ABSTRACT

Plasmodium falciparum expresses four heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) members. Among these, one, glucose‐regulated protein 94 (PfGrp94), is localized in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Both the cytosolic and ER‐based Hsp90s are essential for parasite survival under all growth conditions. The cytosolic version has been extensively studied and has been targeted in several efforts through the repurposing of anticancer therapeutics as antimalarial drugs. However, PfGrp94 has not been fully characterized and some of its functions related to the ER stress response are not fully understood. Structural analysis of the recombinant full‐length PfGrp94 protein showed a predominantly α‐helical secondary structure and its thermal resilience was modulated by 5′‐N‐ethyl‐carboxamide‐adenosine (NECA) and nucleotides ATP/ADP. PfGrp94 exhibits ATPase activity and suppressed heat‐induced aggregation of a model substrate, malate dehydrogenase, in a nucleotide‐dependent manner. However, these PfGrp94 chaperone functions were abrogated by NECA. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations showed that NECA interacted with unique residues on PfGrp94, which could be potentially exploited for selective drug design. Finally, using parasites maintained at the red blood stage, NECA exhibited moderate antiplasmodial activity (IC50 of 4.3, 7.4, and 10.0 μM) against three different P. falciparum strains. Findings from this study provide the first direct evidence for the correlation between in silico, biochemical, and in vitro data toward utilizing the ER‐based chaperone, PfGrp94, as a drug target against the malaria parasites.

Keywords: characterization, endoplasmin, glucose regulated protein 94 (Grp94), inhibition, malaria, NECA, Plasmodium falciparum

1. Introduction

The Plasmodium falciparum 94 kDa glucose‐regulated protein (PfGrp94), also known as endoplasmin, is a Hsp90 homologue localized in the parasite's endoplasmic reticulum (ER). PfGrp94 has been implicated in the stabilization of secreted and membrane‐bound client proteins that are required for parasite survival [1]. These clients include parasite proteins that are destined for export to the host red blood cells (RBC) for host cell remodeling and those that are secreted to other parasitic cell compartments [2].

In humans, Grp94 facilitates the folding of clients that are required during the early developmental stages as well as components of signal transduction. Furthermore, Grp94 proteins dictate the fate of stressed cells through their protein unfolding rescue functions during the unfolded protein response (UPR) [3, 4]. In P. falciparum, artemisinin treatment has been shown to induce ER stress [5]. The ER stress response to drug treatment determines the fate of the parasite: those that elicit a successful UPR develop resilience, while those that do not become susceptible to drug pressure. This suggests that the failure of ER chaperones (such as PfGrp94) to facilitate the folding and rescuing of ER‐localized stressed proteins results in the accumulation of misfolded proteins, ultimately leading to ER‐dysfunction [6, 7].

The general structure of Grp94 is conserved as in other Hsp90s, being composed of an N‐terminal domain (NTD), a middle domain, and a C‐terminal domain (CTD). The N‐terminal of the human Grp94 protein consists of a short, disordered signal peptide that is required for the translocation of the newly synthesized proteins into the ER lumen [8]. Grp94 has the longest pre‐NTD out of all the Hsp90 paralogs, which is thought to influence the binding of ATP and ATP hydrolysis rate [9]. The middle domain, which is connected to the NTD via a charged linker, is the main substrate binding domain and it contains an asparagine residue that activates the ATPase activity of the NTD. This suggests that nucleotide‐binding and hydrolysis are essential for Grp94 chaperone function. It was also shown that nucleotide exchange of Grp94 is important for substrate binding and release cycles that facilitate protein folding [10]. The CTD ends with a signature S/K/N‐DEL ER‐retention signal which replaces the Hsp90 co‐chaperone binding EEVD motif of its cytosolic equivalent [11]. It still remains to be determined how Grp94 associates with potential functional partners in the ER. It is interesting to note that to date no Grp94 co‐chaperones have been experimentally validated in the parasite. This suggests that PfGrp94 is specialized to function in the ER, partly explaining its indispensable role in parasite survival [12].

In canines and yeasts, the ATP‐mimicking inhibitor 5′‐N‐ethyl‐carboxamide‐adenosine (NECA) was shown to be selective toward the ER Hsp90 homologue, Grp94 [13, 14]. This presents NECA as a potential Grp94 selective inhibitor, however, its potency toward the parasite PfGrp94 has not been evaluated. In addition, there is limited evidence on the function of the parasite Grp94. Therefore, this study sought to produce and characterize the full‐length recombinant form of PfGrp94 and evaluate the effect of NECA on its structure and chaperone function. Findings from this study provide direct evidence that NECA modulates the structure and abrogates the chaperone function of PfGrp94. Furthermore, NECA was shown to exhibit moderate antiplasmodial activity, which may at least in part be due to its effects on PfGrp94 function. This suggests that small molecule inhibitors targeting PfGrp94 are potential antimalarial therapeutics.

2. Results

2.1. Recombinant Protein Production

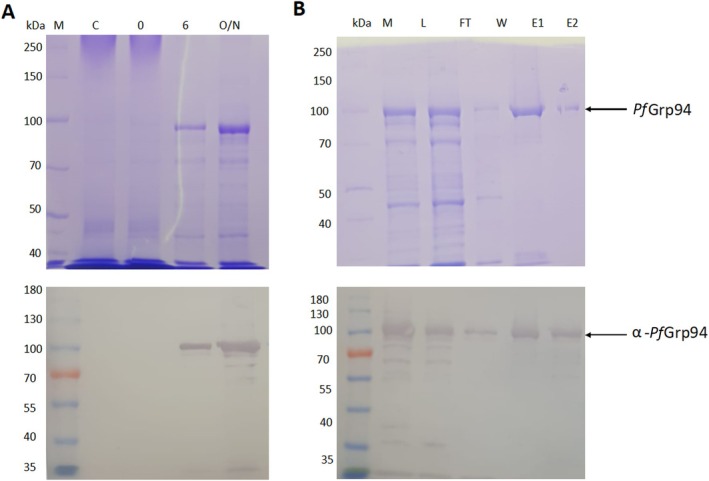

The recombinant PfGrp94 full‐length protein was expressed in Escherichia coli XL1 Blue cells. SDS‐PAGE analysis of the samples collected from cells transformed with PQE30‐PfGrp94 showed a more prominent band that migrated at 90 kDa when compared to the control lane. These observations showed that PfGrp94 was successfully expressed at 16°C following 1 mM IPTG induction (Figure 1A). Western Blot analysis using rabbit‐raised polyclonal α‐PfGrp94 antibodies confirmed the presence of a 90 kDa band corresponding to the expected size of recombinant PfGrp94.

FIGURE 1.

PfGrp94 protein expression and purification. SDS‐PAGE analysis of PfGrp94 expression in E. coli XL1‐Blue cells (A) and the purification of recombinant PfGrp94 protein using immobilized metal‐affinity chromatography (B). Western blot analysis of the expression and purification of the protein using polyclonal rabbit‐raised α‐PfGrp94 antibodies (lower panels). Lane M: protein molecular weight marker (kDa); Lane C: control (untransformed E. coli XL1‐Blue cells); Lane 0: total extract for cells transformed with pQE30/PfGrp94 before IPTG induction; Lanes 6 and O/N: total lysate obtained 6 and 16 h respectively post‐induction with 1 mM IPTG at 16°C; Lane L: cell lysate; Lane F: flowthrough; Lane W: wash containing unbound proteins, Lanes E1 and E2: fraction eluted at 100 and 500 mM imidazole, respectively.

The recombinant PfGrp94 was purified by immobilized metal‐affinity chromatography (IMAC) and samples were analyzed with SDS‐PAGE (Figure 1B). The soluble whole cell lysate was loaded onto the IMAC resin and the flow through confirmed high efficiency binding to the resin as a thin band was detected corresponding to the expected PfGrp94 migration pattern. The elution of the protein by increasing the concentration from 100 to 500 mM of imidazole resulted in a protein with an approximate 95% purity. The recombinant PfGrp94 expression and purification were confirmed by Western blot using α‐PfGrp94 antibodies that we produced (Figure 1 lower panels). The specificity of the polyclonal rabbit‐raised α‐PfGrp94 antibodies was validated by probing recombinant PfGrp94 proteins alongside a recombinant form of P. falciparum ER resident PfGrp170 protein (Figure S1). The α‐PfGrp94 antibody selectively bound to bands corresponding to the recombinant PfGrp94 protein without cross‐reacting with those from PfGrp170.

2.2. Secondary Structure Analysis of PfGrp94

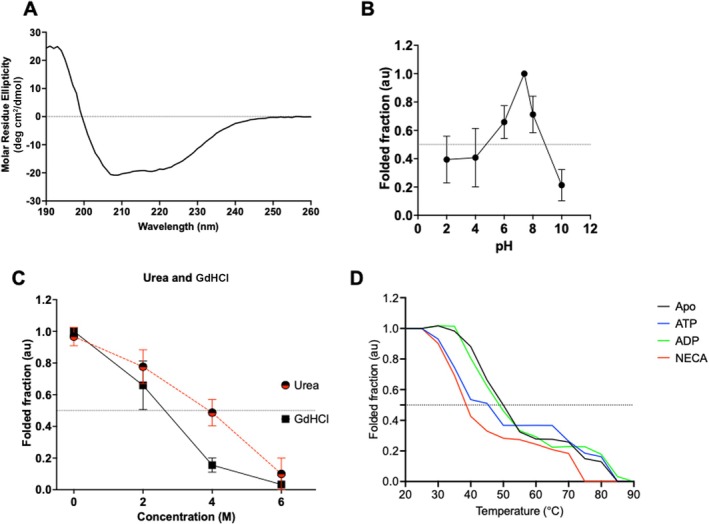

Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy was used to elucidate the secondary structural features of the recombinant PfGrp94 protein. The CD spectra of PfGrp94 were observed to register a maximum positive peak at 192 nm, and two negative troughs at 208 and 220 nm (Figure 2A). The observed spectra of 35% α‐helices, 19% β‐sheets, and 46% turns/unordered regions were consistent with proteins that possess predominantly α‐helical secondary structure elements. These deconvoluted secondary structure distributions were within the same range with AlphaFold prediction of 38% α‐helices, 17% β‐sheets, and 45% turns (Table S1). We probed for the stability of the protein using different pH and different chaotropic agents. The ER is the master regulator of a cell's pH based on calcium ion homeostasis. We observed that PfGrp94 observed a peak in stability at a pH between 6 and 8 with the maximum fold at pH 7.4 (Figure 2B). This suggests that the recombinant PfGrp94 is stable in the general pH ranges of the ER. As a control, using urea and guanidine HCl the known chaotropic agents, we show the decrease in the folded fraction of PfGrp94 when the concentration of these agents is increased (Figure 2C). Guanidine HCl was more effective at destabilizing the folded fraction of PfGrp94 than urea. This suggests that the recombinantly produced protein was stable and its structure was modulated by chaotropic agents as expected.

FIGURE 2.

Secondary structure analysis of recombinant PfGrp94. The CD spectrum of PfGrp94 at 25°C (A). The relative folded protein fraction in phosphate buffer at different pH (B) and in the presence of varying amounts of chaotropic agents urea and guanidine HCl (C) monitored at 194, 208, and 222 nm. The folded fraction of PfGrp94 subjected to variable incubation temperature which was raised monotonically from 25°C to 90°C in 5°C increments in the presence and absence of nucleotides or inhibitor NECA (D). The relative folded fraction was determined from the fraction of the ellipticity at 222 nm measured at increasing temperatures compared to that recorded at ambient temperature.

To determine the thermal stability of the recombinant protein, PfGrp94 was suspended in a buffer and subjected to thermal stress by increasing the temperature from 25°C to 90°C and determining the CD spectrum at 5°C intervals (Figure 2D). The CD spectra lost the amplitude of their troughs at 208 and 222 nm, merging to form one trough at 215 nm as the temperature was raised (Figure S2). We monitored the denaturation of the protein at increased temperatures as a fraction of the CD spectra ellipticity at 222 nm compared with that at 25°C to generate the folded fraction using Equation (1). Based on this, PfGrp94 lost 50% of its secondary structure with an increase in temperature above 55°C. This indicated that the protein undergoes heat denaturation as shown by the reduction in the ellipticity at 208 nm, resulting in a melting temperature (T m) of 52.4°C (Figure 2D). To further interrogate the stability of the recombinant protein in the presence of nucleotides, we repeated the experiment and monitored the change in ellipticity as the protein was subjected to an increase in temperature in the presence of either ATP/ADP or NECA. The protein that was subjected to thermal stress in the presence of ADP did not change much from the apo state as its T m was 52.5°C. Interestingly, a protein that was subjected to heat stress in the presence of ATP and NECA showed a significant reduction in the T m to 45.5°C and 38.6°C, respectively (Table 1). This suggests that PfGrp94 undergoes thermal denaturation but is more unstable in the presence of ATP and its mimicking inhibitor.

TABLE 1.

Melting temperatures of PfGrp94.

| Method | T m (°C) ± SD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apo‐protein | ATP | ADP | NECA | |

| DSF | 53.7 ± 0.7 | 53.0 ± 0.3 | 55.0 ± 1.6 | 56.6 ± 1.7* |

| CD | 52.4 ± 0.2 | 45.5 ± 2.1 | 52.5 ± 1.3 | 38.6 ± 2.7* |

Note: Melting temperatures are reported as the mean of three technical repeats performed and the standard deviation of the mean is shown. The difference in T m of PfGrp94 in the presence and absence of NECA was statistically significant (*p < 0.05, ANOVA).

2.3. Analysis of PfGrp94 Tertiary Structure Stability

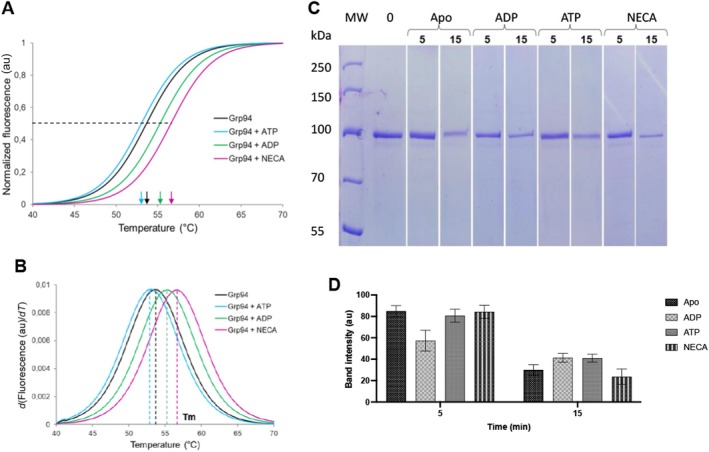

To further investigate the structural stability of the recombinant protein, tertiary structure analysis was conducted using differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF). The data generated were fit to the Boltzmann equation (Equation 2) to give the sigmoidal curves (Figure 3A). The first derivative graphs were obtained using Equation (3), from which melting temperatures (T m) were determined (Figure 3B). The T m of apo‐PfGrp94 was determined to be 53.7°C (Table 1). The experiment was repeated in the presence of ATP and ADP to determine their effects on the stabilization of the protein's tertiary structure when it is subjected to heat stress. In the presence of ATP, PfGrp94 showed a similar T m to that of the apo protein (53.0°C), but incubation with ADP increased the T m to 55.3°C. However, the presence of the inhibitor NECA showed a thermal shift of the T m of PfGrp94 significantly, from 53.7°C to 56.7°C. In contrast, the CD data showed a decrease in T m on PfGrp94 binding to NECA (Table 1). This shows differential structure perturbation between the secondary and tertiary structure of the protein. Taken together, this suggests that the tertiary structure of the recombinant PfGrp94 is not affected by the presence of ATP but is perturbed by ADP and binding to the inhibitor NECA.

FIGURE 3.

Tertiary structure analysis of PfGrp94. The differential scanning fluorimetry melting curves of PfGrp94 in buffer supplemented with 10 μM ATP, ADP, or NECA, as indicated (A) were used to determine the inflection points, which relate to the melting temperatures, are indicated with arrows the corresponding first derivative plots of the sigmoidal melting curves of PfGrp94 (B). The peaks of the curves reflect the melting temperatures. The SDS‐PAGE analysis of PfGrp94 proteolytic degradation (C) and the densitometric analysis of the band intensities (D). Lane MW: molecular weight ladder (kDa), Lane 0: apo‐PfGrp94 without protease, lanes marked 5 and 15 indicate PfGrp94 digested with proteinase K for 5 or 15 min, respectively in the absence (apo‐PfGrp94) and presence of ADP, ATP or NECA, as indicated. The results are representative of three independent repeats and error bars indicate standard deviation.

2.4. Investigation of Protein Conformation and Stability Using Limited Proteolysis

To further investigate the tertiary structure stability of recombinant PfGrp94 limited proteolysis was performed. The recombinant protein was digested with proteinase K in the presence and absence of ATP, ADP, and NECA. Samples collected after 5 and 15 min of treatment were analyzed using SDS‐PAGE and the band intensities were compared to the undigested protein (Figure 3C). The results show that in all cases, the intensity of the PfGrp94 protein band decreased significantly after 15 min of treatment with protease. However, there was a marginal decrease observed in the presence of NECA, suggesting that in this case PfGrp94 was more likely to be in an exposed conformation that was susceptible to proteolytic digestion by proteinase K (Figure 3B).

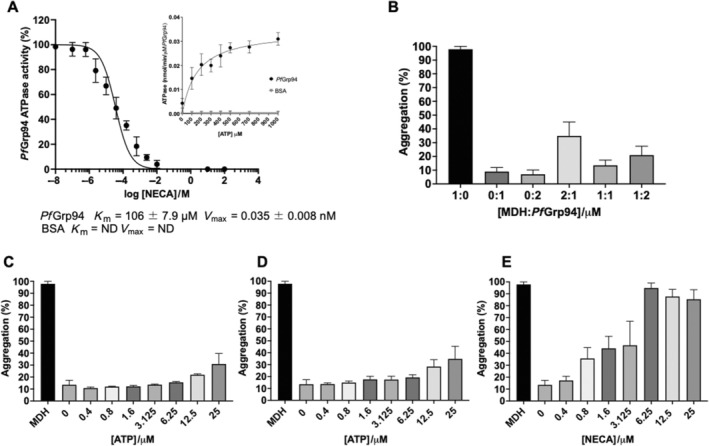

2.5. ATPase Activity of PfGrp94

To determine the basal ATPase activity of recombinant PfGrp94, we conducted a steady‐state ATP hydrolysis activity assay. The recombinant PfGrp94 was observed to hydrolyze ATP at a maximum rate of 0.035 ± 0.008 nmol/min/μM of protein and with a K m of 106 ± 7.9 μM ATP using Michaelis–Menten enzyme kinetics (Figure 4A). This PfGrp94 ATPase activity was also converted to 0.14 ± 0.03 U/L which means the protein requires 0.14 units to catalyze the production of 1 μM of free phosphate per minute. This suggests that PfGrp94 has a faster basal ATP hydrolysis rate when compared to the previously reported Saccharomyces cerevisiae Hsp90 [15]. To determine the inhibitory effect of NECA on the basal ATPase activity of PfGrp94, we subjected the protein to increasing concentrations of the inhibitor. The increase in NECA concentrations was inversely proportional to the ATPase activity of PfGrp94 an EC50 of 3.53 ± 1.5 μM. These findings suggest that NECA abrogated the basal ATP hydrolysis activity of PfGrp94.

FIGURE 4.

Analysis of the chaperone activity of PfGrp94. (A) The dose–response curves for the inhibition of the ATPase activity of PfGrp94 with NECA. (Inset) Michaelis–Menten's analysis of the PfGrp94 basal ATPase hydrolysis rate was determined by a colorimetric malachite green assay. The ATPase activity was calculated in nmol Pi/min/μM of PfGrp94 protein. (B) The suppression of MDH‐aggregation assay in the presence of varying amounts of PfGrp94. The aggregation suppression assay of equimolar MDH and PfGrp94 in the presence of varying amounts of nucleotides ATP (C), ADP (D), and the inhibitor NECA (E), normalized to the aggregation percentage of MDH alone. Error bars represent the standard deviation.

2.6. Malate Dehydrogenase (MDH) Aggregation Suppression Assay

The chaperone function of recombinant PfGrp94 was investigated by its ability to suppress heat‐induced aggregation of MDH. MDH is a heat‐sensitive protein that spontaneously aggregates when exposed to heat stress. The aggregation of MDH suspended in assay buffer following incubation at 48°C was monitored at 360 nm (Figure 4B). To establish that MDH was heat‐labile, we first exposed MDH to heating at 48°C; the resulting aggregation was set as 100%. In contrast, the chaperone protein PfGrp94 did not spontaneously aggregate when exposed to the incubation temperature, which further confirms the heat stability observations made using CD and DSF analyses. As a control, the heat‐induced aggregation of MDH was next performed in the presence of a nonchaperone protein, BSA (Figure S2). This protein could not suppress the aggregation of MDH under the same conditions. However, on titrating different concentrations of chaperone, an equimolar amount of recombinant PfGrp94 suppressed aggregation to just 11% (Figure 4B). To investigate the effect of nucleotides on the aggregation suppression capability of PfGrp94, the reaction mixture was supplemented with varying concentrations of either ATP (Figure 4C) or ADP (Figure 4D). The addition of lower concentrations of either ATP or ADP significantly improved the suppression of aggregation to 10%, but as higher concentrations were increased the suppression ability was marginally reduced in both cases. When the same experiment was performed in the presence of varying concentrations of NECA the aggregation suppression ability of PfGrp94 was abrogated, with aggregation recorded at 35% at 0.8 μM (Figure 4E). At higher concentrations above 1.6 μM NECA, the capability of PfGrp94 to suppress MDH aggregation was significantly reduced and more than 50% of MDH aggregated. This suggests that higher concentrations of NECA abrogate the chaperone function of the PfGrp94 as compared to the nucleotides.

2.7. Modeling of NECA Binding to PfGrp94

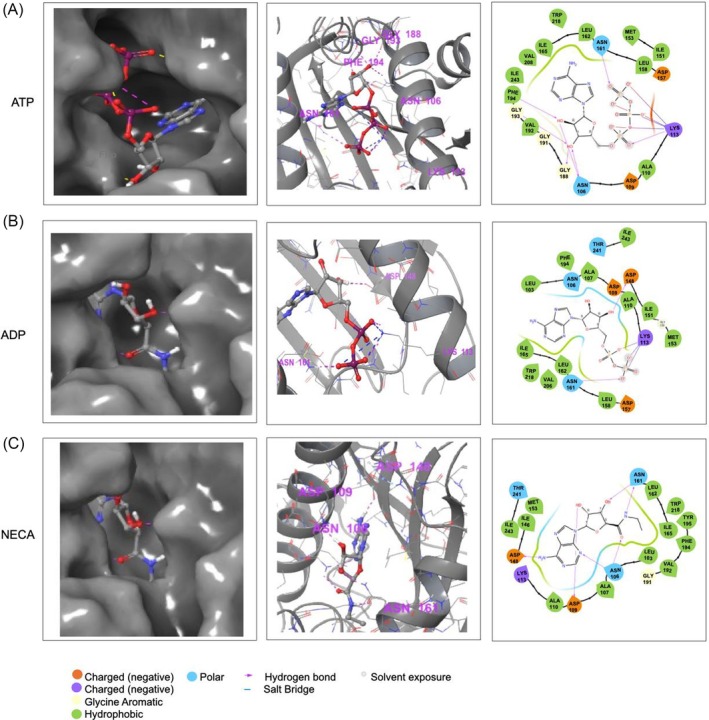

Since we observed that the recombinant PfGrp94 structure and function were perturbed by nucleotides, we further sought to determine the capability of PfGrp94 to bind ATP‐mimicking inhibitors using molecular docking studies (Figure 5). As controls, NECA the model inhibitor was docked into the ATP‐binding pockets of the NTDs of PfGrp94 and the human homologues HsGrp94, HsHsp90α, HsHsp90β, and HsTRAP‐1 (Figure S3). PfGrp94 amino acid residues Asn106, Asp109, Asp148, and Asn161 formed the strongest hydrogen bonds with NECA. As expected, NECA bound to the ATP‐binding pocket Site 3 (Figure 5A) through the unique Asn161 (equivalent to Lys161 in human Grp94 homologues) that forms part of the nucleotide‐binding cavity [13]. The docking scores show that NECA binds to the parasite PfGrp94 with strong affinity since its docking score is the lowest (−8.26 kcal/mol) when compared to its human homologues despite its relatively lower ATP‐binding affinity (Figure 4B and Table 2). The lower docking scores of NECA against human Hsp90 homologues suggest a possible preference toward Grp94 and TRAP‐1 (Figure S3), which has previously been attributed to Site 1 and Site 2 of the ATP‐binding pocket with Site 3 being only accommodated in Hsp90s for conformational changes [13]. This suggests that the propensity of PfGrp94 to bind NECA is attributable to the unique Asn161 which possibly modulates the conformational changes of the ATP‐binding pocket. This identifies NECA as a possible ATP‐mimicking inhibitor that may bind to PfGrp94 abrogating its function.

FIGURE 5.

The predicted docking poses for NECA binding on PfGrp94 and Hsp90 NTDs. The 3D binding pocket and 2D representation of the interacting residues of PfGrp94 with nucleotides (A) ATP, (B) ADP, and (C) NECA within a distance of less than 4 Å stabilizing the complex, as predicted using Schrödinger Maestro 2022.1.

TABLE 2.

The predicted comparative ATP/ADP and NECA binding affinities in Hsp90 NTDs.

| Ligand | Docking score (kcal/mol) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PfGrp94 | HsGrp94 | HsHsp90α | HsHsp90β | HsTrap‐1 | |

| ATP | −7.87 | −7.50 | −8.88 | −6.30 | −6.50 |

| ADP | −8.65 | −7.84 | −9.83 | −9.74 | −9.35 |

| NECA | −8.26 | −7.44 | −6.62 | −6.76 | −7.94 |

2.8. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations

The stability of the PfGrp94‐NECA complex and its dynamic behavior were investigated further in MD studies by modeling the molecular system integrating Newton's equation of motion [16]. The apo‐PfGrp94 was initially simulated, followed by the complex with NECA to assess the stability of PfGrp94 upon ligand binding. A simulation period of 250 ns was used. We validated our results using the simulation quality analysis technique in Desmond and no changes in temperature, energy, pressure, or volume were recorded over the simulation period (Table S2 and Figure S4).

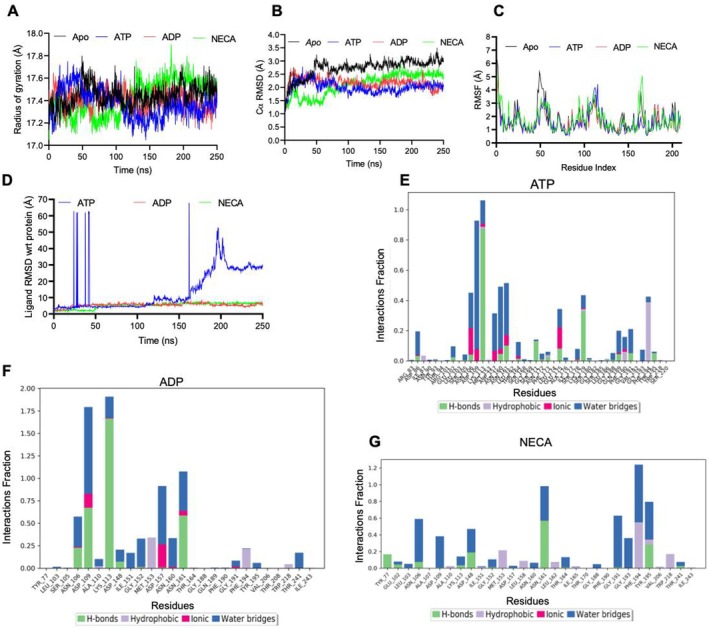

The radius of gyration (R g) assesses the protein's compactness during simulation. A low R g value implies a compact protein structure, whereas a high R g value indicates a less compact protein structure [17]. The mean R g (± SD) of Cα of apo‐PfGrp94 was 17.44 ± 0.10 Å, for ATP was 17.37 ± 0.13 Å for ADP was 17.41 ± 0.09 Å and NECA‐PfGrp94 was 17.42 ± 0.10 Å respectively (Table S3). The R g profile demonstrates that apo‐PfGrp94 and nucleotides or NECA‐PfGrp94 are comparable since there was no significant variation from the mean R g (Figure 6A). Since the profile of apo‐PfGrp94, ATP‐PfGrp94, ADP‐PfGrp94, and NECA‐PfGrp94 are similar, this suggests that when NECA is in complex with PfGrp94, the degree of conformational change is minimal, resulting in a less compact structure during the simulation period. The more compact a protein becomes, the less likely it is that the drug molecule has significantly interfered with the protein's mechanism for folding [18]. Therefore, the results indicate that the binding of NECA significantly affects the structure of PfGrp94, which validated our recombinant PfGrp94 tertiary structure observation from CD, DSF, and limited proteolysis analyses.

FIGURE 6.

NECA forms stable interactions with PfGrp94 during MD simulation. (A) The R g of PfGrp94 Cα atoms. (B) The RMSD plot of apo‐PfGrp94 Cα atoms and with nucleotides or NECA over a simulation period of 250 ns. (C) Protein RMSF of apo‐PfGrp94 and in complex with nucleotides or NECA. (D) The ligand RMSD graph showing the stability of the NECA or nucleotides with respect to the PfGrp94 binding site. PfGrp94 amino acid residues that interact with the ligand (E) ATP, (F) ADP, and (G) NECA which are marked with green‐colored vertical bars; H‐bonds are categorized into backbone acceptor; backbone donor; side‐chain acceptor; side‐chain donor. Hydrophobic interactions are categorized into π–cation; π–π*; and other, nonspecific interactions. The stacked bar charts are normalized throughout the 250 ns trajectory. The images were generated from Maestro v13.1.

During the simulation run, the protein RMSD provides information on the protein's structural dynamics (Figure 6B). The root mean square deviation (RMSD) (± SD) of Cα of apo‐PfGrp94 was 2.73 ± 0.35 Å, ATP‐PfGrp94 was 2.01 ± 0.22 Å, ADP‐PfGrp94 was 2.17 ± 0.21 Å and NECA‐PfGrp94 was 2.11 ± 0.42 Å respectively (Table S4). All the systems did not fluctuate over 3 Å, which confirms the conclusions of the simulation quality analysis above as previously shown in the human Grp94 [13]. When a ligand binds to a protein, the structure's mobility will be predicted to decrease due to the ligand's interaction with the binding cavity. This would imply that the apo form of the protein has the most conformational dynamics and the ATP‐bound state with the least conformational movements. As expected, the complex formed between NECA‐PfGrp94 and ADP‐PfGrp94 showed RMSDs value slightly lower than that of apo‐PfGrp94 with a difference of 0.62 and 0.56 Å (Figure 6B). This suggests that the apo form of PfGrp94 and the ATP‐bound form both have similar conformational dynamics which are stable, in contrast to ADP and NECA‐bound forms which are unstable.

The root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) analysis of the PfGrp94 NTD side chains after ligand binding during the MD simulation reveals information on protein residue flexibility. A larger RMSF value suggests a higher degree of motion, whereas a low RMSF value indicates a stable structure with less motion [18]. The RMSF profiles of the apo protein and the complexes with nucleotides and NECA, calculated based on the residues index Cα show that PfGrp94 NTD fluctuates extensively in two regions: Residues 44–55 in the flexible looping region between the second and third helix, and Residues 110–120 in the fourth helix (Figures 6C and S4). NECA does not bind to these fluctuating regions, but they allow access to Site 2 binding promoting Grp94 isoform selectivity [13, 19]. Therefore, the results indicate that the structure of PfGrp94 is significantly affected by the binding of NECA. The RMSD of a ligand reflects how stable it is in relation to the protein binding pocket. Furthermore, the degree of motion for NECA was found to be steady throughout the 250 ns simulation period (Figure 6D). Throughout the 250 ns simulation, ligand snapshots demonstrate that NECA was stable and maintained its position, like ADP which indicated stability (Figure S4). However, the ATP ligand RMSD fluctuated mostly in the first 50 ns and stabilized in the 50–150 ns and started to fluctuate again from 150 ns and drifting up to 250 ns. This may suggest the potential destabilization of ATP as it undergoes hydrolysis in the fGrp94 active site. Assessment of the type of protein–ligand intermolecular interactions during the duration of the MD simulation, we observed hydrogen interactions, hydrophobic contacts, ionic interactions, and water bridges (Figure 6E–G). These different forms of bonding contribute to the ligand–protein complex's overall stability and selectivity. The interaction fractions of NECA were 1.2, ADP was 1.8 and ATP was 1.1 indicating a high number of interactions with the PfGrp94 residues among all the ligands. The contact was mostly stabilized via hydrogen bond interaction and water bridges, which are strong bonds that play an important role in the formation of robust and stable protein–ligand complexes further validating the docking results. It was observed that ATP interacted with unique residues forming hydrogen bonds with Lys113, Asn161, Ser 171, and Lys179. The hydrophobic bonds were formed with Phe194 and Ile87 and ionic bonds with Asn106Asp109Asp157 and Glu175 and lastly water bridges with Asp86, Asn106, Asp109, Asp157, Asn160, Asn161, Gln 189, Phe190, and Gly191 (Figure 6E). On the other hand, ADP formed hydrogen bonds with residues Asn106, Asp109, Lys113, and Asn161, together with hydrophobic bonds with Met153 and Phe194 and ionic bonds with Asp109, Asp157 and Asn161. In addition, there were water bridges between ADP and PfGrp94 NTD at Asn106, Asp109, Gly151, Asp157, Asn160, Asn161, and Thr24 (Figure 6F). Similarly, residues Asp 148, Asn161, and Tyr 195 contributed to hydrogen bond formation with NECA and Asn106, Asp148Asn161, and Gly191 formed water bridges (Figure 6F). In addition, the residues Phe194, Val206, and Try218 formed hydrophobic bonds and ionic bonds were formed by Asn161 and Asn106 to stabilize the protein–NECA interaction during the simulation time. Although ATP had more interacting residues across all four different interactions with the protein, the interaction fractions with these residues were lower when compared to that for ADP and NECA with fewer interactions. This suggests that the interaction of PfGrp94 with ATP had several stabilization bonds while ADP/NECA had fewer stronger bonds in their interactions with the protein site. This shows that NECA exhibited substantial interactions with the amino acids inside the active region during the simulation time (Figure S5).

2.9. Antiplasmodial Activity of NECA

We next investigated the ability of NECA to inhibit the proliferation of P. falciparum chloroquine‐sensitive and chloroquine‐resistant parasites at the asexual blood stage. The antiplasmodial activity of NECA was compared to that of chloroquine and artesunate which are known antimalarial drugs (Table 3). In addition, the known Hsp90 inhibitor geldanamycin (GA) was used as a control [20]. The PfGrp94 inhibitor, NECA showed moderate activity against the isolates of P. falciparum with a half‐maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 7.34 ± 0.37 μM in NF54, 4.24 ± 1.46 μM in K1, and 10 ± 1.2 μM in Dd2 strains, respectively. Similarly, GA exhibited moderate growth inhibition profiles. However, in contrast, both chloroquine and artesunate were extremely active against NF54 with IC50 of 10.4 ± 0.5 and < 0.5 ± 0.01 nM, which were within expected ranges [21]. The K1 and Dd2 IC50 values for chloroquine were also within the typically reported ranges with an increase in the value of chloroquine as both strains are resistant to chloroquine with IC50 values of 0.26 ± 0.023 and 0.194 ± 0.011 μM (Table 3). Taken together, NECA exhibited mild antiplasmodial activity.

TABLE 3.

Antiplasmodial activity of NECA.

| Mean IC50 (μM) (IC50 ± SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| NF54 | K1 | Dd2 | |

| NECA | 7.34 ± 0.39 | 4.24 ± 1.46 | 10.0 ± 1.2 |

| Geldanamycin | 4.11 ± 1.24 | 4.35 ± 0.26 | ND |

| Chloroquine | 0.01 ± 0.005 | 0.26 ± 0.023 | 0.194 ± 0.011 |

| Artesunate | < 0.005 ± 0.0001 | < 0.005 ± 0.0001 | < 0.005 ± 0.001 |

Note: Data shown are the mean of three technical repeats and standard deviation is shown.

Abbreviation: ND, not determined.

3. Discussion

Parasite Hsp90s have been an attractive novel antimalarial drug candidate [22], which has led to efforts to identify and repurpose isotype/paralogue Hsp90 selective drugs [9]. NECA has been proposed as a Grp94 selective inhibitor in human homologues, which offers promise for its repurposing as a potential antimalarial drug. Previously, NECA was shown to bind to the Grp94 NTD in the ATP‐binding pocket [13]. This study sought to overexpress and characterize the parasite PfGrp94 protein as a potential druggable candidate. This study is the first to provide direct evidence for the successful expression and purification of the full‐length PfGrp94 proteins (Figure 1). In addition, we demonstrated that NECA perturbs the PfGrp94 structural conformation and abrogates its chaperone function. Using the recombinant full‐length PfGrp94 recombinant protein, we observed that the protein was thermally stable, similar to other cytosolic Hsp70 and Hsp90 plasmodial chaperones [23, 24]. Similarly, the tertiary structure analysis using DSF showed PfGrp94 with a T m at 53.7°C. The presence of nucleotides did not significantly change the melting temperatures of PfGrp94 proteins, but the presence of NECA significantly increased the T m to 56.6°C when compared to the apo‐protein (Figure 2). This suggests that NECA binds to the protein as shown by the thermal shift of the protein to higher temperatures. Similarly, the secondary structure thermal stability of PfGrp94 was perturbed by the presence of NECA making the protein less stable. This suggests that the contrasting effects of NECA on the tertiary and secondary structure thermal stability effect may be due to different effects on the secondary structure and the conformation of the tertiary structure. The ATP‐bound state of the protein is known to be more compact as the chaperone protein functional homodimer covers the substrate Minami et al. [25]. It is possible that the same mechanism is observed in the presence of NECA. In contrast, despite the low sensitivity of the limited proteolysis assay, we observed that the protein was in a more proteolytically labile conformation in the presence of ATP and NECA but less so in the presence of ADP or the absence of nucleotides. These contrasting results point to differences in functional exposure of the protein in the limited proteolysis which may make it partially unfolded and thermally stable but have more proteinase K cleavage sites exposed.

Using in silico studies, we previously reported that PfGrp94 is a druggable molecule that can be selectively targeted [26]. In this study, we conducted molecular docking and MD studies and observed that NECA preferentially binds to PfGrp94 compared to its human homologues. This was in line with a previous report that NECA is selective for Grp94 proteins [13]. In silico data suggested that NECA binds to unique residues in the PfGrp94 NTD ATP‐binding pocket and forms stable interactions (Figure 5). The selectivity of NECA against ER resident Grp94 over their cytosolic homologues is based on the flexibility of Helixes 4 and 5 of the NTD. In PfGrp94, these helices were shown to be flexible and did not directly bind to NECA but were possibly flexible enough to allow its entry and access to Site 3 (Figure 5). Considering that the interdomain functional dynamics include allostery between the NTD and the MD of Grp94 [10, 27], we probed the full‐length effect of NECA on the global function of the protein as a chaperone. PfGrp94 was capable of hydrolyzing ATP, however, the addition of 3.53 μM NECA was effective to inhibit 50% of the basal ATPase activity. Similarly, using the heat‐labile model substrate/client, MDH, the presence of 3.12 μM NECA inhibited half of the chaperone function of PfGrp94 (Figure 4). Equimolar PfGrp94 significantly suppressed the MDH aggregation over time, with this ability being slightly increased in the presence of ADP and much more increased in the presence of ATP. The chaperone cycle of Gpr94 is enhanced in the presence of ATP, and PfGpr94 is dependent on ATP for efficient client refolding. Thus, NECA binds in the ATP‐binding pocket causing conformational changes to PfGrp94 that traps the client protein in the ATP‐bound closed dimer state, such that it cannot release a refolded substrate and is unavailable to refold any additional substrates. These functions could be inferred using full‐length PfGrp94 in addition to the findings from the truncated PfGrp94 NTDs [12].

We further established that NECA had moderate growth inhibition activity against three P. falciparum strains, the NF54 clinical isolate that is sensitive to chloroquine, and the K1 and Dd2 strains that are chloroquine‐resistant (Table 3). Interestingly, NECA was marginally more active against the K1 chloroquine‐resistant strain. The inhibition of PfGrp94 may account for the antiplasmodial activity observed for NECA. It has been suggested that about 400 parasite proteins are processed in the ER for export, of these 71 were confirmed to be essential for parasite growth at the asexual blood stage [28]. This partly explains the essential role of the ER‐resident PfGrp94 in parasite survival and development during the red blood stages. The findings of our current study demonstrate that PfGrp94 exhibits chaperone function and is thermally resilient. Moreover, NECA was predicted to bind PfGrp94 through the NTD domain making it important for further scaffold to design selective antimalarial inhibitors that target its chaperone function in the ER. Since NECA has been shown to be selective for human Grp94, its activity against the parasite PfGrp94 was shown in this study using both biochemical and predictive tools. Future efforts must focus on solving the full‐length three‐dimensional (3D) solution structure of PfGrp94 in comparison with its homologues to unravel the unique structural intricacies that dictate its function. A direct binding kinetics assay of the protein–ligand complexes would further provide support for the druggability of PfGrp94 as a target in efforts to develop new malaria drugs.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Materials

Unless otherwise stated, the materials used in this study were procured from Merck Millipore, Sigma‐Aldrich, and Thermo Scientific (MA, USA). The following antibodies were used: goat anti‐rabbit HRP conjugated (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA).

4.2. Generation of the PfGrp94‐Coding Plasmid Construct

The amino acid sequence of PfGrp94 was retrieved from PlasmoDB (accession number: PF3D7_1222300) in fasta format toward the design of the plasmid construct. The N‐terminal protein secretion signal (amino acid Residues 1–21) was removed and the sequence was submitted to GenScript (NJ, USA) for codon optimization and synthesis. The construct was cloned into a pQE30 vector between the restriction sites BamHI and HindIII to generate the pQE30‐PfGrp94 plasmid. The plasmid construct integrity was verified through DNA sequencing and diagnostic restriction digest.

4.3. Expression and Purification of PfGrp94

The pQE30‐PfGrp94 plasmid construct coding for the recombinant PfGrp94 protein was used to transform chemically competent E. coli XL1‐Blue cells. The transformed cells were grown in Luria broth (LB) media (supplemented with 100 μg/mL ampicillin) and recombinant protein overexpression was induced by the addition of 1 mM IPTG and incubated overnight at 16°C with shaking. After overnight incubation, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10 000 × g using an Avanti J‐E centrifuge (Beckman Coulter, CA, USA) for 20 min at 4°C, and the resulting cell pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM PMSF) supplemented with 0.1 mg/mL lysozyme. Subsequently, the cells were lysed by sonication using the W‐385 Sonicator Ultrasonic Processor + C3 20 kHz Converter probe (Heat Systems Ultrasonics Inc., NY, USA), by alternating 60 s ON pulses and 5 min OFF pauses at a 50% amplitude which was repeated six times. The total cell lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 20 000 × g for 40 min at 4°C and the supernatant was filtered at 0.45 μm acrylic single‐use syringe filter.

The PfGrp94 protein was purified from the E. coli lysate using IMAC (HiPrep IMAC FF 16/10 and HiTrap IMAC FF chromatography columns, Cytiva, USA, MA) using the ÄKTA Start Fast Protein Liquid Chromatography (FPLC) system (Cytiva, MA, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the nickel‐charged agarose resin was prepared and equilibrated with binding buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 5 mM imidazole, and 500 mM NaCl). The filtered, soluble total cell lysate fraction was applied to the chromatography column, and unbound proteins were washed using the binding buffer supplemented with 20 mM imidazole. The recombinant His‐tagged proteins were eluted using 500 mM imidazole. The purified PfGrp94 recombinant protein from IMAC was further cleaned using the HiTrap Q HP anion exchange chromatography (AEC) column (Cytiva, MA, USA). The protein expression and purity of the recombinant proteins were analyzed by SDS‐PAGE.

4.4. PfGrp94 Polyclonal Antibody Production

The polyclonal antibodies against the PfGrp94 were produced by immunizing rabbits using a previously described protocol [29]. Briefly, the recombinantly purified PfGrp94 protein was adsorbed to trinitrophenylated acid treated—naked Salmonella minnesota R595 (NB) bacterial cells in a ratio of 1:5 (200 μg PfGrp94 to 1000 μg NP) in PBS (pH 7.2). The reaction mixture was incubated at 25°C with gentle rotation and washed with PBS and distilled H2O before drying with a rotary evaporation Savant SpeedVac (Thermo‐Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). The PfGrp94‐NB conjugates were resuspended in PBS and used to immunize female Flemish giant rabbits at 6 months of age obtained from custom antibody synthesis (Faculty of Science Small Animal Research Facility, Stellenbosch University, SA) with ethical clearance granted by the Animal Ethics Committee of Stellenbosch University (protocol number SU‐ACU‐2020‐14892). The preimmunization sera were collected on Day 0 and the antigen mixture of 40 μg PfGrp94–200 μg NB in 0.5 mL PBS was injected intravenously in the marginal ear vein of the rabbits after EMLA (AstraZeneca, Cambridge, UK) local anesthetic cream application. After the immunization process, 20 mL of blood was drawn on Day 42 from the central auricular artery and allowed to coagulate overnight at 4°C before centrifugation at 800 × g for 20 min. The separated antisera (PfGrp94 antibody) were used for Western blot to confirm the expression and purification of recombinant PfGrp94. Another ER‐localized chaperone, PfGrp170 recombinant protein was used as a control for antibody specificity. Further antibody validation was conducted using mixed P. falciparum 3D7 parasite cell lysate.

4.5. Investigation of PfGrp94 Secondary Structure Stability

The secondary structural features of the recombinant PfGrp94 protein were investigated using CD spectroscopy as previously described [30]. Briefly, 0.15 μM PfGrp94 suspended in CD buffer (10 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.5, and 100 mM KF) was exposed to far UV light and the spectrum was monitored between 185 and 260 nm using a Chirascan plus CD instrument (Applied Photophysics, MA, USA). A quartz cuvette with a path length of 1.0 mm (Hellma Analytics, Germany) was used for the determination of the CD spectra at 25°C. The spectrum recorded was an average of seven spectra collected after the baseline spectrum of the buffer (buffer without protein) was subtracted each time, and the experiments were repeated three times. The CD spectra were deconvoluted using the Dichroweb server (http://dichroweb.cryst.bbk.ac.uk/html/home.shtml) into secondary structure elements α‐helixes, β‐sheets, β‐turns, and unordered regions with the reference set 7 using the CONTIN‐LL analysis program [31]. The CD spectroscopy results were validated by comparison to in silico predicted AlphaFold structures (https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/), using the accession number: AF‐Q8I0V4‐F1 [32]. The effects of MgCl2 and CaCl2 on the secondary structure spectrum were investigated by repeating the experiment in CD buffer comprising 100 mM MgCl2/CaCl2 in place of 100 mM KF and data processed as previously described.

To investigate the effect of pH on the secondary structure stability of recombinant PfGrp94, the protein was suspended in 10 mM KH2PO4, and 100 mM KF at varying pH 2–10. The CD spectra were used to monitor the change in molar residue ellipticity as the pH was changed. In addition, the protein was exposed to varying concentrations of chaotropic agents 0–6 M urea/guanidine HCl. The resultant spectra were used to monitor the resilience of the protein to withstand chemical denaturation. The molar residue ellipticity at any given condition was compared to the spectra at native buffer conditions to generate the folded protein fraction calculated as in Equation (1) as previously described [24]. Furthermore, the secondary structure thermal resilience profile of PfGrp94 was investigated using CD spectroscopy as previously described [24]. Briefly, the recombinant protein suspended in CD buffer was subjected to thermal stress as the buffer temperature was raised from 25°C to 90°C at a rate of 1°C/min. The CD spectra were measured every 5 min over the same wavelength range of 185–260 nm. To determine the refolding capability of PfGrp94 to gain its initial secondary structure fold, the experiment was repeated with different aliquots of protein exposed to stepped maximum temperatures ranging from 25°C to 90°C at every 5°C interval and allowed to cool down to 25°C while recording the spectra. The resulting data measured at 194, 208, and 222 nm were used to monitor the change in molar residue ellipticity as the temperature was changed to generate a folded fraction (Equation 1) as previously described [24].

| (1) |

where [θ]t is the molar ellipticity at the specific temperature, [θ]h at the highest temperature, and [θ]l at the lowest temperature, respectively. The highest and lowest temperature values were replaced with those of highest and lowest pH and urea/guanidine–HCl concentrations to determine the folded fractions using the same Equation (1).

4.6. DSF

The thermal stability of the tertiary structure of PfGrp94 was investigated using DSF as previously described [33]. Briefly, 4 μM of PfGrp94 in Tris buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, and 200 mM NaCl) was incubated for 10 min at 25°C with 40 μM SYPRO Orange Protein Gel Stain dye (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA). The mixed reactions were transferred to a Magnetic Induction Cycler (MicPCR, Bio Molecular Systems, Australia) and the incubation temperature was raised from 40°C to 95°C at a rate of 0.2°C/s while monitoring the fluorescence emission signal at 570 nm. To investigate the effects of nucleotides and inhibitors on protein stability the experiment was repeated in the presence of 10 μM ADP or ATP or inhibitor NECA. Baseline signals of Tris buffer with ATP/ADP/NECA + SYPRO Orange dye were subtracted from the recorded signals of protein. All experiments were repeated three times each in triplicate, where the final melting curves represent the means of all the data. Data was processed according to the method previously described [34] and fit to the Boltzmann equation (Equation 2) using nonlinear regression (Equation 3) to determine the inflection point (T m) of the protein. The first derivative of the normalized fluorescence was also calculated using Equation (3), to determine the peak thermal shift using GraphPad Prism v10.1.0 (GraphPad Software, CA, USA).

| (2) |

| (3) |

“Bottom” is the lowest value of the melting curve, “Top” is the peak melting curve value, and T m is the inflection point (°C).

4.7. Partial Proteinase K Proteolysis

The PfGrp94 conformational stability was investigated using partial proteolysis as previously described [24]. Briefly, 0.3 μM PfGrp94 was suspended in KP buffer (20 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM CaCl2, and 5 mM DTT) and allowed to stand for 5 min. Proteolysis was initiated by the addition of 0.05 μM proteinase K (Sigma‐Aldrich, USA) and incubated at 25°C. During the assay, 16 μL samples were collected at 5 and 15 min time points after mixing to minimize sample variability. The proteolytic digestion of the samples was stopped by the addition of the 4 μL of 5× stop solution (1 mM PMSF, 5% SDS, and 0.1% β‐mercaptoethanol) and immediately boiled at 95°C for 5 min before storage and subsequently analyzed by SDS‐PAGE. In order to determine the effect of nucleotides and inhibitors on the conformation of PfGrp94, the experiment was repeated in the presence of 10 μM ADP, ATP, or NECA. The band intensities were estimated from the gel images using ImageJ (https://imagej.net/).

4.8. Analysis of the Basal ATPase Activity of PfGrp94

The basal ATPase activity PfGrp94 was investigated using a colorimetric assay as previously described [24]. Briefly, 0.8 μM of the PfGrp94 suspended in HKMD buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, and 0.5 mM DTT) was mixed with varying concentrations of ATP from 0 to 1000 μM and incubated for 60 min at 30°C. As a nonchaperone control, 0.8 μM BSA was used. The absorbance in each well after the addition of malachite green for color development was measured at 660 nm using a Multiskan Sky Microplate Spectrophotometer (Thermo‐Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). To determine the effect of the inhibitor on the basal ATPase activity of PfGrp94, the assay was repeated in the presence of varying concentrations of (0–200 mM) NECA. Data were analyzed after baseline subtraction of buffer with protein in the absence of ATP. The assay was repeated three times to determine the mean and standard deviation used to plot the Michaelis–Menten curve to determine the enzyme kinetics. The dose–response curve for the nonlinear fit of the normalized activity of PfGrp94 against the log concentration of NECA was used to calculate the EC50 using GraphPad Prism software v10.1.0 (GraphPad Software, CA, USA).

4.9. Investigation of PfGrp94 Chaperone Function

The chaperone function of PfGrp94 was investigated using the MDH aggregation suppression assay as previously described [35]. Briefly, 2 μM of PfGrp94 in assay buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, and 5 mM MgCl2) was mixed with 1 μM of the model substrate, MDH from the porcine heart (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) and allowed to incubate at 25°C for 15 min. The reaction was initiated by increasing the incubation temperature to 48°C. The absorbance of the reaction mixture at 360 nm was recorded every 10 min for 150 min using a Multiskan Sky Microplate Spectrophotometer (Thermo‐Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). To investigate the effects of nucleotides and inhibitors on the proteins' chaperone activities, the experiment was repeated in the presence of 0–25 μM ATP/ADP/NECA. All data were normalized to the aggregation of MDH in the absence of any chaperone protein, which was set to 100% aggregation.

4.10. Growth Inhibition Studies

The investigation of the effect of NECA on the growth of asexual P. falciparum parasites was conducted as previously described [36] with the approval of the Stellenbosch University Health Research Ethics Committee (Ref # X21/09/032). Briefly, two parasite strains, drug‐sensitive strain NF54 and the multidrug‐resistant strain K1, were cultured at 1% parasitemia in 1% RBC hematocrit suspended in RPMI complete media supplemented with 25 mM HEPES, 11 mM glucose, 200 μM hypoxanthine (dissolved in 500 mM NaOH), 24 μg/mL gentamycin and 0.6% m/v Albumax II serum. The parasite culture was subjected to increasing concentrations of NECA (from 1.95 to 500 μM) and incubated at 37°C in a continuous gas environment (93% N2, 3% O2, and 4% CO2) for 96 h. As positive control, chloroquine and artesunate were tested starting at 1 μg/mL. The parasite culture without any added compound was used as negative drug control. The solvent (0.5% DMSO) had no measurable effect on parasite viability. The proliferation of parasites was measured after the addition of 100 μL Malstat reagent and 25 μL nitroblue tetrazolium solution. The color development was quantified at 620 nm. The data were analyzed using SigmaPlot, version 12 (Systat Software Inc., IL, USA) to generate dose–response curves to determine the IC50 from three technical repeats.

4.11. Molecular Docking

Molecular docking was used to study the selective binding mechanism of the Hsp90 NTD and NECA as previously described [26, 37] using the Schrödinger Maestro software v2022‐1. The re‐refined and validated Hsp90 NTD crystal structures were retrieved from the PDB‐REDO web server for PfHsp94 (3PEH). As controls, the human homologies HsHsp90α (1BYQ), HsHsp90β (3NMQ), HsGrp94 (4NH9), and HsTRAP‐1 (7C04) were prepared by using the Protein Preparation Wizard module. This generated 3D structures that were energy‐minimized and structurally correct by adding missing hydrogen atoms and assigning partial charges. Bond orders were assigned to all atoms and hydrogens in the protein structure, as well as the disulfide bond. The pH of the het states generated by Epik was adjusted to 7.0 ± 2.0. At a pH of 7.0, the hydrogen bonding assignment was set to sample water orientations and then optimized using the PROPKA tool. Waters over 3.0 Å were eliminated, and heavy atoms were converged to a RMSD of 0.3 Å. The force field was set to Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulations 2005 (OPLS_2005). NECA (PubChem accession: 448222) as a ligand was docked into the ATP/ADP binding pocket of the respective Hsp90 NTDs. The box size was designed to dock ligands with a length of 46 Å or less. The constraints settings remained unaltered, and the sample ring conformations were set to an energy window of 2.5 kcal/mol for the ligand parameters. The following settings were used for Glide docking receptor scaling: receptor van der Waals (0.50), ligand van der Waals (0.50), and a maximum number of poses (20). The default prime refinement setting was configured to refine residues within 4.0 Å of ligand positions and optimize side chains. The parameters for glide redocking were set to redock into structures that were within 10.0 kcal/mol of the best structure and within the top 20 structures. The precision was set to standard protocol, with a Glide and Prime CPU count of two.

4.12. MD Simulations

The initial step in the MD simulations was to use the system builder function on the Desmond module of the Schrödinger suite 2022‐1, as previously described [38] to solvate the energy‐minimized docked complex. The TIP3P solvent parameter was employed, and the boundary conditions were stated as a cubic box with a volume that was kept to a minimum of 10 Å. The force field was set to OPLS_2005, and the system was neutralized by introducing Cl or Na ions dependent on total charges, with the salt concentration set to 0.15 M. The MD simulations of the 3D structure of the PfGrp94 NTD and PfGrp94 NTD‐ligand complexes were carried out using a computer with a Linux server containing the 2019 GPU‐enabled Schrödinger Desmond version. For Desmond MD simulation investigations, a GPU‐enabled MD simulation engine implemented in Maestro v12.2 was utilized on a Linux (Ubuntu) desktop server. In all runs, the ensemble class was set to NPT with a bar pressure of 1 bar and a temperature of 300 K. The simulation length was set to 250 ns, and the model system was configured to relax before simulation at the OPLS_2005 force field. The Simulation Interaction Diagram tool from the Desmond MD package was used to do a post‐dynamic study of the protein–ligand interaction. The protein–ligand RMSD, protein–ligand RMSF, radius gyration, and the MD simulation stability were all examined.

4.13. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated three times unless otherwise stated. One‐way ANOVA and Student's t‐test testing were performed using GraphPad Prism v10.02 (GraphPad Software, CA, USA) to determine the statistical significance at p < 0.05.

Author Contributions

Florence Lisa Muzenda: investigation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, formal analysis, software, data curation, visualization, validation, methodology. Melissa Louise Stofberg: investigation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, visualization, methodology, formal analysis, data curation. Wendy Mthembu: investigation, methodology, writing – review and editing. Ikechukwu Achilonu: software, resources. Erick Strauss: writing – review and editing, supervision, validation. Tawanda Zininga: conceptualization, investigation, funding acquisition, visualization, formal analysis, project administration, resources, supervision, data curation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Peer Review

The peer review history for this article is available at https://www.webofscience.com/api/gateway/wos/peer‐review/10.1002/prot.26779.

Supporting information

Data S1. Supporting Information.

Table S3. PfGrp94 in complex with ADP/ADP/NECA and in its Apo state of the radius of gyration values.

Table S4. PfGrp94 in complex with ADP/ADP/NECA and in its Apo state of the RMSD values.

Acknowledgments

T.Z. is a recipient of a Georg Foster and Carl Friedrich von Siemens Research Fellowship awarded by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, Germany. The authors are grateful to the Department of Science and Technology/National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Africa for research grants (Grant numbers 129401, 145405, and CPRR23032387146) awarded to T.Z. The authors would like to thank the H3D Drug Discovery and Development Centre (University of Cape Town) for antimalarial testing.

Funding: This work was supported by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, Germany and the Department of Science and Technology/National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Africa (grant numbers 129401, 145405, and CPRR23032387146), awarded to T.Z.

References

- 1. Tilley L., Dixon M. W., and Kirk K., “The Plasmodium falciparum‐Infected Red Blood Cell,” International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 43, no. 6 (2011): 839–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Florentin A., Cobb D. W., Kudyba H. M., and Muralidharan V., “Directing Traffic: Chaperone‐Mediated Protein Transport in Malaria Parasites,” Cellular Microbiology 22, no. 7 (2020): e13215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Oikonomou C. and Hendershot L. M., “Disposing of Misfolded ER Proteins: A Troubled substrate's Way out of the ER,” Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 500 (2020): 110630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Richter K., Haslbeck M., and Buchner J., “The Heat Shock Response: Life on the Verge of Death,” Molecular Cell 40, no. 2 (2010): 253–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bhattacharjee S., Coppens I., Mbengue A., et al., “Remodeling of the Malaria Parasite and Host Human Red Cell by Vesicle Amplification That Induces Artemisinin Resistance,” Blood 131, no. 11 (2018): 1234–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hetz C., Zhang K., and Kaufman R. J., “Mechanisms, Regulation and Functions of the Unfolded Protein Response,” Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 21, no. 8 (2020): 421–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rathore S., Datta G., Kaur I., Malhotra P., and Mohmmed A., “Disruption of Cellular Homeostasis Induces Organelle Stress and Triggers Apoptosis Like Cell‐Death Pathways in Malaria Parasite,” Cell Death and Disease 6, no. 7 (2015): e1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dollins D. E., Warren J. J., Immormino R. M., and Gewirth D. T., “Structures of GRP94‐Nucleotide Complexes Reveal Mechanistic Differences Between the hsp90 Chaperones,” Molecular Cell 28, no. 1 (2007): 41–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stofberg M. L., Caillet C., de Villiers M., and Zininga T., “Inhibitors of the Plasmodium falciparum Hsp90 Towards Selective Antimalarial Drug Design: The Past, Present and Future,” Cells 10, no. 11 (2021): 2849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rosser M. F. and Nicchitta C. V., “Ligand Interactions in the Adenosine Nucleotide‐Binding Domain of the Hsp90 Chaperone, GRP94: I. Evidence for Allosteric Regulation of Ligand Binding,” Journal of Biological Chemistry 275, no. 30 (2000): 22798–22805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Newstead S. and Barr F., “Molecular Basis for KDEL‐Mediated Retrieval of Escaped ER‐Resident Proteins—SWEET Talking the COPs,” Journal of Cell Science 133, no. 19 (2020): jcs250100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Murillo‐Solano C., Dong C., Sanchez C. G., and Pizarro J. C., “Identification and Characterization of the Antiplasmodial Activity of Hsp90 Inhibitors,” Malaria Journal 16 (2017): 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huck J. D., Que N. L., Immormino R. M., et al., “NECA Derivatives Exploit the Paralog‐Specific Properties of the Site 3 Side Pocket of Grp94, the Endoplasmic Reticulum Hsp90,” Journal of Biological Chemistry 294, no. 44 (2019): 16010–16019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tosh D. K., Brackett C. M., Jung Y. H., et al., “Biological Evaluation of 5′‐(N‐Ethylcarboxamido) Adenosine Analogues as Grp94‐Selective Inhibitors,” ACS Medicinal Chemistry Letters 12, no. 3 (2021): 373–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Young J. C. and Hartl F. U., “Polypeptide Release by Hsp90 Involves ATP Hydrolysis and Is Enhanced by the Co‐Chaperone p23,” EMBO Journal 19, no. 21 (2000): 5930–5940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Adcock S. A. and McCammon J. A., “Molecular Dynamics: Survey of Methods for Simulating the Activity of Proteins,” Chemical Reviews 106, no. 5 (2006): 1589–1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Munjal N. S., Shukla R., and Singh T. R., “Physicochemical Characterization of Paclitaxel Prodrugs With Cytochrome 3A4 to Correlate Solubility and Bioavailability Implementing Molecular Docking and Simulation Studies,” Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics 40, no. 13 (2022): 5983–5995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tran Q. H., Nguyen Q. T., Vo N. Q. H., et al., “Structure‐Based 3D‐Pharmacophore Modeling to Discover Novel Interleukin 6 Inhibitors: An In Silico Screening, Molecular Dynamics Simulations and Binding Free Energy Calculations,” PLoS One 17, no. 4 (2022): e0266632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Que N. L., Crowley V. M., Duerfeldt A. S., et al., “Structure Based Design of a Grp94‐Selective Inhibitor: Exploiting a Key Residue in Grp94 to Optimize Paralog‐Selective Binding,” Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 61, no. 7 (2018): 2793–2805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Banumathy G., Singh V., Pavithra S. R., and Tatu U., “Heat Shock Protein 90 Function Is Essential for Plasmodium falciparum Growth in Human Erythrocytes,” Journal of Biological Chemistry 278, no. 20 (2003): 18336–18345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Attram H. D., Korkor C. M., Taylor D., Njoroge M., and Chibale K., “Antimalarial Imidazopyridines Incorporating an Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding Motif: Medicinal Chemistry and Mechanistic Studies,” ACS Infectious Diseases 9, no. 4 (2023): 928–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shahinas D., Folefoc A., Taldone T., Chiosis G., Crandall I., and Pillai D. R., “A Purine Analog Synergizes With Chloroquine (CQ) by Targeting Plasmodium falciparum Hsp90 (PfHsp90),” PLoS One 8, no. 9 (2013): e75446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Silva N. S., Torricillas M. S., Minari K., Barbosa L. R., Seraphim T. V., and Borges J. C., “Solution Structure of Plasmodium falciparum Hsp90 Indicates a High Flexible Dimer,” Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 690 (2020): 108468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zininga T., Achilonu I., Hoppe H., Prinsloo E., Dirr H. W., and Shonhai A., “Overexpression, Purification and Characterisation of the Plasmodium falciparum Hsp70‐z (PfHsp70‐z) Protein,” PLoS One 10, no. 6 (2015): e0129445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Minami Y., Kimura Y., Kawasaki H., Suzuki K., and Yahara I., “The Carboxy‐Terminal Region of Mammalian HSP90 Is Required for Its Dimerization and Function In Vivo,” Molecular and Cellular Biology 14, no. 2 (1994): 1459–1464, 10.1128/mcb.14.2.1459-1464.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stofberg M. L., Muzenda F. L., Achilonu I., Strauss E., and Zininga T., “In Silico Screening of Selective ATP Mimicking Inhibitors Targeting the Plasmodium falciparum Grp94,” Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics 43 (2024): 1–12, 10.1080/07391102.2024.2329304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Alao J. P., Obaseki I., Amankwah Y. S., et al., “Insight Into the Nucleotide Based Modulation of the Grp94 Molecular Chaperone Using Multiscale Dynamics,” Journal of Physical Chemistry B 127, no. 24 (2023): 5389–5409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jonsdottir T. K., Gabriela M., Crabb B. S., de Koning‐Ward T. F., and Gilson P. R., “Defining the Essential Exportome of the Malaria Parasite,” Trends in Parasitology 37, no. 7 (2021): 664–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bellstedt D. U., Van der Merwe K. J., and Galanos C., “Immune Carrier Properties of Acid‐Treated Salmonella minnesota R595 Bacteria: The Immune Response to TNP‐Bacterial Conjugates in Rabbits and Mice,” Journal of Immunological Methods 108, no. 1–2 (1988): 245–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Makumire S., Dongola T. H., Chakafana G., et al., “Mutation of GGMP Repeat Segments of Plasmodium falciparum Hsp70‐1 Compromises Chaperone Function and Hop Co‐Chaperone Binding,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 4 (2021): 2226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Miles A. J., Janes R. W., and Wallace B. A., “Tools and Methods for Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy of Proteins: A Tutorial Review,” Chemical Society Reviews 50, no. 15 (2021): 8400–8413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Varadi M., Anyango S., Deshpande M., et al., “AlphaFold Protein Structure Database: Massively Expanding the Structural Coverage of Protein‐Sequence Space With High‐Accuracy Models,” Nucleic Acids Research 50, no. D1 (2022): D439–D444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wu T., Hornsby M., Zhu L., Joshua C. Y., Shokat K. M., and Gestwicki J. E., “Protocol for Performing and Optimizing Differential Scanning Fluorimetry Experiments,” STAR Protocols 4, no. 4 (2023): 102688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Huynh K. and Partch C. L., “Analysis of Protein Stability and Ligand Interactions by Thermal Shift Assay,” Current Protocols in Protein Science 79, no. 1 (2016): 28–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zininga T., Achilonu I., Hoppe H., Prinsloo E., Dirr H. W., and Shonhai A., “ Plasmodium falciparum Hsp70‐z, an Hsp110 Homologue, Exhibits Independent Chaperone Activity and Interacts With Hsp70‐1 in a Nucleotide‐Dependent Fashion,” Cell Stress and Chaperones 21 (2016): 499–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Muthelo T., Mulaudzi V., Netshishivhe M., et al., “Inhibition of Plasmodium falciparum Hsp70‐Hop Partnership by 2‐Phenylthynesulfonamide,” Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 9 (2022): 947203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kayamba F., Malimabe T., Ademola I. K., et al., “Design and Synthesis of Quinoline‐Pyrimidine Inspired Hybrids as Potential Plasmodial Inhibitors,” European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 217 (2021): 113330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pooe K., Worth R., Iwuchukwu E. A., Dirr H. W., and Achilonu I., “An Empirical and Theoretical Description of Schistosoma japonicum Glutathione Transferase Inhibition by Bromosulfophthalein and Indanyloxyacetic Acid 94,” Journal of Molecular Structure 1223 (2021): 128892. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Supporting Information.

Table S3. PfGrp94 in complex with ADP/ADP/NECA and in its Apo state of the radius of gyration values.

Table S4. PfGrp94 in complex with ADP/ADP/NECA and in its Apo state of the RMSD values.