Abstract

The diversity and evolution of the class A OXY β-lactamase from Klebsiella oxytoca were investigated and compared to housekeeping gene diversity. The entire blaOXY coding region was sequenced in 18 clinical isolates representative of the four K. oxytoca β-lactamase gene groups blaOXY-1 to blaOXY-4 and of two new groups identified here, blaOXY-5 (with four isolates with pI 7.2 and one with pI 7.7) and blaOXY-6 (with four isolates with pI 7.75 and three with pI 8.1). Genes blaOXY-5 and blaOXY-6 showed 99.8% within-group nucleotide similarity but differed from each other by 4.2% and from blaOXY-1, their closest relative, by 2.5% and 2.9%, respectively. Antimicrobial susceptibility to β-lactams was similar among OXY groups. Nucleotide sequence diversity of the 16S rRNA (1,454 bp), rpoB (940 bp), gyrA (383 bp), and gapDH (573 bp) genes was in agreement with the β-lactamase gene phylogeny. Strains with blaOXY-1, blaOXY-2, blaOXY-3, blaOXY-4, and blaOXY-6 genes formed five phylogenetic groups, named KoI, KoII, KoIII, KoIV, and KoVI, respectively. Isolates harboring blaOXY-5 appeared to represent an emerging lineage within KoI. We estimated that the blaOXY gene has been evolving within K. oxytoca for approximately 100 million years, using as calibration the 140-million-year estimation of the Escherichia coli-Salmonella enterica split. These results show that the blaOXY gene has diversified along K. oxytoca phylogenetic lines over long periods of time without concomitant evolution of the antimicrobial resistance phenotype.

Klebsiella oxytoca is an important opportunistic pathogen causing serious infections in hospitalized patients, including neonates (16, 19, 28). K. oxytoca is naturally resistant to amino- and carboxy-penicillins (21), a phenotype due to the constitutive expression of a chromosomal class A β-lactamase (1), first called K1 (7, 20) or KOXY (26) and now OXY (12). Due to the hyperproduction of the chromosomal β-lactamase, up to 10 to 20% of K. oxytoca strains (22) can show high-level resistance to certain expanded-spectrum cephalosporins (ceftriaxone and cefotaxime) and aztreonam (8). Up mutations in the promoter sequence of the genes are responsible for this phenotype (9-11). Overproducers of OXY enzymes are commonly resistant to all combinations of β-lactams with β-lactam inhibitors (21).

Sequence diversity of the K. oxytoca chromosomal β-lactamase gene and the existence of discrete groups of OXY enzymes have been described. Fournier et al. (12) found a variant (blaOXY-2) of the chromosomal β-lactamase gene that differed from blaOXY-1 (1) by 12.7% in nucleotide sequence. It was suggested, based on colony hybridization, that the β-lactamase genes of K. oxytoca could be classified into two groups (OXY-1 and OXY-2), each representing approximately half of the clinical isolates (12). Recently, Granier et al. (14) identified two additional sequence variants, defined as blaOXY-3 and blaOXY-4, each found in a single strain so far. Gene blaOXY-3 shares 85 and 84% similarity with blaOXY-1 and blaOXY-2, respectively, whereas the corresponding values for blaOXY-4 are 95 and 86%, respectively.

The recognition of distinct groups of β-lactamase genes within a pathogenic species is relevant to the epidemiology and control of infections. From an evolutionary point of view, the existence of discrete groups of β-lactamase sequences within K. oxytoca could reflect the independent introduction of these variants by several horizontal transfer events from unknown donors. Alternately, these variants could have evolved from a common ancestral β-lactamase gene that was anciently present in K. oxytoca. Elements in support of the latter hypothesis include the chromosomal localization of the gene (1, 15) and the correspondence of β-lactamase variation with sequence variation in other regions of the chromosome. It was recently shown that OXY-1 and OXY-2 variant enzyme groups are harbored by two genetic groups of K. oxytoca strains, named OXY-1 and OXY-2 (15) and later oxy-1 and oxy-2 (14), that can be distinguished by rpoB and 16S rRNA gene sequences and by ERIC-1R PCR (15). In addition, it was suggested that K. oxytoca strain SG271, which harbors blaOXY-3, represents a new genetic group, named oxy-3 (14). In contrast, it was unclear whether blaOXY-4-harboring strain SG266 belongs to genetic group OXY-1 or instead to a new group closely related to OXY-1 (14). Independently, Brisse and Verhoef (4) demonstrated the existence of at least two K. oxytoca genetic groups, called KoI and KoII, based on gyrA and parC gene sequences, random amplified polymorphic DNA analysis, and automated ribotyping. However, the correspondence between the OXY-1 and OXY-2 groups (14, 15) and KoI and KoII groups (4) has not been investigated.

In order to challenge further the hypothesis of an evolutionary diversification of OXY variants from a common K. oxytoca ancestral enzyme, we investigated the possible congruence of β-lactamase gene phylogeny with the phylogeny derived from three housekeeping genes. In addition, we describe two new β-lactamase groups that we called blaOXY-5 and blaOXY-6.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

A total of 182 K. oxytoca clinical isolates from a previous study (3) were initially analyzed by PCR using OXY-1- and OXY-2-specific primers (13). We next selected 18 K. oxytoca strains for sequencing of several genes (Table 1). Four of these strains were representatives of the previously described KoI and KoII phylogenetic groups (4). Strains SG266, harboring blaOXY-4, and SG271, harboring blaOXY-3 (14), were kindly provided by M.-H. Nicolas-Chanoine. The remaining 12 isolates (Table 1) were selected based on OXY-1 and OXY-2 PCR assays (see Results). Identification was initially performed using a VITEK apparatus (bioMérieux) and the indole test and confirmed for the 18 selected strains based on their gyrA sequences (4).

TABLE 1.

K. oxytoca strains studied, β-lactamase (bla) gene sequences, housekeeping gene sequences, and their characteristicsa

| No. | Strain name(s) | Geographical source | Clinical source | Phylogenetic group | bla group | bla accession no. | Housekeeping gene accession no.

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rpoB | gyrA | gapDH | 16S rRNA | |||||||

| Study isolates | ||||||||||

| 1 | SB9 | Spain | Blood | KoI (f) | blaOXY-1 | AJ871864 | AJ871801 | AJ303591 | AJ871820 | AJ871855 |

| 2 | SB71 | France | Blood | KoI (f) | blaOXY-1 | AJ871865 | AJ871802 | AJ871839 | AJ871821 | AJ871856 |

| 3 | SB136 (ATCC 49131) | KoII (f) | blaOXY-2 | AJ871866 | AJ871803 | AF303608 | AJ871822 | AJ871857 | ||

| 4 | SB175 (ATCC 13182T) | KoII (f) | blaOXY-2 | AJ871867 | AJ871804 | AJ871840 | AJ871823 | AJ871858 | ||

| 5 | SG271 | Clinical | KoIII | blaOXY-3 (a) | AF491278 (a) | AJ871805 | AJ871842 | AJ871824 | NDb | |

| 6 | SG266 | Clinical | KoIV | blaOXY-4 (a) | AY077481 (a) | AJ871806 | AJ871841 | AJ871825 | ND | |

| 7 | SB2908 | Italy | Blood | KoI | blaOXY-5 | AJ871868 | AJ871807 | AJ871843 | AJ871826 | AJ871859 |

| 8 | SB2909 | Italy | Blood | KoI | blaOXY-5 | AJ871869 | AJ871808 | AJ871844 | AJ871827 | ND |

| 9 | SB2910 | Italy | Blood | KoI | blaOXY-5 | AJ871870 | AJ871809 | AJ871845 | AJ871828 | ND |

| 10 | SB2933 | Switzerland | Blood | KoI | blaOXY-5 | AJ871871 | AJ871810 | AJ871846 | AJ871829 | ND |

| 11 | SB2942 | Netherland | Blood | KoI | blaOXY-5 | AJ871872 | AJ871811 | AJ871847 | AJ871830 | AJ871860 |

| 12 | SB73 | France | Wound | KoVI | blaOXY-6 | AJ871873 | AJ871812 | AJ871848 | AJ871831 | AJ871861 |

| 13 | SB75 | Germany | Blood | KoVI | blaOXY-6 | AJ871874 | AJ871813 | AJ871849 | AJ871832 | ND |

| 14 | SB324 | Germany | Blood | KoVI | blaOXY-6 | AJ871875 | AJ871814 | AJ871850 | AJ871833 | ND |

| 15 | SB352 | France | Wound | KoVI | blaOXY-8 | AJ871876 | AJ871815 | AJ871851 | AJ871834 | ND |

| 16 | SB397 | South Africa | Blood | KoVI | blaOXY-6 | AJ871877 | AJ871816 | AJ871852 | AJ871835 | ND |

| 17 | SB3037 | Ukraine | Wound | KoVI | blaOXY-6 | AJ871878 | AJ871817 | AJ871853 | AJ871836 | AJ871862 |

| 18 | SB3051 | France | Blood | KoVI | blaOXY-6 | AJ871879 | AJ871818 | AJ871854 | AJ871837 | AJ871863 |

| K. oxytocac | ||||||||||

| 19 | SL781 (CIP104963) | France | KoI | blaOXY-1 (b) | Z30177 (b) | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| 20 | SG12 | France | KoI | blaOXY-1 (a) | AYO77482 (a) | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| 21 | SG337 | France | KoI | blaOXY-1 (a) | AYO77483 (a) | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| 22 | SG49 | France | KoI | blaOXY-1 (a) | AYO77486 (a) | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| 23 | KH66 | Sweden | KoI | blaOXY-1 (c) | Y17715 (c) | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| 24 | E23004 | Japan | KoI | blaOXY-1 (d) | M27459 (d) | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| 25 | SG77 | France | KoII | blaOXY-2 (a) | AY077488 (a) | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| 26 | SG43 | France | KoII | blaOXY-2 (a) | AY077487 (a) | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| 27 | SG176 | France | KoII | blaOXY-2 (a) | AY077485 (a) | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| 28 | (CIP106098) SL911 | France | KoII | blaOXY-2 (b) | Z49084 (b) | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| 29 | SC10,436 | KoII | blaOXY-2 (e) | AY055205 (e) | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

| 30 | KH11 | Sweden | KoII | blaOXY-2 (c) | Y17714 (c) | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| K. pneumoniae 31 | SB132 (ATCC 13883T) | KpI | blaSHV (g) | AJ635407 (g) | AJ871819 | AF303606 (f) | AJ875018 | ND | ||

Phylogenetic groups, bla groups, and bla accession numbers followed by letter in parentheses were previously determined. References: a, 14; b, 11; c,31; d,1; e,15a; f,4; g,18. Other accession numbers correspond to sequences determined in this work.

ND, not determined.

Nucleotide sequences included for comparison.

DNA preparation.

DNA templates were prepared by suspending a freshly grown colony (approximately 30 mg) in 200 μl of purified water, heating it at 94°C for 10 min, and submitting the extracts to minicentrifugation at 7,500 × g for 5 min. Supernatants were stored at −20°C until use.

PCR amplification.

In order to amplify the blaOXY gene, primers OXY-E and OXY-G (Table 2) were designed based on the alignment of previously published blaOXY-1 to blaOXY-4 gene sequences. The amplified portion that permitted us to determine the sequence of the entire β-lactamase coding region stretched from 189 bp upstream of the start codon to 37 bp downstream of the stop codon. The 50-μl PCR mixture contained 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.4), 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 μM each primer, and 100 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate. Samples were submitted to an initial denaturation step (30 s at 94°C), followed by 35 amplification cycles (94°C, 30 s; 50°C, 30 s; 72°C, 30 s) and a final elongation step of 5 min at 72°C. PCR products were visualized under UV light after agarose gel electrophoresis.

TABLE 2.

Primers, their sequences, and their positions on the gene

| Gene and primer | Sequence | Positionsa |

|---|---|---|

| bla | ||

| OXY-E | 5′-GGT TTT GGT AAC TGT GAC GGG-3′ | −189 to −168 |

| OXY-G | 5′-CAG AGT GCA GAG TGT TGC AG-3′ | 913 to 894 |

| OXY-H | 5′-GCG ACA ATA C(G/C)G CGA TGA-3′ | 397 to 414 |

| OXY1-A | 5′-CGT GGC GTA AAA CCG CCC TG-3′ | 14 to 33 |

| OXY1-B | 5′-GTC CGC CAA GGT AGC TAA TC-3′ | 442 to 423 |

| OXY2-A | 5′-AAG GCT GGA GAT TAA CGC AG-3′ | 285 to 304 |

| OXY2-B | 5′-GCC CGC CAA GGT AGC CGA TG-3′ | 439 to 420 |

| OXY5-B | 5′-GAT TAA AAA AGC GGA TTT AGT A-3′ | 297 to 318 |

| OXY5-C | 5′-GCC CGC CAA GGT AC CGA TA-3′ | 442 to 423 |

| OXY6-B | 5′-CGG ATG ATT CGC AAA CCC TT-3′ | 167 to 186 |

| OXY6-C | 5′-CGG GAT GGC TTT CGC TCT GC-3′ | 274 to 255 |

| rpoB | ||

| VIC2 | 5′-GGT TAC AAC TTC GAA GAC TC-3′ | 2469 to 2489 |

| VIC3 | 5′-GGC GAA ATG GC(A/T) GAG AAC CA-3′ | 1442 to 1422 |

| gyrA | ||

| gyrA-A | 5′-CGC GTA CTA TAC GCC ATG AAC GTA-3′ | 139 to 163 |

| gyrA-C | 5′-ACC GTT GAT CAC TTC GGT CAG G-3′ | 762 to 741 |

| gapDH | ||

| gapF-173 | 5′-TGA AAT ATG ACT CCA CTC ACG G-3′ | 135 to 153 |

| gapR-181 | 5′-CTT CAG AAG CGG CTT TGA TGG CTT-3′ | 771 to 747 |

| rrs | ||

| Ad | 5′-AGA GTT TGA TCM TGG CTC AG-3′ | 8 to 27 |

| rJ | 5′-GGT TAC CTT GTT ACG ACT T-3′ | 1508 to 1491 |

| D | 5′-CAG CAG CCG CGG TAA TAC-3′ | 518 to 535 |

| E | 5′-ATT AGA TAC CCT GGT AGT CC-3′ | 786 to 805 |

| rE | 5′-GGA CTA CCA GGG TAT CTA AT-3′ | 805 to 786 |

The first position refers to the start codon, exept for the rrs sequences, for which the first position corresponds to the first nucleotide of the sequence available under accession number Y01859 in the GenBank database.

Specific blaOXY-1 and blaOXY-2 PCR assays were performed using previously defined (13) primers OXY1-A and OXY1-B and primers OXY2-A and OXY2-B, respectively (Table 2), at an annealing temperature of 50°C.

The nearly complete sequence of the 16S rRNA gene (rrs) was obtained using PCR primers Ad and rJ (Table 2). PCR amplification conditions were as described above. Cycling conditions were 4 min at 94°C, followed by 35 cycles (94°C, 1 min; 49°C, 1 min; 72°C, 1 min) and 7 min at 72°C.

Three housekeeping gene portions were amplified by PCR. The sequence of a 940-bp portion of the RNA polymerase beta subunit gene (rpoB) was determined using primers VIC2 and VIC3 (Table 2). The sequence of a 383-bp portion of the gyrase subunit A gene (gyrA) was determined as previously described (4). The sequence of a 573-bp portion of the glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene (gapDH) was determined using primers gapF-173 and gapR-181 (Table 2). PCR amplification conditions were as described for the β-lactamase gene, except that the annealing temperature was 55°C for rpoB and 60°C for gapDH.

PCR primer pairs were designed to specifically amplify β-lactamase genes of the blaOXY-5 and blaOXY-6 groups: OXY5-B, OXY5-C, OXY6-B, and OXY6-C (Table 2). PCR conditions were as described above, using an annealing temperature of 55°C.

Sequence determination.

PCR products and sequence reaction products were purified by the ultrafiltration method (Millipore). The Ready Reaction Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing v3.1 kit (Perkin-Elmer) and an ABI 3700 automated capillary DNA sequencer (Perkin-Elmer) were used. Primers used for sequencing were the same as those used for amplification. For the 1,102-bp blaOXY gene product amplified with primers OXY-E and OXY-G, the internal sequencing primer OXY-H was used in addition (Table 2). For 16S rRNA gene sequencing, internal primers D, E, and rE (Table 2) were used in addition to the PCR primers.

Phylogenetic analysis.

Sequence alignments were obtained using the MegAlign program of the LaserGene package (DNA Star Inc., Madison, Wisconsin). Phylogenetic trees were obtained with PAUP* version 4.0b10 (30), using the neighbor-joining method based on Kimura's two parameter distance. Bootstrap analysis was performed with 1,000 replicates. Trees generated by PAUP* were saved and drawn using TreeEdit v1.0a10 (built by A. Rambaut and M. Charleston in 2001 [http://evolve.zoo.ox.ac.uk]). Numbers of synonymous substitutions per synonymous site (Ks) and of nonsynonymous substitutions per nonsynonymous site (Ka) were estimated using DNASP version 3.53 (29). Sequences of rpoB and gyrA used for calibration of the substitution rate were derived from Salmonella paratyphi A strain ATCC 9150 and Escherichia coli strain K-12.

Determination of MICs.

Antimicrobial susceptibility was determined by the dilution method on Müller-Hinton agar according to the recommendations of the French Society for Microbiology (6). The following drugs were used: amoxicillin, ceftazidime, clavulanate, and ticarcillin from GlaxoSmithKline; piperacillin, cephalothin, and cefoxitin from Sigma-Aldrich; cefotaxime from PanPharma; cefepime from Bristol-Myers Squibb; imipenem from Merck Sharp & Dohme-Chibret; aztreonam from Sanofi-Synthelabo; and tazobactam from Wyeth.

Isoelectric focusing.

Crude extracts of β-lactamases were obtained by sonication. Isoelectric focusing was performed using a PhastSystem apparatus with PhastGel IEF 3-9 or 5-8 gels (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany) and following the manufacturer's recommendations. β-Lactamase activity was revealed by staining the gel with 0.5 mg/ml of the chromogenic β-lactam nitrocefin (Oxoid, Basingstoke, England). The β-lactamases used as references were TEM-1 (pI 5.4), TEM-52 (pI 6), SHV-3 (pI 7.0), OXA-30 (pI 7.3), SHV-1 (pI 7.6), OXY-3 (pI 7.7), OXA-35 (pI 8.0), and SHV-5 (pI 8.2).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The β-lactamase, 16S rRNA, rpoB, gyrA, and gapDH gene sequences determined in this study have been submitted to the EMBL and GenBank databases and assigned the accession numbers listed in Table 1.

RESULTS

Correspondence between phylogenetic groups KoI and KoII and β-lactamase genes blaOXY-1 and blaOXY-2.

In order to establish a possible correspondence between classifications of K. oxytoca strains (4) and OXY β-lactamases (12), 183 isolates (182 clinical isolates and 1 from a rice plant) were identified by characterization of the gyrA gene and analyzed by PCR using blaOXY group-specific primers (13). Based on gyrA characterization, 80 isolates could be assigned to KoI, whereas 96 isolates were assigned to KoII and 7 isolates represented a new gyrA phylogenetic group (called group KoVI; see below). Of the 80 KoI isolates, 75 were blaOXY-1 PCR positive and blaOXY-2 PCR negative. The five remaining isolates were atypical, being negative for both PCR assays. The 96 KoII isolates were blaOXY-1 PCR negative and blaOXY-2 PCR positive. The seven KoVI isolates showed the opposite result, being blaOXY-1 PCR positive and blaOXY-2 PCR negative. Therefore, we concluded that the OXY-1 and OXY-2 β-lactamase groups corresponded to the KoI and KoII phylogenetic groups, respectively, with the exception of five atypical KoI isolates. In addition, a new gyrA lineage was found, which apparently had a β-lactamase gene corresponding to or related to blaOXY-1.

β-Lactamase gene sequencing.

The nucleotide sequence of the β-lactamase gene was determined (using PCR primers OXY-E and OXY-G) for the five KoI isolates that were negative for primer OXY1-A and OXY1-B and primer OXY2-A and OXY2-B PCR assays, for the seven KoVI isolates, and for two reference strains each of the KoI and KoII phylogenetic groups (Table 1). Twelve blaOXY-1 and blaOXY-2 sequences, as well as the blaOXY-3 (strain SG271) and blaOXY-4 (strain SG266) sequences, were retrieved from public databases (Table 1). Considering only the coding region, 23 distinct sequences were found. Besides deletions at codons 11, 12, 25, and 26, there were 207 polymorphic nucleotide sites, of which 66 were variable in only one sequence (singletons) and 141 were variable in at least two sequences (informative sites). The deduced amino acid sequences showed 51 variable amino acid positions. The nucleotide substitutions were approximately three times more frequently synonymous (n = 158) than nonsynonymous (n = 51).

Phylogenetic analysis.

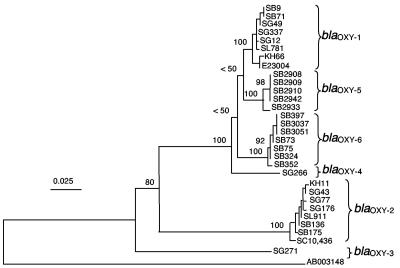

The neighbor-joining tree (Fig. 1) obtained for the 30 sequences revealed six branches. The first included the six strains previously described as harboring blaOXY-1 and the two KoI reference strains SB9 and SB71. The second branch included the six strains previously described as harboring blaOXY-2 and two KoII reference strains, SB136 (= ATCC 49131) and SB175 (= ATCC 13182T). These results firmly demonstrate the correspondence of β-lactamase groups blaOXY-1 and blaOXY-2 with phylogenetic groups KoI and KoII, respectively. The third and fourth branches each comprised a single isolate, corresponding to blaOXY-3 and blaOXY-4. The fifth branch was formed by the five atypical KoI isolates, whereas the sixth corresponded to the seven KoVI isolates. We propose to refer to the β-lactamase genes of these two new groups as blaOXY-5 and blaOXY-6, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Phylogeny of the K. oxytoca β-lactamase gene. The neighbor-joining tree was rooted using as an outgroup the gene sequence of the SFO-1 β-lactamase (GenBank accession no. AB003148), the closest relative of blaOXY. Values at the nodes correspond to bootstrap values obtained after 1,000 replicates. Six major branches of K. oxytoca β-lactamase sequences are visible, corresponding to the blaOXY-1 to blaOXY-6 β-lactamase gene groups.

The mean nucleotide sequence similarity was clearly higher within all six β-lactamase groups (at least 99.7%) than between any pair of them (see Table 4), as the smallest intergroup difference, observed between the blaOXY-1 and blaOXY-5 groups, was 2.5%.

TABLE 4.

Percent average nucleotide and aminoacid β-lactamase sequence similarity within and among bla OXY groupsa

| Group (no. of strains) | Avg % similarity (SD)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| blaOXY-1 | blaOXY-2 | blaOXY-3 | blaOXY-4 | blaOXY-5 | blaOXY-6 | |

| blaOXY-1 (8) | 99.7 (0.09)/99.4 (0.4) | 87.2 (2.3) | 86.2 (5) | 95.2 (1.7) | 97.5 (0.5) | 97.1 (0.5) |

| blaOXY-2 (8) | 89.5 (0.4) | 99.7 (0.1)/99.4 (0.4) | 84.9 (5.6) | 86.2 (5) | 87 (2.9) | 86.5 (2.6) |

| blaOXY-3 (1) | 90.9 (0.2) | 88.6 (0.5) | 100 (0)/100 (0) | 86.3 (0.0) | 85.1 (6.7) | 85.6 (5.6) |

| blaOXY-4 (1) | 96.8 (0.3) | 88.3 (0.3) | 90 (0) | 100 (0)/100 (0) | 95.9 (1.7) | 95.6 (0.1) |

| blaOXY-5 (5) | 97.5 (0.3) | 91.5 (0.3) | 90.3 (0) | 97.2 (0.4) | 99.8 (0.1)/99.7 (0.4) | 95.8 (1) |

| blaOXY-6 (7) | 98.3 (0.3) | 88.7 (0.3) | 91.2 (0.3) | 97.7 (0.2) | 97 (0.2) | 99.8 (0.1)/99.7 (0.2) |

Above diagonal, nucleotide sequence similarity; below diagonal, amino acid sequence similarity; inside diagonal cells: nucleotide/amino acid sequence similarities.

Amino acid sequence diversity of the two new β-lactamase groups, OXY-5 and OXY-6.

Among the five isolates harboring blaOXY-5, two alleles were distinguished, corresponding to two distinct amino acid sequences, OXY-5-1 and OXY-5-2 (Table 3). These two variants differed by two amino acids, at Ambler positions 39 and 153. Both variants differed from the OXY-1 β-lactamase of strain SL781 by five amino acids, located at Ambler positions 12 (deleted in OXY-5 variants), 100, 138, 140, and 165. None of these changes was specific for OXY-5, as they were also observed in OXY-2, OXY-3, and/or OXY-4 (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Amino acid sequence variation among OXY-1 to OXY-6 β-lactamase (bla) groups

| Strain | bla allelea | Enzymea | pI | Amino acid at position (Ambler no.):

|

Amino acid at position (Ambler no.):

|

Amino acid at position (Ambler no.):

|

Amino acid at position (Ambler no.):

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 4 | 9 (5) | 11 (7) | 12 (8) | 15 (11) | 16 (12) | 17 (13) | 22 (18) | 24 (20) | 25 (21) | 29 (25) | 30 (26) | 31 (27) | 32 (28) | 33 (29) | 34 (30) | 38 (34) | 39 (35) | 43 (39) | 44 (40) | 54 (50) | 56 (52) | 58 (54) | 61 (56) | 75 (72) | 90 (87) | 91 (88) | 92 (89) | 101 (98) | 102 (99) | 103 (100) | 111 (108) | 129 (126) | 140 (137) | 141 (138) | 143 (140) | 156 (153) | 161 (158) | 168 (165) | 171 (168) | 174 (171) | 180 (177) | 184 (181) | 194 (190) | 200 (197) | 230 (227) | 233 (230) | 240 (237) | 256 (255) | 261 (260) | 262 (261) | 270 (269) | 275 (274) | 278 (277) | ||||

| SL781 | blaOXY-1-1a | OXY-1-1 | 7.5b | L | S | T | L | M | A | A | V | A | G | S | S | A | D | A | I | Q | A | D | R | S | N | A | D | T | G | N | P | E | K | K | S | I | A | K | M | S | Q | V | T | A | S | K | T | R | N | A | A | A | N | V | L | Q | S | E |

| SB71 | blaOXY-1-2a | OXY-1-2 | 7.7 | V | G | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SB9 | blaOXY-1-2a | OXY-1-2 | 7.7 | V | G | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SG12 | blaOXY-1-3a | OXY-1-3 | NAc | G | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SG337 | blaOXY-1-4a | OXY-1-4 | NA | Deld | V | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SG49 | blaOXY-1-5a | OXY-1-5 | NA | V | G | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| KH66 | blaOXY-1-6a | OXY-1-6 | 5.25b | P | K | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| E23004 | blaOXY-1-7a | OXY-1-7 | 7.4b | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SG271 | blaOXY-3-1a | OXY-3-1 | 6.7b | I | T | S | I | Del | L | C | S | Del | Del | N | S | T | D | T | N | I | K | D | A | V | G | R | T | E | H | V | L | D | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SG266 | blaOXY-4-1a | OXY-4-1 | 7.7b | S | Del | T | L | H | D | I | G | M | G | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SB2908 | blaOXY-5-1a | OXY-5-1 | 7.2 | Del | H | T | A | I | G | M | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SB2909 | blaOXY-5-1a | OXY-5-1 | 7.2 | Del | H | A | I | G | M | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SB2910 | blaOXY-5-1a | OXY-5-1 | 7.2 | Del | H | A | I | G | M | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SB2942 | blaOXY-5-1a | OXY-5-1 | 7.2 | Del | H | A | I | G | M | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SB2933 | blaOXY-5-2a | OXY-5-2 | 7.7 | Del | A | I | G | L | M | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SB73 | blaOXY-6-1a | OXY-6-1 | 7.75 | S | H | D | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SB75 | blaOXY-8-1a | OXY-6-1 | 7.75 | S | H | D | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SB324 | blaOXY-6-2a | OXY-6-2 | 7.75 | S | Del | H | D | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SB352 | blaOXY-5-3a | OXY-6-3 | 7.75 | S | T | H | D | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SB397 | blaOXY-6-4a | OXY-6-4 | 8.1 | S | N | H | D | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SB3037 | blaOXY-6-4a | OXY-6-4 | 8.1 | S | N | H | D | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SB3051 | blaOXY-6-4a | OXY-6-4 | 8.1 | S | N | H | D | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SB136 | blaOXY-2-1a | OXY-2-1 | NA | I | I | M | L | Del | A | T | H | T | N | I | S | K | N | A | A | T | L | I | G | H | A | T | T | E | S | D | E | V | D | N | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SB175 | blaOXY-2-2a | OXY-2-2 | NA | I | I | M | L | Del | A | T | H | T | N | I | S | K | N | A | A | T | L | I | G | R | A | T | T | E | S | D | E | V | D | I | N | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| SG77 | blaOXY-2-3a | OXY-2-3 | NA | I | I | M | L | Del | Del | A | T | H | T | N | I | S | K | N | A | A | T | L | I | G | R | A | T | T | E | S | D | E | V | G | D | I | N | |||||||||||||||||||||

| KH11 | blaOXY-2-4a | OXY-2-4 | NA | I | I | M | L | Del | Del | A | T | H | T | N | I | S | K | N | A | A | T | L | I | G | R | A | T | T | E | S | D | E | V | D | N | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| SG43 | blaOXY-2-5a | OXY-2-5 | NA | I | I | M | L | Del | Del | A | T | H | T | N | I | S | K | N | A | A | T | L | I | G | R | A | T | T | E | S | D | E | V | D | N | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| SG176 | blaOXY-2-6a | OXY-2-6 | NA | I | I | M | L | Del | S | A | T | H | T | N | I | S | K | N | A | A | T | L | I | G | R | A | T | T | E | S | D | E | V | D | N | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| SL911 | blaOXY-2-7a | OXY-2-7 | NA | I | I | M | L | Del | A | T | H | T | N | I | S | K | N | A | A | T | L | I | G | R | A | T | T | E | S | D | E | V | D | N | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SC10,436 | blaOXY-2-8a | OXY-2-8 | NA | I | I | M | L | Del | S | A | T | H | T | N | I | S | K | N | A | A | T | L | I | G | R | A | T | T | E | S | A | E | V | N | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Numbered in this study.

Value from the literature.

NA, not available.

Del, deletion.

Among the seven isolates harboring blaOXY-6, four alleles were found, corresponding to four distinct amino acid sequences, OXY-6-1 to OXY-6-4 (Table 3). These variant enzyme sequences differed by their combination of three amino acid differences at Ambler positions 12 (deleted in strain SB324), 35, and 52, and they presented three common differences compared to the SL781 OXY-1 sequence, at positions 5, 87, and 89. None of these changes was specific for the OXY-6 β-lactamase group, as they were also observed in OXY-3 and/or OXY-4 sequences (Table 3).

The amino acid sequence similarity levels confirmed the distinctness of the two new β-lactamase groups. The highest amino acid sequence similarity of OXY-5 and OXY-6 sequences was observed with OXY-1 (97.5 and 98.3%, respectively) and with OXY-4 (97.2 and 97.7%, respectively), whereas the intragroup value was 99.7% both for OXY-5 and for OXY-6. The most distant amino acid sequences were OXY-2 and OXY-3 (Table 4).

Isoelectric focusing.

Analytical isoelectric focusing revealed a single β-lactamase band in all strains. The two distinct OXY-5 amino acid variants differed by their pI values (7.2 for OXY-5-1 and 7.7 for OXY-5-2). In contrast, the four distinct OXY-6 variants exhibited only two distinct pI values, 7.75 (for OXY-6-1, OXY-6-2, and OXY-6-3) and 8.1 (for OXY-6-4). These pI differences are in full agreement with the expected effects of the deduced amino acid changes (Table 3).

Antibiotic susceptibility testing.

The MICs of 10 β-lactams and three β-lactam-β-lactam inhibitor combinations were determined (Table 5). The susceptibility level observed for strains harboring blaOXY-5 and blaOXY-6 were similar to the values observed for the strains of the OXY-1 and OXY-2 β-lactamase groups. The MICs of amoxicillin, ticarcillin, and piperacillin were slightly lower for strains SG271 (OXY-3) and SG266 (OXY-4). All strains showed resistance against amoxicillin and ticarcillin, which was inhibited in the presence of clavulanate. Resistance to piperacillin was intermediate and fell in the presence of tazobactam. Susceptibility to all other β-lactams tested was observed. The sequence of the promoter region was established for the five blaOXY-5 and seven blaOXY-6 strains. In agreement with the observed MICs, there were no mutations previously reported to increase the transcription rate.

TABLE 5.

MICs of 10 β-lactams and three β-lactam-β-lactam inhibitor combinations observed for strains harboring blaOXY-1 to blaOXY-6 β-lactamase genes

| Drug(s) | MIC (μg/ml)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| blaOXY-1 strains SB9, SB71 | blaOXY-2 strains SB136, SB175 | blaOXY-3 strains SG271a | blaOXY-4 strains SG266a | blaOXY-5 strains SB2908, SB2933 | blaOXY-6 strains SB73, SB324, SB352, SB397 | |

| Amoxicillin | 256 | 512 | 16 | 64 | 256 | 256 |

| Amoxicillin + 2 μg/ml of clavulanate | 4 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 4 | 2-4 |

| Ticarcillin | 128 | 128 | 16 | 64 | 128 | 64-128 |

| Ticarcillin + 2 μg/ml of clavulanate | 2 | 2 | 0.5 | 2 | 2 | 1-2 |

| Piperacillin | 16-32 | 16-32 | 1 | 2 | 8-32 | 8-32 |

| Piperacillin + 4 μg/ml of tazobactam | 2 | 1-2 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 2-4 | 2-4 |

| Cephalothin | 4-8 | 16 | 2 | 2 | 2-4 | 4-8 |

| Cefoxitin | 4-8 | 2 | 0.5 | 1 | 2-8 | 4-8 |

| Cefotaxime | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06-0.125 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 |

| Ceftazidime | 0.125-0.25 | 0.125-0.25 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | 0.125-0.25 | 0.25-0.5 |

| Cefepime | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06-0.125 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 |

| Aztreonam | ≤0.06-0.25 | 0.25 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06-0.125 | ≤0.06-0.25 |

| Imipenem | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.125 | 0.125 |

Values previously published (14).

blaOXY-5- and blaOXY-6-specific PCR assays.

The 18 isolates were subjected to amplification with two primer pairs, primers OXY5-B and OXY5-C and primers OXY6-B and OXY6-C. These pairs were designed on regions containing group-specific nucleotide substitutions. OXY5-B and OXY5-C PCR amplification of the expected 127-bp fragment was positive for all isolates harboring the blaOXY-5 β-lactamase gene and negative for isolates of all other groups. Conversely, amplification of the 107-bp fragment expected with primers OXY6-B and OXY6-C was positive only with isolates harboring blaOXY-6 (data not shown).

Correspondence between β-lactamase and housekeeping gene diversity.

In order to compare the phylogeny based on the β-lactamase gene with the evolutionary history of other regions of the K. oxytoca chromosome, the nucleotide sequences of portions of the three housekeeping genes rpoB (940 nucleotides [nt] sequenced), gyrA (383 nt), and gapDH (573 nt) were determined in the 18 study isolates. For the three protein coding genes, the alignment revealed no insertion or deletion event, and there was no ambiguous data. The proportion of polymorphic sites was 8.72% (82/940 nt) for rpoB, 8.35% (32/383 nt) for gyrA, and 6.8% (39/573 nt) for gapDH, whereas it was 23% (203/876 nt) for blaOXY (Table 6). The smaller amount of variable sites in the housekeeping genes was mainly due to the rarity of nonsynonymous substitutions (Table 6), indicative of stronger selective pressure against amino acid changes in the three housekeeping genes, relative to the blaOXY gene.

TABLE 6.

Nucleotide polymorphism observed among the 18 study isolates

| Gene | Fragment size (bp) | No. of variable sites (%)

|

No. of substitutions (%)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singleton | Informative | Total | Synonymous | Nonsynonymous | Total | ||

| rpoB | 940 | 34 (3.6) | 48 (5.1) | 82 (8.7) | 82 (8.7) | 5 (0.5) | 87 (9.3) |

| gyrA | 383 | 15 (3.9) | 17 (4.4) | 32 (8.4) | 33 (8.6) | 1 (0.3) | 34 (8.9) |

| gapDH | 573 | 26 (4.5) | 13 (2.3) | 39 (6.8) | 38 (6.6) | 3 (0.5) | 41 (7.2) |

| bla | 870, 873, or 876 | 64 (7.3) | 139 (15.9) | 203 (23.2) | 158 (18.0) | 52 (5.9) | 210 (24.0) |

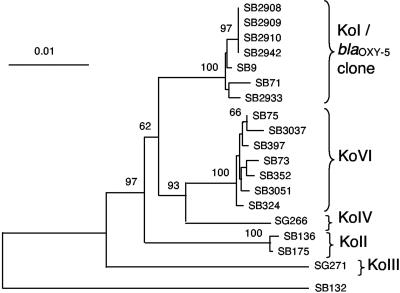

The neighbor-joining trees obtained based on rpoB, gyrA, and gapDH were very similar. Therefore, we concatenated the three genes to estimate more robustly the phylogeny of the strains (Fig. 2). A very close agreement with the phylogeny previously obtained on the basis of the β-lactamase gene (Fig. 1) was observed. Strains with blaOXY-2, blaOXY-3, blaOXY-4, and blaOXY-6 genes clustered into four separate branches, each corresponding to their β-lactamase group. These four branches clearly represent distinct phylogenetic groups. For each gene, the nucleotide divergence within groups was much lower than that observed among groups (Table 7). The isolates harboring blaOXY-1 and blaOXY-5 β-lactamase genes were very close (Fig. 2 and Table 7). Therefore, we consider blaOXY-5-harboring strains as belonging to phylogenetic group KoI (see Discussion). Groups KoII and KoIII appeared to be the most external lineages, as observed with the blaOXY gene.

FIG. 2.

Phylogeny obtained based on 1,896 nt positions from the three housekeeping genes rpoB, gyrA, and gapDH. The neighbor-joining tree was rooted using K. pneumoniae type strain SB132 (= ATCC 13883T). Values at the nodes correspond to bootstrap values obtained after 1,000 replicates. Five branches of K. oxytoca are distinguished, corresponding to phylogenetic groups KoI to KoVI. blaOXY-5-harboring strains fall into the KoI branch.

TABLE 7.

Percent average rpoB, gyrA, and gapDH nucleotide sequence divergence within and among the five K. oxytoca phylogenetic groups and clone blaOXY-5

| Group or clone | Avg % divergence from nucleotide sequence

|

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KoI

|

KoII

|

KoIII

|

KoIV

|

blaOXY-5 clone

|

KoVI

|

|||||||||||||

| rpoB | gyrA | gapDH | rpoB | gyrA | gapDH | rpoB | gyrA | gapDH | rpoB | gyrA | gapDH | rpoB | gyrA | gapDH | rpoB | gyrA | gapDH | |

| KoI | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0 | 3.09 | 3.2 | 1.92 | 4.25 | 4.96 | 4.36 | 3.2 | 3.65 | 0.7 | 0.49 | 0.52 | 0.00 | 3.04 | 2.68 | 0.67 |

| KoII | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0 | 4.15 | 5.09 | 5.4 | 4.15 | 3.26 | 2.44 | 3 | 3.13 | 1.92 | 3.6 | 2.68 | 2.24 | |||

| KoIII | NAa | NA | NA | 4.36 | 5.48 | 4.88 | 4.32 | 4.7 | 4.36 | 4.32 | 4.51 | 4.51 | ||||||

| KoIV | NA | NA | NA | 2.83 | 3.65 | 0.7 | 2.96 | 1.3 | 0.67 | |||||||||

| blaOXY-5 clone | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 3.1 | 2.42 | 0.67 | ||||||||||||

| KoVI | 0.4 | 0.13 | 0.1 | |||||||||||||||

NA, not applicable (only one sequence per group).

The nearly complete (1,454-bp) 16S rRNA gene sequence was determined for the two KoI and the two KoII reference strains and for two blaOXY-5-harboring and three blaOXY-6-harboring strains (Table 1). Excluding 12 positions showing within-strain heterogeneity among gene copies (5), the 16S rRNA sequences of blaOXY-5- and blaOXY-6-harboring strains were completely identical to that of KoI, with the exception of two substitutions for one blaOXY-6-harboring strain (SB3051; data not shown).

Ancient presence of the chromosomal β-lactamase gene in K. oxytoca.

In the absence of bacterial fossils, the molecular clock hypothesis, according to which the rate of synonymous substitution at synonymous sites (Ks) along evolutionary lineages is roughly constant over time, is a way to estimate the timing of evolutionary events. In order to estimate the time since divergence of the K. oxytoca phylogenetic groups, we used genes rpoB and gyrA, both of which showed clock-like behavior. To calibrate the Ks values of rpoB and gyrA, we used two extreme estimations for the time of divergence between E. coli and Salmonella enterica, 30 and 140 million years (23, 25, 27). The Ks of rpoB between E. coli and S. enterica is 0.223, whereas the Ks for gyrA is 0.367. Table 8 gives the Ks values observed among K. oxytoca groups. Using the 30-million-year calibration, rpoB and gyrA Ks values indicate a split between KoI and KoII 15 and 11 million years ago, respectively, whereas the two groups with the greatest difference, KoIII and KoIV, would have separated 23 or 18 million years ago, respectively. The divergence of the blaOXY-5 strains from KoI would be as recent as 3 to 2 million years. Using the 140-million-year calibration, the separation of the KoIII and KoIV groups would be estimated to be as old as 109 or 84 million years, based on rpoB and gyrA.

TABLE 8.

Average numbers of synonymous substitutions per synonymous site (Ks values) among the five K. oxytoca phylogenetic groups and clone blaOXY-5a

| Group or clone | Avg Ks value

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KoI | KoII | KoIII | KoIV | Clone blaOXY-5 | KoVI | |

| KoI | 0.114 | 0.17 | 0.128 | 0.02 | 0.12 | |

| KoII | 0.135 | 0.157 | 0.156 | 0.111 | 0.133 | |

| KoIII | 0.21 | 0.214 | 0.175 | 0.173 | 0.171 | |

| KoIV | 0.143 | 0.126 | 0.22 | 0.113 | 0.117 | |

| Clone blaOXY-5 | 0.022 | 0.132 | 0.199 | 0.143 | 0.123 | |

| KoVI | 0.112 | 0.128 | 0.188 | 0.045 | 0.101 | |

Data computed from gene rpoB (above diagonal) and gyrA (below diagonal).

DISCUSSION

The phylogenetic analysis of all major OXY β-lactamase gene variants exhibited six distinct branches. Although the distinction of branches as new groups rather than new variants within existing groups is partly a matter of arbitrary choice, we decided to consider the two new branches as new groups, as it should stimulate their epidemiological follow-up. In addition, we showed that is was possible to defined group-specific PCR primers, which underlines the distinctness of these groups and provides tools for their epidemiological investigation. The individualization of OXY-5 and OXY-6 β-lactamases as two groups, each distinct from OXY-1, is supported by signature amino acids (Table 3), by mean amino acid divergence (Table 4), and by phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 1). The five blaOXY-5-harboring isolates were collected in two Italian cities, in Switzerland, and in The Netherlands, whereas the seven blaOXY-6-harboring isolates came from France, Germany, South Africa, and Ukraine. Both groups therefore appear geographically widespread, although they together represented only 6.5% (12/183) of K. oxytoca clinical isolates.

Nucleotide variation at three housekeeping genes and at the 16S rRNA gene was in very close agreement with the phylogeny disclosed for the β-lactamase gene. The results confirm that strains harboring blaOXY-1, blaOXY-2, and blaOXY-3 genes fall into three distinct phylogenetic groups, in agreement with the findings of Granier et al. (14, 15). In addition, our data demonstrate that blaOXY-4-harboring strain SG266 represents still another branch, a result that was not fully established based on shorter portions of the rpoB and 16S rRNA gene sequences (14). In contrast to the β-lactamase data, it was not clear if blaOXY-5-harboring strains represent a distinct phylogenetic branch. In fact, although they tend to group together based on housekeeping genes, these strains fell within phylogenetic group KoI. We interpret this apparent discrepancy between the bla and housekeeping genes by hypothesizing a relatively recent emergence from KoI of the evolutionary lineage corresponding to blaOXY-5-harboring strains. Due to a higher rate of nucleotide substitution (Table 6), variation in the β-lactamase gene is expected to reveal lineage splits more quickly than variation at housekeeping genes. Thus, blaOXY-5-harboring strains can be considered as an emerging clone, individualized from KoI only by fast-evolving genetic markers. We propose to refer to the blaOXY-5-harboring strains as the blaOXY-5 clone or lineage and to the five phylogenetic groups as KoI to KoIV and KoVI, in continuation of our initial nomenclature (4). These names clearly mark the difference between phylogenetic groups and β-lactamase groups, which should be less confusing than the OXY or oxy group denomination (14, 15).

The phylogenetic agreement between bla and housekeeping genes was not only true for the classification of strains within groups but also appeared to be the case for the hierarchical relationships among groups. Because the phylogeny of the β-lactamase gene is concordant with the phylogenies based on housekeeping genes, by far the most likely evolutionary origin of the six OXY β-lactamase groups is diversification from a common ancestor, along with the evolutionary divergence of the phylogenetic groups (17). The ancestry of the set of K. oxytoca strains can be conservatively estimated at several tens of millions of years, based on the molecular clock hypothesis. Notably, estimations based on rpoB and on gyrA were in close agreement. Although the constancy of the nucleotide substitution rate across lineages is a rough statement and should be taken with caution (24), our estimations show beyond doubt an ancient diversification of the OXY groups of β-lactamase, predating by far antibiotic usage in clinical practice. Adding the fact that essentially there is a lack of evolution of the resistance phenotype, the pattern of diversification of the OXY family of β-lactamases appears to conform to the long-term neutral evolutionary scenario that was also described for the evolutionary diversification of the major variants of other families of β-lactamases, such as AmpC or SHV (2, 18).

Acknowledgments

We thank M.-H. Nicolas-Chanoine for kindly providing strains SG271 and SG266 and N. Kozyrovska for strain VN13 (SB3037).

REFERENCES

- 1.Arakawa, Y., M. Ohta, N. Kido, M. Mori, H. Ito, T. Komatsu, Y. Fujii, and N. Kato. 1989. Chromosomal β-lactamase of Klebsiella oxytoca, a new class A enzyme that hydrolyzes broad-spectrum β-lactam antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 33:63-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barlow, M., and B. G. Hall. 2002. Origin and evolution of the AmpC β-lactamases of Citrobacter freundii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1190-1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brisse, S., D. Milatovic, A. C. Fluit, J. Verhoef, and F. J. Schmitz. 2000. Epidemiology of quinolone resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Klebsiella oxytoca in Europe. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 19:64-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brisse, S., and J. Verhoef. 2001. Phylogenetic diversity of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Klebsiella oxytoca clinical isolates revealed by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA, gyrA and parC genes sequencing and automated ribotyping. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:915-924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cilia, V., B. Lafay, and R. Christen. 1996. Sequence heterogeneities among 16S ribosomal RNA sequences, and their effect on phylogenetic analyses at the species level. Mol. Biol. Evol. 13:451-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Comité de l'Antibiogramme de la Société Française de Microbiologie. 2004. Communiqué 2004. Société Française de Microbiologie, Paris, France.

- 7.Emanuel, E. L., J. Gagnon, and S. G. Waley. 1986. Structural and kinetic studies on beta-lactamase K1 from Klebsiella aerogenes. Biochem. J. 234:343-347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fournier, B., G. Arlet, P. H. Lagrange, and A. Philippon. 1994. Klebsiella oxytoca: resistance to aztreonam by overproduction of the chromosomally encoded beta-lactamase. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 116:31-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fournier, B., A. Gravel, D. C. Hooper, and P. H. Roy. 1999. Strength and regulation of the different promoters for chromosomal β-lactamases of Klebsiella oxytoca. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:850-855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fournier, B., P. H. Lagrange, and A. Philippon. 1996. β-Lactamase gene promoters of 71 clinical strains of Klebsiella oxytoca. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:460-463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fournier, B., C. Y. Lu, P. H. Lagrange, R. Krishnamoorthy, and A. Philippon. 1995. Point mutation in the Pribnow box, the molecular basis of β-lactamase overproduction in Klebsiella oxytoca. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1365-1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fournier, B., P. H. Roy, P. H. Lagrange, and A. Philippon. 1996. Chromosomal β-lactamase genes of Klebsiella oxytoca are divided into two main groups, blaOXY-1 and blaOXY-2. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:454-459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gheorghiu, R., M. Yuan, L. M. Hall, and D. M. Livermore. 1997. Bases of variation in resistance to beta-lactams in Klebsiella oxytoca isolates hyperproducing K1 beta-lactamase. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 40:533-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Granier, S. A., V. Leflon-Guibout, F. W. Goldstein, and M. H. Nicolas-Chanoine. 2003. New Klebsiella oxytoca β-lactamase genes blaOXY-3 and blaOXY-4 and a third genetic group of K. oxytoca based on blaOXY-3. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2922-2928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Granier, S. A., L. Plaisance, V. Leflon-Guibout, E. Lagier, S. Morand, F. W. Goldstein, and M. H. Nicolas-Chanoine. 2003. Recognition of two genetic groups in the Klebsiella oxytoca taxon on the basis of chromosomal beta-lactamase and housekeeping gene sequences as well as ERIC-1R PCR typing. Int. J Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53:661-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15a.Granier, S. A., V. Leflon-Guibout, M.-H. Nicolas-Chanoine, K. Bush, and F. W. Goldstein. 2002. The extended-spectrum K1 β-lactamase from Klebisiella oxytoca SC 10,436 is a member of the blaOXY-2 family of chromosomal Klebsiella enzymes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2056-2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grimont, F., P. A. D. Grimont, and C. Richard. 1992. The genus Klebsiella, p. 2775-2796. In A. Balows, H. G. Trüper, M. Dworkin, W. Harder, and K.-H. Schleifer (ed.), The prokaryotes, vol. 3. Springer-Verlag, New York, N.Y. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guttman, D. S., and D. E. Dykhuizen. 1994. Clonal divergence in Escherichia coli as a result of recombination, not mutation. Science 266:1380-1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haeggman, S., S. Lofdahl, A. Paauw, J. Verhoef, and S. Brisse. 2004. Diversity and evolution of the class A chromosomal β-lactamase gene in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:2400-2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hart, C. A. 1993. Klebsiellae and neonates. J. Hosp. Infect 23:83-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joris, B., F. De Meester, M. Galleni, J. M. Frere, and J. Van Beeumen. 1987. The K1 beta-lactamase of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Biochem. J. 243:561-567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Livermore, D. M. 1995. β-Lactamases in laboratory and clinical resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 8:557-584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Livermore, D. M., and M. Yuan. 1996. Antibiotic resistance and production of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases amongst Klebsiella spp. from intensive care units in Europe. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 38:409-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nelson, K., T. S. Whittam, and R. K. Selander. 1991. Nucleotide polymorphism and evolution in the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene (gapA) in natural populations of Salmonella and Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:6667-6671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ochman, H., S. Elwyn, and N. A. Moran. 1999. Calibrating bacterial evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:12638-12643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ochman, H., and A. C. Wilson. 1987. Evolution in bacteria: evidence for a universal substitution rate in cellular genomes. J. Mol. Evol. 26:74-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohsuka, S., Y. Arakawa, T. Horii, H. Ito, and M. Ohta. 1995. Effect of pH on activities of novel β-lactamases and β-lactamase inhibitors against these β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1856-1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pesole, G., M. P. Bozzetti, C. Lanave, G. Preparata, and C. Saccone. 1991. Glutamine synthetase gene evolution: a good molecular clock. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:522-526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Podschun, R., and U. Ullmann. 1998. Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:589-603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rozas, J., and R. Rozas. 1999. DnaSP version 3: an integrated program for molecular population genetics and molecular evolution analysis. Bioinformatics 15:174-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swofford, D. L. 1998. PAUP*: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (and other methods), 4.0b10 ed. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Mass.

- 31.Wu, S. W., K. Dornbusch, and G. Kronvall. 1999. Genetic characterization of resistance to extended-spectrum β-lactams in Klebsiella oxytoca isolates recovered from patients with septicemia at hospitals in the Stockholm area. Antimicrob. Agnets Chemother. 43:1294-1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]