Abstract

Aversive learning can produce a wide variety of defensive behavioral responses depending on the circumstances, ranging from reactive responses like freezing to proactive avoidance responses. While most of this initial learning is behaviorally supported by an expectancy of an aversive outcome and neurally supported by activity within the basolateral amygdala, activity in other brain regions become necessary for the execution of defensive strategies that emerge in other aversive learning paradigms such as active avoidance. Here, we review the neural circuits that support both reactive and proactive defensive behaviors that are motivated by aversive learning, and identify commonalities between the neural substrates of these distinct (and often exclusive) behavioral strategies.

Keywords: Fear conditioning, Avoidance, Basolateral amygdala, Prefrontal cortex

1. Introduction

When an association is made between a neutral stimulus and an aversive stimulus, a number of defensive behaviors may occur in response to later presentations of the previously-neutral stimulus depending on the situation. These can include reactive behaviors like freezing or proactive responses like running. When is it appropriate to employ different defensive responses? And what are the circuits recruited for each kind of behavioral response to danger? We can answer these questions using various paradigms of conditioned fear and active avoidance in rodents. Behavioral differences associated with learning about and responding to danger vary by task demand, and as task demands change, different neural substrates are recruited. While most learned defensive behaviors initially stem from aversive fear learning primarily mediated by activity in the basolateral amygdala, task demands can dictate both the behavioral response adopted as well as circuit level changes that support behavior.

Traditional experimental designs of fear conditioning involve a discrete stimulus or context that is paired with footshocks, and these generally produce a reactive freezing response when presented with that stimulus or context. In contrast, a wide array of avoidance responses can be conditioned depending on experimental parameters. Here, we review the basic behavioral findings and the neural substrates that underlie four broad categories of behavioral responses during associative learning of aversive stimuli: freezing, movement-based avoidance (including shuttling and wheel-run avoidance), lever press avoidance, and platform-mediated avoidance. We then discuss the behavioral and neurobiological differences that accompany seemingly small or nuanced changes in task design, with the overall conclusion that experimental parameters determine not only behavioral output but the underlying neural circuitry that promotes behavioral responding.

2. Freezing as a conditional response: Delay, trace, and context fear

In situations where escape or avoidance is impossible, the primary conditional response observed in rodents and other mammals is freezing. The freezing response has been commonly defined as the animal ceasing all movement except breathing (Fanselow, 1980). In these paradigms, animals receive pairings of either a discrete neutral stimulus or surrounding contextual cues with footshocks. This learning is sufficient to produce a robust fear response when either the stimulus or context is presented later. Freezing as a conditional response seems to rely primarily on circuitry within the amygdala for expression. Information about the conditional stimulus (CS) and unconditional stimulus (US) converge onto the lateral amygdala (LA), which projects to the basal amygdala (BA) and then the central amygdala (CeA) (reviewed in Pape & Pare, 2010; Duvarci & Pare, 2014). Within CeA, mutually inhibitory circuit cell populations in the centrolateral amygdala (CeL) disinhibit amygdalar output neurons in centromedial amygdala (CeM) (Ciocchi et al., 2010; Haubensak et al., 2010). However, subtle differences in the paradigm can create drastic differences in neural substrates that underlie this freezing behavior.

2.1. Delay fear conditioning

In a standard delay fear conditioning paradigm, a discrete CS, such as a tone or a light, co-terminates with an aversive US (e.g., footshock) that is typically shorter in duration than the CS (e.g., a 10-sec CS co-terminates with a 1-sec US). In this way, there is a delay between the onset of the CS and the onset of the US, such that during the CS the animal can prepare for the upcoming delivery of the US. Delay fear conditioning relies on a well-defined neural substrate that focuses primarily on dynamic changes within the amygdala for its acquisition (Ciocchi, et al., 2010; Li, et al., 2013; Rogan, et al., 1997; for reviews, see Duvarci & Pare, 2014; Herry & Johansen, 2014), and later expression is dependent on basolateral amygdala (BLA; e.g., Kochli et al., 2015) and prelimbic (PL; Sierra-Mercado et al., 2011) activity.

In situations in which the CS is an auditory stimulus, input from the medial geniculate thalamus (MgN; auditory thalamus) to the amygdala drives acquisition of this memory. Plastic changes in the MgN-BLA pathway are needed for acquisition and expression of this memory (Maren et al., 2001), and inhibiting neural activity in the amygdala (Phillips & LeDoux, 1992) or the MgN (Ferrara et al., 2017) during CS-US pairings prevents the acquisition of delay fear memory expressed through the freezing response during a recall test. Importantly, BLA activity still increases even after extensive training with many CS-US presentations (Maren, 2000), suggesting that the role of the BLA does not change even as the CS-US association is well-learned. Other work has also reported that other regions, including the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (PVT; Penzo et al., 2015; Do-Monte et al., 2015; Do Monte et al., 2016) and ventral hippocampus (Sierra-Mercado et al., 2011), are necessary for expression of delay fear conditioning.

It should be noted that several researchers have examined conditioned suppression as an additional measure of conditional fear following delay fear conditioning. Here, animals are initially taught to lever press for a food reward prior to pairing of a discrete CS with a shock US. Later, ongoing lever-press behavior is assessed when the CS is presented. Animals will typically suppress their lever pressing in response to the tone. While this type of learning seems to rely on the amygdala (like conditional freezing), some subtle differences do exist. For example, while BLA lesions affect acquisition of conditional freezing, discrimination between a CS that signals a shock and one that does not (i.e., a CS-) remains intact when assessed using conditioned suppression (McDannald & Galarce, 2011). Other work has demonstrated that conditioned suppression may preferentially rely on the CeA rather than the BLA (Campese et al., 2015; Killcross et al., 1997; see also McDannald, 2010).

While a majority of the work in delay fear conditioning has examined males, more recent work has aimed to dissect how conditional fear responses differ based on sex. Very few studies have demonstrated robust sex differences in the freezing response in delay fear conditioning (reviewed in Bauer, 2023). Some nuanced sex differences do exist, however, in that females show a reduced ability to discriminate between a CS that has been paired with a shock and one that has not (Greiner et al., 2019; Trask et al., 2020) suggesting important differences in response inhibition and discrimination (see also Krueger et al., 2024).

Finally, it should be noted that even when avoidance or escape is not possible in a delay fear conditioning task, some animals instead show what has been termed a ‘proactive’ (as opposed to reactive) fear response: darting. In the initial finding (Gruene et al., 2015), darting was described as “a rapid, forward movement across the chamber that resembled an escape-like response.” While some reports have suggested that this is a conditional response that occurs more frequently in females (Greiner et al., 2019; Gruene et al., 2015), others have found that this can emerge in males with more extensive conditioning paradigms and is related to individual differences in shock reactivity (Mitchell et al., 2022). However, additional work demonstrated that darting was largely an unconditional response not governed by associative learning (Trott et al., 2022), demonstrating a need for further analysis of this sex-dependent effect. For example, both males and females will show robust learning-dependent changes in both freezing and darting-like behavior using a modified delay conditioning paradigm in which the delay cue is preceded by another CS (Le et al., 2023). Still, given the evidence from the studies examining darting behavior reviewed above, some work suggests that females might be especially prone to developing proactive conditional responses in some situations even if this finding is far from ubiquitous.

2.2. Trace fear conditioning

Trace fear conditioning is conceptually similar to delay fear conditioning in that a discrete CS is paired with a US, but here, a brief period of time, known as a trace interval, separates the CS and US. Several studies have demonstrated that, like delay conditioning, amygdala involvement is critical for the acquisition of trace fear (Gilmartin et al., 2012; Kwapis et al., 2011; see also Kochli et al., 2015; for a detailed theoretical review on trace fear conditioning see Raybuck & Lattal, 2014).

Trace interval parameters can vary widely between procedures − from just milliseconds to half a minute. For example, a common trace fear conditioned procedure is trace eyeblink conditioning, in which a CS and US (e.g., airpuff) are separated by a very short (e.g., 250 ms; Weiss et al., 1999) interval, and animals will exhibit an eyeblink precisely timed to the expected delivery of the US. In general, the longer the interval between the CS and US, the less well-timed the conditional response will be to the CS (Ivkovich & Stanton, 2001), a finding that is especially true in situations like eyeblink conditioning where the conditional response must be appropriately timed. However, because freezing is a less precisely-timed behavior, this conditional response can withstand longer trace intervals (e.g., 20-sec) without impacting behavioral performance substantially (Chowdhury et al., 2005).

Importantly, trace fear conditioning recruits several additional brain regions that are not needed for delay conditioning, including a different role for the prelimbic region of the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). Inhibiting neural activity using muscimol before conditioning reduced trace, but not delay, fear. This effect was mirrored by blocking NMDA receptor trafficking prior to acquisition, suggesting synaptic plasticity in the PL is important for acquisition of trace conditioning (Gilmartin & Helmstetter, 2010). Further, optogenetic inhibition of neurons in the PL during the trace interval impaired trace fear acquisition (Gilmartin et al., 2013), and post-training infusions of either a broad-spectrum proteasome inhibitor (β-lactone) or a protein synthesis inhibitor (anisomycin) into the PL also disrupted trace, but not delay, conditioning (Reis et al., 2013). These latter results are in line with work demonstrating pre-training lesions of the mPFC have no effect on delay fear conditioning (Morgan et al., 1993). However, others have found that inactivation of the PL impairs delay fear expression during testing using a conditioned suppression procedure (Sierra-Mercado et al., 2011). Together, these results suggest that consolidation within the PL is important for successful storage of trace fear memory alone, but PL activity may be required for expression of both trace and delay fear memory. One explanation for the involvement of the PL in trace fear conditioning is that the PL-BLA pathway regulates learning under difficult or ambiguous circumstances (Kirry et al., 2020). Recent work has demonstrated an important role for the retrosplenial cortex (RSC) in both the acquisition (Trask et al., 2021a) and retrieval (Trask et al., 2021b) of trace fear conditioning, but not in delay fear conditioning (Kwapis et al., 2015; Trask et al., 2021b). However, delay memory can become dependent on the RSC following a long delay (e.g., 28 days; Fournier et al., 2021; Todd et al., 2016), in line with a hypothesized role for the RSC in systems-level consolidation (de Sousa et al., 2019).

Incidental encoding of the context is often studied in trace fear conditioning (Marchand et al., 2004), and some work has begun to suggest that this type of contextual encoding is distinct from learning about the CS itself. For example, Twining et al. (2020) demonstrated that optogenetic inhibition of the ventral hippocampus (VH) to BLA pathway during memory acquisition selectively impaired later memory for context without impacting CS memory. Similar results demonstrated that inhibition of distinct subregions of the RSC has similar dissociable impacts on CS− and context-elicited fear (Trask et al., 2021a) and that inactivation of the BLA prior to conditioning affects context-elicited, but not CS-elicited, fear. Together, these results suggest the memory acquired for context during trace fear conditioning is distinct from the CS memory despite being acquired together.

Although trace fear conditioning relies on a more complex neural circuit for acquisition and expression than delay fear conditioning, it can be reverted to the simpler circuit that supports delay fear in the right circumstances. For example, Kwapis et al. (2017) demonstrated that following trace fear conditioning, a brief updating session using a delay fear conditioning procedure can remove the reliance on the RSC and leave memory dependent on a less-complex amygdala-centric neural substrate for expression. One interesting finding was that temporary inactivation of the amygdala during delay, but not trace, fear acquisition reduced later memory while inactivation of the dorsal hippocampus (DH) during trace, but not delay, conditioning reduced later memory (Raybuck & Lattal, 2011). This suggests that under some circumstances, the amygdala may not be necessary for acquisition of a trace fear memory.

Other work has examined sex differences in trace fear using eyeblink conditioning and found that females are better able to precisely time the response (Dalla et al., 2009; reviewed in Dalla & Shors, 2009). However, studies examining freezing behavior during trace fear show no differences between males and females (e.g., Gould et al., 2004), in line with the work in delay fear conditioning, which shows that when freezing is the main conditional response, sex effects are unlikely to be observed.

2.3. Context fear conditioning

While contextual aspects of fear can be conditioned indirectly in both delay and trace paradigms, the context can become the main predictor of the shock itself. In context fear conditioning, shocks are presented inside the conditioning chamber without any discrete CS. In these situations, the context is the best predictor of the shock, and later placement in that context will elicit freezing on its own. While like delay conditioning, context conditioning relies heavily on the amygdala (Hoffman et al., 2015; Phillips & LeDoux, 1992) even after extended training (Maren, 1999), additional structures are recruited for its acquisition and expression. Further, in line with the sustained fear elicited by context conditioning, the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) is recruited, and lesions of this region will reduce context-induced freezing (Urien et al., 2021).

Context fear conditioning also depends crucially on the hippocampus for acquisition and expression. Phillips and LeDoux (1992) demonstrated that while lesions of the amygdala impacted delay and context fear conditioning, lesions of the hippocampus only affected context fear. This effect mirrors similar findings in humans (Marschner et al., 2008), demonstrating that the role of the dorsal hippocampus in context, but not cued, fear conditioning is well-conserved across species. Other work has found that the same optogenetic inhibition applied to either the DH or the VH has similar impacts on context fear memory, suggesting that both subregions support context fear learning (Huckleberry et al., 2018). However, the role of the hippocampus is time-limited with lesions having no impact on remote (i.e., 50 days) retrieval of the fear memory (Anagnostaras et al., 1999).

Like trace fear conditioning, context conditioning also relies on activity within the RSC for acquisition and expression (Todd et al., 2017; Trask & Helmstetter, 2022), and this remains true when memory is tested at remote (i.e., 35 days) time points (Corcoran et al., 2011). Similar to the role of the RSC in trace conditioning, the RSC seems to be immediately important in memory expression. However, the RSC maintains involvement even as the DH becomes less important for expression, and other cortical regions (like the anterior cingulate cortex; ACC) become necessary for expression (de Sousa et al., 2019; Frankland et al., 2004), suggesting a fundamental difference between how context fear is represented in the hippocampus and the retrosplenial cortex.

While some have reported increased contextual freezing in females relative to males following context fear conditioning (Keiser et al., 2017; Moore et al., 2010), others do not see consistent or robust sex differences in context fear (Bonanno et al., 2023; Urien et al., 2021). However, even in the absence of a difference in behavioral expression, it is likely that different neurobiological substrates underlie this response in males and females (Urien et al., 2021; see also Bauer, 2023).

3. Movement as an avoidance response: Two-way shuttle and wheel-run avoidance tasks

A number of tasks have been developed to study the behavioral processes and neural mechanisms of active avoidance that capitalize on the animal’s natural species-specific defense response of movement away from an aversive stimulus. In contrast to fear conditioning, in which the subject’s behavior has no influence over the stimuli delivered (e.g., the CS and US), these active avoidance paradigms include a contingency by which an overt movement response proactively prevents the occurrence of a threatening outcome.

3.1. Two-way shuttle avoidance

Two-way shuttle avoidance is the most commonly used active avoidance task. Rodents are placed in a chamber divided into two subcompartments that the subject can move between freely (Mowrer & Lamoreaux, 1942; 1945). In two-way signaled avoidance, the subject acquires a CS-US association (e.g., tone-shock) before learning that it can shuttle (cross the divided chamber in either direction) during the CS in order to prevent the US. In most cases, shuttling causes both US omission and immediate cessation of the CS (but not always, see: Smith et al., 2002; Carmona et al., 2014). In an unsignaled two-way avoidance task, the subject receives USs (shocks) at regular intervals until it shuttles (i.e., escapes), earning a safety period during which no US is delivered. If the subject continues to shuttle during the safety period (i. e., avoids), this response earns additional time free from shock (Sidman, 1953).

Lesion studies implicate the canonical amygdalar substrates of fear conditioning in two-way avoidance. Damage to either lateral amygdala (LA) or basal amygdala (BA) attenuates the expression of avoidance in both signaled and unsignaled two-way paradigms (Choi et al., 2010; Lázaro-Muñoz et al., 2010). However, LA and BA are not necessary for the long-term maintenance of two-way avoidance when lesions are placed after extended training (so-called ‘overtraining’; Lazaro-Munoz et al., 2010). This result contrasts with fear conditioning, which remains sensitive to BLA lesions, even when subjects receive far more training than is necessary to produce asymptotic levels of freezing (Zimmerman et al., 2007; also reviewed above). Thus, LA and BA seem to make a crucial but time-limited contribution to the two-way response. This is consistent with classic studies demonstrating the effect of whole-amygdala lesions on the acquisition and expression, but not long-term maintenance, of two-way shuttling in rats (Thatcher & Kimble, 1966), cats (Brady et al., 1954), and monkeys (Weiskrantz, 1956).

The key amygdalar output pathway underlying the two-way response is thought to involve nonreciprocal, excitatory projections from the BLA to the nucleus accumbens (NAc; Fudge et al., 2002; McDonald, 1991; Price, 2006). Pharmacological inactivation of the NAc shell, but not core, attenuates the expression of the two-way response (Ramirez et al., 2015). Pharmacological disconnection of the BLA and the NAc shell produces a similar effect, demonstrating that two-way avoidance requires the serial progression of information between these structures (Ramirez et al., 2015). Though the role of accumbens-projecting BLA neurons has not been tested directly in two-way avoidance, these data support a model in which excitatory drive exerted by the BLA on NAc neurons is required for the two-way avoidance response, at least through the initial stages of training (presumably until the ‘overtraining’ threshold for amygdala dropout) (Ramirez et al., 2015; for review, see Cain, 2019).

The central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA) has a contrasting role in two-way avoidance. Pre-training CeA lesions facilitate the acquisition of two-way signaled avoidance (Moscarello & LeDoux, 2013), and administration of a protein synthesis inhibitor into the CeA following the first day of two-way signaled avoidance training potentiates the response on subsequent days (Moscarello & LeDoux, 2013). CeA lesions also rescue avoidance in poor performers, or subjects that fail to express the two-way response due to excessive freezing, in both signaled and unsignaled paradigms (Choi et al., 2010; Lázaro-Muñoz et al., 2010). Two-way avoidance is thus constrained by the CeA, which supports the deeply-ingrained freezing behavior elicited by conditioned cues and contexts (Ciocchi et al., 2010; Fadok et al., 2018; Haubensak et al., 2010; Moscarello & Penzo, 2022) that predominate early in training but become suppressed as the two-way response is acquired (Choi et al., 2010; Lázaro-Muñoz et al., 2010; Moscarello & LeDoux, 2013; LaPointe et al., 2021).

The transition from freezing to two-way avoidance requires engagement of the infralimbic cortex (IL). Lesion and pharmacological inactivation of the IL increase freezing and decrease avoidance responses in the signaled two-way task (Moscarello & LeDoux, 2013). In addition, injection of a protein synthesis inhibitor into the IL following the first day of two-way avoidance training attenuates avoidance and facilitates freezing on subsequent days (Moscarello & LeDoux, 2013), suggesting that plasticity in the IL is required for the suppression of freezing. In contrast to IL, the neighboring PL has a more nuanced role in two-way avoidance. While the PL does not have a role in two-way avoidance (Moscarello & LeDoux, 2013), a modified version of this task that requires discrimination between a CS + and CS− shows PL involvement (Jercog et al., 2021). Together, these data suggest that PL is recruited in complex two-way paradigms that require subjects to discern between cues that command distinct behavioral outcomes, whereas IL seems to facilitate two-way avoidance by suppressing freezing.

The IL projects to the nucleus reuniens (RE) of the midline thalamus (McKenna & Vertes, 2004; Vertes et al., 2007), which also contributes to the suppression of freezing in two-way avoidance. Following acquisition of a signaled two-way response, pharmacological inactivation of the RE increases CS-evoked freezing (Moscarello, 2020), and chemogenetic inhibition of IL projections to the RE has an identical effect (Moscarello, 2020). These results are consistent with work using extinction-learning paradigms, in which inactivation of either RE cell bodies or prefrontal cortex projections to RE enhanced expression of freezing to an extinguished CS (Ramanathan et al., 2018; Ramanathan & Maren, 2019; Vasudevan et al., 2022). The cortical-reuniens projection may thus serve as a common pathway recruited by multiple conditioning paradigms for the suppression of defensive reactions such as freezing.

Another region of the midline thalamus, the paraventricular nucleus (PVT), projects to both the NAc shell and the CeA (Li & Kirouac, 2012; Ma et al., 2021; Vertes & Hoover, 2008), and these projections support the contrasting conditioned behaviors underpinned by each target region. PVT projections to the NAc shell become active on successful avoidance trials, whereas engagement of PVT-CeA projections predict avoidance failure (Ma et al., 2021). Optogenetic inhibition of the PVT-NAc shell pathway attenuates avoidance, and the same manipulation applied to the PVT-CeA pathway rescues poor avoiders (Ma et al., 2021). Thus, trial-to-trial differences in response (i.e., freezing or avoidance) are mediated by distinct pathways emanating from the PVT, suggesting that this region functions as a toggle that determines the success or failure of two-way avoidance. In conjunction with evidence for the role of the functional connection between basal amygdala and NAc shell, these data indicate that convergent inputs to this region of the NAc drive the two-way avoidance response.

Both the amygdala and the striatum receive dopaminergic input from the midbrain (Beier et al., 2015; Wise, 2004), and dopamine signaling in these regions makes a key contribution to two-way avoidance. Systemic administration of dopamine antagonists attenuates the two-way response, even at doses that do not cause broad locomotor deficits (Antunes et al., 2020; Fibiger & Mason, 1978; Niemegeers et al., 1969; Wise, 2004). Region-specific restoration of dopaminergic signaling in dopamine-deficient mice demonstrates that the initial stages of training in a signaled two-way paradigm require dopamine in both the amygdala and the whole striatum (both dorsal and ventral regions), whereas persistent, long-term expression of the response (i.e., ‘overtraining’) requires dopaminergic signaling in the whole striatum but not the amygdala (Darvas et al., 2011). Inactivation of neurons in the substantia nigra pars reticulata was found to have a permissive effect on two-way signaled avoidance (Hormigo et al., 2016), gating the output of this action via inhibitory projections to the pedunculopontine tegmental area (Hormigo et al., 2019). Together, these data suggest that both amygdalar and striatal dopamine are critical for the two-way avoidance response, but that dopamine signaling in each region contributes along its own timeline (potentially consistent with the idea of amygdala dropout), demonstrating that the two-way response is under the control of systems that govern complex action.

Some sex differences do exist in the ability to acquire two-way avoidance. Males require more trials to learn both signaled and unsignaled two-way avoidance compared to females (Dalla et al., 2008; Denti & Epstein, 1972; Gray & Lalljee, 1974; Shors et al., 2007; for review, see Dalla & Shors, 2009). This behavioral sex difference only seems to be present during adulthood, but not during early development or in aged rats (Bauer, 1978).

In summary, the expression of two-way avoidance requires a transition away from CeA-mediated freezing behaviors that oppose the avoidance response (Choi et al., 2010; Lázaro-Muñoz et al., 2010; Moscarello & LeDoux, 2013). This switch is mediated by IL and one of its key projection targets, the RE, which act to suppress freezing and thus facilitate two-way avoidance (Moscarello & LeDoux, 2013; Moscarello, 2020). In contrast to freezing, the two-way response seems to rely on basal amygdala projections to the NAc as the key amygdalar output (Ramirez et al., 2015), as well as dopamine signaling that permits complex motion (Darvas et al., 2011; Hormigo et al., 2016). Finally, convergent evidence suggests that the amygdalar circuitry underpinning two-way avoidance makes a time-limited contribution (Darvas et al., 2011; Lázaro-Muñoz et al., 2010), supporting the initial stages of training but becoming unnecessary for the response as training proceeds over the long term.

3.2. Wheel-run avoidance

Wheel-run avoidance is another well-established active avoidance task. Brogden and Culler (1936) developed the original apparatus and tested it with cats, guinea pigs, and rats. Later studies used a discriminative wheel-running task in which rabbits learned to rotate the wheel following presentation of a brief CS + in order to prevent delivery of the US (shock), which alternated with presentation of a CS− that signaled no outcome (Gabriel, 1968). Electrophysiological experiments using this paradigm revealed that BLA neurons in the rabbit develop discriminative firing patterns to the CS + and CS− during acquisition of the wheel-run response to the CS+ (Maren et al., 1991). However, the magnitude of the neuronal response to both the CS + and CS− gradually dissipated as training progressed despite the fact that BLA activity continued to exhibit discrimination between cues, reaching its lowest level at a long-term expression or ‘overtraining’ timepoint (Maren et al., 1991). Muscimol inactivation of the BLA impaired acquisition and expression but not long-term maintenance of avoidance in this task, illustrating a decline in the causal contribution of the amygdala that occurs in parallel with the diminution of activity (Poremba & Gabriel, 1999). This process of amygdalar dropout is similar to what has been described (see above) for two-way avoidance in rodents and other animals but has been more thoroughly documented using multiple techniques in the case of wheel-run avoidance.

The role of the BLA in wheel-run avoidance has been studied in the context of its connection with a larger cortico-thalamic system underpinning the response (Gabriel, 1993; Gabriel et al., 2003). Lesions of the whole amygdala both disrupt the acquisition of wheel-run avoidance and prevent the rapid development of discriminative cell firing in the mediodorsal thalamus and ACC (Poremba & Gabriel, 1997). Pretraining lesions of mediodorsal thalamus and ACC slow acquisition of wheel-run avoidance (Gabriel et al., 1989; 1991), though the impairments are not equal in magnitude to those induced by amygdala lesions (Poremba & Gabriel, 1997). Neurons in the posterior cingulate (another name for the RSC) also demonstrate discriminative firing to the CS + and CS−, but these responses tend to develop over a longer training period than discriminative responses in ACC neurons (Gabriel, 1993). Lesions of posterior cingulate selectively disrupt the long-term maintenance (but not the acquisition) of wheel-run avoidance (Gabriel et al., 1983; Gabriel & Sparenborg, 1987), suggesting that the neural substrate of this behavior shifts along the anterior-posterior axis of the cingulate gyrus as training proceeds (Gabriel, 1993). The transition from anterior to posterior regions of the cingulate occurs along a timeline that roughly corresponds with the dropout of the BLA (Poremba & Gabriel, 1999), which is thought to play a particular role in orchestrating discriminative activity in neural substrates recruited early in wheel-run training (Gabriel et al., 2003; Poremba & Gabriel, 1997).

Finally, it is worth nothing that selective lesions of the CeA attenuate the acquisition and expression of wheel-running avoidance in a modified paradigm to include trials in which rabbits perform an appetitive wheel-run response for water (Smith et al., 2001). Interestingly, central lesions do not influence the appetitive response in this task. Thus, despite the fact that CeA activity has been demonstrated to oppose two-way avoidance (see above), it seems to support the wheel-run response, at least in a version of the paradigm with alternating appetitive and aversive elements.

4. Instrumental conditioning of an avoidance response: Lever-press avoidance

4.1. Lever-press avoidance

Lever-press avoidance tasks are thought to be a more straightforward instrumental approach because they involve a seemingly arbitrary response thought to be unrelated to the subject’s innate repertoire of defensive behavior (Bolles, 1970), like those observed in both two-way signaled active avoidance and wheel-run avoidance. During this task, animals press a lever to prevent a shock US. Similar to two-way avoidance, this task has a signaled variant, in which the subject presses the lever during a cue in order to prevent shock and terminate the signal, and an unsignaled variant, in which lever press can both earn and prolong a time out from shock delivered at regular intervals (e.g., Campenot, 1969; Manning et al., 1974).

The role of the amygdala in lever-press avoidance has not been well-studied, and findings are inconsistent. Large lesions of the rat amygdala slow the acquisition of signaled lever-press avoidance (Campenot, 1969; Takashina et al., 1995). However, similar lesions of the amygdala have no effect on the expression of unsignaled lever-press avoidance (Manning et al., 1974), perhaps indicating a process of amygdala dropout comparable to other avoidance paradigms. However, it should be noted that selective lesions of the BLA complex were shown to have no effect on acquisition of signaled lever-press avoidance (DiCara, 1966), complicating the interpretation of the whole-amygdala lesion. Interestingly, expression of the immediate early gene cfos in the LA and BA of rats was similar across groups tested after increasing periods of signaled lever-press avoidance training (Jiao et al., 2015), agreeing with a non-effect for selective lesion of these areas. The same study demonstrated that relatively longer periods of training tested caused selective increases in cfos expression in parvalbumin-positive interneurons in the BA as well as in the intercalated cell masses of the amygdala (Jiao et al., 2015). These data may suggest that lever-press avoidance differs from other paradigms in its reliance on the amygdala, though the current evidence does not support any definitive conclusions.

Rodent mPFC makes a clearer contribution in signaled lever-press avoidance. Increased periods of signaled lever-press avoidance training lead to greater levels of cfos expression in both PL and IL, suggesting that the expression and/or long-term maintenance of the task engages these regions (Jiao et al., 2015). In a complex signaled lever-press task involving ‘active’ trials, during which lever press prevents shock, interspersed with ‘inhibitory’ trials, during which the suppression of lever press prevents shock, inactivation of PL selectively attenuated lever pressing during active trials only (Capuzzo & Floresco, 2020). In contrast, inactivation of IL interfered with both trial types, suggesting that this region can promote or prevent lever pressing according to the changing demands of the task (Capuzzo & Floresco, 2020). When this paradigm is streamlined to include active trials only, IL inactivation also decreased lever pressing, whereas PL inactivation had no effect (Capuzzo & Floresco, 2020). This is similar to results obtained from two-way signaled avoidance, in which IL is necessary for signaled avoidance expression (Moscarello & LeDoux, 2013) in tasks involving only one cue, and PL seems to be recruited when a more complex discrimination between multiple cues becomes necessary (Jercog et al., 2021; Kyriazi et al., 2020). Finally, in Wistar-Kyoto rats, which have been shown to learn lever-press avoidance more readily than other strains (Servatius et al., 2008; Stöhr et al., 1999), pre-training lesions that included both PL and IL cortices slowed but did not block acquisition of lever-press avoidance, whereas selective lesions of either region had no significant effect (Beck et al., 2014), suggesting that the combined influence of these regions facilitates avoidant behavior in animals predisposed to acquire it.

Similar to two-way avoidance, systemic administration of dopamine antagonists suppressed lever-press avoidance (Kuribara & Tadokoro, 1981). A direct comparison of the two paradigms revealed that lever-press avoidance is more sensitive to these drugs at lower doses (Kuribara & Tadokoro, 1985). Lesions specific to dopaminergic fibers revealed NAc dopamine is required for unsignaled lever-press avoidance (McCullough et al., 1993). A role for dopamine is further supported by subsecond recordings of dopamine release in the NAc core, which demonstrate that the presence or absence of a cue-evoked dopamine increase predicts the trial-to-trial success or failure, respectively, of signaled lever-press avoidance (Oleson et al., 2012). Optogenetic activation or inhibition of ventral tegmental area (VTA) dopamine neurons can either facilitate or suppress, respectively, signaled lever-press avoidance (Wenzel et al., 2018). The effect of VTA dopamine neuron activation is restricted to relatively early phases of avoidance training, when subjects are avoiding ~ 50 % of trials (Wenzel et al., 2018). Once subjects reach an 80 % avoidance criterion, the same manipulation has no effect (Wenzel et al., 2018). The changing role of dopamine may be mediated by endocannabinoid signaling in the VTA, which is thought to suppress the inhibition of dopamine neurons earlierbut not later in lever-press avoidance training (Wenzel et al., 2018).

Some studies have reported behavioral sex differences in the lever-press avoidance task. Similar to findings in two-way avoidance, females acquire lever-press faster than males with an ITI signal present (Avcu, et al., 2014; Beck et al., 2011; Radell et al., 2015). When comparing sex and strain differences, female Wistar-Kyoto rats outperform male Wistar-Kyoto and both male and female Sprague Dawley rats with a 10-sec ITI signal (but not 60-sec ITI signal), but the same study did not find any behavioral sex differences within the Sprague Dawley strain (Servatius, et al., 2015).

5. Approach/avoidance conflicts in avoidance learning: Platform-mediated avoidance

5.1. Platform-mediated avoidance

Initially designed as a modification of auditory delay fear conditioning, the platform-mediated active avoidance (PMA) task requires animals to learn that they can avoid a tone-signaled footshock by stepping onto a safe platform (Bravo-Rivera et al., 2014; Diehl, et al., 2019). Similar to conditioned suppression, this behavior comes at a cost because in most versions of the task, animals have access to a lever that delivers sucrose pellets on a variable interval (typically 30-sec) schedule of reinforcement. Across multiple days (typically 8–10 days), rats are exposed to multiple trials consisting of a 30-sec tone CS that co-terminates with a 2-sec shock US. After some trials, animals discover that they can avoid the shock US by stepping onto a platform that is positioned diagonally from the lever and reward dish, which creates a situational conflict during the onset of the tone (prior to US presentation). In this moment, the animal must decide to stop lever-pressing for the sucrose reward and move to the platform to avoid encountering the shock. After several days of training, animals typically avoid the tone-signaled shock within 6 sec of tone onset (Diehl et al., 2018). Similar to the two-way avoidance task, freezing is increased during early stages training of PMA, but decreases as avoidance training progresses, reflecting the adaptive nature of PMA. An interesting behavior that is often observed in later trials is “testing” where the the animal may go to the platform early after tone onset but will lunge toward the lever and/or place their front paws on the grid while remaining on the platform to determine if the shock is present.

Early studies sought to characterize the neural substrates of avoidance learned through the PMA task in rats with regard to how they differed from the neural substrates of conditioned fear (Bravo-Rivera et al., 2014). Following muscimol inactivation of the BLA, both freezing and avoidance decreased, demonstrating that the tone-shock association, which is stored in the BLA, is required to perform the task. Pharmacological inactivation of the NAc increased freezing but decreased avoidance, suggesting a role of the VS as an interface between emotional processing and the motor movement needed for active avoidance. Additionally, a cFos study also revealed that activation of CeA correlated with expression of PMA (Bravo-Rivera et al., 2015). Pharmacological inactivation of IL had no effect on avoidance expression (and other studies show the IL is necessary for extinction of PMA; Bravo-Rivera et al., 2015; Martínez-Rivera et al., 2019). In contrast, PL inactivation decreased avoidance but had no effect on freezing, suggesting that PL activity is key for the avoidance response in the PMA task (Bravo-Rivera et al., 2014). Follow-up studies found that pharmacological inactivation of PL delays avoidance, as most rats avoided during the expected 2-sec shock period but exhibited an increased latency to step on the platform (Diehl et al., 2018). Furthermore, using optogenetic approaches to manipulate PL activity revealed that inhibition, rather than excitation, is necessary for avoidance in the PMA task (Diehl et al., 2018).

Additional interrogation of PL circuits that regulate avoidance using optogenetic manipulations found that PL bidirectionally controls avoidance through projections to NAc (to decrease avoidance) and BLA (to increase avoidance) (Diehl et al., 2020). These findings suggested that perhaps glutamatergic PL neurons disinhibit NAc output to regulate avoidance. cFos studies also confirmed that retrieval of avoidance activated PL-BLA projection neurons but not PL-NAc neurons (Martínez-Rivera et al., 2019). A more recent study developed a novel approach combining TRAP2 and DeepCOUNT techniques to identify cell bodies and axonal projections of specific mPFC PMA circuits in mice (Gongwer et al., 2023). Fiber photometry recordings revealed that PL projections to contralateral PL neurons exhibited excitatory tone responses, whereas PL-VTA projections did not. Interestingly, PL-NAc projection neurons exhibited an early excitatory, followed by an inhibitory response as the tone progressed (Gongwer et al., 2023). Taken together with previous studies on PL activity during PMA, the excitatory tone responses observed in PL may be signaling contralateral PL neurons in addition to BLA neurons to regulate avoidance behavior. Overall, these findings suggest a dual role of PL in guiding active avoidance behaviors in which prelimbic-amygdala circuits are recruited to drive avoidance, whereas prelimbic-accumbens circuits decrease avoidance.

Other PMA studies have addressed whether overtraining may recruit different circuits when the task may become more habitual, compared to circuits initially recruited during learning of PMA, when the task is more goal-directed. Following 20 days of PMA training, 75 % of rats showed persistent avoidance, whereas only 37 % of rats showed persistent avoidance following 8 days of PMA training (Martínez-Rivera et al., 2020). cFos analysis revealed that the 8-day trained persistent avoiders showed elevated activation in PL and NAc compared to non-persistent avoiders, which differed from the 20-day trained persistent avoiders, who showed elevated activation in the insular-orbital cortex (LO/AI) and PVT) (Martínez-Rivera et al., 2020). A follow-up study investigating the functional circuitry of these regions found that optogenetically LO/AI-PL projections increased persistent avoidance, whereas optogenetically exciting this projection reduced persistent avoidance in overtrained trained rats (Martínez-Rivera et al., 2023). This suggests that avoidance circuits can shift, depending on the level of training and distinguish behaviors that are goal-directed or not.

Currently, few studies have addressed whether there are sex differences in avoidance that is learned through the PMA task. One study showed that female mice were less likely to acquire PMA compared to male mice, and subsequently were more likely to show persistent avoidance, following extinction of PMA (Halcomb et al., 2024), which contrasts findings from both two-way and lever-press avoidance tasks in which females show better avoidance responses compared to males (see above). However, another recent study showed that female rats spent more time on the platform, received fewer shocks, and pressed less during the intertrial intervals compared to male rats (Ruble et al., 2024). The likely reason for these differing results may be due to the fact that the mouse study did not include an appetitive component of lever-pressing for reward, which would likely alter the motivation to get off the platform for rodents. Future studies should further probe whether sex differences exist in the PMA task, and specifically, which behaviors and their corresponding neural circuits may differ to guide behavioral responding.

6. Overlap of circuits within conditioned fear and conditioned avoidance: What do these circuits tell us about behavior?

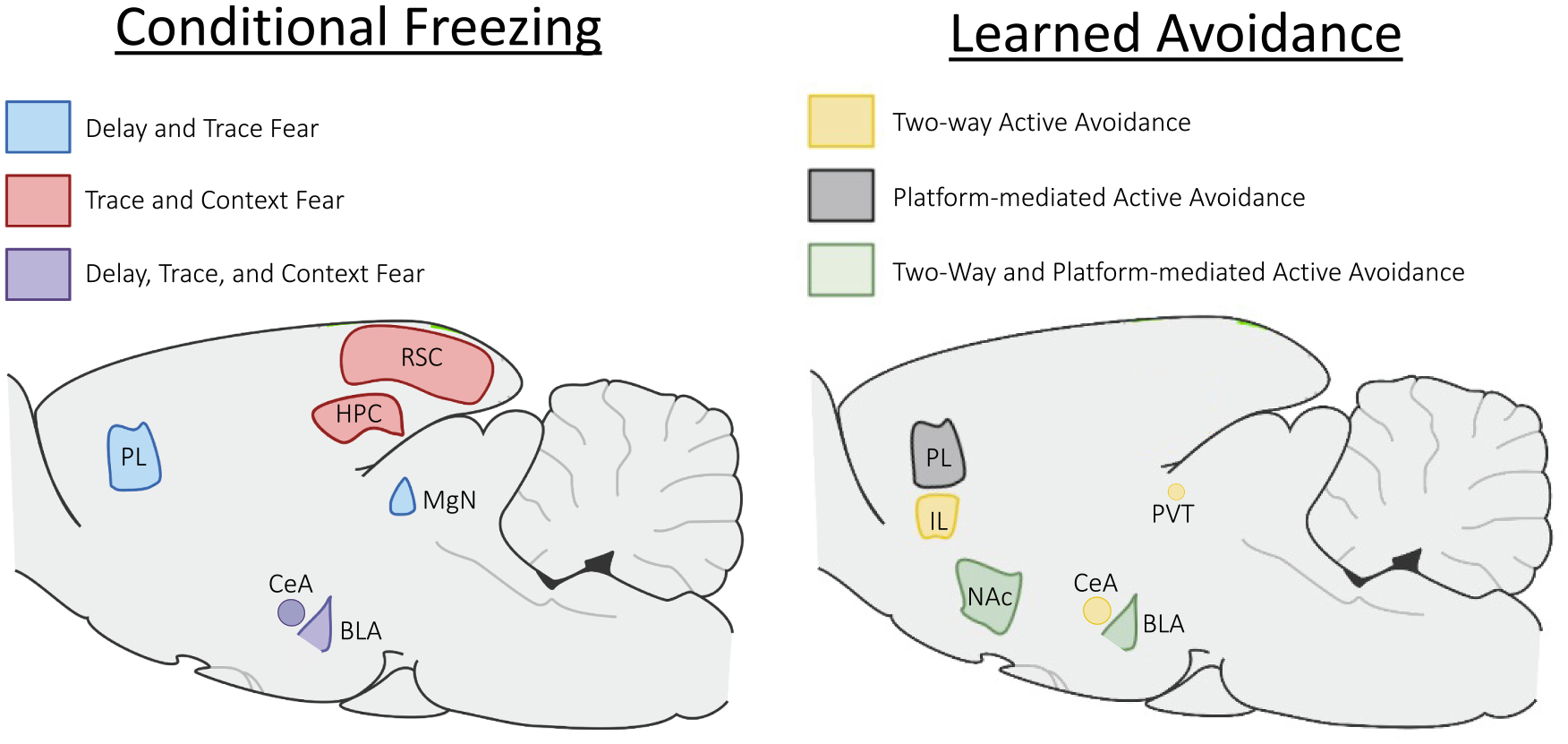

Table 1 presents a summary of the brain structures recruited across all the tasks discussed thus far in both conditioned fear and active avoidance. Fig. 1 shows some of these key structures and how they overlap within fear conditioning tasks (Fig. 1A) and active avoidance tasks (Fig. 1B). While there is significant overlap between brain structures that support reactive and proactive conditional fear responses, the most critical overlap seems to be in the BLA, which supports early learning that a CS is predictive of an aversive US. In this way, early stages of avoidance learning are similar to classical Pavlovian conditioning. However, as task demands change, and the animal learns it can either avoid or mitigate the aversive outcome, more structures are recruited into the neural circuitry that underlies behavior. Although there is a high degree of overlap between the neural circuits that support trace and context fear to those that support avoidance learning, there is much less overlap between the neural circuits that support delay fear and avoidance learning. This suggests there may be similarities between the types of learning that occur in trace/context fear and avoidance.

Table 1.

List of fear conditioning and active avoidance tasks and the neural substrates that are necessary (i.e., impair the behavioral output if lesioned or inactivated) or correlated (i.e., the neural activity is correlated, but not causal, with the behavioral output) for each task. Blanks indicate that the area has not yet been tested in the task or there are conflicting studies confirming the role of that area in the task.

| Cortical Regions | Subcortical Regions | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PL | IL | ACC | RSC | BLA | CeA | HPC | NAc | MgN | PVT | |

| Delay Fear Conditioning | Necessary Correlated | Necessary at Remote Time Points | Necessary Correlated | Necessary | Necessary | Necessary | ||||

| Trace Fear Conditioning | Necessary | Necessary | Necessary | Necessary | Necessary | |||||

| Context Fear Conditioning | Necessary | Necessary | Necessary | Necessary | ||||||

| Signaled Two-way Avoidance | Necessary | Necessary | Necessary | Necessary | Necessary | |||||

| Platform-mediated Avoidance | Necessary Correlated | Necessary | Correlated | Necessary | ||||||

| Wheel-running Avoidance | Correlated | Necessary Correlated | Necessary | |||||||

| Lever-press Avoidance | Correlated | Necessary | Necessary | |||||||

Fig. 1.

Overlapping and distinct circuits of conditioned fear and active avoidance. Conditional freezing acquired during delay and trace fear conditioning require the prelimbic cortex (PL) and medial geniculate nucleus (MgN) shown in blue, whereas trace and context fear conditioning require the retrosplenial cortex (RSC) and hippocampus (HPC) shown in red, and delay, trace, and context fear conditioning all require the basolateral amygdala (BLA) and central amygdala (CeA) shown in purple. For acquisition of learned avoidance, two-way shuttle avoidance requires the CeA, paraventricular nucleus (PVT), and infralimbic cortex (IL) shown in yellow, whereas platform-mediated avoidance requires the PL in gray, and both avoidance tasks require the BLA and Nucleus Accumbens (NAc) shown in green. We note that it is possible that more overlap exists between these circuits and may just be yet untested. It should also be noted that following long retention intervals, the RSC is needed for retrieval of delay fear (see text for details).

In delay fear conditioning, the CS has a relatively straightforward and unambiguous predictive relationship with the US. However, in other types of aversive learning (including trace/context fear and avoidance) the predictive validity of the CS is less clear. For example, in trace conditioning the trace interval interposed between the CS and US produces less fear directly to the CS and creates a more prolonged conditional response that can also become reliant on the surrounding contextual cues which may degrade the contingency between the CS and US. Similarly, in most forms of avoidance learning, as the avoidance response is acquired, the contingency between the CS and the US degrades as that animal learns to avoid the US when presented with the CS.

An important insight of avoidance research is that the neural substrates change as this complex, multi-stage form of learning progresses. Many forms of avoidance reviewed here have been demonstrated to depend on the basolateral complex through acquisition and early expression of the response (Cain, 2019; Diehl et al., 2019; one possible exception is lever press, which has produced limited, mixed results for the role of the amygdala; Manning et al., 1974; DiCara, 1966; Jiao et al., 2015). It seems that the canonical intra-amygdalar BLA-CeA pathway, which is highly implicated in fear conditioning, is engaged by the earliest stages of training (which indeed resemble fear conditioning procedures; Ciocchi et al., 2010), presumably supporting the initial acquisition of a Pavlovian association between stimuli such as a tone CS and the shock US. Acquisition of the avoidance response corresponds with a shift in the flow of information through the amygdala and beyond, from the BLA-CeA-brainstem pathway implicated in fear conditioning (Ciocchi et al., 2010) to the BLA-NAc pathway implicated in avoidance (Ramirez et al., 2015; Diehl, et al., 2020). Indirect evidence for the role of this projection in the expression of two-way avoidance has been collected using a disconnection methodology (Ramirez, et al., 2015). However, optogenetic inhibition of BLA fiber terminals in NAc demonstrates that this projection is necessary for the normal expression of PMA (Diehl et al., 2020), establishing a direct link between this pathway and an active avoidance response.

It is tempting to conclude that this toggle between amygdalar outputs is driven by instrumental learning. An early psychological theory describes reduction of a Pavlovian fear state triggered by the avoidance CS on a trial-to-trial basis as a negative reinforcer that allows for the acquisition and expression of instrumental avoidance (Mowrer & Lamoreaux, 1946). Taken at face value, this account is consistent with the recruitment of a BLA-accumbal projection that has been implicated in appetitive instrumental action (Ambroggi et al., 2008; Brit et al., 2012; Shiflett & Balleine, 2010; Stuber et al., 2011). However, there are substantial problems with a fear-reduction approach. A strong body of evidence shows that avoidance CSs lose the ability to trigger behavioral indicators of fear as the avoidance response itself becomes more robust (Choi et al., 2010; Mineka & Gino, 1980; Moscarello, 2020; Moscarello & LeDoux, 2013), making it unclear whether the activation of a central fear state is required for the response. Indeed, the observation that the subject stops producing seemingly fearful reactions to experimental apparatus and stimuli dates back to early studies of active avoidance (Kamin et al., 1963; Solomon et al., 1953). Further, the fundamental instrumentality of avoidance has been questioned. One particularly strong argument hinges on the observation that the choice of response is a primary driver of whether or not avoidance will be acquired, whereas appetitive instrumental tasks, in which totally arbitrary responses are acquired with relative ease, succeed or fail on the basis of the reinforcer (Bolles, 1970; 1975). In other words, the clearest examples of instrumentality will involve responses that are not drawn from the subject’s innate repertoire. Thus, behaviors, such as scuttling through a small aperture (i.e. the two-way response) may too closely resemble a species typical defensive response to be clearly selected by their consequences in the manner of a true instrumental action. From this perspective, the fact that avoidance behavior appears to be organized around its consequences is not enough to draw a firm conclusion. Despite this, recent findings do suggest that two-way avoidance may involve an instrumental association between shuttling and cues associated with safety (Sears et al., 2024).

Manipulations of the amygdala cease to influence avoidance, but not conditional freezing, during overtraining. Here, overtraining refers to a substantial period of training beyond the normative time to stable levels of avoidance in a given task (Lázaro-Muñoz et al., 2010; Poremba & Gabriel, 1999), but it is important to note that the differing acquisition rates of distinct avoidance tasks means that the actual number of trials or training sessions will vary widely between paradigms. For instance, 75 trials constitute overtraining in wheel-run, whereas many subjects will not acquire signaled two-way avoidance in that number of trials (Choi et al., 2010; Poremba & Gabriel, 1999). Despite this, a notable feature of both two-way and wheel-run paradigms is that overtrained avoidance responses are no longer dependent on the amygdala (Lázaro-Muñoz et al., 2010; Poremba & Gabriel, 1999). In two-way active avoidance, this effect has been documented in multiple species (Brady et al., 1954; Thatcher & Kimble, 1966; Weiskrantz, 1956). However, amygdala dropout has been most thoroughly documented in wheel-run avoidance, in which CS-elicited firing in BLA neurons increases rapidly in the early stages of training and then ramps down gradually through overtraining (though it should be noted that BLA neurons discriminate CS + and CS− throughout; Maren et al., 1991). These observations correspond with inactivation evidence demonstrating that BLA is necessary for avoidance during acquisition and expression but not overtraining (Poremba & Gabriel, 1999). This effect is not observed when delay fear conditioning is extended to a number of trials that is comparable to overtrained wheel-run avoidance (i.e. 75 trials; Maren, 2000; Zimmerman et al., 2007). Increases in BLA cell firing are retained (Maren, 2000) and disruptions of BLA function cause decreases in freezing (Zimmerman et al., 2007) following this extended form of fear conditioning. Thus, continued avoidance training seems to reduce reliance on BLA, despite the fact that this region is implicated in simpler fear conditioning paradigms no matter how much training occurs (Maren, 2000; Zimmerman et al., 2007). It is important to note that evidence for any role of the amygdala in lever-press avoidance is contradictory (Campenot, 1969; DiCara, 1966; Manning et al., 1974), and platform-mediated avoidance may not undergo amygdala dropout. Expression of cFos in multiple amygdalar nuclei did not vary significantly across 8 vs 20 days of PMA training (Martínez-Rivera et al., 2020). In addition, after 29 sessions of PMA training (the final 16 sessions were ‘high-conflict’ sessions, during which food was only available while the avoidance CS was active), rats that remained avoidant despite strong conflict showed enhanced cFos levels in LA and CeA (Bravo-Rivera et al., 2021). In contrast to wheel-run and two-way avoidance, the role of the amygdala in PMA may follow a trajectory that mirrors delay fear conditioning.

One interesting hypothesis is that BLA dropout results from the process by which an active avoidance response becomes a defensive habit (Cain, 2019). This idea is drawn from the appetitive literature, in which extensive evidence demonstrates that the mechanisms underlying instrumental action shift from goal-directed to habitual over the course of training (Balleine & O’doherty, 2010; Everitt & Robbins, 2005). Supporting this view, the transition from goal-oriented to habitual has been demonstrated in active avoidance (Sears et al., 2024). The time-limited role of BLA in avoidance is roughly consistent with results suggesting that this area contributes to appetitive instrumental behavior early on, when the response is still sensitive to the outcome devaluation procedure that distinguishes goal-directed actions (Ostlund & Balleine, 2008). Habits, on the other hand, are thought to be acquired through a gradual process of learning that generates reflexive or automatic behavioral responses (Balleine & O’doherty, 2010), which do not rely on the same BLA-dependent processes (Balleine & O’doherty, 2010). Thus, a transition from goal-directed to habitual avoidance over the course of training may explain reduced reliance on the BLA observed in wheel-run and two-way avoidance paradigms. Similar to results obtained in avoidance learning, the IL supports habitual responding (e.g., Killcross & Coutureau, 2003) obtained through overtraining (e.g., Adams & Dickinson, 1981). One explanation is that goal-directed behavior becomes inhibited through IL activity, and suppressing neural activity within the IL removes this suppression and causes goal-directed behavior to return. This is similar to the explanation of how the IL functions in extinction learning (e.g., Bouton et al., 2021): following extinction learning, IL activity actively suppresses excitatory responding and reducing this inhibition causes excitatory responding (e.g., freezing) to return.

A clever experiment with wheel-run avoidance complicates the overtraining interpretation of amygdala dropout. Time off from the task following acquisition of the response will reduce reliance on BLA to the same degree as continued training (Poremba & Gabriel, 1999). Though this result belies the idea that BLA-mediated processes are replaced by a gradual form of habit learning that occurs over prolonged training, we are unaware of any experiment in the appetitive domain that asks whether time alone is sufficient to engage habitual processes. In other words, time and not continued training could be the key variable driving a shift to habitual behavior in both appetitive and aversive domains. Further work is needed to clarify the contribution of time versus training to the development of habit.

Finally, it is important to note that the passage of time does not promote amygdala dropout in fear conditioning paradigms, which remain reliant on BLA after long intervals following initial training (Gale et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2022). Thus, introduction of the avoidance contingency recruits a system of structures beyond the canonical fear conditioning circuit, but also introduces a process by which the avoidance response, once acquired to stable levels, becomes independent of the BLA, despite the fact that this region remains crucial for conditioned behavior in streamlined fear conditioning procedures.

7. Conclusion

Thus far, studies have begun to elucidate how conditional freezing and active avoidance circuits overlap and the commonalities observed in the behavioral strategies between the two learning processes. It is well-established that the BLA is required for classical conditioning of the CS− US association that is present during both fear conditioning and early learning of active avoidance. As the learning of active avoidance shifts as training progresses, so does the neural circuitry that is needed to guide appropriate behavioral responses. Most studies are in agreement that the BLA is recruited early in avoidance, and later its necessity can “drop out” under certain situations as active avoidance training progresses. Indeed, both fear and avoidance circuits can change as contingencies or task demands change, such as during fear extinction or overtraining of active avoidance. Future studies can address how biological sex may influence behavioral output and/or the neural substrates of conditioned fear and active avoidance as well as using modern techniques to more carefully dissect the neural circuitry at different time points to gain a better understanding of how they govern these behavioral outputs.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support from NIGMS grant P20GM113109 to MMD.

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Maria M. Diehl: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. Justin M. Moscarello: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. Sydney Trask: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- Adams CD, & Dickinson A (1981). Instrumental responding following reinforcer devaluation. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section B, 33, 109–121. [Google Scholar]

- Ambroggi F, Ishikawa A, Fields HL, & Nicola SM (2008). Basolateral amygdala neurons facilitate reward-seeking behavior by exciting nucleus accumbens neurons. Neuron, 59(4), 648–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostaras SG, Maren S, & Fanselow MS (1999). Temporally graded retrograde amnesia of contextual fear after hippocampal damage in rats: Within-subjects examination. Journal of Neuroscience, 19, 1106–1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antunes GF, Gouveia FV, Rezende FS, de Jesus Seno MD, de Carvalho MC, de Oliveira CC, & Martinez RCR (2020). Dopamine modulates individual differences in avoidance behavior: A pharmacological, immunohistochemical, neurochemical and volumetric investigation. Neurobiology of Stress, 12, Article 100219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avcu P, Jiao X, Myers CE, Beck KD, Pang KC, & Servatius RJ (2014). Avoidance as expectancy in rats: Sex and strain differences in acquisition. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 8, 334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balleine BW, & O’doherty JP (2010). Human and rodent homologies in action control: Corticostriatal determinants of goal-directed and habitual action. Neuropsychopharmacology, 35, 48–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer EP (2023). Sex differences in fear responses: Neural circuits. Neuropharmacology, 222, Article 109298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer RH (1978). Ontogeny of two-way avoidance in male and female rats. Developmental Psychobiology: The Journal of the International Society for Developmental Psychobiology, 11, 103–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck KD, Jiao X, Ricart TM, Myers CE, Minor TR, Pang KC, & Servatius RJ (2011). Vulnerability factors in anxiety: Strain and sex differences in the use of signals associated with non-threat during the acquisition and extinction of active-avoidance behavior. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 35, 1659–1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck KD, Jiao X, Smith IM, Myers CE, Pang KC, & Servatius RJ (2014). ITI-Signals and prelimbic cortex facilitate avoidance acquisition and reduce avoidance latencies, respectively, in male WKY rats. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 8, 403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beier KT, Steinberg EE, DeLoach KE, Wie S, Miyamichi K, Schwarz L, Gao XJ, Kremer EJ, Malenka RC, & Luo L (2015). Circuit architecture of VTA dopamine neurons revealed by systematic input-output mapping. Cell, 162(3), 622–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolles RC (1970). Species-specific defensive reactions and avoidance learning. Psychological Review, 77, 32–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bolles RC (1975). Theory of Motivation (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GR, Met Hoxha E, Robinson PK, Ferrara NC, & Trask S (2023). Fear reduced through unconditional stimulus deflation is behaviorally distinct from extinction and differentially engages the amygdala. Biological Psychiatry Global Open Science. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, Maren S, & McNally GP (2021). Behavioral and neurobiological mechanisms of Pavlovian and instrumental extinction learning. Physiological Reviews, 101, 611–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady JV, Schreiner L, Geller I, & Kling A (1954). Subcortical mechanisms in emotional behavior: The effect of rhinencephalic injury upon the acquisition and retention of a conditioned avoidance response in cats. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 47, 179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo-Rivera C, Roman-Ortiz C, Brignoni-Perez E, Sotres-Bayon F, & Quirk GJ (2014). Neural structures mediating expression and extinction of platform-mediated avoidance. Journal of Neuroscience, 34, 9736–9742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo-Rivera C, Roman-Ortiz C, Montesinos-Cartagena M, & Quirk GJ (2015). Persistent active avoidance correlates with activity in prelimbic cortex and ventral striatum. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 9, 184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo-Rivera H, Rubio Arzola P, Caban-Murillo A, Vélez-Avilés AN, Ayala-Rosario SN, & Quirk GJ (2021). Characterizing Different Strategies for Resolving Approach-Avoidance Conflict. Frontiers in neuroscience, 15, 608922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brit JP, Benaliouad F, McDevitt RA, Stuber GD, Wise RA, & Bonci A (2012). Synaptic and behavioral profile of multiple glutamatergic inputs to the nucleus accumbens. Neuron, 76(4), 790–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brogden WJ, & Culler E (1936). Device for the motor conditioning of small animals. Science, 83, 269–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain CK (2019). Avoidance problems reconsidered. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 26, 9–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campenot RB (1969). Effect of amygdaloid lesions upon active avoidance acquisition and anticipatory responding in rats. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 69, 492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campese VD, Gonzaga R, Moscarello JM, & LeDoux JE (2015). Modulation of instrumental responding by a conditioned threat stimulus requires lateral and central amygdala. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 9, 293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capuzzo G, & Floresco SB (2020). Prelimbic and infralimbic prefrontal regulation of active and inhibitory avoidance and reward-seeking. Journal of Neuroscience, 40, 4773–4787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmona GN, Nishimura T, Schindler CW, Panlilio LV, & Notkins AL (2014). The dense core vesicle protein IA-2, but not IA-2β, is required for active avoidance learning. Neuroscience, 269, 35–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JS, Cain CK, & LeDoux JE (2010). The role of amygdala nuclei in the expression of auditory signaled two-way active avoidance in rats. Learning & Memory, 17, 139–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury N, Quinn JJ, & Fanselow MS (2005). Dorsal hippocampus involvement in trace fear conditioning with long, but not short, trace intervals in mice. Behavioral Neuroscience, 119(5), 1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciocchi S, Herry C, Grenier F, Wolff SB, Letzkus JJ, Vlachos I, & Lüthi A (2010). Encoding of conditioned fear in central amygdala inhibitory circuits. Nature, 468, 277–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran KA, Donnan MD, Tronson NC, Guzmán YF, Gao C, Jovasevic V, & Radulovic J (2011). NMDA receptors in retrosplenial cortex are necessary for retrieval of recent and remote context fear memory. Journal of Neuroscience, 31, 11655–11659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalla C, Edgecomb C, Whetstone AS, & Shors TJ (2008). Females do not express learned helplessness like males do. Neuropsychopharmacology, 33, 1559–1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalla C, Papachristos EB, Whetstone AS, & Shors TJ (2009). Female rats learn trace memories better than male rats and consequently retain a greater proportion of new neurons in their hippocampi. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106, 2927–2932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalla C, & Shors TJ (2009). Sex differences in learning processes of classical and operant conditioning. Physiology & Behavior, 97, 229–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darvas M, Fadok JP, & Palmiter RD (2011). Requirement of dopamine signaling in the amygdala and striatum for learning and maintenance of a conditioned avoidance response. Learning & Memory, 18, 136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa AF, Cowansage KK, Zutshi I, Cardozo LM, Yoo EJ, Leutgeb S, & Mayford M (2019). Optogenetic reactivation of memory ensembles in the retrosplenial cortex induces systems consolidation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116, 8576–8581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denti A, & Epstein A (1972). Sex differences in the acquisition of two kinds of avoidance behavior in rats. Physiology & Behavior, 8, 611–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dicara LV (1966). Effect of amygdaloid lesions on avoidance learning in the rat. Psychonomic Science, 4, 279–280. [Google Scholar]

- Diehl MM, Bravo-Rivera C, & Quirk GJ (2019). The study of active avoidance: A platform for discussion. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 107, 229–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl MM, Bravo-Rivera C, Rodriguez-Romaguera J, Pagan-Rivera PA, Burgos-Robles A, Roman-Ortiz C, & Quirk GJ (2018). Active avoidance requires inhibitory signaling in the rodent prelimbic prefrontal cortex. eLife, 7, e34657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl MM, Iravedra-Garcia JM, Morán-Sierra J, Rojas-Bowe G, Gonzalez-Diaz FN, Valentín-Valentín VP, & Quirk GJ (2020). Divergent projections of the prelimbic cortex bidirectionally regulate active avoidance. eLife, 9, e59281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do-Monte FH, Quiñones-Laracuente K, & Quirk GJ (2015). A temporal shift in the circuits mediating retrieval of fear memory. Nature, 519(7544), 460–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do Monte FH, Quirk GJ, Li B, & Penzo MA (2016). Retrieving fear memories, as time goes by…. Molecular Psychiatry, 21(8), 1027–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvarci S, & Pare D (2014). Amygdala microcircuits controlling learned fear. Neuron, 82, 966–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BJ, & Robbins TW (2005). Neural systems of reinforcement for drug addiction: From actions to habits to compulsion. Nature Neuroscience, 8, 1481–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadok JP, Markovic M, Tovote P, & Lüthi A (2018). New perspectives on central amygdala function. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 49, 141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanselow MS (1980). Conditional and unconditional components of post-shock freezing. The Pavlovian Journal of Biological Science: Official Journal of the Pavlovian Society, 15, 177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara NC, Cullen PK, Pullins SP, Rotondo EK, & Helmstetter FJ (2017). Input from the medial geniculate nucleus modulates amygdala encoding of fear memory discrimination. Learning & Memory, 24, 414–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fibiger HC, & Mason ST (1978). The effects of dorsal bundle injections of 6-hydroxydopamine on avoidance responding in rats. British Journal of Pharmacology, 64, 601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier DI, Cheng HY, Tavakkoli A, Gulledge AT, Bucci DJ, & Todd TP (2021). Retrosplenial cortex inactivation during retrieval, but not encoding, impairs remotely acquired auditory fear conditioning in male rats. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 185, Article 107517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankland PW, Bontempi B, Talton LE, Kaczmarek L, & Silva AJ (2004). The involvement of the anterior cingulate cortex in remote contextual fear memory. Science, 304, 881–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fudge JL, Kunishio K, Walsh P, Richard C, & Haber SN (2002). Amygdaloid projections to ventromedial striatal subterritories in the primate. Neuroscience, 110, 257–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel M (1968). Effects of intersession delay and training level on avoidance extinction and intertrial behavior. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 66(2), 412–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel M (1993). Discriminative avoidance learning: A model system. In Neurobiology of cingulate cortex and limbic thalamus: A comprehensive handbook (pp. 478–523). Boston, MA: Birkhäuser Boston. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel M, Burhans L, & Kashef A (2003). Consideration of a unified model of amygdalar associative functions. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 985, 206–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel M, Kubota Y, Sparenborg S, Straube K, & Vogt BA (1991). Effects of cingulate cortical lesions on avoidance learning and training-induced unit activity in rabbits. Experimental Brain Research, 86, 585–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel M, Lambert RW, Foster K, Orona E, Sparenborg S, & Maiorca RR (1983). Anterior thalamic lesions and neuronal activity in the cingulate and retrosplenial cortices during discriminative avoidance behavior in rabbits. Behavioral Neuroscience, 97, 675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel M, & Sparenborg S (1987). Posterior cingulate cortical lesions eliminate learning-related unit activity in the anterior cingulate cortex. Brain research, 409(1), 151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel M, Sparenborg S, & Kubota Y (1989). Anterior and medial thalamic lesions, discriminative avoidance learning, and cingulate cortical neuronal activity in rabbits. Experimental Brain Research, 76, 441–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel M, Vogt BA, Kubota Y, Poremba A, & Kang E (1991). Training-stage related neuronal plasticity in limbic thalamus and cingulate cortex during learning: A possible key to mnemonic retrieval. Behavioural Brain Research, 46, 175–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale GD, Anagnostaras SG, Godsil BP, Mitchell S, Nozawa T, Sage JR, & Fanselow MS (2004). Role of the basolateral amygdala in the storage of fear memories across the adult lifetime of rats. Journal of Neuroscience, 24, 3810–3815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmartin MR, & Helmstetter FJ (2010). Trace and contextual fear conditioning require neural activity and NMDA receptor-dependent transmission in the medial prefrontal cortex. Learning & Memory, 17, 289–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmartin MR, Kwapis JL, & Helmstetter FJ (2012). Trace and contextual fear conditioning are impaired following unilateral microinjection of muscimol in the ventral hippocampus or amygdala, but not the medial prefrontal cortex. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 97, 452–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmartin MR, Miyawaki H, Helmstetter FJ, & Diba K (2013). Prefrontal activity links nonoverlapping events in memory. Journal of Neuroscience, 33, 10910–10914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gongwer MW, Klune CB, Couto J, Jin B, Enos AS, Chen R, & DeNardo LA (2023). Brain-wide projections and differential encoding of prefrontal neuronal classes underlying learned and innate threat avoidance. Journal of Neuroscience, 43, 5810–5830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould TJ, Feiro O, & Moore D (2004). Nicotine enhances trace cued fear conditioning but not delay cued fear conditioning in C57BL/6 mice. Behavioural Brain Research, 155, 167–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA, & Lalljee B (1974). Sex differences in emotional behaviour in the rat: Correlation between open-field defecation and active avoidance. Animal Behaviour, 22, 856–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiner EM, Müller I, Norris MR, Ng KH, & Sangha S (2019). Sex differences in fear regulation and reward-seeking behaviors in a fear-safety-reward discrimination task. Behavioural Brain Research, 368, Article 111903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruene TM, Flick K, Stefano A, Shea SD, & Shansky RM (2015). Sexually divergent expression of active and passive conditioned fear responses in rats., eLife, 4, e11352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halcomb CJ, Philipp TR, Dhillon PS, Cox JH, Aguilar-Alvarez R, Vanderhoof SO, & Jasnow AM (2024). Sex divergent behavioral responses in platform-mediated avoidance and glucocorticoid receptor blockade. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 159, Article 106417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haubensak W, Kunwar PS, Cai H, Ciocchi S, Wall NR, Ponnusamy R, & Anderson DJ (2010). Genetic dissection of an amygdala microcircuit that gates conditioned fear. Nature, 468, 270–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herry C, & Johansen JP (2014). Encoding of fear learning and memory in distributed neuronal circuits. Nature Neuroscience, 17, 1644–1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman AN, Parga A, Paode PR, Watterson LR, Nikulina EM, Hammer RP Jr, & Conrad CD (2015). Chronic stress enhanced fear memories are associated with increased amygdala zif268 mRNA expression and are resistant to reconsolidation. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 120, 61–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]