Abstract

Aims

To explore the association of remnant cholesterol (RC) and lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase A2 (Lp‐PLA2) with composite adverse events in a large‐scale prospective study.

Methods

All data were collected from the Asymptomatic Polyvascular Abnormalities Community study between 2010 and 2022. Serum cholesterol levels and Lp‐PLA2 were determined by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay. The participants were categorized into four groups based on their RC and Lp‐PLA2 levels: low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2−, high‐RC/Lp‐PLA2−, low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ and high‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+. The composite endpoint was a combination of first‐ever stroke, myocardial infarction or all‐cause mortality. Cox regression analyses were performed to evaluate associations of RC and Lp‐PLA2 with composite adverse events.

Results

Of the 1864 eligible participants, the average age was 60.6 years, and 74.3% were male. Over a follow‐up of 12 years, we identified 500 composite adverse events, including 210 major adverse cardiovascular events and 342 all‐cause deaths. When compared with the group of low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2−, the hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals in the group of high‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ for stroke, myocardial infarction, major adverse cardiovascular event, all‐cause death and composite endpoints were 1.37 (0.87–2.16), 0.72 (0.28–1.82), 1.29 (0.85–1.95), 1.61 (1.10–2.38) and 1.43 (1.07–1.91), respectively. A significant interaction between RC and Lp‐PLA2 status has been found for all‐cause death and composite endpoint (p for interaction <0.05). In addition, joint association of RC and Lp‐PLA2 with all‐cause death was modified by sex and age of <60 versus ≥60 years (p for interaction: 0.035 and 0.01, respectively).

Conclusions

Elevated RC and Lp‐PLA2 levels were associated with an increased risk of composite adverse events, with these associations significantly influenced by sex and age. Our study highlights the synergistic effect of RC and Lp‐PLA2 on the composite adverse events.

Keywords: lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase A2, prospective study, remnant cholesterol

1. INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) remain the leading cause of death globally, with accelerated atherosclerosis being the primary driver of most cardiovascular events. 1 , 2 Clinical and public health practitioners must prioritize early interventions targeting modifiable risk factors for CVD. In recent years, numerous studies have focused on identifying predictive biomarkers to assess the risk of developing CVD before clinical onset. Inflammatory markers, including interleukin‐6 (IL‐6), D‐dimer, lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase A2 (Lp‐PLA2) and high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein (hs‐CRP), have been linked to atherosclerosis and cardiovascular conditions. 3 , 4 , 5

Vascular inflammation‐mediated endothelial cell injury and dysfunction are early key events in the development of CVDs, laying the foundation for atherosclerosis formation. 6 Lp‐PLA2 is a crucial biomarker of vascular inflammation and a key indicator of susceptibility to atherosclerotic plaque formation. 7 , 8 It is mainly secreted by macrophages, T cells and mast cells and is highly expressed in macrophages, especially at the site of atherosclerotic lesions. 9 It hydrolysates phospholipids in oxidized low‐density lipoprotein (ox‐LDL) and generates proinflammatory mediators such as lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) and oxidized nonesterified fatty acids. 10 In addition, the increased activity of Lp‐PLA2 promotes the degradation of collagen fibres and extracellular matrix within the plaque and reduces the stability of the plaque. 11 Remnant cholesterol (RC) has been widely reported to be highly related to the occurrence of CVD in recent years. 12 , 13 , 14 RC is contained in triglyceride‐rich lipoproteins such as very LDL remnants and intermediate‐density lipoprotein. 15 These RC particles accumulate in the vascular wall, attracting macrophages and stimulating them to secrete additional inflammatory factors, such as tumour necrosis factor‐α, interleukin‐1β (IL‐1β) and interleukin‐6 (IL‐6). This process contributes to vascular endothelial cell dysfunction. 16 In addition, RC can stimulate macrophages within plaques to secrete matrix metalloproteinases, such as matrix metalloproteinase‐9, to further degrade the extracellular matrix. 17 Therefore, we propose that the proinflammatory and destabilizing effects of Lp‐PLA2 and RC may synergistically amplify the risk of cardiovascular events. Notably, early CVD prevention depends on multi‐factor risk assessment and intervention. Synergic effects of Lp‐PLA2 and RC on CVD, however, have not been demonstrated in a large‐scale community population. Meanwhile, studies have pointed to the use of composite endpoints (including all‐cause death) for CVD risk stratification because they better reflect the ‘total vascular burden’ compared with isolated outcomes. 18 Our goal is to assess the joint impacts and risk reclassification capacity of RC and Lp‐PLA2 levels with the onset of composite adverse events using an asymptomatic multi‐vascular abnormality community (asymptomatic polyvascular abnormalities community study [APAC]).

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and population

The participants and data for the APAC were drawn from the Kailuan study, which includes 2047 current and retired Kailuan employees and retirees in Tangshan. 19 A total of 1864 participants were followed from 2010 to 31 December 2022, after excluding those with abnormal Lp‐PLA2 values (n = 9) and missing data on total cholesterol (TC), high‐density lipoproteins (HDL)‐C and LDL cholesterol (LDL‐C) (n = 174). According to Helsinki Declaration guidelines, the study was approved by the Ethics Committees of Kailuan General Hospital and Beijing Tiantan Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all participants in writing.

2.2. Baseline data collection

Researchers collected baseline data from participants by using standardized questionnaires. These included demographic information, history of disease, lifestyles and blood biochemical measurements. Education level was classified into two categories: middle school or below and college or above. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing measured weight in kilograms by the square of measured height in metres. Blood pressure was measured using an automatic digital blood pressure monitor. Diabetes is defined as a fasting blood glucose level ≥7.0 mmol/L, any use of antidiabetic medications, or any self‐reported history of diabetes. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg, any use of antihypertensive medications, or self‐reported history of hypertension. HHcy was defined as blood plasma Hcy >15 μmol/L. The clinical characteristics and biochemical indicators were assessed at Kailuan General Hospital. The detailed protocol and assessment standard were described in a previous study. 18

2.3. Serum RC and Lp‐PLA2 measurements

Serum Lp‐PLA2 mass was measured using an enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). The samples were divided into two groups based on the median value of Lp‐PLA2 expression: high level (Lp‐PLA2+, >141 ng/mL) and low level (Lp‐PLA2−, ≤141 ng/mL). The calculation for RC was done by subtracting HDL‐C and LDL‐C from the TC. According to the manufacturer's instructions, TC and HDL‐C/LDL‐C were measured using the EnzyChrom AF HDL and LDL/very LDL Assay cholesterol quantification kit (BioAssay Systems, Hayward, USA). Similarly, the participants were divided into two groups according to the median value of RC: high level (high‐RC, >0.8 mmol/L) and low level (low‐RC, ≤0.8 mmol/L).

2.4. Outcome assessment

All participants were followed by face‐to‐face interviews at every 2‐year routine medical examination until 31 December 2022 or until death. Follow‐up was conducted by hospital physicians, research physicians and research nurses blinded to the baseline data. Where face‐to‐face meetings were not possible, participants were followed up for 2 years using available clinical records and this follow‐up was extended when additional clinical data was available. For patients who experienced multiple clinical cardiovascular events during follow‐up, the combined endpoint recorded as the first clinical event occurring during follow‐up, including myocardial infarction (MI), stroke or all‐cause death, was predefined as the primary outcome of this study. MI was defined by site physicians in accordance with ACC/AHA guidelines and the World Health Organization Universal Definition of MI. The definition of stroke included ischaemic stroke, intracerebral haemorrhage and subarachnoid haemorrhage. Participants who experienced any type of stroke or MI were classified as having experienced major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs). All‐cause death is defined as any cause of death that is confirmed by a hospital death certificate or a local citizen registry. Clinical outcomes and events were independently monitored and then reviewed by a Data Safety Monitoring Board.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Participants were divided into four groups based on the RC levels and Lp‐PLA2: low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2−, high‐RC/Lp‐PLA2−, low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ and high‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD and compared using ANOVA analysis. Categorical variables are presented as percentages and compared using χ 2 test. Kaplan–Meier estimates were utilized for generating cumulative risk, while the log‐rank test was employed to compare groups. Participants with low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2− were treated as the reference group. Hazard ratios (HR) and corresponding confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using a Cox proportional hazards model with and without adjustment for baseline covariates. Adjustment covariates included age, gender, exercise, smoking, drinking, BMI, hypertension, diabetes, TG, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein, HHcy and waist circumference. Interaction testing was performed by including the interaction term of RC*Lp‐PLA2 to determine the synthetic association of RC and Lp‐PLA2 status with cardiovascular events. In addition, associations of RC and Lp‐PLA2 with outcomes were also tested in participants stratified by the age of <60 versus ≥60 years and gender. Moreover, restricted cubic spline (RCS) analyses were utilized to ascertain the nonlinear correlation of RC and Lp‐PLA2 levels with cardiovascular events. Two‐tailed p‐value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All analyses were conducted with SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Baseline characteristics of eligible participants

A total of 1864 participants were enrolled in the study in Figure S1. Table 1 presented baseline characteristics of four groups of low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2−, high‐RC/Lp‐PLA2−, low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ and high‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+. Mean age was 60.6 years and 74.3% were men. Significant differences were found among the groups in age, education level, smoking status, alcohol consumption, BMI, triglycerides, hs‐CRP, waist circumference, hypertension, diabetes and HHcy (p < 0.05). Also, we observed a tendency for more participants with hypertension and HHcy in higher Lp‐PLA2 groups. In addition, there was a higher prevalence of diabetes among participants with higher RC levels.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants according to RC and Lp‐PLA2 levels.

| Characteristics | Overall (n = 1864) | Low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2− (n = 478) | High‐RC/Lp‐PLA2− (n = 460) | Low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ (n = 436) | High‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ (n = 490) | p‐Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD, year | 60.6 ± 11.6 | 56.8 ± 9.4 | 57.0 ± 9.3 | 62.9 ± 12.5 | 65.7 ± 12.2 | <0.001 |

| Male, No (%) | 1385 (74.3) | 375 (78.5) | 336 (73.0) | 323 (74.1) | 351 (71.6) | 0.089 |

| Exercise frequency, No (%) | ||||||

| Inactive | 681 (36.5) | 170 (35.6) | 170 (37.0) | 171 (39.2) | 170 (34.7) | 0.715 |

| Moderately active | 471 (22.4) | 110 (23.0) | 109 (23.7) | 87 (20.0) | 111 (22.7) | |

| Very active | 766 (41.1) | 198 (41.4) | 181 (39.4) | 178 (40.8) | 209 (42.7) | |

| Education level, No (%) | ||||||

| Middle school or below | 1534 (82.3) | 394 (82.4) | 364 (79.1) | 379 (86.9) | 397 (81.0) | 0.018 |

| College or above | 330 (17.7) | 84 (17.6) | 96 (20.9) | 57 (13.1) | 93 (19.0) | |

| Current drinking, No (%) | 305 (16.4) | 99 (20.7) | 94 (20.4) | 58 (13.3) | 54 (11.0) | <0.001 |

| Current smoking, No (%) | 723 (38.8) | 214 (44.8) | 198 (43.0) | 138 (31.7) | 173 (35.3) | <0.001 |

| BMI, mean ± SD, kg/m2 | 25.0 ± 3.2 | 25.0 ± 3.1 | 25.7 ± 3.1 | 24.4 ± 3.2 | 24.8 ± 3.4 | <0.001 |

| SBP, mean ± SD, mmHg | 136.2 ± 20.3 | 134.4 ± 19.5 | 133.3 ± 18.7 | 139.5 ± 21.6 | 137.9 ± 20.9 | <0.001 |

| DBP, mean ± SD, mmHg | 83.4 ± 11.1 | 84.9 ± 10.9 | 84.2 ± 11.4 | 83.6 ± 11.4 | 80.9 ± 10.8 | <0.001 |

| TG, mean ± SD, mmol/L | 1.7 ± 1.4 | 1.34 ± 0.78 | 2.4 ± 2.0 | 1.3 ± 1.0 | 1.8 ± 1.3 | <0.001 |

| Hs‐CRP, median (IQR), mg/L | 1.2 (0.6–2.6) | 1.0 (0.5–2.2) | 1.3 (0.7–2.6) | 1.0 (0.5–2.5) | 1.5 (0.7–3.4) | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference, mean ± SD, cm | 87.3 ± 9.3 | 87.1 ± 8.9 | 89.0 ± 8.7 | 86.2 ± 10.1 | 86.9 ± 9.2 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, No (%) | 1087 (58.3) | 251 (52.5) | 246 (53.5) | 282 (64.7) | 308 (62.9) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes, No (%) | 316 (17.0) | 63 (13.2) | 85 (18.5) | 66 (15.1) | 102 (20.8) | 0.008 |

| HHcy, No (%) | 953 (51.1) | 213 (44.6) | 214 (46.5) | 226 (51.8) | 300 (61.2) | <0.001 |

| RC, median (IQR), mmol/L | 0.8 (0.4–1.4) | 0.4 (0.3–0.6) | 1.4 (1.1–1.9) | 0.5 (0.3–0.6) | 1.3 (1.0–1.8) | <0.001 |

| Lp‐PLA2, median (IQR), ng/mL | 141.0 (131.4–159.7) | 130.1 (127.5–135.3) | 131.9 (128.0–135.7) | 159.1 (148.0–190.8) | 160.7 (147.1–195.7) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HHcy, hyperhomocysteinaemia; Hs‐CRP, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein; IQR, interquartile range; Lp‐PLA2, Lipoprotein‐Associated Phospholipase A2; RC, remnant cholesterol; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TG, triglyceride.

3.2. Incident events in participants with RC and Lp‐PLA2

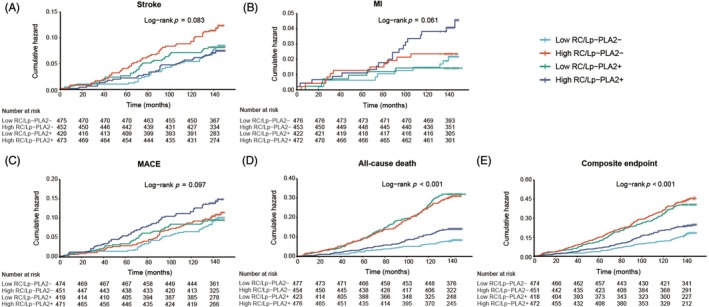

During the 12‐year follow‐up period, 500 composite adverse events were identified, including 168 strokes (9.2%), 51 MIs (2.8%), 210 MACE (11.5%) and 342 all‐cause deaths (18.7%). Participants with High‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ experienced 58 stroke events (12.1%), 13 MI (2.7%), 70 MACE (14.6%), 127 all‐cause deaths (26.6%) and 175 composite endpoints (36.6%) shown in Figure S2. Kaplan–Meier analysis also showed a significant cumulative risk increase of cardiovascular events in the participants of high‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ with low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2− (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Cumulative risk of outcomes during a follow‐up of 12 years in the study population. Kaplan–Meier cumulative risk curves for stroke (A), MI (B), MACE (C), all‐cause death (D) and composite endpoint (E) in participants with RC and Lp‐PLA2 levels. Lp‐PLA2, lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase A2; MACE, Major adverse cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction; RC, remnant cholesterol.

3.3. Associations of RC and Lp‐PLA2 levels with composite adverse events

Table 2 shows the associations of RC and Lp‐PLA2 levels with incident composite adverse events. Participants of high‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ exhibited the highest risk, with an adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) of 1.43 (95% CI: 1.07–1.91; p for interaction = 0.030) for the combined endpoint compared to the reference group of low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2−. When compared with the participants of low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2−, the HR with a 95% CI in the group of high‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ for stroke, MI, MACE and all‐cause death were 1.37 (0.87–2.16), 0.72 (0.28–1.82), 1.29 (0.85–1.95), 1.61 (1.10–2.38) and 1.43 (1.07–1.91), respectively. After adjusting for potential confounders, participants with solely elevated RC, solely elevated Lp‐PLA2 and elevated RC plus Lp‐PLA2 were independently associated with a 73% (adjusted HR [aHR], 1.73; 95% CI 1.13–2.62), 150% (aHR, 2.50; 95% CI 1.71–3.64), and 61% (aHR, 1.61; 95% CI 1.10–2.38) significantly increased risk of all‐cause death, as compared to those with low‐RC and Lp‐PLA2. We also identified statistical interactions between RC and Lp‐PLA2 for all cardiovascular events (p = 0.001 and 0.023 for all‐cause death and composite endpoint, respectively).

TABLE 2.

Association of Lp‐PLA2 and RC level with outcomes in APAC participants.

| Outcome | Events, N (%) | Hazard ratios (95% CI) | p for interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||

| Composite endpoint | 500 (27.3) | |||

| Low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2− | 80 (16.8) | Ref | Ref | 0.030 |

| High‐RC/Lp‐PLA2− | 100 (22.0) | 1.38 (1.02–1.83) | 1.30 (0.96–1.78) | |

| Low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ | 145 (34.2) | 2.33 (1.76–3.07) | 1.67 (1.25–2.23) | |

| High‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ | 175 (36.6) | 2.57 (1.96–3.37) | 1.43 (1.07–1.91) | |

| Stroke | 168 (9.2) | |||

| Low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2− | 39 (8.2) | Ref | Ref | 0.145 |

| High‐RC/Lp‐PLA2− | 34 (7.5) | 0.91 (0.57–1.47) | 0.86 (0.53–1.42) | |

| Low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ | 37 (8.7) | 1.03 (0.65–1.65) | 0.98 (0.61–1.59) | |

| High‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ | 58 (12.1) | 1.50 (0.99–2.29) | 1.37 (0.87–2.16) | |

| Myocardial infarction | 51 (2.8) | |||

| Low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2− | 11 (2.3) | Ref | Ref | 0.698 |

| High‐RC/Lp‐PLA2− | 20 (4.4) | 2.00 (0.93–4.30) | 1.74 (0.78–3.90) | |

| Low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ | 7 (1.7) | 0.68 (0.25–1.87) | 0.53 (0.19–1.51) | |

| High‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ | 13 (2.7) | 1.12 (0.48–2.65) | 0.72 (0.28–1.82) | |

| MACE | 210 (11.5) | |||

| Low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2− | 47 (9.85) | Ref | Ref | 0.284 |

| High‐RC/Lp‐PLA2− | 50 (11.0) | 1.14 (0.75–1.71) | 1.03 (0.67–1.58) | |

| Low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ | 43 (10.1) | 0.99 (0.65–1.54) | 0.91 (0.58–1.42) | |

| High‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ | 70 (14.6) | 1.51 (1.03–2.23) | 1.29 (0.85–1.95) | |

| All‐cause death | 342 (18.7) | |||

| Low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2− | 38 (8.0) | Ref | Ref | <0.001 |

| High‐RC/Lp‐PLA2− | 60 (13.2) | 1.71 (1.14–2.56) | 1.73 (1.13–2.62) | |

| Low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ | 117 (27.6) | 3.87 (2.69–5.59) | 2.50 (1.71–3.64) | |

| High‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ | 127 (26.6) | 3.72 (2.59–5.35) | 1.61 (1.10–2.38) | |

Note: Multivariable analysis adjusted for age, gender, exercise, smoke, drink, BMI, hypertension, diabetes, TG, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein, waist circumference, and hyperhomocysteinaemia.

Abbreviations: APAC, Asymptomatic Polyvascular Abnormalities Community; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; Lp‐PLA2, lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase A2; MACE, Major adverse cardiovascular events; RC, remnant cholesterol; TG, triglyceride.

3.4. Subgroup analyses

Table 3 shows the results of the subgroup analyses according to sex and age. The results indicate that the high‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ group showed a trend toward an increased risk of the composite endpoint compared to the low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2− group, although this association did not achieve statistical significance (p interaction = 0.081 and 0.677, respectively). Notably, joint association of RC and Lp‐PLA2 with all‐cause death was also modified by sex (p interaction = 0.036): HR with a 95% CI in groups of high‐RC/Lp‐PLA2−, low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+, high‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ in male population were 1.67 (1.06–2.62), 2.53 (1.68–3.81), 1.65 (1.09–2.52), respectively. Additionally, as compared with low‐RC and Lp‐PLA2, the HR with a 95% CI for all‐cause death in groups of high‐RC/Lp‐PLA2−, low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+, high‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ among participants with age of <60 years (p interaction = 0.01) were 1.99 (0.88–4.52), 4.05 (1.81–9.06) and 2.57 (1.08–6.14), respectively.

TABLE 3.

Association of RC and Lp‐PLA2 levels with outcomes in APAC participants stratified by gender and age.

| Outcome | Sex | p for interaction | Age (year) | p for interaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | |||||

| Male | Female | <60 | ≥60 | |||

| (n = 1385) | (n = 479) | (n = 1006) | (n = 858) | |||

| Composite endpoint | ||||||

| Low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2− | Ref | Ref | 0.081 | Ref | Ref | 0.677 |

| High‐RC/Lp‐PLA2− | 1.26 (0.90–1.75) | 1.29 (0.55–3.06) | 1.22 (0.78–1.92) | 1.34 (0.87–2.06) | ||

| Low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ | 1.65 (1.21–2.25) | 1.66 (0.74–3.70) | 1.79 (1.11–2.89) | 2.10 (1.45–3.04) | ||

| High‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ | 1.38 (1.00–1.89) | 1.21 (0.54–2.70) | 1.43 (0.86–2.38) | 1.96 (1.36–2.82) | ||

| Stroke | ||||||

| Low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2− | Ref | Ref | 0.841 | Ref | Ref | 0.036 |

| High‐RC/Lp‐PLA2− | 0.82 (0.48–1.40) | 1.36 (0.31–5.90) | 0.81 (0.43–1.52) | 0.98 (0.43–2.27) | ||

| Low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ | 0.96 (0.57–1.61) | 1.03 (0.24–4.42) | 1.33 (0.69–2.54) | 0.96 (0.46–2.00) | ||

| High‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ | 1.20 (0.73–1.99) | 2.54 (0.70–9.25) | 1.00 (0.49–2.02) | 1.82 (0.94–3.53) | ||

| Myocardial infarction | ||||||

| Low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2− | Ref | Ref | 0.803 | Ref | Ref | 0.726 |

| High‐RC/Lp‐PLA2− | 1.86 (0.81–4.29) | 0.36 (0.02–8.45) | 1.91 (0.68–5.39) | 1.41 (0.40–4.98) | ||

| Low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ | 0.49 (0.16–1.50) | 0.23 (0.01–6.35) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.92 (0.25–3.35) | ||

| High‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ | 0.72 (0.27–1.92) | 0.10 (0.00–3.50) | 0.90 (0.22–3.74) | 0.65 (0.18–2.33) | ||

| MACE | ||||||

| Low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2− | Ref | Ref | 0.917 | Ref | Ref | 0.114 |

| High‐RC/Lp‐PLA2− | 1.01 (0.64–1.60) | 1.14 (0.31–4.24) | 0.99 (0.57–1.71) | 1.12 (0.55–2.28) | ||

| Low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ | 0.87 (0.54–1.41) | 0.91 (0.25–3.29) | 1.13 (0.60–2.11) | 0.94 (0.49–1.82) | ||

| High‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ | 1.17 (0.74–1.84) | 1.75 (1.55–5.57) | 1.04 (0.55–2.00) | 1.60 (0.88–2.91) | ||

| All‐cause death | ||||||

| Low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2− | Ref | Ref | 0.036 | Ref | Ref | 0.010 |

| High‐RC/Lp‐PLA2− | 1.67 (1.06–2.62) | 1.35 (0.47–3.90) | 1.99 (0.88–4.52) | 1.47 (0.91–2.38) | ||

| Low‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ | 2.53 (1.68–3.81) | 2.02 (0.78–5.26) | 4.05 (1.81–9.06) | 2.56 (1.68–3.90) | ||

| High‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ | 1.65 (1.09–2.52) | 0.70 (0.25–1.99) | 2.57 (1.08–6.14) | 1.87 (1.23–2.85) | ||

Note: Multivariable analysis adjusted for age, gender, exercise, smoke, drink, BMI, hypertension, diabetes, TG, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein, Waist circumference and hyperhomocysteinaemia.

Abbreviations: APAC, Asymptomatic Polyvascular Abnormalities Community; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratios; Lp‐PLA2, lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase A2; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; RC, remnant cholesterol; TG, triglyceride.

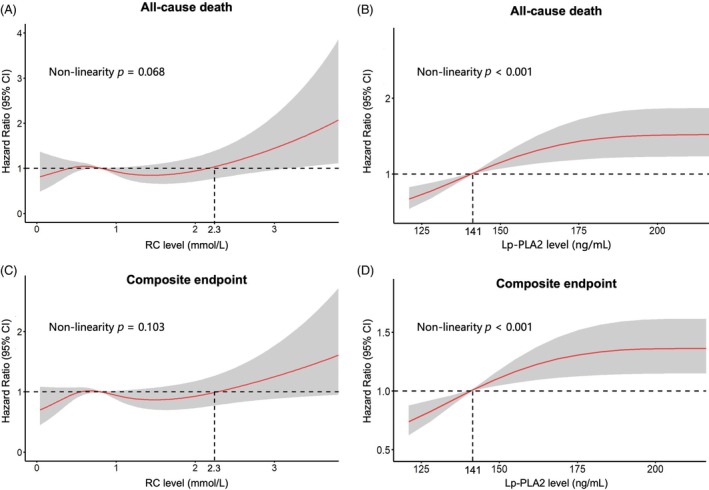

3.5. RCS analysis for threshold effect of RC and Lp‐PLA2 on events

The RCS curve was employed to elucidate the nonlinear association of RC and Lp‐PLA2 with the risk of all‐cause death and composite endpoint (Figure 2). In the multiple confounder correction model, nonlinear association was detected between RC and composite endpoint risk and all‐cause mortality (nolinearity p = 0.068 and 0.103, respectively). However, Lp‐PLA2 demonstrates a linear relationship with CVD risk. Of note, a threshold effect was identified, with a turning point observed at an RC value of 2.3 mmol/L. Below this threshold, the risk of all‐cause death and the composite endpoint remained relatively stable or even decreased, while exceeding this level resulted in a significant increase in risk. In addition, we re‐calculated the association of cardiovascular events with Lp‐PLA2 and RC level using RC of 2.3 mmol/L as the cut‐off point (Table S1).

FIGURE 2.

Restricted cubic spline curves for the association of RC and Lp‐PLA2 with the risk of all‐cause death and composite endpoint. Lp‐PLA2, lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase A2; RC, remnant cholesterol.

4. DISCUSSION

To our best knowledge, this study initially emphasizes the synthetic effect of higher RC and Lp‐PLA2 levels on composite adverse events in the Chinese population. Composite events, including stroke, MI and all‐cause death, occurred in approximately 30.0% of participants with high‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+. A combination of RC and Lp‐PLA2 was associated with stroke, MI, all‐cause death, MACE and composite endpoint. The association of synthetic RC and Lp‐PLA2 with composite endpoint was modified by sex or age.

We found that approximately 30% of high‐RC/Lp‐PLA2+ participants had composite adverse events. Previous studies have shown positive associations between RC or Lp‐PLA2 levels and cardiovascular risk. One study found that approximately 18% of participants experienced CVD events, including MI and CVD death. 20 In the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes cohort, around 16% of individuals with low residual cholesterol had major cardiovascular events over 7.7 years. 21 Another study reported that about 14% of stroke patients with elevated lipoprotein(a) and Lp‐PLA2 had stroke recurrence. 22 Similarly, around 10% of Chinese adults with high‐RC and hs‐CRP experienced a stroke, consistent with our findings. 23

Our study showed that RC and Lp‐PLA2 together increase composite adverse event risk. While the PREDIMED study confirmed the link between RC and major cardiovascular events in high‐risk individuals, 24 and other studies have associated elevated Lp‐PLA2 with coronary artery disease, stroke and death, 4 , 8 , 25 , 26 our study observed that increased Lp‐PLA2 levels were negatively correlated with MI, although the differences were not statistically significant. Lp‐PLA2 has been reported to have both pro‐ and anti‐inflammatory effects, depending on whether it binds to HDL (anti‐inflammatory) or LDL (proinflammatory). 27 Some studies suggest that Lp‐PLA2 may play a protective role by degrading platelet‐activating factor and removing oxidized phospholipids, potentially reducing MI risk under certain conditions. 28 This dual role may explain the inverse association observed in our study. Similarly, we did not find a significant association between RC/Lp‐PLA2 levels and MACE in this cohort. The small sample size of events for MI and MACE in our cohort may have limited the statistical power to detect significant associations. Therefore, this finding cannot be generalized to a broader population at this time, and larger cohort studies with higher event rates are needed to clarify these relationships. It is worth mentioning that in our study, it was decided to use a composite endpoint reflecting the overall burden of atherosclerotic lesions and to include all‐cause mortality in the composite endpoint. Although, all‐cause mortality includes noncardiovascular (e.g. cancer‐related) deaths, there are still many underlying common risk factors with cardiovascular. 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 In addition, higher RC levels (>2.3 mmol/L) appear to contribute more to cardiovascular risk. These results highlight the importance of RC in lipid management, warranting further validation in larger populations. It is important to note that significant statistical interactions were found between RC and Lp‐PLA2 levels in relation to all‐cause death, as Lp‐PLA2 plays a key role in vascular inflammation by regulating lipid metabolism and promoting monocyte migration to the arterial intima, leading to atherosclerotic cardiovascular events. 29 , 34

We further investigated the association of Lp‐PLA2 combined RC levels with composite adverse event risk across gender and age. Our analysis revealed that this higher association of elevated serum RC and Lp‐PLA2 levels with increased risk of events has been observed in participants with age of <60 and in male. In a previous study on the age‐dependent association of RC with CVD, a significant interaction between age and RC on CVD risk was found, which was consistent with our research. 35 Another report in young adults (≤40 years) noted strong RC in patients with early‐onset MI. 36 This will guide us in the future by quantifying the important role of RC and inflammation markers in the development of CVD in young male population. Therefore, combining Lp‐PLA2 and RC levels might be used for prediction of future cardiovascular events in clinical practice or CVD secondary prevention, especially in young male individuals. However, in our study cohort, approximately 70% of the participants were male, which may have important implications for the interpretation and generalizability of our findings. CVD risk profiles differ significantly between males and females due to biological, hormonal and lifestyle factors. The predominance of male participants in our cohort may therefore limit the applicability of our findings to female populations, particularly given that postmenopausal women experience significant shifts in lipid profiles and cardiovascular risk. Future studies with a more balanced sex distribution are warranted to explore potential sex‐specific effects and enhance the generalizability of our results.

Several limitations should be acknowledged in this study. First, we did not directly measure RC levels; instead, we used indirect calculations, which may overestimate its value. However, this method is simple, cost‐effective and widely used, and it provides valuable data for clinical management. Second, most participants were from a single community, limiting the generalizability of our results to broader populations. Third, RC and Lp‐PLA2 levels were measured only at baseline, potentially overlooking changes over time. Lastly, although we adjusted for potential covariates, we cannot fully rule out residual or unmeasured confounding due to the observational nature of the study. We explicitly acknowledge that our cohort was derived from a single community in China, and variations in genetic, socioeconomic, dietary and healthcare systems across APAC nations may influence the applicability of our findings. However, several cardiovascular risk factors are prevalent in many countries in the Asia‐Pacific region, including a high prevalence of metabolic risk factors (e.g. diabetes mellitus, hypertension and dyslipidaemia) and lifestyle shifts (e.g. urbanization, sedentary lifestyle and westernized diet). 37 Elevated RC and Lp‐PLA2 levels have been linked to CVD risk in diverse APAC populations, including Japanese and Korean cohorts. 38 , 39 Therefore, large‐scale regional collaborations are warranted to establish population‐specific risk thresholds and refine CVD prevention strategies.

In conclusion, in a prospective cohort study of Chinese adults, we found that RC and Lp‐PLA2 levels were associated with the occurrence of cardiovascular events. Our findings suggest that the combined assessment of RC and Lp‐PLA2 may be an important indicator for vascular risk management and a potential therapeutic target for CVD.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

X.Z. and B.C. conceived and designed the study and analyses. Y.L. and L.Z. analysed data. Y.X. and T.Z. write the manuscript. Y.Z., RX., WW., K.Z., W.C., W.X., Y.L. and L.Z. performed material preparation and data collection. All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (grant number 2021YFC2500500); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers U22A20364 and 92049302); National Science and Technology Major Project for the Prevention and Treatment of Cancer, Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Diseases, Respiratory Diseases and Metabolic Diseases (grant number 2024ZD0524202).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no competing financial/non‐financial interests.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://www.webofscience.com/api/gateway/wos/peer‐review/10.1111/dom.16286.

Supporting information

Data S1. Supporting information.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None.

Liu Y, Zhang L, Xu Y, et al. Joint association of remnant cholesterol and lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase A2 with composite adverse events: A 12‐year follow‐up study from Asymptomatic Polyvascular Abnormalities Community study . Diabetes Obes Metab. 2025;27(5):2790‐2799. doi: 10.1111/dom.16286

Yuhe Liu and Liang Zhang contributed equally to this study.

Contributor Information

Xingdong Zheng, Email: sfph_edu2@163.com.

Baofu Chen, Email: chenbf1221@163.com.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sasso FC, Lascar N, Ascione A, et al. Moderate‐intensity statin therapy seems ineffective in primary cardiovascular prevention in patients with type 2 diabetes complicated by nephropathy. A multicenter prospective 8 years follow up study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15(1):147. doi: 10.1186/s12933-016-0463-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990‐2019: update from the GBD 2019 study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(25):2982‐3021. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nambi V, Hoogeveen RC, Chambless L, et al. Lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase A2 and high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein improve the stratification of ischemic stroke risk in the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. Stroke. 2009;40(2):376‐381. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.513259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Oei H‐HS, van der Meer IM, Hofman A, et al. Lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase A2 activity is associated with risk of coronary heart disease and ischemic stroke: the Rotterdam study. Circulation. 2005;111(5):570‐575. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000154553.12214.CD [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ammirati E, Moroni F, Norata GD, Magnoni M, Camici PG. Markers of inflammation associated with plaque progression and instability in patients with carotid atherosclerosis. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:1‐15. doi: 10.1155/2015/718329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marchio P, Guerra‐Ojeda S, Vila JM, Aldasoro M, Victor VM, Mauricio MD. Targeting early atherosclerosis: a focus on oxidative stress and inflammation. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:8563845. doi: 10.1155/2019/8563845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ma S, Ding L, Cai M, Chen L, Yan B, Yang J. Association Lp‐PLA2 gene polymorphisms with coronary heart disease. Dis Markers. 2022;2022:9775699. doi: 10.1155/2022/9775699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lp‐PLA(2) Studies Collaboration , Thompson A, Gao P, et al. Lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase a(2) and risk of coronary disease, stroke, and mortality: collaborative analysis of 32 prospective studies. Lancet. 2010;375(9725):1536‐1544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60319-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hatoum IJ, Nelson JJ, Cook NR, Hu FB, Rimm EB. Dietary, lifestyle, and clinical predictors of lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase A2 activity in individuals without coronary artery disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(3):786‐793. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lu J, Niu D, Zheng D, Zhang Q, Li W. Predictive value of combining the level of lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase A2 and antithrombin III for acute coronary syndrome risk. Biomed Rep. 2018;9(6):517‐522. doi: 10.3892/br.2018.1162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sun C, Xi N, Sun Z, et al. The relationship between intracarotid plaque neovascularization and Lp (a) and Lp‐PLA2 in elderly patients with carotid plaque stenosis. Dis Markers. 2022;2022:6154675. doi: 10.1155/2022/6154675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tada H, Kaneko H, Suzuki Y, et al. Association between remnant cholesterol and incident atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation. J Clin Lipidol. 2024;18(1):3‐10. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2023.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu C, Dai M, Tian K, et al. Association of remnant cholesterol with CVD incidence: a general population cohort study in Southwest China. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023;10:1286286. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1286286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jin J, Hu X, Francois M, et al. Association between remnant cholesterol, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease: post hoc analysis of a prospective national cohort study. Eur J Med Res. 2023;28(1):420. doi: 10.1186/s40001-023-01369-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lecamwasam A, Mansell T, Ekinci EI, Saffery R, Dwyer KM. Blood plasma metabolites in diabetes‐associated chronic kidney disease: a focus on lipid profiles and cardiovascular risk. Front Nutr. 2022;9:821209. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.821209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang K, Wang R, Yang J, et al. Remnant cholesterol and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: metabolism, mechanism, evidence, and treatment. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:913869. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.913869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sanda GM, Deleanu M, Toma L, Stancu CS, Simionescu M, Sima AV. Oxidized LDL‐exposed human macrophages display increased MMP‐9 expression and secretion mediated by endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Cell Biochem. 2017;118(4):661‐669. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Visseren FLJ, Mach F, Smulders YM, et al. 2021 ESC guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2022;29(1):5‐115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhou Y, Li Y, Xu L, et al. Asymptomatic polyvascular abnormalities in community (APAC) study in China: objectives, design and baseline characteristics. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e84685. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang C, Fang X, Hua Y, et al. Lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase A2 and risk of carotid atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events in community‐based older adults in China. Angiology. 2018;69(1):49‐58. doi: 10.1177/0003319717704554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fu L, Tai S, Sun J, et al. Remnant cholesterol and its visit‐to‐visit variability predict cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes: findings from the ACCORD cohort. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(9):2136‐2143. doi: 10.2337/dc21-2511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xue J, Xiang Y, Jiang X, et al. The joint association of lipoprotein(a) and lipoprotein‐associated phopholipase A2 with the risk of stroke recurrence. J Clin Lipidol. 2024;18(5):e729‐e737. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2024.04.133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Xiong C‐C, Gao F, Zhang J‐H, et al. Investigating the impact of remnant cholesterol on new‐onset stroke across diverse inflammation levels: insights from the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). Int J Cardiol. 2024;405:131946. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2024.131946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Castañer O, Pintó X, Subirana I, et al. Remnant cholesterol, not LDL cholesterol, is associated with incident cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(23):2712‐2724. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sudhir K. Clinical review: lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase A2, a novel inflammatory biomarker and independent risk predictor for cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(5):3100‐3105. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ballantyne CM, Hoogeveen RC, Bang H, et al. Lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase A2, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein, and risk for incident coronary heart disease in middle‐aged men and women in the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. Circulation. 2004;109(7):837‐842. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000116763.91992.F1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cheng Z, Weng H, Zhang J, Yi Q. The relationship between lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase‐A2 and coronary artery aneurysm in children with Kawasaki disease. Front Pediatr. 2022;10:854079. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.854079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zalewski A, Macphee C. Role of lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase A2 in atherosclerosis: biology, epidemiology, and possible therapeutic target. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25(5):923‐931. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000160551.21962.a7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Libby P, Ridker PM, Maseri A. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002;105(9):1135‐1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Libby P, Ridker PM, Hansson GK, et al. Inflammation in atherosclerosis: from pathophysiology to practice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(23):2129‐2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420(6917):860‐867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Giovannucci E, Harlan DM, Archer MC, et al. Diabetes and cancer: a consensus report. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(7):1674‐1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lauby‐Secretan B, Scoccianti C, Loomis D, et al. Body fatness and cancer‐‐viewpoint of the IARC working group. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(8):794‐798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Münzel T, Gori T. Lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase a(2), a marker of vascular inflammation and systemic vulnerability. Eur Heart J. 2009;30(23):2829‐2831. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang A, Tian X, Zuo Y, et al. Age dependent association between remnant cholesterol and cardiovascular disease. Atheroscler Plus. 2021;45:18‐24. doi: 10.1016/j.athplu.2021.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Goliasch G, Wiesbauer F, Blessberger H, et al. Premature myocardial infarction is strongly associated with increased levels of remnant cholesterol. J Clin Lipidol. 2015;9(6):801‐806. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2015.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li J‐J, Yeo KK, Tan K, et al. Tackling cardiometabolic risk in the Asia Pacific region. Am J Prev Cardiol. 2020;4:100096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Huh JH, Han K‐D, Cho YK, et al. Remnant cholesterol and the risk of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes: a nationwide longitudinal cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21(1):228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ueshima H, Kadowaki T, Hisamatsu T, et al. Lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase A2 is related to risk of subclinical atherosclerosis but is not supported by Mendelian randomization analysis in a general Japanese population. Atherosclerosis. 2016;246:141‐147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Supporting information.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.