Abstract

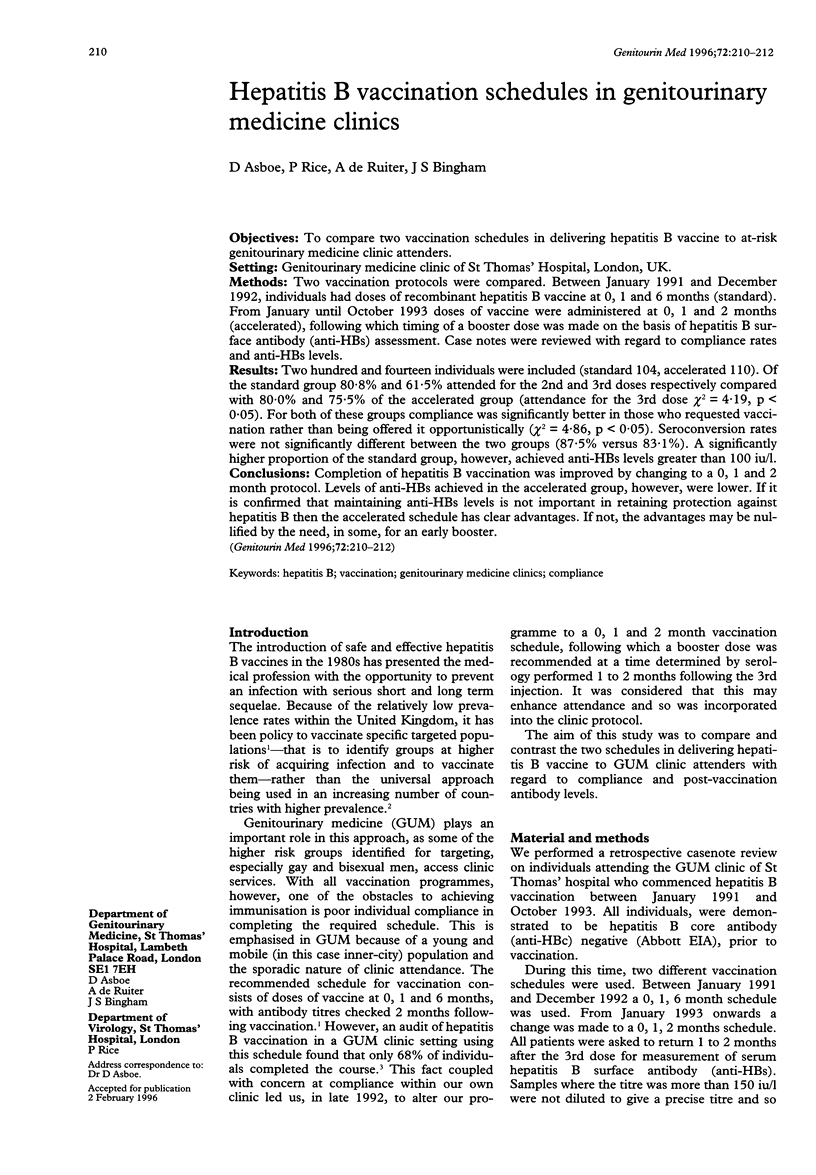

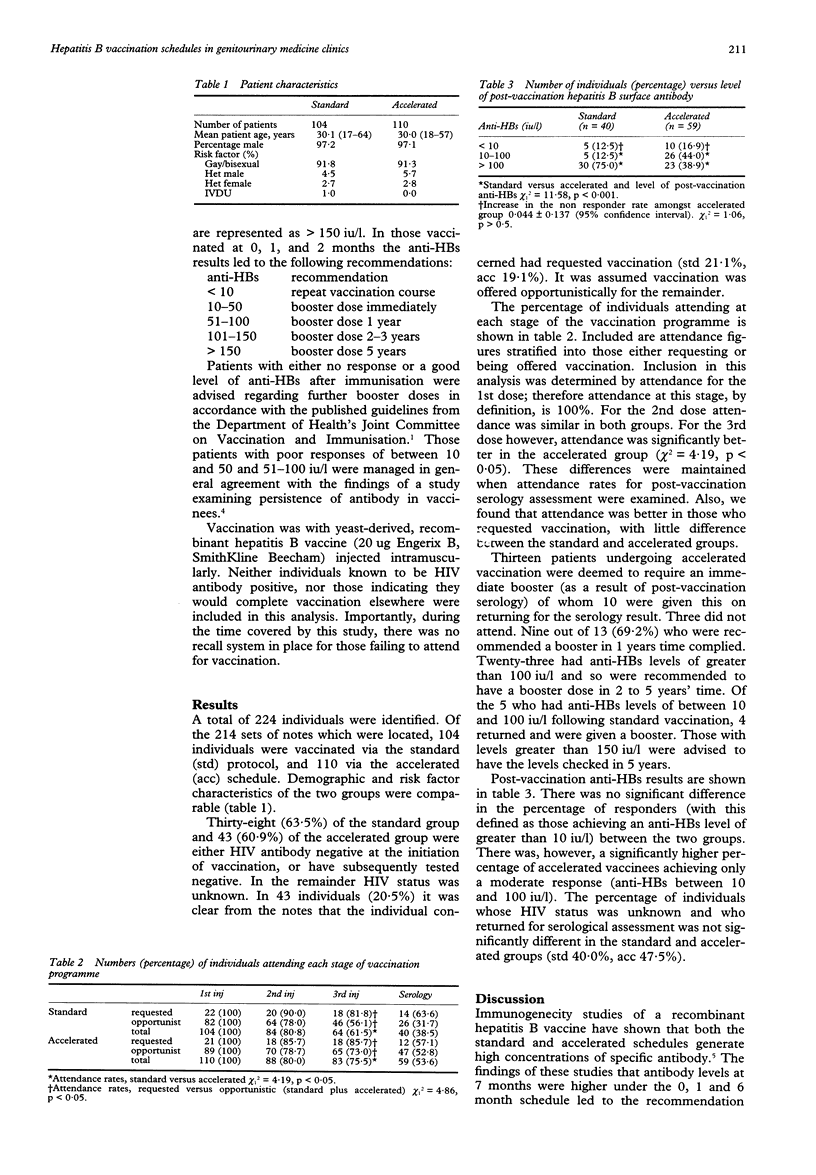

OBJECTIVES: To compare two vaccination schedules in delivering hepatitis B vaccine to at-risk genitourinary medicine clinic attenders. SETTING: Genitourinary medicine clinic of St Thomas' Hospital, London, UK. METHODS: Two vaccination protocols were compared. Between January 1991 and December 1992, individuals had doses of recombinant hepatitis B vaccine at 0, 1 and 6 months (standard). From January until October 1993 doses of vaccine were administered at 0, 1 and 2 months (accelerated), following which timing of a booster dose was made on the basis of hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs) assessment. Case notes were reviewed with regard to compliance rates and anti-HBs levels. RESULTS: Two hundred and fourteen individuals were included (standard 104, accelerated 110). Of the standard group 80.8% and 61.5% attended for the 2nd and 3rd doses respectively compared with 80.0% and 75.5% of the accelerated group (attendance for the 3rd dose chi 2 = 4.19, p < 0.05). For both of these groups compliance was significantly better in those who requested vaccination rather than being offered it opportunistically (chi 2 = 4.86, p < 0.05). Seroconversion rates were not significantly different between the two groups (87.5% versus 83.1%). A significantly higher proportion of the standard group, however, achieved anti-HBs levels greater than 100 i.u./l. CONCLUSIONS: Completion of hepatitis B vaccination was improved by changing to a 0, 1 and 2 month protocol. Levels of anti-HBs achieved in the accelerated group, however, were lower. If it is confirmed that maintaining anti-HBs levels is not important in retaining protection against hepatitis B then the accelerated schedule has clear advantage. If not, the advantages may be nullified by the need, in some, for an early booster.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bhatti N., Gilson R. J., Beecham M., Williams P., Matthews M. P., Tedder R. S., Weller I. V. Failure to deliver hepatitis B vaccine: confessions from a genitourinary medicine clinic. BMJ. 1991 Jul 13;303(6794):97–101. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6794.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadler S. C., Francis D. P., Maynard J. E., Thompson S. E., Judson F. N., Echenberg D. F., Ostrow D. G., O'Malley P. M., Penley K. A., Altman N. L. Long-term immunogenicity and efficacy of hepatitis B vaccine in homosexual men. N Engl J Med. 1986 Jul 24;315(4):209–214. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198607243150401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall A. J. Hepatitis B vaccination: protection for how long and against what? BMJ. 1993 Jul 31;307(6899):276–277. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6899.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess G., Hingst V., Cseke J., Bock H. L., Clemens R. Influence of vaccination schedules and host factors on antibody response following hepatitis B vaccination. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1992 Apr;11(4):334–340. doi: 10.1007/BF01962073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane M. Global programme for control of hepatitis B infection. Vaccine. 1995;13 (Suppl 1):S47–S49. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)80050-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilzey A. J. Hepatitis B vaccine boosting: the debate continues. Lancet. 1995 Apr 22;345(8956):1000–1001. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90751-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilzey A. J., Palmer S. J., Banatvala J. E., Vines S. K., Gilks W. R. Hepatitis B vaccine boosting among young healthy adults. Lancet. 1994 Nov 19;344(8934):1438–1439. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90609-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]