Using an unbiased, high-throughput CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis screen, the authors identify PRDM1 as a regulator of NKT-cell (NKT) functional fitness. PRDM1 knockdown in CAR NKTs enhances their anti-neuroblastoma activity, suggesting an approach to improve the efficacy of NKT-based cancer immunotherapies.

Abstract

Natural killer T cells (NKTs) are a promising platform for cancer immunotherapy, but few genes involved in the regulation of NKT therapeutic activity have been identified. To find regulators of NKT functional fitness, we developed a CRISPR/Cas9-based mutagenesis screen that uses a guide RNA (gRNA) library targeting 1,118 immune-related genes. Unmodified NKTs and NKTs expressing a GD2-specific chimeric antigen receptor (GD2.CAR) were transduced with the gRNA library and exposed to CD1d+ leukemia or CD1d−GD2+ neuroblastoma cells, respectively, over six challenge cycles in vitro. Quantification of gRNA abundance revealed enrichment of PRDM1-specific gRNAs in both NKTs and GD2.CAR NKTs, a result that was validated through targeted PRDM1 knockout. Transcriptional, phenotypic, and functional analyses demonstrated that CAR NKTs with PRDM1 knockout underwent central memory–like differentiation and resisted exhaustion. However, these cells downregulated the cytotoxic mediator granzyme B and showed reduced in vitro cytotoxicity and only moderate in vivo antitumor activity in a xenogeneic neuroblastoma model. In contrast, short hairpin RNA-mediated PRDM1 knockdown preserved effector function while promoting central memory differentiation, resulting in GD2.CAR NKTs with potent in vivo antitumor activity. Thus, we have identified PRDM1 as a regulator of NKT memory differentiation and effector function that can be exploited to improve the efficacy of NKT-based cancer immunotherapies.

Introduction

Vα24-invariant natural killer T cells (NKTs) are an evolutionarily conserved subset of innate-like T lymphocytes that express the invariant T-cell receptor α-chain Vα24–Jα18 and recognize glycolipids presented by the monomorphic MHC-like molecule CD1d (1). NKTs are characterized by innate antitumor properties, including the ability to localize to tumor sites in response to tumor-derived chemokines, to eliminate CD1d+ tumor-associated macrophages in the tumor microenvironment, to convert myeloid-derived suppressor cells into stimulatory antigen-presenting cells, and to transactivate T- and NK-cell antitumor responses (2–8). In patients, the presence of functional tumor-infiltrating and circulating NKTs correlates positively with clinical outcomes in several types of cancer (3, 9, 10). These attributes make NKTs uniquely suited for use as a cancer immunotherapy platform.

To generate NKTs for therapeutic use, we have developed protocols to isolate, ex vivo expand to clinical scale, and transduce NKTs with tumor antigen–specific chimeric antigen receptors (CAR). Using this technology, we initiated a phase I trial of autologous NKTs expressing a GD2 disialoganglioside-specific CAR (GD2.CAR) with the cytokine IL15 in children with relapsed/refractory neuroblastoma (NCT03294954). Interim results from this trial have shown that GD2.CAR NKTs are well-tolerated and mediate objective responses in heavily pretreated patients with neuroblastoma (11). Correlative studies have revealed that expression of the central memory marker CD62L in patient infusion products is associated with CAR NKT expansion, persistence, and ability to mediate antitumor responses. These observations are consistent with previous preclinical results from our group showing that CD62L+ central memory–like NKTs are required for in vitro expansion, in vivo persistence, and tumor control in xenogeneic mouse models (11). In follow-up preclinical studies, we identified lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1 (LEF1), a top-overexpressed gene in CD62L+ NKTs, as an additional mediator of the NKT central memory program (12). Additionally, using gene expression data from GD2.CAR NKTs isolated from the peripheral blood of patients on our trial, we identified BTG antiproliferation factor 1 (BTG1) as a negative regulator of central memory differentiation and a mediator of NKT hyporesponsiveness and exhaustion (13).

Identifying mediators and regulators of NKT central memory differentiation and functional fitness like CD62L, LEF1, and BTG1 is crucial to the development of more effective NKT-based cancer immunotherapies. CRISPR/Cas9-based mutagenesis screening is a powerful tool that can be used to identify such genes in a high-throughput, unbiased manner. For example, this approach has been used in T cells to find genes that encode regulators of antitumor activity (14), cytokine response (15), in vivo CD8+ T-cell metabolic reprogramming in the tumor microenvironment (16), and CAR T-cell effector function (14). In this study, we describe a CRISPR/Cas9-based platform that we used to identify genes that regulate NKT/CAR NKT central memory differentiation in an unbiased manner. The screen used an in vitro serial tumor challenge assay to mimic chronic antigen exposure and induce exhaustion/terminal differentiation in NKTs transduced with a library of guide RNAs (gRNA), thereby filtering for genes involved in NKT expansion and persistence.

Using this screening strategy, we identified PRDM1 as a gene that encodes a negative regulator of NKT and CAR NKT exhaustion and terminal differentiation. We showed that in NKTs and CAR NKTs, PRDM1 knockout (KO) preserved the central memory phenotype and enhanced expansion after serial tumor challenge but led to decreased cytotoxic effector function and limited antitumor efficacy. However, reducing PRDM1 expression via short hairpin RNA (shRNA) knockdown (KD) allowed for maintenance of both central memory cells and potent effector function, resulting in NKTs and CAR NKTs that persisted and mediated effective antitumor activity in a xenograft mouse model of neuroblastoma.

Thus, using a CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis screen, we identified a key role for PRDM1 in regulation of NKT and CAR NKT central memory differentiation and effector function. This study represents the first such exploration of high-throughput, unbiased screening for genes that regulate NKT cell function and has the potential to advance the development of next-generation NKT-based cancer immunotherapies.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and culture conditions

The 293T cell line (RRID: CVCL_0063) was purchased from the ATCC. The CHLA255 neuroblastoma cell line (17) and the Jurkat J32 T-cell leukemia cell line (18) were obtained from Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. CHLA255 and J32 cells with GFP and luciferase expression were generated by transducing parental CHLA255 or J32 cells with a GFP.FFLuc retroviral plasmid (plasmid pSFG-GFP-effluc from Dr. Brian A Rabinovich, see “Generation of retroviral constructs and production of retroviral supernatants” for retroviral supernatant production). CHLA255 and 293T cells were cultured in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco's medium (Cytiva). All cell culture medium was supplemented with 2 mmol/L Glutamax-I (Gibco) and 10% FBS (Gibco) except CHLA255 medium, which was supplemented with 20% FBS. Cell lines with low passage numbers were thawed and used within 10 passages. Cell line authentication was performed using short tandem repeat fingerprinting at MD Anderson Cancer Center within 1 year of use, and cell lines were checked for Mycoplasma contamination every 2 months using Lonza MycoAlert Kit (LT07-318).

Generation of retroviral constructs and production of retroviral supernatants

Retroviral plasmid encoding the GD2.CAR was generated as previously described (19). The construct included the following components: a single-chain variable fragment from the GD2-specific antibody 14G2a connected via a CD8a hinge and transmembrane domain, followed by the signaling endodomain of CD28 fused with the CD3ζ signaling chain. To generate the GD2.CAR PRDM1 KD retroviral plasmid (PRDM1 KD), the DSIR tool (http://biodev.cea.fr/DSIR/) was first used to select the PRDM1-targeting shRNA sequence (ATTACAATTCACCGTAGGG) and a scrambled shRNA control (Scr) sequence (AAATGTACTGCGCGTGGAGAC), which were then cloned by overlapping PCR and inserted individually into the miR-155 backbone to generate artificial microRNAs (amiR). Next, cassettes encoding the PRDM1-targeting amiR or scrambled amiR sequences were inserted into the GD2–CD28–CD3ζ backbone downstream of the GD2.CAR sequence to generate the PRDM1 KD or Scr retroviral constructs.

Retroviral supernatants were produced by transfecting 293T cells using GeneJuice (EMD Millipore, 70967) according to the manufacturer’s protocol with a combination of the relevant retroviral plasmid (GFP.FFLuc, GD2.CAR only, PRDM1 KD, or Scr control plasmid), the RDF plasmid [a gift from Dr. Mary Collins, Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)] encoding the RD114 envelope protein (20), and the PeqPam3 plasmid (a gift from Dr. Elio Vanin, BCM) encoding the Moloney murine leukemia virus gag–pol fusion. Retroviral supernatants were then transduced into NKT cells following the protocol described in “NKT isolation, transduction, expansion, and electroporation.”

Generation of lentiviral gRNA library and lentiviral constructs/supernatants

We selected 1,118 immune-related genes to target in the gRNA library, with some chosen from the 10× Genomics database, some identified through RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis of expanded human NKTs in our laboratory (11), and some from a gene list provided by Immunai, Inc. A total of 5,638 gRNA sequences were incorporated into the final library, including five gRNAs for each gene and 48 nontargeting gRNA controls, all generated using the Sanjana Lab tool: http://guides.sanjanalab.org/#/. Supplementary Table S1 includes the list of immune-related genes analyzed and the gRNA sequences. The gRNA library pool was synthesized by Twist Biosciences and PCR-amplified with primers “GGATCTCGACGGTATCGGTTCCCGAGGGGACCCAGAGAGG” and “CCCCTTTTCTTTTAAAAGTTCGCCAAGCTTAAAAAAGCAC.” This PCR product was purified by gel electrophoresis and cloned into a HpaI-digested pCDH.EF1α.P2A.RFP plasmid (Systems Bioscience) using NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly (NEB) to generate the RFP-gRNA library. The GD2.CAR-gRNA library contains the same gRNAs as the RFP-gRNA library (Supplementary Table S1) and was generated by first digesting pCDH.EF1α.P2A.RFP with DraIII and SalI and then PCR-amplifying EF1α with primers “ATGGAGTTTCCCCACACTGAGTGGGTGGAGACTGAAGTTA” and “CAGCTCAGCCCAAACTCCATGGTGGCCGGCCCTAGATCACGACACC” and the GD2.CAR with “GGTGTCGTGATCTAGGGCCGGCCACCATGGAGTTTGGGCTGAGCTG” and “ATCCAGAGGTTGATTGTCGACTTAGCGAGGGGGCAGGGCC.” The digested backbone and two-part insert were assembled in a three-piece reaction via NEBuilder HiFi, effectively replacing the P2A-RFP gene from pCDH.EF1α.p2A.RFP with the GD2.CAR. This pCDH.EF1α.GD2-CAR plasmid was then digested with HpaI, and the gRNA pool was inserted via NEBuilder assembly. The libraries were shown to have comparable gRNA frequency distributions as determined by next-generation sequencing (NGS) performed as described in “Sequencing library preparation.” Lentiviral constructs for PRDM1 KO, B2M KO, and other evaluated gRNA hits (Fig. 1) were generated via the same protocol used for the lentiviral gRNA library. All relevant gRNA sequences are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

Figure 1.

In vitro CRISPR/Cas9 screens identify PRDM1 as a negative regulator of expansion in NKTs and GD2.CAR NKTs. A, CRISPR/Cas9/tumor challenge screening protocol. NKT cells are transduced with the lentiviral vector gRNA library coexpressing RFP or GD2.CAR. The RFP-NKT library or GD2.CAR NKT library is then challenged with CD1d+ Jurkat cells or GD2+ CHLA255 neuroblastoma cells, respectively, every 3 to 4 days for a total of six rounds, and cells are harvested at the end of the sixth tumor challenge round. Cells are processed for NGS, and relative frequencies of gRNA sequences are compared with frequencies in prechallenge NKTs. B, Volcano plot showing expression FC vs. P value for enriched gRNA sequence candidates identified in NKT gRNA library screen. Log2 FC from prechallenge cell numbers vs. after six rounds of tumor challenge; the dotted line shows P = 0.05. gRNA candidates shown were validated individually. N = 4. C, NKTs with individual PRDM1 KO or B2M KO were challenged with CD1d+ Jurkat cells over six rounds. RFP+ NKT numbers were determined at the end of each challenge cycle by counting and FACS. Shown are RFP+ NKT FC at the end of each cycle for a representative donor and paired overall RFP+ NKT FC in B2M KO vs. PRDM1 KO cells from four donors; B2M average: FC 15.4, SD 17.7; PRDM1 average: FC 3829.2, SD 2868.5; P = 0.0011. D, Volcano plot showing expression FC vs. P value for genes identified in GD2.CAR NKT library screen. Log2 FC from prechallenge cell numbers vs. after six rounds of tumor challenge; the dotted line shows P = 0.05. N = 4. E, NKTs with individual PRDM1 KO or B2M KO were challenged with GD2+ CHLA255 cells over six rounds. GD2.CAR+ NKT numbers were determined at the end of each challenge cycle by counting and FACS. Shown are GD2.CAR+ NKT FC at the end of each cycle for a representative donor and paired overall GD2.CAR+ NKT FC in B2M KO vs. PRDM1 KO cells from four donors; B2M average: FC 10.7, SD = 5.8; PRDM1 average: FC 228.3, SD = 80.7; P = 0.0042. F, GD2.CAR expression ratio in PRDM1 KO NKT group prior to and after six rounds of tumor challenge. N = 8; before cycle 1 average: 30.63, SD = 13.89; after cycle 6 average: 88.11, SD = 9.69; P = 0.0001.

Lentiviral supernatants were generated from 293T cells using GeneJuice to transfect the cells with the relevant lentiviral construct [lentiviral library, individual gene KO constructs (Supplementary Table S3)], pMD2.G (Addgene, 12259, RRID: Addgene_12259), and Pax2 (Addgene, 35002, RRID: Addgene_117398). To enhance transduction efficiency, lentiviral supernatants were concentrated by ultracentrifugation using an Optima XE-90 ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter) at 28,200 rpm for 2 hours at 4°C. Supernatants were aspirated, and pellets were reconstituted in 200 μL complete RPMI, comprising RPMI (HyClone, SH30096.01) supplemented with 2 mmol/L GlutaMax-I (Life Technologies, 35050061) and 10% FBS (HyClone, SH30071.01), and stored at −80°C. Lentiviral supernatants were then transduced into invariant natural killer T cells (iNKT) following the protocol described in “NKT isolation, transduction, expansion, and electroporation.”

NKT isolation, transduction, expansion, and electroporation

Peripheral blood of healthy donors was purchased from Gulf Coast Regional Blood Center. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from buffy coats by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation (GE Healthcare). NKTs were purified using anti-iNKT microbeads according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-094-842), and the negative PBMC fraction was irradiated (40 Gy) and aliquoted at 40 × 106 cells/mL for each donor. Approximately 1 × 106 NKTs were stimulated with an aliquot of 5 × 106 autologous PBMCs pulsed with α-galactosylceramide (αGalCer; 100 ng/mL; Avanti Polar Lipids, 86700P-1mg) per well in a 24-well plate. The culture was supplemented every other day with recombinant IL2 (200 U/mL; NCI/TECIN, 23-6019) in complete RPMI. NKTs were expanded for 10 to 12 days and then restimulated at a 1:5 NKT to autologous PBMC ratio in a 6-well G-Rex plate.

For retroviral transduction, 24-well, non–tissue culture–treated plates were coated with RetroNectin (Takara Bio, T100B) overnight. On day two after restimulation, RetroNectin-coated plates were washed, inoculated with 1 mL of retroviral supernatant (GFP.FFLuc, GD2.CAR only, PRDM1 KD, or Scr control plasmid), and spun for 60 minutes at 3,000 g. Viral supernatant was then removed, and 5 × 105 stimulated NKTs were added per well to complete RPMI media and 200 U/mL IL2. Cells were removed from the plate after 48 hours, washed, and transferred to a 6-well G-Rex plate in complete RPMI with IL2 for continued expansion. NKT number was determined using a Cellometer Auto 2000 cell viability counter (Nexcelom), and transduction efficiency was determined by flow cytometry evaluation of CAR expression at least 5 days after transduction.

For lentiviral transduction and electroporation [lentiviral library, individual gene KO constructs (Supplementary Table S3)], 2 days after restimulation, NKTs were washed, resuspended, and added at 5 × 105 per well to a 24-well tissue culture–treated plate with complete RPMI and 200 U/mL IL2. Then, 50 μL of concentrated lentiviral supernatant was added to each well. Twenty-four hours after lentiviral transduction, the cells were collected and washed once in PBS before proceeding to Cas9 electroporation (5 μg per 1 × 106 cells, TrueCut Cas9 Protein v2, Thermo Fisher Scientific) using P3 Primary Cell 4D-Nucleofector X Kit L (Lonza) following the manufacturer’s protocol with pulse code CA137. Cells were cultured in complete RPMI with IL2 supplementation for an additional 7 days before further experiments were performed. Transduction efficiency was determined by flow cytometry evaluation of CAR expression at least 5 days after transduction, and B2M KO efficiency was determined by flow cytometry evaluation of HLA expression at least 4 days after electroporation.

In vitro serial tumor challenge assay

This assay was used in the context of the CRISPR/Cas9 tumor challenge screen (Fig. 1A) as well as for subsequent functional assessment of NKTs with individual gene KD/KO. NKTs transduced with either the RFP-gRNA or GD2.CAR-gRNA library or PRDM1 or individual gRNA lentiviral plasmids (Supplementary Table S3) and electroporated with Cas9 were cultured for an additional 7 days after electroporation. The cells were then cocultured 1:1 with GFPhighCD1d+ J32 cells or GFPhighCHLA255 cells in the presence of IL2 (50 U/mL) and αGalCer (100 ng/mL for J32 cells) for six cycles of 3 to 4 days. At the end of each cycle, the cell mixture was stained for flow cytometric analysis of Vα24-Jα18 and GD2.CAR expression (see “Flow cytometry and intracellular cytokine staining”), and cell numbers were determined using a Cellometer Auto 2000 cell viability counter. Fresh J32 cells and αGalCer or CHLA255 cells were added to the culture based on NKT numbers to reestablish the 1:1 effector-to-target ratio at the start of each cycle. Where noted in text/figures, NKT cells were harvested after indicated cycle numbers of serial challenge assay (e.g., after cycle 6) for downstream assessment.

Sequencing library preparation

Genomic DNA was extracted from NKTs transduced with either the RFP-gRNA or GD2.CAR-gRNA lentiviral library using DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen). qPCR was performed using KAPA SYBR FAST qPCR Master Mix (Sigma-Aldrich) on C1000 Touch Thermal Cycler with CFX96 Optical Reaction Module (Bio-Rad) using universal adapter primers (forward primer: ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTGGCTTTATATATCTTGTGGAAAGGACGAAACACC; reverse primer: GTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCCCGACTCGGTGCCACTTTTTCAA). Sample amplification curves were monitored, and PCR was repeated while ensuring that cycle number remained in the exponential phase. Second rounds of both qPCR and PCR were performed using the initial PCR product and sample-specific multiplex barcoded primers. Bands were gel-purified using Zymoclean Gel DNA Recovery Kit (Zymo Research) and quantified using a Qubit 4 fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples were pooled at equimolar amounts and underwent dual-indexed sequencing of 2 × 150 bp reads on an Illumina HiSeq instrument with custom sequencing primers (Supplementary Table S4). NKT cells from four donors were used in each screen.

Library screen data analysis

The bioinformatics tool Model-based Analysis of Genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout (21) was used to process screening results. Raw reads from paired-end sequencing files were mapped against gRNA sequences (five gRNAs per target gene) using the Model-based Analysis of Genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout count command. A count matrix consisting of the read counts of all samples was generated. We performed DESeq2 (version 1.28.1; 22) analyses to identify differences in the relative frequency of gRNAs between RFP NKTs and CAR NKTs for prechallenge cells and after four or six rounds of serial tumor challenge. gRNA sequences were considered significantly enriched if the log2 fold change (FC) was ≥1 with a P value < 0.05 or significantly depleted if the log2 FC was ≤–1 with P value < 0.05.

In vitro real-time cellular impedance monitoring

We used the xCELLigence Real-Time Cell Analysis system (ACEA Biosciences Inc.) to longitudinally evaluate GD2.CAR NKT cytotoxicity against CHLA255 cells. CHLA255 cells (2 × 104) were seeded into E-Plate VIEW 96 PET microwell plates, and GD2.CAR NKTs or nontransduced NKTs were added 24 hours later to the wells to achieve the desired effector-to-target ratios. Electrical impedance was monitored in 60-minute intervals over 3 days, and cytotoxicity was assessed by calculating the normalized cell index and percent cytolysis.

Confirmation of gRNA KO

GD2.CAR NKTs transduced with the PRDM1 gRNA were harvested 7 days after Cas9 electroporation, and CD3+iNKT+CAR+ cells were sorted using FACSAria III Cell Sorter (BD Biosciences). Genomic DNA was isolated from both PRDM1 KO NKTs and wild-type (WT) NKTs using DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen). The fragment of the PRDM1 gene encoding the gRNA target was amplified (KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix PCR Kit, 50-196-5299) using forward primer “CAGTAGCATCGCCCATTTGC” and reverse primer “GGGGCAGAACCGACATTACT.” PCR products were purified using DNA Clean and Concentrator Kit (Zymo Research), and sequences were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. PRDM1 mutagenesis was evaluated using Inference of CRISPR Edits (Synthego, Inc.).

Flow cytometry and intracellular cytokine staining

NKT phenotype was assessed using fluorescently conjugated mAbs for CD3 (UCHT1, BD Biosciences, RRID: AB_2876783), Vα24-Jα18 (6B11, BD Biosciences, RRID: AB_3244813), CD4 (SK3, BD Biosciences, RRID: AB_2833103), CD62L (DREG-56, BD Biosciences, RRID: AB_2534951), PD-1 (J105, Invitrogen, RRID: AB_647188), TIM-3 (7D3, BD Biosciences, RRID: AB_2722547), LAG3 (3DS223H, Invitrogen, RRID: AB_2896003), CD39 (A1, BioLegend, RRID: AB_2917857), and TIGIT (MBSA43, Invitrogen, RRID: AB_10854428). GD2.CAR expression in transduced NKTs was detected with the 14G2a anti-idiotype 1A7 mAb [purified from 1A7 mouse hybridoma (ATCC, HB-11786)], which was custom-conjugated to Alexa Fluor 647 by BioLegend. B lymphocyte–induced maturation protein-1 (BLIMP1) staining was performed using the eBioscience Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer set (Invitrogen, 00-5523-00) with a mAb for BLIMP1 (646702, R&D systems, RRID: AB_11130084). Cytokine staining was performed on expanded NKTs that were stimulated using phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; 50 ng/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, P1585) and ionomycin (500 ng/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, I9657) in the presence of GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences, 555029) and GolgiStop (BD Biosciences, 554724). After a 4-hour incubation, NKTs were washed then stained with eFluor 780 fixable viability dye (eBioscience, 65-0865-18) for 15 minutes at room temperature. Cells were then washed and stained for surface expression of GD2.CAR, CD4, and Vα24-Jα18 for 15 minutes at room temperature. Cells were then fixed and permeabilized using the eBioscience Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer set following the manufacturer’s protocol. Permeabilized cells were stained with antibodies to detect TNFα (MAb11, BioLegend, RRID: AB_398566), IL2 (MQ1-17H12, BD Biosciences, RRID: AB_3099372), and IFNγ (B27, BD Biosciences, RRID: AB_396760). Granzyme B staining was performed 5 days after GD2.CAR NKTs were stimulated 1:1 with CHLA255 cells. NKTs were washed then stained with eFluor 780 fixable viability dye and for surface markers as described above. Cells were then fixed and permeabilized using the eBioscience Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer set following the manufacturer’s protocol. Permeabilized cells were stained with granzyme B antibody (N4TL33, Invitrogen). Processed samples were run on an LSR II or Symphony A5 five-laser flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), and the data were analyzed using BD FACSDiva software version 6.0 (RRID: SCR_001456) and FlowJo 10.8 (Tree Star, RRID: SCR_008520).

Western blot analysis

Before stimulation and at multiple timepoints during the serial tumor challenge assay, NKT cells with PRDM1 KD or KO and associated controls were dissociated using RIPA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) and Halt protease inhibitors (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and protein concentrations were determined using Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples were denatured in Laemmli buffer (Bio-Rad) containing 5% 2-mercaptoethanol (Bio-Rad) at 95°C for 5 minutes. Cell lysate (15 μg per lane) was run on a 12% SDS polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad) and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Immobilon-P, Millipore). Membranes were blocked in Li-Cor Intercept (TBS) Blocking Buffer and then probed with primary antibodies followed by Li-Cor IRDye-conjugated secondary antibodies. Blots were developed using a Li-Cor Odyssey CLx imager. Protein levels were normalized to loading controls. Primary antibodies were BLIMP1 rabbit antibody (C14A4, Cell Signaling Technology, RRID: AB_2169699) diluted 1:150 and β-actin mouse antibody (8H10D10, Cell Signaling Technology, RRID: AB_2242334) diluted 1:1,000. Secondary antibodies were goat anti-rabbit (926-32211, Li-Cor, RRID: AB_621843) diluted 1:2,000 and goat anti-mouse (926-68070, Li-Cor, RRID: AB_10956588) diluted 1:5,000.

Apoptosis assay

CAR NKTs with PRDM1 KO or KD were cultured with CHLA255 neuroblastoma cells for six cycles of 3 to 4 days following the methods described above for the in vitro serial tumor challenge assay. Four days after tumor challenge in each cycle, cells were harvested, stained with annexin V and 7-aminoactinomycin D (BD Biosciences), and evaluated by flow cytometry.

In vivo mouse experiments

Animal experiments were performed in accordance with and with the approval of the BCM Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee under protocol AN-5194. NOD/SCID gamma (NSG) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory and maintained at the BCM animal care facility. To test the anti-neuroblastoma effect of GD2.CAR NKTs, mice were injected intravenously with 1 × 106 luciferase-transduced CHLA255 neuroblastoma cells to initiate tumor growth. On day 7, mice were injected intravenously with the indicated number of GD2.CAR NKTs followed by i.p. injection of human IL2 (2,000 U/mouse) three times per week for 2 weeks. Tumor growth was assessed once per week by bioluminescent imaging (Perkin Elmer IVIS Lumina III in vivo imaging system, CLS136334, Small Animal Imaging Facility, Texas Children’s Hospital) with i.p. injection of luciferin (3 mg/mouse, Perkin Elmer, 122799) and 5-minute exposure. For in vivo persistence experiments, mice were sacrificed 8 days after GD2.CAR NKT injection. Spleens and livers were harvested and processed into single-cell suspensions using Mouse Tumor Dissociation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec, 130096730) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were stained to determine NKT phenotype and analyzed by flow cytometry as described above.

Bulk RNA-seq and data analysis

To determine the effect of PRDM1 KO on the GD2.CAR NKT transcriptome, bulk RNA-seq was conducted on four donor-paired samples of CD3+iNKT+CAR+ cells sorted by FACS from B2M KO GD2.CAR NKTs or PRDM1 KO GD2.CAR NKTs after five rounds of serial tumor challenge. To determine the effect of PRDM1 KD on the GD2.CAR NKT transcriptome, bulk RNA-seq was conducted on five donor-paired samples of CD3+iNKT+CAR+ cells sorted by FACS from scrambled shRNA GD2.CAR NKTs or PRDM1 shRNA GD2.CAR NKTs after six rounds of serial tumor challenge. RNA was isolated from all NKT samples using RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, 74134). The BCM Genomic and RNA Profiling Core performed library synthesis using Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep Kit. Paired-end sequencing was performed on isolated RNA samples on a NovaSeq 6000 instrument using Illumina PE150 technology (100 ng input per sample, S4 flow cell, dual-indexed, no unique molecular identifiers, and average of 47 million read pairs generated).

Adapters of the sequenced reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic (23); reads shorter than 36 nucleotides were discarded. Reads were then aligned to the human reference GRCh38 using Star aligner (24). Reads with an alignment score below 30 were discarded using samtools (25). The counts per transcript were calculated using featureCounts (26). Differential gene expression analysis was performed using DESeq2 (22). Gene set enrichment analyses (GSEA) were performed using the clusterProfiler (27) function GSEA (eps = 0) on genes ranked on log2 FC in the scrambled shRNA group versus PRDM1 shRNA group at cycles 1 and 6 using gene signatures for T-cell phenotypes as previously reported (28), GSE83978 (29), and GSE123235 (30); P values were adjusted using the Benjamini and Hochberg method.

Statistical analysis

Normality was rejected when the P value was less than 0.05. To evaluate differences in continuous variables, we used two-sided, paired Student t tests to compare two groups and one-way ANOVA with post-test Bonferroni correction to compare more than two groups. Survival was analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method with the log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test to compare two groups. Statistics were computed using GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, RRID: SCR_002798). Differences were considered significant when the P value was less than 0.05.

Data availability

All requests for raw and analyzed data and materials beyond the information provided in the main text and supplementary figures should be directed to the corresponding author. These requests will be promptly reviewed by the BCM Licensing Group to verify whether the request is subject to any intellectual property or confidentiality obligations. Any data and materials that can be shared will be released via a Material Transfer Agreement. All raw RNA-seq data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE261930.

Results

In vitro CRISPR/Cas9 screens identify PRDM1 as a negative regulator of NKT and GD2.CAR NKT proliferation

To identify genes that regulate proliferation of NKTs stimulated via CD1d through the native NKT T-cell receptor, we performed an in vitro CRISPR/Cas9 screen on unmodified NKTs (Fig. 1A). First, we transduced the cells with a gRNA library delivered by a lentiviral vector titrated to ensure that most NKTs received a single viral copy (Supplementary Fig. S1). Next, we exposed NKTs transduced with the gRNA library to six rounds of challenge with CD1d+ J32 Jurkat tumor cells followed by NGS analysis to quantify relative frequencies of gRNAs in prechallenge versus postchallenge NKTs. To identify top hits from the screen, we sequenced the NKT gRNA library before tumor challenge and compared the relative abundance of gRNA sequences with values obtained from cells after four and six tumor challenge cycles. We pooled the top 50 hits from each comparison based on greatest FC in relative abundance, filtering for genes known to be expressed in T cells or NKTs. The eight gRNA sequences with the greatest FC and P value (Fig. 1B) were then validated by expressing individual gRNA sequences in NKTs and performing serial tumor challenge assays. Of the top candidates, we found that compared with B2M KO control cells, only NKTs expressing the PRDM1 gRNA continued to proliferate after multiple rounds of tumor challenge (Fig. 1C; Supplementary Fig. S2).

To determine whether this screen could identify regulatory genes in GD2.CAR-redirected NKTs that may be used to improve their therapeutic efficacy in patients with neuroblastoma, we repeated the screening process with GD2.CAR NKTs and GD2+ CHLA255 neuroblastoma target cells. PRDM1 was also identified as the top hit in GD2.CAR NKTs (Fig. 1D), and we confirmed that PRDM1 KO GD2.CAR NKTs continued to proliferate after repeated challenge with CHLA255 cells (Fig. 1E). The average frequency of CAR+ NKTs in the PRDM1 KO group increased from 30.63% (SD 13.89%) prechallenge to 88.11% (SD 9.69%) after six challenge cycles (Fig. 1F). Furthermore, average PRDM1 KO efficiency in GD2.CAR+ NKTs increased from 38% (SD 26%) prechallenge to 79% (SD 10.53%) of total NKTs after six challenge cycles, whereas B2M KO CAR NKTs showed no significant difference in KO rate before and after (Supplementary Fig. S3). These findings suggest that GD2.CAR+ NKTs with PRDM1 KO proliferate after tumor challenge and potentially have a survival advantage in these conditions. We also measured levels of BLIMP1, the protein encoded by PRDM1, over the course of the serial stimulation assay. In B2M KO control cells, BLIMP1 was upregulated following antigen stimulation in cycle 1 and then declined and plateaued at prestimulation numbers over successive stimulation rounds. In PRDM1 KO cells, BLIMP1 expression levels were consistently lower than in control cells and underwent brief upregulation after stimulation in cycle 1 likely because of contaminating PRDM1 WT cells. Following this, BLIMP1 declined steadily, becoming almost undetectable by cycle 7 (Supplementary Fig. S4). These results show that PRDM1 plays an important regulatory role in the proliferation of unmodified NKTs and GD2.CAR NKTs that have undergone multiple stimulatory encounters with tumor cells.

PRDM1 KO promotes central memory differentiation and decreases cytotoxic activity of GD2.CAR NKTs

To determine how PRDM1 KO impacts GD2.CAR NKT gene expression, we sequenced RNA isolated from PRDM1 KO GD2.CAR NKTs after five rounds of tumor challenge (Fig. 2A; Supplementary Fig. S5). Compared with control GD2.CAR NKTs with B2M KO, PRDM1 KO cells showed upregulation of genes related to central memory differentiation, including SELL, CCR7, LEF1, TCF7, IL7R (CD127), and MYB, in addition to downregulation of exhaustion-related genes LAG3 and PD1. PRDM1 KO also led to downregulation of NR4A1 and NR4A2, which are upregulated in CAR T cells with PRDM1 KO (31). In the case of CD62L (encoded by SELL), we found that most PRDM1 KO GD2.CAR NKTs expressed this central memory marker after six rounds of tumor challenge, whereas B2M KO control cells were predominantly CD62L− (Fig. 2B). PRDM1 KO cells also expressed lower levels of exhaustion markers PD-1, TIGIT, and LAG3, as well as indicators of apoptosis 7-AAD and annexin V, compared with control cells after six rounds of tumor challenge (Fig. 2C and D; Supplementary Figs. S6 and S7). To assess the effector function of GD2.CAR NKTs with PRDM1 KO, the cells first underwent six rounds of tumor challenge followed by a real-time cytotoxicity assay and intracellular cytokine staining for IL2, IFNγ, and TNFα. Although a greater proportion of PRDM1 KO cells produced multiple cytokines than control cells (Fig. 2E), we found that PRDM1 KO negatively affected cytotoxicity and that PRDM1 KO cells expressed lower levels of granzyme B than control cells (Fig. 2F and G). Following the first tumor challenge cycle, PRDM1 KO and control B2M KO cells had similar cytotoxic activity and granzyme B production levels, suggesting that these changes occurred after multiple encounters with tumor antigen (Supplementary Fig. S8). Next, we evaluated the in vivo antitumor activity of PRDM1 KO GD2.CAR NKTs in a xenograft model of neuroblastoma in which NSG mice were intravenously injected with luciferase-transduced GD2+ CHLA255 neuroblastoma cells and 7 days later received either PRDM1 KO or control B2M KO GD2.CAR NKTs (Fig. 2H). We found that PRDM1 KO cells mediated superior antitumor activity that significantly extended the survival of treated mice versus those that received control cells (P = 0.0084; Fig. 2I and J; Supplementary Fig. S9). Together, these results demonstrate that knocking out PRDM1 promotes central memory differentiation, reduces exhaustion marker expression and apoptosis, and encourages production of multiple cytokines by GD2.CAR NKTs after multiple rounds of tumor challenge. However, we found that effector cytotoxicity was compromised during in vitro serial tumor challenge and that although PRDM1 KO GD2.CAR NKTs mediated more potent in vivo antitumor activity than control cells, the resulting improvement in survival was modest.

Figure 2.

PRDM1 KO promotes central memory differentiation and decreases cytotoxic activity of GD2.CAR NKTs. A, Volcano plot showing differentially expressed genes in B2M KO vs. PRDM1 KO samples. Bulk RNA-seq was conducted on four donor-paired samples of CD3+iNKT+CAR+ NKTs sorted by FACS from B2M KO GD2.CAR NKTs or PRDM1 KO GD2.CAR NKTs after five rounds of serial tumor challenge. Red dots show genes downregulated in PRDM1 KO vs. B2M KO samples (log2 FC ≥ 1, adjusted P value ≤ 0.05). Blue dots show genes upregulated in PRDM1 KO vs. B2M KO samples (log2 FC ≤ −1, adjusted P value ≤ 0.05). B, CD62L expression in GD2.CAR NKTs with PRDM1 or B2M KO after six cycles of tumor challenge. Representative donor (left) and summary of seven donors; B2M average: 5.5%, SD = 6.1; PRDM1 average: 59.4%, SD = 23.4; P = 0.0009. C, PD-1 expression in GD2.CAR NKTs with PRDM1 or B2M KO after six cycles of tumor challenge. Representative donor (left) and summary of four donors; B2M average: 73.7%, SD = 7.3; PRDM1 average: 29.4%, SD = 14.2; P = 0.0186. D, TIGIT expression in GD2.CAR NKTs with PRDM1 or B2M KO after six cycles of tumor challenge. Representative donor (left) and summary of four donors; B2M average: 65.1%, SD = 16.2; PRDM1 average: 51.7%, SD = 19.9; P = 0.036. E, Pie charts showing proportion of CD4+B2M KO and PRDM1 KO GD2.CAR NKTs that produce 0, 1, 2, or 3 cytokines (IL2, TNFα, and IFNγ) in one representative of two donors. NKTs were harvested after six cycles of tumor challenge and stimulated for 4 hours with PMA/ionomycin using Golgi/endoplasmic reticulum block. Following stimulation, intracellular cytokine staining was performed. F, Real-time cellular impedance monitoring of B2M KO and PRDM1 KO GD2.CAR NKT cytotoxicity against CHLA255 cells. After six rounds of tumor challenge, GD2.CAR NKTs were cocultured 1:1 with CHLA255 cells and subject to 60 hours of impedance monitoring using xCELLigence technology with nontransduced (NT) NKTs as negative control. Mean ± SD of triplicates, representative of two donors. G, Granzyme B expression by CD4−B2M KO and PRDM1 KO GD2.CAR NKTs. CAR.NKTs were stimulated with CHLA255 cells after six rounds of tumor challenge. Five days after stimulation, granzyme B production was measured by intracellular staining. Data from one representative of two donors is shown. H, Experimental design for evaluating in vivo antitumor activity of PRDM1 KO CAR.NKTs in xenograft mouse model of neuroblastoma. NSG mice were injected with 1 × 106 GD2+luciferase+ CHLA255 cells intravenously on day 0, and 10 × 106 CAR.NKTs with either B2M KO or PRDM1 KO were injected intravenously on day 7. Tumor growth was measured by in vivo imaging system (IVIS) weekly. I, Kaplan–Meier survival curve of NSG mice with neuroblastoma xenografts treated with B2M KO or PRDM1 KO GD2.CAR NKTs, P = 0.0084, log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test. J, Tumor bioluminescence for individual mice from (H). *, P = 0.0157, PRDM1 KO vs. tumor alone; P = 0.0327, PRDM1 KO vs. B2M KO control. Luc; luciferase.

PRDM1 KD via shRNA promotes formation of central memory cells while preserving cytotoxic activity of GD2.CAR NKTs

Based on our findings in PRDM1 KO GD2.CAR NKTs, we reasoned that a low level of PRDM1 expression may be required to preserve the cytotoxic effector function of these cells. Therefore, we designed shRNA sequences specific to PRDM1 and modified the GD2.CAR construct to coexpress the shRNA in the same retroviral vector (Supplementary Fig. S10). NKTs expressing the shRNA.PRDM1.GD2.CAR construct showed reduced BLIMP1 expression compared with CAR-only and scrambled shRNA control groups (Fig. 3A). As with PRDM1 KO cells, we found that PRDM1 KD GD2.CAR NKTs proliferated robustly compared with control cells over six rounds of tumor challenge with GD2+ CHLA255 cells (Fig. 3B). Moreover, over the course of the repeat stimulation assay, the percentage of CAR+ cells increased significantly in PRDM1 KD NKTs but not the scrambled shRNA control group (Supplementary Fig. S11). In the same assay, BLIMP1 was upregulated in KD control cells after stimulation in cycle 1 before declining and plateauing over successive stimulation rounds like KO control cells. In PRDM1 KD cells, BLIMP1 levels remained stable through cycle 1 and then declined over the next challenge rounds (Supplementary Fig. S12).

Figure 3.

PRDM1 KD via shRNA promotes formation of central memory cells while preserving cytotoxic activity of GD2.CAR NKTs. A, BLIMP1 was overexpressed in Jurkat cells, and then the cells were transduced with the GD2.CAR construct coexpressing PRDM1-specific shRNA (PRDM1 KD) or scrambled control shRNA (Scr). Histograms show KD efficiency of PRDM1-specific shRNA in Jurkat cells as determined by intracellular staining for BLIMP1. B, GD2.CAR NKTs coexpressing PRDM1 shRNA or scrambled control shRNA were challenged with GD2+ CHLA255 cells over six rounds. GD2.CAR+ NKT numbers were determined at the end of each challenge cycle by counting and FACS. Shown are GD2.CAR+ NKT FC values at the end of each cycle for a representative donor and paired overall GD2.CAR+ NKT FC for PRDM1 KD, scrambled control, and CAR only cells. N = 8; Scr. average: 17.6, SD = 17.7; CAR-only average: 63.3, SD = 117.2; PRDM1 KD average: 1,350.9, SD = 1,619.8. C, CD62L expression in GD2.CAR NKTs with PRDM1 KD or scrambled control after cycle six of tumor challenge. Representative donor (left) and summary of nine donors; Scr. average: 7.8%, SD = 4.3; CAR-only average: 6.9%, SD = 4; PRDM1 KD average: 19.8%, SD = 7.8. D, PD-1 expression in GD2.CAR NKTs with PRDM1 KD or scrambled control after cycle six of tumor challenge. Representative donor (left) and summary of eight donors; Scr. average: 35.3%, SD = 16.6; CAR-only average: 35.3%, SD = 19.7; PRDM1 KD average: 12.9%, SD = 9.8; P = 0.029 and P = 0.0047. E, Real-time cellular impedance monitoring of PRDM1 KD GD2.CAR NKT and scrambled shRNA GD2.CAR NKT cytotoxicity against CHLA255 cells. After six rounds of tumor challenge, GD2.CAR NKTs were cocultured 1:4 (effect-to-target ratio) with CHLA255 cells and subject to 60 hours of impedance monitoring using xCELLigence technology with CAR-only and nontransduced (NT) NKTs as negative controls. Mean ± SD of triplicates, representative of four donors. F, Granzyme B expression by CD4−PRDM1 KD and scrambled shRNA GD2.CAR NKTs. CAR.NKTs were stimulated with CHLA255 cells after six rounds of tumor challenge. Five days after stimulation, granzyme B production was measured by intracellular staining. Data from one representative of three donors. G, Pie charts showing proportion of CD4+PRDM1 KD and scrambled control GD2.CAR NKTs that produce 0, 1, 2, or 3 cytokines (IL2, TNFα, and IFNγ) in one representative of five donors. CAR.NKTs were harvested after six rounds of serial killing and stimulated with PMA/ionomycin for four hours using Golgi/endoplasmic reticulum block. Following stimulation, intracellular cytokine staining was performed. Graph (right) shows the percentage of triple-cytokine positive CD4+ GD2.CAR+ NKTs; Scr. average: 15.2%, SD = 6.5; CAR-only average: 17.4%, SD = 8.2; PRDM1 KD average: 46.7%, SD = 20.3; P = 0.0324. ns, not significant.

Next, we measured expression of central memory and exhaustion markers after six rounds of tumor challenge. GD2.CAR NKTs with PRDM1 KD expressed higher levels of CD62L than scrambled control cells but lower levels than PRDM1 KO cells (Fig. 3C). Like PRDM1 KO cells, KD cells expressed lower levels of PD-1, TIGIT, CD39, and apoptosis markers than control cells (Fig. 3D; Supplementary Figs. S13 and S14); unlike PRDM1 KO cells, PRDM1 KD cells maintained potent cytotoxicity and granzyme B production after six rounds of tumor challenge (Fig. 3E and F). Intracellular cytokine staining results were consistent with findings from PRDM1 KO cells, with more PRDM1 KD cells producing multiple cytokines than scrambled shRNA and CAR-only control cells (Fig. 3G). In all, knocking down PRDM1 expression in GD2.CAR NKTs using shRNA had a similar impact on NKT phenotype as PRDM1 KO, with the important difference that NKT effector cytotoxicity was preserved in PRDM1 KD cells after multiple rounds of tumor challenge.

To determine the impact of PRDM1 KD on the GD2.CAR NKT transcriptome, we defined the genome-wide expression profile of GD2.CAR NKTs with and without PRDM1 KD after one and six cycles of serial tumor challenge and compared it with scrambled shRNA KD control profiles. We detected few notable differences in gene expression between WT GD2.CAR NKTs and scrambled control NKTs at both time points, indicating that the scrambled shRNA sequence did not impact the transcriptomic profile of GD2.CAR NKTs (Supplementary Fig. S15). Unsupervised hierarchical clustering and principal component analysis showed that PRDM1 KD NKTs acquired a distinct gene expression profile from the scrambled control group after one and six cycles of serial tumor challenge (Fig. 4A; Supplementary Fig. S16). Upregulated genes in PRDM1 KD GD2.CAR NKTs included memory-associated transcription factors and surface molecules (LEF1, IL7R, SELL, MYB, BATF3, and CCR7), whereas genes associated with terminal differentiation and exhaustion were downregulated (TIGIT, PDCD1, and LAG3). We also found that genes related to effector function, including GZMM, GZMH, GZMA, IL2, GZMB, TNF, IFNG, and PRF1, were expressed at similar or elevated levels compared with PRDM1 KO levels after six rounds of tumor challenge, consistent with intracellular cytokine staining and cytotoxicity data. As previously described for PRDM1-deficient T cells (32), we found that TOX, which promotes T-cell exhaustion, was also upregulated in PRDM1 KD GD2.CAR NKTs. Although we found that NR4A1 expression in PRDM1 KO cells was significantly lower than in B2M KO control cells after five cycles of tumor challenge, we did not detect a similar difference between PRDM1 KD cells and scrambled control cells after six challenge cycles (Supplementary Fig. S17). This may be due to differences in the efficiency of PRDM1 KO versus KD or potentially that residual PRDM1 expression in KD cells altered the phenotype compared with complete protein loss. GSEA demonstrated that genes associated with the T-cell memory phenotype were significantly enriched in PRDM1 KD GD2.CAR NKTs (Fig. 4B), aligning with their ability to maintain proliferation after multiple antigen exposures. Additionally, we demonstrated that genes associated with T-cell exhaustion were reduced in PRDM1 KD GD2.CAR NKTs whereas genes related to proliferation and CD8+ T-cell effector memory phenotype were enriched, indicating intact effector function in these cells (Fig. 4C–E). Collectively, these findings suggest that PRDM1 KD leads to transcriptomic changes that influence the functional properties of GD2.CAR NKTs, resulting in less exhausted, more memory-like cells that continue to proliferate and exert effector function after multiple rounds of tumor challenge.

Figure 4.

PRDM1 KD results in transcriptomic changes in GD2.CAR NKTs associated with increased memory formation and decreased exhaustion. GD2.CAR NKTs with either PRDM1 KD or scrambled control cells (Scr) were challenged 1:1 with CHLA255 cells every 3 to 4 days for six rounds. Seven days after cycle 1 and cycle 6, CD3+iNKT+CAR+ NKTs were sorted by FACS, and RNA was isolated and processed for RNA-seq. A, Heat map of differentially expressed genes of interest. Each value represents an average from five to six donors. B, GSEA plots showing T-cell early memory phenotype signature in PRDM1 KD vs. scrambled control GD2.CAR NKTs (nominal P values are shown). C, GSEA plots showing T-cell exhaustion phenotype signature in PRDM1 KD vs. scrambled control GD2.CAR NKTs. D, GSEA plots showing gene signature associated with T-cell proliferation in PRDM1 KD vs. scrambled control GD2.CAR NKTs. E, GSEA plots showing T-cell effector memory phenotype signature in PRDM1 KD vs. scrambled control GD2.CAR NKTs. NES, normalized enrichment scale.

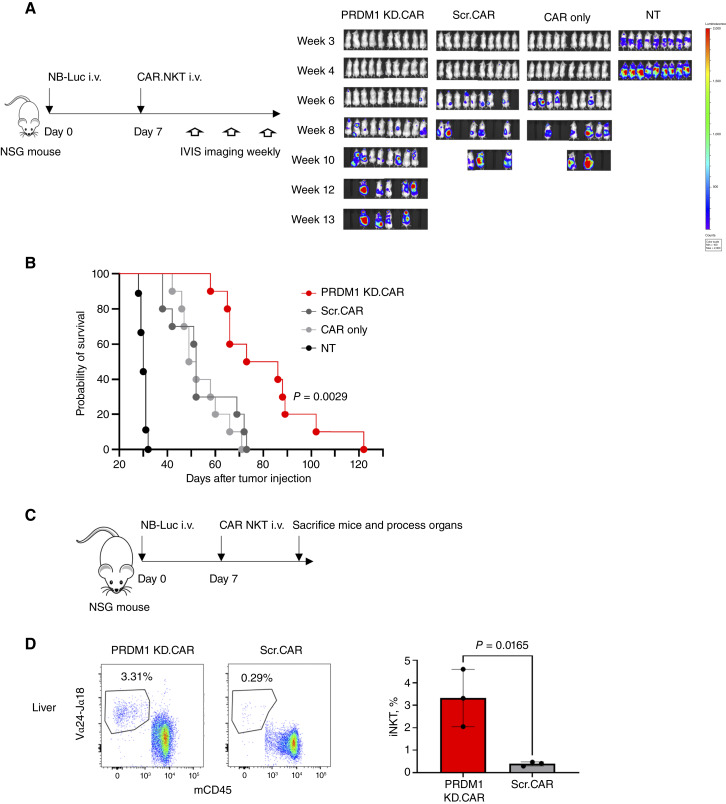

GD2.CAR NKTs with PRDM1 KD persist and mediate antitumor activity in an in vivo xenograft mouse model of neuroblastoma

Next, we sought to evaluate the ability of GD2.CAR NKTs with PRMD1 KD to persist and control tumor burden in vivo. NSG mice were injected intravenously with luciferase-transduced GD2+ CHLA255 neuroblastoma cells and 7 days later received either PRDM1 KD cells, scrambled shRNA control cells, CAR-only control cells, or nontransduced cells (Fig. 5A). We found that PRDM1 KD cells effectively controlled tumor growth and significantly prolonged animal survival compared with all control groups (Fig. 5B; Supplementary Fig. S18). To assess in vivo persistence, PRDM1 KD or control shRNA GD2.CAR NKTs were injected into NSG mice with 7-day established CHLA255 neuroblastoma tumors (Fig. 5C). Mice were sacrificed 8 days after NKT injection, and spleens and livers were processed and stained for Vα24Jα18+ NKTs among the CD45+ cell population (Supplementary Fig. S19). We detected significantly more NKT cells in the organs of mice treated with PRDM1 KD cells versus scrambled shRNA control cells (Fig. 5D; Supplementary Fig. S20). These results demonstrate that knocking down PRDM1 expression enhances the in vivo antitumor activity of GD2.CAR NKTs in a neuroblastoma xenograft model and that this activity is associated with the ability of these cells to persist in multiple organs after injection.

Figure 5.

GD2.CAR NKTs with PRDM1 KD persist and mediate antitumor activity in an in vivo xenograft mouse model of neuroblastoma. A, Experimental design for evaluating in vivo antitumor activity of PRDM1 KD GD2.CAR NKTs vs. scrambled shRNA GD2.CAR control cells (Scr). NSG mice were injected with 1 × 106 GD2+luciferase+ CHLA255 cells intravenously on day 0, and 10 × 106 GD2.CAR NKTs with either PRDM1-specific or scrambled shRNA were injected intravenously on day 7. Nontransduced (NT) and CAR-only NKTs were used as controls. Tumor growth was measured by in vivo imaging system (IVIS) weekly. B, Kaplan–Meier survival curve of NSG mice with neuroblastoma xenografts treated with PRDM1 KD or scrambled control CAR.NKTs, P = 0.0029, log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test. C, Experimental design for evaluating in vivo persistence of GD2.CAR NKTs in the liver. NSG mice were injected with 1 × 106 CHLA255 cells intravenously on day 0, and 10 × 106 GD2.CAR+ NKTs with either PRDM1-specific or scrambled shRNA were injected intravenously on day 7. Mice were sacrificed on day 15, and cells from the liver were isolated and analyzed by FACS. D, Flow cytometry staining of Vα24/Jα18+ NKTs in processed liver cells gated on all human CD45 and mouse CD45 cells from a representative mouse in indicated treatment groups (left). Summary data for percent Vα24/Jα18+ NKTs in mouse and human CD45+ cells from three mice per group; PRDM1 KD average: 3.32%, SD = 1.04; Scr. average: 0.39%, SD = 0.07; P = 0.0165. Luc, luciferase.

Discussion

In this study, we developed an unbiased CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis screen for regulatory genes in human NKTs and CAR NKTs and identified PRDM1 as a negative regulator of the central memory phenotype and effector function in these cells. NKT central memory differentiation is crucial to the efficacy of NKT-based immunotherapies, and few mediators of this NKT phenotype have been identified. Our high-throughput screening protocol used CRISPR/Cas9 technology and a targeted gRNA library to generate a pool of NKT cells, each with a single gene knocked out, which we then exposed to multiple rounds of in vitro tumor challenge followed by NGS. Through this process, we identified eight initial top gene hits that could be involved in the regulation NKT cell function. We determined through validation experiments that one of these candidates, PRDM1 KO, promoted the highest level of sustained proliferation in both NKTs and GD2.CAR NKTs over multiple rounds of tumor challenge. Next, we found that after six rounds of tumor challenge, GD2.CAR NKTs with PRDM1 KO upregulated genes related to central memory differentiation, including SELL and LEF1, and downregulated exhaustion-associated genes, including LAG3 and PD1. Assessment of effector function revealed that knocking out PRDM1 reduced granzyme B production and compromised GD2.CAR NKT cytotoxicity. PRDM1 KO cells mediated more potent in vivo antitumor activity than control cells in a xenograft mouse model of neuroblastoma, but the difference was modest. Importantly, knocking down PRDM1 expression in GD2.CAR NKTs using shRNA promoted expression of central memory-related genes while also preserving in vitro cytotoxicity after multiple rounds of tumor challenge. In the same neuroblastoma mouse model, PRDM1 KD GD2.CAR NKTs effectively controlled tumor burden, prolonged animal survival, and persisted longer in multiple organs of treated mice relative to control cells.

Although CRISPR-based screens have been used in T cells to identify genes involved in multiple cellular functions (15, 33, 34), we believe that this is the first study to describe an unbiased screen for regulatory genes in NKT cells. We show that by pairing CRISPR/Cas9 high-throughput screening technology with an in vitro serial tumor challenge assay, we could successfully single out genes that influence NKT central memory differentiation, effector function, and ultimately in vivo antitumor activity and persistence. Using this approach, we identified PRDM1 as a top candidate in screens of both unmodified NKTs and CAR NKTs, which are activated through independent mechanisms, providing built-in validation for the role of this gene in NKTs and demonstrating the power of the screening process.

BLIMP1, encoded by PRDM1, is an evolutionarily conserved transcriptional regulator originally described as a repressor of gene transcription. BLIMP1 regulates gene expression by competing with other transcription factors for binding sites and/or by recruiting cofactors that enable chromatin modifications that repress transcription of target genes (35, 36). The role of BLIMP1 has been described in several types of immune cells. In B and T cells, BLIMP1 and Bcl6 act antagonistically to regulate differentiation and proliferation (37–39), and in B cells, BLIMP1 is involved in plasmablast development and is required for plasma cell differentiation and antibody production (40). In dendritic cells, BLIMP1 drives effector function and controls inflammation during immune responses by regulating T-cell priming and activation (41). BLIMP1 also represses IL2 and IL17 expression and induces IL10 expression in Treg cells (42, 43).

In T cells, BLIMP1 is known to help control T-cell homeostasis and effector differentiation, and it is expressed at higher levels in effector cells after activation and at lower levels in naïve cells (44). We show that a similar trend holds in NKT cells, in which BLIMP1 level increases after NKT activation via CAR stimulation and decreases over multiple rounds of antigen exposure. Additionally, BLIMP1-deficient T cells undergo less activation-induced cell death than WT cells (45). In CAR T cells, BLIMP1 has recently been implicated as a negative regulator of stemness and antitumor activity by several groups. Yoshikawa and colleagues (32) found that CRISPR-mediated PRDM1 KO promotes expansion of less-differentiated memory CAR T cells with enhanced in vivo persistence and therapeutic activity. PRDM1 KO CAR T cells secreted multiple cytokines but did not show enhanced proliferation after multiple rounds of in vitro tumor challenge. Jung and colleagues (31) found that low PRDM1 expression was associated with CAR T antitumor potency in patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Whereas PRDM1 KO promoted CAR T-cell proliferation and stemness and marginally improved antitumor activity in vivo, compensatory upregulation of exhaustion mediator NR4A3 hampered this enhanced T-cell effector function. A dual KO strategy targeting both PRDM1 and NR4A3 was required to achieve the therapeutic benefits associated with ablation of PRDM1 expression in CAR T cells. These results and those from our own study illuminate substantial overlap between T cells and NKTs for the regulatory role of PRDM1, with important differences that emphasize the advantages of targeting this mediator in NKTs specifically. For example, the impact of PRDM1 repression on CAR T-cell proliferation remains unclear, whereas our results show that knocking out PRDM1 in NKTs dramatically boosts proliferation. Additionally, we did not detect the compensatory upregulation of NR4A3 described in CAR T cells that led to the need for a dual KO approach and instead found that PRDM1 KO was associated with downregulation of exhaustion markers in CAR NKTs. For both cell types, PRDM1 KO steers toward central memory differentiation but reduces effector activity. In CAR T cells, this seems to be the result of upregulated exhaustion mediators like NR4A3, but this would not explain similar findings in CAR NKTs. We reasoned that the observed downregulation of the cytotoxicity mediator granzyme B could mechanistically explain reduced effector function in CAR NKTs, and following this insight, we pivoted toward shRNA-mediated KD of PRDM1 expression as opposed to full genetic ablation. This approach achieved the desired effect in NKTs, leading to upregulation of central memory–associated genes while also preserving granzyme B expression and cytotoxic effector function in vitro and in vivo.

In summary, we developed a CRISPR/Cas9 screen in human NKTs and CAR NKTs to identify regulatory genes that influence NKT functional fitness. We used this screening protocol to successfully identify PRDM1 as a mediator of NKT central memory differentiation and effector function. Our results suggest that knocking down PRDM1 expression in NKTs is a promising therapeutic approach, and future studies will progress toward that goal. Additionally, to build on this study and increase its power for identifying functional mediators in NKT cells, we will expand our gRNA library to cover the whole genome.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure S1. Titration of lentiviral vector to identify viral volume for gRNA library transduction.

Supplemental Figure S2. Validation of top eight gRNA hits from CRISPR/Cas9 screen.

Supplemental Figure S3. PRDM1 and B2M gene knockout efficiency before and after serial tumor challenge.

Supplemental Figure S4. BLIMP1 levels in PRDM1 KO CAR NKTs and control prior to and after multiple rounds of tumor challenge.

Supplemental Figure S5. Heat map of differentially expressed genes of interest in B2M KO versus PRDM1 KO samples after 1 or 5 rounds of serial tumor challenge.

Supplemental Figure S6. PRDM1 KO cells express lower levels of LAG3 than B2M KO cells after six cycles of tumor challenge.

Supplemental Figure S7. PRDM1 KO cells undergo less apoptosis than B2M KO control cells after six cycles of tumor challenge.

Supplemental Figure S8. PRDM1 KO and B2M KO GD2.CAR NKTs demonstrate similar levels of cytotoxic activity and granzyme B production after one round of tumor challenge.

Supplemental Figure S9. Weekly bioluminescence imaging of NB tumor growth described in Figure 2J.

Supplemental Figure S10. shRNA.PRDM1.GD2.CAR construct design.

Supplemental Figure S11. GD2.CAR+ percentage increases after six tumor challenge cycles in PRDM1 KD NKTs but not scrambled shRNA control (scr) NKTs.

Supplemental Figure S12. BLIMP1 levels in PRDM1 KD GD2.CAR NKTs prior to and after multiple rounds of tumor challenge.

Supplemental Figure S13. GD2.CAR NKTs with PRDM1 KD express lower levels of TIGIT and CD39 than scrambled control cells after six cycles of tumor challenge.

Supplemental Figure S14. PRDM1 KD cells undergo less apoptosis than scr control cells after six cycles of tumor challenge.

Supplemental Figure S15. GD2.CAR NKTs and scr control GD2.CAR NKTs have similar gene expression profiles after one and six cycles of tumor challenge.

Supplemental Figure S16. PRDM1 KD NKTs acquire a distinct gene expression profile from scr control cells after one and six cycles of serial tumor challenge.

Supplemental Figure S17. PRDM1 KO but not KD leads to significant reduction of NR4A1 expression versus control after multiple tumor challenge cycles.

Supplemental Figure S18. Tumor bioluminescence for individual mice from experiment in Figure 5A.

Supplemental Figure S19. Gating strategy to measure iNKT cell frequency in liver or spleen on mouse experiment described in Figure 5D.

Supplemental Figure S20. NKT cells are detected at significantly higher numbers in the spleens of mice treated with PRDM1 KD cells versus scr control cells.

Supplementary Table 1

Supplementary Table 2

Supplementary Table 3

Supplementary Table 4

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the excellent technical assistance provided by the staff at Flow Cytometry Core Laboratory of the Texas Children’s Cancer and Hematology Center and Small Animal Imaging core facility at Texas Children’s Hospital. We thank Immunai, Inc. for contributions to the gRNA library design and synthesis. This work was supported by grants from the NIH (RO1 CA262250 to L.S. Metelitsa and K12 CA090433, Faculty Fellowship – Pediatric Oncology Clinical Research Training Program, to G. Tian), Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (BCM Comprehensive Cancer Center Training Program, RP210027 to G. Tian), Hyundai Hope on Wheels award # 983124, and Kate Amato Foundation award (to G. Tian).

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Cancer Immunology Research Online (http://cancerimmunolres.aacrjournals.org/).

Authors’ Disclosures

G. Tian reports grants from Hyundai Hope on Wheels, Kate Amato Foundation, and K12 Pediatric Oncology Research Training Program during the conduct of the study. A. Montalbano reports other support from Immunai outside the submitted work. L.S. Metelitsa reports grants from the NIH and nonfinancial support from Immunai during the conduct of the study. No disclosures were reported by the other authors.

Authors’ Contributions

G. Tian: Conceptualization, resources, formal analysis, supervision, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing. G.A. Barragan: Investigation. H. Yu: Investigation. C. Martinez-Amador: Investigation. A. Adaikkalavan: Investigation. X. Rios: Methodology. L. Guo: Investigation. J.M. Drabek: Investigation. O. Pardias: Investigation. X. Xu: Investigation. A. Montalbano: Data curation, formal analysis. C. Zhang: Data curation, formal analysis. Y. Li: Investigation. A.N. Courtney: Formal analysis, investigation. E.J. Di Pierro: Writing–review and editing. L.S. Metelitsa: Conceptualization, supervision, funding acquisition, writing–review and editing.

References

- 1. Kronenberg M, Gapin L. The unconventional lifestyle of NKT cells. Nat Rev Immunol 2002;2:557–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cui J, Shin T, Kawano T, Sato H, Kondo E, Toura I, et al. Requirement for Valpha14 NKT cells in IL-12-mediated rejection of tumors. Science 1997;278:1623–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Metelitsa LS, Wu H-W, Wang H, Yang Y, Warsi Z, Asgharzadeh S, et al. Natural killer T cells infiltrate neuroblastomas expressing the chemokine CCL2. J Exp Med 2004;199:1213–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smyth MJ, Wallace ME, Nutt SL, Yagita H, Godfrey DI, Hayakawa Y. Sequential activation of NKT cells and NK cells provides effective innate immunotherapy of cancer. J Exp Med 2005;201:1973–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Song L, Asgharzadeh S, Salo J, Engell K, Wu H-w, Sposto R, et al. Valpha24-invariant NKT cells mediate antitumor activity via killing of tumor-associated macrophages. J Clin Invest 2009;119:1524–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ko H-J, Lee J-M, Kim Y-J, Kim Y-S, Lee K-A, Kang C-Y. Immunosuppressive myeloid-derived suppressor cells can be converted into immunogenic APCs with the help of activated NKT cells: an alternative cell-based antitumor vaccine. J Immunol 2009;182:1818–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu D, Song L, Wei J, Courtney AN, Gao X, Marinova E, et al. IL-15 protects NKT cells from inhibition by tumor-associated macrophages and enhances antimetastatic activity. J Clin Invest 2012;122:2221–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cortesi F, Delfanti G, Grilli A, Calcinotto A, Gorini F, Pucci F, et al. Bimodal CD40/Fas-dependent crosstalk between iNKT cells and tumor-associated macrophages impairs prostate cancer progression. Cell Rep 2018;22:3006–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Motohashi S, Kobayashi S, Ito T, Magara KK, Mikuni O, Kamada N, et al. Preserved IFN-alpha production of circulating Valpha24 NKT cells in primary lung cancer patients. Int J Cancer 2002;102:159–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tachibana T, Onodera H, Tsuruyama T, Mori A, Nagayama S, Hiai H, et al. Increased intratumor Valpha24-positive natural killer T cells: a prognostic factor for primary colorectal carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res 2005;11:7322–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tian G, Courtney AN, Jena B, Heczey A, Liu D, Marinova E, et al. CD62L+ NKT cells have prolonged persistence and antitumor activity in vivo. J Clin Invest 2016;126:2341–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ngai H, Barragan GA, Tian G, Balzeau JC, Zhang C, Courtney AN, et al. LEF1 drives a central memory program and supports antitumor activity of natural killer T cells. Cancer Immunol Res 2023;11:171–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Heczey A, Xu X, Courtney AN, Tian G, Barragan GA, Guo L, et al. Anti-GD2 CAR-NKT cells in relapsed or refractory neuroblastoma: updated phase 1 trial interim results. Nat Med 2023;29:1379–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Freitas KA, Belk JA, Sotillo E, Quinn PJ, Ramello MC, Malipatlolla M, et al. Enhanced T cell effector activity by targeting the Mediator kinase module. Science 2022;378:eabn5647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schmidt R, Steinhart Z, Layeghi M, Freimer JW, Bueno R, Nguyen VQ, et al. CRISPR activation and interference screens decode stimulation responses in primary human T cells. Science 2022;375:eabj4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wei J, Long L, Zheng W, Dhungana Y, Lim SA, Guy C, et al. Targeting REGNASE-1 programs long-lived effector T cells for cancer therapy. Nature 2019;576:471–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mouchess ML, Sohara Y, Nelson MD Jr, DeCLerck YA, Moats RA. Multimodal imaging analysis of tumor progression and bone resorption in a murine cancer model. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2006;30:525–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Makni H, Malter JS, Reed JC, Nobuhiko S, Lang G, Kioussis D, et al. Reconstitution of an active surface CD2 by DNA transfer in CD2−CD3+ Jurkat cells facilitates CD3-T cell receptor-mediated IL-2 production. J Immunol 1991;146:2522–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xu X, Huang W, Heczey A, Liu D, Guo L, Wood M, et al. NKT cells coexpressing a GD2-specific chimeric antigen receptor and IL15 show enhanced in vivo persistence and antitumor activity against neuroblastoma. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:7126–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Relander T, Johansson M, Olsson K, Ikeda Y, Takeuchi Y, Collins M, et al. Gene transfer to repopulating human CD34+ cells using amphotropic-GALV-or RD114-pseudotyped HIV-1-based vectors from stable producer cells. Mol Ther 2005;11:452–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li W, Xu H, Xiao T, Cong L, Love MI, Zhang F, et al. MAGeCK enables robust identification of essential genes from genome-scale CRISPR/Cas9 knockout screens. Genome Biol 2014;15:554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014;15:550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014;30:2114–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 2013;29:15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Danecek P, Bonfield JK, Liddle J, Marshall J, Ohan V, Pollard MO, et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. Gigascience 2021;10:giab008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2014;30:923–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wu T, Hu E, Xu S, Chen M, Guo P, Dai Z, et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: a universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation (Camb) 2021;2:100141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cai C, Samir J, Pirozyan MR, Adikari TN, Gupta M, Leung P, et al. Identification of human progenitors of exhausted CD8+ T cells associated with elevated IFN-gamma response in early phase of viral infection. Nat Commun 2022;13:7543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Utzschneider DT, Charmoy M, Chennupati V, Pousse L, Ferreira DP, Calderon-Copete S, et al. T cell factor 1-expressing memory-like CD8+ T cells sustain the immune response to chronic viral infections. Immunity 2016;45:415–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Miller BC, Sen DR, Al Abosy R, Bi K, Virkud YV, LaFleur MW, et al. Subsets of exhausted CD8+ T cells differentially mediate tumor control and respond to checkpoint blockade. Nat Immunol 2019;20:326–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jung I-Y, Narayan V, McDonald S, Rech AJ, Bartoszek R, Hong G, et al. BLIMP1 and NR4A3 transcription factors reciprocally regulate antitumor CAR T cell stemness and exhaustion. Sci Transl Med 2022;14:eabn7336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yoshikawa T, Wu Z, Inoue S, Kasuya H, Matsushita H, Takahashi Y, et al. Genetic ablation of PRDM1 in antitumor T cells enhances therapeutic efficacy of adoptive immunotherapy. Blood 2022;139:2156–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cortez JT, Montauti E, Shifrut E, Gatchalian J, Zhang Y, Shaked O, et al. CRISPR screen in regulatory T cells reveals modulators of Foxp3. Nature 2020;582:416–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Henriksson J, Chen X, Gomes T, Ullah U, Meyer KB, Miragaia R, et al. Genome-wide CRISPR screens in T helper cells reveal pervasive crosstalk between activation and differentiation. Cell 2019;176:882–96.e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ren B, Chee KJ, Kim TH, Maniatis T. PRDI-BF1/Blimp-1 repression is mediated by corepressors of the Groucho family of proteins. Genes Dev 1999;13:125–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yu J, Angelin-Duclos C, Greenwood J, Liao J, Calame K. Transcriptional repression by blimp-1 (PRDI-BF1) involves recruitment of histone deacetylase. Mol Cell Biol 2000;20:2592–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tunyaplin C, Shaffer AL, Angelin-Duclos CD, Yu X, Staudt LM, Calame KL. Direct repression of prdm1 by Bcl-6 inhibits plasmacytic differentiation. J Immunol 2004;173:1158–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Martins G, Calame K. Regulation and functions of Blimp-1 in T and B lymphocytes. Annu Rev Immunol 2008;26:133–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ichii H, Sakamoto A, Hatano M, Okada S, Toyama H, Taki S, et al. Role for Bcl-6 in the generation and maintenance of memory CD8+ T cells. Nat Immunol 2002;3:558–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Turner CA Jr, Mack DH, Davis MM. Blimp-1, a novel zinc finger-containing protein that can drive the maturation of B lymphocytes into immunoglobulin-secreting cells. Cell 1994;77:297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ko Y-A, Chan Y-H, Liu C-H, Liang J-J, Chuang T-H, Hsueh Y-P, et al. Blimp-1-mediated pathway promotes type I IFN production in plasmacytoid dendritic cells by targeting to interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase M. Front Immunol 2018;9:1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bankoti R, Ogawa C, Nguyen T, Emadi L, Couse M, Salehi S, et al. Differential regulation of Effector and Regulatory T cell function by Blimp1. Sci Rep 2017;7:12078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cretney E, Leung PS, Trezise S, Newman DM, Rankin LC, Teh CE, et al. Characterization of Blimp-1 function in effector regulatory T cells. J Autoimmun 2018;91:73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nadeau S, Martins GA. Conserved and unique functions of Blimp1 in immune cells. Front Immunol 2021;12:805260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kallies A, Hawkins ED, Belz GT, Metcalf D, Hommel M, Corcoran LM, et al. Transcriptional repressor Blimp-1 is essential for T cell homeostasis and self-tolerance. Nat Immunol 2006;7:466–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure S1. Titration of lentiviral vector to identify viral volume for gRNA library transduction.

Supplemental Figure S2. Validation of top eight gRNA hits from CRISPR/Cas9 screen.

Supplemental Figure S3. PRDM1 and B2M gene knockout efficiency before and after serial tumor challenge.

Supplemental Figure S4. BLIMP1 levels in PRDM1 KO CAR NKTs and control prior to and after multiple rounds of tumor challenge.

Supplemental Figure S5. Heat map of differentially expressed genes of interest in B2M KO versus PRDM1 KO samples after 1 or 5 rounds of serial tumor challenge.

Supplemental Figure S6. PRDM1 KO cells express lower levels of LAG3 than B2M KO cells after six cycles of tumor challenge.

Supplemental Figure S7. PRDM1 KO cells undergo less apoptosis than B2M KO control cells after six cycles of tumor challenge.

Supplemental Figure S8. PRDM1 KO and B2M KO GD2.CAR NKTs demonstrate similar levels of cytotoxic activity and granzyme B production after one round of tumor challenge.

Supplemental Figure S9. Weekly bioluminescence imaging of NB tumor growth described in Figure 2J.

Supplemental Figure S10. shRNA.PRDM1.GD2.CAR construct design.

Supplemental Figure S11. GD2.CAR+ percentage increases after six tumor challenge cycles in PRDM1 KD NKTs but not scrambled shRNA control (scr) NKTs.

Supplemental Figure S12. BLIMP1 levels in PRDM1 KD GD2.CAR NKTs prior to and after multiple rounds of tumor challenge.

Supplemental Figure S13. GD2.CAR NKTs with PRDM1 KD express lower levels of TIGIT and CD39 than scrambled control cells after six cycles of tumor challenge.

Supplemental Figure S14. PRDM1 KD cells undergo less apoptosis than scr control cells after six cycles of tumor challenge.

Supplemental Figure S15. GD2.CAR NKTs and scr control GD2.CAR NKTs have similar gene expression profiles after one and six cycles of tumor challenge.

Supplemental Figure S16. PRDM1 KD NKTs acquire a distinct gene expression profile from scr control cells after one and six cycles of serial tumor challenge.

Supplemental Figure S17. PRDM1 KO but not KD leads to significant reduction of NR4A1 expression versus control after multiple tumor challenge cycles.

Supplemental Figure S18. Tumor bioluminescence for individual mice from experiment in Figure 5A.

Supplemental Figure S19. Gating strategy to measure iNKT cell frequency in liver or spleen on mouse experiment described in Figure 5D.

Supplemental Figure S20. NKT cells are detected at significantly higher numbers in the spleens of mice treated with PRDM1 KD cells versus scr control cells.

Supplementary Table 1

Supplementary Table 2

Supplementary Table 3

Supplementary Table 4

Data Availability Statement

All requests for raw and analyzed data and materials beyond the information provided in the main text and supplementary figures should be directed to the corresponding author. These requests will be promptly reviewed by the BCM Licensing Group to verify whether the request is subject to any intellectual property or confidentiality obligations. Any data and materials that can be shared will be released via a Material Transfer Agreement. All raw RNA-seq data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE261930.