Abstract

The in vitro postantibiotic effects (PAEs), the postantibiotic sub-MIC effects (PA-SMEs), and the sub-MIC effects (SMEs) of DX-619 were determined for 16 gram-positive organisms. DX-619 pneumococcal, staphylococcal, and enterococcal PAE ranges were 1.7 to 5.0 h, 0.7 to 1.8 h, and 1.2 to 6.5 h, respectively. The PA-SME ranges (0.4× MIC) for pneumococci, staphylococci, and enterococci were 5.2 to >8.6 h, 2.1 to 8.3 h, and 4.9 to >10.0 h, respectively.

The postantibiotic effect (PAE) is a pharmacodynamic parameter that may be considered in choosing antibiotic dosing regimens. It is defined as the length of time that bacterial growth is suppressed following brief exposure to an antibiotic (1-4). Odenholt-Tornqvist and coworkers have suggested that, during intermittent dosage regimens, suprainhibitory levels of antibiotic are followed by subinhibitory levels that persist between doses and have hypothesized that persistent subinhibitory levels could extend the PAE. The effect of sub-MIC concentrations on growth during the PAE period has been defined as the postantibiotic sub-MIC effect (PA-SME), representing the time interval that includes the PAE plus the additional time during which growth is suppressed by sub-MIC concentrations. In contrast to the PA-SME, the SME measures the direct effect of subinhibitory levels on cultures which have not been previously exposed to antibiotics (7, 8).

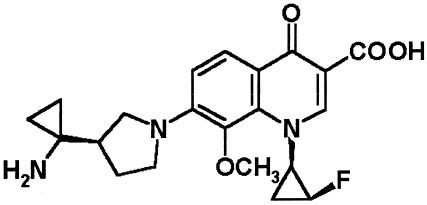

We examined the in vitro PAE, PA-SME, and SME of DX-619, a new experimental quinolone with improved activity against gram-positive organisms (Fig. 1) (H. Inagaki, R. N. Miyauchi, M. Itoh, K. Kimura, M. Chiba, M. Tanaka, H. Takahashi, M. Takemura, and I. Hayakawa, Abstr. 43rd Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F-1054, 2003; S. Watanabe, T. Ito, and K. Hiramatsu, Abstr. 43rd Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F-1055, 2003; D. B. Hoellman, L. M. Kelly, K. A. Smith, B. Bozdogan, M. R. Jacobs, and P. C. Appelbaum, Abstr. 43rd Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F-1056, 2003; K. Yanagihara, M. Tashiro, M. Okada, H. Ohno, Y. Miyazaki, Y. Hirakata, T. Tashiro, and S. Kohno, Abstr. 43rd Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F-1057, 2003; K. L. Credito, G. Lin, B. Bozdogan, M. R. Jacobs, and P. C. Appelbaum, Abstr. 43rd Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F-1058, 2003; D. Esel, L. Kelly, B. Bozdogan, and P. C. Appelbaum, Abstr. 43rd Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F-1059, 2003; M. Tanaka, K. Fujikawa, Y. Murakami, T. Akasaka, M. Chiba, T. Otani, and K. Sato, Abstr. 43rd Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F-1060, 2003; Y. Kurosaka, S. Nishida, C. Ishii, Y. Sawada, K. Namba, T. Otani, and K. Sato, Abstr. 43rd Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F-1061, 2003; Y. Tsuchiya, K. Goto, M. Igarashi, T. Jindo, and K. Furuhama, Abstr. 43rd Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F-1062, 2003). We studied two strains each of penicillin-susceptible, -intermediate, and -resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae (all quinolone susceptible, with ciprofloxacin MICs of ≤2.0 μg/ml, at a ciprofloxacin susceptibility breakpoint of 1.0 μg/ml); methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (all four staphylococcal strains ciprofloxacin susceptible with MICs of 0.5 μg/ml), Enterococcus faecalis; Enterococcus faecium (one strain vancomycin resistant). Two quinolone-nonsusceptible strains (ciprofloxacin MICs of ≥32 μg/ml) with defined alterations in the genes coding for DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV were also studied. These strains were one S. pneumoniae strain with mutations in gryA, and parC and one vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (Hershey) strain with alterations in gryA and grlB. Organisms were identified by standard methods (5).

FIG. 1.

Chemical structure of DX-619.

DX-619 MICs were determined by macrodilution procedures (6). The PAE was determined by the viable plate count method (3), using Mueller-Hinton broth supplemented with 5% lysed horse blood when testing pneumococci. The PAE was induced by exposure to 10× the MIC of DX-619 for 1 h.

For PAE testing, tubes containing 5 ml broth with antibiotic were inoculated with approximately 5 × 106 CFU/ml. Inocula were prepared by suspending growth from an overnight blood agar plate in broth. Growth controls with inoculum but no antibiotic were included with each experiment. Inoculated test tubes were placed in a shaking water bath at 35°C for an exposure period of 1 h. At the end of the exposure period, cultures were diluted 1:1,000 in prewarmed broth to remove the antibiotic by dilution. Antibiotic removal was confirmed by comparing growth curves of a control culture containing no antibiotic to another containing DX-619 at 0.001× the exposure concentration.

Viability counts were determined before exposure and immediately after dilution (0 h) and then every 2 h until turbidity of the tube reached a no. 1 McFarland standard. The PAE was defined as follows: PAE = T − C, where T = time required for viability counts of an antibiotic-exposed culture to increase by 1 log10 above counts immediately after dilution and C = corresponding time for growth control (3).

In cultures designated for PA-SME, the PAE was induced as described above, after exposure to 10× MIC (see above). Following 1:1,000 dilution, cultures were divided into four tubes. To three tubes, DX-619 was added to produce final subinhibitory concentrations of 0.2, 0.3, and 0.4× MIC. The fourth tube did not receive antibiotic. Viability counts were determined before exposure, immediately after dilution, and then every 2 h until their culture turbidity reached that of a no. 1 McFarland standard. Cultures designated for SME were treated the same as for PA-SME testing, except the PAE was not induced.

PA-SME was defined as follows: PA-SME = Tpa − C, where Tpa = time for cultures previously exposed to antibiotic and then reexposed to different sub-MICs to increase by 1 log10 above counts immediately after dilution and C = corresponding time for the unexposed control (7, 8). The SME was defined as follows: SME = Ts − C, where Ts = time for the cultures exposed only to sub-MICs to increase 1 log10 above counts immediately after dilution and C = corresponding time for unexposed the control. The PA-SME and SME (7, 8) were measured in two separate experiments. For each experiment, viability counts (log10 CFU/ml) were plotted against time and the results are expressed as the mean of two separate assays using two separate inocula.

The DX-619 MICs were as follows: pneumococci, 0.004 to 0.03 μg/ml; S. aureus, 0.004 to 0.25 μg/ml; E. faecalis, 0.03 to 0.25 μg/ml; and E. faecium, 0.125 to 0.25 μg/ml (Table 1). MICs of the two quinolone-resistant S. pneumoniae and S. aureus were higher when compared to susceptible strains of the same genus (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

PAE of DX-619 against 16 strains

| Straina | MIC (μg/ml) | Effect (h) atb:

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAE | 0.2× MIC

|

0.3× MIC

|

0.4× MIC

|

|||||

| SMEc | PA-SMEd | SME | PA-SME | SME | PA-SME | |||

| S. pneumoniae | ||||||||

| Pens | 0.008 | 4.6, 5.0 | 2.1, 2.5 | 7.0, 8.6 | 3.3, 3.6 | >8.6, >9.0 | 5.5, 6.2 | >8.6, >9.0 |

| 0.008 | 3.3, 3.5 | 0.8, 1.3 | 3.3, 5.1 | 1.8, 2.2 | 5.8, 6.0 | 4.3, 4.7 | 7.8, >9.3 | |

| Peni | 0.008 | 4.3, 4.4 | 1.8, 3.1 | 5.3, 6.4 | 3.6, 4.0 | 6.5, 7.7 | 5.6, 6.4 | 6.7, 8.2 |

| 0.008 | 3.5, 4.3 | 1.4, 2.1 | 5.5, 6.0 | 2.0, 2.8 | 7.4, 7.8 | 4.7, 6.0 | 8.9, 9.0 | |

| Penr | 0.008 | 1.7, 1.8 | 1.2, 1.8 | 2.9, 3.1 | 1.2, 2.7 | 3.2, 3.8 | 1.2, 2.7 | 5.2, 5.3 |

| 0.004 | 2.5, 4.0 | 0.3, 0.6 | 4.6, 5.5 | 2.2, 2.5 | 5.3, 6.7 | 4.2, 4.9 | 6.8, 7.3 | |

| Quinr | 0.03 | 3.0, 3.4 | 0.2, 1.3 | 4.0, 4.7 | 0.7, 1.5 | 4.7, 6.5 | 1.3, 2.2 | 5.2, 7.5 |

| S. aureus | ||||||||

| Methicillin susceptible | 0.004 | 0.7, 0.8 | 0.3, 0.4 | 2.1, 2.3 | 1.5, 1.7 | 3.6, 3.8 | 2.1, 3.8 | 5.0, 8.3 |

| 0.004 | 0.9, 1.3 | 0.2, 0.6 | 1.5, 1.7 | 0.7, 0.8 | 1.8, 2.4 | 1.2, 2.7 | 2.1, 3.5 | |

| Methicillin resistant | 0.004 | 1.2, 1.2 | 0.2, 0.5 | 1.5, 2.2 | 0.5, 0.5 | 2.3, 3.0 | 0.5, 1.3 | 3.8, 4.0 |

| 0.004 | 1.4, 1.6 | 0.3, 0.4 | 1.7, 2.8 | 0.5, 1.1 | 3.6, 3.9 | 1.1, 2.1 | 4.9, 5.5 | |

| Quinolone resistant (VRSA Hershey)e | 0.25 | 1.6, 1.8 | 0, 0.2 | 1.8, 2.0 | 0, 0.4 | 3.1, 3.2 | 0.7, 0.8 | 3.2, 3.8 |

| E. faecalis | 0.25 | 1.2, 1.7 | 0.7, 0.7 | 2.7, 3.3 | 1.6, 1.8 | 3.4, 4.2 | 3.4, 4.2 | 5.5, 7.5 |

| 0.03 | 2.5, 2.8 | 0.8, 1.1 | 3.6, 3.6 | 1.5, 1.5 | 4.0, 4.0 | 2.0, 2.4 | 4.9, 5.0 | |

| E. faecium | ||||||||

| Vancomycin susceptible | 0.125 | 6.3, 6.5 | 0, 0 | 6.8, 10.0 | 2.0, 2.2 | 8.5, >10.0 | 3.5, 5.8 | >10.0, >10.2 |

| Vancomycin resistant | 0.25 | 4.8, 6.2 | 0.7, 1.3 | 4.2, 8.5 | 1.5, 1.6 | 8.7, >10.5 | 4.2, 5.3 | >10.5, 10.7 |

Pens, Peni, Penr, and Quinr, penicillin susceptible, penicillin intermediate, penicillin resistant, and quinolone resistant, respectively.

Values are those obtained in two separate experiments. Strains were exposed to 10× MIC of DX-619 (see text) for 1 h at 35°C. The drug was removed by 1:1,000 dilution.

Strains not previously exposed to DX 619.

Strains previously exposed to DX-619.

VRSA, vancomycin-resistant S. aureus.

The PA-SMEs were longer than the PAEs for all strains tested and increased with subinhibitory concentration of DX-619. For the seven pneumococci, the mean PAE was 3.5 h, ranging between 1.7 and 5.0 h. At 0.4× MIC, penicillin-susceptible, -intermediate, and -resistant strains and quinolone-resistant strains had mean PA-SMEs of >7.8 h, 8.2 h, 6.2 h, and 6.4, respectively (Table 1).

Staphylococcal PAEs were 0.7 to 1.8 h, with a mean of 1.2 h. Staphylococcal PAEs did not differ greatly in methicillin-susceptible (0.7 to 1.3 h) or -resistant (1.2 to 1.6 h) and quinolone-resistant (1.6 to 1.8 h) S. aureus strains. The PA-SME at 0.4× MIC (mean for all five strains, 4.4 h) was longer than PAEs plus SMEs in one of the two methicillin-susceptible strains, both methicillin-resistant strains, and the quinolone-resistant strain. For the two methicillin-resistant strains, an increased PA-SME was found in both strains (3.8 to 5.5 h) compared to the SME (0.5 to 2.1 h) at 0.4× MIC (Table 1).

For the two E. faecalis strains, the mean PAE was 2.0 h. At 0.4× MIC, the PA-SME values were 4.9 h to 7.5 h. By comparison, for the two E. faecium strains the mean PAE and PA-SME (0.4× MIC) were 6.0 and >10.0 h, respectively (Table 1).

DX-619, like other quinolones, exhibits rapid concentration-dependent bactericidal activity and long PAEs (9). In this study, DX-619 PAEs ranged from 0.7 to 6.5 h for all strains. The PAEs for S. aureus strains were generally shorter than those of the other strains tested. DX-619 produced PAE and PA-SMEs in two quinolone-resistant strains (S. pneumoniae and S. aureus) that did not differ greatly from those for sensitive strains. Long PA-SMEs were found for all strains and ranged from 1.7 to 10 h, 1.8 to >8.6, and 2.1 to >8.6 h at subinhibitory concentrations of 0.2, 0.3, and 0.4× MIC, respectively. These PA-SMEs may be more clinically relevant compared to the PAEs during intermittent dosage regimens, since suprainhibitory concentrations will be followed by exposure to subinhibitory concentrations in vivo. Longer intervals between doses may be possible when an antibiotic has a long half-life as well as a prolonged PAE and PA-SME, because regrowth continues to be prevented when serum and tissue levels fall below MICs (1, 2). The PAE and PA-SME would only be important for organisms with high MICs where serum levels (at least of free drug) would fall below the MIC. This would not occur with pneumococci and staphylococci with low MICs, and could be a problem for strains such as one of our methicillin-susceptible S. aureus strains with relatively short values. With these caveats, our results support once-daily dosing of DX-619, with possible twice-a-day dosing against methicillin-resistant S. aureus. These hypotheses must await further pharmacokinetic studies.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from Daiichi Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cars, O., and I. Odenholt-Tornqvist. 1993. The postantibiotic subMIC effect in vitro and in vivo. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 31:159-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Craig, W. 1993. Pharmacodynamics of antimicrobial agents as a basis for determining dosage regimens. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 12(Suppl. 1):6-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Craig, W. A., and S. Gudmundsson. 1996. Postantibiotic effect, p. 296-329. In V. Lorian (ed.), Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. Williams and Wilkins Co., Baltimore, Md.

- 4.MacKenzie, F. M., and I. M. Gould. 1993. The post-antibiotic effect. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 32:519-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray, P. R., E. J. Baron, M. A. Pfaller, F. C. Tenover, and R. H. Yolken (ed.). 1995. Manual of clinical microbiology, 7th ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 6.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2003. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 6th ed. Approved standard. NCCLS publication no. M7-A6. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 7.Odenholt-Tornqvist, I. 1993. Studies on the postantibiotic effect and the postantibiotic sub-MIC effect of meropenem. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 31:881-892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Odenholt-Tornqvist, I., E. Löwdin, and O. Cars. 1992. Postantibiotic sub-MIC effects of vancomycin, roxithromycin, sparfloxacin, and amikacin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36:1852-1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pankuch, G. A., M. R. Jacobs, and P. C. Appelbaum. 2003. Postantibiotic effects of garenoxacin (BMS-284756) against 12 gram-positive or -negative organisms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1140-1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]