This secondary analysis of the Finerenone Trial to Investigate Efficacy and Safety Superior to Placebo in Patients With Heart Failure (FINEARTS-HF) randomized clinical trial investigates the breakdown of cause-specific mortality in patients with heart failure and mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction and if this mortality is modified by finerenone.

Key Points

Question

What is the breakdown of cause-specific mortality in patients with heart failure and mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF) or heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) and is cause-specific mortality modified by finerenone?

Findings

In this prespecified secondary analysis of the Finerenone Trial to Investigate Efficacy and Safety Superior to Placebo in Patients With Heart Failure (FINEARTS-HF) randomized clinical trial of HFmrEF/HFpEF, roughly one-half of deaths were ascribed to cardiovascular causes, principally sudden death or HF progression. The proportion of all-cause, cardiovascular, and sudden death was higher in those with EF less than 50%, and regardless of EF, randomization to finerenone did not significantly reduce death or cause-specific death.

Meaning

Results suggest that among patients with HFmrEF/HFpEF, sudden death and death from HF accounted for the majority of cardiovascular deaths; finerenone did not modify cause-specific mortality.

Abstract

Importance

The mode of death in patients with heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF) or heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) remains poorly understood and may vary by EF.

Objective

To evaluate the mode of death according to EF and the treatment effect of finerenone on cause-specific mortality in patients with HFmrEF/HFpEF.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This was a prespecified secondary analysis of the Finerenone Trial to Investigate Efficacy and Safety Superior to Placebo in Patients With Heart Failure (FINEARTS-HF) randomized clinical trial, which evaluated clinical outcomes in 6001 patients with HF and EF greater than or equal to 40% randomly assigned to finerenone or placebo. The mode of death in relation to baseline EF categories (<50%, ≥50-<60%, and ≥60%) was examined, and the effect of randomized treatment on cause-specific death in Cox regression models was assessed. Data analysis was conducted between September 2024 and January 2025.

Interventions

Finerenone vs placebo.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Mode of death as centrally adjudicated by a clinical end points committee.

Results

Of 1013 patients (16.9%; median [IQR] age, 76 [69-82] years; 594 male [58.6%]) who died during median (IQR) follow-up of 32 (23-36) months, mode of death was ascribed to cardiovascular causes in 502 (49.6%), noncardiovascular causes in 368 (36.3%), and undetermined cause in 143 (14.1%). Of cardiovascular deaths, 215 (42.8%) were due to sudden death, 163 (32.4%) to HF, 48 (9.6%) to stroke, 25 (5.0%) to myocardial infarction, and 51 (10.2%) to other cardiovascular causes. The proportion of all-cause, cardiovascular, and sudden death was higher in those with EF less than 50%. The proportion of deaths related to HF was similar across EF categories, and the proportion of deaths due to myocardial infarction, stroke, and other cardiovascular causes was low regardless of EF. Randomization to finerenone did not significantly reduce death or cause-specific death compared with placebo in any EF category.

Conclusions and Relevance

Among patients with HFmrEF/HFpEF in the FINEARTS-HF randomized clinical trial, higher proportions of cardiovascular and overall mortality in those with EF less than 50% were related principally to higher proportions of sudden death. A clear treatment effect of finerenone on cardiovascular or cause-specific mortality was not identified, although the trial was likely underpowered for these outcomes.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04435626

Introduction

Despite recent advances in the development of effective pharmacologic treatment for patients with heart failure and mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF) or heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), rates of morbidity and mortality in this population remain high.1,2 Although novel therapies including angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors,3 sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors,4 and glucagonlike peptide 1 receptor agonists5 may reduce the burden of symptoms and HF hospitalization in selected patients with HFmrEF/HFpEF, none of these has been shown to influence overall rates of death, perhaps in part due to the large proportionate contribution of noncardiovascular causes of death to mortality in this population.2 Mechanisms of cardiovascular death in this population remain unclear, particularly for the relatively understudied subset of patients with ongoing HF symptoms despite improvement in left ventricular EF (LVEF) to greater than 40% (HFimpEF).6

Treatment with the nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA) finerenone was recently shown to reduce the risk of total worsening HF events and death from cardiovascular causes compared with placebo in patients with HFmrEF/HFpEF (inclusive of HFimpEF) enrolled in the Finerenone Trial to Investigate Efficacy and Safety Superior to Placebo in Patients With Heart Failure (FINEARTS-HF) randomized clinical trial.7 In this prespecified secondary analysis, we examined the mode of death according to baseline EF and assessed the effect of finerenone treatment on the incidence of cause-specific death.

Methods

As previously reported,7,8,9 the FINEARTS-HF trial was a prospective, double-blind, randomized comparison of finerenone vs placebo in patients with symptomatic (New York Heart Association grade II-IV) HF, LVEF of 40% or greater, elevated natriuretic peptide levels, and evidence of structural heart disease. The trial protocol and statistical analysis plan are available in Supplement 1. Patients with prior LVEF of less than 40% (HFimpEF) were eligible for participation. Patients self-identified with the following races and ethnicities: Asian, Black, White, and other, which included American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, Other Pacific Islander, or unreported. Race and ethnicity information was included in this analysis to inform the generalizability of the study results. The primary study outcome was a composite of total worsening HF events (defined as first or recurrent unplanned hospitalizations or urgent visits for HF) and death from cardiovascular causes. Mode of death was centrally adjudicated according to standardized criteria (eMethods in Supplement 2) by a clinical end points committee (CEC) blinded to randomized treatment assignment. The study protocol was approved by institutional review boards or ethics committees at each participating site prior to enrollment of the first patient. All patients provided written informed consent for participation. This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guidelines.

The CEC classified all deaths as cardiovascular, noncardiovascular, or undetermined, and further subclassified cardiovascular deaths as sudden deaths or non–sudden deaths due to acute myocardial infarction (MI), HF, stroke, or other cardiovascular causes (eMethods in Supplement 2). Death due to acute MI was defined as a cardiovascular death within 30 days of a clinical MI. Sudden death was defined as unexpected death in an otherwise stable patient, not within 30 days of an MI. Death due to HF was defined as death in the context of clinically worsening symptoms and/or signs of HF with no other apparent cause. Death due to stroke was assigned for deaths due to complications of ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke.

Statistical Analysis

In this prespecified analysis, we examined the adjudicated mode of death in subgroups defined by categories of baseline LVEF (<50%, ≥50-<60%, and ≥60%) and separately among patients with HFimpEF.10 Baseline characteristics were summarized for patients who died according to mode of death (cardiovascular, noncardiovascular, undetermined) using standard parametric and nonparametric tests. Incidence rates for cause-specific death were calculated as number of events per 100 patient-years of follow-up. Associations between continuous variables (age, estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR], EF) and incidence rates for cause-specific mortality were estimated using Poisson regression, with potential nonlinearity accommodated by using polynomial (eg, quadratic, cubic) terms. The effect of randomized treatment on cause-specific death was evaluated in Cox regression models, stratified by geographic region and baseline LVEF (<60% or ≥60%), All analyses were conducted in Stata, version 17.0 (StataCorp) with 2-sided P < .05 used as the threshold for statistical significance. Data analysis was conducted between September 2024 and January 2025.

Results

Among 6001 validly randomized participants in the FINEARTS-HF randomized clinical trial, there were 1013 patients (16.9%; median [IQR] age, 76 [69-82] years; 419 female [41.4%]; 594 male [58.6%]) who died during median (IQR) follow-up of 32 (23-36) months. Patients who died had self-identified with the following races and ethnicities: 156 Asian (15.4%), 11 Black (1.1%), 827 White (81.6%), and 19 other (1.9%). Of those who died, death was attributed to cardiovascular causes in 502 (49.6%), noncardiovascular causes in 368 (36.3%), and undetermined cause in 143 (14.1%). Of the cardiovascular deaths, 215 (42.8%) were due to sudden death, 163 (32.4%) to HF, 48 (9.6%) to stroke, 25 (5.0%) to MI, and 51 (10.2%) to other cardiovascular causes (eFigure in Supplement 2). Clinical characteristics at baseline for the 1013 patients who died are summarized by cause of death in Table 1.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics by Mode of Death Among Patients Who Died.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P value (all groups) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CV death (n = 502) | Non-CV death (n = 368) | Undetermined (n = 143) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 73.43 (9.82) | 76.23 (8.67) | 75.76 (9.41) | <.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 203 (40.4) | 149 (40.5) | 67 (46.9) | .36 |

| Male | 299 (59.6) | 219 (59.5) | 76 (53.1) | |

| Race | ||||

| Asian | 78 (15.5) | 45 (12.2) | 33 (23.1) | .14 |

| Black | 4 (0.8) | 5 (1.4) | 2 (1.4) | |

| White | 410 (81.7) | 311 (84.5) | 106 (74.1) | |

| Othera | 10 (2.0) | 7 (1.9) | 2 (1.4) | |

| Region | ||||

| Asia | 78 (15.5) | 45 (12.2) | 32 (22.4) | <.001 |

| Eastern Europe | 222 (44.2) | 137 (37.2) | 64 (44.8) | |

| Latin America | 61 (12.2) | 40 (10.9) | 12 (8.4) | |

| North America | 34 (6.8) | 42 (11.4) | 19 (13.3) | |

| Western Europe, Oceania, and others | 107 (21.3) | 104 (28.3) | 16 (11.2) | |

| Any prior HF hospitalization | 346 (68.9) | 239 (64.9) | 104 (72.7) | .20 |

| Recency of HF event | ||||

| ≤7 d From randomization | 127 (25.3) | 91 (24.7) | 32 (22.4) | .54 |

| >7 d to ≤3 mo | 164 (32.7) | 104 (28.3) | 44 (30.8) | |

| >3 mo or No index HF event | 211 (42.0) | 173 (47.0) | 67 (46.9) | |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | 127.73 (15.68) | 129.28 (15.57) | 127.12 (17.41) | .25 |

| Body mass index, mean (SD)b | 29.84 (6.49) | 29.39 (6.40) | 29.41 (7.53) | .56 |

| Creatinine, mean (SD), mg/dL | 1.23 (0.39) | 1.27 (0.41) | 1.24 (0.37) | .40 |

| eGFR, mean (SD), mL/min/1.73 m2 | 56.59 (19.16) | 54.13 (19.02) | 53.77 (19.06) | .10 |

| UACR, median (IQR), mg/g | 38 (11-145) | 27 (9-131) | 40 (14-180) | .80 |

| Potassium, mean (SD), mmol/L | 4.34 (0.52) | 4.34 (0.50) | 4.40 (0.51) | .37 |

| LVEF, mean (SD), % | 51.57 (8.00) | 53.46 (8.08) | 51.49 (7.38) | <.001 |

| NT-proBNP, median (IQR), pg/mL | 1773 (950-3329) | 1533 (746-2974) | 1865 (873-3574) | .03 |

| NYHA class | ||||

| NYHA class II | 291 (58.0) | 217 (59.0) | 86 (60.1) | .62 |

| NYHA class III | 202 (40.2) | 145 (39.4) | 57 (39.9) | |

| NYHA class IV | 9 (1.8) | 6 (1.6) | 0 | |

| History of hypertension | 447 (89.0) | 331 (89.9) | 128 (89.5) | .91 |

| Diabetes | 255 (50.8) | 199 (54.1) | 68 (47.6) | .37 |

| Atrial fibrillation on baseline electrocardiogram | 225 (44.8) | 152 (41.3) | 62 (43.4) | .59 |

| History of stroke | 68 (13.5) | 48 (13.0) | 22 (15.4) | .78 |

| History of myocardial infarction | 159 (31.7) | 104 (28.3) | 33 (23.1) | .12 |

| Prior LVEF <40% (HFimpEF) | 24 (4.8) | 13 (3.5) | 4 (2.8) | .47 |

| β-Blocker use | 414 (82.5) | 312 (84.8) | 110 (76.9) | .11 |

| ACEI/ARB/ARNI use | 380 (75.7) | 275 (74.7) | 98 (68.5) | .22 |

| SGLT-2 inhibitor use | 77 (15.3) | 44 (12.0) | 16 (11.2) | .24 |

| Loop diuretic | 464 (92.4) | 331 (89.9) | 138 (96.5) | .04 |

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, Angiotensin receptor blockers; ARNI, angiotensin receptor/neprilysin inhibitor; CV, cardiovascular; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF, heart failure; HFimpEF, heart failure with improved ejection fraction; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SGLT-2, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2; UACR, urine albumin-creatinine ratio.

SI conversion factor: To convert creatinine to micromoles per liter, multiply by 88.4; potassium to milliequivalents per liter, divide by 1.

Other race includes American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, Other Pacific Islander, or unreported.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

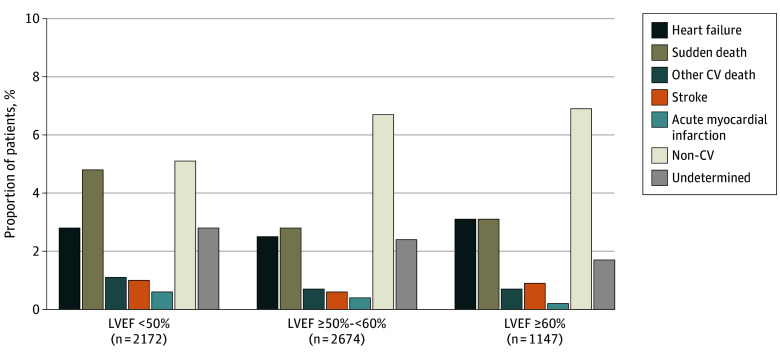

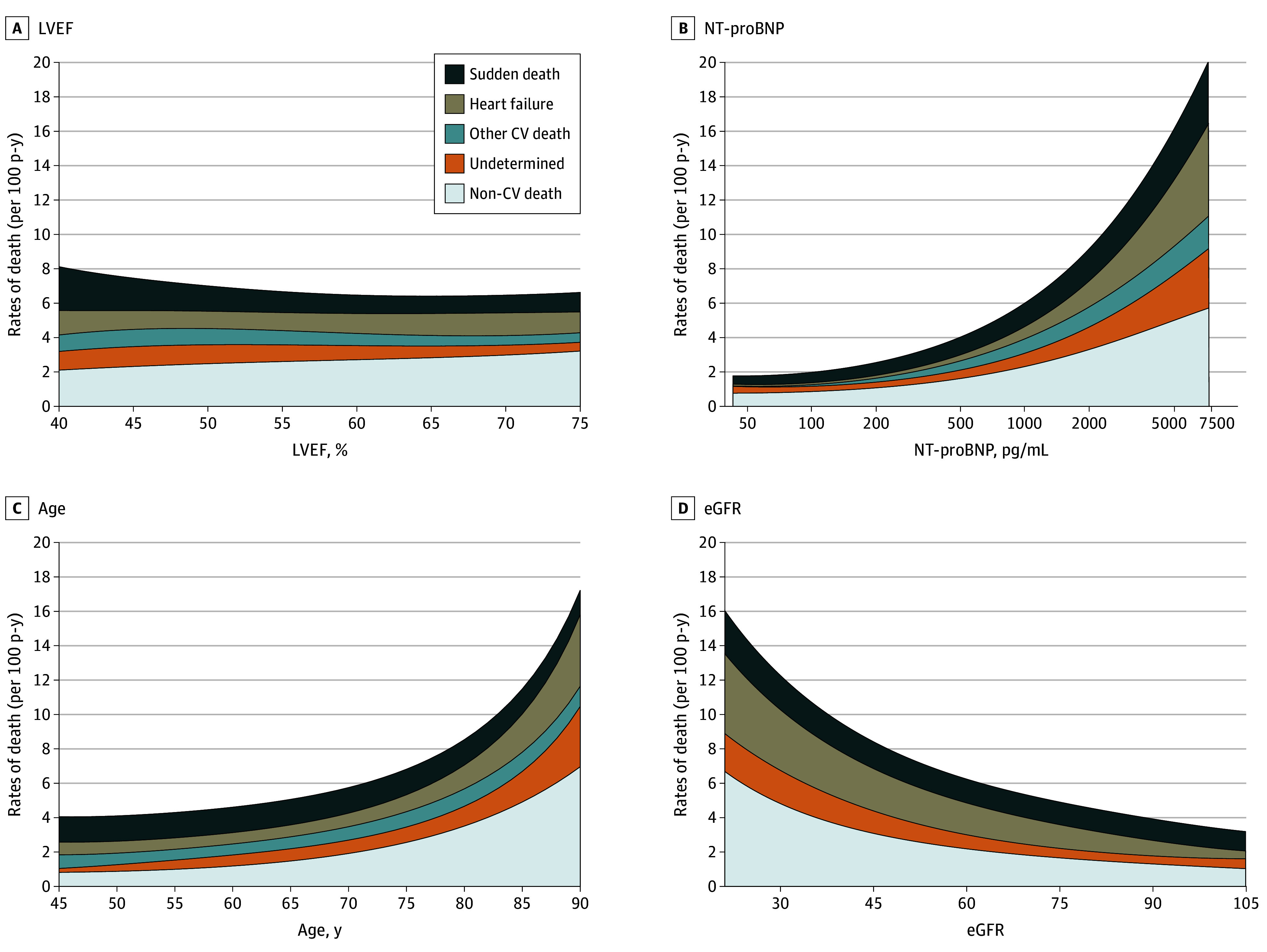

The breakdown of cause-specific mortality according to baseline LVEF categories is shown in Table 2 and Figure 1. The incidence of all-cause, cardiovascular, and sudden death was highest in those with LVEF less than 50%. The proportion of deaths related to HF was similar across LVEF categories, and that due to MI, stroke, and other cardiovascular causes was low regardless of LVEF. Across the full range of continuous LVEF, higher rates of overall cardiovascular mortality with lower LVEF appeared to be contributed principally by higher rates of sudden death. Rates of noncardiovascular death did not vary significantly by LVEF but did increase steeply in relation to older age and lower eGFR. Rates of both cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality appeared to increase in relation to higher N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide level, particularly death to worsening HF (Figure 2). The incidence of death from any cause and the distribution of cause-specific mortality were similar in the 273 patients (4.5%) with HFimpEF and the residual population with no history of LVEF less than 40% (overall mortality: 15% [41 of 273] vs 17% [972 of 5728]; proportion of cardiovascular, noncardiovascular, undetermined deaths: 58.5% [24 of 41], 31.7% [13 of 41], 9.8% [4 of 41] vs 49.2% [478 of 972], 36.5% [355 of 972], 14.3% [139 of 972], respectively) (Table 2).

Table 2. Incidence and Proportion of Deaths by Cause According to Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF) at Baseline and Prior LVEF Less Than 40% (HFimpEF) Among Patients Who Died.

| Variable | LVEF <50% (n = 2172) | LVEF ≥50-<60% (n = 2674) | LVEF ≥60% (n = 1147) | P value for trend | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (% of deaths) | Rate/100 p-y | No. (% of deaths) | Rate/100 p-y | No. (% of deaths) | Rate/100 p-y | Proportions (incidence rates) | Incidence rates | |

| Total deaths | 393 (100.0) | 7.5 | 430 (100.0) | 6.8 | 189 (100.0) | 6.3 | NA | .04 |

| CV death | 222 (56.5) | 4.2 | 189 (44.0) | 3.0 | 91 (48.1) | 3.0 | .01 | .001 |

| Heart failure | 60 (15.3) | 1.1 | 67 (15.6) | 1.1 | 36 (19.0) | 1.2 | .30 | .91 |

| Sudden death | 105 (26.7) | 2.0 | 75 (17.4) | 1.2 | 35 (18.5) | 1.2 | .005 | <.001 |

| Stroke | 21 (5.3) | 0.4 | 17 (4.0) | 0.3 | 10 (5.3) | 0.3 | .79 | .48 |

| MI | 13 (3.3) | 0.2 | 10 (2.3) | 0.2 | 10 (2.3) | 0.1 | .10 | .05 |

| Other CV death | 23 (5.9) | 0.4 | 20 (4.7) | 0.3 | 8 (4.2) | 0.3 | .35 | .17 |

| Non-CV death | 110 (28.0) | 2.1 | 178 (41.4) | 2.8 | 79 (41.8) | 2.6 | <.001 | .07 |

| Undetermined | 61 (15.5) | 1.2 | 63 (14.7) | 1.0 | 19 (10.1) | 0.6 | .10 | .02 |

| Variable | Prior EF <40% (HFimpEF, n = 273) | No prior EF <40% (n = 5728) | P value | |||||

| No. | Deaths, % | Rate/100 p-y | No. | Deaths, % | Rate/100 p-y | Proportions | Incidence rates | |

| Total deaths | 41 | 100 | 6.3 | 972 | 100 | 7.0 | NA | .55 |

| CV death | 24 | 58.5 | 3.7 | 478 | 49.2 | 3.4 | .24 | .71 |

| Heart failure | 11 | 26.8 | 1.7 | 152 | 15.6 | 1.1 | .06 | .15 |

| Sudden death | 6 | 14.6 | 0.9 | 209 | 21.5 | 1.5 | .29 | .24 |

| Stroke | 2 | 4.9 | 0.3 | 46 | 4.7 | 0.3 | .97 | .93 |

| MI | 3 | 7.3 | 0.5 | 22 | 2.3 | 0.2 | .04 | .07 |

| Other CV death | 2 | 4.9 | 0.3 | 49 | 5.0 | 0.4 | .96 | .86 |

| Non-CV death | 13 | 31.7 | 2.0 | 355 | 36.5 | 2.6 | .53 | .40 |

| Undetermined | 4 | 9.8 | 0.6 | 139 | 14.3 | 1.0 | .41 | .34 |

Abbreviations: CV, cardiovascular; HFimpEF, heart failure with improved ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; p-y, patient-year.

Figure 1. Adjudicated Mode of Death According to Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF).

CV indicates cardiovascular; p-y, patient-year.

Figure 2. Variation in Incidence of Adjudicated Mode of Death by Continuous Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF), N-Terminal Pro–Brain Natriuretic Peptide (NT-proBNP), Age, and Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR).

SI conversion factor: To convert NT-proBNP to nanograms per liter, multiply by 1. CV indicates cardiovascular.

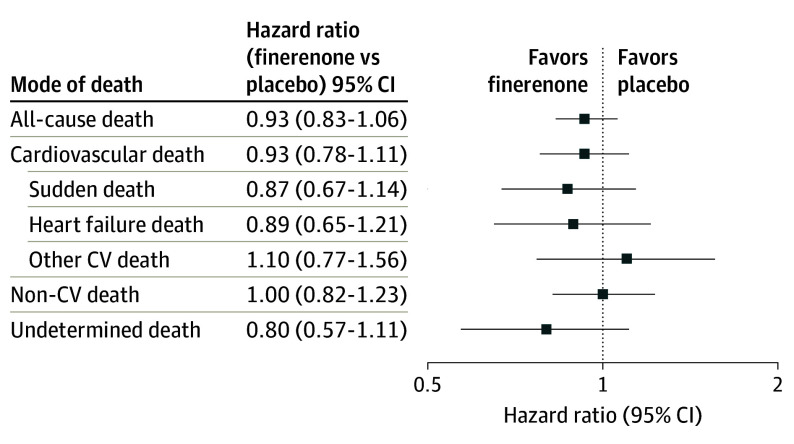

The effects of assignment to finerenone compared with placebo on cause-specific mortality are displayed in Figure 3. Although rates of overall death and cardiovascular death were numerically lower in patients allocated to finerenone, treatment with finerenone did not significantly reduce all-cause death or any specific mode of death relative to placebo. There was no detectable variation in the effects of finerenone treatment on cardiovascular mortality by LVEF or in those with HFimpEF (interaction P = .40 and 0.52, respectively).

Figure 3. Effect of Finerenone Compared With Placebo on Cause-Specific Mortality.

CV indicates cardiovascular.

Discussion

In this prespecified analysis of adjudicated mode of death in patients with HF and LVEF of 40% or higher enrolled in the FINEARTS-HF randomized clinical trial, we noted that roughly one-half of deaths during a median follow-up of 32 months were related to cardiovascular causes. Although the overall incidence of CV death was low (3.5 per 100 patient-years), three-fourths of cardiovascular deaths were attributed to sudden death or HF progression, with few deaths ascribed to incident MI, stroke, or other cardiovascular causes. Higher rates of cardiovascular death in those with LVEF less than 50% appeared to be principally driven higher rates of sudden cardiac death in this group. The proportionate contribution of noncardiovascular death did not appear to vary by LVEF but was higher in those with older age and lower eGFR. Overall mortality rates and the distribution of mode of death were similar in the 4.5% of enrolled patients who had history of LVEF less than 40% (HFimpEF) and those with LVEF consistently 40% or greater. Assignment to finerenone did not appear to reduce overall mortality or cause-specific mortality in any LVEF subgroup.

These data add to the growing body of literature highlighting that as in patients with HFrEF, sudden death and HF progression are the primary drivers of cardiovascular mortality in patients with HFmrEF/HFpEF.3,4 Because patients with HF and higher LVEF are generally at lower risk for ventricular arrhythmias or pump failure than those with lower LVEF, alternate mechanisms of terminal disease progression including electromechanical dissociation, kidney failure, and right ventricular failure may be more important in HFpEF.11 Higher rates of overall mortality in those with HFmrEF (LVEF ≥40-<50%) compared with residual population with HFpEF (LVEF ≥50%) in the FINEARTS-HF trial were driven by higher rates of sudden death, underscoring the similarities between HFmrEF and HFrEF and lending support to the growing consensus that these patients may respond similarly to guideline-directed treatment.12

Prior observational data have suggested lower rates of overall mortality in those with HFimpEF compared with those with HFrEF and HFpEF.13 Although the number of enrolled patients with HFimpEF was small, we observed similar rates of all modes of death in these patients and in those with LVEF consistently greater than 40%, as was observed in the Dapagliflozin Evaluation to Improve the Lives of Patients With Preserved Ejection Fraction Heart Failure (DELIVER) trial,6 which used similar eligibility criteria. Although this difference could be related to the deliberate inclusion of higher-risk patients with HF in clinical trials, it emphasizes that despite improvement in LVEF, symptomatic patients with HFimpEF remain at risk for cardiovascular mortality and sudden death. Because the evidence base for treatment of HFimpEF remains limited, these data support continued inclusion of these patients in future trials of HFmrEF/HFpEF.

Although rates of all-cause death, cardiovascular death, sudden death, and HF death were lower among patients assigned to finerenone, we did not observe a statistically significant reduction in any specific mode of death with finerenone compared with placebo; however, the FINEARTS-HF trial was not prospectively designed to detect a treatment effect on overall mortality or cause specific-death and was likely underpowered for these outcomes. In a recent individual patient meta-analysis14 pooling data across trials of MRAs in HF, the pooled hazard ratios (HRs) for cardiovascular mortality (HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.80-1.05) and all-cause mortality (HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.85-1.03) also favored MRA treatment but failed to confirm a treatment benefit. Ongoing challenges in developing effective treatments to reduce the risk of cardiovascular mortality in HFpEF likely reflect the inability of cardiovascular treatments to favorably modulate the competing risk of death from noncardiovascular causes in this population.15 Our data highlight that noncardiovascular death accounts for an even greater proportion of total mortality in older patients and those with more advanced chronic kidney disease who are at high risk for development of HFmrEF/HFpEF. Additional studies of finerenone being conducted as part of the MOONRAKER program including A Study to Determine the Efficacy and Safety of Finerenone on Morbidity and Mortality Among Hospitalized Heart Failure Patients (REDEFINE-HF) trial,16 A Study to Evaluate Finerenone on Clinical Efficacy and Safety in Patients With Heart Failure Who Are Intolerant or Not Eligible for Treatment With Steroidal Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists (FINALITY-HF) trial,17 and A Study to Determine the Efficacy and Safety of Finerenone and SGLT2i in Combination in Hospitalized Patients With Heart Failure (CONFIRMATION-HF) trial18 will complement these data from the FINEARTS-HF trial and provide additional insight into the effects of finerenone on cardiovascular death.

Limitations

This study should be viewed in the context of important limitations. Even with centralized adjudication, it is challenging to accurately determine the cause of death from clinical record review, particularly when autopsy data are not available. As well, mode of death among patients enrolled in clinical trials (even international trials as broadly representative as FINEARTS-HF) may not accurately represent the distribution of mode of death among unselected patients in clinical practice.

Conclusions

In this prespecified secondary analysis from the randomized FINEARTS-HF trial, we found that sudden cardiac death is a leading contributor to cardiovascular death in patients with HF and EF of 40% or greater, particularly in those with mildly reduced EF. As well, noncardiovascular death accounts for more than half of total mortality in this population, with particularly high incidence in those who are older or have worse kidney function. Although finerenone reduces composite cardiovascular events in patients with HFmrEF/HFpEF, we did not identify a treatment effect on any specific mode of death, underscoring the need for further study to identify strategies to reduce mortality in this population.

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan.

eMethods.

eFigure. Adjudicated Mode of Death Among Patients Who Died (N=1013), FINEARTS-HF

Data Sharing Statement.

References

- 1.Vaduganathan M, Patel RB, Michel A, et al. Mode of death in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(5):556-569. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solomon SD, Wang D, Finn P, et al. Effect of candesartan on cause-specific mortality in heart failure patients: the Candesartan in Heart failure Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity (CHARM) program. Circulation. 2004;110(15):2180-2183. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000144474.65922.AA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Desai AS, Vaduganathan M, Cleland JG, et al. Mode of death in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: insights from PARAGON-HF trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2021;14(12):e008597. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.121.008597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desai AS, Jhund PS, Claggett BL, et al. Effect of dapagliflozin on cause-specific mortality in patients with heart failure across the spectrum of ejection fraction: a participant-level pooled analysis of DAPA-HF and DELIVER. JAMA Cardiol. 2022;7(12):1227-1234. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2022.3736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kosiborod MN, Deanfield J, Pratley R, et al. ; SELECT, FLOW, STEP-HFpEF, and STEP-HFpEF DM Trial Committees and Investigators . Semaglutide vs placebo in patients with heart failure and mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction: a pooled analysis of the SELECT, FLOW, STEP-HFpEF, and STEP-HFpEF DM randomized trials. Lancet. 2024;404(10456):949-961. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01643-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vardeny O, Desai AS, Jhund PS, et al. Dapagliflozin and mode of death in heart failure with improved ejection fraction: a post hoc analysis of the DELIVER trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2024;9(3):283-289. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2023.5318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Vaduganathan M, et al. ; FINEARTS-HF Committees and Investigators . Finerenone in heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2024;391(16):1475-1485. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2407107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaduganathan M, Claggett BL, Lam CSP, et al. Finerenone in patients with heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction: rationale and design of the FINEARTS-HF trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2024;26(6):1324-1333. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.3253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solomon SD, Ostrominski JW, Vaduganathan M, et al. Baseline characteristics of patients with heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction: the FINEARTS-HF trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2024;26(6):1334-1346. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.3266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bozkurt B, Coats AJS, Tsutsui H, et al. Universal definition and classification of heart failure: a report of the Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, Japanese Heart Failure Society and Writing Committee of the Universal Definition of Heart Failure: Endorsed by the Canadian Heart Failure Society, Heart Failure Association of India, Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand, and Chinese Heart Failure Association. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23(3):352-380. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greene SJ, Gheorghiade M. Matching mechanism of death with mechanism of action: considerations for drug development for hospitalized heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(15):1599-1601. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.06.1199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nauta JF, Hummel YM, van Melle JP, et al. What have we learned about heart failure with midrange ejection fraction 1 year after its introduction? Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19(12):1569-1573. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalogeropoulos AP, Fonarow GC, Georgiopoulou V, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of adult outpatients with heart failure and improved or recovered ejection fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1(5):510-518. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.1325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jhund PS, Talebi A, Henderson AD, et al. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in heart failure: an individual patient level meta-analysis. Lancet. 2024;404(10458):1119-1131. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01733-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kondo T, Henderson AD, Docherty KF, et al. Why Have we not been able to demonstrate reduced mortality in patients with HFmrEF/HFpEF? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;84(22):2233-2240. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2024.08.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.A study to determine the efficacy and safety of finerenone on morbidity and mortality among hospitalized heart failure patients (REDEFINE-HF). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT06008197. Updated March 1, 2024. Accessed March 13, 2025. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06008197

- 17.A study to evaluate finerenone on clinical efficacy and safety in patients with heart failure who are intolerant or not eligible for treatment with steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (FINALITY-HF). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT06033950. Updated March 11, 2025. Accessed March 13, 2025. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06033950

- 18.A study to determine the efficacy and safety of finerenone and SGLT2i in combination in hospitalized patients with heart failure (CONFIRMATION-HF). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT06024746. Updated March 11, 2025. Accessed March 13, 2025. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06024746

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan.

eMethods.

eFigure. Adjudicated Mode of Death Among Patients Who Died (N=1013), FINEARTS-HF

Data Sharing Statement.