Abstract

Expression of eight transporter genes of Escherichia coli K-12 and its ΔacrAB mutant prior to and after induction of both strains to tetracycline resistance and after reversal of induced resistance were analyzed by quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR. All transporter genes were overexpressed after induced resistance with acrF being 80-fold more expressed in the ΔacrAB tetracycline-induced strain.

An organism responds to noxious agents present in its environment by altering the level of expression of those genes that favor survival and continued growth. Natural intrinsic resistance to these agents in gram-negative bacteria, that is, resistance not associated with any chromosomal mutation or the acquisition of extrachromosomal elements with resistance determinants, can be increased by preventing the antibiotic from entering the cell through the control of the permeability and by the effectiveness of efflux pumps present in the cell envelope that extrude one or more of these agents (15, 17, 21, 24). The permeability barrier alone does not produce significant antibiotic resistance because mutants with decreased expression of specific porins show only small increases in antibiotic resistance (17, 23, 24). Efflux transporters exist in limited numbers with fixed activity and accommodate the extrusion of these agents up to certain limits (15, 21). When the concentration exceeds the capacity of the pumps, the organism is at risk for survival. Escherichia coli has been shown to have at least nine intrinsic major different proton-dependent multidrug-resistant efflux pump systems (MDR pumps) that bestow resistance to two or more of these antimicrobial agents (15, 28). The genes coding for each of these efflux pumps are emrE (30), acrEF (formerly envCD) (12, 13, 31), emrAB (16), emrD (20), acrAB-TolC (8, 18, 19), mdfA (formerly cmr) (6, 25), tehA (35), acrD (an acrB homolog) (32), and yhiV (26). They belong to one of three genetically and structurally defined families: the major facilitator superfamily (MFS; emrD, mdfA, emrB), the resistance nodulation-cell division family (RND; acrB, acrF, acrD, yhiV), and the small multidrug resistance family (SMR; emrE, tehA) (15, 28).

The tripartite AcrAB-TolC system is the most well studied MDR pump system and consists of an inner-membrane efflux transporter (AcrB) that removes a large gamut of nonrelated antibiotics from the cytoplasm into the periplasm, where the linker protein (AcrA) directs the intermembrane transport of the antibiotic through the outer membrane channel (TolC) to the outside (8, 22). This type of genetic and structural organization is shared with its analog AcrEF, and their role has been assumed from the demonstration that acrAB or acrEF mutants are increasingly susceptible to a wide variety of antibiotics and detergents (12, 27, 34) and that these deletion mutants could be made significantly more resistant to these substances by the respective insertion of acrAB- or acrEF-carrying plasmids (2, 15, 26, 28). Although E. coli has been shown to have these intrinsic proton-dependent multidrug-resistant efflux pump systems, the specific activity of any one pump in its natural state and level has not yet been reported.

Bacteria initially susceptible to antibiotics have been made resistant by stepwise exposure to these compounds, and this resistance could be reversed by serial transfer to drug-free medium (9) or by exposure to inhibitors of efflux pumps (29, 36). The use of an E. coli K-12 strain whose genes that code for the main efflux pump AcrAB have been deleted (AG100A), together with its parental wild-type AG100 (9, 27), provided us the opportunity to study the expression, with the aid of the quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) (Table 1), of the nine multidrug-resistant efflux pump systems of E. coli, prior to and after inducing resistance to tetracycline by slow and gradual exposure to the antibiotic, and after the strains have reverted to the original tetracycline susceptibility of their respective parents.

TABLE 1.

Primers and conditions used in this studya

| Efflux transporter and housekeeping gene | Primer sequence (5′-3′)b | Length of amplicon (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| acrB | CGTACACAGAAAGTGCTCAA/CGCTTCAACTTTGTTTTCTT | 183 |

| acrD | GATTATCTTAGCCGCTTCAA/CAATGGAGGCTTTAACAAAC | 187 |

| acrF | TAGCAATTTCCTTTGTGGTT/CCTTTACCCTCTTTCTCCAT | 247 |

| emrB | ATTATGTATGCCGTCTGCTT/TTCGCGTAAAGTTAGAGAGG | 196 |

| emrD | TGTTAAACATGGGGATTCTC/TCAGCATCAGCAAATAACAG | 243 |

| emrE | GGATTGCTTATGCTATCTGG/GTGTGCTTCGTGACAATAAA | 156 |

| mdfA | TTTATGCTTTCGGTATTGGT/GAGATTAAACAGTCCGTTGC | 182 |

| tehA | TGCTTCATTCTGGAGTTTCT/TCATTCTTTGTCCTCTGCTT | 232 |

| yhiV | GCACTCTATGAGAGCTGGTC/CCTTCTTTCTGCATCATCTC | 203 |

| GAPDH | ACTTACGAGCAGATCAAAGC/AGTTTCACGAAGTTGTCGTT | 170 |

Amplification performed in separate tubes using the same amount of total RNA retrieved from the same sample. Thermal cycling conditions: reverse transcription at 50°C/30 min, PCR activation at 95°C/15 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation (94°C/60 s), annealing (51°C to 53°C/60 s depending on primers used), and extension (72°C/60 s). Primers were designed based on the sequence for the E. coli K-12 complete genome (accession number NC_000913) (1).

Forward primer sequences appear before the slash and reverse primer sequences appear after the slash.

The tetracycline-susceptible E. coli AG100 parent strain (MIC of 2.0 mg/liter determined by the broth macrodilution method) (7, 27) and its AG100A ΔacrAB insertion mutant progeny that is four times more susceptible to the antibiotic (MIC, 0.5 mg/liter) (Table 2) were induced by gradual stepwise increase of tetracycline to significant levels of resistance to the antibiotic (Fig. 1). Repeated serial transfer of these tetracycline-induced resistant strains to drug-free medium eventually restored the level of susceptibility to that initially present in the AG100 and AG100A strains after 40 and 110 days, respectively (Fig. 1).

TABLE 2.

MIC values of antibiotics and other agents known to be substrates of efflux pumps against E. coli AG100, AG100A (acrAB deleted), AG100TET, and AG100ATETa

| Agent | MIC (mg/liter)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AG100 | AG100A | AG100TET | AG100ATET | |

| Antibiotic | ||||

| TET | 2.0 | 0.5 | 12 | 12 |

| KAN | 15 | >200 | 10 | >200 |

| ERY | 100 | 6.25 | 100 | 100 |

| OFX | 0.12 | 0.015 | 0.48 | 0.48 |

| CIP | 0.03 | 0.004 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| CHL | 8 | 2 | >16 | >16 |

| PEN | 16 | 8 | 64 | 32 |

| OXA | 256 | 1 | >512 | >512 |

| Substrate | ||||

| SDS | >800 | 50 | >800 | >800 |

| RHO | >800 | 100 | >800 | >800 |

| TPP | 1,500 | 15 | 2,000 | 1,500 |

| BC | 15 | 2 | 15 | 15 |

| EB | 150 | 5 | >200 | >200 |

E. coli AG100TET and AG100ATET induced to tetracycline resistance by serial gradual and stepwise increase of tetracycline concentration as described in the text. Antibiotics: tetracycline (TET), kanamycin (KAN), erythromycin (ERY), ofloxacin (OFX), ciprofloxacin (CIP), chloramphenicol (CHL), penicillin (PEN), and oxacillin (OXA). Efflux pump substrates: sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), rhodamine (RHO), tetraphenylphosphodium bromide (TPP), benzalkonium chloride (BC), and ethidium bromide (EB).

FIG. 1.

Time course of induced tetracycline resistance of E. coli AG100 (solid circles) and AG100A (open triangles) strains and the reversal of induced resistance by transfer to drug-free medium. Strains were induced to tetracycline resistance (+TET) by serial transfer of inoculae from cultures that contained the highest concentration of the antibiotic under which the strains grew to media containing increasing concentrations of the drug and incubated until they yielded prominent evidence of growth. Reversal of resistance was induced by serial transfer to drug-free medium (-TET). MICs were periodically determined and confirmed in solid media by the tetracycline E-test (AB Biodisk, VIVA Diagnostica, Huerth, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

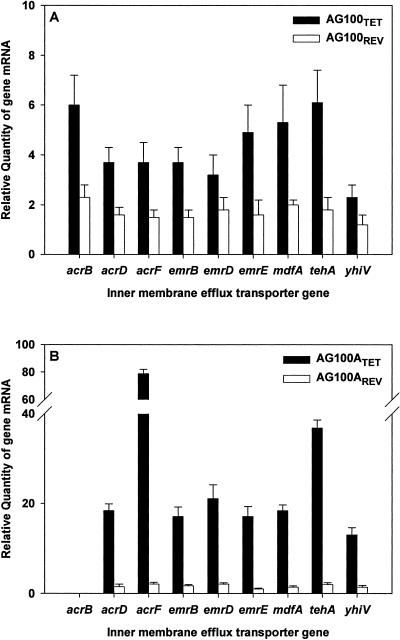

The relative quantities of the inner-membrane efflux transporter gene mRNA, isolated with the aid of an RNeasy Protect Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), of each of the nine major E. coli proton-dependent efflux pump systems were determined by the comparative threshold cycle (CT) method (14, 33) in a Rotor-Gene 2000 thermocycler with real-time analysis software (Corbett Research, Sydney, Australia) using a QuantiTect SYBR Green RT-PCR Kit (QIAGEN). The levels expressed by the wild-type E. coli AG100 and its ΔacrAB mutant prior to and after tetracycline resistance had been induced and reversed were determined for cultures in the presence of tetracycline concentrations immediately below the MIC for each strain. Firstly, direct comparison of the expression levels of the genes that code for the transporter proteins between E. coli AG100 and AG100A prior to exposure to tetracycline, with the exception of acrB which is not expressed in the ΔacrAB mutant, showed that the expression of the remaining eight genes is practically identical (data not shown). The relative expression levels of the transporter genes, after prolonged serial exposure of E. coli AG100 and AG100A strains to increasing concentrations of tetracycline and after reversal of resistance by transfer to drug-free medium (AG100REV and AG100AREV), are presented in Fig. 2. Tetracycline resistance induced in the wild-type AG100 strain (AG100TET) as well as in the ΔacrAB mutant (AG100ATET) results in the increased expression of all the efflux transporter genes over that expressed by either respective parental strain, an increase substantially higher in the deleted mutant (Fig. 2A and B). It is important to note that the acrF gene of the AG100ATET strain is markedly overexpressed (80-fold increase relative to the noninduced AG100A; Fig. 2B). Transfer of the induced tetracycline-resistant strains to drug-free medium eventually restored the expression of the inner-membrane efflux transporter genes to that of their respective noninduced parents (Fig. 2). However, restoration of susceptibility took place much faster for the wild-type AG100 (40 days) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 2.

Quantification of the expression level of the inner membrane efflux transporter genes of the nine major E. coli proton-dependent efflux pump systems in the tetracycline-induced resistant AG100TET and AG100ATET and the two strains after reversion of tetracycline resistance (AG100REV and AG100AREV,) relative to wild-type AG100 and the acrAB-deleted progeny AG100A, respectively. Gene transcript levels were normalized against the E. coli housekeeping gene GAPDH (coding for d-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) (3) measured in the same sample. Data are from three independent total mRNA extractions with corrections for standard deviation range.

The susceptibility of strains AG100, AG100A, AG100TET, and AG100ATET to a panel of antibiotics is described in Table 2. Briefly, with the exception of kanamycin (resistance insertion marker, ΔacrAB::Tn903 Kanr [27]), susceptibility of AG100A to all of the antibiotics of the panel is significantly greater than that demonstrated by the parental AG100 strain, confirming the studies of others (11, 27). The AG100A is also far more susceptible to sodium dodecyl sulfate, rhodamine 6G, tetraphenilphosphonium (TPP), benzalkonium chloride (BC), and ethidium bromide (EB), all of which have been identified as substrates of the AcrAB-TolC pump system (34). EB, TPP, and BC are also substrates of the MdfA (6), the EmrE (18, 30), and the TehA (35) MDR pump systems. The susceptibility of tetracycline-induced resistant strains AG100TET and AG100ATET to the panel of antibiotics tested, including β-lactams, with the exception of kanamycin, is significantly decreased, as shown by the data presented in Table 2. As a consequence of inducing tetracycline resistance, the initial differences in antibiotic susceptibility between AG100 and AG100A strains are essentially lost. It is important to note that the marked initial susceptibility of AG100A to the five efflux pump substrates tested is also lost subsequent to the inducing of tetracycline resistance (see Table 2).

Similarly, with respect to the effects of known inhibitors of bacterial efflux pumps on the growth of AG100, AG100A, and their tetracycline-induced resistant progeny, with the exception of reserpine, omeprazole, and carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP), AG100A is significantly more susceptible to verapamil (VP), Phe-Arg-napthylamide (MC-207,110) (PAN), thioridazine, and chlorpromazine than is the wild-type AG100, and this increased susceptibility is lost after it is induced to tetracycline resistance (Table 3). Overall, the response of the ΔacrAB tetracycline-induced resistant strain (AG100ATET) to antibiotics, substrates, and some of the inhibitors of efflux pumps is now similar to those of the wild-type AG100 strain. If the marked susceptibility of the AG100A strain to tetracycline is only related to the deletion of the acrAB genes, then known inhibitors of efflux pumps at concentrations proven not to affect growth should render the acrAB-intact AG100 strain as susceptible to tetracycline as the mutant. Of the inhibitors of efflux pumps tested (identified in Table 3), only CCCP and PAN reduced the MIC of tetracycline against AG100 from 2.0 to 0.5 mg/liter. In addition, PAN reduced the susceptibility of AG100 to erythromycin from 100 mg/liter to 3.13 mg/liter, nalidixic acid from 5 mg/liter to 2.5 mg/liter, oxacillin from 256 mg/liter to 64 mg/liter, chloramphenicol from 8 mg/liter to 2 mg/liter, and rhodamine from >800 mg/liter to 100 mg/liter. With respect to the effects of the above inhibitors on the susceptibility of the tetracycline-induced wild-type strain to tetracycline (AG100TET), only PAN reduced the susceptibility of this strain to that of its parental noninduced strain, i.e., from 12 to 0.5 mg/liter. None of the agents employed in this study altered the resistance to tetracycline of the ΔacrAB mutant tetracycline-adapted strain (AG100ATET).

TABLE 3.

MIC values for inhibitors of efflux pumps against AG100, AG100A (acrAB deleted), AG100TET, and AG100ATETa

| Inhibitors | MIC (mg/liter)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AG100 | AG100A | AG100TET | AG100ATET | |

| Calcium channel | ||||

| CPZ | 60 | 20 | 140 | 120 |

| TZ | 100 | 25 | >200 | 100 |

| RES | 140 | 140 | 100 | 100 |

| VP | >3,000 | 450 | >3,000 | >3,000 |

| Proton pumps | ||||

| OM | >2,500 | >2,500 | >2,500 | >2,500 |

| CCCP | 10 | 10 | 20 | 20 |

| PAN | >200 | 50 | >200 | >200 |

The maximum solubility in the medium for some of the agents was reached with no effect on growth. Hence the MIC was arbitrarily identified as “greater than.” Calcium channel inhibitors: chlorpromazine (CPZ), thioridazine (TZ), reserpine (RES), and verapamil (VP). Proton pump inhibitors: omeprazole (OM), carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP), and Phe-Arg-napthylamide (MC-207,110) (PAN).

In conclusion, both the wild-type E. coli AG100 and its acrAB-deleted mutant progeny, the latter far more sensitive to tetracycline, have the capacity to become increasingly resistant to tetracycline when exposure to tetracycline is gradually increased. The mechanism by which increased tolerance to tetracycline is brought about does not involve the selection of a mutation inasmuch as reversal to original tetracycline susceptibility could be obtained for both induced strains with their subsequent serial transfer to drug-free medium. The evaluation of genes that code for the inner-membrane transporter component of the nine efflux pumps studied shows that the deletion of the major AcrAB efflux pump is not essential for survival of E. coli as suggested by others (10) and is especially shown by the current study when the organism is grown under persistent tetracycline pressure. Because the acrF gene is markedly expressed by the acrAB-deleted mutant when continuously exposed to tetracycline, we conclude that the functions of the deleted AcrAB efflux pump are taken over by the AcrEF pump. Moreover, because PAN increases the sensitivity of the noninduced acrAB (AG100) and the tetracycline-induced resistant acrAB (AG100TET) whereas it has no effect on the acrAB-deleted mutant induced to the same level of tetracycline resistance (AG100ATET), we conclude that PAN is a specific inhibitor of the AcrAB pump and has no effect on the remaining efflux pumps that bestow resistance to tetracycline.

The approaches employed in this study reveal that efflux pumps play an important role in intrinsic resistance of E. coli to tetracycline—whose current chemotherapeutic use is limited due to the emergence of resistance (4, 5)—and that this intrinsic resistance can be increased by the overexpression and interplay of the different efflux pump genes present in the genome. The redundancy of at least nine efflux pumps, each one expressed to greater levels of activity when the organism is under antibiotic pressure, coupled to the demonstration that a single agent such as PAN inhibits only the AcrAB efflux pump, suggests that it may be rather difficult to find one agent that has the capacity to inhibit all of the efflux pumps of E. coli that bestow antibiotic resistance to the organism.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant EU-FSE/FEDER-POCTI-37579/FCB/2001 provided by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) of Portugal. M. Martins was supported by grant SFRH/BD/14319/2003 from Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, Portugal.

We would like to thank the Cost Action B16 “Reversal of antibiotic resistance by the inhibition of efflux pumps” of the European Commission for advice and recommendations during the course of this study and the Quilaban Company and Corbett Research for the use of the Rotor-Gene 2000 thermocycler. We also are indebted to the Virology Unit from IHMT for the fruitful discussions. A special thank you to Isabel Couto for her review of the manuscript and critical comments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blattner, F. R., G. Plunkett, C. A. Bloch, N. T. Perna, V. Burland, M. Riley, J. Collado-Vides, J. D. Glasner, C. K. Rode, G. F. Mayhew, J. Gregor, N. W. Davis, H. A. Kirkpatrick, M. A. Goeden, D. J. Rose, B. Mau, and Y. Shao. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277:1453-1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borges-Walmsley, M. I., K. S. McKeegan, and A. R. Walmsley. 2003. Structure and function of efflux pumps that confer resistance to drugs. Biochem. J. 376:313-338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Branlant, G., and C. Branlant. 1985. Nucleotide sequence of the Escherichia coli gap gene. Different evolutionary behavior of the NAD+-binding domain and of the catalytic domain of d-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Eur. J. Biochem. 150:61-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chopra, I. 2002. New developments in tetracycline antibiotics: glycylcyclines and tetracycline efflux pump inhibitors. Drug Resist. Updat. 5:119-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chopra, I., and M. Roberts. 2001. Tetracycline antibiotics: mode of action, applications, molecular biology, and epidemiology of bacterial resistance. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 65:232-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edgar, R., and E. Bibi. 1997. MdfA, an Escherichia coli multidrug resistance protein with an extraordinarily broad spectrum of drug recognition. J. Bacteriol. 179:2274-2280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eliopoulos, G. M., and R. C. Moellering. 1991. Antimicrobial combinations, p. 330-396. In V. Lorian (ed.), Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. Williams and Wilkins Co., Baltimore, Md.

- 8.Fralick, J. A. 1996. Evidence that TolC is required for functioning of the Mar/AcrAB efflux pump of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 178:5803-5805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.George, A. M., and S. B. Levy. 1983. Amplifiable resistance to tetracycline, chloramphenicol, and other antibiotics in Escherichia coli: involvement of a non-plasmid-determined efflux of tetracycline. J. Bacteriol. 155:531-540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirata, T., A. Saito, K. Nishino, N. Tamura, and A. Yamaguchi. 2004. Effects of efflux transporter genes on susceptibility of Escherichia coli to tigecycline (GAR-936). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:2179-2184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jellen-Ritter, A. S., and W. V. Kern. 2001. Enhanced expression of the multidrug efflux pumps AcrAB and AcrEF associated with insertion element transposition in Escherichia coli mutants selected with a fluoroquinolone. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1467-1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawamura-Sato, K., K. Shibayama, T. Horii, Y. Iimuma, Y. Arakawa, and M. Ohta. 1999. Role of multiple efflux pumps in Escherichia coli in indole expulsion. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 179:345-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein, J. R., B. Henrich, and R. Plapp. 1991. Molecular analysis and nucleotide sequence of the envCD operon of Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet. 230:230-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langmann, T., R. Mauerer, A. Zahn, C. Moehle, M. Probst, W. Stremmel, and G. Schmitz. 2003. Real-time reverse transcription-PCR expression profiling of the complete human ATP-binding cassette transporter superfamily in various tissues. Clin. Chem. 49:230-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li, X. Z., and H. Nikaido. 2004. Efflux-mediated drug resistance in bacteria. Drugs 64:159-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lomovskaya, O., and K. Lewis. 1992. emr, an Escherichia coli locus for multidrug resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:8938-8942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma, D., D. N. Cook, J. E. Hearst, and H. Nikaido. 1994. Efflux pumps and drug resistance in gram-negative bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2:489-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma, D., D. N. Cook, M. Alberti, N. G. Pon, H. Nikaido, and J. E. Hearst. 1995. Genes acrA and acrB encode a stress-induced efflux system of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 16:45-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma, D., D. N. Cook, M. Alberti, N. G. Pon, H. Nikaido, and J. E. Hearst. 1993. Molecular cloning and characterization of acrA and acrE genes of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 175:6299-6313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naroditskaya, V., M. J. Schlosser, N. Y. Fang, and K. Lewis. 1993. An E. coli gene emrD is involved in adaptation to low energy shock. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 196:803-809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nikaido, H. 2001. Preventing drug access to targets: cell surface permeability barriers and active efflux in bacteria. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 12:215-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nikaido, H., and H. I. Zgurskaya. 2001. AcrAB and related multidrug efflux pumps of Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 3:215-218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nikaido, H. 1994. Prevention of drug access to bacterial targets: permeability barriers and active efflux. Science 264:382-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nikaido, H. 2003. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67:593-656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nilsen, I. W., I. Bakke, A. Vader, O. Olsvik, and M. R. El-Gewely. 1996. Isolation of cmr, a novel Escherichia coli chloramphenicol resistance gene encoding a putative efflux pump. J. Bacteriol. 178:3188-3193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nishino, K., and A. Yamaguchi. 2001. Analysis of a complete library of putative drug transporter genes in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:5803-5812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okusu, H., D. Ma, and H. Nikaido. 1996. AcrAB efflux pump plays a major role in the antibiotic resistance phenotype of Escherichia coli multiple-antibiotic-resistance (Mar) mutants. J. Bacteriol. 178:306-308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paulsen, I. T. 2003. Multidrug efflux pumps and resistance: regulation and evolution. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6:446-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piddock, L. J. 1999. Mechanisms of fluoroquinolone resistance: an update 1994-1998. Drugs 58:11-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Purewal, A. S. 1991. Nucleotide sequence of the ethidium efflux gene from Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 66:229-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodolakis, A., P. Thomas, and J. Starka. 1973. Morphological mutants of Escherichia coli. Isolation and ultrastructure of a chain-forming envC mutant. J. Gen. Microbiol. 75:409-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenberg, E. Y., D. Ma, and H. Nikaido. 2000. AcrD of Escherichia coli is an aminoglycoside efflux pump. J. Bacteriol. 182:1754-1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Su, Y. R., M. F. Linton, and S. Fazio. 2002. Rapid quantification of murine ABC mRNAs by real time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. J. Lipid Res. 43:2180-2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sulavik, M. C., C. Houseweart, C. Cramer, N. Jiwani, N. Murgolo, J. Greene, B. DiDomenico, K. J. Shaw, G. H. Miller, R. Hare, and G. Shimer. 2001. Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of Escherichia coli strains lacking multidrug efflux pump genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1126-1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Turner, R. J., D. E. Taylor, and J. H. Weiner. 1997. Expression of Escherichia coli TehA gives resistance to antiseptics and disinfectants similar to that conferred by multidrug resistance efflux pumps. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:440-444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Viveiros, M., I. Portugal, R. Bettencourt, T. C. Victor, A. M. Jordaan, C. Leandro, D. Ordway, and L. Amaral. 2002. Isoniazid-induced transient high-level resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2804-2810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]