Abstract

Fabry disease (FD) is a lysosomal storage disorder in which α-galactosidase (GLA) deficiency leads to a build-up of globo-triaosylceramide (Gb3) in various cell types. Gb3 accumulation leads to the abnormalities of microvascular function associated with FD. Previously, we discovered significant abnormalities in vascular endothelial cells (VECs) derived from FD-induced pluripotent stem cells. We then used a cell-based system to screen a group of clinical compounds for candidates capable of rescuing those abnormalities. Lomerizine was one of the most promising candidates because it alleviated a variety of FD-associated phenotypes both in vitro and in vivo. Lomerizine reduced mitochondria Ca2+ levels, ROS generation, and the maximal respiration of FD-VECs in vitro. This led to a suppression of the endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT) and rescued FD-VEC function. Furthermore, FD-model mice (Gla−/−/TSP1Tg) treated orally with lomerizine for 6 months showed clear improvement of several FD phenotypes, including left ventricular hypertrophy, renal fibrosis, anhidrosis, and heat intolerance. Thus, our results suggest lomerizine as a novel candidate for FD therapy.

Keywords: Fabry disease, iPSCs, Vascular endothelial cells, Drug screening, Lomerizine

Subject terms: Drug screening, Induced pluripotent stem cells

Introduction

Fabry disease (FD) is the second most common lysosomal storage disorder and is caused by a deficiency of α-galactosidase A (GLA)1. GLA deficiency causes various cell types, especially endothelial cells, to accumulate globo-triaosylceramide (Gb3)2. Although FD patients often present at an early age with vascular lesions such as angiokeratomas3, as the disease progresses, it often results in life-threatening vasculopathies, such as left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), renal failure, and age-related brain strokes4,5. Each of these FD-associated complications have been linked to microvascular dysfunction6. FD patients are generally treated with enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) using recombinant human α-galactosidase (agalsidase-β) or pharmacological chaperone therapy7,8. ERT has been shown to improve certain symptoms of FD, such as pain and quality of life metrics. However, studies suggest that its long-term use may not fully halt disease progression or prevent complications like renal failure in some patients9–11. The therapeutic effectiveness of ERT is also limited by the short half-life of the enzyme in the body and its progressive increase in immunogenicity in FD patients undergoing long-term treatment12. Chaperone therapy is also limited in that it only works for FD patients with specific GLA mutational variants13,14. Clearly, FD patients who continue to suffer vascular manifestations need novel therapeutic strategies. Therefore, specialized cells differentiated from patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) can be useful for drug screening15. Recently, using a cellular model for FD, we found that vascular endothelial cells (VECs) differentiated from FD-iPSCs exhibit overexpression of Thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) and hyperactivation of p-SMAD2 (phosphorylated SMAD Family Member 2) signaling, leading to FD-VEC dysfunction16. Another study using the same FD cellular model identified several chemical compounds already approved for use in the clinic that potently rescued these FD-VEC defects17. Here, we report the results of in vitro and in vivo experiments testing the therapeutic effects of lomerizine on FD.

Lomerizine is a calcium antagonist that specifically blocks both V- and L-type voltage-dependent calcium channels18,19. Lomerizine is used clinically in the treatment of neurological pain syndromes, such as migraines18. Calcium signaling contributes to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) via respiratory chain activity20. Gb3 accumulation in FD-VECs reportedly induces ROS generation21. This is particularly important because ROS can induce the endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT)22 that can eventually lead to organ fibrosis23. Fibrosis is a hallmark of FD associated with tissue ischemia in the microvasculature24. Although ERT can partially clear Gb3 accumulation, it does not do much for FD patients with progressive tissue fibrosis11. Although we expect pharmacological inhibition of EndMT to improve the effectiveness of ERT in FD patients, the effectiveness of lomerizine has not yet been tested in FD patients.

Here, our findings suggest that lomerizine has potential as a therapeutic candidate for FD. We show that treatment of FD-VECs with lomerizine reduced their levels of the anti-angiogenic factors p-SMAD2 and TSP1 and increased their expression of the angiogenic factors KDR (Kinase Insert Domain Receptor), and eNOS (endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase). We found lomerizine treatment reduced mitochondrial Ca2+, ROS production, and maximal respiration in FD-VECs, leading to reduced expression of EndMT markers. Moreover, we found oral administration of lomerizine to FD-mice (Gla−/−/TSP1Tg) alleviated several of their FD-like phenotypes, including LVH, renal fibrosis, anhidrosis, and heat intolerance. Thus, our results indicate lomerizine is a highly promising candidate for FD therapy.

Results

Lomerizine improves the defective angiogenesis of FD-VECs

We previously reported that FD-VECs exhibit endothelial dysfunction in vitro16. Since then, we have developed a phenotypic screening platform for drug repurposing to identify chemical compounds that improve the angiogenic functionality of FD-VECs17. Using this cell-based platform to screen a library of FDA-approved clinical compounds, we identified several compounds that rescued the impaired angiogenesis of FD-VECs. In that study, our results suggested fasudil as a new candidate for FD therapy17. In this study, we wanted to explore the effectiveness of lomerizine—another potent candidate compound—both in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 1a). We selected lomerizine because it showed repeated effectiveness in promoting tube-like structure formation in FD-VECs. Using total tube length as an outcome for our in vitro assays on the effectiveness of lomerizine, we observed dose-dependent responses, measured the EC50, and determined that 1 μM is the optimal concentration for maximal effectiveness (Supplementary Fig. S1a). Lomerizine treatment significantly increased total tube length of FD-VECs in our tube formation assay (Fig. 1b). In addition, we found lomerizine treatment enhanced the capacity of FD-VECs with distinct GLA mutations to form tubules (Supplementary Fig. S1b). Furthermore, lomerizine treatment reduced FD-VEC levels of p-SMAD2 and TSP1 and increased their expression of KDR and eNOS (Fig. 1c). When we performed an immunostaining analysis, we confirmed reduced TSP1 expression and increased KDR expression in lomerizine-treated FD-VECs (Fig. 1d). Thus, lomerizine seems to be a potent enhancer of FD-VEC angiogenesis in vitro.

Fig. 1.

Lomerizine improves the impaired angiogenesis of FD-VECs. (a) Schematic for the drug screening procedure using FD-VECs. FD-VECs were differentiated from FD-iPSCs for phenotypic drug screening. FDA-approved clinical compounds were tested for their ability to improve the endothelial functionality of FD-VECs. First, compounds inducing cytotoxicity or aberrant morphologies were excluded. Then, the remaining compounds were screened for their ability to affect the competence of FD-VECs to form a tube-like structure. Finally, the therapeutic effects of the most effective compound were tested in FD-mice. Immunohistology was performed on kidney cortex (rectangular box). (b) Tube-like structure formation in WT-VECs, untreated FD-VECs (FD), lomerizine-treated FD-VECs, and gene-corrected FD-VECs (FD(c)). Lomerizine-treated FD-VECs produced structures with significantly longer total tube length than the non-treated group. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 4); p < 0.05 via a Student’s t-test; Scale bars: 200 µm; WT, wild type; FD, Fabry disease; L, lomerizine. (c) Western blots for the cells described in (A). Treating FD-VECs with lomerizine reduced p-SMAD2 and TSP1 and increased KDR and eNOS. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 5); *p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.001 via a Student’s t-test. Full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. 7. (d) Immunostaining of TSP1 and KDR in the cells described in (A). Lomerizine reduced TSP1 and increased KDR in FD-VECs. Scale bars: 50 µm.

Lomerizine improves the mitochondrial dysfunction of FD-VECs

We next asked how lomerizine improves the angiogenic capacity of FD-VECs, with a focus on mitochondrial dysfunction, including alterations in mitochondrial calcium (mito-Ca2⁺) levels and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. Gb3 accumulation reportedly enhances neuronal voltage-gated calcium currents25. Calcium signaling plays an important role in the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in mitochondria via activity of the respiratory chain. Any imbalance between ROS production and the antioxidant defense systems leads to endothelial dysfunction20. Hence, we examined the effects of lomerizine on FD-VEC mitochondrial calcium levels and ROS production. When we compared mitochondrial calcium uptake (MCU) in WT-VECs and FD-VECs treated with either lomerizine or Ru360 (an MCU blocker), we found via FACS analysis that FD-VECs showed higher mitochondria Ca2+ (mito-Ca2+) levels than WT-VECs (Fig. 2a). WT- and FD-VECs showed no difference, however, in total Ca2+ levels (Supplementary Fig. S2a). Intriguingly, we found the MCU inhibition induced by both lomerizine and Ru360 treatment significantly reduced mito-Ca2⁺ levels in FD-VECs (Fig. 2a), suggesting that lomerizine directly targets mitochondrial calcium dysregulation, a known contributor to endothelial dysfunction in FD. Thus, it is likely that lomerizine influences mito-Ca2+ levels in FD-VECs. To determine whether these increased mito-Ca2+ levels in FD-VECs were also associated with aberrant expression of angiogenic factors, we treated WT- and FD-VECs for 24 h with the MCU activator kaempferol (5 μM). Kaempferol treatment enhanced TSP1 expression and reduced KDR expression in WT-VECs but produced even more significant changes in their expression profiles in FD-VECs (Supplementary Fig. S2b). This implies that mito-Ca2+ concentration is a key switch for the aberrant expression of angiogenic factors in FD-VECs.

Fig. 2.

Lomerizine improves the mitochondrial dysfunction of FD-VECs. (a) Proportion of Rhod-2-positive WT, FD, lomerizine-treated FD-VECs (FD + L), and Ru360-treated FD-VECs (FD + Ru360). Lomerizine reduced mitochondria Ca2+ levels in FD-VECs. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 3); *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 via a Student’s t-test. (b) Representative images and analysis of fluorescence intensity induced by ROS in WT-VECs, untreated FD-VECs (FD), lomerizine-treated FD-VECs, and gene-corrected FD-VECs (FD(c)). Lomerizine reduced ROS generation in FD-VECs. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 4); *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 via a Student’s t-test. (c) Transcript levels of the ROS-related genes GSTM1, NCF2, and PPARGC1A in the cells described in (a). Lomerizine reduced the expression of ROS-related genes in FD-VECs. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 3); *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 via a Student’s t-test.

Next, we measured ROS levels in FD-VECs. Although FD-VECs showed higher ROS production than WT-VECs and FD(c)-VECs, FD-VECs treated with lomerizine showed reduced ROS levels (Fig. 2b). FD-VECs treated with lomerizine also showed reduced transcriptional expression of the ROS-associated genes GSTM1, NCF2, and PPARGC1A (Fig. 2c). In addition, FD-VECs exhibited higher basal respiration (I), ATP production (II), maximal respiration (III), and spare capacity (IV) in the oxygen consumption process than WT- or FD(c)-VECs (Supplementary Fig. S2c). Lomerizine slightly reduced their maximal oxygen consumption in FD-VECs. Collectively, these results indicate lomerizine effectively rescues the increased mito-Ca2+ concentration and ROS production of FD-VECs.

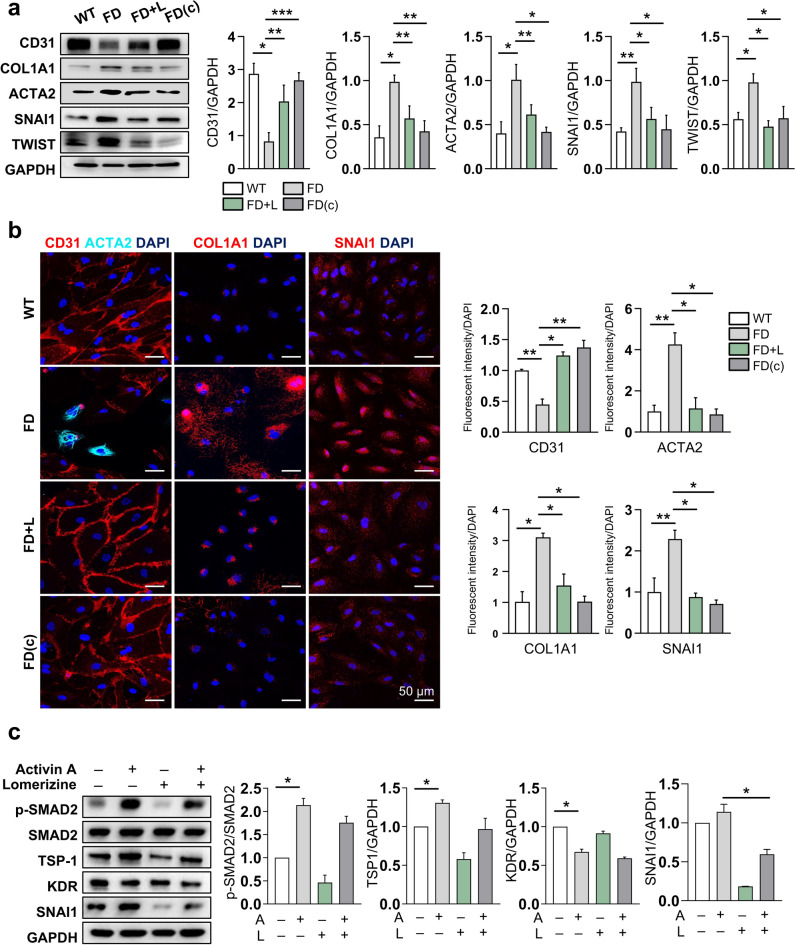

Lomerizine improves FD-VEC function by downregulating EndMT

We then asked how lomerizine rescues the endothelial dysfunction of FD-VECs via ROS clearance. ROS reportedly induce the endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT)22. Given the ability of lomerizine to reduce ROS generation from FD-VECs, we asked whether lomerizine also affects EndMT in FD-VECs. First, we found reduced KDR-positive and CD31-positive FD-VECs on days 12 and 15 of culture after MACS sorting, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S3a). Using western blot analysis, we confirmed a significant reduction in CD31 and increased expression of EndMT markers (i.e., COL1A1, ACTA2, SNAI1, and TWIST) in FD-VECs on culture day 15 (Fig. 3a). We also detected expression of the EndMT marker ACTA2 in FD-VECs on culture day 15 (Supplementary Fig. S3b). Thus, FD-VECs lose their endothelial properties via the EndMT process during long-term in vitro culture. Intriguingly, lomerizine treatment reduced the expression of those EndMT-associated genes in FD-VECs far more than the expression of the same genes in WT-VECs or FD(c)-VECs (Fig. 3a). Consistent with our western blot results, we found via immunostaining that lomerizine treatment induced similar changes in the expression profiles of EndMT-associated factors in FD-VECs when compared to controls (Fig. 3b). We next used human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs) to determine whether lomerizine has the same effects in adult VECs. We previously found that treatment of Activin A in VECs recapitulates the biochemical properties of FD-VECs16. As excepted, HUVECs treated with Activin A represented hyperactivation of TGF-β signaling, reduction of KDR expression and increments of TSP1 and SNAI1 expression (Fig. 3c), mimicking the properties of FD-VECs. As results, lomerizine treatment significantly downregulated expression of SNAI1 and partially rescued the aberrant expression of other proteins in Activin A-treated HUVECs. Together, our results demonstrate that lomerizine suppresses EndMT in FD-VECs, thereby improving their angiogenic activity.

Fig. 3.

Lomerizine improves the functionality of FD-VECs by inhibiting EndMT. (a) Western blot for the EndMT-associated factors CD31, COL1A1, ACTA2, SNAI1, and TWIST in WT-VECs, untreated FD-VECs (FD), lomerizine-treated FD-VECs, and gene-corrected FD-VECs (FD(c)). Lomerizine increased CD31 and decreased EndMT-associated proteins in FD-VECs. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 4); *p < 0.05 via a Student’s t-test. Full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. 7. (b) Immunostaining of EndMT-associated factors in the cells described in (a). Lomerizine reduced the levels of EndMT-associated factors in FD-VECs. Scale bars: 50 µm. (c) The effects of lomerizine on Activin A-treated HUVECs. Western blotting of HUVEC samples was performed to detect p-SMAD2, SMAD, TSP-1, KDR, and SNAI1. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 2); *p < 0.05 via a Student’s t-test. A, Activin A. Full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. 7.

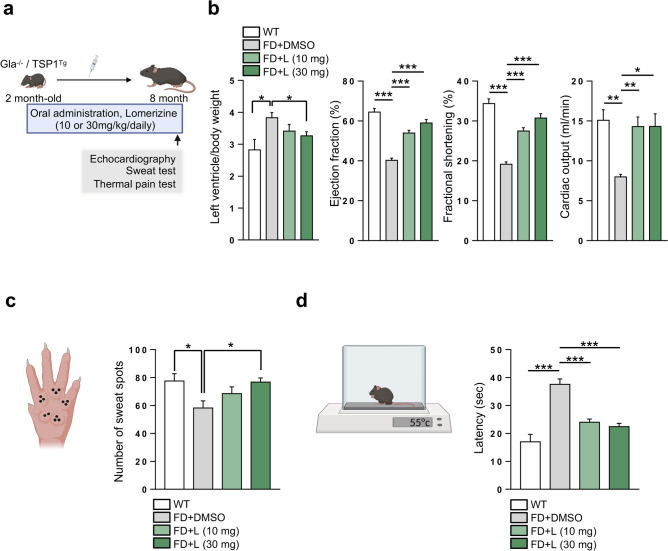

Oral administration of lomerizine rescues the FD phenotypes of FD-mice

We next tested the efficacy of lomerizine in an experimental mouse model of FD (Gla−/−/TSP1Tg), which recapitulate the vasculopathies of human FD patients17. We orally administrated lomerizine in FD-mice (10 or 30 mg/kg/day) for 6 months (Fig. 4a). No changes in body weight were detected over six months with lomerizine doses of 10 mg/kg and 30 mg/kg, indicating an absence of significant systemic toxicity at these levels (Supplementary Fig. S4a). Using echocardiography, we found that although FD-mice exhibited a higher ratio of left ventricle (LV) to body weight (BW) than WT mice, lomerizine administration reduced this LV to BW ratio (Fig. 4b). Similarly, although FD-mice exhibited reduced heart function (i.e., cardiac ejection fraction, fractional shortening, and cardiac output) compared to WT mice, long-term lomerizine administration induced significant improvements in heart function. Thus, lomerizine administration can improve the defective cardiac functionality of FD-mice. In addition, although the number of sweat spots and heat sensitivity were reduced in FD-mice compared to WT (Fig. 4c, d), lomerizine administration rescued this phenotype. Collectively, our results suggest oral administration of lomerizine alleviates several FD-like symptoms of FD-mice.

Fig. 4.

Oral administration of lomerizine rescues the FD phenotypes of FD-mice. (a) Schematic outlining the protocol by which FD-mice (Gla−/−/TSP1Tg) were treated with lomerizine (10 or 30 mg/kg/day for 6 months) before being subjected to assays like echocardiography, sweat tests, and thermal pain tests. Control FD-mice received oral DMSO. (b) Echocardiographic measurements of cardiac function in WT (n = 3) and FD-mice treated with DMSO (n = 4) or lomerizine at 10 or 30 mg/kg (n = 8 and 7 per group). The left ventricle mass/body weight, ejection fraction, fractional shortening, and cardiac output were measured. Lomerizine improved the cardiac function of FD-mice. Data are presented as means ± SEM; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 via a Student’s t-test. (c) Analysis of sweat secretion from WT and FD mice treated with or without lomerizine. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 4); *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 via a Student’s t-test. (d) Heat tolerance analysis of WT (n = 5) and FD mice treated with or without lomerizine (n = 5). Increased latency of paw withdrawal indicates hyposensitivity to thermal pain. Data are presented as means ± SEM; *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 via a Student’s t-test.

Oral administration of lomerizine alleviates fibrosis and inflammation in the renal tissues of FD-mice

Renal fibrosis is another major symptom of FD24. Pathogenic fibrosis and inflammation typically arise when VECs in various tissues (including the kidney) undergo EndMT26. We next asked how oral administration of lomerizine affects tissue fibrosis and inflammation in the renal cortex region of FD-mice by examining their expression of EndMT-related genes (Fig. 5a). We found significantly more CD31+/ACTA2+ cells in the renal tissues of FD-mice compared to WT, but oral lomerizine administration reduced this increase (Fig. 5b). FD renal tissues showed fewer CD31-positive cells and significantly more ACTA-positive cells than WT (Supplementary Fig. S4b). Lomerizine treatment reduced the proportion of ACTA-positive cells in FD renal tissues. These results indicate FD-mice do exhibit EndMT in the renal microvasculature. Lomerizine treatment downregulated the renal expression of the EndMT marker COL1A1 in FD-mice (Fig. 5c) and reduced the increased expression of the inflammation-related proteins F4/80 and LCN (Fig. 5d). Similarly, lomerizine reduced the protein levels of fibrotic and inflammatory markers in treated FD-mice compared to non-treated FD-mice (Fig. 5e). We next evaluated the impact of lomerizine on blood parameter in FD-mice. Notably, lomerizine treatment showed a trend toward reducing blood creatinine levels, suggesting a potential improvement in renal function (Supplementary Fig. S5b). Together, our results indicate lomerizine effectively suppresses the progression of renal fibrosis and inflammation in FD-mice and suggest its use should be explored for human FD patients.

Fig. 5.

Oral administration of lomerizine alleviates fibrosis and inflammation in the renal tissues of FD-mice. (a) Schematic outlining the protocol by which FD-mice (Gla−/−/TSP1Tg) were treated with lomerizine (30 mg/kg/day for 6 months) prior to the analysis of their renal tissues. Control FD-mice received oral DMSO. (b) Immunohistochemistry of CD31 and ACTA2 in renal tissues from WT (n = 3) and FD-mice (Gla−/−/TSP1Tg) administered DMSO (n = 3) or lomerizine (n = 4). Lomerizine reduced ACTA2 fluorescence from CD31 + cells in the renal tissues of FD-mice. Data are presented as means ± SEM; *p < 0.05 via a Student’s t-test. (c) Immunohistochemistry of COL1A1 in renal tissues from WT (n = 3) and FD-mice (Gla−/−/TSP1Tg) administered DMSO (n = 3) or lomerizine (n = 4). Lomerizine reduced COL1A1 fluorescence from the renal tissues of FD-mice. Data are presented as means ± SEM; *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 via a Student’s t-test. (d) Immunohistochemistry of the inflammation-associated markers F4/80 and LCN2 in renal tissues from WT (n = 3) and FD-mice (Gla−/−/TSP1Tg) administered DMSO (n = 3) or lomerizine (n = 4). Lomerizine reduced F4/80 and LCN2 florescence from the renal tissues of FD-mice. Data are presented as means ± SEM; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 via a Student’s t-test. (e) Western blot analyses of the fibrosis-related markers ACTA2 and COL1A1, the inflammation markers LCN2 and F4/80, as well as GAPDH in kidney lysates from FD-mice (Gla−/−/TSP1Tg) treated with or without lomerizine. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 3); *p < 0.05 via a Student’s t-test. Full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. 7. (f) A model for lomerizine’s mechanism of action in FD therapy.

Discussion

In this study, we present preliminary evidence suggesting lomerizine’s potential for alleviating symptoms in FD patients. We found lomerizine reduced p-SMAD2 and TSP1 in FD-VECs, while increasing KDR and eNOS. Lomerizine also reduced ROS generation and maximal respiration in FD-VECs, thereby suppressing the EndMT. Moreover, FD-mice that received oral administration of lomerizine exhibited improvements in their FD-like phenotypes, including LVH, renal fibrosis and inflammation, anhidrosis, and heat intolerance.

As FD progresses, patients typically develop vasculopathies in various tissues, including the brain, heart, and kidneys2,4,5. FD patients are commonly treated with ERT, but its effectiveness varies depending on the stage of disease and the specific GLA mutation present. Patients with advanced fibrosis or certain late-stage complications may experience limited benefits9–11,13,14. In a previous study, we observed increased expression of TSP-1 and decreased levels of the angiogenic factors KDR and eNOS in kidney biopsies from FD patients16. In the present study, we found elevated p-SMAD2 staining in renal peritubular capillaries of FD patients biopsies compared to those of normal donors (Supplementary Fig. S5a). Thus, TSP1 overexpression and p-SMAD2 signaling hyperactivation seem to be typical biochemical anomalies in the renal tissues of FD patients. Furthermore, we did not observe any recovery of FD-VEC dysfunction upon administration of ERT16. This is why we were interested in developing new therapeutic strategies for treating FD. We previously screened a library of clinical compounds for candidates that could improve the angiogenic dysfunction of FD-VECs17. Among them, we selected lomerizine for this study because of its ability to rescue tube formation capacity in FD-VECs.

Previous studies have identified increased voltage-gated calcium currents in FD-neurons, a phenomenon that is reportedly secondary to a build-up of Gb325,27. However, the involvement of calcium signaling in FD-VECs has remained unexplored. In this study, we provide the first evidence of increased mitochondrial calcium (mito-Ca2⁺) levels in FD-VECs (Fig. 2a). This novel observation highlights the dysregulation of calcium homeostasis in FD-VECs, extending the paradigm established in neuronal studies to the vascular endothelium. A recent study has shed light on how mito-Ca2⁺ contributes to EndMT and fibrosis28. Specifically, mitochondrial calcium uptake has been identified as a key driver of EndMT. Inhibiting the mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU) prevented EndMT in vitro, while conditional deletion of MCU in endothelial cells blocked mesenchymal activation in a hind limb ischemia model. These findings underscore the pivotal role of mito-Ca2⁺ in vascular remodeling and fibrosis, providing a mechanistic basis for our observations. In this context, our results reveal a mechanistic link wherein the accumulation of mito-Ca2⁺ in FD-VECs leads to the upregulation of TSP1 expression, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S2. Based on this, we propose that TSP1 might act as a mediator in the MCU-induced EndMT pathway. The accumulation of mito-Ca2⁺ upregulated TSP1 expression in VECs, and treatment of FD-VECs with lomerizine likely reduces their over-expression of TSP1, indirectly suppressing TGF-β-induced EndMT. Moreover, mito-Ca2⁺ overload amplifies ROS generation through enhanced activity of the mitochondrial electron transport chain and activation of NADPH oxidase29. This increased ROS production contributes to endothelial dysfunction and impaired angiogenesis. In support of this, we previously reported that fasudil, a compound identified in our screening, reduces ROS generation and alleviates several FD-related phenotypes, including angiogenesis defects17. Little is known, however, about whether Ca2+ signaling is part of the mechanism underlying the dysfunctional angiogenesis of FD-VECs. In our current study, we show that lomerizine treatment not only reduces mito-Ca2⁺ levels but also diminishes ROS generation and the expression of EndMT-associated genes, highlighting the importance of mito-Ca2⁺ signaling in FD-VEC dysfunction. Together, these results suggest that the defective endothelial competence of FD-VECs arises from mito-Ca2⁺ overload, which enhances ROS production and TSP1 expression, contributing to vascular dysfunction and fibrosis in FD.

Calcium overload is known to induce structural modifications in mitochondria30. Specifically, under calcium-overloaded conditions, the cristae network adopts a filamentous morphology, matrix volume expands, and Ca2+ phosphate precipitates are embedded within the matrix near cristae junctions. These ultrastructural changes are responsible for reduced ATP synthesis rates, further impairing mitochondrial function. To gain deeper insights into the mitochondrial ultrastructure in FD and the mechanisms by which lomerizine reduces calcium accumulation, cryo–electron tomography, combined with ultrastructural and histological analyses, will be invaluable. These advanced techniques can provide a more detailed understanding of the microstructural changes in Fabry mitochondria and further elucidate how lomerizine mitigates calcium-induced damage. Such studies will significantly contribute to uncovering the therapeutic mechanisms of lomerizine in FD.

Furthermore, oral administration of lomerizine is effective on the protection of LVH and the recovery of cardiac functions in FD-mice (Fig. 4b). It will be an interesting study to know how lomerizine influences the cardiac structure and function in FD-mice. Ca2⁺ in the coronary arteries plays a crucial role in regulating heart rate by influencing blood flow to the heart muscle (myocardium)31. Coronary arteries supply oxygen and nutrients to the myocardium, and the movement of calcium ions within these arteries affects vascular tone, indirectly impacting heart function and rate. Lomerizine reportedly does not affect the heart rate in mice, indicating lomerizine is ineffective to inhibit L-type Ca2+ channels in coronaries32. Because there are five distinct EC types (endocardial, coronary arterial, venous, capillary, and lymphatic) in the heart33, we supposed that lomerizine might have the therapeutic effects for FD in other EC type rather than coronaries. We previously observed aberrant expression of angiogenesis-associated factors in the renal peritubular capillaries of FD patients16. Enhanced levels of p-SMAD2 were also detected in the renal peritubular capillaries of FD patients (Supplementary Fig. S5a). From these observations, it is conceivable that FD complications in several organs such as heart and kidney might be originated from dysfunction of capillary ECs. Notably, we found that the lomerizine administration improves the cardiac function of FD-mice (Fig. 4b) and decreases the expression of fibrosis-related genes in capillary of renal cortex region (Fig. 5). Despite of insufficient supporting data, hence, it is likely that lomerizine acts to alleviate cardiac and renal FD manifestations via restoration of dysfunctional FD-VECs, especially in the capillary.

Furthermore, we found that lomerizine rescues anhidrosis and heat intolerance in FD-mice (Fig. 4c, d). Lomerizine is currently being used clinically for the treatment of neurological pain syndromes, such as migraines18. Many FD patients experience acroparaesthesia during childhood, which often progresses to more severe peripheral neuropathy with age34. Because FD-mice given oral lomerizine show rescued heat intolerance and anhidrosis which are symptoms of autonomic neuropathy, Given the role of calcium signaling and mitochondrial dysfunction in peripheral neuropathies, it is plausible that lomerizine’s effects observed in FD-VECs could extend to neuronal contexts. However, this hypothesis warrants further exploration in specific models of FD-associated neuropathy.

Next, we investigated the effects of lomerizine on human adult vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs), which are relatively more mature than VECs differentiated from iPSCs. Interestingly, we found lomerizine did not activate KDR expression in Activin A-treated HUVECs (Fig. 3c). KDR is rarely expressed in mature human endothelial cells35. Thus, lomerizine seems to influence KDR expression in the maturation process of FD-VECs. Nonetheless, lomerizine reduced TSP-1 and p-SMAD2 levels in both Activin A-treated HUVECs and VECs isolated from FD-mouse kidney (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. S6a). These data demonstrate that lomerizine downregulates anti-angiogenic factors in adult FD-VECs as well. Extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition in vessel walls leads to deficient local blood supply and damages of parenchymal cells (e.g., hepatocytes and glomerular and tubular epithelial cells), which eventually results in organ dysfunction36. Ischemia is resulted from deficient blood supply to tissues37. Although overexpression of fibrosis-associated genes was detected in FD models, lomerizine treatment downregulated the expression of those genes in FD-VECs and renal tissues of FD-mice (Fig. 3 and Fig. 5). Therefore, lomerizine might also have the therapeutic effect to alleviate the ischemia in FD. In conclusion, our results demonstrate that lomerizine effectively modulates mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS production in VECs, which may have implications for the development of future FD therapies. Validation in clinical settings will be necessary to establish its therapeutic potential.

We also tested whether lomerizine influences Gb3 clearance through immunostaining, but did not observe a significant reduction in Gb3 aggregates after treatment (Supplementary Fig. S6b) These results indicate that the beneficial effects of lomerizine may not be related to Gb3 clearance, but are likely due to its role in rescuing vascular function. Considering this, we believe that combining lomerizine with existing treatments, such as ERT, could potentially lead to a more effective therapeutic strategy. By addressing both Gb3 accumulation and vascular function, this combined approach might offer enhanced benefits in treating the condition.

FD presents diverse phenotypes due to various pathogenic variants, affecting both males and females38. We focused on the most common genotype in male models, as they exhibit more severe symptoms, providing a strong foundation for evaluating lomerizine’s therapeutic potential. Future studies will expand to include females, non-classical phenotypes, and other variants to ensure the broad applicability of lomerizine. Exploring this diversity will be essential for developing personalized and inclusive treatment strategies for FD patients.

Together, our findings indicate that lomerizine helps restore the primary vascular dysfunctions of FD. Based on our findings, we propose a model explaining the lomerizine’s mechanism of action in FD models (Fig. 5f). By inhibiting Ca2+ influx, lomerizine reduces mito-Ca2+ overload and oxidative stress, downregulates TSP1 and p-SMAD2 levels, and subsequently suppresses TGF-induced EndMT. This series of biochemical changes triggered by lomerizine in VECs suggests its potential to mitigate key pathological features of FD. However, further investigations are needed to assess its translational applicability as a candidate for FD therapy.

Materials and methods

Study approval

All experiments using human iPSCs (hiPSCs) were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (The protocol title: Development of platform technology for rare disease-specific organoids and its application; approval number KH2018-114; Jan 10, 2022). For all experiments using mice, the animal protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Daegu-Gyeongbuk Medical Innovation Foundation (The protocol title: Efficacy test for hit to lead in Fabry disease mouse model; approval number KMEDI-22060902-00; June 9, 2022). All experiments were conducted under the guidelines established by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC). All methods are reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Maintenance of FD-iPSCs

A wild-type (WT)- and FD-iPSCs were previously generated from their respective human dermal fibroblasts16. Each FD-iPSC line having different GLA mutations were employed in this study (Supplementary Table S1). FD isogenic iPSC line was characterized in our previous report39 and was used as controls with WT-iPSCs. hiPSCs were cultured in mTeSR1 medium (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) on Matrigel (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ)-coated culture dishes at 37 °C under 5% CO2. hiPSC colonies were maintained at a 1:50 ratio using Accutase solution after 7 days (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) and incubated in the same culture conditions for expansion.

Differentiation of FD-iPSCs into VECs

VECs were differentiated from human iPSCs as previously described40,41. Briefly, hiPSCs were maintained for 2 days in VEC medium (RPMI (HyClone, Logan, MI) supplemented with 1% B27 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen), 50 ng/ml Activin A (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ), 20 ng/ml BMP4 (PeproTech), and 3 μM CHIR990921 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 37 °C under 5% CO2. Next, the cells were maintained for 3 days in VEC medium supplemented with 50 ng/ml VEGF-A (PeproTech) and 50 ng/ml bFGF at 37 °C under 5% CO2. To differentiate the vascular progenitors into VECs, CD31+ cells were sorted from the differentiated cells using CD31+ Dynabeads (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The CD31+ cells were cultured on gelatin-coated plates and incubated for 3 days with daily medium changes in EGM-2 medium (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) containing 100 ng/ml VEGF-A and 50 ng/ml bFGF at 37 °C under 5% CO2. Finally, the vascular progenitors were cultured for 4 days with daily changes of EGM-2 medium without growth factors.

Screening clinical compounds using FD-VECs

Drug screening was carried out using FD-VECs as previously described17. Briefly, to screen clinical compounds for those that improve FD-VEC dysfunction, VECs were plated on gelatin-coated 96-well plates (SPL lifesciences, Pocheon, Korea) at a density of 3 × 103 cells/cm2 and cultured in EGM-2 medium without growth factors for 24 h. First, the FD-VECs were treated with each compound at a concentration of 5 μM for 24 h. Then, those compounds that still permitted normal FD-VEC viability and morphology were selected for further study. Next, FD-VECs treated with each compound were subjected to a tube-like structure formation assay on Matrigel-coated plates. The assay was repeated at least three times with FD-VECs treated with different concentrations (0.5, 1, and 5 μM) of each selected compound.

Tube-like structure assay

After 96-well plates were coated with 80 μl of Matrigel matrix (BD Biosciences) on ice for 20 min, they were incubated at 37 °C under 5% CO2 overnight. VECs were detached after treatment with Accutase solution at 37 °C for 5 min. Detached cells (1 × 104) were transferred to the Matrigel-coated 96-well plates and incubated in EGM-2 medium supplemented with 100 ng/ml VEGF-A at 37 °C under 5% CO2 for 24 h. An inverted microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used to acquire images of the resulting vascular tube-like structures. Total tube length was analyzed using ImageJ software (NIMH, Bethesda, MD) with the Angiogenesis Analyzer plugin42.

Western blotting

Western blotting was carried out as previously described43. For cell lysis, the cells were added to RIPA buffer (GenDEPOT, Katy, TX) supplemented with a protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (GenDEPOT) and subjected to gentle agitation at 4 °C for 2 h. For tissue lysis, the tissues were homogenized in lysis buffer using a Dounce Tissue Grinder (Wheaton Millville, NJ) with gentle agitation at 4 °C for 2 h. After the samples were centrifuged at 16,000×g for 15 min, the supernatants were collected, and their protein concentrations were measured using the Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The lysates were then denatured in SDS-PAGE buffer at 95 °C for 5 min. Each sample was separated on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel by electrophoresis and then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Whatman, Maidstone, England). After blocking in TBST buffer containing 5% BSA for 1 h, the membranes were incubated with primary antibody at 4 °C overnight. Then, after being washed with TBST, the membranes were incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) at room temperature (RT) for 1 h. After washing in TBST, the membranes were developed using the ECL reagent (Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA) and imaged with a LAS-4000 Mini Biomolecular Imager (Fuji Film, Tokyo, Japan). The intensity of each band was measured using ImageJ software (NIMH). The primary antibodies used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Immunostaining

Immunostaining of cultured cells was performed as previously described43. Briefly, cells were fixed in 10% formalin solution (Sigma) for 30 min and then permeabilized in PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma). After blocking with 2% BSA for 1 h, the cells were incubated with each primary antibody at 4 °C overnight. After washing with PBST (PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20), the samples were incubated with secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 488, 594, 647; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) at RT for 1 h. Then, the samples were counterstained with 4ʹ-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Sigma) before being examined on a Zeiss LSM 800 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss).

For tissue immunostaining, the mice were anesthetized with avertin (0.2 g/ml, Sigma) by i.p. injection. The mice were then perfused with DPBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA, Wako, Richmond, VA). After post-fixation of the excised tissues in 4% PFA at 4 °C overnight, the resulting samples were incubated in DPBS with 30% sucrose (Sigma) at 4 °C overnight. For frozen sections, the tissues were embedded in Optimal Cutting Temperature compound (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and frozen at -20 °C for 3 h. The frozen tissues were cut into 20-μm sections using a cryostat (Leica Biosystems). For immunofluorescence staining, the sections were permeabilized with blocking buffer (PBS containing 5% normal donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) and 1% Triton X-100 (Sigma)) at RT for 1 h. Then, the samples were incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. After washing six times with PBS, the samples were incubated with secondary antibodies and DAPI in blocking buffer at RT for 1 h. After another 6 rounds of washing, the samples were mounted in fluorescent mounting medium (Dako) under glass coverslips and examined on a Zeiss LSM 980 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss). (Carl Zeiss). The primary antibodies used are listed in Supplementary Table S3. All images were measured above threshold and normalized to the cell area using ImageJ. As previously reported, the Distance Analysis (DiAna) plugin was used for analyzing the colocalization and number of CD31+ACTA2+ cells44.

Flow cytometry

VECs were harvested using Accutase at 37 °C for 5 min. The cells were centrifuged at 300×g for 5 min, resuspended in FACS buffer (PBS containing 2% FBS), and filtered using a cell strainer with 40-μm pores (SPL lifesciences, Pocheon, Korea). Then, the cells were incubated with Rhod-2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or isotype controls (Biolegend, San Diego, CA) at 4 °C for 30 min. After five washes with FACS buffer, the samples were examined using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). The proportion of Rhod-2-positive VECs was determined using the FlowJo software package (Tree star, Ashland, OR).

Measurement of ROS in VECs

The CellROX Green Reagent (Invitrogen) was used for ROS detection according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For confocal images, VECs (2 × 104 cells) were plated in glass bottom dishes (SPL lifesciences). For measurement of fluorescent intensity of CellROX, VECs (3 × 104 cells) were plated in 24-well glass-bottomed plates. VECs were pre-incubated in EGM-2 medium supplemented with each clinical compound at 37 °C under 5% CO2 for 24 h. Then, 5 μM CellROX Green Reagent was added and the cells were incubated for an additional 3 h. After three rounds of washing with PBS, the samples were fixed in 10% formalin solution for 30 min. After counterstaining with 4ʹ-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Sigma), the fluorescence intensity induced by ROS was measured using a TECAN Spark microplate reader (TECAN, Männedorf, Switzerland) and normalized to each well’s DAPI number.

Measuring the oxygen consumption rate (OCR) of VECs

An XF96 Extracellular Flux Analyzer and the XF Cell Mito Stress Test Kit (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA) were used to measure the OCR of VECs according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, VECs (1.5 × 104) were transferred to XF 96-well culture plates and incubated in EGM-2 medium supplemented with Lomerizine (Selleckchem, S4084, 1 μM) for 24 h. The cells were preincubated with XF DMEM media (pH 7.4) containing 10 mM glucose, 1 mM pyruvate, and 2 mM glutamine for 1 h before the measurements. After sequential treatment with 3 μM oligomycin, 1 μM FCCP, and 1.5 μM rotenone/antimycin A, the OCR was determined and then normalized using a BCA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Real-time qPCR

Total RNA was obtained from cells using the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Reverse transcription was performed using 1 μg of total RNA and a cDNA synthesis kit (Solgent, Daejeon, Korea) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Real-time qPCR was carried out using the SYBR Green Realtime PCR Master Mix (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan). The qPCR reactions were conducted on a CFX-Connect Real-Time System (Bio-Rad) with 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C, annealing at 60 °C, and elongation at 72 °C. The expression of the target genes was normalized using the GAPDH transcription level. The difference between the GAPDH threshold cycle (Ct) and the target Ct was calculated as the ΔCt value. Fold-changes in the levels of mRNA expression between the samples and the controls were determined using the formula 2−(SΔCt−CΔCt). The primers used are listed in Supplementary Table S4.

Animals

Gla−/− mice and TSP1Tg mice were obtained from the DGMIF. To generate Gla−/−/TSP1Tg mice, Gla−/− mice were crossed with TSP1Tg mice. All mouse lines were maintained in the C57BL/6 background. Only male mice were used for all the experiments in this study. For oral administration of lomerizine, 10 or 30 mg/kg/day was dissolved in DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich).

Echocardiography

Echocardiographic measurements were conducted using the Vevo 3100 Imaging System coupled to a 30-MHz linear-frequency transducer (FUJIFILM VisualSonics, Canada) as previously reported45. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (JSK Co., Suwon-si, Korea) and fixed in a supine position. To examine their baseline heart rate, the isoflurane concentration was reduced to 1–2%. Next, the mice were depilated using hair removal cream and the appropriate areas were covered with pre-warmed ultrasound gel (Parker Laboratories, NJ). After the mice were placed on their chests, B- and M-Mode images were taken along the parasternal long axis and the short axis. A speckle tracking echocardiography (STE) analysis of the B-Mode images was carried out in a semiautomatic manner using the VevoStrain software package (FUJIFILM VisualSonics). Cardiac systolic function was also determined in a semiautomatic manner from the B-mode images (long axis view) using the monoplane Simpson disk summation method. The acquired M-Mode images of the parasternal long axis view were used to calculate each heart’s LV dimensions and LV mass. Three independent M-Mode images and 3 cardiac cycles were analyzed to determine diastolic function and diastolic wall strain (DWS) according to published methods46.

Measurement of hypohidrosis

Mice were also anesthetized as described above for the sweat secretion assay. The right hind paw was painted with an iodine solution (2% in EtOH; Sigma-Aldrich). Once dried, the paw surface was covered with a starch suspension (0.5 g/mL in mineral oil; Sigma-Aldrich)47. Sweating was stimulated by intraperitoneal injection of pilocarpine hydrochloride (2 mg/kg body weight). After 5 min, images of the paws were taken, and black dots were counted as functional sweat gland pores. ImageJ was used to count the black dots on each paw and calculate their areas48.

Measurement of peripheral sensory function using the hot plate test

Nociceptive responses to heat stimulation were measured according to published methods49. Each mouse was placed individually on a 55 °C hot plate (Allforlab Inc., Seoul, Korea) and the latency until it responded with a characteristic hind paw shake was recorded. If no response was evident by 60 s, the mouse was removed to prevent injury.

Statistical analysis

All generated data, apart from outliers, were analyzed. Outliers were identified via a statistical test (ROUT) using GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Each experiment was repeated at least three times. Data are presented as means ± SEM. Statistical significance was evaluated using a two-tailed Student’s t-test in GraphPad Prism 7; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank the KAIST Analysis Center for Research Advancement (KARA) for help with confocal microscopy. The chemical library used in this study was kindly provided by the Korea Chemical Bank (http://www.chembank.org) of the Korea Research Institute of Chemical Technology. Illustrations of experimental schemes were generated using the BioRender program (http://www.biorender.com).

Author contributions

J.B.C.: conception, design, data assembly, data analysis (drug screening, immunostaining, western blot, ROS analysis, and immunohistochemistry), interpretation, and manuscript writing. H.-S.D.: conception, design, data assembly, and data analysis (drug screening, Ca2+ influx assay, FACS, immunostaining, western blot, ROS analysis). D.-W.S.: conception, design, data assembly, and data analysis (oral administration, echocardiography, sweat secretion assay, and hot-plate test). H.-Y.Y.: conception, design (generation of FD-mice). T-M.K.: data assembly, data analysis (OCR analysis). H.J.G.: data assembly (immunohistochemistry). Y.G.B., J.J.P.: data assembly, data analysis (immunohistochemistry and perfusion). J.-M.P.: oral administration, design, data assembly. W.-S.C., J.M.S., B.H.L.: design, interpretation. G.B.W., Y.-M.H.: management of the project and manuscript writing. All authors have agreed to be listed as authors and reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by grants (21C0726L1 & 21A0402L1-12) from the Korean Fund for Regenerative Medicine (KFRM).

Data availability

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Jong Bin Choi, Hyo-Sang Do and Dong-Won Seol.

Contributor Information

Beom Hee Lee, Email: bhlee@amc.seoul.kr.

Gabbine Wee, Email: gabbine@kmedihub.re.kr.

Yong-Mahn Han, Email: ymhan@kaist.ac.kr.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-94795-4.

References

- 1.Lukas, J. et al. Functional characterisation of alpha-galactosidase a mutations as a basis for a new classification system in Fabry disease. PLoS Genet.9, e1003632. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003632 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rombach, S. M. et al. Vascular aspects of Fabry disease in relation to clinical manifestations and elevations in plasma globotriaosylsphingosine. Hypertension60, 998–1005. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.195685 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orteu, C. H. et al. Fabry disease and the skin: Data from FOS, the Fabry outcome survey. Br. J. Dermatol.157, 331–337. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08002.x (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schiffmann, R. et al. Fabry disease: Progression of nephropathy, and prevalence of cardiac and cerebrovascular events before enzyme replacement therapy. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl.24, 2102–2111. 10.1093/ndt/gfp031 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehta, A. et al. Fabry disease defined: Baseline clinical manifestations of 366 patients in the Fabry Outcome Survey. Eur. J. Clin. Investig.34, 236–242 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rombach, S. M. et al. Vasculopathy in patients with Fabry disease: Current controversies and research directions. Mol. Genet. Metab.99, 99–108. 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.10.004 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eng, C. M. et al. Safety and efficacy of recombinant human α-galactosidase a replacement therapy in Fabry’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med.345, 9–16. 10.1056/NEJM200107053450102 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schiffmann, R. et al. Enzyme replacement therapy in Fabry disease a randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Med. Assoc.285, 2743–2749. 10.1001/jama.285.21.2743 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilcox, W. R. et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of enzyme replacement therapy for Fabry disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet.75, 65–74 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weidemann, F. et al. Long-term effects of enzyme replacement therapy on Fabry cardiomyopathy: Evidence for a better outcome with early treatment. Circulation119, 524–529 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Germain, D. P. et al. Sustained, long-term renal stabilization after 54 months of agalsidase beta therapy in patients with Fabry disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol.18, 1547–1557. 10.1681/asn.2006080816 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lenders, M. & Brand, E. Fabry disease: The current treatment landscape. Drugs81, 635–645. 10.1007/s40265-021-01486-1 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young-Gqamana, B. et al. Migalastat HCl reduces globotriaosylsphingosine (lyso-Gb3) in Fabry transgenic mice and in the plasma of Fabry patients. PLoS ONE8, e57631. 10.1371/journal.pone.0057631 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Germain, D. P. et al. Safety and pharmacodynamic effects of a pharmacological chaperone on α-galactosidase A activity and globotriaosylceramide clearance in Fabry disease: Report from two phase 2 clinical studies. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis.7, 91. 10.1186/1750-1172-7-91 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ebert, A. D., Liang, P. & Wu, J. C. Induced pluripotent stem cells as a disease modeling and drug screening platform. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol.60, 408–416. 10.1097/FJC.0b013e318247f642 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Do, H. S. et al. Enhanced thrombospondin-1 causes dysfunction of vascular endothelial cells derived from Fabry disease-induced pluripotent stem cells. EBioMedicine52, 102633. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102633 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi, J. B. et al. Fasudil alleviates the vascular endothelial dysfunction and several phenotypes of Fabry disease. Mol. Ther.31, 1002–1016. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2023.02.003 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamaki, Y. et al. Effects of lomerizine, a calcium channel antagonist, on retinal and optic nerve head circulation in rabbits and humans. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci.44, 4864–4871. 10.1167/iovs.02-1173 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fitzgerald, M. et al. Secondary retinal ganglion cell death and the neuroprotective effects of the calcium channel blocker lomerizine. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci.50, 5456–5462. 10.1167/iovs.09-3717 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Görlach, A., Bertram, K., Hudecova, S. & Krizanova, O. Calcium and ROS: A mutual interplay. Redox Biol.6, 260–271. 10.1016/j.redox.2015.08.010 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen, J.-S. et al. Globotriaosylceramide induces oxidative stress and up-regulates cell adhesion molecule expression in Fabry disease endothelial cells. Mol. Genet. Metab.95, 163–168. 10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.06.016 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piera-Velazquez, S. & Jimenez, S. A. Endothelial to mesenchymal transition: Role in physiology and in the pathogenesis of human diseases. Physiol. Rev.99, 1281–1324. 10.1152/physrev.00021.2018 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thuan, D. T. B. et al. A potential link between oxidative stress and endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in systemic sclerosis. Front. Immunol.9, 1985. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01985 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weidemann, F. et al. Fibrosis: A key feature of Fabry disease with potential therapeutic implications. Orphanet J. Rare Dis.8, 116. 10.1186/1750-1172-8-116 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi, L. et al. The Fabry disease-associated lipid Lyso-Gb3 enhances voltage-gated calcium currents in sensory neurons and causes pain. Neurosci. Lett.594, 163–168. 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.01.084 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma, J., Sanchez-Duffhues, G., Goumans, M.-J. & ten Dijke, P. TGF-β-induced endothelial to mesenchymal transition in disease and tissue engineering. Front. Cell Dev. Biol.10.3389/fcell.2020.00260 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klein, T. et al. Small fibre neuropathy in Fabry disease: A human-derived neuronal in vitro disease model and pilot data. Brain Commun.10.1093/braincomms/fcae095 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lebas, M. et al. Integrated single-cell RNA-seq analysis reveals mitochondrial calcium signaling as a modulator of endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Sci. Adv.10, eadp6182. 10.1126/sciadv.adp6182 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dikalov, S. Cross talk between mitochondria and NADPH oxidases. Free Radic. Biol. Med.51, 1289–1301. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.06.033 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walkon, L. L., Strubbe-Rivera, J. O. & Bazil, J. N. Calcium overload and mitochondrial metabolism. Biomolecules10.3390/biom12121891 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo, M. & Anderson, M. E. Mechanisms of altered Ca2+ handling in heart failure. Circ. Res.113, 690–708. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301651 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toriu, N. et al. Lomerizine, a Ca2+ channel blocker, reduces glutamate-induced neurotoxicity and ischemia/reperfusion damage in rat retina. Exp. Eye Res.70, 475–484. 10.1006/exer.1999.0809 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ishii, Y., Langberg, J., Rosborough, K. & Mikawa, T. Endothelial cell lineages of the heart. Cell Tissue Res.335, 67–73. 10.1007/s00441-008-0663-z (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.MacDermot, K. D., Holmes, A. & Miners, A. H. Anderson-Fabry disease: clinical manifestations and impact of disease in a cohort of 98 hemizygous males. J. Med. Genet.38, 750–760. 10.1136/jmg.38.11.750 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bompais, H. et al. Human endothelial cells derived from circulating progenitors display specific functional properties compared with mature vessel wall endothelial cells. Blood103, 2577–2584. 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2770 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao, X., Chen, J., Sun, H., Zhang, Y. & Zou, D. New insights into fibrosis from the ECM degradation perspective: the macrophage-MMP-ECM interaction. Cell Biosci.12, 117. 10.1186/s13578-022-00856-w (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kalogeris, T., Baines, C. P., Krenz, M. & Korthuis, R. J. Cell biology of ischemia/reperfusion injury. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol.298, 229–317. 10.1016/b978-0-12-394309-5.00006-7 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ortiz, A. et al. Fabry disease revisited: Management and treatment recommendations for adult patients. Mol. Genet. Metab.123, 416–427. 10.1016/j.ymgme.2018.02.014 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choi, J. B., Seo, D., Do, H.-S. & Han, Y.-M. Generation of a CRISPR/Cas9-corrected-hiPSC line (DDLABi001-A) from Fabry disease (FD)-derived iPSCs having α-galactosidase (GLA) gene mutation (c.803_806del). Stem Cell Res.66, 103001. 10.1016/j.scr.2022.103001 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park, S. W. et al. Efficient differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into functional CD34+ progenitor cells by combined modulation of the MEK/ERK and BMP4 signaling pathways. Blood116, 5762–5772. 10.1182/blood-2010-04-280719 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Orlova, V. V. et al. Generation, expansion and functional analysis of endothelial cells and pericytes derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Protoc.9, 1514–1531. 10.1038/nprot.2014.102 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carpentier, G. Contribution: angiogenesis analyzer. ImageJ News5, 2012 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi, J. B. et al. Dysregulated ECM remodeling proteins lead to aberrant osteogenesis of Costello syndrome iPSCs. Stem Cell Rep.16, 1985–1998. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2021.06.007 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gilles, J. F., Dos Santos, M., Boudier, T., Bolte, S. & Heck, N. DiAna, an ImageJ tool for object-based 3D co-localization and distance analysis. Methods115, 55–64. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2016.11.016 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pappritz, K. et al. Speckle-tracking echocardiography combined with imaging mass spectrometry assesses region-dependent alterations. Sci. Rep.10, 3629. 10.1038/s41598-020-60594-2 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Selvaraj, S. et al. Diastolic wall strain: A simple marker of abnormal cardiac mechanics. Cardiovasc. Ultrasound12, 40. 10.1186/1476-7120-12-40 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tafari, A. T., Thomas, S. A. & Palmiter, R. D. Norepinephrine facilitates the development of the murine sweat response but is not essential. J. Neurosci.17, 4275–4281. 10.1523/jneurosci.17-11-04275.1997 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gagnon, D. et al. Modified iodine-paper technique for the standardized determination of sweat gland activation. J. Appl. Physiol.1985(112), 1419–1425. 10.1152/japplphysiol.01508.2011 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marshall, J. et al. Substrate reduction augments the efficacy of enzyme therapy in a mouse model of Fabry disease. PLoS ONE5, e15033. 10.1371/journal.pone.0015033 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.