Graphical abstract

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, Aging, Sympathetic, β1-adrenergic receptor, Sirt6, Exosomes

Highlights

-

•

Our findings revealed a significant increase in sympathetic activity, for example, NE levels, in various mouse models of osteoarthritis, including natural aging, medial meniscus instability, and load-induced models.

-

•

Notably, alterations in the expression levels of β1-adrenergic receptor and SIRT6 were observed in chondrocytes of naturally aging osteoarthritis mouse models.

-

•

Our study highlights the role of sympathetic innervation in driving the transfer of exosomal miR-125 from osteoarthritic chondrocytes.

-

•

Our study found that sympathetic innervation leading to the disruption of subchondral bone homeostasis and exacerbation of cartilage damage in aging mice.

-

•

These findings shed light on the potential contribution of sympathetic regulation to the pathogenesis of aging-related osteoarthritis.

Abstract

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a progressive disease that poses a significant threat to human health, particularly in aging individuals: Although sympathetic activation has been implicated in bone metabolism, its role in the development of OA related to aging remains poorly understood. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate how sympathetic regulation impacts aging-related OA through experiments conducted both in vivo and in vitro.

Methods

To analyze the effect of sympathetic regulation on aging-related OA, we conducted experiments using various mouse models. These models included a natural aging model, a medial meniscus instability model, and a load-induced model, which were used to examine the involvement of sympathetic nerves. In order to evaluate the expression levels of β1-adrenergic receptor (Adrβ1) and sirtuin-6 (Sirt6) in chondrocytes of naturally aging OA mouse models, we performed assessments. Additionally, we investigated the influence of β1-adrenergic receptor knockout or treatment with a β1-adrenergic receptor blocker on the progression of OA in aging mice and detected exosome release and detected downstream signaling expression by inhibiting exosome release. Furthermore, we explored the impact of sympathetic depletion through tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) on OA progression in aging mice. Moreover, we studied the effects of norepinephrine(NE)-induced activation of the β1-adrenergic receptor signaling pathway on the release of exosomes and miR-125 from chondrocytes, subsequently affecting osteoblast differentiation in subchondral bone.

Results

Our findings demonstrated a significant increase in sympathetic activity, such as NE levels, in various mouse models of OA including natural aging, medial meniscus instability, and load-induced models. Notably, we observed alterations in the expression levels of β1-adrenergic receptor and Sirt6 in chondrocytes in OA mouse models associated with natural aging, leading to an improvement in the progression of OA. Critically, we found that the knockout of β1-adrenergic receptor or treatment with a β1-adrenergic receptor blocker attenuated OA progression in aging mice and the degraded cartilage explants produced more exosome than the nondegraded ones, Moreover, sympathetic depletion through TH was shown to ameliorate OA progression in aging mice. Additionally, we discovered that NE-induced activation of the β1-adrenergic receptor signaling pathway facilitated the release of exosomes and miR-125 from chondrocytes, promoting osteoblast differentiation in subchondral bone.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study highlights the role of sympathetic innervation in facilitating the transfer of exosomal miR-125 from osteoarthritic chondrocytes, ultimately disrupting subchondral bone homeostasis and exacerbating cartilage damage in aging mice. These findings provide valuable insights into the potential contribution of sympathetic regulation to the pathogenesis of aging-related OA.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a chronic degenerative disease that mainly affects the elderly population, leading to joint pain and dysfunction. Furthermore, this condition is the primary cause of sports-related injuries in humans [1]. At present, OA affects an astounding 30 billion people worldwide, imposing a significant economic burden [2]. As the global population continues to age, the incidence of OA has substantially increased [3]. Despite its high prevalence and associated disability, OA lacks effective treatment options. Surgical intervention remains the only choice for patients with advanced knee OA, However, there was no significant improvement in disease progression [4]. Therefore, further searching for the pathogenesis and treatment of OA is of great significance in the diagnosis and treatment of OA. Recent advancements in our understanding of the pathogenesis of OA have revealed that it is not solely a joint disorder but is also influenced by other systems, such as the gut microbiota [5] and neuromodulation [6]. Consequently, exploring interorgan communication shows promise in identifying potential therapeutic strategies for OA.

The theory of neuromodulation in OA was introduced over 130 years ago [7]. Given the widespread distribution of sympathetic nerves in synovial, cartilaginous, and subchondral bone sites, it is conceivable that improving neural conditions could significantly impact the progression of OA in the context of normal aging [8]. Substantial evidence now supports the notion of altered sympathetic tone in individuals with OA [9]. Sympathetic tension is a state of excitation of the sympathetic nervous system that manifests itself in physiological responses such as muscle tension, increased heart rate, and elevated blood pressure in various parts of the body[10], [11]. A higher sympathetic tone has been associated with a low-grade inflammatory state due to neutrophils and inflammatory mediators in patients with OA [12]. In the case of OA, a degenerative joint disease, synovitis worsens as significant damage to capillary and neuronal networks occurs, favoring a sympathetic response over sensory fibers. This shift is primarily attributed to increased expression of the β2 adrenergic receptor (Adrb2) in the articular vasculature [13]. Conditional knockout of the Adrb2 gene in mice has revealed that osteoblasts are the primary cell type regulating.bone formation in response to sympathetic activity [14]. In our previous study, we also found that sympathetic nerves play a vital role in heart failure leading to osteoporosis [15]. The β1 adrenergic receptor (Adrb1) altered sympathetic innervation which handling in pharmacotherapeutic desensitization observed in arthritis[16]. However, there is a lack of research on the role of β1-adrenergic receptors in OA.

The OA is regulated by various environmental factors, including communication pathways between chondrocytes and osteoblasts, indicating significant bone-cartilage crosstalk [17], [18]. Additionally, aberrant molecular events at the subchondral bone (SCB), such as increased levels of pro-osteoclastogenic factors, nerve growth factors, and local extracellular vesicles, have been identified to regulate SCB remodeling aberrations, potentially influencing bone-cartilage crosstalk and impacting cartilage degeneration during the initiation and progression of OA [19]. Intercellular communication within OA can also be facilitated by extracellular vesicles (EVs), particularly exosomes, which are small membranous particles of endocytic origin that typically measure less than 100 nm in diameter [20], [21]. Emerging evidence suggests that SCB remodeling orchestrated by osteoclasts precedes the degradation of articular cartilage, playing a crucial role in the onset and advancement of OA [22]. However, the specific factors responsible for directly mediating bone-cartilage crosstalk in the development of OA remain unclear.

Sirtuin-6 (Sirt6) is a member of the sirtuin family of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD)NAD + -dependent enzymes and possesses conserved core catalytic structural domains. SIRT6 plays important roles in a variety of aging diseases, including apoptosis, inflammation, senescence, glucose metabolism and fatty acid metabolism [23]. Furthermore, Sirt6 plays a role in modulating leptin signaling and regulating energy metabolism in pro-opiomelanocortin neurons [24]. Overexpression of Sirt6 specifically in hypothalamic pro-opiomelanocortin neurons exacerbates diet-induced obesity and metabolic disorders through the hypothalamus-adipose axis [25]. Additionally, targeted regulation of Sirt6 has been shown to ameliorate chondrocyte senescence in OA by reducing systemic inflammation [26]. Targeted therapies aimed at Sirt6 function could represent a novel strategy to slow or stop OA[27]. Consequently, sympathetic nerves may ameliorate the progression of OA through the sirt6 signaling pathway [28], [29].

To investigate the role of sympathetic nerves in OA progression, we used senescent mice as a model. Our study focused on analyzing changes in sympathetic nerve activity and NE levels in different mouse models of OA, as these factors play crucial roles in the regulation of sympathetic nerve activity. Our findings revealed a significant increase in both NE levels and sympathetic nerve activation in senescent mice with DMM, another model of OA. Furthermore, we observed that sympathetic innervation plays a role in aiding the transfer of exosomal miR-125 from chondrocytes affected by OA. This process leads to a reduction in Sirt6 expression, which in turn disrupts subchondral bone balance, worsening cartilage damage.

Materials and methods

Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with ethical policies and procedures approved by the ethics committee of our hospital and the institutional review board (IRB) (DSYY6420-032), adhering to applicable regulations such as the U.K. Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986, associated guidelines, EU Directive 2010/63/EU for animal experiments, or the National Research Council’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Mouse strains and constructions

The aging male C57BL6/J mice, were obtained from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd were housed in a standard animal facility under controlled environmental conditions. They were provided with ad libitum access to fresh water and standard laboratory chow. The experimental protocol underwent review and approval by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Shanghai Tenth People’s Hospital affiliated with Tongji University (DSYY-6420–032).

Aging male C57BL6/J mice were obtained from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd at 2 months and 14 months of age. Prior to their arrival, the mice were maintained on a regular mouse diet (Teklad Irradiated 18 % protein and 6 % fat diet-2918), which closely resembled their diet at Jax 5 K52 (18 %-19 % protein and 6 %-7% fat). The mice were aged until they reached 18 months when the treatment phase began. All experiments investigating lifespan and health span were initiated around the 18th month of age. Mice deficient for Adrβ1 (JAX no. 003810) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory and crossed with WT C57BL/6 mice to generate Adrβ1−/− mice, which were utilized at 14 months of age. Genotyping of the mice was performed using PCR analysis with tail samples.

OA modeling and in vivo treatment

The study aimed to investigate the impact of the sympathetic nervous system on OA development using three mouse models in the first part. The first model involved a naturally aging mouse model spanning two months and fourteen months to induce OA. The second model induced OA in mice using the destabilization of the medial meniscus (DMM) model. Lastly, the third model generated OA using mechanical loading techniques. In all, the study population was divided into six groups: the young group(n = 9) and aging group (n = 9), Sham group(n = 9), DMM group (n = 9), vehicle group and the loading group (n = 9) and they were raised for eight weeks which following the methodology described in earlier studies [5], [30].

For OA induction by DMM, after the mice were anaesthetized, a medial articular incision was made to expose the left joint cavity, and then the tibial collateral ligament was transected. Finally, the articular incision was closed. In the control group, only the joint cavity was opened[31].

For OA induction through mechanical loading, a two-week loading regimen was conducted using an electronic material testing machine (Bose 3100). The mice were 12 weeks old at the beginning of the loading process and were placed under general anesthesia (3.5 % isoflurane). The right tibia was vertically positioned between two custom-made loading cups that restricted the knee and ankle joints in deep flexion. Axial compressive loads were applied through the knee joint via the upper loading cup, while a loading cell attached to the lower cup measured and monitored the applied loads.

Each loading cycle consisted of a 9.9-second holding time with a load magnitude of 2 N (required to maintain knee position). Subsequently, a maximum load of 9 N or 11 N was applied for 0.05 s, with a rise and fall time of 0.025 s each, forming a 10-second trapezoidal wave loading cycle. This loading cycle was repeated 40 times within one loading episode. During the loading regimen, this loading episode was repeated three times per week for eight consecutive week[32].

Secondly, to investigate the impact of propranolol on OA development, we added propranolol (Sigma) to the drinking water at a concentration of 500 mg mL−1 until the mice were euthanized. The mice were randomly assigned to one of four groups: i) young + vehicle (2 month old, saline, N = 9), ii) young + propranolol(2 month old, 500 mg mL − 1 propranolol, N = 9), iii) older + vehicle (14 month old, saline, N = 9), and iv) older + propranolol (2 month old, 500 mg mL − 1 propranolol, N = 9).

Finally, a thermoresponsive and injectable formulation containing 6-OHDA (H4381, Sigma Aldrich, USA) and guanethidine was developed to reduce the levels of NE in the endosteum area. The formulation utilized the sustained drug release properties of the hydrogel, which was based on Pluronic F127 (HP) mixed with 6-OHDA/guanethidine at a 3:7 ratio. The formulation was then injected into the articular cavity of the right knee. The experiment involved five groups of mice: young + vehicle, older + vehicle, older + F127/vehicle, older + F127/6-OHDA, and older + F127/guanethidine. All mice received intra-right knee articular cavity injections at 3 days and were sacrificed at 12 days after breastfeeding.

The drugs and compounds used in this study were propranolol (Prop), NE, Pluronic F127, 6-hydroxydopamine hydrochloride (6-OHDA), and guanethidine monosulfate. Dosages and time courses are specified in the corresponding text and figure legends.

Micro-CT analysis

This study utilized the Inveon micro-CT imaging system by Siemens, with a spatial resolution of 55 kVp and 145 mA, an integration time of 300 ms, and a 6-mm isotropic voxel edge. The specific region of interest analyzed was the medial tibial plateau, which is located superior to the growth plate, posterior to the insertion of the anterior cruciate ligament, and medial to the midline of the intercondylar notch. Morphometric assessments were performed on the subchondral bone in this region, focusing on parameters such as bone volume over total volume (BV/TV), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), trabecular number (Tb.N), and trabecular spacing (Tb.Sp), following previously established methods [5], [33].

Cell culture and transfection

This study employed microdissection of the articular cartilage in the medial femoral condyle of mice with knee OA using a surgical microscope. This technique allowed us to isolate the articular cartilage without affecting the underlying subchondral bone. We obtained macroscopically damaged cartilage specimens from the affected region of the medial femoral condyle in human patients with OA and extracted primary chondrocytes from the dissected articular cartilage through enzymatic digestion. The dissected cartilage was washed with PBS and incubated at 37 °C for 15 min in trypsin-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid solution. Subsequently, we digested the cartilage with collagenase (2 mg/mL) at 37 °C for 2 h in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin. We carried out the entire process in a 5 % CO2 atmosphere.

During the cell culture period, we maintained the chondrocytes at 37 °C in a humidified environment containing 5 % CO2 and 95 % air, changing the culture medium every 2–3 days. For all experiments, we used first-passage chondrocytes when they reached 85 % confluence.

To investigate this topic, we constructed pCDNA3.1-Adrβ1 and pCDNA3.1-Adrβ1 vectors (Invitrogen) by synthesizing and subcloning the Adrβ1 sequence into the pCDNA3.1 vector. We used pCDNA3.1-Adrβ1/pCDNA3.1-flag-Adrβ1 to achieve the overexpression of Sirt6 through transfection, while an empty pCDNA3.1 vector served as a control (Invitrogen).

To study the effects of Adrβ1, we transfected chondrocytes with negative control siRNA or siRNA targeting Adrβ1 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at a concentration of 50 nM using Lipofectamine 3000 Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

SA–β-gal staining

We conducted SA–β-gal staining following the established protocol described in reference [34], employing an SA-β-gal Staining Kit (K320-250, BioVision) and following the manufacturer’s instructions. We identified senescent cells (SnCs) as cells exhibiting a blue stain under light microscopy. To determine the percentage of SA-β-gal + cells, we counted the total number of cells in 10 random fields per culture dish using a nuclear DAPI counterstain.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence analysis was conducted by fixing cells in 4 % paraformaldehyde for 30 min post-treatment. In vitro treatment with NE and ICI-118551 was performed as previously described. Primary osteocytes were exposed to 50 µm NE, 100 µm NE, 100 µm NE + 50 µm metoprolol, and 100 µm NE + 100 µm metoprolol for 30 min, followed by three washes with cold PBS.

Cultured cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies, including rabbit MMP-13 (Cell Signaling, #69926, 1:200), rabbit Sirt6 (Cell Signaling, #12486, 1:100), and phospho-ROS1 (Cell Signaling, #3078, 1:100). After washing with PBS, the cells were treated with corresponding fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibodies and DAPI (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific H3569, 1:500) for 1 h at room temperature. The cells were then observed and measured using an Olympus DP72 microscope (Olympus Scientific Solutions Americas, Inc., Waltham, MA).

Cell viability assay

For analysis of cell viability, the cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay was used. Mouse chondrocytes (1 × 104/well) were cultured in 96-well plates for 24 and 48 h. Following experimental treatment, the cells were incubated with CCK-8 solution (10 μL) for 2 h at room temperature.

Histomorphometry

To evaluate the severity of OA, knees were treated with 10 % ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) for 14 days to undergo decalcification. After decalcification, the knees were embedded in paraffin and sliced into 5 µm frontal sections. The stained sections were then examined under a stereomicroscope (SMZ745T, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) after being subjected to HE staining, Safranin-O/Fast Green staining, immunofluorescence, scanning electron microscopy, and HE staining again. Protein expression in the knee tissue was detected using antibodies against MMP-13 and Sirt6 (ab39012, Abcam). The Osteoarthritis Research Society International histology score approach (OARSI) was used to evaluate the severity of OA in the cartilage [35].

Hind limb responsiveness

Hind limb responsiveness was evaluated using a hotplate set at 55 °C. The latency period for hind limb response, characterized by jumping or paw licking, was measured as the time taken to respond before surgery and at 2 and 4 weeks after surgery for all animal groups [36]. Three readings were taken per mouse, and the average response time was calculated.

RT‐qPCR and miR-125 expression analysis

For RT-qPCR and miR-125 expression analysis, chondrocytes were isolated by removing muscle and connective tissue and then flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Gene expression levels including Adrβ1, Adrβ2, Sirt6, Matrix Metallopeptidase 13(MMP-13), Interleukin 1 Beta (IL-1β), Collagen Type I Alpha 2 Chain(Col1A2), Adrα1, and Adrα2 were assessed.

MicroRNAs from serum, media and exosomes were extracted using the miRNeasy Serum/Plasma Kit (217184, Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The expression of NE was quantified using a high-sensitivity NE ELISA kit (Cat# NOU39-K01, Eagle Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

ELISA

Tissue preparation was conducted following a similar protocol to RT–qPCR detection. Mice from each group were sacrificed and their knee joints were carefully dissected. Soft tissue was removed by scraping and both epiphyses were excised. Subsequently, 2 ml of cold PBS was used to flush out the synovial fluid with a syringe. Articular cartilage was then cut and homogenized into a powder form. The expression of NE was quantified using a high-sensitivity NE ELISA kit (Cat# NOU39-K01, Eagle Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The weight of the bone chips was matched to quantify the protein concentration and normalize the NE measurements.

Western blotting

For Western blotting, chondrocytes were seeded at a density of 5*105 cells per well in six-well plates and allowed to adhere for 48 h. Afterward, cells from different treatment groups were extracted using RIPA lysis buffer (Boster, China, AR0102) with 1 % phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and 1 % phosphatase inhibitor cocktail while keeping them on ice for 30 min. The resulting extract was then collected and centrifuged at 12,000 g and 4 °C for 30 min. Following centrifugation, the supernatant was collected, and protein concentrations in each sample were determined using a BCA assay kit (Boster, China, AR0146). Protein samples were separated using SDS-PAGE and subsequently transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore, USA). After blocking with 5 % skim milk at room temperature for 1 h, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with specific primary antibodies followed by a 1-hour incubation at room temperature with secondary antibodies. Protein bands were visualized using a chemiluminescence reagent (Boster, China), and images were captured using a Bio-Rad scanner (Hercules, CA, USA).

RNA‐sequence analysis

RNA-sequence analysis was performed on total RNA extracted from chondrocyte samples using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Purity and quantity of obtained RNA samples were assessed using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer. The integrity of RNA was evaluated using the RNA Nano6000 Assay Kit on the Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). Each sample contained 1 μg of RNA which served as input for subsequent analysis. After obtaining total RNA from chondrocyte samples, cDNA synthesis was carried out in subchondral bone using the TaqMan MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (4366596, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Megaplex RT Primers (4399970, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Subsequently, array analysis was performed on the 7900HT Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using the TaqMan MicroRNA Array Rodent Card A (4398967, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (4352042, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The expression of microRNAs represented by Ct values was normalized to the expression of U6 (△Ct values) using the standard Gaussian distribution, and fold changes in normalized data were recorded for comparison between groups.

Purification of extracellular vesicles

To purify extracellular vesicles, chondrocytes were cultured until they reached nearly 100 % confluence. Subsequently, they were incubated in EV-depleted medium (supernatants of complete medium after overnight centrifugation at 100,000 g) for 48 h. Exosomes were isolated from the supernatants using a differential centrifugation protocol at 4 °C: 300 × g for 10 min, 3000 × g for 10 min, 10,000 × g for 20 min, and 100,000 × g for 70 min. The isolated exosomes were washed with PBS and subjected to another centrifugation step at 100,000 × g for 70 min. The size distribution of exosomes was determined using dynamic light scattering (DLS) with a Nanosizer instrument (ZEN3790, Malvern Instruments, UK), as previously described [37]. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed on isolated exosomes deposited on copper mesh for visualization. The samples were stained with phosphotungstic acid, washed with distilled water, and dried prior to imaging using TEM [38]. The quantification of exosomes was accomplished by measuring the concentration of total proteins using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay (23225, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Finally, the exosomes were labeled using PKH26 according to the manufacturer’s protocol (MINI26, Sigma-Aldrich, USA).

Inhibition of exosomal release

To inhibit exosomal (EV) release, the OME compound (PHR1059, Sigma Aldrich, USA) was prepared in DMSO and applied at a concentration of 20 µg mL − 1 to treat cultured cells for 24 h [39].

Transfection of siRNAs and MicroRNA mimics

For transfection of siRNAs and MicroRNA Mimics, siRNAs targeting mouse miR-125 were designed by Gima (Suzhou, China), with the scramble siRNA serving as the negative control (NC). The cells were incubated in Opti-MEM (31985–070, Invitrogen, USA) for 6 h and then transfected with siRNAs at a concentration of 50 nm using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX Reagent (13778–100, Invitrogen, USA) for 48 h. For the mimics and negative control (NC) of miR-125, as well as Cy3-labeled miR-125, the design was carried out by RiboBio (Guangzhou, China). These were transfected into the cells using Lipofectamine 2000 Reagent (11668030, Invitrogen, USA) at a final concentration of 50 nm for 24 h [40].

Transmission electron microscopy

Transmission electron microscopy was performed by subjecting EV preparations (10 µL) to three quick rinses in PBS on carbon-coated copper grids with a mesh size of 400 (Electron Microscopy Sciences). After removal of excess solution and time for drying, the grids were examined using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (JEM 1010, JEOL, Japan) operated at 80 kV to obtain TEM images. The size of the EVs was determined using ImageJ.

Chondrocyte and co-culture with osteoblasts

For chondrocyte and co-culture with osteoblasts experiments, chondrocytes were incubated for 24 h. The nonadherent cells were collected and seeded in plates and cultured in α-MEM with 10 % FBS, 2 mm L-glutamine, 100 U mL − 1 penicillin, 100 g mL − 1 streptomycin, and 20 ng mL − 1 macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M−CSF) (315–02, Peprotech, USA) in a humidified atmosphere with 5 % CO2 at 37 °C. After 3 days, the adherent cells were utilized as chondrocyte cells (CCs). For co-culture experiments, osteoblasts were seeded either in plates or in the upper chamber of the Transwell system. The chondrocyte cells were then seeded at a ratio of 10:1 onto the osteoblasts or in the bottom chamber of the Transwell system. The cells were cultured in the presence of NE (HY-13715, MCE, USA) for 7–10 days [41].

Molecular modeling and docking

In this study, we conducted a docking analysis of Adrβ1 and Sirt6 as previously described. The crystal structure of Sirt6 was aligned with that of Adrβ1 using the ChEMBL database (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/#). We performed the docking study using CB-Dock software (https://clab.labshare.cn/cb-dock/php/index.php), and the resulting docking configurations were visualized with CB-Dock software [42].

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, we presented all values as mean ± standard deviation (SD). A p value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We analyzed the data using GraphPad Prism 8.02 (La Jolla, California, USA), and applied one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple test. To ensure reproducibility, we repeated each experiment three times [5], [33].

Results

Sympathetic nerve activity is increased in aging mice, mice with DMM and mice with mechanical loading

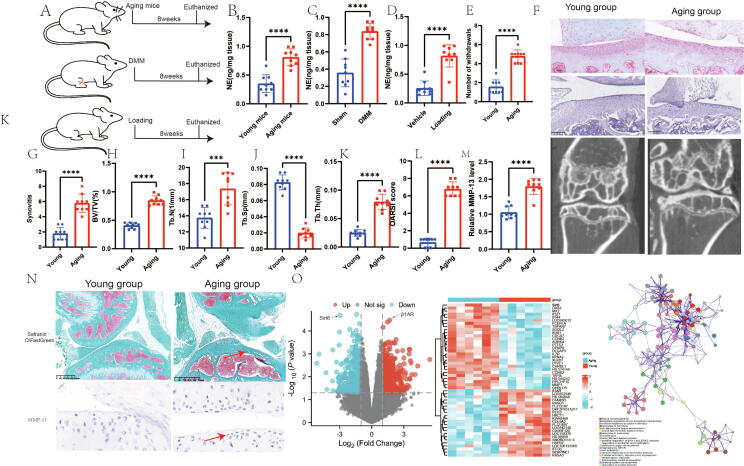

To determine whether sympathetic nerve activity influences the progression of OA, we measured NE levels in naturally aging mice, mice with DMM, and mice subjected to mechanical loading after an 8-week intervention period (Fig. 1A-D). The results showed a significant increase in NE levels in the articular cartilage of aging mice, mice with DMM, and mechanically loaded mice.

Fig. 1.

Sympathetic nerve activity is increased in aging osteoarthritic mice, as well as those treated with DMM mice and loading mice. A schematic diagram illustrating the three mouse models used in the study: natual aging; DMM mice; loading mice. B, Representative graphs of Micro-CT, HE staining, and toluene blue staining; C, number of withdraws; D, synovitis; E, BV/TV; F, Tb.N; G, Tb.Sp; H, Tb.Th; I, OARSI score; J, relative MMP-13 level; K, NE level in aging group; L, NE level in DMM experiment; M, NE level in loading experiment; N, Representative graphs of immunohistochemistry and Safranin-O/FastGreen staining; O, Results of chondrocyte RNA sequencing and functional enrichment analysis in aging mice. N = 9. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed student’s t-test. BV/TV: Percent trabecular area; Tb.Sp: trabecular separation; Tb.Th: trabecular thickness; Tb.N: trabecular number; DMM: destabilized medial meniscus; OARSI: Osteoarthritis Research Society International histology score approach; NE: norepinephrine. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

We discovered that sympathetic nerve activity is elevated in aging mice, mice with DMM, and mice subjected to mechanical loading. To investigate the progression of OA in naturally aging mice, we employed micro-CT, HE staining, and Safranin-O/Fast Green staining techniques. Our results revealed significant increases in synovitis, the number of withdrawals, BV/TV, Tb.N, Tb.Th, OARSI score, and relative MMP-13 level in aging mice compared to those of young mice. Conversely, Tb.Sp was decreased in aging mice (Fig. 1F-N).

Furthermore, we performed RNA sequencing on chondrocytes and observed decreased Sirt6 expression along with a significant increase in β-adrenergic 1 receptor levels. Signaling pathway enrichment analysis indicated a potential association with cell proliferation (Fig. 1O). These findings indicate that increased sympathetic nerve activity in OA is linked to chondrocyte damage and subchondral bone ossification.

Aging-induced OA is ameliorated by β-blockers

In our previous research, we discovered that sympathetic nerve activity plays a role in regulating target cells by releasing NE from nerve endings [15]. To explore the impact of heightened sympathetic nerve activity on the progression of OA, we opted to administer the nonselective beta-blocker (Propranolol, Prop) to naturally aging mice with OA. By employing micro-CT analysis to assess alterations in subchondral bone, we observed that there were no significant changes in subchondral bone in young mice before and after Prop treatment. However, in naturally aging mice, there was a notable decrease in BV/TV, Th.b, and TB.Th, accompanied by a significant increase in Tb.Sp (Fig. 2A-E).

Fig. 2.

Aging-induced osteoarthritis is ameliorated by β-blockers. A, Representative graphs of Micro-CT, HE staining, toluene blue staining, immunohistochemistry and Safranin-O/FastGreen staining. B, BV/TV; C, Tb.N; D, Tb.Th; E,Tb.Sp; F, OARSI score; G, number of withdraws; H, synovitis; I, osteophyte maturity score; J, ostephyte score; K, relative MMP-13 expression; L, Relatve mRNA expression. N = 9. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed student’s t-test. BV/TV: Percent trabecular area; Tb.Sp: trabecular separation; Tb.Th: trabecular thickness; Tb.N: trabecular number; DMM: destabilized medial meniscus; OARSI: Osteoarthritis Research Society International histology score approach; NE: norepinephrine. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

These micro-CT findings were consistent with the Safranin‐O/Fast Green staining results, which indicated a significant reduction in OARSI scores as well (Fig. 2F). Moreover, we discovered that the Prop intervention did not lead to a substantial improvement in the number of withdrawals in naturally aging mice. Furthermore, by analyzing the pathology results and micro-CT, we determined that there was a significant decrease in synovial inflammation, osteophyte scores, and osteophyte maturity scores after intervention with Prop in aging mice (Fig. 2H-K).

To further investigate changes in gene expression related to articular cartilage, we conducted PCR analysis, revealing a significant decrease in the levels of β1AR and β2AR receptors, while the level of the Sirt6 gene appeared to be significantly increased (Fig. 2L). Collectively, these findings suggest that β-adrenergic receptors may play an important role in sympathetic intervention in OA progression.

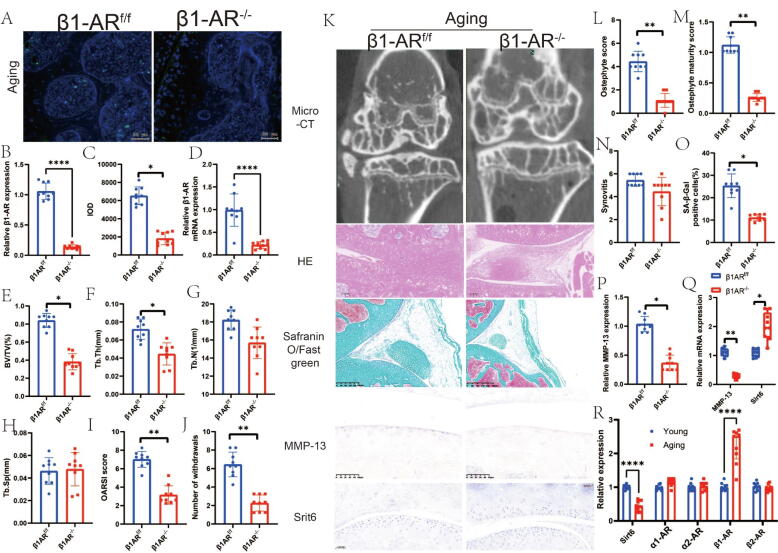

β1-adrenoceptor deletion in chondrocytes reduces progression of aging OA

β1-adrenoceptor deletion in chondrocytes reduces the progression of aging OA. In a previously conducted study, researchers discovered that intervention with NE activates signaling pathways at either α or β adrenergic receptors to effectively regulate the expression of downstream genes. Additionally, previous findings indicated that the utilization of adrenergic receptor blockers led to an improvement in adrenoceptor expression. To further confirm the role of β1 adrenergic receptor signaling, subsequent to its blockade, in inducing the progression of OA through downstream hyposynaptic signaling, we employed Arβ1 knockout mice. The results obtained through RT–PCR and immunofluorescence analysis of Arβ1 provided solid evidence for the successful knockout of Arβ1 in chondrocytes (Fig. 3A-D).

Fig. 3.

Knocknout of adrb1 in aging induced oa. a, representive images of immunofluorescence staining and quantitative analysis of adrb1 in aging mice(a-c). d, relative β1ar mrna expression. e, bv/tv; f,Tb.Th; G, Tb.N; H, Tb.Sp; I, OARSI score; J, number of withdraws; K, Representative graphs of Micro-CT, HE staining, toluene blue staining, immunohistochemistry and Safranin-O/FastGreen staining. L, osteophyte maturity score; M, ostephyte score; N, synovitis; O, SA-β-Gal positive cells; P, relative MMP-13 expression; Q, relative mRNA expression in knocknout of Adrb1 in aging mice; R, relative expression in young and aging mice. N = 9. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed student’s t-test. BV/TV: Percent trabecular area; Tb.Sp: trabecular separation; Tb.Th: trabecular thickness; Tb.N: trabecular number; DMM: destabilized medial meniscus; OARSI: Osteoarthritis Research Society International histology score approach; NE: norepinephrine; Adrb1: The adrenergic receptors beta 1. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Using micro-CT analysis, we determined that knockout of the Arβ1 receptor in naturally aging mice significantly reduced subchondral bone BV/TV. Moreover, Tb.Th exhibited a considerable decrease. Pain analysis and pathological observations strongly suggested a significant decrease in OARSI (Osteoarthritis Research Society International) scores, the number of withdrawn osteophytes, and the maturity scores of osteophytes (Fig. 3E-N).

We proceeded to examine the phenotypic changes in cellular senescence by employing SA-β-Gal staining, which revealed that knockdown of the Arβ1 receptor resulted in a notable reduction in senescence-related phenotypic changes (Fig. 3O). Additionally, the knockdown of Arβ1 displayed a remarkable decrease in MMP-13 immunostaining results, while Sirt6 results exhibited a significant increase. These findings were consistent when examining mRNA levels in chondrocytes (Fig. 3P-Q). Furthermore, our investigation discovered a significant decrease in Sirt6 mRNA, along with a noteworthy increase in Arβ1 mRNA, in the phenotype of naturally aging mice (Fig. 3R). These outcomes strongly suggest that β1-adrenergic receptor signaling within chondrocytes plays a pivotal role in regulating OA progression.

NE-activated Arβ1 signaling regulates OA progression through Sirt6

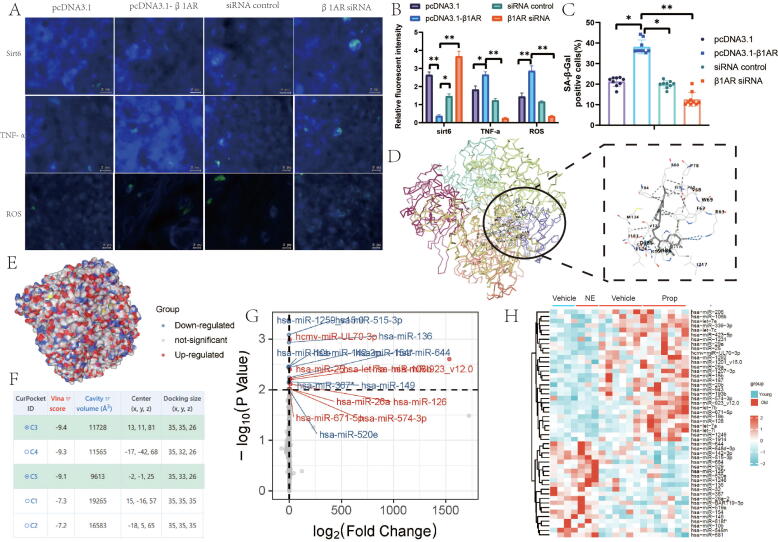

Subsequently, we delved deeper into the downstream effects subsequent to β1-adrenergic receptor intervention. Silencing the β1-adrenergic receptor resulted in a substantial increase in sirt6 levels, whereas activating the β1-adrenergic receptor led to a significant decrease in sirt6 levels (Fig. 4A-B). These findings align with the outcomes of our earlier animal experiments.

Fig. 4.

β1-adrenoceptor deletion in chondrocytes reduces progression of aging osteoarthritis. A, Representive images of immunofluorescence staining of Sirt6, TNF-α, ROS. B, relative fluorescent intensity. C, SA-β-Gal positive cells; D,E, docking model between Ardb1 and Srit6. F. Vina score of docking model. G-H, MicroRNA array analysis of mouse tibia subchondral bone samples. Mice were injected with either NE or Prop into Sham mice. N = 9. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed student’s t-test. BV/TV: Percent trabecular area; Tb.Sp: trabecular separation; Tb.Th: trabecular thickness; Tb.N: trabecular number; DMM: destabilized medial meniscus; OARSI: Osteoarthritis Research Society International histology score approach; NE: norepinephrine; Adrb1: The adrenergic receptors beta 1.

SA-β-Gal staining results indicated that the depletion of β1-adrenergic receptors markedly ameliorated the senescent characteristics of chondrocytes, whereas the activation of β1-adrenergic receptors enhanced chondrocyte senescence (Fig. 4C). To investigate the molecular interaction between the β1-adrenergic receptor and sirt6, we conducted molecular docking experiments, yielding a Vina score of −9.4 (Fig. 4D-F). These findings collectively indicate that NE intervention via β1-adrenergic receptors can decrease the expression of Sirt6, thereby improving the levels of inflammatory factors and oxidative stress in cartilage.

Sympathetic stimulation of miR-125-responsive pathways in the subchondral bone of naturally aging mice

In a prior investigation, we observed pronounced ossification in the subchondral bone of naturally aging mice. Consequently, we sought to further elucidate the mechanisms underlying the regulation of subchondral bone ossification by the sympathetic nervous system. Subsequently, we explored the responsiveness of microRNAs to sympathetic-adrenergic stimuli in naturally aging-related OA by conducting microRNA array analysis on the subchondral bone of mice. The results revealed the regulation of multiple microRNAs by NE and Propranolol injections in both young and senescent mice, with miR-125 exhibiting the most prominent upregulation in response to NE. Furthermore, in the aging context, Propranolol was capable of inducing miR-125 expression (Fig. 4G-H).

Subsequently, we examined the alterations in the senescent phenotype of subchondral bone osteoblasts following NE- and Propranolol -mediated modulation of miR-125 expression. Our findings demonstrated that both NE and NE in combination with miR-125 significantly augmented the senescent phenotype, whereas knocking down miR-125 led to a significant reduction in cellular senescence compared to that of the miR-125-supplemented group (Fig. 5A-B). These results strongly indicate that sympathetic activation triggered by NE intervention may influence the activity of subchondral bone osteoblasts through the involvement of miR-125.

Fig. 5.

NE-mediated sympathetic activation promotes the transfer of miR125 from chondrocyte exosomes to osteoblasts in subchondral bone. A, Representive images of immunofluorescence staining in miR125 and miR125 KO treatment. B, SA-β-Gal positive cells; C, Representative diagram of electron microscope; D, particles size of exosome. E-F, Western blot of CD9, CD63 and CD81, which were marker of exosome. F, MiR-125 expression levels in chondrocyte and their conditional culture media. N = 3 per group. G, MiR-125 expression levels in chondrocyte conditional culture media and serum of mice. NE was treated in vitro at 10 μm for 24 h, or in vivo at 10 mg kg − 1 day − 1 intraperitoneal injection for 1 month. N = 3 per group. H, MiR-125 expression levels in chondrocyte conditional media, chondrocyte exosomes (Exos), and chondrocyte conditional media deprived of extracellular vesicles (EVs). Quantity of collected chondrocyte exosomes was determined by protein contents. ISO was treated in vitro at 10 μm for 24 h. N = 3–4 per group. J, exosome miR-125 in 0, 50, 100 and 500 μm NE treatment. K, miR-125 in 0, 50, 100 and 500 μm NE treatment. L, Relative mRNA expression in 0 μm and 500 μm NE treatment. M, cell viability; N, f) miR-125 expression levels in chondrocyte in Transwell co-culturing of osteoblasts at 10:1 with chondrocyte, with 20 ng mL − 1 M−CSF, 10 nm Vitamin D3, and 1 μm PGE2. osteoblasts were derived from Adrβ1 knock-out mice and chondrocyte were derived from WT mice. NE was treated at 10 μm for 24 h. N = 3 per group. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed student’s t-test. BV/TV: Percent trabecular area; Tb.Sp: trabecular separation; Tb.Th: trabecular thickness; Tb.N: trabecular number; DMM: destabilized medial meniscus; OARSI: Osteoarthritis Research Society International histology score approach; NE: norepinephrine; Adrb1: The adrenergic receptors beta 1.

NE-mediated sympathetic activation promotes the transfer of miR-125 from chondrocyte exosomes to osteoblasts in subchondral bone

The above results indicate that NE intervention significantly affects changes in miR-125 levels in osteoblasts in the subchondral bone, but we also found that NE intervention had no significant effect on adrenergic receptors in the subchondral bone (Fig. 5K), suggesting that intercellular regulatory mechanisms may play an important role in this process. Therefore, we speculate that NE-mediated sympathetic activation may transfer miR-125 from chondrocytes to the subchondral bone to play a regulatory role. To test the above hypothesis, we first analyzed whether miR-125 could be secreted by chondrocytes, and RT–PCR analysis showed that miR-125 was present in the culture medium of chondrocytes. In addition, miR-125 levels in chondrocyte culture medium as well as in mouse serum were significantly increased under NE stimulation.

Next, we investigated whether exosomes, one of the EV populations released by the cells, were able to transport chondrocyte miR-125. Chondrocyte exosomes were successfully isolated by continuous centrifugation and ultracentrifugation and verified by morphological and size distribution characteristics. The results showed that although almost all secreted chondrocyte miR-125 was present in EVs, exosomes accounted for at least a fraction of the released miR-125. Furthermore, although the number of chondrocyte exosomes was not affected, NE stimulation increased exosomal miR-125 levels.

To investigate whether chondrocyte-derived miR-125 could be transferred to osteoblasts, we employed a Transwell coculture system in which miR-125-deficient chondrocytes were used to exchange culture medium with osteoblasts. The results revealed an elevated presence of the mature form of miR-125 in osteoblasts subjected to Transwell coculture with chondrocytes (Fig. 5f). Notably, the facilitation of chondrocyte miR-125 transfer to osteoblasts was significantly enhanced by NE stimulation. Importantly, when Adrβ1-deficient or miR-125-deficient osteoblasts were used in Transwell coculture, the effect of NE on the transfer of miR-125 to osteoblasts was blocked. To examine the role of exosomes in miR-125 transfer and the potential influence of chondrocyte miR-125 transfer on the physiological status of osteoblast miR-125, exosomes were collected from different chondrocytes and treated with WT osteoblasts. The findings revealed that chondrocyte exosomes increased osteoblast miR-125, which was further amplified by NE pretreatment of chondrocytes. Additionally, the effect of exosomes from Adrβ1-deficient and miR-125-deficient osteoblasts was diminished (Fig. 5C-N). The results from this portion of the study indicate that NE-induced sympathetic activation is mediated by the trans-exosomal transfer of chondrocyte miR-125 into osteoblasts of the subchondral bone.

The role of Sirt6 in NE intervention during sympathetic activation

To gain further insights into the effects of NE-activated sympathetic nerves, we conducted interventions using Sirt6 activators and inhibitors (Fig. 6A). We observed that the use of the Sirt6 inhibitor OSS128167 significantly increased the expression of β1-adrenoceptor, while the use of the Sirt6 activator UBCS039 decreased β1-adrenoceptor expression. The mRNA results displayed similar patterns, with the Sirt6 inhibitor OSS128167 significantly enhancing the expression of MMP-13, IL-1β, and Col1A2 mRNA, whereas the use of the Sirt6 activator UBCS039 decreased their expression (Fig. 6A-C).

Fig. 6.

Depletion of TH + Sympathetic Nerves mitigates osteoarthritis progression in aging mice. A, Immunohistochemistry representative image of MMP-13 with treated with NE, OSS128167, UBCS039. B, SA-β-Gal positive cells; C, Relative mRNA expression of MMP-13, IL-1β, Col1A2; D, Representative graphs of Micro-CT, HE staining, toluene blue staining, immunohistochemistry and Safranin-O/FastGreen staining. E, NE level in tibial chondrocyte determined by ELISA in young and aging mice with different treatments. F, BV/TV; G, Tb.N; H, Tb.Sp; I, Tb.Th; J, OARSI score; K, number of withdraws. L, ostephyte score; M,osteophyte maturity score; N, synovitis; O, relative MMP-13 expression; P, relative Col1A2 expression. N = 9. Date are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was determined by two tailed student’s t-test. BV/TV: Percent trabecular area; Tb.Sp: trabecular separation; Tb.Th: trabecular thickness; Tb.N: trabecular number; DMM: destabilized medial meniscus; OARSI: Osteoarthritis Research Society International histology score approach; NE. norepinephrine; Adrb1: The adrenergic receptors beta 1. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Depletion of TH + sympathetic nerves mitigates OA progression in aging mice

To further confirm the role of sympathetic innervation in ameliorating the progression of OA, we conducted interventions using a temperature-sensitive hydrogel as a vehicle. We selected two neurointerventional drugs, namely, oxidized dopamine (6-OHDA) and guanethidine, to target sympathetic nerves and inhibit the release of NE from sympathetic nerve endings, respectively.

A representative result, depicted in Fig. 6D, demonstrates a substantial increase in NE levels in senescent mice, which is consistent with previous findings. However, following the intra-articular injection of 6-OHDA and guanethidine, NE levels showed a significant decrease compared to those of the senescent mice. Utilizing micro-CT to assess subchondral bone conditions, we observed that senescent mice treated with 6-OHDA and guanethidine exhibited significant reductions in BV/TV (bone volume fraction) and Tb.N (trabecular number), while Tb.Sp (trabecular separation) also significantly decreased in response to the interventions. In terms of the number of withdrawals, both 6-OHDA- and guanethidine-treated mice showed a significant decrease compared to senescent mice. However, when evaluating osteophyte scores, osteophyte maturity scores, and synovitis, neither sympathetic nerve depletion agent demonstrated significant improvement compared to senescent mice.

Moreover, safranin‐O/Fast Green staining indicated that 6-OHDA and guanethidine interventions significantly reduced Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) scores compared to those of senescent mice. Finally, we examined the levels of MMP-13 and Col1A2 in chondrocytes and discovered that MMP-13 levels were significantly increased in senescent mice, while 6-OHDA and guanethidine interventions led to a significant reduction in MMP-13 levels. In conclusion, these results suggest that the elimination of sympathetic nerves or inhibition of intra-articular NE release can decelerate the progression of aging-related OA.

Discussion

In this study, we used senescent mice as an animal model to investigate the involvement of sympathetic nerves in the progression of OA. Our findings indicate a significant increase in sympathetic nerves during natural aging. NE activates β1-adrenergic receptor signaling in chondrocytes while inhibiting the aging phenotype mediated by Sirt6. OA progression involves changes in cartilage damage and subchondral bone conditions [17], [43], [44]. However, the regulation of the sympathetic nervous system between cartilage and subchondral bone remains unknown. Our findings suggest that activation of sympathetic nerves by NE stimulates chondrocytes to secrete exosomes and express miR-125, promoting increased activity of osteoblasts in the subchondral bone. These results indicate that sympathetic nerves exacerbate the senescent phenotype of Sirt6 through β1-adrenergic receptors while driving the progression of OA by stimulating chondrocytes to secrete exosomes and miR-125.

The aging process is increasingly recognized as a significant challenge for humankind. Chronic overactivity of the nervous system is associated with aging [45]. Our previous study explored the role of sympathetic activity in the heart-bone axis and highlighted the importance of adrenergic receptors [15]. In older individuals, there is a higher level of sympathetic nerve activity and a stronger connection between sympathetic nerve activity and blood pressure, contributing to the increased risk of hypertension with age [46]. Sympathetic modulation of synaptic release mediated by beta1- and alpha2B-adrenergic receptors in motor neurons of aged mice has been shown to ameliorate nerve damage [47]. Sarcopenia, characterized by an age-related decline in muscle mass, force, and power, is regulated by the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), which also influences the structure and function of the neuromuscular junction [48]. Furthermore, our study revealed a significant increase in NE levels in the joint cavity of senescent mice.

Sirt6, a protein involved in cellular stress response and aging-related processes, has been found to be downregulated in chondrocytes in aging-related OA [26]. Restoring or enhancing the expression of Sirt6 has been shown to ameliorate OA progression in mouse models[49], [50]. The exact signaling pathways through which Sirt6 exerts its protective effects are still under investigation but may involve the regulation of inflammation, oxidative stress, and cellular senescence. Increased expression of Sirt6 found to significantly improve OA progression in our study.

The skeletal system plays a crucial role in protecting the health of the organism [20], [51]. With the advancement of multiorgan interaction research, the brain-sympathetic-bone axis has been proposed, highlighting the major impact of sympathetic innervation on the regulation of bone metabolism [52]. Sympathetic control is crucial in various systemic and local regulatory conditions, including synovial tissue, subchondral bone and marrow, meniscus, ligaments and tendons, and adipose tissue [53]. This study aims to enhance our understanding of the involvement of sympathetic contributions in cartilage by identifying the role of elevated NE levels in age-related OA, thereby suggesting an important mechanism for regulating aging-related diseases through sympathetic receptors.

The influence of sympathetic activation on bone metabolism in the context of aging-related OA are adrenergic receptors, neurotransmitters and neuropeptides, sympathetic innervation and inflammatory pathways[8], [12], [54], [55], [56], [57]. Sympathetic receptors have a significant impact on cartilage degeneration. A model of temporomandibular arthritis showed an increase in both β2-adrenoceptor gene and protein levels [58], [59]. NE inhibits the synthesis of cartilage extracellular matrix components and chondrogenic differentiation through β2-adrenergic receptor signaling in proliferating chondrocytes with OA [54]. β2-adrenergic receptor signaling contributes to a nonproliferative, metabolically stable articular chondrocyte phenotype and may counteract the progression of OA. Conversely, α1-adrenergic receptor activity promotes chondrocyte proliferation and apoptosis, potentially exacerbating the pathogenesis of OA [60]. Nevertheless, our study reveals a significant upregulation of β1-adrenergic receptors in senescent mice, particularly within chondrocytes expressing primarily β1-adrenergic receptors. In various age-related diseases, including OA, there is a notable increase in the expression of β1-adrenergic receptors [61], [62], [63], [64], [65]. The deep interactions between the immune system and the nervous system are now well documented [66]. Immune cells and innate immune cells maintain the function and homeostasis of the nervous system, and an imbalance in this balance, e.g., due to chronic inflammation, can lead to severe damage[67]. NE inhibits the production of cytokines, such as TNFα expressed by monocytes, macrophages, and microglia in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) components of the bacterial cell wall, and inhibits the production of IL-1β or IL-6. Norepinephrine has a direct effect on innate immune cells, increasing circulating NK and granulocyte[68]. The use of beta adrenergic receptor blockers leads to downregulation of beta adrenergic expression, which leads to upregulation of alpha adrenergic receptors[69], [70]. In the cardiovascular system, propranolol is a nonselective β1- and β2-adrenergic receptor blocker that slows heart rate, weakens myocardial contractility, and reduces cardiac output, initially due to a reflexive increase in peripheral resistance (which causes a relative enhancement of α-receptor action), as evidenced by an up-regulation of α-adrenergic receptor expression and a down-regulation of β-adrenergic receptor expression[71], [72]. Similar patterns have been found in bone metabolism-related diseases[73], [74], [75]. In our previous study it was found that the use of sympathetic neurochemolectomy agents increased α-adrenoceptor expression and β1-adrenoceptor expression, but decreased β2-adrenoceptor levels[15].

OA overlap many molecular mechanisms of cartilage destruction[53]. Wear and tear in cartilage is chondrocyte-mediated, where chondrocytes act both as effector and target cells. Beta adrenergic receptors have been studied in osteoarthritic diseases, with more studies on adrenergic β2[76], [77], but less on adrenergic β1. Hyun Ah Kim et al. found that the influence of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) on metabolism of bone and β-ARs is a regulator of cartilage catabolism induced with IL-1β[78]. NE affects chondrocytes from OA cartilage regarding inflammatory response and its cell metabolism in a dose dependent manner which was show Adrenergic beta 1 plays an important role in this[60]. NE decreased the apoptosis rate of chondrocytes by stimulating β1-AR[79]. In addition, In patients with temporomandibular disorder may frequently involve dysregulation of beta-adrenergic activity that contributes to altered cardiovascular and catecholamine responses and to severity of clinical pain[80]. Ana et al. found that the use of beta1-blockers is associated with less joint pain and a lower use of opioids and other analgesics in individuals with symptomatic large-joint OA[81]. Sympathetic nerves play an important role in the regulation of OA, including effects on cartilage, subchondral bone chicken synovium[82], [83]. The presence of TH + was examined in chondrocyte cultures of neonatal mice. During the progression of OA, nerve fibers sprout into articular cartilage[58]. Hence, our research investigated the impact of sympathetic activation caused by NE intervention on cartilage damage in aging mice. We discovered that sympathetic activation exacerbates the progression of OA, whereas silencing of adrenergic β1 receptors alleviates the advancement of OA associated with aging.

Recently, the autonomic nervous system's role in regulating subchondral bone remodeling in OA has gained increased attention [84]. This interest stems from observed alterations in sympathetic nerve fibers, neurotransmitters, and adrenergic receptor levels during the progression of OA [58]. Notably, in osteoblasts obtained from newborn mice's calvariae, only the expression of the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2-AR) gene could be detected [14]. In various animal models, studies have demonstrated that increased mechanical stress leads to sprouting of tyrosine hydroxylase-positive (TH + ) nerve fibers in subchondral bone. Similarly, in a rat model of unilateral anterior crossbite (UAC), sprouting of TH + fibers and an elevation of NE levels were observed in the temporomandibular joint's subchondral bone without affecting systemic serum NE concentration [85].

These findings have shed light on the complex nature of sympathetic regulation in cartilage. Therefore, our study aimed to investigate the context-dependent control of cartilage by the sympathetic nervous system. Surprisingly, we uncovered a mechanism involving microRNAs and exosomes, wherein sympatho-adrenergic activation induces chondrocyte-mediated osteoblastogenesis through messenger transfer [86]. The transcriptional mediation of the miR-125 response in chondrocytes by Sirt6 contributes to our understanding of β1-adrenergic receptor signaling. Previous studies focusing on knee osteoarthritic cartilage and healthy articular cartilage have demonstrated that miR-125 is downregulated in osteoarthritic cartilage and directly regulates ADAMTS-1 through IL-4β activation [87]. Our study further elucidated the role of exosomes secreted by chondrocytes, which contain miR-125 and play a crucial role in transporting miR-125 to osteoblasts in the subchondral bone.

Articular cartilage tissue exists within a complex microenvironment comprising not only chondrocytes but also various nonchondrocyte cell types, including adipocytes, synoviocytes, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), endothelial cells, and immune cells [88]. Cells can self-renew and/or produce differentiated cells basically through the following two ways: first, by proliferation of stem cells producing differentiated cells, by de- and subsequently by re-differentiation or by trans-differentiation, or second, by proliferation of pluripotent progenitor cells producing differentiated progeny cells or by different lineage-restricted progenitor cells each of them producing different differentiated cells[89]. For example, during mouse embryogenesis, all osteochondral germ cells, as well as progenitor cells in various tissues, are derived from precursors expressing Sox9[90]. Both cell lineages originate from osteochondral progenitor cells, which originate from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in the bone marrow and differentiate into either osteoblasts or chondrocytes[91]. It is because of this same origin that the interaction between cartilage and subchondral bone is now of increasing interest[92]. Cartilage damage repair by enabling reprogramming of chondrocytes and osteoblasts[93].These cellular components interact with each other through the secretion of various metabolic and inflammatory factors via paracrine, autocrine, and endocrine pathways to maintain the homeostasis of articular cartilage. Unfortunately, this delicate balance is severely disrupted in OA. Emerging evidence suggests that altered communication between chondrocytes and surrounding tissues can influence the progression of OA directly or indirectly [94]. One crucial mediator of intercellular communication is exosomes, an essential subset of extracellular vesicles (EVs), which facilitate the exchange of proteins, mRNAs, and microRNAs [95], [96]. Notably, exosomes have been extensively investigated for their regulatory roles in tissue homeostasis and their potential as therapeutic agents for various diseases [97]. The joint cavity, encompassing chondrocytes and synoviocytes, represents a complex environment where establishing an intricate intercellular communication network among resident cells is essential for joint health [98]. Zheng et al., notably found that the transfer of miR-125b from young fibroblasts to aging fibroblasts via exosomes promotes fibroblast migration and counteracts senescence [99]. This miR-125b molecule acts as a negative regulator of the inflammatory chemokine CCL4, and its decreased abundance is partially responsible for the age-related increase in CCL4 [100]. Additionally, Hu et al. found that sympathetic neurostress drives the transfer of exosomal miR-21 from osteoblasts, disrupting bone homeostasis and promoting osteopenia [26]. Furthermore, other studies have revealed that chondrocytes release EVs containing multiple active molecules that contribute to anabolic bone regulation. Exosome-like vesicles derived from chondrocytes affected by OA may represent a novel biological factor that triggers the activation of inflammatory pathways and promotes the production of mature IL-1β in macrophages. Furthermore, these exosome-like vesicles derived from osteoarthritic chondrocytes were found to enhance the synthesis of mature IL-1β in macrophages. Mechanistically, these vesicles exerted their effects by inhibiting the expression of ATG5B through the action of miR-4a-449p, resulting in the suppression of macrophage autophagy elicited by LPS stimulation [101]. Further investigations into the neural regulation of exosomal protein and microRNA contents are warranted, as they may help elucidate exosomal secretion and its role in mediating intercellular communication following innervation.

Limitations

There are several limitations in our study, firstly there is no clinical sample in this study and there is a need to incorporate clinical research components in future studies to demonstrate the role of adrenergic receptors in OA. Secondly, the study in this study mainly looked at the effect of β-adrenergic receptors and further studies are needed for the functional role of α-adrenergic receptors.

Conclusion

Our study highlights the role of sympathetic innervation in driving the transfer of exosomal miR-125 from osteoarthritic chondrocytes, leading to the disruption of subchondral bone homeostasis and exacerbation of cartilage damage in aging mice. These findings shed light on the potential contribution of sympathetic regulation to the pathogenesis of aging-related OA.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study received ethical approval from the ethics committee of our hospital and the institutional review board (IRB) (DSYY-6420-032). All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines and adhered to the applicable regulations, such as the U.K. Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986 and associated guidelines, EU Directive 2010/63/EU for animal experiments, or the National Research Council’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants Nos. 82301242), Clinical Research Project of Shanghai Tenth People's Hospital (YNCR2C027), Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine (No: TRYJ2021JC02) and Tongren Xinxing (TRKYRC-xx202215), the Research Project of Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (20194Y0316), Outstanding Youth Fund Project of Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (2022YQ007) and Lvliang Key Research and Development Program (2023RC-2-6), Shanghai Natural Science Foundation(23ZR1449200).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Zhiyuan Guan: Conceptualization, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Yanbin Liu: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology. Liying Luo: Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision. Xiao Jin: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Validation. Zhiqiang Guan: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation. Jianjun Yang: Validation. Shengfu Liu: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation. Kun Tao: . Jianfeng Pan: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants and our hospital.

References

- 1.Englund M. Osteoarthritis, part of life or a curable disease? A bird's-eye view. J Intern Med. 2023;293(6):681–693. doi: 10.1111/joim.13634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foster N.E., Eriksson L., Deveza L., Hall M. Osteoarthritis year in review 2022: Epidemiology & therapy. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2023;31(7):876–883. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2023.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iijima H., Gilmer G., Wang K., Bean A.C., He Y., Lin H., et al. Age-related matrix stiffening epigenetically regulates α-Klotho expression and compromises chondrocyte integrity. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):18. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-35359-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eccleston A. Cartilage regeneration for osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2023;22(2):96. doi: 10.1038/d41573-022-00215-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guan Z., Jin X., Guan Z., Liu S., Tao K., Luo L. The gut microbiota metabolite capsiate regulate SLC2A1 expression by targeting HIF-1α to inhibit knee osteoarthritis-induced ferroptosis. Aging Cell. 2023;22(6):e13807. doi: 10.1111/acel.13807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cruz C.J., Dewberry L.S., Otto K.J., Allen K.D. Neuromodulation as a potential disease-modifying therapy for osteoarthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2023;25(1):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11926-022-01094-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris J.L., Letson H.L., Gillman R., Hazratwala K., Wilkinson M., McEwen P., et al. The CNS theory of osteoarthritis: Opportunities beyond the joint. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;49(3):331–336. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2019.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grässel S., Muschter D. Peripheral nerve fibers and their neurotransmitters in osteoarthritis pathology. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(5) doi: 10.3390/ijms18050931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pongratz G., Straub R.H. The sympathetic nervous response in inflammation. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16(6):504. doi: 10.1186/s13075-014-0504-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan J.Y.H., Chan S.H.H. Differential impacts of brain stem oxidative stress and nitrosative stress on sympathetic vasomotor tone. Pharmacol Ther. 2019;201:120–136. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Julien C., Zhang Z.Q., Barrès C. How sympathetic tone maintains or alters arterial pressure. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 1995;9(4):343–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.1995.tb00508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lorton D., Bellinger D.L. Molecular mechanisms underlying β-adrenergic receptor-mediated cross-talk between sympathetic neurons and immune cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(3):5635–5665. doi: 10.3390/ijms16035635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eitner A., Pester J., Nietzsche S., Hofmann G.O., Schaible H.G. The innervation of synovium of human osteoarthritic joints in comparison with normal rat and sheep synovium. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2013;21(9):1383–1391. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takeda S., Elefteriou F., Levasseur R., Liu X., Zhao L., Parker K.L., et al. Leptin regulates bone formation via the sympathetic nervous system. Cell. 2002;111(3):305–317. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guan Z., Yuan W., Jia J., Zhang C., Zhu J., Huang J., et al. Bone mass loss in chronic heart failure is associated with sympathetic nerve activation. Bone. 2023;166 doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2022.116596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clements J.D., Jamali F. Norepinephrine transporter is involved in down-regulation of beta1-adrenergic receptors caused by adjuvant arthritis. J Pharm Pharma Sci : Publication Can Soc Pharma Sci Soc Can Sci Pharma. 2009;12(3):337–345. doi: 10.18433/j3d012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abramoff B., Caldera F.E. Osteoarthritis: Pathology, diagnosis, and treatment options. Med Clin North Am. 2020;104(2):293–311. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2019.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martel-Pelletier J., Barr A.J., Cicuttini F.M., Conaghan P.G., Cooper C., Goldring M.B., et al. Osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16072. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu J., Wu X., Lu J., Huang G., Dang L., Zhang H., et al. Exosomal transfer of osteoclast-derived miRNAs to chondrocytes contributes to osteoarthritis progression. Nature aging. 2021;1(4):368–384. doi: 10.1038/s43587-021-00050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Théry C., Zitvogel L., Amigorena S. Exosomes: Composition, biogenesis and function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2(8):569–579. doi: 10.1038/nri855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathieu M., Martin-Jaular L., Lavieu G., Théry C. Specificities of secretion and uptake of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles for cell-to-cell communication. Nat Cell Biol. 2019;21(1):9–17. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0250-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karsdal M.A., Bay-Jensen A.C., Lories R.J., Abramson S., Spector T., Pastoureau P., et al. The coupling of bone and cartilage turnover in osteoarthritis: opportunities for bone antiresorptives and anabolics as potential treatments? Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(2):336–348. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grootaert M.O.J., Finigan A., Figg N.L., Uryga A.K., Bennett M.R. SIRT6 protects smooth muscle cells from senescence and reduces atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2021;128(4):474–491. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.120.318353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang Q., Gao Y., Liu Q., Yang X., Wu T., Huang C., et al. Sirt6 in pro-opiomelanocortin neurons controls energy metabolism by modulating leptin signaling. Mol Metab. 2020;37 doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2020.100994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang Q., Liu Q., Yang X., Wu T., Huang C., Zhang J., et al. Sirtuin 6 supra-physiological overexpression in hypothalamic pro-opiomelanocortin neurons promotes obesity via the hypothalamus-adipose axis. FASEB J. 2021;35(3):e21408. doi: 10.1096/fj.202002607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu C.H., Sui B.D., Liu J., Dang L., Chen J., Zheng C.X., et al. Sympathetic neurostress drives osteoblastic exosomal MiR-21 transfer to disrupt bone homeostasis and promote osteopenia. Small Methods. 2022;6(3):e2100763. doi: 10.1002/smtd.202100763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collins J.A., Kim C.J., Coleman A., Little A., Perez M.M., Clarke E.J., et al. Cartilage-specific Sirt6 deficiency represses IGF-1 and enhances osteoarthritis severity in mice. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82(11):1464–1473. doi: 10.1136/ard-2023-224385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loeser R.F., Collins J.A., Diekman B.O. Ageing and the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12(7):412–420. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2016.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rahmati M., Nalesso G., Mobasheri A., Mozafari M. Aging and osteoarthritis: Central role of the extracellular matrix. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;40:20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ter Heegde F., Luiz A.P., Santana-Varela S., Chessell I.P., Welsh F., Wood J.N., et al. Noninvasive mechanical joint loading as an alternative model for osteoarthritic pain. Arthritis Rheumatol (Hoboken, NJ) 2019;71(7):1078–1088. doi: 10.1002/art.40835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glasson S.S., Blanchet T.J., Morris E.A. The surgical destabilization of the medial meniscus (DMM) model of osteoarthritis in the 129/SvEv mouse. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2007;15(9):1061–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poulet B., Hamilton R.W., Shefelbine S., Pitsillides A.A. Characterizing a novel and adjustable noninvasive murine joint loading model. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(1):137–147. doi: 10.1002/art.27765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guan Z, Jia J, Zhang C, Sun T, Zhang W, Yuan W, et al. Gut microbiome dysbiosis alleviates the progression of osteoarthritis in mice. Clinical science (London, England : 1979). 2020;134(23):3159-74. doi: 10.1042/cs20201224. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Jeon O.H., Kim C., Laberge R.-M., Demaria M., Rathod S., Vasserot A.P., et al. Local clearance of senescent cells attenuates the development of post-traumatic osteoarthritis and creates a pro-regenerative environment. Nat Med. 2017;23(6):775–781. doi: 10.1038/nm.4324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glasson S.S., Chambers M.G., Van Den Berg W.B., Little C.B. The OARSI histopathology initiative - recommendations for histological assessments of osteoarthritis in the mouse. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2010;18(Suppl 3):S17–S23. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruan M.Z., Patel R.M., Dawson B.C., Jiang M.M., Lee B.H. Pain, motor and gait assessment of murine osteoarthritis in a cruciate ligament transection model. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2013;21(9):1355–1364. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2013.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deng C.L., Hu C.B., Ling S.T., Zhao N., Bao L.H., Zhou F., et al. Photoreceptor protection by mesenchymal stem cell transplantation identifies exosomal MiR-21 as a therapeutic for retinal degeneration. Cell Death Differ. 2021;28(3):1041–1061. doi: 10.1038/s41418-020-00636-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng C., Sui B., Zhang X., Hu J., Chen J., Liu J., et al. Apoptotic vesicles restore liver macrophage homeostasis to counteract type 2 diabetes. J Extracell Vesic. 2021;10(7):e12109. doi: 10.1002/jev2.12109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chalmin F., Ladoire S., Mignot G., Vincent J., Bruchard M., Remy-Martin J.P., et al. Membrane-associated Hsp72 from tumor-derived exosomes mediates STAT3-dependent immunosuppressive function of mouse and human myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(2):457–471. doi: 10.1172/jci40483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu D., Kou X., Chen C., Liu S., Liu Y., Yu W., et al. Circulating apoptotic bodies maintain mesenchymal stem cell homeostasis and ameliorate osteopenia via transferring multiple cellular factors. Cell Res. 2018;28(9):918–933. doi: 10.1038/s41422-018-0070-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shen W., Chen S., Xiang Y., Yao Z., Chen Z., Wu X., et al. Astroglial adrenoreceptors modulate synaptic transmission and contextual fear memory formation in dentate gyrus. Neurochem Int. 2021;143 doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2020.104942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang Y., Lin Y., Wang M., Yuan K., Wang Q., Mu P., et al. Targeting ferroptosis suppresses osteocyte glucolipotoxicity and alleviates diabetic osteoporosis. Bone Res. 2022;10(1):26. doi: 10.1038/s41413-022-00198-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barnett R. Osteoarthritis. Lancet (London, England) 2018;391(10134):1985. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bijlsma J.W., Berenbaum F., Lafeber F.P. Osteoarthritis: an update with relevance for clinical practice. Lancet (London, England) 2011;377(9783):2115–2126. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60243-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Balasubramanian P., Hall D., Subramanian M. Sympathetic nervous system as a target for aging and obesity-related cardiovascular diseases. GeroScience. 2019;41(1):13–24. doi: 10.1007/s11357-018-0048-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hart E.C., Charkoudian N. Sympathetic neural regulation of blood pressure: Influences of sex and aging. Physiology (Bethesda) 2014;29(1):8–15. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00031.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Z.M., Rodrigues A.C.Z., Messi M.L., Delbono O. Aging blunts sympathetic neuron regulation of motoneurons synaptic vesicle release mediated by β1- and α2B-adrenergic receptors in geriatric mice. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75(8):1473–1480. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glaa022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Delbono O., Rodrigues A.C.Z., Bonilla H.J., Messi M.L. The emerging role of the sympathetic nervous system in skeletal muscle motor innervation and sarcopenia. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;67 doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2021.101305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu G., Chen H., Liu H., Zhang W., Zhou J. Emerging roles of SIRT6 in human diseases and its modulators. Med Res Rev. 2021;41(2):1089–1137. doi: 10.1002/med.21753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Song M.Y., Han C.Y., Moon Y.J., Lee J.H., Bae E.J., Park B.H. Sirt6 reprograms myofibers to oxidative type through CREB-dependent Sox6 suppression. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):1808. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29472-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]