Abstract

Antibiotic resistance in bacteria is a major global health concern. The wide spread of carbapenemases, bacterial enzymes that degrade the last-resort carbapenem antibiotics, is responsible for multidrug resistance in bacterial pathogens and has further significantly exacerbated this problem. Acinetobacter baumannii is one of the leading nosocomial pathogens due to the acquisition and wide dissemination of carbapenem-hydrolyzing class D β-lactamases, which have dramatically diminished available therapeutic options. Thus, new antibiotics that are active against multidrug-resistantA. baumannii and carbapenemase inhibitors are urgently needed. Here we report characterization of the interaction of the C5α-methyl-substituted carbapenem NA-1–157 with one of the clinically important class D carbapenemases, OXA-58. Antibiotic susceptibility testing shows that the compound is more potent than commercial carbapenems against OXA-58-producingA. baumannii, with a clinically sensitive MIC value of 1 μg/mL. Kinetic studies demonstrate that NA-1–157 is a very poor substrate of the enzyme due mainly to a significantly reduced deacylation rate. Mass spectrometry analysis shows that inhibition of OXA-58 by NA-1–157 proceeds through both the classical acyl-enzyme intermediate and a reversible covalent species. Time-resolved X-ray crystallographic studies reveal that upon acylation of the enzyme, the compound causes progressive decarboxylation of the catalytic lysine residue, thus severely impairing deacylation. Overall, this study demonstrates that the carbapenem NA-1–157 is highly resistant to degradation by the OXA-58 carbapenemase.

Keywords: Acinetobacter, antibiotic resistance, OXA-58 carbapenemase, inhibitor, X-ray structure

Graphical Abstract:

Antibiotic resistance is a top public health threats and leading cause of death globally.1 It is projected that without intervention, by 2050 this threat may result in more than 300 million deaths, with up to $100 trillion in associated costs.2,3Apart from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the ESKAPE pathogens, including multidrug-resistant (MDR) Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacter species, constitute the leading cause of bacterial infections worldwide and are of particular concern due to limited therapeutic options available for treatment.4 Of these, A. baumannii is an opportunistic pathogen that frequently causes ventilator-associated pneumonia, bacteremia, endocarditis and urinary tract, wound and skin infections5. The pathogen’s ability to survive in extreme environmental conditions, coupled with its propensity to accumulate various resistance determinants, makes it a common cause of nosocomial infections. Infections caused by MDR A. baumannii result in lengthy hospital stays, increased healthcare costs and very high mortality rates.6,7 Consequently, this bacterium is placed at the top of the priority lists by both the CDC and WHO, for which effective treatments are urgently needed.8,9

The predominant mechanism of resistance to antimicrobial agents in A. baumannii is production of β-lactamases, enzymes that inactivate the most widely used class of antibiotics, the β-lactams.10 β-lactamases are categorized into four molecular classes; those of classes A, C and D utilize an active site serine for catalysis, while those of class B are zinc-dependent metallo enzymes.11,12 While enzymes from all classes have been identified in A. baumannii, wide spread of carbapenem-hydrolyzing class D β-lactamases (CHDLs) is of particular concern, as it has resulted in significant reduction of the efficacy of the last-resort β-lactam antibiotics, the carbapenems, against this pathogen.13,14 This problem is further exacerbated by an increase of antibiotic use in COVID-19 patients during the pandemic, which facilitated further selection and spread of hospital-acquired carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii isolates.15 In A. baumannii, CHDLs are represented by six main groups based on sequence identity; those from the OXA-23-like, OXA-24/40-like, OXA-58-like, OXA-143-like and OXA-235-like groups are acquired, while those from the OXA-51-like group are intrinsic.16,17 These enzymes inactivate carbapenems through a mechanism where the catalytic serine residue is deprotonated by the active site carboxylated lysine. This activated serine nucleophilically attacks the carbonyl carbon of the β-lactam ring, forming a short-lived tetrahedral intermediate and resulting in opening of the β-lactam ring of the antibiotic to form an acyl-enzyme complex.18,19 Subsequently, the covalent bond between the active site serine of the enzyme and the antibiotic is hydrolyzed by a water molecule that is activated by the carboxylated lysine during the deacylation step of the reaction, leading to release of the inactivated drug.

To combat β-lactamase-mediated resistance, inhibitors of these enzymes, clavulanic acid, sulbactam and tazobactam, were developed to be used in combination with β-lactams, thus preventing degradation of these drugs.20 As these earliest inhibitors were active mostly against class A β-lactamases, more recently non-β-lactam inhibitors, diazabicyclooctanes (DBOs) and boronates, were developed to fight class D-mediated resistance.21–24 Another promising approach to fight carbapenemase-mediated resistance is to develop novel carbapenem antibiotics that can be used alone or in combination with other drugs. Recently, it was demonstrated that the C5α-methyl-substituted carbapenem NA-1–157 has improved potency against Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium abscessus25 and also A. baumannii and Klebsiella spp. isolates producing the major Enterobacteriaceae CHDLs of the OXA-48-type.26 We also recently reported that NA-1–157 has excellent activity against strains of A. baumannii, K. pneumoniae and Escherichia coli producing the class A GES-5 carbapenemase.27 Our kinetic experiments showed that NA-1–157 inhibits GES-5 by blocking deacylation, in contrast to what we observed for interaction of the compound with OXA-48, where impaired acylation is entirely responsible for poor turnover of this novel antibiotic by the enzyme.

In the current study, we have expanded our research to evaluate the interaction of NA-1–157 with another major CHDL of A. baumannii, OXA-58. This compound suppresses growth of OXA-58-producing A. baumannii at clinically relevant concentrations. Kinetic studies show that NA-1–157 is very poorly turned over by OXA-58 due to diminished acylation and an even slower deacylation rate. Structural studies reveal sluggish deacylation is caused by decarboxylation of the catalytic lysine residue upon acylation of the enzyme by NA-1–157.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Minimal Inhibitory Concentrations (MICs) of NA-1–157 Against Carbapenemase-Producing A. baumannii.

To evaluate activity of NA-1–157, we determined its MICs against A. baumannii CIP 70.10 producing OXA-58 and other CHDLs. Against the strain producing OXA-58, the MIC was reduced 4- and 8-fold to the clinically sensitive level of 1 μg/mL when compared to meropenem and imipenem, respectively (Table 1). The MIC was also only 2-fold above the control strain, indicating high resistance of NA-1–157 to inactivation by this enzyme. NA-1–157 also demonstrated superior activity against the strain producing all other carbapenemases. Its MICs were in the clinically susceptible or intermediate range (0.5–4 μg/mL) in all cases, except for OXA-143-producing A. baumannii where the MIC value was 8 μg/mL. Combined, these data show that NA-1–157 is a promising new carbapenem with activity against CHDL-producing A. baumannii.

Table 1.

MICs of Selected Carbapenems Against A. baumannii CIP 70.10 Producing CHDLs

| MICs (μg/mL) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | controla | OXA-58 | OXA-23 | OXA-24/40 | OXA-48 | OXA-51 | OXA-143 |

| NA-1-157 | 0.5 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 0.5 | 2 | 8 |

| meropenem | 0.5b | 4b | 64b | 128b | 16b | 8 | 256 |

| imipenem | 0.25b | 8b | 32b | 64b | 16b | 2 | 128 |

A. baumannii CIP 70.10 harboring the pNT221 vector.

Data were previously published.47

Enzyme Kinetics.

To get insights into the mechanism of interaction of OXA-58 with NA-1–157, we monitored the reaction between them under steady-state conditions. The reaction rate progressively slowed for 3 h before reaching a steady-state phase (kcat = (8.2 ± 0.2) × 10−5 s−1; Figure 1A and Table 2), indicating that NA-1–157 is a very poor substrate of OXA-58. The total absorbance change for one turnover and the initial absorbance were on average 25% lower than the expected values, suggesting that part of the acylation reaction completed within the first 5–10 s (dead-time) required for manual mixing. This was confirmed under single turnover conditions (Figure 1B inset), where the acylation rate constant for this fast phase (k2 fast; Scheme 1) was calculated to be 1.0 ± 0.3 s−1 (Table 2). The slow phase of acylation proceeded for 60 min (Figure 1B), and k2 slow was calculated to be (8.6 ± 0.6) × 10−4 s−1 (Table 2), which is >1000-fold slower than k2 fast. In contrast, the same experiment with the substrate meropenem showed that acylation of OXA-58 was monophasic, with a k2 value of 0.015 ± 0.05 s−1, which is 67-fold slower than k2 fast and 17-fold faster than k2 slow for NA-1–157. Next, the deacylation rate constant k3 was measured by jump dilution and calculated to be (9.1 ± 0.3) × 10−5 s−1 (Table 2 and Figure 1C), which is very similar to kcat and 10-fold slower than the acylation rate constant k2 slow. Compared to meropenem, where k3 = 0.21 ± 0.01 s−1, NA-1–157 deacylates from OXA-58 >2000-fold slower. These data show that unlike for meropenem, where acylation is the rate-limiting step, deacylation is rate limiting for turnover of NA-1–157 by OXA-58. Combined, our experiments demonstrated that the reaction of OXA-58 with NA-1–157 proceeds through fast and slow acylation phases (comprising 25 and 75%, respectively) followed by much slower deacylation. As the deacylation half-life of the acyl-enzyme complex is >2 h, significantly exceeding the bacterial doubling time, for clinical purposes NA-1–157 can be considered an inhibitor of OXA-58.

Figure 1. Kinetics of the interaction of OXA-58 with NA-1–157.

(A) Representative progress curve under steady-state conditions. (B) Time course of a single turnover reaction for determination of k2. The inset shows the fast phase of the reaction. (C) Recovery of enzyme activity to determine k3. (D) Time dependent inactivation of OXA-58 in the presence of NA-1–157. € Progress curves to determine koff in the presence (light gray) and absence (black) of NA-1–157. (F) The kinter values plotted versus concentration of NA-1–157 to determine kNA-1–157 and KI. The “x” on the y-axis indicates the expected starting point of the reaction. The dashed and solid black lines show the best fit of the data.

Table 2.

Kinetic Parameters for Carbapenems with OXA-58

| parameter | NA-1–157 | MEMa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| kcat (s−1) | (8.2 ± 0.2) × 10−5 | (1.40 ± 0.04) × 10−2 | |

| k2 (s−1) |

k2 fast (s−1) k2 slow (s−1) |

1.0 ± 0.3 (8.6 ± 0.6) × 10−4 |

(1.50 ± 0.05) × 10−2b |

| k3 (s−1) | (9.1 ± 0.3) × 10−5 | 0.21 ± 0.01c | |

| koff (s−1) | (1.05 ± 0.05) × 10−2 | NAd | |

| kNA-1–157 (s−1) | 0.55 ± 0.05 | NA | |

| KI (μM) | 1.9 ± 0.3 | NA | |

| kNA-1–157/KI (M−1 s−1) | (2.9 ± 0.5) × 105 | NA |

MEM, meropenem.

Acylation of OXA-58 by meropenem was monophasic.

Value was calculated as described in the Materials and Methods.

NA, not applicable.

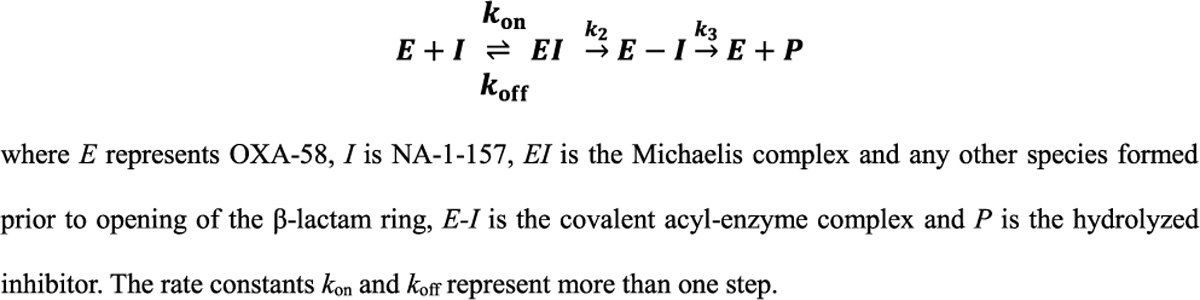

Scheme 1.

Minimal Reaction Pathway for the Interaction of OXA-58 with NA-1–157

To further understand the mechanism of interaction between OXA-58 and NA-1–157, we determined the rate of enzyme inactivation using a competition assay with nitrocefin as a reporter substrate as described earlier.27 In this experiment, nitrocefin hydrolysis is inhibited by the compound through its competition for binding to the active site of the enzyme, whether this binding is covalent or not. The progress curves showed time-dependent inhibition in the presence of NA-1–157, with the reaction reaching the steady-state velocity within only a minute or less (Figure 1D). Such fast inhibition implies involvement of the fast phase of acylation (half-life of 0.7 s) and excludes contribution of the slow phase of acylation and deacylation to this process (half-lives of 13 min and 2.1 h, respectively). However, as the fast phase of acylation constitutes only 25% of the total reaction, another factor(s) has to be involved that is responsible for inhibition of the remaining 75% of the enzyme. Recently, we demonstrated that inactivation of NA-1–157 with the class A carbapenemase GES-5 proceeds through formation of both the irreversible acyl-enzyme complex and a nonclassical reversible species.27 To investigate whether this is also the case for inactivation of OXA-58 by NA-1–157, we performed the jump dilution experiment after a 2 min preincubation of the compound with the enzyme to allow for only the fast phase of acylation to complete. Approximately 70% of enzyme activity was regained, with a reactivation rate (koff; Scheme 1) of (1.05 ± 0.05) × 10−2 s−1 (Table 2 and Figure 1E), showing that this population of OXA-58 is indeed inhibited reversibly during the 2 min time period. These data are in good agreement with the results of the single turnover experiment described above showing that over a similar time frame, only 25% of OXA-58 formed the irreversible acyl-enzyme complex (according to k2 fast). Since both reversible and irreversible inactivation are observed for the interaction between OXA-58 and NA-1–157, we evaluated the maximum rate of inactivation by determining the rate constant kNA-1–157 as described earlier.27 The observed rates (kinter values) from the progress curves obtained in the competition assay with nitrocefin (Figure 1D) were plotted as a function of the concentration of NA-1–157 (Figure 1F). The generated curve was hyperbolic, consistent with a two-step inactivation mechanism; the calculated value for kNA-1–157 was 0.55 ± 0.05 s−1 and KI, representing the apparent affinity of OXA-58 for NA-1–157, was 1.9 ± 0.3 μM (Table 2). The efficiency of inhibition (kNA-1–157/KI) was found to be (2.9 ± 0.5) × 105 M−1 s−1, showing that NA-1–157 is a potent inhibitor of OXA-58. Our kinetic experiments also showed that the initial velocity in the presence of increasing concentration of NA-1–157 did not change (Figure 1D), which supports a two-step mechanism (Scheme 1) where a high affinity inhibitory complex is reversible with a rate (koff) that is much slower (∼50-fold) than the rate of enzyme inactivation (kNA-1–157) (Table 2).28 This reversible complex involves 75% of the total enzyme, while the remaining 25% is represented by the classical irreversible acyl-enzyme intermediate.

Mass Spectrometry (MS).

To further investigate the nature of the species formed during the catalytic reaction, we utilized MS under denaturing conditions. Analysis of the mass spectrum of apo-OXA-58 showed the presence of a dominating peak with a mass of 29,364 Da, corresponding to the calculated mass of the apoenzyme (Figure S1A.1). When OXA-58 was incubated with NA-1–157 (383 Da), we observed a proportional shift of all peaks in the apoenzyme spectrum, showing that minor peaks represent modified active OXA-58. When OXA-58 was incubated with a 5-fold excess of NA-1–157 for 5 min, the peak corresponding to the apoenzyme disappeared and two new peaks with larger masses (29,747 Da and 29,703 Da) were observed (Figure S1A.1). The former represents the covalent OXA-58-NA-1–157 complex, while the latter species could result from either loss of the carboxylate or the 6α-hydroxyethyl group (6α-HE) of NA-1–157 in the complex.29,30 Even at the OXA-58:NA-1–157 ratio of 2:1, all compound was in complex with the enzyme (Figure S1B). However, our kinetic measurements showed that during this short time period (5 min) we observed a change in absorbance due to opening of the β-lactam ring, which leads to formation of the covalent acyl-enzyme intermediate, for only 25% of the enzyme. This implies that in the remaining 75% of the covalent species observed by MS, the β-lactam ring must still be intact. Earlier we obtained a similar result when evaluating the GES-5-NA-1–157 interaction, where part of the covalent species observed by MS were reversible.27 To evaluate reversibility of the covalent OXA-58-NA-1–157 species, we employed a chasing experiment using another carbapenem (PQ-1–219) with a smaller mass (Figure S1A.2). After 5 min and 1 h incubation of OXA-58 with NA-1–157, excess of the compound was removed chromatographically, and the reaction was chased by addition of PQ-1–219. After 5 min of incubation, MS analysis showed presence of 23 ± 3% of the OXA-58-NA-1–157 complex and 76 ± 3% of the OXA-58-PQ-1–219 complex (Figure S1A.2). After 1 h, the amount of the OXA-58-NA-1–157 complex increased to 63 ± 2% (Figure S1A.2), reflecting progressive formation of the irreversible acyl-enzyme species during the slow phase of acylation. Thus, unlike MS analysis of species generated after 5 min incubation which showed that 100% of OXA-58 forms a covalent complex with NA-1–157, both the spectrophotometric and chasing MS experiments demonstrated that only 25% of the species are the irreversible covalent acyl-enzyme intermediate. The remaining 75% are reversible and could be represented by a tetrahedral intermediate or any other potential covalent intermediate where the β-lactam ring is still intact.27 Existence of a reversible tetrahedral intermediate was earlier also proposed for the interaction of the L,D-transpeptidase Ldtfm with β-lactams.31

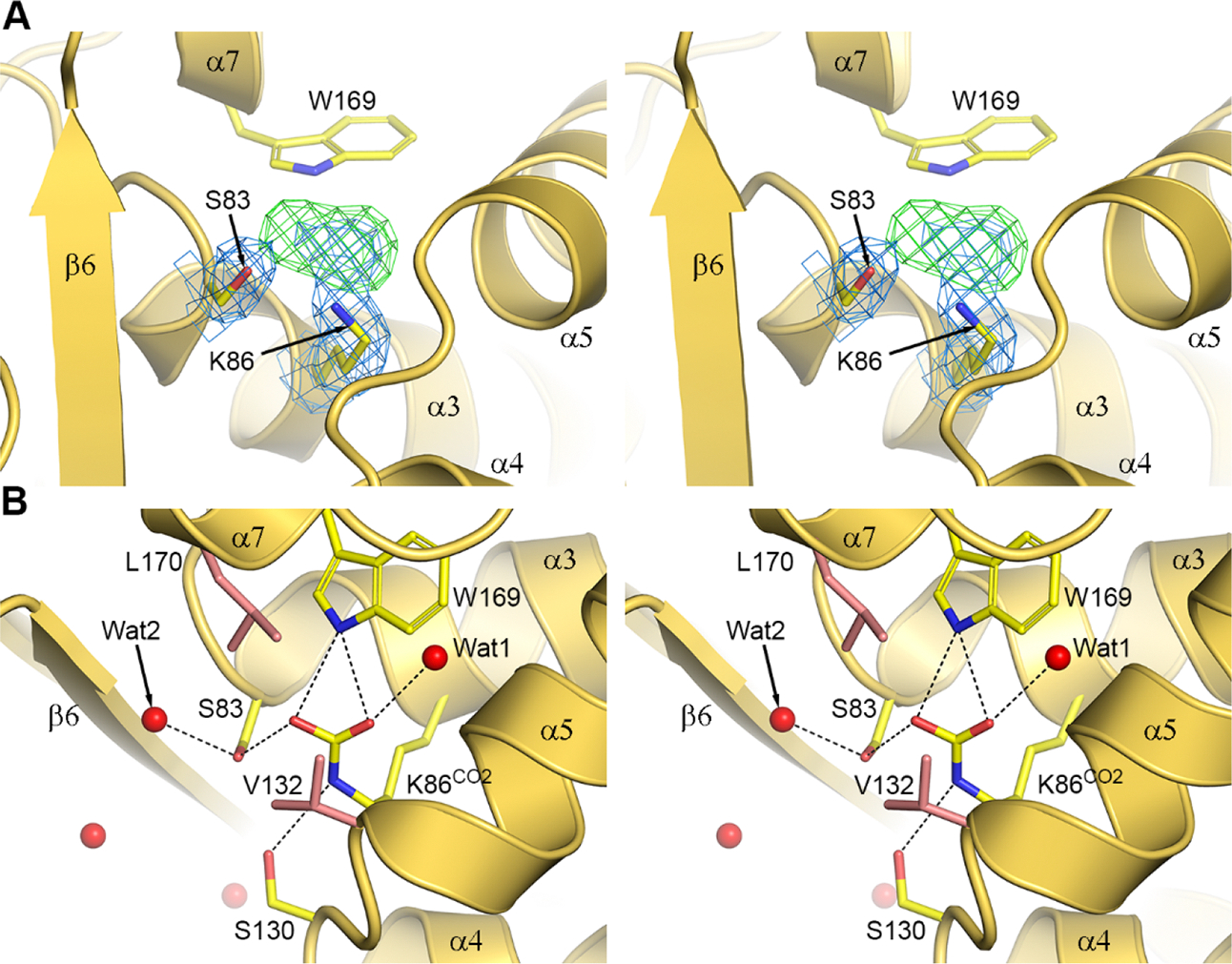

Structure of Apo-OXA-58.

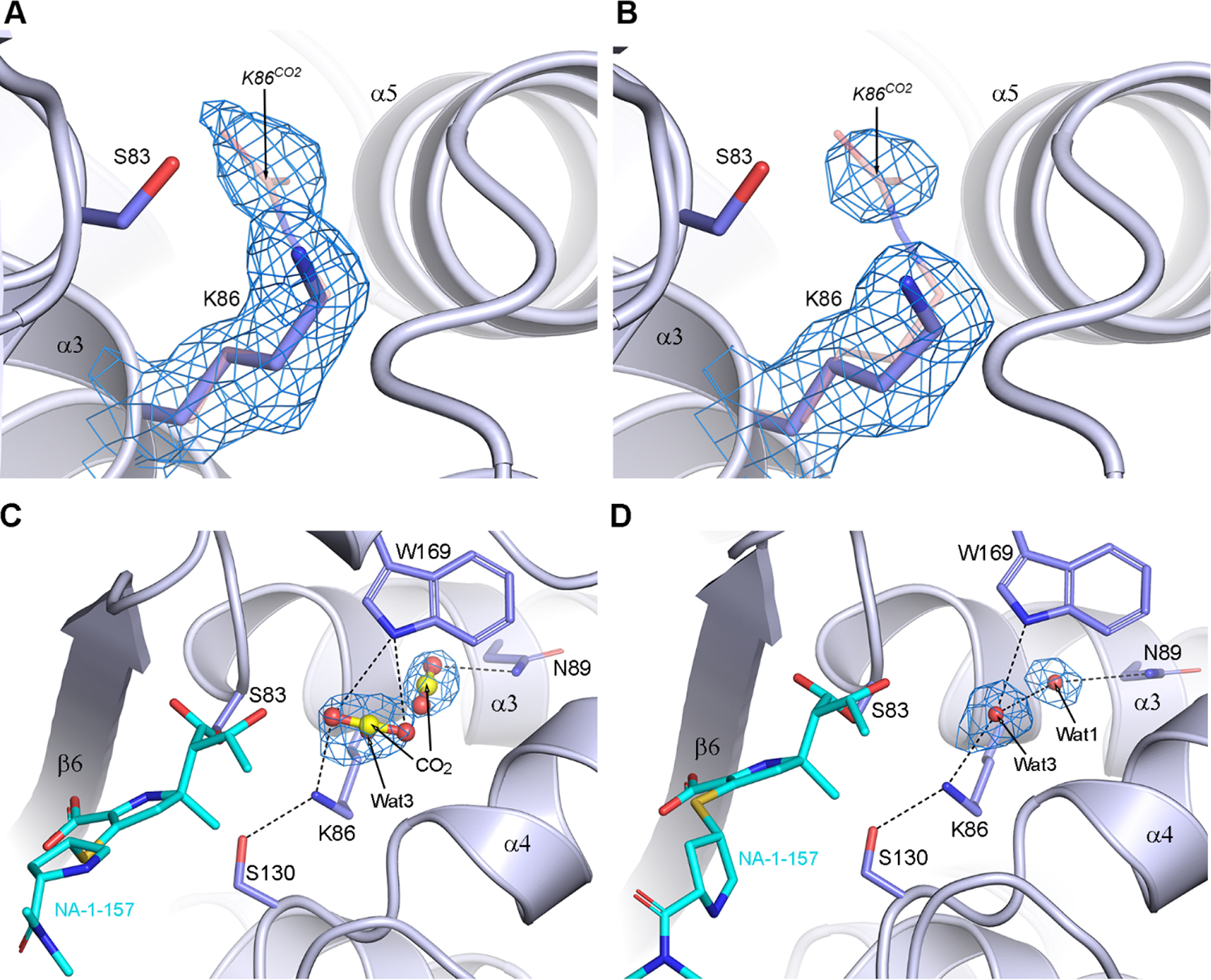

The structure of apo-OXA-58 (PDB code 9d78) was determined to serve as the zero time point for subsequent inhibitor binding studies. Superpositions of five previously deposited and reported apoenzyme structures against the current structure gave rmsds ranging from 0.27 to 0.90 Å (Table S1). There are four independent monomers in the asymmetric unit, and for clarity only one monomer is shown in the figures (Figure S2). Superposition of the four monomers against each other gave a rmsd of 0.30 Å, suggesting there are very little structural differences. In all four monomers, Lys86 was carboxylated (Figure 2A) (hereinafter designated Lys86CO2) and sequestered inside an internal pocket, sealed from the external solvent and the active site by two hydrophobic side chains (Val132 and Leu170; Figure 2B) which form a hydrophobic cap as described in other class D β-lactamases.32–35 The Lys86CO2 carboxylate group is hydrogen bonded directly to the catalytic Ser83 Oγ atom, the Nε1 atom of Trp169 and a water molecule (Wat1) deeper inside this pocket. A long (3.3–3.5 Å) hydrogen bond between the Nζ atom and the Oγ of Ser130 is also present in two of the monomers (Figure 2B). The active site is occupied by several well-ordered water molecules, including Wat2 located in the oxyanion hole formed by the main chain amide nitrogen atoms of Ser83 and Trp190.

Figure 2. Structure of apo-OXA-58.

(A) Stereoview of the active site of apo-OXA-58. The 2Fo-Fc electron density (blue mesh, 1σ) is shown for the Ser83 and Lys86 side chains. Elongated residual Fo-Fc (green mesh, 3.5σ), and 2Fo-Fc density for Lys86 indicates its carboxylation state. These maps were calculated prior to refinement. (B) Stereoview of the refined apo-OXA-58 structure showing the interactions (black lines) of Lys86CO2.

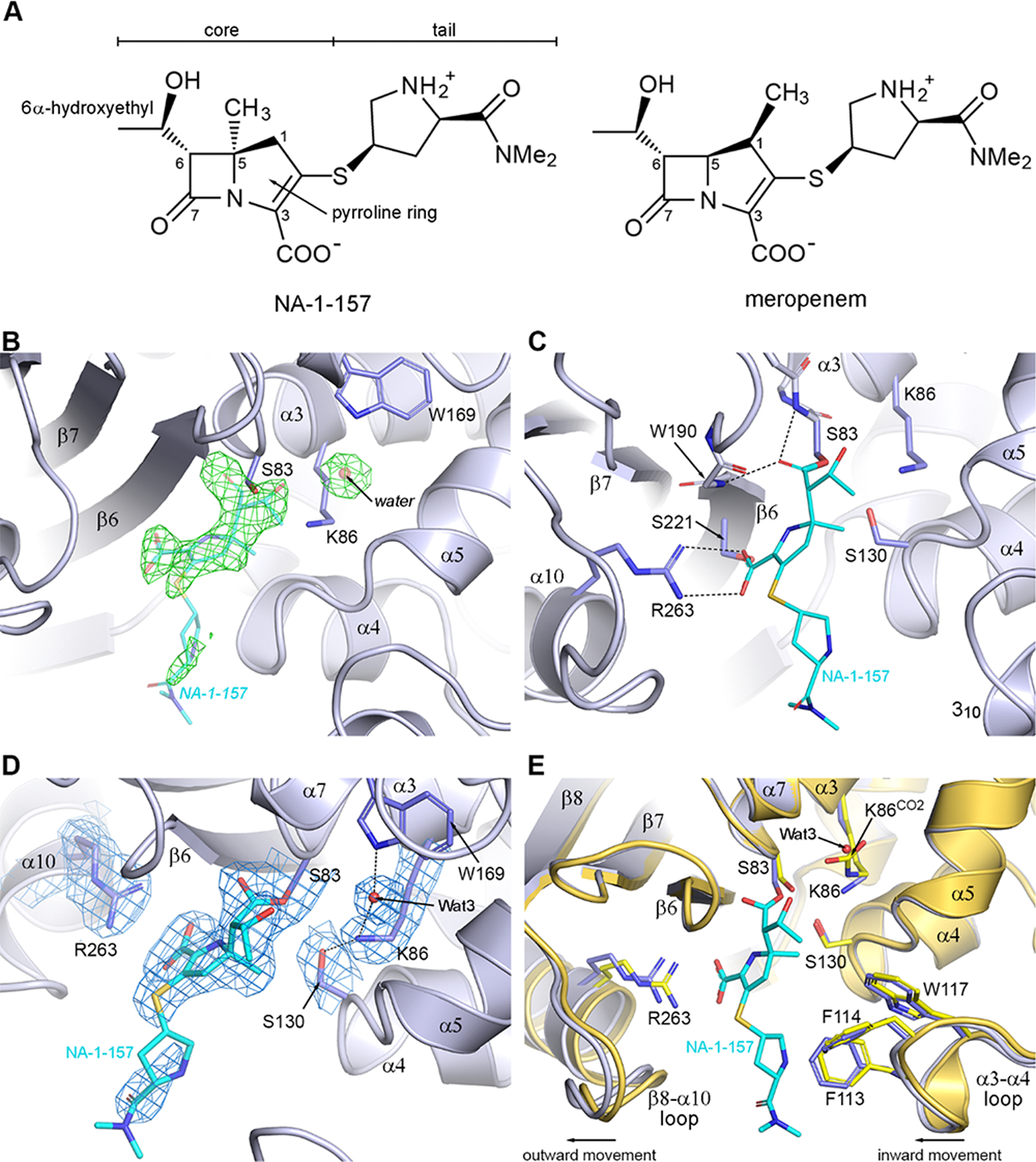

The OXA-58-NA-1–157 Complex.

To ensure formation of the acyl-enzyme complex between NA-1–157 (Figure 3A) and OXA-58, we initially soaked apo-OXA-58 crystals in a 10 mM NA-1–157 solution for 2.5 h. Strong residual density attached to the side chain of Ser83 was observed in the active site (Figure 3B), and an acylated form of NA-1–157 was refined to give a final occupancy of 85% on average. The orientation of the core of the inhibitor (Figure 3A) and the interactions with the enzyme are identical in the four monomers (Figure 3C and Figure S3). The density for the pyrrolidine tail was weak (Figure 3B), suggesting a degree of flexibility or multiple orientations. The C7 carbonyl of NA-1–157 sits in the oxyanion hole, and forms hydrogen bonds to the main chain amide nitrogen atoms of Ser83 and Trp190 (Figure 3C). The C3 carboxylate interacts with Arg263 and accepts a hydrogen bond from Ser221. The 6α-HE is in an inward-facing configuration,27 with the C62 and O62 atoms pointing toward Ser83 and Lys86 (Figure 3C). The pyrroline ring and the exocyclic sulfur atom are coplanar, consistent with a Δ2 tautomeric configuration of the ring (Figure 3D). This tautomeric configuration has been associated with more efficient deacylation of carbapenems by class A and D β-lactamases.36−38 However, our kinetic data show that NA-1–157, an atypical carbapenem, acts as an inhibitor of OXA-58 and deacylates very inefficiently, indicating that some other factors must supersede the role played by the tautomerization state. Relative to apo-OXA-58, Lys86 is decarboxylated, and a water molecule (Wat3) is present between Lys86 and Trp169 (Figure 3D). The Cε-Nζ bond of the decarboxylated lysine has rotated by 45° such that the Nζ atom points toward the α4-α5 loop and retains the hydrogen bond with Ser130 (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. The 2.5 h OXA-58-NA-1–157 complex.

(A) Structures of NA-1–157 and meropenem. (B) Residual Fo-Fc electron density (green mesh, 3.5σ) in the OXA-58 active site. (C) The refined OXA-58-NA-1–157 2.5 h complex. The hydrogen bonding interactions are shown. (D) Active site of the OXA-58-NA-1–157 complex showing the final 2Fo-Fc density (blue mesh, 1σ). (E) Superposition of the OXA-58-NA-1–157 complex (blue) onto the apo-OXA-58 structure (yellow).

Superposition of the 2.5 h complex onto the apo-OXA-58 structure gave a rmsd of 0.3 Å for all monomer combinations, and presence of NA-1–157 induces noticeable positional differences of some residues lining the active site cleft (Figure 3E). The α3-α4 loop containing the aromatic residues Phe113, Phe114 and Trp117, and the β8-α10 loop containing Arg263 are both shifted laterally (0.6 and 0.8 Å, respectively) relative to their position in the apoenzyme. In addition, the α4-α5 loop and Ser130 move outward by ∼0.5 Å. These loop movements do not change the size of the active site cleft.

Comparison with the OXA-58-Meropenem Complex.

Superposition of the OXA-58-meropenem complex (PDB code 7vvi) onto the 2.5 h OXA-58-NA-1–157 structure (Figure 4A) reveals three major differences. First, while Lys86 in the OXA-58-NA-1–157 complex is decarboxylated, it is fully carboxylated in the OXA-58-meropenem complex. Second, unlike in NA-1–157 where the 6α-HE is inward-facing, the meropenem 6α-HE is outward-facing (Figure 4B). Lastly, the core of NA-1–157 (Figure 3A) is translated approximately 0.9 Å away from the α4-α5 loop and Ser130 relative to meropenem and rotated ∼15–20°, positioning the exocyclic sulfurs ∼2 Å apart (Figure 4). Since the only difference between the two carbapenems is in the position of the methyl group on the pyrroline ring (Figure 3A), potential steric clashes due to the presence of the C5α-methyl group in NA-1–157 were evaluated. A model was constructed by moving NA-1–157 to a position comparable to meropenem such that the C5 atoms coincide and the C7 carbonyl remains in the same place (Figure 4B). This places the C5-methyl atom (C51) 0.8 Å closer to the α4-α5 loop, where it would severely clash with the carbonyl oxygen, Oγ and Cβ atoms of Ser130. In the structure of the OXA-58-NA-1–157 complex, this steric strain is alleviated by the concerted movement of NA-1–157 and the α4-α5 loop in opposite directions. This movement creates extra space, allowing the 6α-HE of NA-1–157 to rotate to an inward-facing configuration.

Figure 4. Comparison of the NA-1–157 and meropenem complexes of OXA-58.

(A) Superposition of the OXA-58-meropenem complex (7vvi, brown) onto the 2.5 h OXA-58-NA-1–157 complex (blue). (B) Close-up view of panel (A). Close contacts are shown as red dashed lines. Magenta sticks indicate residues of the OXA-58-meropenem complex.

Time-Resolved Binding of NA-1–157.

To ascertain a clearer picture of the OXA-58-NA-1–157 interaction, additional soaking was performed for 1.5, 5, 7.5, 10 and 20 min. Representative residual electron density in the enzyme active site for the first four time points is shown in Figure S4A–D. Polder electron density maps at 1.5 and 5 min were also calculated (Figure S4E,F). Already at the earliest time point, it is evident that a covalent bond between the Ser83 Oγ atom and the C7 of NA-1–157 is beginning to form (Figure S4A). At 5 min, electron density for the inhibitor is increased, and the location of the 6α-HE starts to become evident (Figure S4B). By 7.5 min, the Fo-Fc density for the majority of the NA-1–157 core is clearly defined (Figure S4C), and at 10 min the pyrrolidine tail starts to appear in some of the monomers (Figure S4D). The 20 min time point (not shown) is identical to the 2.5 h complex (Figure 3B). The slow buildup of the acyl-enzyme intermediate supports the kinetic and MS results, showing sluggish acylation of OXA-58 by NA-1–157.

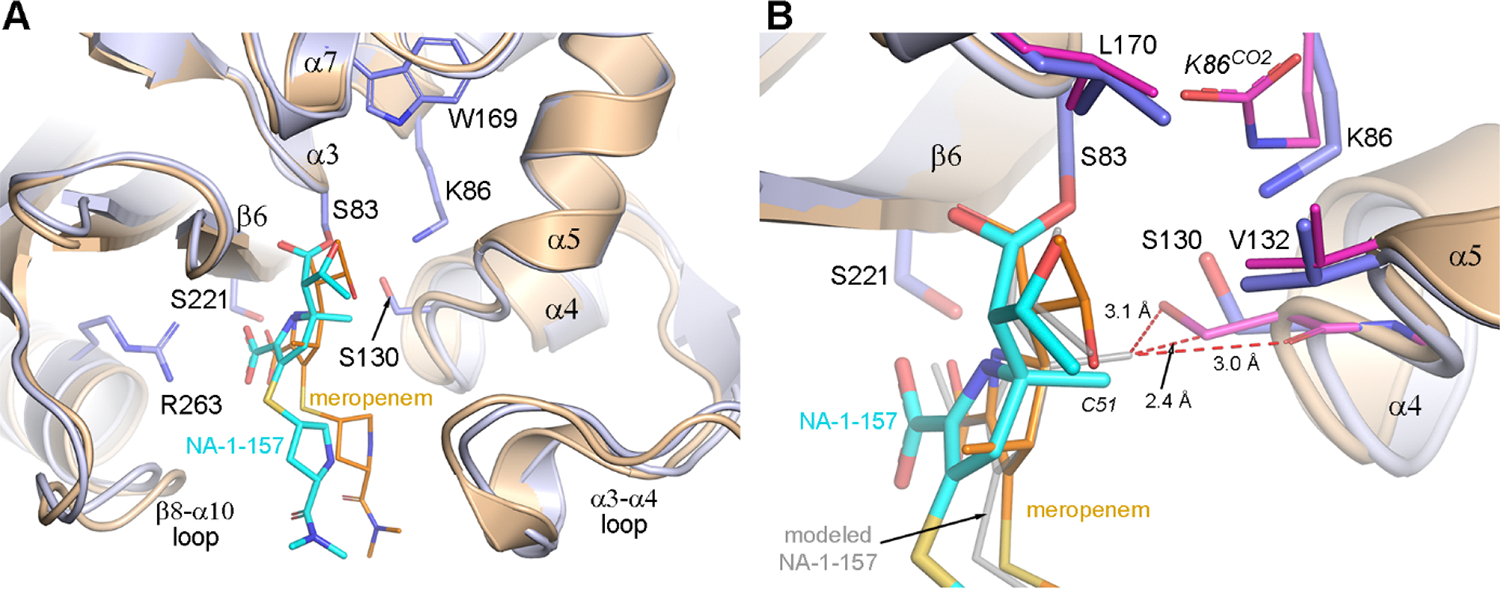

The increase in difference density for NA-1–157 is coupled with a loss of definition in the density for the carboxylate on Lys86CO2. At the shortest time points, there is connected 2Fo-Fc density between the lysine side chain and the carboxylate group (Figure 5A), but by 7.5 min we observe discontinuous density corresponding to a free Lys86 and either a water or CO2 (Figure 5B). This transition from Lys86CO2 to Lys86 is completed by 10 min, and there is a clear differentiation of two states within the crystal. In monomers A and C, there is a combination of CO2 and water at the end of the Lys86 side chain, and a putative CO2 deeper in the lysine pocket (Figure 5C). Although in both cases the densities could possibly be attributed to highly disordered water, their elongated nature is much more suggestive of partially occupied CO2. Occupancy refinement gives values for the two CO2 molecules of 30% and 37%. This could also be visualized in the initial Fo-Fc electron density maps calculated after molecular substitution (Figure S5A,C), where there is clear elongated density extending from Lys86 toward Asn89 at the rear of the lysine pocket. In monomers B and D, the initial residual Fo-Fc maps at 10 min suggested two water molecules in the lysine pocket in both monomers (Figure S5B,D), refined at 100% occupancy (Figure 5D). Decarboxylation of the catalytic lysine and presence of free CO2 in different locations in the lysine pocket have also been observed in acyl-enzyme complexes of the inhibitor avibactam with the CHDLs OXA-24 and OXA-48 (Figure S6).39 We also observed this phenomenon in the acyl-enzyme complex of the class D β-lactamase CDD-1 from Gram-positive Clostridioides difficile with avibactam.35

Figure 5. Structures of OXA-58-NA-1–157 complexes at different time points after soaking.

(A) 1.5 min and (B) 7.5 min 2Fo-Fc density for the Lys86 side chain. The K86CO2 in the apo-OXA-58 structure is shown as pink sticks. (C) Monomer C at 10 min showing two partially occupied CO2 molecules and also a partially occupied water (Wat3). (D) Monomer B at 10 min showing the presence of two fully occupied Wat1 and Wat3 molecules. Hydrogen-bonding interactions are shown as black dashed lines. In all panels, the 2Fo-Fc density is contoured at 1σ.

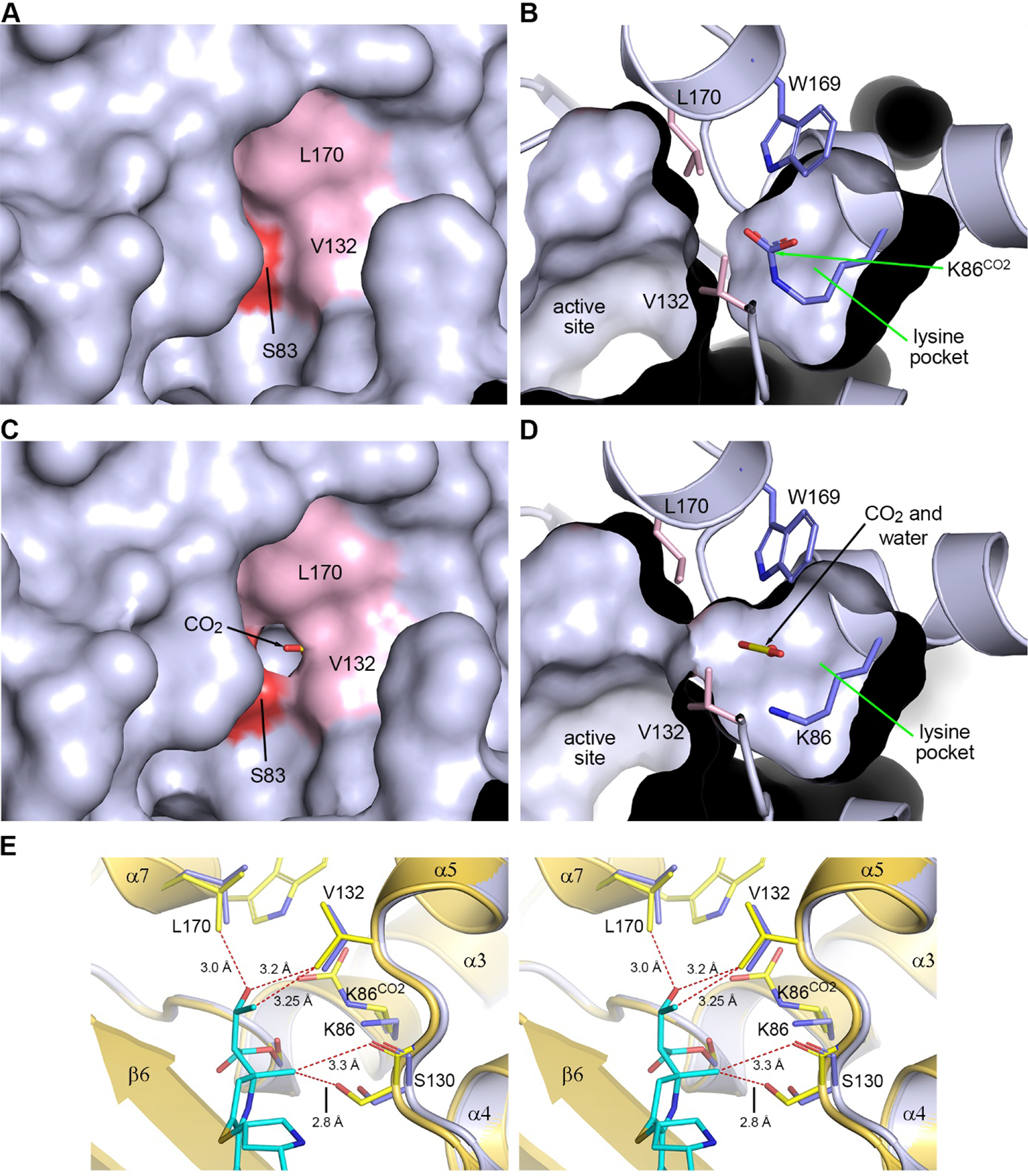

Previous results suggest that formation of an OXA-58-carbapenem acyl-enzyme complex results in occlusion of the active site by the antibiotic,40 which should prevent any movement of CO2 and water into and out of the internal lysine pocket.35 However, we also have shown that in such complexes with other CHDLs, a channel forms between the milieu and the lysine pocket by the movement of one of the conserved residues (Val132 and Leu170) forming the hydrophobic cap, which would allow a water and CO2 to leave or enter the active site of the enzymes.32,33,35 To evaluate whether such a channel is formed in OXA-58, solvent accessible molecular surfaces were generated for apo-OXA-58 and the OXA-58-NA-1–157 complex at various time points. In apo-OXA-58 the hydrophobic cap is initially fully closed, and the carboxylated lysine is completely sequestered in the internal lysine pocket (Figure 6A,B). During the early time points of OXA-58 acylation by NA-1–157 (1.5 and 5 min), the cap remains closed but at 10 min, a small hole opens in two of the monomers. By 20 min the hole is clearly open in all monomers, and the lysine pocket is accessible from the external solvent (Figure 6C,D). However, we do not observe any large-scale movement of either of the Val132 and Leu170 side chains. To understand how the hole forms in the hydrophobic cap, the 20 min structure was superimposed onto the apo-OXA-58 structure based on the main chain atoms of six residues spanning the catalytic Ser83 and Lys86 (residues 82–87) (Figure 6E). This superposition showed that there is a short nonbonded contact between the C5α-methyl group and the Ser130 side chain (2.8 Å), more than 0.4 Å shorter than the C–O nonbonded contact distance of 3.22 Å41 (Figure 6E). This pushes the serine and the α4-α5 loop approximately 0.5 Å outward. The inward-facing 6α-HE of NA-1–157 also generates close contacts with the Val132 and Leu170 side chains of the apoenzyme, which would push them away from the inhibitor. This increases the distances (by ∼0.3 Å) between the valine and leucine side chains (Figure 6E) and opens a channel allowing ingress and egress of water and CO2.

Figure 6. Solvent accessible surfaces in the active site.

(A) Apo-OXA-58, with the hydrophobic cap residues Val132 and Leu170 in pink and Ser83 in red. (B) Panel (A) rotated 90° about the vertical axis, showing a cutaway view into the lysine pocket. (C) The 20 min OXA-58-NA-1–157 complex, showing a hole in the hydrophobic cap. (D) Panel (C) rotated 90° about the vertical axis, showing the channel linking the lysine pocket with the active site. (E) Stereoview of the superposition of the 20 min OXA-58-NA-1–157 complex (blue) onto apo-OXA-58 (yellow). C–O and C–C nonbonded contact distances are 3.22 and 3.4 Å, respectively.41 Close nonbonded contacts between NA-1–157 and residues in apo-OXA-58 are shown as dashed red lines.

Catalytic Mechanism of the Interaction of NA-1–157 with OXA-58.

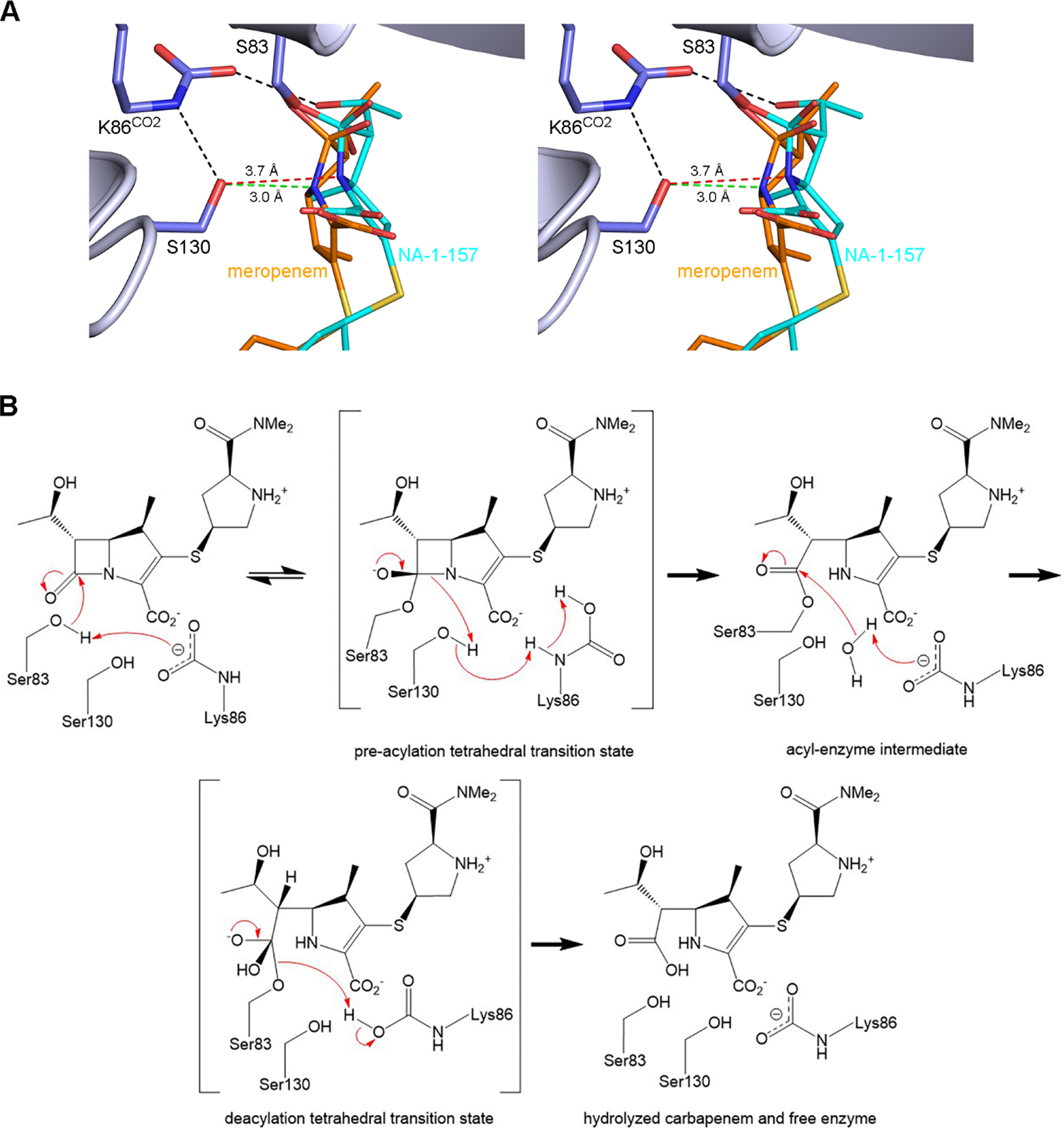

The combined kinetic, MS and structural analyses show that both acylation of OXA-58 by NA-1–157 and subsequent deacylation are impaired. It has been proposed that in class D β-lactamases prior to acylation, the carboxylated lysine is responsible for the initial activation of the catalytic serine by proton abstraction,18,19 and the observation of direct hydrogen-bonding interactions between one of the carbamate oxygen atoms and the Ser83 side chain in the apo-OXA-58 structure presented here (Figure 2B) supports that role. Subsequently, the activated deprotonated Ser83 attacks the carbonyl carbon of the β-lactam ring of the Michaelis complex to generate the tetrahedral transition state. The next step, opening of the β-lactam ring to form the acyl-enzyme intermediate, requires transfer of the proton abstracted from Ser83 by Lys86CO2 onto the amide nitrogen of the β-lactam ring. There are two ways in which this proton transfer could occur; (i) direct transfer from either the carbamate Nζ atom or one of the carboxylate oxygens, or (ii) proton shuttling through the nearby Ser130 side chain.19,42,43 Anything that impairs this transfer would interfere with acylation.

To gain an idea of the pre-acylation tetrahedral transition state complexes of OXA-58 with meropenem and NA-1–157, and which proton transfer mechanism is most likely, both carbapenems were docked into the apoenzyme structure (Figure 7A). Multiple simulations for both transition state models clearly demonstrated that direct proton transfer from Lys86CO2 to the N4 amide nitrogen of the β-lactam ring is highly unlikely since the distances between them are too long (4.6–5.2 Å). However, all elements for an efficient proton shuttle via Ser130 in the OXA-58-meropenem complex (Figure 7) are in place, namely hydrogen bonds between the Nζ atom of the Lys86CO2 carbamate and the Oγ of Ser130 (3.35 Å), and between the Oγ of Ser130 and the N4 atom of the β-lactam ring (3.0 Å), indicating that proton transfer and β-lactam ring opening most likely occur via this pathway. Multiple simulations of the OXA-58-NA-1–157 transition state model consistently placed the carbapenem approximately 0.7–1.0 Å from the position of meropenem in a direction away from Ser130 and the α4-α5 loop (Figure 7A). This is in agreement with the lateral repositioning observed in the acyl-enzyme crystal structures (Figure 4). In this model, the Nζ-Oγ distance is the same (3.35 Å) as in the meropenem complex, however, the Oγ-N4 distance is 3.7 Å (Figure 7A), which is too long for effective proton transfer from Ser130 to the β-lactam ring. This would hinder cleavage of the N4–C7 bond of the NA-1–157 β-lactam ring of the pre-acylation tetrahedral transition state and slow progression toward the acyl-enzyme intermediate. These data are supported by our kinetic and MS results, suggesting the formation of a reversible OXA-58-NA-1–157 pre-acylation covalent complex during inactivation (Figure 7B). Inefficient proton transfer during acylation would also result in the buildup of a protonated carbamate species, which is expected to lead to decarboxylation of the Lys86CO244,45 and hinder deacylation, since the carboxylated lysine is crucial for activation of a deacylating water molecule (Figure 7B). In addition, if the inward-facing 6α-HE in NA-1–157 forms a hydrogen bond with the carbamate group of Lys86CO2 (as observed in some monomers at early time points, and also in the OXA-58-NA-1–157 transition state model (Figure 7A)), this would increase the partial positive charge in the lysine pocket, lead to a localized drop in pH, destabilize the protonated carbamate and thus may also contribute to decarboxylation. Our kinetic results, showing that deacylation is the rate-limiting step in turnover of NA-1–157 by OXA-58, support this scenario. However, as deacylation does occur, albeit at a very slow rate (k3 = (9.1 ± 0.3) × 10−5 s−1, Table 2), this implies that either in a very small population of the enzyme the Lys86 remains carboxylated or some recarboxylation of decarboxylated Lys86 occurs. Potential sources of the CO2 required for this process could be the external milieu or the molecule temporarily retained in the lysine pocket after decarboxylation.

Figure 7. Molecular docking and catalytic mechanism.

(A) Stereoview of the pre-acylation tetrahedral transition state models for OXA-58 with meropenem and NA-1–157. Hydrogen bonds are shown as black dashed lines. The Ser130-N4 contact distances are shown as green and red dashed lines for meropenem and NA-1–157, respectively. (B) Mechanism of carbapenem hydrolysis by OXA-58.

CONCLUSIONS

Wide spread of CHDLs has resulted in dissemination of MDR A. baumannii isolates and compromised the utility of commercial carbapenems for treatment of infections caused by this pathogen. This, in turn, necessitates development of novel antibiotics. In the current study, we demonstrated that the C5α-methyl-substituted carbapenem NA-1–157 has potent activity against A. baumannii producing the OXA-58 CHDL. A competition experiment between nitrocefin and NA-1–157 showed that the compound efficiently inhibits nitrocefin hydrolysis by OXA-58 (kNA-1–157 = 0.55 ± 0.05 s−1). Single turnover kinetics demonstrated that acylation is biphasic, with the first 25% of the reaction proceeding through the fast phase (k2 fast = 1.0 ± 0.3 s−1), while the remaining majority (75%) progressed through the much slower phase (k2 slow = (8.6 ± 0.6) × 10−4 s−1). Of these two phases, only the fast phase of acylation takes place on a time scale similar to that of inactivation, which indicates that the majority of the enzyme is not acylated during the competition experiment. The jump dilution experiment with a short preincubation time confirmed that the majority of the inactivated OXA-58-NA-1–157 complex is reversible. MS analysis showed that within several minutes, all enzyme forms a covalent complex with NA-1–157. However, subsequent MS analysis of competition experiments demonstrated that the majority of this complex is reversible, in agreement with the jump dilution experiment and acylation kinetics. Such complex is likely a reversible tetrahedral intermediate, as was proposed for the interaction of NA-1–157 with the class A carbapenemase GES-5.27 The deacylation rate of the OXA-58-NA-1–157 acyl-enzyme complex was significantly (>2000-fold) impaired when compared to meropenem, a close structural analogue of NA-1–157 that is a substrate of OXA-58. The half-life of the deacylation reaction is >2 h, which is more than 4-fold longer than the bacterial duplication time; thus NA-1–157 can be regarded as an inhibitor of OXA-58 from the clinical perspective. Time-resolved X-ray crystallographic studies allowed for the observation of a dynamic continuum between the fully carboxylated Lys86CO2 in apo-OXA-58 and its decarboxylated form upon completion of the formation of the acyl-enzyme complex. The observed changes in the enzyme active site architecture upon its acylation by NA-1–157 provide a rationale for sluggish acylation and subsequent severely impaired deacylation of the acyl-enzyme complex.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial Strains and Growth Media.

Acinetobacter baumannii CIP 70.10 was cultured in Luria–Bertani medium supplemented with 30 μg/mL kanamycin to maintain the pNT221 plasmid with the genes encoding OXA-58, OXA-23, OXA-24/−40, OXA-48, OXA-51 or OXA-143 under the constitutive ISAba3 promoter.33,46

Enzyme Purification.

The OXA-58 β-lactamase was expressed and purified as reported earlier.40 Protein concentration was determined by measuring the OD280 (MW = 29,364 Da, ε = +42,400 M−1cm−1) and by the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce).

Determination of MICs.

The A. baumannii CIP 70.10 isogenic strains harboring the pNT221 vector expressing OXA-58 or other CHDLs were used for MIC determination. MICs of carbapenems were measured according to the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) standards as described earlier.47

Enzyme Kinetics.

A Cary 60 spectrophotometer (Agilent) or SFM stopped-flow (Bio-Logic) instrument was used for data collection, and data analysis was performed with Prism9 (GraphPad Software). All reactions were performed in buffer containing 100 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7, 50 mM sodium bicarbonate and 0.2 mg/mL bovine serum albumin unless otherwise stated. The reactions were carried out in triplicate at 22 °C.

Steady-State Kinetics.

Reactions containing an excess of NA-1–157 (20–100 μM) or meropenem (20–80 μM) were initiated with 1.4–7.6 μM OXA-58, and the OD difference was recorded at 298 nm. Control reactions were carried out in the absence of the enzyme to correct for nonspecific hydrolysis of NA-1–157. The value of kcat was calculated from the linear steady-state phase using the molar extinction coefficient (λ = 298 nm, Δε = −10,240 M−1cm−1 for NA-1–157;27 λ = 298 nm, Δε = −7200 M−1cm−1 for meropenem).

Determination of the Inactivation Parameters of NA-1–157, kNA-1–157 and KI.

In the competition experiment, reactions contained 0.32 nM OXA-58, varying concentrations of NA-1–157 (0.4–3 μM) and 50 μM reporter substrate nitrocefin (λ = 500 nm, Δε = +15,900 M−1cm−1). Hydrolysis of nitrocefin was followed by the change in absorbance, and the data were analyzed as previously described.27

Determination of the Acylation Rate Constant k2.

The change in absorbance over time was measured under single turnover conditions, where OXA-58 was in 5–15-fold molar excess over NA-1–157 (5–10 μM) or 3.4–28-fold molar excess over meropenem (10 μM) in the reaction. The progress curves were analyzed as previously described.27

Determination of the Rate Constants koff and k3.

The rate constant for the reversible reaction (koff) was measured with the jump dilution method.48 After 2–10 min preincubation of 240 nM OXA-58 with 3.7 μM NA-1–157 in reaction buffer, the recovery of enzyme activity was measured following a 500-fold dilution into 200 μM nitrocefin and compared with the uninhibited control reaction. The change in absorbance was monitored at 500 nm, and the progress curves were analyzed as previously described,48 where k represents the reactivation rate constant koff. To determine k3 for NA-1–157, 1 μM OXA-58 and 100 μM NA-1–157 were preincubated for 16 h to ensure that all enzyme was acylated, and the excess of compound was removed using a 7 kDa MWCO desalting Zeba column (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After a rapid and large dilution (4000-fold) into reaction buffer, aliquots were taken at different time points (0–24 h) to measure the recovery of enzyme activity with 200 μM nitrocefin. The control reaction without NA-1–157 was processed and measured the same way. The percentage of the recovered activity from the acyl-enzyme complex was calculated and plotted against time. Data were fit to the exponential equation as previously described.27 For meropenem, the k3 value was calculated according to the relationship k3 = (kcat × k2)/(k2 − kcat).

Electrospray Ionization-Liquid Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (ESI-LC/MS) Analysis.

In a 250 μL reaction, 2 μM OXA-58 and 10 μM NA-1–157 were mixed in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7, 50 mM sodium bicarbonate at 22 °C. After 5 min and 1 h, 80 μL aliquots were desalted using a 7 kDa MWCO Zeba spin column to remove the excess of NA-1–157, treated with a large excess of PQ-1–219 (2.6 mM) for 10 min and stored at −80 °C. Untreated aliquots were also collected. The control reaction contained no NA-1–157. Samples were analyzed with ESI-LC/MS using a DIONEX Ultimate 3000 system connected to a Bruker micrOTOF-QII mass spectrometer in positive-ion mode, utilizing Hystar 4.2 SR2 software as was reported earlier.49 The percentages of the apoenzyme (29,364 Da) and its complexed forms with the compounds in each reaction were calculated based on the relative intensity of their peak heights.

Crystallography.

Crystals of apo-OXA-58 were grown at 16 °C as previously reported.40 Apo-OXA-58 data were collected on SSRL beamline BL12–2. The images were processed and scaled with XDS50 and AIMLESS,51 and the structure solved by molecular replacement using MOLREP52 with apo-OXA-58 (PDB code 4oh0) as the starting model. The crystals are in space group P21 and contained four molecules in the asymmetric unit.

Time-resolved crystallography was performed by soaking apo-OXA-58 crystals in a 10 mM NA-1–157 cryo buffer (crystallization buffer +25% glycerol) for 1.5 min to 2.5 h. Diffraction data were collected and processed as described above. The structures were solved by molecular substitution using the partially refined apo-OXA-58 structure. Data collection and refinement statistics are given in Tables S2 and S3.

Molecular Docking Simulations.

Covalent docking simulations of meropenem and NA-1–157 to apo-OXA-58 to generate transition state intermediates were performed with ICM-Pro 3.9–3a.53 The apo-OXA-58 structure (PDB code 4oh0) was converted to an ICM object, and the 2.5 h OXA-58-NA-1–157 (PDB code 9d8c) structure was superimposed and used to define an initial position for the substrate binding site in the apo-OXA-58 receptor. The two carbapenems were subsequently docked to the receptor using a predefined reaction which forms the covalent C7–Oγ(Ser83) bond, generates a free hydroxyl anion at O7 and retains the N4–C7 bond of the β-lactam ring. The docking runs were performed multiple times, and the most energetically favored binding modes were extracted from ICM-Pro as pdb files.

All structural figures and solvent accessible molecular surfaces were generated with Pymol v2.6.0 (Schrodinger).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant 1R01AI155723 from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIH/NIAID) to SBV and JDB and grants 1R01AI174599 and 1R15AI142699 from the NIH/NIAID to JDB. Parts of this research were carried out at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), a national user facility operated by Stanford University on behalf of the U.S. Department of Energy. Use of SSRL is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract DE-AC02–76SF00515. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P30GM133894). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIGMS or NIH.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- CLSI

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute

- ESI-LC/MS

electrospray ionization-liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry

- rmsds

root mean squared deviations

- 6α-HE

6α-hydroxyethyl group

- MDR

multidrug resistant

- CHDLs

carbapenem-hydrolyzing class D β-lactamases

- MIC

minimal inhibitory concentration

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

The apo-OXA-58 and its complexes with NA-1–157 structure factors and atomic coordinates have been deposited in the PDB with PDB codes 9d78, 9d79, 9d7a, 9d7b, 9d7c, 9d7d and 9d8c. The authors will release the atomic coordinates and experimental data upon article publication.

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsinfecdis.4c00671.

MS analysis of OXA-58-NA-1–157 complexes, structures of apo-OXA-58 and its complex with NA-1–157, residual F0-Fc and 2 F0-Fc electron density and polder difference maps of OXA-58-NA-1–157 complexes, superposition of class D β-lactamases showing free CO2 in the active sites, rmsd comparison of OXA-58 structures, and data collection and refinement statistics for OXA-58-NA-1–157 complexes (PDF)

Contributor Information

Marta Toth, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556, United States.

Nichole K. Stewart, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556, United States

Ailiena O. Maggiolo, Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, Stanford University, Menlo Park, California 94025, United States

Pojun Quan, Department of Chemistry, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas 75275, United States.

Md Mahbub Kabir Khan, Department of Chemistry, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas 75275, United States.

John D. Buynak, Department of Chemistry, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas 75275, United States

Clyde A. Smith, Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, Stanford University, Menlo Park, California 94025, United States; Department of Chemistry, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305, United States

Sergei B. Vakulenko, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556, United States

REFERENCES

- (1).Murray CJL; Ikuta KS; Sharara F; Swetschinski L; Robles Aguilar G; Gray A; Han C; Bisignano C; Rao P; Wool E; Johnson SC; Browne AJ; Chipeta MG; Fell F; Hackett S; Haines-Woodhouse G; Kashef Hamadani BH; Kumaran EAP; McManigal B; Achalapong S; Agarwal R; Akech S; Albertson S; Amuasi J; Andrews J; Aravkin A; Ashley E; Babin F-X; Bailey F; Baker S; Basnyat B; Bekker A; Bender R; Berkley JA; Bethou A; Bielicki J; Boonkasidecha S; Bukosia J; Carvalheiro C; Castañeda-Orjuela C; Chansamouth V; Chaurasia S; Chiurchiù S; Chowdhury F; Clotaire Donatien R; Cook AJ; Cooper B; Cressey TR; Criollo-Mora E; Cunningham M; Darboe S; Day NPJ; De Luca M; Dokova K; Dramowski A; Dunachie SJ; Duong Bich T; Eckmanns T; Eibach D; Emami A; Feasey N; Fisher-Pearson N; Forrest K; Garcia C; Garrett D; Gastmeier P; Giref AZ; Greer RC; Gupta V; Haller S; Haselbeck A; Hay SI; Holm M; Hopkins S; Hsia Y; Iregbu KC; Jacobs J; Jarovsky D; Javanmardi F; Jenney AWJ; Khorana M; Khusuwan S; Kissoon N; Kobeissi E; Kostyanev T; Krapp F; Krumkamp R; Kumar A; Kyu HH; Lim C; Lim K; Limmathurotsakul D; Loftus MJ; Lunn M; Ma J; Manoharan A; Marks F; May J; Mayxay M; Mturi N; Munera-Huertas T; Musicha P; Musila LA; Mussi-Pinhata MM; Naidu RN; Nakamura T; Nanavati R; Nangia S; Newton P; Ngoun C; Novotney A; Nwakanma D; Obiero CW; Ochoa TJ; Olivas-Martinez A; Olliaro P; Ooko E; Ortiz-Brizuela E; Ounchanum P; Pak GD; Paredes JL; Peleg AY; Perrone C; Phe T; Phommasone K; Plakkal N; Ponce-de-Leon A; Raad M; Ramdin T; Rattanavong S; Riddell A; Roberts T; Robotham JV; Roca A; Rosenthal VD; Rudd KE; Russell N; Sader HS; Saengchan W; Schnall J; Scott JAG; Seekaew S; Sharland M; Shivamallappa M; Sifuentes-Osornio J; Simpson AJ; Steenkeste N; Stewardson AJ; Stoeva T; Tasak N; Thaiprakong A; Thwaites G; Tigoi C; Turner C; Turner P; van Doorn HR; Velaphi S; Vongpradith A; Vongsouvath M; Vu H; Walsh T; Walson JL; Waner S; Wangrangsimakul T; Wannapinij P; Wozniak T; Young Sharma TEMW; Yu KC; Zheng P; Sartorius B; Lopez AD; Stergachis A; Moore C; Dolecek C; Naghavi M Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).O’Neill J Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations. The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance; Government of the United Kingdom, 2016. (accessed on July 12, 2024). [Google Scholar]

- (3).Price R O’Neill report on antimicrobial resistance: funding for antimicrobial specialists should be improved. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2016, 23, 245–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Rice LB Federal funding for the study of antimicrobial resistance in nosocomial pathogens: no ESKAPE. J. Infect. Dis. 2008, 197, 1079–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Gedefie A; Demsiss W; Belete MA; Kassa Y; Tesfaye M; Tilahun M; Bisetegn H; Sahle Z Acinetobacter baumannii biofilm formation and its role in disease pathogenesis: a review. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 3711–3719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Giammanco A; Cala C; Fasciana T; Dowzicky MJ Global assessment of the activity of tigecycline against multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens between 2004 and 2014 as part of the tigecycline evaluation and surveillance trial. mSphere 2017, 2, e00310–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Mohd Sazlly Lim S; Zainal Abidin A; Liew SM; Roberts JA; Sime FB The global prevalence of multidrug-resistance among Acinetobacter baumannii causing hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia and its associated mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Infect. 2019, 79, 593–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Tacconelli E; Carrara E; Savoldi A; Harbarth S; Mendelson M; Monnet DL; Pulcini C; Kahlmeter G; Kluytmans J; Carmeli Y; Ouellette M; Outterson K; Patel J; Cavaleri M; Cox EM; Houchens CR; Grayson ML; Hansen P; Singh N; Theuretzbacher U; Magrini N; Aboderin AO; Al-Abri SS; Awang Jalil N; Benzonana N; Bhattacharya S; Brink AJ; Burkert FR; Cars O; Cornaglia G; Dyar OJ; Friedrich AW; Gales AC; Gandra S; Giske CG; Goff DA; Goossens H; Gottlieb T; Guzman Blanco M; Hryniewicz W; Kattula D; Jinks T; Kanj SS; Kerr L; Kieny MP; Kim YS; Kozlov RS; Labarca J; Laxminarayan R; Leder K; Leibovici L; Levy-Hara G; Littman J; Malhotra-Kumar S; Manchanda V; Moja L; Ndoye B; Pan A; Paterson DL; Paul M; Qiu H; Ramon-Pardo P; Rodríguez-Baño J; Sanguinetti M; Sengupta S; Sharland M; Si-Mehand M; Silver LL; Song W; Steinbakk M; Thomsen J; Thwaites GE; van der Meer JW; Van Kinh N; Vega S; Villegas MV; Wechsler-Fördös A; Wertheim HFL; Wesangula E; Woodford N; Yilmaz FO; Zorzet A Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 318–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).CDC. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2019. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Atlanta, GA, CDC; 2019. (accessed on July 25, 2024). [Google Scholar]

- (10).Vrancianu CO; Gheorghe I; Czobor IB; Chifiriuc MC Antibiotic resistance profiles, molecular mechanisms and innovative treatment strategies of Acinetobacter baumannii. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Bush K; Jacoby GA Updated functional classification of β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 969–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Bush K The ABCD’s of b-lactamase nomenclature. J. Infect. Chemother. 2013, 19, 549–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Ramirez MS; Bonomo RA; Tolmasky ME Carbapenemases: transforming Acinetobacter baumannii into a yet more dangerous menace. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Docquier JD; Mangani S Structure-function relationships of class D carbapenemases. Curr. Drug Targets 2016, 17, 1061–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Dona D, Guure C, Chaillon A, Twint SS, Rylance J, Silva R, Diaz JV, Bertagnolio S 2004. Global rate of antibiotic use, coinfections, resistance and clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients receiving antibiotics in 65 countries worldwide; ECCMID Global: Barcelona, Spain, April 27–30, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Poirel L; Naas T; Nordmann P Diversity, epidemiology, and genetics of class D β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 24–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Higgins PG; Perez-Llarena FJ; Zander E; Fernandez A; Bou G; Seifert H OXA-235, a novel class D b-lactamase involved in resistance to carbapenems in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 2121–2126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Golemi D; Maveyraud L; Vakulenko S; Samama JP; Mobashery S Critical involvement of a carbamylated lysine in catalytic function of class D b-lactamases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001, 98, 14280–14285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Golemi D; Maveyraud L; Vakulenko S; Tranier S; Ishiwata A; Kotra LP; Samama J-P; Mobashery S The first structural and mechanistic insights for class D β-lactamases: evidence for a novel catalytic process for turnover of β-lactam antibiotics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 6132–6133. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Drawz SM; Bonomo RA Three decades of β-lactamase inhibitors. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 23, 160–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Butler MS; Henderson IR; Capon RJ; Blaskovich MAT Antibiotics in the clinical pipeline as of December 2022. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 2023, 76, 431–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Krajnc A; Lang PA; Panduwawala TD; Brem J; Schofield CJ Will morphing boron-based inhibitors beat the b-lactamases? Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2019, 50, 101–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Jacobs LMC; Consol P; Chen Y Drug discovery in the field of b-lactams: an academic perspective. Antibiotics (Basel) 2024, 13, 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Papp-Wallace KM; McLeod SM; Miller AA Durlobactam, a broad-spectrum serine b-lactamase inhibitor, restores sulbactam activity against Acinetobacter species. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, S194–S201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Gupta R; Al-Kharji N; Alqurafi MA; Nguyen TQ; Chai W; Quan P; Malhotra R; Simcox BS; Mortimer P; Brammer Basta LA; Rohde KH; Buynak JD Atypically modified carbapenem antibiotics display improved antimycobacterial activity in the absence of β-lactamase inhibitors. ACS Infect. Dis. 2021, 7, 2425–2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Smith CA; Stewart NK; Toth M; Quan P; Buynak JD; Vakulenko SB The C5a-methyl-substituted carbapenem NA-1–157 exhibits potent activity against Klebsiella spp. isolates producing OXA-48-type carbapenemases. ACS Infect. Dis. 2023, 9, 1123–1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Stewart NK; Toth M; Quan P; Beer M; Buynak JD; Smith CA; Vakulenko SB Restricted rotational flexibility of the C5a-methyl-substituted carbapenem NA-1–157 leads to potent inhibition of the GES-5 carbapenemase. ACS Infect. Dis. 2024, 10, 1232–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Morrison JF; Walsh CT The behavior and significance of slow-binding enzyme inhibitors. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. 1988, 61, 201–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Zandi TA; Townsend CA Competing off-loading mechanisms of meropenem from an L,D-transpeptidase reduce antibiotic effectiveness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2021, 118, No. e2008610118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Chiou J; Cheng Q; Shum PT; Wong MH; Chan EW; Chen S Structural and functional characterization of OXA-48: insight into mechanism and structural basis of substrate recognition and specificity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Triboulet S; Dubee V; Lecoq L; Bougault C; Mainardi JL; Rice LB; Etheve-Quelquejeu M; Gutmann L; Marie A; Dubost L; Hugonnet JE; Simorre JP; Arthur M Kinetic features of L,D-transpeptidase inactivation critical for b-lactam antibacterial activity. PloS One 2013, 8, No. e67831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Toth M; Smith CA; Antunes NT; Stewart NK; Maltz L; Vakulenko SB The role of conserved surface hydrophobic residues in the carbapenemase activity of the class D β-lactamases. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2017, 73, 692–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Smith CA; Antunes NT; Stewart NK; Toth M; Kumarasiri M; Chang M; Mobashery S; Vakulenko SB Structural basis for carbapenemase activity of the OXA-23 β-lactamase from Acinetobacter baumannii. Chem. Biol. 2013, 20, 1107–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Smith CA; Stewart NK; Toth M; Vakulenko SB Structural insights into the mechanism of carbapenemase activity of the OXA-48 β-lactamase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e01202–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Stewart NK; Toth M; Stasyuk A; Vakulenko SB; Smith CA In crystallo time-resolved interaction of the Clostridioides difficile CDD-1 enzyme with avibactam provides new insights into the catalytic mechanism of class D β-lactamases. ACS Infect. Dis. 2021, 7, 1765–1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Lohans CT; Freeman EI; Groesen EV; Tooke CL; Hinchliffe P; Spencer J; Brem J; Schofield CJ Mechanistic insights into b-lactamase-catalysed carbapenem degradation through product characterisation. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Stewart NK; Smith CA; Antunes NT; Toth M; Vakulenko SB Role of the hydrophobic bridge in the carbapenemase activity of class D b-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e02191–02118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Tooke CL; Hinchliffe P; Beer M; Zinovjev K; Colenso CK; Schofield CJ; Mulholland AJ; Spencer J Tautomer-specific deacylation and Ω-loop flexibility explain the carbapenem-hydrolyzing broad-spectrum activity of the KPC-2 b-lactamase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 7166–7180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Lahiri SD; Mangani S; Jahic H; Benvenuti M; Durand-Reville TF; De Luca F; Ehmann DE; Rossolini GM; Alm RA; Docquier JD Molecular basis of selective inhibition and slow reversibility of avibactam against class D carbapenemases: a structure-guided study of OXA-24 and OXA-48. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 10, 591–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Smith CA; Antunes NT; Toth M; Vakulenko SB Crystal structure of carbapenemase OXA-58 from Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 2135–2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Bondi A van der Waals volumes and radii. J. Phys. Chem. 1964, 68, 441–451. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Bou G; Santillana E; Sheri A; Beceiro A; Sampson JM; Kalp M; Bethel CR; Distler AM; Drawz SM; Pagadala SR; van den Akker F; Bonomo RA; Romero A; Buynak JD Design, synthesis, and crystal structures of 6-alkylidene-2’-substituted penicillanic acid sulfones as potent inhibitors of Acinetobacter baumannii OXA-24 carbapenemase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 13320–13331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Paetzel M; Danel F; de Castro L; Mosimann SC; Page MG; Strynadka NC Crystal structure of the class D b-lactamase OXA-10. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000, 7, 918–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Johnson SL; Morrison DL Kinetics and mechanism of decarboxylation of N-arylcarbamates. Evidence for kinetically important zwitterionic carbamic acid species of short lifetime. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972, 94, 1323–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Ruelle P; Kesselring UW; Hô NT. Ab initio quantum-chemical study on drug decomposition in the solid state preparations: Part II. Decarboxylation mechanism of the carbamic acid molecule. J. Mol. Struct. Theochem. 1985, 124, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- (46).Antunes NT; Lamoureaux TL; Toth M; Stewart NK; Frase H; Vakulenko SB Class D β-lactamases: are they all carbapenemases? Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 2119–2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Stewart NK; Toth M; Alqurafi MA; Chai W; Nguyen TQ; Quan P; Lee M; Buynak JD; Smith CA; Vakulenko SB C6 Hydroxymethyl-substituted carbapenem MA-1–206 inhibits the major Acinetobacter baumannii carbapenemase OXA-23 by impeding deacylation. mBio 2022, 13, No. e0036722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Copeland RA; Basavapathruni A; Moyer M; Scott MP Impact of enzyme concentration and residence time on apparent activity recovery in jump dilution analysis. Anal. Biochem. 2011, 416, 206–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Toth M; Stewart NK; Smith CA; Lee M; Vakulenko SB The L,D-transpeptidase Ldt(Ab) from Acinetobacter baumannii is poorly inhibited by carbapenems and has a unique structural architecture. ACS Infect. Dis. 2022, 8, 1948–1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Kabsch W XDS. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2010, 66, 125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Evans PR; Murshudov GN How good are my data and what is the resolution? Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2013, 69, 1204–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Vagin A; Teplyakov A MOLREP: an automated program for molecular replacement. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1997, 30, 1022–1025. [Google Scholar]

- (53).Abagyan R; Totrov M; Kuznetsov D ICMA new method for protein modeling and design: Applications to docking and structure prediction from the distorted native conformation. J. Comput. Chem. 1994, 15, 488–506. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.