Abstract

Objective

Mobile health (mHealth) interventions may be an efficacious strategy for promoting health behaviors among pediatric populations, but their success at the implementation stage has proven challenging. The purpose of this article is to provide a blueprint for using human-centered design (HCD) methods to maximize the potential for implementation, by sharing the example of a youth-, family-, and clinician-engaged process of creating an mHealth intervention aimed at promoting healthcare transition readiness.

Method

Following HCD methods in partnership with three advisory councils, we conducted semistructured interviews with 13- to 15-year-old patients and their caregivers in two phases. In Phase 1, participants described challenges during the transition journey, and generated ideas regarding the format, content, and other qualities of the mHealth tool. For Phase 2, early adolescents and caregivers provided iterative feedback on two sequential intervention prototypes. Data were analyzed using thematic analysis in Phase 1 and the rapid assessment process for Phase 2.

Results

We interviewed 11 youth and 8 caregivers. The sample included adolescents with a range of chronic health conditions. In Phase 1, participants supported the idea of developing an autonomy-building tool, delivering transition readiness education via social media style videos. In Phase 2, participants responded positively to the successive prototypes and provided suggestions to make information accessible, relatable, and engaging.

Conclusions

The procedures shared in this article could inform other researchers’ plans to apply HCD in collaboration with implementation partners to develop mHealth interventions. Our future directions include iteratively developing more videos to promote transition readiness and implementing the intervention in clinical care.

Keywords: adolescents, adherence/self-management, eHealth/mHealth/digital health, health promotion and prevention

For adolescents with chronic health conditions (CHC), the transition to adult healthcare can be difficult, confusing, and risky. Successful transition occurs when adolescents, with their families, develop the skills needed to engage with their healthcare tasks and services (Prior et al., 2014). Best practices suggest starting transition preparation between 12 and 14 years-old (White & Cooley, 2018). Unfortunately, only 23% of adolescents with CHC, ages 12–17 years, receive transition guidance (Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, 2020).

Mobile health (mHealth) interventions could reach more youth through less resource-intensive education (Low & Manias, 2019). However, most mHealth interventions for adolescents have struggled to progress from usability and efficacy trials to implementation (Majeed-Ariss et al., 2015). Involving patient partners in intervention design could improve implementation outcomes and benefit youth consultants themselves, by helping them feel valued, learn skills, and develop confidence and pride (Blower et al., 2020; Lopez et al., 2017; van Schelven et al., 2020).

The Practical, Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model (PRISM) provides a useful framework to guide the integration of perspectives of youth and their supporters into intervention design (Feldstein & Glasgow, 2008). PRISM prescribes iteratively incorporating patient and organizational perspectives to address implementation concerns through the entire research process. Consistent with PRISM, human-centered design (HCD) procedures offer practical steps for involving implementation partners in creating and implementing new interventions (Ideo.org, 2015). HCD consists of three phases: (1) Inspiration, when designers immerse themselves in a community’s challenges, experiences, and context to deeply understand what solutions are needed; (2) Ideation, the process of synthesizing information obtained in the Inspiration phase, generating intervention ideas, and building and testing iterative prototypes; and (3) Implementation, the stage of executing a solution in the real world. Design projects typically progress along these phases, although designers can revisit earlier stages. Research applications of HCD approaches to intervention design, evaluation, and implementation are emerging in the mHealth literature (e.g., Graham et al., 2019; Korpershoek et al., 2020), but examples with pediatric populations are needed to illustrate youth-friendly design procedures.

Our team used HCD to co-design a digital tool to enhance transition readiness in a pediatric hospital. We began by developing empathy for the healthcare transition journey (Inspiration), through interviews and focus groups with young adult patients, caregivers, and pediatric and adult clinicians (Sayegh et al., 2022). Through this formative work, we generated a problem statement that caregivers primarily managed adolescents’ healthcare, resulting in underdeveloped knowledge, skills, and confidence. Participants at this stage proposed a gamified mHealth intervention to empower younger adolescents (13- to 15-year-olds) to engage in their healthcare with greater autonomy (Ideation). In response to a topic nomination and ranking activity, participants also generated a list of content for the intervention to cover. However, we realized a gap in our understanding of the target age group since we had consulted with adults with knowledge of the adolescent experience, but not directly elicited feedback from early adolescents themselves. Therefore, we decided to revisit the Inspiration and Ideation phases with early adolescents and caregivers. The objective of this article is to illustrate the application of HCD with this population.

Methods

Participants and setting

This study occurred at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles (CHLA), a quaternary care pediatric hospital. The CHLA Center for Healthy Adolescent Transition (CHAT) convened a working group (this article’s co-authors, from the disciplines of psychology, public health, patient education, information technology, and self-advocacy) to develop technology-based transition solutions. The priority population was adolescents with CHC, as transition readiness is particularly vital for their health and quality of life. We partnered with patient, family, and clinician advisory councils throughout the project. In this study, participant eligibility included being a 13- to 15-year-old CHLA patient or their caregiver, and speaking English or Spanish.

Procedures

We sought a heterogeneous sample by reaching out to subspecialty and CHAT-affiliated clinicians to invite participants of diverse gender, race/ethnicity, CHC, and level of transition readiness. Once prospective participants expressed interest to clinicians, study personnel contacted caregivers to enroll those interested. The data referenced in this manuscript were collected as part of two studies approved by the CHLA Institutional Review Board (CHLA-19-00471; CHLA-21-00158). Caregivers and youth provided electronically signed informed consent/assent/permission.

We conducted semistructured interviews with adolescents and caregivers in two phases, in participants’ preferred language. Interview guides were informed by examples from The Human-Centered Design Toolkit (Ideo.org, 2015) and Vandekerckhove et al.’s (2020) “make” questions (e.g., prompting participants to draw representations of intervention ideas), “tell” questions (e.g., asking participants to verbally express preferences relevant to the intervention), and “enact” questions (e.g., supporting participants in interacting with prototypes in ways that resemble real-life use). Facilitating diverse methods for communicating ideas can make participatory design youth-friendly (Ergler, 2015).

In Phase 1, we focused on validating or revising the solution concept generated in our prior work (Sayegh et al., 2022) with representatives of the target age group. In Phase 2, we conducted iterative interviews with youth and caregivers to obtain feedback in response to two sequential prototypes. Both prototypes were generated via design sessions with patient advisory councils and shared with family and clinician advisory councils for further revision. Prototype 1 was a slide deck with an intervention description and four mock-ups of video concepts with plots, dialogue, and visuals. Prototype 2 consisted of three 30-s videos produced with the CHLA Department of Marketing and Communication (Figure 1). The videos aimed to empower patients to ask questions during their healthcare appointments. The first video we created showed a patient practicing the same skills she used to ask questions about her lunch order when asking her clinician about her health. In the second video we created, a patient stood in front of a colorful wall, pointing to text stating reasons why youth may struggle to speak up in their appointments. In the third video we created, two patients demonstrated strategies youth could use to prepare for their appointments (e.g., write questions ahead of time). Patient advisory council members signed releases of information prior to appearing in Prototype 2 videos, giving permission for these videos to be used and published for research and health education purposes.

Figure 1.

Prototype 2 video screenshots.

Analysis

We used thematic analysis to interpret Phase 1 feedback (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Three authors (C.S.S., J.Y., E.I.) developed a codebook based on initial collaborative review of the transcripts and two authors (C.S.S., J.Y.) independently coded each transcript in Dedoose Version 9.0.17. We calculated reliability (Κ = 0.74), generated themes, and summarized results in a one-page design brief (Kelley, 2020). We shared what we learned with the advisory councils, revising the brief with their feedback.

In HCD, the team’s focus can be depicted as a funnel (Martin, 2010). Early in the process, the problem to be solved and the solution to be created are slightly mysterious. Design teams seek broad knowledge, brainstorm expansively, and generate divergent ideas. As the process matures, the focus gets tighter, converging on an increasingly defined plan of action. In Phase 1, thematic analysis served the team’s objectives well, with an open coding process of verbatim transcripts to deeply explore participants’ views. In Phase 2, we sought a more focused analysis as the funnel narrowed. We determined rapid assessment (Beebe, 2014) was most appropriate for the more specific applied research questions at this stage. Rapid assessment is a useful method for designing interventions (Vindrola-Padros & Johnson, 2020). Rapid assessment involves transforming interview data into structured matrices to inform actionable results. C.S.S. or K.C.D. listened to each interview recording, took notes in a structured template, and included timestamps for illustrative quotations. We transferred data from the structured templates to a single matrix organizing all participant feedback. We generated themes by collaboratively reviewing and discussing data within two 2-hr whole-team meetings and shared resulting themes with advisory councils for feedback, iteratively after each, gathering feedback on each prototype. The individual interview data cannot be shared publicly due to privacy concerns.

Our research team included several members proficient in Spanish. In Phase 1, we completed one-way translation from Spanish to English and coded transcripts in English. In Phase 2, we completed the structured templates in English from Spanish audio-recordings, typing quotations in the original Spanish and translating to English. We did not use saturation as a guiding concept as its value is not central to the reflexive qualitative approaches implemented (Beebe, 2014; Braun & Clarke, 2021).

Results

Clinicians referred 30 patients to the study. Two caregiver/patient dyads declined participation after learning more about the study and 17 never returned calls. We enrolled 11 adolescents (Phase 1: n = 8; Phase 2: n = 6) and 8 caregivers (Phase 1: n = 6; Phase 2: n = 3). Three adolescents and one caregiver participated in both phases. In Phase 2, two youth and one caregiver provided feedback on Prototype 1. Four youth and two caregivers provided feedback on Prototype 2. All youth communicated in English. Six caregivers preferred English, two Spanish. Although any CHLA patient was eligible for the study, whether they received care for acute or chronic conditions, 100% of the sample had ≥1 CHC (Table 1: Demographics).

Table 1.

Participant demographics.

| Demographics | M (SD) | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Youth, n = 11 | – | – |

| Age, years | 14.09 (0.94) | – |

| Gender | – | – |

| Boy | – | 7 (63.64) |

| Girl | – | 4 (36.36) |

| Race/ethnicity | – | – |

| Latiné | – | 6 (54.55) |

| Non-Latiné Black | – | 0 (0.00) |

| Non-Latiné White | – | 2 (18.18) |

| Non-Latiné Asian | – | 1 (9.09) |

| More than one | – | 2 (18.18) |

| Subspecialty clinic (Some youth were enrolled in more than one) | ||

| Endocrinology | 4 (36.36) | |

| Neurology | 1 (9.09) | |

| Nephrology | 3 (27.27) | |

| Ophthalmology | 1 (9.09) | |

| Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition | 2 (18.18) | |

| Hematology and Oncology | 2 (18.18) | |

| Cardiology | 1 (9.09) | |

| Caregivers, n = 8 | – | – |

| Women | – | 8 (100.00) |

| Race/ethnicity | – | – |

| Latiné | – | 5 (62.50) |

| Non-Latiné White | – | 2 (25.00) |

| More than one | – | 1 (12.50) |

Phase 1

We generated themes describing participants’ perspectives on the autonomy-building problem identified in our prior study (Sayegh et al., 2022) and ideas for solutions. We summarized feedback into a design brief, with input from the advisory councils (Table 2).

Table 2.

Design brief one-pager.

| Problem statement | Adolescents’ healthcare is largely managed or taken care of by their caregivers or other adults like their care team (e.g., doctor, clinicians), because adults want to protect their children from poor health and stress. This leads to teens not knowing a lot about their health condition and not being ready to take a more active role in their healthcare as they get ready for adulthood. Early adolescents need an inviting introduction to begin getting more involved in managing their healthcare, but the solution should partner with caregivers, not replace them. |

| End user | Early adolescents (13- to 15-year-olds) with chronic health conditions. |

| Define the platform | Early adolescents are interested in learning transition readiness skills through watching short social media style videos on mobile devices. |

| What are the functionalities | Early adolescents would like to see short videos featuring relatable people sharing about what conditions they had, what happened to them, how they coped, etc. Some were interested in having ways of watching and discussing these videos with others. The only element of gamification that was supported was earning prizes for watching videos. Respondents tended to be more comfortable consuming content, rather than creating their own videos. |

| What is the content | How to learn more about your health condition, how to understand your medical treatment, how to ask questions about your health to clinicians and caregivers, how to cope with mental health ramifications of your health condition, how to schedule appointments, how to communicate with clinicians, and learn information about nutrition, sexual, and reproductive health. |

| What is the “Vibe” | Reassuring with relatable, age-appropriate content (e.g., not threatening them, but educating them; not overwhelming, more step-by-step). The vibe should be fun, interesting, with suspenseful drama that captures your interest. Not boring or like “reading a Wikipedia article.” Not too childish. Easy to use and interesting. Acknowledge caregivers’ roles. |

Theme 1a. Caregivers’ healthcare management inhibits youths’ opportunities to build autonomy. All participants provided confirming descriptions of caregivers managing healthcare for youth. For example, one youth said, “They’re the ones that make the calls and call the pharmacist, go pick up your meds, and all those things.” Similarly, a caregiver explained (translated):

“It is true that they aren’t involved… As a mother, I am the one who asks for the appointment. It’s me who has to say, ‘[Participant], that day we are going to have the appointment.’”

Adolescents explained that adults taking responsibility for healthcare kept them from taking a more active role. For example, a youth said:

“This age is when we should get to know more about our healthcare and prepare for when it’s just up to us. My parents, they haven’t been very open about sharing what healthcare really is. When I go to the hospital, they [clinicians] try to explain sometimes, but they usually explain it mostly to my parents.”

Theme 1b. Parents take responsibility to protect their children from poor health and stress. Participants provided additional context to the problem statement, beyond the detail described in our prior study (Sayegh et al., 2022). Participants explained that adults take care of everything healthcare-related to “protect” youth. A caregiver explained:

“I do tend to be, just with her, maybe because of her condition, I seem to be a little bit more protective. Or just do everything versus my other daughter who is now 22. I think she was more independent at an earlier stage than [Participant].”

Participants described protection in two ways. One was to ensure the healthcare tasks were completed for adolescents’ physical wellbeing. For example, one parent described a rare circumstance in this sample. Her son was insisting on a more active role in his healthcare, which made her uncomfortable:

“I have a teenager who wants to be completely independent. And so, I am involved with very little. You know, all I do is get the supplies and he does the rest. That’s not what I want to be doing. Because of the way my son is and the way things have evolved. That’s what we’re doing now. Even though that’s not what I agree with.”

This mother’s comment highlighted how many caregivers feel a tension between their desire to protect their child and the child’s growing independence, a concern echoed by family advisory council members reviewing Phase 1 feedback. However, youth reported a readiness to step out of that strong level of protection. A youth explained she wanted to be “just the same as like anyone else…because they’ll think I’m very fragile. I just want to be treated not very over-protective.”

The other protective goal was to give youth a “carefree” childhood. Both adults and youth were concerned that exposing adolescents to details about their condition or assigning them healthcare responsibilities could increase stress. Despite this concern, all participants reported that early adolescents should be exposed to information about their health and given opportunities to practice taking more responsibility over their healthcare. Nonetheless, they advised that interventions should avoid introducing topics in blunt or scary ways. For example, youth and caregivers agreed that adolescents need to think “everything’s just going to be ok” and that transition preparation should respect that frame of mind. Participants reported that youth should be given information and expected to be more involved in their healthcare, but in a way that is “not above their level” and with “appropriate explanation to a child.”

Theme 1c. Design the intervention thoughtfully for this developmental stage, given the variation in readiness across youth and need for ongoing caregiver involvement. Participant feedback and discussion with the advisory councils highlighted two considerations during intervention design specific to this early adolescent developmental stage. First, there is a range of readiness to learn more. Our councils concluded that the mHealth intervention should be able to adapt to different levels of readiness, interest, or motivation. Second, participants reported that it was important for the intervention to give youth a private space where their caregivers cannot jump in and take care of tasks for them, while acknowledging the ongoing role of caregivers. For example, a mother explained that it is important to “explain some stuff to them, listen. Especially with the important information about… their health and their wellbeing.” Councils distilled this feedback into a goal of designing an mHealth intervention to partner with caregivers, not replace them.

Theme 1d. Don’t build a gamified intervention, make social media videos instead. Rather than the gamified intervention previously proposed by young adults and key informants (Sayegh et al., 2022), early adolescents and caregivers suggested creating health education videos in the style of social media platforms, specifically TikTok and YouTube. For example, a youth recommended: “Videos … because we get bored …We just see something for 5 min and we instantly get bored. It has to be something with drama and suspense, but informational topics.” Participants favored videos as a more acceptable communication modality compared to written information. For example, a youth said, “videos because, well take it for example, maybe some people wouldn’t have the time to look at the article. Maybe they can just put the earbuds on and just hear the video from the person saying it.” A caregiver agreed, explaining that videos were “something fun that they want to do. It’s gonna be boring if it’s like a Wikipedia.” Although most participants expressed the greatest enthusiasm about health-related short videos, one youth gave a contradictory opinion. The youth said, about health education videos, “I’m gonna be honest. I would not watch that. It just sounds boring. [laughter].”

Despite participants describing an interest in learning about their health on social media platforms, only one had consumed health-related content online. This youth reported, “I did [search for health information] on TikTok, and I found videos of people with [my condition.] I found it very interesting.” Aside from her example, it appeared that early adolescents in this sample were not seeking health-related content nor were algorithms recommending this information.

Earlier in our design process, young adults, caregivers, and clinicians proposed a gamified intervention (Sayegh et al., 2022). Here, we were surprised that early adolescents were not making similar design suggestions. Participants described video games as popular recreation in this age range; however, no youth and only one parent participant independently recommended creating a game-like experience. Several participants described games with educational goals as better for elementary-age children. For example, one youth said:

“I feel like kids nowadays aren’t into doctor and nurse games and stuff like that. They do play grownup games such as Call of Duty. Like all those, like, teenager boy games and girl games and stuff. And those [healthcare care topics] don’t fall into a category of their wants, I guess.”

Theme 1e. Videos could help teens feel like they’re not the only ones with a health condition. Beyond communicating health information in a teen-friendly fashion, participants explained that social media style videos could help participants feel less alone. For example, a caregiver explained, “Last year at his middle school he was the only child… on campus that has diabetes. So, I know that he didn’t feel comfortable. Nobody wants to be different, especially in middle school.” Caregivers expressed hope that videos could help youth feel like they are not alone in dealing with difficult experiences. Participants recommended creating videos with relatable people who had managed the challenges of growing up with CHC.

Theme 1f. A social media mHealth intervention could promote connection. In addition to creating videos that help youth see they have common experiences with others, some participants suggested incorporating social elements into the intervention. For example, a youth suggested incorporating “voice chat for, like, movie nights where it shows something that involves living with the condition.” Another youth suggested, “text chats in it where people can talk… Like, chats where you get to really meet and expand with people on what condition you have and how it’s affected and just advice you can give to each other.” However, participants reported that most teens would likely passively watch the videos without interacting much with others. A youth explained, “Um, I don’t communicate with people on [TikTok]. I just scroll.”

Phase 2

Participants had broadly positive reactions to both prototypes. Using rapid assessment, we discerned key design principles from participants’ responses. The themes are bolded below (indicating in parentheses whether themes came from Prototype 1 or Prototype 2 feedback).

Theme 2a. Topics should be relatable, age-appropriate, and highlight skills youth can immediately use (Prototypes 1 and 2). Youth and caregivers agreed that the topic emphasized in the prototypes, asking questions in healthcare visits, was intimidating for youth and that early adolescence was the right time to learn this skill. Neither youth nor caregivers supported videos guiding early adolescents to order a refill from a pharmacy or schedule an appointment because they thought this would create unnecessary stress and was beyond their current responsibilities. They preferred other topics, including accepting your condition, planning for your safety, exercise, nutrition, and mental health.

Theme 2b. Balance the goal of creating short videos with taking sufficient time to convey a full idea (Prototypes 1 and 2). Participants suggested video lengths between 15 s and 3 min. Many indicated that information should be front-loaded because teens often scroll past videos after several seconds. A youth explained that Prototype 2 “had a lot of information very quick which is a good thing because if someone is just scrolling and then it pops up, they’ll be able to see quite a lot decently fast before they swipe.” However, several participants thought the videos in Prototype 2 (∼30 s each) felt “abrupt.” They explained that just as they were starting to understand the point, the videos ended, suggesting that a few more seconds would allow for meaningful education.

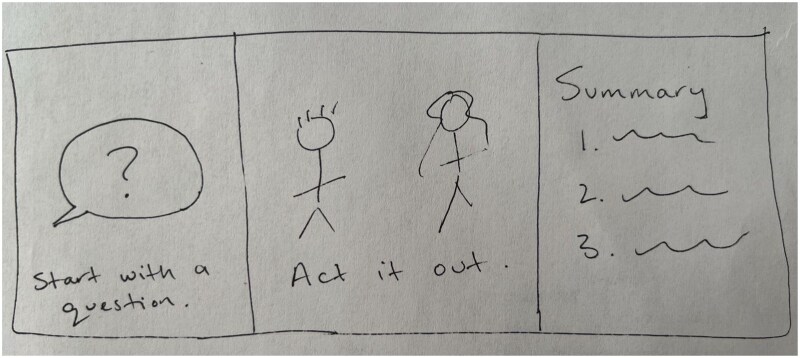

Theme 2c. Make the information easy to understand (Prototypes 1 and 2). Participants highlighted aspects of the prototypes that were confusing, such as the lack of a clarifying introduction to the topic or wrap-up of the main points. One youth’s sketch illustrated a recommendation made by many participants, to announce the video topic in the beginning, demonstrate the topic with a skit or tutorial, and summarize the actions youth could take at the end (Figure 2). Participants emphasized the importance of clear audio, not muffling dialogue with music, and closed captions or text to reinforce the message. They recommended communicating information in multiple ways within a video to increase understandability (e.g., show people doing something, verbalize an explanation, include bullet points).

Figure 2.

Participant sketch for future prototypes. Note. Participant sketch giving recommendation for future video formats (drawing re-created by the authors). Text reads: Start with a question. Act it out. Summary.

Theme 2d. Post videos on social media, but actively disseminate them within the hospital (Prototypes 1 and 2). Participants were in favor of publishing videos on TikTok, YouTube, and Instagram, and recommended asking influential accounts to share the videos (e.g., well-known medical device companies, popular patient-run accounts) or purchasing advertisements to promote the videos. However, they doubted many youth would find content this way, unless they were already motivated to learn about health. Participants recommended creating a dissemination campaign within the hospital, using posters and patient handouts with ‘quick response’ codes, playing the videos on televisions in waiting rooms and inpatient rooms, and having clinicians show videos during appointments and explain where they could watch more. Participants expressed ambivalence about posting the videos on the hospital website or disseminating links via patient portals. They found those strategies reasonable to try but did not predict much success reaching an audience that way because they did not typically engage with these communication channels.

Theme 2e. Avoid the pitfall of seeming like a commercial (Prototype 2). Although youth reported they sometimes appreciated social media advertisement videos when it was a highly relevant product, typically once they judged a video to be an ad, they would stop watching. Participants explained that qualities that made videos ad-like included emphasizing the hospital location because many commercials for medications or medical devices show hospital rooms or focusing too much on delivering educational information rather than having an “intriguing,” “natural,” or “on-trend” style. A youth recommended making videos “not so factual, like, in the sense where it’s straight up giving you information. I mean, a lot of things pop up that you see, and no one is interested in it, cause it’s boring. They don’t wanna see those things. They just wanna skip through it.”

Discussion

This article illustrates a partnership with patient, family, and clinician advisory councils to develop an mHealth transition readiness intervention using HCD procedures. Following the PRISM implementation framework (Feldstein & Glasgow, 2008), this study aimed to integrate the patient’s perspective into intervention development by engaging early adolescents and caregivers in the design process. Consistent with other research (Akre & Suris, 2014), participants confirmed that adults’ management of youths’ healthcare inhibits their autonomy-building. Participants reported caregivers aim to protect youth from stress and poor health, but that early adolescence is the right time to begin engaging teens in their own healthcare. However, in contrast to a gamified intervention proposed by young adults, families, and clinicians (Sayegh et al., 2022), early adolescents and their caregivers suggested that a social media style video intervention would be most engaging.

Our study highlights the benefits of following the PRISM framework (Feldstein & Glasgow, 2008) by iteratively obtaining feedback to align an intervention with the patient perspective. Partnering with youth to develop mHealth interventions with adolescents is a promising, but underutilized strategy, for enhancing implementation potential (Majeed-Ariss et al., 2015; van Schelven et al., 2020). Centering the patient perspective allowed us to quickly identify negative reactions to gamified transition readiness education, before investing time and resources in designing an unappealing intervention. Pivoting to a social media video intervention and eliciting feedback on prototypes helped the intervention be more acceptable for the target audience. With rapid iterative youth and caregiver feedback on prototypes, we learned that some of the initial suggestions for transition education topics were judged as inappropriate and intimidating for early adolescents. More relevant topics to this age group (e.g., accepting your diagnosis, planning for safety) were prioritized for additional videos. Furthermore, participants identified usability concerns regarding how well information could be heard, read, or understood. Participants also provided helpful guidance for implementing the videos in the hospital setting.

Although the divergent perspectives on gamification between young adults, families, and clinicians and early adolescents and caregivers should not be overinterpreted due to small sample sizes, the pivot to a social media style video intervention is congruent with current youth-technology trends, with the majority of 13- to 17-year-olds shifting to video-heavy social media platforms in recent years (Vogels et al., 2022). Although mHealth interventions are plentiful, leveraging social media for health is less common (Low & Manias, 2019). Recently, Psihogios et al. (2022) demonstrated feasibility and impressive reach with TikTok health education videos co-developed with adolescents and young adults with cancer, lending support to our participants’ suggestions. Given the fast pace of change in generational technology preferences and mHealth affordances, it is important to use methods like HCD that can efficiently and iteratively incorporate user feedback to align solutions with the problems and context patients experience in real-time.

Throughout the iterative phases of this study, participants explained the challenge of transferring responsibility from caregivers to adolescents. Parents were strongly motivated to protect their children, ensure their physical wellbeing, and shield them from the stress of self-management. This feedback highlighted the need to design an intervention that did not undermine or exclude caregivers. This user insight informed the content of the videos (e.g., we did not develop a script for one of the storyboards in Prototype 1 after feedback that the depiction of the caregiver was too caricatured). A design challenge we must resolve for future videos is better accessibility for caregivers speaking languages other than English. Sleath et al. (2016) demonstrated thoughtful inclusion of Spanish-speaking caregivers in their patient-engaged development of bilingual asthma education videos. Although we obtained feedback from Spanish-speaking caregivers, our video prototypes were produced in English with Spanish translations of the scripts available for review. Our next set of videos will further prototype strategies for making videos accessible to Spanish-speaking caregivers, such as through dubbing, closed captions, or producing Spanish-language videos. We should also consider accessibility for caregivers speaking additional languages, while considering the triple HCD goal of maximizing desirability, feasibility, and viability.

Strengths and limitations

To develop a transition readiness mHealth tool, we followed the PRISM framework by considering patient perspectives (Feldstein & Glasgow, 2008) through iterative interviews with end-users and their caregivers. To incorporate organizational perspectives, we partnered with a clinician advisory council. It was beyond the scope of this article to detail the entire PRISM-guided process of designing and implementing this intervention. This article zooms in on the adolescent and caregiver engagement component of this project, but it is a component of a larger program development effort, which will continue to integrate ongoing, multilevel feedback from implementation partners related to the organizational perspective, available infrastructure, and the external environment. As the project progresses, we will continue partnering with our clinician advisory council and enroll clinicians as research participants to evaluate the intervention and guide implementation strategies. The recently designed iterative PRISM webtool could benefit these ongoing efforts (Trinkley et al., 2023).

Study limitations were primarily related to recruitment and representativeness of study participants, which is often a challenge in participatory research (van Schelven et al., 2020). Participants were recruited via clinician referrals. Although we hoped to enroll a heterogeneous sample, it may be that the young people who agreed to participate were unusually interested in healthcare engagement. Although we recruited Latiné adolescents at rates similar to our patient population, we struggled to recruit participants representing the full demographic diversity of CHLA. Of particular concern, we did not successfully recruit any Black/African American youth to this study, which could negatively impact the intervention’s inclusivity. Despite our intention to enroll a more purposive sample, the dynamics involved in clinician invitations and responses to researchers’ calls may have produced a convenience sample. To develop a fuller understanding of the patient experience, future efforts should focus on including racially minoritized youth, those with less transition readiness, or those less motivated to contribute to program development/research. We might be able to achieve that goal by reducing the burden of participation, increasing compensation, better explaining the value of research, or better partnering with colleagues with strong relationships with diverse patients. We did not identify any themes of difference in participant feedback based on subspecialty clinic, age, gender, or race/ethnicity, although this could be related to sample size. Our study is also limited by the lack of back-translation methods.

In addition, while participants expressed interest in gaining condition-specific knowledge and skills, at this stage the project is focused on transition-readiness across CHC. Prior work demonstrates that adolescents and young adults with different health conditions list more common barriers to transition than condition-specific challenges (Gray et al., 2018). Findings from Huang et al. (2014) showed that a generic approach to transition-readiness programs, which targets common skills needed for transition, exhibits efficacy in improving health management and self-efficacy. At this stage, our project’s aim is to identify the most relevant and interesting transition-readiness information for early adolescents across CHC, and incorporating disease-specific interventions would be too resource-intensive, but it is a consideration for future intervention iterations.

The small groups participating in the current study may produce idiosyncratic results that require further validation with larger samples. Given this was an applied project aiming to develop a solution for a specific pediatric hospital, the results of this study may not generalize to other settings. Nonetheless, it is possible that the intervention may be applicable beyond this specific setting because transition readiness skills are relevant to all youth, including those who engage in short-term care for acute conditions, prevention services, or routine primary care appointments. However, more research would be needed to assess whether the intervention designed for the current patient population and organization would translate to broader settings or samples. Including an evidence-based framework like the Behavior Change Wheel (Michie et al., 2011) could enhance the intervention’s generalizability.

Conclusion

This iterative HCD process resulted in progressively more promising prototypes of a social media style transition readiness intervention for early adolescents with CHC. Future directions include producing several more videos guided by the key design principles identified in this study, conceptualized as Prototype 3 in the Ideation phase. We will enroll additional youth, caregivers, and organizational representatives in a qualitative study to elicit their feedback and validate the results generated so far. With ongoing guidance from the advisory councils, we aim to use a type 1 hybrid effectiveness-implementation trial design to evaluate the impact of viewing these videos on adolescent transition readiness skills and develop an implementation plan. Ultimately, we will disseminate the videos within regular care while regularly seeking patient and organizational perspectives consistent with the PRISM framework.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the consultation, support, and assistance we received from the CHLA Patient and Family Education Program, Margeaux Akazawa, MPH, Kate Berman, BS, BA, Anne Nord, RN, Roberta Williams, MD, Jennifer Baird, PhD, MPH, MSW, RN, CPN, and Omkar Kulkarni, MPH throughout this project.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Contributor Information

Kenia Carrera Diaz, Psychology Postdoctoral Fellowship, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, United States.

Joanna Yau, University of Southern California Viterbi School of Engineering, Los Angeles, United States; Department of Psychology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, United States.

Ellen Iverson, Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, United States; Department of Pediatrics, University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine, Los Angeles, United States.

Rachel Cuevas, Center for Healthy Adolescent Transition, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, United States.

Courtney Porter, Center for Healthy Adolescent Transition, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, United States.

Luis Morales, Office of Patient Experience/Patient Family Education, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, United States.

Maurice Tut, Translational Informatics/Information Services Department, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, United States.

Adan Santiago, Center for Healthy Adolescent Transition, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, United States.

Soha Ghavami, Center for Healthy Adolescent Transition, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, United States.

Emily Reich, Psychology Postdoctoral Fellowship, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, United States.

Caitlin S Sayegh, Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, United States; Department of Pediatrics, University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine, Los Angeles, United States.

Author contributions

Kenia Carrera Diaz (Data curation [supporting], Formal analysis [equal], Investigation [equal], Methodology [supporting], Writing—original draft [supporting], Writing—review & editing [lead]), Joanna Yau (Data curation [supporting], Formal analysis [equal], Methodology [supporting], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Ellen Iverson (Conceptualization [equal], Formal analysis [equal], Writing—review & editing [supporting]), Rachel Cuevas (Conceptualization [supporting], Investigation [supporting], Project administration [equal], Writing—review & editing [supporting]), Courtney Porter (Conceptualization [supporting], Project administration [lead], Resources [lead], Writing—review & editing [supporting]), Luis Morales (Data curation [supporting], Writing—review & editing [supporting]), Maurice Tut (Conceptualization [equal], Project administration [supporting], Resources [supporting], Writing—review & editing [supporting]), Adan Santiago (Conceptualization [supporting], Investigation [supporting], Writing—review & editing [supporting]), Soha Ghavami (Conceptualization [supporting], Investigation [supporting], Writing—review & editing [supporting]), Emily Reich (Conceptualization [supporting], Writing—original draft [supporting], Writing—review & editing [supporting]), and Caitlin S. Sayegh (Conceptualization [lead], Formal analysis [lead], Investigation [lead], Methodology [lead], Supervision [lead], Writing—original draft [lead], Writing—review & editing [supporting])

Funding

This work was supported by a donation to our institution from a private family foundation to the Children’s Hospital Los Angeles Center for Healthy Adolescent Transition. The funding source was not involved in the study or manuscript submission. In addition, this work was supported by grants (UL1TR001855 and UL1TR000130) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) of the U.S. National Institutes of Health, awarded to the Southern California Clinical and Translational Science Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This project was completed in partial fulfillment of the requirements of K.C.D.’s participation in the Clinical Child Psychology Postdoctoral Fellowship at the USC University Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities, and in the Leadership Education in Adolescent Health (LEAH) Training Program (T71MC30799).

References

- Akre C., Suris J. C. (2014). From controlling to letting go: What are the psychosocial needs of parents of adolescents with a chronic illness? Health Education Research, 29(5), 764–772. 10.1093/her/cyu040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe J. (2014). Rapid qualitative inquiry: A field guide to team-based assessment. (2nd edn). Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Blower S., Swallow V., Maturana C., Stones S., Phillips R., Dimitri P., Marshman Z., Knapp P., Dean A., Higgins S., Kellar I., Curtis P., Mills N., Martin-Kerry J. (2020). Children and young people’s concerns and needs relating to their use of health technology to self-manage long-term conditions: A scoping review. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 105(11), 1093–1104. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2021). To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 13(2), 201–216. 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. (2020). National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) Data Query. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Ergler C. (2015). Beyond passive participation: From research on to research by children. In R. Evans, L. Holt, & T. Skelton (Eds.), Methodological approaches (pp. 1-19). 10.1007/978-981-4585-89-7_11-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein A. C., Glasgow R. E. (2008). A practical, robust implementation and sustainability model (PRISM) for integrating research findings into practice. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 34(4), 228–243. 10.1016/S1553-7250(08) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham A. K., Wildes J. E., Reddy M., Munson S. A., Barr Taylor C., Mohr D. C. (2019). User-centered design for technology-enabled services for eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 52(10), 1095–1107. 10.1002/eat.23130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray W. N., Schaefer M. R., Resmini-Rawlinson A., Wagoner S. T. (2018). Barriers to transition from pediatric to adult care: A systematic review. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 43(5), 488–502. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsx142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J. S., Terrones L., Tompane T., Dillon L., Pian M., Gottschalk M., Norman G. J., Bartholomew L. K. (2014). Preparing adolescents with chronic disease for transition to adult care: A technology program. Pediatrics, 133(6), e1639–e1646. 10.1542/peds.2013-2830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ideo.org. (2015). The field guide to human-centered design. http://www.designkit.org/resources/1.

- Kelley T. R. (2020). The anatomy of a design brief. Technology and Engineering Teacher, 79(7), 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Korpershoek Y. J. G., Hermsen S., Schoonhoven L., Schuurmans M. J., Trappenburg J. C. A. (2020). User-centered design of a mobile health intervention to enhance exacerbation-related self-management in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Copilot): Mixed methods study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(6), e15449. 10.2196/15449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez K., O’Connor M., King J., Alexander D., Challman M., Lovick D., Goodly N., Bonaduce De Nigris F., Smith A., Fawcett E., Mulligan C., Thompson D., Fordis M. (2017). Building mobile technologies to improve transitions of care in adolescents with congenital heart disease. Iproceedings, 3(1), e36. 10.2196/iproc.8583 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Low J. K., Manias E. (2019). Use of technology-based tools to support adolescents and young adults with chronic disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 7(7), e12042. 10.2196/12042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majeed-Ariss R., Baildam E., Campbell M., Chieng A., Fallon D., Hall A., McDonagh J. E., Stones S. R., Thomson W., Swallow V. (2015). Apps and adolescents: A systematic review of adolescents’ use of mobile phone and tablet apps that support personal management of their chronic or long-term physical conditions. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(12), e287. 10.2196/jmir.5043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R. (2010). Design thinking: Achieving insights via the “knowledge funnel”. Strategy & Leadership, 38(2), 37–41. 10.1108/10878571011029046 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Michie S., van Stralen M. M., West R. (2011). The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science, 6(1), 42. 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior M., McManus M., White P., Davidson L. (2014). Measuring the “Triple Aim” in transition care: A systematic review. Pediatrics, 134(6), e1648–e1661. 10.1542/peds.2014-1704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psihogios A. M., Ahmed A. M., McKelvey E. R., Toto D., Avila I., Hekimian-Brogan E., Steward Z., Schwartz L. A., Barakat L. P. (2022). Social media to promote treatment adherence among adolescents and young adults with chronic health conditions: A topical review and TikTok application. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology, 10(4), 440–451. 10.1037/cpp0000459 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sayegh C. S., Reich E., Cuevas R., Porter C., Tut M., Cramer C., Williams R., Iverson E. (2022). Using human-centered design to support adolescents and young adults with special healthcare needs. Patient Education and Counseling, 105(4), 1052–1053. 10.1016/j.pec.2021.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleath B., Carpenter D. M., Lee C., Loughlin C. E., Etheridge D., Rivera-Duchesne L., Reuland D. S., Batey K., Duchesne C. I., Garcia N., Tudor G. (2016). The development of an educational video to motivate teens with asthma to be more involved during medical visits and to improve medication adherence. Journal of Asthma, 53(7), 714–719. 10.3109/02770903.2015.1135945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinkley K. E., Glasgow R. E., D’Mello S., Fort M. P., Ford B., Rabin B. A. (2023). The iPRISM webtool: An interactive tool to pragmatically guide the iterative use of the practical, robust implementation and sustainability model in public health and clinical settings. Implementation Science Communications, 4(1), 116. 10.1186/s43058-023-00494-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Schelven F., Boeije H., Mariën V., Rademakers J. (2020). Patient and public involvement of young people with a chronic condition in projects in health and social care: A scoping review. Health Expectations, 23(4), 789–801. 10.1111/hex.13069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandekerckhove P., De Mul M., Bramer W. M., De Bont A. A. (2020). Generative participatory design methodology to develop electronic health interventions: Systematic literature review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(4), e13780. 10.2196/13780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vindrola-Padros C., Johnson G. A. (2020). Rapid techniques in qualitative research: A critical review of the literature. Qualitative Health Research, 30(10), 1596–1604. 10.1177/1049732320921835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogels E. A., Gelles-Watnick R., Massarat N. (2022). Teens, social media, and technology 2022. Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- White P. H., Cooley W. C; Transitions Clinical Report Authoring Group, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Physicians. (2018). Supporting the health care transition from adolescence to adulthood in the medical home. Pediatrics, 142(5), e20182587. 10.1542/peds.2018-2587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]