Abstract

Eukaryotic ribosomes are enriched with pseudouridine, particularly at the functional centers targeted by antibiotics. Here, we investigated the roles of pseudouridine in aminoglycoside-mediated translation inhibition by comparing the structural and functional properties of the yeast wild-type and the pseudouridine-free ribosomes. We showed that the pseudouridine-free ribosomes have decreased thermostability and high sensitivity to aminoglycosides. When presented with a model internal ribosomal entry site RNA, elongation factor eEF2, GTP (guanosine triphosphate), and sordarin, hygromycin B preferentially binds to the pseudouridine-free ribosomes during initiation by blocking eEF2 binding, stalling ribosomes in a nonrotated conformation. The structures captured hygromycin B bound at the intersubunit bridge B2a enriched with pseudouridine and a deformed codon-anticodon duplex, revealing a functional link between pseudouridine and aminoglycoside inhibition. Our results suggest that pseudouridine enhances both thermostability and conformational fitness of the ribosomes, thereby influencing their susceptibility to aminoglycosides.

Pseudouridine affects ribosome stability and aminoglycoside binding.

INTRODUCTION

It has been well established that the widespread distribution of pseudouridine (Ψ), a C5-glycoside isomer of uridine, in ribosomal RNA (rRNA) contributes to ribosome synthesis, structures, and translation (1–4). Although maintaining identical base pairing interactions as uridine, pseudouridine provides the additional N1 imino proton for binding water molecules (4–9) and for favorable base stacking (10–12). Loss of a subset or all pseudouridine in rRNA has been observed to cause widespread defects ranging from cell growth, ribosome maturation, to translation fidelity (2–5, 13). In humans, mutations in the nucleolar pseudouridine synthase, dyskerin (DKC1), responsible for rRNA pseudouridylation are found in patients who suffer from the X-linked dyskeratosis congenita (X-DC) or its severe variant form, Hoyeraal-Hreidarsson (HH) syndrome (14). Translation of messenger RNAs containing the internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) elements is especially impaired in cells containing the X-DC or HH-associated DKC1 mutants (15–17).

Earlier structural and biophysical studies indicate notable changes in eukaryotic ribosome structures and conformations upon pseudouridine loss, especially at the interfaces of domains and subunits (4, 5, 13). In hypopseudouridylated ribosomes bound with the hibernating factor Stm1, the head and the body move independently whereas in the wild-type ribosome, they move in a correlated fashion (5). When bound with the Taura syndrome virus (TSV) IRES and driven by the elongation factor eEF2 and guanosine triphosphate (GTP), the head of the hypopseudouridylated small ribosomal subunit exhibits swiveling motions exceeding those previously observed in yeast ribosomes (4). Furthermore, different from the wild-type ribosome, at the decoding center of the hypopseudouridylated ribosome, the A-site nucleotides A1755 and A1756 of the small subunit helix 44 (h44) and A2256 of the large subunit helix 69 (H69) at the intersubunit bridge B2a are stabilized in an unusual structure along with the bound eEF2 during IRES translocation (4). Notably, in human ribosomes, loss of only two pseudouridine (18S 609 and 863) led to increased efficiency in tRNA selection observed by single-molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer (smFRET) (13). These results consistently suggest that loss of the otherwise enriched pseudouridine isomers in ribosomes has a notable effect on the well-conserved intersubunit bridge B2a that controls ribosome domain motions.

Recent studies reveal a fascinating link between chemical modifications in rRNA and the susceptibility of ribosomes to aminoglycosides, a potent class of antibiotics used against bacterial infections and some human diseases such as cancers and those associated with premature termination (18). In both bacterial and eukaryotic ribosomes, aminoglycosides exert their activities primarily by binding to the decoding center of the ribosomes involving h44, H69, and the intersubunit bridge B2a where recognition of mRNA codons by tRNA or virus IRES is established (18–20). smFRET experiments show that binding of aminoglycosides can alter the conformational equilibrium of both bacterial and mammalian ribosomes in a chemical substituent-dependent manner (21–23). Notably, the decoding region is enriched with functionally important pseudouridine modifications, which aligns with the observed defects caused by their losses (4, 5, 13, 24). In yeast, removal of pseudouridine at three sites within the decoding region inhibited cell growth and elevated sensitivity to neomycin (25). Reduced pseudouridylation also resulted in an increase in sensitivity of mouse cells to sparsomycin and paromomycin, whereas anisomycin rescued the growth defect (26). In E coli, removing the three conserved pseudouridine within H69 altered its aminoglycoside binding affinities and nucleotide protection pattern (24), although bacteria lacking all seven rRNA pseudouridine showed only minor aminoglycoside sensitivity changes (27). Whereas these results highlight an important interplay between pseudouridylation and aminoglycoside activities in eukaryotic ribosomes, the molecular basis for this relationship remains lacking.

By using the previously established yeast strain (cbf5-D95A) that produces hypopseudouridylated ribosomes (5), we compared the susceptibility of the wild-type and the cbf5-D95A ribosomes to five aminoglycosides that target the decoding center. Cbf5 is the catalytic subunit of the box H/ACA small ribonucleoprotein particles (snoRNPs) responsible for installing more than 40 sites of pseudouridine. The Asp95 to alanine mutation of Cbf5 renders it inactive without affecting snoRNP assembly, therefore producing ribosomes that lack pseudouridylation (5). This strategy allowed us to assemble hypopseudouridylated ribosomes with TSV IRES during eEF2-mediated translocation in the presence of hygromycin B and analyze their cryo–electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structures. It further allowed us to study the thermal stability and the cell-free translation activities of the hypopseudouridylated ribosomes. Our structural and biochemical results provide insights into the binding mechanism of hygromycin B to the eukaryotic ribosomes during IRES initiation and how pseudourine regulates this process.

RESULTS

Loss of pseudouridine increases antibiotic sensitivity

We used spot assays to compare growth sensitivity to aminoglycosides targeting the decoding center between the wild-type and the cbf5-D95A cells. We first estimated the minimal inhibition concentration (MIC50) required to inhibit the growth of wild-type cells for each antibiotic by a combination of liquid and solid culture growth assays (fig. S1A). The concentration around the MIC50 of each aminoglycoside was then applied in spot assays to compare sensitivities between the wild-type and the cbf5-D95A cells (Fig. 1 and fig. S1B). We also performed the spot assays at three different temperatures, 25°, 30°, and 37°C, respectively (Fig. 1 and fig. S1B). Last, we included a nonribosome targeting antibiotics, nystatin in this analysis, to highlight the ribosome-specific effects (Fig. 1 and fig. S1B).

Fig. 1. Hypersensitivity to translation inhibitors of the cbf5-D95A cells.

The growth on agar plates of yeast cells expressing either the wild-type CBF5 (WT) or cbf5-D95A mutant at three indicated temperatures over a period of 96 hours and at different cell densities in the absence (no drug) or presence of translational inhibitors targeting the decoding center or nystatin (HygB, hygromycin B at 15 mg/ml; Apra, apramycin at 0.5 mg/ml; Paro, paromomycin at 0.5 mg/ml; NTC, nourseothricin at 2 μg/ml; nystatin at 20 μg/ml).

Unlike the wild-type cells, the cbf5-D95A cells exhibited heightened sensitivity to the two broad-spectrum antibiotics, hygromycin B and nourseothricin (a natural mixture of streptothricins C, D, E, and F), at all three growth temperatures (Fig. 1A and fig. S1B). The assay results further revealed an elevated sensitivity at 37°C compared to 30° and 25°C for the cbf5-D95A but not for the wild-type cells (Fig. 1A and fig. S1B), suggesting stronger inhibition of the hypopseudouridylated cells at elevated temperatures. Hygromycin B is a monophasic inhibitor of polypeptide synthesis (28) and binds to the decoding center of both bacterial and eukaryotic ribosomes (6, 29–31). By exerting an influence on the intersubunit bridge, hygromysin B efficiently impedes the translocation process of mRNA and tRNA (31–33). Less is known about nourseothricin mechanism of inhibition, but in bacterial ribosomes, it targets multiple sites of the small subunit with a primary binding site at the interface between the head and the body domain (34). It is thus likely that nourseothricin targets similar sites of eukaryotic ribosomes.

The aminoglycosides examined are known to block translation elongation by targeting the universally conserved intersubunit bridge B2a, which interferes with intersubunit rotation dynamics (22) and tRNA translocation (23, 31, 35). The elevated sensitivity of the hypopseudouridylated cells to these inhibitors, therefore, suggests a higher potency of these antibiotics at inhibiting these processes, consistent with the altered translation fidelity and IRES-mediated translocation as a result of pseudouridine loss (4).

Cbf5-D95A cells also display enhanced susceptibility to other bacterial aminoglycosides, paromomycin, and apramycin. However, unlike the pronounced temperature-dependent sensitivity observed for hygromycin B and nourseothricin (Fig. 1), these antibiotics do not exhibit a similar effect, emphasizing the distinct inhibition mechanisms of different aminoglycoside classes and the role of pseudouridine.

Pseudouridine enhances ribosome thermostability

The high sensitivity of the cbf5-D95A ribosomes to aminoglycosides at elevated temperatures suggests a possible change in their thermostability upon pseuodouridine loss. We subsequently performed circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy with both the cbf5-D95A and the wild-type ribosomes. We collected CD scans from 230 to 320 nm of the purified ribosomes as they were denatured by the increasing temperature. We used the ellipticity values at 260 nm as a measure of the RNA tertiary structure and plotted the RNA melting curves to obtain the melting temperature Tm (Fig. 2). The melting curves were also plotted for ellipticity values at 230 nm for comparison as this region is mostly contributed by proteins (fig. S2A).

Fig. 2. Decreased thermostability of the cbf5-D95A ribosomes.

The melting curves extracted from the ellipticity at 260 nm of the CD scans (left) and the first-order derivative of the melting curves (right) for the wild-type and the cbf5-D95A ribosomes in 100 mM KCl, 25 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 2 mM DTT, and 10 mM MgCl2. The calculated the melting temperatures are indicated as means ± SD. Three experimental replicas were performed from which the SEs were computed.

Whereas the wild-type ribosomes began denaturing at 53°C, the cbf5-D95A ribosomes started at a lower temperature, 42°C, leading to their calculated melting temperatures of 66.3° ± 0.1°C and 62.7° ± 0.4°C, respectively (Fig. 2A). Experiments with isolated RNA molecules such as the H69 model showed more drastic difference in Tm between the modified and the unmodified RNA (10), suggesting that the bound proteins and the other molecules of the intact ribosome can partially compensate the difference. The Tm measured from ellipticity at 230 nm showed no noticeable changes between the two ribosomes, suggesting that the stability decrease is largely attributable to RNA. Consistently, reduced magnesium lowered the Tm of both the wild-type and cbf5-D95A ribosomes but to a similar degree (fig. S2B). Furthermore, whereas isolated RNA fragments can be substantially stabilized by antibiotics binding (36), molar excess hygromycin B did not change the melting temperature of the wild-type (65.7° ± 0.1°C) or the cbf5-D95A (62.1° ± 0.2°C) ribosomes (Fig. 2A).

The consistently lower Tm of the cbf5-D95A than that of the wild-type ribosomes under various conditions revealed reduced stability of the ribosomes assembled with the rRNA without pseudouridine. The direct impact of pseudouridylation on ribosome thermostability reflects the previously observed changes in solvent structures and domain motions in ribosomes upon pseudouridine loss (4, 5).

Hygromycin B stabilizes nonrotated decoding structure

In our previous study of the cbf5-D95A ribosomes during IRES-mediated initiation in the absence of hygromycin B (4), we observed the rearranged decoding center, especially in the otherwise heavily pseudouridylated H69. Given that hygromycin B binds to the decoding center, we obtained cryo-EM structures of the ribosomes isolated from the cbf5-D95A cells assembled with TSV IRES, eEF2, GTP, sordarin, and hygromycin B (fig. S3 and table S1).

After extensive three-dimensional (3D) classification, particles are sorted into two major classes, one without eEF2 (initiation) and one with eEF2 (translocation) (figs. S3 and S4 and table S1). It is immediately clear that hygromycin B binds only to the initiation complex (or back translocated upon eEF2 departure) and not to the translocation complex (Fig. 3), suggesting that hygromycin B primarily interferes with the processes prior to eEF2 binding. The presence of eEF2 thus overcomes the effect of hygromycin B inhibition, consistent with the mechanism described biochemically (32). Because the hygromycin B–free structures have been previously characterized (4), we focused on the hygromycin B–bound initiation complexes (Fig. 3A, figs. S3 and S4, and table S1).

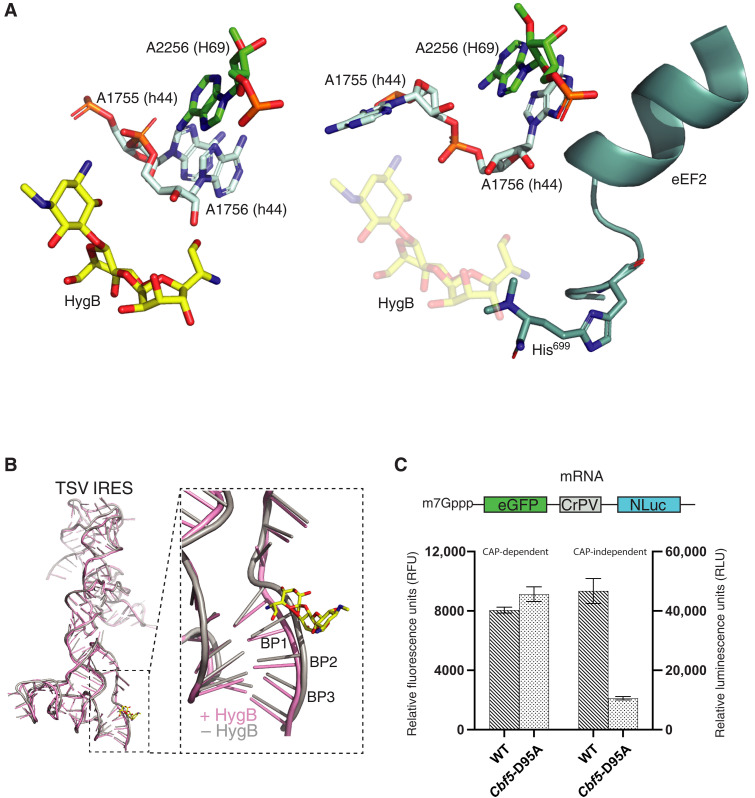

Fig. 3. Structures of hygromycin B bound to the TSV IRES initiation complex.

(A) Cryo-EM structure of cbf5-D95A ribosomes bound with TSV IRES (pink) and hygromycin B (HygB, yellow). The helix 69 of the large subunit (H69) is colored in green, and the helix 44 of the small subunit (h44) is colored blue. Inset shows a close-up view of the bound hygromysin B wedged into a pocket formed by TSV IRES, h44, and H69. (B) Subunit rotation map of the TSV IRES initiation complex of the wild-type ribosome (80SWT•IRES), the hypopseudouridylated ribosome without hygromycin B (80ShypoΨ•IRES), and the hypopseudouridylated ribosome bound with hygromycin B (80ShypoΨ•IRES•HygB). Each filled circle represents a set of head (with respect to body) and body rotation (with respect to the large subunit) angles. The percent of particles contributed to each conformation is indicated in parenthesis. The wild-type ribosome conformations are from the structures indicated by their PDB IDs. The approximate positions of the nonrotated, mid-rotated, and rotated head are marked by arrows. (C) Interactions (top) and density of the bound hygromycin B. The h44 nucleotides are shown in light blue and are marked. The IRES nucleotides are shown in pink. The bound hygromycin B is colored in yellow. Dashed lines indicate close contacts between hygromycin B and the RNA nucleotides.

The hygromycin B–bound initiation complexes largely populate two states, the nonrotated (structure I, 80ShypoΨ•IRES•HB.I, ~58%) and the rotated (structure II, 80ShypoΨ•IRES•HB.II, ~32%) states (Fig. 3B, fig. S3, and table S1). Considering the body rotations, structure I, in its nonrotated state, resembles the classical state of the ribosome bound with mRNA and tRNA. In contrast, structure II is similar to the hybrid state. The dynamic exchange between the two conformations is essential for translocation, where the hybrid state is believed to serve as the substrate for elongation factor binding (37). Both the TSV IRES-bound wild-type (38) and hypopseudouridylated (4) ribosomes also populate the two similar states that are, however, equally populated (Fig. 3B). In contrast, the hygromycin B–bound initiation complex prefers the nonrotated state (Fig. 3B). The preferential population of the nonrotated state depletes the hybrid state, effectively halting eEF2-mediated translocation. This mechanism of inhibition is similar to that established for bacterial ribosomes in which hygromycin B inhibits the spontaneous reverse translocation (31). The decreased RNA stability due to pseudouridine loss likely amplifies the effect, making the ribosome more susceptible to hygromycin B inhibition.

Hygromycin B occupies diphthamide binding site and deforms codon nucleotides

In both initiation complexes, structures I and II, hygromycin B binds at the intersubunit bridge B2a consisting of h44 of 18S and H69 of 25S (Fig. 3C and fig. S4), similar to the binding mode observed in the hygromycin B–bound wild-type human ribosome (6) with one exception. Unlike the human h44-equivalent nucleotide of A1755 (A1824) that stays in helical stack and forms close contacts with hygromycin B (6), A1755 flips out and forms no contact with hygromycin B (Fig. 3C and fig. S4). The bound hygromycin B otherwise forms an extensive network of interactions with other h44 nucleotides 1757 to 1759 and 1640 to 1643 as well as IRES nucleotides 6949 to 6951 mimicking the A codon (Fig. 3C and fig. S4). The direct contact between hygromycin B and the codon-like nucleotides is unique among aminoglycosides. Other aminoglycosides primarily engage only with h44 or other rRNA nucleotides (22). We did not observe any secondary hygromycin B binding site as seen in bacterial ribosomes (30). We also did not observe the base stacking between the yeast-equivalent bacterial A site nucleotides A1492 of h44 and A1913 of H69 when hygromycin B is bound to bacterial ribosomes (31), suggesting a difference between the prokaryotic and the eukaryotic ribosomes.

Superimposition of the translocation and the initiation complex structures showed that the bound eEF2 in the translocation complex would clash with the bound hygromycin B in the initiation complex (Fig. 4A). Specifically, the ring 4 moiety of hygromycin B occupies the same site of the decoding center as the diphthamide residue His699 of eEF2 (Fig. 4A). Diphthamide is critical in stabilizing the codon-anticodon duplex in both CAP- and IRES-dependent translation (39, 40), and its structural environment is sensitive to pseudouridine modification (4). Similarly, the ring I motif of hygromycin B establishes close contacts with the IRES nucleotides mimicking codons (Fig. 3C). The overlap between hygromycin B and diphthamide signifies a similar structural strategy used by both to influence translation although with contrasting consequences.

Fig. 4. Inhibition mechanism of hygromycin B on IRES translocation and the role of pseudouridylation.

(A) Hygromycin B (HygB) competes with eEF2 binding. Comparison of the TSV IRES initiation complex structure (left) and the translocated structure (right, PDB: 8EUB) reveals the clash between the bound hygromycin B (yellow) and the diphthamide 699 of eEF2 (teal). (B) Hygromycin B restructures the messenger RNA. Comparison of the initiation complex in the presence (pink) and the absence (gray) of hygromycin B (yellow) reveals a clash between hygromycin B and the first base pair of the codon (BP1) at the A site. (C) The reporter assay is used to detect changes in the cell-free translation activities caused by the loss of pseudouridine of the cbf5-D95A ribosome. Relative fluorescence levels, indicating CAP-dependent translation, were measured using the enhanced green fluorescent protein signal. Relative luciferase activity, corresponding to CAP-independent translation, was measured using NanoLuc with the Nano-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega). Both fluorescence and luciferase activities were measured after the cell-free in vitro translation reaction. Data are presented as the means ± SD of three independent experiments.

Comparison of the TSV IRES structures in the initiation state with (structure I or structure II) and without (4) hygromycin B reveals a deformed codon-anticodon duplex by the aminoglycoside, regardless of the domain rotational status (Fig. 4B). Hygromycin B binds directly to the IRES nucleotides 6949 to 6952, pushing the codon nucleotides downward to create a binding pocket for itself. Despite minimal disruption to the remaining IRES structure, this localized structural change likely weakens IRES binding and influences ribosome domain conformations. Loss of pseudouridine amplifies these effects, further obstructing IRES binding and translation.

The influence of HgyB on cbf5-D95A ribosome structure is consistent with its vulnerability to the loss of pseudouridylation (4, 5). In both yeast and human cells, IRES-mediated translation depends on the presence of pseudouridylation activity (15, 26). To determine whether the compromised translation activity stems specifically from the cbf5-D95A ribosomes, we conducted cell-free translation assays with purified ribosomes from both wild-type and cbf5-D95A cells (Fig. 4C). In this assay, cbf5-D95A ribosomes exhibited normal activity in CAP-dependent translation but a notable reduction in CAP-independent translation compared to wild-type ribosomes (Fig. 4C). This finding suggests that pseudouridylation is especially critical for IRES-mediated translation, a process that relies more heavily on ribosome dynamics than CAP-dependent translation.

DISCUSSION

Although overwhelming evidence support an essential role of pseudouridine in ribosome structure and function, how this modification affects ribosome thermostability and aminoglycoside activities remains unexplored. We compared the thermostability of the pseudouridine-free and the wild-type Saccharomyces cerevisiae ribosomes using CD, revealing a critical role of pseudouridine in maintaining ribosome thermostability. We performed systematic analysis of cell growth in the presence of both ribosome- and nonribosome-targeting antibiotics that revealed increased sensitivity to aminoglycosides when S. cerevisiae ribosomes lack the pseudouridine modification. We subsequently obtained high-resolution cryo-EM structures of pseudouridine-free S. cerevisiae ribosomes bound with the aminoglycoside hygromycin B during TSV IRES initiation and unveiled hyperstabilization of the ribosome at a state that hinders translocation. Our results consistently show that pseudouridine increases stability and fine-tunes the conformational dynamics of ribosomes.

The severe phenotype and antibiotic sensitivity observed in peudouridine-deficient yeast stand in stark contrast to the relatively mild effects seen in bacteria (27) or archaea (41), where rRNA pseudouridine content is much lower. This highlights the crucial role of high pseudouridine levels in maintaining eukaryotic ribosome structure and function. Consistently, we observed pronounced differences in thermostability between the pseudouridine-deficient and the wild-type yeast ribosomes, a phenomenon less likely to occur in prokaryotic ribosomes. Without pseudouridine, therefore, aminoglycosides may have a greater impact on eukaryotic than prokaryotic ribosomes.

Our finding is particularly relevant to the clinical use of eukaryotic ribosome inhibitors (18). The relationship between pseudouridine and drug sensitivity should be taken into consideration in targeting specific tissue or cell types, given the evidence that rRNA modification is heterogeneous. In addition, either broad-spectrum or site-specific rRNA pseudouridylation may be explored as a coinhibition mechanism with the ribosome drugs.

The thermodynamic and structural roles of pseudouridine have previously been observed in model RNA (10–12). The observed impacts on the intact ribosomes are consistent with and further advance the importance of the pseudouridine modification. Our results highlight the unexpected allosteric effects of pseudouridine on the movement of ribosome domains, providing the structural and thermodynamic basis for the increased sensitivity to antibiotics.

The high sensitivity to the group of aminoglycosides targeting the decoding center coincides with it being both the site of conformational change and highly enriched in pseudouridine. Notably, H69 of the large subunit contains four well-conserved pseudouridines (Ψ2258, Ψ2260, Ψ2264, and Ψ2266) and the extrahelical adenosine A2256 important to decoding. We showed previously that loss of pseudouridine causes changes in H69 nucleotide conformations and hyperstabilizes its interaction with the elongation factor eEF2 during TSV IRES translocation (4), consistent with its impact on antibiotic binding at the same site. However, given the observed changes in thermostability of the entire ribosome and the previously established roles of pseudouridine elsewhere (4), we believe that pseudouridylation throughout the ribosome contributes to ligand binding.

The observation that mutations in ribosome biogenesis factors unrelated to chemical modifications also impacts antibiotic sensitivity (42) suggests that the elevated sensitivity might be partly due to changes in the overall abundance of ribosomes, rather than solely to chemical modifications themselves. Despite so, the structural and biochemical evidence presented highlights the effects of pseudouridylation on the ribosome and translation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning, expression, and purification of yeast eEF2

Cloning and purification of yeast eEF2 was similar as previously described (4). Briefly, eEF2 fused with a C-terminal 6x-His tag was purified from yeast cells transformed with the pRS415-Gal-eEF2-6xHis vector, grown in yeast synthetic uracil dropout media supplemented with raffinose to optical density at 600 nm (OD600) = 0.6~0.8 and induced by the addition of galactose. Nickel affinity was first used followed by MonoQ ion exchange and gel filtration chromatography. The purified eEF2-6xHis was concentrated, flash frozen, and stored in buffer [25 mM Hepes-KOH, 100 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, and 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) (pH 7.5)] in aliquots at −80°C.

Liquid culture assay

To determine MIC50 (minimum inhibitory concentration at which 50% of growth is inhibited) for each aminoglycoside, a single colony of the wild type or the mutant cells was used to start growth in yeast extract, peptone, and dextrose (YPD) containing varying concentrations of the antibiotics for 24 to 48 hours at 25°C. The growth of the microbial cultures was monitored continuously by optical density measurement at 600 nm. The MIC50 was estimated by the lowest concentration of the antibiotics that inhibited the growth by 50% of that in the absence of the antibiotics.

Spot assay

For spot assays, Sc strain BY4741 cells harboring the cbf5-D95A point mutation were grown in YPD in the presence of ampicillin (100 μg/ml) to saturation. After washing three times with cold sterile water, cells were diluted to 1 optical density (OD600nm)/ml, from which four 1-10 serial dilutions were made. The diluted cells were spotted onto agar plates containing appropriate concentrations of antibiotics determined from MIC50 (hygromycin B at 15 μg/ml, apramycin at 0.5 mg/ml, paromomycin at 0.5 mg/ml, and nourseothricin at 2 μg/ml) or from multiple spot assays (nystatin, 10 to 33 μg/ml). The nonribosome targeting antibiotics nystatin was used as a control. The concentration of each antibiotics was determined from the agar plates that were incubated for a total of 96 hours at 25°, 30°, and 37°C, respectively, and were monitored at 36, 72, and 96 hours.

Melting temperature measurement

Melting temperature measurement was conducted by following CD spectrum changes upon thermal denaturation (43) using a Chirascan V100 Circular Dichroism spectrometer with a 1-mm pathlength quartz cuvette. Purified wild-type and cbf5-D95A ribosomes were diluted to 11 optical density (OD260nm)/ml in a CD buffer (100 mM KCl, 25 mM Hepes-KOH, 2 mM DTT, and 10 mM MgCl2) and cooled on ice for 20 min. Denaturation curves were generated by scanning ellipticity from 230 to 300 nm as the temperature increased from 20° to 90°C at a rate of 2°C/min. The ellipticity at 260 nm was extracted for each temperature and plotted as a function of the temperature. The melting temperature was obtained by taking the first derivative of the melting curve (Origin Pro 2022). Three experimental replicas were obtained for each sample, and errors were calculated as SD.

Purification of cbf5-D95A ribosome subunits

Ribosomes from the S. cerevisiae strain BY4741 harboring the cbf5-D95A point mutation were purified similarly as previously described (5, 44, 45). Briefly, ribosomes obtained under the glucose starvation condition were incubated in splitting buffer [20 mM Hepes-KOH, 500 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM puromycin, and 2 mM DTT (pH 7.5)] supplemented with RNase inhibitor for 1 hour at 4°C and loaded on a 10 to 30% sucrose gradient for extracting subunits by centrifugation. The subunits were pooled and buffer exchanged to a grid-making buffer [25 mM Hepes-KOH, 100 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, and 2 mM DTT (pH 7.5)] and flash frozen and for storage at −80°C.

In vitro transcription and purification of TSV IRES

The TSV IRES mRNA 6741 to 6990 was obtained by T7 in vitro transcription from a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) product amplified from the plasmid containing the mRNA clone, and the transcript was purified by using an RNA purification kit (NEB) (4).

Cell-free translation assay

Yeast cells were harvested at an OD600 value of ~0.6 to 0.8. The cell pellet was resuspended and lysed in Buffer A [30 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 100 mM KOAc, 2 mM Mg(OAc)2, 2 mM DTT, 466 mM mannitol, and Roche Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail tablet]. Cells were lysed in liquid N2, and the lysate was exchanged into Buffer B [30 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 100 mM KOAc, 2 mM Mg(OAc)2, 2 mM DTT, 20% glycerol, and Roche Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail tablet] using a PD-10 G25 column. The absorbance at 260 nm (A260) was measured for each 0.5-ml elution fraction, retaining only those with an A260 exceeding 100. Subsequently, ribosomes were pelleted by ultracentrifugation in 4.0-ml polycarbonate thick-wall tubes at 100,000g for 4 hours at 4°C using a 45Ti rotor. The supernatant from wild-type cells was collected as S100. Both wild-type and mutant cell ribosome pellets were resuspended in Buffer C [30 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 100 mM KOAc, 2 mM Mg(OAc)2, and 2 mM DTT], and all ribosome-containing solutions were diluted to the same concentrations measured by A260 (~150). Reporter DNA (Addgene, no. 127332) was transcribed in vitro using the HiScribe T7 Kit with CleanCap (NEB), replacing partial GTP with m7G(5′)ppp(5′)A RNA cap structure analogous to the 5′ capped mRNA. The prepared mRNA was refolded by heating at 65°C for 3 min and then cooling on ice for 30 min. The mRNA was then mixed with S100 and ribosomes at equal RNA concentrations. The reactions were performed in Buffer D [20 mM Hepes (pH 7.6), 120 mM KOAc, 2 mM Mg(OAc)2, 1 mM ATP (adenosine triphosphate), 0.1 mM GTP, 20 mM creatine phosphate (Invitrogen), 0.01 mM each of the 20 amino acids, 2 mM DTT, creatine kinase (0.12 U/μl; Invitrogen), and RNase inhibitor (1 U/μl; NEB)]. The reactions were incubated at 24°C for 2 hours in the PCR tubes. Luciferase activity was subsequently measured using the Nano-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega), and fluorescence activity was measured directly, both using a Synergy HTX plate reader. The data were visualized and processed using the R package ggplot2. P values for significant levels were calculated using a t test in R.

Assembly of inhibition complex of 80S-IRES with hygromycin B

The 40S subunit at 200 nM concentration was incubated with 2 μM refolded TSV IRES RNA for 10 min at 30°C, followed by the addition of 200 nM 60S subunit and another 10 min incubation, to form the 80S-TSV IRES initiation complex. A premixed solution containing 4 μM hygromycin B, 1.7 μM eEF2, 0.3 μM sordarin, and 0.3 μM GTP was added to the 80S-TSV IRES initiation complex followed by additional 10-min incubation at the same temperature. The inhibition reaction mixture was then put on ice before making cryo-EM grids.

Cryo-EM grid preparation, data collection, and analysis

Four microliters of the inhibition reaction mixture was applied onto plasma cleaned holey carbon grids coated with 2-nm-thick amorphous carbon (Quantifoil R 2/2, UT, 300 mesh, copper). Following 30 s of incubation inside the chamber of FEI Vitrobot MK IV (FEI, Hillsboro OR) at 4°C with 100% humidity, grids were blotted for 3 to 4 s and plunged into liquid ethane. Grids were stored in liquid nitrogen prior to data collection.

Cryo-EM data were collected at the National Center for CryoEM Access and Training (NCCAT) on a Titan Krios microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific) operating at 300 kV equipped with energy filter (20 keV) and K3 detector (Gatan Inc.). Micrographs were collected in a movie mode with a total dose of 54 e−/Å2 spreading over 40 frames using Leginon at a nominal magnification of ×81,000 in super-resolution mode, corresponding to a calibrated pixel size of 0.53 Å/pixel. The defocus values were set to range from −0.8 to −2.5 μm. Movie frames were aligned using Motioncor2 (46), and the contrast transfer function (CTF) parameters were estimated using GCTF (47). Particles were picked and 2D classified by cryoSPARC (48) and then exported for further processing in RELION (49). 3D autorefinement was performed to generate the initial consensus map followed by mask-free 3D classification without alignment to further select good particles. High-quality particles were pools and used in alignment-free 3D classifications with a mask covering L1 stalk and TSV IRES RNA. Particles from each class were exported to cryoSPARC for final reconstruction using the nonuniform refinement option.

Model building and refinement

The coordinates were built from the available coordinate of the same ribosome [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID: 7EWC] with appropriate adjustment and placement of hygromycin B in Chimera (50) or COOT (51). No water molecules were added. Manual examination and adjustment of the entire structure were carried out using COOT (51) before rounds of real-space refinement as implemented in PHENIX (52) were carried out until good map correlation coefficients and geometric values were reached (table S1).

RADtool analysis

We used RADtool (Ribosome Analysis Database tool) (53) to compare conformations. For the reported structures, rotation angles were obtained using the RADtool as a plug-in to the VMD program and then were analyzed and compared against the RAD database using the web version of RADtool. The angles were extracted and plotted using Microsoft Excel.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the staff from Biological Science Imaging Resource supported by Florida State University, National Center for CryoEM Access and Training (NCCAT), and the Simons Electron Microscopy Center (SEMC), located at the New York Structural Biology Center.

Funding: This work was supported by NIH grant R35 GM152081 to H.L. and NSF no. 2408763 to H.J. The Titan was funded from NIH grant S10 RR025080. The BioQuantum/K3 was funded from NIH grant U24 GM116788. The Vitrobot Mk IV was funded from NIH grant S10 RR024564. The Solaris Plasma Cleaner was funded from NIH grant S10 RR024564. The DE-64 was funded from NIH grant U24 GM116788. Some of this work was performed at the NCCAT and SEMC, located at the New York Structural Biology Center, supported by the NIH Common Fund Transformative High Resolution Cryo-Electron Microscopy program (U24 GM129539) and by grants from the Simons Foundation (SF349247) and NY State Assembly.

Author contributions: Conceptualization: Y.Z., C.X., and H.L. Funding acquisition: H.J. and H.L. Methodology: Y.Z. and C.X. Investigation: Y.Z., C.X., and X.C. Validation: Y.Z., C.X., X.C., and H.J. Visualization: Y.Z. and C.X. Supervision: H.J. and H.L. Writing—original draft: Y.Z., C.X., and H.L. Writing—review and editing: Y.Z., C.X., X.C., H.J., and H.L.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. The atomic coordinates reported in this work are deposited to the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with accession numbers 9DOV for 80ShypoΨ.IRES.HygB.I and 9DP7 for 80ShypoΨ.IRES.HygB.II. The cryo-EM density map reported here has been deposited to the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) with accession numbers EMD-47093 for 80ShypoΨ.IRES.HygB.I and EMD-47098 for 80ShypoΨ.IRES.HygB.II.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S4

Table S1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Sloan K. E., Warda A. S., Sharma S., Entian K.-D., Lafontaine D. L. J., Bohnsack M. T., Tuning the ribosome: The influence of rRNA modification on eukaryotic ribosome biogenesis and function. RNA Biol. 14, 1138–1152 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.King T. H., Liu B., McCully R. R., Fournier M. J., Ribosome structure and activity are altered in cells lacking snoRNPs that form pseudouridines in the peptidyl transferase center. Mol. Cell 11, 425–435 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang X. H., Liu Q., Fournier M. J., rRNA modifications in an intersubunit bridge of the ribosome strongly affect both ribosome biogenesis and activity. Mol. Cell 28, 965–977 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao Y., Rai J., Li H., Regulation of translation by ribosomal RNA pseudouridylation. Sci. Adv. 9, eadg8190 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao Y., Rai J., Yu H., Li H., CryoEM structures of pseudouridine-free ribosome suggest impacts of chemical modifications on ribosome conformations. Structure 30, 983–992.e5 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Natchiar S. K., Myasnikov A. G., Kratzat H., Hazemann I., Klaholz B. P., Visualization of chemical modifications in the human 80S ribosome structure. Nature 551, 472–477 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polikanov Y. S., Melnikov S. V., Soll D., Steitz T. A., Structural insights into the role of rRNA modifications in protein synthesis and ribosome assembly. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 22, 342–344 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noeske J., Wasserman M. R., Terry D. S., Altman R. B., Blanchard S. C., Cate J. H. D., High-resolution structure of the Escherichia coli ribosome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 22, 336–341 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhatt P. R., Scaiola A., Loughran G., Leibundgut M., Kratzel A., Meurs R., Dreos R., O’Connor K. M., McMillan A., Bode J. W., Thiel V., Gatfield D., Atkins J. F., Ban N., Structural basis of ribosomal frameshifting during translation of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome. Science 372, 1306–1313 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sumita M., Desaulniers J.-P., Chang Y.-C., Chui H. M.-P., Clos L. II, Chow C. S., Effects of nucleotide substitution and modification on the stability and structure of helix 69 from 28S rRNA. RNA 11, 1420–1429 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kierzek E., Malgowska M., Lisowiec J., Turner D. H., Gdaniec Z., Kierzek R., The contribution of pseudouridine to stabilities and structure of RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 3492–3501 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis D. R., Stabilization of RNA stacking by pseudouridine. Nucleic Acids Res. 23, 5020–5026 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McMahon M., Contreras A., Holm M., Uechi T., Forester C. M., Pang X., Jackson C., Calvert M. E., Chen B., Quigley D. A., Luk J. M., Kelley R. K., Gordan J. D., Gill R. M., Blanchard S. C., Ruggero D., A single H/ACA small nucleolar RNA mediates tumor suppression downstream of oncogenic RAS. Elife 8, e48847 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dokal I., Dyskeratosis congenita. Hematology Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2011, 480–486 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoon A., Peng G., Brandenburger Y., Zollo O., Xu W., Rego E., Ruggero D., Impaired control of IRES-mediated translation in X-linked dyskeratosis congenita. Science 312, 902–906 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bellodi C., Krasnykh O., Haynes N., Theodoropoulou M., Peng G., Montanaro L., Ruggero D., Loss of function of the tumor suppressor DKC1 perturbs p27 translation control and contributes to pituitary tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 70, 6026–6035 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bellodi C., Kopmar N., Ruggero D., Deregulation of oncogene-induced senescence and p53 translational control in X-linked dyskeratosis congenita. EMBO J. 29, 1865–1876 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pellegrino S., Terrosu S., Yusupova G., Yusupov M., Inhibition of the eukaryotic 80S ribosome as a potential anticancer therapy: A structural perspective. Cancers (Basel) 13, 4392 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polikanov Y. S., Aleksashin N. A., Beckert B., Wilson D. N., The mechanisms of action of ribosome-targeting peptide antibiotics. Front. Mol. Biosci. 5, 48 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin J., Zhou D., Steitz T. A., Polikanov Y. S., Gagnon M. G., Ribosome-targeting antibiotics: Modes of action, mechanisms of resistance, and implications for drug design. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 87, 451–478 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang L., Pulk A., Wasserman M. R., Feldman M. B., Altman R. B., Cate J. H., Blanchard S. C., Allosteric control of the ribosome by small-molecule antibiotics. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 957–963 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prokhorova I., Altman R. B., Djumagulov M., Shrestha J. P., Urzhumtsev A., Ferguson A., Chang C. T., Yusupov M., Blanchard S. C., Yusupova G., Aminoglycoside interactions and impacts on the eukaryotic ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E10899–E10908 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wasserman M. R., Pulk A., Zhou Z., Altman R. B., Zinder J. C., Green K. D., Garneau-Tsodikova S., Cate J. H., Blanchard S. C., Chemically related 4,5-linked aminoglycoside antibiotics drive subunit rotation in opposite directions. Nat. Commun. 6, 7896 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sakakibara Y., Chow C. S., Pseudouridine modifications influence binding of aminoglycosides to helix 69 of bacterial ribosomes. Org. Biomol. Chem. 15, 8535–8543 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang X. H., Liu Q., Fournier M. J., Loss of rRNA modifications in the decoding center of the ribosome impairs translation and strongly delays pre-rRNA processing. RNA 15, 1716–1728 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jack K., Bellodi C., Landry D. M., Niederer R. O., Meskauskas A., Musalgaonkar S., Kopmar N., Krasnykh O., Dean A. M., Thompson S. R., Ruggero D., Dinman J. D., rRNA pseudouridylation defects affect ribosomal ligand binding and translational fidelity from yeast to human cells. Mol. Cell 44, 660–666 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Connor M., Leppik M., Remme J., Pseudouridine-free Escherichia coli ribosomes. J. Bacteriol. 200, e00540-17 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zierhut G., Piepersberg W., Böck A., Comparative analysis of the effect of aminoglycosides on bacterial protein synthesis in vitro. Eur. J. Biochem. 98, 577–583 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borovinskaya M. A., Pai R. D., Zhang W., Schuwirth B. S., Holton J. M., Hirokawa G., Kaji H., Kaji A., Cate J. H. D., Structural basis for aminoglycoside inhibition of bacterial ribosome recycling. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 727–732 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paternoga H., Crowe-McAuliffe C., Bock L. V., Koller T. O., Morici M., Beckert B., Myasnikov A. G., Grubmuller H., Novacek J., Wilson D. N., Structural conservation of antibiotic interaction with ribosomes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 30, 1380–1392 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borovinskaya M. A., Shoji S., Fredrick K., Cate J. H. D., Structural basis for hygromycin B inhibition of protein biosynthesis. RNA 14, 1590–1599 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eustice D. C., Wilhelm J. M., Mechanisms of action of aminoglycoside antibiotics in eucaryotic protein synthesis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 26, 53–60 (1984). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eustice D. C., Wilhelm J. M., Fidelity of the eukaryotic codon-anticodon interaction: Interference by aminoglycoside antibiotics. Biochemistry 23, 1462–1467 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morgan C. E., Kang Y.-S., Green A. B., Smith K. P., Dowgiallo M. G., Miller B. C., Chiaraviglio L., Truelson K. A., Zulauf K. E., Rodriguez S., Kang A. D., Manetsch R., Yu E. W., Kirby J. E., Streptothricin F is a bactericidal antibiotic effective against highly drug-resistant gram-negative bacteria that interacts with the 30S subunit of the 70S ribosome. PLOS Biol. 21, e3002091 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wohlgemuth I., Garofalo R., Samatova E., Günenç A. N., Lenz C., Urlaub H., Rodnina M. V., Translation error clusters induced by aminoglycoside antibiotics. Nat. Commun. 12, 1830 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang J., Seo H., Chow C. S., Post-transcriptional modifications modulate rRNA structure and ligand interactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 893–901 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blanchard S. C., Kim H. D., Gonzalez R. L. Jr., Puglisi J. D., Chu S., tRNA dynamics on the ribosome during translation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 12893–12898 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koh C. S., Brilot A. F., Grigorieff N., Korostelev A. A., Taura syndrome virus IRES initiates translation by binding its tRNA-mRNA-like structural element in the ribosomal decoding center. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 9139–9144 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Djumagulov M., Demeshkina N., Jenner L., Rozov A., Yusupov M., Yusupova G., Accuracy mechanism of eukaryotic ribosome translocation. Nature 600, 543–546 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murray J., Savva C. G., Shin B. S., Dever T. E., Ramakrishnan V., Fernandez I. S., Structural characterization of ribosome recruitment and translocation by type IV IRES. Elife 5, e13567 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blaby I. K., Majumder M., Chatterjee K., Jana S., Grosjean H., de Crecy-Lagard V., Gupta R., Pseudouridine formation in archaeal RNAs: The case of Haloferax volcanii. RNA 17, 1367–1380 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun J., McFarland M., Boettner D., Panepinto J., Rhodes J. C., Askew D. S., Cgr1p, a novel nucleolar protein encoded by Saccharomyces cerevisiae orf YGL0292w. Curr. Microbiol. 42, 65–69 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Greenfield N. J., Using circular dichroism collected as a function of temperature to determine the thermodynamics of protein unfolding and binding interactions. Nat. Protoc. 1, 2527–2535 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abeyrathne P. D., Koh C. S., Grant T., Grigorieff N., Korostelev A. A., Ensemble cryo-EM uncovers inchworm-like translocation of a viral IRES through the ribosome. Elife 5, e14874 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ben-Shem A., Garreau de Loubresse N., Melnikov S., Jenner L., Yusupova G., Yusupov M., The structure of the eukaryotic ribosome at 3.0 A resolution. Science 334, 1524–1529 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zheng S. Q., Palovcak E., Armache J. P., Verba K. A., Cheng Y., Agard D. A., MotionCor2: Anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods 14, 331–332 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang K., Gctf: Real-time CTF determination and correction. J. Struct. Biol. 193, 1–12 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Punjani A., Rubinstein J. L., Fleet D. J., Brubaker M. A., cryoSPARC: Algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods 14, 290–296 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scheres S. H., RELION: Implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. J. Struct. Biol. 180, 519–530 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pettersen E. F., Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Couch G. S., Greenblatt D. M., Meng E. C., Ferrin T. E., UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W. G., Cowtan K., Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liebschner D., Afonine P. V., Baker M. L., Bunkóczi G., Chen V. B., Croll T. I., Hintze B., Hung L. W., Jain S., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Oeffner R. D., Poon B. K., Prisant M. G., Read R. J., Richardson J. S., Richardson D. C., Sammito M. D., Sobolev O. V., Stockwell D. H., Terwilliger T. C., Urzhumtsev A. G., Videau L. L., Williams C. J., Adams P. D., Macromolecular structure determination using X-rays, neutrons and electrons: Recent developments in Phenix. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol. 75, 861–877 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hassan A., Byju S., Freitas F. C., Roc C., Pender N., Nguyen K., Kimbrough E. M., Mattingly J. M., Gonzalez R. L. Jr., de Oliveira R. J., Dunham C. M., Whitford P. C., Ratchet, swivel, tilt and roll: A complete description of subunit rotation in the ribosome. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, 919–934 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figs. S1 to S4

Table S1