Abstract

Mammalian preimplantation embryo development is a complex sequence of events. This period of development is sensitive to oxygen (O2) levels that can affect various cellular processes. We compared the influence of O2 tension by culturing embryos either in normoxic (20% O2) or physiological hypoxic (6% O2) conditions, or sequential low O2 concentration starting with 6% O2 until 16-cell stage and then switching to ultrahypoxic conditions (2% O2). Due to ethical concerns, we used bovine as an animal model with a good similarity of embryogenesis to human. We found that the cleavage rate was not affected by O2 levels but there was a clear difference in blastocyst formation rate. In hypoxia, 36% of embryos reached blastocyst stage while in normoxia only 13%. In ultrahypoxia conditions only 4.6% of embryos developed up to blastocyst stage. Transcriptomic profiles showed that normoxic conditions slowed down oocyte transcript degradation which is a prerequisite for reprogramming of the embryonic cell lineages. There were also clear differences in the expression of key metabolic enzymes between hypoxic and normoxic conditions at the blastocyst stage. Both hypoxic and ultrahypoxic conditions seemed to induce appropriate energy production by upregulating genes involved in glycolysis and lipid metabolism typical to in vivo embryos. In contrast, normoxic conditions failed to upregulate glycolysis genes and only depended on oxidative phosphorylation metabolism. We conclude that constant hypoxia culture of in vitro embryos provided the highest blastocyst formation rate and appropriate energy metabolism. Normoxia altered the energy metabolism and decreased the blastocyst formation rate. Even though ultrahypoxia at blastocyst stage resulted in the lowest blastocyst formation, the transcriptional profile of surviving embryos was normal.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-95990-z.

Subject terms: Embryology, Gene expression, Genetics, Sequencing, RNA sequencing

Introduction

Early preimplantation embryo development is a highly coordinated and complex process with a cascade of precisely timed events. Different from the rather stable in vivo conditions, in vitro embryos are exposed to distinct environmental factors such as culture medium composition, pH, temperature, and oxygen (O2) levels. Culture medium and its composition has been shown to affect embryonic metabolism in mouse, rabbit and bovine1–4, and it also has an impact on the success rate of human in vitro fertilization (IVF) and on the birthweights of infants born after IVF5.

The importance of O2 concentration during in vitro culture (IVC) of embryos was first understood in the first report of successful human embryo culture6 where oxygen tension was maintained at 5%. In several mammalian species, O2 tension in female reproductive tract (oviducts and uterus) ranges generally between 2 and 8%7. Despite this knowledge, 49% of clinical IVF laboratories in Europe and 32% in the USA use atmospheric 20% O2 levels in their embryo cultures8,9. Historically, IVF laboratories used normoxia for embryo culture system, and switching to hypoxia requires specific laboratory equipment and infrastructure, which can be expensive and difficult to implement in practice. Recently, many meta-analyses pointed out that clinical pregnancy rates were clearly higher if embryos were cultured in physiological 5% O2 (32–43%) rather than in atmospheric 20% O2 (30%)10.

The epigenetic, metabolic, and transcriptomic profiles of embryos grown under different O2 levels have been studied in different species. These studies focused on comparing the low monophasic O2 level to the atmospheric O2. In the mouse, for example, atmospheric O2 changes the number of mitochondria and their structure in the blastocyst stage11 as well as the glucose and amino acid metabolism12. In addition, the impact of atmospheric O2 was seen as early as in 2- to 4-cell mouse embryos during the time of embryonic genome activation (EGA) as the inhibition of histone lactylation13.

Interestingly, the level of O2 is estimated to be the lowest inside the uterus (2% O2), motivating the question of whether a further decrease in the level of O2 after day 3 of development might be more beneficial for the blastocyst formation and pregnancy rates14. Similarly to the ‘back to nature’ hypothesis of sequential in vitro culture medium, it was proposed that O2 levels should follow such a trend for a more physiological culture system. In studies with human embryos focusing on such ‘sequential’ low O2 cultures, ultra-low O2 culture conditions were not found to be superior to monophasic low O215–17. These studies focused on blastocyst formation rate and observed no significant difference between low and ultra-low O2 and proposed ultrahypoxia might have an impact after implantation15–17. To study this question, the authors of these studies proposed randomized control studies to see the effect of ultrahypoxia on pregnancy outcomes16,17.

To understand the impact of different O2 levels on the transcriptome, we cultured embryos in either atmospheric 20% O2, hypoxic 6% O2 or in the sequential low O2 where embryos were first cultured at 6% O2 until they reached 16-cell and then moved to 2% O2 until the blastocyst stage. We employed the 5’ end-targeted RNA sequencing method, STRT-N18, which allows us to distinguish between the degrading maternal and the first upregulated embryonic transcripts and compared zygote, 4-, 8-, 16-cell embryos, grown in either normoxic or hypoxic conditions. Blastocyst stage embryos were compared across 3 conditions: normoxia, hypoxia and sequential ultrahypoxia (2% O2).

Considering ethical issues with human embryos, we used bovine IVF embryos as an animal model. The advantages of using bovine model for human development are reviewed in Santos et al.19. In bovine, oogenesis takes several months while oocyte maturation takes 20–24 h, and the size of the matured oocyte is around 120 μm20. These processes are significantly shorter in the mouse. During human EGA, the first active genes are PRD-like homeobox genes21. These genes are absent from mouse22, but present in bovine23, supporting the usefulness of bovine embryos as a model for human development.

Materials and methods

Ovary collection and oocyte extraction

Bovine ovaries were collected in 37 °C prewarmed 0.9% sterile NaCl solution and transported from the local slaughterhouse to the laboratory. The ovaries were washed twice with fresh, warm, sterile 0.9% NaCl solution before continuing with the cumulus oocyte complexes (COCs) aspiration from the 2–8 mm size follicles using vacuum pump (Minitüb GmbH). COCs grade 124 were then cultured in groups of 50 COCs in 500 µl in in vitro maturation (IVM) medium containing 0.8% of bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.5 mM pyruvate, 1 mM of L-glutamine, 0.05 µg/ml of EGF in 4-well Nunc plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific). IVM was performed for 22–24 h at 38.5 °C, 5% CO2.

In vitro fertilization (IVF)

The matured oocytes were fertilized with thawed frozen semen (Holstein breed bull) by co-incubating them in groups of 50 in 500 µl IVF medium supplemented with 0.6% BSA, 0.25 mM pyruvate, 20 µM penicillamine, 10 µM hypotaurine, 1 µM epinephrine and 30 µg/ml heparin. The 4-well Nunc plates were placed at 38.5 °C, 5% CO2 for 19–20 h.

Embryo culture and collection

After IVF, cumulus cells were removed by vortexing, denuded zygotes were transferred to 500 µl of modified Synthetic Oviduct Fluid (SOF) supplemented with 0.8% BSA, 0.25 mM pyruvate, 0.2 mM L-glutamine, BME (Sigma-Aldrich, B6766) and MEM amino acid solutions (Sigma-Aldrich, M7145). In vitro culture (IVC) was performed based on the testing conditions. Two 4-well Nunc plates were placed in the incubator at 20% O2 for 8 days in normoxia condition. For hypoxia, embryos were cultured at 6% O2 the whole 8 days, while for the ultrahypoxia condition embryos were cultured until 16-cell stage at 6% O2 and then placed to 2% O2 until the day 8 of development.

One 4-well control dish per condition, used to calculate cleavage rate and blastocyst formation rate, was left in the incubators for 8 days and only removed at the time of checking the cleavage and blastocyst formation rates (Supplementary Table 2). The rates were calculated based on each well in the control dish using the number of presumptive zygotes per well. The other plates were used to collect embryos for RNA sequencing. Three embryos per developmental stage (zygote (20 h post fertilization (hpf)), 4-cell (48 hpf), 8-cell (72 hpf), 16-cell (96 hpf), and blastocyst (168 hpf)) were collected and placed in the cell lysis buffer as previously described in Boskovic et al., (2023). Briefly, embryos were taken out of the IVC plate and placed in Acid Tyrode’s solution until zona pellucida was dissolved. Then embryos were washed in a drop of IVC medium, followed by washing in two consecutive drops of PBS before placing it in the cell lysis buffer.

Single oocyte/embryo RNA-seq library preparation

Single embryo RNA-seq libraries were prepared using the STRT-N seq protocol18. In brief, cell lysate plate was removed from − 80°C and RNA was immediately denatured for 2 min at 80 °C and placed on ice. Reverse transcription mixture was added containing synthetic ERCC Spike-ins mix. Reverse transcription was performed at 42°C for 1 h followed by 10 cycles of 42 °C and 50 °C each lasting 2 min. cDNA was cleaned up and barcoded primers were added before performing cDNA amplification with 23 PCR cycles. cDNA samples were pooled, cleaned up and fragmented. Samples were then prepared for sequencing by extracting the 5’ end of the cDNA, repairing the ends and ligating the sequencing adapters, before performing the final library amplification.

Processing and analysis of the STRT-N RNA-seq libraries

Preprocessing of the raw RNA-seq data was done on Center for Scientific Computing (CSC) HPC server (Finland) using the pipeline described in https://github.com/gyazgeldi/STRTN, (commit number 5b60c80)18. Raw reads were mapped to bosTau9 genome and annotated with RefSeq ARS-UCD.1.2. Quality control of the data was performed using the quality control output file from the preprocessing pipeline. Samples with low total reads, mapped reads and spike-in reads were removed. The raw count matrix (13,103 genes) was then processed with a fluctuation test to eliminate the genes which do not fluctuate more than the RNA ERCC spike-ins (i.e., only technical variation), eliminating 1,898 genes (Supplementary Table 1). Fluctuated raw count matrix was used for the downstream analysis. The R package, Seurat (v4.4.0) was used to perform unsupervised sample clustering with PCA and UMAP plots. Differential expression analysis was done using the DESeq2 package (v 1.40.2) and RNA ERCC spike-ins were utilized for the data normalization; genes with less than 10 counts per sample were removed and 9,588 genes were left for the downstream analysis. For the gene to be significantly differentially expressed, an FDR of 5% was used, with the adjusted p-value applied to all significance testing. Ggplot2 package (v 3.5.0) was used for the graphical visualization of the results. ClusterProfiler (v 4.8.3), AnnotationDbi (v 1.62.2) and bovine genome database package (org.Bt.eg.db, v 3.17.0) were used for the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)25 and gene ontology (GO) analysis. Nonparametric Scheirer-Ray-Hare Test was used to perform statistical analysis of cleavage and blastocyst formation rate, followed by Dunn test. Statistical significance was considered if p < 0.05.

Results

Blastocyst formation rate lowest in the ultra-low O2 condition

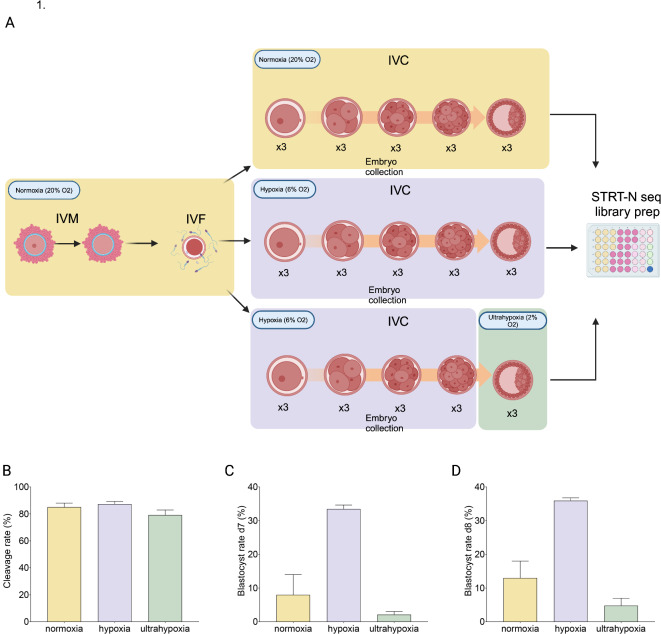

To study the effect of O2 concentration during in vitro culture of embryos, we performed 3 separate experiments. First, we performed IVM, IVF and 8 days of IVC under atmospheric 20% O2, hereinafter referred to as normoxia. In the second condition, 8 days of IVC were done under physiological 6% O2, referred to as hypoxia condition. Finally, to test the hypothesis of sequential low and ultra-low O2 culture, first 3 days of IVC were done under 6% O2 (hypoxia), after which the concentration of O2 in the incubator was lowered to 2%; this condition is called ultrahypoxia. Three embryos per developmental stage (zygote, 4-, 8-, 16-cell and blastocyst) were collected for the preparation of STRT-N RNA sequencing library (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Study design and laboratory parameters. (A) Three different experimental conditions were tested. In normoxia in vitro maturation (IVM), in vitro fertilization (IVF) and in vitro culture (IVC) were performed at 20% O2. Three embryos per developmental stages: zygotes, 4-cell, 8-cell, 16-cell and blastocysts were collected and placed in a 48-well plate containing cell lysis buffer for STRT-N seq. Hypoxia condition had the same experimental design, but O2 concentration used was 6%. Third condition was done by performing IVC until 16-cell stage at hypoxia 6% and then the O2 concentration was lowered to 2% O2 until blastocyst stage. Embryo collection in this experiment was done both during hypoxia stages, and blastocysts for ultrahypoxia were collected and placed in the same STRT-N seq cell lysis plate. (B) Cleavage rate of all embryos at all conditions was calculated 24 h after the zygotes were placed in the IVC. (C) Blastocyst formation rate on day 7 of the embryo culture was calculated including the expanded and hatched blastocysts. (D) Blastocyst formation rate on day 8 of the embryo culture was calculated including the expanded and hatched blastocysts. Blastocyst formation rates were calculated based on the number of presumptive zygotes. Error bars represent +/- SEM. Figure created with BioRender.

In each experiment, a 4-well control dish was used to calculate the cleavage and blastocyst formation rate. The number of presumptive zygotes in normoxia was 100, in hypoxia 164 and 194 in ultrahypoxia. The exact numbers of embryos developed per well in each control dish can be seen in the supplementary table 2A, B, C. Cleavage rate was determined 24 h after the embryos were placed in the culture, and it was 85% in normoxia, 86% in hypoxia and 78.9% in ultrahypoxia experiment (Fig. 1B). We did not observe any significant difference between the cleavage rate across conditions. In concordance with the literature, normoxia condition had a lower blastocyst formation rate both on day 7 and day 8; 8% and 13%, respectively, in comparison to the hypoxia blastocyst formation rate at day 7 and day 8 of 33% and 36%, respectively (Fig. 1C and D). The observed difference was suggestive, but significance suffered from the low number of replicates for normoxia (n = 2) (p = 0.056). Opposite to the recent reports in human and mouse16,17,26, we found the lowest blastocyst formation rate with 2.1% of cleaved embryos reaching the blastocyst stage at day 7 and 4.6% at day 8 in ultrahypoxia condition (Fig. 1C and D). In comparison to hypoxia, we found that blastocyst formation rate in ultrahypoxia was statistically significant (p < 0.01).

Expression pattern of samples coincide with the development stages

The STRT-N RNA-seq is a 5’ end targeted RNA sequencing method, optimized for embryological studies. STRT-N allows distinction between degrading maternal and the newly transcribed embryonic transcripts. After sequencing, the raw data was preprocessed, and we performed quality control of the samples (Supplementary Fig. 1). Due to the low number of total reads, mapped reads and spike-in reads, we removed from further analysis 3 samples: 13 (16-cell hypoxia), 26 (zygote ultrahypoxia) and 38 (4-cell ultrahypoxia) as failed reactions. To confirm the quality of the RNA sequencing, we analyzed the expression values of the housekeeping genes (ACTB, ACTG1, ACTG2, TUBA1B, TUBA1C)27,28 and known developmental genes (NANOG, POU5F1, GDF9, SLC34A2) (Fig. 2A). All the housekeeping genes had the expression levels trends expected in each embryo stage in accordance with the previous literature findings. NANOG and POU5F1 (OCT4) are pluripotency markers which expression increases during the development29, and our data showed these having higher expression in blastocyst stage. GDF9 is an oocyte secreted factor, and its expression was high in oocytes and in the early stages of the development, while it was lower after EGA in 16-cell and blastocyst stages. SLC34A2 is an EGA marker expressed at the 16-cell stage in bovine, as also confirmed after 16-cell of development in our data. We then performed unsupervised clustering of the samples. As seen on the UMAP, early stages of development from oocytes to 8-cell stage embryos clustered together, while later stages (16-cell and blastocysts) clustered closer together and separate from the earlier stages (Fig. 2B). Similarly, in the principal component analysis, the largest variance between samples (PC1) also separated the earlier stages from later stages, while PC2 separated 16-cell from the blastocysts (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Quality control of RNA seq library and unsupervised sample clustering. (A) Violin plots for gene expression of selected genes across different embryo development stages. Housekeeping genes ACTB, ACTG1, ACTG2, TUBA1B and TUBA1C show the expected variations in the gene expression across the development stages. The developmentally important genes NANOG, POU5F1, GFD9 and SLC34A were selected for gene expression trends in this RNA sequencing library. Y-axis presents log-normalized expression levels. (B) Unsupervised clustering was performed with R Seurat package. The UMAP plot shows that the earlier stages of embryo development cluster together and separately from the later stages: 16-cell stage and blastocyst embryos.

Embryonic genome activation in bovine in hypoxia and normoxia

During maternal to embryonic switch, mRNA molecules from the oocyte are degraded. We did not observe any differentially expressed genes (DEG) between the zygote stage and 4-cell embryos in any conditions, different from Graf et al., (2014). We believe that this is due to the different sequencing and normalization methods used.

The first downregulation of genes was observed at the 8-cell stage, during which 732 genes were downregulated in the hypoxia condition, while in normoxia, only 47 genes were downregulated (Fig. 3). The difference between the groups is also seen in UMAP where the normoxia 8-cell embryos cluster away from the 8-cell hypoxia embryos (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 3.

Visual demonstration of the embryonic genome activation (EGA) in bovine embryos. (A) The track shows the transcriptional changes of embryos grown under hypoxia. The top left graph shows the differences between 8-cell stage embryos and zygotes demonstrating the first downregulation of the maternal genes (brown). On the right, we see the comparison of 16-cell embryos to zygotes, and we can see the major EGA wave in bovine, where the majority of genes is downregulated (brown) and first upregulation of the newly formed embryo transcripts appears (green). Nonsignificant changes are shown in grey. (B) The track shows the transcriptional changes of embryos grown under normoxia. Bottom left graph presents comparison of 8-cell stage embryos against zygotes, with first downregulation of genes (brown), while the right graph demonstrates the transcriptomic changes in 16-cell stage embryos against zygotes. Downregulated genes are in brown, nonsignificant in grey, and upregulated genes in green. For the genes to be significantly downregulated or upregulated, the FDR of 5% was used.

The biggest change in DEG profile was observed between 16-cell and zygote. Here, we observed the major wave of EGA at the 16-cell stage both in hypoxia (n = 5) and normoxia (n = 3), where also the largest maternal mRNA downregulation occurred (Fig. 3).

Gene expression during EGA

In human IVF, around 45–50% of embryos stall around 8-cell stage31, which corresponds to the initiation of EGA in humans. We next asked if the O2 concentration impacts the EGA in bovine embryos. On the first look, embryos at both conditions managed to achieve EGA at 16-cell but we observed major differences in genes that were up- and downregulated at this stage in comparison to zygotes. There were 253 and 260 upregulated genes in hypoxia and normoxia, respectively. Of these 167 genes were common, while 86 and 93 were unique to hypoxia and normoxia, respectively (Fig. 4A; Supplementary Table 3. Gene ontology (GO) analysis revealed that the upregulated genes in hypoxia were involved in binding, translation activity and RNA biosynthetic process and metabolism of RNA, indicating that embryos were preparing for the novel transcription, DNA replication and progress towards next stages of development (Fig. 4C). In normoxia, similar GO results were seen (Fig. 4E) but interestingly, in hypoxia the number of genes involved in these processes appeared was much higher than in normoxia.

Fig. 4.

Differences in the transcription profile of 16-cell embryos grown under hypoxia and normoxia. (A) Venn-Diagram of the upregulated genes at the 16-cell stage embryos against zygotes in hypoxia and normoxia. (B) Venn-Diagram of the downregulated genes at the 16-cell stage embryos against zygotes in hypoxia and normoxia. (C) Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of the genes upregulated at the 16-cell stage in hypoxia. The GO analysis includes molecular function (MF), biological processes (BP) and reactome (REAC). X-axis shows the number of genes that are identified under the GO term. (D) Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis of the downregulated genes at the 16-cell stage in hypoxia. (E) GO analysis of the genes upregulated at the 16-cell stage in normoxia. This GO analysis includes MF, BP and REAC features. X-axis shows the number of genes that are identified under the GO term. (F) KEGG analysis of the downregulated genes in normoxia. For term and pathway in GO and KEGG analysis, a significance threshold of 5% FDR was used.

The largest downregulation of genes appeared at the 16-cell stage where 5,785 genes or 61% of all genes in zygote stage were downregulated in hypoxia and 4,829 or 50% of genes were downregulated in normoxia (Fig. 4B). To understand the function of these genes, we performed KEGG pathway analysis. In both conditions, genes related to oocyte maturation, cell cycle, autophagy and mitophagy pathways were downregulated. Surprisingly, pyruvate metabolism, carbon metabolism, 2-oxocarboxylic acid metabolism and the TCA cycle were downregulated in both conditions (Supplementary Table 4 A, 4B, Supplementary Fig. 3, 4) which was unexpected as it is thought that pyruvate is the main energy source in the early stages of embryo development until blastocyst stage. However, in hypoxia we can also see that AMPK pathway was downregulated, suggesting that the AMP/ATP ratio inside the embryo was at a satisfactory level and that these cells do not lack energy (Fig. 4D).

Besides failing to downregulate many genes in comparison to hypoxia, normoxia embryos also downregulated some of the pathways necessary for genomic integrity. The p53 signaling pathways play vital roles in genome stability, apoptosis induction and cell cycle regulation. Their downregulation in normoxia suggested that embryos grown in normoxia were deficient in the system to respond to possible DNA damage. Additionally, the HIF-1 signaling pathway was also downregulated in normoxia (Fig. 4F). HIF-1 has been shown to play a vital role in EGA and metabolic adaptation as well as in expression of genes involved in angiogenesis, such as upregulation of the VEGF and GLUT-332. The Hippo signaling pathway, which plays an important role in cell fate differentiation and cell position and is important for blastocyst formation and implantation was also downregulated in the normoxia embryos.

Ultrahypoxia rescued the embryo energy metabolism in the blastocysts while normoxia altered it

The use of normoxia or hypoxia in the embryo culture has been long debated with recent discussions whether the best condition for the embryo culture is a sequential ultra-low O2 concentration. To test this hypothesis, we decided to lower the concentration of O2 after 16-cell stage until the blastocyst stage. This gave us the opportunity to get a transcriptional profile of all three O2 concentrations. We compared blastocysts in each condition against the 16-cell stage embryos. A major upregulation of genes was seen both in hypoxia (1,991) and ultrahypoxia (1,967) blastocysts while in normoxia blastocysts upregulation of only one quarter of those (539) was observed (Fig. 5A-D). Interestingly, in terms of transcriptional downregulation the largest difference was seen in ultrahypoxia (1,338) in contrast to normoxia with 663 genes, and only 222 in hypoxia (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Comparison of blastocysts transcriptomic profiles grown under hypoxia, normoxia and ultrahypoxia. (A) Volcano plot representation of the transcriptional difference in the blastocysts grown under hypoxia against 16-cell stage hypoxia embryos. (B) Volcano plot representation of the transcriptional difference in the blastocysts grown under normoxia against 16-cell stage normoxia embryos. (C) Volcano plot representation of the transcriptional difference in the blastocysts grown under ultrahypoxia against 16-cell stage hypoxia embryos. Downregulated genes are shown in brown, not significant in grey and upregulated genes in green. (D) Number of differentially expressed genes (DEG) in blastocysts against 16-cell embryos across the 3 experimental conditions. (E) Chord diagram of the KEGG pathways upregulated at the blastocysts stage against 16-cell stage embryos in all 3 conditions, showing which KEGG pathways are shared between all 3 conditions (pink), only in hypoxia and ultrahypoxia (beige), only in hypoxia (purple), only in ultrahypoxia (green) and only in normoxia (yellow) marked as NO on the figure.

Next, we wanted to define the influence that O2 concentration had on the genes regulating energy metabolism of the blastocysts. At this time of development, blastocysts should be powered mostly by glucose, making glycolysis the key energy pathway. We observed that all 3 groups had genes upregulated in the oxidative phosphorylation pathway, but only hypoxia and ultrahypoxia blastocysts had pyruvate metabolism and the TCA cycle genes upregulated (Fig. 5E). The largest difference in the metabolism-related gene expression could be seen in the glycolysis/gluconeogenesis pathway that was only active in hypoxia and ultrahypoxia. In addition, genes related to amino acid biosynthesis of arginine, proline, valine, leucine and isoleucine were present in both hypoxia and ultrahypoxia while absent from the normoxia condition. Genes involved in lipid metabolism including fatty acid biosynthesis, biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids, steroid biosynthesis and sphingolipid metabolism were also only present in the hypoxia and ultrahypoxia conditions (Fig. 5E). Overall, even though the blastocyst formation rate in our experiment was the lowest in the ultrahypoxia condition, the transcriptomic profile of the blastocysts grown in the ultrahypoxia was similar to the hypoxia condition with the key genes in energy metabolism necessary for the further cell differentiation and later organogenesis upregulated in ultrahypoxia. Normoxia blastocysts showed that they were much slower to achieve the full transcriptional awakening at the blastocyst stage and had altered expression of energy metabolism genes that can have further consequences for the development.

Discussion

The oxygen level used for in vitro embryo culture has been a topic of discussions for many years. The main question is whether culturing embryos under physiological O2 levels (hypoxia) is beneficial in comparison to culturing embryos under atmospheric O2 (normoxia). There is an increasing amount of evidence suggesting that hypoxia is superior compared to normoxia. In human normoxia, IVF success rate of embryo cultures is around 30%, while hypoxia increases the success rate up to 32–43%10. Kovačič and Vlaisavljević33 showed that the proportion of good quality embryos at day 3 and higher blastocyst formation rate were achieved in hypoxia. Van Montfoort et al.34 included both fresh and frozen embryos (5–7 years follow up) in their study, and found hypoxia yielding significantly more good quality embryos and live births in comparison to the normoxia group using day 2–3 embryos. On the contrary, De Los Santos et al.35 did not find any difference in the clinical pregnancy rate between the two conditions using day 2–3 embryos. This is possibly due to different ways of calculating the pregnancy rate and no information was provided on the period of the follow up with the study participants and if more embryos were left cryopreserved.

Due to ethical limitations to use human embryos, literature lacks evidence about the impact O2 concentration has on the transcriptomic level. To reach molecular understanding, mouse embryos have been used. Kelley and Gardner12 tested the effect of normoxia and hypoxia and found that normoxia decreased the blastocyst formation rate, but also altered the energy metabolism by decreasing the uptake of amino acids leucine, methionine, and threonine, as well as the uptake of glucose and aspartate. Belli et al.11 tested the impact of normoxia on mitochondria. They showed that blastocysts derived from normoxia had a lower mitochondrial DNA copy number and fewer mitochondria compared to the hypoxia. In bovine embryos, an early study by Thomson et al. (1990) looked at the number of nuclei/embryo at 8- and 16-cell stage embryos and found the number to be highest at low O2 (8%) in comparison to 20% O236. This finding was confirmed by Lim et al.37, who found the number of bovine hatched blastocysts to be significantly higher in the low oxygen group37. Similarly to mouse embryos, the number of cells in blastocysts and morula in bovine embryos decreased when the embryos were cultured in normoxia38.

In this study, we chose bovine embryos as a model organism due to their closer resemblance to humans. We employed STRT-N RNA-seq to differentiate between maternal and embryonic transcripts. Proper data normalization is crucial in embryology studies, as most methods assume that the majority of co-expressing genes are not differentially expressed between samples. However, this assumption does not hold during embryo development because of significant transcriptional shifts between stages by maternal transcript degradation39. By using the appropriate normalization technique, specifically the ERCC Spike-ins, we successfully accounted for sample heterogeneity in our data.

We showed that normoxia slows down the degradation of the maternal transcripts during the EGA. Degradation of the maternal transcripts and switch to the embryonic transcription are prerequisites to normal development. Normoxia influenced EGA in bovine embryos by failing to downregulate 1,149 genes at 16-cell stage. Moreover, we observed downregulation of the HIF-1 signaling pathway that has been highlighted as the cellular response to hypoxia, but, interestingly, HIF-1 also regulates transcription of many genes involved in glucose uptake, glycolysis, angiogenesis, proliferation, and autophagy40. The influence of the HIF-1 signaling pathway on the development has been studied in mouse and bovine embryos. In mouse, it has been shown that HIF-1 has a direct upregulating impact on the expression of several major EGA genes13 and that HIF-1 is degraded in normoxia, confirming the previous reports of HIF-1 degradation by O2 concentration41–43. One of the HIF-1 targets is vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), that is important for angiogenesis and the connection of the embryo and endometrium during embryo implantation, and it has been shown to have an impact in the recurrent implantation failure44. In addition, Compernolle et al.45 showed that some HIF-1α −/− embryos developed cardia bifida while others showed disrupted cardiac looping45. HIF-1 and its role in cardiovascular diseases and as a possible drug target have been extensively studied and reviewed46. Recently, HIF-1 was proposed as the key regulator of the nervous system development of Drosophila melanogaster47. Downregulation of HIF-1 signaling in normoxia embryos can have a detrimental effect on the development potential of embryos, although its role may not be evident in the first few days of development.

In our study, the Hippo pathway and signaling pathways regulating stem cell pluripotency were also downregulated at the 16-cell stage in normoxia embryos. The Hippo pathway works through the two activators, YAP and TAZ, and has been shown to regulate cell differentiation and specialization of trophectoderm (TE) and inner cell mass (ICM)48. Large tumor suppressor kinase (LATS) is known as Hippo pathway inhibitor. In mouse, suppressing LATS1/2 expression during preimplantation development by siRNA injection disrupts Hippo signaling pathway, leading to cell fate misspecification in ICM and ultimately the failure of embryos to undergo gastrulation49.

We also observed that normoxia disrupted the expression of genes involved in energy metabolism of the blastocysts. While blastocysts’ main energy source should be glucose, we found that in normoxia blastocysts genes involved in glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, and synthesis of amino acids were not significantly upregulated. The lack of energy could partially explain lower developmental competence and, for example, lower mtDNA counts in normoxia blastocysts observed by Belli and colleagues11. This question becomes even more relevant considering the new findings that glucose gradient might be involved in gastrulation and mesoderm establishment50,51.

In addition to testing the difference between hypoxia and normoxia, we tested the effect of sequential ultralow O2 concentration on the bovine embryo development. We compared the transcriptional profile of the ultrahypoxia blastocysts and hypoxia blastocysts. We found a larger number of downregulated genes in the ultrahypoxia blastocysts when compared against 16-cell stage than in the same comparison done with hypoxia blastocysts. However, the energy metabolism profile, as estimated by upregulated DEGs, of the ultrahypoxia blastocysts was similar to the hypoxia. Contrary to normoxia blastocysts, ultrahypoxia blastocysts had upregulated genes related to glycolysis, amino acid synthesis and fatty acids biosynthesis. Morin et al. (2018) performed RNA sequencing on ICM and TE from aneuploid human blastocysts. They did not find differences in the transcription profiles of the blastocysts grown in monophasic 5% or sequential 5 –2% O2. Yang et al.16 compared the 2%, 5% and 20% O2 levels in human embryo development. They also investigated the expression of the genes related to the TE and placentation and showed the difference between the 20% O2 and hypoxia conditions but saw no difference between 5% and 2% O2 groups.

De Munck et al.17 performed a randomized trial where human embryos on day 3 of development were either continuously grown under 5% O2 or moved to 2% O2. They found no difference in the blastocyst formation rate and proportion of good quality embryos. Yang et al.16 did not observe any difference in the blastocyst formation rate between 5% and 2% O2, but they did find lower cell number in the blastocysts grown at 2%. In our experiments with bovine embryos, the lowest blastocyst formation rate was in the ultrahypoxia condition, but in the current study the cell number in the blastocysts across the conditions was not counted.

Despite the similar transcriptomic profiles between ultrahypoxia and hypoxia blastocysts observed in our study and in previous human reports, some studies call for caution of switching to the 2% O2. Feil et al.53 tested these three O2 conditions in the mouse embryo development and showed that fetal weight on day 18 was lower in embryos cultured at 2% O2. Similarly, Kaser et al.15 showed some adverse effects of 2% O2, as they observed fewer cells in the blastocysts as well as in the absorption of amino acids and their abundance and expression of MUC1 in the TE. The discrepancies among different studies regarding the 2% O2 culture condition can be attributed to variations in experimental design, sample sizes, and species-specific responses. Before implementing this culture condition in IVF clinics, more animal studies using models such as bovine, which are physiologically similar to humans, should be conducted. Additionally, working with leftover day-3 embryos in humans and performing detailed molecular transcriptomic analyses, rather than solely focusing on blastocyst formation rates, would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the effects of 2% O2 on embryo development.

In addition to the oxygen levels during IVC, it would be interesting to test oxygen levels during IVM. In our study, IVM was performed at normoxia level, however, newer reports are suggesting that it might be beneficial for bovine embryos to have IVM performed at hypoxia54,55. Combining hypoxia for IVM and IVC might give the best system for the culture of bovine IVF embryos.

In summary, we provided transcriptional profiles of bovine embryos grown in normoxia, hypoxia and hypoxia/ultrahypoxia. While this study was done with a relatively low number of embryos, this limitation was addressed with additional normalization technique as well as combining the hypoxia and ultrahypoxia samples up to the 16-cell stage. Normoxia had a detrimental influence on the transcriptomic switch of the embryo by slowing down the downregulation of the maternal transcripts during EGA, but also by downregulating developmentally critical pathways and failing to upregulate proper energy metabolism. We hypothesize that all of these might be reasons for the normoxia grown embryos resulting in lower number of live births in humans. Ultrahypoxia blastocysts had similar profiles to hypoxia by upregulating the energy metabolism needed to fuel the blastocysts. Despite this, we saw the lowest blastocyst formation rate in ultrahypoxia, opposite to previous reports in human. As there is no clear benefit of lowering the O2 to 2% and considering the extra costs needed for such ultrahypoxia culture, we propose monophasic low O2 concentration as optimal for in vitro embryos culture systems.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Biomedicum Functional Genomics Unit (FuGU), University of Helsinki, for library sequencing services. The bioinformatics data analyses were performed on CSC – IT Center for Science, (Finland). This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 813707. Work in the JK laboratory is supported by Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation, Sigrid Jusélius Foundation, Liv och Hälsa (Finland), Swedish Brain Foundation and Swedish Research Council. The study was also supported by the Estonian Research Council (grant no. PRG1076) and the Horizon Europe NESTOR project (grant no. 101120075).

Author contributions

N.B. study design, embryology experiments, RNA sequencing experiments, data analysis, writing the original draft, manuscript revision; M.I. embryology experiments, manuscript revision; G.Y., B.Y. preprocessing of RNA sequencing data; S.K., K.L., T.T., T.O., A.K., A.S., supervision, study design, review & editing of manuscript; C.D., supervision of data analysis, review & editing of manuscript; J.K., conceptualization, supervision, writing, review & editing, project administration and funding acquisition.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute.

Data availability

The raw data (BCL files) are available at Zenodo: https://zenodo.org/records/13384652 and FASTQ files are available in EMBLEBI BioStudies with accession number S-BSST1680. The code used to perform downstream analysis and generate all the main and supplementary figures can be found on the GitHub page: https://github.com/nina-boskovic/STRTN-Bovinepreimplantation-embryos.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Nina Boskovic, Email: nina.boskovic@ki.se.

Juha Kere, Email: juha.kere@ki.se.

Reference list

- 1.Donjacour, A., Liu, X., Lin, W., Simbulan, R. & Rinaudo, P. F. In vitro fertilization affects growth and glucose metabolism in a Sex-Specific manner in an outbred mouse Model1. Biol. Reproduct.90 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Sun, W. J. et al. Exogenous glutathione supplementation in culture medium improves the bovine embryo development after in vitro fertilization. Theriogenology84, 716–723 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang, H. et al. Effects of changing culture medium on preimplantation embryo development in rabbit. Zygote30, 338–343 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pasquariello, R. et al. Lipid-enriched reduced nutrient culture medium improves bovine blastocyst formation. Reprod. Fertil. 4, e230057 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kleijkers, S. H. M. et al. Influence of embryo culture medium (G5 and HTF) on pregnancy and perinatal outcome after IVF: A multicenter RCT. Hum. Reprod.31, 2219–2230 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steptoe, P. C., Edwards, R. G. & Purdy, J. M. Human blastocysts grown in culture. Nature229, 132–133 (1971). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischer, B. & Bavister, B. D. Oxygen tension in the oviduct and uterus of rhesus monkeys, hamsters and rabbits. Reproduction99, 673–679 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christianson, M. S. et al. Embryo catheter loading and embryo culture techniques: Results of a worldwide web-based survey. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet.31, 1029–1036 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sciorio, R. & Rinaudo, P. Culture conditions in the IVF laboratory: State of the ART and possible new directions. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet.40, 2591–2607 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bontekoe, S. et al. Low oxygen concentrations for embryo culture in assisted reproductive technologies. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 10.1002/14651858.CD008950.pub2 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belli, M. et al. Oxygen concentration alters mitochondrial structure and function in in vitro fertilized preimplantation mouse embryos. Hum. Reprod.34, 601–611 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelley, R. L. & Gardner, D. K. Individual culture and atmospheric oxygen during culture affect mouse preimplantation embryo metabolism and post-implantation development. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 39, 3–18 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao, F. et al. Single-embryo transcriptomic atlas of oxygen response reveals the critical role of HIF-1α in prompting embryonic zygotic genome activation. Redox Biol.72, 103147 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morin, S. J. Oxygen tension in embryo culture: Does a shift to 2% O2 in extended culture represent the most physiologic system? J. Assist. Reprod. Genet.34, 309–314 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaser, D. J., Bogale, B., Sarda, V., Farland, L. V. & Racowsky, C. Randomized controlled trial of low (5%) vs. ultralow (2%) oxygen tension for in vitro development of human embryos. Fertil. Steril.106, e4 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang, Y. et al. Comparison of 2, 5, and 20% O2 on the development of post-thaw human embryos. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet.33, 919–927 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Munck, N. et al. Influence of ultra-low oxygen (2%) tension on in-vitro human embryo development. Hum. Reprod.34, 228–234 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boskovic, N. et al. Optimized single-cell RNA sequencing protocol to study early genome activation in mammalian preimplantation development. STAR. Protocols. 4, 102357 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santos, R. R., Schoevers, E. J. & Roelen, B. A. Usefulness of bovine and Porcine IVM/IVF models for reproductive toxicology. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol.12, 117 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Otoi, T., Yamamoto, K., Koyama, N., Tachikawa, S. & Suzuki, T. Bovine oocyte diameter in relation to developmental competence. Theriogenology48, 769–774 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Töhönen, V. et al. Novel PRD-like homeodomain transcription factors and retrotransposon elements in early human development. Nat. Commun.6, 8207 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jouhilahti, E. M. et al. The human PRD-like homeobox gene LEUTX has a central role in embryo genome activation. Development Dev.13451010.1242/dev.134510 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Yaşar, B. et al. Molecular cloning of PRD-like homeobox genes expressed in bovine oocytes and early IVF embryos. BMC Genom.25, 1048 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bó, G. A. & Mapletoft, R. J. Evaluation and classification of bovine embryos. Anim. Reprod. (AR). 10, 344–348 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: Biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res.53, D672–D677 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaskar, K. et al. Effect of ultra-low oxygen (2%) environment on mouse embryo morphokinetics and blastocyst development. Fertil. Steril.112, e270–e271 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bilodeau-Goeseels, S. & Schultz, G. A. Changes in the relative abundance of various housekeeping gene transcripts in in vitro-produced early bovine embryos. Mol. Reprod. Dev.47, 413–420 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ross, P. J., Wang, K., Kocabas, A. & Cibelli, J. B. Housekeeping gene transcript abundance in bovine fertilized and cloned embryos. Cell. Reprogramm. 12, 709–717 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Canizo, J. R. et al. A dose-dependent response to MEK Inhibition determines hypoblast fate in bovine embryos. BMC Dev. Biol.19, 13 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graf, A. et al. Fine mapping of genome activation in bovine embryos by RNA sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111, 4139–4144 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orvieto, R. et al. Cleavage-stage human embryo arrest, is it embryo genetic composition or others? Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol.20, 52 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma, Y. Y., Chen, H. W. & Tzeng, C. R. Low oxygen tension increases mitochondrial membrane potential and enhances expression of antioxidant genes and implantation protein of mouse blastocyst cultured in vitro. J. Ovarian Res.10, 47 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kovačič, B. & Vlaisavljević, V. Influence of atmospheric versus reduced oxygen concentration on development of human blastocysts in vitro: A prospective study on sibling oocytes. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 17, 229–236 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Montfoort, A. P. A. et al. Reduced oxygen concentration during human IVF culture improves embryo utilization and cumulative pregnancy rates per cycle. Hum. Reprod. Open hoz036 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.De Los Santos, M. J. et al. Reduced oxygen tension improves embryo quality but not clinical pregnancy rates: A randomized clinical study into ovum donation cycles. Fertil. Steril.100, 402–407 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thompson, J. G., Simpson, A. C., Pugh, P. A., Donnelly, P. E. & Tervit, H. R. Effect of oxygen concentration on in-vitro development of preimplantation sheep and cattle embryos. J. Reprod. Fertil.89, 573–578 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lim, J. M., Reggio, B. C., Godke, R. A. & Hansel, W. Development of in-vitro-derived bovine embryos cultured in 5% CO2 in air or in 5% O2, 5% CO2 and 90% N2. Hum. Reprod.14, 458–464 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olson, S. E. & Seidel, G. E. Reduced oxygen tension and EDTA improve bovine zygote development in a chemically defined medium. J. Anim. Sci.78, 152–157 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katayama, S., Töhönen, V., Linnarsson, S. & Kere, J. SAMstrt: statistical test for differential expression in single-cell transcriptome with spike-in normalization. Bioinformatics29, 2943–2945 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bracken, C. P., Whitelaw, M. L. & Peet, D. J. The hypoxia-inducible factors: Key transcriptional regulators of hypoxic responses. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. (CMLS). 60, 1376–1393 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salceda, S. & Caro, J. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) protein is rapidly degraded by the Ubiquitin-Proteasome system under normoxic conditions. J. Biol. Chem.272, 22642–22647 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lando, D. et al. FIH-1 is an Asparaginyl hydroxylase enzyme that regulates the transcriptional activity of hypoxia-inducible factor. Genes Dev.16, 1466–1471 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marxsen, J. H. et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) promotes its degradation by induction of HIF-α-prolyl-4-hydroxylases. Biochem. J.381, 761–767 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taghizadeh, E. et al. Abnormal angiogenesis associated with HIF-1α/VEGF signaling pathway in recurrent miscarriage along with therapeutic goals. Gene Rep.26, 101483 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Compernolle, V. et al. Cardia bifida, defective heart development and abnormal neural crest migration in embryos lacking hypoxia-inducible factor-1α. Cardiovascul. Res.60, 569–579 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sato, T. & Takeda, N. The roles of HIF-1α signaling in cardiovascular diseases. J. Cardiol.81, 202–208 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sobrido-Cameán, D. et al. Critical period signalling directs nervous system development through mitochondrial ROS and HIF-1α. 11.22.624842 Preprint at (2024). 10.1101/2024.11.22.624842 (2024).

- 48.Yildirim, E., Bora, G., Onel, T., Talas, N. & Yaba, A. Cell fate determination and Hippo signaling pathway in preimplantation mouse embryo. Cell. Tissue Res.386, 423–444 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lorthongpanich, C. et al. Temporal reduction of LATS kinases in the early preimplantation embryo prevents ICM lineage differentiation. Genes Dev.27, 1441–1446 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bulusu, V. et al. Spatiotemporal analysis of a glycolytic activity gradient linked to mouse embryo mesoderm development. Dev. Cell. 40, 331–341e4 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cao, D. et al. Selective utilization of glucose metabolism guides mammalian gastrulation. Nature10.1038/s41586-024-08044-1 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morin, S. et al. Ultra-low oxygen (O2) tension after day 3 of in vitro development does not alter blastocyst transcriptome: A comparison of 2% versus 5% o2 tension in extended culture. Fertil. Steril.110, e51 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Feil, D. et al. Effect of culturing mouse embryos under different oxygen concentrations on subsequent fetal and placental development. J. Physiol.572, 87–96 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Whitty, A., Kind, K. L., Dunning, K. R. & Thompson, J. G. Effect of oxygen and glucose availability during in vitro maturation of bovine oocytes on development and gene expression. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet.38, 1349–1362 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bermejo-Alvarez, P., Lonergan, P., Rizos, D. & Gutiérrez-Adan, A. Low oxygen tension during IVM improves bovine oocyte competence and enhances anaerobic Glycolysis. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 20, 341–349 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data (BCL files) are available at Zenodo: https://zenodo.org/records/13384652 and FASTQ files are available in EMBLEBI BioStudies with accession number S-BSST1680. The code used to perform downstream analysis and generate all the main and supplementary figures can be found on the GitHub page: https://github.com/nina-boskovic/STRTN-Bovinepreimplantation-embryos.