Graphical abstract

Keywords: Hexose, Immune cell, Metabolism, Inflammation, Cancer

Highlights

-

•

Hexoses present in high abundance in daily diets, their uptake and metabolism are closely associated with human health and diseases.

-

•

The crucial impacts of hexoses in regulating immune cell functions have attracted increasing attention over the past few years.

-

•

Targeting hexose metabolism is beneficial for rectifying immune dysregulation in various diseases.

-

•

The in-depth understanding of the impacts of hexoses on immune system can provide instructions to the food industry to develop dietary recipes for patients with immunological diseases.

-

•

We addressed the recent research updates on the immunoregulatory functions of hexoses, in order to provide new insights into the development of hexose-based immunotherapy strategies.

Abstract

Background

It is widely acknowledged that dietary habits have profound impacts on human health and diseases. As the most important sweeteners and energy sources in human diets, hexoses take part in a broad range of physiopathological processes. In recent years, emerging evidence has uncovered the crucial roles of hexoses, such as glucose, fructose, mannose, and galactose, in controlling the differentiation or function of immune cells.

Aim of Review

Herein, we reviewed the latest research progresses in the hexose-mediated modulation of immune responses, provided in-depth analyses of the underlying mechanisms, and discussed the unresolved issues in this field.

Key Scientific Concepts of Review

Owing to their immunoregulatory effects, hexoses affect the onset and progression of various types of immune disorders, including inflammatory diseases, autoimmune diseases, and tumor immune evasion. Thus, targeting hexose metabolism is becoming a promising strategy for reversing immune abnormalities in diseases.

Introduction

Hexoses, which are present in high abundance in the human body, are a class of simple sugars containing six carbon atoms with the chemical formula C6H12O6. The common natural hexoses comprise glucose, fructose, mannose, and galactose. There are also synthetic hexoses that serve as alternative sweeteners in the food industry. Hexoses and their metabolic intermediates are pivotal for maintaining the fundamental functions of cells. They serve as energy sources, participate in protein glycosylation and modification, and regulate intracellular signaling transduction. The close association between hexose consumption and human health has been acknowledged for decades. In recent years, the immunoregulatory functions of hexoses in various kinds of diseases have attracted increasing attention. A deeper understanding of the disease-related roles of hexoses is of great medical significance, primarily due to the following reasons: [1] hexoses exist in high abundance in both natural and processed foods. Additionally, in the human body, they are present in high concentrations in the blood and tissue microenvironments. [2] It will provide novel insights to the food industry for designing personalized food for individuals with various immune diseases, or offering dietary instructions for patients. [3] For therapeutic purposes, hexose “drugs” have advantages due to their relatively low cost, high safety, and ideal bioavailability. These features are crucial for achieving a good patient compliance. [4] For researchers, it will expand current knowledge on the cell metabolism-mediated regulation of immune responses. Thus, study on hexoses is an indispensable part of the immunometabolic atlas.

Compared with its crucial clinical and theoretical significance, the current knowledge on immunoregulatory hexoses lags behind. Although a large body of studies has linked hexose consumption to fat or other metabolic diseases, its potential impacts on human immunological parameters still lacks comprehensive epidemiological evidence. In addition, although emerging studies have been conducted on macrophages or T cells, the effects of hexoses on dendritic cells, mast cells, innate lymphoid cells, or specific tissue-resident immune cells are still largely overlooked. Apart from serving as cell nutrients and signaling modulators, hexoses or their metabolites are fundamental building blocks for various protein modifications, such as glycosylation, lactylation, and succinylation [1], [2], [3]. The mechanisms by which hexoses regulate immune responses through altering protein modification omics are not well understood.

In this review, we will discuss recent research updates regarding the immunoregulatory functions and mechanisms of hexoses, and propose future directions in this area.

Glucose

D-Glucose (since L-hexoses are rare sugars with extremely low abundance in nature, all hexose names mentioned in this review denote D-hexoses unless otherwise stated) serves as the most crucial carbohydrate fuel in the human body. Upon being ingested by the body, glucose enters energy-requiring organs through blood circulation, and can be transported into cells via glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) and GLUT3 [4]. The intracellular glucose is catabolized through three major pathways: glycolysis pathway, tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, and pentose phosphate pathway (PPP). Glycolysis is a process in which intracellular glucose is broken down to produce pyruvate and ATP through a series of enzymatic reactions. When oxygen is sufficient, pyruvate is converted into acetyl-CoA which is then transported to mitochondria for TCA cycle. In contrast, under anaerobic conditions, pyruvate is broken down to lactate by lactate dehydrogenase (LDHA). However, proinflammatory immune cells preferentially convert pyruvate to lactate even in an oxygen-sufficient microenvironment, called aerobic glycolysis (also known as Warburg effect). PPP pathway begins with glucose 6-phosphate (G-6-P) and finally generates nucleotides and NADPH, leading to the enhanced respiratory burst and antibacterial capacity of immune cells [5], [6].

The impacts of glucose on human health and disease have been extensively summarized in previous reviews. Herein, we primarily focus on recent progresses in glucose-mediated immunomodulation. In many disease microenvironments, immune cells exhibit altered expression of glucose metabolism-related enzymes or transporters. In general, pro-inflammatory immune cells (such as classically activated macrophages, dendritic cells, and effector T cells) express high levels of glucose transporter GLUT1 and GLUT3, as well as glycolytic enzymes such as hexokinase2 (HK2), phosphofructokinase1 (PFK1), 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3), and LDHA [4], [7], [8], [9], [10]. The consequent enhancement of glucose uptake and metabolism is essential for the rapid generation of various metabolic intermediates that support the inflammatory activation of these cells. In contrast, immunosuppressive cells, such as regulatory T cells (Tregs), exhibited decreased expression of GLUT1, GLUT3 and HK2 during their differentiation [11], [12]. Therefore, different types of immune cells adopt distinct strategies of glucose metabolism to support their specific functions (see below).

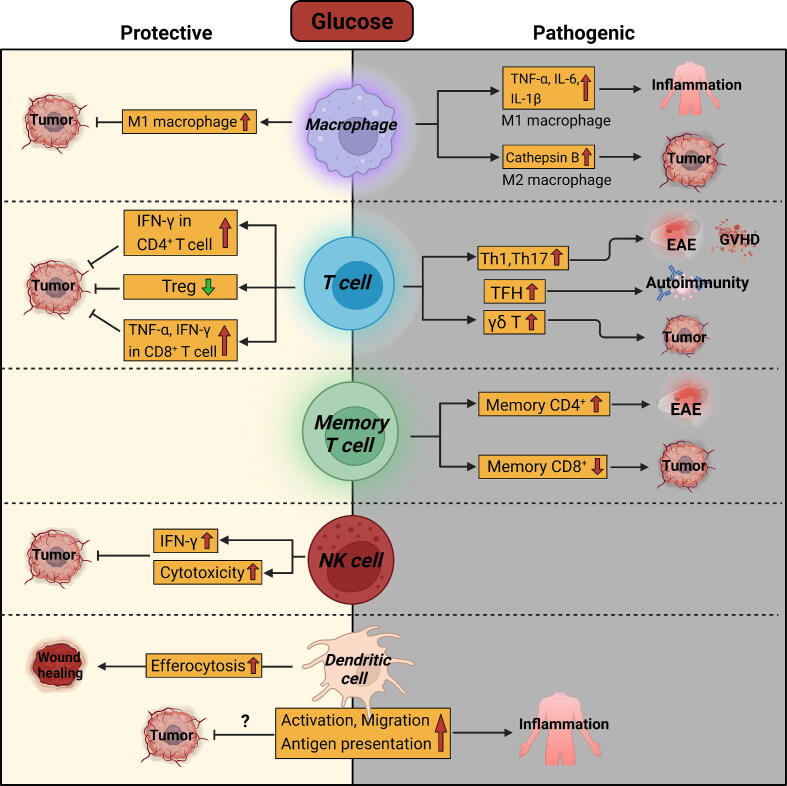

The Effects of Glucose on Innate Immune Cells

Macrophages are the most abundant innate immune cells in many tissues, where they have profound and multifaceted impacts on tissue immune homeostasis. In a simplified manner, macrophages can be divided into classically activated macrophages (M1 macrophages) and alternatively activated macrophages (M2 macrophages) depending on their functional status. M1 macrophages typically secrete high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which exacerbate tissue inflammation but also facilitate anti-tumor immunity. In contrast, M2 macrophages primarily mediate an anti-inflammatory response and accelerate tissue repair, while typically inducing immune suppression in tumor microenvironment [13]. M1 and M2 macrophages exhibit distinct metabolic characteristics. In general, M1 macrophages utilize glycolysis to stimulate the production of inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) [14]. High glucose promotes the expression of M1 macrophage marker genes, while inhibiting the expression of M2 macrophage marker genes, thereby accelerating inflammation and inflamm-aging [15], [16], [17]. Therefore, inhibiting glucose uptake or glycolysis is helpful for decreasing M1 macrophage-mediated inflammation, such as sepsis [18], colitis [19], rheumatoid arthritis [20], silicosis [21], and ankylosing spondylitis [22]. In addition, inhibiting glycolysis is also protective in diabetic cardiomyopathy [23] and acute liver failure [24] by reducing the inflammatory activation of macrophages. In contrast to inflammatory diseases, where M1 macrophages typically play a pathogenic role, the enhanced reprogramming of M1 macrophages is well-accepted as necessary for inducing antitumor immunity. Therefore, it is plausible that maintaining a high glycolytic phenotype could promote the antitumor capacity of macrophages. Indeed, it has been reported that compared with tumor cells and other tumor-infiltrating immune cells, myeloid cells have the highest ability to uptake intra-tumoral glucose [25]. High glycolytic activity in tumor tissues was associated with increased M1 macrophage signatures [26], [27]. Boosting glycolysis in tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) reprogrammed them into an anti-tumor phenotype [28], [29].

Compared with M1 macrophages, the impact of glycolysis on M2 macrophages remains controversial to date. It is reported that glycolysis is dispensable for M2 macrophage differentiation as long as oxidative phosphorylation is intact [30]. In contrast, another study found that glycolysis drove the differentiation of M2 macrophages [31]. Surprisingly, although high glycolytic activity is a metabolic feature of M1 macrophages, it also facilitates the functions of TAMs which typically resemble M2 macrophages. Inhibition of glycolysis reduced the expression of M2 markers, including mannose receptor 1 (MRC1/CD206), C-type lectin domain containing 10A (CLEC10A/CD301), and CD163 without affecting the level of M1 macrophage marker cluster of differentiation 86 (CD86) Md-B et al., 2020;1867 [32]. TAMs expressed higher levels of glucose transporter GLUT1 than M1-like TAMs, and thus had a stronger glucose uptake ability than M1-like macrophages. Glucose uptake in M2-like TAMs facilitated the O-GlcNAcylation of Cathepsin B to promote its maturation and secretion from macrophages. High levels of Cathepsin B in tumor microenvironment ultimately promoted tumor metastasis and chemoresistance [33]. Thus, the enhancement of glycolysis appears to both promote and repress the anti-tumor properties of TAMs. The inconsistency among previous studies may be attributed to the extreme plasticity and heterogeneity of tissue macrophages. As mentioned above, the M1-M2 dichotomy is an oversimplified classification system based on the in vitro stimuli they receive, specifically lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or interferon-γ (IFN-γ) for M1, and interleukin-4 (IL-4) or IL-13 for M2). Nevertheless, in the actual tissue microenvironment, macrophages display mixed phenotypes with both M1 and M2 features. Indeed, TAMs exhibited both high glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation Md-B et al., 2020;1867 [32] In recent years, the development of single-cell technologies has revealed the heterogeneity of TAMs with distinct metabolic features. Therefore, the pathological significance of glucose on tissue macrophages is far more complicated than in vitro system, and depends on the definition of different macrophage subsets, their differentiation status, and the specific disease microenvironment.

Glucose also has complex impacts on dendritic cells (DCs) – another key component of the innate immune system. It was reported that glucose-driven glycolysis resulted in increased efferocytosis of DCs, which expedited wound healing in diabetic mice by clearing apoptotic cells [34]. As the most potent antigen-presenting cell (APC), DCs play pivotal roles in connecting innate and adaptive immunity, a process that is influenced by glucose. Numerous previous studies have indicated that glycolytic activity is required for the maturation, cytokine production, migration, and antigen presentation capacity of DCs [10], [35], [36], [37], [38]. Thus, glycolytic activity in DCs enhances their proinflammatory activities, while it may also facilitate anti-tumor immunity by promoting antigen recognition by T cells. Confusingly, a conflicting report showed that glucose suppressed the expression of CD80 and CD86 in DCs. CD8+ T cells co-cultured with high glucose-exposed DCs exhibited impaired proliferation and production of IFN-γ [39]. Therefore, the exact impacts of glucose on DCs in tumor microenvironment still require further investigation.

The Effects of Glucose on T Cells

In terms of the impact of glucose on adaptive immunity, effector CD4+ T helper (Th) cell subsets, including Th1, Th2, Th17 cells, rely on glucose for their proliferation and effector cytokine production [40], [41], [42]. In tumor microenvironment, malignant cells can consume large amounts of glucose, imposing a glucose restriction on CD4+ T cells, which dampens IFN-γ production and may compromise anti-tumor immunity [43]. Similar to effector CD4+ T cells, inhibiting glucose uptake decreased the survival of autoreactive memory CD4+ T cells, thereby suppressing the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) [44]. Contrarily, Tregs rely on oxidative phosphorylation for differentiation and survival [11], [45]. High glucose uptake disrupts the stability and function of Tregs, making them less immunosuppressive in tumor tissues [46]. In effector CD8+ T cells, promoting glucose uptake through GLUT3 overexpression enhanced their tumoricidal function, as evidenced by the upregulated production of TNF-α and IFN-γ, and increased cell proliferation [47]. In tumor microenvironment, the limited glucose availability diminished the cytotoxic capacity of T cells and natural killer (NK) cells, leading to tumor immune evasion [48], [49]. Therefore, creating a high-glucose tumor microenvironment by IFN-α promoted the differentiation of CD27+CD8+ T cells, which facilitated tumor eradication [50]. In addition, programmed death-1 (PD-1) ligation by programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) on T cells blocks their activation by shifting their metabolism from glycolysis to fatty acid β-oxidation (FAO) [51], implying that restoring glycolysis in T cells contributes to the therapeutic effect of anti-PD1 antibodies in cancer patients. Congruently, immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) using anti-PD-1, anti-PD-L1, and anti-cytotoxic lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) antibodies restored glycolytic activity in tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells and reinstated their cytotoxic capability. In sharp contrast, PD-L1 blockade reduced glycolytic activity in tumor cells [52]. Unlike effector CD8+ T cells, glucose impairs the generation and function of memory CD8+ T cells. The restricted glucose uptake facilitated the formation of memory CD8+ T cells and increased their antitumor function [53]. On the other hand, high glucose also reduces the antitumor function of γδ T cells via inhibiting the secretion of cytotoxic granules. Thus, γδ T cells from type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with high blood glucose levels had impaired tumoricidal capacity [54].

In contrast to the cancer milieu, the high glucose consumption in effector T cells promotes disease progression in inflammation and autoimmune disorders. For example, Il10−/− mice fed a high-glucose diet developed spontaneous colitis [55]. Additionally, the high expression of glucose transporter GLUT3 increased the pathogenicity of Th17 cells in EAE [56]. Similarly, high glucose intake aggravated autoimmunity by promoting TGF-β-mediated Th17 cell development [57]. In lupus mice, high glucose facilitated the development of autoreactive, pathogenic follicular helper T (Tfh) cells [58]. Consistent with the findings from preclinical models, high blood glucose levels are linked to more severe disease outcomes in patients with inflammation or autoimmune diseases [59], [60], [61].

Summary

Taken together, limiting dietary glucose consumption is helpful for rectifying the immune abnormalities in many pathological processes (Fig. 1). Although glycolytic activity in macrophages and effector T cells is sometimes required for their anti-tumor function, high blood glucose levels have been observed to be associated with an increased risk of cancer [62], [63], [64], [65]. Therefore, reducing glucose intake might still be required for effective cancer treatment, considering the overall impact of glucose on the entire tumor microenvironment, especially on tumor cells that are highly dependent on glucose to support their malignant behavior.

Fig. 1.

Immunoregulatory effects of glucose.

Fructose

Fructose, a ketose form of glucose, exists in high concentrations in natural fruits, vegetables, and honey. Fructose is sweeter than glucose in equal quantities. Hence, many processed foods, soft drinks, and fruit juices contain fructose as a sweetener, primarily in the form of high fructose corn syrup (HFCS) [66]. In recent decades, global fructose consumption has sharply increased, raising numerous health concerns including obesity, cardiovascular disease, asthma, diabetes, and even cancer [67]. Fructose metabolism primarily occurs in the liver, where it is passively transported into cells through GLUT5. After entering cells, fructose can be catabolized to lactate, converted into glucose and glycogen, or participate in lipogenesis [68]. The excessive, unmetabolized intracellular fructose is transported out of the cells and enters the bloodstream via GLUT2 [69].

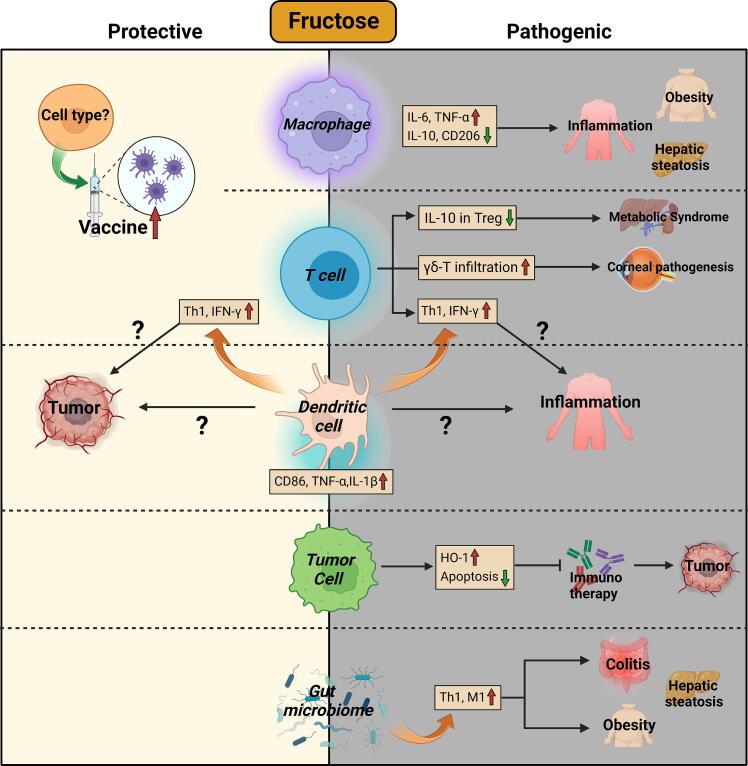

The Effects of Fructose on Inflammatory Diseases

Recent evidence has revealed that high fructose consumption is closely associated with immune dysregulation [70]. Fructose promotes the production of inflammatory cytokines by DCs. Moreover, fructose-primed DCs further upregulated the production of IFN-γ by T cells [71]. This effect may potentially amplify Th1 cell-mediated inflammation, while also promoting the establishment of a Th1-dominant anti-tumor microenvironment. A high-fructose diet (HFD) induced metabolic syndrome in rats, which was associated with impaired IL-10 production by Tregs [72]. The high fructose-induced metabolic abnormality was also evidenced by the fact that fructose stimulated hepatosteatosis via inducing TNF-α production by macrophages [73]. In LPS-induced systemic inflammation, fructose upregulated the production of inflammatory cytokines in macrophages by promoting glutaminolysis and oxidative metabolism [74]. HFD increased the expression of M1 macrophage markers (IL-6, TNF-α), while reducing the expression of M2 macrophage markers (MRC1, IL-10) in adipose tissues. As a result, HFD induced low-grade chronic inflammation and promoted the development of obesity [75]. Through promoting TLR4 signaling, fructose induces the activation of microglia in neuroinflammation [76]. The pro-inflammatory effect of fructose was also observed in intestinal inflammation [77]. In a murine ovariectomized model, the isocaloric high-fructose diet suppressed obesity caused by estrogen deficiency. However, side effects on immune responses were observed, such as increased percentages of T cells in the spleen, and elevated production of IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-17 by splenocytes [78]. In contrast, Lodge et al. reported that chronic fructose intake induced the expression of a panel of anti-inflammatory genes in Kupffer cells through modulating the PPP pathway [79]. Interestingly, fructose also plays a role in eye health. HFD significantly increased the infiltration of γδ-T cells and neutrophils in the cornea, which was associated with impaired corneal sensitivity [80].

Apart from fructose itself, its downstream metabolites such as uric acid (UA) and fatty acids (FAs), also act as immunomodulators. UA treatment increased the expression of TNF-α and Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4, while repressing MRC1 expression in macrophages [81]. Similarly, FAs also have pro-inflammatory effects through activating TLR4 signaling in macrophages [82].

The Effects of Fructose on Gut Microbiota

Recent studies have also discovered that fructose has profound impacts on gut microbiome. For instance, HFD disrupted the composition of gut microbiota and induced chronic inflammation-associated obesity [83]. Under restraint stress conditions, HFD remarkably altered taxonomic composition of colon microbiota, leading to a decrease in taurine levels and an increase in histamine levels. These changes in colonic metabolites impaired epithelial barrier integrity and aggravated restraint stress-induced intestinal inflammation [84]. In a dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) colitis model, high fructose intake altered the β-diversity of gut microbiota, and accelerated the progression of inflammation [55]. Similarly, HFD resulted in a reduced Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes ratio in the gut, increased Th1 inflammation, and compromised intestinal epithelium, facilitating the entry of endotoxins into the liver. Hence, the HFD mice exhibited greater hepatic infiltration of inflammatory T cells and macrophages, which contributed to the progression of hepatic steatosis [85]. Apart from its inter-organ effect, the detrimental effect of fructose can even be transmitted to offsprings, as evidenced by the finding that maternal HFD challenge activated T cells and increased the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the offsprings [86]. It is plausible to hypothesize that the inheritable impact of fructose is at least partially mediated through microbiota transmission from mother to offspring.

The Effects of Fructose on Tumor Immunity

Since the aforementioned studies indicate that fructose is typically associated with immune activation, we may speculate that fructose could potentially enhance antitumor immunity. However, this does not appear to be the case. Although the direct effects of fructose on the functions of tumor-infiltrating immune cells remain poorly understood, a body of evidence has linked excessive fructose intake with an increased risk of cancer [87], [88], [89]. Cancer patients have elevated serum fructose levels compared to healthy subjects [90], [91]. HFD increased the production of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), which protected tumor cells from immune-mediated eradication. Reducing dietary fructose content overcame resistance to cancer immunotherapy [92]. In addition, dietary fructose can be converted into lactate, which promotes the differentiation of protumoral M2-like TAMs [93], [94]. To date, the impacts of fructose on various subtypes of macrophages or T cells in tumor microenvironment still require in-depth investigation.

Interestingly, although fructose did not affect the proliferation or viability of normal immune cells, it supported the growth of leukemic cells. Jeong et al. reported that fructose-treated acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells proliferated faster than those treated with equal amount of glucose. In tumor cells that expressed high levels of fructose transporter GLUT, fructose was metabolized through serine synthesis pathway to facilitate their proliferation [95].

Summary

Given that fructose generally causes undesirable immune responses in various preclinical disease models (Fig. 2), it does not necessarily mean that we should consume less fruit. Because the amount of fructose in natural foods appears unlikely to cause obesity or other adverse effects, as long as excessive food additive fructose is avoided [96]. In certain cases, fructose can have beneficial effects on the immune responses. For example, Wang et al. reported that fructose supplementation enhanced the immune-protective effect of live vaccines [97]. Additionally, natural fruits and vegetables contain a variety of substances that are beneficial for the human immune system, including vitamins, amino acids, and other beneficial sugars such as mannose (see below).

Fig. 2.

Immunoregulatory effects of fructose.

Mannose

Mannose is the C2 epimer o glucose. Foods that contain high levels of mannose include berries, oranges, apples, beans, and eggplants. At present, mannose has been widely utilized to treat urinary tract infection since it can prevent bacteria from adhering to the urinary tract [98]. Mannose is not a preferred energy source for the human body. Therefore, unlike glucose and fructose, high mannose consumption does not lead to obesity. Contrarily, mannose supplementation prevented high-fat diet-induced obesity in mice by correcting the gut microbiota [99]. In cells, mannose is an essential component of N-linked glycosylation (N-glycosylation), a post-translational modification that is indispensable for the functions of many proteins [100]. Mannose receptor MRC1 is highly expressed on monocytes, macrophages, and DCs [101]. MRC1 recognizes terminal mannose, fucose, or N-acetylglucosamine residues presented on the surface of various microorganisms, then initiates cell activation to produce appropriate immune responses [101].

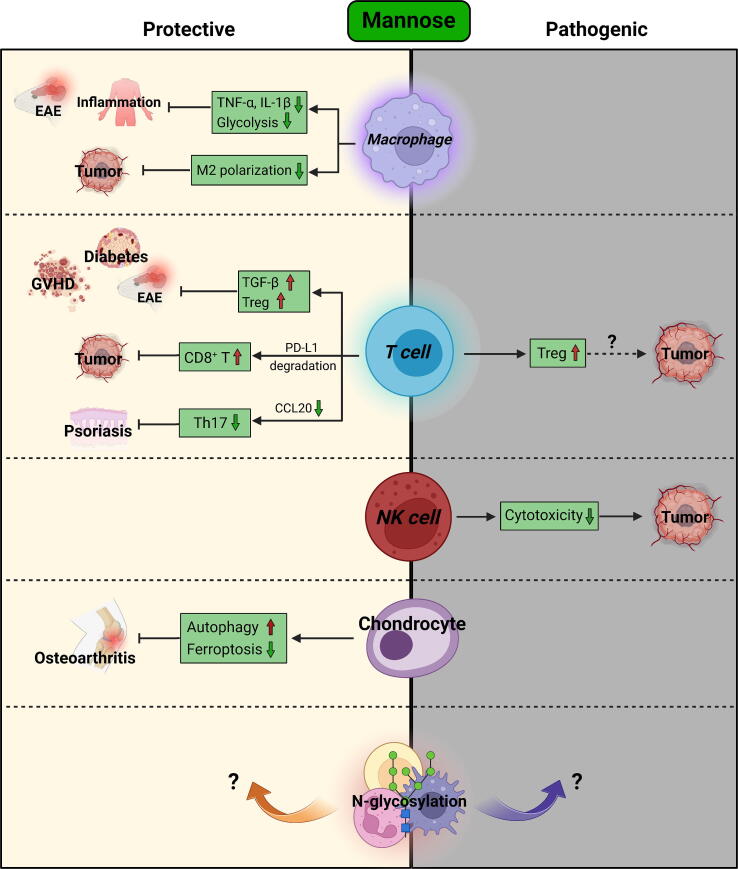

The Effects of Mannose on Macrophages

Although mannose has already been marketed as a dietary supplement for many years [98], its immunoregulatory roles have long been neglected. In contrast to glucose and fructose, which typically result in undesired immune responses, emerging evidence has uncovered the beneficial role of mannose in reversing immune imbalance in recent years. Since MRC1 is a hallmark of anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages, earlier studies have reported that mannose inhibited LPS-induced production of inflammatory cytokines in macrophages in an MRC1-dependent manner, and thus alleviated acute lung injury [102], [103]. Additionally, mannose inhibited the phagocytosis of macrophages and decreased their inflammatory activation, thereby playing a protective role in EAE [104]. In a colitis-associated colorectal model, mannose inhibited the polarization of M2-like TAMs by reducing glycolysis-generated lactate in tumor cells, leading to the impaired tumor progression [105].

Since the inflammatory activation of macrophages relies on glycolysis, Simone et al. reported that mannose suppressed hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) signaling in macrophages by reducing intracellular levels of succinate derived from glucose metabolism. In this way, mannose inhibited IL-1β expression in macrophages and protected mice from endotoxemia [106]. Xiao et al. revealed that mannose supplementation ameliorated intestinal inflammation by reducing glycolysis-dependent production of TNF-α in macrophages [107]. Contrary to earlier reports, the anti-inflammatory function of mannose in Xiao et al.’s and Simone et al.’s work is independent of MRC1. As different types of macrophages were used in these studies (RAW264.7 macrophage cell line versus primary macrophages), it is possible that the inconsistency resulted from varying experimental conditions. Intriguingly, elevated serum or plasma mannose concentrations were observed in colitis patients compared to healthy individuals [107], [108]. This may be attributed to the reduced mannose absorption or impaired mannose metabolism in the context of inflammation. Although mannose was reported to alter the composition of gut microbiome, its anti-colitic effect appears to be independent of its impacts on microbiota in a DSS-induced colitis model [107]. However, in a Trichinella spiralis infection colitis model, mannose administration reduced worm burdens in the intestine and prevented inflammation [109]. Thus, the effects of mannose on specific bacteria species still need further investigation.

The Effects of Mannose on T Cells

Growing evidence has revealed the multifaceted impacts of mannose on T cell function. Mannose induces the differentiation of Tregs via turning latent TGF-β into its activation form. The mannose-mediated Treg expansion alleviated type 1 diabetes [110], ovalbumin-induced airway inflammation [110], EAE [111], and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) [112]. In contrast to Tregs, mannose inhibited the polarization of Th1 and Th2 cells, without affecting Th17 cell polarization [110]. However, in a psoriasis model, mannose reduced the infiltration of pathogenic Th17 cells via inhibiting the production of a Th17 chemokine – C–C motif chemokine ligand 20 (CCL20) by keratinocytes [113].

Intriguingly, under glucose-restricted condition, mannose supported the polarization of Th1 cells [114]. This finding provides new insights into the potential role of mannose in anti-tumor immunity. Due to the competition for glucose between tumor cells and T cells, the availability of glucose in tumor-infiltrating T cells is usually restricted [52]. In this scenario, mannose supplementation might be helpful for establishing a Th1-dominant antitumor microenvironment. Mannose also enhances the responsiveness of ICB therapy in cancer. A recent study revealed that mannose facilitated the degradation of PD-L1 protein, leading to the enhanced cytotoxicity of T cells against tumor cells. By this means, mannose significantly sensitized the therapeutic response of anti-PD-1 antibody in breast cancer [115].

The Effects of Mannose on the N-glycosylation of Immune Receptors

The immune-modulatory functions of mannose might be much broader than we realized. As mentioned above, mannose is the predominant monosaccharide component of N-glycosylation, a post-translational modification that occurs in approximately 90 % glycoproteins [116]. N-glycosylation either negatively or positively regulates the functions of many immune receptors, such as T-cell receptor (TCR) [117], [118], co-stimulatory molecule CD28 [119], natural killer cell receptor 2B4 [120], immune checkpoint molecule PD-1 [121], CTLA-4 [122], ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1 (ENTPD1/CD39) [123], and ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) [124]. In addition, N-glycosylation occurs in a broad spectrum of cytokine/chemokine receptors, affecting their ligand binding affinity, signal transduction, and stability [125], [126], [127]. In addition, the abnormal protein N-glycosylation causes endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS), which can be reversed by mannose [128], [129]. It is reported that in colitis, mannose reduced inflammation-induced ERS in intestinal epithelial cells by normalizing protein N-glycosylation, thus preserving epithelium integrity [107]. Surprisingly, in another study, mannose administration inhibited rather than increased the N-glycosylation of PD-L1. This unexpected effect results from the mannose-induced activation of adenosine 5‘-monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling, and the consequent phosphorylation of PD-L1 [115]. To date, the effects of mannose on the N-glycosylation of specific proteins in disease microenvironments, and its impacts on immune responses are still far beyond understanding.

Summary

In summary, unlike glucose and fructose, mannose appears to generally provide protection against various immune diseases (Fig. 3). Notably, compared to most synthetic drugs, mannose has advantages in terms of safety, price, oral availability, and palatability, thus having better patient compliance. To date, no obvious side effects have been observed in patients treated with mannose, except for mild diarrhea [130]. However, although mannose enhanced anti-tumor immunity in the aforementioned reports, a study in 1980 found that mannose inhibited the cytotoxicity of NK cells against tumor cells [131]. In addition, the potent Treg-inducing property of mannose may potentially contribute to an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in certain instances. Therefore, further efforts are required to gain a comprehensive understanding of how mannose influences anti-tumor immunity.

Fig. 3.

Immunoregulatory effects of mannose.

Galactose

Galactose is the C4 epimer of glucose primarily presented in dairy products such as milk, yogurt, and cheese. In addition to serving as an energy source, galactose is an essential precursor for glycosylation, which is crucial for numerous biological functions, including protein modification, the formation of extracellular matrix, intercellular communication, and intracellular signal transduction [132].

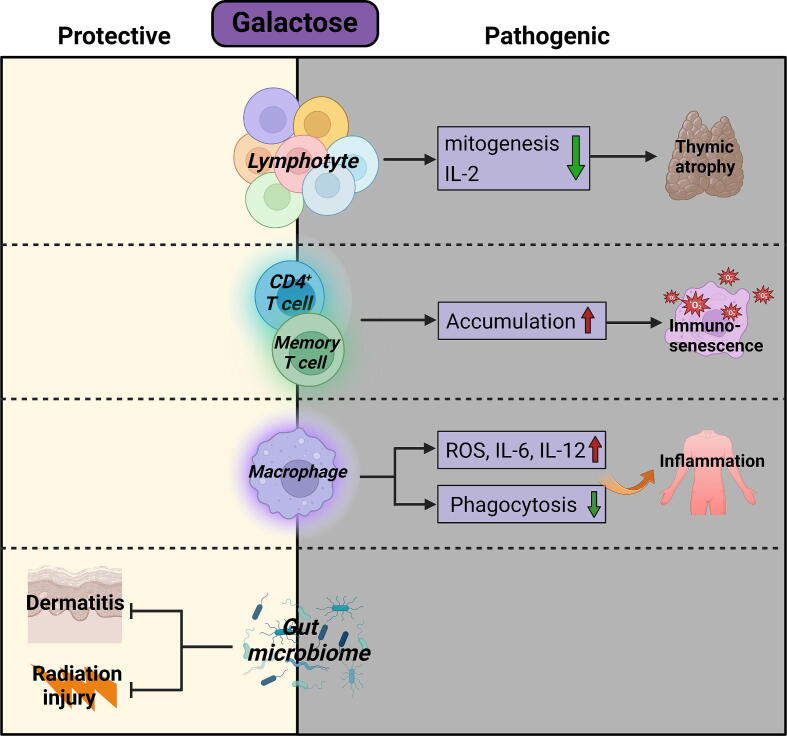

One of the most prominent properties of galactose is its ability to be oxidized into hydrogen peroxide by galactose oxidase, leading to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) which accelerates aging [133]. Galactose has multifaceted, typically harmful effects on the immune system. For example, galactose treatment promoted the senescence and M1 differentiation of macrophages [134]. Polymorphonuclear cells and macrophages exposed to galactose exhibited impaired phagocytic capacity against Escherichia coli [135]. Galactose administration led to chronic low-grade inflammation, prominent immunosenescence, and thymic atrophy [136], resembling natural aging in humans. Similarly, galactose impaired IL-2 production and mitogenesis of splenic lymphocytes [137]. In terms of its impact on T cell compartment, the percentages of CD62LlowCD44high memory T cells in the spleen were significantly increased by galactose. In addition, galactose promoted the accumulation of all major CD4+ T cell subsets, including Th1, Th2, Th17, Treg, and Tfh cells in the spleen [138]. In animal models, high galactose diet induced intestinal inflammation [139], neuroinflammation [140], cardiac inflammation [141], liver inflammation [142], [143], and senile osteoporosis [144]. Chronic inflammation is a major driving factor for tumorigenesis, and the ROS-generating property of galactose might dampen the functions of antitumor immune cells [145]. However, at least in ovarian cancer patients, there appears to be no correlation between galactose consumption and increased cancer risk [146], [147]. On the contrary, dietary fiber galactose was shown to be a protective factor in colorectal cancer patients [148]. In fact, the positive impact of galactose on immune responses has also been documented in other diseases. In an atopic dermatitis model, orally administered galactose prevented systemic inflammation, and decreased the levels of serum IgE in mice. Mechanistically, galactose restored the dysregulated gut microbiota composition in atopic dermatitis mice, as evidenced by the enhanced ratio of Bacteroidetes to Firmicutes [149]. Likewise, galactose improved the gut microbiome and thus alleviated ionizing radiation-induced injury [150]. Therefore, the precise impact of the physiological concentration of galactose on immune microenvironments needs further evaluation (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Immunoregulatory effects of galactose.

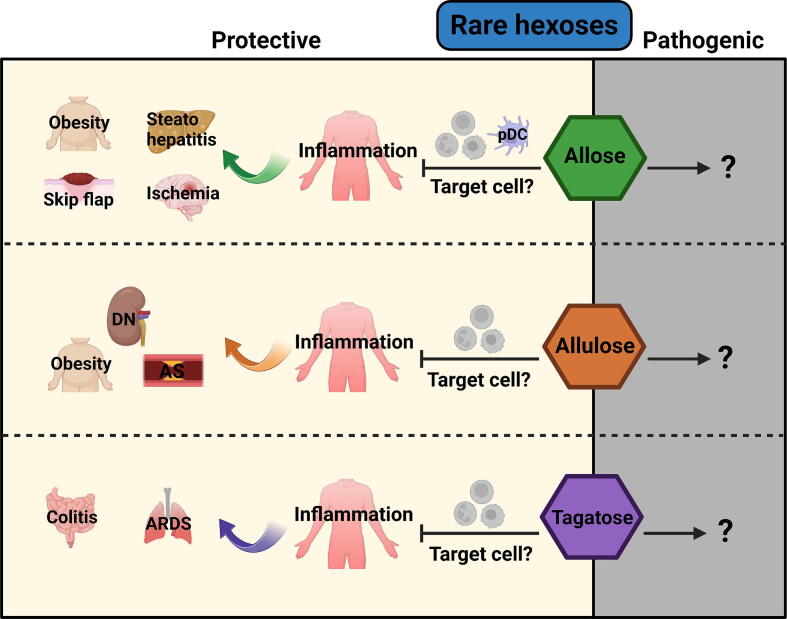

Rare hexoses

Rare hexoses are six-carbon sugars that rarely exist in nature. There are approximately 20 rare hexoses, including L-hexoses [151]. Due to their low availability and abundance, the biological functions of most rare sugars are far from being fully understood. However, several rare hexoses have been industrially synthesized as alternative sweeteners. Evidence from clinical trials has shown the beneficial effects of certain rare hexoses on blood glucose control and body metabolism regulation [152], with a few rare hexoses also being reported as immunoregulators, such as allose, allulose, and tagatose (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Immunoregulatory effects of rare hexoses.

Allose

A recent study found that allose, a C-3 epimer of glucose, suppressed the production of IFN-α and IL-12 in plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) [153]. Although in this study allose did not alter cytokine production in conventional DCs, another study reported that allose reduced endocytosis and CD40 expression in DCs. T cells co-cultured with allose-treated DCs displayed increased apoptosis [154]. Allose also suppressed neutrophil activation through reducing ROS production [155]. In skin flap and transient forebrain ischemia models, allose reduced the production of inflammatory cytokines and mitigated pathological changes [156], [157]. Similarly, dietary allose supplementation reduced hepatic inflammation in a murine non-alcoholic steatohepatitis model. In tumor models, several pieces of evidence indicate that allose inhibits the progression of lung cancer [158], head and neck cancer [159], and bladder cancer [160]. However, these reported antitumor effects were only observed in nude mice. Hence, the precise impact of allose on tumor immunity still awaits further evaluation using immunocompetent mice.

Allulose

Allulose, a C-3 epimer of fructose, is used as a sucrose alternative because of its extremely low calorie content. Emerging evidence has indicated the anti-oxidant, anti-obesity, and anti-inflammatory effects of allulose [161]. Allulose intervention markedly reduced the expression of inflammatory genes in obese mice, probably due to its impact on gut microbiota such as Lactobacillus and Coprococcus [162]. High fat diet-fed mice administered with allulose exhibited decreased hepatic and systemic inflammation [163]. Allulose suppressed the production of CCL2 (the major monocyte chemokine) from high glucose-challenged endothelial cells. This effect might prevent monocyte/macrophage-mediated inflammation in atherosclerosis (AS) [164]. In a rat diabetic nephropathy (DN) model, allulose administration mitigated disease symptoms and downregulated the levels of TNF-α and IL-6 in the kidney [165]. Surprisingly, in a clinical trial conducted on patients with type 2 diabetes, short-term allulose treatment failed to reduce TNF-α production. Furthermore, the production of CCL2 was upregulated in allulose-treated patients [166], suggesting that a more careful assessment of the clinical impact of allulose consumption on inflammation is needed.

Tagatose

Tagatose is a C-4 epimer of fructose that exists in certain natural foods, such as milk and oranges. It is industrially produced as a low-calorie sweetener. It is reported that tagatose effectively mitigated colitis in mice as a prebiotic [167]. The anti-inflammatory effect of tagatose was also observed in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [168]. In a rat myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury model, a tagatose-enriched diet reduced the plasma levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β compared to a fructose-enriched diet [169]. Currently, the direct effects of tagatose on various immune cell populations remain elusive.

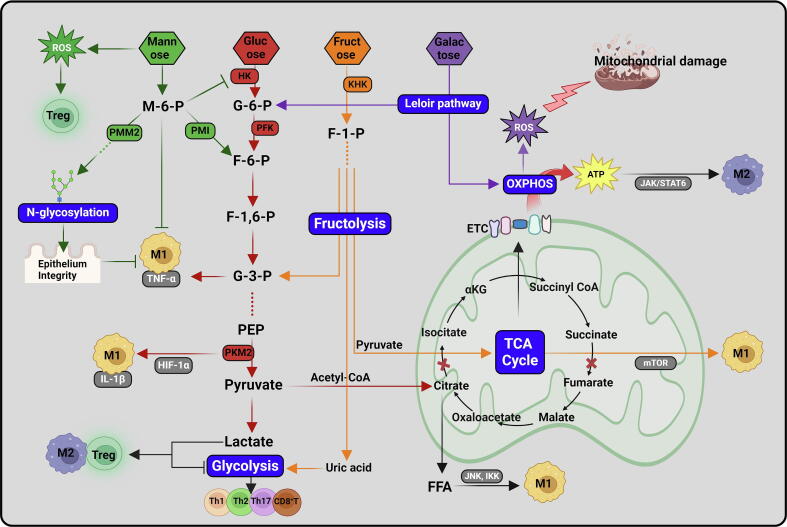

Molecular basis of the immunoregulatory functions of hexoses

Despite their structural similarity, the metabolic pathways of hexoses and the consequent impacts on cellular signaling transduction are distinct. The molecular regulatory mechanism of these pathways is one of the hottest areas in immunological research (Fig. 6). As the so-called “central metabolism”, glucose metabolism through glycolysis and TCA cycle is the fundamental biochemical activity in almost all living cells. Glycolysis always contributes to the inflammatory phenotypes of immune cells, such as M1 macrophages, Th1 cells, and CD8+ T cells [170]. Although the glycolytic metabolic pathway is relatively inefficient in producing adenosine triphosphate (ATP) for energy, it is crucial for synthesizing building blocks including amino acids, riboses, or lipids for environmental adaptation of immune cells. Upon activation by TLR ligands or antigen signals, resting macrophages or T cells exhibit enhanced glucose uptake to initiate aerobic glycolysis. The master transcription factors of M1 macrophages, such as nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) and signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1), and the master transcription factors of effector CD4+ T cells, namely T-bet/ GATA binding protein-3 (GATA-3) for Th1/Th2 subset, promote the expression of genes encoding glucose transporters and glycolytic enzymes [171], [172], [173], [174]. Reciprocally, glycolytic metabolism drives the differentiation of these cells. The three irreversible, rate-limiting steps of glycolysis are the conversion of glucose to G-6-P by HK, conversion of fructose 6-phosphate (F-6-P) to fructose 1,6-bisphosphate (F-1,6-BP) by PFK1, and conversion of phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) to pyruvate by pyruvate kinase isozyme type M2 (PKM2), respectively. Besides acting as a metabolic enzyme, PKM2 directly forms a complex with HIF-1α to activate the transcription of the IL-1β-encoding gene (Il1b) [175].

Fig. 6.

The regulation network of hexose metabolism.

Compared to the glycolytic pathway, the TCA cycle-coupled oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) pathway is more efficient in ATP production. M1 macrophages have a truncated TCA cycle downstream of citrate and succinate, leading to the excessive accumulation of these two metabolites within cells. Citrate was utilized for the synthesis of free fatty acids (FFAs), which promote the activation of inhibitor of kappa B kinase (IKK) and c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 (JNK1) signaling, resulting in the expression of inflammatory cytokines [176], [177]. On the other hand, succinate stabilizes HIF-1α, which directly induces the expression of IL-1β [178]. In sharp contrast to M1 macrophages, the differentiation of M2 macrophages through Janus kinase (JAK)/STAT6 signaling does not rely on glycolysis. M2 macrophages differentiated normally even in the glucose-deprived medium. As an ATP-dependent kinase, JAK activity is sufficient to phosphorylate STAT6 as long as the intracellular ATP concentration reaches a certain threshold. When the glycolytic pathway is blocked, ATP can be generated from the TCA cycle-coupled OXPHOS or glutamine metabolism, ensuring the activation of JAK/STAT6 signaling [30].

It is becoming evident that hexose availability in tissue microenvironments has a profound impact on the molecular reprogramming of immune cells. As mentioned above, a high glucose environment promotes the proinflammatory activation of macrophages and effector T cells, emphasizing the close association between dietary glucose intake and inflammatory diseases. In contrast, under a low-glucose, high-lactate condition, such as in the gut lamina propria, CD4+ T cells are more likely to differentiate into Treg cells rather than effector T cells. Forkhead box P3 (Foxp3), the master transcription factor for Tregs, inhibits the expression of Myc and Myc-dependent glycolytic pathway [179]. This environment-directed reprogramming of Treg differentiation is necessary for immune tolerance in the gut, in order to prevent autoimmune responses against self- or commensal-derived antigens. On the other hand, tumor microenvironment is also featured by substantial glucose consumption and lactate accumulation, which inevitably favors Treg-mediated immune suppression.

Fructose metabolism (fructolysis) shares some common pathways and intermediates with glycolysis. Intracellular fructose is rapidly phosphorylated to fructose-1-phosphate (F-1-P) by ketohexokinase (KHK), and ultimately converts into glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (G-3-P) to enter glycolysis cascade. In addition, since fructolysis bypasses the rate-limiting step of glycolysis catalyzed by PFK1, its rate is theoretically faster than glycolysis [180]. Moreover, uric acid generated from fructose metabolism also facilitates glycolysis by inhibiting the activity of aconitase, which converts citrate into isocitrate in the TCA cycle [181], [182]. In cancer cells, fructose activates glycolytic pathway to facilitate tumor progression [183], [184]. However, in monocytes, fructose exposure only led to a modest increase in glycolysis [185]. Instead, fructose-treated monocytes maintained a high level of oxidative metabolism. In contrast to glucose-derived pyruvate which is primarily used for lactate production, fructose-derived pyruvate was more inclined to support the TCA cycle, whose metabolic intermediates activate mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling, leading to an increase in the production of inflammatory cytokines [74]. Interestingly, in the same study, fructose did not appear to affect the proliferation or cytokine production by inflammatory T cells [74]. Therefore, it seems that the fructose metabolic pathway is cell-type specific, and further elucidation of the underlying mechanisms is needed.

Similar to fructose, galactose is incorporated into glycolysis after being converted to G-6-P through the Leloir pathway. However, since galactose requires additional ATP molecules to enter glycolytic pathway, its metabolism through glycolysis produces no net ATP molecule [186]. Instead, galactose is primarily metabolized through OXPHOS in mitochondria. Galactose-derived galactitol inhibited the activity of electron transport chain (ETC) and thus led to ROS production [187]. The substitution of glucose for galactose led to immune cell apoptosis [74], [188], presumably due to ATP deprivation and oxidative damage.

In contrast to glucose and fructose, mannose is rarely utilized for glycolysis. In fact, under physiological conditions, mannose-derived mannose-6-phosphate (M−6−P) can enter glycolytic metabolism after being converted into F-6-P by phosphomannose isomerase (PMI). This might explain that in glucose-deprived conditions, mannose can serve as an alternative nutrient to drive the differentiation of IFN-γ-producing Th1 cells [114]. However, upon uptaking high exogenous mannose, the overaccumulation of M−6−P strongly inhibits the activity of multiple glycolytic enzymes, including HK, phosphoglucose isomerase (PGI), and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase [189], [190]. This mannose-mediated glycolysis inhibition counteracted the inflammatory responses in immune cells. Interestingly, although glycolysis is well-known to activate the transcription of inflammatory genes, Xiao et al. reported that mannose-induced blockade of glycolytic flux reduced the production of TNF-α in macrophages without affecting its mRNA level, nor did mannose reduce the phosphorylation of NF-κB and mitogen activated protein kinases (MAPKs). Rather, mannose interfered with the synthesis of G-3-P. As a result, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was liberated from G-3-P, enabling it to bind to TNF-α mRNA and inhibiting its translation in macrophages [107]. Compared to the inhibited glycolysis, oxidative metabolism was enhanced by mannose in T cells, which favored the differentiation of Tregs [110].

The metabolic pathways of major hexoses are interconnected, either promoting or counteracting each other (Fig. 6). Of note, the metabolism of hexoses is not a closed system, it is only a part of the cellular metabolic network constituting lipids, amino acids, other types of sugars, inorganic substances, and their metabolic intermediates. How the entire system works in different immune cells is far from being fully understood.

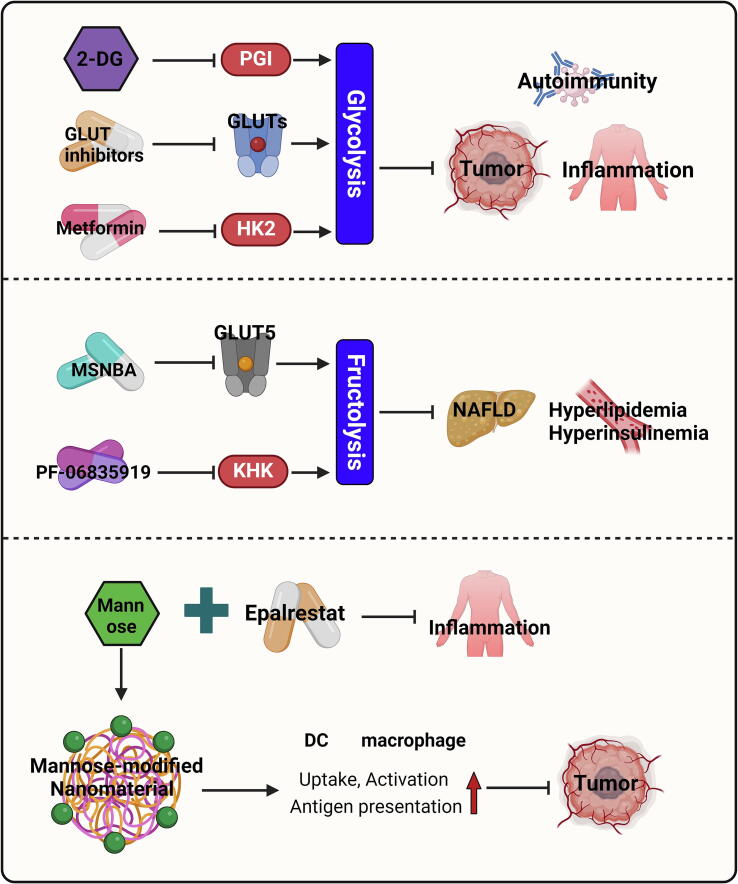

Therapeutic implications

Nowadays, targeting hexose metabolism has been attracting increasing attention in disease control (Fig. 7). Various inhibitors of GLUTs have been developed for the treatment of cancer and immune diseases, such as BAY-876, WZB117, and CG-5 [191], [192], [193]. BAY-876 suppressed the proliferation and inflammatory cytokine production in CD4+ T cells and macrophages [191]. WZB117 inhibited the generation of autoreactive CD8+ stem memory T cells in patients with type 1 diabetes [194], and reduced lymphocyte infiltration in skin inflammation [195]. CG-5 favored the differentiation of Tregs, while inhibiting the differentiation of Th1 and Th17 cells, thereby ameliorating autoimmune diseases [196]. Despite their therapeutic effectiveness, potential concerns are also raised regarding the side effects of GLUT inhibitors, as glucose is essential for many fundamental activities in almost all cells. The glucose analog 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG) is commonly used to block glycolysis in pre-clinical models by inhibiting PGI activity. When it comes to clinical application, the administration of 2-DG as an adjuvant exhibited therapeutic effects in patients with cancer or inflammation. However, adverse side effects have been observed, such as hyperglycemia, headache, palpitations, or diarrhea [197], [198], [199]. In addition, 2-DG also impaired the glycolysis-dependent anti-tumor functions of Th1 cells and CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) [45], [200]. Encouragingly, metformin, another glycolysis inhibitor that blocks HK2 activity, has been widely tested in clinical trials without obvious adverse effects. Although metformin also suppresses the functions of Th1 cells and CD8+ T cells in inflammatory diseases [201], [202], evidence from tumor models indicates that metformin administration improved anti-tumor immunity by multiple mechanisms [203], [204], [205]. The reasons for these seemingly contradictory conclusions are complex. For instance, in tumor microenvironment there is extensive competition for glucose between tumor cells and stromal cells. Metformin might be more toxic to tumor cells than to immune cells, thereby increasing glucose availability for immune cells. In addition, the reduced anaerobic glycolysis in tumor cells upon metformin treatment prevents the local accumulation of lactic acid, which favors the function of Tregs, M2 macrophages, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells [206], [207], [208]. Another explanation is that metformin directly downregulates the production of immunosuppressive mediators in tumor cells by disrupting glycolysis. It is also possible that metformin regulates anti-tumor immunity independent of glycolysis inhibition.

Fig. 7.

Targeting hexose metabolism as immunotherapy strategies.

Compounds targeting fructose metabolism have also been developed. Thompson et al. identified a specific GLUT5 inhibitor, MSNBA, which specifically reduced fructose uptake. MSNBA treatment sensitized colorectal cancer cells to chemotherapy agents [209], while its effect on immune cells has not been tested yet. PF-06835919, a ketohexokinase inhibitor, blocked fructose catabolism and mitigated HFD-induced hyperlipidemia, hyperinsulinemia, and steatosis [210]. Encouragingly, PF-06835919 was well tolerated in human participants in a phase 2 clinical trial. In this study, PF-06835919 treatment reduced inflammatory parameters and glycemic parameters in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) patients [211], indicating its significant translational potential.

As mentioned above, mannose can serve as a therapeutic agent via antagonizing glucose metabolism. Another major metabolic flux of mannose is its participation in protein N-glycosylation, a process catalyzed by phosphomannomutase 2 (PMM2) [212]. Therefore, epalrestat, a clinically approved drug with PMM2 activator activity, sensitized the therapeutic effect of mannose in colitis by rectifying the abnormal protein N-glycosylation in intestinal epithelial cells [107]. Apart from its role in metabolic regulation, mannose can be utilized to achieve cell-specific drug delivery. APCs such as DCs and macrophages express high levels of mannose receptor − MRC1. Therefore, mannose-modified drugs or nanoparticles are preferentially captured by these cells for many therapeutic purposes [213]. For example, mannose modification of nanoparticles coated with tumor-specific antigens enhanced their uptake and antigen presentation by DCs, leading to improved antitumor immunity of tumor vaccines [214]. Similarly, mannose-modified carbon nanotubes have a stronger binding capacity to DCs, and promoted their maturation and antigen presentation [215]. Mannose modification of polyethylenimine enhanced its antibacterial ability against Escherichia coli, meanwhile reducing cytotoxicity to host cells [216]. Mannose modification promoted the uptake of gadolinium liposomes by macrophages, thereby enhancing the capacity of magnetic resonance imaging in acute pancreatitis [217]. The mannosylated hyaluronic acid nanocapsules were more easily taken up by M2 macrophages compared to the unmodified control, and exhibited higher accumulation in tumor tissues [218]. In summary, the promising potential of mannose-functionalized carriers in enhancing protective immune responses has been validated in several recent studies [219], [220], [221].

Overall, despite the development of drugs that target hexose metabolism, the most effective “drug” might be the “mouth inhibitor” from patients themselves to control the intake of dietary sugars.

Conclusion and perspectives

In the past few years, our understanding of the biological effects of hexoses has been greatly expanded. The growing knowledge in this field highlights that hexose metabolism may serve as potential therapeutic targets in immune disorders. Based on the existing results, it is evident that hexoses regulate immune responses in a cell-specific manner. In general, hexoses that lead to enhanced glycolytic flux support the functions of pro-inflammatory or cytotoxic immune cells, as these cells require rapid ATP production to satisfy their biosynthetic needs for proliferation and cytokine production. However, in pathological tissue microenvironments, pathogens, tumor cells, or other neighbouring cells compete with immune cells for nutrients to support their own functions [222]. Therefore, modulating hexose metabolism in specific types of immune cells poses a challenge for hexose-based therapeutics. The competition also occurs intracellularly among different nutrients. For example, both glucose and glutamine serve as primary energy sources of cells. Inhibition of glutamine catabolism (glutaminolysis) by a glutaminase inhibitor forces cells to increase glycolysis to meet energy demands. Similarly, the disrupted glutamine uptake reprogrammed TAMs from OXPHOS toward glycolysis. Mannose did not affect the differentiation of Th1 cells in the presence of glucose, while it can serve as an alternative nutrient to induce Th1 differentiation when glucose is deprived. Therefore, hexoses are only a part of the whole metabolome within cells, their immunoregulatory effects should be considered more comprehensively.

At present, the rapidly expanding studies on immunoregulatory hexoses raise numerous unresolved questions. First, unlike the conclusions drawn from animal models, the effect of hexoses on human diseases cannot be simply categorized as “helpful” or “unhelpful”, and is complicated by variations in etiology, genetic backgrounds, lifestyles, dietary habits, or tissue microenvironments. Well-designed clinical trials are required to gain a comprehensive understanding of the impact of hexoses on individual patient’s disease status. The balance between therapeutic benefits and side effects should also be taken into account. At present, there is a lack of real-world study (RWS) on hexoses. This also reflects a challenging gap between preclinical models and the actual pathogenesis of human diseases. In many studies involving animal models, hexoses are administered at supraphysiological doses throughout the disease process, leading to a rapid increase in systemic hexose concentration. In reality, hexoses are consumed in a chronic, long-term manner at relatively low doses compared to their use in animal disease models. To what extent conclusions drawn from preclinical models (particularly acute disease models) reflect the actual immunoregulatory roles of hexoses is challenging to determine. It is worth noting that animals administered with high-dose hexoses may have altered consumption of drinking water or food [223], [224]. Additionally, mental stress was observed in animals given exogenous hexoses, such as anxiety or depression, probably due to increased neuroinflammationy [225], [226]. Thus, hexose-induced phenotypic changes in animals may be multifactorial.

On the other hand, the precise molecular mechanisms underlying the immunoregulatory functions of hexoses are less understood. Unlike cytokines and other extracellular or intracellular ligands, the mechanisms through which hexoses exert their immunomodulatory roles are multifaceted. They can bind to specific receptors to activate downstream signaling pathways, or through metabolic regulation to influence cell functions. Due to the complex intracellular metabolic network, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish whether the observed phenotypes are caused by the hexoses themselves or by their metabolic intermediates. On the other hand, although the development of single-cell technology has provided powerful tools for dissecting gene expression at the single-cell level, its application in analyzing cellular metabolic activities is relatively limited. Another layer of complexity arises from the cell type-specific effects of hexoses as mentioned above. Therefore, how to achieve the local or cell type-specific delivery of hexoses is crucial for improving their therapeutic efficacy, while minimizing adverse effects. Advancements in biomaterial technology can hopefully provide solutions to this issue. The association between sugar consumption and disease risk has already been recognized for decades through large-scale epidemic investigation, and there are many ongoing clinical trials designed to assess the impact of dietary sugars on human health, particularly metabolic diseases such as obesity and diabetes. However, the immunological parameters still lack in-depth investigation in previous studies. For instance, the associations between hexose consumption and the quantity or functionality of immune cells, the effects of hexose on anti-tumor immunity in cancer patients, whether hexoses influence the effectiveness of immunotherapy in diseases, etc.

As the most abundant monosaccharides in the human daily diet, hexoses have profound impacts on human immune system. Research progress on this topic will undoubtedly be helpful for the prevention and treatment of immunological diseases. Furthermore, it can also provide new guidelines to the food industry, with the hope of developing dietary recipes suitable for patients suffering from various immunological diseases.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82171730 to PX). Figures were created with BioRender.com

Biographies

Dr. Junjie Xu is a professor at Zhejiang University School of Medicine. Prof. Xu’s work focuses on the microenvironmental regulation of cancer, such as the crosstalk between immune cells and tumor cells, and the development of novel immunotherapy approaches for cancer. Up to now, Prof. Xu published a series of high impact works in scientific journals.

Ms. Yuening Zhao is a master’s student in Zhejiang University School of Medicine. She earned her bachelor’s degree at Soochow University. At present, Ms. Zhao is working on tumor immunology in Dr. Xiao’s lab.

Dr. Randall Tyler Mertens is now working as a postdoctoral fellow at the Department of Immunology, Harvard Medical School. He earned his PhD degree at University of Kentucky. Dr. Mertens’s current research focuses on the immunological mechanisms of cancer and inflammation, with special interest in macrophages.

Dr. Yimin Ding is a post-doctoral fellow at Zhejiang University. She earned her MD degree at Zhejiang University. Dr. Ding’s current work focuses on the metabolic regulation of tumor-associated macrophages in liver cancer, colorectal cancer, and pancreatic cancer.

Dr. Peng Xiao is a associated professor in Zhejiang University School of Medicine. Dr. Xiao completed his PhD degree at Institute of Immunology, Zhejiang University, then worked as a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard Medical School. His research focuses on the functional regulation of immune cells, particularly macrophages, in the context of cancer and inflammation. At present, Dr. Xiao’s lab aims to combine basic research and translational medicine in order to find new therapeutic targets in the immunotherapy of cancer and inflammation.

References

- 1.Colak G., Xie Z., Zhu A.Y., Dai L., Lu Z., Zhang Y., et al. Identification of lysine succinylation substrates and the succinylation regulatory enzyme CobB in Escherichia coli. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12(12):3509–3520. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.031567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen A.N., Luo Y., Yang Y.H., Fu J.T., Geng X.M., Shi J.P., et al. Lactylation, a Novel Metabolic Reprogramming Code: Current Status and Prospects. Front Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.688910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reily C., Stewart T.J., Renfrow M.B., Novak J. Glycosylation in health and disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2019;15(6):346–366. doi: 10.1038/s41581-019-0129-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Navale A.M., Paranjape A.N. Glucose transporters: physiological and pathological roles. Biophys Rev. 2016;8(1):5–9. doi: 10.1007/s12551-015-0186-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ganeshan K., Chawla A. Metabolic regulation of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014;32:609–634. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Britt E.C., Lika J., Giese M.A., Schoen T.J., Seim G.L., Huang Z., et al. Switching to the cyclic pentose phosphate pathway powers the oxidative burst in activated neutrophils. Nat Metab. 2022;4(3):389–403. doi: 10.1038/s42255-022-00550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan Z., Xie N., Banerjee S., Cui H., Fu M., Thannickal V.J., et al. The monocarboxylate transporter 4 is required for glycolytic reprogramming and inflammatory response in macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(1):46–55. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.603589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baseler W.A., Davies L.C., Quigley L., Ridnour L.A., Weiss J.M., Hussain S.P., et al. Autocrine IL-10 functions as a rheostat for M1 macrophage glycolytic commitment by tuning nitric oxide production. Redox Biol. 2016;10:12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahnke J., Schumacher V., Ahrens S., Kading N., Feldhoff L.M., Huber M., et al. Interferon Regulatory Factor 4 controls T(H1) cell effector function and metabolism. Sci Rep. 2016;6:35521. doi: 10.1038/srep35521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krawczyk C.M., Holowka T., Sun J., Blagih J., Amiel E., DeBerardinis R.J., et al. Toll-like receptor-induced changes in glycolytic metabolism regulate dendritic cell activation. Blood. 2010;115(23):4742–4749. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-249540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macintyre A.N., Gerriets V.A., Nichols A.G., Michalek R.D., Rudolph M.C., Deoliveira D., et al. The glucose transporter Glut1 is selectively essential for CD4 T cell activation and effector function. Cell Metab. 2014;20(1):61–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma J., Hu W., Liu Y., Duan C., Zhang D., Wang Y., et al. CD226 maintains regulatory T cell phenotype stability and metabolism by the mTOR/Myc pathway under inflammatory conditions. Cell Rep. 2023;42(10) doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.113306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen S., Saeed A., Liu Q., Jiang Q., Xu H., Xiao G.G., et al. Macrophages in immunoregulation and therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):207. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01452-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan Z., Xie N., Cui H., Moellering D.R., Abraham E., Thannickal V.J., et al. Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 participates in macrophage polarization via regulating glucose metabolism. J Immunol. 2015;194(12):6082–6089. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang B., Yang Y., Yi J., Zhao Z., Ye R. Hyperglycemia modulates M1/M2 macrophage polarization via reactive oxygen species overproduction in ligature-induced periodontitis. J Periodontal Res. 2021;56(5):991–1005. doi: 10.1111/jre.12912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang X., Yang Y., Zhao Y. Macrophage phenotype and its relationship with renal function in human diabetic nephropathy. PLoS One. 2019;14(9):e0221991. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diwan B., Yadav R., Goyal R., Sharma R. Sustained exposure to high glucose induces differential expression of cellular senescence markers in murine macrophages but impairs immunosurveillance response to senescent cells secretome. Biogerontology. 2024 doi: 10.1007/s10522-024-10092-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fang C., Ren P., Bian G., Wang J., Bai J., Huang J., et al. Enhancing Spns2/S1P in macrophages alleviates hyperinflammation and prevents immunosuppression in sepsis. EMBO Rep. 2023 doi: 10.15252/embr.202256635. e56635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu H., Zhao Y., Zhao Q., Shi M., Zhang Z., Ding W., et al. Tuberous Sclerosis Complex 1 Deficiency in Macrophages Promotes Unclassical Inflammatory Response to Lipopolysaccharide In Vitro and Dextran Sodium Sulfate-Induced Colitis in Mice. Aging Dis. 2022;13(6):1875–1890. doi: 10.14336/AD.2022.0408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y., Gao Y., Ding Y., Jiang Y., Chen H., Zhan Z., et al. Targeting KAT2A inhibits inflammatory macrophage activation and rheumatoid arthritis through epigenetic and metabolic reprogramming. MedComm. 2020;2023;4(3):e306 doi: 10.1002/mco2.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu Y., Mu M., RenChen X., Wang W., Zhu Y., Zhong M., et al. 2-Deoxy-D-glucose ameliorates inflammation and fibrosis in a silicosis mouse model by inhibiting hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha in alveolar macrophages. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2024;269 doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2023.115767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weng W., Gui L., Zhang Y., Chen J., Zhu W., Liang Z., et al. PKM2 Promotes Pro-Inflammatory Macrophage Activation in Ankylosing Spondylitis. J Leukoc Biol. 2023 doi: 10.1093/jleuko/qiad054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hou Y., Wang Y., Tang K., Yang Y., Wang Y., Liu R., et al. CD226 deficiency attenuates cardiac early pathological remodeling and dysfunction via decreasing inflammatory macrophage proportion and macrophage glycolysis in STZ-induced diabetic mice. FASEB J. 2023;37(8):e23047. doi: 10.1096/fj.202300424RR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai S.L., Fan X.G., Wu J., Wang Y., Hu X.W., Pei S.Y., et al. CB2R agonist GW405833 alleviates acute liver failure in mice via inhibiting HIF-1alpha-mediated reprogramming of glycometabolism and macrophage proliferation. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2023;44(7):1391–1403. doi: 10.1038/s41401-022-01037-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reinfeld B.I., Madden M.Z., Wolf M.M., Chytil A., Bader J.E., Patterson A.R., et al. Cell-programmed nutrient partitioning in the tumour microenvironment. Nature. 2021;593(7858):282–288. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03442-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang Z., Liu Z., Li M., Chen C., Wang X. Increased glycolysis correlates with elevated immune activity in tumor immune microenvironment. EBioMedicine. 2019;42:431–442. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.03.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muller S., Kohanbash G., Liu S.J., Alvarado B., Carrera D., Bhaduri A., et al. Single-cell profiling of human gliomas reveals macrophage ontogeny as a basis for regional differences in macrophage activation in the tumor microenvironment. Genome Biol. 2017;18(1):234. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1362-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen S., Cui W., Chi Z., Xiao Q., Hu T., Ye Q., et al. Tumor-associated macrophages are shaped by intratumoral high potassium via Kir2.1. Cell Metab. 2022;34(11):1843–59 e11. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2022.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yen J.H., Huang W.C., Lin S.C., Huang Y.W., Chio W.T., Tsay G.J., et al. Metabolic remodeling in tumor-associated macrophages contributing to antitumor activity of cryptotanshinone by regulating TRAF6-ASK1 axis. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2022;26:158–174. doi: 10.1016/j.omto.2022.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang F., Zhang S., Vuckovic I., Jeon R., Lerman A., Folmes C.D., et al. Glycolytic Stimulation Is Not a Requirement for M2 Macrophage Differentiation. Cell Metab. 2018;28(3):463–75 e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang S.C., Smith A.M., Everts B., Colonna M., Pearce E.L., Schilling J.D., et al. Metabolic Reprogramming Mediated by the mTORC2-IRF4 Signaling Axis Is Essential for Macrophage Alternative Activation. Immunity. 2016;45(4):817–830. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Md-B N., Duncan-Moretti J., Cd-C H., Saldanha-Gama R., Paula-Neto H.A., G gd, et al. Aerobic glycolysis is a metabolic requirement to maintain the M2-like polarization of tumor-associated macrophages. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2020;1867(2):118604. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2019.118604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi Q., Shen Q., Liu Y., Shi Y., Huang W., Wang X., et al. Increased glucose metabolism in TAMs fuels O-GlcNAcylation of lysosomal Cathepsin B to promote cancer metastasis and chemoresistance. Cancer Cell. 2022;40(10):1207–22 e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2022.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maschalidi S., Mehrotra P., Keceli B.N., De Cleene H.K.L., Lecomte K., Van der Cruyssen R., et al. Targeting SLC7A11 improves efferocytosis by dendritic cells and wound healing in diabetes. Nature. 2022;606(7915):776–784. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04754-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bai Z., Ye Y., Ye X., Yuan B., Tang Y., Wei J., et al. Leptin promotes glycolytic metabolism to induce dendritic cells activation via STAT3-HK2 pathway. Immunol Lett. 2021;239:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2021.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perrin-Cocon L., Aublin-Gex A., Diaz O., Ramiere C., Peri F., Andre P., et al. Toll-like Receptor 4-Induced Glycolytic Burst in Human Monocyte-Derived Dendritic Cells Results from p38-Dependent Stabilization of HIF-1alpha and Increased Hexokinase II Expression. J Immunol. 2018;201(5):1510–1521. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hatano N., Itoh Y., Suzuki H., Muraki Y., Hayashi H., Onozaki K., et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha (HIF1alpha) switches on transient receptor potential ankyrin repeat 1 (TRPA1) gene expression via a hypoxia response element-like motif to modulate cytokine release. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(38):31962–31972. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.361139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guak H., Al Habyan S., Ma E.H., Aldossary H., Al-Masri M., Won S.Y., et al. Glycolytic metabolism is essential for CCR7 oligomerization and dendritic cell migration. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):2463. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04804-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lawless S.J., Kedia-Mehta N., Walls J.F., McGarrigle R., Convery O., Sinclair L.V., et al. Glucose represses dendritic cell-induced T cell responses. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15620. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stark J.M., Tibbitt C.A., Coquet J.M. The Metabolic Requirements of Th2 Cell Differentiation. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2318. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peng M., Yin N., Chhangawala S., Xu K., Leslie C.S., Li M.O. Aerobic glycolysis promotes T helper 1 cell differentiation through an epigenetic mechanism. Science. 2016;354(6311):481–484. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf6284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Papadopoulou G., Xanthou G. Metabolic rewiring: a new master of Th17 cell plasticity and heterogeneity. FEBS J. 2022;289(9):2448–2466. doi: 10.1111/febs.15853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang C.H., Curtis J.D., Maggi L.B., Jr., Faubert B., Villarino A.V., O'Sullivan D., et al. Posttranscriptional control of T cell effector function by aerobic glycolysis. Cell. 2013;153(6):1239–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maekawa Y., Ishifune C., Tsukumo S., Hozumi K., Yagita H., Yasutomo K. Notch controls the survival of memory CD4+ T cells by regulating glucose uptake. Nat Med. 2015;21(1):55–61. doi: 10.1038/nm.3758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gerriets V.A., Kishton R.J., Nichols A.G., Macintyre A.N., Inoue M., Ilkayeva O., et al. Metabolic programming and PDHK1 control CD4+ T cell subsets and inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(1):194–207. doi: 10.1172/JCI76012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Watson M.J., Vignali P.D.A., Mullett S.J., Overacre-Delgoffe A.E., Peralta R.M., Grebinoski S., et al. Metabolic support of tumour-infiltrating regulatory T cells by lactic acid. Nature. 2021;591(7851):645–651. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-03045-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cribioli E., Giordano Attianese G.M.P., Ginefra P., Signorino-Gelo A., Vuillefroy de Silly R., Vannini N., et al. Enforcing GLUT3 expression in CD8(+) T cells improves fitness and tumor control by promoting glucose uptake and energy storage. Front Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.976628. 976628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ho P.C., Bihuniak J.D., Macintyre A.N., Staron M., Liu X., Amezquita R., et al. Phosphoenolpyruvate Is a Metabolic Checkpoint of Anti-tumor T Cell Responses. Cell. 2015;162(6):1217–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Z., Guan D., Wang S., Chai L.Y.A., Xu S., Lam K.P. Glycolysis and Oxidative Phosphorylation Play Critical Roles in Natural Killer Cell Receptor-Mediated Natural Killer Cell Functions. Front Immunol. 2020;11:202. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu B., Yu M., Ma X., Sun J., Liu C., Wang C., et al. IFNalpha Potentiates Anti-PD-1 Efficacy by Remodeling Glucose Metabolism in the Hepatocellular Carcinoma Microenvironment. Cancer Discov. 2022;12(7):1718–1741. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patsoukis N., Bardhan K., Chatterjee P., Sari D., Liu B., Bell L.N., et al. PD-1 alters T-cell metabolic reprogramming by inhibiting glycolysis and promoting lipolysis and fatty acid oxidation. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6692. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chang C.H., Qiu J., O'Sullivan D., Buck M.D., Noguchi T., Curtis J.D., et al. Metabolic Competition in the Tumor Microenvironment Is a Driver of Cancer Progression. Cell. 2015;162(6):1229–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sukumar M., Liu J., Ji Y., Subramanian M., Crompton J.G., Yu Z., et al. Inhibiting glycolytic metabolism enhances CD8+ T cell memory and antitumor function. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(10):4479–4488. doi: 10.1172/JCI69589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mu X., Xiang Z., Xu Y., He J., Lu J., Chen Y., et al. Glucose metabolism controls human gammadelta T-cell-mediated tumor immunosurveillance in diabetes. Cell Mol Immunol. 2022;19(8):944–956. doi: 10.1038/s41423-022-00894-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Khan S., Waliullah S., Godfrey V., Khan M.A.W., Ramachandran R.A., Cantarel B.L., et al. Dietary simple sugars alter microbial ecology in the gut and promote colitis in mice. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12(567) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aay6218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hochrein S.M., Wu H., Eckstein M., Arrigoni L., Herman J.S., Schumacher F., et al. The glucose transporter GLUT3 controls T helper 17 cell responses through glycolytic-epigenetic reprogramming. Cell Metab. 2022;34(4):516–32 e11. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2022.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang D., Jin W., Wu R., Li J., Park S.A., Tu E., et al. High Glucose Intake Exacerbates Autoimmunity through Reactive-Oxygen-Species-Mediated TGF-beta Cytokine Activation. Immunity. 2019;51(4):671–81 e5. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Choi S.C., Titov A.A., Abboud G., Seay H.R., Brusko T.M., Roopenian D.C., et al. Inhibition of glucose metabolism selectively targets autoreactive follicular helper T cells. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):4369. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06686-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ikumi K., Odanaka M., Shime H., Imai M., Osaga S., Taguchi O., et al. Hyperglycemia Is Associated with Psoriatic Inflammation in Both Humans and Mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139(6):1329–38 e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2019.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lepper P.M., Ott S., Nuesch E., von Eynatten M., Schumann C., Pletz M.W., et al. Serum glucose levels for predicting death in patients admitted to hospital for community acquired pneumonia: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2012;344:e3397. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ellulu M.S., Samouda H. Clinical and biological risk factors associated with inflammation in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMC Endocr Disord. 2022;22(1):16. doi: 10.1186/s12902-021-00925-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li W., Zhang X., Sang H., Zhou Y., Shang C., Wang Y., et al. Effects of hyperglycemia on the progression of tumor diseases. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38(1):327. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1309-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lega I.C., Lipscombe L.L. Review: Diabetes, Obesity, and Cancer-Pathophysiology and Clinical Implications. Endocr Rev. 2020;41(1) doi: 10.1210/endrev/bnz014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Davila J.A., Morgan R.O., Shaib Y., McGlynn K.A., El-Serag H.B. Diabetes increases the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States: a population based case control study. Gut. 2005;54(4):533–539. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.052167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pearson-Stuttard J., Papadimitriou N., Markozannes G., Cividini S., Kakourou A., Gill D., et al. Type 2 Diabetes and Cancer: An Umbrella Review of Observational and Mendelian Randomization Studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2021;30(6):1218–1228. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-20-1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hanover L.M., White J.S. Manufacturing, composition, and applications of fructose. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;58(5 Suppl):724S–S732. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/58.5.724S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]