Abstract

ETEC is an underrecognized but extremely important cause of diarrhea in the developing world where there is inadequate clean water and poor sanitation. It is the most frequent bacterial cause of diarrhea in children and adults living in these areas and also the most common cause of traveler's diarrhea. ETEC diarrhea is most frequently seen in children, suggesting that a protective immune response occurs with age. The pathogenesis of ETEC-induced diarrhea is similar to that of cholera and includes the production of enterotoxins and colonization factors. The clinical symptoms of ETEC infection can range from mild diarrhea to a severe cholera-like syndrome. The effective treatment of ETEC diarrhea by rehydration is similar to treatment for cholera, but antibiotics are not used routinely for treatment except in traveler's diarrhea. The frequency and characterization of ETEC on a worldwide scale are inadequate because of the difficulty in recognizing the organisms; no simple diagnostic tests are presently available. Protection strategies, as for other enteric infections, include improvements in hygiene and development of effective vaccines. Increases in antimicrobial resistance will dictate the drugs used for the treatment of traveler's diarrhea. Efforts need to be made to improve our understanding of the worldwide importance of ETEC.

INTRODUCTION

Acute infectious diarrhea is the second most common cause of death in children living in developing countries, surpassed only by acute respiratory diseases accounting for approximately 20% of all childhood deaths (96). The major etiologic agents that account for the estimated 1.5 million deaths per year are enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC), rotavirus, Vibrio cholerae, and Shigella spp. (88, 96); all are known to be endemic in essentially all developing countries. Whereas V. cholerae, Shigella spp., and rotavirus can be readily detected by standard assays, ETEC is more difficult to recognize and therefore is often not appreciated as being a major cause of either infantile diarrhea or of cholera-like disease in all age groups. Since ETEC is a major cause of traveler's diarrhea in persons who travel to these areas, the organism is regularly imported to the developed world (18, 58, 75).

Among the six recognized diarrheagenic categories of Escherichia coli (118), ETEC is the most common, particularly in the developing world (214). Specific virulence factors such as enterotoxins and colonization factors differentiate ETEC from other categories of diarrheagenic E. coli. ETEC belongs to a heterogeneous family of lactose-fermenting E. coli, belonging to a wide variety of O antigenic types, which produce enterotoxins, which may be heat labile and/or heat stable, and colonization factors which allow the organisms to readily colonize the small intestine and thus cause diarrhea (118, 155, 211).

This review summarizes data on the recognition and importance of ETEC diarrhea in developing countries, emphasizing on its prevalence, toxin types, colonization factors, and morbidity in different population groups at risk. We have reviewed information on ETEC since its discovery almost 50 years ago (43) and used clinical and laboratory data from hospital and community-based studies around the world, in both urban and rural settings, to present a comprehensive picture of ETEC-mediated diarrheal disease with regard to epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention through the use of vaccines. We hope that this review may increase the knowledge and awareness of the importance of ETEC infections, particularly in the developing world.

HISTORICAL ASPECTS

From Discovery to Present Understanding of Public Health Importance

E. coli was first suspected as being a cause of children's diarrhea in the 1940s, when nursery epidemics of severe diarrhea were found to be associated with particular serotypes of E. coli (27). These specific serotypes, designated enteropathogenic E. coli, were epidemiologically incriminated as the cause of the outbreaks. Studies of rabbit ileal loops with these strains in 1961 (199) showed only a poor correlation of fluid accumulation with the incriminated E. coli serotypes and were not definitive. Later, however, in volunteer experiments it was confirmed that ingestion of large numbers of these organisms resulted in diarrhea, and the ingested strains were recovered in the feces (98). Extensive work has been done with this group of enteropathogenic E. coli and has recently been reviewed (118).

The history of enterotoxigenic E. coli begins in 1956 in Calcutta (43). De and his colleagues injected live strains of E. coli, isolated from children and adults with a cholera-like illness, into isolated ileal loops of rabbits and found that large amounts of fluid accumulated in the loops, similar to that seen with Vibrio cholerae. However, they did not test the filtrates of these cultures to determine whether they produced an enterotoxin. These findings were not followed up until 1968, when Sack reported studies, also in Calcutta, of adults and children with a cholera-like illness, who had almost pure growth of E. coli in both stool and the small intestine (154). These E. coli isolates were found to produce a strong cholera-like secretory response in rabbit ileal loops, both as live cultures and as culture filtrates (74). The patients were also found to have antitoxin responses to the heat-labile enterotoxin produced by these organisms (163). At about the same time, similar studies were being done with animals that also demonstrated strains of E. coli to be responsible for diarrheal disease in several animal species: pigs, calves, and rabbits (80, 177, 178). Studies of these animal enterotoxigenic E. coli paralleled and sometimes preceded those done with human strains; these organisms were also found to produce enterotoxins and specific colonization factors.

These findings from Calcutta were soon confirmed by oral challenge of human volunteers (49, 100) and by corroboration of studies in Dhaka, Bangladesh (61, 113, 117, 149). ETEC were shown in these studies to be most frequently found in children; such findings have been subsequently corroborated in multiple studies in developing countries (23, 24). Thus, in most studies in the developing world, ETEC have been shown to be the most common bacterial enteric pathogen, accounting for approximately 20% of cases, as shown in Table 1, which summarizes findings from some of the more detailed studies done in several different countries.

TABLE 1.

Enterotoxin profiles and presence of colonization factors in enterotoxigenic E. coli strains isolated from symptomatic children in different regions of the worlda

| Parameter | Bangladesh | Mexico | Peru | Egypt | Argentina | India | Nicaragua |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence of ETEC (% of subjects) | 18 | 33 | 7.4 | 20 | 18.3 | 12-24 | 38 |

| Toxin profile (% of subjects) | |||||||

| ST | 50 | 19 | 31 | 53 | 40 | 32 | 32 |

| LT/ST | 25 | 57 | 13 | 34 | 7 | 27 | 49 |

| LT | 25 | 41 | 56 | 13 | 53 | 41 | 19 |

| Prevalence of CF (%) | 56b | 21 | NT | 24 | 55 | 76 | 61 |

| No. of subjects tested | 435a, 662b | 75c | 377d | 242e, 211f | 145g | 1,220h | 235i |

Data are from Bangladesh (24[a], 132[b]), Mexico (38[c]), Peru (19[d]), Egypt (1[e], 139[f]), Argentina (207[g]), India (180[h]), and Nicaragua (126[i]). NT, not tested.

BIOLOGY

LT and ST Enterotoxins

Following the initial discovery of ETEC in humans, there was an intensive effort to further characterize its mechanisms of pathogenesis and means of laboratory identification. Over a period of several years, its major virulence mechanisms were identified. ETEC produce one or both of two enterotoxins, heat-labile enterotoxin (LT) and heat-stable enterotoxin (ST), that have been fully characterized, cloned, and sequenced, and their genetic control in transmissible plasmids was identified (70, 138, 179). ETEC also produces one more of many defined colonization factors (pili/fimbrial or nonfimbrial), also under plasmid control (65, 66). The full sequence of laboratory events leading to the better understanding of virulence factors in ETEC has been reviewed in a number of publications (66, 157, 116, 118, 158, 211) and will not be elucidated further in this article. Only a brief summary of the actions of these two enterotoxins will be given.

LT was found to be very similar physiologically, structurally, and antigenically to cholera toxin and to have a similar mode of action. The molecular mass (84 kDa) and the subunit structure of the two toxins were essentially identical, with an active (A) subunit surrounded by five identical binding (B) subunits (70, 83). Following colonization of the small intestine by ETEC and release of the LT, the LTB subunits bind irreversibly to GM1 ganglioside, and the A subunit activates adenylate cyclase, which results in increases in cyclic AMP, which stimulates chloride secretion in the crypt cells and inhibits neutral sodium chloride in the villus tips. When these actions exceed the absorptive capacity of the bowel, purging of watery diarrhea results (70).

ST is a nonantigenic low-molecular-weight peptide, consisting of 18 to 19 amino acids. There are two variants, STp and STh, named from their initial discovery from pigs and humans, respectively, and which have identical mechanisms of action. Released in the small intestine, ST binds reversibly to guanylate cyclase, resulting in increased levels of cyclic GMP (138). ST has also been implicated in the control of cell proliferation via elevation of intracellular calcium levels (174). As with LT, chloride secretion by the crypt cells is then increased and inhibition of neutral sodium chloride absorption occurs, leading to outpouring of diarrheal stool. The relative proportions of LT, ST, and LT/ST toxin-producing ETEC seems to vary from one geographic area to another in patients with ETEC diarrhea or asymptomatic carriers (Tables 1, 2, and 3). The rate of isolation from asymptomatic children has varied between 0% and 20% in numerous studies carried out with children in different settings but has in most instances been lower than the rates in children with diarrhea (7, 8, 19, 38, 79, 88, 143). On average ETEC is seen at least two to three times more frequently in symptomatic than asymptomatic children (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Examples of case-control studies of symptomatic versus asymptomatic children infected with ETEC of different toxin types

| Study area | Yr | Method useda | Toxin type | No. of subjects (% positive)

|

P | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Controls | ||||||

| Sao Paulo, Brazil | 1982 | A | N | 245 | 96 | 143 | |

| LT only | 3.3% | 11.4% | <.01 | ||||

| LT/ST | 4.9% | 0 | 0.0175 | ||||

| ST only | 4.9% | 0 | 0.0175 | ||||

| All ETEC cases | 13% | 11% | ns | ||||

| Ethiopia | 1982 | A | N | 86 | 60 | 184 | |

| LT only | 11% | 3% | <0.05 | ||||

| LT/ST | 11% | 7% | ns | ||||

| ST only | 4% | 0 | ns | ||||

| All ETEC cases | 23% | 10% | <0.05 | ||||

| New Caledonia | 1993 | B | N | 488 | 88 | 13 | |

| LT only | 1% | 0 | ns | ||||

| LT/ST | 0.4% | 0 | ns | ||||

| ST only | 3.4% | 0 | ns | ||||

| All ETEC cases | 5.36% | 0 | 0.031 | ||||

| Arizona | 1995 | A | N | 1042 | 1059 | 167 | |

| LT only | 3.1% | 1.1% | <0.05 | ||||

| LT/ST | 1.3% | 0.2% | <0.05 | ||||

| ST only | 3.2% | 0.7% | <0.001 | ||||

| All ETEC cases | 7.5% | 3.2% | <0.001 | ||||

| Bangladesh | 1999 | B | N | 814 | 814 | 7 | |

| LT only | 4.6% | 5% | 0.64 | ||||

| LT/ST | 3.9% | 1.6% | 0.004 | ||||

| ST only | 8.4% | 2.2% | 0.0001 | ||||

| All ETEC cases | 16.8% | 8.8% | 0.0001 | ||||

| Argentinab | 1999 | C | N | 371 | 595 | 207 | |

| LT only | 9.7% | 9.8% | ns | ||||

| LT/ST | 1.3% | 1.2% | ns | ||||

| ST only | 7.3% | 1.7% | <0.001 | ||||

| All ETEC isolates | 18.5% | 13.3% | <0.05 | ||||

| Egyptb | 1999 | C | N | 628 | 1027 | 1 | |

| LT only | 10.7% | 8.5% | ns | ||||

| LT/ST | 2.6% | 3.9% | ns | ||||

| ST only | 14.5% | 6.9% | <0.01 | ||||

| All ETEC isolates | 30.1% | 19.4% | <0.01 | ||||

The assays used for detection of enterotoxins on ETEC were adrenal cell and infant mouse (A), DNA probes (B), and GM-1 ELISA (C).

Based on number of specimens analyzed; the rest are based on number of subjects tested.

TABLE 3.

Toxin profile of ETEC strains isolated from children with diarrhea selected during different years in various developing countries

| Country | Yr | No. of strains | % of strains producing:

|

Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LT | ST | LT and ST | ||||

| Bangladesh | 1980 | 88 | 4 | 34 | 62 | 113 |

| 1992 | 48 | 58 | 38 | 4 | 11 | |

| 1995 | 54 | 15 | 57 | 28 | 8 | |

| 1999 | 137 | 27 | 50 | 23 | 7 | |

| 2000 | 662 | 27 | 48 | 25 | 132 | |

| 2004 | 727 | 20 | 66 | 14 | 215 | |

| Thailand | 1983 | 35 | 23 | 69 | 9 | 52 |

| 1989 | 112 | 39 | 36 | 25 | 55 | |

| 1997 | 107 | 49 | 27 | 24 | 120 | |

| Mexico | 1988 | 31 | 19 | 32 | 49 | 37 |

| 1990 | 241 | 34 | 39 | 27 | 103 | |

| Nicaragua | 1997 | 310 | 24 | 34 | 42 | 126 |

| Argentina | 1991 | 109 | 21 | 65 | 14 | 16 |

| 1999 | 68 | 53 | 40 | 7 | 207 | |

| Egypt | 1993 | 57 | 21 | 35 | 44 | 212 |

| 1999 | 107 | 31 | 47 | 22 | 128 | |

| 2003 | 933 | 26 | 58 | 16 | 139 | |

| Guinea Bissaua | 2002 | 1018 | 56 | 18 | 26 | 183 |

ETEC from children with diarrhea or asymptomatic carriers.

Colonization Factors

More than 22 colonization factors (CFs) have been recognized among human ETEC and many more are about to be characterized (66). The CFs are mainly fimbrial or fibrillar proteins, although some CFs are not fimbrial in structure (60, 61, 66). Notable among these is CS6, an antigen increasingly being isolated in recent studies. The CFs allows the organisms to colonize the small bowel, thus allowing expression of either or both LT and ST in close proximity to the intestinal epithelium. Studies with humans as well as experimental animals have shown that CF-positive bacteria but not their isogenic CF-negative mutants colonize and induce diarrhea (60, 66, 100, 195).

A nomenclature for the CFs designating them as coli surface antigen (CS) was introduced in the mid-1990s (66). A list showing the old and new classifications of the CFs can be seen in Table 4. All except CFA/I have the CS designation in the present designation. Some of the better-characterized CFs can be subdivided into different families, i.e., the colonization factor I-like group (including CFA/I, CS1, CS2, CS4, CS14, and CS17) (66) and the coli surface 5-like group (with CS5, CS7, CS18, and CS20) (204) and those that are unique (CS3, CS6, and CS10 to CS12). Within each of these families there are cross-reactive epitopes that have been considered as candidates for vaccine development (147).

TABLE 4.

Past and present designations for colonization factors of ETECa

| Nomenclature

|

Type of antigen | |

|---|---|---|

| Old | New | |

| CFA/1 | CFA/I | F |

| CS1 | CS1 | F |

| CS2 | CS2 | F |

| CS3 | CS3 | f |

| CS4 | CS4 | F |

| CS5 | CS5 | H |

| CS6 | CS6 | nF |

| CS7 | CS7 | H |

| CFA/III | CS8 | F |

| 2230 | CS10 | nF |

| PCF0148 | CS11 | f |

| PCF0159 | CS12 | F |

| PCF09 | CS13 | f |

| PCF0166 | CS14 | F |

| 8786 | CS15 | nF |

| CS17 | CS17 | F |

| PCF020 | CS18 | F |

| CS19 | CS19 | F |

| CS20 | CS20 | F |

| Longus | CS21 | F |

| CS22 | CS22 | f |

Abbreviations: F, fimbrial; f, fibrillae; nF, nonfimbrial; H, helical. All except CFA/I have the CS designation (66).

Of the wide range of CFs, the most commonly present on diarrheagenic strains include CFA/1, CS1, CS2, CS 3, CS4, CS5, CS6, CS7, CS14, CS17, and CS21 (66). These have been found on ETEC strains worldwide in various frequencies (Table 5). However, CFs have not been detected on all ETEC, and on roughly 30 to 50% of strains worldwide no known CFs could be detected. This could be due to the absence of CFs, to loss of CF properties on subculture of strains, or to lack of specific tools for their detection.

TABLE 5.

Colonization factor profiles of ETEC isolated from children with diarrhea in different countries

| Country | n | % CFsa | % of strains expressing indicated CF

|

Reference | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFA/I | CFA/II

|

CFA/IV

|

CS7 | CS17 | CS14 | Other | ||||||||||||

| CS1+3 | CS2+3 | CS3 | CS4+6 | CS5+6 | CS6 | |||||||||||||

| Argentina | 109 | 52 | 23 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 15 | 3 | NT | 16 | |||||||

| 68 | 55 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 9 | 3 | 9 | 7 | 1 | 207 | |||||

| Bangladesh | 662 | 56 | 13 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 132 | ||||

| 10,000 | 59 | 27 | 11 | 8 | 3 | 6 | 13 | 10 | 6 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 215 | |||||

| Egypt | 100 | 23 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 128 | |||||||

| 933 | 42 | CS1+3>CS2+3>CS3

|

CS4+CS6=CS5+CS6<CS6

|

139 | ||||||||||||||

| India | 111 | 76 | 14 | 5 | 0 | 15 | 11 | 4 | 17 | 7 | 180 | |||||||

| Guatemala | 96 | 51 | 10 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 12 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 201 | |||||

| Chile | 93 | 47 | 12 | 27 | 24 | NT | 99 | |||||||||||

| Guinea Bissaub | 795 | 58 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 11 | 3 | 4 | 183 | |||||||

Indicates % of ETEC with any CF.

ETEC from children with diarrhea or asymptomatic carriers.

ETEC Serotypes

Besides determination of the toxins and CFs, serotyping, i.e., determination of O serogroups associated with the cell wall lipopolysaccharides and H serogroups of the flagella, has been used to identify and characterize ETEC (124). In early studies in, e.g., Bangladesh, it was suggested that typing of the most prevalent serotypes might be used to identify ETEC (112). However, as shown in numerous studies in different countries, clinical ETEC isolates may belong to a large number of serotypes. Furthermore, ETEC serotype profiles may change over time (186).

Based on an extensive database analysis of ETEC from a number of different countries all over the world, Wolf reported that in the ETEC antigen the largest variety was the O antigen (211). Thus, 78 different O groups were detected in the 954 ETEC isolates included in the study (hereafter called the ETEC database). In addition, there were several rough strains that lacked side chains, thus being nontypeable with regard to O antigen, or strains that had unknown serogroups. The most common O groups in this retrospective study were O6, O78, O8, O128, and O153; these accounted for over half of the ETEC strains.

In a more recent study in Egypt, a large variation of O groups was also recorded, with 47 O groups being represented among the 100 ETEC strains isolated; however, an entirely different O group pattern was recorded than in the database, the most common O groups in the Egyptian study being O159 and O43 (128).

Considerably fewer H serogroups than O serogroups are associated with ETEC. Thus, a total of 34 H groups were identified among the 730 ETEC strains included in the ETEC database (211). Five H types accounted for over half of those strains and they were widespread. Similarly, five different H types accounted for almost half of 100 ETEC strains isolated prospectively from Egyptian children, although different H types predominated from those reported for the ETEC database (128).

There are clearly preferred combinations of serotypes, CFs, and toxin profiles in ETEC. For instance, certain H groups are strongly associated with an O serogroup, such as O8:H9, O78:H12, and O25:H42, and some O and H serogroups are associated with one or more CFs (112, 214). In a study of ETEC isolated from children in Argentina, it was shown that most CFs were expressed by strains exhibiting a limited array of serotypes, while the ETEC strains that lacked detectable CFs belonged to many different serotypes (207). However, the significance of these different combinations regarding enhanced virulence (211) or for vaccine development is still unclear.

Serotyping appears to give an indication of the variety of strains that are present in a particular ETEC type in a certain geographical area. A close genetic relationship has been found within ETEC strains belonging to a certain serotype, which is different from that noted in other serotypes, and the pattern of genetic relatedness did not change over a period of 15 years (125). The loss of CFs and toxin phenotypes did not affect the genetic relatedness of these strains and their clonal relationship, which suggests that serotype analysis can be coupled to genetic typing for studying the clustering of strains for epidemiological and pathogenetic studies of ETEC. Altogether, the great variation in O and H serogroups in ETEC makes serotyping less suitable for identification of these bacteria and makes O and H antigens less attractive as putative candidate antigens in an ETEC vaccine.

ETEC Strains in Animals

ETEC is also a major cause of severe diarrheal disease in suckling and weanling animals (66, 115). Animal ETEC strains are known to produce enterotoxins similar to those of human strains and to possess species-specific CFs. The LT from animal strains, designated LT1, is similar to the LT produced by human ETEC; however, another variety designated LTII is only found in animals and is not associated with clinical disease. Animal strains produce two major types of ST, designated STa (STI) and STb (STII). STa, which is a small molecule of ca. 2.0 kDa, was the first of the enterotoxins to be identified in animals (177). As in humans, both STh (STIb) and STp (STIa) may be produced by animal strains. Animal strains (rarely human strains) can also produce STb, a slightly larger ST (ca. 5 kDa), which does not activate intracellular nucleotide levels and whose mechanism of action is poorly understood (115).

Like human ETEC, animal strains also have distinct binding proteins (adhesins and fimbriae), which allow the organisms to attach and colonize the small intestinal mucosa. Indeed, ETEC CFs display a remarkable species specificity, and colonization factors are clearly different from those of human and animal ETEC. Their genetic control may be in plasmids or in the chromosome. The most common of these have been designated K88, K99, and 987P, but there are at least another eight or more, which have other designations. The animal colonization factors are now being identified by F numbers, such as F4, F5, and F6 instead of K88, K99, and 987P (65). Because of the specificity of these adhesins, animal ETEC strains normally do not infect humans. This is in contrast to other diarrheagenic E. coli, such as those that produce Shiga-like toxins, e.g., O157:H7, which are found in animals, mainly cows, and produce severe disease in humans (92)

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Age-Related Infections in Children and Adults

Studies over the last few years have documented that ETEC is usually a frequent cause of diarrhea in infants younger than 2 years of age (132, 139, 183). In Egypt it was found to be the most common cause of diarrhea in the study infants, accounting for about 70% of the first episodes (139). The incidence was higher in males than females. In a detailed investigation in children 0 to 5 years in Bangladesh, 90% of cases of ETEC diarrhea reporting to the hospital were children aged from 3 months to 2 years (132). In an ongoing birth cohort study in Bangladesh, it was found to be the most common cause of diarrhea in children 0 to 2 years of age, accounting for 18% of all diarrheas.

The susceptibility of infants and young children has also been observed in other settings which have poor public health and hygiene conditions. The characteristics of the toxin types and CFs present on ETEC strains isolated from young children vary among countries where ETEC is endemic (139, 183, 215). A comparison is shown for Bangladesh and other developing countries (Tables 1 to 5). Studies to better understand the natural infection pattern of ETEC are being conducted with cohorts of infants to discern the infection and reinfection pattern as well as the age group most at risk for infection. In studies of infants in West Africa, Egypt, and Bangladesh, the rate of ETEC infections in community-based studies increased from about 3 to 6 months of age, similar to the surveillance data of hospitalized patients in a diarrheal hospital in Bangladesh (139, 183, 215). The age at which a primary ETEC infection can be documented depends to some extent on the phenotype of ETEC that is infecting the child. In a study in Guinea Bissau, it was reported that in the youngest age group, 3 months, ETEC strains producing STh and LT were most common, whereas at 6 to 7 months ETEC strains producing STp, STpLT, and SThLT predominated (183).

The incidence of ETEC infections in developing countries decreases after 5 years of age with a decrease of infections between the ages of 5 to 15 years (Table 6). The incidence increases again in those over 15 years of age and about 25% of ETEC illness is seen in adults (113, 132). Limited epidemiological information is available for adults, and those available are mostly from India and Bangladesh. It was in these settings that ETEC was first described extensively and was shown to be a cause of adult diarrhea resembling cholera in the severity of infection (113, 149, 154). It thus became obvious that adults with severe dehydrating cholera-like illness attributable to ETEC infections are not uncommon (132, 214). In hospitalized patients, adults often present with more severe forms of ETEC diarrhea than children and infants (Table 7). Interestingly, further analyses have shown that the elderly are also susceptible to ETEC infections requiring hospitalization (62). ETEC was found to be the second most frequently isolated (13%) bacterial pathogen after V. cholerae O1 (20%). In this age group (>65 years), patients also presented with more severe dehydration than children.

TABLE 6.

Toxin profiles of ETEC isolated from patients of different age groups in a hospital in Bangladesha

| Toxin type | No. (%) of subjects aged:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-23 mo | 24-59 mo | 5-14 yr | ≥15 yr | Total | |

| ST | 182 (55) | 31 (51) | 21 (44) | 72 (40) | 306 (50) |

| LT | 73 (22) | 15 (25) | 8 (17) | 55 (31) | 151 (24) |

| LT/ST | 75 (23) | 15 (25) | 19 (40) | 52 (29) | 161 (26) |

| Total | 330 | 61 | 48 | 179 | 618 |

Data are from the surveillance for ETEC from 1996 to 2000 from patients with diarrhea enrolled in the 2% systemic routine surveillance system at the ICDDR in Bangladesh (185). The numbers of patients and percent positive for the respective toxins are shown. Data are from patients infected with ETEC as a single pathogen.

TABLE 7.

Clinical characteristics of adults and children hospitalized with ETEC, V. cholerae O1, and rotavirus diarrhea in Dhaka, Bangladesh, from 1996 to 2002a

| Variable | % of adults

|

% of children

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETEC (N = 478) | V. cholerae O1 (N = 1,417) | ETECa (N = 1107) | V. cholerae O1 (N = 865) | Rotavirus (N = 3,406) | |

| Vomiting | 81 | 92 | 80 | 89 | 87 |

| Fever | 7 | 2 | 19 | 15 | 22 |

| Severe dehydration | 36*‡ | 64* | 3†‡ | 23† | 2† |

| Moderate dehydration | 41 | 29 | 24 | 40 | 19 |

| None/mild dehydration | 23 | 7 | 73 | 37 | 79 |

| Intravenous management | 54* | 84* | 10† | 43† | 5† |

| Oral rehydration | 46* | 16* | 90† | 57† | 95 |

| Outpatient stay | 14 | 4 | 31 | 13 | 24 |

| Inpatient stay | 86 | 96 | 69 | 87 | 76 |

| Watery stool | 95 | 99 | 97 | 98 | 97 |

| Nonwatery stool | 5 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Stool with blood | 2.3 | 1 | 17 | 1 | 1 |

Data are from 15,558 patients seen at the diarrhea hospital in Bangladesh based on the routine surveillance for enteric pathogens (185). The age of the children ranged from 0.1 to 36 months (median, 0.83 years) and that of the adults from 15 to 80 years (median, 30 years), *, P < 0.001 in comparisons (*) between adults with ETEC or V. cholerae O1 diarrhea; (†) between children with ETEC or rotavirus diarrhea in comparison to V. cholerae O1 diarrhea; (‡) between adults and children with ETEC diarrhea. For rotavirus diarrhea only, data from children are given.

The reason why ETEC infections decrease after infancy and increase at adulthood may be due to both environmental and immunological factors. Data obtained from studies in animals indicated changes with age in the presence of intestinal cell receptors for K99 fimbrial antigen produced by ETEC infecting animals (148). Another factor could be the immunogenetics and diversity between individuals, which may prevent or predispose to ETEC infections (33, 69) or increased immune responses due to repeated infections in early childhood, which may decrease due to fewer infections during adolescence (Table 6).

Relation to Presence of LT, ST, and Colonization Factors

Indeed, ETEC expressing LT only have been considered less important as pathogens, especially since they are more frequently isolated (than the other two toxin types) from healthy persons than from patients (33). This could be related to the low prevalence of CFs on the LT-producing ETEC strains (66, 110). Thus, in many epidemiological studies, the CFs have been detected on less than 10% of LT-producing ETEC strains, compared to over 60% of the ST- and LT/ST-expressing ETEC. However, it cannot be excluded that LT-producing ETEC strains may be highly pathogenic, given that they may have been isolated from sick patients with severe dehydrating diarrhea (Table 8).

TABLE 8.

Association of severity of disease with toxin type and presence of known colonization factors on ETEC in children up to 3 years of age in rural Bangladesh during a 2-year surveillancea

| CF and toxin type | No. (%) with symptoms that were:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | Total | |

| CF positive | 142 (56) | 90 (36) | 20 (8) | 252 |

| CF negative | 140 (64) | 56 (26) | 22 (10) | 218 |

| ST | 131 (56) | 78 (33) | 24 (11) | 233 |

| LT/ST | 69 (52) | 54 (41) | 10 (7) | 133 |

| LT | 82 (79) | 14 (13) | 8 (8) | 104 |

CF types were studied with a panel of 13 different monoclonal antibodies against the most prevalent CFs (66, 132). The degree of dehydration of the child from whom the ETEC strain was isolated is indicated. The strains were isolated from children in the hospital at Matlab in Bangladesh. Data are from patients infected with ETEC as a single pathogen. A significant difference (P < 0.05) was only seen between ETEC strains positive for ST (P < 0.001) or LT/ST (P < 0.001) and LT. The latter were isolated at significantly lower frequencies from children with moderate dehydration. Chi square for trends was used for statistical analysis.

A comparison of the toxin pattern of the infecting strains in patients hospitalized with diarrhea in the different age groups shows that the toxin phenotype did not change with age (132) (Table 6). In longitudinal studies with infants, both LT and ST phenotypes of ETEC were found to be associated with diarrhea (1, 37). This has been shown to be the case also in hospital- (7, 8) as well as community-based studies (1, 37). However, in hospital-based studies (132), ETEC producing both LT and ST or ST alone were found to cause relatively more severe disease than that caused by LT-producing ETEC strains (Table 8).

Although over 22 CFs have been detected on ETEC (Table 4), only six to eight are more frequently isolated from diarrheal stools (Table 5). Of these, CFA/I and CS1 to CS6 are the predominant types (66). These CFs are mostly present on ETEC producing ST or both LT and ST. It is believed that immunity to strains that express the nonimmunogenic ST is derived from the anti-CF response to the protein adhesins. Thus, in the development of vaccines, these CFs as well as LT are being included to give a broad-spectrum protection (189, 192).

The relationship between the presence of colonization factors and the disease-producing capability in ETEC diarrhea has been analyzed in many different epidemiological settings. In community-based studies the risk of diarrhea increased when a CF was present on the infecting strain (1). In Bangladesh the presence or absence of CFs on ETEC could not be associated with the severity of diarrhea in hospitalized patients (Table 8) (132). Studies in Mexico suggest that there is a reduced risk of diarrhea in infants if there was reinfection with ETEC producing the same compared with different CFs (38).

In volunteer challenge studies, protection was observed to ETEC with the same CF as that present on the vaccine strain (97). Some CFs are seen more often in infants than in adults, suggesting that natural immunity to infection may develop. Thus, studies in Bangladesh have shown that almost all ETEC expressing CS7 and CS17 were isolated from children less than 3 years of age (132). LT-producing ETEC strains expressing CS7 were also most pathogenic in a birth cohort in West Africa whereas CF-negative strains were not, suggesting that the presence of a CF, even in the absence of ST, enhances the virulence of ETEC (183).

Single Versus Mixed Infections

Coinfection with ETEC and other enteric pathogens is common, which may lead to problems in determining whether the symptoms are caused by the actual ETEC infection and understanding the actual pathogenesis of the infection (134, 182). Mixed infections are frequent and may be seen in up to 40% of cases (7, 17, 127, 132, 139). The presence of enteric pathogens in asymptomatic persons is also known to be high in areas of poor sanitation. The incidence of mixed infections seems to increase with age in studies in Bangladesh and fewer copathogens were seen in infants than in older children and adults with ETEC diarrhea (134). In cases of mixed infections in children, rotavirus is the most common, followed by other bacterial enteropathogens, e.g., V. cholerae, Campylobacter jejuni, Shigella spp., Salmonella spp., and Cryptosporidium (7, 67, 166). In traveler's diarrhea, enteroaggregative E. coli and Campylobacter spp. have been common pathogens together with ETEC (2, 127).

Seasonality of ETEC

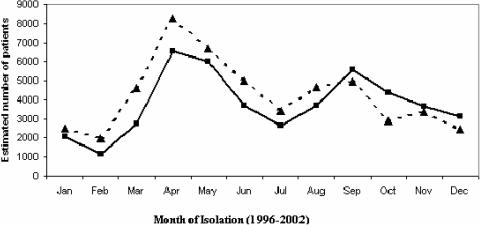

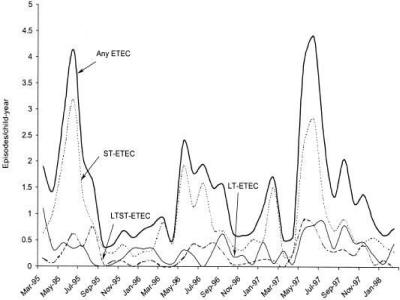

Several studies have reported that ETEC diarrhea and asymptomatic infections are most frequent during warm periods of the year (1, 8, 79, 103, 132, 139, 167, 183), suggesting that travelers to these regions are also more at risk to develop ETEC infections during the warm seasons. In Bangladesh, ETEC follows a very characteristic biannual seasonality with two separate peaks, one at the beginning of the hot season, that is, the spring, and another peak in the autumn months, just after the monsoons, but it remains endemic all year (8, 94, 132, 146) (Fig. 1). Such a seasonality may be initiated by climate and spread by environmental factors. As the atmospheric temperature increases when spring sets in after the cooler winter months, there is increased growth of bacteria in the environment and this continues in the summer months. Furthermore, with the advent of rains in the monsoon season, there is enhanced contamination of surface water with fecal material and the surface water can thus become heavily contaminated (146). A seasonality for the different toxin phenotypes has also been suggested, with ST-producing ETEC strains being more common in the summer (1, 139) whereas LT-producing ETEC strains are present all year round and do not show any seasonality (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Estimated numbers of enterotoxigenic E. coli and V. cholerae O1 isolated from diarrheal stools of children under 5 years of age from surveillance carried out from 1996 to 2002 at the International Centre for Diarrheal Disease Research hospital in Dhaka, Bangladesh. The figure indicates monthly isolation of ETEC (▴) and Vibrio cholerae O1 (▪).

FIG. 2.

Monthly incidence of ETEC diarrhea in Abu Homas, Egypt, showing that ST-producing ETEC was more common in warmer months, while LT-producing ETEC was present at similar levels throughout the year. Reproduced from reference 139 with permission.

Comparison of ETEC Diarrhea and Cholera in Children and Adults

In Bangladesh cholera and ETEC diarrhea are still endemic (134, 165). Both diseases share a biannual periodicity, peaking once in the spring and again in the autumn (Fig. 1) and remaining endemic all year (63). In the spring ETEC infections appear to be more prevalent than V. cholerae O1 infections (Fig. 1). In a recent 4-year study, carried out for the surveillance for cholera in rural Bangladesh (165), it was found that ETEC and not V. cholerae was often the cause of the diarrhea in some of these field areas (215). It is also not surprising to have concomitant outbreaks of both ETEC and V. cholerae during peak seasons and during outbreaks (31, 63). Active screening for ETEC needs to be carried out in outbreaks and epidemics for both epidemiological and public health purposes.

A large proportion of patients with ETEC infection have short stays in the hospital and only about 5% of patients need to be hospitalized for longer periods of time. The length of stay at the hospital is similar for patients infected with any of the three toxin phenotypes of ETEC. Few patients go on to chronic illness (>14 days). Patients with ETEC diarrhea and cholera have similar clinical characteristics and differ mainly in the rates of severe dehydration (Table 7).

Presence of ETEC in Food and Water in the Environment

Diarrhea due to ETEC, like other diarrheal illnesses, may be the result of ingestion of contaminated food and water (26, 40, 87, 99, 121, 122). In any situation where drinking water and sanitation are inadequate, ETEC is usually a major cause of diarrheal disease. Surface waters in developing countries have been found to harbor these organisms (14, 121) and transmission can occur while bathing and/or using water for food preparation. These forms of transmission are common in area where it is endemic both in the local populations and in international travelers to these areas (see the later section on traveler's diarrhea).

Transmission of ETEC by processed food products outside of the developing world is less commonly seen but well documented. In 1977, Sack et al. found that of 240 isolates of E. coli from food of animal origin in the United States, 8% were found to contain ETEC which produced either or both LT and ST (164). None of these food products were associated with diarrheal outbreaks. In studies carried out in the 1970s in Sweden, however, outbreaks of diarrhea due to food-borne ETEC were reported (41). Similar findings were reported from Brazil in 1980 (144); 1.5% of 1,200 E. coli strains from processed hamburger or sausage were found to be ETEC. ETEC transmission on cruise ships has now been reported on several occasions (40). These findings suggested that since ETEC is not uncommonly found in meat and cheese products, these organisms have the potential for producing diarrheal outbreaks in different parts of the world.

Contaminated weaning food is also a likely cause of ETEC diarrhea in infants (139, 146). Contaminated food and water sources both contribute to seasonal outbreaks which affect tourists. Thus, ETEC is a cause of traveler's diarrhea more often in the warm than in the cool season. In a study in Bolivia it has been shown that ETEC could be isolated from a sewage-contaminated river (121). Furthermore, contaminated food and water were found to be the source of ETEC infections in Peru (23).

Surface water sources in Bangladesh, in both rural and urban areas, are highly contaminated with ETEC. Thus, recently in a study in Bangladesh, ETEC strains were obtained from clinical samples as well from ponds, rivers, and lakes around the clinical field site. In this study it was found that 32% of water samples obtained from the surface water sources were contaminated with ETEC and that the toxin and CF phenotypes of strains isolated from the clinical and environmental samples were comparable (14). Furthermore, pulsed-field gel electrophoretic analysis of the ETEC strains showed that those present in the environment were similar to the clinical isolates, supporting that, as seen for V. cholerae, surface waters may be a major source for the survival and spread of ETEC.

Studies in communities where personal hygiene, education, and general living conditions are poor have shown that infection can spread within family groups. In one study on ETEC infections in Bangladesh, the bacteria were spread to 11% of contacts in a 10-day study period (25); transmission was dependent on socioeconomic status and living conditions. Contaminated food and water and the mothers themselves, who are food handlers, seem to be the reservoirs for such infections (54). It is not surprising therefore that the possession of a sanitary latrine significantly decreased the risk of ETEC diarrhea in children in Egypt (1). On the White Mountain Apache reservation in Whiteriver, Arizona, where ETEC was found to be an important cause of diarrhea in children, these organisms were also found in river water, sites of large gatherings of Apaches on festive occasions (162). Although ETEC has been detected as a cause of diarrhea in Apache children in Arizona (162), where water and sanitation were suboptimal, subsequent studies in the developed world where water supplies and sanitation are optimal show very low frequencies of ETEC in children with diarrhea (156).

ETEC Infections and Malnutrition

As for other diarrheal diseases, preexisting malnutrition can lead to more severe enteric infections, including those caused by ETEC, possibly due to the immunocompromised nature of the host that also predisposes these individuals to a greater bacterial load on the mucosal surfaces of the gut than the well-nourished child (28).

In a study in India, diarrheal illness including that caused by ETEC was found to be more severe in children with malnutrition (107). Micronutrient deficiency such as vitamin A and zinc is quite common in developing countries and generally increases the morbidity due to diarrheal illnesses (137, 140), although the effect on the morbidity of ETEC diarrhea has not yet specifically been studied. It has been estimated that in Bangladesh over 40% of children younger than 5 years of age may have zinc deficiency (131, 168). Supplementation with zinc increases the adaptive immune responses to cholera vaccination in children and adults (9, 91, 131) and in children with shigellosis (140). The effect of micronutrient deficiency on the morbidity and protective immune responses in ETEC diarrhea has not been specifically studied but is an area that needs attention. However, repeated diarrheal episodes including those induced by ETEC may be an important cause in predisposing the child to malnutrition (22, 106).

Other factors, such as breast feeding, may have the capacity to prevent ETEC diarrhea. Factors in milk such as specific secretory immunoglobulin A antibodies and receptor analogues (85) as well as innate and anti-inflammatory factors may all contribute to decrease the infection. Hyperimmune bovine colostrum containing high titers of ETEC CF antibodies has been shown to provide temporary protection against ETEC challenge (64) but is not suitable for public health application (198). Breast feeding reduces overall diarrhea and mortality (71, 205). A reduction in diarrheal episodes has been seen in infants who had been breastfed for the first 3 days of life, irrespective of other dietary practices, emphasizing the positive effects of colostrum (34). Studies in Bangladesh have shown that breast milk antibodies against cholera toxin and lipopolysaccharide do not protect children from colonization with V. cholerae but do protect against disease in those that are colonized (72).

Protection from cholera in breastfed infants of mothers immunized with killed cholera vaccine could not be correlated to antibacterial and antitoxic antibodies in breast milk, suggesting that the reduced transmission of pathogens from the mother to the infant had a protective effect (35). Since secretory immunoglobulin A antibodies to CFs and enterotoxin are present in breast milk samples from mothers in developing countries (39, 84, 187), it would be natural to assume that breastfed infants should be protected from ETEC diarrhea. However, epidemiological studies show that partial breast feeding does not result in a reduced risk of ETEC diarrhea. However, in data obtained in various studies, it appears that exclusive breast feeding practices have a positive effect of decreasing the severity and/or incidence of ETEC infections (34, 102, 136). This effect is short term and does not last long after infancy, and an overall protection is not seen in the crucial first 2 to 3 years of life (1, 34, 139).

The limited capacity of breast milk to protect against ETEC diarrhea in developing countries can also be attributed to other social and behavioral factors. These include the introduction of contaminated water and weaning food in the child's diet, leading to increased symptomatic as well as asymptomatic ETEC infections. In Mexico, the incidence of diarrhea increased even in the first 3 months of age if a barley drink was given to the infant (102). Since mixed feeding is started quite early in life in a majority of infants in developing countries, sometimes as soon as after birth, contaminated water may also be the cause of a multitude of infections (146). The importance of personal hygiene rather than breastfeeding appeared to be more protective against ETEC diarrhea in Egypt (1).

Infections in International Travelers

ETEC remains endemic all year round but is highest during the warm season, reflecting the seasonal difference of ETEC and other bacterial enteropathogens in the country visited (109, 175), suggesting that travelers are more vulnerable to the diarrheal illnesses at these times. In travelers, the phenotypes of ETEC strains vary from country to country, e.g., LT-only ETEC was more commonly isolated from visitors to Jamaica, 58% (90), and LT/ST ETEC was most often seen in visitors to India, 45% (90), and ST-only ETEC in visitors to Kenya, 51% (175). Thus, strains that are circulating in a particular country, infecting primarily children, and contaminating the water and food sources (as well as the hands of the food handlers) may determine the type of ETEC infecting the travelers. Travelers to such countries do not know the cause of their diarrheal illness since it cannot be identified on site, outside of research studies. The data available suggest that from 20 to 40% of traveler's diarrhea cases (18, 90, 159, 175) may be caused by ETEC, and the children resident in those countries have rates of 20% of hospitalized diarrheal episodes caused by ETEC. Thus, ETEC seems to be the most frequent cause of traveler's diarrhea in North Americans and Europeans visiting developing countries (58, 145, 150, 175, 213).

CLINICAL FEATURES

Disease Severity

The diarrheal disease caused by ETEC that was first recognized consisted of a cholera-like illness in both adults and children in Calcutta (161). Since then, many studies around the world have shown that ETEC-induced diarrhea may range from very mild to very severe. There are, however, short-term, asymptomatic carriers of the organisms (20).

The diarrhea produced by ETEC is of the secretory type: the disease begins with a sudden onset of watery stool (without blood or inflammatory cells) and often vomiting, which lead to dehydration from the loss of fluids and electrolytes (sodium, potassium, chloride, and bicarbonate) in the stool (25, 157). The loss of fluids progressively results in a dry mouth, rapid pulse, lethargy, decreased skin turgor, decreased blood pressure, muscle cramps, and eventually shock in the most severe forms. The degree of dehydration is categorized from mild to severe, and this clinical distinction is important in the provision of adequate therapy. The patients are afebrile. Usually the diarrhea lasts only 3 to 4 days and is self-limited; if hydration is maintained, the patients survive, and without any sequelae. With adequate treatment, the mortality should be very low (<1%).

The pathophysiology of the illness caused by ETEC is essentially the same as that caused by Vibrio cholerae (94) and the clinical picture is identical, especially in adults (Table 7). Studies with human volunteers have shown that the infecting dose is high for both diseases. For ETEC, the dose is around 106 to 1010 CFU, with lower doses being less pathogenic (100). The need for a large infectious dose, the proliferation of the bacteria in the small bowel through colonization factors and the production of enterotoxins, and the watery, secretory type of diarrhea which produces clinical dehydration are comparable in both diseases. Both organisms produce an immunologic protective response, reflecting the observation that the attack rates are higher in children and decrease with age (24, 134).

In Bangladesh, the majority of cases of acute watery diarrhea, especially in children, are caused by three pathogens, rotavirus, V. cholerae, and ETEC (7, 8, 24). Hospital-based studies during the early 1980s have demonstrated that the purging rate is higher in cholera compared to the other two illnesses (114). A comparison of the clinical features of the disease in adults with ETEC and V. cholerae infections seeking care at the hospital in Bangladesh shows that ETEC disease differs significantly from V. cholerae infections in the severity of dehydration (Table 7), although both infections can result in severe dehydration. In comparison to children, adults with ETEC diarrhea seem to have more dehydrating illness, requiring longer hospitalization and more intravenous fluid management. This may be because of more delay in reaching a treatment facility. In children, rotavirus and ETEC diarrhea share similar clinical characteristics but differ from cholera in being less severe (Table 7).

It should be mentioned that the adult form of ETEC-related disease (of considerable severity) seems to be identified more in the Indian subcontinent. There are few (if any) reports of ETEC in adults, other than in traveler's diarrhea. This may be due to the lack of diagnosis in adults, again because of the lack of easily available laboratory techniques.

Mortality from ETEC Diarrhea

Mortality data due to ETEC infections are difficult to estimate. Similar to cholera, if patients with severe ETEC disease reach an adequate treatment center, mortality should be very low, <1%. Although untreated cholera patients may have a high mortality (∼50%), untreated ETEC patients would be expected to have a lower mortality rate based on the lesser severity of illness overall. In a World Health Organization report it has been suggested that there are 380,000 deaths annually in children less than 5 years of age that are caused by ETEC (214). However, there are no well-documented mortality figures for ETEC-induced diarrhea, because the microbiologic diagnosis cannot be done easily in many settings, and therefore only rates for cholera, which is cultured easily, can be accurately determined. ETEC-related deaths at present would be counted as diarrheal deaths in many countries. It is presumed, however, that there is significant mortality in patients not receiving treatment.

DIAGNOSIS

Laboratory Assays

Since ETEC must be recognized by the enterotoxins it produces, diagnosis must depend upon identifying either LT and/or ST. Because the assays necessary were very cumbersome, it was thought that some other marker could be a proxy in identification. Initially the serogroups of ETEC were identified and found to be relatively few, and therefore it was thought that perhaps serotyping could be used to differentiate ETEC from other E. coli, including the enteropathogenic strains whose characteristic serotypes were known (124). Serotyping was found to be of limited use in Bangladesh (113, 152, 186) and when it became clear that a very large number of E. coli serotypes could be enterotoxigenic, this was abandoned.

Direct identification of the enterotoxins of ETEC has evolved over the past 35 years. Physiologic assays, the rabbit ileal loop model for LT (43), and the infant mouse assay (44) for ST were initially used as the gold standards before other simpler assays could be identified. Because LT was strongly immunogenic whereas ST was not, diagnostic assays developed along different lines. In 1974 the direct action of LT on two tissue culture cell lines, Y1 adrenal cells (46) and Chinese hamster ovarian cells (78), was found to be provide physiological responses that could be detected by morphological changes in tissue culture. These changes were specific for LT and could be neutralized by antitoxin. The two tissue culture assays were widely used for LT recognition until the development of the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay technology in 1977 (217). Other assays such as staphylococcal coagglutination (32), passive latex agglutination (173), immunoprecipitation in agar, and the Biken test (86) were found to be specific but were not used widely for diagnostic purposes. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays became a widely used method for detecting LT, particularly using microtiter GM1 ganglioside methods (190, 196). Subsequently, combined GM1 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for ST and LT were developed (196, 197) and have been used in different epidemiological studies (1, 16, 126, 128, 132).

ST testing in infant mice continued to be used widely and could be enhanced by the use of culture pools, thereby minimizing the numbers of infant mice. In 1981 Gianella developed a radioimmunoassay for ST which compared favorably with the infant mouse assay (68).

In 1980, methods using molecular diagnostic techniques began. Moseley et al. (104) showed that the genes controlling the enterotoxins could be detected using 32P-labeled DNA probes derived from plasmids for both LT and ST. This method was shown to be specific and sensitive and could detect as few as 1 to 100 CFU per gram of material (53, 82). Variations of this technology, including both polynucleotide and oligonucleotide probes with both radioactive and nonradioactive labeling, have been found to be useful in detecting ETEC both in clinical and environmental samples and is widely used (7, 53, 82).

In 1993, PCR was first used in ETEC diagnosis (123). It was found to be useful for diagnosis directly on fecal material as well as of isolated colonies (172). It was also adapted to a multiplex form so that the diagnosis of LT- and ST-producing organisms as well as other diarrheagenic E. coli can be made simultaneously (181, 200, 208, 209).

During recent years DNA probes, with either radioactive or nonradioactive detections or GM1 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays using monoclonal antibodies against ST or LT have been the most widely used methods for detection of ETEC toxins (7, 133, 183, 188).

For detection of ETEC colonization factors a number of different methods have been used during the years. Initially the capacity of E. coli CFs to agglutinate certain species of erythrocytes in a mannose-resistant manner was used for demonstration of CFA/I and CS1, CS2, and CS3 (60). This nonprecise method was soon replaced by more specific slide agglutination and immunodiffusion tests initially using polyclonal sera and subsequently monoclonal antibodies against different CFs (5, 76, 110). Other methods that were used included nonspecific salting-out tests (16) and binding to tissue culture cell lines (42). These assays have now been replaced by different molecular methods, e.g., DNA probes and PCR methods against most of the known CFs or dot blot assays using several different anti-CF monoclonal antibodies (133, 139, 180, 182).

The method of choice varies from one laboratory to another and is dependent on the capability of the investigator and the level of development of the laboratory where the work is being carried out. The phenotypic methods can be set up relatively easily in different laboratories and are useful for prospective studies; most reagents are not available commercially but may be obtained from different laboratories. One point to bear in mind is that the virulence antigens are encoded by plasmid genes and can be easily lost or become silenced due to the loss of regulatory genes (182). The more recently developed DNA probe methods have the capacity to detect the structural genes for toxins and CFs and thus have the advantage of detecting ETEC from samples which have been stored for long periods of time and where phenotypic changes may have taken place. These procedures are more difficult to adapt to field sites in developing countries, where laboratory facilities may be inadequate for molecular microbiological methods. Furthermore, in some instances ETEC CFs can only be detected by molecular but not phenotypic methods, since they are not exposed on the bacterial surfaces due to mutation of genes required for surface expression (119).

Unfortunately, in spite of all these available techniques, there are still no simple, readily available methods that can be used to identify these organisms in minimally equipped laboratories. For that reason many laboratories conducting studies on diarrhea in developing countries do not include ETEC in their routine diagnostic capabilities, and special research or referral laboratories are necessary to identify these bacteria.

TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT

The treatment of diarrheal disease due to ETEC is the same as that for cholera or any other acute secretory diarrheal disease. The correction and maintenance of hydration is always most important. Antimicrobials are useful only when the diagnosis or suspicion of ETEC-related diarrhea or cholera is made. Provision of adequate nutrition is critical in children in the developing world, where all diarrheal diseases are frequent. The guidelines for therapy of all diarrheas have been widely disseminated by the World Health Organization (216).

Rehydration

Rapid rehydration using intravenous fluids (such as Ringer's lactate) is required initially for all patients with severe dehydration. After restoration of blood pressure and major signs of dehydration, patients can be put on oral rehydration solutions for the remainder of therapy. For all other patients with lesser degrees of dehydration, therapy with oral rehydration solutions alone can be used until the diarrhea ceases. Details of management of acute gastroenteritis in children have recently been summarized by King and colleagues (6, 95).

Antimicrobials

The use of antimicrobials in the treatment of ETEC diarrhea is problematic, since an etiologic diagnosis cannot be made rapidly. This differs from the treatment of cholera, an epidemic disease, where clinical findings and rapid laboratory tests can readily lead to correct diagnosis. In cholera treatment, antimicrobials are an integral part of therapy because they lead to a marked decrease in stool output and shortening of the disease (30, 95). Because childhood diarrheas, however, are caused not only by ETEC but also by other bacterial and viral agents, and the clinical presentations are not sufficient to differentiate them, it has been difficult to study the effect of antimicrobials in children with ETEC disease and antimicrobials are not used routinely in treatment of childhood diarrhea. One study in Bangladeshi adults in which tetracycline was used to treat ETEC diarrhea (determined retrospectively) showed only a minimal effect on the severity or duration of diarrhea (113).

Antimicrobials, however, are of definite benefit in the treatment of diarrhea of travelers, a diarrheal syndrome in which the clinical symptom is well recognized and ETEC is known to be the most frequent pathogen (90). It should be noted, however, that antimicrobials used for traveler's diarrhea will treat not only ETEC but also most of the other known causes (enteroaggregative E. coli, Shigella, and Campylobacter) of the diarrhea.

The antimicrobial treatment of traveler's diarrhea has changed over the years because of increasing antimicrobial resistance (58). When ETEC were first recognized, the bacteria were usually highly sensitive to all antimicrobials, including tetracyclines and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (159). However, with time, antibiotic resistance emerged, necessitating the use of newer antimicrobials for treatment of traveler's diarrhea. Antimicrobials that have been used in effective treatment include doxycycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, erythromycin, norfloxacin, ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, azithromycin, and rifamycin. A summary of these studies over the years is given in several references (58, 159). The general history of the evolving antibiotic resistance patterns in ETEC is given in Table 9.

TABLE 9.

Changing pattern of antimicrobial sensitivity of ETEC from its identification to the presenta

| Yr and subjectsa | Sensitivity | References |

|---|---|---|

| 1968-1980, T/EP | Sensitive to all antimicrobials (Mexico, India, U.S.A., Kenya, Morocco) | 49, 150, 154, 160 |

| 1980-1990, T/EP | Single antibiotic resistance appears (Mexico, Bangladesh) | 47, 48, 104, 186, 213 |

| 1990-present, T/EP | Multiple antimicrobial resistance appears (Tet, Amp, SXT, Doxy, Nal, Ery, S) (Somalia, Middle East, Bangladesh) | 31, 89, 176 |

| 2001-present, T/EP | Resistance to Cip and fluoroquinolones and multiple resistance (India, Japan) | 31, 108 |

T, travelers, including army and service personnel stationed in or visiting ETEC-endemic countries; EP, endemic population. Tet, tetracycline; Amp, ampicillin; SXT, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; nal, nalidixic acid; Ery, erythromycin; S, streptomycin; Doxy, doxycyline; Cip, ciprofloxacin.

At present, recommendations for treating ETEC can only be stated for surety in the treatment of traveler's diarrhea, where ETEC are known to be the most frequent cause (51). For adults we recommend a short course of ciprofloxacin, 500 mg every 12 h for 1 day, which usually stops the illness within 24 h. The new nonabsorbable antimicrobial rifaximin (50) has only recently become available and is effective for treatment of traveler's diarrhea in adults, using 200 mg two times a day for 3 days. For children, we empirically recommend azithromycin, 10 mg/kg/day for 2 days, although there have been no studies to confirm this.

In areas where ETEC is endemic, antimicrobial treatment is usually not given because the diagnosis cannot be easily made microbiologically and there are no controlled studies to provide recommendations.

Multidrug Resistance Patterns

Which antibiotic can be used has changed since the late 1970s, when doxycycline and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole were the drugs of choice. Due to increasing microbial resistance of ETEC, newer drugs have been used. A fluoroquinolone such as ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, or ofloxacin is currently the drug of choice, since no significant resistance to these drugs has yet developed (58, 59). A newer nonabsorbed drug, rifaxamin, has also been shown to be as effective as a fluoroquinolone and has only recently been approved for use in the United States (50). Multidrug resistance is increasing in ETEC due to the widespread use of chemotherapeutic agents in countries where diarrhea is endemic. Antimicrobial sensitivities, however, have only been studied extensively in international travelers and during common source outbreaks of disease or specific epidemiologic studies in areas where diarrhea is endemic. The primary reason for this is the difficulty of recognizing the organisms.

Although no sensitivities were reported in ETEC strains first isolated in Calcutta in 1968, when ETEC strains were used in volunteer studies (49), they were sensitive to ampicillin, which was used for treatment. ETEC strains described for the first time in Apache children in Arizona in 1971 (162) showed a completely uniform sensitivity pattern.

Because of the high sensitivity of ETEC to doxycycline, and because it has a long half-life and high levels in stool, this drug was first chosen to study antibiotic prophylaxis among travelers to developing countries (75, 111, 151). The first studies of doxycycline prophylaxis were done in Peace Corps volunteers in Kenya (150) and Morocco (160), who showed high degrees of protection (∼85%). In the Kenyan study (150) all ETEC strains were sensitive to tetracycline, and only a few were resistant to streptomycin and sulfonamide in the Moroccan study (160). An interesting finding in these two traveler's diarrhea studies (150, 160) and the study in Apaches (162) was that nontoxigenic E. coli strains showed more antimicrobial resistance than ETEC. This pattern was also seen in a study of large numbers of ETEC isolated before 1978 (45), suggesting that there may be some protective effect of harboring enterotoxin plasmids; it was also shown that ST-producing strains were more likely to be resistant to antimicrobials than either LT or LT/ST strains.

In 1973, Gyles (81) found that a single conjugative plasmid carried genes for both antibiotic resistance and enterotoxin production, the result of recombination of an R factor with an enterotoxin-carrying plasmid. A few years later, Echeverria (56) found that antibiotic resistance and the ability to produce enterotoxin were frequently transferred together and suggested that the widespread use of antibiotics could result in an increase of enterotoxigenic strains. Plasmids coding for both antibiotic resistance and ST could be transferred in vitro to E. coli K-12 (56) and in vivo in suckling mice, suggesting that antibiotic selective pressure could result in a wider distribution of ETEC (105). This hypothesis, however, has never been conclusively verified.

A marked increase in resistance in ETEC began to be reported in 1980, when it was found that during a cruise ship outbreak the epidemic strain O25:NM was resistant to tetracycline and sulfathiazole (104) and in a hospital outbreak, all isolates of the epidemic strain were also resistant to tetracycline (89).

During a study of traveler's diarrhea in Mexico, in 1989 to 1990, 49% of 74 ETEC strains were resistant to doxycycline, 9% to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 35% to ampicillin, but none to norfloxacin or aztreonam (47) and in studies of outbreaks of ETEC diarrhea aboard three different cruise ships during 1997 to 1998, tetracycline resistance as high as 84% (27/32) was reported while 30% were resistant to more than three antimicrobials (40). This was a marked change from previous outbreaks before 1990 when no ETEC were resistant to more than three antimicrobials.

More recently, studies from Bangladesh and India have also shown multiple antimicrobial resistance of ETEC isolates. A comparison of the resistance pattern in strains isolated recently with those obtained 30 years back highlights the increase of resistance to commonly used drugs (48). Studies of ETEC strains isolated between 1999 and 2001 show intermediate to complete resistance to multiple drugs and combined resistance to four to six drugs (including erythromycin, ampicillin, cotrimoxazole, tetracycline, streptomycin, and doxycycline); however, not a single strain was found to be resistant to ciprofloxacin. In studies in India, multidrug resistance including resistance to nalidixic acid and to fluoroquinolones is increasing (31). In Bangladesh, ETEC strains are still sensitive to drugs which are generally used for the treatment of invasive diarrhea, but there needs to be more awareness of changing drug sensitivity patterns of ETEC when erythromycin is used for treatment of acute watery diarrhea in children.

Nutritional and Micronutrient Therapy

Recently it has been found that the addition of zinc to the therapy of diarrhea in children with diarrhea leads to shorter duration of illness and a decrease in mortality from diarrhea (15, 21). These studies have been done in areas of the world where chronic zinc deficiency in children is known to occur.

Nutritional therapy for all childhood diarrheas, including those due to ETEC, is an integral part of diarrhea treatment. Episodes of diarrhea due to any cause, including ETEC, result in decreased nutritional status and thus inhibit growth in children (106). Attention to providing food, particularly breast milk, early in the course of therapy is essential. Additional food during and following the diarrheal episode will help in catch-up growth (3).

PREVENTION

Vaccine Development

Prevention of ETEC infection is clearly related to water and sanitation, including food preparation and distribution. In the developing world, such major improvements will be a long time coming (57). It is estimated that it would take US$200 billion to make the improvements necessary to prevent fecally spread diseases in South America alone (135). Other methods on a microscale are presently being done: building safe-water tube wells, chlorination/filtration/heating of drinking water, and building and improving latrines. These attempts to block transmission are certainly effective if implemented but cannot solve the problem quickly. Therefore, there is much interest in the development of vaccines for prevention of ETEC disease.

Based on the great impact of ETEC infections on morbidity and mortality, and probably also on nutritional status (106), particularly of children in areas where they are endemic, an effective ETEC vaccine is highly desirable. Such a vaccine is feasible since epidemiologic evidence and results from experimental challenge studies with human volunteers have demonstrated that specific immunity against homologous strains follows ETEC infection. Furthermore, multiple infections with antigenically diverse ETEC strains seem to lead to broad-spectrum protection against ETEC diarrhea (38). Experimental studies with animals and indirect evidence from clinical trials (191) suggest that protective immunity against ETEC is mediated by secretory immunoglobulin A antibodies directed against the CFs, other surface antigens, and LT; ST, which is a small peptide, does not elicit neutralizing antibodies following natural infection.

To provide broad-spectrum protection, an ETEC vaccine should probably contain fimbrial antigens representative of the most prevalent ETEC pathogens. The great diversity of ETEC serotypes, with regard to both O and H antigens, makes such antigens less attractive as vaccine components. Since CFA/I and CS1 to CS6 are the most common human ETEC fimbriae, they are key candidate immunogens in an ETEC vaccine. Other fimbrial CFs may also be considered, based on their relative importance in certain geographic areas (see Table 5). Since a majority of ETEC strains that produce both LT and ST or ST only produce CFs, it has been postulated that a multivalent ETEC vaccine containing CFA/I and CS1 to CS6 may provide protection against approximately 50 to 80% of ETEC strains in most geographic areas (189). If an LT toxoid such as the nontoxic B subunit LTB or a mutant LT is included, a multivalent toxoid-CF vaccine might provide relatively broad protection against 80 to 90% of ETEC strains worldwide. Inclusion of, e.g., CS7, CS12, CS14, and CS17 might expand the potential spectrum of coverage to up to 90% of all ETEC strains (189). A number of different strategies have been taken to deliver fimbrial and toxin antigens of ETEC to the human immune system to elicit protective immune responses and functional immunological memory.

Purified CFs and Enterotoxoids

Various purified CFs have been tested as oral immunogens but have been considered less suitable since they are expensive to prepare and sensitive to proteolytic degradation (101). To protect the fimbriae from degradation in the stomach, purified CFs have been incorporated into biodegradable microspheres. However, no significant protection was induced by any formulation of purified CFs against subsequent challenge with ETEC expressing the homologous CFs, either when immunizing with high doses of a combination of CS1 and CS3 or recombinantly produced CS6 (93, 101). Since LTB as well as the immunologically cross-reactive cholera toxin B subunit are strongly immunogenic, lack toxicity, are stable in the gastrointestinal milieu, and are capable of binding to the intestinal epithelium, they are suitable candidate antigens to provide anti-LT immunity. The cholera toxin B subunit has also afforded significant protection against ETEC producing LT or LT/ST both in countries where ETEC is endemic and in travelers (36, 127), but it is possible that an LT toxoid might be slightly more effective than cholera toxin B subunit.

An alternative administration route that has been considered is to give an ETEC vaccine by the transcutaneous route. Such administration of E. coli CS6 together with LT has induced immune responses against CS6 in about half of the volunteers and anti-LT responses in all of them (77). Work is in progress to evaluate E. coli LT as a candidate vaccine after transcutaneous immunization (73).

Inactivated Whole-Cell Vaccines

Another approach that has been extensively attempted is to immunize orally with killed ETEC bacteria that express the most important CFs on the bacterial surface together with an appropriate LT toxoid, i.e., cholera toxin B subunit or LTB (189). A vaccine that consists of a combination of recombinantly produced cholera toxin B subunit and formalin-inactivated ETEC bacteria expressing CFA/1 and CS1 to CS5 as well as some of the most prevalent O antigens of ETEC has been extensively studied in clinical trials in travelers as well as in children in areas where ETEC is endemic. This recombinant cholera toxin B (rCTB)-CF ETEC vaccine has been shown to be safe and gave rise to significant immunoglobulin A immune responses in the intestine and increased levels of circulating antibody-producing cells in a majority of adult Swedish volunteers (4). The vaccine has also been well tolerated and given rise to mucosal immune responses against the different CFs of the vaccine in 70% to 100% of volunteers of different age groups from 18 months to 45 years in Egypt and Bangladesh (130, 134, 169-171). However, due to an increased frequency of vomiting in the youngest children (6 to 18 months), a reduced dose of the vaccine, i.e., a quarter dose that can be given safely and with retained immunogenicity to Bangladeshi infants, has been identified (129).

In an initial pilot study, the rCTB-CF ETEC vaccine was shown to confer 82% protective efficacy (P < 0.05) against ETEC disease in European travelers going to 20 different countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America (213). However, the number of cases fulfilling the inclusion criteria was low. In a large placebo-controlled trial in nearly 700 American travelers going to Mexico and Guatemala, the rCTB-CF ETEC vaccine was shown to be effective (protective efficacy, 77%; P = 0.039) against nonmild ETEC diarrheal illness, i.e., disease that interfered with the travelers′ daily activities (153, 193). However, in a recent pediatric study in rural Egypt, the vaccine did not confer significant protection in the 6- to 18-month-old children tested (194).

Live Oral ETEC Vaccines

The potential of live ETEC vaccines has been suggested based on previous findings in human volunteers that a live vaccine strain expressing different CSs afforded highly significant protection against challenge with wild-type ETEC expressing the corresponding CS factors (97). For example, different live multivalent Shigella/ETEC hybrid vaccines have been constructed in which important fimbrial CFs are expressed along with mutated LT (10). Such vaccine candidates have expressed CS2 and CS3 fimbriae or CFA/I, CS2, CS3, and CS4 as well as a detoxified version of human LT (12). These candidate vaccine strains are presently being evaluated for safety and immunogenicity in different animal models, including macaques. The ultimate goal is to produce five different Shigella strains that can express the most important CFs and an LT toxoid simultaneously in the gut.

Another approach has been to utilize attenuated ETEC strains as vectors of key protective antigens, e.g., CS1 and CS3 (203). Evaluation of such mutated strains, PTL002 and PTL003, in human volunteers has shown that they are safe and immunogenic when given in a single dose.

The only vaccine that has been evaluated for protective efficacy in a field trial in young children in areas where ETEC is endemic so far is the rCTB-CF ETEC vaccine. Since this vaccine did not induce significant protection in this important target group, intense efforts should be made to improve the immunogenicity of this or modified ETEC vaccine candidates. As yet, no alternative ETEC vaccine is within reach to be licensed within the next 3 to 5 years.

CONCLUSIONS

Based on the multitude of information presented in this review, we make the following conclusions. ETEC is an underrecognized but extremely important cause of diarrhea in the developing world where there is inadequate clean water and poor sanitation. It is the most frequent bacterial cause of diarrhea in infants, children, and adults living in developing countries and the most common cause of diarrhea in international travelers visiting these areas. ETEC diarrhea is most frequently seen in children, suggesting that a protective immune response occurs with age.

The pathogenesis of ETEC-induced diarrhea, including the production of enterotoxins and colonization in the small intestine, is similar to that of cholera. ETEC diarrhea could well be misdiagnosed as cholera because the diseases have common clinical syndromes and seasonalities. Treatment of ETEC diarrhea by rehydration is similar to that for cholera, but antibiotics are used routinely for ETEC only in the specific circumstances of traveler's diarrhea.