Abstract

Biomolecular condensates formed by intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) are semidilute solutions. These can be approximated as solutions of blob-sized segments, which are peptide-sized motifs. We leveraged the blob picture and molecular dynamics simulations to quantify differences between inter-residue interactions in model compound and peptide-based mimics of dense versus dilute phases. The all-atom molecular dynamics simulations use a polarizable forcefield. In model compound solutions, the interactions between aromatic residues are stronger than interactions between cationic and aromatic residues. This holds in dilute and dense phases. Cooperativity within dense phases enhances pairwise interactions leading to finite-sized nanoscale clusters. The results for peptide-based condensates paint a different picture. Backbone amides add valence to the associating molecules. While this enhances pairwise inter-residue interactions in dilute phases, it weakens pair interactions in dense phases, doing so in a concentration-dependent manner. Weakening of pair interactions enables fluidization characterized by short-range order and long-range disorder. The higher valence afforded by the peptide backbone generates system-spanning networks. As a result, dense phases of peptides are best described as percolated network fluids. Overall, our results show how peptide backbones enhance pairwise interactions in dilute phases while weakening these interactions to enable percolation within dense phases.

Subject terms: Protein folding, Biophysical chemistry, Networks and systems biology, Molecular dynamics

Biomolecular condensates formed by intrinsically disordered protein condensates are known to be semidilute solutions, however, the molecular interactions in the dilute versus dense phases remain underexplored. Here, the authors use all-atom simulations based on a polarizable forcefield to understand the difference between protein sidechain interactions in dilute versus dense phases of protein-based condensates, revealing that strong inter-sidechain interactions are attenuated by backbone-mediated effects.

Introduction

Phase separation of proteins and nucleic acids leads to the formation of biomolecular condensates1. In a two-component system comprising a protein and solvent, phase separation yields two coexisting phases, namely, a dilute phase that is deficient in protein and a coexisting dense phase that is enriched in protein2. Intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) of proteins with specific sequence characteristics can be drivers of protein phase separation3,4. Of relevance to condensates such as stress granules and P-bodies are IDRs known as prion-like low complexity domains (PLCDs)5–7. The sequence determinants of driving forces for phase separation of PLCDs have been the topic of several studies4,8–25.

Recently, Bremer et al. quantified the temperature-dependent driving forces for phase separation of ~40 different sequence variants of A1-LCD, which is the PLCD from hnRNP-A125. At a given temperature away from the critical point, each A1-LCD variant is defined by a saturation concentration csat, which is the threshold concentration for phase separation. Lower values of csat imply stronger driving forces for phase separation and vice versa. The temperature-specific values of csat were found to be governed by: (i) the number and types of aromatic residues (Phe versus Tyr), which are uniformly distributed along the linear sequence8,26; (ii) the context-dependent contributions of arginine residues; (iii) the types of polar residues, which in PLCDs appear to function as weakly attractive spacers that are interspersed between aromatic and Arg stickers that contribute weaker attractions, but play direct and important roles as enablers of phase separation; (iv) the destabilizing effects of lysine residues that interfere with π-π interactions; and (v) the contributions of net charge per residue. Away from the critical temperature, changes to sequence features can lead to changes in temperature-specific values of csat that can span 4–5 orders of magnitude25. While the material properties of dense phases formed by variants of A1-LCD, specifically the measured and computed viscosities, show a clear inverse correlation with csat27, the concentrations within dense phases vary by less than a factor of two. These findings suggest that the material properties of dense phases and the values of csat are governed primarily by the free energy of transfer of PLCDs from dilute to dense phases22. And yet, computations that rely on the network structure within condensates help explain measured viscoelastic moduli27,28. These results pose a paradox. They suggest that interactions in dilute versus dense phases must be very different from one another29, even though they are thermodynamically linked via the establishment of phase equilibria.

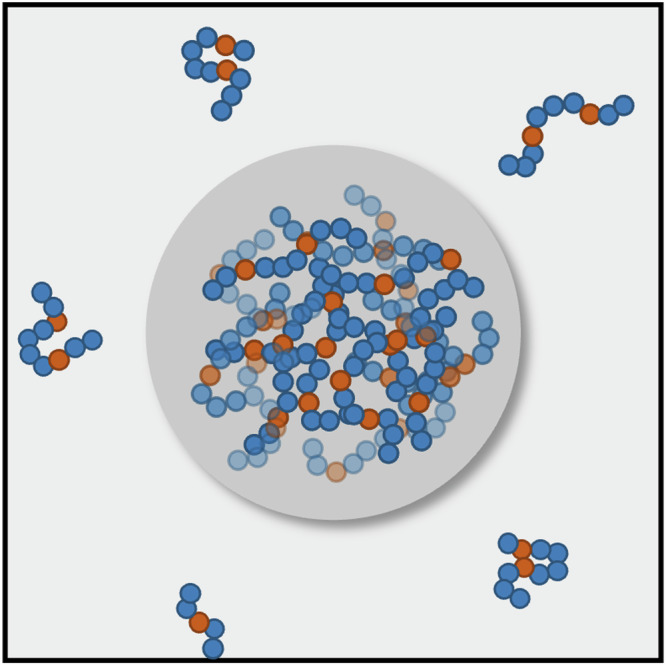

Dense phases of PLCDs and other systems are equivalent to semidilute solutions of flexible linear polymers (Fig. 1)10,25. This designation is based on the concentrations within dense phases being above the overlap concentration and well below the values expected for a polymer melt. Furthermore, several simulations and recent measurements have shown that the sizes (radii of gyration and mean end-to-end distances) of IDRs are expanded within condensates when compared to coexisting dilute phases8–10,30–37. The excluded volumes appear to be positive within condensates, and this suggests that condensate interiors are good solvents or at least better than theta solvents for which the excluded volume is zero9,10,38. For systems such as A1-LCD and a series of sequence variants, the radii of gyration within dense phases change minimally with temperature10. The measured concentrations within dense phases also change minimally, by less than a factor of two, across the entire temperature range that approaches the critical point10,25. Taken together, it can be argued that condensate interiors are athermal and or good solvents for systems such as PLCDs and related systems38,39.

Fig. 1. Dense phases of protein-based condensates are semidilute solutions of flexible linear polymers10.

Here, the bulk volume fraction of polymers is at or larger than the overlap volume fraction. The overlap volume fraction is defined as the ratio of the occupied volume of the polymer chain vmonoN to the pervaded volume V, where N is the number of monomers in one polymer chain and vmono is the occupied volume of one chemical monomer. V is estimated as R3, where R is the size of the chain. The blue spheres denote spacers, and the orange spheres denote stickers.

In semidilute solutions of flexible polymers in good or athermal solvents, the polymer mass concentration c is at or above the overlap mass concentration c*29. This allows the use of the concept of concentration blobs that was introduced by de Gennes40. Each polymer is viewed as a chain of blobs. The size ξc of a blob scales as gc3/5, where gc is the number of residues within a blob. Beyond the blob, chain sizes in semidilute solutions scale as (n/gc)1/2, where n is the number of residues in the chain. Correlations among blobs decay as (c/c*)-3/4. Importantly, values of gc do not depend on n39,41. Instead, they depend purely on the excluded volume, vex41. In an athermal solvent, vex is at its upper limit, and gc = 1. Given published results10,25,38, vex appears to be near the upper limit, and hence gc is O(1). Accordingly, as a zeroth-order approximation, one can approximate dense phases as fluids of peptide-sized segments in aqueous solvents42.

Here, we leverage the blob picture and report results from molecular dynamics simulations for capped amino acids (1 < gc < 2) and for capped tripeptides (3 < gc < 4). Peptides encompass backbone amides and sidechains. To dissect the contributions of backbones and sidechains, we compared the interactions of systems comprising sidechains alone to systems comprising backbones and sidechains. In the all-atom, molecular dynamics simulations, we investigated the concentration dependence of the strengths of effective pairwise interactions among functional groups that are known to be important as drivers of phase separation of PLCDs and other systems8–10,25,27,38,43,44. Specifically, our simulations quantify the strengths of interactions among aromatic and cationic residues in mimics of dilute versus dense phases. Volume fractions of sidechain model compounds between 0.002 and 0.003 were used to mimic the dilute phase, whereas volume fractions between 0.08 and 0.09 mimic the dense phase. In polymer science, volume fractions are the preferred measures of concentrations45, whereas biochemists use molar units or mass concentrations. The mass concentration values for each of the systems we studied are shown in Table S1 of Supplementary Data 1.

For the simulations, we used the polarizable forcefield, AMOEBA46–48 (Atomic Multipole Optimized Energetics for Biomolecular Applications), which has been parameterized using high-level quantum calculations, validated extensively, and widely used to: (a) investigate protein conformational changes; (b) examine ion solvation49; (c) model the structural and thermodynamic properties of water50,51; (d) compute hydration free energies of peptides and small molecules52; (e) obtain absolute and relative alchemical free energies53; (f) simulate protein conformational equilibria54–56; (g) perform free energy calculations of protein-ligand binding54,57,58; (h) simulate DNA aptamers with ligands59; (i) calculate electric fields in liquid solutions; and (j) model RNA hybridization57. For our work, we used the AMOEBA parameters for protein atoms, water molecules, and solution ions46.

Structural studies based on super-resolution microscopy have shown that dense phases feature spatial inhomogeneities defined by nanoscale hubs that coexist with dispersed molecules creating networks of meshes of different length scales29,60. These findings are concordant with inferences from lattice-based simulations10,60. Inhomogeneities in condensate interiors are manifest as nanoscale clustering of macromolecules and this is enabled by physical crosslinking10,28. The internal dynamics of clusters and dispersed molecules reflect the making and breaking of crosslinks on disparate timescales28,60. Recent studies have also pointed to condensates having distinct chemical and electrochemical environments12. Furthermore, THz measurements revealed the presence of two types of water populations within condensates61. These populations are governed by the types of species that are being hydrated. Structural and solvation inhomogeneities within condensates have been used in direct computations and explanations of condensate viscoelasticity27,28,62–68. In light of these emerging findings and given that condensates are likely to be inhomogeneously organized and heterogeneously crowded, we used a polarizable forcefield to allow for the ability to capture first-order electrostatic responses that cannot be captured using non-polarizable forcefields. Our results show that even though the thermodynamic inferences do not qualitatively change vis-à-vis non-polarizable forcefields, there is a material impact on the self-diffusion coefficient of water molecules. These results are consistent with findings from THz measurements and other reports61,69.

The design of our simulations is as follows: For different pairs of amino acid sidechains, we performed two sets of simulations. In the first set, we used model compound mimics of specific amino acid sidechains (Fig. 2A) to compute potentials of mean force (PMFs) and quantify the free energies of association/dissociation between functional groups of sidechains. To assess dilute phase interactions among distinct motifs, we computed PMFs between pairs of model compounds in a cubic box of volume ~125 nm3. Each model compound represents a specific amino acid sidechain. To quantify interactions among sidechains in dense phases, we computed PMFs from simulations of mixtures of model compounds as a function of concentration.

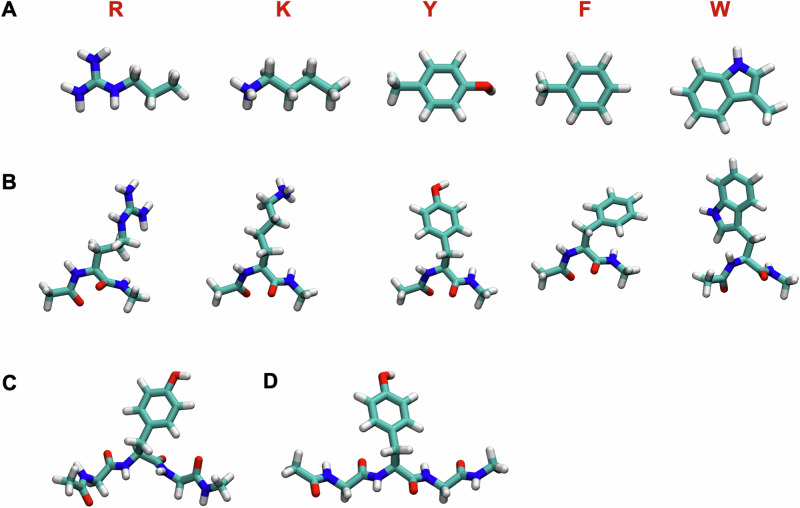

Fig. 2. Model compounds and capped amino acids used to compare interactions between pairs of polypeptide units in mimics of dilute versus dense phases.

A Five model compounds n-propylguanidine (R′), 1-butylamine (K′), p-Cresol (Y′), toluene (F′), and 3-methylindole (W′) that mimic the sidechains of Arg, Lys, Tyr, Phe, and Trp, respectively. B Drawings of capped amino acids, N-acetyl-Xaa-N′-methylamide for Xaa ≡ Arg, Lys, Tyr, Phe, and Trp, respectively. Each of these systems features two peptide units and one pair of backbone ϕ and ψ angles. We also performed simulations for a fully flexible tripeptide C N-acetyl-Gly-Tyr-Gly-N′-methylamide GYG and D the tripeptide N-acetyl- Gly-Tyr-Gly -N′-methylamide restrained to be in an extended conformation.

In a second set of simulations, we computed inter-sidechain PMFs using dilute and dense phase simulations of capped amino acids (Fig. 2B). Here, a capped amino acid Xaa refers to the molecule N-acetyl-Xaa-N′-methylamide, where Xaa is the amino acid residue of interest. Each capped amino acid features two peptide units, and a pair of unrestrained backbone ϕ and ψ angles. Tripeptides were also used to test sequence context effects and conformational contributions (Fig. 2C, D). Comparative assessments of the simulations of model compound solutions and those of capped amino acids and tripeptides help us query the concentration-dependent effects of backbone peptide units and local sequence contexts on the strengths of sidechain interactions.

Results

PMFs in the dilute phase follow well-defined hierarchies

We computed dilute phase PMFs for pairs of model compounds that mimic the following interactions: Phe–Phe, Tyr–Tyr, Trp–Trp, Arg–Phe, Arg–Tyr, Arg–Trp, Lys–Phe, and Lys–Tyr. The model compounds that mimic sidechains of Arg, Lys, Tyr, Phe, and Trp are n-propylguanidine (R′), 1-butylamine (K′), p-Cresol (Y′), toluene (F′), and 3-methylindole (W′), respectively (Fig. 2A). These model compounds were chosen because they are the dominant drivers or destabilizers of PLCD phase separation9,10,25.

For the dilute phase, we computed PMFs for different pairs of model compounds using umbrella sampling. Volume fractions of sidechain model compounds between 0.002 and 0.003 were used to mimic the dilute phase. Each pair was solvated in a cubic box of water and solution ions, ~5 nm to a side, with periodic boundary conditions. The reaction coordinate chosen for umbrella sampling was the distance between specific atoms on functional groups of each model compound. For R′ and K′, the chosen atoms were the carbon atom in the guanidium group of Arg and the nitrogen atom in the amine of Lys. For Y′, F′, and W′, we used the geometric center of the aromatic ring to define the reaction coordinate.

The PMFs for each of the six model compound pairs are shown in Fig. 3A–C. The PMF for Y´-Y´ shows two minima at ~3.6 and ~5.0 Å, respectively (Fig. 3A). These minima correspond to two different interaction modes, namely the stacked structure and T-shape structure (Supplementary Data 1 and Fig. S1). The locations of these minima are consistent with results reported for benzene dimers using high-level quantum calculations70. The PMFs for F′-F′ and W′-W′ have one minimum each, with the minimum at ~5.0 Å for F′-F′ corresponding to the T-shaped structure, and the minimum at ~3.6 Å for W′-W′ corresponding to the stacked structure (Fig. 3A). The dominant minima in PMFs for R′-Y′, R′-F′, and R′-W′ appear at a separation of ~3.6 Å and this corresponds to stacked structures formed by the planar guanidinium group and the rings of the aromatic groups (Supplementary Data 1 and Fig. S2). These structures are consistent with reports of interactions between Arg and aromatic residues being of cation-π-π flavor71. We also computed PMFs for K′-Y′ and K′-F′. These interactions are essentially negligible when compared to those of R′-Y′ and R′-F′ (Fig. 3C).

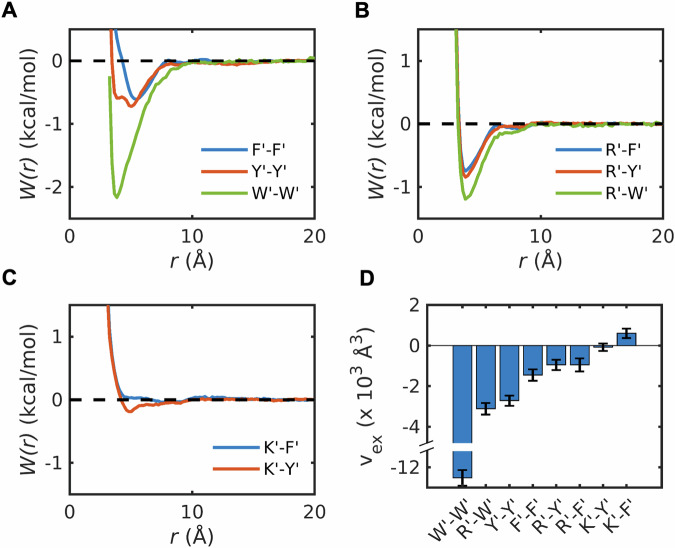

Fig. 3. PMFs computed for pairs of model compound mimics of sidechains.

PMFs, W(r), for interactions between π systems A Phe, Tyr, and Trp, B Arg-π systems, and C Lys-π systems. The model compounds that mimic sidechains of Arg, Lys, Tyr, Phe, and Trp are represented by R′, K′, Y′, F′, and W′, respectively. D Each of the pairwise PMFs can be used to compute pair-specific excluded volumes (vex), as described in the text. The estimation of error bars of the excluded volume is described in the Methods section.

To enable a single-parameter comparison of the strengths and types of pairwise interactions, we computed excluded volumes (vex) by integrating the Mayer f-function45. For this, we calculated . Here, is the PMF for pairwise interactions computed from the simulations, and 4πr2dr is the volume element. The value of vex, which quantifies the volume excluded for interactions with the solvent45,72, is the two-body interaction coefficient between a pair of moieties in a solvent, and it is directly proportional to the second virial coefficient2,45. A negative value implies that the interactions are, on average, attractive, whereas positive values imply net repulsions. The magnitude of vex quantifies the strength of the attraction or repulsion.

The values of vex computed using the PMFs are shown in Fig. 3D. The strengths of attractive attractions, quantified by negative values of vex, follow the hierarchy W′-W′ > R′-W′ > Y′-Y′ > F′-F′ > R′-Y′ > R’-F′. The vex values for K′-Y′ and K′-F′ are near zero (K′-Y′) or positive, albeit small (K′-F′), implying that these interactions are negligible or slightly repulsive. These results align with experiments demonstrating that R′-Y′ interactions are stronger than R′–F′ interactions and K′–Y′ interactions4,8,25,43,44,73. Note that the direct interactions between water molecules and model compounds are weaker than the solvent-mediated pair interactions between model compounds (Supplementary Data 1 and Fig. S3).

Next, we computed dilute phase PMFs between pairs of capped amino acids along reaction coordinates that are identical to those for model compounds (Fig. 4). The reaction coordinates were identical to those used for model compounds. This enables a one-to-one correspondence between the results obtained from the two different sets of simulations.

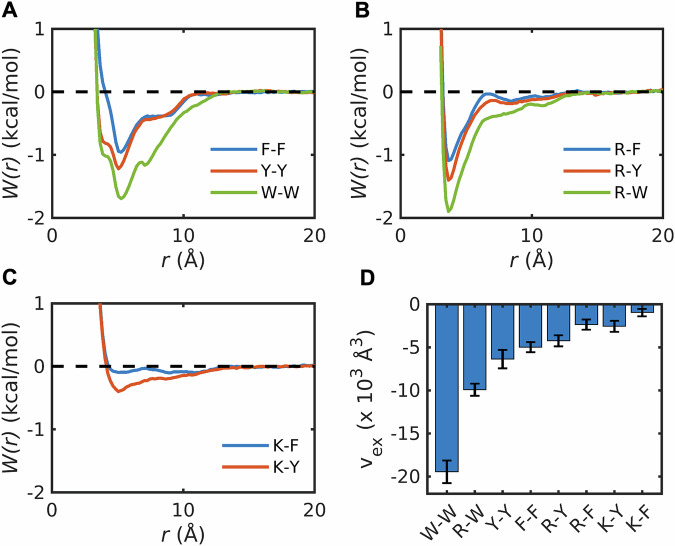

Fig. 4. Interactions between sidechains are enhanced by the presence of backbone peptide units in the dilute phase.

PMFs, W(r), for A π-π, B Arg-π, and C Lys-π interactions between pairs of capped amino acids. D The pairwise PMFs in panels (A–C) were used to compute pair-specific excluded volumes (vex). The estimation of error bars of the excluded volume is described in the Methods section.

Although the locations of minima remain the same as those for model compounds, the well depths increase for all sidechain pairs. Additionally, auxiliary minima appear at separations of ~8.5 Å for all pairs. These point to backbone-mediated, long-range contacts between functional groups of sidechains that are absent for model compounds. Although backbones enhance the overall interaction strengths between sidechains, the overall hierarchy remains the same, as can be seen by comparing the excluded volumes in Fig. 4D to those in Fig. 3D. To quantify the influence of backbones on the interactions between sidechains, we calculated . This refers to the difference between PMFs for capped amino WAA(r) and those for model compounds (Supplementary Data 1 and Fig. S4). These comparisons show that backbone-mediated interactions enhance the attraction between sidechains in dilute phases.

Next, we quantified the entropic and enthalpic contributions to the PMFs. The potential energy was used as the proxy for enthalpy, and its averaged value was plotted as a function of the distance r (Supplementary Data 1 and Fig. S5). Despite significant fluctuations, the results show that entropy is favorable at short range within 10 Å for W–W and F–F interactions. These findings highlight the importance of hydrophobic hydration to the association of aromatic rings and align with the findings reported by Grimme74 as well as Martinez and Iverson75. Both studies propose that the π-π stacking among small aromatic rings, that is observed in high-resolution structures, should be used as a geometrical description rather than as a marker of special interactions compared to those between saturated hydrocarbon rings. They also showed that the interaction strengths of π-π stacking among small aromatic rings are almost identical to those between saturated hydrocarbon rings of similar size. For other pairs, enthalpy dominates the interactions at distances r < ~4 Å.

Model compounds form nanoscale clusters within dense phases

Next, we quantified the effective pairwise interaction strengths among sidechains in dense phase mimics made up of model compounds. In these simulations, the volume fractions of sidechains are more than an order of magnitude larger than in the dilute phase, ranging from 0.08 to 0.09. These values correspond to measured volume fractions of sidechains that place PLCD-like systems in two-phase regimes25. We performed seven separate simulations for systems comprising different numbers of: R′ and F′, R′ and Y′, R′ and W′, respectively. For each pair, we performed two or three sets of simulations. In 1:1 mixtures, the simulations comprised 40 R and 40 F′/Y′/W′ molecules (Fig. 5A). In 2:1 mixtures, the simulations comprised 53 R′ and 27 F′/Y′ molecules (Fig. 5B). Finally, in 1:2 mixtures, the simulations comprised 27 R′ and 53 F′/Y′ molecules (Fig. 5C).

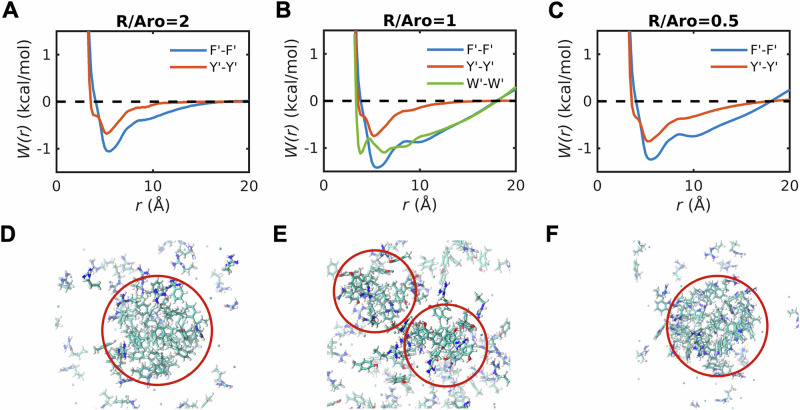

Fig. 5. Strengths of interactions between aromatic groups are enhanced in dense phases of model compounds.

A PMFs, W(r), for F′-F′ and Y′-Y′ in 2:1 mixtures of R′ and F′, and. Each mixture includes 53 R′ and 27 aromatic (either F′ or Y′) sidechains. B W(r) for F′-F′, Y′-Y′, and W′-W′ in 1:1 mixtures of Arg model compound with each aromatic model compound. Each mixture includes 40 Arg and 40 aromatic (either F′, Y′, or W′) model compounds. C W(r) for F′-F′ and Y′-Y′ in 1:2 mixtures of Arg model compound with each aromatic model compound. Each mixture includes 27 Arg and 53 aromatic (either F′ or Y′) model compounds. Snapshots of nanoscale clusters that are formed in 1:1 mixtures of R with D F′, E Y′, and F W′.

When compared to the dilute phase PMFs (Fig. 3A), the PMFs for the dense phase mimics (Fig. 5A–C) show the following trends: The energetics for Y′–Y′ interactions change the least, with the only substantive change being the increased preference for T-shaped structures. When the R′:Y′ ratio is 2:1 and 1:1, the PMFs converge to zero for separations between 10 and 15 Å. This indicates an absence of long-range ordering in R′-Y′ mixtures (Fig. 5A–C). However, when the R′:Y′ ratio is 1:2, then we observe long-range ordering that goes beyond 20 Å.

The PMFs for F′-F′ change both qualitatively and quantitatively. When compared to the dilute phase PMFs (Fig. 3A), the T-shaped structures have higher stability in dense phases. Additionally, we observed long-range, non-random organization for 1:1 and 2:1 ratios of R′:Y′ (Fig. 5A, C). This is indicative of clustering on the nanometer scale. Increasing the R′:F′ ratio weakens the preference for T-shaped structures and long-range ordering (Fig. 5B). Decreasing the R′:F′ ratio has the opposite effect (Fig. 5C).

In R′:W′ mixtures, the PMF for W′–W′ interactions show an equivalent preference for stacked and T-shaped structures (Fig. 5A), which is different from the PMFs in the dilute phase (Fig. 3A). This weakens the preference for stacked structures when compared to the dilute phase. In addition to the equivalent preferences of stacked and T-shaped structures, the 1:1 R′-W′ mixtures show the long-range ordering as we observed for R′-F′ mixtures. Snapshots derived from simulations of 1:1 mixtures show the formation of nanoscale clusters of aromatic moieties in R′-F′ (Fig. 5D) and R′-W′ (Fig. 5F) mixtures, and weaker clustering in R′-Y′ mixtures (Fig. 5E).

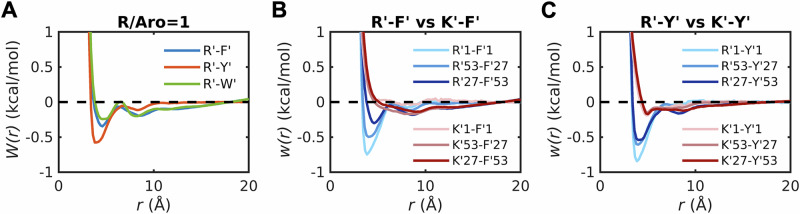

The weakened clustering of aromatic moieties in R′-Y′ mixtures can be rationalized by comparisons of the R′-Y′, R′-F′, and R′-W′ PMFs. The minimum, which corresponds to stacked structures of the guanido group and aromatic moieties, is most pronounced in R′-Y′ mixtures and is weaker in R′-F′ and R′-W′ mixtures (Fig. 6A). The extent to which R′–F′ interactions are weakened depends on the R′:F′ ratio, becoming more pronounced as this ratio decreases (Fig. 6B). In contrast, the R′–Y′ interactions, although destabilized when compared to the dilute phase, are insensitive to changes in the R′:Y′ ratio in dense phase mimics (Fig. 6C). These results suggest a correlation between stronger R′-Y′ interactions and weaker clustering of Tyr mimics, whereas the converse is true for R′-F′ and R′-W′ mixtures. In contrast to R′-F′ and R′-Y′ mixtures, the interactions in K′-F′ and K′-Y′ mixtures are such that interactions are either negligible (K′-F′, Fig. 6B) or weakly attractive (K′-Y′, Fig. 6C). These interactions in dense phases, which do not depend on concentration or the K′:F′/K′:Y′ ratios, resemble what is observed in dilute phases (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 6. Comparative strengths of cation-π interactions in dense phases with different ratios of R′, K′ and aromatic (Aro) groups.

A PMFs, W(r), for R′-F′, R′-Y′, and R′-W′ in 1:1 mixtures of R′ with each aromatic model compound. Each mixture includes 40 R′ molecules and 40 molecules of one of F′, Y′, or W′. B Comparison of R′-F′ and K′-F′ in different dense phases. R′1-F′1 and K′1-F′1 denote W(r) for R′-F′ and K′-F′ in the dilute phase calculated from umbrella sampling. The other legends denote W(r) in mixtures containing different numbers of model compounds mimicking Arg and aromatic sidechains. In the legend, R′53-F′27 refers to PMFs extracted from simulations of dense phases with 53 R′ and 27 F′ molecules. Conversely, R′27-F′53 refers to PMFs extracted from simulations of dense phases with 27 R′ and 53 F′ molecules. A similar convention is applied for PMFs computed in dense phases with different mixtures of K′ and F′ molecules. C Comparison of R′-Y′ and K′-Y′ in different dilute and dense phases. Conventions for the legends are the same as those in panel (B).

We also explored the influence of total model compound concentration while maintaining a 1:1 ratio of n-propylguanidine to aromatic moieties (Supplementary Data 1 and Fig. S6). The effects we observed for Y′–Y′, F′–F′, R′–Y′, and R′–F′ interactions (Figs. 5, 6) become more pronounced with increasing concentration (Supplementary Data 1 and Fig. S6). Nanoscale clusters of Tyr moieties, which are absent at lower concentrations, are evident in mixtures with 60 R′ and 60 Y′ molecules. This implies that the formation of nanoscale aromatic clusters is a generic feature of dense solutions with aromatic molecules. However, the specificity of cluster formation, which depends on the solvent- and mixture-mediated strengths of associations among aromatic moieties, will be manifest in the concentration dependence of cluster formation.

Pair interactions are weakened in dense phases of capped amino acids

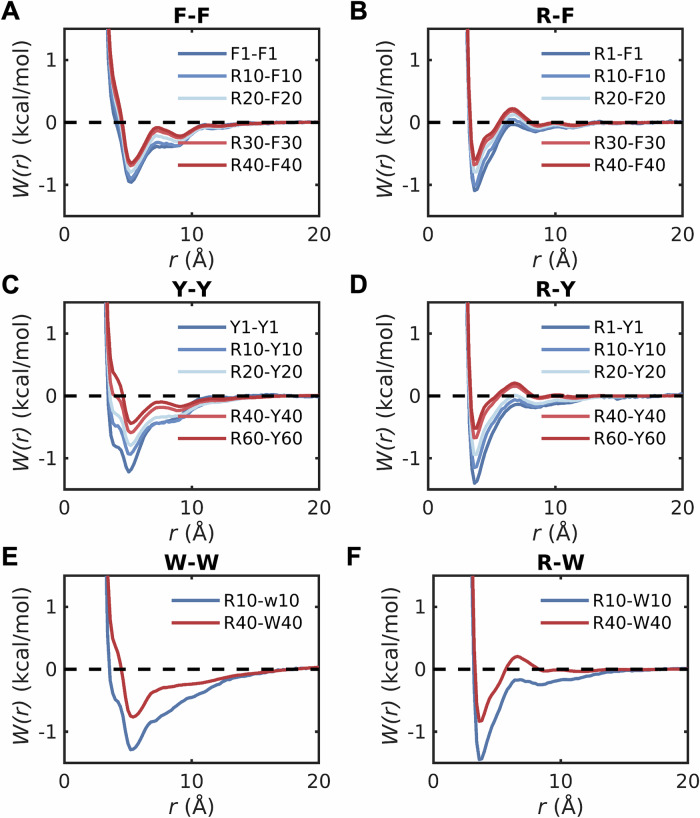

Next, we performed simulations for mixtures of capped amino acids to compute pairwise PMFs for 1:1 mixtures of dense phase mimics of different combinations of capped Arg and aromatic residues (Fig. 7). In all cases, we observed a weakening of pairwise associations and the extent of weakening increases within increasing concentrations. Furthermore, the pairwise PMFs for F-F, Y-F and W-W (Fig. 7A, C, E) do not show the long-range ordering that was observed for mixtures of model compounds (Fig. 5 and Fig. S6).

Fig. 7. Contributions from backbone peptide units weaken sidechain interactions within dense phases.

Comparisons of potentials of mean force W(r) in dilute versus dense phases for pairs of capped amino acids A F-F, B R-F, C Y-Y, D R-Y, E W-W, and F R-W. The number in the legends denotes the amount of capped amino acids indicated by the preceding letter in the mixture mimicking dense phases. F1-F1, Y1-Y1, R1-Y1, and R1-Y1 denote the potential of mean force in the dilute phase calculated from umbrella sampling. The interactions are weakened as increasing the concentration of amino acid stickers.

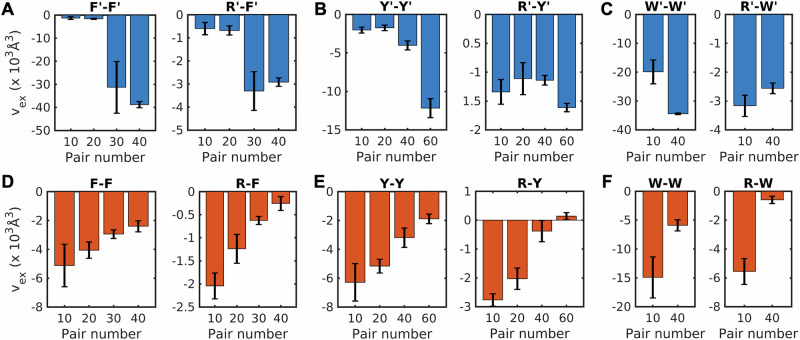

The information contained in the different pairwise PMFs is summarized by computing pair-specific values of vex for different concentrations of 1:1 mixtures of Arg and aromatic moieties in dense phase mimics based on model compounds (Fig. 8A-C) or capped amino acids (Fig. 8D-F). For the F-F, Y-Y, and W-W pairs, the magnitudes of vex increase in dense phase mimics that are based on the use of model compounds. However, for the same pairs of sidechains, the magnitudes of vex decrease with increasing concentrations of capped amino acids. Similar trends prevail when comparing the excluded volumes for pairwise associations of Arg and Tyr, Phe, or Trp (see Fig. 8A versus D). Overall, the pairwise associations are weakened, long-range attractions are lost, and nanoscale clusters are absent in dense phases of capped amino acids. The implication is that while the peptide unit enhances and maintains the hierarchy of pairwise associations observed in dilute phases, the interactions are fundamentally altered in dense phases. We asked if the weakening of pairwise associations is offset by a gain in sidechain-backbone or backbone-backbone pairwise associations. Analysis of the pair PMFs that quantify these pairwise associations show the same trends we observed for sidechain interactions (Supplementary Data 1 and Fig. S7). Furthermore, we found that the stoichiometry of Arg versus aromatic residues does not alter the PMFs for capped amino acids (Supplementary Data 1 and Fig. S8). This points to the robustness of the weakening of pairwise associations caused by the backbone-mediated interactions.

Fig. 8. Pairwise interactions among sidechains are weakened in dense phases of amino acids.

Excluded volumes (vex) for pairwise interactions of model compounds (A–C) and capped amino acids (D–F). A F′-F′ and R′-F′ in a 1:1 mixture of Arg and Phe model compounds, B Y′-Y′ and R′-Y′ in a 1:1 mixture of Arg and Tyr model compounds, and C W′-W′ and R′-W′ in 1:1 mixture of Arg and Trp model compounds. D F-F and R-F in a 1:1 mixture of Arg and Phe capped amino acids, E Y-Y and R-Y calculated in a 1:1 mixture of Arg and Tyr capped amino acids, and F W-W and R-W in a 1:1 mixture of Arg and Trp capped amino acids. The X-axis represents the number of pairs of Arg and aromatic stickers in the mixture. The estimation of error bars of the excluded volume is described in the Methods section.

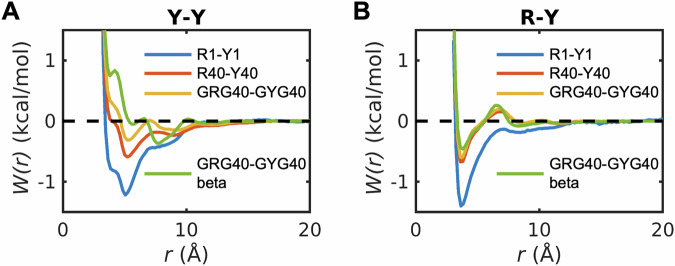

Next, we tested the effects of longer peptides on pairwise associations between Arg and aromatic residues, specifically Tyr. In PLCDs, aromatic residues are uniformly distributed along the linear sequence26. Motifs such as GYG and GRG are common in PLCDs25. Accordingly, we computed pair PMFs, with Arg–Tyr distances as the reaction coordinates, for two different combinations of capped GYG and GRG tripeptides. In one set of simulations, the backbone conformations were unrestrained. In the other set of simulations, the four pairs of backbone ϕ and ψ angles were restrained in extended β-strand-like conformations with values of ϕ = –140° and ψ = +135°.

The PMFs for Y-Y associations computed in dense phase mimics with 40 GRG and 40 GYG peptides were compared to the PMFs for capped Arg and Tyr in dilute versus dense phases (Fig. 9A). For the unrestrained pairs of tripeptides, the PMFs share the same profiles as those for capped amino acids, but the interactions are weakened in comparison. Restraining the backbone conformations, elicits a substantial entropic penalty, and this weakens pairwise associations between Tyr residues (Fig. 9A). In all PMFs, the locations of stacked and T-shaped structures stay invariant, whereas the minimum corresponding to backbone-mediated associations, located at ~8.5 Å for capped amino acids and unrestrained tripeptide, shifts to ~7.5 Å for the restrained tripeptides. The PMFs that quantify R-Y associations are equivalent between capped amino acids and tripeptides (Fig. 9B).

Fig. 9. Influence of stoichiometry of cationic versus aromatic amino acids and backbone flexibility on pairwise interactions between capped amino acids.

The potential of mean force for A Y-Y and B R-Y in mixtures including capped Arg and Tyr. The legends denotes the numbers of capped amino acids indicated by the preceding letter in the mixture mimicking dense phases. Y1-Y1 and R1-Y1 denote the potential of mean force in the dilute phase calculated from umbrella sampling. While the total concentration remains the same, the stoichiometry of cationic vs. aromatic stickers does not affect the effective pairwise interactions between capped amino acids in the dense phase (Fig. S8). The potential of mean force for A Y-Y, and B R-Y in mixtures including capped tripeptides GRG and GYG. The red curve denotes results when the backbone of the tripeptide is constrained in the region where .

The totality of the results presented to this point suggests that the strengths of pairwise associations and long-range ordering due to strong pair interactions between aromatic residues are weakened by backbone-mediated effects. The loss of long-range ordering points to the fluidizing effects of backbone-mediated interactions. The computed pair associations are suggestive of two possibilities, namely, a constraint and an emergent property. If two-body interactions are the main drivers of phase separation, which is true in the mean-field regime away from the critical point,76, then transferring peptides or proteins into dense phases should come with an upper bound on the concentration within dense phases that is well below that of a melt and considerably closer to that of a semidilute solution77. Otherwise, the transfer of free energy from the dilute to the dense phase would be unfavorable. This constraint emerges from our calculations, which show that as the volume fraction increases, the values of vex become less negative and smaller in magnitude compared to the dilute phase values. Additionally, interactions beyond pairwise associations78 are likely to contribute to interactions within dense phases29,79. This point has been underscored recently to explain why compositionally distinct phases are likely to be determined by the contributions of three-body and higher-order interactions80.

We investigated the contributions of higher-order interactions by quantifying the degree of clustering through connectivity81, which is the basis for forming network fluids via directional interactions whereby molecules can be viewed as multivalent nodes connected to other molecules via edges on a graph42,82. This analysis was prompted by the fact that each peptide unit contributes at least one hydrogen bond donor and acceptor. Accordingly, the valence increases by four for capped amino acids and by eight for capped tripeptides. Note that in mean field models of percolation, which are valid in semidilute solutions, any valence above three is sufficient to generate a percolated network2,42,45,72,82. At or below a valence of three, small clusters can form, but they cannot grow into system-spanning networks72.

Dense phase mimics modeled using capped amino acids form percolated network fluids

We asked if the weakening of pairwise interactions and loss of long-range ordering in dense phases mimicked using capped amino acids are offset by a gain in higher-order interactions in the form of higher-order clusters and networks that span the entire system. To answer this question, we performed an analysis of the connectivity of molecules within dense phase mimics formed by capped amino acids42,81–83. The analysis follows the recent work of Dar et al.82. Two molecules were considered connected if any of the distances between specific atoms or groups is smaller than a prescribed cutoff. The pairwise distances used to compute connectivity were divided into three groups: (1) sidechain-sidechain, (2) sidechain-backbone, (3) and distances between backbone amide nitrogen and backbone carbonyl oxygen atoms. The inter-sidechain distances include those between aromatic rings, between guanidinium groups, and between the aromatic ring and guanidinium group. The sidechain-backbone distances include those between aromatic ring and terminal CH3 groups, between the aromatic ring and backbone carbonyl oxygen atoms, and between the guanidinium group and backbone carbonyl oxygen atoms. The geometric centers of carbon atoms in the aromatic ring, the nitrogen atom in the guanidinium group, and the carbon atom in the terminal CH3 group were used to calculate these distances. Following ref. 82 the first minimum of the radial distribution function for a specific pair of atoms or groups was chosen as the distance cutoff to determine the connectivity. The values for these distance cutoffs are shown in Supplementary Data 1 and Table S2. If molecule A is connected to molecules B and C, then molecule B and C are also connected via transitive closure84. All connected molecules make up a cluster. We used this connectivity analysis to define the cluster size as the number of molecules within a cluster. We also defined the cluster dimension as the maximum distance between alpha carbon atoms within the cluster85. For the cluster with only one molecule, we set the cluster dimension to be zero.

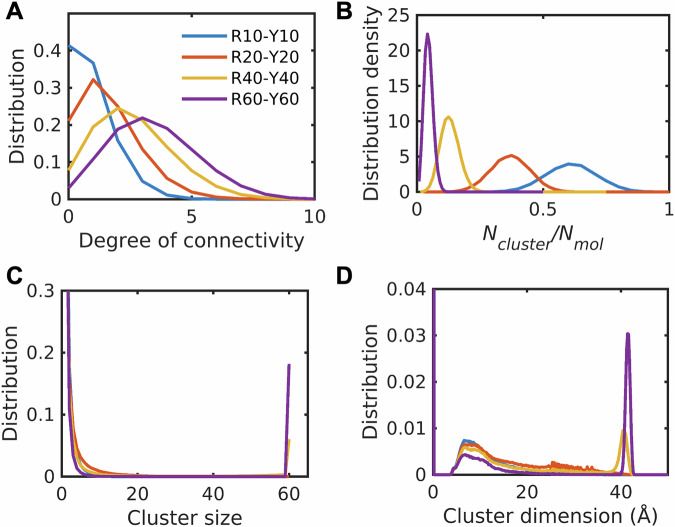

Results from the connectivity analysis are shown in Fig. 10. The degree of connectivity, which quantifies the connectedness of a molecule within the dense phase, shows a monotonic increase with increasing concentration (Fig. 10A). Percolation is a continuous transition42,86, above a threshold, the connectivity increases to span the entire system. The monotonic increase in the extent of clustering is also evidenced in the distributions of the number of clusters per molecule (Fig. 10B). The distributions of cluster size show a bimodality at high concentrations (Fig. 10C), pointing to the incorporation of more than 75% of the molecules into the largest cluster. The largest cluster is system-spanning as evidenced by comparison to the maximum cluster dimension (Fig. 10D), which is equivalent to the dimension for the central simulation cell. The weakening of pairwise associations within dense phase mimics formed by capped amino acids is offset by the formation of higher-order connected clusters that become system-spanning at the highest concentrations. Unlike dense phases of capped amino acids, we do not observe system-spanning networks for dense phases made up of model compounds (Supplementary Data 1 and Fig. S9). Instead, these systems exhibit a lower degree of connectivity, smaller cluster dimensions, a higher number of clusters per molecule, and the absence of system-spanning networks. Taken together with the absence of long-range ordering, the findings suggest that backbone-mediated interactions drive the formation of a percolated network within dense phases82. This network has fluid-like characteristics defined by weakened pairwise associations, short-range order, and long-range disorder.

Fig. 10. Dense phases modeled using capped amino acids form percolated networks.

Distribution of degree of connectivity of each capped amino acid (A), distribution density of number of clusters per molecule (B), distribution of cluster size (C), and cluster dimension (D) within the dense phase. The degree of connectivity, cluster size, and cluster dimension increase with increasing concentration, whereas the number of clusters per molecule decreases.

Next, we analyzed the dynamics of contacts that form and break within percolated networks. First, the timescales of amino acid contacts were quantified using the survival probability, defined as the conditional probability that a contact that was observed at time t persists at time t+dt. The results are shown in Supplementary Data 1 and Fig. S10. The half-life of contact was determined as the time point where the survival probability equals 0.5. This defines a stochastic separatrix87 and the choice of 0.5 was inspired by the pfold order parameter that has been used in characterizations of transition state ensembles in protein folding simulations88,89. The calculated half-lives for Y-Y, R-Y, and R-R contacts are 0.48, 0.27, and 0.07 ns, respectively. These results indicate that Y–Y interactions have longer lifetimes than R–Y interactions, and these are stronger than R–R interactions. The half-lives extracted from survival probabilities are consistent with the PMFs. These results confirm that the contact lifetimes are determined by specific amino acid interactions rather than stochastic contacts that might be of higher likelihood at higher mass concentrations.

We also analyzed the temporal evolution of the network structure by analyzing how the average degree of connectivity and the largest cluster size vary as a function of time. Both the average degree of connectivity and the largest cluster size increase during the first 10 ns and then fluctuate around equilibrium values (Supplementary Data 1 and Fig. S11). These results demonstrate that beyond an equilibration/relaxation timescale of 10 ns, the network rearranges via an equilibrium flux of associations and dissociations.

Discussion

In this work, we used all-atom simulations based on the AMOEBA polarizable forcefield to quantify differences between pairwise associations of aromatic and cationic sidechains in mimics of dilute versus dense phases of peptide-based condensates. The design of the simulations leverages the fact that protein concentrations in dense phases place these systems in the semidilute regime90 that are at29 or above the overlap concentration9,10,29,91. These semidilute solutions are good or athermal solvents and hence the number of residues within a concentration blob should be close to one. This ensures that our results are directly relevant to condensates of IDPs.

For freely diffusing model compounds, the simulations show evidence of long-range ordering within dense phases that leads to the presence of nanoscale aromatic clusters and dispersed cationic compounds, ions, and water molecules. The hierarchies of interaction strengths are in accord with recent energy decompositions92. In our simulations, which are based on the AMOEBA forcefield54, the pairwise associations are enhanced in dense phases compared to dilute phases. In contrast, for simulations of capped amino acids, we find that backbone-mediated interactions weaken pairwise associations between sidechains. The strengths of pair associations decrease with increasing concentration. This would appear to place an upper bound on the concentrations within dense phases while enabling a loss of long-range ordering, and disruption of the nanoscale clusters of aromatic moieties. Fluidization is evident in the loss of long-range ordering. The increased valence afforded by the presence of peptide backbones, taken together with the concentration-dependent weakening of pairwise sidechain associations, helps drive the formation of system-spanning networks. These networks are defined by the totality of directional, sidechain–sidechain, sidechain–backbone, and backbone–backbone interactions.

Our simulations paint a new picture regarding the driving forces for phase separation of PLCD-like systems: Strong pairwise associations between sidechains are present in dilute phases, and these, as shown experimentally, are direct determinants of the free energy of transfer of polypeptides into dense phases25,74. The strengths of pairwise interactions are consistent with the designation of aromatic and Arg residues as stickers4,25,93. The intrinsic interaction energies are further enhanced in dense phase mimics based on model compounds, thus further corroborating the designation of these residues as stickers93,94. The favorable inter-residue two-body interactions outcompete chain–solvent interactions and the entropy of mixing, thereby driving phase separation95. However, within dense phases, the interaction patterns are different from the dilute phase. This is true for model compounds and for peptides. For model compounds, the lack of a backbone enables long-range ordering and the formation of nanoscale clusters that coexist with regions that are devoid of these clusters. Backbones interfere with this clustering by introducing extra valence that weakens pairwise associations between sidechain moieties. Weakening of pairwise associations is concentration-dependent, and it enables networking to drive percolation within dense phases. These observations are consistent with recent studies that have shown evidence for condensates being percolated network fluids with an apparent upper bound on protein concentrations within dense phases10,27,64,82,96,97.

Our studies lead to two key findings: First, the interactions within dilute and dense phases are quantifiably different and these differences are expected to be generators of interphase properties that include viscoelasticity27,28 and interphase electrochemical potentials12,98. Second, while dense phases of small molecules such as model compounds are likely to drive crystallization transitions99, as evidenced by the nanoscale clustering and apparent phase separation within dense phases of model compounds, the peptide backbone intervenes with competing directional interactions such as hydrogen bonds to fluidize dense phases.

To investigate changes to solvent properties between coexisting phases, we compared the induced dipole moments of water molecules in simulations of model compounds mimicking the sidechain of Tyr in both phases. We found that the dipole moments for water molecules in the dilute phase and dense phase are 2.71 ± 0.23 Debye, and are identical across the phase. We obtain a similar result for the static, induced dipole moment of water molecules, which is 2.65 ± 0.52 Debye in both phases. Differences between dense and dilute phases arise primarily from the effects of crowding in the dense phase. Notably, the extent of hydration of amino acids, quantified by analyzing water molecules around the amino acids, is diluted in the dense phase (Supplementary Data 1 and Fig. S12). Furthermore, the crowded environment influences the dynamics of water molecules. Specifically, the self-diffusion coefficient of water in the dense phase is . This is a factor of 1.6 smaller than what we compute in the dilute phase, which is (Supplementary Data 1 and Fig. S13). These results are consistent with the findings of Mukherjee et al.69, who showed that hydration waters have longer residence times around proteins in the dense phase.

In both dilute and dense phases, there is a clear hierarchy of pairwise interactions, and there is a positive correlation between these hierarchies. This explains why models100 based on transferrable100,101 or learned potentials9,10 that are pairwise in nature provide accurate descriptions of phase separation driven by homotypic and heterotypic interactions. Our dilute phase calculations are concordant with recent quantum mechanical energy decompositions92. However, there are specific deviations vis-à-vis inferences made based on PMFs computed using non-polarizable forcefields18,37. These studies use a reaction coordinate that is the center-of-mass between the compounds of interest, whereas we used distances between functional groups of sidechains. Our choice is motivated by the formal definition of stickers, which implicates directional interactions between functional groups93,95. Converting PMFs from simulations that use non-polarizable forcefields and centers-of-mass as the reaction coordinates, we derive, based on excluded volumes, the following interaction hierarchy in dilute phases: R-Y > Y-Y > R-F > F-F > K-Y > K-F. This contrasts with the hierarchies we derived from dilute phases of model compounds and capped amino acids, according to which: W′-W′ > R′-W′ > Y′-Y′ > F′-F′ > R′-Y′ > R′-F′ ≈ K′-Y′ > K′-F′. The key discrepancy pertains to the relative strengths of R–Y versus Y–Y and R–F versus F–F interactions. The calculations based on the AMOEBA forcefield, which includes electronic polarizability for water molecules, ions, and peptides, suggest that the effects of polarization make π-π interactions stronger than the Arg–π interactions. Our calculations are concordant with solubility data102, and inferences from experimental data, which show that π-π interactions are likely to be intrinsically stronger than cation–π interactions with the caveat that these effects are also context dependent4,9,10,15–17,25,42,103,104. It is noteworthy that the entropy-enthalpy decompositions suggest, in accord with ref. 74, as well as ref. 75, that π–π associations might be driven mainly by entropic considerations akin to what one observes for saturated, non-aromatic ring systems. They are also consistent with observations from THz spectroscopy61.

Our findings emphasize the importance of backbone-mediated interactions as drivers of weakened pairwise interactions, decreased long-range ordering that enables fluidization, and percolation within dense phases105. These results highlight the need for using coarse-grained models with explicit representations of polypeptide backbones as recently introduced by ref. 106. This method adapted previous approaches for coarse-graining that preserve the backbone geometry and interactions107,108. Alternatively, one can use all-atom descriptions if computational resources are available32. However, as a versatile, computationally tractable, and robust method, the approach of ref. 106 holds considerable promise.

We used a polarizable forcefield, AMOEBA. This is justified based on the accuracy of AMOEBA, and the desire to capture at least first-order induced dipole contributions. We asked if a non-polarizable forcefield would yield equivalent results. For this, we calculated PMFs for amino acids in the dilute phase using CHARMM36m protein forcefields109. The PMFs obtained from CHARMM36m (Supplementary Data 1 and Fig. S14) exhibit similar patterns to those from AMOEBA. These include the locations of the minima and the appearance of secondary minima around 8.5 Å. The excluded volumes calculated from the two forcefields show a positive correlation, with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.82. The CHARMM36m results confirmed several key observations: (1) Tyr is a stronger sticker than Phe; (2) Arg forms stronger cation–π interactions with Tyr and Phe when compared to Lys; (3) And Tyr–Tyr interactions are stronger than Arg–Tyr interactions. Note that CHARMM36m predicted relatively weaker Phe–Phe interactions when compared to Arg–Tyr. However, the overall results remain consistent with those obtained using the AMOEBA forcefield. In the dense phase mimics modeled using capped amino acids and the CHARMM36m forcefield, multivalent interactions between amino acids, including sidechain–sidechain, backbone–backbone, and sidechain–backbone interactions, drive the formation of the system-spanning network and weaken the pairwise interactions between sidechains. Overall, our findings suggest that the choice of forcefields do not alter the major conclusions that emerge from our work. This suggests that the generic nature of semidilute solutions renders the networking behavior to be relatively insensitive to the details of forcefield parameterization. The similarities of results we observe between a polarizable and non-polarizable forcefields explain why coarse-grained models, including ultra coarse-grained descriptions97, robustly capture conformational changes across phase boundary with an apparent weakening of pairwise interactions, as evidenced by chain expansion within dense phases9,10,33,37,101.

Conclusion

We leveraged the fact that dense phases are semidilute solutions and used dense phases of peptides to understand the nature of interactions within condensates. In the blob picture, chain connectivity primarily imposes topological constraints on amino acids, and the dense phase can be approximated as concentrated solutions of peptide-sized motifs. Therefore, our results represent a first step toward uncovering differences in pairwise interactions, at atomic resolution, between dilute and dense phases. The weakening of pairwise associations with increased concentration suggests the possibility that backbone-mediated interactions impose an upper bound on protein concentrations within dense phases. These interactions also fluidize dense phases, driving the formation of percolated networks within dense phases. The effects we report are likely to be amplified when considering a semidilute solution of full-length chains.

Methods

Setup of molecular dynamics simulations using AMOEBA polarizable forcefield

All the simulations were performed using TINKER 9 package110 employing the AMOEBA polarizable forcefield54. The size of the central simulation cell, which was cubic, was ~5 × 5 × 5 nm3 for both the dilute and dense phase simulations. The forcefield parameters for model compounds mimicking sidechains of Arg, Lys, Tyr, and Phe were taken from our previous work111. The forcefield parameters amoebabio18.prm in the TINKER package were used for capped amino acids. The isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble was used. The temperature and pressure were maintained at 298 K and 1 bar, respectively. Other setup details about MD simulations were identical to our previous work111. The model compounds or peptides were solvated in a cubic water box with periodic boundary conditions. Following energy minimization, molecular dynamics simulations were performed using the reversible reference system propagator algorithm integrator112 with an inner time step of 0.25 ps and an outer time step of 2.0 fs in an isothermal-isobaric ensemble (NPT) ensemble controlled using a stochastic velocity rescaling thermostat113 and a Monte Carlo constant pressure algorithm114, respectively. The particle mesh Ewald (PME) method115 with PME-GRID being 36 grid units, an order 8 B-spline interpolation116, with a real space cutoff of 7 Å was used to compute long-range corrections to electrostatic interactions. The cutoff for van der Waals interactions was set at 12 Å. This combination of a shorter cutoff for PME real space and a longer cutoff for Buffered-14-7 potential has been verified117 for AMOEBA free energy simulations118. Snapshots were saved once every ten ps.

Calculation of PMFs in the dilute phase using umbrella sampling

For the dilute phase simulations, a pair of model compounds or capped amino acids was placed in the simulation box. Umbrella sampling119 was used to calculate the PMFs of interest. For the dense phase simulations, multiple pairs of model compounds or capped amino acids were placed in the simulation box. The number of pairs were estimated based on the volume fractions of dense phases gleaned from measured binodals of A1-LCD and designed variants thereof25. Five independent simulations with different starting structures were performed for simulations that mimic dense phases. Each independent simulation was 100 ns long.

The interactions between pairs of model compounds or capped amino acids in the dilute phase were calculated using umbrella sampling. A harmonic potential with kcal/mol- Å2 was applied to restrain the distance between pairs of model compounds or capped amino acids. The geometric center of the key functional group in the model compound or the sidechain of the capped amino acids was used to calculate distances along the reaction coordinates. For Arg and Lys, the key functional groups are the guanidinium and ammonium groups, respectively. For Tyr and Phe, the aromatic ring is the key functional group.

The centers of the windows for each umbrella were between 3 Å, and 4 Å to 20 Å with an interval of 2 Å. In each window, multiple independent simulation trajectories with different starting structures are performed. The total simulation length for each window ranges from 240 to 260 ns. The weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM)120–122 was used to obtain PMFs from umbrella sampling simulations. For the dense phase simulations, the distributions of pairwise distances, P(r) were first extracted from the simulations. These were then used to compute the PMFs of interest using: . Here, kB is the Boltzmann constant, and T = 298 K is the simulation temperature.

Estimations of error bars

For the error estimation of excluded volume in the dilute phase, we used bootstrapping with replacement. First, 160 ns of simulation data in each umbrella sampling window was chosen randomly to calculate the PMF for a specific pair of model compounds or capped amino acids. The PMF was further used to calculate the excluded volume. Next, the above process was repeated ten times, resulting in ten estimates of the excluded volume. The standard deviation of these ten estimates were the statistical uncertainties for the excluded volume.

For the error estimation of excluded volume in the dense phase, five values of the excluded volume can be calculated using each of the five independent simulation trajectories. Then, the standard deviation of these five estimated values was used to represent the error bars for excluded volume.

Evaluations of convergence

To assess convergence, we performed a percolation analysis using one-fifth of the total simulation data. The results, as shown in Supplementary Data 1 and Fig. S15, match those obtained using the complete dataset in Fig. 10, indicating that structural reorganization has reached convergence. Additionally, we plotted the average degree of connectivity and the largest cluster size as a function of time. Both the average degree of connectivity and the largest cluster size increase during the first 10 ns and then fluctuate around their equilibrium values. These results demonstrate that amino acids continuously associate and dissociate, and the system achieves equilibrium after 10 ns.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the US Air Force Office of Scientific Research grant (FA9550-20-1-0241 to R.V.P.), the St. Jude Research Collaborative on the Biology and Biophysics of RNP Granules (to R.V.P.), and the US National Science Foundation (MCB-2227268 to R.V.P.).

Author contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, analysis, writing and editing, and project administration: X.Z. and R.V.P.; Funding acquisition and Supervision: RVP.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks Jose Villegas, Arumay Pal, and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Data availability

The entirety of the simulation results constitutes more than 10 TB of data. Access to the entirety of this corpus of data is available upon request. The request should be made to Xiangze Zeng or Rohit Pappu. The simulations were performed using the TINKER package, which is available via https://github.com/TinkerTools/tinker. The specialized code used, along with README files, are available as a zip archive in Supplemental Data 2. This includes details of the key files that were used to set up the TINKER simulations.

Competing interests

R.V.P. is a member of the scientific advisory board and shareholder of Dewpoint Therapeutics Inc. X.Z. does not have any financial interests to declare. Neither X.Z. nor R.V.P. have non-financial interests to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xiangze Zeng, Email: xiangzezeng@hkbu.edu.hk.

Rohit V. Pappu, Email: pappu@wustl.edu

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42004-025-01502-5.

References

- 1.Banani, S. F., Lee, H. O., Hyman, A. A. & Rosen, M. K. Biomolecular condensates: organizers of cellular biochemistry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.18, 285–298 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pappu, R. V., Cohen, S. R., Dar, F., Farag, M. & Kar, M. Phase transitions of associative biomacromolecules. Chem. Rev.123, 8945–8987 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruff, K. M. et al. Sequence grammar underlying the unfolding and phase separation of globular proteins. Mol. Cell82, 3193–3208.e3198 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang, J. et al. A molecular grammar governing the driving forces for phase separation of prion-like RNA binding proteins. Cell174, 688–699.e616 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Protter, D. S. W. & Parker, R. Principles and properties of stress granules. Trends Cell Biol.26, 668–679 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Currie, S. L. et al. Quantitative reconstitution of yeast RNA processing bodies. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA120, e2214064120 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Youn, J.-Y. et al. Properties of stress granule and P-body proteomes. Mol. Cell76, 286–294 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin, E. W. et al. Valence and patterning of aromatic residues determine the phase behavior of prion-like domains. Science367, 694–699 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farag, M., Borcherds, W. M., Bremer, A., Mittag, T. & Pappu, R. V. Phase separation of protein mixtures is driven by the interplay of homotypic and heterotypic interactions. Nat. Commun.14, 5527 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farag, M. et al. Condensates formed by prion-like low-complexity domains have small-world network structures and interfaces defined by expanded conformations. Nat. Commun.13, 7722 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin, E. W. & Mittag, T. Relationship of sequence and phase separation in protein low-complexity regions. Biochemistry57, 2478–2487 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Posey, A. E. et al. Biomolecular condensates are characterized by interphase electric potentials. J. Am. Chem. Soc.146, 28268–28281 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeng, X., Holehouse, A. S., Chilkoti, A., Mittag, T. & Pappu, R. V. Connecting coil-to-globule transitions to full phase diagrams for intrinsically disordered proteins. Biophys. J.119, 402–418 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molliex, A. et al. Phase separation by low complexity domains promotes stress granule assembly and drives pathological fibrillization. Cell163, 123–133 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kar, M. et al. Phase-separating RNA-binding proteins form heterogeneous distributions of clusters in subsaturated solutions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA119, e2202222119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kar, M., Posey, A. E., Dar, F., Hyman, A. A. & Pappu, R. V. Glycine-rich peptides from FUS have an intrinsic ability to self-assemble into fibers and networked fibrils. Biochemistry60, 3213–3222 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kar, M. et al. Solutes unmask differences in clustering versus phase separation of FET proteins. Nat. Commun.15, 4408 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krainer, G. et al. Reentrant liquid condensate phase of proteins is stabilized by hydrophobic and non-ionic interactions. Nat. Commun.12, 1085 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen, Y. et al. The liquid-to-solid transition of FUS is promoted by the condensate surface. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA120, e2301366120 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen, Y. et al. Biomolecular condensates undergo a generic shear-mediated liquid-to-solid transition. Nat. Nanotechnol.15, 841–847 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linsenmeier, M. et al. The interface of condensates of the hnRNPA1 low complexity domain promotes formation of amyloid fibrils. Nat. Chem.15, 1340–1349 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holehouse, A. S., Ginell, G. M., Griffith, D. & Böke, E. Clustering of aromatic residues in prion-like domains can tune the formation, state, and organization of biomolecular condensates. Biochemistry60, 3566–3581 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boke, E. et al. Amyloid-like self-assembly of a cellular compartment. Cell166, 637–650 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bauer, D. J., Stelzl, L. S. & Nikoubashman, A. Single-chain and condensed-state behavior of hnRNPA1 from molecular simulations. J. Chem. Phys.157, 154903 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Bremer, A. et al. Deciphering how naturally occurring sequence features impact the phase behaviours of disordered prion-like domains. Nat. Chem.14, 196–207 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohan, M. C., Shinn, M. K., Lalmansingh, J. M. & Pappu, R. V. Uncovering non-random binary patterns within sequences of intrinsically disordered proteins. J. Mol. Biol.434, 167373 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alshareedah, I. et al. Sequence-specific interactions determine viscoelasticity and aging dynamics of protein condensates. Nat. Phys.20, 1482–1491 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen, S. R., Banerjee, P. R. & Pappu, R. V. Direct computations of viscoelastic moduli of biomolecular condensates. J. Chem. Phys.161, 095103 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wei, M. T. et al. Phase behaviour of disordered proteins underlying low density and high permeability of liquid organelles. Nat. Chem.9, 1118–1125 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shillcock, J. C., Lagisquet, C., Alexandre, J., Vuillon, L. & Ipsen, J. H. Model biomolecular condensates have heterogeneous structure quantitatively dependent on the interaction profile of their constituent macromolecules. Soft Matter18, 6674–6693 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hazra, M. K. & Levy, Y. Biophysics of phase separation of disordered proteins is governed by balance between short- and long-range interactions. J. Phys. Chem. B125, 2202–2211 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galvanetto, N. et al. Extreme dynamics in a biomolecular condensate. Nature619, 876–883 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang, J., Devarajan, D. S., Nikoubashman, A. & Mittal, J. Conformational properties of polymers at droplet interfaces as model systems for disordered proteins. ACS Macro Lett.12, 1472–1478 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Welles, R. M. et al. Determinants that enable disordered protein assembly into discrete condensed phases. Nat. Chem. 16, 1062–1072 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Joshi, A. et al. Single-molecule FRET unmasks structural subpopulations and crucial molecular events during FUS low-complexity domain phase separation. Nat. Commun.14, 7331 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitrea, D. M. et al. Nucleophosmin integrates within the nucleolus via multi-modal interactions with proteins displaying R-rich linear motifs and rRNA. eLife5, e13571 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joseph, J. A. et al. Physics-driven coarse-grained model for biomolecular phase separation with near-quantitative accuracy. Nat. Comput. Sci.1, 732–743 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holland, J., Nott, T. J. & Aarts, D. G. A. L. Intrinsic hydrophobicity of IDP-based biomolecular condensates drives their partial drying on membrane surfaces. J. Chem. Phys.162, 115101 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Grosberg, A. Y. & Khokhlov, A. R. Statistical Physics of Macromolecules (AIP Press, 1994).

- 40.de Gennes, P. G. Scaling Concepts in Polymer Physics (Cornell University Press, 1979).

- 41.Dondos, A. Relation between the quality of the solvent and the number of statistical segments of a polymer at the onset of excluded-volume and complete excluded-volume behaviour. Polymer33, 4375–4378 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choi, J.-M., Hyman, A. A. & Pappu, R. V. Generalized models for bond percolation transitions of associative polymers. Phys. Rev. E102, 042403 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brady, J. P. et al. Structural and hydrodynamic properties of an intrinsically disordered region of a germ cell-specific protein on phase separation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA114, E8194–E8203 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nott, TimothyJ. et al. Phase transition of a disordered nuage protein generates environmentally responsive membraneless organelles. Mol. Cell57, 936–947 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rubinstein, M. & Colby, R. H. Polymer Physics (Oxford Univ. Press, 2003).

- 46.Shi, Y. et al. Polarizable atomic multipole-based AMOEBA force field for proteins. J. Chem. Theory Comput.9, 4046–4063 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu, J. C., Chattree, G. & Ren, P. Automation of AMOEBA polarizable force field parameterization for small molecules. Theor. Chem. Acc.131, 1138 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang, C. et al. AMOEBA polarizable atomic multipole force field for nucleic acids. J. Chem. Theory Comput.14, 2084–2108 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grossfield, A., Ren, P. & Ponder, J. W. Ion solvation thermodynamics from simulation with a polarizable force field. J. Am. Chem. Soc.125, 15671–15682 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Laury, M. L., Wang, L.-P., Pande, V. S., Head-Gordon, T. & Ponder, J. W. Revised parameters for the AMOEBA polarizable atomic multipole water model. J. Phys. Chem. B119, 9423–9437 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ren, P. & Ponder, J. W. Polarizable atomic multipole water model for molecular mechanics simulation.J. Phys. Chem. B107, 5933–5947 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shi, Y., Wu, C., Ponder, J. W. & Ren, P. Multipole electrostatics in hydration free energy calculations. J. Comput. Chem.32, 967–977 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harger, M. et al. Tinker-OpenMM: absolute and relative alchemical free energies using AMOEBA on GPUs. J. Comput. Chem.38, 2047–2055 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ponder, J. W. et al. Current status of the AMOEBA polarizable force field.J. Phys. Chem. B114, 2549–2564 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang, X., Liu, C. & Ren, P. Exploring biomolecular conformational dynamics with polarizable force field AMOEBA and enhanced sampling method milestoning. J. Chem. Theory Comput.20, 4065–4075 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.El Khoury, L. et al. Reconciling NMR structures of the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein NCp7 using extensive polarizable force field free-energy simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput.16, 2013–2020 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jing, Z., Qi, R., Thibonnier, M. & Ren, P. Molecular dynamics study of the hybridization between RNA and modified oligonucleotides. J. Chem. Theory Comput.15, 6422–6432 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Qi, R. et al. Elucidating the phosphate binding mode of phosphate-binding protein: the critical effect of buffer solution. J. Phys. Chem. B122, 6371–6376 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kilgour, M., Liu, T., Walker, B. D., Ren, P. & Simine, L. E2EDNA: simulation protocol for DNA aptamers with ligands. J. Chem. Inf. Model.61, 4139–4144 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu, T. et al. Single fluorogen imaging reveals distinct environmental and structural features of biomolecular condensates. Nat. Phys.10.1038/s41567-025-02827-7 (2025).

- 61.Pezzotti, S., König, B., Ramos, S., Schwaab, G. & Havenith, M. Liquid–liquid phase separation? Ask the water! J. Phys. Chem. Lett.14, 1556–1563 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bergeron-Sandoval, L. P. et al. Endocytic proteins with prion-like domains form viscoelastic condensates that enable membrane remodeling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA118, e2113789118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alshareedah, I., Moosa, M. M., Pham, M., Potoyan, D. A. & Banerjee, P. R. Programmable viscoelasticity in protein-RNA condensates with disordered sticker-spacer polypeptides. Nat. Commun.12, 6621 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alshareedah, I. et al. Determinants of viscoelasticity and flow activation energy in biomolecular condensates. Sci. Adv.10, eadi6539 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Law, J. O. et al. A bending rigidity parameter for stress granule condensates. Sci. Adv.9, eadg0432 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang, Y. & Yu, T. Graph theory of viscoelasticities for polymers with starshaped, multiple-ring and cyclic multiple-ring molecules. Die Makromol. Chem.186, 609–631 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Feric, M. et al. Mesoscale structure–function relationships in mitochondrial transcriptional condensates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA119, e2207303119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Feric, M. et al. Coexisting liquid phases underlie nucleolar subcompartments. Cell165, 1686–1697 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mukherjee, S. et al. Entropy tug-of-war determines solvent effects in the liquid–liquid phase separation of a globular protein. J. Phys. Chem. Lett.15, 4047–4055 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sinnokrot, M. O. & Sherrill, C. D. High-accuracy quantum mechanical studies of π−π interactions in benzene dimers. J. Phys. Chem. A110, 10656–10668 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vernon, R. M. et al. Pi-Pi contacts are an overlooked protein feature relevant to phase separation. elife7, e31486 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Harmon, T. S., Holehouse, A. S., Rosen, M. K. & Pappu, R. V. Intrinsically disordered linkers determine the interplay between phase separation and gelation in multivalent proteins. eLife6, 30294 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schuster, B. S. et al. Identifying sequence perturbations to an intrinsically disordered protein that determine its phase-separation behavior. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA117, 11421–11431 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Grimme, S. Do special noncovalent π–π stacking interactions really exist? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.47, 3430–3434 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Martinez, C. R. & Iverson, B. L. Rethinking the term “pi-stacking”. Chem. Sci.3, 2191–2201 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Huggins, M. L. Solutions of long chain compounds. J. Chem. Phys.9, 440–440 (1941). [Google Scholar]

- 77.Flory, P. J. Thermodynamics of high polymer solutions. J. Chem. Phys.10, 51–61 (1942). [Google Scholar]

- 78.Muthukumar, M. Thermodynamics of polymer solutions. J. Chem. Phys.85, 4722–4728 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 79.Farag, M., Holehouse, A. S., Zeng, X. & Pappu, R. V. FIREBALL: a tool to fit protein phase diagrams based on mean-field theories for polymer solutions. Biophys. J.122, 2396–2403 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Luo, C., Qiang, Y. & Zwicker, D. Beyond pairwise: higher-order physical interactions affect phase separation in multicomponent liquids. Phys. Rev. Res.6, 033002 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 81.Choi, J.-M., Dar, F. & Pappu, R. V. LASSI: a lattice model for simulating phase transitions of multivalent proteins. PLoS Comput. Biol.15, e1007028 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dar, F. et al. Biomolecular condensates form spatially inhomogeneous network fluids. Nat. Commun.15, 3413 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Choi, J.-M., Holehouse, A. S. & Pappu, R. V. Physical principles underlying the complex biology of intracellular phase transitions. Annu. Rev. Biophys.49, 107–133 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.McColl, W. F. & Noshita, K. On the number of edges in the transitive closure of a graph. Discret. Appl. Math.15, 67–73 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 85.Newman, M. E. J. Networks: An Introduction (Oxford Univ. Press, 2010).

- 86.Stauffer, D. & Aharony, A. Introduction To Percolation Theory (Taylor & Francis, 1992).

- 87.Cho, S. S., Levy, Y. & Wolynes, P. G. P versus Q: structural reaction coordinates capture protein folding on smooth landscapes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA103, 586–591 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Snow, C. D., Rhee, Y. M. & Pande, V. S. Kinetic definition of protein folding transition state ensembles and reaction coordinates. Biophys. J.91, 14–24 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Du, R., Pande, V. S., Grosberg, A. Y., Tanaka, T. & Shakhnovich, E. S. On the transition coordinate for protein folding. J. Chem. Phys.108, 334–350 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 90.De Gennes, P. G., Pincus, P., Velasco, R. M. & Brochard, F. Remarks on polyelectrolyte conformation. J. Phys. Fr.37, 1461–1473 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pincus, P. Excluded volume effects and stretched polymer chains. Macromolecules9, 386–388 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- 92.Carter-Fenk, K. et al. The energetic origins of Pi–Pi contacts in proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc.145, 24836–24851 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tanaka, F. in Molecular Gels: Materials with Self-assembled Fibrillar Networks (Terech, P. & Weiss, R. G.) Ch. 1 (Springer, 2006).

- 94.Semenov, A. N. & Rubinstein, M. Thermoreversible gelation in solutions of associative polymers. 1. Statics. Macromolecules31, 1373–1385 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rubinstein, M. & Dobrynin, A. V. Solutions of associative polymers. Trends Polym. Sci.5, 181–186 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 96.Czub, M. P. et al. Phase separation of a microtubule plus-end tracking protein into a fluid fractal network. Nat. Commun. 16, 1165 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]