Abstract

In a search for regulatory genes of the type III secretion system (TTSS) in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, transposon (Tn5) insertional mutants of the prtR gene were found defective in the TTSS. PrtR is an inhibitor of prtN, which encodes a transcriptional activator for pyocin synthesis genes. In P. aeruginosa, pyocin synthesis is activated when PrtR is degraded during the SOS response. Treatment of a wild-type P. aeruginosa strain with mitomycin C, a DNA-damaging agent, resulted in the inhibition of TTSS activation. A prtR/prtN double mutant had the same TTSS defect as the prtR mutant, and complementation by a prtR gene but not by a prtN gene restored the TTSS function. Also, overexpression of the prtN gene in wild-type PAK had no effect on the TTSS; thus, PrtN is not involved in the repression of the TTSS. To identify the PrtR-regulated TTSS repressor, another round of Tn mutagenesis was carried out in the background of a prtR/prtN double mutant. Insertion in a small gene, designated ptrB, restored the normal TTSS activity. Expression of ptrB is specifically repressed by PrtR, and mitomycin C-mediated suppression of the TTSS is also abolished in a ptrB mutant strain. Therefore, PtrB is a new TTSS repressor that coordinates TTSS repression and pyocin synthesis under the stress of DNA damage.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa causes a wide range of infections, from minor skin infections to serious and sometimes life-threatening complications. P. aeruginosa is also a causative agent of systemic infections in immunocompromised patients, such as those receiving chemotherapy, elderly patients, and burn victims (38, 41). The ability of P. aeruginosa to cause such a variety of human infections revolves around three factors. First is its nutritional versatility, which makes this bacterium extremely adaptive, contributing to its ability to colonize in a variety of human tissues. Second is its resistance to a wide spectrum of antibiotics, which makes it a difficult task to eradicate the microorganism from infected individuals, often leading to chronic infections. And the third is that this microorganism harbors an arsenal of virulence factors which have a cumulative effect on the host. These virulence genes are tightly regulated by a regulatory hierarchy and exquisitely sensitive to the host environmental signals (21, 29).

The type III secretion system (TTSS) is an important virulence factor of P. aeruginosa: it inhibits host defense system by inducing apoptosis in macrophages, polymorphonuclear phagocytes, and epithelial cells (8, 22, 24). The TTSS encodes on the order of 30 proteins that assemble into a complex designed to deliver effector molecules directly into the cytoplasmic compartment of the host cells. The type III secretion system of P. aeruginosa responds to various environmental signals, such as low calcium and direct contact with host cells (21, 46). Upon activation, the type III secretion apparatus translocates effector molecules into the cytoplasm of the host cell, resulting in cell rounding, lifting, and cell death by necrosis or apoptosis (16, 22, 24, 45, 46). Among the four known effector molecules, ExoS and ExoT share structural similarity, both with an ADP-ribosyltransferase activity and a GTPase-activating protein activity, while ExoU and ExoY have lipase and adenylate cyclase activities, respectively (2, 13, 31, 42, 45). The ADP-ribosyltransferase activity of ExoS has been shown to cause programmed cell death in various types of tissue culture cells (22, 24).

In P. aeruginosa, the expression of type III-related genes is coordinately regulated by a transcriptional activator, ExsA (20). ExsA is a DNA binding protein that recognizes a consensus sequence located upstream of the transcriptional start site to stimulate the expression of type III secretion genes, including the exsA gene itself (20). Meanwhile, the type III genes are also negatively regulated by ExsD, which is proposed to interact with ExsA (34). ExsD was further shown to be negatively regulated by ExsC; thus, ExsA function depends on the presence of ExsC (11). A number of additional genes have also been shown to affect the expression of type III genes, although the regulatory mechanisms are not known. Those include a membrane-associated adenylcyclase (CyaB) and a cyclic AMP binding CRP homolog called Vfr (49), the RhlI/RhlR quorum-sensing system (19), the stationary-phase sigma factor RpoS (19), a tRNA pseudouridine synthase (TruA) (1), a hybrid sensor kinase/response regulator (RtsM/RetS) (14, 27), and a three-component regulatory system (SadARS) (25).

Recently, we have demonstrated that a gene highly inducible during infection of the burn mouse model, designated ptrA, encodes a small protein which inhibits TTSS through direct binding to ExsA and thus functions as an anti-ExsA factor (17). Expression of this gene is specifically inducible by high copper signal in vitro through a CopR/S two-component regulatory system, suggesting an important in vivo signal during infection of burn mouse skin tissue (17, 36). Also, we have shown that mutation in a mucA gene not only activates alginate production but also represses the expression of the TTSS (50). Further analysis indicated the presence of an AlgU-regulated repressor mediating the TTSS repression (50). Since alginate overproduction is a defense response against environmental insults, such as high salinity and oxidative stress (6, 15, 32), the expression of TTSS genes seems coordinately repressed upon the activation of stress resistance genes.

In the presence of DNA damaging agents, yet another environmental stress, the bacterial SOS response system, is turned on, mediating the expression of the DNA repair system as well as the production of bacteriocins called pyocins (35). More than 90% of P. aeruginosa strains are able to produce several types of pyocins. Three types of pyocins have been identified: R-type, F-type, and S-type (3, 28, 35). Production of the pyocins is tightly regulated by PrtR, a λCI homologue which binds to the promoter region of the prtN gene and inhibits its expression. PrtN is an activator of pyocin synthesis genes. The production of pyocin is induced by DNA-damaging agents, such as UV light and mitomycin C, when the bacterial SOS response is activated. Under these conditions, RecA protein is activated and cleaves PrtR. As a result, PrtN is up regulated and actives the expression of pyocin synthesis genes (33).

In this report, we describe a coordinated repression of the TTSS under the stress of DNA damage. The expression of TTSS genes was found defective in the background of a prtR mutant. Further analysis eliminated the possible involvement of the prtN gene in the TTSS repression. A gene designated ptrB has been identified which is specifically repressed by PrtR and mediates the suppression of the TTSS genes. PtrB has a prokaryotic DskA/TraR C4-type zinc-finger motif but does not directly interact with the master regulator, ExsA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. Bacteria were grown in L-broth (LB) at 37°C. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: for P. aeruginosa, spectinomycin at 200 μg/ml, streptomycin at 200 μg/ml, tetracycline at 100 μg/ml, neomycin at 400 μg/ml, gentamicin at 150 μg/ml, and carbenicillin at 150 μg/ml; for Escherichia coli, ampicillin at 100 μg/ml, spectinomycin at 50 μg/ml, streptomycin at 25 μg/ml, gentamicin at 10 μg/ml, and kanamycin at 50 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| BW20767/pRL27 | RP4-2-Tc::Mu-1 kan::Tn7 integrant leu-63::IS10 recA1 zbf-5 creB510 hsdR17 endA1 thi uidA (ΔMluI)::pir+/pRL27 | 26 |

| DH5α/λpir | φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 recA1 hsdR17 deoR thi-1 supE44 gyrA96 relA1/λpir | 26 |

| P. aeruginosa strains | ||

| PAK | Wild-type P. aeruginosa strain | David Bradley |

| PAK A51 | PAK prtR::Tn5 mutant isolate; Neor | This study |

| PAKΔprtNprtR::Gm | PAK with prtN and prtR disrupted by replacement of Gm cassette; Gmr | This study |

| PAKprtN::Gm | PAK with prtN disrupted by insertion of Gm cassette; Gmr | This study |

| F4 | PAKΔprtNprtR::GmPA0612::Tn5; Gmr Neor | This study |

| PAKΔprtNprtR::Gm | PAKΔprtNprtR::Gm with deletion of PA0612 and PA0613; Gmr | This study |

| ΔPA0612-613 | ||

| PAKΔprtNprtR::Gm | PAKΔprtNprtR::Gm with deletion of PA0612; Gmr | This study |

| ΔPA0612 | ||

| PAKΔprtNprtR::Gm | PAKΔprtNprtR::Gm with deletion of PA0613; Gmr | This study |

| ΔPA0613 | ||

| PAKΔPA0612-613 | PAK with deletion of PA0612 and PA0613 | This study |

| PAKΔPA0612 | PAK with deletion of PA0612 | This study |

| PAKΔPA0613 | PAK with deletion of PA0613 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR2.1-TOPO | Cloning vector for the PCR products | Invitrogen |

| pHW0005 | exoS promoter of PAK fused to promoterless lacZ on pDN19lacZΩ; Spr Smr Tcr | 16 |

| pHW0006 | exoT promoter of PAK fused to promoterless lacZ on pDN19lacZΩ; Spr Smr Tcr | 16 |

| pUCP19 | Shuttle vector between E. coli and P. aeruginosa | 17 |

| pEX18Gm | Gene replacement vector; Gmr, oriT+sacB+ | 18 |

| pEX18Ap | Gene replacement vector; Apr, oriT+sacB+ | 18 |

| pPS856 | Source of Gmr cassette; Apr Gmr | 18 |

| pWW031 | prtN gene of PAK on pUCP19 driven by lac promoter; Apr | This study |

| pWW037 | prtR gene of PAK on pUCP19 driven by lac promoter; Apr | This study |

| pWW033 | prtN disrupted by insertion of Gm cassette on pEX18Ap; Apr Gmr | This study |

| pWW035 | prtN and prtR disrupted by replacement of Gm cassette on pEX18Ap; Apr Gmr | This study |

| pWW048-1 | PA0612 promoter of PAK fused to promoterless lacZ on pDN19lacZΩ; Spr Smr Tcr | This study |

| pWW069 | Deletion of PA0612 and PA0613 on plasmid pEX18Ap; Apr | This study |

| pWW070 | Deletion of PA0612 and PA0613 on plasmid pEX18Gm; Gmr | This study |

| pWW075 | Deletion of PA0612 on plasmid pEX18Gm; Gmr | This study |

| pWW076 | Deletion of PA0613 on plasmid pEX18Gm; Gmr | This study |

| pWW071 | PA0613 open reading frame cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO; Apr | This study |

| pWW072 | PA0612 open reading frame cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO; Apr | This study |

| pBT | Bait vector plasmid encoding full length bacterial phage λcI protein; Chlr | Stratagene |

| pTRG | Target vector plasmid encoding RNAP-alpha subunit protein; Tcr | Stratagene |

| pBT-LGF2 | Interaction control plasmid containing dimerization domain of Gal4 on bait vector; Chlr | Stratagene |

| pTRG-Gal 11p | Interaction control plasmid encoding mutant form of Gal11 on target vector; Tcr | Stratagene |

| pWW077 | PA0612 open reading frame cloned into pTRG; Tcr | This study |

| pWW078 | PA0613 open reading frame cloned into pTRG; Tcr | This study |

| pWW079 | PA0612 open reading frame cloned into pBT; Chlr | This study |

| pWW080 | PA0613 open reading frame cloned into pBT; Chlr | This study |

| pHW0315 | exsA open reading frame cloned into pTRG; Tcr | 17 |

| pWW081 | exsA open reading frame cloned into pBT; Chlr | This study |

For prtR gene complementation, a prtR-containing fragment was amplified from PAK genomic DNA by PCR (Table 2). The PCR product was cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen), resulting in pTopo-prtR. From pTopo-prtR, the prtR gene was isolated as a HincII-HindIII fragment and cloned into SmaI-HindIII sites of pUCP19, resulting in pWW037, where the prtR gene is driven by a lac promoter. For prtN gene overexpression, prtN coding sequence was amplified by PCR (Table 2), initially cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO, and subcloned into HindIII-XbaI sites of pUCP19, where the expression of the prtN gene in the resulting plasmid, pWW031, was driven by the lac promoter on the vector. The promoter region of PA0612 was amplified from PAK chromosomal DNA (Table 2), cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO, and subcloned into EcoRI-BamHI sites of pDN19lacZΩ, resulting in pWW048-1.

TABLE 2.

PCR primers used in this study

| Gene | Amplicon size (bp) | Sequences of primers |

|---|---|---|

| PtrR | 1,355 | PrtR1: 5′-CCAGTTCGTTGGCGTGATCGGCAAGGTC-3′ |

| PrtR2: 5′-CCCTCCTGCGGCTACACGTCGTTGAGGG-3′ | ||

| PrtN | 1,376 | PrtN1: 5′-CCATGCAGCCATCCATCGCCCCTAGCAC-3′ |

| PrtN2: 5′-CCGTCGCAGCGCATGTCCATCGAATTCA-3′ | ||

| PA0612 (promoter) | 616 | lac1H: 5′-AAGCTTTCGGGCGGGATCTGGGTGCTCT-3′ |

| lacB2: 5′-TGGGATCCCCGCAGTCCTCGCAGTCTTC-3′ | ||

| PA0612-3 | 2,417 | 612-3M1: 5′-AAGCTTATCTGGCGGCTGCGCATGTCCT-3′ |

| 612-3M2: 5′-CAGCATCACCGCCACGCCGCAGACAATC-3′ | ||

| PA0612 | 240 | 612BT1: 5′-GCGGCCGCCACGCCAGGGAGGCTTTCCA-3′ |

| 612BT2: 5′-CTCGAGGTCGGTTCAACGGCGCTCGTGG-3′ | ||

| PA0613 | 417 | 613BT1: 5′-GCGGCCGCGAAAGGAGACACGACCGTGAT-3′ |

| 613BT2: 5′-CTCGAGGGGGGACACGGTATCCGGTCCAG-3′ | ||

| PA0612-3 (RT-PCR) | 649 | 612GS1: 5′-GGATCCCCATGGCTGACCTTGCCGATCAC-3′ |

| 613BT2: 5′-CTCGAGGGGGGACACGGTATCCGGTCCAG-3′ | ||

| ptrB (Q-PCR)a | 101 | Forward: 5′-GATCACGCCAACGAACTGGTC-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-CCGCAGTCCTCGCAGTCTTCC-3′ | ||

| rpsL (Q-PCR) | 120 | Forward: 5′-CAAGCGCATGGTCGACAAGAG-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-ACCTTACGCAGTGCCGAGTTC-3′ |

Q-PCR, quantitative real-time PCR.

Chromosomal gene mutations were generated as described elsewhere (18). A fragment containing the prtN and prtR genes was amplified by PCR using the primers PrtR1 and PrtN2. The PCR product was cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO and subcloned into HindIII-XbaI sites of pEX18Ap, resulting in pEX18Ap-prtNR. For construction of a prtN prtR double mutant, an SphI fragment containing 3′-terminal sequence of prtR and 5′-terminal sequence of prtN was replaced with a gentamicin resistance cassette, resulting in pWW035. For the construction of ΔPA0612-613, ΔPA0612, and ΔPA0613 mutants, a 2.4-kb fragment was amplified from PAK chromosomal DNA with primers 612-3M1 and 612-3M2 (Table 2), followed by cloning into pCR2.1-TOPO. A SacII fragment containing both PA0612 and PA0613 was deleted to generate the ΔPA0612-613 mutant. A 76-bp SacII-PstI fragment within PA0612 was removed to generate the ΔPA0612 mutant, while a 116-bp ClaI-SacII fragment was deleted to generate the ΔPA0613 mutant. The resulting plasmids were transformed into wild-type PAK or PAKΔprtNprtR::Gm and selected for single and double crossover mutants as described previously (18). Construction of a transposon (Tn5) insertion mutant library, plasmid rescue, and sequence analysis were conducted as previously described (26, 50).

Western blotting.

P. aeruginosa strains were cultured overnight in LB at 37°C. Bacterial cells were diluted 100-fold with fresh LB or 30-fold with LB containing 5 mM EGTA and cultured for 3.5 h. Supernatant and pellet were separated by centrifugation and mixed with sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) loading buffer. Equal loading of the protein samples was based on the same number of bacterial cells. The proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane and probed with rabbit polyclonal antibody against ExoS. The signal was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence following the protocol provided by the manufacturer (Amersham Biosciences).

RT-PCR and quantitative real-time PCR.

Overnight cultures of bacterial cells were diluted 100-fold into fresh medium and grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.0. Total RNA was isolated with an RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN). DNA was eliminated by column digestion as described by the manufacturer (QIAGEN). cDNA was synthesized with an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). Taq DNA polymerase from Eppendorf was used in PCRs. The cDNAs synthesized by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) were used as templates in quantitative real-time PCR. The cDNA was mixed with 5pmol of forward and reverse primers (Table 2) and iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). Quantitative real-time PCR was conducted using the ABI Prism 7000 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). The results were analyzed with ABI Prism 7000 SDS software. Transcript for the 30S ribosomal protein (rpsL) was used as an internal standard to compensate for differences in the amount of cDNA. The mRNA levels of ptrB in test strains were expressed relative to that of PAK, which was set at 1.00.

Cytotoxicity assay.

HeLa cells (5 × 104) were seeded into each well of a 24-well plate. The cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 5% fetal calf serum at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 24 h. Overnight bacterial cultures were washed with LB and subcultured to log phase before infection. Bacteria were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline and resuspended in tissue culture medium. HeLa cells were infected with the bacteria at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 20. A cell lifting assay was performed after 4 h of infection. Culture medium in each well was aspirated. Cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline and stained with 0.05% crystal violet for 5 min. The stain solution was discarded, and the plates were washed twice with water. A 250-μl volume of 95% ethanol was then added into each well and incubated at room temperature for 30 min with gentle shaking. The ethanol solution with dissolved crystal violet dye was used to measure absorbance at a wavelength of 590 nm.

Application of BacterioMatch two-hybrid system.

PA0612 and PA0613 open reading frames were amplified from PAK chromosomal DNA with primers 612BT1 plus 612BT2 and 613BT1 plus 613BT2, respectively (Table 2). The PCR products were cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO, and each was subcloned into NotI-XhoI sites of pBT and pTRG, resulting in pWW079 (PA0612 in pBT), pWW077 (PA0612 in pTRG), pWW080 (PA0613 in pBT), and pWW078 (PA0613 in pTRG). The exsA open reading frame was isolated from pHW0315 (exsA in pTRG) as a NotI-SpeI fragment. The SpeI site was blunt ended and ligated into NotI-SmaI sites of pBT, resulting in pWW081 (exsA in pBT). Desired pairs of plasmids were cotransformed into a reporter strain by electroporation, and the protein-protein interaction assays were performed following the protocol supplied by the manufacturer (Stratagene).

Other methods.

β-Galactosidase activity assays were done as described before (50). For twitching motility assays, bacteria were stabbed into a thin-layer LB plate and incubated overnight at 37°C. The plate was directly stained with Coomassie blue at room temperature for 5 min and destained with destain solution.

RESULTS

TTSS is repressed in a prtR mutant.

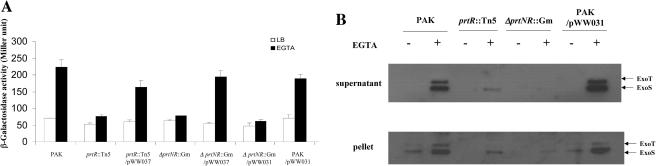

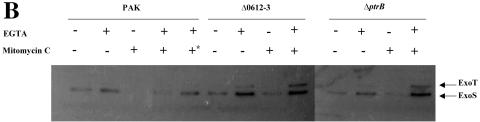

To identify Pseudomonas aeruginosa genes that affect the expression of the TTSS, a Tn5 insertion mutant bank was constructed in strain PAK containing an exoT::lacZ reporter plasmid (pHW0006). On plates containing 5-chloro-4-bromo-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) and EGTA, the intensity of the blue color of each colony indicated the expression level of the exoT gene in that particular Tn insertion mutant. By screening a Tn insertion library consisting of 40,000 independent mutants, mutations in the prtR gene were found to be defective in TTSS activation (Fig. 1). Complementation of the original prtR::Tn mutants with a prtR gene partially restored the TTSS activity (Fig. 2A). PrtR is a repressor of pyocin synthesis, which are bacteriocins synthesized by P. aeruginosa. PrtR binds to the promoter region of the prtN gene and represses its expression. PrtN is also a DNA binding protein which recognizes a highly conserved sequence (P box) present upstream of pyocin synthesis genes and activates their expression (33). Based on this regulatory pathway, either the up-regulated PrtN is responsible for the TTSS repression or a gene under the control of PrtR mediates the TTSS repression. To test these possibilities, a prtR prtN double mutant was generated in the background of wild-type PAK. The resulting mutant, PAKΔprtNprtR::Gm, had the same TTSS defect as the prtR::Tn5 mutant (Fig. 2A and B), and complementation by a prtR gene (pWW037) but not by a prtN gene (pWW031) restored the TTSS inducibility (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, introduction of a prtN-expressing clone in a high-copy-number plasmid (pWW031) in wild-type PAK had no effect on the TTSS activity (Fig. 2A and B). Thus, all of the above results indicated that PrtN is not involved in the TTSS repression. Therefore, it is likely that another gene(s) under the control of PrtR mediates the repression of the TTSS.

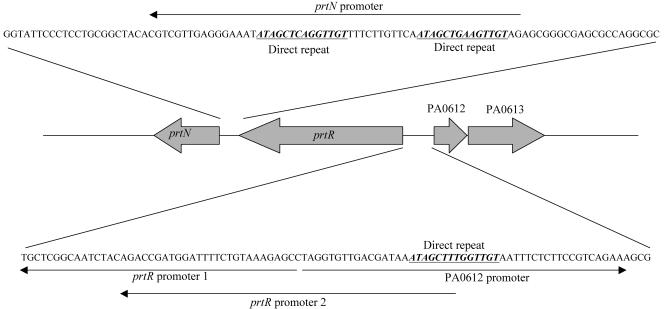

FIG. 1.

Genetic organization and putative promoter regions of prtN, prtR, PA0612, and PA061. Computer-predicted promoters of prtN, prtR, PA0612-613, and PA0614 are indicated with arrows. Two promoters are predicted for the prtR gene and are designated promoters 1 and 2. The potential PrtR binding sequences are underlined. The arrow of each open reading frame represents the transcriptional direction.

FIG. 2.

Expression and secretion of ExoS. (A) Expression of exoS::lacZ in the backgrounds of PAK, prtR::Tn5, prtR::Tn5 containing prtR expression plasmid pWW037, ΔprtNR::Gm, ΔprtNR::Gm containing pWW037 or prtN expression plasmid pWW031, and PAK with pWW031. Bacteria were grown to an OD600 of 1 to 2 in LB with or without EGTA before β-galactosidase assays. (B) Cellular and secreted forms of ExoS in strains PAK, prtR::Tn5, ΔprtNR::Gm, and PAK containing pWW031. Overnight bacterial cultures were diluted to 1% in LB or 3% in LB plus 5 mM EGTA and grown at 37°C for 3.5 h. Supernatants and pellets from equivalent bacterial cell numbers were loaded onto SDS-PAGE gels and immunoblotted with anti-ExoS antibody. Both ExoS and ExoT are indicated by arrows. Anti-ExoS polyclonal antibody also recognizes ExoT due to high homology between them.

Identification of the PrtR-regulated repressor of the TTSS.

Since PrtR functions as a repressor, it might also repress the expression of a hypothetical TTSS repressor. With the prtR mutant, this hypothetical repressor is up regulated and represses the expression of the TTSS. Therefore, upon inactivation of this repressor gene in the prtR mutant background, the TTSS activity should be restored to that of wild type. To identify this hypothetical repressor, the ΔprtNprtR::Gm double mutant containing exoT-lacZ (pHW0006) was subjected to transposon mutagenesis. A plasmid containing a Tn5 transposon (pRL27) was transferred from E. coli donor strain BW20767 into P. aeruginosa by conjugation. Double mutant strain ΔprtNprtR::Gm was chosen as a recipient, since it has an identical phenotype of a TTSS defect as the prtR::Tn mutant. More importantly, constitutive production of pyocin by a prtR mutant seems to have a detrimental effect on the E. coli donor strain, affecting the conjugation frequency.

The Tn insertion mutants were spread on LB agar plates containing 20 μg/ml X-Gal, 2.5 mM EGTA, and proper antibiotics. Blue colonies were looked for in which the TTSS repressor under the control of PrtR should have been knocked out. About 100,000 Tn insertion mutants were screened. Thirty blue colonies were picked and cultured in liquid LB for β-galactosidase assay. Sixteen mutants showed restored TTSS activity compared to the parent strain. Sequence analysis of the Tn insertion sites showed that 14 mutants had Tn insertions at a single locus (PA0612) at nine different positions. PA0612 encodes a hypothetical protein with a consensus prokaryotic DksA/TraR C4-type zinc-finger motif. The dksA gene product suppresses the temperature-sensitive growth and filamentation of a dnaK deletion mutant of Escherichia coli (23), while TraR is involved in plasmid conjugation (12). These proteins contain a C-terminal region thought to fold into a four-cysteine zinc finger (12). Its homologues also exist in other gram-negative bacteria, such as Pseudomonas syringae, Pseudomonas putida, E. coli, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, and Shigella flexneri. However, the functions of these gene homologues have not been studied. The remaining two mutants contained a Tn insertion in the genes PA2265 and PA5021, respectively. PA2265 encodes a putative gluconate dehydrogenase. Promoter analysis (http://www.fruitfly.org/seq_tools/promoter.html)indicates it is in the same operon with an upstream gene, PA2264, as well as a downstream gene, PA2266. PA2264 is an unknown gene, while PA2266 encodes a putative cytochrome c precursor. PA5021 encodes a probable sodium:hydrogen antiporter. Promoter analysis indicated that two downstream genes, PA5022 and PA5023, are in the same operon with PA5021, where PA5022 and PA5023 encode two unknown proteins. We further pursued the regulation and function of PA0612 in this study.

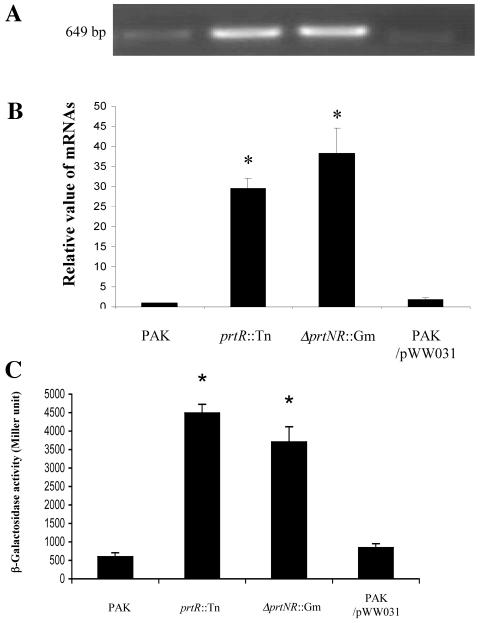

PA0612 and PA0613 form an operon which is under the control of PrtR.

Promoter analysis predicted that PA0612 and PA0613 may form an operon, while the pyocin synthesis gene PA0614 has its own promoter. The downstream gene (PA0613) encodes an unknown protein. On the chromosome of PAO1, PA0612 is located next to the prtR gene in the opposite direction. In the promoter region of PA0612, a 14-base sequence was observed that was also present as a direct repeat in the predicted prtN promoter region, which might be the PrtR recognition site (33) (Fig. 1). Therefore, it is highly likely that the expression of PA0612 is under the control of PrtR and mediates the repression of TTSS. To confirm the prediction that PA0612 and PA0613 are in the same operon, a pair of primers annealing to the 5′ end of PA0612 (612GS1) and 3′ end of PA0613 (613BT2) was designed for RT-PCR analysis (Table 2). A 649-bp PCR product was amplified using total RNA isolated from prtR::Tn or ΔprtNprtR::Gm (Fig. 3A), and the size was the same as that when PAK genomic DNA was used as template (data not shown). However, when total RNA from PAK or PAK/pWW031 (prtN overexpresser) was used as template, a faint PCR product could be seen (Fig. 3A), indicating low abundance of this transcript. These results indicated that PA0612 and PA0613 are in the same operon, which is under the negative control of PrtR. Transcription of PA0612 was investigated further by real-time PCR. Expression of PA0612 mRNA in prtR::Tn and ΔprtNR::Gm was 30- and 38-fold greater than that in PAK, respectively, while overexpression of the prtN gene had little effect on the transcript level of PA0612 (Fig. 3B). To further confirm this, the promoter of PA0612 was fused with a promoterless lacZ gene on plasmid pDN19lacZΩ, and the resulting fusion construct (pWW048-1) was introduced into various strain backgrounds for the β-galactosidase assay. As shown in Fig. 3C, the expression of PA0612 was up regulated in both prtR::Tn and ΔprtNprtR::Gm mutant backgrounds compared to that in PAK or PAK overexpressing prtN (PAK/pWW031), further proving that the expression of PA0612 and PA0613 is repressed by PrtR. The above results also reaffirmed our earlier conclusion that prtN has no effect on the expression of PA0612 and PA0613.

FIG. 3.

Expression of PA0612 is repressed by prtR. (A) RT-PCR of the PA0612-0613 operon. Total RNA was isolated from PAK, prtR::Tn5, ΔprtNR::Gm, and PAK/pWW031. One microgram of RNA from each sample was used to synthesize cDNA, and the cDNA was diluted 100-fold for subsequent PCR amplification. The primers used in the PCR anneal to the 5′ end of PA0612 and the 3′ end of PA0613. (B) Quantitation of ptrB gene expression by real-time PCR. Data are expressed relative to the quantity of ptrB mRNA in PAK. (C) Expression of PA0612::lacZ (pWW048-1) in PAK, prtR::Tn5, ΔprtNR::Gm, and PAK/pWW031. Bacteria were grown in LB for 10 h before β-galactosidase assays. *, P < 0.01, compared to the values in PAK.

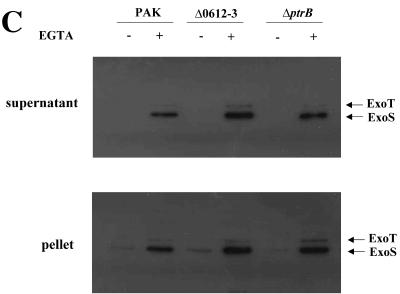

PA0612 is required for repression of the TTSS in the prtR mutant.

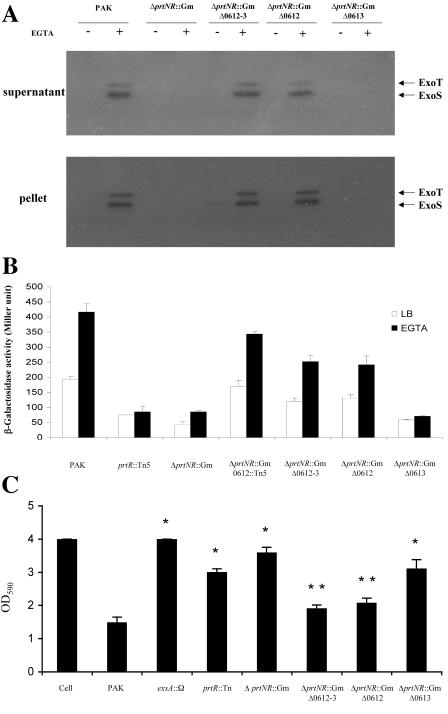

Since PA0612 and PA0613 are in the same operon, insertion of a Tn in PA0612 will have a polar effect on the expression of PA0613. To test which of the two genes is required for the TTSS repression in the prtR mutant, deletion mutants of PA0612 and PA0613 and the PA0612 PA0613 double mutant were generated in the background of the ΔprtNprtR::Gm mutant. The production and secretion of ExoS, as judged by Western blotting, were restored in the ΔPA0612 and ΔPA0612-013 mutants but not in the ΔPA0613 mutant (Fig. 4A). The reporter plasmid of exoT-lacZ (pHW0006) was further transformed into these mutants and subjected to a β-galactosidase assay. As the results show in Fig. 4B, transcription of the exoT gene was partially restored in the backgrounds of ΔprtNprtR::GmΔPA0612-013 and ΔprtNprtR::GmΔPA0612 mutants, while they remained repressed in the background of the ΔprtNprtR::GmΔPA0613 mutant, indicating that PA0612 is required for repression of the TTSS in the prtR mutant background.

FIG. 4.

Characterization of ExoS expression and cytotoxicity. (A) Cellular and secreted forms of the ExoS in strains PAK, ΔprtNR::Gm, ΔprtNR::GmΔPA0612-0613, ΔprtNR::GmΔPA0612, and ΔprtNR::GmΔPA0613. Overnight bacteria cultures were diluted to 1% in LB or 3% in LB plus 5 mM EGTA and grown at 37°C for 3.5 h. Supernatants and pellets from equivalent bacterial cell numbers were loaded onto SDS-PAGE gels and immunoblotted with anti-ExoS antibody. Both ExoS and ExoT are indicated by arrows. (B) Expression of exoS::lacZ(pHW0005) in the backgrounds of PAK, ΔprtNR::Gm, ΔprtNR::GmΔPA0612-0613, ΔprtNR::GmΔPA0612, and ΔprtNR::GmΔPA0613. Bacteria were grown to an OD600 of 1 to 2 in LB with or without EGTA before β-galactosidase assays. (C) Cell lifting assay. HeLa cells were infected with PAK, prtR::Tn5, ΔprtNR::Gm, ΔprtNR::GmΔPA0612-0613, ΔprtNR::GmΔPA0612, and ΔprtNR::GmΔPA0613 at an MOI of 20. After a 4-hour infection, cell lifting was measured with crystal violet staining (see Materials and Methods for details). *, P < 0.01, compared to the values for PAK; **, P < 0.01, compared to the values for ΔprtNR::Gm.

The TTSS of PAK can directly deliver ExoS, ExoT, and ExoY into the host cell, resulting in cell rounding and lifting (16, 45, 46). HeLa cells were further infected with wild-type PAK and prtR mutants at a MOI of 20. Upon infection by PAK, almost all of the HeLa cells were rounded after 2.5 h. Under the same conditions, the PAKexsA::Ω mutant, a TTSS-defective mutant, had no effect on HeLa cell rounding; similar results were seen with mutant strains prtR::Tn, ΔprtNprtR::Gm, and ΔprtNprtR::GmΔPA0613. However, ΔprtNprtR::GmΔPA0612-013 and ΔprtNprtR::GmΔPA0612 caused comparable levels of HeLa cell lifting as that seen with PAK. Quantitative assay of the cell lifting was further performed by crystal violet staining of the adhered cells after 4 h of infection. As shown in Fig. 4C, mutant strains ΔprtNprtR::GmΔPA0612-013 and ΔprtNprtR::GmΔPA0612 showed similar cytotoxicity as wild-type PAK. However, PrtR::Tn, ΔprtNprtR::Gm, and ΔprtNprtR::GmΔPA0613 showed much-reduced cytotoxicity. The above observations clearly indicated that PA0612, but not PA0613, is required for TTSS repression in the prtR mutant background. We designate this newly identified repressor gene as pseudomonas type III repressor gene B or, ptrB.

Mitomycin C-mediated suppression of the TTSS gene requires PtrB.

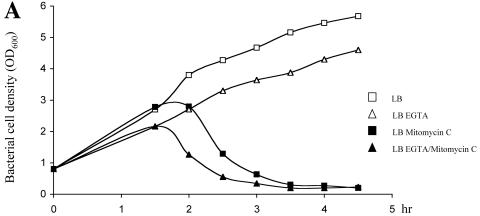

Pyocin production can be triggered by mutagenic agents, such as mitomycin C. In response to the DNA damage, RecA is activated and cleaves PrtR, similar to LexA cleavage by RecA in E. coli during the SOS response (35). In the absence of PrtR, the expression of prtN is derepressed, resulting in up regulation of the pyocin synthesis genes. Under this circumstance, the ptrB gene should also be up regulated, resulting in TTSS repression. To test this prediction, wild-type PAK was treated with mitomycin C under TTSS-inducing and -noninducing conditions and the expression of ExoS was monitored by Western blot analysis. In previous reports, 1 μg/ml of mitomycin C was shown to be able to induce pyocin synthesis (35). After treatment with 1 μg/ml of mitomycin C for 1.5 h, the OD600 of PAK began to decrease with or without EGTA due to the toxic effect of the mitomycin C (Fig. 5A); therefore, we collected the samples 1.5 h after mitomycin C treatment. Two culture methods were used. One was to grow PAK with mitomycin C for 30 min and then EGTA was added to induce TTSS for 1 hour. The other was to add mitomycin C and EGTA at the same time and induce for 1 hour. Experimental results showed that when wild-type PAK was treated with mitomycin C and EGTA at the same time, normal TTSS activation was observed. However, when cells were treated with mitomycin C 30 min before the addition of EGTA, a clear repression of the TTSS was observed (Fig. 5B). To test whether the ptrB gene mediates the repression of the TTSS by mitomycin C, a deletion mutant of ptrB was further generated in the background of wild-type PAK. Deletion of ptrB in PAK had no effect on expression of the TTSS (Fig. 5B and C). Interestingly, even with the 30-min pretreatment of mitomycin C (1 μg/ml), production of ExoS in the PAKΔptrB mutant was activated by EGTA, even higher than that without mitomycin C treatment (Fig. 5B). Clearly, mitomycin C-mediated suppression of the TTSS requires the ptrB gene.

FIG. 5.

Effect of mitomycin C on bacteria growth and TTSS activity. (A) An overnight culture of PAK was diluted to an OD600 of 0.8 in LB, LB plus 1 μg/ml mitomycin C, LB plus 5 mM EGTA, or LB plus 1 μg/ml mitomycin C plus 5 mM EGTA. The OD600 of each sample was measured at 30-min intervals. (B) Overnight cultures of PAK, ΔPA0612-0613, and ΔptrB were diluted to an OD600 of 0.5 with LB or LB plus 1 μg/ml mitomycin C. After 30 min, EGTA was added to culture medium at a final concentration of 5 mM. One hour later, each culture was mixed with protein loading buffer. Samples derived from equivalent bacterial cell numbers were loaded onto SDS-PAGE gels and immunoblotted with anti-ExoS antibody. *, PAK was grown in LB for 30 min, and then both mitomycin C and EGTA were added at the same time. (C) Overnight cultures of PAK, ΔPA0612-0613, and ΔptrB strains were diluted to 1% in LB or 3% in LB plus 5 mM EGTA and grown at 37°C for 3.5 h. Supernatants and pellets from equivalent bacterial cell numbers were loaded onto SDS-PAGE gels and immunoblotted with anti-ExoS antibody.

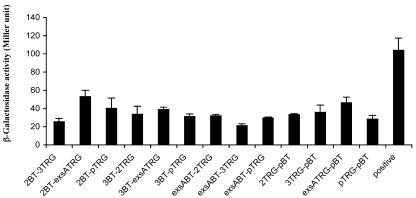

PtrB does not directly interact with ExsA.

In earlier reports, it has been shown that ExsA activity can be repressed by interaction with ExsD or PtrA (17, 34). We wanted to test if the TTSS repressor function of PtrB is achieved through a direct interaction with the master regulator, ExsA. A bacterial two-hybrid system (Stratagene) was used to test the interaction between the two components. ptrB and exsA were each cloned into bait (pBT) or prey (pTRG) plasmids. Interaction between the two proteins was indicated by the expression of lacZ in the reporter strain. β-Galactosidase assay results, however, did not suggest a direct interaction between PtrB and ExsA, although strong interaction was observed between the positive controls provided (Fig. 6). Therefore, the mechanism of TTSS repression in the prtR mutant does not involve a direct binding of PtrB to ExsA. Negative results were also obtained in similar tests between PtrB and PA0613, indicating no direct interaction of the two small proteins encoded in the same operon.

FIG. 6.

Monitoring of protein-protein interactions by the BacterioMatch two-hybrid system. pBT, bait vector; pTRG, target vector; 2BT, ptrB cloned into bait vector; 2TRG, ptrB cloned into target vector; 3BT, PA0613 cloned into bait vector; 3TRG, PA0613 cloned into target vector; exsABT, exsA cloned into bait vector; exsATRG, exsA cloned into target vector; positive, positive control provided by the manufacturer.

The TTSS genes have been shown to be affected by Vfr and CyaA/B, homologues of CRP and cyclic AMP synthase (49). Vfr is well known for its involvement in the regulation of twitching motility (4), flagellum synthesis (10), type II secretion (49), and quorum sensing (37). Recently, FimL was found to regulate both the TTSS and twitching motility through Vfr (47). To test whether mutation of prtR affects twitching motility, strains with prtR and ptrB mutations were subjected to a stab assay. Mutation in the prtR or ptrB gene had no effect on twitching motility, indicating that the repression of the TTSS in the prtR mutant does not go through the Vfr pathway.

DISCUSSION

The TTSS of P. aeruginosa is under the control of a complicated regulatory network. ExsA, an AraC-type protein, is the master activator of the TTSS. Two proteins, ExsD and PtrA, have been found to directly interact with ExsA. ExsD is an antiactivator, inhibiting the activity of ExsA (34). PtrA is an in vivo inducible protein and represses the activity of ExsA through direct binding. In vitro, the expression of PtrA is inducible by high copper stress signal through a CopR/S two-component regulatory system (17). We have also found that mutation in the mucA gene not only results in overproduction of alginate but also causes repression of the TTSS (50). mucA-regulated alginate production is induced by environmental stresses, such as high osmolarity, reactive oxygen intermediates, and anaerobic environment (15, 32). Metabolic imbalance was also shown to cause repression of the TTSS, which reflects a nutritional stress (9, 39). Here we report that mutation in the prtR gene results in the repression of the TTSS. PrtR is a repressor whose activity is regulated by DNA damage (35), yet another stress signal. Mitomycin C, a mutagenic agent, can indeed repress the activity of the TTSS. These discoveries indicate that the TTSS is effectively turned off under various environmental stresses, which might be an important survival strategy for this microorganism. Since mounting an effective resistance against stress requires a full devotion of energy, turning off other energy-expensive processes, such as the TTSS, will be beneficial to the bacterium.

During early infection of cystic fibrosis patients, P. aeruginosa produces S-type pyocins (5); however, the exact physiological role played by pyocins is unclear. Pyocins might ensure the predominance of a given strain in a bacterial niche against other bacteria of the same species. The pyocin production starts when adverse conditions provoke DNA damage. Under these conditions, the effect of pyocins is likely to preserve the initial predominance of pyocinogenic bacteria against pyocin-sensitive cells (35). Upon activation by DNA-damaging agents, RecA mediates the cleavage of PrtR, derepressing the expression of prtN, resulting in active synthesis of pyocins. Thus, the pyocin synthesis is dependent on the SOS response, resembling those responses of temperate bacteriophages in E. coli (43). Indeed, DNA-damaging agents, such as UV irradiation and mitomycin C, induce the synthesis of pyocins in a recA-dependent manner (35). Apparently, in response to the DNA damage stress signal, P. aeruginosa not only turns on the SOS response system for DNA repair and pyocin synthesis but also actively represses the type III secretion system, another example of coordinated gene regulation for survival.

Along the regulatory pathway, mutation of the prtR gene results in the up regulation of prtN (33). We found that PrtN is not responsible for the repression of the TTSS; rather, ptrB next to and under the control of prtR is required for the TTSS repression. We also found that the downstream gene PA0613 was in the same operon with PA0612. Homologues of these genes are also found in Pseudomonas putida (PP3039 and PP3037) and Pseudomonas syringae (PSPT03417 and PSPT03419), where they seem to also form operon structures, although with one additional gene between them (PP3038 or PSPR03418). The promoter of ptrB contains a 14-base sequence that was also found in the prtN promoter (33), which may be a binding site for PrtR. Considering that PrtR is the ortholog of λCI, which functions as a homodimer (43), PrtR may also form a dimer. Whether PrtR recognizes these potential binding sites is not known. Interestingly, the PtrB protein contains a prokaryotic DksA/TraR C4-type zinc-finger motif (www.pseudomonas.com). The dksA gene product suppresses the temperature-sensitive growth and filamentation of a dnaK deletion mutant of Escherichia coli (23), while TraR is involved in plasmid conjugation (12). These proteins contain a C-terminal region thought to fold into a four-cysteine zinc-finger (12). Yersinia sp. also encodes a small-sized protein, YmoA (8 kDa), which negatively regulates the type III secretion system (30). YmoA resembles the histone-like protein HU and E. coli integration host factor; thus, it is likely to repress type III genes through its influence on DNA conformation. Whether PtrB exerts its repressor function through interaction with another regulator or through binding to specific DNA sequences present in the TTSS operons or their upstream regulator genes is not known. It would also be interesting to study on what other genes of the P. aeruginosa genome PtrB exerts a regulatory effect.

It is not surprising that P. aeruginosa has multiple regulatory networks, since 8% of its genome codes for regulatory genes, indicating that P. aeruginosa has dynamic and complicated regulatory mechanisms responding to various environmental signals (40, 44). Also, due to the requirement of a large number of genes, construction of the type III secretion apparatus is an energy-expensive process. Thus, P. aeruginosa has evolved multiple signaling pathways to fine-tune the regulation of the type III secretion system in response to the environmental changes. Similarly, Yersinia has been reported to have several regulators, such as an activator, VirF, and repressor molecules, LcrQ, YscM1, YscM2, and YmoA, that are involved in the control of yop gene transcription (7, 48, 51). Current efforts are focused on the elucidation of the molecular mechanism by which PtrB mediates suppression of the TTSS. Also, the relevance of the two additional genes, PA2265 and PA5021, to the regulation of the TTSS is under investigation.

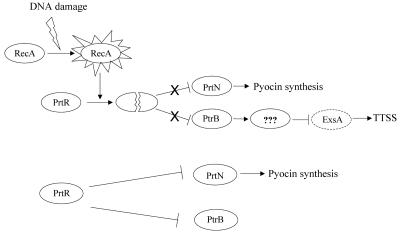

Based on our results, we propose a model for the repression of the TTSS induced by DNA damage (treatment with mitomycin C) (Fig. 7). DNA damage induces the SOS response, in which RecA is activated. RecA cleaves PrtR, resulting in the up regulation of prtN and ptrB. PrtN activates the expression of pyocin synthesis genes, while PtrB represses the TTSS genes.

FIG. 7.

Proposed model of PtrB-mediated TTSS repression. In wild-type PAK, PrtR represses the expression of prtN and ptrB. In response to DNA damage, RecA is activated and cleaves PrtR, resulting in increased expression of prtN and ptrB. PrtN activates the expression of pyocin synthesis genes, while PtrB represses the type III secretion genes directly or through additional downstream genes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Xiaoling Wang for assistance in HeLa cell infection assays.

This work is supported by a Research Scholar Award from the American Cancer Society (to S.J.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahn, K. S., U. Ha, J. Jia, D. Wu, and S. Jin. 2004. The truA gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is required for the expression of type III secretory genes. Microbiology 150:539-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbieri, J. T., and J. Sun. 2004. Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoS and ExoT. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 152:79-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baysse, C., J. M. Meyer, P. Plesiat, V. Geoffroy, Y. Michel-Briand, and P. Cornelis. 1999. Uptake of pyocin S3 occurs through the outer membrane ferripyoverdine type II receptor of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 181:3849-3851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beatson, S. A., C. B. Whitchurch, J. L. Sargent, R. C. Levesque, and J. S. Mattick. 2002. Differential regulation of twitching motility and elastase production by Vfr in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 184:3605-3613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beckmann, C., M. Brittnacher, R. Ernst, N. Mayer-Hamblett, S. I. Miller, and J. L. Burns. 2005. Use of phage display to identify potential Pseudomonas aeruginosa gene products relevant to early cystic fibrosis airway infections. Infect. Immun. 73:444-452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boucher, J. C., H. Yu, M. H. Mudd, and V. Deretic. 1997. Mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis: characterization of muc mutations in clinical isolates and analysis of clearance in a mouse model of respiratory infection. Infect. Immun. 65:3838-3846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cornelis, G. R., C. Sluiters, I. Delor, D. Geib, K. Kaniga, C. Lambert de Rouvroit, M. P. Sory, J. C. Vanooteghem, and T. Michiels. 1991. ymoA, a Yersinia enterocolitica chromosomal gene modulating the expression of virulence functions. Mol. Microbiol. 5:1023-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dacheux, D., I. Attree, C. Schneider, and B. Toussaint. 1999. Cell death of human polymorphonuclear neutrophils induced by a Pseudomonas aeruginosa cystic fibrosis isolate requires a functional type III secretion system. Infect. Immun. 67:6164-6167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dacheux, D., O. Epaulard, A. de Groot, B. Guery, R. Leberre, I. Attree, B. Polack, and B. Toussaint. 2002. Activation of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III secretion system requires an intact pyruvate dehydrogenase aceAB operon. Infect. Immun. 70:3973-3977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dasgupta, N., E. P. Ferrell, K. J. Kanack, S. E. West, and R. Ramphal. 2002. fleQ, the gene encoding the major flagellar regulator of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, is σ70 dependent and is downregulated by Vfr, a homolog of the Escherichia coli cyclic AMP receptor protein. J. Bacteriol. 184:5240-5250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dasgupta, N., G. L. Lykken, M. C. Wolfgang, and T. L. Yahr. 2004. A novel anti-anti-activator mechanism regulates expression of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III secretion system. Mol. Microbiol. 53:297-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doran, T. J., S. M. Loh, N. Firth, and R. A. Skurray. 1994. Molecular analysis of the F plasmid traVR region: traV encodes a lipoprotein. J. Bacteriol. 176:4182-4186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garrity-Ryan, L., S. Shafikhani, P. Balachandran, L. Nguyen, J. Oza, T. Jakobsen, J. Sargent, X. Fang, S. Cordwell, M. A. Matthay, and J. N. Engel. 2004. The ADP ribosyltransferase domain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoT contributes to its biological activities. Infect. Immun. 72:546-558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodman, A. L., B. Kulasekara, A. Rietsch, D. Boyd, R. S. Smith, and S. Lory. 2004. A signaling network reciprocally regulates genes associated with acute infection and chronic persistence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Dev. Cell 7:745-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Govan, J. R., and V. Deretic. 1996. Microbial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis: mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia. Microbiol. Rev. 60:539-574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ha, U., and S. Jin. 2001. Growth phase-dependent invasion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and its survival within HeLa cells. Infect. Immun. 69:4398-4406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ha, U. H., J. Kim, H. Badrane, J. Jia, H. V. Baker, D. Wu, and S. Jin. 2004. An in vivo inducible gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa encodes an anti-ExsA to suppress the type III secretion system. Mol. Microbiol. 54:307-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoang, T. T., R. R. Karkhoff-Schweizer, A. J. Kutchma, and H. P. Schweizer. 1998. A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site-specific excision of chromosomally-located DNA sequences: application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. Gene 212:77-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hogardt, M., M. Roeder, A. M. Schreff, L. Eberl, and J. Heesemann. 2004. Expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoS is controlled by quorum sensing and RpoS. Microbiology 150:843-851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hovey, A. K., and D. W. Frank. 1995. Analyses of the DNA-binding and transcriptional activation properties of ExsA, the transcriptional activator of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme S regulon. J. Bacteriol. 177:4427-4436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hueck, C. J. 1998. Type III protein secretion systems in bacterial pathogens of animals and plants. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:379-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jia, J., M. Alaoui-El-Azher, M. Chow, T. C. Chambers, H. Baker, and S. Jin. 2003. c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase-mediated signaling is essential for Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoS-induced apoptosis. Infect. Immun. 71:3361-3370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang, P. J., and E. A. Craig. 1990. Identification and characterization of a new Escherichia coli gene that is a dosage-dependent suppressor of a dnaK deletion mutation. J. Bacteriol. 172:2055-2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaufman, M. R., J. Jia, L. Zeng, U. Ha, M. Chow, and S. Jin. 2000. Pseudomonas aeruginosa mediated apoptosis requires the ADP-ribosylating activity of exoS. Microbiology 146:2531-2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuchma, S. L., J. P. Connolly, and G. A. O'Toole. 2005. A three-component regulatory system regulates biofilm maturation and type III secretion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 187:1441-1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larsen, R. A., M. M. Wilson, A. M. Guss, and W. W. Metcalf. 2002. Genetic analysis of pigment biosynthesis in Xanthobacter autotrophicus Py2 using a new, highly efficient transposon mutagenesis system that is functional in a wide variety of bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 178:193-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laskowski, M. A., E. Osborn, and B. I. Kazmierczak. 2004. A novel sensor kinase-response regulator hybrid regulates type III secretion and is required for virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 54:1090-1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee, F. K., K. C. Dudas, J. A. Hanson, M. B. Nelson, P. T. LoVerde, and M. A. Apicella. 1999. The R-type pyocin of Pseudomonas aeruginosa C is a bacteriophage tail-like particle that contains single-stranded DNA. Infect. Immun. 67:717-725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lory, S., M. Wolfgang, V. Lee, and R. Smith. 2004. The multi-talented bacterial adenylate cyclases. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 293:479-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Madrid, C., J. M. Nieto, and A. Juarez. 2002. Role of the Hha/YmoA family of proteins in the thermoregulation of the expression of virulence factors. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 291:425-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maresso, A. W., M. J. Riese, and J. T. Barbieri. 2003. Molecular heterogeneity of a type III cytotoxin, Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme S. Biochemistry 42:14249-14257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mathee, K., O. Ciofu, C. Sternberg, P. W. Lindum, J. I. Campbell, P. Jensen, A. H. Johnsen, M. Givskov, D. E. Ohman, S. Molin, N. Hoiby, and A. Kharazmi. 1999. Mucoid conversion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by hydrogen peroxide: a mechanism for virulence activation in the cystic fibrosis lung. Microbiology 145:1349-1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsui, H., Y. Sano, H. Ishihara, and T. Shinomiya. 1993. Regulation of pyocin genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by positive (prtN) and negative (prtR) regulatory genes. J. Bacteriol. 175:1257-1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCaw, M. L., G. L. Lykken, P. K. Singh, and T. L. Yahr. 2002. ExsD is a negative regulator of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III secretion regulon. Mol. Microbiol. 46:1123-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Michel-Briand, Y., and C. Baysse. 2002. The pyocins of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochimie 84:499-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mills, S. D., C. K. Lim, and D. A. Cooksey. 1994. Purification and characterization of CopR, a transcriptional activator protein that binds to a conserved domain (cop box) in copper-inducible promoters of Pseudomonas syringae. Mol. Gen. Genet. 244:341-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pesci, E. C., J. P. Pearson, P. C. Seed, and B. H. Iglewski. 1997. Regulation of las and rhl quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 179:3127-3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Richards, M. J., J. R. Edwards, D. H. Culver, and R. P. Gaynes. 1999. Nosocomial infections in medical intensive care units in the United States. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. Crit. Care Med. 27:887-892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rietsch, A., M. C. Wolfgang, and J. J. Mekalanos. 2004. Effect of metabolic imbalance on expression of type III secretion genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 72:1383-1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodrigue, A., Y. Quentin, A. Lazdunski, V. Mejean, and M. Foglino. 2000. Two-component systems in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: why so many? Trends Microbiol. 8:498-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenfeld, M., B. W. Ramsey, and R. L. Gibson. 2003. Pseudomonas acquisition in young patients with cystic fibrosis: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 9:492-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sato, H., J. B. Feix, C. J. Hillard, and D. W. Frank. 2005. Characterization of phospholipase activity of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III cytotoxin, ExoU. J. Bacteriol. 187:1192-1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Snyder, L., and W. Champness. 1997. Molecular genetics of bacteria. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 44.Stover, C. K., X. Q. Pham, A. L. Erwin, S. D. Mizoguchi, P. Warrener, M. J. Hickey, F. S. Brinkman, W. O. Hufnagle, D. J. Kowalik, M. Lagrou, R. L. Garber, L. Goltry, E. Tolentino, S. Westbrock-Wadman, Y. Yuan, L. L. Brody, S. N. Coulter, K. R. Folger, A. Kas, K. Larbig, R. Lim, K. Smith, D. Spencer, G. K. Wong, Z. Wu, I. T. Paulsen, J. Reizer, M. H. Saier, R. E. Hancock, S. Lory, and M. V. Olson. 2000. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 406:959-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sundin, C., B. Hallberg, and A. Forsberg. 2004. ADP-ribosylation by exoenzyme T of Pseudomonas aeruginosa induces an irreversible effect on the host cell cytoskeleton in vivo. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 234:87-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vallis, A. J., T. L. Yahr, J. T. Barbieri, and D. W. Frank. 1999. Regulation of ExoS production and secretion by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in response to tissue culture conditions. Infect. Immun. 67:914-920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Whitchurch, C. B., S. A. Beatson, J. C. Comolli, T. Jakobsen, J. L. Sargent, J. J. Bertrand, J. West, M. Klausen, L. L. Waite, P. J. Kang, T. Tolker-Nielsen, J. S. Mattick, and J. N. Engel. 2005. Pseudomonas aeruginosa fimL regulates multiple virulence functions by intersecting with Vfr-modulated pathways. Mol. Microbiol. 55:1357-1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilharm, G., W. Neumayer, and J. Heesemann. 2003. Recombinant Yersinia enterocolitica YscM1 and YscM2: homodimer formation and susceptibility to thrombin cleavage. Protein Expr. Purif. 31:167-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wolfgang, M. C., V. T. Lee, M. E. Gilmore, and S. Lory. 2003. Coordinate regulation of bacterial virulence genes by a novel adenylate cyclase-dependent signaling pathway. Dev. Cell 4:253-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu, W., H. Badrane, S. Arora, H. V. Baker, and S. Jin. 2004. MucA-mediated coordination of type III secretion and alginate synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 186:7575-7585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wulff-Strobel, C. R., A. W. Williams, and S. C. Straley. 2002. LcrQ and SycH function together at the Ysc type III secretion system in Yersinia pestis to impose a hierarchy of secretion. Mol. Microbiol. 43:411-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]