Abstract

Background

To date, the focus of investigation in pediatric pulmonary embolism (PE) has been on PE recurrence and anticoagulant-related bleeding. While highly relevant, these outcomes do not fully capture functional limitations and the psychological impact that comprises post-PE syndrome.

Objectives

The primary objective of the Functional Characterization of Venous Thromboembolic Disease (FUVID) study was to investigate mechanisms of post-PE syndrome in children.

Methods

The ongoing FUVID study will prospectively enroll and systematically follow, over 12 months and with standardized pulmonary, cardiac, and muscle testing, a multicenter prospective cohort of 80 pediatric patients with first-episode PE without comorbidities. FUVID has 2 coprimary outcomes: exercise intolerance and exertional dyspnea. Exercise intolerance will be defined objectively as a percent predicted peak oxygen uptake based on ideal body weight or milliliters per minute per kilogram of lean body mass during cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Dyspnea will be objectively quantified using Borg questionnaires and defined as a mean difference of >1 at the end of the warm-up and submaximal work rates during exercise testing, simulating conditions during daily life that induce dyspnea. Pertinent secondary outcomes include anxiety, depression, and quality of life.

Conclusion

The FUVID study will investigate the relationship between symptoms (exercise intolerance and exertional dyspnea) and multiple mechanisms—hemodynamic, ventilatory, or peripheral/muscle—within the same patient at rest, submaximal exercise (simulating activities of daily living), and maximal exercise using objective measures. It will provide new evidence for selecting patients for long-term follow-up, including psychological sequelae, after PE, the modalities this follow-up should include, and the findings interpreted as indicating functional limitations after PE.

Keywords: children, pediatrics, pulmonary embolism, post–pulmonary embolism syndrome, venous thromboembolism

Essentials

-

•

Recovery in children with PE is unknown.

-

•

FUVID will provide new knowledge to screen, diagnose, and understand post-PE syndrome in children.

-

•

FUVID will test the heart, lungs and muscles under conditions of rest and exercise in children 3 and 12 months after PE.

-

•

FUVID will be the first study to study stress and anxiety and relationship with quality of life in PE.

Introduction

1. Background and Rationale

Pediatric venous thromboembolism (VTE), clinically presenting as deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism (PE), has dramatically increased and now affects 1 in 200 hospitalized children [1]. PE has experienced a more rapid rise in incidence, nearly 200%, disproportionately affecting adolescents [2]. To date, the focus of investigation in pediatric PE has been on preventing PE recurrence and anticoagulant-related bleeding [3,4]. While highly relevant, these outcomes are uncommon in children [5] and do not fully capture the functional limitations that comprise post-PE syndrome [6,7]. Exercise intolerance and dyspnea on exertion after PE are common despite anticoagulation and impact quality of life [8,9]. Up to half of adult PE and up to one-third of pediatric PE survivors report persistent dyspnea, exercise intolerance, and/or functional limitations 3 to 6 months after acute PE [10,11]. Further, psychotropic drug use increase in adolescents and young adults following VTE has been reported [12]. Existing studies on mental health after VTE highlight its association with symptoms of psychological distress, anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder, especially following PE, and correlate better with quality of life than recurrent thrombotic events and bleeding [[13], [14], [15]]. Outcomes capturing the impact of VTE, symptom burden, impact on daily activities, and the ability to return to activities, school, or work are not captured in pediatric PE studies.

There are several critical gaps in our knowledge of the post-PE functional limitations in children. The precise mechanisms underlying exercise intolerance and exertional dyspnea are unknown. Despite the similarities in the presentation of PE between adults and children [16], the etiologies associated with PE are different [17]. By extension, post-PE recovery is likely to be different but largely unknown in children. Further, how post-PE disease interacts with acquired risk factors such as sedentary lifestyle, overweight, obesity, and preexistent anxiety or depression is also unclear. Lastly, the paradox of resting tests has resulted in the conventional thinking that assumes deconditioning alone is the primary etiology of functional limitations following PE. The ongoing Functional Characterization of Venous Thromboembolic Disease (FUVID) study will prospectively enroll and systematically follow pediatric patients over 12 months. With a comprehensive program of exercise and dyspnea assessments at rest, submaximal (simulating circumstances that precipitate symptoms), and maximal exercise (peak effects) using objective measures and by quantifying psychological sequelae, the primary objective of FUVID was to investigate mechanisms of post-PE syndrome in a multicenter prospective cohort of children with first-episode PE without comorbidities.

2. Study Hypothesis

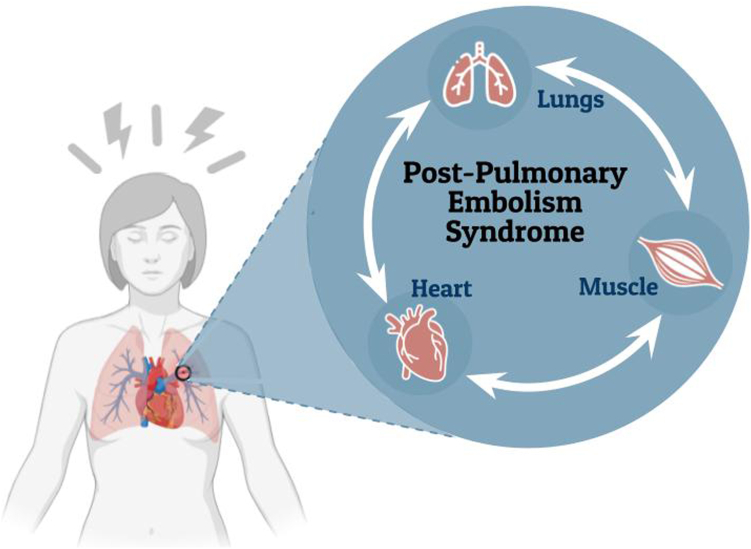

Our central hypothesis is that central (cardiac and pulmonary) and peripheral (skeletal muscle) aberrations are associated with exercise intolerance and exertional dyspnea following PE with or without deep venous thrombosis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The central hypothesis being addressed in the Functional Characterization of Venous Thromboembolic Disease study. Functional Characterization of Venous Thromboembolic Disease study’s overarching hypothesis is that central (cardiac and pulmonary) and peripheral (skeletal muscle) aberrations are associated with exercise intolerance and exertional dyspnea after pulmonary embolism.

3. Study Population and Objectives of FUVID

Eighty consecutive patients with acute symptomatic PE will be prospectively included in FUVID nationally. Recognizing that it can be challenging to obtain accurate, valid, and reproducible data across centers, FUVID is designed to bring participants to the University of Texas Southwestern (UTSW), Dallas, Texas, United States, the central testing site, from 32 external sites at 3 and 12 months after diagnosis (Figures 2 and 3). We plan to enroll all comers with PE irrespective of right ventricular dysfunction, size, or extent of pulmonary emboli. Importantly, only children without comorbidities will be enrolled to investigate the impact of PE in the absence of other dyspnea-provoking conditions (Table 1). We plan to exclude patients with comorbidities that are independently (of PE) associated with exercise intolerance and dyspnea on exertion. The primary comparison will be between PE survivors with and without exercise intolerance. To investigate the impact of cardiac maladaptation on exercise intolerance, the “cardiac aim” will determine the right ventriculoarterial coupling ratio from rest to exercise; the “pulmonary aim” will compare ventilatory efficiency at the anaerobic threshold during exercise, and the “muscle aim” will characterize skeletal muscle metabolism aberrations from rest to exercise in participants with and without exercise intolerance. We will repeat all analyses for PE survivors with or without dyspnea.

Figure 2.

Functional Characterization of Venous Thromboembolic Disease study timeline. Visit 1 procedures are completed locally at enrollment sites. Pulmonary embolism (PE) participants travel to the University of Texas Southwestern (UTSW) for visits 2 and 3 research assessments. IRB, institutional review board.

Figure 3.

Functional Characterization of Venous Thromboembolic Disease (FUVID) study schema and oversight. Participants are recruited and enrolled nationally at 32 individual centers for pulmonary embolism diagnosis (visit 1). The University of Texas Southwestern multicenter study core serves as the data and clinical coordinating center and coordinates travel to the University of Texas Southwestern at 3 and 12 months after diagnosis, which spans 3 days each, as depicted at visits 2 and 3. cMR, cardiac magnetic resonance imagining; MR, magnetic resonance imagining; PA, pulmonary artery; PRO, patient-reported outcomes; RV, right ventricle.

Table 1.

The Functional Characterization of Venous Thromboembolic Disease study eligibility criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Objectively confirmed, first-episode, symptomatic PE ± DVT | Prior history of PE or DVT |

| Age 8-21 y | No anticoagulant treatment due to contraindications |

| Willing to travel to UTSW, Dallas, Texas | Congenital heart disease with abnormal pulmonary circulation or with in situ pulmonary artery thrombosis |

| Able to comply with the exercise protocol | Chronic kidney disease |

| Chronic inflammatory or autoimmune disorder | |

| A metabolic or endocrinological disorder (eg, DM or thyroid disorders) | |

| Musculoskeletal limitations to exercise | |

| Cancer-associated PE | |

| Severe persistent or uncontrolled asthma |

DM, diabetes mellitus; DVT, deep venous thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism; UTSW, University of Texas Southwestern.

4. Study Outcomes

FUVID has 2 coprimary outcomes: exercise intolerance and exertional dyspnea. Exercise intolerance will be defined objectively as a percent predicted peak oxygen uptake (VO2) based on ideal body weight or in milliliters per minute per kilogram of lean body mass during cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) since the absolute differences between boys and girls increase with age. Sex at birth is collected for study protocols and outcomes reporting. Comparisons between groups relative to body weight (milliliters per minute per kilogram or relative physical fitness) are inappropriate with obesity [18]. Dyspnea on exertion will be objectively quantified using validated Borg questionnaires and defined as a mean difference of >1 at the end of the warm-up and submaximal work rates during CPET, simulating conditions during daily life that induce dyspnea [19]. Cardiac impairment will be defined as ventriculoarterial coupling ratio >1 in response to exercise (rest to peak intensity exercise) measured during supine exercise during cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) using an MRI-compatible ergometer [20,21]; ventilatory impairment as abnormal minute ventilation to carbon dioxide production (VE/VCO2) determined using the V slope method at the ventilatory threshold during CPET [22,23]; and muscle impairment as abnormal percent phosphocreatine (PCr) depletion (Δ %PCr) and PCr recovery time constant in response to exercise (rest to exercise) during magnetic resonance spectroscopy [24,25] (the complete list of primary and secondary outcomes of FUVID is provided in Table 2 and the Supplementary Material).

Table 2.

Functional Characterization of Venous Thromboembolic Disease study primary and secondary outcomes.

| Primary outcomes (3 mo after diagnosis) |

| 3 mo after diagnosis |

| Exercise intolerance |

| Exertional dyspnea |

| Secondary outcomes |

| 3 and 12 mo after diagnosisa |

| CTEPH |

| CTED |

| Cardiac impairment with exercise |

| Ventilatory impairment with exercise |

| Muscle impairment with exercise |

| Assessment of dyspnea at rest in 3 domainsb; during and after exercise |

| Physical activity levels and sitting times |

| Postthrombotic syndrome |

| Recurrent venous thromboembolism |

| Generic QOL and PE-specific QOL |

| Anxiety and depression |

| Thromboinflammatory biomarkers |

CTED, chronic thromboembolic disease; CTEPH, chronic thromboembolic hypertension; PE, pulmonary embolism; QOL, quality of life.

Exercise intolerance and exertional dyspnea will be measured at both 3 and 12 months after diagnosis.

Sensory, affective, and impact.

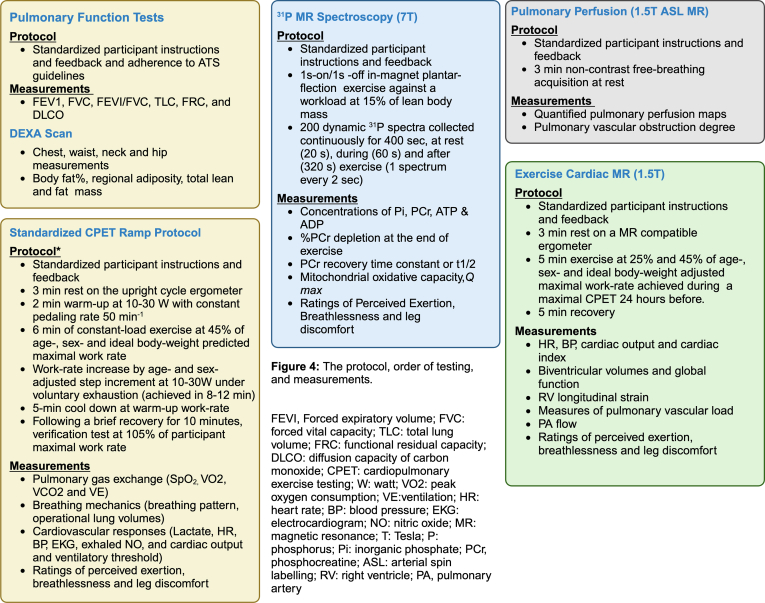

5. Study Design, Flow, and Protocol

FUVID is designed as a prospective cohort study. The study was approved by UTSW Medical Center Institutional Review Board (STU#: 2020-0868; Clinicaltrials.gov ID: NCT04583878). The study protocol does not dictate treatment decisions; patients are treated according to the American Society of Hematology pediatric VTE guidelines [26]. Participants are recruited and enrolled at individual centers within 60 days of PE diagnosis. The UTSW multicenter study core serves as the data and clinical coordinating center. There are 3 study visits (Figure 2). At visit 1 (PE diagnosis), detailed diagnosis, demographic, clinical, diagnostic, therapeutic procedures, and relevant patient-reported questionnaires are collected by local study teams and recorded in an electronic centralized database (Research Electronic Data Capture) hosted at UTSW. Imaging studies that led to diagnosis and PE risk stratification are centrally adjudicated by blinded study radiologists. For visits 2 (3 months after diagnosis) and 3 (12 months after diagnosis), participants (with 1 guardian) travel to UTSW and undergo an in-depth exercise assessment using comprehensive standardized protocols. Visits 2 and 3 each take place over 3 days at 3 different research laboratories (Figure 4). FUVID is overseen by a Steering Committee (see Supplementary Appendix S1 for composition).

Figure 4.

The study protocol, order of testing, and measurements. ADP, adenosine diphosphate; ASL, arterial spin labeling; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; ATS, American Thoracic Society; BP, blood pressure; CPET, cardiopulmonary exercise testing; DEXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry DLCO, diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide; EKG, electrocardiogram; FEV1, forced expiratory volume; FRC, functional residual capacity; FVC, forced vital capacity; HR, heart rate; MR, magnetic resonance; PA, pulmonary artery; PCr, phosphocreatine; Pi, inorganic phosphate; Q max, maximal mitochondrial oxidative capacity; RV, right ventricle; t 1/2, half-life; TLC, total lung volume; VE, ventilation; VCO2, carbon diaoxide output; VO2, peak oxygen consumption.

5.1. Cardiac assessments

The rationale for cardiac assessment is that exercise intolerance and dyspnea from cardiac limitations can be better explained by simultaneous consideration of both right ventricular performance and arterial load and the degree of matching between the 2 during exercise using modalities that take into account the asymmetric shape of the right ventricle and its function, which the current heavily relied upon methods (eg, echocardiogram) cannot [27,28]. Participants will undergo exercise cardiac MRI at 3 and 12 months after PE and perform supine exercise within the MRI bore using an MRI-compatible ergometer with adjustable electronic resistance. Cardiac imaging will be performed at rest, at 25%, and 45% of age-, sex-, and ideal body weight-adjusted peak work rate achieved during a maximal CPET performed at least 24 hours before (see pulmonary assessments). Workloads will be maintained for ∼5 minutes at each stage—3 minutes to achieve a physiological steady-state and then 2 minutes for image acquisition. The protocol includes standardized ways to simultaneously measure biventricular volumes and contractility, right ventricle longitudinal strain, focusing on right ventriculoarterial coupling, and pulmonary vascular load using methods validated against invasive measurements [20,21,29]. Optimal time points will be described to measure patient-reported outcomes, such as ratings of perceived breathlessness (RPB), perceived exertion (RPE), and perceived leg discomfort (RPLD) at each workload and during recovery [30]. We expect that exercise will unmask cardiac dysfunction not evident at rest and identify hemodynamically significant disease from a reduced contractile reserve, increased vascular load, or both.

5.2. Pulmonary or ventilatory assessments

The rationale for ventilatory assessment is that exercise in patients with persistent ventilation-perfusion mismatch after PE from persistent pulmonary thrombi will better identify a dose-response relationship between symptoms and pulmonary limitations after PE [31,32]. Participants will undergo resting pulmonary function tests followed by maximal CPET, using age- and sex-adjusted protocols. We will take several steps before exercising the participants to ensure standardized testing. We will coach participants to pedal at a continuous rate of ∼50 revolutions per minute throughout the test to reach a respiratory exchange ratio of at least 1.1. Measurements will occur during a 2-minute warm-up at 10 to 30 watts depending on age and sex, and 6 minutes of constant load exercise at 45% of age-, sex-, and ideal body weight-predicted maximal work rate. During CPET, we will measure heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, gas exchange, RPB (Borg 0-10 scale), RPE (Borg 6-20 scale), RPLD (Borg 0-10 scale) [30], and breathing mechanics. RPB, RPE, and RPLD will be measured every 2 minutes during the exercise, and the last values recorded for each interval will be used for analysis. To further add rigor, we will perform a verification test of the VO2 following a brief recovery of ∼10 to 15 minutes by a verification exercise test at 105% of the participant’s maximum work rate to confirm VO2 [33]. Baseline pulmonary function tests will be performed using standard American Thoracic Society guidelines, including forced vital capacity, forced expiratory volume, forced expiratory volume / forced vital capacity, total lung volume, functional residual capacity, and DLCO [34]. The quality of respiratory sensations experienced will be determined immediately after CPET by debriefing techniques and dyspnea questionnaires [35,36]. Participants will undergo pulmonary perfusion on a separate day using the MRI-arterial spin labeling technique to calculate pulmonary vascular obstruction (PVO) at 3 and 12 months after diagnosis [37]. We expect a spectrum of post-PE functional findings: uneventful recovery to mild pulmonary limitations to those with full-blown symptoms, residual pulmonary vascular obstruction, and significant pulmonary limitations.

5.3. Skeletal muscle assessments

The rationale for this aim is that skeletal muscle bioenergetics—depletion and recovery of muscle PCr in vivo—is associated with exercise intolerance; the association would be stronger for complete veno-occlusion and higher degrees of thromboinflammation. These 3 independent yet related mechanisms aim to understand exercise intolerance from muscle or peripheral limitations. Skeletal muscle phosphorus-31 magnetic resonance spectroscopy enables assessments of muscle PCr, a rapidly mobilizable reserve of high-energy phosphates that maintains adenosine triphosphate homeostasis in skeletal muscle that correlates with muscle biopsy [25]. For muscle assessments, participants will undergo rest and dynamic 31P-MRI studies during graded plantar flexion exercise and postexercise recovery [38]. All MRI spectra will be measured with the calf muscle (gastrocnemius and soleus) of one leg centered on the skeletal muscle phosphorus-31 magnetic resonance spectroscopy coil, followed by the other. We will measure RPE, RPB, and RPLD at rest, during, and after exercise. Measurements will include Δ %PCr, PCr recovery time-constant, and Δ %PCr divided by recovery time-constant to yield adenosine triphosphate synthesis rate to reflect mitochondrial capacity (maximal mitochondrial oxidative capacity [Q max]) [39]. We expect that skeletal muscle bioenergetics, as denoted by depletion (Δ PCr), recovery time constant (k) of PCr, and Q max, will be different in those with and without exercise intolerance and may be present in isolation or with cardiac or ventilatory limitations.

6. Sample Size Calculation and Statistical Analysis

Assuming up to 50% of unselected adult PE survivors develop post-PE syndrome (based on the available evidence at the time of study inception) and ≤5% loss to follow-up and deaths in otherwise healthy children between PE diagnosis and 3 months after diagnosis, at a 2-sided type I error of 5%, we posited we could detect a 30% cumulative incidence of low exercise capacity and/or exertional dyspnea in children with PE at 3 months after diagnosis. We will use the receiver operating characteristic approach to determine the extent to which cardiac, ventilatory, and muscle limitations predict exercise intolerance. Aalen–Johansen estimators for cumulative incidence of abnormal exercise capacity and dyspnea with corresponding 95% CIs will be calculated. We will perform secondary subgroup analyses with respect to the primary outcomes, utilizing the following subgroups: sex (male/female), thrombolysis (yes/no), PE risk category (low-risk vs intermediate/high-risk PE), and chronic thromboembolic disease (yes/no). All outcomes will be adjudicated independently by the coinvestigators blinded to clinical information.

6.1. Analysis of secondary outcomes

The cardiac endpoint is the ventriculoarterial coupling ratio in response to exercise between the groups with and without exercise intolerance (change in Ea/Emax from rest to peak intensity exercise, where Ea is an index of arterial load and Emax is an index of contractility). Based on published data, Ea/Emax of healthy controls is 0.67 (SD, 0.45), and the SD of change in Ea/Emax from rest to peak intensity is around 7% [29]. Based on a 2-sample t-test, an effect size of 0.65 can be detected with 80% power at a 5% 2-sided type I error, comparing 48 participants (60%) without exercise intolerance and 32 (40%) with exercise intolerance. Assuming an SD of 7%, the above effect size translates to a 4.5% difference in the change of Ea/Emax from rest to exercise between the 2 groups. In the scenarios where the proportion of exercise intolerance is 35% or 30%, the difference that can be detected is 4.7% or 4.9%, respectively. To explore the collective impact of exercise intensity and other demographic and clinical factors, ventriculoarterial coupling responses measured over different levels of exercise intensity will be modeled by a mixed-effect regression model, which will include patient random effects to account for correlation among observations from the same patient.

The primary endpoint for pulmonary/ventilatory limitations is ventilatory efficiency or VE/VCO2. Preliminary and published data show that the SD of VE/VCO2 is around 2.5 at the ventilatory threshold [40]. Based on the 2-sample t-test, with 80% power at a 5% 2-sided type I error, we can detect an effect size (standardized difference) of 0.65 between 48 PE patients without vs 32 PE patients (40% of the cohort) with exercise intolerance. Assuming an SD of 2.5, this effect size represents a difference of 1.63 in VE/VCO2 between the 2 groups. In the scenarios where the proportion of exercise intolerance is 35% or 30%, the difference that can be detected is 1.6 or 1.7, respectively. To explore the impact of PVO on exercise capacity on top of VE/VCO2, we will first construct a regression model with VO2 as the outcome and VE/VCO2 as the predictor. The resulting residual terms will be correlated with PVO to quantify its impact on VO2 after controlling for VE/VCO2. We will also construct mixed effect models, which include 3-month and 12-month postdiagnosis measurements as the dependent variable. It also includes patient random effects to account for within-subject correlation. We will evaluate interaction effects such as group × gender and group × time in our analyses.

The muscle endpoint is Δ %PCr between the groups with and without exercise intolerance. Based on the SD of Δ %PCr after exercise of about 8.27, based on the 2-sample t-test, we can detect a difference of 5.4 in Δ %PCr comparing 48 participants (60%) without exercise intolerance and 32 (40%) with exercise intolerance. In the scenarios of the proportion being 30% and 35%, the difference that can be detected is 5.7 or 5.5, respectively. The secondary endpoints include time to fatigue, PCr recovery time-constant, Q max and dyspnea ratings at rest, fatigue, and after exercise in participants with and without exercise intolerance. To test our hypotheses related to muscle limitations, we will fit 4 hierarchical linear regression models to evaluate the relationship of skeletal muscle bioenergetics and exercise capacity with adjustment for sex and body mass index (model 1); introduce an indicator of diagnosis of veno-occlusion (1 = partial occlusion; 2 = complete occlusion) to assess the interaction between Δ %PCr and veno-occlusion to assess whether the association between Δ %PCr and exercise capacity is stronger with complete veno-occlusion (model 2); perform similar analyses for thrombin generation, fibrinolysis capacity, and inflammatory biomarkers (model 3); and construct a full model that includes Δ %PCr, exercise capacity, and its interactions with veno-occlusion and thromboinflammation to assess the joint impact.

7. Results

Enrollment started in September 2021 and is expected to continue until June 2026. As of July 2024, 50 patients from 32 active sites across the USA have been enrolled. The median age of the first 40 enrolled patients is 16 years (IQR, 15-17), and 60% are females, and among those, 4 (10%) participants have high-risk PE, 17 (42%) have intermediate-risk PE, and 19 (48%) have low-risk PE.

8. Ethical Aspects and Data Sharing

The FUVID team will make study results available to the community of VTE scientists or those working on post-PE functional limitations to avoid unintentional duplication of research. FUVID data and associated documentation will be available to the scientific community under an National Institutes of Health–endorsed data-sharing agreement. The final dataset will include self-reported demographic, clinical, and study-specific outcome data and the statistical analysis plan. These data will be shared with investigators working under an institution with Federal Wide Assurance, with requests going directly to the FUVID principal investigator, who will decide the profiles, names, and institutions of persons either given or denied access to the data and the bases for such decisions in collaboration with the FUVID Steering Committee. These data will be available no later than 1 year after the publication of the secondary manuscripts.

9. Discussion and Innovative Features of FUVID

Despite anticoagulation and resolution of PE, limitations such as exercise intolerance and dyspnea on exertion, also termed post-PE syndrome, occur commonly, making PE an important cause of disability in children, otherwise expected to live several decades after the index event. These long-term sequelae result in a loss of approximately 1 to 2 years of healthy life and disability that is comparable with mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, and stroke in adults [9] and diabetes in adolescents [12]. Since the FUVID study’s conceptualization and initiation in 2021, the body of evidence of adult post-PE syndrome has grown [[41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48]], but the pursuit of post-PE syndrome in children has remained limited [10,49]. FUVID will provide new knowledge to screen, diagnose, and understand the mechanisms of post-PE syndrome in children with the following innovative features (Table 3):

-

•

The study will examine pathophysiologic mechanisms of exercise intolerance across the entire O2 cascade, ie, lungs, heart, and skeletal muscle, closing the scientific loop in each participant with post-PE disease.

-

•

FUVID study protocols will test the heart, lungs, and muscles under conditions of rest and during exercise, particularly during exercise levels simulating activities of daily living. Their blended application to interrogate mechanisms of pediatric post-PE syndrome is conceptually novel. The most definitive proof that a specific abnormality contributes to exercise intolerance is provided when the factor is measured during exercise.

-

•

We will evaluate exertional dyspnea and exercise intolerance using objective measures linking mechanistic factors with symptoms and patient-reported outcomes.

-

•

The FUVID study will quantify dyspnea comprehensively and systematically in 3 domains (sensory domain, dyspnea-related affective distress, and impact of dyspnea).

-

•

FUVID will be the first study to assess the trajectory of posttraumatic stress and health anxiety and the association with quality of life following pediatric PE.

-

•

We plan to enroll a multicenter cohort of PE patients from high-volume sites with no comorbidities. This approach will allow the FUVID study to tackle the limitation of previous studies, as comorbidities independent of PE are associated with exercise intolerance and dyspnea. Participants travel to UTSW, Dallas, for centralized testing to ensure rigorous, valid, and accurate research assessments.

Table 3.

Areas of innovation in the Functional Characterization of Venous Thromboembolic Disease study.

| Scientific innovation |

| Investigating the pathophysiology of post-PE functional limitations across the entire O2 cascade ie, lungs, heart, and skeletal muscle |

| Blended interrogation of mechanisms of post-PE disease at rest and during conditions of exercise (submaximal and peak exercise) |

| Association of objectively measured exercise intolerance and exertional dyspnea with patient-reported outcomes |

| Homogenous PE population with no comorbidities |

| Comprehensive assessment of dyspnea in the sensory, affective, and impact domains |

| Infrastructure |

| Centralized research assessments |

| Governance |

| Steering committee |

| Adjudication committee |

| Data monitoring committee |

| Central institutional review board |

| Study network and clinical site processes |

| Multicenter cohort |

| Data and safety capture and management |

| Quality control oversight |

| Patient-focused concierge team |

O2, oxygen; PE, pulmonary embolism.

10. Conclusions

FUVID will provide new knowledge about the pathophysiology of the pediatric post-PE syndrome and evidence on selecting patients for long-term follow-up after PE, the modalities that this follow-up should include, and the findings that should be interpreted as indicating functional limitations after PE.

Appendices

FUVID investigators: Leah M. Adix, Dallas, Texas, USA; Steven Ambrusko, Buffalo, New York, USA; Shames Alaesa, Arlington, Texas, USA; Kristen Bradley, Arkansas, Texas, USA; Brain R. Branchford, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA; Katie Carlberg, Buffalo, New York, USA; James D. Cooper, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA; Susan A. Corley, Dallas, Texas, USA; Marissa Di Miero, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA; Anna Eidenberger, St. Petersburg, Florida, USA; Edith Freyer, Chicago, Illinois, USA; Kevin Guerrero, Chicago, Illinois, USA; Arun Gurunathan, Austin, Texas, USA; Brandon Hathorn, Arlington, Texas, USA; Muhammad Khan, Dallas, Texas, USA; Shawn D. Lade, San Antonio, Texas, USA; Deanna M. Maida, San Antonio, Texas, USA; Marie Martinelli, Portland, Oregon, USA; Corey Mozingo, Dallas, Texas, USA; Raksa Moran, Dallas, Texas, USA; Sharon A. Primeaux, Dallas, Texas, USA; Leslie Raffini, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA; Rhea Robinson, Austin, Texas, USA; Cynthia Sabo, Detroit, Michigan, USA; Negin Saleh, Detroit, Michigan, USA; Anjali A. Sharathkumar, Iowa City, Iowa, USA; Rachel Simon, Chicago, Illinois, USA; Lakshmi Srivaths, Houston, Texas, USA; MacKenzie Tasset, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA; Katrina Williams, Kansas City, Missouri, USA; Rebekah Summerall Woodward, Dallas, Texas, USA

FUVID steering committee composition: Steering Committee Chair: Dr. Benjamin Levine, Dallas, Texas, USA. Steering Committee Members: Neil A. Goldenberg, St. Petersburg, Florida, USA; Frederikus A. Klok, Leiden, Netherlands; Christoph Male, Vienna, Austria; Tony G. Babb, Dallas, Texas, USA; Madhvi Rajpurkar, Detroit, Michigan, USA; Song Zhang, Dallas, Texas, USA.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to all the research staff at UTSW research laboratories, external investigators and their teams, and patients and their families who have invested their time in making the FUVID Program a success.

Funding

A. Z.is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (1R01HL153963) and the American Heart Association (20IPA35320263). The funding sources were not involved in the study design, analysis, and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author contributions

The study was conceptualized and designed by A.Z., M.D.N., J.R., S.Z., and T.G.B.. A.Z. wrote the manuscript, and all authors critically reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Relationship disclosure

There are no competing interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Handling Editor: Dr Fionnuala Ní Áinle

The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpth.2024.102669

Contributor Information

Ayesha Zia, Email: Ayesha.zia@utsouthwestern.edu.

FUVID Investigators:

Leah M. Adix, Steven Ambrusko, Shames Alaesa, Kristen Bradley, Brain R. Branchford, Katie Carlberg, James D. Cooper, Susan A. Corley, Marissa Di Miero, Anna Eidenberger, Edith Freyer, Kevin Guerrero, Arun Gurunathan, Brandon Hathorn, Muhammad Khan, Shawn D. Lade, Deanna M. Maida, Marie Martinelli, Corey Mozingo, Raksa Moran, Sharon A. Primeaux, Leslie Raffini, Rhea Robinson, Cynthia Sabo, Negin Saleh, Anjali A. Sharathkumar, Rachel Simon, Lakshmi Srivaths, MacKenzie Tasset, Katrina Williams, Rebekah Summerall Woodward, Benjamin Levine, Neil A. Goldenberg, Frederikus A. Klok, Christoph Male, Tony G. Babb, Madhvi Rajpurkar, and Song Zhang

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Raffini L., Huang Y.S., Witmer C., Feudtner C. Dramatic increase in venous thromboembolism in children’s hospitals in the United States from 2001 to 2007. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1001–1008. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carpenter S.L., Richardson T., Hall M. Increasing rate of pulmonary embolism diagnosed in hospitalized children in the United States from 2001 to 2014. Blood Adv. 2018;2:1403–1408. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017013292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldenberg N.A., Kittelson J.M., Abshire T.C., Bonaca M., Casella J.F., Dale R.A., et al. Effect of anticoagulant therapy for 6 weeks vs 3 months on recurrence and bleeding events in patients younger than 21 years of age with provoked venous thromboembolism: the Kids-DOTT randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2022;327:129–137. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.23182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Brien S.H., Zia A. Hemostatic and thrombotic disorders in the pediatric patient. Blood. 2022;140:533–541. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020006477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldenberg N.A., Knapp-Clevenger R., Manco-Johnson M.J., Mountain States Regional Thrombophilia Group Elevated plasma factor VIII and D-dimer levels as predictors of poor outcomes of thrombosis in children. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1081–1088. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klok F.A., Barco S., Siegerink B. Measuring functional limitations after venous thromboembolism: a call to action. Thromb Res. 2019;178:59–62. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2019.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kahn S.R., Hirsch A.M., Akaberi A., Hernandez P., Anderson D.R., Wells P.S., et al. Functional and exercise limitations after a first episode of pulmonary embolism: results of the ELOPE prospective cohort study. Chest. 2017;151:1058–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahn S.R., Akaberi A., Granton J.T., Anderson D.R., Wells P.S., Rodger M.A., et al. Quality of life, dyspnea, and functional exercise capacity following a first episode of pulmonary embolism: results of the ELOPE cohort study. Am J Med. 2017;130:990.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.03.033. 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farmakis I.T., Barco S., Mavromanoli A.C., Agnelli G., Cohen A.T., Giannakoulas G., et al. Cost-of-illness analysis of long-term health care resource use and disease burden in patients with pulmonary embolism: insights from the PREFER in VTE Registry. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.122.027514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parker M., Greer J., Reddy S.V., Bano M., Al-Qahtani M., Dillenbeck J., et al. Exercise capacity following pulmonary embolism in children and adolescents. CHEST Pulmonary. Published online June 8, 2024 doi: 10.1016/j.chpulm.2024.100073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keller K., Tesche C., Gerhold-Ay A., Nickels S., Klok F.A., Rappold L., et al. Quality of life and functional limitations after pulmonary embolism and its prognostic relevance. J Thromb Haemost. 2019;17:1923–1934. doi: 10.1111/jth.14589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Højen A.A., Søgaard M., Melgaard L., Lane D.A., Sørensen E.E., Goldhaber S.Z., et al. Psychotropic drug use following venous thromboembolism versus diabetes mellitus in adolescence or young adulthood: a Danish nationwide cohort study. BMJ Open. 2019;9 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tzeng N.S., Chung C.H., Chang S.Y., Yeh C.B., Lu R.B., Chang H.A., et al. Risk of psychiatric disorders in pulmonary embolism: a nationwide cohort study. J Investig Med. 2019;67:977–986. doi: 10.1136/jim-2018-000910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jørgensen H., Horváth-Puhó E., Laugesen K., Brækkan S.K., Hansen J.B., Sørensen H.T. Venous thromboembolism and risk of depression: a population-based cohort study. J Thromb Haemost. 2023;21:953–962. doi: 10.1016/j.jtha.2022.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Højen A.A., Dreyer P.S., Lane D.A., Larsen T.B., Sørensen E.E. Adolescents’ and young adults’ lived experiences following venous thromboembolism: “it will always lie in wait.”. Nurs Res. 2016;65:455–464. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldenberg N.A. Long-term outcomes of venous thrombosis in children. Curr Opin Hematol. 2005;12:370–376. doi: 10.1097/01.moh.0000160754.55131.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rajpurkar M., Biss T., Amankwah E.K., Martinez D., Williams S., Van Ommen C.H., et al. Pulmonary embolism and in situ pulmonary artery thrombosis in paediatrics. A systematic review. Thromb Haemost. 2017;117:1199–1207. doi: 10.1160/TH16-07-0529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhammar D.M., Adams-Huet B., Babb T.G. Quantification of cardiorespiratory fitness in children with obesity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51:2243–2250. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borg E., Kaijser L. A comparison between three rating scales for perceived exertion and two different work tests. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2006;16:57–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2005.00448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beaudry R.I., Samuel T.J., Wang J., Tucker W.J., Haykowsky M.J., Nelson M.D. Exercise cardiac magnetic resonance imaging: a feasibility study and meta-analysis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2018;315:R638–R645. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00158.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.La Gerche A., Claessen G., Van de Bruaene A., Pattyn N., Van Cleemput J., Gewillig M., et al. Cardiac MRI: a new gold standard for ventricular volume quantification during high-intensity exercise. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:329–338. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.980037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guazzi M., Arena R., Halle M., Piepoli M.F., Myers J., Lavie C.J. 2016 Focused update: clinical recommendations for cardiopulmonary exercise testing data assessment in specific patient populations. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:1144–1161. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beaver W.L., Wasserman K., Whipp B.J. A new method for detecting anaerobic threshold by gas exchange. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1986;60:2020–2027. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.60.6.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pipinos I.I., Shepard A.D., Anagnostopoulos P.V., Katsamouris A., Boska M.D. Phosphorus 31 nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy suggests a mitochondrial defect in claudicating skeletal muscle. J Vasc Surg. 2000;31:944–952. doi: 10.1067/mva.2000.106421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lanza I.R., Bhagra S., Nair K.S., Port J.D. Measurement of human skeletal muscle oxidative capacity by 31P-MR spectroscopy: a cross-validation with in vitro measurements. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;34:1143–1150. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monagle P., Cuello C.A., Augustine C., Bonduel M., Brandão L.R., Capman T., et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 Guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: treatment of pediatric venous thromboembolism. Blood Adv. 2018;2:3292–3316. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018024786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dandel M., Hetzer R. Echocardiographic assessment of the right ventricle: impact of the distinctly load dependency of its size, geometry and performance. Int J Cardiol. 2016;221:1132–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dandel M., Hetzer R. Evaluation of the right ventricle by echocardiography: particularities and major challenges. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2018;16:259–275. doi: 10.1080/14779072.2018.1449646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanz J., García-Alvarez A., Fernández-Friera L., Nair A., Mirelis J.G., Sawit S.T., et al. Right ventriculo-arterial coupling in pulmonary hypertension: a magnetic resonance study. Heart. 2012;98:238–243. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borg G.A. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1982;14:377–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Kan C., van der Plas M.N., Reesink H.J., van Steenwijk R.P., Kloek J.J., Tepaske R., et al. Hemodynamic and ventilatory responses during exercise in chronic thromboembolic disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152:763–771. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2016.05.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pesavento R., Filippi L., Palla A., Visonà A., Bova C., Marzolo M., et al. Impact of residual pulmonary obstruction on the long-term outcome of patients with pulmonary embolism. Eur Respir J. 2017;49 doi: 10.1183/13993003.01980-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhammar D.M., Stickford J.L., Bernhardt V., Babb T.G. Verification of maximal oxygen uptake in obese and nonobese children. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017;49:702–710. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Culver B.H., Graham B.L., Coates A.L., Wanger J., Berry C.E., Clarke P.K., et al. Recommendations for a standardized pulmonary function report. An official American Thoracic Society technical statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:1463–1472. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201710-1981ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parshall M.B., Schwartzstein R.M., Adams L., Banzett R.B., Manning H.L., Bourbeau J., et al. An official American Thoracic Society statement: update on the mechanisms, assessment, and management of dyspnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:435–452. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-2042ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watson D., Clark L.A., Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greer J.S., Maroules C.D., Oz O.K., Abbara S., Peshock R.M., Pedrosa I., et al. Non-contrast quantitative pulmonary perfusion using flow alternating inversion recovery at 3T: a preliminary study. Magn Reson Imaging. 2018;46:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wedekind M.F., Warren P., Shah S., Kumar R. Mesoaortic compression of a left-sided inferior vena-cava presenting as recurrent pulmonary embolism in a child-a novel anatomic thrombophilia? Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65 doi: 10.1002/pbc.26986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ren J., Shang T., Sherry A.D., Malloy C.R. Unveiling a hidden 31 P signal coresonating with extracellular inorganic phosphate by outer-volume-suppression and localized 31 P MRS in the human brain at 7T. Magn Reson Med. 2018;80:1289–1297. doi: 10.1002/mrm.27121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Albaghdadi M.S., Dudzinski D.M., Giordano N., Kabrhel C., Ghoshhajra B., Jaff M.R., et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing in patients following massive and submassive pulmonary embolism. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Valerio L., Mavromanoli A.C., Barco S., Abele C., Becker D., Bruch L., et al. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension and impairment after pulmonary embolism: the FOCUS study. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:3387–3398. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Konstantinides S.V., Barco S., Rosenkranz S., Lankeit M., Held M., Gerhardt F., et al. Late outcomes after acute pulmonary embolism: rationale and design of FOCUS, a prospective observational multicenter cohort study. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;42:600–609. doi: 10.1007/s11239-016-1415-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Farmakis I.T., Valerio L., Barco S., Christodoulou K.C., Ewert R., Giannakoulas G., et al. Functional capacity and dyspnea during follow-up after acute pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2024;22:163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jtha.2023.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Farmakis I.T., Valerio L., Barco S., Alsheimer E., Ewert R., Giannakoulas G., et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing during follow-up after acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Respir J. 2023;61 doi: 10.1183/13993003.00059-2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alizadehasl A., Farrashi M., Naghsbandi M., Khansari N., Moosavi J., Shafe O., et al. Post-pulmonary embolism impairment six months after acute pulmonary embolism: a prospective registry. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2023;57:665–672. doi: 10.1177/15385744231165152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morris T.A., Fernandes T.M., Channick R.N. Evaluation of dyspnea and exercise intolerance after acute pulmonary embolism. Chest. 2023;163:933–941. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2022.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Danielsbacka J.S., Olsén M.F., Hansson P.O., Mannerkorpi K. Lung function, functional capacity, and respiratory symptoms at discharge from hospital in patients with acute pulmonary embolism: a cross-sectional study. Physiother Theory Pract. 2018;34:194–201. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2017.1377331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Habedank D., Opitz C., Karhausen T., Kung T., Steinke I., Ewert R. Predictive capability of cardiopulmonary and exercise parameters from day 1 to 6 months after acute pulmonary embolism. Clin Med Insights Circ Respir Pulm Med. 2018;12 doi: 10.1177/1179548418794155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bastas D., Brandão L.R., Vincelli J., Wilson D., Perrem L., Guerra V., et al. Long-term outcomes of pulmonary embolism in children and adolescents. Blood. 2024;143:631–640. doi: 10.1182/blood.2023021953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.