Abstract

Several factors have contributed to poor quality of life outcomes for upper-extremity amputees. In recent decades, the advancements in both surgical procedures and prosthetics have been aimed at both improving the function and quality of life of amputees. Targeted muscle reinnervation, regenerative peripheral nerve interfaces, agonist–antagonist myoneural interfaces, free tissue transfers, and limb transplantation are chief among the surgical options available for improved sensorimotor function in residual and prosthetic limbs. New technologies such as cuff electrodes, intraneural filaments, and various osseointegrated prosthesis systems are used either alone or in concert with these operative techniques. Procedural and technological advancements will continue to push the limits of functional restoration after upper-extremity limb loss.

Key words: Free tissue transfer, Osseointegration, Regenerative peripheral nerve interfaces, Targeted muscle reinnervation, Upper-extremity amputation

In the United States alone, over half a million people are living with an upper-extremity amputation, with estimates that this number will more than double by the year 2050.1 Most of these amputations are traumatic in nature, with major limb amputation defined as those occurring through or proximal to the radiocarpal joint.2 This is in contrast to lower-extremity amputations, which are largely attributed to vascular disease.1,3 Given improvements in microsurgery, many previously unrepairable injuries can be treated with limb replantation, with favorable long-term outcomes.4, 5, 6 Although replantation may be the gold standard and result in improved patient reported outcomes, many patients are either not candidates or have failed attempts at replantation.7

As a result, over the past two decades there have been considerable advancements in both surgical procedures and prosthetics aimed at improving the function and quality of life for those living with amputations. These advancements include targeted muscle reinnervation (TMR), regenerative peripheral nerve interfaces (RPNI), sensory implants, osseointegration, free flaps to preserve limb length, and limb transplantation, among others. This article will explore these techniques with the aim of understanding current advancements and when each may be indicated for patients.

TMR/RPNI for Prosthesis Control

Prosthetic rehabilitation after upper-extremity amputation is difficult given the complex and fine motor movements of the innate arm/hand. Body-powered prostheses were originally developed by Peter Baliff and used shoulder and trunk muscles as power sources to control a hand.8 Although still used today given the affordability and durability, the major limitation with body-powered prostheses is that the user has limited joint movements and degrees-of-freedom (DOFs). In the mid-1950s, the modern myoelectric prosthesis was developed by using EMG signals from intact muscles to power the prosthesis.9 Historically, this was performed by using the difference in EMG signals between antagonistic muscle groups (eg, biceps and triceps) to power a single joint movement (eg, elbow flexion/extension). To power a separate movement, such as hand closure, the user would have to operate an inconvenient and slow switching mechanism.10

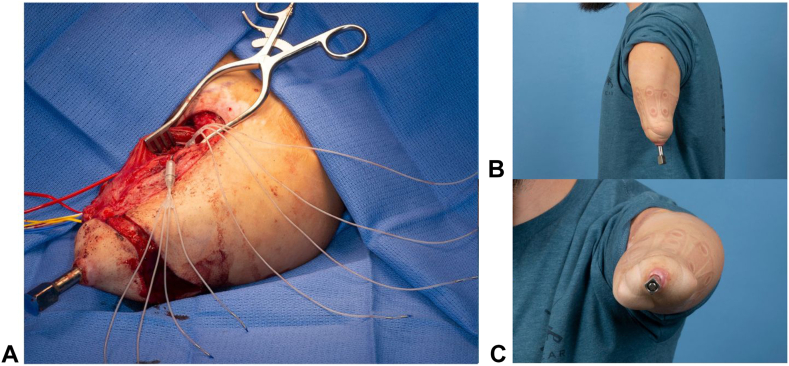

Targeted muscle reinnervation (TMR) is a surgical procedure that was developed to improve the control of myoelectric prostheses. First developed and performed by Dr. Gregory Dumanian and Dr. Todd Kuiken at Northwestern University, this procedure takes cut nerve endings formed at the time of amputation and reroutes them into adjacent redundant motor nerves to create new myoelectric signals.11 The target muscles are reinnervated in approximately 8–12 weeks, and the EMG signals are strong enough for myoelectric control in 3–4 months.10 The new signals enable a wider array of functions and DOFs in the prosthesis, making control more intuitive. For example, in a transhumeral amputee, a segment of biceps can be reinnervated by the median nerve and thus generate a signal for hand closure (Fig. 1). Through pattern recognition, EMG signals are measured from sets of residual limb muscles, and using machine learning, translated into movements with multiple DOFs, improving controllability.10 Although first used in a patient with shoulder disarticulation, TMR has now been employed at all levels of amputation in the upper extremity (Fig. 2). Numerous studies consistently demonstrate significant improvements in prosthesis motor function, comfortability, and quality of life following TMR.10,12, 13, 14, 15, 16

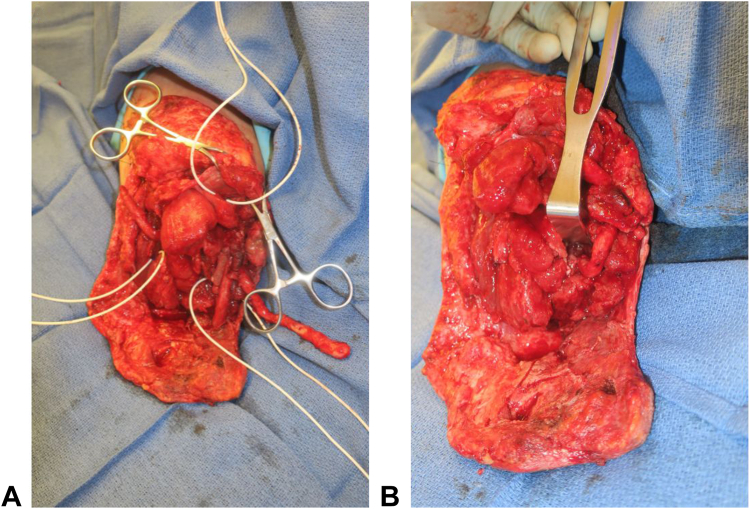

Figure 1.

Intraoperative photos of A tagged motor nerve targets for TMR and B coapted TMR after a transhumeral amputation.

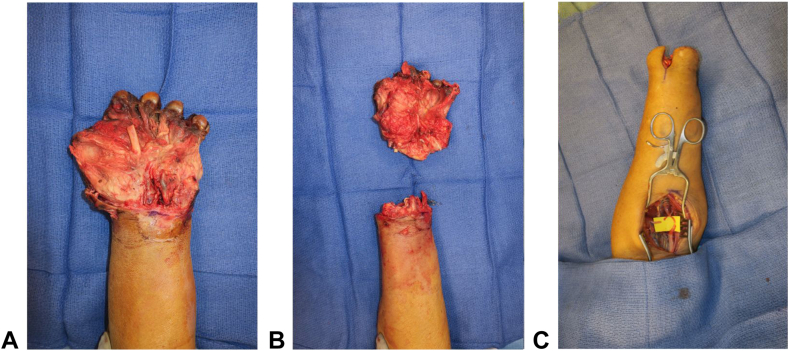

Figure 2.

Intraoperative photos of A a nonsalvageable hand requiring B transradial amputation and C acute TMR.

A distinct yet conceptually similar procedure to TMR is the RPNI, which takes amputated nerve endings and attaches them to denervated muscle grafts. Unlike TMR, the muscle target is small and is both denervated and devascularized. It can be taken from the residual limb or another part of the body and transferred to the site of the transected nerve. The muscle graft is wrapped around the end of the nerve, and over time, is reinnervated, and revascularized, which takes around 3 months.17,18 RPNI was similarly developed to enhance peripheral nerve signals for myoelectric prosthesis control, with the added benefit of increased specificity given the ability to generate multiple RPNIs by separating terminal nerves into individual fascicles.19 Rat and rhesus monkey models have demonstrated the successful creation of RPNIs with strong, reliable EMG signals that can control neuroprosthetic hands.20, 21, 22 More recently, studies in humans have similarly shown promising results of the use of RPNIs for prosthetic hand control.23,24 The first pilot study conducted at the University of Michigan analyzed four patients with upper-extremity amputations and RPNIs. Patient 1 had four RPNIs created on the median nerve, three on the ulnar, and two on the radial. The result was that independent contractions were observed for thumb interphalangeal (IP) flexion, index distal interphalangeal (DIP) flexion, and index proximal interphalangeal (PIP) flexion, highlighting the enhanced specificity of signals for improved voluntary control of a prosthetic hand.23

Although both surgical treatments will likely play a key role in the future of prosthetic control, a few stated advantages of RPNI over TMR include (1) no need for partial denervation of the target muscle, especially if using a muscle graft taken from tissue of the amputated limb; (2) increased specificity of signals because RPNIs can be created on a fascicular level, and (3) the use of implanted electrodes instead of surface electrodes for recording EMGs, which will limit signal interference.19 Conversely, disadvantages include (1) potential for muscle graft atrophy given that it must be reinnervated and revascularized; (2) potential for implanted electrode shifting/dislodgement; and (3) lack of long-term and large sample size studies in humans to validate results.

TMR/RPNI for Neuroma and Phantom Limb Pain

Up to 76%–85% of patients with limb amputations experience residual limb pain and phantom limb pain, respectively.25, 26, 27 Neuromas are the causative agent in residual limb pain or pain at the stump ending. Phantom limb pain is thought to be attributed to an interplay between peripheral nerves and central cortical restructuring.28 Both entities have shown to cause measurable decreases in quality of life. Although TMR was initially developed for improved myoelectric prosthesis control, it was soon discovered that this procedure helped with patients’ residual limb and phantom limb pain. In 2014, these positive results were published in a multicenter retrospective review of 26 patients.29 Animal studies showed that by giving the nerve a new target to innervate, or “somewhere to go and something to do,” TMR restored the native myelinated nerve histology.30 Subsequently, a prospective, randomized controlled trial was conducted of 28 amputees who were assigned to standard neuroma treatment (excision and burying in muscle) versus TMR. Results demonstrated that at 1 year after surgery, TMR significantly reduced phantom limb pain scores (P = .03) and approached significance for reduction in residual limb pain scores (P = .10) compared to standard treatment.31 Although these two studies demonstrated the use of TMR for treatment of pain, the idea that it could be preventative was born. More recent data have shown that early TMR (at the time of amputation) significantly reduces residual limb and phantom limb pain compared to controls.32 This is a large step towards improved quality of life for amputees.

RPNI has also been used for neuroma treatment (Fig. 3) and has demonstrated favorable results in limited studies. Histologic analysis of RPNI constructs show the absence of neuroma formation, axonal sprouting, and reinnervation of the RPNI muscle graft with formation of new neuromuscular junctions.17 In a pilot study of 16 upper and lower-extremity amputees, patients reported a 71% reduction in neuroma pain and 53% reduction in phantom limb pain following RPNI surgery.33 Similar to early TMR, RPNI performed at the time of amputation has shown good outcomes. A retrospective study of 45 patients who underwent prophylactic RPNI at the time of amputation compared to matched controls demonstrated significant decreased rates of symptomatic neuromas (0% vs 13.3%, P = .026) and phantom limb pain (51.1% vs 91.1%, P < .0001).34 However, this still demonstrates a 50% rate of phantom limb pain with this procedure. A unique setting where RPNI may be the only option is in distal amputations, such as the hand, or digital level, where no muscular targets exist for TMR. In this setting, RPNI has been successful at treating symptomatic neuromas.35

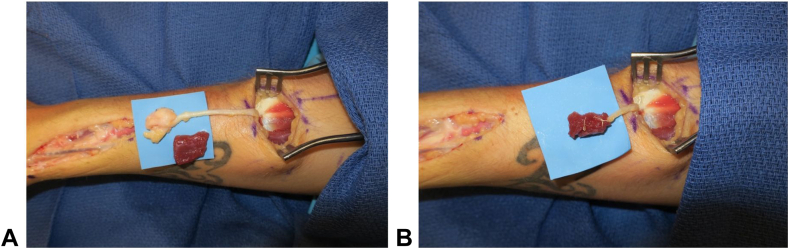

Figure 3.

Intraoperative photos showing a radial sensory neuroma treated with RPNI A before and B after excision and muscle wrapping.

Sensory Feedback

To allow for optimal control of a prosthetic limb, the interface must not only allow for efferent motor output, but also afferent sensory input. Lack of sensory input has been cited as a reason for prosthesis rejection.36 Following TMR, it was noted that not only did the target muscle undergo motor reinnervation, but the skin overlying the muscle underwent sensory reinnervation. Kuiken et al. tested this sensory recovery in two patients with proximal upper limb amputations following TMR of the residual brachial plexus nerves to the pectoralis major and serratus anterior. They showed that touching the reinnervated chest skin was perceived as touch in the patients’ amputated hand. Additionally, temperature, pain, and some proprioceptive information was elicited.37 Detection of pressure was similar to pressure sensation of native skin.38 As such, this operation allows for bidirectional motor and sensory signals from one construct. The issue, however, is that simultaneous motor and sensory control may be impeded because of sensory gating, or interruption of efferent signals because of afferent signals at the same site.39

Various sensory implants are currently undergoing investigation. These implants range from cuff electrodes wrapped around the end of a nerve to intraneural filaments that are directly inserted into a peripheral nerve. These devices have shown promise in multiple studies but are limited by lack of selectivity (cuff electrodes) or lack of longevity because of damage and scarring of nerve endings (intraneural filaments).40, 41, 42 RPNI provides another modality for bidirectional control that allows for indirect nerve stimulation given the muscle graft layer. This may increase longevity and prevent prior concerns about damage to the peripheral nerve ending. Vu et al43 have showed in two patients with upper-extremity amputations that stimulation of their RPNIs yielded proprioceptive and cutaneous sensory feedback in their phantom hand. Future investigations include using composite RPNIs (C-RPNIs), a construct composed of a dermal graft and muscle graft secured to a target mixed sensorimotor nerve, to separate motor, and sensory reinnervation. By stimulating the dermal component, the user can receive sensory input without interfering with efferent output, potentially allowing for more seamless prosthetic control.44 Agonist–antagonist myoneural interfaces (AMIs) are biomechanical constructs designed to improve proprioceptive feedback and volitional control of a prosthesis after limb amputation. Constructs can be formed using innervated, vascularized muscle pairs such as in the initial use of AMI for a below-knee amputation where the tibialis anterior and lateral gastrocnemius were coupled.45 TMR and RPNI can also be implemented in a regenerative AMI construct. For an above elbow amputation, a regenerative AMI emulator of wrist flexion/extension was created using muscles that had been used as median and radial nerve TMR targets.46 Additional upper- extremity amputation applications are currently under investigation.

Osseointegration

Osseointegration (OI), the direct skeletal attachment of a prosthesis to bone, represents another surgical modality for improved prosthetic use. Developed by Per Ingvar Brånemark in the 1960s, the idea was first introduced for titanium dental implants.47 This was subsequently adapted for use in major limb amputations by his son, Rickard Brånemark. Through hundreds of procedures, Brånemark has worked to standardize the procedure, implant design, and rehabilitation protocol named Osseointegrated Prostheses for the Rehabilitation of Amputees (OPRA).48 Four other implant systems are currently in clinical use including the Osseointegrated Prosthesis Limb (Permedica), the Integral Leg Prosthesis (ESKA Orthopaedic), the Percutaneous Osseointegrated Prosthesis (University of Utah clinical trials), and the Compress (Zimmer Biomet) transcutaneous implant.49 Each system differs in its overall design, length, diameter, contact with the medullary canal, connection of the abutment that exits the skin to the metal stem, and ability to be placed in one or two stages.11 However, the overall goal is the same: to improve the user-prosthesis interface through direct skeletal attachment.

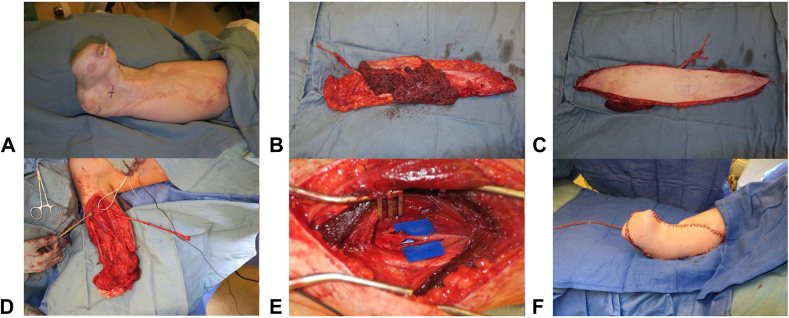

Conventional socket and liner based constructs for prostheses are wrought with complications including pain, skin breakdown, ill-fitting interface, increased time/difficulty donning and doffing the device, and decreased prosthesis control.11,49 Consequently, up to 35% of upper limb amputees abandon their prostheses.50 Through direct skeletal contact, OI avoids the soft tissue intermediary of socket prostheses and enables improved control, ease of use, mobility, and decreased energy expenditure (Fig. 4).51,52 Moreover, vibratory and mechanical sensation is enhanced through direct stimulation of the bone, termed osseoperception, which improves feedback, and thus control.53 Ultimately, an increased quality of life has been reported with OI.54 Advancements in sensorimotor integration with OI for improved prosthesis control and function are currently being studied. Clinical trials looking at implanted electrodes using the enhanced OPRA (e-OPRA) system have demonstrated promising results in upper limb amputees, with more reliable and precise motor control (Fig. 5).55,56

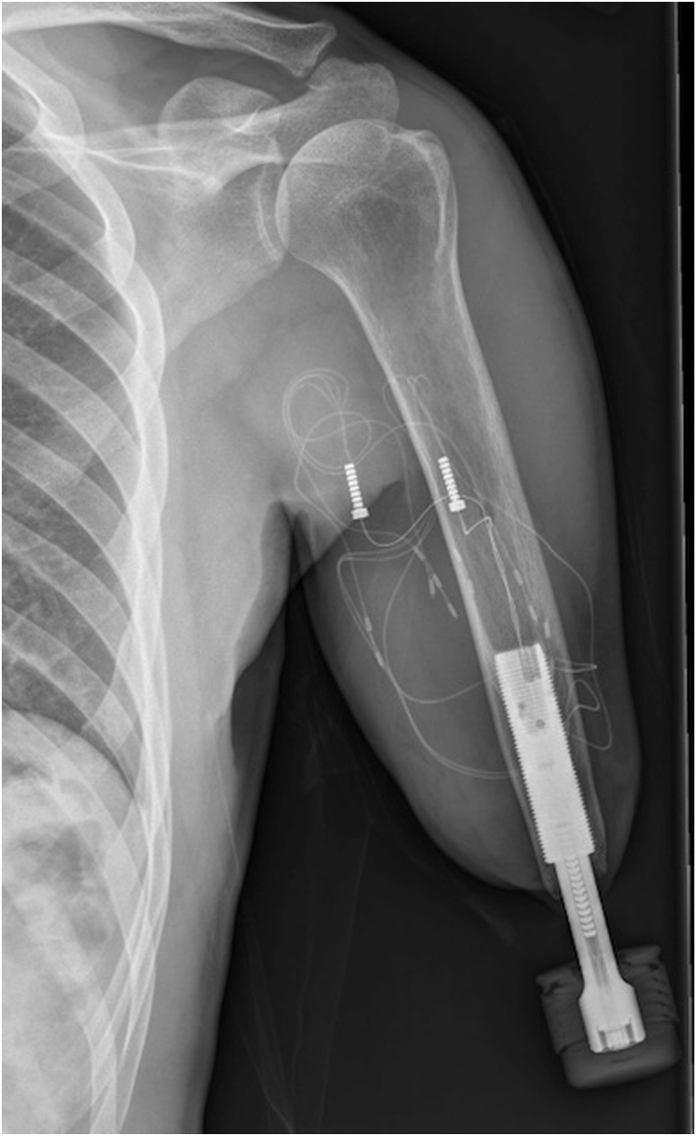

Figure 4.

Radiographic image of the e-OPRA system after implantation.

Figure 5.

Photos of the e-OPRA system A intraoperatively with associated intramuscular and intraneural electrodes allowing for bidirectional sensorimotor integration between the prosthesis and the patient and B,C after surgery.

The main challenge with OI remains prevention of superficial soft tissue infection at the device–skin interface, with rates reported from 30% to 66%.57, 58, 59 The nature of a foreign object that directly communicates from the outside world to the intramedullary canal creates a challenge for limiting bacterial translocation. Luckily, the 10-year cumulative risk of deep infection remain less than 10%.60 Future advancements in management of the soft tissue envelope and tissue engineering to create a “dermal seal” at the device interface may help combat these challenges.49

Free Tissue Transfer to Optimize Residual Limb Length and Provide Targets for TMR

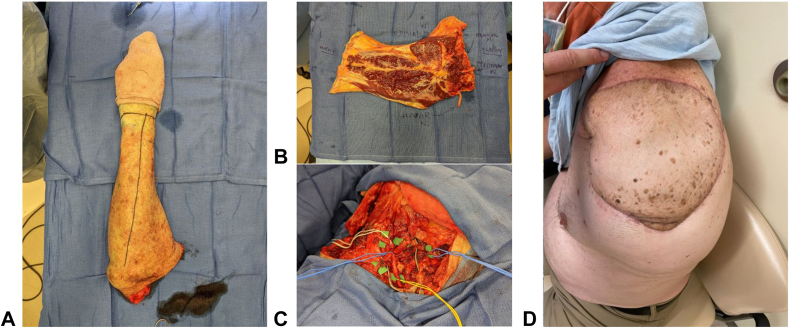

Traumatic and oncologic amputations of the upper extremity can occur at any level and often present a reconstructive challenge when replantation is not possible. Preserving skeletal length and critical joints is ideal for optimizing the function of the residual limb. The “spare parts” concept uses tissue from the amputated portion of the limb that would otherwise go to waste to reconstruct the limb. The classic fillet flap is defined as an axial pattern flap harvested from the amputated or discarded tissue that can be taken as a pedicled, island or free flap (Fig. 6).61 This technique has been used in both upper and lower-extremity reconstruction for preservation of limb length.61, 62, 63, 64, 65 The main benefit is the avoidance of additional donor site morbidity. However, in cases where the amputated tissues have been too traumatized, or when ischemia time is too long, free tissue transfer from other donor sites must be entertained. The benefit of additional limb length and joint function must be weighed against the donor site morbidity of a distant free flap. In a series of 13 patients, Baccarani et al66 outline the indications for the use of traditional (nonfillet) free flaps for preservation of upper limb amputation level. Major indications include preservation of the shoulder and elbow joints, pinch function (converting wrist articulation or transcarpal amputation to phalanx amputation), and skeletal length > 7 cm below the shoulder or elbow (which significantly improves prosthetic fit and function) (Fig. 7). Minor indications included preservation of the wrist joint for prosupination and skeletal length between 5 and 7 centimeters (5 being the minimum length for fitting a prosthesis). The series demonstrates successful outcomes with the use of various free flaps, including fillet, anterolateral thigh (ALT), latissimus, parascapular, and fibula, for salvage of upper limb joints and length. Although acknowledging that these scenarios are fairly rare and more often free tissue is harvested from the discarded limb, the authors propose a treatment algorithm that can be used for optimizing the function of the residual limb.

Figure 6.

Free fillet flap used in a forequarter amputation showing A the amputated upper extremity, B precoaptation, C flap inset, and D postoperative result.

Figure 7.

Intraoperative photos of a transradial amputation residual limb length preservation surgery using a free ALT flap showing A the pre-flap residual upper extremity; B,C the ALT free flap after harvest; D the prepared residual upper limb; E TMR; and F final flap inset.

In addition to preserving skeletal length, free tissue transfers can also be used as targets for TMR when local tissue is unavailable. Particularly in the case of forequarter amputation when the pectoralis major, serratus, and latissimus may be taken or damaged, free muscle/musculocutaneous flaps can be used for both soft tissue coverage and as nerve targets. There have been successful case reports of using a free volar forearm fillet flap for coverage and TMR after forequarter amputation secondary to tumor resection.67,68 Nerve coaptations were performed from the trunks of the brachial plexus to the radial, ulnar, and median nerves within the flap. In delayed reconstructions when the amputated limb is not available, successful case reports of using a free vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneous and free contralateral serratus for TMR targets after forequarter amputation have been demonstrated.69,70 Overall, the hand surgeon has a wide array of tools for preserving the function of the residual limb through the use of native tissues, and when combined with prosthetics, can significantly improve quality of life for patients.

Limb Transplantation

Despite the aforementioned advancements in surgical techniques, prosthetics will likely never outperform the functions of the native upper limb. In cases where replantation is not possible, another solution is limb vascularized composite allotransplantation (VCA). Hand transplantation was first attempted in 1964 in Ecuador, and although technically successful, failed because of insufficient immunosuppression.71 Subsequently, since 1998 there have been over 100 upper limb transplantations performed, the majority occurring the United States.72 Although the indications are somewhat debated, the best candidates have attempted prosthetic rehabilitation, understand the risks involved, are highly motivated and willing to comply with postoperative immunosuppression and rehabilitation, and desire improved function (both motor and protective sensation) and aesthetics.73 Although many unilateral hand transplants have been performed successfully, Mathes et al74 reported that most North American hand surgeons believe bilateral below-elbow amputation is the most appropriate indication for transplantation. This is because (1) unilateral amputees can still perform approximately 90% of their activities of daily living with their remaining native hand and (2) more distal amputations retain native forearm muscles and tendons often allowing for immediate extrinsic control and require a shorter distance for nerve regeneration for recovery of protective sensation and intrinsic function.75,76

Functional outcomes have been overwhelmingly positive. A systematic review by Wells et al72 noted a significant decrease in disability scores (measured by the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand [DASH] score) following transplant, with greater improvements in more distal transplants. Moreover, the majority recover protective sensation as measured by two-point discrimination and Semmes–Weinstein monofilament testing.73 High allograft survival is also noted, with a rate of 89.2% at 10 years, compared with kidney (73.6%), liver (63%), and heart (53%) transplants.77, 78, 79 The main challenges remain transplant rejection, infection, and other medical side effects of chronic immunosuppression such as kidney failure. The literature suggests that the rates of these are comparable or superior to other solid organ transplants, but they remain serious considerations when counseling patients on the risks and benefits of allotransplantation. With continued improvements in immunosuppressive regimens, modalities to enhance nerve regeneration, and postoperative rehabilitation, upper-extremity transplantation will likely become a more ubiquitous reconstructive option.

Conclusion

Upper-extremity limb loss is a devastating event that significantly affects patients’ function and quality of life. Advancements in surgical techniques and prosthetics including TMR, RPNI, osseointegration, myoelectric prosthetics, free tissue transfer for limb length and TMR, and VCA have expanded our ability to restore some of this function for our patients. Continued improvements in these techniques, along with newer developments like AMIs and haptics for sensation, will strengthen our toolkit for functional restoration of the upper limb.

Conflicts of Interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received related directly to this article.

References

- 1.Ziegler-Graham K., MacKenzie E.J., Ephraim P.L., Travison T.G., Brookmeyer R. Estimating the prevalence of limb loss in the United States: 2005 to 2050. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:422–429. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dillingham T.R., Pezzin L.E., MacKenzie E.J. Limb amputation and limb deficiency: epidemiology and recent trends in the United States. South Med J. 2002;95(8):875–883. doi: 10.1097/00007611-200208000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaine W.J., Smart C., Bransby-Zachary M. Upper limb traumatic amuptees: review of prosthetic use. J Hand Surg Br. 1997;22(1):73–76. doi: 10.1016/s0266-7681(97)80023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prucz R.B., Friedrich J.B. Upper extremity replantation: current concepts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133(2):333–342. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000437254.93574.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gülgönen A., Ozer K. Long-term results of major upper extremity replantations. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2012;37(3):225–232. doi: 10.1177/1753193411427228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ng W.K., Kaur M.N., Thoma A. Long-term outcomes of major upper extremity replantations. Plast Surg (Oakv) 2014;22(1):9–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pet M.A., Morrison S.D., Mack J.S., et al. Comparison of patient-reported outcomes after traumatic upper extremity amputation: replantation versus prosthetic rehabilitation. Injury. 2016;47(12):2783–2788. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ham R., Cotton L. In: Limb Amputation. Theory in Practice. 1st ed. Campling J., editor. Springer Nature; 1991. The history of amputation surgery and prosthetics; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 9.González-Fernández M. Development of upper limb prostheses: current progress and areas of growth. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95(6):1013–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hargrove L.J., Miller L.A., Turner K., Kuiken T.A. Myoelectric pattern recognition outperforms direct control for transhumeral amputees with targeted muscle reinnervation: a randomized clinical trial. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14386-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mioton L.M., Dumanian G.A. Targeted muscle reinnervation and prosthesis rehabilitation after limb loss. J Surg Onc. 2018;118(5):807–814. doi: 10.1002/jso.25256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuiken T.A., Dumanian G.A., Lipschutz R.D., Miller L.A., Stubblefield K.A. The use of targeted muscle reinnervation for improved myoelectric prosthesis control in a bilateral shoulder disarticulation amputee. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2004;28(3):245–253. doi: 10.3109/03093640409167756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuiken T.A., Miller L.A., Lipschutz R.D., et al. Targeted reinnervation for enhanced prosthetic arm function in a woman with a proximal amputation: a case study. The Lancet. 2007;369(9559):371–380. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oʼshaughnessy K.D., Dumanian G.A., Lipschutz R.D., Miller L.A., Stubblefield K., Kuiken T.A. Targeted reinnervation to improve prosthesis control in transhumeral amputees: a report of three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(2):393–400. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuiken T.A., Li G., Lock B.A., et al. Targeted muscle reinnervation for real-time myoelectric control of multifunction artificial arms. JAMA. 2009;301(6):619–628. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simon A.M., Turner K.L., Miller L.A., et al. Myoelectric prosthesis hand grasp control following targeted muscle reinnervation in individuals with transradial amputation. PLoS One. 2023;18(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0280210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kung T.A., Langhals N.B., Martin D.C., Johnson P.J., Cederna P.S., Urbanchek M.G. Regenerative peripheral nerve interface viability and signal transduction with an implanted electrode. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133(6):1380–1394. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Urbanchek M.G., Baghmanli Z., Moon J.D., Sugg K.B., Langhals N.B., Cederna P.S. Quantification of regenerative peripheral nerve interface signal transmission. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130(5S-1):55–56. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar N.G., Kung T.A., Cederna P.S. Regenerative peripheral nerve interfaces for advanced control of upper extremity prosthetic devices. Hand Clin. 2021;37(3):425–433. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2021.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Urbanchek M.G., Kung T.A., Frost C.M., et al. Development of a regenerative peripheral nerve interface for control of a neuroprosthetic limb. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/5726730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frost C.M., Ursu D.C., Flattery S.M., et al. Regenerative peripheral nerve interfaces for real-time, proportional control of a neuroprosthetic hand. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2018;15(1):108. doi: 10.1186/s12984-018-0452-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Irwin Z.T., Schroeder K.E., Vu P.P., et al. Chronic recording of hand prosthesis control signals via a regenerative peripheral nerve interface in a rhesus macaque. J Neural Eng. 2016;13(4) doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/13/4/046007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vu P.P., Vaskov A.K., Irwin Z.T., et al. A regenerative peripheral nerve interface allows real-time control of an artificial hand in upper limb amputees. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12(533) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aay2857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vu P.P., Vaskov A.K., Lee C., et al. Long-term upper-extremity prosthetic control using regenerative peripheral nerve interfaces and implanted EMG electrodes. J Neural Eng. 2023;20(2) doi: 10.1088/1741-2552/accb0c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ephraim P.L., Wegener S.T., MacKenzie E.J., Dillingham T.R., Pezzin L.E. Phantom pain, residual limb pain, and back pain in amputees: results of a national survey. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(10):1910–1919. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ehde D.M., Czerniecki J.M., Smith D.G., et al. Chronic phantom sensations, phantom pain, residual limb pain, and other regional pain after lower limb amputation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(8):1039–1044. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2000.7583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsu E., Cohen S.P. Postamputation pain: epidemiology, mechanisms, and treatment. J Pain Res. 2013;6:121–136. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S32299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flor H., Elbert T., Knecht S., et al. Phantom-limb pain as a perceptual correlate of cortical reorganization following arm amputation. Nature. 1995;375(6531):482–484. doi: 10.1038/375482a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Souza J.M., Cheeseborough J.E., Ko J.H., Cho M.S., Kuiken T.A., Dumanian G.A. Targeted muscle reinnervation: a novel approach to postamputation neuroma pain. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(10):2984–2990. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3528-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim P.S., Ko J.H., O'Shaughnessy K.K., Kuiken T.A., Pohlmeyer E.A., Dumanian G.A. The effects of targeted muscle reinnervation on neuromas in a rabbit rectus abdominis flap model. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(8):1609–1616. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dumanian G.A., Potter B.K., Mioton L.M., et al. Targeted Muscle Reinnervation Treats Neuroma and Phantom Pain in Major Limb Amputees: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Ann Surg. 2019;270(2):238–246. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Brien A.L., Jordan S.W., West J.M., Mioton L.M., Dumanian G.A., Valerio I.L. Targeted muscle reinnervation at the time of upper-extremity amputation for the treatment of pain severity and symptoms. J Hand Surg Am. 2021;46(1):72.e1–72.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2020.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woo S.L., Kung T.A., Brown D.L., Leonard J.A., Kelly B.M., Cederna P.S. Regenerative peripheral nerve interfaces for the treatment of postamputation neuroma pain: a pilot study. Plast Reconst Surg Glob Open. 2016;4(12) doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000001038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kubiak C.A., Kemp S.W.P., Cederna P.S., Kung T.A. Prophylactic regenerative peripheral nerve interfaces to prevent postamputation pain. Plast Reconst Surg. 2019;144(3):421e–430e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000005922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hooper R.C., Cederna P.S., Brown D.L., et al. Regenerative peripheral nerve interfaces for the management of symptomatic hand and digital neuromas. Plast Reconst Surg Glob Open. 2020;8(6) doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000002792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bates T.J., Fergason J.R., Pierrie S.N. Technological advances in prosthesis design and rehabilitation following upper extremity limb loss. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2020;13(4):485–493. doi: 10.1007/s12178-020-09656-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuiken T.A., Marasco P.D., Lock B.A., RN H., Dewald J.P.A. Redirection of cutaneous sensation from the hand to the chest skin of human amputees with targeted reinnervation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(50):20061–20066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706525104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sensinger J.W., Schultz A.E., Kuiken T.A. Examination of force discrimination in human upper limb amputees with rein- nervated limb sensation following peripheral nerve transfer. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2009;17(5):438–444. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2009.2032640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kristeva-Feige R., Rossi S., Pizzella V., et al. A neuromagnetic study of movement-related somatosensory gating in the human brain. Exp Brain Res. 1996;107(3):504–514. doi: 10.1007/BF00230430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rijnbeek E.H., Eleveld N., Olthuis W. Update on peripheral nerve electrodes for closed-loop neuroprosthetics. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:350. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raspopovic S., Capogrosso M., Petrini F.M., et al. Restoring natural sensory feedback in real-time bidirectional hand prostheses. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(222) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Christie B.P., Freeberg M., Memberg W.D., Pinault G.J., Hoyen H.A., Tyler D.J., Triolo R.J. Long-term stability of stimulating spiral nerve cuff electrodes on human peripheral nerves. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2017;14(1):70. doi: 10.1186/s12984-017-0285-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vu P.P., Lu C.W., Vaskov A.K., et al. Restoration of proprioceptive and cutaneous sensation using regenerative peripheral nerve interfaces in humans with upper limb amputations. Plast Reconst Surg. 2022;149(6):1149e–1154e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000009153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Svientek S.R., Ursu D.C., Cederna P.S., Kemp S.W. Fabrication of the composite regenerative peripheral nerve interface (C-RPNI) in the adult rat. J Vis Exp. 2020;156 doi: 10.3791/60841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harrington C.J., Dearden M., Richards J., Carty M., Souza J., Potter B.K. The agonist-antagonist myoneural interface in a transtibial amputation. JBJS Essent Surg Tech. 2023;13(3) doi: 10.2106/JBJS.ST.22.00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carty M.J., Herr H.M. The agonist-antagonist myoneural interface. Hand Clin. 2021;37(3):435–445. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2021.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brånemark P.I. Osseointegration and its experimental background. J Prosthet Dent. 1983;50(3):399–410. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(83)80101-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li Y., Brånemark R. Osseointegrated prostheses for rehabilitation following amputation: The pioneering Swedish model. Unfallchirurg. 2017;120(4):285–292. doi: 10.1007/s00113-017-0331-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Souza J.M., Mioton L., Harrington C., Potter B., Forsberg J. Osseointegration of Extremity Prostheses: A Primer for the Plastic Surgeon. Plast Reconst Surg. 2020;146(6):1394–1403. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000007364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Biddiss E.A., Chau T.T. Upper limb prosthesis use and abandonment: A survey of the last 25 years. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2007;31(3):236–257. doi: 10.1080/03093640600994581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hagberg K., Häggström E., Uden M., Brånemark R. Socket versus bone-anchored trans-femoral prostheses: hip range of motion and sitting comfort. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2005;29(2):153–163. doi: 10.1080/03093640500238014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van de Meent H., Hopman M.T., Frölke J.P. Walking ability and quality of life in subjects with transfemoral amputation: A comparison of osseointegration with socket prostheses. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(11):2174–2178. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Klineberg I. Introduction: From osseointegration to osseoperception. The functional translation. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2005;32(1–2):97–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2005.04135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hebert J.S., Rehani M., Stiegelmar R. Osseointegration for lower-limb amputation: A systematic review of clinical outcomes. JBJS Rev. 2017;5(10):e10. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.17.00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ortiz-Catalan M., Håkansson B., Brånemark R. An osseointegrated human-machine gateway for long-term sensory feedback and motor control of artificial limbs. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(257) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mastinu E., Clemente F., Sassu P., et al. Grip control and motor coordination with im- planted and surface electrodes while grasping with an osseointegrated prosthetic hand. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2019;16(1):49. doi: 10.1186/s12984-019-0511-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Al Muderis M., Khemka A., Lord S.J., Van de Meent H., Frölke J.P. Safety of osseointegrated implants for transfemoral ampu- tees: A two-center prospective cohort study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(11):900–909. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.15.00808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aschoff H.H., Kennon R.E., Keggi J.M., Rubin L.E. Transcutaneous, distal femoral, intramedullary attachment for above-the-knee prostheses: An endo-exo device. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(suppl 2):180–186. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brånemark R., Berlin O., Hagberg K., Bergh P., Gunterberg B., Rydevik B. A novel osseointegrated percutaneous pros- thetic system for the treatment of patients with transfemoral amputation: A prospective study of 51 patients. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B(1):106–113. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.96B1.31905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tillander J., Hagberg K., Berlin Ö., Hagberg L., Brånemark R. Osteomyelitis risk in patients with transfemoral amputations treated with osseointegration prostheses. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475(12):3100–3108. doi: 10.1007/s11999-017-5507-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Küntscher M.V., Erdmann D., Homann H.H., Steinau H.U., Levin S.L., Germann G. The concept of fillet flaps: classification, indications, and analysis of their clinical value. Plast Reconst Surg. 2001;108(4):885–896. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200109150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Frieden R.A. Amputation after tibial fracture: preservation of length by use of a neurovascular island (fillet) flap of the foot. JBJS. 1989;71(7):1109–1110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chiang Y.C., Wei F.C., Wang J.W., Chen W.S. Reconstruction of below-knee stump using the salvaged foot fillet flap. Plast Reconst Surg. 1995;96(3):731–738. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199509000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cavadas P.C. The free forearm fillet flap in traumatic arm amputation. Plast Reconst Surg. 1996;98(6):1119–1120. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199611000-00049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cavadas P.C., Raimondi P. Free fillet flap of the hand for elbow preservation in nonreplantable forearm amputation. J Reconst Microsurg. 2004;20(5):363–366. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-829999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Baccarani A., Follmar K.E., De Santis G., et al. Free vascularized tissue transfer to preserve upper extremity amputation levels. Plast Reconst Surg. 2007;120(4):971–981. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000256479.54755.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Markewych A., Hansdorfer M., Blank A., Kokosis G., Kurlander D. Forequarter amputation: reconstruction with targeted muscle reinnervation to the filet of forearm free flap. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2023;27(3):136–139. doi: 10.1097/BTH.0000000000000424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morris M.T., Dy C.J., Boyer M.I., Brogan D.M. Targeted muscle reinnervation and the volar forearm filet flap for forequarter amputation: description of operative technique. J Hand Surg Glob Online. 2020;2(5):306–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsg.2020.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li J., Huang T.C., Chaudhry A.R., Cantwell S., Moran S.L. Neurotized free VRAM used to create myoelectric signals in a muscle-depleted area for targeted muscle reinnervation for intuitive prosthesis control: A case report. Microsurgery. 2021;41(6):557–561. doi: 10.1002/micr.30722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bueno R.A., Jr., French B., Cooney D., Neumeister M.W. Targeted muscle reinnervation of a muscle-free flap for improved prosthetic control in a shoulder amputee: case report. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36(5):890–893. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gilbert R. Transplant is successful with a cadaver forearm. Med Trib Med News. 1964;5:20–23. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wells M.W., Rampazzo A., Papay F., Gharb B.B. Two decades of hand transplantation: a systematic review of outcomes. Ann Plast Surg. 2022;88(3):335–344. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000003056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kubiak C.A., Etra J.W., Brandacher G., et al. Prosthetic rehabilitation and vascularized composite allotransplantation following upper limb loss. Plast Reconst Surg. 2019;143(6):1688–1701. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000005638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mathes D.W., Schlenker R., Ploplys E., Vedder N. A survey of North American hand surgeons on their current attitudes toward hand transplantation. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(5):808–814. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2009.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bhaskaranand K., Bhat A.K., Acharya K.N. Prosthetic rehabilitation in traumatic upper limb amputees (an Indian perspective) Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2003;123(7):363–366. doi: 10.1007/s00402-003-0546-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Landin L., Bonastre J., Casado-Sanchez C., et al. Outcomes with respect to disabilities of the upper limb after hand allograft transplantation: a systematic review. Transpl Int. 2012;25(4):424–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2012.01433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.McCartney S.L., Patel C., DelRio J.M. Longterm outcomes and management of the heart transplant recipient. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2017;31(2):237–248. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Santos A.H., Jr., Casey M.J., Womer K.L. Analysis of risk factors for kidney retransplant outcomes associated with common induction regimens: a study of over twelve-thousand cases in the United States. J Transplant. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/8132672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nankivell B.J. Kidney Transplantation: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019. Chronic allograft failure; pp. 434–457. [Google Scholar]