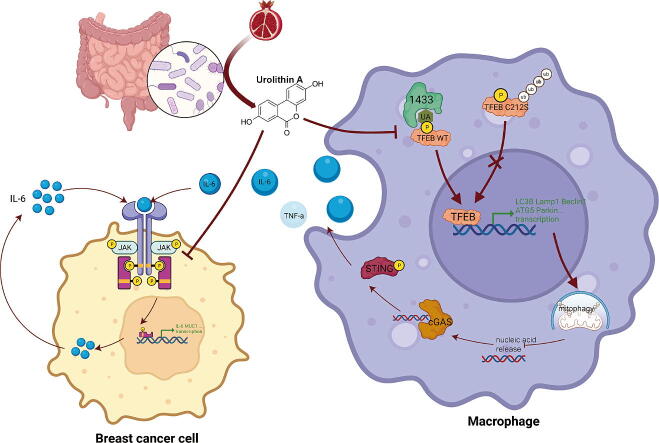

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Urolithin A, Breast cancer, TFEB, Mitophagy, Tumor-associated macrophages

Highlights

-

•

Urolithin A inhibits breast cancer cell and tumor macrophage IL-6 secretion through different mechanisms.

-

•

Urolithin A suppresses tumor macrophages harmful Inflammation through activation of mitophagy.

-

•

Urolithin A-mediated mitophagy and antitumor activity depend on TFEB nuclear translocation.

-

•

C212S mutation abolishes the effect of urolithin A blocking 1433 recognition of phosphorylated TFEB.

Abstract

Introduction

Urolithin A (UA) is a naturally occurring compound that is converted from ellagitannin-like precursors in pomegranates and nuts by intestinal flora. Previous studies have found that UA exerts tumor-suppressive effects through antitumor cell proliferation and promotion of memory T-cell expansion, but its role in tumor-associated macrophages remains unknown.

Objectives

Our study aims to reveal how UA affects tumor macrophages and tumor cells to inhibit breast cancer progression.

Methods

Observe the effect of UA treatment on breast cancer progression though in vivo and in vitro experiments. Western blot and PCR assays were performed to discover that UA affects tumor macrophage autophagy and inflammation. Co-ip and Molecular docking were used to explore specific molecular mechanisms.

Results

We observed that UA treatment could simultaneously inhibit harmful inflammatory factors, especially for InterleuKin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), in both breast cancer cells and tumor-associated macrophages, thereby improving the tumor microenvironment and delaying tumor progression. Mechanistically, UA induced the key regulator of autophagy, transcription factor EB (TFEB), into the nucleus in a partially mTOR-dependent manner and inhibited the ubiquitination degradation of TFEB, which facilitated the clearance of damaged mitochondria via the mitophagy-lysosomal pathway in macrophages under tumor supernatant stress, and reduced the deleterious inflammatory factors induced by the release of nucleic acid from damaged mitochondria. Molecular docking and experimental studies suggest that UA block the recognition of TFEB by 1433 and induce TFEB nuclear localization. Notably, UA treatment demonstrated inhibitory effects on tumor progression in multiple breast cancer models.

Conclusion

Our study elucidated the anti-breast cancer effect of UA from the perspective of tumor-associated macrophages. Specifically, TFEB is a crucial downstream target in macrophages.

Background

The leading cause of cancer-related deaths among female patients is breast cancer, which has surpassed lung cancer in terms of prevalence worldwide [1]. First-line therapeutic drugs such as chemotherapy and endocrine therapy are associated with high side effects and are not tolerated by some patients. In recent years many natural compounds have been reported to exert tumor-suppressive effects, such as baicalein for the treatment of lung cancer [2], and these drugs have the advantages of easy extraction and few side effects, but they have not been widely used due to poor targeting and unknown anti-cancer mechanisms.

UA is an intestinal metabolite of ellagitannin-like precursors from pomegranates and nuts [3]. It was earlier reported to improve skeletal muscle function by promoting mitochondrial autophagy [3] and was demonstrated in clinical trials [4]. UA has been previously reported to have antitumor effects, inhibiting tumor cell proliferation through multiple signaling pathways [5], [6] and improving drug resistance [7]. UA diet increases immunotherapeutic efficacy by promoting memory T cell expansion [8]. However, its effect on tumor macrophages remains unreported. Macrophages are important in tumor development [9]. In advanced breast cancer, macrophages exhibit M2 polarization, secrete arginase-1 and other pro-oncogenic inflammatory factors, and inhibit the antitumor effects of CD8 + T cells [10], [11]. Macrophage-derived IL-6 activates the tumor cell Jak/Stat signaling pathway and activates miR-506-3p −regulated CCL2 expression to increase macrophage recruitment [12]. Positive feedback interaction between tumor cells and macrophages promotes tumor progression [13]. Immune checkpoint blockade therapies targeting macrophages are also being continually investigated to help restore the ability of macrophages to clear tumors.

TFEB protein is a transcription factor that regulates autophagy and lysosomal functions [14]. TFEB has been reported as an oncogene in tumor cells to help repair DNA damage and promote tumor cell proliferation [15], [16]. Interestingly, there are also articles reporting that TFEB exerts an anticancer effect in tumor macrophages [17]. This seemingly contradictory finding prompted us to explore the correlation between TFEB expression levels and breast cancer prognosis. We found that both TFEB protein and RNA levels showed low tissue expression in breast cancer tumors and were associated with a good prognosis. Due to the diversity of cancers, we speculated that there were different functions of TFEB in tumor cells and tumor macrophages affecting breast cancer prognosis. Past studies have also suggested that low TFEB expression is associated with a pro-proliferative inflammatory tumor microenvironment [17].

We found that in tumor supernatant-intervened macrophages, UA inhibits the release of IL-6 and TNF-α, by activating TFEB-mediated mitophagy and helping to clear damaged mitochondria. Meanwhile, UA treatment of tumor cells exhibited inhibition of STAT3 phosphorylation and antiproliferative effects. UA inhibits breast cancer development through synergistic effects on tumor cells and macrophages. Mechanistically, UA induced TFEB entry into the nucleus in an mTOR-partially dependent manner by blocking 1433 recognition of the TFEB S211 phosphorylation site. UA treatment rescued tumor supernatant-mediated downregulation of total TFEB protein by inhibiting increased ubiquitination due to TFEB inactivation. The TFEB C212S mutation altered the state of 1433 recognition of TFEB, depriving UA of its role in facilitating TFEB nuclear entry.

Materials and methods

Tissue samples

Tumor tissues and adjacent normal tissues from BC patients were collected by the Department of Breast and Thyroid Surgery at Shanghai Tenth People's Hospital of Tongji University. No patient received any local or systemic treatments before surgery, and all tissue samples were promptly frozen in liquid nitrogen. The institutional ethics committees of Shanghai Tenth People's Hospital acknowledged the informed consent of each participant. The procedures followed in this study were in accordance with the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration.

Cell culture

The breast cancer cell lines MDA-MB-231, BT-549, MCF-7, 4 T1, and macrophages cell lines THP-1, and iBMDMs were purchased from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). MDA-MB-231, MCF-7, 4 T1, iBMDMs, and HEK293T cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (Gibco, USA) with 10 % Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) (Gibco, USA), penicillin and streptomycin (Enpromise, China). THP-1 and BT-549 cells were grown in the RPMI-1640 Medium (Gibco, USA). Age-matched female wild-type (WT) C57Bl/6 bone marrow cells were cultured for 7 days in complete media with Colony Stimulating Factor (M−CSF) after being plated in 6- or 12-well plates for 4 h to remove non-adherent cells. All cell lines mentioned above were incubated at 37 °C with 5 % CO2.

Cell transfection

Transfection reagent Lipo8000 (C0533, Beyotime, China) was used for transfection h-sh-TFEB, h-Flag-TFEBWT, h-Flag-TFEBC212S (from Generay company, Shanghai, China) plasmids into HEK293T, BT-549, and MDA-MB-231 cells. Lentiviral infestation reagents carrying h-shTFEB, h-shNC, m-shTFEB, m-shNC, h-Flag-TFEBWT, h-Flag-TFEBC212S plasmids (m = mice and h = human) were purchased from Genechem company (Shanghai, China), and follow the reagent vendor's instructions. Sequence information for the plasmids used is available in the TableS1.

Cell coculture

Tumor cells and macrophages were seeded in the upper and lower chambers of 0.4um pore size transwell chambers for 6-well plates, respectively. Firstly, 3 ml of resuspended cells in the lower chamber were added to the six-well plate, then place the transwell chamber and let stand for a while until the upper chamber was filled with liquid. Add the cells in the upper chamber, incubate for 24 h and let the cells stick to the wall, and then carry out the UA treatment. Last. extract the RNA or protein of the cells in the lower chamber.

Tumor conditioned media acquisition

Based on the description of previous studies [18], to capture tumor-conditioned media (TCM), 4 T1 or BT-549 cells were cultured in a 10 cm dish, and tumor cells were placed and grown to 90 % confluence. After removing the medium, the cells were rinsed twice in serum-free DMEM. Subsequently, the medium was changed to fresh, serum-free DMEM. One day later, the collected supernatant was centrifuged to remove the cells to obtain TCM.

Cell drug intervention

THP-1 cells were induced to adhere to the wall with 100 ng/ml PMA (HY-18739, MCE, China). Urolithin A (HY-100599, MCE, China) was set up five working concentrations, which were 5, 10, 25, and 50µM, control group added an equal amount of DMSO. Different samples were harvested with different times of UA treatment, as explained in the results section. Cells were exposed to 150 ng/ml LPS (HY-D1056, MCE, China) for 3 h, subsequently, proceed with the separation of cytoplasm and nucleus proteins. To inhibit phosphorylation of mTOR, cells were treated with 10 uM MHY1485 (HY-B0795, MCE, China) for 4 h. For MG-132 (HY-13259, MCE, China) treatment, CM preconditioning was performed first for 24 h, then cells were treated with 10 μM MG-132 for 4 h. For CHX (HY-12320, MCE, China) treatment, CM preconditioning was performed for 24 h, UA and CHX (20 μg/ml) were then used together to treat the cells, and cellular proteins were captured after 0, 4, 8 and 12 h respectively. To inhibit the fusion of autophagosomes and lysosomes, cells were treated with 100 nM Bafilomycin A (HY-100558, MCE, China) for 24 h.

MTT, Colony formation, wound healing, and transwell migration assay

After UA treatment, cells were dissociated with trypsin, and the cell density was measured to obtain the required number of cells for subsequent MTT, colony formation, and transwell migration assay experiments. MTT 2000 cells were placed into each well of 96-well plates. The cells were identified according to the manufacturer's instructions using an MTT test kit (Sigma). A microplate reader measured the 490 nm optical density after 24, 48, 72, and 96 h. Colony formation 1000 cells per well in six-well plates were transplanted. To disclose the colonies, 75 % ethanol was used to preserve the cells, 0.1 % crystalline purple was used to color the cells, and two cold phosphate buffer solution (PBS) rinses were completed. Then colonies were counted and photographed. Wound healing assay After the cells had attained about 90 % confluence, a scratch was made in each well using a 200 ul pipette tip. The tip was maintained parallel to the plate. The cells were washed twice with 1x PBS before being cultured in DMEM medium without FBS to remove the influence of cell growth on the results. The same area of wound healing was seen under a light microscope. Transwell migration Cell migration ability was evaluated using transwell chambers in 24-well plates (Corning, USA). 200 µl of media without serum was used to transfer 3x104 cells into the top chamber, and a medium containing 10 % FBS was added to the bottom chamber. Cells in the top chamber were meticulously taken out with a cotton swab 24 h later. After that, the cells on the other side of the filter were stained with 0.1 % crystal violet for 10 min and fixed with 70 % ethanol for 30 min. A light microscope (Leica Microsystems, Mannheim, Germany) was used to capture images, and migrating cells were counted in five random areas.

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR

The total RNA from paired breast cancer tissues or cells was extracted using the TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA). The cDNA was produced using the HiScript III RT SuperMix kit (Vazyme Biotech, Nanjing, China). qRT-PCR was carried out using the SYBR Green Master Mix (Abclonal, Shanghai, China) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Primers were synthesized from Generay (Shanghai, China). Beta-Actin and GAPDH were used as internal references in genes. The relative expression of RNA was assessed using the threshold cycle (CT) values. Sequence information for the primers is available in Table S2.

Protein separation

To extract the total proteins, cells were allowed to lyse on ice following the addition of the RIPA (witf the protease inhibitor Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and the phosphatase inhibitor). After 30 min, the proteins were scraped off and the supernatant was taken after high-speed centrifugation. The supernatant and loading buffer mix was heated at 100 °C for 10 min and stored at −20 °C. To extract total proteins from patient-sourced samples, took soybean size tissue, cut it with scissors, added lysis buffer at 4 °C and homogenized well, the rest of the steps were the same as the cell protein extraction. Protein separation of cytoplasm and cytosol according to reagent vendor's instructions (P0027, Beyotime, China). Specifically, cells were lysed in specific buffer, then the lysate was centrifugated for 5 min at 14,000 g/min. The supernatant represented cytoplasmic fraction while pellet (represented nuclear fraction) was lysed in RIPA buffer. Complete the mitochondrial separation experiment according to the manufacturer's instructions (C3601, Beyotime, China). After that, RIPA was used to extract the mitochondria protein.

Immunoprecipitation

After 36 h UA and CM treatments, the cells were lysed using Co-IP buffer including protease and phosphatase inhibitors. After 10-minute centrifugation at 12000g, the supernatants were collected and incubated with the specific primary antibody more than 16 h at 4 °C. The next day, incubate with protein A/ G agarose beads (abs995, absin, China) for 6 h. Then, the beads were washed three times using the IP buffer. Elution was performed by boiling the immunoprecipitates in 1xSDS sample buffer. Antibodies used in this experiment were listed: anti-TFEB (13372–1-AP, proteintech, China), and anti-Flag (AE005, abclonal, China).

Western blot

Proteins were separated using SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Separated proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose filter membranes. After 1 h blocking with 5 % BSA at room temperature, membranes were incubated with the prespecified antibodies at the indicated dilutions at 4 °C overnight. The next day, membranes were incubated with secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature and washed with TBST for 10 min three times. Last, membranes were scanned using the Odyssey Infrared scanning apparatus. Beta-actin and GAPDH are used for total protein normalization, while Histone H3 and LaminA/C are used for nuclear protein normalization. HSP60 is used for mitochondrial protein normalization. All the stock numbers of the antibodies used are available in Table S3.

ELISA

Collect mice plasmas or cell supernatants from UA and control groups after 24 h treatment. Experiment according to the reagent vendor's instructions (RK00004, Abclonal, China). Absorbance was measured at 450 nm wavelengths and then converted to concentration.

Immunofluorescence staining

THP-1 was grown on glass coverslips in 24-well plates. The cells were fixed for 10 min, then permeabilized with 0.1 % Triton X-100, blocked with 5 % BSA for 30 min, and subsequently stained with specific antibodies. Cells transfected with the corresponding plasmids were stained with the relevant anti-Flag antibody. Incubated with secondary antibodies coupled with DyLight 488 (AS037, Abclonal, China) and DyLight 594 (AS039, Abclonal, China) for 1 h. Stain nuclei with DAPI. Use a fluorescence microscope to take pictures.

JC-1 assays

THP-1 cells were seeded in six-well plates (added PMA), with conditioned medium and UA treatment 24 h in advance, followed by JC-1 experiments according to the reagent vendor's instructions (G1515-100 T, Servicebio, China) and photographed using a fluorescence microscope.

Patient-derived organoid

BC patients' tumor tissues were gathered by the Department of Breast and Thyroid Surgery. Fresh tumor tissue specimens were placed on ice and transported to the laboratory. Wash, digest, and remove erythrocytes according to the reagent vendor's instructions (abs9446, Absin, China). Cell suspension was mixed with matrix gel and planted in 24-well plates. Added specialized culture medium and cultivated at 37 °C. UA treatment (50 µM) was administered every 48 h. The sizes of cell clusters in Urolithin A treatment and control groups were observed under a light microscope (Leica Microsystems, Mannheim, Germany).

Animal experiments

Four weeks female BALB/c mice (shanghai SLAC, China) were randomized into four groups at random (n = 4 in each group) for the graft tumor experiment. Lentiviruses carrying m-shTFEB, and m-shNC were screened using puromycin after infiltration of iBMDMs to obtain stably expressing macrophages. 1.5 million 4 T1 and 0.5 million iBMDMs were mixed, resuspended in 150 µl of serum-free DMEM medium, and injected into the fat pads of mice after hair removal. Tumor tissue was observed after one week of growth (about 3 mm). Then, mice were kept on a UA-containing diet (2 g/kg) [8]or a control diet for two weeks. To obtain mice plasma, blood was collected from the eye socket. Then, collected the supernatant after centrifugation (3000 rpm, 15 min). Last, the mice were executed and subcutaneous tumor tissue, liver, and kidney tissue were collected.

IHC and HE staining

IHC After fixation, dehydration, embedment, and slicing, tissues were stained with anti-TFEB (13372–1-AP, proteintech, China), anti-ki67 (Servicebio offered) anti-IL-6 (Servicebio offered). HE Staining is carried out according to the reagent manufacturer's instructions (C0105S, Beyotime, China).

Molecular docking

The RCSB PDB database (https://www.rcsb.org/) was used to get the crystal structures of the ligand binding domain from human TFEB (6a5q). UA ‘s chemical composition was obtained from the pubchem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Based on these discovered chemical structures, protein–ligand docking investigations involving TFEB and UA were conducted using AutoDock (v4.2) tools. Specifically, all files were converted into the PDBQT format, removing all water molecules and adding polar hydrogen atoms. The grid box was positioned in the middle to permit free molecular mobility and include the domains of the protein.

Statistical analysis

Data from three times independent experiments were represented as mean ± standard error mean (SEM), and statistical analysis was carried out using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA) and Microsoft Excel. Statistical significance was assessed using a two-tailed Student's t-test when comparing two groups, and one-way ANOVA when comparing more than two groups. The relationships between TFEB expression and patents’ clinicopathologic characteristics were analyzed via Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. The threshold for statistical significance in each analysis was set at p < 0.05.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Shanghai Tenth People’s Hospital (No.2020-KN174-01). All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Shanghai Tenth People’s Hospital (No. SHDSYY-2021–0600).

Results

UA disrupts the IL-6-STAT3-IL-6 loop to inhibit breast cancer cell proliferation and migration

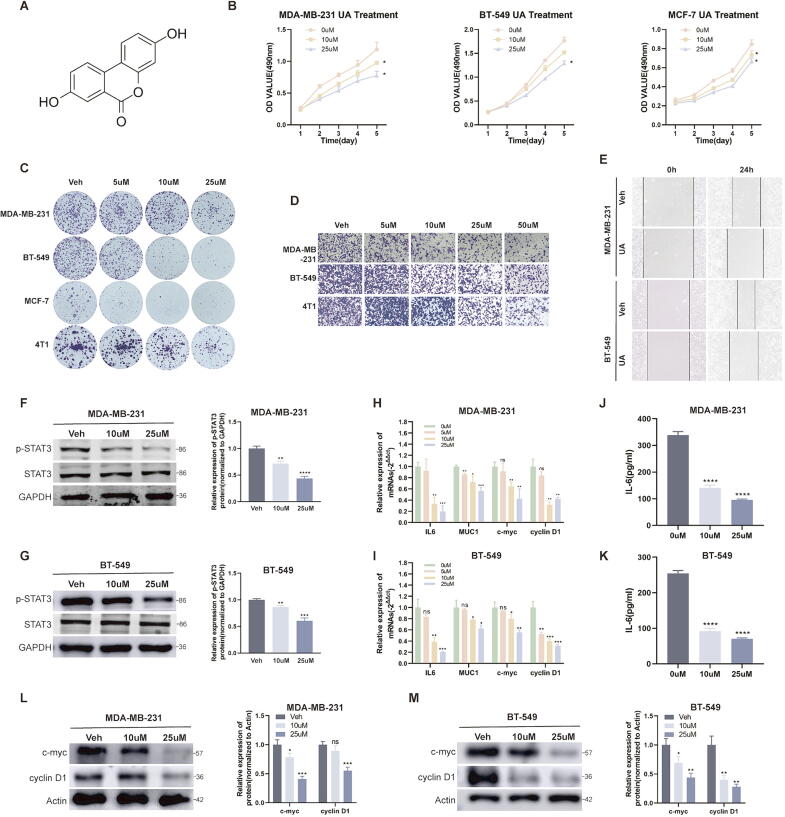

UA is one of the urolithin family and has a relatively simple chemical formula (Fig. 1A). For breast cancer, UA has been reported to regulate ERα, as well as being a possible substrate for breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2/BCRP) [19], [20]. In our study, after treating breast cancer cell lines MDA-MB-231, BT-549, MCF-7, and 4 T1 with different concentrations of UA for one day, MTT and colony formation assay suggested that UA weakened the proliferative activity of breast cancer cells (Fig. 1B and C). Wound healing and transwell migration assay suggested that UA weakened the migration capability (Fig. 1D and E). STAT3 is an important transcription factor that regulates cell proliferation and migration, and we found that UA treatment inhibited the phosphorylation activation of STAT3 and the transcription of its downstream genes including muc1, c-myc and cyclinD1 in MDA-MB-231 and BT-549 cells (Fig. 1F-I). It was also verified at the protein level (Fig. 1L–M). Interestingly, IL-6 acts both as a ligand for the signaling pathway of STAT3 and is also transcriptionally regulated by STAT3 [21], and UA intervention inhibited the IL-6/STAT3/ IL-6 positive feedback loop in tumor cells, reducing IL-6 transcription and secretion (Fig. 1J–K). Since the role of UA on tumor cells has been reported in numerous studies, we focused our study on tumor macrophages.

Fig. 1.

UA inhibits breast cancer cell proliferation and migration. A Chemical structural formula of UA. B MTT assays were performed to compare the proliferative capacity of breast cancer cells after UA treatment at different concentrations. C Colony formation assays were performed to detect the proliferative capacity of breast cancer cells after UA treatment at different concentrations. D, E Transwell migration and wound healing assays were conducted to detect the migration capacity of breast cancer cells after UA treatment. F, G Total STAT3 and phosphorylated STAT3 protein levels in breast cancer cells were detected by western blot after UA treatment. H, I The expression level of relevant mRNA after UA treatment were detected by real-time quantitative PCR. J, K IL-6 abundance in tumor supernatants after UA treatment was detected by ELISA assay. L, M c-myc and cyclin D1 protein levels in breast cancer cells were detected by western blot after UA treatment. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; Student's t-test was performed using Graphpad Prism. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

UA attenuates macrophage mitochondrial damage under tumor supernatant stress by promoting mitophagy

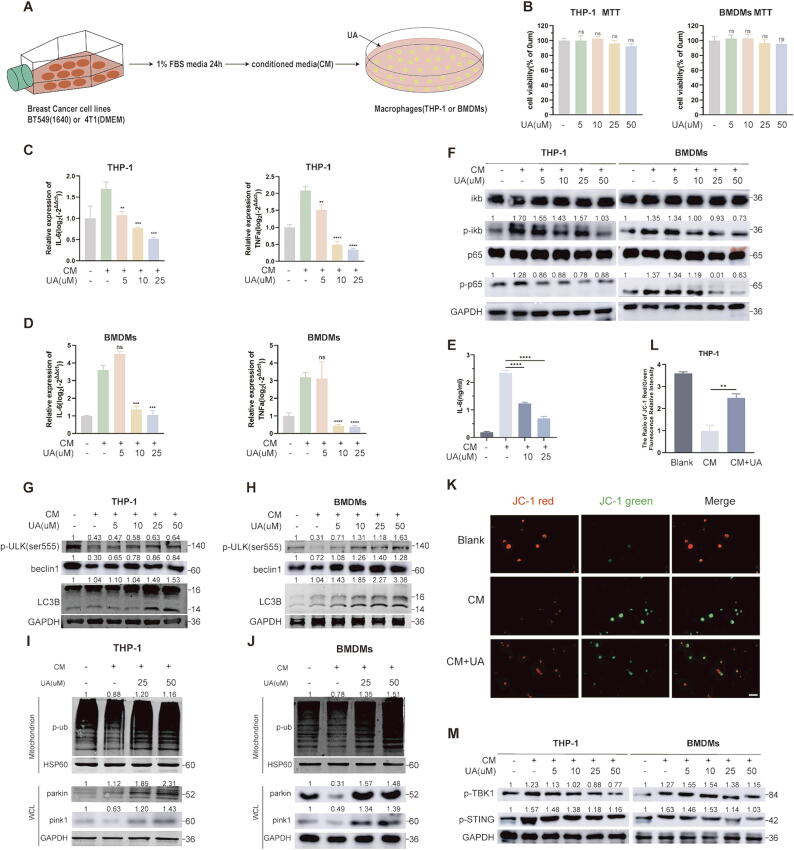

We collected tumor-conditioned media (abbreviation CM) to construct a tumor-associated macrophage model [18]. Treatment of THP-1 (added PMA) and BMDMs cells with BT-549 and 4 T1 cell supernatants, respectively, followed by UA treatment (Fig. 2A). MTT assays suggested that UA treatment did not have much effect on macrophage activity (Fig. 2B). Macrophages under tumor supernatant stress exhibit elevated inflammatory factors such as IL-6, TNF-α [17], and these deleterious inflammatory factors accumulate in the tumor microenvironment and promote tumor progression [22]. We found that UA treatment reversed CM stimulation-induced elevated mRNA expression of IL-6 and TNF-α (Fig. 2C and D) and decreased extracellular secretion of IL-6 (Fig. 2E). Since the transcription of IL-6 and TNF-α is mainly regulated by the NF-κB signaling pathway, we tried to observe the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway. UA treatment inhibited the phosphorylation activation of p65 and iκb in the NF-κB signaling pathway (Fig. 2F). UA has been reported to promote mitophagy in skeletal muscle [3], PINK/PARKIN-induced mitophagy attenuates stimulator of interferon genes (STING) −mediated inflammation by inhibiting cytoplasmic leakage of mitochondrial nucleic acids [23]. STING acts as an upstream regulator of NF-κB to promote inflammatory activation [24]. Therefore, we speculate that UA treatment clear damaged mitochondria under CM stress to inhibit activation of harmful inflammation in tumor macrophages.

Fig. 2.

UA activates mitophagy in tumor macrophages to inhibit IL-6 secretion. A The process of acquisition of tumor-conditioned media and intervention in macrophages. B MTT assays were performed to compare the cell viability after UA treatment. C, D IL-6 and TNF-α mRNA levels in THP-1 and BMDMs after UA and CM treatment were detected by real-time quantitative PCR. E IL-6 abundance in THP-1 cell supernatants after UA and CM treatment was detected by ELISA assay. F NF-κb pathway-associated protein levels in THP-1 and BMDMs were detected by western blot after UA and CM treatment. G, H Macroautophagy-associated protein levels in THP-1 and BMDMs were detected by western blot after UA and CM treatment. I, J Mitophagy-associated protein levels in THP-1 and BMDMs were detected by western blot after UA and CM treatment. (WCL = whole cell lysate) K, L JC-1 assays were performed to detect mitochondrial membrane potential changes after UA and CM treatment. M Phosphorylated STING and TBK protein levels in THP-1 and BMDMs were detected by western blot. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; Student's t-test was performed using Graphpad Prism. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

To test the conjecture, we first examined indicators of macroautophagy, p-ulk, beclin1, and LC3B, UA treatment restored macrophage macroautophagy inhibition under CM stress (Fig. 2G and H). We went on to examine indicators of mitophagy, including PINK1, parkin as well as phosphorylated ubiquitin in mitochondrial fractions, and observed the same trends (Fig. 2I and J). JC-1 assay suggested UA treatment reverses the decline in mitochondrial membrane potential under CM stress, which attributed to the timely removal of damaged mitochondria (Fig. 2K and L). Cytoplasmic leakage of nucleic acids from damaged mitochondria is an important activator of macrophage inflammation, activating the sting signaling pathway primarily through binding to cGAS, a process inhibited by mitophagy [23]. Inhibition of p-sting and p-tbk was observed after UA treatment (Fig. 2M). We also investigated the effect of UA treatment on tumor cell autophagy (LC3B and parkin protein), but no significant changes were observed, probably due to low basal autophagy rates in tumor cell (FigS1A). These results suggested that UA treatment could reduce abnormal activation of STING and NF-κB signaling pathways, due to mitochondrial nucleic acid leakage under CM stress, by promoting mitophagy to remove damaged mitochondria in tumor macrophages, in turn suppresses pro-proliferative inflammatory factors such as IL-6.

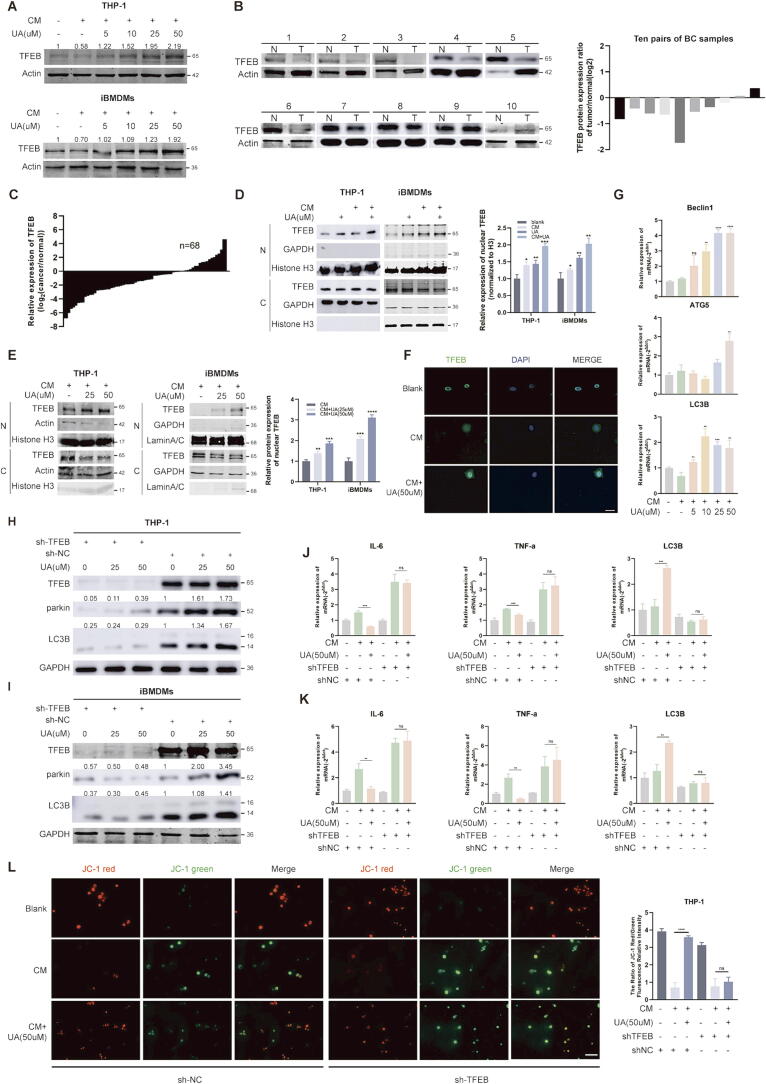

UA-mediated mitophagy is dependent on TFEB nuclear translocation

Although UA has been previously reported to primarily affect mitophagy [3], both our study and the reported literature observed a promotion of macroautophagy as well [3], so we speculated that UA affected the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes more than the generation of autophagosomes [25]. TFEB is an important regulator of autophagy and lysosomal biosynthesis [14], and the fusion of autophagosomes and lysosomes is a common pathway in both macroautophagy and mitophagy [25]. CM stress causes downregulation of macrophages’ total TFEB protein, activation of macrophage ERK phosphorylation due to tumor-derived TGF-β is one of the causes, but the exact mechanism is unknown [17], [18]. We observed that UA treatment restored protein levels of TFEB in THP-1 and immortalized murine bone marrow-derived macrophages (iBMDMs) cells (Fig. 3A). However, TFEB has been previously reported as an oncogene, we observed that overexpression of TFEB in breast cancer cells promoted proliferation, and knockdown inhibited proliferation, without much effect on tumor migratory capacity (FigS1B and C). We analyzed the TCGA database through the UALCAN platform and observed that the median expression level of TFEB in breast cancer tissues is lower than in normal tissues (FigS1D), and patients with high TFEB expression have a longer overall survival (FigS1E). We validated this in our breast cancer surgical specimens, observed that TFEB was lowly expressed in tumor tissues both protein and mRNA levels (Fig. 3B and C) and associated with tumor volumes (Table 1). IHC assays also indicated higher level of TFEB protein in adjacent cancer tissues (FigS1F). Studies showed that mice with conditional knockout of TFEB in Immune cells exhibit higher tumor burden [26]. we considered that TFEB in macrophages exerts an anticancer function. Western blot and IF assays confirmed that UA facilitated TFEB entry into the nucleus in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3D–F). Interestingly, we observed that shorter (8 h) CM treatment similarly promoted TFEB nuclear localization, which may be due to the rapid dephosphorylation of TFEB under stress conditions and the complete inability of this fraction of TFEB to scavenge the inflammatory damage caused by CM stress [27]. UA treatment promoted the transcription of TFEB target genes such as Beclin1, ATG5 and LC3B (Fig. 3G). To confirm that UA-mediated autophagy depend on TFEB, we infiltrated macrophages with viral fluids containing shRNA plasmids targeting TFEB (sh-TFEB), and set up a negative control (sh-NC). The knockdown efficiency in the RNA and protein levels was verified (FigS1G and H). Knockdown of TFEB blocked activation of macrophage LC3B and inhibition of IL-6 and TNF-α mRNA expression by UA treatment (Fig. 3H–K). Moreover, JC-1 experiments confirmed that the knockdown of TFEB abolished the effect of UA treatment attenuating mitochondrial damage under CM stress (Fig. 3L).

Fig. 3.

UA-mediated mitophagy is dependent on TFEB nuclear translocation. A TFEB protein levels in THP-1 and iBMDMs were detected by western blot after 36 h UA and CM treatment. B Comparison of TFEB protein levels in 10 pairs of breast cancer and normal tissues. (N = normal and T = tumor) C Comparison of TFEB mRNA expression levels in 68 pairs of breast cancer and normal tissues. D, E TFEB protein levels in cytoplasm and nucleus were detected by western blot after 8 h UA and CM treatment. (N = nucleus and C = cytoplasm) F An IF assay further confirmed that UA treatment affected the subcellular localization of TFEB. The fluorescence intensity ratio of the nucleus and cytoplasmic fraction was calculated using the ImageJ software. G Macroautophagy-associated mRNA levels in THP-1 and iBMDMs after 24 h UA and CM treatment were detected by real-time quantitative PCR. H, I Knockdown of TFEB followed by UA treatment and detection of LC3B, parkin, and TFEB protein levels in THP-1 and iBMDMs. sh-TFEB is the shRNA targeting TFEB, and sh-NC is the shRNA for the negative control. Not described later. J, K Knockdown of TFEB followed by UA treatment and detection of IL-6, TNF-α, LC3B mRNA levels in THP-1 and iBMDMs. L JC-1 assays were performed to detect mitochondrial membrane potential changes in THP-1. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; Student's t-test (D, E, G) and one-way ANOVA (J, K, L) were performed using Graphpad Prism. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Table 1.

The relationship between the expression of TFEB and clinicopathological variables in BC patients.

| Patients Characteristics | Total |

mRNA expression |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low(n = 34) | High(n = 34) | P value* | ||

| Age | ||||

| <60 | 29 | 14 | 15 | 0.806 |

| ≥60 | 39 | 20 | 19 | |

| TNM stage | ||||

| Ⅰ and Ⅱ | 37 | 12 | 25 | 0.002** |

| Ⅲ and Ⅳ | 31 | 22 | 9 | |

| Tumor size(cm) | ||||

| ≤2 | 36 | 9 | 27 | 0.001*** |

| >2 | 32 | 25 | 7 | |

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.595 | |||

| negative | 48 | 23 | 25 | |

| positive | 20 | 11 | 9 | |

| Distant metastasis | 0.283 | |||

| No | 59 | 28 | 31 | |

| Yes | 9 | 6 | 3 | |

The relationships between TFEB expression and patents’ clinicopathologic characteristics were analyzed via Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. * p<0.05, **p0.01,***p < 0.001.

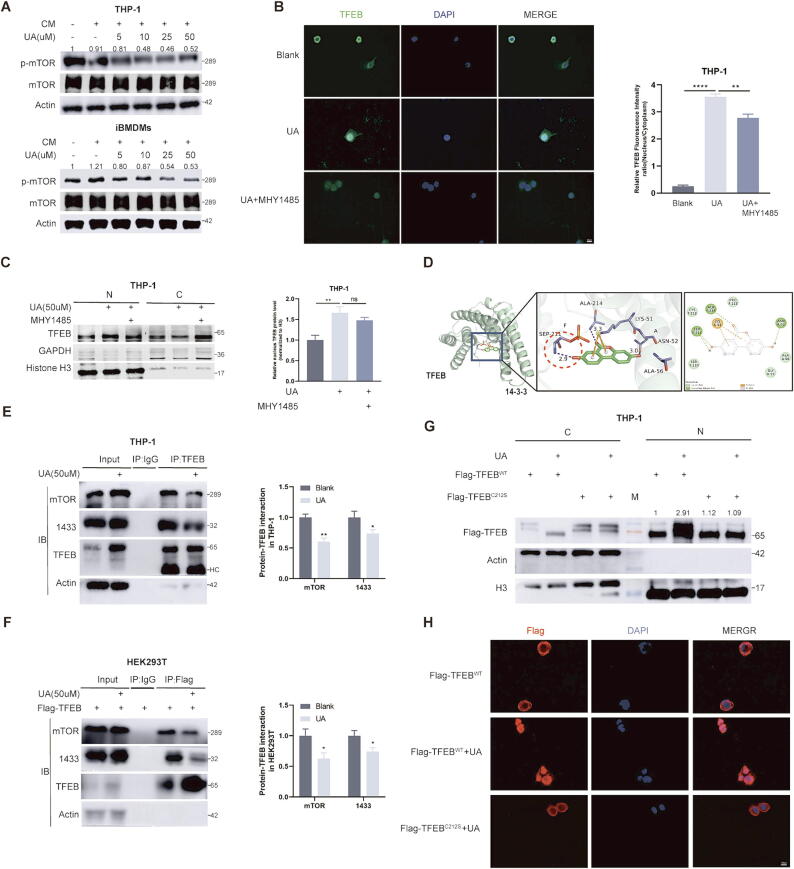

UA promotion of TFEB nuclear translocation is not completely dependent on mTOR inhibition

To better guide the clinical use of UA, we decided to further explore the potential mechanisms by which UA modulates TFEB protein. We noted that cytoplasmic and nuclear shuttling of TFEB is mainly regulated by its phosphorylation state and is affected by multiple kinases, such as GSK3B, ERK, AKT, and mTOR [28]. In addition, EIF4A3 can affect TFEB nuclear translocation by regulating GSK3B splicing [29]. We observed the inhibition of p-mTOR after UA treatment, however, the protein levels of other kinases and EIF4A3 were not significantly altered (Fig. 4A and FigS2A–C). UA inhibition of mTOR phosphorylation has been reported in previous studies on prostate cancer [6]. We added MHY1485, a potent agonist of mTOR [30], to THP-1 cells pre-treated with UA for 24 h to investigate whether UA's promotion of TFEB nuclear translocation is dependent on inhibition of mTOR phosphorylation. Unexpectedly, immunofluorescence and protein isolation assays suggested that MHY1485 treatment did not completely reverse UA-mediated TFEB nuclear translocation, although the proportion of TFEB protein in the nucleus was reduced (Fig. 4B and C). MHY1485 treatment also did not completely block the UA-mediated up-regulation of parkin (FigS2D). We hypothesized that UA might induce TFEB nuclear translocation through other mechanisms. Under physiological conditions, TFEB is highly phosphorylated, recognized by the 1433 protein and isolated in the cytoplasm. We downloaded the protein structure of the TFEB-1433 complex(6a5q) and the chemical structural formula of UA, docking in software, the results showed that one of the hydroxyl groups of UA can form a hydrogen bond with the phosphate group at the TFEB 211 site (Fig. 4D), which suggested that UA might block the recognition of TFEB phosphorylation sites by 1433. Followed by, the Co-IP experiments also demonstrated that UA treatment attenuated the binding of 1433 and TFEB in THP-1 and HEK293T (Fig. 4E and F). In addition, UA reduced cytoplasmic co-localization of TFEB and 1433 in THP-1(FigS2E). LPS-mediated cysteine alkylation of TFEB at position 212 induces TFEB nuclear localization by blocking 1433 recognition of TFEB p-S211, Mice with mutations at the same locus (C270S) lose natural antimicrobial immunity [31]. We sought to observe whether the C212S mutation reversed UA-mediated TFEB entry into the nucleus. The reliability of the mutant plasmid was first verified by transfecting wild-type and mutant plasmids in THP-1 and HEK293t cells, respectively, and treating them with LPS. It could be observed that LPS failed to induce mutant TFEB into the nucleus. (FigS2F). We subsequently observed that the C212S mutation similarly blocked UA-mediated TFEB entry into the nucleus (Fig. 4G and H), and we speculated that UA and alkylated 212 site cysteines may synergistically block 1433 recognition of TFEB (FigS3B).

Fig. 4.

UA blocks recognition of phosphorylated TFEB by 1433. A Protein levels of mTOR and p-mTOR were detected by WB after CM and UA treatment. B Immunofluorescence observation of TFEB subcellular localization. C Protein level of TFEB in the nucleus and cytoplasmic components was detected by WB. (N = nucleus and C = cytoplasm) D Molecular docking of UA and TFEB-1433 complexes using Autodock software. E, F Observe changes in TFEB and 1433 protein binding after UA treatment. (HC = heavy chain) G THP-1 cells were infiltrated with viral fluids containing wild-type (WT) TFEB and C212S mutant TFEB plasmids, and changes in TFEB protein levels in the nucleus and cytoplasm were observed by WB after UA treatment. (N = nucleus and C = cytoplasm) H THP-1 cells were infiltrated with viral fluids containing wild-type TFEB and C212S mutant TFEB plasmids, then immunofluorescence experiments were performed to observe the subcellular localization of TFEB after UA treatment. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; Student's t-test (E, F) and one-way ANOVA (B, C) were performed using Graphpad Prism. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

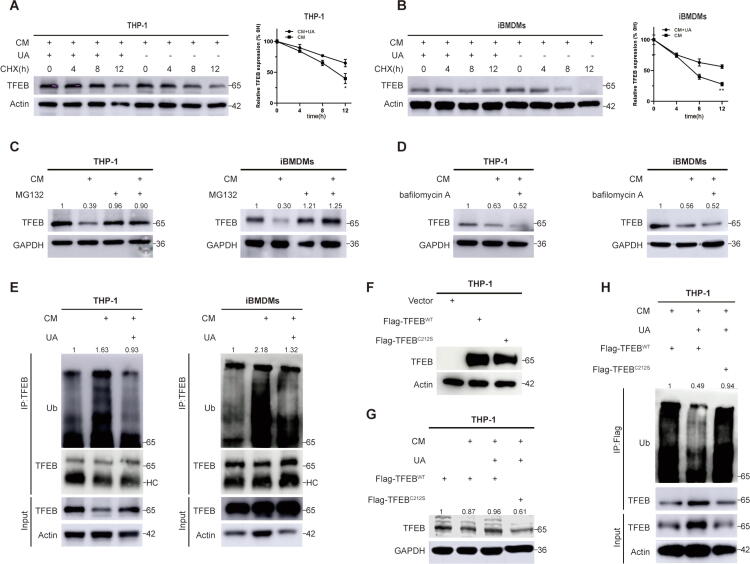

UA inhibits TFEB ubiquitination degradation under CM stress

Previous studies have found that TFEB protein levels are downregulated in tumor macrophages under CM stress [17], but the exact mechanism remains unclear. Inactivated phosphorylated TFEB is recognized and degraded by E3 ubiquitin ligase [32], and we speculated that UA rescues protein levels by inhibiting the inactivation of TFEB under CM pressure. We treated THP-1 and iBMDMs with CHX to inhibit the synthesis of new proteins [33] and observed that the UA-treated group had a longer half-life of TFEB proteins than the control group under CM stress (Fig. 5A and B), indicating that UA treatment increased protein stability of TFEB. Cells were treated with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 [34] and the autolysosome inhibitor bafilomycin A [25], respectively, under CM pressure. MG132 treatment but not bafilomycin A reversed CM stress-mediated TFEB downregulation (Fig. 5C and D), indicate that UA primarily inhibited the proteasome pathway degradation of TFEB protein [35]. The ubiquitination of TFEB protein was then detected in THP-1 and iBMDMs, and UA inhibited CM stress-induced ubiquitination of TFEB protein (Fig. 5E). We further explored the effect of the C212S mutation on the ubiquitination of the TFEB protein. Under the same viral infection conditions, the C212S mutation did not affect TFEB protein levels (Fig. 5F). However, under CM stress, the C212S mutation abolished the UA-mediated TFEB protein stabilization and ubiquitination inhibition (Fig. 5G and H). In conclusion, UA inhibited the ubiquitination degradation of TFEB by reversing the inactivation of TFEB caused by CM stress, which also explained the elevation of total TFEB protein in tumor macrophages after UA treatment (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 5.

UA inhibits TFEB ubiquitination degradation under CM stress. A, B CHX treatments were performed to observe the half-life of TFEB protein in THP-1 and iBMDMs. C, D CM pretreatment was performed for 36 h, MG132 or BAF treatment was performed, and observed the protein level of TFEB. E CM and UA were pretreated for 36 h, the lysis products were immunoprecipitated with TFEB antibody, and western blotting was performed to observe the ubiquitination level of TFEB. (HC = heavy chain) F, G THP-1 cells were infiltrated with viral fluids containing wild-type TFEB and C212S mutant TFEB plasmids. Observed the protein levels of TFEB in UA, CM-treated, and non-treated groups. H THP-1 cells were infiltrated with viral fluids containing wild-type TFEB and C212S mutant TFEB plasmids, then pretreated with CM and UA for 36 h, the lysis products were immunoprecipitated with TFEB antibody, and western blotting was performed to observe the ubiquitination level of TFEB. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; Student's t-test was performed using Graphpad Prism. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

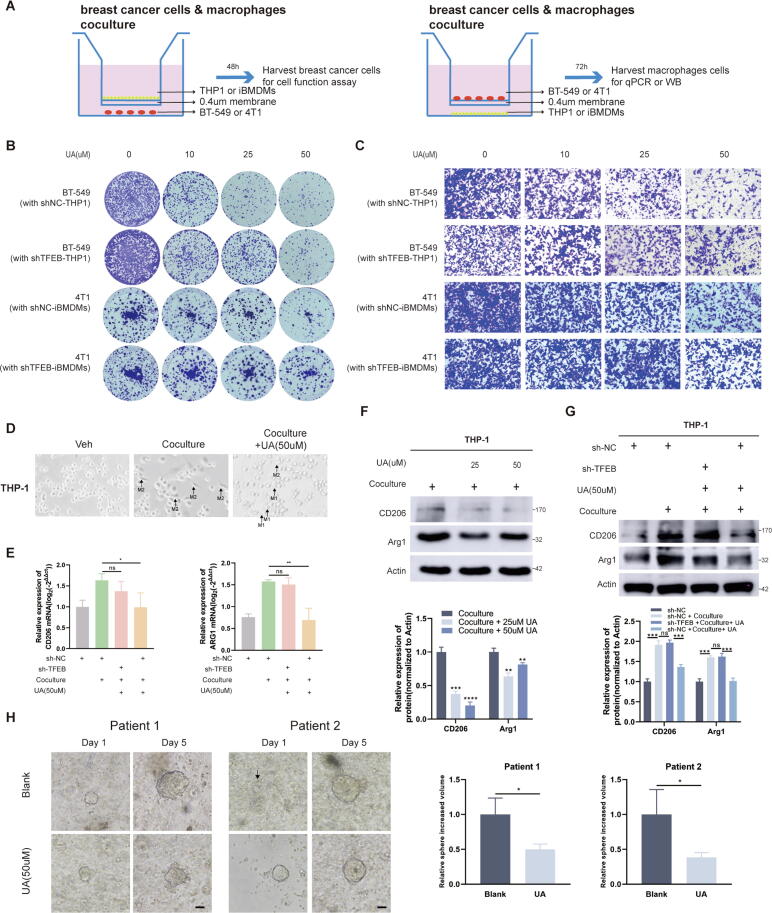

UA inhibits tumor progression in diverse breast cancer models

To reproduce the scene of tumor cell and macrophage interaction more realistically, we co-cultured macrophages (THP-1, iBMDMs) and breast tumor cells (BT-549, 4 T1) in transwell chambers, harvesting tumor or macrophage cells after different times (Fig. 6A). Colony formation and transwell migration confirmed that UA treatment in a co-culture model significantly inhibited the proliferation and migration ability of breast cancer cells in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 6B and C). Moreover, co-culturing with TFEB-knockdown macrophages appears to attenuate UA's inhibition of tumor cell proliferation and migration (Fig. 6B and C). It is commonly believed that tumor macrophage M1 polarization inhibits tumor progression [36]. In previous studies, in vivo experiments have shown that overexpression of TFEB in BMDMs reversed tumor cell-induced macrophage M2 polarization [18]. Combined anti-IL-6 therapy reduces the proportion of M2-polarized macrophages and improves the efficacy of immunotherapy [37]. TFEB knockdown affects protein levels of Arginase-1 (arg1) [17]. Given the above, we speculated that UA treatment influenced the polarization of tumor macrophages. We observed a decrease in the proportion of spindle-shaped THP-1 cells(M2) and the increase of radial cells (M1) after UA treatment in the co-culture system (Fig. 6D). We examined mRNA and protein levels of CD206 and Arg1, the indicators of M2-type macrophages. UA treatment significantly reduced the M2 polarization of tumor macrophages, but no statistically significant changes were observed in macrophages with knockdown of TFEB (Fig. 6E–G). We also constructed tumor organoids derived from patients’ tissues, and treated the model with UA. A significant difference in sphere diameter was observed on the 7th day after treatment (Fig. 6H).

Fig. 6.

UA treatment inhibits breast cancer in tumor macrophage co-culture and organoid models. A Schematic showing the cancer cells cocultured with macrophages in a transwell chamber of 0.4-um pore size. B Colony formation assays were performed to detect the proliferative capacity of BT-549 and 4 T1 cells after coculturing with macrophages and UA treatment. C Transwell migration assays were conducted to detect the migration capacity of BT-549 and 4 T1 cells after coculturing with macrophages and UA treatment. D Morphologic changes of THP-1 after co-culture and UA treatment was observed by a light microscopy. E CD206 and Arg1 mRNA levels in THP-1 were detected by real-time quantitative PCR after co-culture and UA treatment. F, G CD206, and Arg1 protein levels in THP-1 were detected by western blot after co-culture and UA treatment. H The effect of UA treatment on the growth of organoid cell spheres of origin in breast cancer patients was observed by a light microscopy (Shows images at day two and day seven). Data are presented as mean ± SEM; Student's t-test (F, H) and one-way ANOVA (E, G) were performed using Graphpad Prism. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

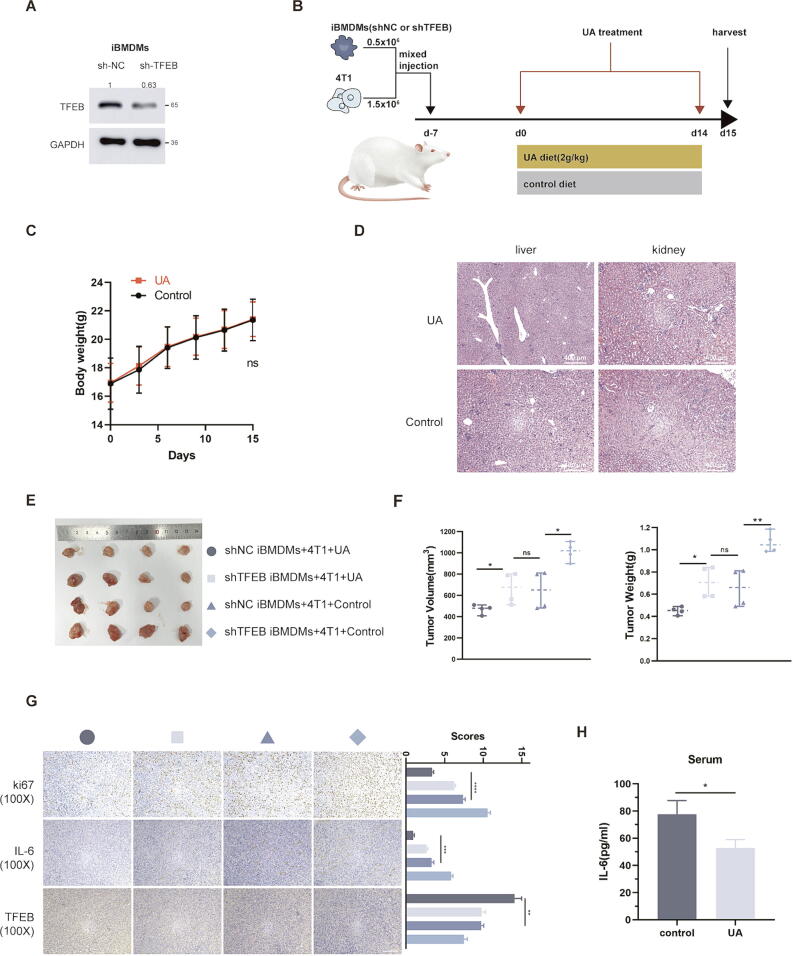

In subsequent in vivo experiments, we constructed iBMDMs cell with stable knockdown of TFEB (Fig. 7A), and referring to previous research [18] mixed tumor cells and macrophages 3:1 and injected to form subcutaneous tumors, followed by two weeks of UA treatment (Fig. 7B). UA treatment had no significant effect on body weight (Fig. 7C), and liver and kidney tissue structure (Fig. 7D) in mice, which confirmed the safety of UA treatment. In both groups mixed with sh-NC iBMDMs, UA treatment significantly reduced tumor size, however, mixing with sh-TFEB iBMDMs seemed to partially eliminate the anti-tumor effect of UA (Fig. 7E and F). Interestingly, in two groups mixed with sh-TFEB iBMDMs, UA treatment also slightly reduced tumor load, which may be related to the antiproliferative effect of UA. The IHC results suggested that UA treatment reduced the proportion of Ki67-positive (proliferative antigen) cells in tumor tissues and decreased IL-6 levels in the tumor environment (Fig. 7G). Finally, we measured the plasma IL-6 content in tumor-bearing mice after UA diet and observed a downregulation (Fig. 7H).

Fig. 7.

UA treatment inhibits tumor growth in BALB/c mice. A Constructing iBMDMs stably expressing sh-NC and sh-TFEB, knockdown efficiency was detected by western blot. B Schematic diagram of mice injected with mixed cells and treated with UA. C The weight of the mice varied with time. D HE staining of liver and kidney in UA-treated and control mice. E Tumor images for each group. F Volume and weight of tumors in each group. (The grouping is consistent with the icon of Fig. 5E) G Immunohistochemical images of various groups of tumors, including ki-67, IL-6, and TFEB, as well as scores of different indicators. (The grouping is consistent with the icon of Fig. 5E) H ELISA assay measures the IL-6 levels in mice plasma. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; Student's t-test (C, H) and one-way ANOVA (F, G) were performed using Graphpad Prism. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Conclusion

UA is known to researchers for its potent promotion of mitophagy [3], [38]. In tumor therapy, UA inhibits a wide range of cancers, as evidenced by inhibition of tumor cell proliferation and promotion of memory T cell expansion [6], [7], [8]. However, the effect of UA on breast cancer is less studied and the effect on tumor macrophages is unknown. We therefore conducted this study, to explore the positive effects and potential mechanisms of UA on breast tumor macrophages.

This study demonstrated in several breast cancer models that UA has anti-tumor effects. This was mainly manifested as a synergistic effect of inhibition of tumor cell proliferation and migration and reduction of secretion of pro-proliferative inflammatory factors by tumor macrophages. IL-6 blockade combined with immune checkpoint (ICB) therapy inhibits M2 polarization of tumor macrophages and increases the number of CD8 + killer T cells [37], but commercial recombinant human IL-6 antibody tocilizumab is not widely used in tumor combination therapy due to many adverse reactions [39]. We found that UA inhibits IL-6 secretion from tumor cells and tumor macrophages through different mechanisms (FigS3A), respectively. As a natural medicine, the safety of UA has been demonstrated in our in vivo and previous clinical trials [4]. UA combined with ICB drugs was able to increase immunotherapeutic efficacy in animal experiments [8], and our study provided the theoretical rationale for combination therapy from a novel perspective.

Macrophages are recruited around tumor cells under the influence of chemokines secreted by tumor cells. Subsequently, tumor macrophages undergo reprogramming and transform into a pro-oncogenic phenotype, secreting inflammatory factors such as IL-6 to promote tumor cell proliferation [12]. Our study found that UA helped clear damaged mitochondria under CM stress by promoting mitophagy and reducing the activation of harmful inflammatory factors due to mitochondrial nucleic acid cytoplasmic leakage. Interestingly, activation of STING can in turn upregulate TFEB proteins [40], which may be a negative feedback regulation of the organism.

TFEB is an important transcription factor regulating the biological functions of autophagosomes and lysosomes [14], [41]. We discuss the clinical significance of TFEB expression in breast cancer, where its high expression is associated with a better prognosis in our clinical cohort, which correlates with the unique function that TFEB plays in breast cancer tumor macrophages [17]. Mechanistic studies revealed that UA blocked the recognition of S211 and surrounding amino acids by the 1433 protein by forming a covalent bond with the phosphorylated serine at the TFEB 211 site, facilitating TFEB entry into the nucleus and reducing TFEB inactivation due to CM stress. In contrast to previous studies [17], we found that shorter CM intervention conditions exhibited increased TFEB entry into the nucleus as well as a slight activation of autophagy. However, under longer CM stress, macrophages exhibited TFEB inactivation and overall inhibition of autophagy. The C212S mutation eliminates the role of UA in promoting TFEB entry into the nucleus. We surmised that in wild-type TFEB, the alkylated cysteine at site 212 masked a small portion of the protein region recognized by the 1433 protein on TFEB, which did not affect the phosphorylation level of serine at site 211 [31]. After UA treatment, covalent bond formation blocks more of the 1433 protein-recognized region. However, in the case of the C212S mutation, the region originally masked by the cysteine alkyl group is re-exposed and recognized by the 1433 protein resulting in cytoplasmic segregation of TFEB (FigS3B).

In the future, the role of the TFEB C212S mutation on tumorigenesis and development still needs to be verified in animal and cellular experiments. UA in combination with other first-line drugs for breast cancer therapy deserves to be developed in clinical trials.

Declarations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

All data and materials are available upon request by contacting the corresponding author.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 82073204 to LF), the Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (no. 202040157 to LF) and the Shanghai Tenth People’s Hospital (No. YNCR2B008 to LF).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

ZBW and FL designed the study. ZBW and WYY conducted the experiments and wrote the manuscript. WYY and ZBA analyzed the data. ZXQ directed the details of the experiment and supervised the study. LDY, QFY, and YDR collected the breast cancer tissues. ZBW and WYY contributed equally to this study. All authors have reviewed and approved the paper.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the helpful comments on this paper received from the reviewers.

Authors' information

Nothing.

Competing interests

We have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2024.04.010.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Giaquinto A.N., Sung H., Miller K.D., Kramer J.L., Newman L.A., Minihan A., et al. Breast cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022 doi: 10.3322/caac.21754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng T., Liu H., Hong Y., Cao Y., Xia Q., Qin C., et al. Promotion of liquid-to-solid phase transition of cGAS by baicalein suppresses lung tumorigenesis. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:133. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01326-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryu D., Mouchiroud L., Andreux P.A., Katsyuba E., Moullan N., Nicolet-Dit-Félix A.A., et al. Urolithin a induces mitophagy and prolongs lifespan in C. elegans and increases muscle function in rodents. Nat Med. 2016;22:879–888. doi: 10.1038/nm.4132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh A., D’Amico D., Andreux P.A., Fouassier A.M., Blanco-Bose W., Evans M., et al. Urolithin a improves muscle strength, exercise performance, and biomarkers of mitochondrial health in a randomized trial in middle-aged adults. Cell Rep Med. 2022;3 doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohammed Saleem Y.I., Albassam H., Selim M. Urolithin a induces prostate cancer cell death in p53-dependent and in p53-independent manner. Eur J Nutr. 2020;59:1607–1618. doi: 10.1007/s00394-019-02016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Totiger T.M., Srinivasan S., Jala V.R., Lamichhane P., Dosch A.R., Gaidarski A.A., et al. Urolithin a, a novel natural compound to Target PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2019;18:301–311. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-18-0464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghosh S., Singh R., Vanwinkle Z.M., Guo H., Vemula P.K., Goel A., et al. Microbial metabolite restricts 5-fluorouracil-resistant colonic tumor progression by sensitizing drug transporters via regulation of FOXO3-FOXM1 axis. Theranostics. 2022;12:5574–5595. doi: 10.7150/thno.70754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denk D., Petrocelli V., Conche C., Drachsler M., Ziegler P.K., Braun A., et al. Expansion of T memory stem cells with superior anti-tumor immunity by urolithin A-induced mitophagy. Immunity. 2022;55:2059–2073.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2022.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mulder K., Patel A.A., Kong W.T., Piot C., Halitzki E., Dunsmore G., et al. Cross-tissue single-cell landscape of human monocytes and macrophages in health and disease. Immunity. 2021;54:1883–1900.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nalio Ramos R., Missolo-Koussou Y., Gerber-Ferder Y., Bromley C.P., Bugatti M., Núñez N.G., et al. Tissue-resident FOLR2+ macrophages associate with CD8+ T cell infiltration in human breast cancer. Cell. 2022;185:1189–1207.e25. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qiu S.-Q., Waaijer S.J.H., Zwager M.C., de Vries E.G.E., van der Vegt B., Schröder C.P. Tumor-associated macrophages in breast cancer: innocent bystander or important player? Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;70:178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei C., Yang C., Wang S., Shi D., Zhang C., Lin X., et al. Crosstalk between cancer cells and tumor associated macrophages is required for mesenchymal circulating tumor cell-mediated colorectal cancer metastasis. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:64. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-0976-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weng Y.-S., Tseng H.-Y., Chen Y.-A., Shen P.-C., Al Haq A.T., Chen L.-M., et al. MCT-1/miR-34a/IL-6/IL-6R signaling axis promotes EMT progression, cancer stemness and M2 macrophage polarization in triple-negative breast cancer. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:42. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-0988-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Settembre C., Di Malta C., Polito V.A., Garcia Arencibia M., Vetrini F., Erdin S., et al. TFEB links autophagy to lysosomal biogenesis. Science. 2011;332:1429–1433. doi: 10.1126/science.1204592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slade L., Biswas D., Ihionu F., El Hiani Y., Kienesberger P.C., Pulinilkunnil T. A lysosome independent role for TFEB in activating DNA repair and inhibiting apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Biochem J. 2020;477:137–160. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20190596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Di Malta C., Zampelli A., Granieri L., Vilardo C., De Cegli R., Cinque L., et al. TFEB and TFE3 drive kidney cystogenesis and tumorigenesis. EMBO Mol Med. 2023;15:e16877. doi: 10.15252/emmm.202216877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Y., Hodge J., Liu Q., Wang J., Wang Y., Evans T.D., et al. TFEB is a master regulator of tumor-associated macrophages in breast cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8:e000543. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-000543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fang L., Hodge J., Saaoud F., Wang J., Iwanowycz S., Wang Y., et al. Transcriptional factor EB regulates macrophage polarization in the tumor microenvironment. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1312042. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1312042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vini R., Jaikumar V.S., Remadevi V., Ravindran S., Azeez J.M., Sasikumar A., et al. Urolithin a: a promising selective estrogen receptor modulator and 27-hydroxycholesterol attenuator in breast cancer. Phytother Res. 2023 doi: 10.1002/ptr.7919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.González-Sarrías A., Miguel V., Merino G., Lucas R., Morales J.C., Tomás-Barberán F., et al. The gut microbiota ellagic acid-derived metabolite urolithin a and its sulfate conjugate are substrates for the drug efflux transporter breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2/BCRP) J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61:4352–4359. doi: 10.1021/jf4007505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson D.E., O’Keefe R.A., Grandis J.R. Targeting the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signalling axis in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15:234–248. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2018.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones S.A., Jenkins B.J. Recent insights into targeting the IL-6 cytokine family in inflammatory diseases and cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18:773–789. doi: 10.1038/s41577-018-0066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sliter D.A., Martinez J., Hao L., Chen X., Sun N., Fischer T.D., et al. Parkin and PINK1 mitigate STING-induced inflammation. Nature. 2018;561:258–262. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0448-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 24.Huang X., Yao Y., Hou X., Wei L., Rao Y., Su Y., et al. Macrophage SCAP contributes to metaflammation and lean NAFLD by activating STING-NF-κB signaling pathway. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;14:1–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2022.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mizushima N., Yoshimori T., Levine B. Methods in mammalian autophagy Research. Cell. 2010;140:313–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang X., Li S., Malik I., Do M.H., Ji L., Chou C., et al. Reprogramming tumour-associated macrophages to outcompete cancer cells. Nature. 2023 doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06256-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Medina D.L., Di Paola S., Peluso I., Armani A., De Stefani D., Venditti R., et al. Lysosomal calcium signalling regulates autophagy through calcineurin and TFEB. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:288–299. doi: 10.1038/ncb3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Puertollano R., Ferguson S.M., Brugarolas J., Ballabio A. The complex relationship between TFEB transcription factor phosphorylation and subcellular localization. EMBO J. 2018:37. doi: 10.15252/embj.201798804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sakellariou D., Tiberti M., Kleiber T.H., Blazquez L., López A.R., Abildgaard M.H., et al. eIF4A3 regulates the TFEB-mediated transcriptional response via GSK3B to control autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2021;28:3344–3356. doi: 10.1038/s41418-021-00822-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi Y.J., Park Y.J., Park J.Y., Jeong H.O., Kim D.H., Ha Y.M., et al. Inhibitory effect of mTOR activator MHY1485 on autophagy: suppression of lysosomal fusion. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43418. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Z., Chen C., Yang F., Zeng Y.-X., Sun P., Liu P., et al. Itaconate is a lysosomal inducer that promotes antibacterial innate immunity. Mol Cell. 2022;82:2844–2857.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2022.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sha Y., Rao L., Settembre C., Ballabio A., Eissa N.T. STUB 1 regulates TFEB -induced autophagy–lysosome pathway. EMBO J. 2017;36:2544–2552. doi: 10.15252/embj.201796699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schneider-Poetsch T., Ju J., Eyler D.E., Dang Y., Bhat S., Merrick W.C., et al. Inhibition of eukaryotic translation elongation by cycloheximide and lactimidomycin. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:209–217. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kisselev AF. Site-Specific Proteasome Inhibitors. Biomolecules 2021;12:54. 10.3390/biom12010054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Wang Y., Le W.-D. Autophagy and ubiquitin-proteasome system. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1206:527–550. doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-0602-4_25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Väyrynen J.P., Haruki K., Lau M.C., Väyrynen S.A., Zhong R., Dias Costa A., et al. The prognostic role of macrophage polarization in the colorectal cancer microenvironment. Cancer Immunol Res. 2021;9:8–19. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-20-0527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hailemichael Y., Johnson D.H., Abdel-Wahab N., Foo W.C., Bentebibel S.-E., Daher M., et al. Interleukin-6 blockade abrogates immunotherapy toxicity and promotes tumor immunity. Cancer Cell. 2022;40:509–523.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2022.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang J., Zhang M., Chen Y., Sun Y., Gao Z., Li Z., et al. Urolithin a ameliorates obesity-induced metabolic cardiomyopathy in mice via mitophagy activation. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2023;44:321–331. doi: 10.1038/s41401-022-00919-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hibler B.P., Markova A. Treatment of severe cutaneous adverse reaction with tocilizumab. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:785–787. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu Y., Sun Q., Zhang C., Ding M., Wang C., Zheng Q., et al. STING-IRG1 inhibits liver metastasis of colorectal cancer by regulating the polarization of tumor-associated macrophages. iScience. 2023;26 doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2023.107376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tan A., Prasad R., Lee C., Jho E.-H. Past, present, and future perspectives of transcription factor EB (TFEB): mechanisms of regulation and association with disease. Cell Death Differ. 2022;29:1433–1449. doi: 10.1038/s41418-022-01028-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data and materials are available upon request by contacting the corresponding author.