Abstract

Throughout our lifetime the heart executes cycles of contraction and relaxation to meet the body's ever‐changing metabolic needs. This vital function is continuously regulated by the autonomic nervous system. Cardiovascular dysfunction and autonomic dysregulation are also closely associated; however, the degrees of cause and effect are not always readily discernible. Thus, to better understand cardiovascular disorders, it is crucial to develop model systems that can be used to study the neurocardiac interaction in healthy and diseased states. Human pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC) technology offers a unique human‐based modelling system that allows for studies of disease effects on the cells of the heart and autonomic neurons as well as of their interaction. In this review, we summarize current understanding of the embryonic development of the autonomic, cardiac and neurocardiac systems, their regulation, as well as recent progress of in vitro modelling systems based on hiPSCs. We further discuss the advantages and limitations of hiPSC‐based models in neurocardiac research.

Keywords: autonomic nervous system, cardiology, disease modelling, human pluripotent stem cell, neurocardiology

Abstract figure legend Summary of strategies in modelling neurocardiac interactions using human pluripotent stem cells.

Applying human pluripotent stem cell technology to model human physiology

Over the last few decades, and in response to increasing calls for human‐derived systems to model human physiology and pathophysiology, there has been a dramatic increase in studies applying human pluripotent stem cell [hiPSC, a combined term of embryonic stem cells (hESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs)] technology (Guhr et al., 2018; Ludwig et al., 2018). In essence, hiPSCs are pluripotent cells that have the capability to self‐renew indefinitely, providing unlimited untransformed human cellular material (Zhu & Huangfu, 2013). Per definition, hiPSCs can be directed to differentiate into any cell type of the body, including germline cells, giving researchers access to unlimited numbers of human tissue cells (Liu et al., 2020; Saito‐Diaz & Zeltner, 2019). However, this is only possible if high‐quality in vitro differentiation protocols can be established to derive the specific cell type of interest (Saito‐Diaz & Zeltner, 2019; Zhu & Huangfu, 2013).

There are two main methods to differentiate hiPSCs into desired cell types, directed differentiation and trans‐differentiation (Cieslar‐Pobuda et al., 2017). Directed (or guided) differentiation refers to the process where hiPSCs are induced into the desired cell type by following the appropriate developmental process step by step and mimicking cellular development in the dish (Liu et al., 2020). This enables in vitro modelling of the entire developmental lifespan of specific cell types. However, the process is time‐consuming compared to trans‐differentiation (another method discussed below), and the need for various high‐quality growth factors and small molecules raises the bar of accessibility and reproducibility since these factors are costly and display high batch‐to‐batch variability. Commercial kits are now available to differentiate some common cell types, for example general neuron populations. The kits are standardized for consistency and affordability, and allow for relatively fast cell differentiations. However, kits are not available for all cell types, and specifically very specialized cell types may not be available. Overall, using directed differentiation approaches, it may be challenging for researchers to precisely reproduce certain protocols, which can be attributed to the constantly evolving/optimizing nature of the hiPSC technology. In the trans‐differentiation approach, somatic cells are re‐directed into a different cell fate (usually a stem cell or progenitor cell fate). For example, skin fibroblasts can be directed to become a neural progenitor using specific transcription factors (Cieslar‐Pobuda et al., 2017; Saito‐Diaz & Zeltner, 2019; Wang et al., 2015; Zhu & Huangfu, 2013). While trans‐differentiation allows rapid harvest of desired cell types, the developmental aspect is not accessible. The skipping of development may also lead to incomplete identity and functionality of the differentiated cells.

The hiPSC technology has four main applications for biomedical research: (1) cell replacement therapy/regenerative medicine, (2) studies of developmental biology, (3) disease modelling and (4) drug screening/discovery (Deng, 2010; Grskovic et al., 2011; Rowe & Daley, 2019; Yamanaka, 2020). (1) Cell replacement therapy/regenerative medicine, the best‐known approach today, aims to generate cells that are lost in a patient due to disease or injury. Those cells are generated in vitro from hiPSCs and are then transplanted into the patient to replenish the lost function. For instance, a research group led by Dr Lorenz Studer in collaboration with BlueRock Therapeutics recently initiated a Phase I human clinical trial for Parkinson's disease (PD) therapy, in which hESC‐derived midbrain dopaminergic neurons were engrafted into the brain of PD patients aiming at relieving symptoms (Piao et al., 2021; Takahashi, 2021). (2) The hiPSC technology also allows fundamental cell biology and molecular/genetic biology studies aimed at understanding tissue‐specific development of healthy cells as they grow, mature and age. Using hiPSC technology, significant progress in understanding transcriptional networks for cell fate specification and tissue maturation has been made (Ciceri et al., 2024; Zhu & Huangfu, 2013). (3) Disease modelling approaches aim to model a human disease in vitro and employ defined disease phenotypes to discover novel disease mechanisms that then can be used for drug discovery. The key is to derive the diseased cell type from healthy and diseased hiPSCs and compare their phenotypes in vitro. Using hiPSC‐based disease modelling, specific cell types of interest may be generated using directed differentiation approaches to study the developmental process of certain cell lineages in healthy and diseased states, allowing a better understanding of developmental phenotypes of interest (Avior et al., 2016; Merkle & Eggan, 2013). Alternatively, one can differentiate patient and healthy control hiPSCs into the specific cell type affected by the disease, to dissect the cellular pathology without the confounding influence from the surrounding tissue and whole organism. For example, studying neurological pathology in human brain disorders, such as PD, Alzheimer's disease and schizophrenia, is mostly done in postmortem brains, which represents the end phase of the disease. Using directed differentiation, Brennand et al. (2011) derived brain neurons from healthy and schizophrenia patient‐derived hiPSCs, and systematically compared the phenotypes in early neural progenitors and neural development. With the power of hiPSC disease modelling, they found impaired neural networks in schizophrenia in early development (Brennand et al., 2011). (4) Drug screening/discovery approaches aim to employ the phenotypes discovered via disease modelling for drug screening. The goal is to discover compounds that reverse these phenotypes and thus are novel treatment candidates. One advantage of hiPSC technology is that it enables high‐throughput studies, due to the availability of large numbers of cells, making it ideal for drug screening approaches (Rajamohan et al., 2013). For instance, with phenotypically characterized hiPSC‐derived disease models, drug screening using FDA‐approved compound libraries with thousands of drugs and variable dosages can be efficiently achieved (Morimoto et al., 2023; Rajamohan et al., 2013). Additionally, hiPSC technology allows for drug screening while taking the genetic background of patients into account, which is not feasible using animal models. With this unlimited cell source, scientists are also able to perform high‐content CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) screening to systematically identify the function of thousands of genes in individual cell types (Li, Ouyang et al., 2023).

Autonomic nervous system

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) belongs to the peripheral nervous system (PNS) and regulates body homeostasis by controlling unconscious physiological responses, including heart rate, blood pressure, blood glucose levels, respiration, digestion and gland secretion (McCorry, 2007). There are three branches of nervous systems under the ANS, the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), the parasympathetic nervous system (PSNS) and the enteric nervous system (ENS). Compared to the ENS, a highly specified and independent ANS branch, that solely regulates gastrointestinal functions (Spencer & Hu, 2020), the SNS and the PSNS control a wide variety of organs in the body and play crucial roles in cardiovascular regulation (McCorry, 2007; Scott‐Solomon et al., 2021). In this review, we will focus on the SNS and the PSNS.

ANS anatomy

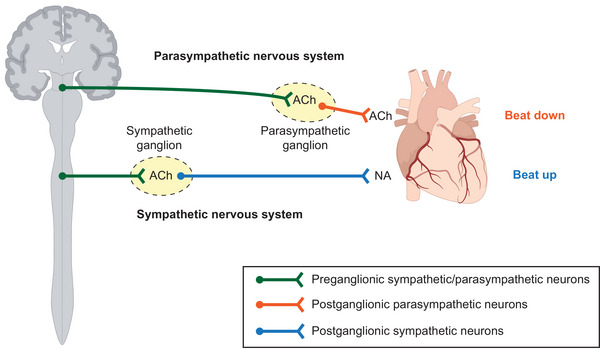

Both the SNS and the PSNS employ a two‐neuron system consisting of preganglionic and postganglionic neurons (Fig. 1). The preganglionic sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve cell bodies reside in the spinal cord. Since the spinal cord belongs to the central nervous system (CNS), the nature of preganglionic sympathetic and parasympathetic neurons is anatomically closer to that of spinal motor neurons of the CNS (Waxenbaum et al., 2023). Additionally, they share their developmental origin (PAX6+ neurectoderm) with the CNS, in contrast to all postganglionic neurons which are derived from the neural crest. Thus, here all preganglionic neurons are classified as pertaining to the CNS.

Figure 1. Efferent neurocardiac system.

Simplified anatomy and physiology of the efferent neurocardiac system.

Postganglionic sympathetic neurons (symNs) form sympathetic ganglia, which locate close to, but not inside, the spinal cord. In contrast, postganglionic parasympathetic neurons (parasymNs) form ganglia closer to the target tissue (Fig. 1) (Waxenbaum et al., 2023). While some organs (minority) and tissues are innervated solely by symNs or parasymNs, the control of most organs, including heart functions, require both symN and parasymN innervation. Because the postganglionic neurons are located in the periphery (outside the CNS), and physically control organ function, the term ANS in the following sections will mainly describe postganglionic symNs and parasymNs.

ANS function

Upon receiving signals from the brain, both preganglionic symNs and parasymNs release acetylcholine (ACh) to activate postganglionic symNs and parasymNs, respectively (Fig. 1). ACh is taken up by the postganglionic symNs and parasymNs via expression of cholinergic receptors (McCorry, 2007; Waxenbaum et al., 2023). Activation of symNs then turns on the adrenergic signalling cascade and results in the release of noradrenaline (NA) (Fig. 1) into the junction between the symN axonal terminal and the target tissue. The stimulating target activation from symN signalling and NA secretion increases heart rate, vasoconstriction and muscle tension. This is known as the fight‐or‐flight response. Activation of parasymNs turns on the cholinergic signalling cascade and results in the release of ACh from postganglionic parasympathetic terminals (Fig. 1), which, when taken up by target tissues, slows heart rate and lowers blood pressure (Waxenbaum et al., 2023). This is known as the rest‐and‐digest response. The balance between SNS and PSNS is crucial to maintain body homeostasis (Buijs, 2013). Many common cardiovascular symptoms are associated with ANS imbalance. For instance, SNS overactivity is often seen in hypertension and anxiety (Bairey Merz et al., 2015).

ANS development

Like most of the cell types in the periphery, both symNs and parasymNs are derived from a multipotent progenitor, called the neural crest (NC), which is formed during neural tube formation along the dorsal axis, after embryonic day 8 (E8) in the mouse embryo (Lefcort, 2020). At this point, early NC cells (NCCs) express typical markers, such as AP2a and PAX3. Pre‐migratory NCCs express more differentiated NC markers, including FOXD3 and SNAIL2/3 (Simoes‐Costa & Bronner, 2015). Upon epithelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition (EMT), NCCs are SOX10+ and become highly migratory and are attracted towards the ventral axis, in the mouse at around E10. SymNs are derived from NCCs in the trunk and sacral region (characterized by the expression of HOX 6−13) (Espinosa‐Medina et al., 2016; Scott‐Solomon et al., 2021). During their migration, trunk NCCs differentiate to sympathetic progenitors, which can be recognized by their expressions of ASCL1/PHOX2B/HAND2/GATA2/GATA3 (Ernsberger & Rohrer, 2018; Scott‐Solomon et al., 2021). At this point, sympathetic progenitors aggregate to form ganglia structures. They further differentiate to sympathetic neuroblasts, before maturing into symNs that express adrenergic markers, such as TH and DBH (Ernsberger & Rohrer, 2018; Scott‐Solomon et al., 2021). In contrast, the majority of parasymNs are believed to be one of the derivatives of Schwann cell progenitors (SCPs), which are differentiated from a slightly later NCC pool (Dyachuk et al., 2014; Espinosa‐Medina et al., 2014). At E12.5 in the mouse, migratory cranial (HOX−) and vagal (HOX1/3/4/5+) NCCs differentiate into SCPs (Jessen & Mirsky, 2019). At this point, SCPs express specific markers, including S100, MPZ, GFAP and CD56 (Jessen & Mirsky, 2019). SCPs are associated with axons of preganglionic neurons. They further migrate along the axonal tracks close to the target organs, where they form parasympathetic ganglia that express the cholinergic markers ChAT and VAChT (Dyachuk et al., 2014; Espinosa‐Medina et al., 2014). Many more genetic markers at various stages of development have been defined for NCCs, symNs, parasymNS and SCPs; here we discuss the most well‐known and best described markers.

ANS dysfunction

Disorders of the ANS, also known as dysautonomia, occur when the ANS is damaged. Dysautonomia can be of genetic or degenerative (primary dysautonomias) nature or can be induced by injuries or other types of conditions (secondary dysautonomias) (Hovaguimian, 2023). As a result, the imbalance of ANS signalling leads to dysregulation of cardiovascular and respiratory functions. Typical symptoms of dysautonomia include heart rate abnormality, anxiety, difficulty breathing, fatigue and dizziness (Sanchez‐Manso et al., 2023). The symptoms range from mild to detrimental, can be life‐threatening and they are usually unpredictable (Sanchez‐Manso et al., 2023). Dysautonomia can present as a comorbidity to other diseases and sometimes it can be a precursor of other neurodegenerative and metabolic diseases, such as PD, Alzheimer's disease, hypertension, diabetes and autoimmune disease (Cykowski et al., 2015; Mandl et al., 2008; Taki et al., 2000; Takeda et al., 1993; Tulba et al., 2020; Verrotti et al., 2014; Vinik et al., 2003; Wakabayashi & Takahashi, 1997). Dysautonomia can also be caused by certain medications (such as chemotherapy), infections [such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2)] and alcohol misuse (Dani et al., 2021; Goldberger et al., 2019; Julian et al., 2020). A unique type of dysautonomia is caused by the inherited disorder familial dysautonomia (FD). FD is a neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorder affecting the PNS, especially the ANS (Axelrod, 2004; Bar‐Aluma, 1993; Pearson et al., 1971; Shohat & Weisz Hubshman, 1993; Slaugenhaupt & Gusella, 2002). Common symptoms in children include poor control of sweating, insensitivity to pain and temperature changes, and difficulties regulating blood pressure (Axelrod, 2004; Bar‐Aluma, 1993; Shohat & Weisz Hubshman, 1993; Slaugenhaupt & Gusella, 2002). One of the most devastating symptoms in FD patients is the dysautonomic crisis, an unpredictable severe dysregulation and dysfunction of the SNS, that is triggered by physical or emotional stress. During crisis, patients experience tachycardia, blood pressure spikes and severe nausea/vomiting/retching episodes. Interestingly, brain function (except the eye) has not been reported to be impacted in FD. It is known that 99.5% of all FD patients carry a homozygous point mutation in the elongator complex protein 1 (ELP1) gene, which is involved in transcriptional elongation and tRNA modification, yet the pathology of FD symptoms is still not fully defined (Dietrich & Dragatsis, 2016; Jackson et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2009; Lefcort et al., 2017; Rubin & Anderson, 2008). To date, the role of ANS dysfunction in FD, and specifically the pathological mechanisms in ANS neurons that lead to developmental defects, degeneration and FD crisis, remain unclear.

hiPSC models for ANS diseases

There are several published protocols for the differentiation of hiPSCs into postganglionic symNs, using directed or trans‐differentiation strategies (Liu, Xiang et al., 2023; Wu & Zeltner, 2019). However, only a few of these protocols have been applied to model ANS disorders. Lee et al. (2009)differentiated healthy and FD patient‐derived hiPSCs into NCCs and found impaired NC migration in FD. They also found that the differentiation efficiency of FD NCCs into peripheral sensory neurons was decreased, which matched clinical observations in FD patients. They further used this modelling platform to perform compound screening and identified drugs that rescued FD NC phenotypes (Lee et al., 2012). Later, Zeltner et al. (2016). took a step further and used hiPSC‐derived peripheral sensory and autonomic neurons to model the severity of FD defects. They found that the deficiency in NC and peripheral neural differentiation was limited to FD patients with severe symptoms. However, both severe and mild hiPSC‐derived peripheral neurons showed degenerative phenotypes. Surprisingly, ELP1 rescue using CRISPR‐Cas9 in severe hiPSCs only rescued NC development, but not peripheral sensory neuron development or the degeneration defect. With this in vitro model system, they performed whole exome sequencing and identified novel candidate modifier genes that may determine the severity of FD symptoms (Zeltner et al., 2016). Winbo et al. (2021) differentiated symNs from hiPSCs derived from patients with long QT syndrome type 1 (LQT1), a familial arrhythmia disorder known for sympathetically triggered cardiac events, using a modified directed differentiation protocol (Winbo et al., 2020). LQT1 is caused by loss‐of‐function variants in the KCNQ1 gene that encodes a ubiquitous potassium channel, resulting in prolongation of the cardiac action potential. While LQT1 was thought to be solely a cardiac disorder, they found functional hyperactivity of LQT1 symNs, including increased action potential firing propensity and frequency, that correlated with the severity of the KCNQ1 genotype, suggesting a significant neurocardiac component to the disease phenotype which could further explain why life‐threatening arrhythmias in LQT1 are typically associated with certain triggers, such as physical activities, swimming and emotions/stress (Winbo et al., 2021). Wu and colleagues differentiated symNs using hiPSCs from patients with FD via directed differentiation and focused on dissecting functional defects in FD symNs and its molecular mechanisms (Wu & Zeltner, 2020; Wu, Yu et al., 2022). They modelled impaired SNS development in FD, which was reflected in reduced NCC and sympathetic neuroblast numbers, and similarly to the LQT1 study, they discovered functional hyperactivity in FD symNs, which may explain sympathetic crisis and potentially ensuing symN loss in patients (Wu, Yu et al., 2022). This model system also allowed them to identify impaired function of the NA transporter (SLC6A2) in FD, which led to NA spillover and perpetuated symN hyperactivity (Wu, Yu et al., 2022). The following year, Wu, Huang et al. (2022) used hiPSC‐derived symNs to test whether the SNS is permissive to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Using SARS‐CoV‐2 mimicking pseudo virus, they found that human symNs were permissive to the virus, which caused symN hyperactivity in an inflammatory environment that simulated SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Their results may recapitulate the pathology of dysautonomia in SARS‐CoV‐2 patients during acute infection. Wu et al. (2023) treated symNs with high glucose to mimic diabetes‐induced hyperglycaemia. This model revealed high glucose induced hyperactivity and reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation in symNs, which mimicked the early pathology of diabetic autonomic neuropathy. Using this model, they discovered that the increased posttranslational modification O‐GlcNAcylation is responsible for symN hyperactivity. The same year, Wu et al. (2024) established the first parasymN differentiation protocol that was derived from SCPs. This enabled comprehensive assessment of both sympathetic and parasympathetic functions in FD. As a result, they found that FD parasymNs were also hyperactive in vitro, and the interaction between FD symNs and parasymNs was impaired. This may explain why FD patients’ symptoms and their response to drug treatments are so unpredictable. They also used the hiPSC‐derived parasymNs to study the vulnerability of parasymNs to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and found that the virus selectively infected hiPSC‐derived sensory neurons, but not parasymNs. Using hiPSC technology, these teams were able to specifically assess the disease‐based dysfunction of ANS neurons without the influence of other affected organs.

The heart

Cardiac function

The heart functions as a biological pump by continuously executing cycles of contraction and relaxation of the ventricular and atrial walls, to meet the body's ever‐changing metabolic needs (Wilson et al., 2022). The atrial and ventricular walls have three discernible layers; the thickest contractile layer, the myocardium, lies intermediary to the single‐celled inner endocardium and outer pericardium. At the epicentre of myocardial contractility are the cardiomyocytes (CMs), striated, branched and predominantly mononucleated muscle cells. Intercalated discs, housing gap junctions and desmosomes, interconnect CMs, facilitating mechanical and electrical conduction. CMs coalesce into highly aligned myocardial sheets, each measuring 100 µm thick. These anisotropic myocardial sheets stack with subtle angular offsets forming the myocardium (Wilson et al., 2022). In addition to the CM population, the myocardium harbours a consortium of other mesoderm‐derived cell lineages: cardiac fibroblasts, endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells (Brade et al., 2013).

Cardiac development

The heart originates from the posterior primitive streak during fetal development (Srivastava & Ivey, 2006). Activation of specific transcription factors characterizes differentiation of hiPSCs into CMs. T/Brachyury, which is activated by Wingless and Int‐1 signalling pathways (Wnts), bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) and the transforming growth factor β‐family member nodal, is expressed during the initiation of gastrulation and signals mesoderm formation from hiPSCs in the primitive streak. Mesoderm posterior 1 (Mesp‐1) regulates the expression of key cardiac transcription factors, Nkx2.5, Tbx5/20, Gata‐4, Mef2c and Hand1/2, promoting the specification of mesodermal cells into mesoderm precursors of the cardiovascular lineage/cardiac progenitors, while repressing genes associated with other mesodermal cell types (Roston et al., 2018; Skinner et al., 2019; Wallace et al., 2019). Cardiac progenitor cells undergo further differentiation prompted by Mesp‐1 into immature beating CMs, a process that involves the activation of genes coding for structural proteins, ion channels and sarcomere assembly (Roston et al., 2018). Immature CMs continue to mature and acquire functional characteristics, including organized sarcomeres, proper electrical signalling and contraction. Maturation in vivo is characterized by proteins including α‐actinin, α‐myosin heavy chain (α‐MHC) and Troponin‐T.

Cardiac dysfunction

Numerous genetic disorders relate to cardiac dysfunction via effects on the heart's electrical conduction, contraction and/or relaxation. Channelopathies, related to ion channel dysfunction, include LQTS, short QT syndrome (SQTS), catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT), and Brugada syndrome (BS), all known for their association with life‐threatening arrhythmias in children and young adults, triggered by ANS overdrive. LQTS, characterized by prolongation of the heart's repolarization phase (Kaizer et al., 2023), is caused by loss‐of‐function variants in genes such as KCNQ1 and KCNH2, which encode potassium channel subunits (thus reducing the outward potassium currents), and gain‐of function variants in SCN5A, which encodes a sodium channel subunit (thus increasing the inward sodium current) (Wallace et al., 2019). SQTS, characterized by a shortened QTc interval (<340 ms), peaked T waves and poor heart rate adaptation, is associated with genetic variants that either increase outward potassium flow (such as gain‐of‐function KCNQ1 and KCNH2 variants) or reduce inward calcium flow (Roston et al., 2018). BS, characterized by right bundle branch block with ST‐segment elevation (Juang & Horie, 2016), is caused predominantly by loss‐of‐function genetic variants in SCN5A (Juang & Horie, 2016). CPVT, characterized by dysfunction in calcium handling (Skinner et al., 2019), is caused by genetic variants in the RYR2 and CASQ2 genes, which code for ryanodine and calsequestrin (Roston et al., 2018). Cardiomyopathies include disorders related to structural and functional cardiac abnormalities associated with genetic variants in multiple genes, including MYH7, MYBPC3 and ACTN2 for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (Marian, 2021; Tudurachi et al., 2023), and TNNT2, LMNA, PLN and PLEKHM29 (Hirtle‐Lewis et al., 2013), as well as genes which code for desmosomal proteins, such as PKP2, JUP, DSC2, DSG2 and DSP10 (Higo, 2023; Liu, Zhang et al., 2023), for dilated cardiomyopathies. Moreover, non‐genetic factors can result in cardiac dysfunction, such as cardiac fibrosis following myocardial infarction, attributed to activation of the extracellular matrix producing cardiac fibroblasts, causing changes in the distensibility and contractility of the heart (Fu et al., 2020; Iseoka et al., 2021).

Cardiac disease modelling using hiPSCs

hiPSC‐based CM differentiation has evolved since the discovery of hESC‐derived embryoid body formation by Kehat et al. (2001). The differentiation of hiPSCs into CMs comprises four essential stages: mesoderm formation, mesoderm patterning towards cardiogenic mesoderm, cardiac mesoderm/cardiac progenitor formation and early CM maturation. During the last decade, many groups have used variations of a monolayer‐based approach modulating the Wnt/β‐catenin pathway in a growth factor‐free system (GiWi protocol) (Lian et al., 2013) to induce CM differentiation passing through those four stages. The protocol applies glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) inhibitors to hiPSCs, inducing mesoderm specification, followed by Wnt signalling inhibition generating cardiac mesoderm. Cardiac mesoderm cells spontaneously develop into contracting immature CMs when cultured in RPMI/B27 medium (Laflamme et al., 2007; Lian et al., 2013; Lyra‐Leite et al., 2022; Paige et al., 2010) due to the presence of the hyperpolarizing ‘funny’ current (If). The GiWi protocol produces a mixture of CM subtypes, primarily ventricular CMs (Lyra‐Leite et al., 2022). Other studies modified this protocol producing primarily atrial or nodal CMs (Ahmad et al., 2023; Brown et al., 2024; Lee et al., 2017; Liang et al., 2020; Ren et al., 2019; Thorpe et al., 2023). Higher yields of atrial CMs were achieved with the addition of retinoic acid during cardiac mesoderm formation until full CM differentiation (Ahmad et al., 2023; Brown et al., 2024; Lee et al., 2017; Thorpe et al., 2023). Wnt activation during the cardiac precursor stages using CHIR99021 achieved higher yields of nodal pacemaker CMs (Liang et al., 2020; Ren et al., 2019).

Electrophysiologically, hiPSC‐CMs generate cardiac ion currents that resemble those of human CMs in vivo, which include sodium (INa), calcium (ICaL and ICaT), and potassium (IKs and IKr) ion channels (Dhamoon & Jalife, 2005; Hoekstra et al., 2012; Juang & Horie, 2016). However, the presence of IK1, a potassium ion channel that regulates the stabilization of resting membrane potential (Doss et al., 2012), has not yet been documented, indicating that hiPSC‐CMs are not fully mature. To compensate for the missing IK1 channel, hiPSC‐CMs rely on the IKr channel for regulating and stabilizing the membrane potential (Doss et al., 2012).

Moretti et al. (2010) pioneered cardiac disease modelling by utilizing hiPSC‐CMs with a KCNQ1 gene variant to replicate the LQT1 phenotype, characterized by a prolonged cardiac action potential and reduced delayed rectifier potassium current (IKs). Subsequent studies furthered these techniques, using hiPSC‐CMs with KCNH2 gene variants re‐creating the LQT2 phenotype, which exhibits a prolonged cardiac action potential, increased afterdepolarization frequency and reduced rapid rectifier potassium current (IKr) (Itzhaki et al., 2011; Matsa et al., 2011; Shah et al., 2020). The LQT3 phenotype was re‐created using hiPSC‐CMs with SCN5A gene variants causing an increase in the depolarizing sodium current (INa) (Penttinen et al., 2023; Sun et al., 2023). Researchers have recapitulated the CPVT phenotype, characterized by abnormal calcium handling, in hiPSC‐CMs with genetic variants in RyR2 (CPVT1) and CASQ2 (CPVT2). Calcium‐imaging techniques revealed increased adrenergic‐induced calcium concentrations, higher frequencies of calcium sparks and arrhythmogenic membrane potentials (Arslanova et al., 2021; Polonen et al., 2020). These studies confirmed that sympathetically triggered arrhythmias in CPVT result from abnormal calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum through the ryanodine channel complex during diastole (Novak et al., 2015). Additional studies have replicated cardiomyopathy disorders using hiPSC‐CMs; hiPSC‐CMs with MYH7, ACTN2 or MYBPC3 gene variants replicated hypertrophic cardiomyopathy phenotypes. Models showed abnormal sarcomere arrangement and electrophysiological irregularities (Escriba et al., 2023; Han et al., 2014; Mosqueira et al., 2018; Prondzynski et al., 2019). hiPSC‐CMs with TNNT2, PKP2, PLEKHM2 and PLN gene variants replicated dilated cardiomyopathy (Cuello et al., 2021; Dai et al., 2020; Flenner et al., 2021; Higo, 2023; Korover et al., 2023). These studies showed protein deficiencies related to contraction–relaxation coupling and intracellular calcium signalling: α‐MHC, Troponin and calsequestrin.

Complex cardiac models using hiPSCs

2D monolayer hiPSC‐CM disease models with variant genes have been shown to replicate the hallmarks of their respective diseases. These simplistic models allow researchers to look at the underlying CM dysfunction but are limited compared to in vivo tissue as they lack complex 3D structure and crosstalk between multiple cell types. Additionally, hiPSC‐derived CMs produce immature ‘fetal‐like’ CMs, limiting the comparisons that can be made to in vivo cardiac tissue. Recent bioengineering approaches have added complexity to these hiPSC‐CM models, to produce more mature models that more closely reflect the structure and cellular composition of in vivo myocardium.

Non‐scaffolded 3D culture techniques

Non‐scaffolded 3D cardiac organoids can be assembled through cell aggregates such as embryoid bodies (EBs) or cardiac spheroids. The aggregates are formed by suspending cells in hanging drops in a rotating suspension culture, in non‐adhesive holds or low attachment plates (Beauchamp et al., 2020; Forghani et al., 2024; Ravenscroft et al., 2016; Varzideh et al., 2019). EBs, which are 3D aggregates of hiPSCs that can be differentiated into 3D cardiac tissue, have the advantage that they can self‐organize and can recapitulate complex structures that are difficult to form in 2D cultures, such as heart chambers and spatial specification. By inducing the EBs into early embryonic cell fate, the organoids can even be differentiated into multi‐organ structures. Most notably, the Aguirre group formed human heart organoids using a modified version of the GiWi protocol, with the addition of CHIR99021 for 1 h at day 7; these organoids consisted of cells of both CM and cardiac fibroblast lineage, as well as developing internal myocardial cavities. Other groups have formed cardiac spheroids from monolayer differentiated hiPSCs, using only cardiomyocytes (Paz‐Artigas et al., 2024) or cardiac cocultures (Beauchamp et al., 2020; Kahn‐Krell et al., 2022).

Scaffolded 3D culture techniques

Another approach to achieve 3D cultures is by encapsulating cells within 3D hydrogels, where biological hydrogels are preferable as they naturally have cell attachment sites. Biological polymers used in hydrogel formation include gelatin methacryol (GelMA) (Chalard et al., 2022; Feric et al., 2019), fibrin (Navaee et al., 2023; Prondzynski et al., 2019) or collagen (Cashman et al., 2016). These hydrogels act as a scaffold for the cells in 3D, and Zimmerman et al. (2002) were the first to create 3D scaffolded cardiac organoids, encapsulating neonatal rat CMs in fibrin gels. Crosslinkable hydrogels undergo a crosslinking phase in which an initiator covalently bonds adjacent polymer chains together, in response to some stimulus, forming a stable hydrogel. The most well‐used crosslinking method involves the use of light and potentiators. Photo‐crosslinkable hydrogels allow for the formation of complex structures through 3D bioprinting applications (Chen et al., 2020; Koti et al., 2019) or digital light processing (Chin et al., 2022; DePalma et al., 2021; Goodarzi Hosseinabadi et al., 2024). It was found that hiPSC‐CMs derived in 2D monolayers and encapsulated in 3D hydrogels had greater organization and development of sarcomere structures and related contractile proteins than hiPSC‐CMs kept in 2D monolayers after 50 days (Ergir et al., 2022). Crosslinkable hydrogels also allow researchers to control the mechanical properties of the tissue, and several studies have shown the benefits in differentiating hiPSCs into CMs on softer hydrogels and found that 9–10 kPa was the optimal stiffness for cardiomyocyte differentiation (DePalma et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2018).

Cardiac maturation through electro‐mechanical stimulation

Researchers have experimented with techniques to produce hiPSC‐CMs that display more adult‐like phenotypes. Research has predominately used external electrical and mechanical stimulation to induce fetal‐to adult phenotype changes. These factors in vivo are initiated early during cardiac embryogenesis (Puente et al., 2014). Electrical stimulation is applied by creating an electric field between two electrodes on either side of the cardiac tissue submerged in a conductive cell medium. Different pacing strategies have been applied including 1 Hz pulse waves (Ergir et al., 2022; Puente et al., 2014) and a stepwise pulse frequency increase from 1 to 6 Hz over 7 days. All this showed improvements in intercalated disc formation, gap junction expression and cell alignment. Mechanical stimulus can be added, through the inclusion of flexible posts or wires at each end of the tissue, connected to a rigid object (Ergir et al., 2022; Feric et al., 2019; Puente et al., 2014). This gives the cardiomyocytes something to contract against, allowing them to apply tension to the myofibrils. The effects of mechanical stimulation showed an increase in the maturation markers, namely an increase in intercalated disc structures, an increase in proteins associated with cardiac force transmission, desmosomes/ adherents, and an increase in myofibril alignment. Combining mechanical and electrical stimulation has shown to be the best procedure to produce CMs with the most adult‐like phenotypes. Biowire 2, created by the Radisic group (Feric et al., 2019), has been the best strategy for hiPSC‐CM maturation so far. hiPSC‐CMs were subjected to combined cyclical stretch from PoMAC wires on either side of the tissue and a supraphysiological pacing regimen of 2 weeks, increasing pulse frequency from 1 to 6 Hz, which resulted in these cells displaying adult‐like features not previously reported, such as a vast network of T‐tubules, inotropic response to isoproterenol and a positive force frequency response. Although cardiac models have seen an increase in complexity and translation to their in vivo counterparts, hiPSC‐CM models are still significantly far from clinical applications.

Cardiac maturation using microfluidic devices

Microfluidic devices/heart on a chip is a recent innovation used to aid in the differentiation and maturation of hiPSC‐CMs. Microfluidic devices are bioengineered cell culture systems that contain multiple tissue culture compartments in a 2D format usually made using stereolithography (Qian et al., 2015). This culture design allows spatial and temporal control of cell distribution and microenvironment (Kamande et al., 2019). The GiWi differentiation protocol was altered using a microfluidic device to deliver transcription factors GATA4, NKX2.5, MEF2C, TBX3 and TBX5. Their protocol showed CMs with higher expression of TNNT2 and MYH7 (Contato et al., 2022). Other studies have used microfluidic devices to increase maturation of hiPSC‐CMs using driven fluid flow to simulate in vivo conditions. Under constant fluid flow conditions, CMs showed greater alignment (Esparza et al., 2023), while under cyclical pulsatile flow, CMs had greater alignment, contractility and sarcomere length (Kolanowski et al., 2020). Microfluidic devices can also be used to simulate hypoxic conditions for disease modelling (Kobuszewska et al., 2020; Morshed & Dutta, 2017)

Cocultures including non‐cardiomyocyte cardiac cells

Coculture models combine CMs with other common cardiac cells such as cardiac fibroblasts and cardiac endothelial cells, and have been used to construct, for example, cardiac organoids which show increased electrical propagation and contractility in the CMs (Aalders et al., 2024; Brown et al., 2024; Giacomelli et al., 2020; Ravenscroft et al., 2016; Varzideh et al., 2019). Notable studies that have shown the role of non‐CMs in cardiac disease include Richards et al. (2020) which combined hiPSC‐CMs, human cardiac ventricular fibroblasts, human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and human adipose‐derived stem cells (hADSCs) to fabricate cardiac organoids. By stressing the organoids with low oxygen and NA treatment to mimic symN activation, they modelled the features of myocardial infarction, such as cardiac cell death, scar tissue formation and impaired calcium handling ability. Giacomelli et al. (2020) and Aalders et al. (2024) used hiPSC cardiac coculture models including stromal cells and cardiac fibroblasts to show the role of non‐CMs in cardiomyopathy.

Further developments in complex hiPSC‐based models including 3D structures, coculturing with non‐cardiomyocyte cardiac cells and strategies to functionally maturate the derived hiPSC‐CMs show promise to more accurately model the complex cardiac physiology in health and disease.

Cardiac regulation by the ANS and related diseases

Upon activation of the SNS, the neurotransmitter NA is released by sympathetic postganglionic fibres and binds to β‐1 adrenergic receptors that are expressed on the sinoatrial node, atrioventricular node and CMs (Gordan et al., 2015; Silvani et al., 2016). The symN release of NA triggers a signalling cascade of proteins and enzymes to activate adenylyl cyclase and increase intracellular cAMP in the CMs (Gordan et al., 2015). cAMP activates protein kinase A (PKA), an enzyme that phosphorylates Ca2+ cycling proteins in CMs (Bers & Despa, 2009). Phosphorylation and opening of the L‐type Ca2+ channel allows Ca2+ entry into the cytosol where intracellular Ca2+ concentration increases and induces Ca2+‐induced Ca2+ release (Bers & Despa, 2009; Dewenter et al., 2017). Phospholamban, phosphorylated by PKA, increases the pump rate of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) for efficient Ca2+ handling, and activates the Ca2+ release channels (ryanodine receptors) on the SR membrane to release Ca2+ (Bers & Despa, 2009; Dewenter et al., 2017; DiFrancesco & Tortora, 1991). The activation of adenylyl cyclase and cAMP shifts the voltage dependence of the inward ‘funny’ current, a pacemaker current that is activated by hyperpolarization of the voltage membrane (Bers & Despa, 2009). The ‘funny’ current depolarizes the membrane during diastolic depolarization, as the outflow of Ca2+ ions decreases and K+ outflow increases, all of which increases heart rate and contractility (Dewenter et al., 2017; DiFrancesco & Tortora, 1991; DiFrancesco & Noble, 2012).

Moreover, colocalized with NA in most sympathetic nerve terminals is the cotransmitter neuropeptide Y (NPY). NPY produces vasoconstriction, prejunctional inhibition of NA release and postjunctional potentiation of NA effects (Tan et al., 2018). During pathophysiological states of sympathetic hyperactivity, NPY promotes arrhythmogenesis via ventricular CM receptors, and the NPY signalling cascade thus represents a promising anti‐arrhythmic target (Ajijola et al., 2020; Kalla et al., 2020).

In contrast, activation of the PSNS has an opposing effect on the heart. PSNS innervation derives from the nucleus ambiguous of the medulla oblongata and predominately acts via the 10th cranial nerve, known as the vagus nerve (Hopkins et al., 1996; Manolis et al., 2021). PSNS preganglionic neurons project through the vagus nerve to the epicardial ganglionated plexus that innervates the heart and transmits signals to the postganglionic parasympathetic fibres (Gordan et al., 2015; Hopkins et al., 1996; Silvani et al., 2016). The PSNS postganglionic fibres release the neurotransmitter ACh that binds to M2 muscarinic receptors in the heart (DiFrancesco et al., 1989; Krapivinsky et al., 1995). ACh acts to decrease intracellular levels of cAMP and inhibits the activation of PKA, reducing Ca2+ handling and Ca2+ release by the SR and ryanodine receptors (Bers & Despa, 2009; Gordan et al., 2015; Silvani et al., 2016). ACh binding to M2 receptors opens muscarinic K+ channels, increasing K+ release, and initiates a hyperpolarizing current that opposes the depolarizing ‘funny’ current, effectively reducing heart rate and contractility (DiFrancesco et al., 1989; Krapivinsky et al., 1995).

The ANS has a direct impact on cardiac electrophysiology by the action of the SNS and PSNS on cardiac automaticity and conductibility of CMs. Under normal conditions, the two opposing systems work in conjunction to maintain cardiac homeostasis. However, the ANS can become dysregulated, which can have serious complications on the heart and lead to adverse cardiac events such as cardiac arrythmias, myocardial infarction, heart failure, atrial and ventricular fibrillation, bradycardia and tachycardia, and sudden cardiac death (Davis & Natelson, 1993; La Rovere et al., 2020). Cardiac diseases associated with an imbalance or dysfunction of the ANS are known as neurocardiac diseases, as they encompass the brain–heart connection. The ANS is regulated by specific regions of the brain (the nucleus of the solitary tract, rostroventrolateral medulla, insula cortex, prefrontal cortex, hypothalamus, amygdala, anterior cingulate cortex and brainstem) (Prasad Hrishi et al., 2019). Therefore, neurological conditions such as stroke, epilepsy, chronic psychological stress and lesions in these areas of the brain can also result in ANS imbalance and adverse cardiac outcomes (Pereira et al., 2013; Prasad Hrishi et al., 2019).

ANS imbalance can manifest as sympathetic overdrive or parasympathetic overdrive. SNS activity is considered to be pro‐arrhythmic and PSNS activity as anti‐arrhythmic (Shen & Zipes, 2014), but this is not an absolute rule. Sympathetic overdrive is a causative factor for fatal ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death following myocardial infarction (La Rovere et al., 1998). Moreover, sympathetic overdrive contributes to the pathophysiology of congestive heart failure (Tomaselli & Zipes, 2004), as well as polymorphic ventricular fibrillation and sudden cardiac death in LQTS (Zipes, 1991) and CPVT (Leenhardt et al., 1995). However, in the case of BS (Takigawa et al., 2008) and idiopathic ventricular fibrillation/J‐wave syndrome (Mizumaki et al., 2012), these are both associated with ventricular fibrillation and sudden cardiac death in response to vagal/PSNS overdrive (Manolis et al., 2021; Shen & Zipes, 2014).

hiPSC neuron‐cardiomyocyte cocultures and their potential for neurocardiac disease modelling

To better understand neurocardiac disease, studies of neuron–CM interactions in human‐derived cocultures, as compared to studies exposing monocultured CMs to sympathomimetic or parasympathomimetic drugs, are key. This is an emerging avenue of disease modelling, particularly in the development of functional hiPSC‐CMs/hiPSC‐neuron cocultures. The first advancements were made by Oh et al. (2016), successfully developing NA‐secreting hESC‐derived symNs that could functionally couple with neonatal rat ventricular CMs. Winbo et al. (2020) successfully developed functional cocultures of NA‐secreting hiPSC‐derived symNs and hiPSC‐CMs, demonstrating that hiPSC‐symNs could modulate hiPSC‐CM beating rate, as well as augment symN maturation and development. Earlier the same year, Takayama et al. (2020) had developed sympathetic‐like and parasympathetic‐like neurons that could modulate hiPSC‐CM beating rate in an antagonistic manner, recapitulating the ANS regulation of heart rate, albeit using cells that did not secrete detectable levels of NA or ACh. Since then, several studies on the neurocardiac connection using 2D or 3D coculturing techniques have been published (brief description and main findings summarized in Table 1) (Bernardin et al., 2022; Hakli et al., 2022; Li, Edel et al., 2023; Narkar et al., 2022; Oh et al., 2016; Takayama et al., 2020; Winbo et al., 2020). Moreover, in their FD research in 2022 (Wu, Yu et al., 2022) and 2024 (Wu et al., 2024), Wu and colleagues cocultured FD symNs (Wu, Yu et al., 2022) and parasymNs (Wu et al., 2024) with hiPSC‐derived CMs in 2D. They found that hyperactive FD symNs and parasymNs were able to upregulate and downregulate CM beating, respectively. Collectively, this important work will enable meaningful neurocardiac disease modelling, ideally including both branches of the ANS, in the near future.

Table 1.

Neurocardiac in vitro models of brain–heart connection including hiPSCs

| Model | Brief description | Main findings | Journal | Author |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D coculture | hiPSC‐symNs cocultured with neonatal mouse ventricular myocytes (NMVMs) and hiPSC‐CMs | Activated NA‐secreting hESC‐SNs modulated the beating rate and contractility of NMVMs (but not hiPSC‐CMs). Coculture enhanced SN maturation | Cell Stem Cell | (Oh et al., 2016) |

| 2D coculture | Sympathetic‐like and parasympathetic‐like neurons cocultured with hiPSC‐CMs | Induced sympathetic‐like and parasympathetic‐like neurons modulated the beating rate of hiPSC‐CMs in an antagonistic manner. No NA or ACh was detected in the cultures | Scientific Reports | (Takayama et al., 2020) |

| 2D co‐culture | hiPSC‐symNs cocultured with hiPSC‐CMs | Nicotinic activation of NA‐secreting hiPSC‐symNs increased the beating rate of cocultured (but not monocultured) hiPSC‐CMs. Coculture improved hiPSC‐SN action potential kinetics and maturation | American Journal of Physiology | (Winbo et al., 2020) |

| 2D coculture | hiPSC‐motor neurons cocultured with hiPSC‐CMs | In coculture beating rate of hiPSC‐CMs increased but contractility decreased in response to nicotinic activation of NA‐secreting hiPSC‐neurons | Physiological Reports | (Narkar et al., 2022) |

| 2D coculture | hiPSC‐symNs cocultured with hiPSC‐CMs | In coculture, CM beating rate increased upon nicotine treatment, or when cocultured with FD symNs that are hyperactive | Nature Communications | (Wu et al., 2022) |

| 2D coculture | hiPSC‐symNs cocultured with hiPSC‐CMs | hiPSC‐SNs formed varicosities with axons surrounding hiPSC‐CMs, indicating formation of neurocardiac junctions. cAMP increased in cocultured (but not monocultured) hiPSC‐CMs in response to adenyl cyclase | Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B | (Li, Edel et al., 2023) |

| 2D coculture | hiPSC‐parasymNs cocultured with hiPSC‐CMs | In coculture, CM beating rate decreased upon nicotine/blue light (with optogenetic parasymN‐ChR2) treatment, or when cocultured with FD parasymNs that are hyperactive | Cell Stem Cell | (Wu et al., 2024) |

| 3D coculture (microfluidic chip) | hiPSC‐neurons and hiPSC‐CMs cultured separately, with neurocardiac connection allowed via microtunnels by transverse neuronal axons | Positive gene expression for functional connection between neuronal axons and hiPSC‐CMs; CHRM2 and CHAT (cholinergic signalling via M2 receptors in hiPSC‐CMs) | International Journal of Molecular Sciences | (Häkli et al., 2022) |

| 3D coculture (microfluidic organ‐on‐a‐chip) | Rat PC12 neurons differentiated into sympathetic‐like neurons and hiPSC‐CMs, and hiPSC‐SNs and hiPSC‐CMs, cultured separately with neurocardiac connection allowed via microtunnels by transverse neuronal axons | Rat sympathetic‐like neuronal synapses with hiPSC‐CMs expressed synapsin‐1 and β3‐tubulin indicating the formation of neurocardiac‐junction‐like structures. PC12 neurons modulated Ca2+ release in hiPSC‐CMs but did not affect hiPSC‐CM contractility. hiPSC‐SNs extended into the hiPSC‐SN compartment via microtunnels | Cells | (Bernardin et al., 2022) |

Limitations to hiPSC modelling, potential solutions and conclusions

Although hiPSC technology has demonstrated great promise as a human model system in neurocardiac research, there are limitations and research hurdles that need to be overcome.

(1) Variability. In vitro differentiation protocols are highly precise systems that scientists design to mimic the intricate developmental microenvironment in the body. Hence, the quality and activity of small molecules and growth factors used in the protocols can determine the success of the differentiation. For success and for minimization of variability between experiments, it is crucial to document the detailed methodology of differentiation protocols and to use the exact materials to perform and reproduce experiments. In addition, phenotypic variability among different hiPSC lines also raises concerns, since it would significantly hamper the reproducibility and therapeutic development. Epigenetic and genetic regulation seem to play critical roles underlying the line‐to‐line variability (Ortmann et al., 2020). To reduce phenotypic variability, it is highly recommended to use multiple well‐characterized hiPSC lines and isogenic iPSC lines to confirm the phenotypes. During hiPSC maintenance, it is critical to passage the colonies at the proper stage to prevent undesired differentiation. Furthermore, karyotypic testing of the hiPSC lines should also be done regularly.

(2) Differentiation efficiency. It is nearly impossible to generate cell cultures of a differentiated cell type of interest without any mis‐differentiated contaminating cell types; for example, symN cultures might contain ectodermal placode and smooth muscle cells (Wu, Yu et al., 2022; Zeltner et al., 2016). One reason for this is that many cell types share the same progenitor; for example, symNs and sensory neurons both derive from NCCs. Nevertheless, it is critical to minimize contaminating cells within the cultures in order to obtain truthful disease modelling results. Methods to enhance differentiation efficiency include: (i) binary lineage inhibition in conjunction with the differentiation process – for example, when differentiating mesodermal lineages, inhibitors for endodermal lineages should also be given, to ensure the specificity (Loh et al., 2016); (ii) addition of cell cycle inhibitors to kill proliferating cells (Wu, Yu et al., 2022); and (iii) cell sorting strategies can be used to purify cultures.

(3) Maturity. First, to properly assess the maturity of electrically active hiPSC‐derived peripheral neurons and CMs, thorough functional characterization studies are necessary, including modalities such as whole‐cell patch clamp and calcium imaging, and (for neurons) measurements of neurotransmitters produced. This is key as a major hurdle in the field is that differentiated cells are not as mature as the actual tissue in vivo (Saito‐Diaz & Zeltner, 2019). Common solutions to increase cellular maturity include prolonged culture periods (Paavilainen et al., 2018; Winbo et al., 2020), engraftment of hiPSC‐derived tissue into animal vessels, where the in vivo environment aids the maturation (Revah et al., 2022), small molecule treatments that better mimic the natural metabolomic state, epigenetic modification and ion channel activation (Ciceri et al., 2024; Hergenreder et al., 2024). Using multiplex organoid cultures instead of 2D cultures (Lee et al., 2020; Richards et al., 2016). For electrically active cell types, such as neurons and CMs, electrical stimulation has been shown to improve their structural and functional maturation (Ma et al., 2018; Richards et al., 2016; Yoshida et al., 2019). Current studies also show that tissue maturity can be improved using compartmental microfluidic devices with proper extracellular matrix, which resemble spatial and microenvironmental supports in vivo (Cho et al., 2021; Kamande et al., 2019). Finally, several studies have shown that functional coculture systems, for example between neurons and their target tissues, provide reciprocal maturation effects (Kowalski et al., 2022; Oh et al., 2016). It is worth mentioning that the maturation strategy may be cell type dependent. For instance, CM maturation relies mainly on fatty acid availability and PPAR‐mediated metabolic switch (Kim, Yoon et al., 2022; Miao et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2023). Although combined strategies might be available (Hergenreder et al., 2024), it is crucial to identify the most ideal methods to achieve the best results.

(4) Cellular diversity. The power of hiPSC‐based disease modelling is limited by the availability of differentiation protocols for a specific cell type. For instance, ANS disorders typically involve both SNS and PSNS, yet there are few reports of protocols for the derivation of parasymNs, compared to symN protocols (Goldsteen et al., 2022; Takayama et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2024).

(5) Complexity. For some applications, such as drug screening, having pure cultures of one cell type is ideal, but for other applications diversity of cell types within a tissue is necessary. Moreover, most models of neurocardiac networks are 2D cocultures of symNs and cardiomyocytes. They lack delicate heart structures, such as atrial–ventricular patterning, heart cavities and the involvement of parasymNs. 3D cardiac organoid models therefore may address this need (Kim, Kamm et al., 2022; Tang et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2021). However, despite the advances in structure and histological structure, current organoid models are far from physiological organ representations. Nevertheless, in the future, it would be helpful to create a 3D heart organoid with integrated ANS circuitry to gain deeper insights into ANS‐mediated cardiovascular regulation.

Overall, the powerful hiPSC technology has great promise as an addition that will bring significant impact to the field of neurocardiology research in the near future.

Additional information

Competing interests

All authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Author contributions

H.F.W., C.H. and H.P. designed and wrote the manuscript. A.W. and N.Z. supervised and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and that all persons designated as authors qualify for authorship, and all those who qualify for authorship are listed.

Funding

This work was supported by 1R01NS114567‐01A1 to N.Z. and the Health Research Council of New Zealand (HRC Reference 21/380). CH was funded by the Hugh Green Foundation, New Zealand.

Supporting information

Peer Review History

Biography

Hsueh‐Fu is a PhD student in the Zeltner lab. He has initiated and led this review article together with Charlotte Hamilton and Harrison Porritt (three co‐authors) from the Winbo lab. Hsueh Fu was born in Taiwan, where he received a Master's degree, he then moved to the USA to complete his PhD. His research interest lies in addressing neurological disorders and injuries via cutting‐edge techniques and interdisciplinary approaches. Hsueh Fu graduated in May 2024, with his work focusing on modelling stress‐related hyperactivity phenotypes in the sympathetic nervous system in familial dysautonomia.

Handling Editors: Harold Schultz & David Paterson

The peer review history is available in the Supporting Information section of this article (https://doi.org/10.1113/JP286416#support‐information‐section).

H.Wu, C. Hamilton and H. Porritt, first co‐authorship.

Contributor Information

Annika Winbo, Email: a.winbo@auckland.ac.nz.

Nadja Zeltner, Email: nadja.zeltner@uga.edu.

References

- Aalders, J. , Léger, L. , van der Meeren, L. , Sinha, S. , Skirtach, A G. , De Backer, J. , & van Hengel, J. (2024). Three‐dimensional co‐culturing of stem cell‐derived cardiomyocytes and cardiac fibroblasts reveals a role for both cell types in Marfan‐related cardiomyopathy. Matrix Biology, 126, 14–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, F. S. , Jin, Y. , Grassam‐Rowe, A. , Zhou, Y. , Yuan, M. , Fan, X. , Zhou, R. , Mu‐U‐Min, R. , O'shea, C. , Ibrahim, A M. , Hyder, W. , Aguib, Y. , Yacoub, M. , Pavlovic, D. , Zhang, Y. , Tan, X. , Lei, M. , & Terrar, D. A. (2023). Generation of cardiomyocytes from human‐induced pluripotent stem cells resembling atrial cells with ability to respond to adrenoceptor agonists. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London‐Series B: Biological Sciences, 378(1879), 20220312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajijola, O. A. , Chatterjee, N. A. , Gonzales, M. J. , Gornbein, J. , Liu, K. , Li, D. , Paterson, D. J. , Shivkumar, K. , Singh, J. P. , & Herring, N. (2020). Coronary sinus neuropeptide Y levels and adverse outcomes in patients with stable chronic heart failure. Journal of the American Medical Association Cardiology, 5(3), 318–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arslanova, A. , Shafaattalab, S. , Ye, K. , Asghari, P. , Lin, L. , Kim, B. , Roston, T. M. , Hove‐Madsen, L. , Van Petegem, F. , Sanatani, S. , Moore, E. , Lynn, F. , Søndergaard, M. , Luo, Y. , Chen, S. R. W. , & Tibbits, G. F. (2021). Using hiPSC‐CMs to examine mechanisms of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Current Protocol, 1(12), e320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avior, Y. , Sagi, I. , & Benvenisty, N. (2016). Pluripotent stem cells in disease modelling and drug discovery. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 17(3), 170–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod, F. B. (2004). Familial dysautonomia. Muscle & Nerve, 29(3), 352–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bairey Merz, C. N. , Elboudwarej, O. , & Mehta, P. (2015). The autonomic nervous system and cardiovascular health and disease: A complex balancing act. Journal of the American College of Cardiology Heart Fail, 3(5), 383–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar‐Aluma, B. E. (1993). Familial dysautonomia. In Adam M. P., Everman D. B., Mirzaa G. M., Pagon R. A., Wallace S. E., Bean L. J. H., Gripp K. W. & Amemiya A. (Eds), GeneReviews((R)), Seattle (WA): NCBI Bookshelf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp, P. , Jackson, C. B. , Ozhathil, L. C. , Agarkova, I. , Galindo, C. L. , Sawyer, D. B. , Suter, T. M. , & Zuppinger, C. (2020). 3D co‐culture of hiPSC‐derived cardiomyocytes with cardiac fibroblasts improves tissue‐like features of cardiac spheroids. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, 7, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardin, A. A. , Colombani, S. , Rousselot, A. , Andry, V. , Goumon, Y. , Delanoe‐Ayari, H. , Pasqualin, C. , Brugg, B. , Jacotot, E. D. , Pasquie, J. L. , Lacampagne, A. , & Meli, A. C. (2022). Impact of neurons on patient‐derived cardiomyocytes using organ‐on‐a‐chip and iPSC biotechnologies. Cells, 11, 11233764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bers, D. M. , & Despa, S. (2009). Na/K‐ATPase–an integral player in the adrenergic fight‐or‐flight response. Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine, 19(4), 111–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brade, T. , Pane, L. S. , Moretti, A. , Chien, K. R. , & Laugwitz, K.‐L. (2013). Embryonic heart progenitors and cardiogenesis. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine, 3(10), a013847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennand, K. J. , Simone, A. , Jou, J. , Gelboin‐Burkhart, C. , Tran, N. , Sangar, S. , Li, Y. , Mu, Y. , Chen, G. , Yu, D. , Mccarthy, S. , Sebat, J. , & Gage, F. H. (2011). Modelling schizophrenia using human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature, 473(7346), 221–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G. E. , Han, Y. D. , Michell, A. R. , Ly, O. T. , Vanoye, C. G. , Spanghero, E. , George, A. L. , Darbar, D. , & Khetani, S. R. (2024). Engineered cocultures of iPSC‐derived atrial cardiomyocytes and atrial fibroblasts for modeling atrial fibrillation. Science Advances, 10(3), eadg1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buijs, R. M. (2013). The autonomic nervous system: a balancing act. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 117, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashman, T. J. , Josowitz, R. , Johnson, B. V. , Gelb, B. D. , & Costa, K. D. (2016). Human engineered cardiac tissues created using induced pluripotent stem cells reveal functional characteristics of BRAF‐mediated hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. PLoS ONE, 11(1), e0146697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalard, A. E. , Dixon, A. W. , Taberner, A. J. , & Malmström, J. (2022). Visible‐light stiffness patterning of GelMA hydrogels towards in vitro scar tissue models. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 10, 946754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. , Zhang, J. , Liu, X. , Wang, S. , Tao, J. , Huang, Y. , Wu, W. , Li, Y. , Zhou, K. , Wei, X. , Chen, S. , Li, X. , Xu, X. , Cardon, L. , Qian, Z. , & Gou, M. (2020). Noninvasive in vivo 3D bioprinting. Science Advances, 6(23), eaba7406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin, I. L. , Hool, L. , & Choi, Y. S. (2022). Correction: Interrogating cardiac muscle cell mechanobiology on stiffness gradient hydrogels. Biomaterials Science, 10(22), 6628–6629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho, A.‐N. , Jin, Y. , An, Y. , Kim, J. , Choi, Y. S. , Lee, J. S. , Kim, J. , Choi, W.‐Y. , Koo, D.‐J. , Yu, W. , Chang, G.‐E. , Kim, D.‐Y. , Jo, S.‐H. , Kim, J. , Kim, S.‐Y. , Kim, Y.‐G. , Kim, J. Y. , Choi, N. , Cheong, E. , … Cho, S.‐W. (2021). Microfluidic device with brain extracellular matrix promotes structural and functional maturation of human brain organoids. Nature Communications, 12(1), 4730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciceri, G. , Baggiolini, A. , Cho, H. S. , Kshirsagar, M. , Benito‐Kwiecinski, S. , Walsh, R. M. , Aromolaran, K. A. , Gonzalez‐Hernandez, A. J. , Munguba, H. , Koo, S. Y. , Xu, N. , Sevilla, K. J. , Goldstein, P. A. , Levitz, J. , Leslie, C. S. , Koche, R. P. , & Studer, L. (2024). An epigenetic barrier sets the timing of human neuronal maturation. Nature, 626(8000), 881–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cieślar‐Pobuda, A. , Knoflach, V. , Ringh, M. V. , Stark, J. , Likus, W. , Siemianowicz, K. , Ghavami, S. , Hudecki, A. , Green, J. L. , & Łos, M. J. (2017). Transdifferentiation and reprogramming: Overview of the processes, their similarities and differences. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) ‐ Molecular Cell Research, 1864(7), 1359–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contato, A. , Gagliano, O. , Magnussen, M. , Giomo, M. , & Elvassore, N. (2022). Timely delivery of cardiac mmRNAs in microfluidics enhances cardiogenic programming of human pluripotent stem cells. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 10, 871867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuello, F. , Knaust, A. E. , Saleem, U. , Loos, M. , Raabe, J. , Mosqueira, D. , Laufer, S. , Schweizer, M. , van der Kraak, P. , Flenner, F. , Ulmer, B. M. , Braren, I. , Yin, X. , Theofilatos, K. , Ruiz‐Orera, J. , Patone, G. , Klampe, B. , Schulze, T. , Piasecki, A. , … Hansen, A. (2021). Impairment of the ER/mitochondria compartment in human cardiomyocytes with PLN p.Arg14del mutation. European Molecular Biology Organization Molecular Medicine, 13(6), e13074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cykowski, M. D. , Coon, E. A. , Powell, S. Z. , Jenkins, S. M. , Benarroch, E. E. , Low, P. A. , Schmeichel, A. M. , & Parisi, J. E. (2015). Expanding the spectrum of neuronal pathology in multiple system atrophy. Brain, 138(8), 2293–2309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Y. , Amenov, A. , Ignatyeva, N. , Koschinski, A. , Xu, H. , Soong, P. L. , Tiburcy, M. , Linke, W. A. , Zaccolo, M. , Hasenfuss, G. , Zimmermann, W.‐H. , & Ebert, A. (2020). Troponin destabilization impairs sarcomere‐cytoskeleton interactions in iPSC‐derived cardiomyocytes from dilated cardiomyopathy patients. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani, M. , Dirksen, A. , Taraborrelli, P. , Torocastro, M. , Panagopoulos, D. , Sutton, R. , & Lim, P. B. (2021). Autonomic dysfunction in ‘long COVID’: Rationale, physiology and management strategies. Clinical Medicine (London), 21(1), e63‐e67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, A. M. , & Natelson, B. H. (1993). Brain‐heart interactions. The neurocardiology of arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death. Texas Heart Institute Journal, 20, 158–169. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng, W. (2010). Induced pluripotent stem cells: paths to new medicines. A catalyst for disease modelling, drug discovery and regenerative therapy. European Molecular Biology Organization Reports, 11(3), 161–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Palma, S. J. , DePalma, S. J. , Davidson, C. D. , Davidson, C. D. , Stis, A. E. , Stis, A. E. , Helms, A. S. , Helms, A. S. , Baker, B. M. ,& Baker, B. M. (2021). Microenvironmental determinants of organized iPSC‐cardiomyocyte tissues on synthetic fibrous matrices. Biomaterials Science, 9, 93–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewenter, M. , von der Lieth, A. , Katus, H. A. , & Backs, J. (2017). Calcium signaling and transcriptional regulation in cardiomyocytes. Circulation Research, 121(8), 1000–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhamoon, A. S. , & Jalife, J. (2005). The inward rectifier current (IK1) controls cardiac excitability and is involved in arrhythmogenesis ‐ PubMed. Heart Rhythm, 2(3), 316–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich, P. , & Dragatsis, I. (2016). Familial dysautonomia: Mechanisms and models. Genetics and Molecular Biology, 39(4), 497–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Difrancesco, D. , Ducouret, P. , & Robinson, R. B. (1989). Muscarinic modulation of cardiac rate at low acetylcholine concentrations. Science, 243(4891), 669–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Difrancesco, D. , & Noble, D. (2012). The funny current has a major pacemaking role in the sinus node. Heart Rhythm, 9(2), 299–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Difrancesco, D. , & Tortora, P. (1991). Direct activation of cardiac pacemaker channels by intracellular cyclic AMP. Nature, 351(6322), 145–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss, M. X. , Di Diego, J. M. , Goodrow, R. J. , Wu, Y. , Cordeiro, J. M. , Nesterenko, V. V. , Barajas‐Martínez, H. , Hu, D. , Urrutia, J. , Desai, M. , Treat, J. A. , Sachinidis, A. , & Antzelevitch, C. (2012). Maximum diastolic potential of human induced pluripotent stem cell‐derived cardiomyocytes depends critically on IKr. PLoS ONE, 7(7), e40288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyachuk, V. , Furlan, A. , Shahidi, M. K. , Giovenco, M. , Kaukua, N. , Konstantinidou, C. , Pachnis, V. , Memic, F. , Marklund, U. , Müller, T. , Birchmeier, C. , Fried, K. , Ernfors, P. , & Adameyko, I. (2014). Neurodevelopment. Parasympathetic neurons originate from nerve‐associated peripheral glial progenitors. Science, 345(6192), 82–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ergir, E. , Oliver‐De La Cruz, J. , Fernandes, S. , Cassani, M. , Niro, F. , Pereira‐Sousa, D. , Vrbský, J. , Vinarský, V. , Perestrelo, A. R. , Debellis, D. , Vadovičová, N. , Uldrijan, S. , Cavalieri, F. , Pagliari, S. , Redl, H. , Ertl, P. , & Forte, G. (2022). Generation and maturation of human iPSC‐derived 3D organotypic cardiac microtissues in long‐term culture. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 17409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernsberger, U. , & Rohrer, H. (2018). Sympathetic tales: subdivisons of the autonomic nervous system and the impact of developmental studies. Neural Development, 13(1), 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escribá, R. , Larrañaga‐Moreira, J. M. , Richaud‐Patin, Y. , Pourchet, L. , Lazis, I. , Jiménez‐Delgado, S. , Morillas‐García, A. , Ortiz‐Genga, M. , Ochoa, J. P. , Carreras, D. , Pérez, G. J. , de La Pompa, J. L. , Brugada, R. , Monserrat, L. , Barriales‐Villa, R. , & Raya, A. (2023). iPSC‐based modeling of variable clinical presentation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation Research, 133(2), 108–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esparza, A. , Jimenez, N. , Joddar, B. , & Natividad‐Diaz, S. (2023). Development of in vitro cardiovascular tissue models within capillary circuit microfluidic devices fabricated with 3D stereolithography printing. SN Applied Sciences, 5(9), 240. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa‐Medina, I. , Outin, E. , Picard, C. A. , Chettouh, Z. , Dymecki, S. , Consalez, G. G. , Coppola, E. , & Brunet, J.‐F. (2014). Neurodevelopment. Parasympathetic ganglia derive from Schwann cell precursors. Science, 345(6192), 87–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa‐Medina, I. , Saha, O. , Boismoreau, F. , Chettouh, Z. , Rossi, F. , Richardson, W. D. , & Brunet, J.‐F. (2016). The sacral autonomic outflow is sympathetic. Science, 354(6314), 893–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feric, N. T. , Pallotta, I. , Singh, R. , Bogdanowicz, D. R. , Gustilo, M. M. , Chaudhary, K. W. , Willette, R. N. , Chendrimada, T. P. , Xu, X. , Graziano, M. P. , & Aschar‐Sobbi, R. (2019). Engineered cardiac tissues generated in the Biowire II: A platform for human‐based drug discovery. Toxicological Sciences, 172(1), 89–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flenner, F. , Jungen, C. , Küpker, N. , Ibel, A. , Kruse, M. , Koivumäki, J. T. , Rinas, A. , Zech, A. T. L. , Rhoden, A. , Wijnker, P. J. M. , Lemoine, M. D. , Steenpass, A. , Girdauskas, E. , Eschenhagen, T. , Meyer, C. , van der Velden, J. , Patten‐Hamel, M. , Christ, T. , & Carrier, L. (2021). Translational investigation of electrophysiology in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology, 157, 77–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forghani, P. , Rashid, A. , Armand, L. C. , Wolfson, D. , Liu, R. , Cho, H. C. , Maxwell, J. T. , Jo, H. , Salaita, K. , & Xu, C. (2024). Simulated microgravity improves maturation of cardiomyocytes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X. , Liu, Q. , Li, C. , Li, Y. , & Wang, L. (2020). Cardiac fibrosis and cardiac fibroblast lineage‐tracing: Recent advances. Frontiers in Physiology, 11, 416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacomelli, E. , Meraviglia, V. , Campostrini, G. , Cochrane, A. , Cao, X. , van Helden, R. W. J. , Krotenberg Garcia, A. , Mircea, M. , Kostidis, S. , Davis, R. P. , van Meer, B. J. , Jost, C. R. , Koster, A. J. , Mei, H. , Míguez, D. G. , Mulder, A. A. , Ledesma‐Terrón, M. , Pompilio, G. , Sala, L. , … Mummery, C. L. (2020). Human‐iPSC‐derived cardiac stromal cells enhance maturation in 3D cardiac microtissues and reveal non‐cardiomyocyte contributions to heart disease. Cell Stem Cell, 26(6), 862–879.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberger, J. J. , Arora, R. , Buckley, U. , & Shivkumar, K. (2019). Autonomic nervous system dysfunction: JACC focus seminar. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 73(10), 1189–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsteen, P. A. , Sabogal Guaqueta, A. M. , Mulder, P. P. M. F. A. , Bos, I. S. T. , Eggens, M. , van der Koog, L. , Soeiro, J. T. , Halayko, A. J. , Mathwig, K. , Kistemaker, L. E. M. , Verpoorte, E. M. J. , Dolga, A. M. , & Gosens, R. (2022). Differentiation and on axon‐guidance chip culture of human pluripotent stem cell‐derived peripheral cholinergic neurons for airway neurobiology studies. Frontiers in Pharmacology,13, 991072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodarzi Hosseinabadi, H. , Biswas, A. , Bhusal, A. , Yousefinejad, A. , Lall, A. , Zimmermann, W.‐H. , Miri, A. K. , & Ionov, L. (2024). 4D‐printable photocrosslinkable polyurethane‐based inks for tissue scaffold and actuator applications. Small, 20(6), e2306387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordan, R. , Gwathmey, J. K. , & Xie, L.‐H. (2015). Autonomic and endocrine control of cardiovascular function. World Journal of Cardiology, 7(4), 204–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grskovic, M. , Javaherian, A. , Strulovici, B. , & Daley, G. Q. (2011). Induced pluripotent stem cells–opportunities for disease modelling and drug discovery. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 10(12), 915–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guhr, A. , Kobold, S. , Seltmann, S. , Seiler Wulczyn, A. E. M. , Kurtz, A. , & Löser, P. (2018). Recent trends in research with human pluripotent stem cells: Impact of research and use of cell lines in experimental research and clinical trials. Stem Cell Reports, 11(2), 485–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häkli, M. , Jäntti, S. , Joki, T. , Sukki, L. , Tornberg, K. , Aalto‐Setälä, K. , Kallio, P. , Pekkanen‐Mattila, M. , & Narkilahti, S. (2022). Human neurons form axon‐mediated functional connections with human cardiomyocytes in compartmentalized microfluidic chip. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(6), 3148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, L. , Li, Y. , Tchao, J. , Kaplan, A. D. , Lin, B. , Li, Y. , Mich‐Basso, J. , Lis, A. , Hassan, N. , London, B. , Bett, G. C. L. , Tobita, K. , Rasmusson, R. L. , & Yang, L. (2014). Study familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy using patient‐specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cardiovascular Research, 104(2), 258–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hergenreder, E. , Minotti, A. P. , Zorina, Y. , Oberst, P. , Zhao, Z. , Munguba, H. , Calder, E. L. , Baggiolini, A. , Walsh, R. M. , Liston, C. , Levitz, J. , Garippa, R. , Chen, S. , Ciceri, G. , & Studer, L. (2024). Combined small‐molecule treatment accelerates maturation of human pluripotent stem cell‐derived neurons. Nature Biotechnology, 42, 1515–1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higo, S. (2023). Disease modeling of desmosome‐related cardiomyopathy using induced pluripotent stem cell‐derived cardiomyocytes. World Journal of Stem Cells, 15(3), 71–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirtle‐Lewis, M. , Desbiens, K. , Ruel, I. , Rudzicz, N. , Genest, J. , Engert, J. C. , & Giannetti, N. (2013). The genetics of dilated cardiomyopathy: A prioritized candidate gene study of LMNA, TNNT2, TCAP, and PLN. Clinical Cardiology, 36(10), 628–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra, M. , Mummery, C. L. , Wilde, A. A. M. , Bezzina, C. R. , & Verkerk, A. O. (2012). Induced pluripotent stem cell derived cardiomyocytes as models for cardiac arrhythmias. Frontiers in Physiology, 3, 346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, D. A. , Bieger, D. , deVente, J. , & Steinbusch, W. M. (1996). Vagal efferent projections: Viscerotopy, neurochemistry and effects of vagotomy. Progress in Brain Research, 107, 79–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovaguimian, A. (2023). Dysautonomia: diagnosis and management. Neurologic Clinics, 41(1), 193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iseoka, H. , Miyagawa, S. , Sakai, Y. , & Sawa, Y. (2021). Cardiac fibrosis models using human induced pluripotent stem cell‐derived cardiac tissues allow anti‐fibrotic drug screening in vitro. Stem Cell Research, 54, 102420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzhaki, I. , Maizels, L. , Huber, I. , Zwi‐Dantsis, L. , Caspi, O. , Winterstern, A. , Feldman, O. , Gepstein, A. , Arbel, G. , Hammerman, H. , Boulos, M. , & Gepstein, L. (2011). Modelling the long QT syndrome with induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature, 471(7337), 225–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, M. Z. , Gruner, K. A. , Qin, C. , & Tourtellotte, W. G. (2014). A neuron autonomous role for the familial dysautonomia gene ELP1 in sympathetic and sensory target tissue innervation. Development (Cambridge, England), 141(12), 2452–2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen, K. R. , & Mirsky, R. (2019). Schwann cell precursors; multipotent glial cells in embryonic nerves. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience, 12, 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juang, J.‐M. J. , & Horie, M. (2016). Genetics of Brugada syndrome. Journal of Arrhythmia, 32(5), 418–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian, T. H. , Syeed, R. , Glascow, N. , & Zis, P. (2020). Alcohol‐induced autonomic dysfunction: A systematic review. Clinical Autonomic Research, 30(1), 29–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]