Abstract

The putative carboxyl-terminal processing protease (CtpA) of Brucella suis 1330 is a member of a novel family of endoproteases involved in the maturation of proteins destined for the cell envelope. The B. suis CtpA protein shared up to 77% homology with CtpA proteins of other bacteria. A CtpA-deficient Brucella strain (1330ΔctpA), generated by allelic exchange, produced smaller colonies on enriched agar plates and exhibited a 50% decrease in growth rate in enriched liquid medium and no growth in salt-free enriched medium compared to the wild-type strain 1330 or the ctpA-complemented strain 1330ΔctpA[pBBctpA]. Electron microscopy revealed that in contrast to the native coccobacillus shape of wild-type strain 1330, strain 1330ΔctpA possessed a spherical shape, an increased cell diameter, and cell membranes partially dissociated from the cell envelope. In the J774 mouse macrophage cell line, 24 h after infection, the CFU of the strain 1330ΔctpA declined by approximately 3 log10 CFU relative to wild-type strain 1330. Nine weeks after intraperitoneal inoculation of BALB/c mice, strain 1330ΔctpA had cleared from spleens but strain 1330 was still present. These observations suggest that the CtpA activity is necessary for the intracellular survival of B. suis. Relative to the saline-injected mice, strain 1330ΔctpA-vaccinated mice exhibited 4 to 5 log10 CFU of protection against challenge with virulent B. abortus strain 2308 or B. suis strain 1330 but no protection against B. melitensis strain 16 M. This is the first report correlating a CtpA deficiency with cell morphology and attenuation of B. suis.

Animal brucellosis is a disease affecting various domestic and wildlife species, resulting from infection with bacteria belonging to the genus Brucella (11). Brucellosis is a zoonotic disease, and human infection is normally acquired either through consumption of contaminated dairy and meat products or by contact with infected animal secretions (1). Brucella species are facultative intracellular pathogens that can enter the host via mucosal surfaces and are able to survive inside macrophages. The primary strategy for survival in macrophages appears to be inhibition of phagosome-lysosome fusion (6, 7, 31). This is followed by localization and survival within replicative phagosomal compartments associated with the rough endoplasmic reticulum and has been demonstrated in placental trophoblasts and other nonprofessional phagocytes (3, 24, 36). Molecular characterization of this survival process is important because it would provide additional guidance for the development of measures for prevention and control of Brucella and perhaps other intracellular pathogens.

It is well known that many proteins destined for extracytoplasmic locations are initially synthesized as precursor forms and processed into mature forms by proteolytic cleavage to remove short peptide sequences, near either the amino terminus or the carboxyl terminus. The endoproteases responsible for cleaving of amino-terminal peptides are called amino-terminal processing proteases (13). A relatively new class of endoproteases with carboxyl-terminal processing activities has been described for various bacteria and organellar systems, including cyanobacteria, Escherichia coli, and chloroplasts (23, 35, 42, 46). These carboxyl-terminal proteases (Ctps) from cyanobacteria, E. coli, and green plants share significant sequence similarities (21, 33). However, none of them exhibits sequence homology with other protease classes with well-defined mechanisms of action. Ctps are serine proteases that utilize a Ser/Lys catalytic dyad instead of the well-known Ser/His/Asp catalytic triad (34).

The bacterial cell shape is defined by peptidoglycan, a rigid layer vital for bacterial survival, as it is the anchor for both inner and outer cell membranes in gram-negative bacteria. The building blocks for the synthesis of peptidoglycan are created in the cytoplasm, transported across the cytoplasmic membrane, and polymerized on the outer surface of the inner membrane (20, 30). Complete assembly of peptidoglycan requires a glycosyltransferase that polymerizes the glycan strands and a transpeptidase activity that cross-links the strands via their peptide side chains. These activities are performed by a group of enzymes called penicillin-binding proteins (PBP) (50). The fact that β-lactam antibiotics like penicillin irreversibly bind to these enzymes led to naming them PBPs (53). Through their influence on the synthesis of the cell wall peptidoglycan layer, the PBPs strongly influence the size, shape, and time of division of bacteria (50).

The enzymes of the PBP-1 family are believed to determine the size and the growth of the bacterial cell. These PBPs act as peptidoglycan synthetases because they provide both the glycosyltransferase and transpeptidase activities that are required to polymerize peptidoglycan (37, 54). The enzymes of the PBP-2 and PBP-3 families are believed to determine the extent of elongation and division of rod-shaped cells. These enzymes form peptide cross-links between the glycan chains of peptidoglycan (20, 30, 37).

The carboxyl-terminal protease Prc is responsible for cleavage of C-terminal 11-amino-acid residues of precursor PBP-3 of E. coli (19). The E. coli mutant JE7304, developed by deleting the prc gene encoding Prc protein, was defective in the C-terminal processing of PBP-3 (18). This mutant showed thermosensitive growth on a salt-free L-agar plate, suggesting that the prc gene was involved in some essential cellular process, which may be related to the cell division function of PBP-3 (19). The prc function thus seemed to be involved in maintaining cell wall integrity and protection from thermal and osmotic stresses. Loss of Prc function also resulted in leakage of periplasmic proteins, including RNase I and alkaline phosphatase (19). The leaky phenotype of the prc mutant has been attributed to the impairment of the structural integrity of the outer membrane, which could lead to sensitivity to osmotic stress. A Prc-deficient E. coli strain exhibited a filamentous cell morphology, confirming the role of Prc on processing of PBP-3 (19).

The protein encoded by the ctpA gene of Brucella suis shared considerable homology with the Ctps of other bacteria. Therefore, we hypothesized that the protein encoded by this gene is a C-terminal protease and could play a significant role in determining the cell morphology and the intracellular persistence of B. suis through its possible influence on cell envelope integrity. In this communication, we report that a B. suis strain defective in ctpA gene exhibits salt-sensitive growth, spherical cell morphology, and reduced persistence in mice and a mouse macrophage cell line.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and reagents.

Brucella abortus strain 2308, Brucella melitensis strain 16 M, and B. suis strains 1330 and VTRS1 were obtained from our culture collection. E. coli strain Top10 (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, Calif.) was used for producing plasmid constructs. E. coli Prc mutant strain JE7929 was kindly provided by H. Hara, Saitama University, Urawa City, Japan. E. coli cells were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or on LB agar (Difco Laboratories, Sparks, Md.). Brucellae were grown in LB broth with or without sodium chloride at 30, 37, or 42°C to determine whether growth was osmosensitive and/or thermosensitive. For all other assays, brucellae were grown either in Trypticase soy broth (TSB) or on Trypticase soy agar (TSA) plates (Difco) at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2 as previously described (44). The plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Bacteria containing plasmids were grown in the presence of ampicillin or kanamycin at a 100-μg/ml concentration (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Description of the plasmids and bacterial strains used in this study

| Plasmid or strain | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR2.1 | TA cloning vector, 3.9-kb, Ampr | Invitrogen |

| pCRctpA | pCR2.1 with 1.4-kb insert containing the B. suis ctpA gene; Ampr | This study |

| pGEM-3Z | Cloning vector, 2.74-kb, Ampr | Promega |

| pGEMctpA | pGEM-3Z with 1.4-kb insert containing the B. suis ctpA gene from pCRctpA; Ampr | This study |

| pUC4K | Cloning vector, 3.9-kb, Kanr, Ampr | Pharmacia |

| pGEMctpAK | pGEMctp with 0.5-kb BclI fragment deleted and blunt ended and a 1.3-kb SalI-cut and blunt-ended Kanr cassette from pUC4K ligated, Kanr, Ampr | This study |

| pBBR4MCS | Broad-host-range vector; Cmr | 25 |

| pBBctpA | pBBR4MCS with 1.4-kb insert containing the B. suis ctpA gene from pCRctpA; Ampr | This study |

| Strains | ||

| Escherichia coli | ||

| Top10 | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 deoR recA1 araD139 Δ(ara-leu) 7697 galU galK rpsL (StrR) endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| JE7929 | Prc mutant | 17 |

| Brucella abortus 2308 | Parent-type, smooth strain | G. G. Schurig |

| Brucella melitensis 16 M | Parent-type, smooth strain | G. G. Schurig |

| Brucella suis 1330 | Parent-type, smooth strain | G. G. Schurig |

| 1330ΔctpA | ctpA deleted mutant of 1330, Kanr | This study |

| 1330ΔctpA[pBBctpA] | Strain 1330 containing pBBctpA, Kanr, Ampr | This study |

| VTRS1 | wboA deletion mutant of B. suis, Kanr | 51 |

All experiments with live brucellae were performed in a Biosafety Level 3 facility at the Infectious Disease Unit of the Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-approved standard operating procedures.

Recombinant DNA methods.

Genomic DNA was isolated from B. suis strain 1330 by use of a QIAGEN blood and tissue DNA kit (QIAGEN Inc., Valencia, Calif.). Plasmid DNA was isolated using plasmid Mini- or Midiprep purification kits (QIAGEN). Restriction digests, Klenow reactions, and ligations of DNA were performed as described elsewhere (41). Restriction enzymes, Klenow fragment, and T4 DNA ligase enzyme were purchased from Promega Corporation (Madison, Wis.). Ligated plasmid DNA was transferred to E. coli Top10 cells by heat shock transformation per the guidelines of the manufacturer (Invitrogen). Purified plasmid DNA was electroporated into B. suis with a BTX ECM-600 electroporator (BTX, San Diego, Calif.), as described previously (28).

DNA and protein sequence analyses.

The nucleotide sequence of the ctpA gene was analyzed with DNASTAR software (DNASTAR, Inc., Madison, Wis.). The presence of any signal sequence of the B. suis CtpA protein was predicted by using the SignalP 3.0 server of the Technical University of Denmark (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/) (9). The destination of the CtpA protein upon translation and processing was predicted using the Subloc v1.0 server of the Institute of Bioinformatics of the Tsinghua University (http://www.bioinfo.tsinghua.edu.cn/). Homology of the B. suis CtpA to proteins of the EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ databases was analyzed using the BLAST software (2) at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (Bethesda, MD).

Mutation of the B. suis ctpA gene by allelic exchange.

A 1,408-bp region including a major portion of the ctpA gene was amplified via PCR using the genomic DNA of B. suis. A primer pair consisting of a forward primer (5′ GGGGTACCGTGGTGGACTGA 3′) and a reverse primer (5′ GGCTGCAGTCCCGCGTTTTTGTCTT 3′) (Ransom Hill Bioscience, Inc., Ramona, Calif.) was designed based on the nucleotide sequence (GenBank accession no. NC_004310); a restriction site was engineered into each primer (KpnI in the forward primer and PstI in the reverse primer; shown in boldface characters in the primer sequences). PCR amplification was performed in an Omni Gene thermocycler (Hybaid, Franklin, Mass.) at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles that each included 1 min of denaturation at 95°C, 1 min of annealing at 59.7°C, and 3 min of extension at 72°C. The amplified gene fragment was cloned into the pCR2.1 vector of the TA cloning system (Invitrogen) to produce plasmid pCRctpA. Competent E. coli Top10 cells (Invitrogen) were transformed with the ligation mixture, and the colonies carrying the recombinant plasmid were picked from TSA plates containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml) per the manufacturer's guidelines. From this plasmid, the ctpA gene was isolated by KpnI and PstI digestion and cloned into the same sites of plasmid pGEM-3Z (Promega). The resulting 4.2-kb plasmid was designated pGEMctpA. The E. coli Top10 cells carrying the recombinant plasmid were picked from TSA plates containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml). The suicide vector pGEMctpAK was constructed as follows: the plasmid pGEMctpA was digested with BclI to delete a 471-bp region from the ctpA gene. The BclI sites on the 3.7-kb plasmid were filled in by reaction with Klenow enzyme and ligated to the 1.3-kb SalI fragment of pUC4K (also blunt ended) containing the Tn903 npt gene (40), which confers kanamycin resistance (Kanr) to B. suis. The resulting suicide vector was designated pGEMctpAK. The E. coli Top10 cells carrying the recombinant plasmid were picked from TSA plates containing kanamycin (100 μg/ml).

One microgram of pGEMctpAK was used to electroporate B. suis strain 1330; several colonies of strain 1330 were obtained from a TSA plate containing kanamycin (100 μg/ml). These colonies were streaked on TSA plates containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml) to determine whether a single- or double-crossover event had occurred. Three of the colonies did not grow on ampicillin-containing plates, suggesting that a double-crossover event had occurred. PCR with the primers used for amplifying the ctpA gene (as described above) confirmed that a double-crossover event had taken place in all three transformants. One of these strains was chosen for further analyses and designated 1330ΔctpA.

Complementation of ctpA gene activity in mutant 1330ΔctpA.

The 1.4-kb DNA fragment containing the B. suis ctpA gene was isolated by SacI and XbaI digestion of plasmid pCRctpA and was cloned into same sites of broad-host-range vector pBBR4MCS (25). The resulting plasmid was designated pBBctpA. One microgram of pBBctpA was used to electroporate B. suis strain 1330ΔctpA; several colonies of strain 1330ΔctpA were picked from a TSA plate containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml). Six of the colonies were tested for growth on TSA plates, in LB broth, or in salt-free LB broth. On TSA plates, these colonies appeared equal in size to that of the wild-type strain 1330, and in LB or salt-free LB broth they grew similarly to strain 1330. One of these colonies was chosen for further analyses and designated 1330ΔctpA[pBBctpA].

Complementation of prc gene activity in Prc-deficient E. coli.

One microgram of pBBctpA was used to electroporate the Prc mutant E. coli strain JE7929; several colonies of strain JE7929 were picked from a TSA plate containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml). Ten of the colonies were tested for growth in salt-free LB media (details to follow).

Growth rates of B. suis strains in regular or salt-free medium at different temperatures.

Salt-free LB medium was prepared by mixing bactotryptone and yeast extract in water per the manufacturer's instruction (Difco) but omitting sodium chloride. Single colonies of strains 1330, 1330ΔctpA, and 1330ΔctpA[pBBctpA] were grown at 37°C for 24 h to stationary phase in 10 ml of TSB. The cells were harvested in two equal pellets by centrifugation. One pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of LB broth and used to inoculate 25 ml of LB broth in a Klett side-arm flask to 12 to 16 Klett units. The other pellet was resuspended in salt-free LB medium and used to inoculate 25 ml of salt-free LB broth in a Klett flask to 8 to 16 Klett units. Cultures were grown at 30, 37, or 42°C at 180 rpm; Klett readings were recorded every two h in a Klett-Summerson colorimeter (New York, NY).

Acid precipitation and denaturing gel electrophoresis of secreted proteins.

Strains 1330, 1330ΔctpA, and 1330ΔctpA[pBBctpA] were grown in 25 ml LB broth to stationary phase (to 339, 179, and 288 Klett units, respectively). The cultures were centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 15 min, and the cell-free culture medium was collected. Trichloroacetic acid was added to the medium at 5% of the final volume and incubated at 4°C overnight. The acidified medium was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 min to collect the protein precipitate. The insoluble material was resuspended in Laemmli sample buffer (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.), boiled for 20 min, and electrophoresed on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels according to standard procedures (26). Gels containing the separated proteins were either stained with Coomassie brilliant blue G (Sigma Chemical Co.) or used for Western blot analysis.

Western blotting.

Western blotting was performed as previously described (49a). Briefly, proteins separated by SDS-PAGE were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane by using a Trans-blot semidry system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The membranes were blocked with a solution of 1.5% nonfat milk powder plus 1.5% bovine serum albumin. For analysis of trichloroacetic acid-insoluble proteins, the membranes were incubated with goat anti-heat-killed B. abortus polyclonal serum (Goat-48) for 24 h and subsequently developed with rabbit anti-goat immunoglobulin G (whole molecule) conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Sigma Chemical Co.).

Electron microscopy.

Strains 1330 and 1330ΔctpA were grown in 25 ml LB broth to stationary phase. The cultures were centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 15 min to harvest the cells. One half of the pellet from each strain was used to inoculate 100 ml LB broth, whereas the other half was used to inoculate 100 ml salt-free LB broth. The cultures were incubated overnight at 37°C with vigorous shaking. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 15 min and fixed overnight at 4°C in formaldehyde-paraformaldehyde in cacodylate buffer (8). The samples were then processed for thin-section electron microscopy as described by Banai et al. (8). The sections were mounted on copper grids, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined with a JOEL 100 CX-II transmission electron microscope (Zeiss 10C; Carl Zeiss Inc., New York, NY) at ×10,000 magnification.

Preparation of B. suis inoculum stocks.

TSA plates were inoculated with single colonies of B. suis strains. After 4 days of incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2, the cells were harvested from plates, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), resuspended in 20% glycerol, and frozen at −80°C. The number of viable cells was determined after dilutions of the cell suspensions were plated on TSA.

Persistence of recombinant B. suis strains in macrophages.

The mouse macrophage-like cell line J774 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The J774 macrophage cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 105/ml in Dulbecco's modified essential medium (Sigma-Aldrich) into 24-well tissue culture dishes and cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 until confluent. The tissue culture medium was removed, 200 μl (108 cells) of the bacterial suspension in PBS was added, and the cells were incubated at 37°C for 4 h. The suspension above the cell monolayer was removed, and the cells were washed three times with PBS. One milliliter of Dulbecco's modified essential medium containing 25 μg of gentamicin was added, and the cells were incubated for 48 h at 37°C. At various time points (0, 24, and 48 h of incubation), the growth medium was removed, the cells were washed with PBS, and 500 μl of 0.25% sodium deoxycholate was added to lyse the infected macrophages. After 5 min the lysate was diluted in PBS, and the number of viable cells was determined after growth at 37°C for 72 h on TSA plates. Triplicate samples were taken at all time points, and the assay was repeated two times.

Survival of recombinant B. suis strains in mice.

Six-week-old female BALB/c mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, Mass.) were allowed 1 week of acclimatization. Groups of seven or eight mice each were intraperitoneally injected with 5.0 to 5.3 log10 CFU of B. suis strain 1330 or 1330ΔctpA or rough B. suis strain VTRS1 (51). Mice were sacrificed at 6 weeks after inoculation, and the Brucella CFU count per spleen was determined as described previously (44). Briefly, spleens were collected and homogenized in TSB. Serial dilutions of each spleen's homogenates were plated on TSA plates. The number of CFU that appeared on plates was determined after 4 days of incubation at 37°C.

To determine the clearance of strains in different time intervals, groups of 25 mice were each injected with 4.0 to 4.1 log10 CFU of B. suis strains 1330 or 1330ΔctpA. Groups of five mice injected with each strain were sacrificed at 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 weeks after inoculation, and the Brucella CFU count per spleen was determined as described above.

Protective efficacy of B. suis mutant 1330ΔctpA.

Six-week-old female BALB/c mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) were allowed 1 week of acclimatization. Groups of seven mice each were intraperitoneally injected with PBS, strain 1330ΔctpA, or strain VTRS1. Two doses of strain 1330ΔctpA or VTRS1, i.e., a high dose, which was similar to the dose used in clearance study, and a low dose, which was 1 log10 CFU lower than the above-described dose, were used in vaccination. Eight weeks postinoculation, mice were intraperitoneally challenged with 4.7 log10 CFU of wild-type, virulent B. suis strain 1330. Two weeks postchallenge, mice were sacrificed and the Brucella CFU count per spleen was determined as described above. In a separate trial, 10 BALB/c mice were intraperitoneally injected with PBS, and another 12 were inoculated with 5.3 log10 CFU of strain 1330ΔctpA. Six weeks postinoculation, five mice injected with PBS and six mice inoculated with strain 1330ΔctpA were intraperitoneally challenged with 3.5 log10 CFU of wild-type, virulent B. abortus strain 2308. The other five mice injected with PBS and the six mice inoculated with strain 1330ΔctpA were challenged with 5.1 log10 CFU of wild-type, virulent B. melitensis strain 16 M. Two weeks postchallenge, mice were sacrificed and the Brucella CFU count per spleen was determined as described above.

Data analyses.

The mean and the standard deviation values from the clearance and protection studies were calculated using the Microsoft Excel 2001 program (Microsoft Corporation). The Student t test was performed in the analysis of CFU data in the macrophage study and the protection study involving strain 2308 and 16 M challenge. The CFU data from the splenic clearance study and the protection study involving strain 1330 challenge were analyzed by performing analysis of variance, and the mean CFU counts among treatments were compared using the least-significance pair-wise comparison procedure (49).

RESULTS

Nucleotide and protein sequence of ctpA.

The coding region of the ctpA gene is 1,274 bp long and is located between bp 1768433 and 1769707 on chromosome I of the B. suis genome (accession number NP_698817). The predicted molecular mass of CtpA was 45.2 kDa. Analysis of the putative CtpA protein sequence predicted that it does not contain a signal sequence (signal peptide probability: 0.006). The predicted subcellular localization of CtpA was periplasmic space (reliability index = 2; expected accuracy = 85%).

At the amino acid level, the ctpA gene shared 99% identity with the tail-specific protease of B. melitensis. Additionally, it showed up to 77% identity with carboxyl-terminal proteases of a number of bacterial species, including Bartonella quintana, Mesorhizobium loti, Sinorhizobium meliloti, and Agrobacterium tumefaciens, and up to 61% identity with periplasmic proteases of other bacteria, including Rhodopseudomonas palustris, Rhodobacter sphaeroides, and Magnetospirillum magnetotacticum (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Percentages of identity of B. suis CtpA to protein sequences in GenBank

| Bacterial species | Protein | Identity to B. suis CtpA (%) | GenBank accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brucella melitensis | Tail-specific proteinase | 99 | NP_539132.1 |

| Mesorhizobium loti | Carboxyl-terminal protease | 77 | NP_104979.1 |

| Bartonella quintana | Carboxyl-terminal protease | 72 | Q44879 |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | Carboxy-terminal proteinase | 71 | NP_355704.1 |

| Sinorhizobium meliloti | Carboxy-terminal protease | 71 | NP_387272.1 |

| Bradyrhizobium japonicum | Carboxy-terminal protease | 59 | NP_771462.1 |

| Pseudomonas species | Carboxyl-terminal protease | 52 | NP_747159.1 |

| Escherichia coli | Carboxyl-terminal protease (Prc) | 31 | D00674.1 |

| Rhodopseudomonas palustris | Periplasmic protease | 61 | ZP_00009772.1 |

| Rhodobacter sphaeroides | Periplasmic protease | 61 | ZP_00007601.1 |

| Magnetospirillum magnetotacticum | Periplasmic protease | 53 | ZP_00054906.1 |

| Azotobacter vinelandii | Periplasmic protease | 50 | ZP_00089764.1 |

| Microbulbifer degradans | Periplasmic protease | 50 | ZP_00065626.1 |

Genomic characterization of CtpA-deficient B. suis strain.

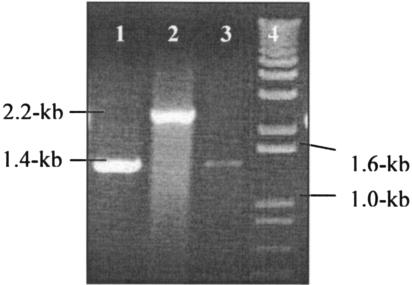

A PCR assay with the primer pair used to amplify the ctpA gene (see Materials and Methods) produced a predicted 1.4-kb-size amplicon not only from the parent type B. suis but also from B. abortus, B. canis, and B. melitensis (data not shown). These primers yielded an approximately 2.2-kb product from strain 1330ΔctpA (Fig. 1), indicating that due to a double-crossover event, a 471-bp region was deleted from the ctpA gene, and the 1.3-kb Kanr fragment was inserted at the deletion site of the strain 1330 genome.

FIG. 1.

Detection of the double-crossover event in strain 1330ΔctpA. B. suis strains were harvested and boiled for 30 min, and extracts were clarified by centrifugation. The supernatant was used as a template for PCR using the forward and the reverse primers (see Materials and Methods). Strain 1330 amplified a 1.4-kb fragment, whereas strain 1330ΔctpA amplified a 2.2-kb fragment. Lanes 1 and 3, strain 1330; lane 2, strain 1330ΔctpA; lane 4, 1-kb DNA ladder.

Growth rates of recombinant B. suis strains.

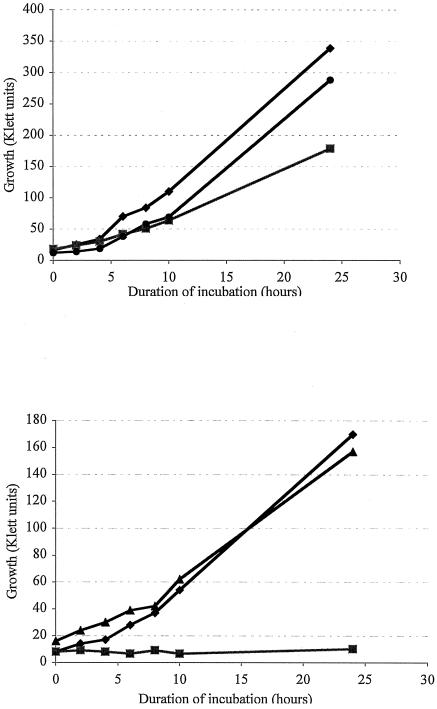

After 3 days of growth on TSA plates, colonies of strain 1330ΔctpA appeared approximately one-third to one-half the size of the colonies of strain 1330 (data not shown). In LB broth, the growth of the strain 1330ΔctpA was slower (approximately 9 h doubling time) than that of strain 1330 (approximately 6 h doubling time) (Fig. 2, top). In salt-free LB broth, the CtpA-deficient strain exhibited zero growth, whereas strain 1330 grew with approximately 8.5 h doubling time (Fig. 2, bottom). The growth rates of strain 1330 versus 1330ΔctpA did not differ as a function of temperature, i.e., at 30, 37, or 42°C, both the strains grew at rates similar to that described above (data not shown). Colonies of strain 1330ΔctpA complemented with the ctpA gene appeared equal in size to that of strain 1330 on TSA plates (data not shown). The ability of strain 1330ΔctpA to grow in salt-free broth was restored when the ctpA gene was introduced into this strain (strain 1330ΔctpA[pBBctpA]). Additionally, the complemented strain grew at rates similar to those seen with strain 1330 in LB or salt-free LB broth, i.e., 6 or 10 h doubling time, respectively (Fig. 2). However, the salt-sensitive growth of Prc-deficient E. coli strain JE7929 could not be restored when the B. suis ctpA gene was introduced into this strain.

FIG. 2.

Growth of B. suis strains 1330 (♦), 1330ΔctpA (▪), and 1330ΔctpA[pBBctpA] (•). All cultures were grown at 42°C at 180 rpm. Changes in cell density were recorded every 2 h in a Klett-Summerson colorimeter. (Top) Growth of strains in LB media. (Bottom) Growth of strains in salt-free LB media.

Leakage of periplasmic proteins.

To find out any possible leakage of proteins, the proteins from culture supernatants were precipitated with acid and subjected to immunoblotting. No significant differences were observed between strain 1330 and strain 1330ΔctpA, as judged by staining of precipitated proteins separated by SDS-PAGE. No visible immunoreactive proteins were seen on Western immunoblots using hyper-immune anti-Brucella goat serum (data not shown), indicating that disruption of the ctpA gene does not cause gross leakage of proteins from Brucella cells.

Cell morphology.

When examined by electron microscopy, the wild-type strain 1330 grown in LB medium with or without salt displayed the native coccobacillus shape of Brucella cells (Fig. 3A and B). In contrast, the CtpA-deficient strain 1330ΔctpA grown in LB broth displayed a spherical shape and a slightly increased diameter. Additionally, the outer membrane of these cells partially dissociated from the rest of the cell envelope (Fig. 3C). When strain 1330ΔctpA was introduced into salt-free growth broth, the cell size increased substantially and the cell membrane was significantly dissociated; the cells appeared to be almost spheroplast-like (Fig. 3D).

FIG. 3.

Cell morphology of B. suis as observed by electron microscopy. Strain 1330 grown in LB medium (A) or salt-free LB medium (B) displayed native coccobacillus shape of Brucella cells. The cells from strain 1330ΔctpA grown in LB medium with salt (C) acquired a spherical shape, with a slightly increased cell diameter. The outer membrane apparently separated from some of the cells. The cells from strain 1330ΔctpA grown in LB medium without salt (D) lost cell integrity, with the cell membranes substantially dissociating from the cell envelope.

Persistence of B. suis strains in J774 macrophages.

The survival of B. suis strains in J774 mouse macrophage cells was measured (Table 3). The results reflect a 3.09 log10 decline of the CtpA-deficient strain compared with the parent type strain 1330 by 24 h but eventual recovery of the CtpA-deficient strain by 48 h.

TABLE 3.

Viability of B. suis strains in mouse macrophage J774 cells

| Strain | Recovery of brucellae from macrophages (mean ± SE log10 CFU/well)a

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 24 h of incubation | 48 h of incubation | |

| 1330 (parent) | 5.37 ± 0.78 | 5.29 ± 0.34 |

| 1330ΔctpA | 2.28 ± 0.21 | 5.01 ± 0.15 |

P values for the difference between mean values were <0.005 for 24 h of incubation and >0.1 for 48 h of incubation.

Survival in mice of the B. suis strains.

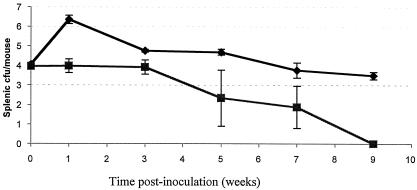

Survival in BALB/c mice of the CtpA-deficient strain was compared with that of the wild-type strain 1330 and the rough B. suis strain VTRS1 (51) (Table 4). The virulent parent type strain 1330 persisted in mice for more than 6 weeks with only 0.83 log10 CFU decline, whereas strain 1330ΔctpA declined by 3.21 log10 CFU and strain VTRS1 declined by 2.92 log10 CFU during the same period. In a separate trial, the splenic clearance of strains was estimated at 2-week intervals (Fig. 4). One week after inoculation, the average splenic recovery of the strain 1330ΔctpA remained at 4.0 log10 CFU, while recovery was 2.1 log10 CFU higher for the parent strain. At 5 and 7 weeks postinoculation, strain 1330ΔctpA had been cleared from some mice, causing relatively larger CFU standard deviation values. Nine weeks postinoculation, strain 1330ΔctpA cleared from spleens of all the mice but the parent strain 1330 was still present.

TABLE 4.

Clearance of B. suis strains from BALB/c mouse spleens

| Strain | Gene interrupted by knockout mutagenesis | Phenotypea | Injected dosage (log10 CFU/mouse) | CFU 6 weeks after inoculation (mean + SE log10/spleen)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1330 (parent) | Smooth | 5.24 | 4.41 ± 0.18† | |

| 1330ΔctpA | Carboxyl-terminal protease (ctpA) | Smooth | 5.25 | 2.04 ± 0.89c‡ |

| VTRS1 | Mannosyltransferase (wboA) | Rough | 4.97 | 2.05 ± 1.08d‡ |

Assessed with crystal violet colony staining.

P value for the difference among mean values was <0.005. The mean value of a strain designated by a dagger is significantly different from the mean value of a strain designated by a double dagger but is not significantly different between strains designated by the same symbol.

Completely cleared in one out of eight mice.

Completely cleared in one out of seven mice.

FIG. 4.

Splenic clearance of B. suis strains 1330 (♦) and 1330ΔctpA (▪) following inoculation. Mice were intraperitoneally inoculated with strains, and the splenic CFU counts were determined at 1, 3, 5, 7, or 9 weeks postinoculation. Each data point represents the mean values from five inoculated mice.

Protective efficacy of attenuated B. suis strains.

Mice immunized with 4.34 and 5.34 log10 CFU of the strain 1330ΔctpA exhibited 3.20 and 3.75 log10 units of protection, respectively (Table 5), against a challenge of wild-type B. suis strain 1330. All colonies harvested from spleens of mice injected with this strain were sensitive to kanamycin (Kans), indicating that they all were from the challenge strain 1330 (Kans), as opposed to the vaccine strain 1330ΔctpA (Kanr). In comparison, strain VTRS1 provided no protection when mice were vaccinated with 4.20 log10 CFU but provided 1.26 log10 CFU protection when vaccinated with 5.20 log10 CFU dose. Nearly one-quarter of the colonies harvested from mice immunized with 5.20 log10 CFU of strain VTRS1 were resistant to kanamycin, indicating that the VTRS1 dose had not been completely cleared from the spleens in 10 weeks. In a separate trial, it was shown that immunization with the CtpA-deficient strain 1330ΔctpA induced 4.71 and 0.37 log10 CFU units of protection against challenge with virulent B. abortus parent type strain 2308 and virulent B. melitensis parent type strain 16 M, respectively (Table 6).

TABLE 5.

Protection induced by recombinant B. suis strains against challenge with B. suis virulent strain 1330

| Vaccine strain | Dose injected (log10 CFU/mouse) | Recovery of strain 1330 (mean ± SE log10 CFU/spleen)a | Units of protection | Spleen sizeb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBS | 5.90 ± 0.24† | Larger than normal | ||

| VTRS1 | Low dose (4.20) | 5.91 ± 0.54† | −0.01 | Larger than normal |

| High dose (5.20) | 4.64 ± 0.39‡ | 1.26 | Normal | |

| 1330ΔctpA | Low dose (4.34) | 2.70 ± 0.55$ | 3.20 | Normal |

| High dose (5.34) | 2.15 ± 0.96$ | 3.75 | Normal |

The P value for the difference among mean values was <0.005. Mean values carrying different superscripts (e.g., dagger, double dagger, and dollar sign) are significantly different, but mean values for those carrying the same superscript are not significantly different.

The spleen size of mice that were not infected with any bacteria was considered normal.

TABLE 6.

Protection induced by recombinant B. suis strain 1330ΔctpA against challenge with B. abortus virulent strain 2308 and B. melitensis virulent strain 16 M

| Inoculation | Dose injected (log10 CFU/mouse) | Challenge strain | Challenge dose (log10 CFU/mouse) | Recovery of challenge strain (mean ± SE log10 CFU/spleen)b | Units of protection (log10 CFU/mouse) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBS | 2308 | 3.51 | 5.03 ± 0.07 | 4.71 | |

| 1330ΔctpA | 5.32 | 2308 | 3.51 | 0.32 ± 0.78a | |

| PBS | 16 M | 5.14 | 5.62 ± 0.29 | 0.37 | |

| 1330ΔctpA | 5.32 | 16 M | 5.14 | 5.25 ± 0.31 |

Completely cleared in five out of six mice.

P values for the difference between mean values were <0.001 for mice challenged with strain 2308 and >0.1 for those challenged with strain 16 M.

DISCUSSION

The deduced protein encoded by the ctpA gene was predicted to localize in the periplasmic space of the cell. This protein sequence showed substantial homology with the carboxyl-terminal proteases and periplasmic proteases of other related bacterial species. It further showed 31% homology at the amino acid level to the Prc protein identified as the carboxyl-terminal processing protease for PBP-3 of E. coli (19, 46). Cell fractionation studies had indicated that Prc is localized in the periplasmic space of E. coli (19). On the basis of the greater homology between bacterial carboxyl-terminal proteases and periplasmic proteases, we believe that these two protein groups are the same, even though they had been named differently.

Compared to the parent strain, the CtpA-deficient strain produced relatively smaller colonies on TSA plates and exhibited slower growth in liquid growth media, suggesting that the function of CtpA is important for the growth of B. suis. The inability of the CtpA-deficient strain to grow in salt-free media suggests that CtpA function is involved either directly or indirectly in protection from osmotic stresses.

Brucella suis CtpA shared considerable homology with the E. coli Prc protein, and the CtpA-deficient B. suis and the Prc-deficient E. coli strains (19) displayed similar salt-sensitive growth levels. The Prc protein processes PBP proteins and regulates the cell morphology of E. coli (19). Accordingly, we tested whether CtpA is involved in determining the cell morphology of B. suis. Electron microscopy data revealed that the CtpA-deficient B. suis strain possessed a spherical cell shape with a slightly increased cell diameter. Previous reports have shown that the PBP-2-deficient E. coli strains lack the cell elongation pathway and grow as spherical cells, because only septal synthesis is active in these strains (16). Additionally, in E. coli, when PBP-2 is inhibited by amdinocillin (which inhibits sidewall elongation by PBP-2 homologs), the diameter of newly formed poles increases by up to 26% (14, 16). Similarly, the diameter of the peptidoglycan stalk of Caulobacter crescentus increases when its PBP-2 homolog is inactivated (45). A PBP-2-deficient strain of Erwinia amylovora displayed a large spherical phenotype, whereas its parent type counterpart displayed a rod-shaped phenotype (29). These reports suggest that PBP-2 enzyme helps to regulate cellular diameter at the time of division. Based on these observations it can be hypothesized that the CtpA protein is involved in processing of PBP-2 enzyme in B. suis, and disruption of ctpA resulted in a spherical cell shape with an increased cell diameter. Since the PBPs are involved in cell wall peptidoglycan synthesis, the loss of cell wall integrity and dissociation of cell membranes of the CtpA-deficient B. suis strain can be related to the possible interruption of peptidoglycan synthesis due to inhibition of PBP activity as a result of a lack of CtpA activity.

In E. coli, PBP-3 redirects most peptidoglycan synthesis to the invaginating septum (15, 52) and thereby induces cell septation (47, 48). Inhibition of PBP-3 activity blocks formation of septa and thereby blocks cell division. In E. coli, the antibiotic mezlocillin at low concentrations binds preferentially to PBP-3 and as a result induces filamentous phenotype of cells (12). As described above, in E. coli, PBP-3 is processed into a mature form by the protein Prc, and the Prc-deficient mutants of E. coli failed to process PBP-3 and produced a filamentous phenotype (19). Because of CtpA protein's homology to Prc, and due to similarities in salt sensitivity between Prc-deficient E. coli and CtpA-deficient B. suis, we anticipated seeing a filamentous cell shape in the CtpA-deficient B. suis strain. However, CtpA-deficient B. suis did not exhibit such a morphology; therefore, we conclude that CtpA does not have an impact on PBP-3. Interestingly, the B. suis genome does not carry a gene encoding a protein homologous to PBP-3 of other bacteria but does contain three PBP-1 homologs, one PBP-2 homolog, and three PBP-6 homologs (accession numbers NC_004310 and NC_004311.2).

It has been shown that cell diameter is reduced by about 20% and that the average cell length increases in a PBP-1 mutant of B. subtilis (27, 38, 39). Since the CtpA-deficient B. suis strain exhibited a spherical cell shape, it is apparent that CtpA in Brucella cells may not influence PBP-1 activity. However, further work is required to confirm CtpA's definite involvement in regulating the activities of PBP-2 and/or other PBPs. Work is under way in our laboratory to mutate each gene encoding PBP enzymes of B. suis. If the CtpA-deficient strain exhibits morphology similar to that seen with any of the generated PBP-deficient strains, we can confirm that CtpA influences the function of that particular PBP(s).

Further phenotypical and functional differences were seen between the CtpA-deficient B. suis strain and the Prc-deficient E. coli mutant (19). The Prc-deficient E. coli grew in salt-free media at low temperatures (30°C) but not at high temperatures (42°C), exhibiting temperature dependency. In contrast, the CtpA-deficient B. suis strain did not grow at any temperature when it was introduced into salt-free media, indicating that CtpA in Brucella cells does not have a temperature dependency. Hara et al. (19) reported that disruption of Prc expression of E. coli resulted in leakage of proteins from cells. However, the mutation in the ctpA gene of B. suis did not cause leakage of proteins in substantial quantities, as seen by staining or Western blotting; however, these detection methods may not be sensitive enough to trace any small-scale leakages. When the ctpA gene was introduced into Prc-deficient E. coli by transformation, its growth in salt-free media could not be restored. This may be due to significant functional differences between the Prc of E. coli and the CtpA of Brucella strains; i.e., Prc is involved in processing of PBP-3 whereas CtpA is apparently involved in processing of PBP-2.

Colonies produced by the CtpA-deficient strain complemented with the ctpA gene were similar in size to those produced by the parent type strain 1330. Additionally, the complemented strain grew at a rate similar to that of the parent type strain in LB or salt-free LB media. These results indicate that complementation of the ctpA gene has restored the CtpA activity of mutant 1330ΔctpA, and the phenotype of strain 1330ΔctpA is the result of a specific mutation in ctpA and not a polar effect.

When grown in J774 macrophages, the persistence of the CtpA-deficient strain compared to that of wild-type strain 1330 declined significantly after 24 h of incubation, indicating that CtpA is important for survival, in particular against early killing by macrophages. Apparently, due to the loss of cell wall integrity, the CtpA-deficient cells were unable to avoid phagosome-lysosome fusion and thereby were subjected to early killing. The clearance studies in mice revealed that 1 week after inoculation, a significantly smaller number of strain 1330ΔctpA bacteria were recovered compared to those of the wild-type strain 1330. Nine weeks after inoculation, the CtpA-deficient strain was cleared completely from mouse spleens, whereas the parent type strain was still present. Overall, the slow growth of this mutant strain in enriched media, and its low persistence in mice and greater sensitivity to killing by mouse macrophages, suggests that it has a diminished capacity for extracellular and intracellular growth. This is similar to the observed attenuation exhibited by PBP-2-deficient E. amylovora in mice (29). E. coli mutants lacking both PBP-1a and -1b were nonviable, confirming that one or the other of these enzymes is essential for persistence of the bacterium (22, 54). Thus, if the CtpA of B. suis truly influences the processing of PBPs and peptidoglycan integrity, the reduced persistence of CtpA-deficient B. suis is not totally unexpected.

The CtpA-deficient strain induced excellent protection against challenge with virulent parent type B. suis strain 1330, and the level of protection slightly increased with an increased vaccine dose. The protection induced by the CtpA-deficient strain was much greater than that induced by rough B. suis strain VTRS1 (Table 5) and can likely be attributed to induction of specific antibody responses to O-side chain. This is consistent with published literature suggesting that the specific humoral and cellular responses to O-side chain are important in producing good protection (4, 5, 10). The inability of the CtpA-deficient strain to protect against challenge with B. melitensis strain 16 M, i.e., cross-species protection, has been noted previously with other Brucella vaccine strains (43). Currently, brucellosis in animal species is diagnosed by detecting the serum antibodies to O-side chain (32). As a vaccine candidate, a major drawback associated with the CtpA-deficient strain is that its smooth phenotype may lead to the production of O-side chain antibodies that may confound serodiagnosis. Alternatively, if a diagnosis assay could be developed to detect the serum antibodies to CtpA, the CtpA-deficient strain would have potential as a brucellosis vaccine candidate.

In summary, the protein encoded by the B. suis ctpA gene is involved in protecting cells from osmotic pressure and determining growth rate, colony size, cell morphology, and intracellular survival during acute as well as chronic phases of infection. The CtpA-deficient B. suis strain induces significant protection in BALB/c mice against challenge with virulent brucellae.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hiroshi Hara for providing the Prc-deficient E. coli strains, Betty Mitchell for help in determining mouse splenic CFU, Virginia Viers and Kathy Lowe for assistance in electron microscopy, Andrea Contreras for help with mouse immunizations, Sherry Poff and Gliss Smith for designing PCR primers, Kay Carlson for technical assistance, and Chris Wakley and the staff of the Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine non-client animal facility for the expert handling of the mice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acha, P., and B. Szyfres. 1980. Zoonoses and communicable diseases common to man and animals, p. 28-45. Pan American Health Organization, Washington, D.C.

- 2.Altschul, S., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. Myers, and D. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson, T. D., N. F. Cheville, and V. P. Meador. 1986. Pathogenesis of placentitis in the goat inoculated with Brucella abortus. II. Ultrastructural studies. Vet. Pathol. 23:227-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Araya, L. N., and A. J. Winter. 1990. Comparative protection of mice against virulent and attenuated strains of Brucella abortus by passive transfer of immune T cells or serum. Infect. Immun. 58:254-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Araya, L. N., P. H. Elzer, G. E. Rowe, F. M. Enright, and A. J. Winter. 1989. Temporal development of protective cell-mediated and humoral immunity in BALB/c mice infected with Brucella abortus. J. Immunol. 143:3330-3337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arenas, G. N., A. S. Staskevich, A. Aballay, and L. S. Mayorga. 2000. Intracellular trafficking of Brucella abortus in J774 macrophages. Infect. Immun. 68:4255-4263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baldwin, C. L., and A. J. Winter. 1994. Macrophages and Brucella. Immunol. Ser. 60:363-380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banai, M., L. G. Adams, M. Frey, R. Pugh, and T. A. Ficht. 2002. The myth of Brucella L-forms and possible involvement of Brucella penicillin binding proteins in pathogenicity. Vet. Microbiol. 90:263-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bendtsen, J. D., H. Nielsen, G. von Heijne, and S. Brunak. 2004. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J. Mol. Biol. 340:783-795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corbel, M. J. 1997. Brucellosis: an overview. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 3:213-221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corbel, M. J., and W. J. Brinley Morgan. 1984. Genus Brucella Meyer and Shaw 1920, 173AL, p. 377-390. In N. R. Krieg and J. G. Holt (ed.), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, vol. 1. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, Md. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curtis, N. A. C., D. Orr, G. W. Ross, and M. G. Boulton. 1979. Affinities of penicillins and cephalosporins for the penicillin-binding proteins of Escherichia coli K-12 and their antibacterial activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 16:533-539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dalbey, R. E., and G. Von Heijne. 1992. Signal peptidases in prokaryotes and eukaryotes—a new protease family. Trends Biochem. Sci. 17:474-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Den Blaauwen, T., M. E. Aarsman, N. O. Vischer, and N. Nanninga. 2003. Penicillin-binding protein PBP2 of Escherichia coli localizes preferentially in lateral wall and at mid-cell in comparison with the old cell pole. Mol. Microbiol. 47:539-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Pedro, M. A., J. C. Quintela, J.-V. Höltje, and H. Schwarz. 1997. Murein segregation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 179:2823-2834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Pedro, M. A., W. D. Donachie, J. V. Holtje, and H. Schwarz. 2001. Constitutive septal murein synthesis in Escherichia coli with impaired activity of the morphogenetic proteins RodA and penicillin-binding protein 2. J. Bacteriol. 183:4115-4126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fraipont, C., M. Adam, M. Nguyen-Disteche, W. Keck, J. Van Beeumen, J. A. Ayala, B. Granier, H. Hara, and J. M. Ghuysen. 1994. Engineering and overexpression of periplasmic forms of the penicillin-binding protein 3 of Escherichia coli. Biochem. J. 298:189-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hara, H., Y. Nishimura, J. Kato, H. Suzuki, H. Nagasawa, A. Suzuki, and Y. Hirota. 1989. Genetic analyses of processing involving C-terminal cleavage in penicillin-binding protein 3 of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 171:5882-5889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hara, H., Y. Yamamoto, A. Higashitani, H. Suzuki, and Y. Nishimura. 1991. Cloning, mapping, and characterization of the Escherichia coli prc gene, which is involved in C-terminal processing of penicillin-binding protein 3. J. Bacteriol. 173:4799-4813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Höltje, J.-V. 1998. Growth of the stress-bearing and shape-maintaining murein sacculus of Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:181-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inagaki, N., Y. Yamamoto, H. Mori, and K. Satoh. 1996. Carboxyl-terminal processing protease for the D1 precursor protein: cloning and sequencing of the spinach cDNA. Plant Mol. Biol. 30:39-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kato, J.-I., H. Suzuki, and Y. Hirota. 1985. Dispensability of either penicillin-binding protein-1a or 1-b involved in the essential process for cell elongation in Escherichia coli. Mol. Genet. 200:272-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keiler, K. C., and R. T. Sauer. 1998. Tsp protease, p. 460-461. In A. J. Barrett, N. D. Rawlings, and J. F. Woessner (ed.), Handbook of proteolytic enzymes. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom.

- 24.Kohler, S., S. Michaux-Charachon, F. Porte, M. Ramuz, and J. P. Liautard. 2003. What is the nature of the replicative niche of a stealthy bug named Brucella? Trends Microbiol. 11:215-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kovach, M. E., R. W. Phillips, P. H. Elzer, R. M. Roop, Jr., and K. M. Peterson. 1994. pBBR1MCS: a broad-host range cloning vector. BioTechniques 16:800-802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McPherson, D. C., and D. L. Popham. 2003. Peptidoglycan synthesis in the absence of class A penicillin-binding proteins in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 185:1423-1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McQuiston, J. R., G. G. Schurig, N. Sriranganathan, and S. M. Boyle. 1995. Transformation of Brucella species with suicide and broad host-range plasmids. Methods Mol. Biol. 47:143-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milner, J. S., D. Dymock, R. M. Cooper, and I. S. Roberts. Penicillin-binding proteins from Erwinia amylovora: mutants lacking PBP2 are avirulent. J. Bacteriol. 175:6082-6088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Nanninga, N. 1998. Morphogenesis of Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:110-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naroeni, A., N. Jouy, S. Ouahrani-Bettache, J. P. Liautard, and F. Porte. 2001. Brucella suis impaired specific recognition of phagosomes by lysosomes due to phagosomal membrane modifications. Infect. Immun. 69:486-493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Academy Press. 1977. Brucellosis research: an evaluation, p. 61-77. In Report of the subcommittee on Brucellosis research. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C.

- 33.Oelmüller, R., R. G. Herrmann, and H. B. Pakrasi. 1996. Molecular studies of CtpA, the carboxyl-terminal processing protease for the D1 protein of the photosystem II reaction center in higher plants. J. Biol. Chem. 271:21848-21856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paetzel, M., and R. E. Dalbey. 1997. Catalytic hydroxyl/amine dyads within serine proteases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 22:28-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pakrasi, H. B. 1998. C-terminal processing protease of photosystem II, p. 462-463. In A. J. Barrett, N. D. Rawlings, and J. F. Woessner (ed.), Handbook of proteolytic enzymes. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom.

- 36.Pizarro-Cerdá, J., S. Méresse, R. G. Parton, G. van der Goot, A. Sola-Landa, I. Lopez-Goñi, E. Moreno, and J. P. Gorvel. 1998. Brucella abortus transits through the autophagic pathway and replicates in the endoplasmic reticulum of nonprofessional phagocytes. Infect. Immun. 66:5711-5724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Popham, D. L., and K. D. Young. 2003. Role of penicillin-binding proteins in bacterial cell morphogenesis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6:594-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Popham, D. L., and P. Setlow. 1995. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and mutagenesis of the Bacillus subtilis ponA operon, which codes for penicillin-binding protein (PBP) 1 and a PBP-related factor. J. Bacteriol. 177:326-335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Popham, D. L., and P. Setlow. 1996. Phenotypes of Bacillus subtilis mutants lacking multiple class A high-molecular-weight penicillin-binding proteins. J. Bacteriol. 178:2079-2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ried, J. L., and A. Colmer. 1987. An npt-sacB-sacR cartridge for constructing directed, unmarked mutations in gram-negative bacteria by marker exchange-eviction mutagenesis. Gene 57:239-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 42.Satoh, K. 1998. C-terminal processing peptidase of chloroplasts, p. 463-464. In A. J. Barrett, N. D. Rawlings, and J. F. Woessner (ed.), Handbook of proteolytic enzymes. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom.

- 43.Schurig, G. G., N. Sriranganathan, and M. J. Corbel. 2002. Brucellosis vaccines: past, present and future. Vet. Microbiol. 90:479-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schurig, G. G., R. M. Roop, T. Bagchi, S. M. Boyle, D. Buhrman, and N. Sriranganathan. 1991. Biological properties of RB51: a stable rough strain of Brucella abortus. Vet. Microbiol. 28:171-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seitz, L. C., and Y. V. Brun. 1998. Genetic analysis of mecillinam-resistant mutants of Caulobacter crescentus deficient in stalk biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 180:5235-5239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Silber, K. R., K. C. Keiler, and R. T. Sauer. 1992. Tsp: a tail-specific protease that selectively degrades proteins with nonpolar C termini. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:295-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spratt, B. G. 1975. Distinct penicillin binding proteins involved in the division, elongation, and shape of Escherichia coli K12. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 72:2999-3003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spratt, B. G. 1977. Properties of the penicillin-binding proteins of Escherichia coli K12. Eur. J. Biochem. 72:341-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Statistical Analysis Systems Institute, Inc. 1985. SAS user's guide. SA Institute, Cary, N.C.

- 49a.Vemulapalli, R., A. J. Duncan, S. M. Boyle, N. Sriranganathan, T. E. Toth, and G. G. Schurig. 1998. Cloning and sequencing of yajC and secD homologs of Brucella abortus and demonstration of immune responses to YajC in mice vaccinated with B. abortus RB51. Infect. Immun. 66:5684-5691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Waxman, D. J., and J. L. Strominger. 1983. Penicillin-binding proteins and the mechanism of action of beta-lactam antibiotics. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 52:825-869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Winter, A. J., G. G. Schurig, S. M. Boyle, N. Sriranganathan, J. S. Bevins, F. M. Enright, P. H. Elzer, and J. D. Kope. 1996. Protection of BALB/c mice against homologous and heterologous species of Brucella by rough strain vaccines derived from Brucella melitensis and Brucella suis biovar 4. Am. J. Vet. Res. 57:677-683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Woldringh, C., P. Huls, E. Pas, G. J. Brakenhoff, and N. Nanninga. 1987. Topography of peptidoglycan synthesis during elongation and polar cap formation in a cell division mutant of Escherichia coli MC4100. J. Gen. Microbiol. 133:575-586. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Young, K. D. 2001. Approaching the physiological functions of penicillin-binding proteins in Escherichia coli. Biochimie 83:99-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yousif, S. Y., J. K. Broome-Smith, and B. G. Spratt. 1985. Lysis of Escherichia coli by beta-lactam antibiotics: deletion analysis of the role of penicillin-binding proteins 1A and 1B. J. Gen. Microbiol. 131:2839-2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]