Abstract

Dual functionalization in organic synthesis represents a powerful strategy aimed at achieving multiple transformations within a single reaction cycle, thereby streamlining synthetic processes, enhancing efficiency, and imparting economic paths for complex molecules. Here, we report a heterogeneous perovskite nanocrystal (NC) photocatalytic system that can simultaneously drive two photoredox cycles in a single reaction. The dual process incorporates two distinct functional groups (N-heterocycles and bromines) into N-arylamines under the influence of a single catalyst (CsPbBr3 NCs), allowing for the concurrent formation of two distinct architectures of 3-bromo-N-arylindoles. Mechanistically, long-lived charge separation and charge carrier accumulation at the NC surface enable perovskite to drive these two photoredox cycles simultaneously. The dual approach exploits light-induced holes to drive an amine oxidation in one cycle (I) and cooperatively utilizes dibromomethane (CH2Br2), a solvent-grade mild reagent for site-selective bromination, to achieve the other photoredox cycle (II). We find that chiral perovskite induces enantioselective axial C─N bond formation, but is inactive for axial C─C bond formation of arylindoles. Merging two photoredox cycles simultaneously to achieve dual functionalization is rare; thus, the perovskite NC photocatalysis not only aligns with the principles of green chemistry but also holds immense potential for the rapid and economical design of complex molecules.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, the field of photoredox catalysis has witnessed remarkable advancements in versatile chemical transformations.1,2 Photoredox cycles that are merged with other catalytic cycles, i.e. organocatalysis, have pioneered the modern approach for visible-light photocatalytic organic synthesis (e.g., the imidazoline-based organocatalytic cycle, Scheme 1a).3 A photocatalytic cycle that is merged with transition metal catalysis can be particularly powerful, leading to intricate organic reactions (e.g., the Ni catalytic cycle, Scheme 1b).4-6 Recently, such photoredox reactions have also been reported to couple with enzymatic biocatalysis to reach highly enantioselective organic synthesis that cannot be achieved with traditional catalytic methods (e.g., Scheme 1c).7,8

Scheme 1. Photoredox Cycle Coupled with (a) Organocatalysis, (b) Transition Metal Catalysis, (c) Biocatalysis, and (d) Our Work with Another Photoredox Cycle.

Our lab has also designed highly efficient heterogeneous photoredox cycles that merge perovskite photocatalysis with surface-bound transition metal copper catalysis,9 organo-imine catalysis, and radical catalysis.10 Photoredox cycles coupled with other well-developed cocatalytic cycles have revolutionized the modern organic synthetic methodology design and development.6 In general, such cocatalytic cycles in a photoredox approach are usually photocatalytically inactive, meaning that the photoredox cycle has not yet been coupled with another photoredox cycle, probably due to the following challenge: excited states of molecular photocatalysts are only able to promote single-electron-transfer (SET) events.6,11 However, heterogeneous photoredox systems, i.e. semiconductor NCs, are able to induce consecutive charge transfer events, realizing remarkable multiple-charge-transfer photoredox products.9 Herein, we rationally question whether a photoredox cycle may directly couple with another photocatalytic reaction cycle to achieve unprecedented photocatalytic dual functionalization in a single-step one-pot reaction under visible-light illumination.

Perovskite photocatalysis is a unique heterogeneous approach for organic synthesis. The key success for photocatalysis relies on its unique photophysical properties, i.e., an extremely long-lived charge separation state,12,13 an ultralong carrier migration length (up to 175 μm),14 extraordinarily slow charge recombination rates,15 etc. Such properties have been exploited to achieve a high-efficiency photovoltaic performance.16 Our lab also demonstrated that key aspects of both photocatalytic and photovoltaic applications rely on efficient charge separation and charge transfer, rendering halide perovskite semiconductors as an exceptional candidate for photocatalysis, particularly toward unique organic transformations.15 For instance, the perovskite NC photocatalyst can induce consecutive hole transfers to oxidize a surface-bound diamine complex, i.e., by forming an unexpected diamine diradical intermediate, leading to the production of unexpected labile N─N heterocyclic complexes.9

In light of halide perovskite’s unique photophysical properties, particularly, extremely long-lived charge separation and the recently discovered local charge carrier accumulation on the perovskite surface,17-20 herein, we explore if such surface-accumulated charge carriers are long-lived enough to directly initiate multiple types of substrate activations in a single reaction. In other words, can perovskite NCs merge multiple photoredox cycles in one reaction vial and lead to multiple functionalization? To prove this concept, we exploit perovskites to merge two photoredox catalytic cycles in a single reaction to achieve two distinct chemical reactions simultaneously and target photocatalytic dual functionalization.

Dual functionalization in catalytic organic synthesis represents an innovative and powerful strategy aimed at achieving multiple transformations within a single reaction, thereby streamlining synthetic processes and enhancing efficiency.21-24 This approach involves the incorporation of two distinct functional groups into a target molecule under the influence of a single catalyst, allowing for the simultaneous formation of intricate molecular architectures. Traditionally, organic synthesis has often involved sequential steps, each dedicated to introducing specific functional groups or modifying particular regions of a molecule. Dual functionalization, on the other hand, seeks to consolidate these steps into a unified process, reducing the number of required synthetic operations and minimizing waste generation. The heterogeneous photocatalytic dual functionalization not only aligns with the principles of green chemistry but also holds immense potential for the rapid and economical synthesis of complex molecules. The catalytic merit of photocatalytic dual functionalization is particularly noteworthy, as it leverages the efficiency, selectivity, and versatility of catalysts to orchestrate multiple transformations in a controlled manner.

In this work, two photoredox cycles with a single catalyst are realized for dual functionalization of N-heterocyclization and site-selective bromination for the synthesis of 3-bromo-N-arylindoles (Scheme 1d), a direct follow-up study of our previously reported N-heterocyclizations.25,26 Extremely long-lived charge separation and local charge carrier accumulation on the NC surface make such dual functionalization possible. We delve into the advancements of asymmetric catalytic synthesis using the respective chiral perovskite R-MBA/CsPbBr3 (MBA: methylbenzylamine) for N─C axially chiral N-arylindoles. The mechanistic insights, crystal structures, and scope of the dual functionalization are also revealed. We aim to exploit halide perovskite’s unique properties to merge two photoredox cycles and achieve multiple transformations within a single reaction, thereby streamlining synthetic processes and enhancing efficiency for the rapid and economical design of complex molecules.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Our dual functionalization approach was initiated by an accidental discovery when we explored the asymmetric N-heterocyclization reaction targeting N-arylindoles (Table 1). In addition to the desired ring-closure complex 2a′, we also observed a Cl-substituted side product in the C-3 position, compound 2a″, albeit in a low yield. This chlorinated product must have been sourced from the chlorinated solvent dichloromethane (DCM). Control experiments (Table 1) indicated that air and DCM are both necessary to observe 2a″. For instance, without air but with DCM, no ring closure was observed; however, the chlorination still occurs on the phenyl group (1a′). In other nonhalogenated solvents and with air, only the ring-closure product 2a′ was observed; without air and in nonhalogenated solvents, neither product was observed (entries 2–4). These reactions also required visible-light illumination; otherwise, no product could be generated (entry 5). The results (summarized in Table 1) indicate that two independent photoredox cycles occurred; cycle I consists of a light-assisted oxygen-involved reaction inducing ring closure, while cycle II consists of a halogen solvent photoactivation reaction that promotes site-selective aromatic halogenation.

Table 1.

Control Experimentsa

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | solvents | oxygen | 2a′ | 2a″ | 1a′ |

| 1b | CH2Cl2/pentane (1:1 v/v) | atm O2 | 72 | 5 | |

| 2 | CH2Cl2/pentane (1:1 v/v) | 40 | |||

| 3 | toluene | atm O2 | 45 | ||

| 4 | toluene | ||||

| 5c | CH2Cl2/pentane (1:1 v/v) | atm O2 | |||

Reaction conditions: 1a (0.05 mmol), CsPbBr3 NCs (1 mg), with or without atm O2, 500 μL of solvents, irradiation with a blue 456 nm LED at room temperature for 24 h.

With SiO2 (5 mg).

No light.

Optimization.

We synthesized the perovskite CsPbBr3 nanocrystal in the size range of 15–30 nm (larger than the Bohr radius, no quantum confinement, photophysical properties determined by bulk materials, details in the Supporting Information) according to our previous method.15,25 We further explored the reaction conditions to understand the potential to merge the two photoredox cycles to realize dual functionalization with a synthetic significance. Styrylamine 1a was employed as a model substrate for the organic reaction optimization. Here, we focused on screening the key parameters toward a higher reaction yield of the model reaction, such as the loading amount of the optimized catalyst NCs, the reaction solvents, and other key conditions (Table 2). The previous catalyst optimizations exclusively employed CH2Cl2 as the solvent with the highest yield of 72% 2a′ in the presence of SiO226 (Table 1, entry 1). To our delight, we observed a trace amount of bromoindole 2a and chloroindole 2a″ in the absence of SiO2, probably due to the light-induced halide exchange between CsPbBr3 and DCM27 (Table 2, entry 1). With this observation, we further explored halogenated solvents, such as adding dibromomethane (DBM) as the halogen source in the system and gradually increased the volume of DBM from 50 to 200 μL to the reaction system (Table 2, entries 2–4). We observed the desired bromoindole product 2a in a 43% yield (Table 2, entry 5). A polar solvent such as CH3CN was reported to give a high yield of N-heterocyclization.28 We then explored DBM as the bromosource in the mixed solvent system.

Table 2.

Optimization of the Reaction Conditionsa

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | solvents | CH2Br2 | indole | 2ab | time (h) |

| 1 | CH2Cl2/pentane (1:1 v/v) | 31 | trace | 24 | |

| 2 | CH2Cl2/pentane (1:1 v/v) | 50 μL | 26 | 5 | 24 |

| 3 | CH2Cl2/pentane (1:1 v/v) | 100 μL | 22 | ~10 | 24 |

| 4 | CH2Cl2/pentane (1:1 v/v) | 200 μL | 20 | ~10 | 4 |

| 5 | pentane | 100 μL | 10 | 43 | 4 |

| 6 | CH3CN/pentane (1:1 v/v) | 100 μL | 5 | 63 | 6 |

| 7c | CH2Br2 only | 2 mL | 41 | 8 | |

| 8 | CH3CN only | 100 μL | 7 | 53 | 6 |

| 9d | CH3CN/pentane (1:1 v/v) | 100 μL | 6 | ||

| 10e | CH3CN/pentane (1:1 v/v) | 100 μL | 79 | 6 | |

Reaction conditions: 1a (0.05 mmol), CsPbBr3 NCs (1 mg), open to air, 500 μL of solvents, irradiation with a blue 456 nm LED at room temperature.

Isolated yield.

Multiple bromination side products observed.

No photocatalyst added.

Indole as the starting material, under an air-free condition.

In general, we found that a mixed acetonitrile/dibromomethane/pentane solvent system, as shown in entry 6, gives a yield of 2a up to 63%. Note that a higher concentration of DBM results in a lower yield of 2a due to the multiple bromination product (Table 2, entry 7). Even the acetonitrile and dibromomethane solvent system, as shown in entry 8, gives 2a in a 53% yield. As a control, we determined that the reaction leads to no product at all without a photocatalyst (Table 2, entry 9). Direct bromination of indole has also been explored, and a yield up to 79% of 2a has been obtained (Table 2, entry 10). Overall, we successfully optimize the reaction condition to merge the two photoredox cycles and achieve more than 60% yield of 3-bromo-N-arylindole with simultaneous photocatalytic N-heterocyclization and highly selective photocatalytic bromination of indole.

Scope.

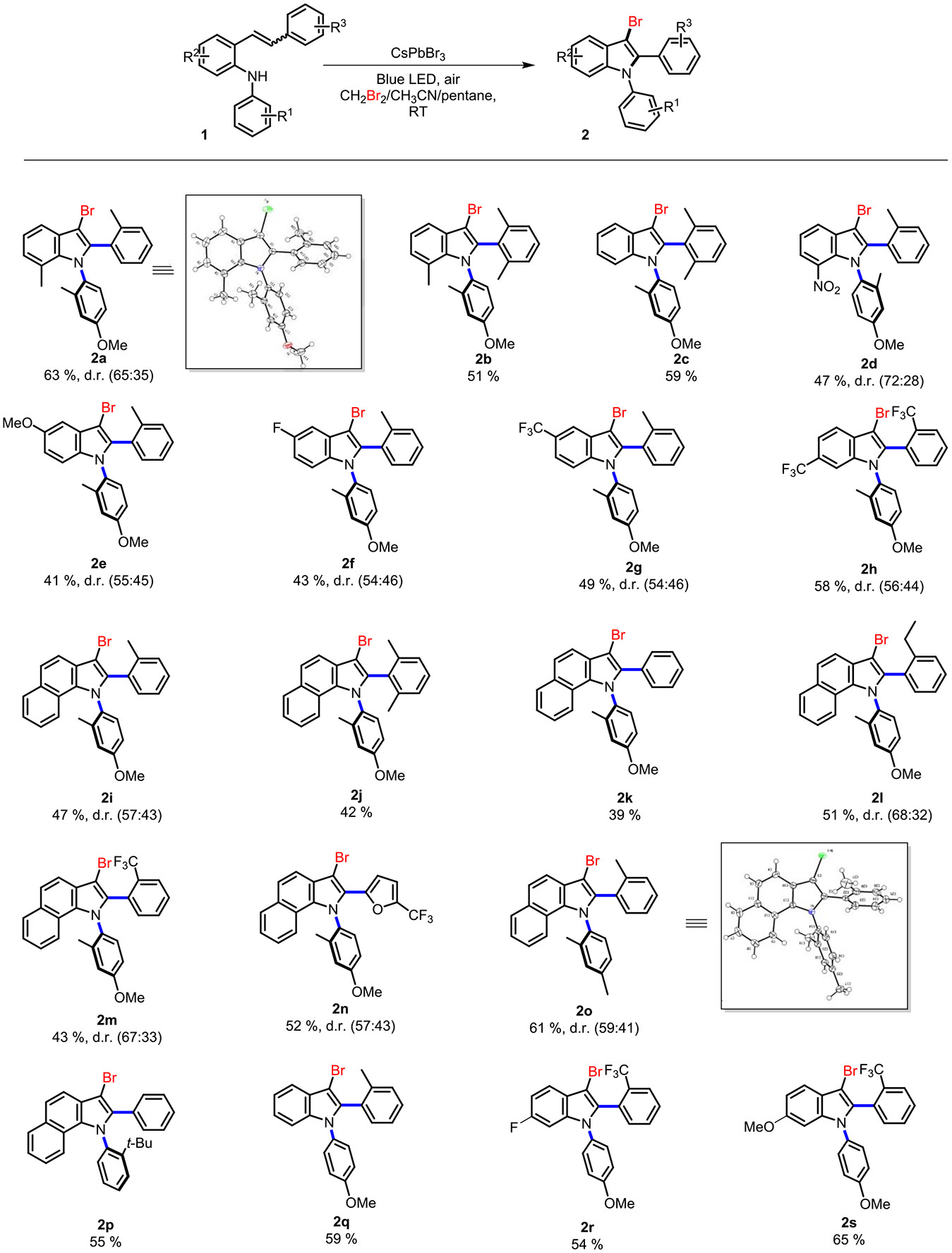

Indoles and their derivatives play a crucial role in the extensive realm of nitrogenous heterocycles. Among these, bromoindoles stand out as significant scaffolds due to their distinct biological activities and valuable synthetic versatility. Specifically, bromoindoles have showcased their adaptability as synthetic precursors, enabling the creation of diverse functionalized indole derivatives through cross-coupling reactions. This has spurred widespread interest in developing synthetic methodologies for site-selective bromoindoles. Typically, the synthesis of these bromoindoles involves electrophilic C─H bromination of indoles using various brominating reagents.29-32 Additionally, the intramolecular annulation/bromination of o-alkynylanilines or o-alkynylarylazides has proven to be an effective pathway to obtain 3-bromoindole derivatives.33,34 Furthermore, the use of palladium-catalyzed oxidative C─H activation/annulation of N-alkylanilines with bromoalkynes has provided another avenue for obtaining 3-bromoindoles.35 Despite considerable progress, many existing approaches face limitations, including the use of toxic and corrosive brominating reagents, low atom economy, and multistep processes (Scheme S1). In our reaction framework, the pivotal step involves the concurrent closure of a substrate ring followed by bromination using air and solvent-grade DBM with a good scope tolerance (Scheme 2). We prepared a series of N-arylamine substrates (1a–1s) through Buchwald–Hartwig amination, involving a 2-bromostyrene derivative and anilines. Under optimized conditions, various substrates underwent the reaction, resulting in moderate to good yields of N-aryl-bromoindoles (2a–2s). The reaction tolerates the presence of both electron-donating (2a, 2b, 2e) and electron-withdrawing groups (2d, 2f–2h, and 2r) on the aromatic rings. Notably, pharmaceutically relevant methoxy, fluoro, and trifluoromethyl substituents are amenable using this method. This photocatalytic strategy serves as a versatile approach for the regioselective introduction of bromosubstitution at the C-3 position of indoles. It is worth highlighting that the ortho group is not limited to just the methyl group; even the bulky tert-butyl group (2p), ethyl (2l), CF3 (2h), and heteroatom (2n) lead to the expected products with moderate to good yields. However, ortho-exploration with other functional groups, i.e. hydroxyl, amides, etc., is not successful. In summary, a good scope of dual functionalization that merges two photoredox cycles is successfully achieved in our approach.

Scheme 2. Reaction Scopea.

aConditions: NCs (1 mg), mixed solvent, blue LED at room temperature, d.r. (diastereoselective ratio, based upon 1H NMR).

Diastereoselectivity, a distinguishing feature of selective catalysis, is exemplified here in N-heterocyclization and bromination reactions. The specific spatial arrangement of stereocenters within a molecule, resulting from axial N─C chirality and axial C─C chirality, has a notable impact on its chemical properties and reactivity,36 such as cases where another chiral C─C center was located at the C-2-aryl position, i.e., 2a, 2d–2i, and 2l–2o compounds. However, moderate to poor diastereoselectivity was observed in this scope. A more significant diastereoselective compound 2d (72:28) was observed. Currently, we do not understand the mechanism that leads to higher diastereoselectivity in 2d compared with the others.

Crystal Structures.

Identifying the exact position of bromination with over 10 aromatic C─H positions is nontrivial. In addition to the NMR studies (Figure S1), we also relied on single-crystal X-ray diffraction to illustrate the site selectivity of photoredox cycle (II). The growth of single crystals for the compounds involved a controlled process of isopropyl alcohol and hexane solution evaporation. Figure S2 presents molecular representations of dual functionalization products 2a and 2o, demonstrating high site selectivity on the C-3 position of indoles. We also obtained the corresponding structures of indole intermediates 2a′ and 2o′. Within the rational comparison, we found that the bond lengths and bond angles of these two groups of crystal structures are quite similar; however, the dihedral angles (DAs) of the indole plane and N-aryl plane demonstrated significant disparity. For instance, the N-aryl plane in the indoles of 2a′ and 2o′ is generally more perpendicular (~90°) to the indole plane, while brominated 2a and 2o show a DA of ~110°, ca. 20° disparity as shown in Figure S2 (details in the Supporting Information). Such diverse conformations assumed by a small molecule may play a pivotal role in drug discovery, influencing its molecular recognition and thereby impacting its biological and therapeutic properties.37

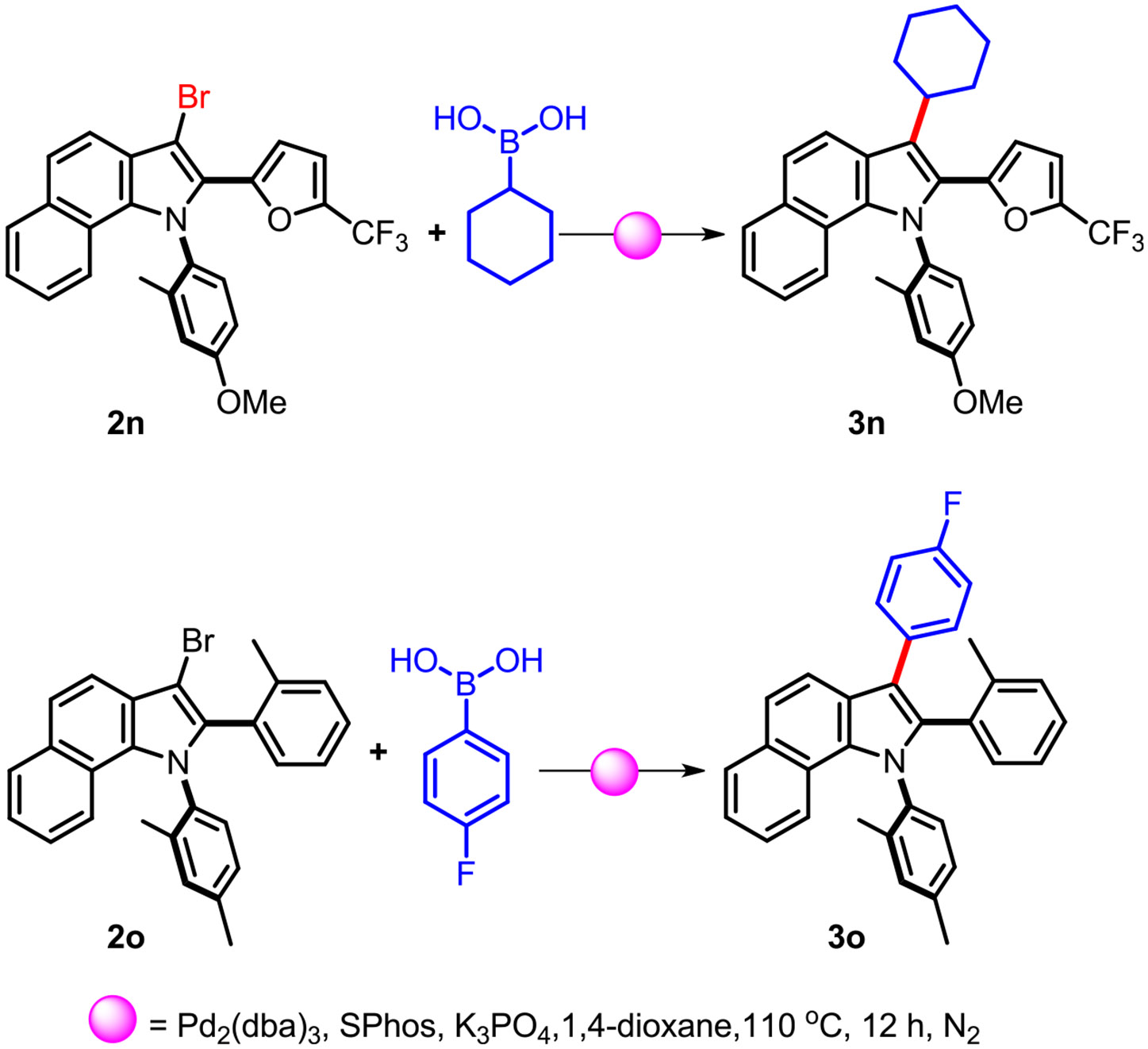

Pharmaceutically relevant complexes may directly benefit from this dual functionalization process. Brominated heterocycles are important precursors in organic synthesis, allowing for the rational introduction of other important frameworks by means of fundamental reactions such as Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling. The N-heterocyclization cycle (I) and mild bromination cycle (II) using DBM render a plausible site-selective C-3 bromoindole scaffold. To further investigate the synthetic potential of 3-bromoindole, the Suzuki–Miyaura approach was conducted to explore functionalized indoles that are of pharmaceutical significance, as illustrated in Scheme 3. Notably, employing cyclohexylboronic acid as the coupling partner resulted in the formation of 3n with a yield of 45% (Scheme 3), structurally relevant to the pharmaceutical analogue of BMS-791325 which is undergoing different phases of clinical evaluation as a hepatitis C inhibitor.38 Furthermore, utilizing 4-fluorophenyl boronic acid led to the synthesis of 3o with a yield of 51%, demonstrating structural relevance to fluvastatin, a drug capable of reducing cholesterol and triglyceride levels.39

Scheme 3. Derivatization of the Dual Functionalization Product.

The crystal structure not only guided us in assigning ambiguous Br site selectivity but also helped us to understand the reactivity of photoredox cycle (II). With the presence of excess DBM, under prolonged catalysis, we indeed observe a dibromination process with the second bromination occurring on the C-5 position as shown in 2k″ (Figure S2). Note that 2k′ and 2k″ also show similar disparity in the respective DAs. Even though separation of the dibromination product from the reaction mixture is unsuccessful, 2k and 2k″ indeed cocrystallize together and we were able to refine their structures. The crystal structure indicates that partial bromination of the C-5 position (details in the Supporting Information) is observed in ~20% in this case, meaning that the second most reactive site of such an N-arylindole that bears more than 10 aromatic C-H positions prefers C-5 bromination under our merged photoredox catalytic system, which was also confirmed by GCMS analysis.

Enantioselective Exploration.

We further explore the enantioselectivity of this dual functionalization reaction system (Scheme 4 and Figure S3). As we previously explored, we replaced the current NC catalyst with its chiral form, namely, R-MBA/CsPbBr3. Under otherwise same conditions, we particularly explore the enantioselective outcomes for the complexes that bear two axially chiral bonds, such as 2a, with both N─C and C─C axially chiral centers. We found that 2a demonstrated ~60% ee. We also study the cases of 2k that only have one chiral center of the N─C bond with 72% ee. The enantioselectivity is slightly lower than the respective 2a′ or 2k′, likely because the bromination step in cycle (II) may induce some level of racemization after cycle (I). Note that the enantioselective optimization has not been explored here. Overall, similar to our previous conclusion on N-heterocyclizations, enantioselective control over the axial N─C bonds, illustrated as photoredox cycle (I), is still amendable in this dual functionalization system. However, chiral control (using the same chiral NCs) over the axial C─C bond, i.e., 2q, is not successful, meaning that chiral discrimination of the intermediate surface binding, as we discussed for the enantioselective mechanism in the previous report,26 has little impact toward photoredox cycle (II), illustrated here as the photocatalytic bromination reaction.

Scheme 4. Enantioselective Exploration of 2a, 2k, and 2q.

From a structural point of view, the above enantioselective results are unsurprising for our merged photoredox cycles. As illustrated from the crystal structures, i.e., 2a or 2o, the locking ortho-methyl group on the C-2 aryl, energetically favors the position far away from the N-aryl group, meaning that the enantiorich N─C group plays little influence to dictate the axial C─C rotation of the C-aryl ring. In other words, the ortho-methyl group of the C-aryl ring still enjoys the freedom to move above or below the indole plane, resulting in no enantioselectivity for the bromination step. Therefore, even with the chiral photocatalyst, under enantioselective N-heterocycles, further bromination of the C-3 position has not been stereocontrolled. In general, our enantioselective results show that asymmetric synthesis of N-arylindole is still achievable in photoredox cycle (I), while the enantioselective control over the axial chiral C─C bond of photoredox cycle (II) for bromination is unsuccessful. Further work to realize photocatalytic asymmetric bromination of photoredox cycle (II) is still under investigation in our lab.

Mechanism.

Scheme 5 outlines the proposed photocatalytic pathway to merge the two photoredox cycles. Photoredox cycle (I) has been recently studied by our group, where the substrate must approach the nanocrystal’s surface for charge transfer (hole transfer from the valence band, VB, +1.1 V vs SCE),40,41 likely facilitated by a weak hydrogen-bonding interaction between the N-arylamine substrate and the nanocrystals’ surface, leading to the formation of N-arylamine radicals.26 Note that such a surface-binding reaction is critical because the chiral NC surface here can distinguish the enantioselective binding and lead to the final atroposelective ring-closure product. Oxygen is necessary for the ring-closure step where O2 is first reduced, forming the O2-radical anion by receiving an electron from the conduction band (CB, −1.3 V vs SCE).40-43 Such an intermediate is critical to experience a few hydrogen atom abstraction steps, facilitating the ring closure and finally leading to the side product of H2O2, which has also been verified through the fluorometric hydrogen peroxide assay, as reported previously.9 It is important to note that the molecular photocatalyst, i.e. [Ru(phen)3]2+, is also active toward such N-heterocyclization, though in a nonenantioselective manner.31 However, further bromination to reach dual functionalization has not been successful (Table 3, entry 2). Other common photocatalysts have also been explored. Ru, Ir, CzIPN, and CdS quantum dot catalysts are able to close the ring for N-heterocyclization but no further site-selective bromination production. Acridinium with a much higher excited oxidation potential leads to the formation of trace amounts of halogenated N-arylamine, but no dual product 2a can be isolated. Overall, none of the molecular photocatalytic systems or CdS quantum dot system showed the desired reactivity, leading to the dual functionalization product under the current condition (Table 3).

Scheme 5. Proposed Mechanism for N-Heterocyclization and Subsequent Bromination of Indole.

Table 3.

Photocatalyst Comparison for the Dual Functionalization of 2aa

| entry | photocatalyst | yield (%)b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2a′ | 2a | ||

| 1 | CsPbBr3 | 63 | |

| 2 | [Ru(phen)3]2+ | 65 | |

| 3 | [Ru(bpy)3]2+ | 17 | |

| 4 | Ir(ppy)3 | 79 | |

| 5 | 4-CzIPN | 73 | |

| 6 | CdS | 66 | |

| 7c | [Acr-Mes]BF4 | ||

Reaction conditions: 1a (0.05 mmol), open to air, dibromomethane (100 μL) added, irradiation with a Kessil 456 nm LED at room temperature for 24 h.

Isolated yield.

A brominated, ring-open amine detected.

Photoredox cycle (II) is a light-induced bromination step resulting from DBM as a mild oxidant. Compared to the previous approach for photocatalytic bromination of trimethoxybenzene which required oxygen as the oxidant,42 our approach here did not necessarily require any external oxidant (e.g., oxygen), but directly relied on the oxidative nature of the halogenated solvent. As a control experiment, we explored our bromination using 2a′ in DBM in a sealed system without any external oxidant; we were still able to isolate brominated 2a. The mechanistic approach is proposed in Scheme 5, where hole oxidation of N-arylindole 2a′ leads to the respective N-radical cation 2A, as indicated by the strong Stern–Volmer quenching constant (Figure S4). Meanwhile, we10,41 and others27 extensively explored the light-induced electron from the CB to initiate halogenated solvent reduction where bromide anions and the CH2Br radical are generated from DBM. We proposed that the generated CH2Br radical on the surface of NCs might be a good hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) reagent here43 that could abstract the H atom from the intermediate 2C forming 2. Such a HAT assumption has been confirmed by the formation of CH3Br as the byproduct for this bromination reaction. Hence, the HAT process closes photoredox cycle (II) for the ultimate dual-functionalized product 2 formation.

We also conducted time-dependent GCMS studies to explore the intermediates of this dual functionalization path (Figure S5). Our result showed that the formation of N-arylindole 2′ of photoredox cycle (I) occurred initially, while a small fraction of brominated 2 from cycle (II) was observed in the first 2 h of the reaction. In the 2–6 h range, the fraction of 2′ in the reaction is seldomly changed, probably reaching a steady state where generation of 2′ from cycle (I) and consumption of 2′ from cycle (II) reach an equilibrium. When the reaction reached 8 h, 2′ was greatly consumed, and 2 was dominant in the reaction vial according to the GCMS result. In this case, the C-3 position is highly site-selective. When excess DBM and a longer illumination time were employed, we indeed observed a further brominated product, i.e., dibromination of 2″, as shown by GCMS, indicating that a C-5 position was a followed/preferred bromination after the bromination of the C-3 position. Overall, the site selectivity for aromatic bromination was illustrated with the C-3 position highly prioritized among more than 10 aromatic C─H positions of our N-heterocycles.

Dual functionalization reactions always involve the interference between the radical intermediates among these individual cycles. For instance, Br anions may directly react with 1D in cycle (I) instead of the intermediate 2B in cycle (II). We cannot completely rule out the possibility of such a route, but this route would lead to the formation of a dearomatic C-3 Br-substituted intermediate. Our GCMS results do not show any evidence of such an intermediate, but only shows the intermediate of 2′. In addition to the proposed merged cycles, other probable mechanistic cycles are also plausible. For instance, cycle (II) may go through a solvent-based redox cycle as we previously studied,41 where DBM was reduced to form Br anions with electrons from the CB and holes from the VB, instead of reacting with 2′, but it actually oxidized the Br anion, forming the Br radical. According to Xie et al.,42 two such Br radicals may further react to form Br2. Hence, Br2 may directly react with our N-heterocycle 2′ through an electrophilic aromatic substitution reaction and therefore a close photoredox cycle (II) to realize the dual functionalization. The Br radical-based chain reaction mechanism was also considered; however, the quantum yield was measured below 1% in a 6 h period in our system (details in the Supporting Information). Regardless, there still should be two merged photoredox cycles to activate the N-heterocyclization reaction (cycle I) and another photoredox cycle (II) for the site-selective bromination to achieve the dual functionalization described above.

How can we understand two photoredox cycles occurring in a single reaction system? It has been recently shown with time-resolved spectroscopy and first-principles calculations that in addition to extremely long-lived charge separation, spatially varying energetic disorder in the electronic states induces local charge accumulation, therefore creating p- and n-type photodoped regions on the NC surface, leading to efficient light emission at low charge injection in solar cells and light-emitting diodes.17 Nanoscale charge accumulation on NC surfaces has also been revealed and its effect on carrier dynamics were studied to directly correlate charge accumulation between nanoscale ionic transport, recombination properties, and the final solar cell performance.18,20 Such studies are phenomenal because they illustrate halide perovskite’s unique properties for solar cell and light-emitting diode performance. Since photocatalysis may rely on the same mechanism for charge separation and charge transfer,15 we speculated that such a light-induced long-lived charge separation state as well as charge carrier accumulation in the photocatalytic system may also induce multiple p- and n-type photodoped regions on the perovskite surface, as previously illustrated.17 If the spectroscopic observation of multiple charge carrier accumulations on the perovskite17-20 is indeed occurring, in a suitable photocatalytic system, such carrier accumulations may also lead to multiple redox reactions. SET-based molecular photocatalysts explored here cannot induce desired multiple functionalization, as they are quite active toward cycle (I) for ring closure but inactive for cycle (II) (Table 3).

CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVE

In summary, perovskites play a vital role in facilitating reactions that might otherwise be challenging or impractical under traditional conditions. The extreme long-lived charge separation state and charge accumulation leading to massive p-/n-type photodoped regions on the perovskite surface may render the unique photocatalytic ability of such materials. The perovskite NCs with a size larger than the Bohr radius can promote dual functionalization reactions that have not been previously achieved in a single reaction step. Our approach successfully merges two photoredox cycles that enable efficient enantioselective N-heterocyclization and site-selective bromination reactions. Air and dibromomethane are employed as economic oxidants to realize such a unique streamlined strategy for the simultaneous incorporation of heterocycles and bromine atoms into organic substrates.

Overall, merging two photoredox cycles for photocatalytic organic dual functionalization has emerged as a powerful and transformative approach, offering unprecedented opportunities for the simultaneous incorporation of multiple functional groups into organic molecules. The synergy of visible-light-driven catalysis and the ability to execute two distinct transformations within a single reaction represent a paradigm shift in synthetic methodology. The applications of photocatalytic dual functionalization extend across diverse areas, from pharmaceuticals to materials science, enabling the streamlined synthesis of complex and multifunctional compounds.

As we navigate the frontiers of photocatalytic organic dual functionalization, challenges, such as substrate scope, reaction scalability, and catalyst design, continue to stimulate innovative research. Ongoing efforts are directed toward expanding the synthetic toolbox, enhancing catalytic efficiency, addressing sustainability concerns, and particularly realizing high enantioselective paths (i.e., in cycle II). Overall, photocatalytic dual functionalization stands at the forefront of innovation, promising exciting possibilities for the future of synthetic chemistry.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General Procedure for the Synthesis of NCs (Tip Sonication Method).

The NCs were synthesized with a slight modification of the reported one.44,45 First, two precursor salts Cs2CO3 (33 mg, 0.1 mmol) and PbBr2 (110 mg, 0.3 mmol) were taken in a dried vial, along with 10 mL of 1-octadecene. 0.5 mL of oleic acid and 0.5 mL of oleylamine were added. The reaction mixture was then subjected to tip sonication (FisherBrand, Fisher Scientific, FB120) for 30 min. The colorless solution gradually changed into a yellow color, exhibiting strong characteristic PL emission under UV light, indicating the formation of CsPbBr3 perovskite NCs. The as-synthesized perovskite NCs were purified by two washings with n-pentane followed by centrifugation at a speed of 7000 rpm for 10 min to get rid of unreacted precursors.

General Procedure for the Preparation of 2.

CsPbBr3 perovskites (NCs, 1 mg) were added to a solution of 1 (20 mg, 0.05 mmol) in CH3CN/CH2Br2/pentane (4:1:1) under air. The mixture was stirred for 20 h under a blue LED at room temperature. The crude mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure and purified by flash chromatography on silica gel eluted with Hexane/EtOAc = 10/0.2 to afford the corresponding product 2.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The atroposelective catalysis was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS), the NIH, under Award R35GM147260. The development of hybrid perovskite materials was supported as a part of the Center for Hybrid-Organic Inorganic Semiconductors for Energy (CHOISE), an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences within the US Department of Energy. The authors acknowledge Dr. M. Beard’s helpful discussion. Support for the acquisition of the Bruker Venture D8 diffractometer through the Major Scientific Research Equipment Fund from the President of Indiana University and the Office of the Vice President for Research is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.joc.4c03045.

Experimental procedure, characterization of products, spectroscopic data, and crystallographic data for compounds 2a, 2a′, 2o, 2o′, 2h, 2k′, and 2k″. (PDF)

Accession Codes

Deposition Number 2332115 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge via the joint Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) and Fachinformationszentrum Karlsruhe Access Structures service.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Kanchan Mishra, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, San Diego State University, San Diego, California 92182, United States.

Isaac Hendrix, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, San Diego State University, San Diego, California 92182, United States.

Jesse Gerardo, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, San Diego State University, San Diego, California 92182, United States.

Nobuyuki Yamamoto, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, San Diego State University, San Diego, California 92182, United States; Molecular Structure Center, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana 47405, United States.

Yong Yan, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, San Diego State University, San Diego, California 92182, United States.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published articles and its online Supporting Information.

REFERENCES

- (1).Shaw MH; Twilton J; MacMillan DWC Photoredox Catalysis in Organic Chemistry. J. Org. Chem 2016, 81, 6898–6926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Pirnot MT; Rankic DA; Martin DB; MacMillan DW Photoredox activation for the direct beta-arylation of ketones and aldehydes. Science 2013, 339, 1593–1596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Nicewicz DA; MacMillan DWC Merging Photoredox Catalysis with Organocatalysis: The Direct Asymmetric Alkylation of Aldehydes. Science 2008, 322, 77–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Zuo Z; Ahneman DT; Chu L; Terrett JA; Doyle AG; MacMillan DWC Merging photoredox with nickel catalysis: Coupling of α-carboxyl sp3-carbons with aryl halides. Science 2014, 345, 437–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Chan AY; Perry IB; Bissonnette NB; Buksh BF; Edwards GA; Frye LI; Garry OL; Lavagnino MN; Li BX; Liang Y; Mao E; Millet A; Oakley JV; Reed NL; Sakai HA; Seath CP; MacMillan DWC Metallaphotoredox: The Merger of Photoredox and Transition Metal Catalysis. Chem. Rev 2022, 122, 1485–1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Skubi KL; Blum TR; Yoon TP Dual Catalysis Strategies in Photochemical Synthesis. Chem. Rev 2016, 116, 10035–10074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Ye Y; Cao J; Oblinsky DG; Verma D; Prier CK; Scholes GD; Hyster TK Using enzymes to tame nitrogen-centred radicals for enantioselective hydroamination. Nat. Chem 2023, 15, 206–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Fu H; Cao J; Qiao T; Qi Y; Charnock SJ; Garfinkle S; Hyster TK An asymmetric sp 3–sp 3 cross-electrophile coupling using ‘ene’-reductases. Nature 2022, 610, 302–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Martin JS; Zeng X; Chen X; Miller C; Han C; Lin Y; Yamamoto N; Wang X; Yazdi S; Yan Y; Beard MC; Yan Y. A Nanocrystal Catalyst Incorporating a Surface Bound Transition Metal to Induce Photocatalytic Sequential Electron Transfer Events. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2021, 143, 11361–11369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Lin Y; Avvacumova M; Zhao R; Chen X; Beard MC; Yan Y. Triplet Energy Transfer from Lead Halide Perovskite for Highly Selective Photocatalytic 2 + 2 Cycloaddition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 25357–25365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Prier CK; Rankic DA; MacMillan DWC Visible Light Photoredox Catalysis with Transition Metal Complexes: Applications in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev 2013, 113, 5322–5363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Deng S; Snaider JM; Gao Y; Shi E; Jin L; Schaller RD; Dou L; Huang L. Long-Lived Charge Separation in Two-Dimensional Ligand-Perovskite Heterostructures. J. Chem. Phys 2020, 152, No. 044711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).deQuilettes DW; Frohna K; Emin D; Kirchartz T; Bulovic V; Ginger DS; Stranks SD Charge-Carrier Recombination in Halide Perovskites. Chem. Rev 2019, 119, 11007–11019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Dong Q; Fang Y; Shao Y; Mulligan P; Qiu J; Cao L; Huang J. Electron-hole diffusion lengths > 175 μm in solution-grown CH3NH3PbI3 single crystals. Science 2015, 347, 967–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Zhu X; Lin Y; San Martin J; Martin JS; Sun Y; Zhu D; Yan Y. Lead halide perovskites for photocatalytic organic synthesis. Nat. Commun 2019, 10, No. 2843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Best Research-Cell Efficiency Chart. 2019. https://www.nrel.gov/pv/cell-efficiency.html.

- (17).Feldmann S; Macpherson S; Senanayak SP; Abdi-Jalebi M; Rivett JPH; Nan G; Tainter GD; Doherty TAS; Frohna K; Ringe E; Friend RH; Sirringhaus H; Saliba M; Beljonne D; Stranks SD; Deschler F. Photodoping through local charge carrier accumulation in alloyed hybrid perovskites for highly efficient luminescence. Nat. Photonics 2020, 14, 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Kim HS; Mora-Sero I; Gonzalez-Pedro V; Fabregat-Santiago F; Juarez-Perez EJ; Park NG; Bisquert J. Mechanism of carrier accumulation in perovskite thin-absorber solar cells. Nat. Commun 2013, 4, No. 2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Yang W; Jo SH; Tang Y; Park J; Ji SG; Cho SH; Hong Y; Kim DH; Park J; Yoon E; Zhou H; Woo SJ; Kim H; Yun HJ; Lee YS; Kim JY; Hu B; Lee TW Overcoming Charge Confinement in Perovskite Nanocrystal Solar Cells. Adv. Mater 2023, 35, No. 2304533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Toth D; Hailegnaw B; Richheimer F; Castro FA; Kienberger F; Scharber MC; Wood S; Gramse G. Nanoscale Charge Accumulation and Its Effect on Carrier Dynamics in Tri-Cation Perovskite Structures. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 48057–48066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Moriyama K. Recent Advances in Retained and Dehydrogenative Dual Functionalization Chemistry. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2021, 2021, 2077–2090. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Xu L; Kuan SL; Weil T. Contemporary Approaches for Site-Selective Dual Functionalization of Proteins. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2021, 60, 13757–13777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Kim MH; Nguyen H; Chang C-Y; Lin C-C Dual Functionalization of Gelatin for Orthogonal and Dynamic Hydrogel Cross-Linking. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 2021, 7, 4196–4208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Guo H; Ruan X; Xu Z; Wang K; Li X; Jiang J. Visible-Light-Mediated Dual Functionalization of Allenes: Regio- and Stereoselective Synthesis of Vinylsulfone Azides. J. Org. Chem 2024, 89, 665–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Zhu X; Lin Y; Sun Y; Matt B; Yan Y. Lead-Halide Perovskites for Photocatalytic α-Alkylation of Aldehydes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 733–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Mishra K; Guyon D; Martin JS; Yan Y. Chiral Perovskite Nanocrystals for Asymmetric Reactions: A Highly Enantioselective Strategy for Photocatalytic Synthesis of N–C Axially Chiral Heterocycles. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2023, 145, 17242–17252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Parobek D; Dong Y; Qiao T; Rossi D; Son DH Photoinduced Anion Exchange in Cesium Lead Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 4358–4361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Maity S; Zheng N. A Visible-Light-Mediated Oxidative C–N Bond Formation/Aromatization Cascade: Photocatalytic Preparation of N-Arylindoles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2012, 51, 9562–9566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Chhattise PK; Ramaswamy AV; Waghmode SB Regioselective, photochemical bromination of aromatic compounds using N-bromosuccinimide. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Shi L; Zhang D; Lin R; Zhang C; Li X; Jiao N. The direct C–H halogenations of indoles. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 2243–2245. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Kajita H; Togni A. A Oxidative Bromination of (Hetero)-Arenes in the TMSBr/DMSO System: A Non-Aqueous Procedure Facilitates Synthetic Strategies. ChemistrySelect 2017, 2, 1117–1121. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Li Z; Tang M; Hu C; Yu S. Atroposelective Haloamidation of Indoles with Amino Acid Derivatives and Hypohalides. Org. Lett 2019, 21, 8819–8823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Sun L; Zhang X; Wang C; Teng H; Ma J; Li Z; Chen H; Jiang H. Direct electrosynthesis for N-alkyl-C3-halo-indoles using alkyl halide as both alkylating and halogenating building blocks. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 2732–2738. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Zhang J; Shi S-Q; Hao W-J; Dong G-Y; Tu S-J; Jiang B. Tunable Electrocatalytic Annulations of o-Arylalkynylanilines: Green and Switchable Syntheses of Skeletally Diverse Indoles. J. Org. Chem 2021, 86, 15886–15896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Fang S; Chen W; Jiang H; Ma R; Wu W. Palladium-Catalyzed Oxidative C-H Activation/Annulation of N-Alkylanilines with Bromoalkynes: Access to Functionalized 3-Bromoindoles. Chem. Commun 2022, 58, 9666–9669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Chung W-J; Vanderwal CD Stereoselective halogenation in natural product synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2016, 55, 4396–4434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Brameld KA; Kuhn B; Reuter DC; Stahl M. Small Molecule Conformational Preferences Derived from Crystal Structure Data. A Medicinal Chemistry Focused Analysis. J. Chem. Inf. Model 2008, 48, 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Zhang M-Z; Chen Q; Yang G-F A Review on Recent Developments of Indole-Containing Antiviral Agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2015, 89, 421–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Adams SP; Sekhon SS; Tsang M; Wright JM Fluvastatin for lowering lipids. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev 2018, 2018, No. CD012282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Martin JS; Dang N; Raulerson E; Beard MC; Hartenberger J; Yan Y. Perovskite Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction or Photoredox Organic Transformation? Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2022, 61, No. e202205572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Lin Y; Yan Y. CsPbBr3 Perovskite Nanocrystals for Photocatalytic [3 + 2] Cycloaddition. ChemSusChem 2024, 17, No. e202301060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Li Y; Wang T; Wang Y; Deng Z; Zhang L; Zhu A; Huang Y; Zhang C; Yuan M; Xie W. Tunable Photocatalytic Two-Electron Shuttle between Paired Redox Sites on Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 5903–5910. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Capaldo L; Ravelli D; Fagnoni M. Direct Photocatalyzed Hydrogen Atom Transfer (HAT) for Aliphatic C–H Bonds Elaboration. Chem. Rev 2022, 122, 1875–1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Tong Y; Bladt E; Aygüler MF; Manzi A; Milowska KZ; Hintermayr VA; Docampo P; Bals S; Urban AS; Polavarapu L; Feldmann J. Highly Luminescent Cesium Lead Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals with Tunable Composition and Thickness by Ultra-sonication. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2016, 55, 13887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Shaikh M; Rubalcaba K; Yan Y. Halide Perovskite Induces Halogen/Hydrogen Atom Transfer (XAT/HAT) for Allylic C–H Amination. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2024, 64, No. e202413012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published articles and its online Supporting Information.