Abstract

This study systematically investigates the elastic anisotropy and thermodynamic properties of  phase in Mg-Zn alloys through first-principles calculations combined with Debye-Grüneisen theory. Three critical intermetallic phases - monoclinic Mg4Zn7, cubic MgZn2 (C-MgZn2), and hexagonal MgZn2 (H-MgZn2) phases were comparatively analyzed. Electronic structure analysis reveals that C-MgZn2 and H-MgZn2 exhibit stronger chemical bonding stability compared to Mg4Zn7. Phonon dispersion characteristics demonstrate distinct vibrational patterns: C-MgZn2 and Mg4Zn7 display enhanced phonon modes at both low and high frequency ranges, while H-MgZn2 shows predominant medium-frequency vibrational modes. Elastic anisotropy evaluation identifies Mg4Zn7 as moderately anisotropic, H-MgZn2 as significantly anisotropic, and C-MgZn2 as nearly isotropic. Thermodynamic analysis predicts superior thermal stability for C-MgZn2, evidenced by its highest Debye temperature (θd = 366 K), maximum sound velocity (vm=3.468 m/s), and minimal Grüneisen parameter (γ = 0.641), correlating with its exceptional thermal conductivity. In contrast, Mg4Zn7 exhibits the highest thermal expansion coefficient among the investigated phases. These findings establish fundamental structure-property relationships that advance the understanding of

phase in Mg-Zn alloys through first-principles calculations combined with Debye-Grüneisen theory. Three critical intermetallic phases - monoclinic Mg4Zn7, cubic MgZn2 (C-MgZn2), and hexagonal MgZn2 (H-MgZn2) phases were comparatively analyzed. Electronic structure analysis reveals that C-MgZn2 and H-MgZn2 exhibit stronger chemical bonding stability compared to Mg4Zn7. Phonon dispersion characteristics demonstrate distinct vibrational patterns: C-MgZn2 and Mg4Zn7 display enhanced phonon modes at both low and high frequency ranges, while H-MgZn2 shows predominant medium-frequency vibrational modes. Elastic anisotropy evaluation identifies Mg4Zn7 as moderately anisotropic, H-MgZn2 as significantly anisotropic, and C-MgZn2 as nearly isotropic. Thermodynamic analysis predicts superior thermal stability for C-MgZn2, evidenced by its highest Debye temperature (θd = 366 K), maximum sound velocity (vm=3.468 m/s), and minimal Grüneisen parameter (γ = 0.641), correlating with its exceptional thermal conductivity. In contrast, Mg4Zn7 exhibits the highest thermal expansion coefficient among the investigated phases. These findings establish fundamental structure-property relationships that advance the understanding of  phase stabilization mechanisms, providing critical guidance for designing high-performance Mg-Zn alloys through phase engineering strategies.

phase stabilization mechanisms, providing critical guidance for designing high-performance Mg-Zn alloys through phase engineering strategies.

Keywords: Elastic anisotropy, Thermal conductivity, Thermal expansion, Grüneisen parameter

Subject terms: Materials science, Theory and computation, Electronic structure

Introduction

Magnesium alloys are recognized as the lightest structural metallic materials, and they have been extensively researched due to their potential applications in the aerospace and automotive industries, as weight reduction is critical for lowering energy costs and carbon dioxide emissions1–4. However, the strength and performance of alloys largely depend on the precipitate phases in their microstructures, particularly the metastable G.P. zones (Guinier-Preston zones) as well as  phases and

phases and  precipitates. The formation, structure, and interaction of these metastable phases with the matrix directly affect the strengthening mechanisms and performance of the alloys. Nonetheless, there are still controversies regarding the structures and evolution mechanisms of these precipitates5,6.

precipitates. The formation, structure, and interaction of these metastable phases with the matrix directly affect the strengthening mechanisms and performance of the alloys. Nonetheless, there are still controversies regarding the structures and evolution mechanisms of these precipitates5,6.

The  precipitates are rod-shaped, grow parallel to the [0001]α−Mg direction, and form at high temperatures7. They significantly enhance the strength of magnesium alloys, but their complex crystal structures have not been fully defined. Gao and Nie8discovered through electron microscopy that

precipitates are rod-shaped, grow parallel to the [0001]α−Mg direction, and form at high temperatures7. They significantly enhance the strength of magnesium alloys, but their complex crystal structures have not been fully defined. Gao and Nie8discovered through electron microscopy that  rod-shaped precipitates actually have a monoclinic crystal structure similar to Mg4Zn7, rather than the traditional C14 structure. Their study also reported the orientation relationship between this structure and the magnesium matrix, which was confirmed by Singh and Tsai9. Rosalie10 specifically studied the orientation relationships of the C14 Laves phase MgZn2 and the Mg4Zn7 phase at grain boundaries and within grains. These two phases contain icosahedral quasicrystalline I phase atomic clusters in their structures. Within the twin boundaries, the orientation of the C14 Laves phase MgZn2 relative to the matrix is (11–20)α−Mg||(01–10)C14.

rod-shaped precipitates actually have a monoclinic crystal structure similar to Mg4Zn7, rather than the traditional C14 structure. Their study also reported the orientation relationship between this structure and the magnesium matrix, which was confirmed by Singh and Tsai9. Rosalie10 specifically studied the orientation relationships of the C14 Laves phase MgZn2 and the Mg4Zn7 phase at grain boundaries and within grains. These two phases contain icosahedral quasicrystalline I phase atomic clusters in their structures. Within the twin boundaries, the orientation of the C14 Laves phase MgZn2 relative to the matrix is (11–20)α−Mg||(01–10)C14.

Hongbo Xie11 finally determined the internal structure of  phase : it consists of two distinct two-dimensional unit cells (a rhombus structure with a 72-degree angle and an equilateral hexagonal structure with a 72-degree angle), which are arranged periodically along the direction of the fivefold symmetry axis. These 2D structures self-assemble into nanodomains containing 2D fivefold symmetry, C14, and C15 structures. The phase is neither a traditional crystal nor a known quasicrystal.

phase : it consists of two distinct two-dimensional unit cells (a rhombus structure with a 72-degree angle and an equilateral hexagonal structure with a 72-degree angle), which are arranged periodically along the direction of the fivefold symmetry axis. These 2D structures self-assemble into nanodomains containing 2D fivefold symmetry, C14, and C15 structures. The phase is neither a traditional crystal nor a known quasicrystal.

Bendo et al.12 confirmed through HAADF-STEM that in addition to C14 MgZn2 and monoclinic Mg4Zn7,  precipitates exhibit various crystal structures. These structures consist of elongated hexagonal units of Mg6Zn7 and rhombic units of MgZn2, forming complex two-dimensional arrangements that include C14 and C15 Laves phases, quasi-crystals, and their approximants. Wang13, Liu14, Cheng15, and Du Cheng16 studied the structure of this

precipitates exhibit various crystal structures. These structures consist of elongated hexagonal units of Mg6Zn7 and rhombic units of MgZn2, forming complex two-dimensional arrangements that include C14 and C15 Laves phases, quasi-crystals, and their approximants. Wang13, Liu14, Cheng15, and Du Cheng16 studied the structure of this  phase using first-principles calculations combined with the cluster expansion (CE) method, finding that the

phase using first-principles calculations combined with the cluster expansion (CE) method, finding that the  phase consists of monoclinic Mg4Zn7, cubic MgZn2 (C-MgZn2), and hexagonal MgZn2 (H-MgZn2), and pointed out that over-aging transforms these phases fully into (H-MgZn2).

phase consists of monoclinic Mg4Zn7, cubic MgZn2 (C-MgZn2), and hexagonal MgZn2 (H-MgZn2), and pointed out that over-aging transforms these phases fully into (H-MgZn2).

Yi Yang17 conducted an in-depth analysis of the precipitation kinetics of magnesium-1.7at.% zinc alloy aged at 150 °C and 200 °C by comprehensively using characterization techniques such as thermoelectric power (TEP), X-ray diffraction, atom probe tomography (APT), and transmission electron microscopy. The study revealed that during the early aging stage, the  phase (rod-like precipitates) predominates, while in the over-aged stage, the

phase (rod-like precipitates) predominates, while in the over-aged stage, the  phase (plate-like precipitates) takes the lead. Based on classical nucleation and growth theory, the research developed models suitable for rod-like and plate-like precipitates, detailing the competitive relationship between the two types of precipitates. Finally, a time-temperature-transformation (TTT) diagram for this alloy system was proposed, providing new insights and theoretical support for understanding the precipitation behavior in magnesium-zinc alloys.

phase (plate-like precipitates) takes the lead. Based on classical nucleation and growth theory, the research developed models suitable for rod-like and plate-like precipitates, detailing the competitive relationship between the two types of precipitates. Finally, a time-temperature-transformation (TTT) diagram for this alloy system was proposed, providing new insights and theoretical support for understanding the precipitation behavior in magnesium-zinc alloys.

The development of high-performance magnesium-zinc alloys necessitates fundamental understanding of phase evolution mechanisms. Although extensive studies have characterized rod-shaped

phase evolution mechanisms. Although extensive studies have characterized rod-shaped  (Mg4Zn7) and plate-like

(Mg4Zn7) and plate-like  precipitates in Mg-Zn systems, critical knowledge gaps persist. To address these challenges, we employ density functional theory (DFT) coupled with Debye-Grüneisen theory for systematic evaluation of three dominant

precipitates in Mg-Zn systems, critical knowledge gaps persist. To address these challenges, we employ density functional theory (DFT) coupled with Debye-Grüneisen theory for systematic evaluation of three dominant  phase variants: monoclinic Mg4Zn7, cubic MgZn2(C-MgZn2), and hexagonal MgZn2 (H-MgZn2). This work specifically targets three unresolved issues: (1) quantifying the chemical bonding disparities governing phase stability, (2) decoding the correlation between elastic anisotropy and precipitate morphology evolution, and (3) establishing thermodynamic fingerprints (Debye temperature, Grüneisen parameter) for phase selection predictions. Our computational strategy integrates electronic structure analysis, phonon dispersion calculations, and anisotropic elasticity modeling, providing multiscale insights to reconcile existing experimental controversies .

phase variants: monoclinic Mg4Zn7, cubic MgZn2(C-MgZn2), and hexagonal MgZn2 (H-MgZn2). This work specifically targets three unresolved issues: (1) quantifying the chemical bonding disparities governing phase stability, (2) decoding the correlation between elastic anisotropy and precipitate morphology evolution, and (3) establishing thermodynamic fingerprints (Debye temperature, Grüneisen parameter) for phase selection predictions. Our computational strategy integrates electronic structure analysis, phonon dispersion calculations, and anisotropic elasticity modeling, providing multiscale insights to reconcile existing experimental controversies .

Theoretical methods and computational details

Zener first proposed the anisotropy coefficient A factor for cubic lattices18:

| 1 |

The anisotropic constants AB and AG, which can be evaluated based on the bulk modulus and shear modulus, were introduced by Chung and Buessem19 in 1967, refining Zener’s model. However, these three anisotropy factors neglect the influence of elastic stiffness and are only applicable to cubic crystal systems.

| 2 |

| 3 |

Shivakumar20 introduced a comprehensive anisotropy index AU, which can be used to analyze anisotropy coefficients in hexagonal, trigonal, monoclinic, and other crystal systems. When AU = 0, the material is isotropic; when AU > 0, the material is anisotropic.

| 4 |

The shear anisotropy factors21 A1, A2, and A3 are calculated using the following formulas, representing the shear anisotropy factors on the (100), (010), and (001) planes, respectively. The crystal is isotropic only when A1 = A2 = A3=1:

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 |

Based on the first-principles and the Debye–Grüneisen model theory22, the free energy G can be calculated by ignoring electronic entropy:

| 8 |

| 9 |

| 10 |

| 11 |

| 12 |

The non-harmonic effects of lattice vibrations can be expressed through the Grüneisen parameter:

| 13 |

The Debye temperature θd can be obtained, and the Grüneisen parameter can be used to calculate the isochoric heat capacity, isobaric heat capacity, and thermal expansion coefficient through the Debye–Grüneisen model:

| 14 |

| 15 |

|

16 |

The thermal conductivity kmin is a characteristic of the material, indicating its ability to conduct heat. Cahill and Pohl23 suggest that the minimum thermal conductivity can be calculated as follows:

| 17 |

This study is based on the Vienna Ab-initio Simulation Package VASP v.6.3.2(https://www.vasp.at/)24 within the framework of density functional theory (DFT), employing the projector augmented wave (PAW) pseudopotential method25 and the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional in the generalized gradient approximation (GGA)26 to describe the exchange-correlation interactions while accounting for electron spin effects. The cutoff energy for the plane wave basis set is set to 400 eV, and Brillouin zone integration is carried out using Gamma point sampling with a 4 × 4 × 1 k-point grid. During structural optimization, the atomic coordinates and cell volumes of all unit cells are relaxed using the Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno (BFGS)27 self-consistent algorithm until the forces on all atoms decrease to below 0.015 eV/Å. For the elements Mg and Zn, the outermost electron configurations are Mg: s²p⁰ and Zn: d¹⁰p², respectively.

Phonopy v.2.37.0(https://phonopy.github.io/phonopy/)28 is used to perform phonon calculations on three phases using the finite displacement method.Utilizing linear response theory, the stress-strain method with an optimized high-efficiency strain matrix set (OHESS)29 was employed to compute the elastic constants and mechanical properties of the MgZn2 phase under linear strain, using Liu’s ELASTOOL v.3.62(https://github.com/gmp007/elastool) software package30. Visualization was performed using the VESTA v.3.5.8(https://jp-minerals.org/vesta/en/download.html) software package31.The thermodynamic properties of the phases are fitted using the Debye-Grüneisen theory in combination with phonon velocities and Debye temperatures calculated from the elastic properties.

Results and discussions

Stability of the  -phase

-phase

According to the previous research10–13, the phase is a mixed structure of cubic C15 Laves phase MgZn2, hexagonal C14 Laves phase MgZn2, and monoclinic Mg4Zn7 phase.The structural model is shown in Fig. 1. As shown in Table 1, the formation energy difference among the three phases is 0.3 KJ/mol, with the lowest formation energy phase being H-MgZn2 and the highest being Mg4Zn7 phase. The phase with C14 structure is H-MgZn2. From the perspective of formation energy, the phase transformation could possibly be from the Mg4Zn7 phase and C-MgZn2 phase to H-MgZn2 phase16.

Fig. 1.

Crystal structures of C-MgZn2, H-MgZn2, Mg4Zn7.

Table 1.

Optimized structures and formation energy cohesion energies of C-MgZn2, H-MgZn2, Mg4Zn7.

| lattice constant(Å) | formation energy(KJ/mol) | cohesive energy (KJ/mol) | Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | ||||

| C-MgZn2 | 7.341 | 7.341 | 7.341 | -12.820 | 98.143 | This work |

| H-MgZn2 | 5.223 | 5.223 | 8.566 | -12.965 | 97.998 | This work |

| 5.221 | 5.221 | 8.503 | -13.41 | - | Ref.16 | |

| 5.230 | 5.230 | 8.470 | -11.47 | 134.22 | Ref.32 | |

| 5.187 | 5.187 | 8.561 | -13.186 | 132.617 | Ref.33 | |

| 5.251 | 5.251 | 8.445 | -7.9 | - | Ref.34 | |

| Mg4Zn7 | 25.960 | 5.240 | 14.280 | -12.618 | 118.040 | This work |

| 26.304 | 5.287 | 14.141 | -13.32 | - | Ref.34 | |

| 26.484 | 5.190 | 14.185 | -13.02 | - | Ref.16 | |

From the density of states (DOS) diagrams, the DOS charts of the three phases show the distribution of electronic states near the Fermi level. For the C-MgZn2 phase (Fig. 2a): Near the Fermi level, the DOS shows a significant peak, indicating a large number of electronic states within this energy range. In addition, the ELF diagram demonstrates the degree of localization of electrons in the lattice structure, with a high pairing probability (ELF = 0.6) for the electron-like gas type, which is associated with covalent or metallic bonding in the crystal. The high DOS near the Fermi energy level as well as the relatively high bonding electrons in the C-MgZn2 phase suggest that the electronic structure favors the formation of stable chemical bonds, which enhances the stability of the system.

Fig. 2.

Electronic density of states (DOS) and electron localization function (ELF) of C-MgZn2 (a), H-MgZn2 (b), Mg4Zn7 (c).

For the H-MgZn2 phase (Fig. 2b): close to the Fermi energy level, the peak of the density of states (DOS) decreases slightly, but remains significant. The electron localization function (ELF) plot shows the highest pairing probability (ELF = 0.5) for the electron-like gas type. This indicates the formation of strong ionic or metallic bonds between Mg-Zn in the H-MgZn2 phase35. Despite a slight decrease in the density of states, the high bonding electrons make the H-MgZn2 phase more stable33.

For the Mg4Zn7 phase (Fig. 2c): close to the Fermi energy level, the peak of the density of states (DOS) is similar to that of Fig. 2(a), and the stability of the Mg4Zn7 phase is similar to that of C-MgZn2. The electron localization function (ELF = 0.8) plot shows a relatively high degree of complete localization of electrons in the lattice structure, which suggests a more homogeneous distribution of electrons in the Mg4Zn7 phase, with weaker interactions between the electrons and a weaker ability to form bonds. As a result, the Mg4Zn7 phase is less stable. Although the difference in formation energies between these three phases does not exceed 0.3 KJ/mol, the difference in electronic structure leads to the difference in their stability.

Figure 3 shows the phonon dispersion relations and phonon density of states for three different magnesium-zinc compounds (C-MgZn2, H-MgZn2, and Mg4Zn7). Figure 3(a) indicates that the phonon frequency distribution for each wave vector point ranges from 0 to approximately 10 THz, with a relatively dense dispersion relation. There are evident band crossings at some critical points, indicating that the energy levels of different phonon modes are close at these points, which may influence the thermal conductivity of the materials. In Fig. 3(b), the phonon dispersion range of H-MgZn2 is narrower, with frequencies concentrated from 0 to about 7 THz and significant band gaps, suggesting lower phonon scattering. Figure 3(c) shows that the phonon dispersion range of Mg4Zn7 is similar to that of C-MgZn2 but with denser dispersion curves, especially in the low-frequency range (0 to about 3 THz), indicating the presence of numerous low-frequency phonon modes.

Fig. 3.

Phonon dispersion relations for C-MgZn2 (a), H-MgZn2 (b), and Mg4Zn7 (c) and their phonon density of states.

Figure 3(d) displays multiple peaks in the phonon density of states curves for C-MgZn2 in the low-frequency range (0 to about 3 THz) and the high-frequency range (6 to approximately 10 THz). The density curve for H-MgZn2 has significant peaks in the low-frequency range (0 to about 2 THz) and the mid-to-high-frequency range (4 to approximately 7 THz). The density curve for Mg4Zn7 is the most complex, with multiple peaks in the low-frequency range (0 to about 3 THz), mid-frequency range (3 to 5 THz), and high-frequency range (6 to approximately 10 THz), indicating a large number of phonon modes across these frequency ranges.

In summary, C-MgZn2 and Mg4Zn7 have a greater number of phonon modes in the low-frequency and high-frequency ranges, while H-MgZn2 has significant phonon modes in the low-frequency and mid-frequency ranges. These differences may originate from their distinct crystal structures and are crucial for understanding the thermal conductivity and phonon scattering behavior of these materials. Contrary to the conventional view, our DFT-Debye analysis demonstrates that the bonding nature (ELF) and phonon mode distribution jointly determine phase dominance .

Elastic anisotropy of the -phase

-phase

As shown in Table 2, the elastic anisotropy of the C-MgZn2 phase is mild, but significant differences still exist at the microscopic scale. This anisotropy may affect its crystal structure and microstructure during phase transformation, such as the formation and distribution of rod-like precipitates ( phases)38.

phases)38.

Table 2.

Elastic anisotropy factors of C-MgZn2, H-MgZn2, Mg4Zn7 phases.

The elastic anisotropy factor AU of the H-MgZn2 phase is 1.479, which is much greater than 0, indicating that the H-MgZn2 phase exhibits strong anisotropy overall.The anisotropy (A3) of H-MgZn2 in the [0001] direction is significantly lower than the other directions, leading to more susceptible elastic strain relaxation along the c-axis direction. In the early stages of aging, the dominance of rod-like precipitates may be related to their elastic behavior, may stabilize rod-like precipitates during early aging by minimizing interfacial strain energy along the [0001]α-Mg direction.According to the classical nucleation theory, the anisotropic strain energy difference (ΔU∝E− 1) will contribute to the extension of the precipitated phase along the low-modulus direction (c-axis) and the formation of a plate  -phase, which is consistent with the results of the over-aging experiments in the literature39 where H-MgZn2 plate phases prevailed.The elastic anisotropy factor AU of the Mg4Zn7 phase is 0.109,indicating that it is also anisotropic overall. Although the degree of anisotropy of the Mg4Zn7 phase is not as strong as that of the H-MgZn2 phase, it is still significant.

-phase, which is consistent with the results of the over-aging experiments in the literature39 where H-MgZn2 plate phases prevailed.The elastic anisotropy factor AU of the Mg4Zn7 phase is 0.109,indicating that it is also anisotropic overall. Although the degree of anisotropy of the Mg4Zn7 phase is not as strong as that of the H-MgZn2 phase, it is still significant.

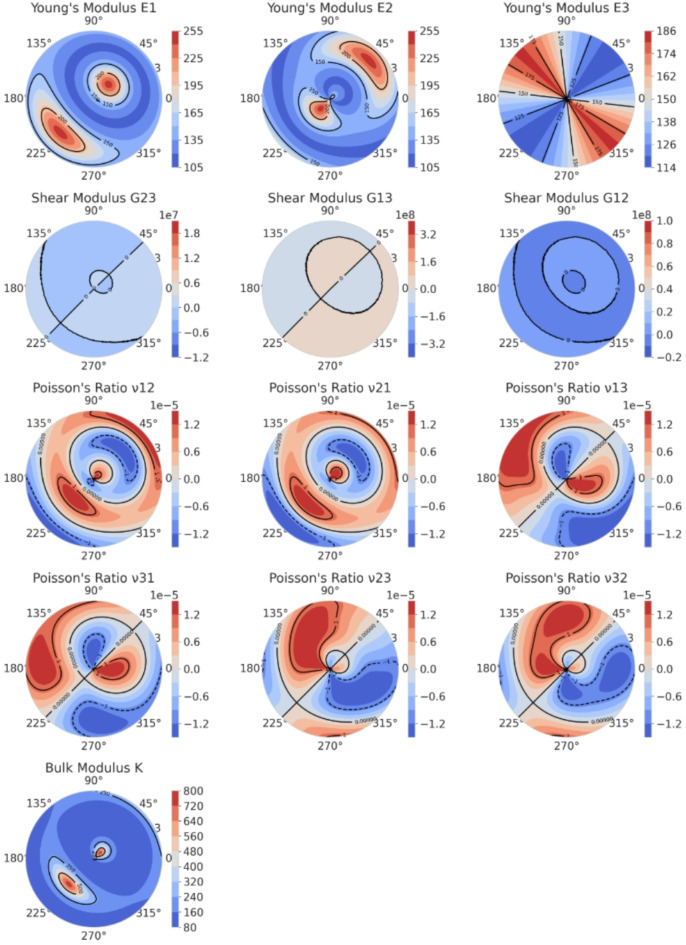

To more clearly analyze the elastic anisotropy of the three phases, the anisotropy of Young’s modulus (E), shear modulus (G), Poisson’s ratio (υ), and bulk modulus (K) for the C-MgZn2, H-MgZn2, and Mg4Zn7 phases is represented through Figs. 4 and 5, and 6, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Polar contour plots of Young’s modulus (E), shear modulus (G), Poisson’s ratio (υ), and bulk modulus(K)of C-MgZn2.

Fig. 5.

Polar contour plots of Young’s modulus (E), shear modulus (G), Poisson’s ratio (υ), and bulk modulus(K)of H-MgZn2.

Fig. 6.

Polar contour plots of Young’s modulus (E), shear modulus (G), Poisson’s ratio (υ), and bulk modulus(K)of Mg4Zn7.

From Fig. 4, it can be observed that the distribution of Young’s modulus (E) and shear modulus (G) for the C-MgZn2 phase shows a significant anisotropy. In the contour plot of Young’s modulus (E), the density and color variation of the contour lines in different directions indicates the changes in elastic modulus of the material in these directions. The plot shows that Young’s modulus is higher in some directions (such as 0° and 90°) and lower in others (such as 45° and 135°). This distribution pattern suggests that the material has a stronger resistance to external forces in these specific directions.

The contour plot of shear modulus (G) also demonstrates a clear anisotropy. In the contour plots of G23 and G13, the shear modulus is higher in certain specific directions and lower in others. This indicates that the material’s shear deformation capability varies in different directions. Among them, the distribution of G23 is relatively uniform, while in the distribution plots of G13 and G12, a higher shear modulus is visible near 0° and 90°, and a lower shear modulus near 45° and 135°. The contour plot of Poisson’s ratio (υ) shows how the ratio of lateral strain to axial strain changes in different directions for the C-MgZn2 phase. It is evident from Fig. 4 that there are significant differences in Poisson’s ratio in different directions. In the contour plots of υ13, υ31, υ23, and υ32, the pattern of changes is similar, indicating that the material’s deformation characteristics exhibit marked anisotropy in different directions across various types of Poisson’s ratio (the relationship between the longitudinal and transverse).

The contour plot of the bulk modulus (K) illustrates the material’s resistance to volumetric deformation in different directions. It is clear from the figure that the bulk modulus values differ significantly in different directions. In Fig. 4, the bulk modulus is higher in certain directions (such as 0° and 90°) and lower in other directions (such as 45° and 135°). This variation indicates that the material has a stronger resistance to external forces in these specific directions and weaker resistance in others.

Figure 5 shows the polar coordinate contour plots of Young’s modulus (E), shear modulus (G), Poisson’s ratio (υ), and bulk modulus (K) for the H-MgZn2 phase. It can be observed from Fig. 5 that the Young’s modulus of H-MgZn2 displays a notable anisotropy in different directions. The Young’s modulus in the three directions E1, E2, and E3 exhibits different distribution patterns, with E1 and E2 showing higher modulus values around 90°, and E3 showing relatively uniform values throughout the 360° range. This indicates that the phase has better elastic stability and consistency in the E3 direction, while it shows greater elastic variability in the E1 and E2 directions.

The shear modulus in the three directions G13, G23, and G12 also shows different distribution patterns from Fig. 5. The shear modulus in the G13 direction is relatively uniform across the 360° range, while the modulus in the G23 and G12 directions has higher values within specific angular ranges. This suggests that the phase has better shear stability in the G13 direction and exhibits more significant shear deformation in the G23 and G12 directions.

Figure 5 also exhibits Poisson’s ratio of H-MgZn2 in multiple directions, where the ratios in the v12, v21, v13, v23, v31, and v32 directions show different distribution patterns. Poisson’s ratio demonstrates a significant anisotropy in different directions, especially with the ratios in the v12 and v21 directions having higher values within certain angular ranges, indicating that the phase is prone to lateral contraction in these directions.

The bulk modulus (K), which reflects the material’s ability to resist volumetric strain, also shows a marked anisotropy in different directions according to Fig. 5. The bulk modulus is relatively uniform throughout the 360° range, suggesting that the phase has better volumetric stability in all directions.

Figure 6 shows the polar coordinate contour maps of the Young’s modulus (E), shear modulus (G), Poisson’s ratio (υ), and bulk modulus (K) of the Mg4Zn7 phase in different directions. The figure illustrates the Young’s modulus (E1, E2, E3) of the Mg4Zn7 phase in three different directions. From Fig. 6, it can be seen that there are significant differences in Young’s modulus in different directions. In the E1 direction: the Young’s modulus reaches its highest value of about 180 GPa at 135° and 315°, and its lowest value of about 45 GPa at 45° and 225°. In the E2 direction: the Young’s modulus reaches its highest value of about 180 GPa at 45° and 225°, and its lowest value of about 45 GPa at 135° and 315°. This indicates that the Young’s moduli in the E1 and E2 directions serve as complements to each other in symmetric angular distributions. In the E3 direction: the Young’s modulus is distributed relatively uniformly around the entire circumference, maintaining a value of about 114 GPa. This suggests that the Young’s modulus in the E3 direction is insensitive to changes in angle.

Figure 6 also shows the shear modulus (G23, G13, G12) of the Mg4Zn7 phase in three different shear directions. In the G23 direction: the shear modulus reaches its maximum value of about 3.2 GPa near 0° and 180°, and approaches 0 near 90° and 270°. In the G13 direction: the shear modulus reaches its maximum value of about 6.4 GPa near 90° and 270°, and approaches 0 near 0° and 180°. In the G12 direction: the shear modulus is distributed relatively uniformly around the entire circumference, maintaining a value of about 2 GPa. The Poisson’s ratio exhibits varying distributions in different directions. For instance, in the v12 direction, the Poisson’s ratio is close to 6 near 0° and 180°, and close to -6 near 90° and 270°. This indicates that forces applied in these directions result in corresponding maximum lateral contraction and expansion. Other Poisson’s ratio distributions show similar trends but with different directions and values. The bulk modulus is uniformly distributed around the entire circumference, maintaining a value of about 13,500 GPa. This indicates that the phase exhibits effective volumetric changes in response to forces applied in all directions.

The stark contrast in elastic anisotropy between C-MgZn2 and H-MgZn2 fundamentally governs their precipitation morphologies through strain energy minimization principles. For C-MgZn2, its near-isotropic elasticity (Young modulus in all directions, Figure.4) allows homogeneous nucleation of rod-like  precipitates along the low-energy [0001]α−Mg direction, as isotropic stiffness suppresses preferential growth directions. In contrast, H-MgZn2 exhibits extreme anisotropy with E1 (basal plane) vs. E3 (c-axis) (Figure.5). According to Eshelby’s inclusion theory40, the lower stiffness alongc-axis (E3/E1 = 0.63) reduces the strain energy penalty for plate-like

precipitates along the low-energy [0001]α−Mg direction, as isotropic stiffness suppresses preferential growth directions. In contrast, H-MgZn2 exhibits extreme anisotropy with E1 (basal plane) vs. E3 (c-axis) (Figure.5). According to Eshelby’s inclusion theory40, the lower stiffness alongc-axis (E3/E1 = 0.63) reduces the strain energy penalty for plate-like  precipitates extending along (0001) planes, consistent with TEM observations of {0001}α−Mg habit planes in over-aged alloys17.

precipitates extending along (0001) planes, consistent with TEM observations of {0001}α−Mg habit planes in over-aged alloys17.

Additionally, the shear anisotropy factors (A1 = 1.017, A2 = 1.017, A3 = 0.991 for H-MgZn2) indicate that shear deformation preferentially occurs on (0001) planes (G12 vs. G13, Figure.5). This facilitates dislocation glide along these planes during aging, providing nucleation sites for plate-like precipitates. These mechanistic insights reconcile the long-debated correlation between  phase anisotropy and precipitation morphology in Mg-Zn systems16.

phase anisotropy and precipitation morphology in Mg-Zn systems16.

Thermodynamic properties of the  -phase

-phase

The phonon velocity is a key physical quantity for assessing sound wave propagation in materials, reflecting density and elastic modulus. In Table 3, C-MgZn2 exhibits the highest sound velocity, indicating stronger interatomic forces and higher elastic modulus, which implies better rigidity and stability. H-MgZn2 has a slightly lower sound velocity, while Mg4Zn7 has the lowest, suggesting a more loosely packed crystal structure and weaker interatomic interactions, resulting in higher resistance to sound wave propagation. The average sound velocity (vm) in anisotropic materials can estimate thermal conductivity, reinforcing that C-MgZn2 has superior sound and thermal properties41.

Table 3.

Longitudinal speed of sound (vl), transverse speed of sound (vt), average speed of sound (vm), Débay temperature ( ), Débay velocity(

), Débay velocity( ), and Grüneisen parameter (γ) for C-MgZn2, H-MgZn2, Mg4Zn7 phase.

), and Grüneisen parameter (γ) for C-MgZn2, H-MgZn2, Mg4Zn7 phase.

| vl (km/s) | vt (km/s) | vm (km/s) | θd | ωD(km/s) | γ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-MgZn2 | 5.333 | 3.128 | 3.468 | 366.014 | 2.794 | 0.641 |

| H-MgZn2 | 4.686 | 2.648 | 2.945 | 312.959 | 2.389 | 0.701 |

| Mg4Zn7 | 4.450 | 2.409 | 2.688 | 287.938 | 2.198 | 0.768 |

The Debye temperature (θd) and Debye velocity (ωD) are crucial parameters for lattice vibrations and phonon transport. C-MgZn2 has the highest Debye temperature (366.014 K) and Debye velocity (2.794 km/s), indicating stronger thermal conductivity and smaller atomic spacing. H-MgZn2 and Mg4Zn7 have lower values, particularly Mg4Zn7 with θd = 287.938 K and ωD = 2.198 km/s, suggesting less efficient phonon transport.

The Grüneisen parameter describes temperature-dependent thermal properties. C-MgZn2 has the lowest Grüneisen parameter (0.641), indicating a smaller coefficient of thermal expansion and higher thermal conductivity. H-MgZn2 and Mg4Zn7 have higher parameters (0.701 and 0.768), suggesting larger thermal expansion and lower thermal conductivity.

Figure 7 shows the distribution of phonon velocities for C-MgZn2, H-MgZn2, and Mg4Zn7 materials at different angles θ and φ. Each chart is composed of three subplots, representing two transverse phonon modes (Transverse Mode 1 and Transverse Mode 2) and one longitudinal phonon mode (Longitudinal Mode). The color bar indicates the range of phonon velocities, varying from 3.0 km/s to 5.5 km/s.

Fig. 7.

Grouped phonon velocity thermograms for C-MgZn2, H-MgZn2, Mg4Zn7.

In Fig. 7(a)-(c), Transverse Mode 1 shows distinct peaks at specific angles with phonon velocities ranging from 2.8 to 3.8 km/s. Transverse Mode 2 exhibits more uniform distributions, with velocities from 3.0 to 4.2 km/s, showing enhancements at certain angles. The Longitudinal Mode has relatively uniform distributions with velocities from 3.6 to 5.5 km/s, also featuring noticeable enhancements at specific angles.

Figure 8(a) shows the temperature-dependent isochoric heat capacity (Cv) for C-MgZn2, H-MgZn2, and Mg4Zn7. C-MgZn2’s Cv rises sharply from near 0 K, moderates, and plateaus around 288.15 K, consistent with the Debye model. H-MgZn2 follows a similar trend but remains lower, suggesting more complex lattice vibrations and less heat absorption. Mg4Zn7’s Cv is significantly higher, rising rapidly at low temperatures and stabilizing around 2700 J/mol·K, indicating more low-frequency lattice modes and greater thermal energy absorption.

Fig. 8.

Isomeric heat capacity (a), isobaric heat capacity (b), thermal expansion (c) and thermal conductivity (d) of C-MgZn2, H-MgZn2, Mg4Zn7.

Figure 8(b) presents the temperature-dependent isobaric heat capacity (Cp) for the three phases. C-MgZn2’s Cp increases sharply from near 0 K, moderates, and plateaus around 288.15 K, aligning with the Debye model. Mg4Zn7’s Cp shows a gradual upward trend, reflecting the thermal excitation of lattice vibrations. At low temperatures, only low-frequency modes are excited, causing a rapid increase in Cp. As temperature rises, more modes are excited, leading to a linear increase and eventual stabilization.

Figure 8(c) shows the thermal expansion rates of C-MgZn2, H-MgZn2, and Mg4Zn7. C-MgZn2 has a very low thermal expansion rate, approximately 8 × 10− 6 K− 1, indicating minimal volume change with temperature. H-MgZn2’s rate is slightly higher at around 3.5 × 10− 5 K− 1, showing moderate thermal expansion. Mg4Zn7 has the highest rate, sharply increasing from low temperatures and stabilizing at about 1.7 × 10− 4 K− 1, indicating significant volume expansion when heated.

Figure 8(d) shows the thermal conductivities of C-MgZn2, H-MgZn2, and Mg4Zn7 as a function of temperature. All three phases exhibit a sharp rise from near 0 K to about 2000 K, then level off. C-MgZn2 has the highest thermal conductivity, stabilizing at around 0.30 W/m·K, due to its highest average sound velocity (vm), Debye temperature (θd), and Debye frequency (ωD), which reduce long-range phonon scattering. H-MgZn2 and Mg4Zn7 have lower thermal conductivities, stabilizing at 0.25 W/m·K and 0.20 W/m·K, respectively. The lower Grüneisen parameter (γ) in C-MgZn2 further reduces lattice-phonon scattering, enhancing thermal conductivity.

Conclusion

While prior studies have predominantly focused on the structural characterization of individual  phase components (e.g., C14 MgZn2, monoclinic Mg4Zn7 ), the novelty of this work lies in the first systematic comparison of three critical

phase components (e.g., C14 MgZn2, monoclinic Mg4Zn7 ), the novelty of this work lies in the first systematic comparison of three critical  phase variants (Mg4Zn7, C-MgZn2, H-MgZn2) through integrated electronic-phonon-thermodynamic analysis, revealing their structure-dependent anisotropy and stability mechanisms. Specifically, we uncover that:

phase variants (Mg4Zn7, C-MgZn2, H-MgZn2) through integrated electronic-phonon-thermodynamic analysis, revealing their structure-dependent anisotropy and stability mechanisms. Specifically, we uncover that:

C-MgZn2 and H-MgZn2 exhibit stronger chemical bonding stability compared to Mg4Zn7, suggesting their higher phase stability in Mg-Zn alloys.Distinct vibrational patterns are observed: C-MgZn2 and Mg4Zn7 exhibit enhanced phonon modes at low and high frequencies, whereas H-MgZn2 is dominated by medium-frequency modes, reflecting fundamental differences in lattice dynamics.

The near-isotropic elasticity of C-MgZn2 (AU=0.05) versus the extreme anisotropy of H-MgZn2 (AU=1.479) provides a mechanistic basis for their distinct precipitation morphologies (rod-like vs. plate-like).

C-MgZn2 displays superior thermal stability (θd = 366 K, vm = 3.468 m/s, γ = 0.641), indicating high thermal conductivity and low thermal vibration dissipation. In contrast, Mg4Zn7 has the highest thermal expansion coefficient (α = 3.0 × 10− 5K−¹), which may limit its high-temperature applications.

Author contributions

Zhiyong Youcontributed to the writing of the paper, data analysis, verification, and manuscript review.Shuaishuai Jin participated in data organization.Peide Han provided support in software resources and computational resources.Aoxue Jiang played a key role in the review and editing.Chunle Sun provided assistance in visualization, review, and editing.

Data availability

The authors ensure that the data supporting the findings of the study are available to Zhiyong You (youzhiy1486@163.com) and can be provided if needed.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Li, P., Hou, D., Han, E. H., Chen, R. & Shan, Z. Solidification of Mg–Zn–Zr alloys: Grain growth restriction, dendrite coherency and grain size. Acta Metall. Sin (Engl Lett). 33, 1477–1486 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang, J. et al. Dynamic precipitation and enhanced mechanical properties of ZK60 magnesium alloy achieved by low temperature extrusion. Mater. Sci. Engineering: A. 829, 142143 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jin, S. et al. First-principles study of Y, Ca microalloyed Mg-Zn alloy. Mater. Today Commun.41, 110936 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bao, L. et al. First-principles study on the interfacial bonding strength and segregation at Mg/MgZn2 matrix interface. J. Magnesium Alloys. 10.1016/j.jma.2022.12.010 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma, H. T. et al. The role of Ag, Ca, Zr and al in strengthening effects of ZK series alloys by altering G.P. Zones stability. Acta Mater.147, 42–50 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nie, J. F., Wilson, N. C., Zhu, Y. M. & Xu, Z. Solute clusters and GP zones in binary Mg–RE alloys. Acta Mater.106, 260–271 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao, X. & Nie, J. F. Characterization of strengthening precipitate phases in a Mg–Zn alloy. Scripta Mater.56, 645–648 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao, X. & Nie, J. F. Structure and thermal stability of primary intermetallic particles in an Mg–Zn casting alloy. Scripta Mater.57, 655–658 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh, A. & Tsai, A. P. Structural characteristics of Β1′ precipitates in Mg–Zn-based alloys. Scripta Mater.57, 941–944 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosalie, J. M., Somekawa, H., Singh, A. & Mukai, T. Orientation relationships between icosahedral clusters in hexagonal MgZn2 and monoclinic Mg4Zn7 phases in Mg-Zn(-Y) alloys. Phil. Mag.91, 2634–2644 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xie, H. et al. Self-Assembly of two unit cells into a nanodomain structure containing Five-Fold symmetry. J. Phys. Chem. Lett.9, 4373–4378 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bendo, A. et al. Characterisation of structural similarities of precipitates in Mg–Zn and Al–Zn–Mg alloys systems. Phil. Mag.99, 2619–2635 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang, D. et al. Crystal structure, energetics, and phase stability of strengthening precipitates in Mg alloys: A first-principles study. Acta Mater.158, 65–78 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu, S., Esteban-Manzanares, G. & LLorca, J. First-principles analysis of precipitation in Mg-Zn alloys. Phys. Rev. Mater.4, 093609 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng, D., Wang, K. & Zhou, B. C. First-Principles investigation of the Early-Stage precipitations in Mg-Sn and Mg-Zn alloys. in Magnesium Technology 2022 (eds Maier, P., Barela, S., Miller, V. M. & Neelameggham, N. R.) 281–290 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-92533-8_47. (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng, D., Wang, K. & Zhou, B. C. Crystal structure and stability of phases in Mg-Zn alloys: A comprehensive first-principles study. Acta Mater.242, 118443 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang, Y. et al. Revisiting precipitation kinetics in Mg-Zn alloy – a multi-characterization and modeling study. Acta Mater.260, 119276 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anisotropy in Single-Crystal Refractory Compounds.

- 19.Chung, D. H. & Buessem, W. R. The elastic anisotropy of crystals. J. Appl. Phys.38, 2010–2012 (1967). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ranganathan, S. I. & Ostoja-Starzewski, M. Universal elastic anisotropy index. Phys. Rev. Lett.101, 055504 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen, S. B., Chen, Y., Yan, W. J. & Gao, T. H. First-principles investigation of elastic anisotropy and thermal transport property of transition metal monosilicides CrSi, TiSi, and ZrSi under pressure. Mater. Today Commun.39, 108958 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tao, X. et al. Calculation of the thermodynamic properties of B2 AlRE (RE = Sc, Y, La, Ce–Lu). Phys. B. 399, 27–32 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cahill, D. & Pohl, R. Lattice vibrations and heat transport in crystals and glasses. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem.39, 93–121 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for Ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B. 54, 11169–11186 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B. 50, 17953–17979 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett.77, 3865–3868 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pfrommer, B. G., Côté, M., Louie, S. G. & Cohen, M. L. Relaxation of crystals with the Quasi-Newton method. J. Comput. Phys.131, 233–240 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Togo, A., Chaput, L., Tadano, T. & Tanaka, I. Implementation strategies in phonopy and phono3py. J. Phys. : Condens. Matter. 35, 353001 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu, Z. L. et al. Investigating elastic constants across diverse strain-matrix sets. Comput. Mater. Sci.230, 112521 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ekuma, C. E. & Liu, Z. L. ElasTool v3.0: Efficient computational and visualization toolkit for elastic and mechanical properties of materials. Comput. Phys. Commun.300, 109161 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Momma, K. & Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Cryst.44, 1272–1276 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mao, P., Yu, B., Liu, Z., Wang, F. & Ju, Y. Mechanical properties and electronic structures of MgCu2, Mg2Ca and MgZn2 Laves phases by first principles calculations. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China. 24, 2920–2929 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song, Y. et al. First-Principles investigations on structural stability, elastic properties and electronic structure of Mg32(Al,Zn)49 phase and MgZn2 phase. Crystals12, 683 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jain, A. et al. Commentary: the materials project: A materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Mater.1, 11002 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Becke, A. D. & Edgecombe, K. E. A simple measure of electron localization in atomic and molecular systems. J. Chem. Phys.92, 5397–5403 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu, M. M., Wen, L., Tang, B. Y., Peng, L. M. & Ding, W. J. First-principles study of elastic and electronic properties of MgZn2 and ScZn2 phases in Mg–Sc–Zn alloy. J. Alloys Compd.506, 412–417 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xie, Y. P., Wang, Z. Y. & Hou, Z. F. The phase stability and elastic properties of MgZn2 and Mg4Zn7 in Mg–Zn alloys. Scripta Mater.68, 495–498 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosalie, J. M. & Pauw, B. R. Form-free size distributions from complementary Stereological TEM/SAXS on precipitates in a Mg–Zn alloy. Acta Mater.66, 150–162 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li, X. D. et al. First-principles study of coherent interfaces of Laves-phase MgZn2 and stability of thin MgZn2 layers in Mg-Zn alloys. J. Alloys Compd.696, 109–117 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lurie, S., Volkov-Bogorodsky, D., Leontiev, A. & Aifantis, E. Eshelby’s inclusion problem in the gradient theory of elasticity: applications to composite materials. Int. J. Eng. Sci.49, 1517–1525 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang, K. et al. First-principles investigations on the electronic structures, polycrystalline elastic properties, ideal strengths and elastic anisotropy of U3Si2. Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 136, 409 (2021). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors ensure that the data supporting the findings of the study are available to Zhiyong You (youzhiy1486@163.com) and can be provided if needed.