Abstract

In this review, we summarize and review reforms to the mental health service in the United Kingdom from 1999 to the present. Our analysis is based on government documents describing the reforms and providing guidelines for their implementation. In addition, we summarize prospective studies of psychosis from the first episode and early treatment studies on the basis of existing systematic reviews. The UK mental health reforms have attracted major government funding and have been used to commission specialized (“functional”) community teams for people with severe mental illness. The reforms include changes to services for first-episode psychosis, which have attracted considerable consumer support. The UK service reforms are continuing, with the aim of providing services fit for the 21st century.

Medical subject headings: mental health services, health care reform, Great Britain, national health programs, schizophrenia

Abstract

Dans cette critique, nous résumons et passons en revue les réformes apportées au service de santé mentale du Royaume-Uni de 1999 à aujourd'hui. Notre analyse reposait sur des documents du gouvernement qui décrivent les réformes et présentent des directives sur leur mise en œuvre. Nous résumons en outre des études prospectives de psychoses depuis le premier épisode, et des études en début de traitement fondées sur des critiques systématiques existantes. Les réformes de la santé mentale au R.-U. ont attiré un financement important de l'État et ont permis de doter des équipes communautaires spécialisées («fonctionnelles») pour les personnes atteintes d'une maladie mentale grave. Les réformes comprennent des modifications des services offerts dans le cas d'un premier épisode de psychose, ce qui attire énormément d'appui des consommateurs. Les réformes des services au R.-U. se poursuivent et visent à offrir des services adaptés au XXIe siècle.

Introduction

The British government has recently embarked upon a radical plan for nationwide reform of its mental health services, a key feature of which is the implementation of functional community psychiatric services, including early intervention, crisis resolution and assertive outreach teams. In this paper we explain these national policy reforms, to highlight the significance of early intervention for psychosis in the new policy and to describe early intervention services in England.

Policy reforms

National Service Framework for Mental Health

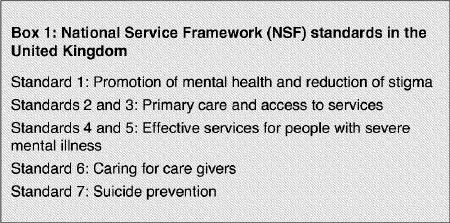

The National Service Framework for Mental Health was issued in 1999.1 Its intention is to set national standards for mental health services based on the best available evidence, supported by new investment of resources and backed by new legislation suited to modern patterns of service delivery (Box 1). It describes the kinds of services that will be needed to meet the standards and sets target dates for achieving milestones, with an ultimate goal of meeting all the standards over a 10-year period.

Box 1.

The National Health Service plan

The next important step was taken in July 2000, when the government published a plan for the National Health Service,2 setting out its intentions for the next 3 years. Much of the plan concerned structural and cultural changes for health services as a whole, but it identified 3 clinical priorities: coronary artery disease, cancer and mental health. The government announced in the plan an extra annual investment of over £300 million by the year 2003/04 to “fast-forward” the National Service Framework for Mental Health. Commitments on implementing specialized community psychiatric teams became more specific. The plan's targets for December 2004 included the following:

1000 newly graduated primary care workers

500 “gateway” workers (providing brief expert assessment and intervention in the area of mental health and directing patients to the appropriate services if neccesary)

50 early intervention services

335 crisis resolution teams

50 additional assertive outreach teams, bringing the total to 220

women-only day services

700 staff to support care givers

200 long-term beds

more suitable accommodation for 400 people currently in high-security hospitals

300 prison in-reach staff (providing dedicated treatment to the prison population with any mental health problems, employed by local mental health services)

development of a care plan at the time of release for every prisoner with serious mental illness

140 secure places and 75 step-down places for people with dangerous and severe personality disorder

In March 2001, the Department of Health published more detailed guidance for local services in the form of the Mental Health Policy Implementation Guide,3 which includes a model service specification for specialized community services, including early intervention in psychosis.

Significance of early intervention in the new policy

A key feature of the nationwide reform of mental health services was the implementation of 50 early intervention services by 2004. The aim was that by that time, every young person with a first episode of psychosis would receive the early and intensive support they need from a specialist team, which would continue to help them through the first 3 years of their illness.2

The Mental Health Policy Implementation Guide3 sets out who the early intervention service is for, what it is intended to achieve and what it does; it also outlines management and operational procedures and provides references to the evidence. The new services will also create an important opportunity to address key research questions provided by the UK's new National Institute of Mental Health in England and will provide a unique opportunity to conduct major large-scale research in this area.

Early intervention in the United Kingdom

What is early intervention?

Early intervention can be conceptualized as a series of preventive strategies comprising 3 interlinking components: early detection of emerging psychosis, a reduction in delay to first treatment and provision of sustained intervention during the “critical period” of 3–5 years following the first diagnosis.

Rationale for early intervention for psychosis

The critical period hypothesis

The scientific rationale for earlier intervention in cases of psychosis is now overwhelming. A great deal is known about the long-term trajectories of psychosis and their biologic and psychosocial influences. Delay in first treatment is robustly linked to poor early outcome.4 In addition, long-term follow-up studies have clearly shown that the outcome at 2 to 3 years strongly predicts outcome 20 years later5 and that disability “plateaus” by this time: the early phase is indeed a “critical period.”6 It is recognized that intense, sustained intervention is needed during this critical phase. A more powerful case for the UK service reform, however, appears to have come from consumers of mental health care, as outlined below.

The case for service reform

RETHINK, formally known as the National Schizophrenia Fellowship, is a campaigning UK mental health charity. This organization recently launched its campaign “Reaching People Early” (www.rethink.org/reachingpeopleearly), to bring to wider attention the poor state of services for young people with severe mental illness. RETHINK has identified a catalogue of concerns. In particular, they have highlighted the typical delay of 12 months between the onset of positive symptoms and first treatment;4 members describe how some of this delay occurs because of problems at the interface between primary and secondary care, including the lack of an “assertive” response when the diagnosis is first suggested. The suicide rate remains high, and young people in the early phase of illness are particularly at risk.2 RETHINK has pointed out that the incidence of schizophrenia begins to rise in the 15- to 18-year age group and does not respect the often impermeable service boundaries between Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services and adult services. Young people surveyed by RETHINK found services stigmatizing, therapeutically pessimistic and insensitive to specific youth concerns (for example, access to employment and training are high on their list of priorities).

This combination of consumer dissatisfaction and failure to provide evidence-based care at such a critical period in the evolution of the illness has brought about the zeitgeist in the United Kingdom that paved the way for radical service reforms.

The evidence base used in the UK context

At the time of writing, it is unclear the extent to which early detection, phase-specific treatments and the use of early intervention teams are underpinned by evidence of effectiveness. Marshall and Lockwood, in their Cochrane review,7 could not identify sufficient trials to draw any definitive conclusions. Although the substantial international interest in early intervention offers an opportunity to make major positive changes in psychiatric practice, this opportunity may be missed without a concerted international program of research to address key unanswered questions. However, a number of recent trials have attempted to shed light on these questions.

The PACE study, in Australia,8 showed that it is possible to delay and potentially avert progression to full diagnostic threshold for psychotic disorder in ultra high-risk individuals by using low-dose neuroleptics and cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT). This study was followed by that of Morrison et al,9 who demonstrated that the same result could be achieved with CBT alone. Using an epidemiologic case–control study of community education about psychosis, the TIPS project in Norway aims to reduce duration of untreated psychosis. The results have shown a reduction in duration of untreated psychosis and a concomitant reduction in psychosis symptoms at onset of treatment and 3-month follow-up.10 The OPUS study11 in Denmark is a randomized controlled trial which has shown an advantage of integrated, sustained treatment over usual treatment in terms of readmission. The Lambeth Early Onset (LEO) study12 is a similar randomized controlled trial in London, intended to evaluate the effectiveness of an early intervention service. This study has shown that a team delivering specialized care for patients with early psychosis is superior to standard care for maintaining contact with professionals and reducing readmissions to hospital.

Planning services: locations and catchment populations in England

The NHS plan target of 50 services for a population of 50 million people assumes an average catchment population for each service of 1 million. The Nottingham Centre of the DOSMD (Determinants of Severe Mental Illnesses and Disability) study13 found 24 new cases of “broad” diagnosis schizophrenia per 100 000 population per year. Given that about 85% of these cases will be in people 14–35 years of age, this leads to a predicted 7500 new cases per annum in England in the target age band for the new early intervention services. Each service, comprising a number of teams, will manage about 150 new cases and will provide support for about 3 years, giving a total caseload of about 450 per service. However, these are only average figures. The incidence of first-episode psychosis varies across the country, with higher rates in areas of social deprivation. It is important, therefore, that planning of the new teams takes this variation into account.

As of January 2004, approximately 30 teams had been established and were in various stages of development, and investment plans were in hand for the remainder.

Potential obstacles and solutions for early intervention

The foregoing is of course a hugely challenging agenda for local services. Furthermore, mental health professionals are by no means unanimous in accepting the need for reform. The national strategy is to continue to actively disseminate the evidence, both scientific and consumer based, and to put forward the argument that, even if the long-term benefits of early intervention are controversial, there is an overwhelming case for intervening early to prevent the problems that are known to occur in the early phase of psychosis. After all, intensive mental health services for people with severe mental illness (e.g., assertive community treatment, rehabilitation) kick in far too late, long after the horse has bolted: we need to ensure that our best treatments and service configurations are available early, when the long-term trajectories and disabilities first develop.14

Through its national research and development program, the UK Department of Health has commissioned an independent expert review of the evidence and has funded a long-term evaluation of the services (Birchwood M, Lester H. A national evaluation of early intervention services. Department of Health Policy Research Programme grant, 2005).

There remain the challenges of sustaining support for this radical reform program and, in particular, of trying to ensure that funding intended for mental health is not diverted elsewhere. In 2002/03, the government earmarked £75 million of the NHS allocation specifically for new service developments in mental health (assertive outreach, crisis resolution and early intervention teams).

Conclusions

The national reforms of services for young people with severe mental illness are radical, create major challenges for implementation and, when completed, will totally transform consumers' experience of the services. They will set the stage for research to determine what kind of early intervention is appropriate for achieving the outcomes that are possible with the current and developing range of treatments.14 Service engagement and consumer satisfaction are key outcomes of the UK service reforms in early psychosis.

Footnotes

Contributors: Both authors contributed substantially to drafting and revising the article, and each gave final approval for the article to be published.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Max Birchwood, School of Psychology, University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom; fax 0121 685-6049; m.j.birchwood.20@bham.ac.uk

Submitted Jan. 27, 2005; Revised June 16, 2005; Accepted June 20, 2005

References

- 1.Department of Health. A national service framework for mental health. London (UK): National Health Service; 1999.

- 2.Department of Health. The NHS plan. London (UK): National Health Service; 2000.

- 3.Department of Health. Mental health policy implementation guide. London (UK): National Health Service; 2001. Available: www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/05/89/60/04058960.pdf (accessed 2005 Aug 2).

- 4.Norman RM, Malla AK. Duration of untreated psychosis: a critical examination of the concept and its importance. Psychol Med 2001;31:381-400. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Harrison G, Hopper K, Craig T, Laska E, Siegel C, Wanderling J, et al. Recovery from psychotic illness: a 15-and 25-year international follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry 2001;178:506-17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Birchwood M, McGorry P, Jackson H. Early intervention in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1997;170:2-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Marshall M, Lockwood A. Early intervention for psychosis [Cochrane review]. In: The Cochrane Library; Issue 2, 2005. Oxford: Update Software.

- 8.McGorry PD, Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, Francey S, Cosgrave EM, et al. Randomized controlled trial of interventions designed to reduce the risk of progression to first episode psychosis in a clinical sample with subthreshold symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002;59:921-28. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Morrison AP, French P, Walford L, Lewis SW, Kilcommons A, Green J, et al. Cognitive therapy for the prevention of psychosis in people at ultra-high risk: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2004;185:291-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Melle I, Larsen TK, Haar U, Friis S, Johannessen JO, Opjordsmoen S, et al. Reducing the duration of untreated first-episode psychosis: effects of clinical presentation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004;61:143-50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Nordentoft M, Jeppesen P, Kassow P, Abel M, Petersen L, Thorup A, et al. OPUS project: a randomized controlled trial of integrated psychiatric treatment in first episode psychosis — clinical outcome improved. Schizophr Res 2002;53(3 Suppl 1):51.

- 12.Craig TKJ, Garety P, Power P, Rahman N, Colbert S, Fornells- Ambrojo M, et al. The Lambeth Early Onset (LEO) Team: randomised controlled trial of the effectiveness of specialised care for early psychosis. BMJ 2004;329:1067-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Harrison G, Croudcae T. Predicting the long-term outcome of schizophrenia. Psychol Med 1996;26:697-705. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Birchwood M. Early intervention in psychosis: A waste of valuable resources? Br J Psychiatry 2003;182:196-8. [DOI] [PubMed]