprised of a mixture of stationary tissue and transient blood signal. Bloch equation simulations show that magnetization of stationary tissue reaches a steady-state within a few seconds (green dashed line), whereas the blood signal (red line) does not reach a steady-state at the time of measurement due to the short blood transit time, as fresh arterial blood would experience fewer RF excitations. Specific parameters for these simulations are detailed in Methods. (e) CBV contributions at the voxel level, considering: arterial transit time = 280 ms, baseline blood flow = 10 mm/s, local flow acceleration = 1.5 mm/s, activation radius = 1 mm, blood/tissue volume fraction = 5%, and CBV increase = 20%. Regionally accelerated blood would be subjected to 13 fewer RF-pulses and heightened the blood signal, resulting in a robust increase in SORDINO signal. (f) tO2 contribution at the voxel level: a physiological 30 μM transient increase in tissue oxygen corresponds to a 32 ms decrease in T1 from a baseline of 1900 ms (oxygen T1 relaxivity is 0.3 mM−1s−1.) The tO2-induced T1-shortening results in a measurable increase in the SORDINO-fMRI signal, taking approximately 1 s to establish a new steady-state. (g) The relationship between T1 changes and SORDINO-fMRI contrast is nearly linear across a range of gray matter T1 values (see Methods for detailed calculations).

SORDINO Contrast Modeling

First, we conducted a series of modeling experiments to explore a range of possible parameters capable of producing contrasts in response to T1 changes. These models served as a foundation as we examined the impact of specific signal modulators within the rodent brain at 9.4T: inflow-enhanced cerebral blood volume (CBV) and alterations in tissue oxygen levels. Conventionally, the inflow effect observed in fMRI is primarily attributed to the apparent T1 shortening resulting from incoming spins that experience few or no RF pulses44,45, which generates a stronger signal compared to that from stationary tissue44. When using SORDINO with head-only RF excitation, frequent RF pulsing rapidly leads the magnetization of stationary tissue to a steady-state (Figure 1d, green dashed line); however, inflowing arterial blood experiences fewer RF pulses, resulting in a higher signal compared to static tissue (Figure 1d, red line and blue vertical dash line). Collectively, the combined voxel signal stabilizes at a steady-state when the blood transit time and CBV remain stable (Figure 1d–f, blue dashed lines). We subsequently modeled the effect of activation-induced increases in CBV. Given that the blood signal is higher than the tissue (see Figure 1d, blue vertical dash line), an increase in vascular-space-occupancy46,47 translates into positive changes in the SORDINO signal (Figure 1e). Figure S2a & b display a series of raw SORDINO images of a rat brain in live and postmortem conditions, respectively. These images also feature the robust CBV contrast in the live condition as predicted when using a head-only coil for RF excitation. Raw SORDINO images across distinct spatial resolutions are shown in Figure S2c.

Next, we evaluated the influence of alterations in tissue oxygen (tO2) levels. Guided by invasive tO2 ground-truth measurements48 and prior studies revealing the relationship between molecular oxygen concentration and T1 relaxation rate (R1)49. We estimated that changes in tO2 contribute to SORDINO contrast to a similar order of magnitude as CBV (Figure 1f). Given the well-documented spatial specificity of tO2 and CBV metrics50–52, SORDINO emerges as a compelling alternative to GRE-EPI BOLD-fMRI (vide infra). Furthermore, it’s worth noting that SORDINO contrast exhibits linearity across a spectrum of T1 values in both the rodent brain at 9.4T and the human brain at 3T, and this characteristic positions SORDINO to accurately map brain activity across the physiological range of T1 changes (Figure 1g). In addition to using a head-only coil for RF excitation, we explored SORDINO contrast when employing a whole-body coil for RF excitation. Our findings indicate that, in this scenario, tO2 becomes the dominant contributor to SORDINO contrast, while CBV increases result in slight negative changes due to the longer T1 of blood compared to brain tissue (Figure S3).

SORDINO Acquisition Parameters and Sampling Efficiency

To examine our operational hypothesis regarding the use of SORDINO for fMRI, it is imperative to model the efficacy of SORDINO parameter selection in delineating T1-related functional activation and to validate these parameters in vivo (Figure S4). In Figure S4a–c, we display various combinations of repetition time (TR) and flip angle (FA). While a shorter spoke-TR constrains T1 recovery, it allows more spokes to be acquired within a fixed volume-TR (Figure S4d). We thus considered an efficiency factor, calculated as the square root of spoke-TR53, to account for the influence of the number of spokes acquired within a fixed volume-TR. In Figure S4e–f, we present the outcomes of Bloch equation modeling, which estimates the efficiency of SORDINO acquisition. Our modeling reveals that different TR-FA combinations yield varying levels of sensitivity to T1 changes, and that FA ranging from 2° to 5° offer optimal efficiency when maintaining a spoke-TR between 0.6 and 2.4 ms (Figure S4g). To validate these modeling results, we conducted experiments using a forepaw stimulation task in rats, assessing five different TR-FA combinations. The detected functional activations in vivo (Figure S4h), as determined through contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) analysis, qualitatively aligns with the modeled SORDINO imaging efficiency (Figure S4g).

SORDINO versus GRE-EPI

Next, we benchmarked SORDINO against the gold-standard GRE-EPI across various metrics, including acoustic noise, electromagnetic interference, ghosting, distortion, susceptibility artifacts, motion artifacts, sensitivity, and specificity. To ensure a fair comparison, we configured the SORDINO and EPI parameters to achieve identical spatial and temporal resolution (see Methods for detailed parameter settings).

Negligible Acoustic Noise:

SORDINO demonstrated exceptional proficiency in mitigating acoustic noise, as illustrated in Figure 2a. Across the recorded frequency range (0–15 kHz), the sound pressure level (SPL) profile for SORDINO closely follows the scanner’s idle state. In comparison to SORDINO, the SPL is up to 20 dB higher in EPI and 5 dB higher in ZTE. This acoustic noise reduction in SORDINO holds the potential for significant benefits in awake animal fMRI, where it can alleviate subject stress and reduce habituation time (Figure 2b&c). Specifically, in our experimental conditions, we found that head-fixed awake mice subjected to longitudinal SORDINO experiments exhibited elevated cortisol levels only on the first day of imaging, with cortisol level decreasing on Day 3 and showing no significant deviation from the baseline on Day 5. This stands in stark contrast to awake mice undergoing GRE-EPI scans, which consistently displayed heightened cortisol levels throughout the measured time points (Figure 2b). This reduction in stress was also evident in the subjects’ body weight changes over time (Figure 2c).

Figure 2. SORDINO versus EPI.

(a) Comparison of acoustic noise induced by active SORDINO, ZTE, and EPI scanning against the scanner idle state. SORDINO effectively eliminates gradient-related acoustic noise, enabling silent imaging (n = 10 trials; one-way ANOVA, F(2,1499) = 20694, p-values are from Tukey’s HSD). (b, c) Mice undergoing a five-day head-fixation habituation process exhibit reduced stress hormone levels (Serum Cortisol: n = 49 baseline, n =32 SORDINO and n = 6 EPI; One-Way ANOVA;, F(6,156) = 38.79, p < 0.0001; p-values are from Tukey’s HSD) and maintain body weight in the SORDINO group but not in the EPI group (n = 15 SORDINO; Repeated Measures one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni multiple comparison test, effect of MRI sequence, F(1.87,26.10) = 6.76, p = 0.005; n = 6 EPI; Repeated Measures one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni multiple comparison test, effect of MRI sequence, F(1.45,7.26) = 12.65, p = 0.006. (d) Spike simulator and dummy cell setup for quantifying electromagnetic interference. (e) Electrophysiological recordings in MRI with and without active SORDINO, ZTE, and EPI scanning show that SORDINO significantly reduces electromagnetic interference, enabling online sorting of simulated neuronal spiking signals without additional pre-processing. (f) Electrochemical recording using fast-scan cyclic voltammetry in MRI demonstrates that SORDINO allows real-time recording without requiring the interleaved recording approach previously reported for EPI. Results are presented as the mean oxidation current recorded at 0.65V vs. Ag/AgCl reference electrode with the corresponding range. (g) SORDINO’s versatility supports the placement of a calcium miniscope above the mouse head, enabling unprecedented real-time calcium imaging at cellular resolution during brain-wide fMRI. Calcium activities from 103 neurons in the prelimbic cortex (PrL) are displayed during SORDINO off and on periods. (h) Active SORDINO scanning does not compromise calcium imaging quality, as indicated by consistent mean intensity and peak amplitude measurements. (i) Ghosting artifacts are absent in SORDINO compared to EPI (n = 19 independent trials; two-tailed paired t-test, t(18) = 1006.18, p < 0.0001). (j) Using Cartesian-sampled spin-echo data as the ground truth, SORDINO shows no structural distortion compared to EPI (n = 60 measurements; two-tailed paired t-test, t(59) = 21.26, p < 0.0001). (k) In vivo comparison of SORDINO and EPI images from the same subject under identical shimming reveals reduced susceptibility artifacts in several regions, including the amygdala (arrowheads). (l) Regional homogeneity (ReHo) analysis on resting-state data indicates preserved local correlation in susceptibility artifact-prone regions with SORDINO, while EPI shows nearly zero ReHo in these regions (n = 9; two-tailed paired t-test, t(8) = 7.49, p = 0.0003). (m) Passive forelimb movement created by using a box-design in a deeply anesthetized mouse demonstrates that SORDINO drastically reduces motion-correlation artifacts. (n) Correlation histograms depict brain voxels with strong positive and negative correlations to the motion paradigm in EPI, which are absent in SORDINO. (o) Six motion parameters and FD extracted from resting-state SORDINO and EPI acquisitions show that SORDINO is immune to motion confounds (n = 30 subjects; two-tailed paired t-test between all parameters: t(29) = 1.36 – 7.60, p < = 0.0000–0.19; Two-tailed paired t-test between groups in FD: t(29) = 10.53, p < 0.0001). (p) SORDINO demonstrates robust sensitivity compared to GRE-EPI-BOLD using a within-subject, within-session design at identical spatiotemporal resolution (n = 16 subjects, 80 unique trials; linear mixed effects model, β = 0.82, p < 0.0001). (q) tSNR in the somatosensory cortex comparison from resting-state SORDINO data (n = 9). The higher tSNR in SORDINO allows the rather small T1-related changes to be detected. (r) SORDINO demonstrates comparable resting-state FC measurement to GRE-EPI-BOLD. FC variation and spatial reliability are measured using seed-based analysis, leveraging the intrinsic homotopic FC feature in the somatosensory cortex across hemispheres. Randomly sampled time-series data lengths (100 random selections per length) highlight the comparable time needed to depict reliable FC compared to the full data length. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 and ****p<0.0001 compare with SORDINO, baseline, or indicated groups; #p<0.05 and ####p<0.0001 compare with indicated groups. ns, not significant.

Ultra-low Electromagnetic Interference:

We performed electrophysiological and electrochemical recordings (fast-scan cyclic voltammetry, FSCV)48 during active MRI scanning. These experiments were performed in vitro, allowing the measurement of repeatable ground-truth signals generated by a spike signal simulator without confounders such as physiological noise (Figure 2d–f). Remarkably, due to the absence of transient gradient switching, SORDINO exhibited minimal gradient-induced artifacts in spike recording, which did not hinder the ability to identify spikes using a conventional online sorting approach (Figure 2e). Additionally, there was no noticeable difference in FSCV readout between SORDINO off and on states (Figure 2f). These are in sharp contrast to GRE-EPI and ZTE, where the induced artifacts have long been a barrier to continuous and real-time measurement of these electrical based physiological signals during fMRI. This drastically reduced electromagnetic interference also enables the new capability of acquiring calcium imaging data at cellular resolution using a head-mounted miniscope during simultaneous fMRI (Figure 2g & Video 2). Analysis of calcium signal dynamics during SORDINO off and on periods showed no significant differences in calcium imaging quality (Figure 2h).

Minimized Ghosting, Distortion, Susceptibility, and Motion Artifacts:

Using an established analysis approach54, we showed the lack of ghosting in SORDINO (Figure 2i). We also assessed spatial distortion by comparing data against Cartesian-sampled turbo spin echo (TurboRARE) images, showing the lack of distortion in SORDINO compared to EPI (Figure 2j). To compare susceptibility artifacts in SORDINO and EPI, we presented raw images in Figure 2k, highlighting areas that are typically most prone to air-tissue interface dephasing and signal drop out in EPI, which are preserved in SORDINO. To further evaluate the impact of susceptibility artifacts, we analyzed resting-state data to generate regional homogeneity (ReHo) images55, demonstrating measurable ReHo in regions that are challenging to assess by EPI (Figure 2l). In addition, we remotely induced passive limb movements in deeply anesthetized mice by pulling a nylon monofilament string (Figure 2m & Video 3) and demonstrated a marked reduction in unwanted motion-induced correlation in SORDINO compared to EPI (Figure 2n). Further, we performed SORDINO and EPI scans in two groups of awake mice and extracted motion parameters from the time-series data. Our results demonstrated a significant decrease in motion parameters and framewise displacement (FD) using SORDINO (Figure 2o).

Robust Sensitivity:

Using an established forepaw electrical stimulation task in rats, we assessed the contrast-to-noise-ratio (CNR) against baseline standard deviation and presented data in z-scores. SORDINO consistently demonstrated a robust sensitivity to functional activation within the primary somatosensory cortex (S1) of the forepaw region. The CNR was comparable, if not superior, to that of EPI (Figure 2p). In another cohort of subjects, we also compared forepaw-evoked responses obtained from SORDINO and GRE-EPI under different conditions and acquisition parameters, demonstrating comparable CNR (Figure S5). Further, our analysis of time series data from the rat brain revealed a higher tSNR with SORDINO (Figure 2q). Moreover, we benchmarked the efficiency of SORDINO for resting-state FC measurement by performing seed-based analysis to calculate FC variation and spatial reliability of the somatosensory homotopic FC pattern. These results, presented as a function of randomly sampled time-series data lengths (100 random selections for each length to compute the mean and standard deviation), illustrated the relationships between input fMRI volumes and FC measures using both sequences (Figure 2r). These data suggest that SORDINO maintains sensitivity comparable to GRE-EPI BOLD-fMRI while offering additional benefits.

Specific Contrast Origin:

Our modeling demonstrates that SORDINO is sensitive to CBV (Figure 1e) and tO2-induced T1 changes (Figure 1f). We conducted five experiments to empirically validate these contrasts and confirm that SORDINO does not carry conventional BOLD contrast. In Figure 3a, we present data from a flowing phantom inside an RF coil. The inflowing spins, owing to their initial full magnetization and the fewer RF excitations they receive before signal readout (see Figure 1d & S2), generate higher signals than those at steady-state, thereby elevating SORDINO signals. This characteristic sets the foundation to measure CBV changes, as increased CBV introduces more inflowing spins, enhancing imaging voxel signals due to higher vascular-space-occupancy46,47. In Figure 3b, we dissect the fraction of CBV contributions in SORDINO by comparing forepaw sensory stimulation evoked responses in rats under two coil settings: head-only excitation versus whole-body excitation. Whole-body excitation yielded approximately 40% weaker evoked responses than head-only excitation, consistent with our modeling predictions (see Figure 1e & f and S3). In this setting, the whole-body excitation eliminates inflow-related vascular signal enhancement, causing all blood in the subject to reach a steady-state, similar to gray matter tissue (see Figure S3a). As a result, any inflowing blood contribution would be minimal and negatively affect the overall SORDINO responses due to the slightly longer T1 of blood compared to tissue.

Figure 3. SORDINO contrast mechanisms.

(a) SORDINO demonstrates sensitivity to inflowing spins, enabling arterial CBV contrast in vivo (n = 1 trial; 383 volumes at baseline and 52 during inflow; two-tailed unpaired t-test, t(433) = 51.08, p < 0.0001). (b) Whole-body RF excitation, compared to head-only RF excitation, eliminates CBV contributions but retains 60% of signal changes during forepaw stimulation, suggesting the presence of functional contrast mechanisms beyond CBV (n = 6 subjects; two-sided paired t-test, t(5) = 2.57, p = 0.049). (c) SORDINO lacks hemoglobin-related “BOLD” contrast. While SORDINO shows positive responses to forepaw stimulation-induced activation in S1 (see Figures 2p, S5, and 3b), deoxygenated hemoglobin exhibits stronger SORDINO signals than oxygenated hemoglobin under SORDINO-fMRI parameters (left; n = 69 datapoints; two-tailed unpaired t-test, t(13) = 11.27, p < 0.0001) and anatomical scans with long spoke TR (right; n = 69 datapoints; two-tailed unpaired t-test, t(13) = 34.27, p < 0.0001). In contrast, conventional BOLD effects are reliably observed in EPI (n = 69 datapoints; two-tailed unpaired t-test, t(13) = 92.73, p < 0.0001) and T2-weighted scans (n = 69 datapoints; two-tailed unpaired t-test, t(13) = 126.10, p < 0.0001). These findings indicate that SORDINO relies on contrast mechanisms distinct from BOLD. Notably, most (~99%) oxygen in blood is bound to hemoglobin, with minimal dissolved oxygen present. This makes the molecular oxygen effects negligible in this measurement. (d, e) Validation of SORDINO’s sensitivity to tissue oxygenation changes was achieved through concurrent fiber photometry and FSCV recordings. (d) Under hypercapnic conditions, hypoxic gas challenges resulted in increased CBV and decreased blood and tissue oxygenation, as measured by fiber photometry. The SORDINO signal closely tracked oxyhemoglobin changes rather than total hemoglobin levels, highlighting its sensitivity to non-BOLD, yet oxygen-related contrasts. Yellow boxes indicate the hypoxic gas challenge periods (n = 4, 3 unique trials per subject). (e) SORDINO signal changes aligned with concurrently recorded tissue oxygenation ground-truth measurements using FSCV. Left: In a hyperoxic gas challenge experiment, SORDINO signals mirrored the dynamics of tissue oxygenation (blue box indicates the hyperoxic period). Middle: During hypoxic gas challenges, SORDINO signals also closely matched tissue oxygenation changes (yellow box indicates the hypoxic period). Right: The scatter plot demonstrates a strong correlation between SORDINO signals and tissue oxygen levels (n = 3, 3 trials per animal). Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. **p<0.01 and ****p<0.0001 compared with indicated groups.

In Figure 3c, we imaged freshly collected arterial and venous blood samples using SORDINO, GRE-EPI, and TurboRARE sequences. While the latter two sequences exhibited the typical “BOLD effects”, with higher signals in oxygenated arterial blood, SORDINO showed reversed contrast, with higher signals in deoxygenated venous blood than the oxygenated arterial blood. This contrast inversion likely arises from SORDINO’s insensitivity to paramagnetic T2* effects of deoxyhemoglobin and its efficiency in capturing the T1 shortening effects of deoxyhemoglobin56. These findings indicate that positive evoked responses in SORDINO (see Figure 2p) are not due to intravascular hemoglobin oxygenation levels, suggesting a potential solution to address the low spatial specificity and the unwanted draining vein dominance commonly seen in BOLD-fMRI20,57–59. In Figure 3d, we conducted a gas-challenge experiment with head-only RF excitation to dissociate tO2 from CBV. We strategically established a hypercapnic-hyperoxic baseline (10% CO2 and 90% O2), followed by a hypoxic challenge (10% CO2 and 10% O2), leading to decreased oxygenation and increased CBV. These physiological changes were validated by simultaneous measurements of SORDINO signals (head-only RF excitation), oxyhemoglobin, and total hemoglobin concentration changes (indicative of CBV) using an established fiber photometry technique60. The single-voxel SORDINO signals, taken at the tip of the implanted optical fiber in the cerebral cortex, closely aligned with oxygenation changes rather than total hemoglobin, featuring SORDINO’s sensitivity to non-BOLD (Figure 3c), yet oxygen-related contrast (Figure 3d). To further demonstrate the tO2 effects in vivo, in Figure 3e, we showcase another gas-challenge experiment, inducing positive (21% O2 baseline followed by 100% O2 hyperoxic challenge) and negative (10% CO2 and 90% O2 hyperoxic baseline followed by 10% CO2 and 10% O2 hypoxic challenge) tissue oxygen changes while concurrently acquiring SORDINO (head-only RF excitation) and FSCV-derived ground-truth tissue oxygen data61–63 – a setup enabled by SORDINO’s minimal gradient-induced artifacts. The single-voxel SORDINO signals at the tip of the implanted FSCV electrodes tightly coupled with tissue oxygen levels in both conditions, highlighting its robustness in detecting tissue oxygen changes. Given that oxygen is predominantly released at capillaries and arterioles64, in close proximity to the source of neuronal activity19, and that free molecular oxygen typically diffuses less than 30 μm from vascular sources65, SORDINO holds potential to offer improved spatial specificity over GRE-EPI BOLD-fMRI.

SORDINO for Resting-State fMRI in Awake Mice

To demonstrate the feasibility of SORDINO for mapping functional connectivity in awake mice, we designed a dual-functional headplate coil using dielectric PCB-board material with insulated coil traces. The coil functions as the RF transceiver while also supporting the fixation of the mouse head. Figure 4a shows an awake mouse fitted with the coil on its head, without restraining its body or limbs. All subjects underwent a five-day habituation process, as shown in Figure 2c. We evaluated the effects of nuisance signal removal using a pipeline detailed in the Methods section (Figure 4b–d). Following pre-processing, we first performed a seed-based analysis by placing seeds in the left S1 and RSC, both of which revealed functional connectivity patterns as expected24,27,66. We then assessed the reliability and specificity of this SORDINO dataset in measuring functional connectivity (Figure 4g–i) and used independent component analysis (ICA) to extract large-scale brain networks. Figure 4j illustrates the representative “triple-networks”, comprising the default mode network (DMN), the lateral cortical network (LCN), and the salience network (SN) of the mouse brain67, which are critical in neuropsychology and related disorders68–76. To effectively depict large-scale functional networks and illustrate the SORDINO-derived functional connectome of the awake mouse brain, we transformed the SORDINO data into the Allen Mouse Brain Atlas space77. This transformation facilitates direct comparisons between SORDINO-derived functional connectivity and the structural connectivity ground truth provided by the Allen Brain Atlas (Figure 4k). The stress-free, distortion-free functional connectome data presented here hold promise for future comparative studies and represent a valuable resource for the neuroimaging community.

Figure 4. SORDINO for functional connectome mapping in awake mice.

(a) Mouse wearing a custom headplate coil in a 3D-printed cradle for functional connectivity mapping in awake condition. (b) Distribution of FD data from all subject time-courses, representing FD values across every time point and displayed as a log-scale density histogram (n = 25). SORDINO data were acquired at 400 μm isotropic spatial resolution and 2 s temporal resolution, continuously for 900 volumes. The effects of nuisance removal across all subject time-courses are shown in (c) D-variate temporal standard deviation (DVARS) histogram, (d) scatterplot between FD and DVARS, and (e) tSNR histogram. (f) Voxel-wise seed-based connectivity maps from the left S1 (green) and RSC (blue) seeds across all subjects (n = 25) are shown using a second-level permutation method thresholded at p < 0.01 (FWE-corrected) and r > 0.3. (g) A Gaussian/Gamma mixture model was fitted to characterize the distribution of seed-based connectivity map. Voxels with low connectivity to the seed region were modeled by the Gaussian component (blue), while voxels with high connectivity with seed region were modeled by the Gamma component (red). (h) A probability curve was computed to identify the boundary between the Gaussian (blue) and Gamma (red), and the resulting boundary values were used as thresholds for determining functional specificity. (i) Functional connectivity specificity scatter plot showing the distribution of individual subject specificity data, defined as homotopic S1 functional connectivity across hemispheres (mirroring the seed shown in (f), expected to be high in a robust dataset) relative to S1-RSC functional connectivity (expected to be low in a robust dataset). Subjects in the upper left quadrant exhibit high functional connectivity specificity, while the other three quadrants represent unspecific functional connectivity, spurious functional connectivity, and no functional connectivity. (j) ICA-derived “triple-network” patterns in awake mice. Coronal sections show the intrinsic large-scale networks including, DMN, LCN, SN. (k) Functional connectivity measured in awake mice undergoing SORDINO (n = 25) and analyzed using Allen Brain Mouse Brain ROIs is shown in the lower left of the matrix, while the Allen Atlas structural connectivity pattern is displayed in the upper right of the matrix, illustrating the functional-structural relevance of the mouse brain connectome. N1: Limbic and Associative Network, N2: Sensorimotor-Cognitive Integration Network, N3: Hippocampal-Prefrontal Associative Network, N4: Retrosplenial and Visual Network, N5: Somatosensory and Motor Network, N6: Primary Sensory Network, N7: Associative Visual Network, N8: Prefrontal Cognitive Network, N9: Limbic Emotional Network, N10: Motivational and Memory Network. N11: Visual and Entorhinal Network. N12: Subcortical Limbic Network. N13: Thalamic Relay Network.

SORDINO for Mapping Skilled Motor Actions in Mice

Motion artifacts and stressful acoustic noise often confine conventional rodent fMRI studies to passive sensory stimulation experiments. In principle, SORDINO’s motion-insensitive (Figure 2m–o) and acoustically silent features (Figure 2a–c) provide a unique opportunity to map complex active behaviors with fMRI. To test this capability, we designed a pneumatically driven food pellet delivery system (Figure 5a) and trained mice to reach and grasp a food pellet using their forepaw once every 20 s under a head-fixed condition, with imaging data acquired by the same dual-functional head fixation transceiver coil plate mentioned earlier. This task requires delicate coordination of activity across the brain and triggers a motor sequence actively initiated and executed by the subjects (Figure 5b & Video 4), rather than relying on passive stimulations typically seen in most rodent fMRI studies. Figure 5c–e depicts the brain-wide activity changes and time-courses from various ROIs. The data revealed that system-level motor network activity consistently initiated in the contralateral motor cortex, with concurrent deactivation found in the retrosplenial cortex (RSC), a key hub of the DMN known to deactivate during task performance71. Subsequently, we observed robust activation in the bilateral sensory-motor cortices, dorsolateral striatum, thalamus, and cerebellum, followed by a return to baseline, reflecting behavior-related activity changes in these brain regions. Notably, the activation patterns identified with SORDINO closely align with brain regions known to play a causal role in the control of voluntary limb movements in mice78–84. This represents the first whole-brain map of a dexterous motor behavior in the rodent and demonstrates that SORDINO can map active behaviors, once considered extremely challenging, if not impossible, for conventional fMRI sequences.

Figure 5. SORDINO for mapping skilled motor actions.

(a) Custom pneumatic system enables grabbing task performance in head-fixed mice. (b) Mice perform reach-and-grasp tasks during SORDINO-fMRI. (c-e) Brain-wide activity maps and time-courses show consistent motor cortex activation and retrosplenial cortex deactivation, followed by subsequent activation of thalamus, cerebellum, and sensory cortices (n = 4, in the total of 24 fMRI sessions with 75–100 grabbing events per session). A linear mixed-effects model is utilized to compare the activity at time = 0, 2, and 4 s to the baseline (averaged activity at time = −6, −4, and −2). Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. (*p<0.05).

SORDINO for Cross-Brain Coupling during Mouse Social Behavior

Leveraging SORDINO’s resistance to magnetic field inhomogeneity and motion problems, we have developed a platform that enables simultaneous imaging of two mouse brains during social behavior. This platform includes a 3D-printed cradle that mounts two awake mice face-to-face, separated by a divider plate that can be remotely withdrawn from outside the MRI scanner room (Figure 6a & Video 5). Each mouse is mounted with a head fixation plate coil, whereby RF pulses are individually transmitted and signals are received from each coil, enabling dual-brain “hyperscanning” of two socially interacting mice (Figure 6b). Upon removal of the divider plate, the subjects immediately display signs of social behavior, most notably in the form of increased whisking (Video 5). SORDINO data showed transient activations in the RSC, prelimbic (PrL), and cingulate (Cg) cortices of the DMN, and the anterior insula (AI) of the SN, peaking at 4 s; and deactivations in the M1 and the S1 forepaw (S1FL) and whisker (S1BF) regions of the LCN, peaking at 8 s (Figure 6c). With the divider in place, no significant inter-brain correlation was detected; however, upon its removal, mirrored inter-brain connectivity emerged in the RSC, Cg, PrL, and AI, suggesting synchronization of activity dynamics between the two brains (Figure 6d). Further ROI analysis revealed significant inter-brain, cross-region connectivity among M1, DMN, and SN nodes after divider removal, with no inter-brain connectivity observed during the period of having the divider in place (Figure 6e). Divider removal also induced a significant increase in mean cross-brain spatial correlation within the DMN and SN (Figure 6f). Voxel-wise analysis demonstrated consistent inter-brain synchronization within the DMN and SN regions, aligning with the partner’s RSC, Cg, PrL, AI, and M1, but not with their S1 (Figure 6g). This pattern suggests that inter-brain synchronization arises from perceiving the partner’s actions and broader brain states, which may be influenced by M1 activity but are not necessarily driven by M1 alone. Altogether, our results demonstrate a novel platform that opens new avenues for measuring and manipulating inter-brain communications, offering exciting possibilities for advancing neuroimaging research.

Figure 6. Mapping inter-brain synchronization in awake, socially interacting mice using SORDINO hyperscanning.

(a) A 3D-printed cradle holds mice face-to-face, initially separated by a remotely retractable divider, enabling dual-brain SORDINO-fMRI hyperscanning. (b) A SORDINO image with an extended FOV along the gradient z-axis, showing the actual distance between the brains of two subjects. (c) SORDINO hyperscanning captured brain responses during social encounters initiated by divider removal (n = 22, grouped in 11 pairs, averaged signal change map, threshold = ±0.6%). Following divider removal, activations peaked at 4 s in DMN nodes (RSC, Cg, PrL) and the AI of the SN, followed by deactivations peaking at 8 s in LCN nodes (M1, S1FL, S1BF). (d-f) Inter-brain synchronization emerged only in socially interacting mice without the divider. (d) Mirrored inter-brain connectivity appeared in RSC, Cg, PrL, and AI post-divider removal (n = 11 pairs, one-sample t-test, p < .01), absent during baseline. (e) ROI analysis showed significant inter-brain connectivity among DMN, SN, and M1 only after divider removal, as illustrated in the right chord diagram (top and bottom hemispheres represent individual brains of paired mice, n = 22, one-sample t-test, p < 0.001, FDR corrected with Benjamini-Hochberg procedure). (f) Spatial correlation analysis indicated enhanced inter-brain synchrony of activation patterns within DMN and SN post-divider removal. (Left: spatial correlation distribution across pre- or post-divider-removal time period; Right: mean spatial correlation within subjects, pre- and post-divider-removal, n = 11 pairs, paired t-test, p < .001). (g) SORDINO signals within DMN and SN regions showed significant inter-brain synchronization with the socially interacting partner’s RSC, Cg, PrL, AI, and M1, but not with the partner’s S1 (n = 22, one-sample t-test, p < .001). AI, anterior insula; AUD, auditory cortex; BLA, basolateral amygdala; Cg, cingulate cortex; CLA, claustrum; Hipp, hippocampus; IL, infralimbic cortex; M1, motor cortex; Orb, orbitofrontal cortex; PrL, prelimbic cortex; RSC, retrosplenial cortex; S1, somatosensory cortex; V1, visual cortex.

SORDINO for Mouse Glymphatic Dynamics

In addition to fMRI, we conducted two proof-of-concept studies to demonstrate SORDINO’s ability to robustly capture T1 changes using paramagnetic manganese ion (Mn2+) and gadolinium-based (Gd) contrast agents. We first modeled the contrast gain in SORDINO at 9.4T, considering a 50% of T1-shortening effect (i.e., from 1900 ms to 950 ms), which is commonly observed in manganese-enhanced MRI (MEMRI) studies85–90. Our modeling suggests that, with proper selection of imaging parameters, SORDINO signals are expected to be 1.8-fold stronger with manganese enhancement (Figure S6a). By comparing SORDINO images from the same mouse before and 7 days after subcutaneous osmotic mini-pump infusion of MnCl2 at a total dose of 175 mg/kg89, we demonstrated a robust enhancement of the SORDINO signal in key regions known to exhibit Mn2+ uptake. These regions include the pituitary gland, hippocampus, cerebellum, and olfactory bulb, consistent with findings in classical MEMRI studies85–90 (Figure S6b, Video 6). Next, we showcased SORDINO’s ability to rapidly image brain-wide cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) influx into the brain parenchyma using an intra-cisterna magna injection of Gd contrast (Prohance, 0.067 mM, 10 μL) – a protocol increasingly used to evaluate the glymphatic system dynamics, which are critical for brain waste clearance91,92. Upon Gd injection, we observed an immediate increase in SORDINO signals in the cisterna magna, followed by the fourth ventricle, third ventricle, lateral ventricle, and cortical regions (Figure S7, Video 7). A reversal in contrast was observed in the ventricles, where they initially appeared darker than gray matter but became brighter than gray matter following Gd injection (Figure S7a). These pronounced contrast changes significantly enhanced the identification of regions where Gd was distributed. In a Cartesian-sampled FLASH sequence at minimal TE (Figure S7b), the regions surrounding the injection site experienced signal loss due to susceptibility artifacts and/or high concentration Gd-related T2* shortening, whereas the SORDINO sequence did not show this artifact. This enabled brain-wide signal normalization to the cisterna magna following Gd injection (Figure S7c), thereby controlling data variability associated with injection volume variations during microinjection. Looking ahead, the silent feature of SORDINO offers the potential to image glymphatic flow without the confounding effects of anesthesia93. This advancement enables future investigations of the glymphatic function in both awake and naturalistic sleep conditions, thereby enhancing translational relevance to human and clinical populations known to exhibit glymphatic deficits.

DISCUSSION

We introduce an innovative method named Steady-state On-the-Ramp Detection of INduction-decay signal with Oversampling, or SORDINO in short. Drawing from musical terminology, SORDINO signifies the muting and damping of vibrations in instruments, reflecting the features this technique provides in MRI. We evaluated SORDINO alongside GRE-EPI on various metrics, dissected SORDINO functional contrast, and demonstrated its efficacy in imaging rodent brain function in awake and behaving conditions. These studies suggest SORDINO to be a powerful technique that is silent, sensitive, specific, and resilient to artifacts commonly seen in GRE-EPI, enabling new opportunities for functional brain mapping during active behavior.

SORDINO’s technical features

SORDINO is silent and can minimize electromagnetic interference because rapid switching of gradient polarity and gradient resetting are absent. Within an fMRI experiment, we clamp the total gradient amplitude constant, continuously rotate gradient direction, and employ a trajectory design to yield consistent and minimal gradient directional changes, never needing to reset the total gradient amplitude to zero (Figure 1). These features allow SORDINO to achieve an ultra-low slew rate, effectively eliminating acoustic noise and reducing subjects’ stress (Figure 2a–c), while also minimizing electromagnetic interference, as evidenced by electrophysiological and electrochemical recordings (Figure 2d–f). Currently, most simultaneous electrophysiology-fMRI studies rely heavily on post-processing and/or regression of MRI-induced noise. Our findings highlight the potential of SORDINO to facilitate simultaneous, real-time electrophysiological/electrochemical recordings during fMRI, paving the way for future close-loop studies. Additionally, the feasibility of performing cellular resolution calcium imaging during SORDINO-fMRI (Figure 2g) holds promises for bringing novel insights into cellular mechanisms underlying large-scale brain networks.

SORDINO is resistant to ghosting, distortion, susceptibility, and motion artifacts. Building on a 3D radial sampling strategy, SORDINO densely samples information around the k-space center, thereby distributing the energy of transient motion into thousands of encoding directions. Imaging sequences such as PROPELLER94 or other center-out encoding schemes95–97 have shown great promise in reducing ghosting and motion artifacts. As shown in Figure 2, SORDINO inherits these artifact-resisting properties for fMRI applications. Further, SORDINO encodes data immediately after RF excitation, leaving essentially no time for voxel dephasing. Since all datapoints are sampled using frequency encoding within a very short readout time, the phase deviation from encoding is minimized and the bandwidth is uniform along all encoded spokes. This also renders SORDINO insensitive to geometric distortion, enabling studies of brain regions susceptible to field inhomogeneity, such as amygdala in the rodent brain66,98,99 (Figure 2k&l). Consequently, this minimizes image distortion caused by field inhomogeneity in vulnerable brain regions, thereby reducing compounded errors typically encountered during rigid-body registration-based motion correction.

The most efficient sequence for mapping functional activations should minimize the time spent on contrast preparation while maximizing the time available for data acquisition. SORDINO represents a great example of this concept by acquiring data throughout the entire TR (Figure S1a). Specifically, it provides robust sensitivity to functional activation through several innovative strategies employed. First, imaging extremely short T2* species using a high acquisition bandwidth is not necessary for brain fMRI applications (Figure S1h). Therefore, SORDINO exclusively samples data on-the-ramp to afford very low bandwidth acquisition within an extremely short TR (e.g., 0.6 ms for all awake mouse studies presented in this work). Such a short TR is unattainable with conventional sequences because high acquisition bandwidth is necessary to rapidly encode the entirety of k-space between each RF pulse repetition in EPI66 or to accommodate multiple excitations for single spoke encoding in sequences such as MB-SWIFT39,40. Importantly, our data has demonstrated robust CNR compared to GRE-EPI (Figure 2), supporting the feasibility of achieving additional sensitivity gain with SORDINO. In addition, compared to other short-acquisition-delay sequences that rely on high acquisition bandwidth, the low bandwidth strategy affordable by SORDINO can improve SNR and reduce missing samples at the center of k-space (Figure S1).

SORDINO demonstrates robust sensitivity to tO2 or combined CBV and tO2 changes depending on the RF delivery strategy, setting it apart from the conventional BOLD contrast, which is heavily influenced by hemoglobin oxygenation levels1–6. The insensitivity to deoxyhemoglobin’s paramagnetic effects, together with the high spatial specificity of tO219,64 and CBV changes58,100, suggests that SORDINO can offer more precise localization of neuronal activity by minimizing the influence of draining veins, a common issue in BOLD-fMRI6,19. By testing head-only and whole-body RF coil excitation settings within the same scanning session, we were able to examine the CBV contribution to SORDINO signals under head-only RF excitation. The experiments demonstrated that head-only RF excitation can approximately double the fMRI response amplitude by capitalizing on the inflow arterial signal enhancement. While this is beneficial for improving data acquisition efficiency, this extra sensitivity gain may be dependent on the blood transit times. For instance, it has been shown that the frontal brain regions generally exhibit a transit time delay of approximately 0.04 s compared to posterior brain regions101. This highlights the need for future studies to thoroughly investigate how region-dependent blood transit times may influence SORDINO sensitivity. In both simultaneous photometry-fMRI and FSCV-fMRI experiments, we observed SORDINO’s sensitivity to oxygenation, which aligns well with the modeled T1 shortening effects of molecular oxygen. Given that oxygen is predominantly released at capillaries and arterioles near neuronal activity sites19,64, SORDINO’s responses are likely to originate from regions closer to the sources of neuronal activity than BOLD-fMRI. It should be noted that while SORDINO offers significant advantages, its application in very high temporospatial resolution laminar fMRI studies remains challenging. This is primarily due to the use of nonselective RF pulses and SORDINO’s 3D imaging nature, which would require impractically long imaging times if resolution were substantially increased. While undersampling can help mitigate prolonged imaging times, a high undersampling factor introduces artifacts (Figure S8). In this work, we focus on demonstrating the feasibility of SORDINO and providing a fair comparison against EPI, while leaving the exploration of acceleration options and regularized reconstruction approaches for future studies. Translating SORDINO to human MRI systems where multi-channel coils enable additional acceleration options, could be critical for further demonstrating its capabilities and spatial specificity.

Given that tissue T1 increases at higher magnetic field strengths while the molecular oxygen relaxivity remains relatively unchanged102, we expect SORDINO to perform better at higher magnetic fields (Figure S9). This enhanced sensitivity to T1-shortening effects, alone with the known SNR benefits from increased polarization of spins and reduced thermal noise103, highlights the potential utility of SORDINO at high magnetic fields. fMRI applications at high field strengths often face challenges such as susceptibility artifacts, eddy currents, and difficulties encoding shortened T2* signals in time – problems to which SORDINO is relatively immune.

SORDINO applications

SORDINO represents a transformative tool for conducting fMRI studies in awake mice, offering unprecedented opportunities to map brain function during resting-state, naturalistic behaviors, social interactions, and glymphatic dynamics, previously constrained by the limitations of conventional MR methods. In a series of four proof-of-concept studies, we demonstrated that SORDINO enabled FC mapping in awake mice with significantly reduced habituation time from the month-long process typically required27–29 to just 5 days. We attribute this improvement from SORDINO’s elimination of the acoustic noise and gradient vibration inherent in conventional EPI-fMRI, which necessitate extended habituation to mitigate stress in the animals. The shortened habituation period aligns with what is observed in head-fixed optical imaging studies, where the animals do not encounter noisy environments and have the ability to move104–107. SORDINO’s streamlined FC mapping significantly enhances the accessibility of awake rodent fMRI to the broader research community. This development is particularly impactful given that much of current rodent fMRI is still performed under anesthesia24 – a limitation that the field is keen to overcome.

We demonstrated that SORDINO effectively images brain activity during a forepaw-reaching task in mice using a custom-designed, MR-compatible food pellet delivery system. This capability to capture active, voluntary behavior overcomes traditional challenges of fMRI in moving subjects, enabling naturalistic fMRI studies of motor behavior-driven brain activity changes. SORDINO’s insensitivity to electromagnetic interference further allows for seamless integration of complementary modalities, facilitating circuit-based behavior augmentation or piloting novel therapies for movement and mental disorders while establishing their causality to brain networks. Additionally, we extended SORDINO’s application to simultaneous imaging of two mouse brains during social behavior, revealing cross-brain coupling in large-scale brain networks. This platform paves the way for novel research opportunities, such as using closed-loop setups to record and feed signals between subjects while simultaneously imaging brain-wide activity. The ability to study vocalization and communication between subjects without the confounding effects of MRI-related acoustic noise also offers exciting potential for advancing knowledge of these sophisticated behaviors. Further, we showcased SORDINO’s versatility beyond traditional fMRI applications by mapping the glymphatic system, which is gaining significant attention for its role in neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders. Using Gd contrast, SORDINO provided clear, artifact-free imaging of CSF influx, distinct from traditional methods that suffer from susceptibility artifacts and Gd-related T2 shortening. The silent imaging features of SORDINO are particularly advantageous for studying glymphatic flow in awake, sleep, and naturalistic conditions, a significant step forward in understanding glymphatic system’s role in brain health without confounds associated with anesthesia.

CONCLUSION

We describe the theoretical framework and implementation of SORDINO, identifying robust in vivo parameters and benchmarking them against modeled biophysical properties and various ground-truth validations. This work empirically demonstrates SORDINO’s sensitivity to tO2 and CBV, suggesting its spatial specificity, and highlights several novel applications enabled by this technique. The information, raw data, and sequences provided in this manuscript are intended to facilitate future use of SORDINO within the fMRI community and advance the exploration of functionally and behaviorally relevant brain circuits in awake animal subjects. This study pushes the boundaries of fMRI by offering a silent, sensitive, and specific method with reduced artifact interference. The insights gained here are anticipated to have broader implications beyond fMRI, with these benefits translating to dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI108,109 and molecular MRI110 studies in awake, behaving animal subjects.

METHODS

Male C57BL/6J mice (n = 147; 23–32 g), male Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 43; 232–500 g) were acquired from Charles River (Wilmington, MA, USA). Animals were given food and water ad libitum and kept on a 12-hour light/dark cycle. In addition to MRI, we integrated established neuroscience tools for recordings during SORDINO-fMRI. These tools included electrophysiology, FSCV, miniscope calcium imaging, and spectral-fiber photometry. Stock AAV vectors were purchased directly from Addgene. Given the variety of approaches used in this manuscript, we structured the methods into four main categories: (1) MRI hardware, sequence, and modeling, (2) Phantom experiments and SORDINO sequence characteristics, (3) Rat experiments, and (4) Mouse experiments. Methods within each category follow the order in which they are presented in the main text. Python (version 3.7) and the NumPy111, MATLAB (R2024a) and GraphPad Prism 10 were used for data analysis.

MRI Hardware, Sequence, and Modeling

All MRI experiments were performed on a Bruker 9.4 T/30 – cm horizontal bore system, with a BFG 240/120 gradient insert (Resonance Research Inc, Billerica, MA) and an AVNEO console, configured with a maximum gradient amplitude of 922 mT/m.

SORDINO sequence.

The SORDINO sequence demonstrated in this manuscript was programmed on Bruker ParaVision 6 and 360, building upon the default Bruker ZTE sequence. Software and hardware configuration remained unchanged between the two versions, ensuring consistent sequence performance throughout this work. The general framework of the single spoke acquisition in SORDINO is shown in Figure 1a. Following a one-time initialization of the encoding gradient, a short, hard RF-pulse is applied. This RF-pulse, lasting only a few μs, enables a short-acquisition delay.

Clamping the encoding gradient slew rate.

The primary aim of SORDINO was to develop a sequence with minimal gradient switching to minimize acoustic noise and electromagnetic interference. In MRI, fast switching currents induce Lorentz forces in the gradient coils, causing vibrations in the surrounding structures and resulting in the loud knocking sound characteristic of EPI. The rapidly varying magnetic fields induced by gradient switching generate concomitant currents in metallic components such as wires and electrode leads, making electrical recordings challenging without proper artifact regression or interleaving the MRI acquisition. Conventional ZTE realizes low gradient switching by ramping the encoding gradient before RF-application while keeping the gradient switched on throughout the acquisition, with only incremental adjustments in amplitude between spokes. By default, the ZTE gradient amplitude is adjusted over the configured ramp time, which was 0.21 ms on our system. SORDINO achieves a significantly lower slew rate than ZTE by nearly clamping the gradient slew rate constant throughout acquisition. This was accomplished by adjusting where the program initiates gradient ramping and extending ramp time to its maximum possible duration. However, uninterrupted ramping was not feasible on our system due to potential memory constraints with the sequencer. Instead, a 10 μs plateau was introduced between spokes before the gradient resumed ramping. The low slew rate strategy of SORDINO offers an additional potential benefit for fMRI. Enabling continuous ramping throughout acquisition eliminates delays associated with switching the gradient ramping on and off, allowing for a lower acquisition bandwidth. A reduced bandwidth proportionally decreases noise variance in the sampled data and increases SNR by reducing the thermal noise component of fMRI data112. Furthermore, since gradient strength decreases proportionally with receiver bandwidth, a lower bandwidth enables sampling closer to the center of k-space. This is because fixed delays in the sequence – such as RF-pulse duration, ADC initialization and coil ringdown – are independent of bandwidth.

RF-spoiling and pulse length.

Because our goal was to minimize gradient ramping and maximize acquisition duration, we did not employ gradient-spoiling in SORDINO. Instead, we used RF-spoiling wherein the phase of the RF-pulse was incremented by 117°, upon each repetition of the excitation pulse, which mixes transverse coherence pathways, reducing the formation of spurious echoes and the temporal variability of the signal113. In this manuscript, spurious echoes refer to unintended echo formation regardless of the mechanism. Throughout all experiments, we selected a 4 μs RF-pulse length as a compromise between minimizing the acquisition delay, ensuring RF power stability, and maintaining sufficient B1 homogeneity.

Spoke-oversampling.

On our system, the first sample in all SORDINO acquisitions was corrupted due to a digital filter group delay. With spoke-oversampling, each sample represents a smaller time step, meaning that the number of delayed samples corresponds to a shorter duration. This enables the acquisition of samples closer to the center of k-space, mitigating the impact of group delay on image quality. Since the reconstructed FOV is inversely proportional to sampling distance, oversampling provides the flexibility to reconstruct images that mitigate aliasing from unwanted signals outside the nominally prescribed FOV. This is particularly important for SORDINO, which is sensitive to signals from short-T2 materials, such as those from coil insulation materials (Figure S1h). All experiments described in this manuscript used an oversampling factor of 8 as a compromise between data size and mitigating the effect of digital filter group delay.

Comparison of gradient slew rates in SORDINO, ZTE and EPI acquisitions.

The slew rates of EPI, conventional ZTE, and SORDINO were compared based on the acquisition parameters used in rats, as described in Comparing Sensitivity of SORDINO and EPI, considering gradient increments in a single direction. The relationship between the change in k-space position, gradient strength and ramp time is expressed by: , where is the change in k-space position, representing movement along a spatial frequency range; (MHz/T) is the gyromagnetic ratio; (T/m) is the gradient amplitude; and is the gradient ramp time. Rearranging this equation to determine the gradient amplitude required to traverse a specified distance in k-space and normalizing the result to units per second yields the slew rate: . Under our standard rat SORDINO imaging parameters, with a TR of 1.82 ms, a temporal resolution of 2 s, and an isotropic spatial resolution of 0.6 mm3, the k-space extent is 1,666.67 m−1. As SORDINO encoding progresses from the center of k-space to the periphery, the signal is encoded over 833.34 m−1 per projection, with a ramp time of 1.81 ms. Although the total gradient slew rate and gradient amplitude are clamped across the acquisition of a volume, they are not identical for any given encoding direction. The mean incrementation between each projection is 0.00038 T/m, corresponding to a slew rate of 0.35 T/m/s. The conventional ZTE sequence on a Bruker system differs from SORDINO in that the encoding gradients are incremented between successive spokes. With a calibrated ramp time of 0.21 ms, the mean gradient incrementation of an equivalent ZTE sequence is 0.0033 T/m, yielding slew rates of 15.66 T/m/s — two orders of magnitude higher than SORDINO. In our rat fMRI experiments using EPI, a 2D acquisition with an in-plane spatial resolution of 0.6 mm also has a k-space extent of 1,666.67 m−1. The acquisition used a matrix size of 42 and employed a 50 μs gradient blip between successive frequency encoding steps, resulting in a phase encoding gradient amplitude of 0.018 T/m and a slew rate of 355.84 T/m/s. With a 250 kHz receiver bandwidth, sampling 44 points along the frequency encoding direction takes 0.176 ms. This corresponds to a gradient amplitude of 0.22 T/m and a slew rate of 1263.62 T/m/s — five and three orders of magnitude higher than SORDINO and ZTE, respectively.

Bloch equation modeling of SORDINO signal.

To understand the characteristics and potential sources of the SORDINO functional contrast, we carried out Bloch equation modeling. The Bloch equations describe how the SORDINO signal evolves over time in response to elements of the pulse sequence and relaxation114. We analyzed the Bloch equations in the rotating frame and did not consider the effect of B1 or gradients on precession. Further, our simulations focused solely on isochromats at isocenter, disregarding off-resonance precession. With these assumptions, the evolution of the net magnetization vector, , as a function of time is:

Where:

is a 3x3 matrix representing relaxation: ,

is a 3x1 vector representing recovery of the longitudinal component of the net magnetization vector towards equilibrium: .

RF-excitation was modeled as a rotation about the y-axis:

Where:

is the FA.

Since the acquisition delay of SORDINO – on the order of microseconds – is negligible compared to the T2* of the rodent brain, the SORDINO signal was taken as the transverse component of immediately following excitation. Consequently, precession was only considered over the repetition time (TR). In some cases, as RF-spoiling was implemented (Figure S1b), which is expected to significantly reduce formation of spurious echoes, perfect spoiling was assumed and the transverse component of was set to 0 at the end of every TR interval. Putting these components together, the after n repetitions can be expressed as: .

Modeling of SORDINO functional contrast.

Bloch equation modeling was carried out to estimate the source of the SORDINO functional contrast, considering changes in inflow-enhanced CBV and tissue oxygen levels (Figure 1e–f). Since RF-spoiling was implemented (Figure S1b)113, which is expected to significantly reduce formation of spurious echoes, perfect spoiling was assumed. The voxel signal was estimated by modeling the extravascular and intravascular compartments separately. Assuming the voxel-level T1 of 1900 ms, based on our own measurements (data not shown), a blood T1 of 2429 ms at 9.4 T115 and a vascular volume fraction of 5%, we estimated that the T1-value of extravascular tissue is 1878 ms. With head-only excitation, the inflow effect leads to apparent T1-shortening of the intravascular signal, resulting in a stronger signal than the stationary extravascular tissue at steady-state as flowing spins are subjected to RF-pulses only when within the sensitivity region of the transmitter. If the arterial transit time represents the duration flowing blood remains within the sensitivity region of the transmitter before reaching the brain, the blood signal will be in a dynamic state influenced by the arterial transit time, TR and flip angle of the sequence. Here, we assumed an arterial transit time of 280 ms116, a TR of 1 ms and flip angle of 3°. We estimated that the voxel signal at baseline comprises 95% extravascular tissue signal at a steady-state and 5% intravascular signal in a dynamic state. To model the effect of inflow-enhanced CBV, we assumed a local blood flow acceleration of 1.5 mm/s over an activation radius of 1 mm from a baseline flow of 10 mm/s117. This results in regionally accelerated blood being subjected to 13 fewer RF-pulses, along with a 20% increase in CBV. We estimated the effect of alterations in tO2 levels, guided by invasive measurements48 and molecular oxygen spin-lattice relaxivity studies49. Our model restricted the influence of tO2 to the extravascular compartment as physiological changes in blood oxygenation are not expected to influence T1 significantly56. Given that the change in T1-relaxation rate is linearly dependent on concentration and assuming a 30 μM activation-induced increase in pO2 and a r1 of 0.3 mM−1s−149, we estimated that the T1 of the extravascular tissue would be reduced by 37 ms. Together, these effects are expected result in an increase in the SORDINO signal. To model the effect of whole-body excitation, the hardware setup most commonly used in the clinical environment, we neglected the effect of inflow on blood signal in SORDINO contrast. Under this condition, we expect that an increase in CBV would result in a small decrease in the SORDINO signal due to the shorter T1 of blood compared to tissue. Modeling suggests that the combined effect of CBV and tO2 on the SORDINO signal would result in an increase in signal with magnitude approximately 50% of that observed under head-only excitation (Figure S3).

TR and flip angle selections in SORDINO.

To understand how the physical properties of the brain and imaging parameters influence the temporal evolution of the SORDINO signal, we modeled the SORDINO signal from the first excitation to the steady-state, assuming perfect spoiling (Figure S4a–c). This was done across five TRs (0.5, 0.7, 1, 2 and 3 ms), five flip angles (1°, 2°, 4°, 6° and 8°) and five baseline T1 values (500, 1000, 1500, 2000, and 3000 ms), while keeping non-varying parameters constant (TR = 2 ms, flip angle = 2° and T1 = 3000 ms). Our findings indicated that the steady-state SORDINO signal is sensitive to both TR and flip angle. Next, we sought to understand how SORDINO contrast varies with these imaging parameters (Figure S4e–f). Although a longer TR increases steady-state signal magnitude, a shorter TR allows for more spokes to be acquired in a given time. This reduces noise variance and is expected to minimize undersampling artifacts in SORDINO images. To account for this effect, we modeled contrast efficiency, defined as the raw contrast at steady-state divided by 53 at five TRs (0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9 and 1 ms) and five flip angles (1°, 2°, 3°, 4°, 5° and 6°). We assumed a 2% reduction in T1 from a physiological baseline of 1900 ms, with fixed parameters of TR = 0.7 ms and flip angle = 4°. Together, these models revealed that the sensitivity of SORDINO to T1 changes is dependent on both TR and flip angle. To identify an optimal parameter range for fMRI, we modeled the SORDINO efficiency under the assumption of perfect spoiling, across ten equally spaced TRs between 0.6 and 2.4 ms and six flip angles between 1 and 6° (Figure S4g). The model assumed a 2% decrease in T1 from a physiological baseline of 1900 ms, based on our own measurements (data not shown).

SORDINO efficiency with MEMRI.

To guide imaging parameter selection for proof-of-concept MEMRI experiments, we modeled SORDINO efficiency as described in TR and Flip Angle Selections in SORDINO at 9.4 T (Figure S6a). Based on literature findings, we assumed a 50% reduction in T189 from a baseline of 1900 ms. SORDINO efficiency was calculated across eight equally spaced TRs and flip angles ranging from 0.7 to 1.4 ms and 1 to 8°, respectively.

SORDINO-fMRI efficiency as a function of field strength.

To estimate the performance of SORDINO-fMRI at various magnetic field strengths, we calculated efficiency as described in TR and Flip Angle Selections in SORDINO (Figure S9). In all cases, we assumed a 30 μM48 activation-induced increase in tO2 and a r1 of 0.3 mM−1s−149 but different baseline T1 values. Guided by the literature, we assumed T1 values of 1035, 1272, 1600, 1900 and 2030 ms at field strengths of 1.5118, 3119, 4.7120, 9.4 and 17.6 T121, respectively.

Phantom Experiments and SORDINO Sequence Characteristics

To generate hypotheses about SORDINO’s ability to detect functional activations and its potential underlying contrast mechanisms, we conducted experiments to assess the temporal properties of the SORDINO signal and evaluate its suitability for functional imaging.

Assessment of gradient ramp time on SORDINO signal.

In preliminary experiments, we assessed whether the strategy of increasing gradient ramp time (i.e. reducing slew rate) impacts SORDINO image quality (Figure S1c). Using a homemade 1 cm ID surface transceiver, we acquired SORDINO images of deionized water and CuSO4 phantoms at a 3 s temporal resolution with the following parameters: TR = 1ms, flip angle =3°, receiver bandwidth = 99 kHz, and spokes = 3042. Data were acquired at 9 equally spaced ramp times between 0.1 and 0.9 ms, as well as an additional acquisition at 0.99 ms. Six repeated measurements of the phantoms were acquired at each ramp time. Image quality was assessed by computing tSNR and CNR metrics.

Assessment of receiver bandwidth on SORDINO tSNR.

After determining that extending the gradient ramping time does not adversely impact data quality, we assessed whether the low acquisition bandwidth of SORDINO increases tSNR as expected. We compared SORDINO acquisitions at various receiver bandwidths in deionized water phantoms (Figure S1d) and a perfusion-fixed mouse brain (Figure S1i). SORDINO images of deionized water were acquired using a homemade 1 cm ID surface transceiver at a 3 s temporal resolution with the following parameters: TR = 1ms, flip angle = 3°, pulse length = 4 μs, spokes = 3042, FOV = 40 mm3, matrix size = 603, and 80 repetitions at steady-state at two receiver bandwidths – 32 and 100 kHz. Six repeated measurements of the phantoms at each receiver bandwidth were acquired. The differences between each pair of measurements were tested for normality using a Shapiro-Wilk test, and the difference between the two measurements was assessed with a paired sample t-test. Next, we acquired SORDINO images of a perfusion-fixed mouse brain at receiver bandwidths of 32, 50, 75 and 100 kHz. The common imaging parameters were: TR = 2.5 ms, flip angle = 10°, spokes = 1966, FOV = 40 mm3, matrix size = 603 and 300 repetitions at steady-state. Six repeated measurements were taken at receiver bandwidths between 32 and 75 kHz, and five at 100 kHz.

Assessment of RF spoiling on FID signal using single-spoke acquisition.

RF-spoiling minimizes the unintended magnetization coherence formation, resulting in the generation of echoes, hereafter referred to as spurious echoes. We qualitatively assessed the effect of RF-spoiling on echo formation by implementing a single-spoke acquisition. This model comprises periodic repetitions of identical RF-pulses and gradients, leading to the formation of stimulated echoes at predictable intervals. We chose this model because it reliably produces strong and predictable stimulated echoes, allowing us to assess the maximum effect of RF-spoiling. The single-spoke acquisition was implemented by maintaining constant encoding gradient amplitudes. RF-spoiling was implemented by incrementing the phase of the RF-pulse by 117° upon each subsequent excitation. The acquisition parameters were as follows: TR = 0.517 ms, flip angle = 4°, 60 samples per projection, 120760 repetitions and receiver bandwidth = 100 kHz, x and y-gradient amplitudes = 1.92 × 10−4 T/m and z-gradient amplitude = 0.013 T/m. The FID amplitude was defined as the absolute value of the first sample of each projection acquired, following the dead time gap.

Analysis of water phantom data.