Abstract

Midbrain dopamine (DA) neurons are essential for regulating movement, emotion, and reward, with their dysfunction closely linked to Parkinson’s disease (PD). While DA neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) and ventral tegmental area (VTA) have known overlapping roles in behaviors such as depression and reward, their distinct contributions to subtle spontaneous behaviors remain insufficiently understood. In this study, we utilized a 3D behavioral analysis platform powered by machine learning to explore motor and nuanced behavioral changes in a subacute MPTP mouse model of PD. This investigative approach was combined with cell-type-specific genetic ablation of DA neurons in both the SNc and VTA. Our findings highlight significant deficits in rearing, walking, and hunching behaviors correlated with the loss of SNc DA neurons, but not VTA DA neurons, alongside increased overall movement, reduced movement precision, and pronounced right-sided lateralization. These subtle features, particularly rearing deficits and lateralization, emerge as critical behavioral biomarkers of SNc DA neuron loss, thereby enhancing the translational relevance of PD models.

Subject terms: Neuroscience, Diseases

Introduction

Midbrain dopamine (DA) neurons are integral to the regulation of voluntary movement, emotion, and reward, and their dysfunction is implicated in a variety of neuropsychiatric disorders, most notably Parkinson’s disease (PD) [1–5]. Within the midbrain, DA neurons are largely concentrated in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) and the ventral tegmental area (VTA), each playing varied roles in neural regulation [6]. DA neurons in the VTA primarily influence emotion and reward processing by innervating the ventral striatum and prefrontal cortex through the mesocorticolimbic pathway [7–9]. In contrast, SNc DA neurons project to the dorsal striatum via the nigrostriatal pathway, playing a crucial role in voluntary movement control. The loss of SNc DA neurons is a well-established hallmark of PD, manifesting as the classic motor symptoms: resting tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural instability [10–12].

However, recent evidence challenges the clear-cut functional dichotomy between SNc and VTA DA neurons. Emerging research suggests that these neurons may have overlapping roles in regulating behaviors related to movement, depression, reward, and aversion [13, 14]. This overlap implies that SNc DA neurons may engage in functions beyond motor control, suggesting a more complex relationship between neuronal location and function than traditionally understood. This nuance underscores a critical need to refine our understanding of DA neuron functionality to develop better therapeutic strategies for PD and related disorders.

The MPTP (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine) model is extensively used in PD research due to its ability to reliably induce nigrostriatal dopaminergic degeneration, closely replicating PD-like symptoms in humans and non-human primates [15–17]. The MPTP mouse model is also considered the most commonly used in vivo platform for screening novel drug therapies for PD [18]. Specifically, the subacute MPTP regimen can induce moderate neuronal damage, along with the stable loss of striatal DA levels and DA neuron number in the SNc [17]. This localized neurotoxic effect on DA neurons provides a valuable tool to study the differences between the SNc and the VTA. However, behavioral variations have been observed in MPTP-treated rodents, especially with the subacute regimen. Unlike typical PD symptoms, subacute MPTP regimen failed to induce motor deficits, but instead resulted in locomotor hyperactivity as reported in previous studies [18–21]. These behavioral discrepancies suggest that current locomotor characteristics may not fully encapsulate the complexities of SNc DA neuron dysfunction in the MPTP model, highlighting the need for more refined behavioral analysis methods. Additionally, advances in genetically engineered mouse models, such as those using Cre-loxP systems for targeted neuron ablation, now offer more precise tools to dissect specific contributions of these neuronal populations [22, 23].

Traditional behavioral tests, including the open field test, rotarod test, and balance beam test, have been pivotal in identifying motor and emotional abnormalities in PD models [24–28]. While these methodologies have yielded important insights, they often rely on subjective assessments and are labor-intensive, limiting their reliability and scalability. Although automated algorithms and software have improved the analysis of rodent behavior, significant challenges remain in capturing fine behavioral details and mitigating stress-induced alterations. The advent of artificial intelligence has transformed behavioral recognition and kinematics quantification through machine learning, enabling the detection of subtle behavioral changes that might indicate DA neuron lesions in the SNc [29, 30]. These technological advances significantly enhance the translational value of animal models in understanding complex diseases such as PD [31–33].

In our study, we leveraged this technology to uncover distinct behavioral alterations specific to DA neuron loss in the SNc, observed through the subacute MPTP mouse model. We revealed significant deficits in rearing, walking, and hunching behaviors that strongly correlate with the loss of tyrosine hydroxylase-positive (TH+) neurons in the SNc, as opposed to the VTA, underscoring region-specific impacts. Using advanced machine learning analyses, we further discovered increased overall movement but decreased precision and notable right-sided lateralization in MPTP-treated mice. These subtle behavioral features, particularly rearing deficits and lateralization, emerged as valuable behavioral biomarkers for SNc DA neuron loss, thus enhancing our understanding of PD models and their translational potential.

Our findings underscore the importance of subtle behavioral markers in advancing PD research and offer a more nuanced understanding of DA neuron functionality. By focusing on these indicators, future research could lead to more targeted therapies and improved outcomes for individuals with PD.

Materials and methods

Animals

Adult (6–8 weeks old) male C57BL/6J mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories, Zhejiang, China, and DAT-ires-Cre mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Jax No. 006660). All of the mice were group-housed (5 mice per cage) in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) environment at 22–25 °C with 40–70% humidity and allowed ad libitum to food and water maintained on a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle, with lights on at 8 a.m.

MPTP mouse model of Parkinson’s disease

The subacute administration of MPTP was used to induce the DA lesions in the SNc, which serves as a mouse model of Parkinson’s Disease. In brief, mice were randomized into the MPTP group and the PBS group. Mice in the MPTP group received an intraperitoneal injection of MPTP·HCl (Sigma-Aldrich, M0896, dissolved in PBS) at a dose of 30 mg/kg daily for 5 consecutive days. Conversely, mice in the PBS group received equivalent volume vehicle injections following the same schedule.

Virus injection

DAT-ires-Cre mice and AAV2-Flex-taCasp3-TEVP were utilized to induce the selective ablation of DA neurons in the SNc or VTA. Mice were randomized into the C group (control, sham operated), the V group (VTA ablation, single injection in the VTA) and the S group (SNc ablation, bilateral injection in the SNc). In general, mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital (i.p., 80 mg/kg) and then placed in a stereotaxic apparatus (RWD, China). The skull above the targeted area was thinned with a dental drill and gently removed to create a window for surgical access. Injections were performed using a 10 μL syringe connected to a 33-Ga needle (Neuros; Hamilton, Reno, USA) controlled by a microsyringe pump (UMP3/Micro4, USA) at a slow rate to ensure accurate delivery. The volume and coordinates for virus injection were as follows. VTA (total volume of 400 nl): anterior posterior (AP), −3.50 mm; medial lateral (ML), −0.40 mm; dorsoventral (DV), −4.10 mm. SNc (total volume of 700 nl, 350 nl for each side): AP, −3.25 mm; ML, ±1.20 mm; DV, −4.25 mm. Behavioral experiments were conducted at least 4 weeks post-virus injection to allow for sufficient expression of the viral construct.

Tissue preparation

One week after the completion of spontaneous behavior analysis, mice were deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital (i.p., 80 mg/kg) and then transcardially perfused with 10× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) using a peristaltic pump. Following perfusion, the brains were rapidly removed and immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at 4 °C overnight for post-fixation. After discarding the fixative solution, the brains were transferred to a 30% sucrose solution diluted in PBS for equilibration over 3 days. Brains were embedded in Tissue Tek OCT compound (Sakura Finetek, USA) and then stored at −20 °C. The entire SNc and VTA from each brain were serially sliced at a thickness of 40 μm using a cryostat microtome (Leica CM1950, Germany) in a coronal orientation.

Immunofluorescence staining

To determine the relative number of DA neurons in the SNc and VTA, midbrain slices were blocked and permeabilized in PBS buffer containing 5% normal goat serum and 0.3% Triton ×−100 for 1 h at room temperature. After blocking and permeabilization, the slices were washed three times with PBS, then incubated with mouse anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (TH, MAB318, Millipore; 1:500 in PBS buffer containing 0.1% Triton ×-100) overnight at 4 °C. Then, the slices were washed three times with PBS, then incubated with goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 (A28175, ThermoFisher; 1:500 in PBS buffer) for 1 h and DAPI (1:5000 in PBS buffer, 4083S, Cell Signaling Technology, USA) for 5 min in the absence of light at room temperature. Finally, the slices were washed three times with PBS to remove unbound secondary antibody and DAPI.

Fluorescence microscopy

Stained slices were scanned using an Olympus VS120 Slide Scanner (16-bit Fluorescence; Olympus XM10 Monochrome Camera, Japan). Images were acquired directly using a UPLSAPO 10× objective lens (air, numerical aperture, NA, 0.4) and were taken sequentially using different fluorescence filters to capture the signals in DAPI and Alexa Fluor 488. To ensure consistency across experiments, detection levels were set identically for each slice treated with the same fluorescent dye.

Open field test

The open field test was conducted using an open field apparatus constructed from white Plexiglas, measuring 50 × 50 × 50 cm. To minimize stress during testing, mice were moved to the test room for a 30 min acclimation period prior to the start of the experiment. Each mouse was gently placed at the center of the open field and allowed to explore freely for 15 min. The movements were recorded by a video recorder positioned above the apparatus and data from the last 10 min were used for analysis. The apparatus was thoroughly cleaned with 25% ethanol following each mouse’s test to prevent any residual effects between trials.

Rotarod test

A rotarod apparatus (XR-6C, Shanghai XINRUAN Information Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was utilized to assess the movement ability of mice. The rotarod has a diameter of 30 mm and features programmable settings that allow for uniform acceleration during rotation while automatically recording the falling speed of the mice. To acclimatize the mice to the apparatus and ensure reliable performance, mice were trained on the rotarod one day before the test by being placed on the device at a constant speed of 4 r.p.m. for 300 s. On the test day, each mouse was placed on the rotarod, which was then started to accelerate uniformly from 0–4 r.p.m. over a period of 60 s. If a mouse fell during this initial phase, it was promptly returned to the rotarod. Once the speed reached 4 r.p.m., the rotarod was programmed to accelerate further from 4–40 r.p.m. within a span of 300 s, with the apparatus automatically recording the speeds at which the mice fell. Each mouse was tested three times, with an interval of at least 30 min between each test.

Spontaneous behavior analysis

The setup of this experiment and data analysis were adapted from a previous study [34]. A circular open field was constructed with transparent acrylic walls and a white plastic base, measuring 50 cm in diameter and 50 cm in height. This setup was centered on a movable stainless-steel support framework measuring 90 × 90 × 75 cm. Four Intel RealSense D435 cameras were mounted at orthogonal angles on the pillars of the shelf to capture video footage from multiple perspectives. A thick, dull-polished black rubber mat was paved between the circular open field and steel shelf to prevent light reflection. Atop the shelf, a horizontally positioned 56-inch TV provided uniform and stable white background light by facing downward. During the experiment, mice were allowed to walk freely in the circular open field for 10 min after a 15 min acclimation period. Their spontaneous behaviors were recorded using the multi-view video capture devices. Images were captured simultaneously at a rate of 30 frames per second using a PCI-E USB-3.0 data acquisition card and the pyrealsense2 Python camera interface package. The cameras and TV were connected to a high-performance computer (i7-9700K, 16 G RAM) equipped with a 1-terabyte SSD and 12-terabyte HDD, which served as a platform for the software and hardware required for image acquisition. Python and OpenCV programs facilitated the capture and storage of the videos of the mice, with the frame rate set to 30 fps and the frame size configured to 640 × 480 pixels. The apparatus was thoroughly cleaned with 25% ethanol after test of each mouse to reduce any potential residual olfactory or behavioral cues left by the previous mouse.

Finally, the movement fractions, which represent the proportion of time spent in each spontaneous behavior clusters, were analyzed and kinematics features were calculated automatically using a three-dimensional behavior decomposition framework. The manual annotation of each behavioral clusters was primarily based on the methodology described in a previous study [34]. Specifically, walking was defined as locomoting with relatively low speed, rearing was defined as standing on its hind legs with the back straight, hunching was defined as standing on its hind legs while the back is bent, and climbing was defined as standing on its hind legs with the back straight and front limbs supporting on the wall. For kinematics analysis, 39 kinematic parameters were assessed through machine learning, including: the speed (horizontal velocity) and movement energy (velocity in three-dimensional space) of 16 labeled body points, speed of the center point of body, body length (distance between nose and root of tail), body height (distance between back and the floor), body angle (the included angle of back-neck and back-tail root), freezing index (time ratio for speed below 15 mm/s for more than 2 s), flight index (time ratio for speed above 400 mm/s for over 0.1 s) and time ratio in center [34].

Image and data analysis

The sample size was determined based on previous similar studies [12, 34]. The data were analyzed using Adobe Photoshop 2023, Adobe Illustrator 2023, Anymaze software, IBM SPSS Statistics 26, and GraphPad Prism 8.0.2. Total distance, maximum speed and time spent in the center in the open field test were analyzed using Anymaze software. The time points of falling in the rotarod test were manually confirmed by an experienced experimenter blind to the experiment groups, and the falling speeds were automatically recorded by the rotarod apparatus. Clustergrams were generated through hierarchical clustering utilizing Ward’s method. The numbers of DA neurons from the brain slices at −3.40 and −3.52 mm in bregma stained with immunofluorescence were manually counted by a blinded experimenter using Adobe Photoshop. At least 3 slices per brain region from each mouse was collected. Since the brain regions are symmetrical, cell counts were recorded separately for each side, and the cell number for each mouse in a given brain region represents the mean of six data points, and the relative neuron numbers of each mouse were calculated as dividing the average number of each mouse by the mean of the control group. To quantify the absolute size of behavioral lateralization, a bias index (BI = √(|VL2-VR2|/(VL*VR)), where VL represents the kinematic parameter of the left side and VR represents the kinematic parameter of the right side) was introduced in the study. Box-plots were created using GraphPad Prism 8.0.2 in Tukey’s style where the center line represents the median, the box limits indicate the upper and lower quartiles, and the whiskers extend to the maximum and minimum data, excluding outliers (defined as data points 1.5 times the interquartile range below the first quartile or above the third quartile). Data are represented as mean ± SEM in the probability distribution function curves and kinematics comparisons. Outliers were identified and excluded using Tukey’s test, then marked with cross symbols (×) in brighter colors on the box plots. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assessed normality. Correlations were determined using Pearson test for normally distributed data. For non-normally distributed data, rank transformation was used to convert the data into a normal distribution. Group differences were analyzed using unpaired two-tailed t-test, paired two-tailed t-test and Mann Whitney U test. Differences were assumed to be extremely significant (***) if the probability (p) value was <0.001, very significant (**) if p < 0.01, significant (*) if p < 0.05, and not significant (N.S.) if p ≥ 0.05.

Results

Distinct spontaneous behaviors in the MPTP mouse model

To explore the behavioral traits of DA neurons in the SNc, we first employed the open field and rotarod tests in the subacute MPTP mouse model (Fig. S1). The MPTP group showed reduced performance in the rotarod test and increased activity in the open field, without significant variation in central time (Fig. S1B, C). While rearing behavior differed in total time and frequency, the duration remained unchanged (Fig. S1D), reflecting previously reported inconsistencies.

Further analysis was conducted one-week post-injection using multi-view cameras and machine learning to categorize behaviors into 40 clusters (Fig. 1A–C). Movement fractions, which represent the proportion of time spent in each behavior clusters [34], were compared, revealing that most MPTP mice (5/9) formed distinct clusters, differentiating them from controls based on behavior (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1. MPTP mouse model showed significant differences in spontaneous behavior compared with the control.

A Timeline of 3D spontaneous behavior analysis performed with mice in the MPTP and the PBS groups. B Schematic representation of the apparatus and the 3D spontaneous behavior analysis pipeline. Upper left: The apparatus of 3D spontaneous behavior analysis. Lower: Labeling and annotation of 16 key body points of mouse. Upper right: Reconstruction of 3D skeleton. C Low-dimensional spatial clustering graph of 40 behavior clusters identified through unsupervised learning. D Clustergram displaying 40 spontaneous behavior clusters from mice in the MPTP and the PBS group (M, MPTP group; P, PBS or control group). 5 out of 9 mice in the MPTP group were clustered together (in the red branches) based on behaviors. E–G Mice in the MPTP group showed notable decline in rearing (cluster 13), walking (cluster 21), and hunching (cluster 34). Comparison between MPTP and PBS group in the movement fractions (left), and representative skeleton diagram (right) of rearing (E), walking (F), hunching (G). H, I Mice in the MPTP group showed a marked decrease in the frequency (H) but not duration (I) in rearing. J, K Mice in the MPTP group showed marked decrease in the frequency (J) but not duration (K) in hunching. The data followed normal distribution after excluding outliers using Tukey’s test, with one data point removed as an outlier and marked with cross symbols (×) in bright red in E, I, and K. Statistics were calculated using the two-tailed t-test (E–K). n = 8–9. Differences were assumed to be extremely significant (***) if the probability (p) value was <0.001, very significant (**) if p < 0.01, significant (*) if p < 0.05, and not significant (N.S.) if p ≥ 0.05.

Three behaviors—rearing (cluster 13), walking (cluster 21), and hunching (cluster 34)—showed notably reduced movement fractions in the MPTP group (Fig. 1E–G). And the frequencies, but not the duration, of rearing and hunching were significantly lower in the MPTP group (Fig. 1H–K).

Correlation between rearing, hunching, and DA neuron count in SNc

One-week post-behavioral analysis, immunofluorescence showed a significant loss of TH+ neurons in the SNc, but not in the VTA, consistent with PD pathology (Fig. 2A–D).

Fig. 2. The decreases in the rearing and hunching behavior were correlated with the loss of DA neurons in the SNc.

A, B Comparisons of the relative numbers of TH+ neurons in SNc (A) and VTA (B) between the MPTP and the PBS group. C, D Representative images of immunofluorescence for TH+ neurons in the MPTP group (C) and the PBS group (D) revealed a significant loss of DA neurons in SNc but not in VTA (Green, TH; Blue, DAPI). E Correlation analyses between movement fractions of behaviors showing notable differences and the relative numbers of TH+ neurons in SNc. Left: rearing; Middle: walking; Right: hunching. F Correlation analyses between the frequencies of behaviors with notable differences and the relative numbers of TH+ neurons in SNc. Left: rearing; Right: hunching. The data followed a normal distribution after excluding outliers using Tukey’s test, with one data point removed as outlier and marked with cross symbol (×) in bright blue in A. Statistics were calculated using the two-tailed t-test (A, B) and Pearson’s correlation analysis (E, F). n = 8–9. Differences were assumed to be extremely significant (***) if the probability (p) value was <0.001, very significant (**) if p < 0.01, significant (*) if p < 0.05, and not significant (N.S.) if p ≥ 0.05.

Given the significant loss of TH+ neurons in the SNc of the MPTP group, we explored the correlation between behavioral changes and neuron count. Our analysis showed strong correlations between the number of TH+ neurons in the SNc and the movement fractions and frequencies of rearing and hunching behaviors, but not walking (Fig. 2E, F).

Although there could be slight damage to TH+ neurons in the VTA after MPTP injection [35, 36], no significant correlation was found between behavior movement fractions and TH+ neuron counts in the VTA (Fig. S2A). Taken together, there are significant correlations between the number of DA neurons in SNc and the rearing or hunching behavior.

MPTP mouse model showed a significant increase in kinematics

Machine learning analysis was utilized to track body points, revealing that MPTP mice exhibited significantly higher kinematic parameters compared to PBS controls, reflecting the hyperactivity noted in spontaneous behavior (Fig. 3A). The probability distribution functions (PDF) of central body speed confirmed this elevation (Fig. 3B). A cluster analysis grouped most MPTP mice (5/9) based on their kinematic profiles, highlighting distinct hyperactive behavior in these PD models (Fig. 3C). Specifically, increased speed of the four claws and greater frame-by-frame central body displacement were observed (Fig. 3D–G, Fig. S2C), while body length remained unchanged (Fig. S2D). Despite no alteration in central area occupancy, which is indicative of anxiety (Fig. S2B), MPTP mice exhibited an increased body angle, potentially linked to reduced rearing and hunching (Fig. S2E).

Fig. 3. MPTP mouse model showed a significant increase in kinematic parameters and alterations in behavioral lateralization.

A Comparisons of 39 kinematic parameters between mice in the MPTP group and the PBS group revealed significant hyperactivity in mice treated with MPTP. B Comparison of the probability density function curve for center speed between the MPTP and the PBS group. C Clustergram of 39 kinematic parameters from the mice in the MPTP and the PBS group. 5 out of 9 mice in the MPTP group were clustered together (in the red branches) based on kinematics. D–G Comparisons of the speed of four claws between the mice in the MPTP and the PBS group: left front claw (D); left hind claw (E); right front claw (F); and right hind claw (G). H Comparisons of movement energy between left and right hind claws in the MPTP and the PBS group respectively. I Comparisons of the bias index (BI=√(|VL2-VR2|/(VL*VR)), where VL represents the movement energy of the left side and VR represents the movement energy of the right side) of hind claws between the MPTP and the PBS group. J, K Representative skeleton motion heat maps for the MPTP group (J) and the PBS group (K), showing a notable right lateralization in the hind claws of the MPTP group. The data followed a normal distribution and statistics were calculated using an unpaired two-tailed t-test (B, D–G, I) and paired t-test (H). Data are represented as mean ± SEM (A, B). n = 8–9. Differences were assumed to be extremely significant (***) if the probability (p) value was <0.001, very significant (**) if p < 0.01, significant (*) if p < 0.05, and not significant (N.S.) if p ≥ 0.05.

Altered behavioral lateralization in MPTP mouse model

Recognizing that PD patients often exhibit motor asymmetry [37], we investigated similar symptoms in the MPTP mouse model. A paired t-test revealed significantly higher movement energy in the right hind claw compared to the left in MPTP mice, a lateralization absents in PBS controls and other kinematics (Fig. 3H, Fig. S2F–H). To quantify the lateralization, we calculated a bias index (BI=√(|VL²-VR²|/(VL*VR))) for limb and claw movements, where VL represents the movement energy of the left side, VR represents the movement energy of the right side. Significant differences were observed only in BI of the hind claw between the MPTP and PBS groups, indicating an alteration in behavioral lateralization after MPTP treatment. (Fig. 3I, Fig. S1I–K). The skeletal motion heat map confirmed this consistent right-sided lateralization (Fig. 3J, K). Thus, MPTP mouse model showed alterations in behavioral lateralization compared to the control.

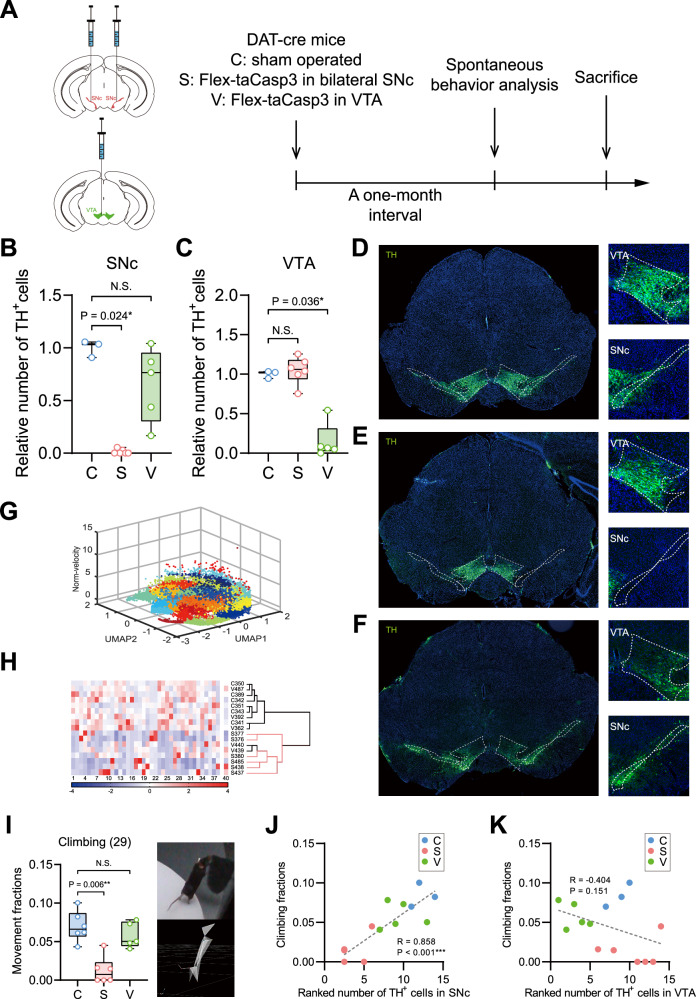

Ablation of TH+ neurons in SNc but not VTA markedly affected behaviors related to rearing

Previous studies found that MPTP intraperitoneal injection might affect peripheral transmitter systems contributing to behavioral changes [38]. To exclude the possibility of non-specific neuronal loss in brain regions, we induced targeted ablation using the DAT-Cre mouse strain and AAV2-Flex-taCasp3-TEVP injections in the SNc or VTA.

Immunofluorescence confirmed a marked reduction of TH+ neurons in the SNc of mice in SNc ablation group and in the VTA of mice in VTA ablation group, validating the specific targeting ablation (Fig. 4A–F). Machine learning identified 40 behavior clusters, showing that SNc ablation group mice exhibited distinct behavior patterns compared to controls (Fig. 4G, H), with significant decreases in climbing behavior (cluster 29), but not in the VTA ablation group (Fig. 4I). This behavioral change correlated significantly with TH+ neuron counts in the SNc, highlighting its specific impact on climbing, similar to rearing, while no such correlation was found in the VTA (Fig. 4J, K).

Fig. 4. Ablation of TH+ neurons in SNc showed a similar behavioral change in spontaneous behavior with the MPTP mouse model.

A Right: Timeline of 3D spontaneous behavior analysis performed with mice in the following groups: C (control, sham operated), S (SNc, specific ablation of TH+ neurons in bilateral SNc), and V (VTA, specific ablation of TH+ neurons in VTA). Left up: schematic of AAV stereotactic injection in bilateral SNc. Left down: schematic of AAV stereotactic injection in VTA. B, C Comparisons of the relative numbers of TH+ neurons in SNc (B) and VTA (C) between the control, SNc ablation, and VTA ablation group. D–F Representative images of immunofluorescence for TH+ neurons in the control (D), SNc ablation (E), and VTA ablation (F) group revealed a notable loss of DA neurons in SNc of the SNc ablation group and VTA of the VTA ablation group (Green, TH; Blue, DAPI). G Low-dimensional spatial clustering graph of 40 behavior clusters identified through unsupervised learning. H Clustergram of 40 spontaneous behavior clusters from mice in the control, SNc ablation, and VTA ablation group. All mice in the SNc ablation group (in the red branches) were separated apart from the control based on behaviors. I Mice in the SNc ablation group but not the VTA ablation group showed notable decline in climbing (cluster 29). Left: comparisons between control, SNc ablation, and VTA ablation group in the movement fractions of climbing behavior, n = 5–6. Right: representative skeleton diagram of climbing behavior. The data followed normal distribution except that in the SNc ablation group. J, K Correlation analyses between the movement fractions of climbing behavior and the ranked numbers of TH+ neurons in SNc (J) and VTA (K). The data followed a normal distribution except that in the SNc ablation group (B) and statistics were calculated using Mann-Whitney U test (B) and two-tailed t-test (B, C), n = 3–6. The data followed normal distribution and statistics were calculated using two-tailed t-test (I), n = 5–6. The R and p values for the Pearson’s correlation between neurons and behaviors are noted on the plots (J, K), n = 3–6. Differences were assumed to be extremely significant (***) if the probability (p) value was <0.001, very significant (**) if p < 0.01, significant (*) if p < 0.05, and not significant (N.S.) if p ≥ 0.05.

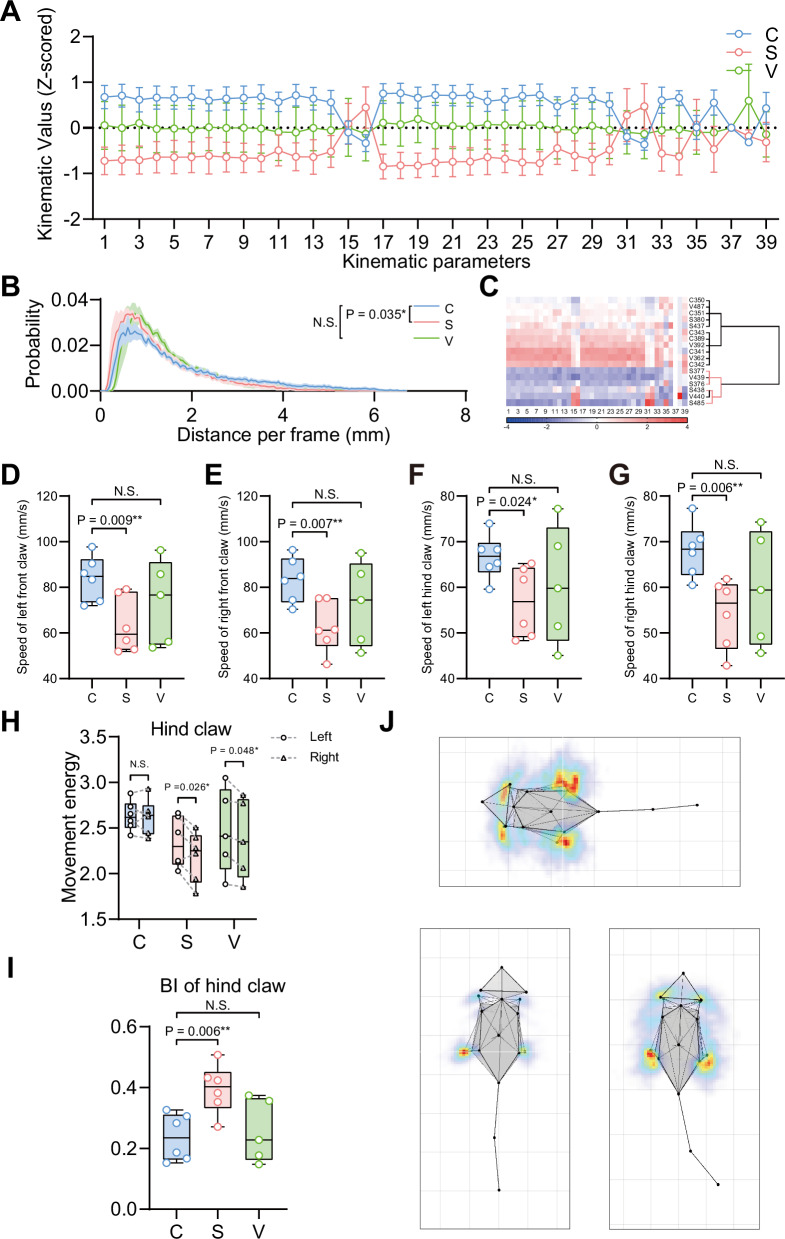

Ablation of TH+ neurons in SNc markedly affected the kinematic function and behavioral lateralization

To determine how neuron loss in specific brain regions affects kinematic functions, we tracked 16 body points and analyzed 39 kinematic parameters. Significant reductions in most kinematic parameters were observed in the SNc ablation group compared to controls, with no significant changes in the VTA ablation group (Fig. 5A). PDF curves of central body speed highlighted these differences (Fig. 5B). Cluster analysis showed distinct grouping of most SNc ablation group mice (4/6) compared to controls (Fig. 5C). Specifically, both the speed of the four claws and the central body point’s displacement per frame were lower in the SNc ablation group (Fig. 5D–G, Fig. S3B), aligning with DA neuron function literature.

Fig. 5. Ablation of TH+ neurons in SNc but not VTA showed measurable kinematic disorders and behavioral alterations.

A Comparisons of 39 kinematic parameters between mice in the C (control, sham operated), S (SNc, specific ablation of TH+ neurons in bilateral SNc), and V (VTA, specific ablation of TH+ neurons in VTA) group showed significant motor disorders in the SNc ablation but not VTA ablation group. B Comparison of the probability density function curve for center speed between the control, SNc ablation, and VTA ablation group. C Clustergram of 39 kinematic parameters from the mice in the control, SNc ablation, and VTA ablation group. 4 out of 6 mice in the SNc ablation group (in the red branches) were separated apart from the control based on kinematics. D–G Comparisons of the speed of each claw between the mice in the control, SNc ablation, and VTA ablation group: left front claw (D); left hind claw (E); right front claw (F); and right hind claw (G). H Comparisons of the movement energy between left and right hind claw in the control, SNc ablation, and VTA ablation group respectively. I Comparisons of the bias index (BI=√(|VL2-VR2|/(VL*VR)), where VL represents the movement energy of the left side and VR represents the movement energy of the right side) of hind claws between the control, SNc ablation, and VTA ablation group. J Representative skeleton motion heat maps of the control (up), SNc ablation (bottom right) and VTA ablation (bottom left) group, showing notable alterations in behavioral lateralization in the SNc ablation group. The data followed normal distribution and statistics were calculated using unpaired two-tailed t-test (B, D–G, I) and paired t-test (H). Data are represented as mean ± SEM (A, B). n = 5–6. Differences were assumed to be extremely significant (***) if the probability (p) value was <0.001, very significant (**) if p < 0.01, significant (*) if p < 0.05, and not significant (N.S.) if p ≥ 0.05.

While no notable differences were detected in time spent in the central area or body angle (Fig. S3A, D), the SNc ablation group displayed shorter body length, possibly due to increased turning movements indicating behavioral lateralization (Fig. S3C).

Paired t-tests and BI measurements revealed consistent hind claw lateralization in both the SNc and VTA ablation groups (Fig. 5H, Fig. S3E–G). Additionally, the BI for front limb, front claw, and hind claw was significantly higher in the SNc ablation group versus controls, indicating altered lateralization due to SNc DA neuron loss (Fig. 5I, Fig. S3H–J). Conversely, lateralization was unchanged in the VTA ablation group compared to controls (Fig. S3J).

Discussion

In this study, we utilized a 3D spontaneous behavior analysis system enhanced by machine learning to investigate motor and subtle behavioral changes in a subacute MPTP mouse model of Parkinson’s disease (PD) and in mice with AAV-induced dopamine (DA) neuron loss. Our advanced approach allowed us to capture detailed and nuanced behavioral features that traditional 2D methods might miss, offering richer insights into the impact of DA neuron depletion. This method proves especially useful considering the complexity and multifaceted roles DA neurons play in both motor function and behavior.

Our primary discovery was the significant correlation between reductions in rearing and hunching behaviors and the loss of DA neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc). Rearing, commonly associated with exploratory activity and attentional processes [39, 40], may serve as reliable and early indicators of SNc neuronal damage. Rearing behavior has shown relationship with dopamine or DA terminals in the striatum, supporting the correlation with SNc we found [39, 41]. Hunching was identified as a stereotyped behavior in Shank3B knockout mouse, an established animal model for autism, highlighting its potential translational relevance in behavioral studies of neurological disorders in previous study [34]. However, the significance of hunching behavior in the mice with neural loss in the SNc, and its relationship with the PD mouse model, still require further analysis. Such behavioral hallmarks are invaluable, as they not only contribute to understanding neuronal regulation, but also enhance the translational relevance of PD mouse models. Particularly in PD, where early diagnosis is challenging, identifying specific behaviors linked with DA neuron viability represents a critical advancement.

DA neuron regulation is inherently complex, frequently varying across neuropsychiatric disorders like PD. This complexity poses substantial challenges for traditional behavioral paradigms, which often suffer from subjectivity and high labor demands. Despite digital advancements that promise enhanced data accuracy, limitations persist, especially regarding the ability to capture fine behavioral details. The 3D behavior analysis system we employed overcame these limitations by providing an intricate look into the mice’s spontaneous behaviors. It enabled us to document behavioral declines not just in rearing but also in hunching and climbing, behaviors that have been less consistently observed with 2D methodologies.

Climbing is a kind of behavior similar to rearing which typically occurs at the edge of the open field, and some studies also identified climbing behavior as rearing [42, 43]. Interestingly, while climbing was correlated with the neuronal lesions and significantly impaired in mice with AAV-induced DA neuron loss, it was not as prominent in the MPTP model. This discrepancy might be attributed to differences in damage severity between the two models. The AAV-induced model, which directly targets DA neurons leading to severe depletion, likely represents a more acute model of neuronal damage compared to the subacute MPTP model, where compensatory mechanisms might mitigate some aspects of motor dysfunction. Significant motor dysfunction induced by severe neuron damage might be the reason for the decrease in climbing but not rearing.

Moreover, our study also uncovered alterations in behavioral lateralization in both MPTP and AAV-induced models, highlighting SNc damage’s role in motor asymmetry. Behavioral asymmetries were considered to be related to neuroanatomical left-right differences in motor control systems of the brain, such as the nigrostriatal dopaminergic system, in humans and rodents [44]. Additionally, asymmetries in mesoaccumbens dopamine showed a strong relationship with both the direction and the intensity of behavioral lateralization, as indicated by paw preference in mice [45]. Such findings point toward the broader implications of DA neuron loss beyond mere motor impairment, encompassing also neural circuit imbalances that could hint at hemispheric differences in neurological impairment. However, intraperitoneal injection of MPTP is generally considered as a non-lateralized treatment. It is worth investigating whether the sensitivity of the SNc to MPTP, or the impacts of damage in SNc to the downstream regions, differ between hemispheres. Using mice lacking the dopamine transporter (DAT) as a genetic model of persistent hyperdopaminergia, Morice et al. suggested that alterations in the dopaminergic system are functionally associated to the loss of behavioral asymmetry [46]. We hypothesize that neuronal damage in the SNc could have significant effects on the dopaminergic system, leading to alterations in behavioral lateralization. The different results in behavioral lateralization between MPTP and AAV-induced models could also be attributed to the compensatory mechanism in the DA system. While the cause of asymmetry in PD remains unclear [37, 47, 48], alterations in behavioral lateralization may also serve as a valuable indicator in the animal models. On the other hand, the observed asymmetry might be due to the statistical variability. Self-control experiments could provide a more rigorous and conclusive assessment of the asymmetry resulting from DA neuronal loss.

Despite no overt kinematic deficits were observed in the open field test or the spontaneous behavior analysis, MPTP model showed reduced performance in the rotarod test. It’s possible that compensatory actions within the dopamine system might mask the traditional motor symptoms of PD. Qi et al. reported that although subacute MPTP treatment caused severe dopaminergic neuronal damage and noticeable astrogliosis 21 days after administration, the mice did not show significant impairments in motor and cognitive functions at 1, 7, 14, or 21 days after treatment. Due to compensatory mechanisms mitigating dopaminergic defects, subacute MPTP may only mimic the pre-clinical stage of PD in which patients present significant loss of midbrain dopaminergic neurons but no motor abnormalities [21], which aligns with existing literature pointing to the brain’s remarkable plasticity and ability to compensate for early dopaminergic deficits, at least temporarily [12, 49–51]. Wang et al. also failed to find typical movement defects in subacute MPTP-treated mice, despite serious damage to the dopaminergic neurons and the remarkable decrease in DA content. They proposed that this may be due to the evident increase in norepinephrine content and suggested that norepinephrine deficiency might be necessary for motor impairment [20]. Meanwhile, the subacute MPTP model showed overt hyperactivity, which was consistent with several previous studies. Santoro et al. characterized three different MPTP mouse models of PD (acute, subacute and chronic) neurochemically, histologically, and behaviorally, and also found generalized hyperactivity in the subacute model [18]. Another research suggested that MPTP-induced injury in A11 diencephalospinal pathway, which is thought to be involved in restless legs syndrome and can be affected by MPTP in non-human primates, might be the explanation for hyperactivity [19]. Several studies have also identified genes associated with hyperactivity. Filali and Lalonde observed hyperactivity and reduced rearing in the open field test of Pitx3/ak mutants (deletion of paired-like homeodomain 3), which are characterized by basal ganglia pathology resembling that of PD. However, they didn’t find such behavioral changes in wild-type mice treated with MPTP, probably because of the acute regimen they used [52]. Torres et al. found that mGlu8 KO mice (deficient in metabotropic glutamate receptor 8) were protected from subchronic MPTP-induced hyperactivity [53]. Additionally, as reported by Su et al., subacute MPTP-induced hyperactivity was not detected in mice with silenced RESP18 (regulated endocrine-specific protein 18) expression [54], providing possible explanations for the effects of MPTP. Since the variations in motor ability were found in the MPTP model, rearing and similar behaviors (such as hunching and climbing) have the potential to serve as early and reliable behavioral indicators of SNc DA neuron integrity, making them excellent candidates for more sensitive measures in PD research.

In summary, our findings underscore the importance of rearing behavior as a critical marker of DA neuron health. Its reduction correlates strongly with DA neuron loss in the SNc, offering a valuable translational marker for monitoring PD progression. Future research should concentrate on establishing real-time correlations between DA neuron activity and rearing behavior, considering the complex interactions within the broader dopaminergic network. Such work is essential to refine our understanding of the symptoms and progression of PD and to improve the design and application of therapeutic interventions. Additionally, further research should explore how these behavioral changes relate to specific neural circuit alterations, broadening potential targets for therapeutic strategies.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the insightful feedback from Ke Chen, Yaning Han, and Kang Huang as well as the technical assistance from Shenzhen Bayone BioTech Co., LTD.

Author contributions

XL, PW, and WW designed and directed the study. HZ completed the experiments and data analysis, for which XL, KL provided support and guidance. HZ and KL drew the figures. HZ, XL wrote the manuscript, XL, HZ, PW, WW, and LW revised it. All authors revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by STI2030-Major Projects-2022ZD0211700, the National Natural Science Foundation of China 32371069, 32222036 and 32230042 (LW), Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (JCYJ20210324102201003), Research Fund for International Senior Scientists (T2250710685), Guangdong Province Basic Research Grant (2023B1515040009), Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Brain Connectome and Behavior 2023B1212060055, the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province of China (Grant No. 2021A1515012481) and the Financial Support for Outstanding Talents Training Fund in Shenzhen (LW).

Data availability

Behavior atlas (https://behavioratlas.tech//) was used for 3D spontaneous behavior analysis. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study involved only animal research. All husbandry procedures and experiments conformed to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees guidelines at Shenzhen Institute of Advanced Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IACUC ref: YSB-20211014-A0158).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Hao Zhong, Kangrong Lu.

Contributor Information

Wanshan Wang, Email: wws@smu.edu.cn.

Pengfei Wei, Email: pf.wei@siat.ac.cn.

Xuemei Liu, Email: xm.liu@siat.ac.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41398-025-03312-8.

References

- 1.Bromberg-Martin ES, Matsumoto M, Hikosaka O. Dopamine in motivational control: rewarding, aversive, and alerting. Neuron. 2010;68:815–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bjorklund A, Dunnett SB. Dopamine neuron systems in the brain: an update. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iversen SD, Iversen LL. Dopamine: 50 years in perspective. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:188–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elam HB, Perez SM, Donegan JJ, Lodge DJ. Orexin receptor antagonists reverse aberrant dopamine neuron activity and related behaviors in a rodent model of stress-induced psychosis. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11:114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schultz W. Predictive reward signal of dopamine neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:1–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watabe-Uchida M, Zhu L, Ogawa SK, Vamanrao A, Uchida N. Whole-brain mapping of direct inputs to midbrain dopamine neurons. Neuron. 2012;74:858–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tye KM, Mirzabekov JJ, Warden MR, Ferenczi EA, Tsai HC, Finkelstein J, et al. Dopamine neurons modulate neural encoding and expression of depression-related behaviour. Nature. 2013;493:537–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lammel S, Lim BK, Ran C, Huang KW, Betley MJ, Tye KM, et al. Input-specific control of reward and aversion in the ventral tegmental area. Nature. 2012;491:212–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaudhury D, Walsh JJ, Friedman AK, Juarez B, Ku SM, Koo JW, et al. Rapid regulation of depressionrelated behaviours by control of midbrain dopamine neurons. Nature. 2013;493:532–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ben-Shlomo Y, Darweesh S, Llibre-Guerra J, Marras C, San Luciano M, Tanner C. The epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 2024;403:283–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schapira AH, Jenner P. Etiology and pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2011;26:1049–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leite Silva ABR, Goncalves de Oliveira RW, Diogenes GP, de Castro Aguiar MF, Sallem CC, Lima MPP, et al. Premotor, nonmotor and motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: a new clinical state of the art. Ageing Res Rev. 2023;84:101834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ilango A, Kesner AJ, Keller KL, Stuber GD, Bonci A, Ikemoto S. Similar roles of substantia nigra and ventral tegmental dopamine neurons in reward and aversion. J Neurosci. 2014;34:817–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engelhard B, Finkelstein J, Cox J, Fleming W, Jang HJ, Ornelas S, et al. Specialized coding of sensory, motor and cognitive variables in VTA dopamine neurons. Nature. 2019;570:509–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langston JW, Ballard P, Tetrud JW, Irwin I. Chronic Parkinsonism in humans due to a product of meperidine-analog synthesis. Science. 1983;219:979–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dauer W, Przedborski S. Parkinson’s disease: mechanisms and models. Neuron. 2003;39:889–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson-Lewis V, Przedborski S. Protocol for the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:141–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santoro M, Fadda P, Klephan KJ, Hull C, Teismann P, Platt B, et al. Neurochemical, histological, and behavioral profiling of the acute, sub-acute, and chronic MPTP mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem. 2023;164:121–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang H, Liang X, Wang X, Luo D, Jia J, Wang X. Electro-acupuncture stimulation improves spontaneous locomotor hyperactivity in MPTP intoxicated mice. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e64403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang QS, Heng Y, Mou Z, Huang JY, Yuan YH, Chen NH. Reassessment of subacute MPTP-treated mice as animal model of Parkinson’s disease. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2017;38:1317–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qi Y, Zhang Z, Li Y, Zhao G, Huang J, Zhang Y, et al. Whether the subacute MPTP-treated mouse is as suitable as a classic model of Parkinsonism. Neuromolecular Med. 2023;25:360–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lubejko ST, Livrizzi G, Buczynski SA, Patel J, Yung JC, Yaksh TL, et al. Inputs to the locus coeruleus from the periaqueductal gray and rostroventral medulla shape opioid-mediated descending pain modulation. Sci Adv. 2024;10:eadj9581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu X, Zhao G, Wang D, Wang S, Li R, Li A, et al. A specific circuit in the midbrain detects stress and induces restorative sleep. Science. 2022;377:63–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lauretti E, Di Meco A, Merali S, Pratico D. Chronic behavioral stress exaggerates motor deficit and neuroinflammation in the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6:e733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim W, Tripathi M, Kim C, Vardhineni S, Cha Y, Kandi SK, et al. An optimized Nurr1 agonist provides disease-modifying effects in Parkinson’s disease models. Nat Commun. 2023;14:4283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hinkle JT, Patel J, Panicker N, Karuppagounder SS, Biswas D, Belingon B, et al. STING mediates neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation in nigrostriatal alpha-synucleinopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2022;119:e2118819119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y, Roy DS, Zhu Y, Chen Y, Aida T, Hou Y, et al. Targeting thalamic circuits rescues motor and mood deficits in PD mice. Nature. 2022;607:321–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sampson TR, Debelius JW, Thron T, Janssen S, Shastri GG, Ilhan ZE, et al. Gut microbiota regulate motor deficits and neuroinflammation in a model of Parkinson’s disease. Cell. 2016;167:1469–80.e1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu X, Feng X, Huang H, Huang K, Xu Y, Ye S, et al. Male and female mice display consistent lifelong ability to address potential life-threatening cues using different post-threat coping strategies. BMC Biol. 2022;20:281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han Y, Huang K, Chen K, Pan H, Ju F, Long Y, et al. MouseVenue3D: a markerless three-dimension behavioral tracking system for matching two-photon brain imaging in free-moving mice. Neurosci Bull. 2022;38:303–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bidgood R, Zubelzu M, Ruiz-Ortega JA, Morera-Herreras T. Automated procedure to detect subtle motor alterations in the balance beam test in a mouse model of early Parkinson’s disease. Sci Rep. 2024;14:862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frohlich H, Claes K, De Wolf C, Van Damme X, Michel A. A machine learning approach to automated gait analysis for the noldus catwalk system. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2018;65:1133–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang Z, Zhou F, Zhao A, Li X, Li L, Tao D, et al. Multi-view mouse social behaviour recognition with deep graphic model. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2021;30:5490–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang K, Han Y, Chen K, Pan H, Zhao G, Yi W, et al. A hierarchical 3D-motion learning framework for animal spontaneous behavior mapping. Nat Commun. 2021;12:2784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schildknecht S, Di Monte DA, Pape R, Tieu K, Leist M. Tipping points and endogenous determinants of nigrostriatal degeneration by MPTP. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2017;38:541–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roostalu U, Salinas CBG, Thorbek DD, Skytte JL, Fabricius K, Barkholt P, et al. Quantitative whole-brain 3D imaging of tyrosine hydroxylase-labeled neuron architecture in the mouse MPTP model of Parkinson’s disease. Dis Model Mech. 2019;12:dmm042200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Djaldetti R, Ziv I, Melamed E. The mystery of motor asymmetry in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:796–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sedelis M, Schwarting RK, Huston JP. Behavioral phenotyping of the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Behav Brain Res. 2001;125:109–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aspide R, Fresiello A, de Filippis G, Gironi Carnevale UA, Sadile AG. Non-selective attention in a rat model of hyperactivity and attention deficit: subchronic methylphenydate and nitric oxide synthesis inhibitor treatment. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:59–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aspide R, Gironi Carnevale UA, Sergeant JA, Sadile AG. Non-selective attention and nitric oxide in putative animal models of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Behav Brain Res. 1998;95:123–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schwarting RK, Sedelis M, Hofele K, Auburger GW, Huston JP. Strain-dependent recovery of open-field behavior and striatal dopamine deficiency in the mouse MPTP model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurotox Res. 1999;1:41–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu N, Han Y, Ding H, Huang K, Wei P, Wang L. Objective and comprehensive re-evaluation of anxietylike behaviors in mice using the behavior atlas. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2021;559:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheets AL, Lai PL, Fisher LC, Basso DM. Quantitative evaluation of 3D mouse behaviors and motor function in the open-field after spinal cord injury using markerless motion tracking. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e74536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manns M, Basbasse YE, Freund N, Ocklenburg S. Paw preferences in mice and rats: meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;127:593–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cabib S, D’Amato FR, Neveu PJ, Deleplanque B, Le Moal M, Puglisi-Allegra S. Paw preference and brain dopamine asymmetries. Neuroscience. 1995;64:427–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morice E, Denis C, Macario A, Giros B, Nosten-Bertrand M. Constitutive hyperdopaminergia is functionally associated with reduced behavioral lateralization. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:575–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mirelman A, Ben Or Frank M, Melamed M, Granovsky L, Nieuwboer A, Rochester L, et al. Detecting sensitive mobility features for Parkinson’s disease stages via machine learning. Mov Disord. 2021;36:2144–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Constantin IM, Voruz P, Peron JA. Moderating effects of uric acid and sex on cognition and psychiatric symptoms in asymmetric Parkinson’s disease. Biol Sex Differ. 2023;14:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blesa J, Foffani G, Dehay B, Bezard E, Obeso JA. Motor and non-motor circuit disturbances in early Parkinson disease: which happens first? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2022;23:115–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maetzler W, Hausdorff JM. Motor signs in the prodromal phase of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2012;27:627–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taguchi T, Ikuno M, Yamakado H, Takahashi R. Animal model for prodromal Parkinson’s disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Filali M, Lalonde R. Neurobehavioral anomalies in the Pitx3/ak murine model of Parkinson’s disease and MPTP. Behav Genet. 2016;46:228–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Torres ERS, Akinyeke T, Stagaman K, Duvoisin RM, Meshul CK, Sharpton TJ, et al. Effects of sub-chronic MPTP exposure on behavioral and cognitive performance and the microbiome of wild-type and mglu8 knockout female and male mice. Front Behav Neurosci. 2018;12:140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Su J, Wang H, Yang Y, Wang J, Li H, Huang D, et al. RESP18 deficiency has protective effects in dopaminergic neurons in an MPTP mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurochem Int. 2018;118:195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Behavior atlas (https://behavioratlas.tech//) was used for 3D spontaneous behavior analysis. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.