Abstract

agr is a global regulatory system in the staphylococci, operating by a classical two-component signaling module and controlling the expression of most of the genes encoding extracellular virulence factors. As it is autoinduced by a peptide, encoded within the locus, that is the ligand for the signal receptor, it is a sensor of population density or a quorum sensor and is the only known quorum-sensing system in the genus. agr is conserved throughout the staphylococci but has diverged along lines that appear to parallel speciation and subspeciation within the genus. This divergence has given rise to a novel type of interstrain and interspecies cross-inhibition that represents a fundamental aspect of the organism's biology and may be a predominant feature of the evolutionary forces that have driven it. We present evidence, using a newly developed, luciferase-based agr typing scheme, that the evolutionary divergence of the agr system was an early event in the evolution of the staphylococci and long preceded the development of the nucleotide polymorphisms presently used for genotyping. These polymorphisms developed, for the most part, within different agr groups; mobile genetic elements appear also to have diffused recently and, with a few notable exceptions, have come to reside largely indiscriminately within the several agr groups.

The agr operon encodes a global regulatory system in the staphylococci, central to the biology of the organism (reviewed by Novick) (36). It controls a large set of genes, including most of those encoding extracellular virulence factors and many others encoding cytoplasmic proteins with catabolic and other functions. agr is highly conserved throughout the staphylococci but has diverged in a way that closely parallels speciation and subspeciation within the genus. This divergence has given rise to a novel type of interstrain and interspecies cross-inhibition that may represent the selective forces that have driven its evolution.

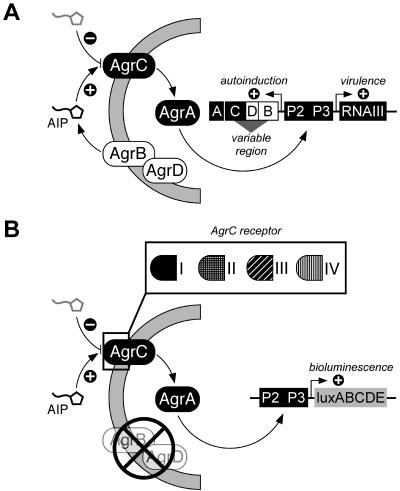

agr operates by a classical two-component signaling module (Fig. 1A). It is autoinduced by a peptide, encoded within the locus, that is the ligand for the histidine kinase component of the signaling module. agr is therefore a sensor of population density or a quorum sensor. The agr variants represent specificity groups that determine the response to cognate or heterologous autoinducing peptides (AIPs). Although an AIP always activates its cognate agr locus, it competitively cross-inhibits agr activation in most heterologous combinations. This cross-inhibition results in a novel type of bacterial interference in which the expression of accessory genes, but not growth, is blocked. This interference has potential therapeutic implications that are presently under investigation. In Staphylococcus aureus there are four known agr specificity groups, characterized by major sequence variations in a central region of the locus that encodes the AIP, the enzyme that processes it, and the receptor domain of the histidine kinase (7, 19, 21). The sequences flanking this central variable region are highly conserved, as are certain motifs within the variable region. This means that agr must have diverged from a common ancestor through transitional intermediates; therefore, it seems highly significant that with the possible exception of the rare agr-IVs, transitional genotypes are not seen.

FIG. 1.

The staphylococcal agr operon. A) The agr locus is composed of two divergent transcriptional units driven by the P2 and P3 promoters. Sequence diversity in the variable region, comprised of the last one-third of agrB, agrD, and the first half of agrC, has generated the four specificity groups in S. aureus. AgrB is a transmembrane protein involved in the processing and secretion of AgrD to form the mature AIP, which is the ligand for AgrC. AgrC and AgrA form a two-component signaling team, which activates transcription from the P2 and P3 promoters, resulting in autoinduction and expression of RNAIII, an mRNA with global regulatory properties. Inhibition of the RNAIII transcription occurs via competitive binding of a noncognate AIP, which binds to the sensor domain of the AgrC receptor. B) Reporter strains with specificity for one of the four AIPs produced by S. aureus. The reporter strains are uncoupled for AIP production and sensation. Each strain is inactivated for agrBD and does not produce autoinducer. Exogenous AIP triggers the signaling cascade through the group-specific AgrCA two-component signaling module to activate the luxABCD reporter from the P3 promoter (55). Intergroup exchange of the receptor domain of AgrC (residues 1 to 205) has been shown to determine AIP specificity (56), and replacement of this region with other AgrC-class homologues could generate reporter sets with different autoinducer specificities.

It is probable that the transition occurred via mutations that broadened specificity, eventually giving rise to fully developed but novel specificities. We presume that the transitional forms would generally have been counterselective and would not have persisted. This reasoning probably applies to the other staphylococcal species, though there are presently very few sequence data to confirm it. Although mutational variants occur within the agr locus in S. aureus (40, 47) and also in S. epidermidis (54), some of which are functionally defective, these always belong clearly to an existing specificity group (unpublished data). The rarity or absence of transitional forms supports the hypothesis that the fully differentiated locus is strongly selected and suggests that agr has a central role in the biology of the organism.

As the only known regulatory system in staphylococci that shows biologically significant variations in specificity, agr diversity may be driving evolution by fostering genetic isolation; in other words, it may well be that the agr groups represent incipient speciation. Thus, an understanding of the function and biological impact of the agr groupings is clearly key to understanding the biology of the organism. Given this striking diversification, a key question is that of whether agr groupings relate to the biotype of the organism beyond the inhibition phenomenon. That is, are the agr groups simply the result of random drift, or has the differentiation been driven by selective forces acting on other features of the organism? As it happens, agr grouping seems to correlate with certain particular pathotypes. Two striking examples occur with agr group III strains. These are nearly the only cause of menstrual toxic shock syndrome (21, 41), harboring a TSST-1-encoding pathogenicity island, SaPI2 (29). Group III strains have been prominently responsible for the recently described fulminant necrotizing pneumonia caused by Panton-Valentin leucocidin (13). These strains also carry the type IV SCCmec element responsible for the recently recognized community-acquired S. aureus methicillin resistance (CA-MRSA). The strains responsible for these two conditions represent two different clonal lineages—that is, they have evolved relatively recently and have neither undergone significant evolutionary divergence nor participated in major genetic exchange with strains of other groups. The significance of this clonality is discussed below. Other less stringent correlations include the association of exfoliatin production with agr-IV strains and the propensity of agr-Is and agr-IIs to give rise to intermediate vancomycin resistance (18, 44).

Given the evolutionary paradigm that appears to underlie this diversity, it is our view that agr type represents a fundamental aspect of staphylococcal biology. Accordingly, we report here the development of a convenient typing scheme, its validation, and its application to several sets of strains, among which are strains previously characterized by other genotyping methods. In addition to describing and validating our agr typing scheme, we address the question of how agr groupings are related to overall genotype as revealed by current genotyping methods. Our data suggest that agr diversification established independent strain groups within which developed the nucleotide polymorphisms that are the basis for genotyping.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. RN6734, RN6607 (also known as 502A), RN3984 (also known as Harrisburg), and RN4850 are our standard strains of agr groups I, II, III, and IV, respectively (19, 21). RN7206, a tetM::agr derivative of RN6734, was the host strain for the agr group-specific tester plasmids described below. Cultures of staphylococci were routinely grown at 37°C in CY broth with 0.5% glucose and on GL or sheep blood agar as described previously (35) and other gram-positive cultures were grown in Trypticase soy broth. Cell growth was monitored with a Klett-Summerson colorimeter (Long Island City) and a green (540-nm) filter. Agar media were supplemented with tetracycline, chloramphenicol, or erythromycin (each at 10 μg/ml) for S. aureus or with ampicillin (100 μg/ml) for Escherichia coli strain DH5α for plasmid maintenance.

TABLE 1.

Relevant strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| RN4220 | S. aureus UV-induced restriction-deficient mutant | 26 |

| RN6734 | S. aureus NCTC 8325-4, φ13 lysogen, agr-l prototype | 21 |

| RN7206 | S. aureus agr::tetM derivative of RN6734 | 38 |

| RN6911 | S. aureus agr::tetM derivative of RN6390 | 21 |

| RN9130 | S. aureus RN6607 (502A), Tcr plasmid cured, agr-II prototype | 21 |

| RN9120 | S. aureus agr::tetM derivative of RN9130 | 30 |

| RN8465 | S. aureus agr-III prototype | 21 |

| RN4850 | S. aureus agr-IV prototype | 19 |

| RN9688 | RN7206 with pRN7130 and pJW7141 | This study |

| RN9689 | RN7206 with pRN7129 and pJW7141 | This study |

| RN9690 | RN7206 with pRN7131 and pJW7141 | This study |

| RN9691 | RN7206 with pRN7128 and pJW7141 | This study |

| RN8556 | RN6911 with pRN6911 and pI524 | 21 |

| RN8793 | RN6911 with pRN6955 and pI524 | 21 |

| RN8797 | RN6911 with pRN6959 and pI524 | 21 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMK4-lux | pMK4 luxABCDE Cmr | 12 |

| pJW7141 | agrp3-lux | 55 |

| pRN7128 | agrp2-agrCA-IV agrp3-blaZ Emr | 56 |

| pRN7129 | agrp2-agrCA-II agrp3-blaZ Emr | 56 |

| pRN7130 | agrp2-agrCA-I agrp3-blaZ Emr | 56 |

| pRN7131 | agrp2-agrCA-III agrp3-blaZ Emr | 56 |

| pRN6911 | blaZp-agrBD-I Cmr | 21 |

| pRN6955 | blaZp-agrBD-II Cmr | 21 |

| pRN6959 | blaZp-agrBD-III Cmr | 21 |

| pI524 | blalR blaZ Pcr Cdr | 37 |

Hemolytic phenotypes.

S. aureus strains commonly produce some combination of four major hemolysins, α (hla), β (hlb), γ (hlg), and δ (hld), all of whose genes are positively regulated by agr and one of which, δ-hemolysin, is encoded by agr-RNAIII. Thus, hemolytic pattern, especially the production of δ-hemolysin, is generally regarded as indicative of agr function. Hemolytic activities of the strains were determined by cross-streaking with RN4220, which produces only β-hemolysin. This test can usually determine which of the three main staphylococcal hemolysins active on sheep blood agar are present. The fourth, γ-hemolysin, is inhibited by agar and is not routinely scored (6).

Construction of agrp3-luciferase fusion.

A PCR product containing the 211-bp intergenic region of the agr locus was obtained using primers JSW16 (ACGCGAATTCACTGTCATTATACG) and JSW17 (ACGCGGATCCATCTCTGTGATCTAG) and cloned to the EcoRI/BamHI sites of pMK4-luxABCDE (12) (kindly provided by Xenogen, Inc.) oriented so that the lux operon is under agrp3 control (55). The clone pJW7141 was constructed in DH5α, electroporated (46) into the restriction-negative S. aureus strain RN4220 (26), and then transferred to other strains by phage-mediated transduction using φ11.

Phenotypic agr typing.

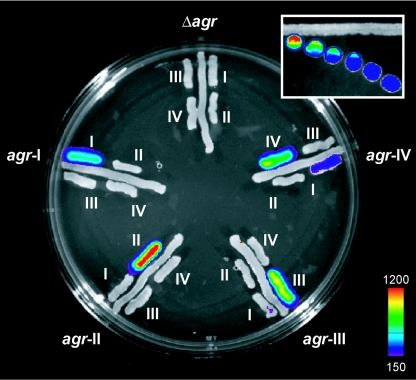

Tester strains were constructed by transferring the agrp3-luciferase fusion plasmid pJW7141 (55) to agr-null strains containing each of the four agr group-specific tester plasmids, pRN7129, pRN7130, pRN7131, and pRN7132, with agrA and agrC under control of the agrp2 promoter. Since the agr promoter region of the four sequenced agr groups is invariant, only a single agrp3-lux fusion is required. With these four strains agrp3 is activated only when the AIP specific for the plasmid-carried agrAC module is present (31, 32). In the absence of the cognate AIP, there is a very low level of luciferase, corresponding to the basal activity of the agrp3 promoter (22). The effects of gene dosage on AgrCA activation in this system have not been investigated, but at its present copy number (∼10 to 20 per cell), there is no detectable effect on the accuracy of the assay. A schematic of the design features comprising the assay is shown in Fig. 1B. The test is set up by streaking the four reporter strains (RN9688 [for agr-I], RN9689 [for agr-II], RN9690 [for agr-III], and RN9691[for agr-IV]) parallel with the unknown strain on a standard agar plate. The AIP secreted by the unknown strain into the surrounding medium activates whichever of the reporter strains corresponds to its specificity, and luciferase activity is recorded with a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (see below). A plate showing agr group-specific activation of the reporter strains by standard strains representing each of the four S. aureus agr specificity groups is shown in Fig. 2. Note that in three of the four cases, only one of the reporters is activated. The agr-IV strain, however, weakly activates the agr-I reporter as well as the agr-IV reporter. This cross-reaction has been observed previously and is a reflection of the single amino acid difference between AIPs-I and IV (32). Predictably, strains carrying a deletion of the agr locus fail to activate any of the biosensor strains. Group-specific activity was restored in agr::tetM derivative 6911 by introduction of the cognate agrBD module from agr-I, -II, and -III (21) and confirmed that AgrBD-directed production of AIP is responsible for the activation specificity of the reporter strains (data not shown). Several coagulase-negative staphylococci and other gram-positive organisms from our stock collection also failed to elicit any specific bioluminescent activation from any of the four S. aureus agr reporter strains (data not shown). Importantly, several coagulase-negative staphylococci have a functional agr locus (7, 38, 39, 53), and their inability to activate any of the reporter strains also illustrates the specificity of the assay for S. aureus autoinducers. It is important to note that secretion on solid media will produce an AIP diffusion gradient. This was detected by the reporter strains when they were inoculated at graded distances from the AIP-producing strain (Fig. 2 inset).

FIG. 2.

Bioluminescent S. aureus agr typing assay. Strains representing each of the four standard agr groups, RN6734 (agr-I), RN6607 (agr-II), RN8465 (agr-III), and RN4850 (agr-IV), plus an agr-null control are streaked radially. The agr-specific reporter strains (RN9688, RN9689, RN9690, and RN9691), each carrying a group-specific AgrCA two-component signaling pair plus an agrp3-lux fusion, are streaked alongside the standard strains, each of which activates one of the reporters, according to the specificity of its AIP. Reporters are identified by roman numerals designating their specificity group. Note that there is weak cross-reactivation of the group I reporter by the standard group IV strain and no activation by the agr-null. Bioluminescence was detected with a Hamamatsu CCD camera and is presented as a pseudocolor image, with the color bar indicating the signal intensity in counts. An AIP diffusion gradient is created on solid media (inset). As a representative example, the agr-II specific reporter strain (RN9689) was inoculated at graded distances from AIP-II producer RN6607 (agr-II). The bioluminescent signal generated from agrp3-lux decreases as the distance between the reporter strain and the AIP producing strain increases.

Genotypic agr typing.

agr type was determined genotypically by sequencing agrD. Bacteria were lysed by mechanical disruption in a FastPrep dismembrator (QBiogene), and cellular debris was pelleted by centrifugation. The supernatant (1 μl) was added directly to the PCR. The agrD coding region was PCR amplified using Taq polymerase (Roche) and primers agrB-1 (TATGCTCCTGCAGCAACTAA) and PANagr-R (GAATAATACCAATACTGCGAC) (14), which are complementary to invariant sequences of the S. aureus agr locus (GenBank accession numbers U85097 [agr-I], AF001782 [agr-II], AF001783 [agr-III], and AF288215 [agr-IV]). Amplified products were purified by Qiaquick PCR purification (QIAGEN) and sequenced by dye terminator DNA sequencing chemistry (Skirball DNA sequencing core facility). The agr-Ia subtype was identified by an agr-Ia-specific primer (agr-Ia F; ATTGCTATTGGTTTGATAA) generated from the agr-Ia locus (GenBank accession no. AF210055) (40) and a previously published agrC primer (agr-C2; CTTGCGCATTTCGTTGTTGA) (14). Strains that were agr-Ia produced a 1.1-kb product, while agr-I, -II, -III, and -IV strains produced no product.

Measurement of bioluminescence.

Bioluminescence was evaluated qualitatively in bacteria growing on agar by a C2400 Hamamatsu CCD camera modified for luciferase detection by Xenogen, Inc., and kindly provided by that company. The CCD array collected the emitted photons during a 60-s exposure in a light-free Hamamatsu specimen chamber. Bioluminescent images were processed using Living Image software (Xenogen) and displayed using a pseudocolor scale (blue representing the least intense and red representing the most intense signal) overlaid onto a gray-scale photographic image. For the bioluminescent images in the figures, the upper and lower limits of the overall bioluminescent signal are displayed in counts.

RESULTS

Testing and verification of the phenotypic assay.

Development of the luciferase-based agr-typing system is described in Materials and Methods. We tested our typing system on a large set of strains from our stock collection. The results for 23 of these, representing standard laboratory strains widely used in research, are listed in Table 2. Results for the entire set are summarized in Table 3. For 20 of these, 5 from each group, we checked the agr types by sequencing agrD. The agrD sequences matched the agr types determined phenotypically in all 20 cases.

TABLE 2.

The agr types of commonly used laboratory strainse

| Strain | Novick lab designation | Description | agr type | Hemolysinc

|

Pigmentd | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | β | δ | |||||

| NCTC8325a | RN1 | Propagating strain for phage 47 | I | + | + | + | W |

| COLa | RN9467 | Homogeneous MRSA prototype | I | − | − | − | G |

| LS1 | RN9655 | Mouse-adapted strain | I | − | + | + | G |

| Newbold | RN8432 | Prototypical bovine strain | I | + | + | + | G |

| Reynolds | RN10146 | Capsule serotype 5 prototype | I | − | + | + | W |

| Becker | RN10147 | Capsule serotype 8 prototype | I | + | + | + | W |

| Wood 46 | RN6497 | Overproducer of α-hemolysin | I | + | − | + | W |

| Newman | RN10149 | Overproducer of coagulase | I | − | − | + | G |

| S6C | RN8482 | Overproducer of lipase | I | + | − | + | W |

| TC82 | RN6499 | Overproducer of δ-hemolysin | I | − | − | + | W |

| TC128 | RN6498 | Overproducer of β-hemolysin | I | − | + | + | G |

| ATCC27733 | RN6596 | V8 serine protease prototype | I | + | − | + | W |

| Smith M | RN6430 | M-type capsule | II | − | − | − | W |

| N315a | RN9533 | “Pre-MRSA” prototype | II | − | − | − | W |

| Mu50a | RN9534 | VISA prototype | II | − | − | − | G |

| Cowan 1 | RN10157 | Hyperproducer of protein A | IIIb | − | − | − | W |

| Smith D | RN6432 | Diffuse colonies in serum-soft agar | III | − | − | + | G |

| Smith C | RN6431 | Compact colonies in serum-soft agar | III | − | − | + | G |

| MN8 | RN8081 | Toxic shock prototype | III | − | − | + | G |

| MW2a | RN9473 | C-MRSA prototype | III | + | + | + | W |

| MRSA252a | RN9700 | MRSA prototype | III | − | − | + | W |

| MSSA476a | RN9701 | Methicillin-sensitive prototype | III | − | − | + | G |

| SSST | RN4850 | Exfoliatin prototype | IV | − | − | + | G |

Genome sequence available.

Typed by PCR/DNA sequencing.

Hemolysin production as described in Materials and Methods. +, produced; −, not produced.

G, gold; W, white.

MRSA, methicillin-resistant S. aureus; pre-MRSA, putative MRSA precursor; VISA, vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus.

TABLE 3.

Phenotypic characterization of S. aureus strains

| agr typea | No. of isolates | No. of isolates producing the indicated hemolysina

|

No. of isolates with the indicated pigmentc

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | β | δ | None | G | W | ||

| I | 287 | 137 | 66 | 252 | 25 | 214 | 73 |

| II | 102 | 62 | 22 | 88 | 10 | 87 | 15 |

| III | 125 | 51 | 11 | 109 | 16 | 96 | 29 |

| IV | 18 | 10 | 0 | 17 | 1 | 8 | 10 |

| Nontypable | 45 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 41 | 26 | 19 |

| Total | 577 | 263 | 101 | 469 | 93 | 467 | 152 |

Determined using the phenotypic typing assay as described in materials and methods.

Hemolysin production as described in Materials and Methods.

G, gold; W, white.

Hemolytic activity and agr functionality.

The elaboration of hemolysins, particularly α- and δ-hemolysins, is generally used as a rapid screening test for agr functionality. Our results suggest that this may be misleading. Of the strains summarized in Table 3, 93 were nonhemolytic but over 50% of these were phenotypically typeable. To test for agr functionality independently, we introduced pJW7141, carrying the agrp3-lux reporter fusion, into 20 of the typeable but nonhemolytic strains. The agrp3-lux reporter is not agr-group specific—i.e., it will be activated in any S. aureus strain with a functional agr-P2 operon. Thus, we can measure directly the kinetics of agr induction throughout growth in any strain into which we are able to introduce this plasmid (55). Of these, 15 were able to activate luciferase production to various levels, some activating production to a level as high as that activated by a wild-type agr+ control, whereas a typical agr-null was unable to activate the reporter. The details of this experiment will be reported elsewhere; for present purposes, it supports the conclusion that hemolytic activity is not necessarily a reliable indicator of agr function. As part of this study, we sequenced the agrD region for about half of the nontypeable strains and found that each could be assigned unequivocally to one of the four existing agr groups (data not shown). Many of these, however, have inactivating mutations within the agr locus that can be complemented by a wild-type allele introduced on a plasmid. These results will also be reported elsewhere.

Correlation of agr types with sequence-based genotypes.

To test the hypothesis that the agr radiation is a primordial determinant of staphylococcal differentiation, we agr typed several sets of strains previously characterized by various other genotyping methods. Results are shown in Table 4 for a set of 18 representative clinical isolates that have been classified into six pathotypes or lineages (referred to as SAL types) on the basis of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) analysis of SmaI digests of chromosomal DNA by Booth et al. (2). These six pathotypes are 100% correlated with agr type. Thus, all of three SAL1 and three SAL6 strains are agr-III, all of three SAL2 and three SAL4 strains are agr-II, and all of three SAL3 and three SAL5 strains are agr-I; the SAL5s, however, represent a conserved nucleotide variant of agr-I designated agr-Ia, whose sequence has previously been identified (40). The agr-Ia subtype has not evolved into a separate specificity class and represents a stable genetic variant of agr-I, which produces and responds to AIP-I. It is interesting that the correlation of agr-III with toxic shock syndrome holds for SAL1 strains, all three of which produce TSST-1, but not for SAL6, none of which produces the toxin. Other associations with virulence determinants in this set of isolates are as follows: SAL2 and SAL4 strains, both agr-II, harbor cna at much lower frequencies than other SAL types, and SAL2 was the only lineage which carried fnbB (2), suggesting that carriage of certain variable genetic units may be linked to agr type.

TABLE 4.

S. aureus lineage types are related by agr type

| Strain | Novick lab designation | Clinical descriptiona | SAL typea | agr type | Hemolysinc

|

Pigmentd | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | β | δ | ||||||

| SA5 | RN9095 | Eye | 3 | I | − | − | + | G |

| SA404 | RN9102 | Bone | 3 | I | − | − | + | G |

| SA118 | RN9103 | Catheter | 3 | I | − | − | + | G |

| SA320 | RN9107 | Outbreak | 5 | Ia | − | − | + | G |

| SA21 | RN9108 | Eye | 5 | Ia | − | − | + | G |

| SA196 | RN9109 | Phillips | 5 | Iab | − | − | − | G |

| SA28 | RN9097 | Catheter | 2 | II | − | − | + | G |

| SA127 | RN9098 | Blood | 2 | II | + | − | + | G |

| SA288 | RN9100 | Blood | 2 | II | − | − | + | G |

| SA276 | RN9104 | Respiratory | 4 | II | − | − | + | G |

| SA23 | RN9105 | Eye | 4 | II | + | − | + | W |

| SA67 | RN9106 | Wound | 4 | IIb | − | − | − | G |

| SA26 | RN9096 | Eye | 1 | III | − | − | + | G |

| SA280 | RN9099 | Blood | 1 | III | − | − | + | G |

| SA393 | RN9101 | Bone | 1 | IIIb | − | − | − | G |

| SA117 | RN9110 | Catheter | 6 | III | − | − | + | G |

| SA286 | RN9111 | Blood | 6 | III | − | − | + | G |

| SA4 | RN9112 | Eye | 6 | III | − | − | + | G |

Clinical description and phylogenetic lineages as described in Booth et al. (2). SAL, S. aureus lineage.

Typed by PCR/DNA sequencing.

Hemolysin production as described in Materials and Methods. +, produced; −, not produced.

G, gold; W, white.

A second set of strains is that characterized by Fitzgerald et al. on the basis of a whole-genome DNA microarray, which identified macroscopic “regions of difference” (RDs) between these strains and an index strain, COL (11). They were also characterized by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (MLEE) (49), pulse field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), and protein A (spa) and coagulase (coa) typing (25). The results of agr typing of these strains, along with the other typing results are presented in an online supplement (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). In Table 5, the results are organized according to agr groups, showing which genotypes are found in each agr group. Note that with one exception, no single genotype is found in more than one agr group, suggesting that the agr radiation preceded the divergence represented by each of the other genotypes. Interestingly, some RDs were found associated with only a single agr type (e.g., RD7, RD8, and RD12 with agr-I), some were associated with some but not all agr types (e.g., RD4, RD6, and RD10), and still others were ubiquitous (e.g., RD1, RD13, RD14, and RD16). Carrying a highly variable exotoxin locus, RD13 was found widespread in these isolates but differed in gene content (10) and these variations also correlated with agr type.

TABLE 5.

agr type versus various genotypese

| A

|

B

|

C

|

D

|

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| agr type | MLEE strainsa

|

MRSA and MSSA strainsb

|

agr type vs CC typec

|

MRSA strainsd

|

||||||||||||||||

| Total no. of isolates | MLEE type | No. of isolates | coa type | No. of isolates | spa type | No. of isolates | Total no. of isolates | MLST type | No. of isolates | SCCmec type | No. of isolates | Total no. of isolates | CC type | No. of isolates | Total no. of isolates | MLST type | No. of isolates | SCCmec type | No. of isolates | |

| I or Ia | 14 | 32 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 33 | ST8 | 2 | I | 3 | 101 | CC1 | 3 | 174 | ST8 | 34 | I | 40 |

| 39 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | S22 | 2 | IA | 5 | CC5 | 3 | S22 | 43 | II | 13 | |||||

| 53 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 1 | ST45 | 3 | III | 6 | CC8 | 16 | ST45 | 14 | III | 24 | |||||

| 66 | 1 | 10 | 3 | 7 | 1 | ST239 | 14 | IIIA | 2 | CC22 | 25 | ST239 | 21 | IV | 76 | |||||

| 70 | 1 | 19 | 1 | 73 | 1 | ST241 | 1 | IIIB | 1 | CC25 | 23 | ST241 | 2 | |||||||

| 89 | 2 | 20 | 1 | 92 | 1 | ST247 | 6 | IV | 4 | CC30 | 2 | ST247 | 39 | |||||||

| 93 | 3 | 29 | 1 | 283 | 1 | ST250 | 5 | CC45 | 28 | ST250 | 21 | |||||||||

| 134 | 1 | 30 | 2 | 291 | 1 | CC51 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 146 | 1 | 292 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 147 | 1 | 294 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| ND | 1 | 295 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 299 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| II | 4 | 91 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 11 | ST5 | 10 | I | 1 | 65 | CC5 | 18 | 56 | ST5 | 57 | I | 25 |

| 195 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 45 | 1 | ST228 | 1 | II | 2 | CC12 | 11 | ST228 | 13 | II | 25 | |||||

| 21 | 1 | 47 | 1 | IV | 2 | CC15 | 31 | III | 1 | |||||||||||

| CC30 | 2 | IV | 5 | |||||||||||||||||

| CC51 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||

| III | 15 | 93 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 16 | 1 | 5 | ST1 | 1 | II | 1 | 129 | CC1 | 13 | 47 | ST30 | 3 | II | 44 |

| 234 | 14 | 22 | 8 | 33 | 6 | ST30 | 2 | III | 1 | CC30 | 90 | ST36 | 44 | IV | 3 | |||||

| 23 | 1 | 43 | 1 | ST36 | 1 | IV | 2 | CC39 | 24 | |||||||||||

| 24 | 1 | 281 | 1 | ST80 | 1 | IVA | 1 | CC45 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 25 | 1 | 296 | 1 | CC51 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 28 | 1 | 297 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 298 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 300 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 301 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 302 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| IV | 3 | 189 | 2 | 27 | 1 | 79 | 1 | 6 | CC45 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 191 | 1 | 31 | 2 | 89 | 1 | CC51 | 5 | |||||||||||||

| 293 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

Entries in boldface in this table represent rare genotypes that occur in two or more agr groups. Data determined according to Fitzgerald et al. (11). ND, not determined.

Data determined according to Gomes et al. (15). MSSA, methicillin-sensitive S. aureus.

Data determined according to Peacock et al. (41).

agr type predicted on the basis of MLST type. Data determined according to Enright et al. (9).

A, B, C, and D refer to separate sets of data, some from this work and some adapted from the work of others.

A third compilation involves 49 MRSA strains that have been characterized by multilocus sequence typing (MLST) and other methods by Gomes et al. (15), In this series, as shown in Table 5, again no single genotype is found in more than one agr group, lending further support to the precedence of the agr radiation. There is in Table 5 an adaptation of data published by Peacock et al. (41), involving a rather larger number of MLST-typed strains which were agr typed by sequencing and grouped according to a set of clonal complexes, which correlate with MLSTs but are slightly broader. In this much larger series, the same general rule holds, although there are a few clonal complexes that appear in more than one agr group. Possible explanations for this are discussed below. The situation with the SCCmec elements, which occur in at least four variant forms and several subsidiary variants, as seen in Table 5, is strikingly different—with a few exceptions, SCCmec elements of each type occur in each agr group, except that group IV, which is by far the rarest, has not yet been found to carry SCCmec. In this case, the sample is probably too small for the exceptions to be significant (note that in Table 5 we have predicted agr types from MLST types based on the strong associations illustrated in the other tables). At the same time, certain SCCmec elements seem to have a strong predilection for particular S. aureus genotypes defined by MLST (9, 43); we suggest that these apparent predilections actually represent the recent spread of clones that happen to have acquired an SCCmec element by horizontal gene transfer (HGT). The nature of the reservoir for the SCCmec elements which have migrated to new ST lineages is not always clear. The results, however, are quite consistent with the hypothesis that SCCmec was acquired by S. aureus much more recently than the occurrence of the agr radiation.

agr groups and variable/MGEs.

As noted above, there is anecdotal evidence that certain mobile genetic elements (MGEs) may have agr-group-specific host preferences. For example, phages and plasmids carrying eta/b are most common in agr-IV strains; SaPI2, the TSST-1 prototype, is preferentially carried by agr-III strains, integrated at a site within the trp locus (4, 5) (Note that SaPIn1 and SaPIm1 [27] have been incorrectly renamed “SaPI2” by Baba et al. [1], and this incorrect designation has been perpetuated by Lindsay and Holden [28].) Many of these strains also have a (defective?) penicillinase plasmid integrated in the same region; among the sequenced strains, only MSSA476, which does not carry SaPI2 but is also agr-III, has an integrated penicillinase plasmid, though it is not in the trp region. Although the penicillinase plasmids commonly carry one or more transposons that can mediate integration of the entire plasmid (48), the occurrence of integrated penicillinase plasmids in other lineages has not been documented. A total of 22 of the naturally occurring strains from our strain collection that were agr typed in this study were known to carry autonomous penicillinase plasmids. Of these, 15 are agr-III and 7 are agr-I. Although group-II was not represented among these, agr-II strains N315 and Mu50 also harbor penicillinase plasmids. Given that agr-I outnumbers agr-III in our series by more than twofold (287:125), it may be that penicillinase plasmids, integrated or not, have a preference for agr-III strains. Outside of these implications, the only definitive data on mobile elements are found within the sequenced strains, and there seems to be very little, if any, agr group specificity among the elements carried by these strains, including transposons, plasmids, prophages, and other chromosomal islands, such as the SCCmec island, as noted above and in Table 4. Nevertheless, there may be significant agr group specificity in the combinations of MGEs observed which may reflect apparent agr group-specific biotypical features.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have developed and applied a novel luciferase-based agr typing scheme and have used it to address three questions. (i) How does the underlying differentiation into four agr specificity groups in S. aureus fit into the large number of genotypic classes differentiated by nucleotide polymorphisms? (ii) Is there a correlation between agr grouping and carriage of accessory genetic elements? And (iii) is there a correlation between agr type and common phenotypic traits, such as hemolytic patterns and pigmentation?

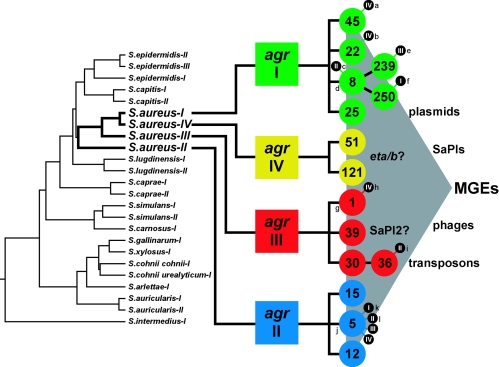

We have looked at several sets of strains genotyped by some or all of five different methods—PFGE, MLEE, MLST, and spa and coa typing. Each of these methods reveals genotypes that are so strongly correlated with agr types that the former can be used to predict the latter unequivocally. For example, from this analysis we were able to predict and confirm that the agr-Ia subtype, a distinct nucleotide variant of agr-I which still uses AIP-I, is most likely represented by strains of the ST45 lineage. It will be argued that individual lineages represent clones—which of course they do, but “clone” in this context simply means that the strains have been disseminated from a common ancestor without having undergone significant evolutionary divergence, so that the underlying genotypic commonality is readily discerned. It must be emphasized, however, that for any one of these lineages, not all of the genotyping results are homogeneous, indicating that there has clearly been divergence, but not enough to obscure the underlying commonality. For example, there is considerable diversity in the number of spa and coa repeats in the variable region used for typing—but nucleotide substitutions in spa types within common ST lineages (http://www.ridom.de/spaserver/) (17) are often highly conserved (data not shown). Thus, in the few random and limited sets of strains that we have analyzed, agr-I, agr-Ia, agr-II, agr-III, and agr-IV are each represented by one or a few predominant MLST patterns, as shown in the tables and summarized in Fig. 3. The key finding here, however, is that with exceedingly rare exceptions, no MLST pattern occurs in more than one agr group, and the same appears to be true for other polymorphism-based typing methods, such as MLEE, spa and coa typing, and PFGE. This means that the differentiation into agr groups was primary and was followed by diversification within the groups. Although most of the available data correlating agr types with the various genotyping methods are much too limited to be statistically significant, we are confident, nevertheless, that the above-described conclusion will be readily confirmed by additional data.

FIG. 3.

The agr radiation. Evolutionary divergence of the agr locus has generated four agr specificity groups in S. aureus and one or more specificity groups among the non-aureus staphylococci. At left is a phylogenetic tree constructed from multiple sequence alignments of the AgrC variable receptor domain by CLUSTAL V. A tree constructed from 16S rRNA sequences has strikingly similar topology (data not shown) (7). The S. aureus agr lineages have given rise to the major MLST types observed today (http://www.mlst.net). There is evidence that putative mobile genetic elements (MGEs) are transferred horizontally among all agr types, but significant agr-specific predilections indicate that this lateral gene flow is constrained by some mechanism that may or may not be related to agr function. Lowercase letters in the diagram indicate examples of clinically significant MRSA isolates (labeled with their corresponding SCCmec type) and isolates whose genomes have been sequenced (*) (a, Berlin; b, EMRSA-15; c, Irish-1; d, 8325-4*; e, EMRSA-1; f, COL*; g, MSSA476*; h, MW2; i, MRSA252*; j, Mu50*; k, EMRSA-3; l, N315*).

We suggest, on the basis of the occurrence of a serine-containing AIP in all strains of S. intermedius (23) but in no others, that the agr diversification probably occurred at least 55 million years ago. The serine, substituted for cysteine in the AgrD S. intermedius propeptide, is processed by AgrB, resulting in a cyclic lactone peptide analogous to the cyclic thiolactone peptides characteristic of all other staphylococci examined to date, and represents a predominant evolutionary feature separating S. intermedius from the other staphylococci (Fig. 3). Unlike S. aureus, S. intermedius is typically isolated from carnivores, especially dogs, and rarely from humans and primates. The reasoning here is the Kloos hypothesis (24) that staphylococcal species coevolved with their host animals. Thus, S. intermedius would have diverged from S. aureus along with the divergence of the line leading to primates from that leading to carnivores—approximately 55 million years ago.

The evolutionary process leading to agr diversification requires the coordination of mutations affecting the 3 determinants of agr group specificity—the AIP, the receptor (AgrC), and the processing enzyme (AgrB). A similar coordination is seen in the evolution of abalone species, where matching egg and sperm proteins must evolve in concert to preserve fertility (51). It is likely that such concerted evolution in the agr locus would involve intermediary mutational stages with broadened specificity, since a mutation losing activity would be an evolutionary dead end (56). The identification of individuals with broadened specificity would support this idea and in the case of agr-IV may represent an intermediate with broadened specificity: its AIP differs by only a single amino acid from that of group I and shows weak cross-reactivity with AIP from agr-I. Further, the remainder of its agr locus is much more closely related to that of agr-I than to those of either group II or III. Additionally, agr-IV strains are isolated much more rarely than the strains of the other three groups. This suggests that agr-IV may be a relatively recent offshoot of agr-I; however, agr-IV strains differ quite radically in certain genotypic characteristics from agr-I strains—for example, agr is activated very much earlier in growth in agr-IV strains than in agr-I and they carry at least two MGEs, determining exfoliatins, that are extremely rare in agr-I strains (19).

Several studies have examined the presence of both mobile and stable genetic determinants of the staphylococcal virulon (2, 33, 34, 41, 50). From this analysis, along with the seven publicly available genomes and recent DNA microarray comparisons (3, 8, 45, 52), it is apparent that most elements are not exclusively associated with one agr type—though there may be considerable variations in the frequency of carriage of these elements. This is clearly evident in a set of 198 isolates previously characterized by Jarraud et al. using amplified fragment length polymorphism, where it was shown that these elements are found in multiple agr groups at different frequencies—and that some combinations of these elements are frequently found together or apart (20). As suggested by Peacock et al. in a similar study, at least some of these combinations may be related to agr type and the underlying core genetic structure rather than representing “hitchhiking” of linked elements (41). With respect to mobile elements, there seem to be four well-documented clinical situations where agr group may be highly relevant: the association of agr-III with menstrual toxic shock syndrome (21) and with Panton-Valentin leucocidin-induced necrotizing pneumonitis (13), the association of agr-IV with exfoliatin production (19), and a predilection for reduced vancomycin sensitivity in agr-I and -II (18, 44). We stress, however, that in none of these cases is the basis for the apparent specificity known, and there is insufficient data to show whether these apparent preferences are real. Experiments are in progress to evaluate the possible significance and determine the possible bases for these apparent preferences.

With respect to common phenotypic traits, such as hemolytic patterns, pigmentation, etc., the type of data that have been collected simply cannot be used to evaluate genotypes: this is because the agr radiation is primarily a genotypic phenomenon that has given rise to families of subsidiary genotypic polymorphisms, some of which are correlated with particular traits. In order to determine whether hemolytic patterns, pigment, etc., are related to genotypes, such as agr groups, one would have to subject the underlying genes to sequence analysis similar to that done for spa and coa. This is because these traits are very much components of the core staphylococcal genome; while they could, like the genes used for MLST, MLEE, and coa and spa typing, diversify within agr groups, this diversification would be revealed by sequence analysis rather than by superficial phenotypic scoring. Needless to say, therefore, these traits, as scored by simple phenotypic tests, have not diversified according to agr groupings. One interesting question relates to β-hemolysin, whose gene contains the attachment site for a particular prophage that often carries two or three virulence genes. Here again, lysogeny for these phages does not appear to be agr group specific, although it is much more common among human than among domestic animal strains of S. aureus, as seen in this and earlier studies (16).

An overall conclusion from these studies is that the agr radiation occurred very long ago and that it may have been driven more by spontaneous mutations broadening specificity rather than by biological forces selecting for particular biotypical specificities. Its further evolution would then have been driven in a direction that would restore function but would allow specificity to diversify (56). We have constructed a hypothetical evolutionary tree based on the availability of a considerable number of complete or partial agr sequences from various staphylococci, as diagrammed in Fig. 3. This scheme has been made possible by the powerful MLST, which accurately tracks the development of largely nonselective genetic polymorphisms. The MLST types have been added to this tree (for the S. aureus groups), as also shown. Superimposed on this scheme is the putative invasion by SCCmec and other MGEs, whose present distribution is the resultant of clonal diversification plus further horizontal transfer—of which the latter has not been measured in the natural environment but can be inferred from strain identities.

The problem remains, if this scheme is correct, of how to account for the few cases where single MLST types are found in more than one agr group. Although it appears that the most important source of genetic variation within the staphylococcal chromosome is point mutations, other sources of variation such as interstrain recombination and intrastrain rearrangements have been readily demonstrated (42). And it is our hypothesis that these could easily account for the exceptional strains; it may well be worthwhile to investigate a few of these. We note that a megabase (representing a full one-third of the S. aureus chromosome) separates the agr locus from spa, coa, SCCmec, and the MLST loci, indicating that intrastrain recombination could affect many or all of these loci, leaving the agr locus intact. The MLST paradigm suggests that there is not frequent horizontal gene transfer involving those particular genes—and, by implication, that there is not frequent horizontal gene transfer (HGT) involving stable chromosomal regions. Nevertheless, HGT has been postulated to account for some 20% of the natural variation among strains (28). This would suggest that horizontal transfer mostly involves MGEs and labile components of the genome, such as chromosomal islands. As noted above, an important remaining question is whether there are agr group-specific genotypes that impact HGT.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to several laboratories and investigators over the years that have graciously contributed many of the isolates used in this study. We are also grateful to Kevin Francis and Pamela Contag at Xenogen, Inc., for kindly providing the bioluminescent imaging system used in this study, which included the C2400 Hamamatsu CCD camera and Living Image Software package.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant RO142736 to R.P.N. and NRSA postdoctoral fellowship F32AI055242 to J.S.W.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baba, T., F. Takeuchi, M. Kuroda, H. Yuzawa, K. Aoki, A. Oguchi, Y. Nagai, N. Iwama, K. Asano, T. Naimi, H. Kuroda, L. Cui, K. Yamamoto, and K. Hiramatsu. 2002. Genome and virulence determinants of high virulence community-acquired MRSA. Lancet 359:1819-1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Booth, M. C., L. M. Pence, P. Mahasreshti, M. C. Callegan, and M. S. Gilmore. 2001. Clonal associations among Staphylococcus aureus isolates from various sites of infection. Infect. Immun. 69:345-352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cassat, J. E., P. M. Dunman, F. McAleese, E. Murphy, S. J. Projan, and M. S. Smeltzer. 2005. Comparative genomics of Staphylococcus aureus musculoskeletal isolates. J. Bacteriol. 187:576-592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chu, M. C., B. N. Kreiswirth, P. A. Pattee, R. P. Novick, M. E. Melish, and J. F. James. 1988. Association of toxic shock toxin-1 determinant with a heterologous insertion at multiple loci in the Staphylococcus aureus chromosome. Infect. Immun. 56:2702-2708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chu, M. C., M. E. Melish, and J. F. James. 1985. Tryprophan auxotypy associated with Staphylococcus aureus that produce toxic shock syndrome toxin. J. Infect. Dis. 151:1157-1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooney, J., M. Mulvey, J. P. Arbuthnott, and T. J. Foster. 1988. Molecular cloning and genetic analysis of the determinant for gamma-lysin, a two-component toxin of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Gen. Microbiol. 134:2179-2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dufour, P., S. Jarraud, F. Vandenesch, T. Greenland, R. P. Novick, M. Bes, J. Etienne, and G. Lina. 2002. High genetic variability of the agr locus in Staphylococcus species. J. Bacteriol. 184:1180-1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunman, P. M., W. Mounts, F. McAleese, F. Immermann, D. Macapagal, E. Marsilio, L. McDougal, F. C. Tenover, P. A. Bradford, P. J. Petersen, S. J. Projan, and E. Murphy. 2004. Uses of Staphylococcus aureus GeneChips in genotyping and genetic composition analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:4275-4283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Enright, M. C., D. A. Robinson, G. Randle, E. J. Feil, H. Grundmann, and B. G. Spratt. 2002. The evolutionary history of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:7687-7692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fitzgerald, J. R., S. D. Reid, E. Ruotsalainen, T. J. Tripp, M. Liu, R. Cole, P. Kuusela, P. M. Schlievert, A. Jarvinen, and J. M. Musser. 2003. Genome diversification in Staphylococcus aureus: molecular evolution of a highly variable chromosomal region encoding the staphylococcal exotoxin-like family of proteins. Infect. Immun. 71:2827-2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fitzgerald, J. R., D. E. Sturdevant, S. M. Mackie, S. R. Gill, and J. M. Musser. 2001. Evolutionary genomics of Staphylococcus aureus: insights into the origin of methicillin-resistant strains and the toxic shock syndrome epidemic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:8821-8826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Francis, K. P., D. Joh, C. Bellinger-Kawahara, M. J. Hawkinson, T. F. Purchio, and P. R. Contag. 2000. Monitoring bioluminescent Staphylococcus aureus infections in living mice using a novel luxABCDE construct. Infect. Immun. 68:3594-3600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gillet, Y., B. Issartel, P. Vanhems, J. C. Fournet, G. Lina, M. Bes, F. Vandenesch, Y. Piemont, N. Brousse, D. Floret, and J. Etienne. 2002. Association between Staphylococcus aureus strains carrying gene for Panton-Valentine leukocidin and highly lethal necrotising pneumonia in young immunocompetent patients. Lancet 359:753-759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilot, P., G. Lina, T. Cochard, and B. Poutrel. 2002. Analysis of the genetic variability of genes encoding the RNA III-activating components Agr and TRAP in a population of Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from cows with mastitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:4060-4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomes, A. R., S. Vinga, M. Zavolan, and H. de Lencastre. 2005. Analysis of the genetic variability of virulence-related loci in epidemic clones of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:366-379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hajek, V., and E. Marsalek. 1976. Staphylococci outside the hospital. Staphylococcus aureus in sheep. Zentbl. Bakteriol. 161:455-461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harmsen, D., H. Claus, W. Witte, J. Rothgänger, D. Turnwald, and U. Vogel. 2003. Typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a university hospital setting by using novel software for spa repeat determination and database management. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5442-5448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howe, R. A., A. Monk, M. Wootton, T. R. Walsh, and M. C. Enright. 2004. Vancomycin susceptibility within methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus lineages. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10:855-857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jarraud, S., G. J. Lyon, A. M. Figueiredo, L. Gerard, F. Vandenesch, J. Etienne, T. W. Muir, and R. P. Novick. 2000. Exfoliatin-producing strains define a fourth agr specificity group in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 182:6517-6522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jarraud, S., C. Mougel, J. Thioulouse, G. Lina, H. Meugnier, F. Forey, X. Nesme, J. Etienne, and F. Vandenesch. 2002. Relationships between Staphylococcus aureus genetic background, virulence factors, agr groups (alleles), and human disease. Infect. Immun. 70:631-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ji, G., R. Beavis, and R. P. Novick. 1997. Bacterial interference caused by autoinducing peptide variants. Science 276:2027-2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ji, G., R. C. Beavis, and R. P. Novick. 1995. Cell density control of staphylococcal virulence mediated by an octapeptide pheromone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:12055-12059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ji, G., W. Pei, L. Zhang, R. Qiu, J. Lin, and R. P. Novick. 2005. Staphylococcus intermedius produces a functional agr autoinducing peptide containing a cyclic lactone. J. Bacteriol. 187:3139-3150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kloos, W. E. 1980. Natural populations of the genus Staphylococcus. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 34:559-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koreen, L., S. V. Ramaswamy, E. A. Graviss, S. Naidich, J. M. Musser, and B. N. Kreiswirth. 2004. spa typing method for discriminating among Staphylococcus aureus isolates: implications for use of a single marker to detect genetic micro- and macrovariation. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:792-799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kreiswirth, B. N., S. Lofdahl, M. J. Betley, M. O'Reilly, P. M. Schlievert, M. S. Bergdoll, and R. P. Novick. 1983. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature 305:709-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuroda, M., T. Ohta, I. Uchiyama, T. Baba, H. Yuzawa, I. Kobayashi, L. Cui, A. Oguchi, K. Aoki, Y. Nagai, J. Lian, T. Ito, M. Kanamori, H. Matsumaru, A. Maruyama, H. Murakami, A. Hosoyama, Y. Mizutani-Ui, N. K. Takahashi, T. Sawano, R. Inoue, C. Kaito, K. Sekimizu, H. Hirakawa, S. Kuhara, S. Goto, J. Yabuzaki, M. Kanehisa, A. Yamashita, K. Oshima, K. Furuya, C. Yoshino, T. Shiba, M. Hattori, N. Ogasawara, H. Hayashi, and K. Hiramatsu. 2001. Whole genome sequencing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 357:1225-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindsay, J. A., and M. T. Holden. 2004. Staphylococcus aureus: superbug, super genome? Trends Microbiol. 12:378-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindsay, J. A., A. Ruzin, H. F. Ross, N. Kurepina, and R. P. Novick. 1998. The gene for toxic shock toxin is carried by a family of mobile pathogenicity islands in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 29:527-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lyon, G. J., P. Mayville, T. W. Muir, and R. P. Novick. 2000. Rational design of a global inhibitor of the virulence response in Staphylococcus aureus, based in part on localization of the site of inhibition to the receptor-histidine kinase, AgrC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:13330-13335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lyon, G. J., J. S. Wright, A. Christopoulos, R. P. Novick, and T. W. Muir. 2002. Reversible and specific extracellular antagonism of receptor histidine-kinase signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 277:6247-6253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lyon, G. J., J. S. Wright, T. W. Muir, and R. P. Novick. 2002. Key determinants of receptor activation in the agr autoinducing peptides of Staphylococcus aureus. Biochemistry 41:10095-10104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore, P. C., and J. A. Lindsay. 2001. Genetic variation among hospital isolates of methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus: evidence for horizontal transfer of virulence genes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2760-2767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moore, P. C., and J. A. Lindsay. 2002. Molecular characterisation of the dominant UK methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains, EMRSA-15 and EMRSA-16. J. Med. Microbiol. 51:516-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Novick, R. 1991. Genetic systems in sataphylococci. Methods Enzymol. 204:587-683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Novick, R. P. 2003. Autoinduction and signal transduction in the regulation of staphylococcal virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 48:1429-1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Novick, R. P. 1967. Penicillinase plasmids of Staphylococcus aureus. Fed. Proc. 26:29-38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Novick, R. P., H. F. Ross, A. M. S. Figueiredo, G. Abramochkin, and T. Muir. 2000. Activation and inhibition of the staphylococcal agr system. Science 287:391a. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Otto, M., R. Sussmuth, C. Vuong, G. Jung, and F. Gotz. 1999. Inhibition of virulence factor expression in Staphylococcus aureus by the Staphylococcus epidermidis agr pheromone and derivatives. FEBS Lett. 450:257-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Papakyriacou, H., D. Vaz, A. Simor, M. Louie, and M. J. McGavin. 2000. Molecular analysis of the accessory gene regulator (agr) locus and balance of virulence factor expression in epidemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. Dis. 181:990-1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peacock, S. J., C. E. Moore, A. Justice, M. Kantzanou, L. Story, K. Mackie, G. O'Neill, and N. P. Day. 2002. Virulent combinations of adhesin and toxin genes in natural populations of Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 70:4987-4996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robinson, D. A., and M. C. Enright. 2004. Evolution of Staphylococcus aureus by large chromosomal replacements. J. Bacteriol. 186:1060-1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robinson, D. A., and M. C. Enright. 2003. Evolutionary models of the emergence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3926-3934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sakoulas, G., G. M. Eliopoulos, R. C. J. Moellering, C. Wennersten, L. Venkataraman, R. P. Novick, and H. S. Gold. 2002. Accessory gene regulator (agr) locus in geographically diverse Staphylococcus aureus isolates with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1492-1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saunders, N. A., A. Underwood, A. M. Kearns, and G. Hallas. 2004. A virulence-associated gene microarray: a tool for investigation of the evolution and pathogenic potential of Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiology 150:3763-3771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schenk, S., and R. A. Laddaga. 1992. Improved method for electroporation of Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 94:133-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schwan, W. R., M. H. Langhorne, H. D. Ritchie, and C. K. Stover. 2003. Loss of hemolysin expression in Staphylococcus aureus agr mutants correlates with selective survival during mixed infections in murine abscesses and wounds. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 38:23-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schwesinger, M. D., and R. P. Novick. 1975. Prophage-dependent plasmid integration in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 123:724-738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Selander, R. K., D. A. Caugant, H. Ochman, J. M. Musser, M. N. Gilmour, and T. S. Whittam. 1986. Methods of multilocus enzyme electrophoresis for bacterial population genetics and systematics. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 51:873-884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smeltzer, M. S., A. F. Gillaspy, F. L. Pratt, and M. D. Thames. 1997. Comparative evaluation of use of cna, fnbA, fnbB, and hlb for genomic fingerprinting in the epidemiological typing of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2444-2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Swanson, W. J., and V. D. Vacquier. 1998. Concerted evolution in an egg receptor for a rapidly evolving abalone sperm protein. Science 281:710-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trad, S., J. Allignet, L. Frangeul, M. Davi, M. Vergassola, E. Couve, A. Morvan, A. Kechrid, C. Buchrieser, P. Glaser, and N. El Solh. 2004. DNA macroarray for identification and typing of Staphylococcus aureus isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:2054-2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vuong, C., F. Gotz, and M. Otto. 2000. Construction and characterization of an agr deletion mutant of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Infect. Immun. 68:1048-1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vuong, C., S. Kocianova, Y. Yao, A. B. Carmody, and M. Otto. 2004. Increased colonization of indwelling medical devices by quorum-sensing mutants of Staphylococcus epidermidis in vivo. J. Infect. Dis. 190:1498-1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wright, J. S., III, R. Jin, and R. P. Novick. 2005. Transient interference with staphylococcal quorum sensing blocks abscess formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:1691-1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wright, J. S., III, G. J. Lyon, E. A. George, T. W. Muir, and R. P. Novick. 2004. Hydrophobic interactions drive ligand-receptor recognition for activation and inhibition of staphylococcal quorum sensing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:16168-16173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.