Abstract

A vibrant ecosystem of innovation hinges on undergraduate science programs that inclusively deepen conceptual understanding, develop scientific competencies, and spark wonder and appreciation for science. To create this ecosystem, we need to influence multiple components of the system, including faculty as well as culture (i.e., rules, goals, and beliefs giving rise to them). Here we describe and evaluate a multi-institution community of practice focused on transforming undergraduate biology programs’ organizational practices, behaviors, and beliefs, as well as instilling a sense of agency in community participants. The approach drew on three change theories: Community of Practice, Participatory Organizational Change, and Organizational Justice. Via mixed methods, we found that participation in the community catalyzed the flow of tangible capital (knowledge resources), grew social capital (relationships and identity), and developed human capital (creative problem-solving and facilitative leadership skills; sense of agency). In participants’ home departments, application of knowledge capital was associated with increased implementation of the principles of the Vision and Change report. Departmental change was enhanced when coupled with use of capitals developed through a community of practice centered on creative problem-solving, facilitative leadership, conflict resolution, and organizational justice.

INTRODUCTION

Key national reports (e.g., PCAST, 2010, 2012) spanning all disciplines within science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM), as well as discipline-focused reports, for example, Vision and Change in Undergraduate Biology Education: A Call to Action (V&C; AAAS, 2011), envision STEM education as being inclusive and advancing equity, with students from all backgrounds—racial, ethnic, geographic, socioeconomic, gender—finding success and relevance in their scientific studies. Much research has investigated strategies for more fully reaching the vision of a diverse STEM ecosystem through using inclusive and evidence-based strategies in undergraduate program and course design (White et al., 2021). These strategies include active learning pedagogy (Theobald et al., 2020), course-based undergraduate research experiences (Rodenbusch et al., 2016), emotion regulation activities (Rozek et al., 2019), and social-belonging interventions (Walton et al., 2023). Individual instructors represent one component important for changing teaching and learning, and much effort to promote change is focused at this level (e.g., see Sansom et al., 2023, on factors influencing instructors’ adoption of inclusive and evidence-based strategies).

Another component is the instructors’ department or program. Departments are the level at which undergraduate education programs and decision-making authority regarding content and structure typically reside. The processes used in decision-making and conflict resolution have a critical impact on achieving the sort of systemic change that is needed in higher education to realize the vision noted above. Emergent changes at the organizational level have been argued to have promise for improving STEM education, based on analysis of data from a large-scale study of change within engineering education in the United States (Besterfield-Sacre et al., 2014). Also, focus on change at the departmental level fits with social-psychological ideas of Lewin and Kelman that “it is easier to change a person as part of a group than as an isolated individual” (Baron, 2004, p. 17).

Recognizing the academic department—its ways of thinking and behaving organizationally, in short, its culture (D'Andrade, 1995)—as a point of strong leverage (e.g., Meadows, 1997), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI), National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIH-NIGMS), and NSF launched Partnership for Undergraduate Life Sciences Education (PULSE, https://pulse-community.org/) in 2012. PULSE is working to align the culture of biology programs with data-supported practices recommended in V&C and other reports. Here, we report individual and department-level outcomes from a multi-institution intervention, the Midwest and Great Plains Network (or Community of Practice, MWGP CoP, spanning Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Wisconsin) that sought to catalyze in undergraduate biology programs a shift in organizational practices, beliefs, and behaviors toward those supportive of the vision described in the first paragraph.

Literature supports the efficacy and power of communities of practice in supporting change in higher education (Cox, 2001) and other organizational types (Wenger and Snyder, 2000; for historical review, see Li et al., 2009). Change follows from the knowledge capital cultivated by the communities. Three forms of knowledge capital are relevant to this project: social, human, and tangible. The first consists of social connections and catalyzes social action (Coleman, 1988; Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998; Lesser and Storck, 2001). Social capital has multiple facets, relating to relationships, shared narratives and understandings, trust, mutual obligations, and sense of companionship and identity arising from a shared context or challenge. Social capital also captures the emergent properties that enable a team to be greater than the sum of its constituents and the transformed way of acting or learning through participating in a group. The human form of knowledge capital is reflected in skills, knowledge, and capabilities, as well as the agency, confidence, and sense of calling to use them (Coleman, 1988; Wenger et al., 2011). Tangible capital is exemplified by shared knowledge resources, as well as items that facilitate access to the resources (e.g., PULSE rubrics, assessment instruments).

We additionally drew on Participatory Organizational Change theory, seeing change as growing from “leaderful” practice, dialogue, and deliberation (Raelin, 2012). Leaderful practice is manifested in a community in which all members collectively and concurrently participate in leadership situated not in persons but rather in functions such as setting goals, advancing toward them, and engendering commitment. One path toward leaderful practice is given by facilitative leadership (Parnes, 1985; Moore, 2004; Fryer, 2012), in which the nominal or administrative leader creates the conditions for all members feeling empowered to partake in leadership. Leaderful practice goes hand-in-hand with dialogue and deliberation. In dialogue, conversation aims for understanding the perspectives, insights, and experiences brought to the group by each individual. Deliberation harnesses this understanding and the diversity on which it is based for identifying optimal solutions.

Organizational Justice (Colquitt et al., 2001) also informed the project. The concept includes facets termed distributive, procedural, and interactional justice. Distributive justice reflects perceived fairness of outcomes; it can flow from procedural justice, the perceived fairness of the decision-making process. Interactional justice (Bies and Moag, 1986; Bies, 2015) grows from the dignity accorded to one another within the group as options are explored and decisions made (Hicks and Weisberg, 2004; Hicks, 2011). In the context of change theory, perception of justice heightens participants’ commitment to a change process, while perception of injustice leads to cynicism, apathy, or worse (Bernerth et al., 2007; Oreg and van Dam, 2009). We see fairness and dignity as key qualities of a community of practice and of leadership, dialogue, and deliberation. Thus, the change theory Organizational Justice can be seen as foundational to the first and second change theories.

Our intervention integrated and applied these three change theories in order to catalyze in undergraduate biology programs a shift in organizational practices, beliefs, and behaviors toward ones supportive of ongoing programmatic evaluation and continual enhancement, which will result in the ultimate goal of implementation of practices advocated by V&C and other reports, both published and in the future, emerging from studies on student learning and outcomes. The preconditions or shorter-term goals revolved around development of knowledge capital related to the three change theories.

The MWGP CoP engaged teams of faculty and administrators from institutions of higher education in conferences with two kinds of interleaved sessions: teamwork and activity-based. Informed by the three principles of Participatory Organizational Change theory (leaderful practice, dialogue, deliberation), as well as by the centrality of fairness and dignity in Organizational Justice theory, the teamwork sessions experientially developed skills of creative problem-solving (e.g., Treffinger, 1995; Puccio et al., 2011), facilitative leadership (Parnes, 1985; Moore, 2004; Fryer, 2012), and conflict resolution through integrative (“win-win”) problem-solving (Weitzman and Weitzman, 2014). In groups, creative problem-solving invites full and equitable participation of persons with distinct perspectives. In alternating phases of divergent (idea-producing) and convergent (evaluative) thought, creative problem-solving clarifies the vision and challenge, forges a solution, and plans for implementation. Thus, creative problem-solving scaffolds dialogue and deliberation and gives rise to facilitative leadership, hence leaderful practice. Additionally, during conflict resolution, creative problem-solving leads to integrative, win-win solutions that invite commitment and lessen contention among the involved parties (Carnevale and Pruitt, 1992). Consequently, the skills of creative problem-solving, along with the confidence and sense of agency to use them, reflect the human capital seen by the project as a precondition for the project's long-term goal.

In line with Community of Practice change theory, the activity-based sessions were designed to foster interactions, build community, and spark the flow of ideas and resources among teams. The activity-based sessions thus built knowledge capital, representing a precondition for achieving the project's long-term goal. The key short-term outcome of these activity-based sessions was that participants would find value and sense of belonging in the CoP.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

This mixed methods study had the following two research purposes:

to explore the perceived value and impact of the MWGP CoP in individuals and in their departments—what was beneficial and how so;

and

-

2.

to relate participation in MWGP CoP to progress made by participants’ departments in aligning their undergraduate biology programs with the principles of V&C.

For the first purpose, we inductively analyzed qualitative data from surveys and questionnaires. Separately, external consultants inductively analyzed data from in-depth interviews. We then performed holistic triangulation (Turner et al., 2017) of qualitative and quantitative strands. Commitment to the framework of capitals arose during the writing of this report. On the basis of the three change theories, we envision the CoP's linking individuals around skills of creative problem-solving, facilitative leadership, and a problem-solving approach to conflict resolution and thereby benefiting attempts at organizational change by the departments in which the individuals reside.

For the second research purpose, we convergently triangulated qualitative findings from in-depth interviews and surveys with quantitative data from departmental teams’ self-scoring with the PULSE Rubrics (Brancaccio-Taras et al., 2016). The Rubrics quantify implementation of the recommendations of V&C at the departmental level. Being held to the Rubrics’ yardstick is the departmental culture as shaped by the choices of individual departmental members and by the cognitions underlying these choices. We were sensitive to the possibility that the qualitative data might reveal important shifts of departmental culture—behaviors, cognitions, values—distinct from aspects captured by the Rubrics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Community of Practice Development

To develop the CoP, we sought to provide experiential learning opportunities, build connections among individuals who were interested in change, and share knowledge to foster development of better educational programs. Our efforts were designed to promote repeated and long term exposure and interaction among those interested in improving STEM education. Summer conferences, described in more detail below, were a key organizing element. To encourage creation of the community of practice, summer conference agendas were developed during winter and spring through planning meetings scaffolded by creative problem-solving and involving the Midwest PULSE Fellows and typically 10 to 20 additional participants, initially selected from individuals already known for their interest in STEM education reform and, for conferences subsequent to the first, from attendees at previous conferences. Inclusion of these participants offered a way to tailor conference sessions to the needs of departmental teams, as well as to stay in contact with teams in the intervals between conferences. The planning meetings generally were virtual, supplemented by an in-person, weekend meeting in years prior to the pandemic. In addition, several sub-hub groups were formed by participants geographically near each other to promote information exchange. Representation of previous participating departments was encouraged at each subsequent conference and participants with various specialized knowledge were recruited to facilitate workshops on their specialties at subsequent conferences. After the first, the conferences had a mix of new and returning teams; the mix was intentional, both for longitudinally assessing team progress and for infusing the conferences with peer-to-peer learning and supporting the ongoing interactions among CoP members.

Conference Structure

The core of the CoP comprised the Midwest and Great Plains Summer conferences. These were conceived as 3-day intensive working meetings at which the CoP would be cultivated around the overarching, common goal of improving undergraduate biology programs. Participation in the conferences required departments to send teams of 3–6 faculty and administrators, typically including the department chair, faculty involved in curricular planning, and, in some cases, administrators involved in undergraduate education planning or teaching and learning center staff. The conferences introduced teams to creative problem-solving as a way to identify challenges and opportunities, to generate, refine, and unite behind a common vision collaboratively, and to plan for implementation of the vision, including strategies to build on opportunities and overcome barriers and challenges. To achieve this goal, teamwork was the primary focus, consisting of multiple multi-hour blocks in which teams experientially gained familiarity and confidence with creative problem-solving tools. The teams’ goal was developing a plan for advancing equity and learning within their home department and their planning was scaffolded around a defined planning process and coached by PULSE Fellows familiar with and knowledgeable about this process. The transformation plans developed at the conference were an exercise through which participants gained the skills and knowledge to engage their home departments in similar planning. Interleaved with these sessions were networking activities and tangible capital development sessions. For worksheet and agenda, see Supplemental Material, Sample MWGP Conference Materials. Tangible capital was provided through workshop sessions in which individuals engaged in “active learning” related to common needs and interests such as programmatic and course assessment, learner meta-cognition, and students’ well-being and sense of belonging, with participants recruited to share expertise relevant to such learning. Networking opportunities were provided to build social and human capital, through the sharing of knowledge among participants and generative feedback on the plans developed during the teamwork sessions.

Growth of the MWGP CoP

The MWGP CoP grew to comprise 107 institutional members: 29 community colleges (Carnegie basic classification: Associates); 24 baccalaureate colleges (Bachelors); 31 regional comprehensive institutions (Masters); 21 doctoral/research universities; and two tribal colleges. The members included five Hispanic-Serving Institutions and four Asian American and Native American / Pacific Islander-Serving Institutions. Geographically, the institutions mapped to the U.S. Great Plains and Midwest and are accredited by the Higher Learning Commission.

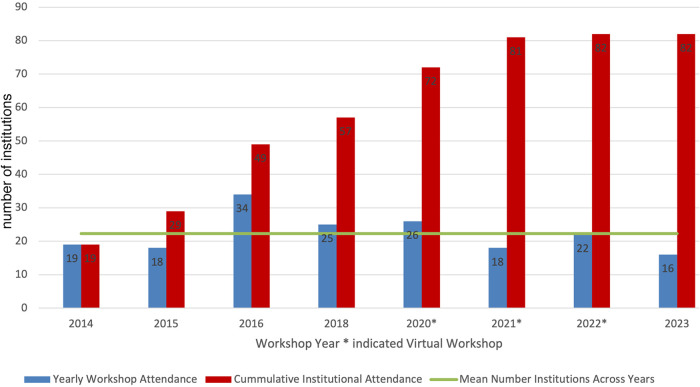

Of the 107 institutional members, 25 teams engaged with the MWGP CoP solely through day-long workshops given at particular locations (e.g., Chicago, Minneapolis) for local institutions. The remaining 82 participated in at least one of eight whole-MWGP CoP summer conferences between 2014 and 2023, shown as a histogram in Figure 1:

FIGURE 1.

Normalized histogram of participation in MWGP CoP conferences by the 82 institutional teams attending at least one.

Growth of the CoP occurred initially by stratified purposeful sampling: while seeking roughly equal representation among Associates, Baccalaureate, Masters, and Doctoral institutions accredited by Higher Learning Commission, we identified and invited institutions with availability and willingness to participate. After its nucleation in 2014, the MWGP CoP continued to grow by a combination of stratified purposeful sampling and word-of-mouth. Nineteen institutional members participated in the MWGP CoP summer conference in year 1 (2014), with 10 new teams participating in year 2 (2015), 20 in year 3 (2016), 8 in year 5 (2018), 15 in year 6 (2020), 9 in year 7 (2021), and 1 in year 8 (2022). The conference in 2023 was offered for only returning teams. Attendance was fairly consistent (Figure 2; blue columns and green line), even across virtual conferences. The growth indicated by red columns reveals that MWGP CoP gained new institutional partners each year while still engaging some who continued to return. The intentional mixing of new with returning was seen as one way to develop capitals, especially the social form.

FIGURE 2.

Growth of institutional members in the MWGP CoP (red columns) and participation in CoP conferences (blue columns; mean given by green line) between 2014 and 2023.

Collection of Data

The study's protocol was reviewed and deemed exempt by the Oberlin College Institutional Review Board. The protocol reflects mainly a postpositivist philosophical perspective informed by realism ontologically and objectivism epistemologically. Moon and Blackman (2014) explain these philosophical elements and their relevance to biological research that reaches into the social sciences, as ours does. Our ontologically realist stance means that we believe a describable reality exists beyond subjects and their mental constructions. Our epistemologically objectivist position signals that in describing this reality we strive to keep our values at bay, neither imposing meaning on the object of study nor constructing its reality. The realist and objectivist positions shape our postpositivist perspective, seeking generalizable knowledge through multiple methods, one counterbalancing the imperfection of another. For example, we gathered qualitative and quantitative data and linked their analyses for the project's two research purposes. In analyses of qualitative data, the priority was to keep the coding and categorizing close to the respondents’ words and their manifest meaning, without interpretation rooted in sociocultural or structural context. Supplemental Table S1 indicates the years in which particular sets of data were collected, as well as the size of the dataset.

The anonymous end-of-conference questionnaire had Likert-like items and open text responses, as did the follow-up survey administered to teams one or more years after conference participation. Questions were informed by published characteristics of CoPs (Wenger and Snyder, 2000; Wenger et al., 2011), faculty networks (Fullan, 1993, 1999; Kezar, 2001, 2009; Seymour et al., 2011), and organizational change within undergraduate engineering programs (The Royal Academy of Engineering, 2012). The queries for open-text responses and the analyses of the responses appear in Supplemental Tables S3, S4, and S5. Likert-like items on the questionnaire and survey appear with tabulated responses in Supplemental Tables S6 and S7.

Two external consultants collaboratively conducted 11 in-depth interviews, each with a single representative of a departmental team that had participated in at least two MWGP CoP conferences between 2014 and 2018. Provided as Supplemental Table S2, the protocol centered on four queries (#5–#8) that focused on attempted changes and were informed by our chosen change theories and intervention. For example, query #6 reads, “To begin progress toward change for [first change], please tell me about ways your department went about visioning – how ideas were elicited and considered, as well as how a particular vision or challenge emerged as the chosen one.”

To quantify implementation of the principles of V&C, reflecting evidence-based practices pertaining to classroom, department, and institution, teams scored their department with the PULSE Snapshot Rubric, comprising 17 items drawn verbatim across the seven categories of the full-length, version 1.0 PULSE Rubrics (Brancaccio-Taras et al., 2016), from integration of core concepts and competencies in the curriculum to organizational infrastructure and climate. Brancaccio-Taras et al. (2016) reported on the validity and reliability of the full-length Rubrics, with their 66 items, in measuring departmental change aligned with recommendations of V&C. The validity and reliability of the Snapshot Rubric are untested. The suite of PULSE Rubrics is available at https://pulse-community.org/resources. Changes in the Rubric scorings between two timepoints, generally the first CoP Conference attended and the 2023 Conference, were determinable for 12 teams. Limiting the number of pairings were factors including 1) evolution of the wording of items in the Rubrics during 2014 and 2015, 2) variation in use of Snapshot or full-length Rubrics prior to 2016, 3) insufficient identifying information on score sheets to permit pairing, and 4) submission of score sheet at only one timepoint.

In terms of institutional representation and redundancy in the data streams, excluding the anonymous end-of-conference questionnaires, 32 institutions are represented in the MWGP follow-up survey responses (5 Associate's, 1 Baccalaureate, 12 Master's, 14 Doctoral), 11 in the interviews (3 Associate's, 5 Master's, 3 Doctoral), and 12 in the paired Rubric scorings (1 Associate's, 7 Master's, and 4 Doctoral institutions). Figure 3 shows as a Venn diagram the extent of institutional overlap among these three major data streams.

FIGURE 3.

Venn diagram showing extent of institutional overlap among the 12 Rubrics scorings (dashed oval), 11 interviews (dotted circle), and 32 follow-up surveys (solid rectangle).

Analysis of Qualitative Data

Textual data from open-ended queries on questionnaires and surveys lent themselves to conventional content analysis (e.g., Hsieh and Shannon, 2005) involving inductive, descriptive coding and then categorization and elucidation of themes (Boyatzis, 1998; Saldaña, 2009). The coding, categorizing, and interpreting kept close to the respondents’ words and their manifest meaning. After the recursive coding and categorizing, we interpreted the inductively determined codes and their categories through the lens of knowledge capital, consistent with the change theories that informed the project.

The development of three forms of knowledge capital, social, human, and tangible (Table 1), was analyzed based on open text and Likert-like responses on the end of conference surveys and follow-up survey and from the interviews. Social capital has many facets that relate to interpersonal interactions and relationships (Coleman, 1988; Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998). Some important facets related to the data collected in this study are: 1) structural, pertaining to linkages among persons; 2) cognitive, stemming from shared narratives and understandings among the linked persons; and 3) relational, reflecting trust, mutual obligations, and sense of companionship and identity arising from a shared context or challenge. Social capital can also subsume narrower types of capital: intellectual, capturing the emergent properties that enable a team to be greater than the sum of its constituents; and learning, reflecting the transformed way of acting or learning through participating in the group. The human form of knowledge capital is reflected in skills, knowledge, and capabilities, as well as the agency, confidence, and sense of calling to use them (Coleman, 1988; Wenger et al., 2011) (e.g., creative problem-solving and facilitative leadership skills). Tangible capital is exemplified by shared knowledge resources, as well as items that facilitate access to the resources (e.g., PULSE rubrics, assessment instruments, V&C).

TABLE 1.

Data streams providing support for development of particular forms of knowledge capital.

| Capital | Examples/definitions/value | Coding categories/themes | End-of-conference questionnaire Likert-like items | End-of-conference questionnaire open-ended questions | Follow-up surveys | Interviews |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social: relations and connections | Structural (linkages among persons) | Networking/CoP | X | X | X | X |

| Cognitive (shared narratives and understandings) | Networking/CoP | X | X | X | ||

| Relational (sense of companionship; kindred spirits; Identity) | Networking/CoP | X | X | X | X | |

| Intellectual (knowledge and knowing capability of the collective) | Teamwork | X | X | |||

| Learning (a community as a valuable way of learning) | Time and space | X | X | |||

| Build consensus, broader engagement and buy-in | X | X | X | |||

| Human: Personal assets | Useful skills, understanding of key concepts, or new perspectives. | Skill development | X | X | X | |

| Self-efficacy, sense of belonging, agency, motivation | Motivation, inspiration | X | X | X | ||

| Tangible | specific pieces of information, documents, tools and procedures | Actionable product | X | X | ||

| Knowledge Resources: Biomaps, rubrics, assessment tools | X | X | ||||

| Information and tools to enable change | X | X |

Tabulated analyses of end-of-conference questionnaires appear as Supplemental Tables S3 (open-ended responses) and S6 (numerical responses to Likert-like questions). Analyses of follow-up surveys appear as Supplemental Tables S4 and S5 (open-ended responses), as well as Supplemental Table S7 (numerical responses to Likert-like questions).

Regarding the external consultants’ in-depth interviews, 11 interviewees reported on a total of 20 change efforts: 14 accomplished by whole departments, 2 by a subset of a department, and 4 derailed. Through iterative, inductive analyses, the evaluators arrived at six coding categories, all pertaining to supports for the change processes: 1) creative problem-solving group processes; 2) creative problem-solving planning processes; 3) creative problem-solving–related strategies for overcoming resistance; 4) networking; 5) V&C; 6) PULSE Rubrics. We correlated the first three categories as development of human capital, the fourth as social capital, and the fifth and sixth as tangible capital. Additionally, the consultants searched within the transcribed interviews for any comments that department representatives volunteered about changes of their own identities or of their departments’ identities. Changes in identity were categorized as examples of social capital (relational and cognitive).

Soundness of Qualitative Approach and Measures for Achieving Trustworthiness

In line with the methodological guidance of Lockwood et al. (2015), we sought congruence in key facets of the qualitative research to ensure its soundness for its intended research purpose. For example, for the first research purpose, our methodology (content analysis) for the qualitative research accommodated our ontologically realist and epistemologically objectivist stances (Dieronitou, 2014); moreover, the methodology aligned with our postpositivist perspective in drawing on multiple methods of collecting qualitative data (anonymous, free written response; confidential, semistructured interviews) and reporting them (e.g., with quantitative measures of prevalence of categories/themes, along with rich description of them).

In addition to congruence of key facets, we sought trustworthiness of findings in multiple ways. We included frequent and infrequent codes and categories in tables and represented participants’ voices by inclusion of illustrative quotes in reporting the analyses. We gathered written qualitative data anonymously and used external consultants to conduct interviews confidentially and to deidentify data before transmission to us. We also relied on triangulation in investigators, methods, and methodologies (Patton, 1999). For example, consistency of coding was achieved among multiple coders, and all of the authors reviewed the findings for consistency of judgments. Also, as elaborated at the end of Materials and Methods, we acknowledge our positionalities and their influence on the project.

Analysis and Soundness of Quantitative Data

Teams reported consensus scores for the rubric criteria, developed through discussion at the first teamwork session of the conference. Central tendency of distributions of scores on Rubrics, questionnaires, and surveys is reported as mean (SD), as well as median and mode for questionnaires and surveys, to permit comparison with published work. This approach is congruent with our ontological and epistemological stances and philosophical perspective. We used nonparametric statistical tests and measures of effect size (Mann–Whitney test and Wilcoxon signed-rank test; probability of superiority). The estimate of probability of superiority can range from 0 to 1 and reflects the tendency of scores from one group to exceed another group's scores. Nonparametric estimators of effect size are discussed by Cliff (1993) and Grissom and Kim (2012). When analyzing change between initial and follow-up scorings for each of the 17 items, averaged across institutions, we were faced with evaluating 17 hypotheses simultaneously, thereby increasing the probability of wrongly rejecting a null hypothesis. To guard against such, for our statistical inferences, we sought to control the false discovery rate, equal to the ratio of false positives to the sum of true positives and false positives. We used the procedures elaborated by Pike (2011), which start with a decision on an acceptable false discovery rate. We chose 0.2, meaning that we would tolerate one wrongly rejected null hypothesis for every five rejections. This tolerance level felt reasonable, given our question, since one false positive among five positives would not compromise determining whether change occurred. Moreover, the positives could be held to the light of inferences from qualitative data.

Use of Capitals in Change Efforts

The interviews yielded six inductively determined coding categories. We correlated these with social, human, and tangible capital and then determined the number of successful and derailed change processes giving evidence of a particular capital at least once in the interviewees’ accounts. To enhance the trustworthiness of this analysis, we triangulated with a different data source and method: with the six coding categories that had been developed inductively by external consultants studying the interviews, we used deductive content analysis (Kyngäs and Kaakinen, 2020) to examine use of capitals reported by respondents to the follow-up survey administered in 2017 and 2023.

Researcher Positionality

The authors’ varied positionalities shape the observations, analyses, and interpretations made within this mixed methods research project—at times expanding discernment or counterbalancing perspectives; at other times constraining and limiting understanding. With respect to positionalities as they bear on the research reported here, four authors are affiliated with doctoral institutions (one private; three public), four with Master's institutions (one public, three private), and one with a baccalaureate college (private), based on the 2021 Carnegie Classification. The nine institutions are located in the U.S. Midwest. Eight authors have earned tenure; one is tenure-track. All save one of the authors have had administrative roles (chair, program director, and/or associate dean) and have been leadership fellows within PULSE for 6 or more years. All authors have been involved in organizational change processes within their department, and most have been involved in facilitating change processes at other institutions, including participation in other communities of practice. Included in the research team are different identities related to race and ethnicity, to gender, and to neurodivergence. We acknowledge that our research team lacks Alaska Natives, Native Americans, Black people, and other multiply marginalized people. This lack narrows the range of insights and perspectives informing our research. The lack also contributes to a systemic denial of voice. Motivating us to work against this systemic denial are the identities that we do bring to this research—identities related to sex, gender, neurodivergence, disability, and ethnicity, among others—as well as the social experiences stemming from these identities. These identities and experiences shape our core belief in the value of diversity and inform our intervention. Rooted in organizational justice, this intervention draws on creative problem-solving, facilitative leadership, and a problem-based approach to conflict resolution as strategies for bringing to the fore and tapping the full range of insights, skills, and backgrounds in diverse teams. Our belief is that through these strategies we might help to foster belonging, dignity, and justice in our discipline and society.

RESULTS AND FINDINGS

Research Purpose 1, to Explore Perceived Value and Impact of the MWGP CoP in Individuals and in Their Departments

The first research purpose was to examine the benefit of the CoP formed via participation in the MWGP CoP. We first examined whether conference participants gained the capitals associated with CoPs. Weaving together quantitative and qualitative strands (Table 1) for deeper understanding, we also sought insights to how MWGP CoP participation helped to catalyze change in home departments and programs related to organizational justice processes and teaching and learning.

Social Capital.

The CoP should foster development of relationships and mutual learning among participants, all interested in improving STEM education. Extracted themes related to development of linkages and shared understanding with other participants, the recognition of kindred spirits, and an appreciation of the knowledge and collaborative learning that emerged from teamwork were all identified. These themes fall into the structural, cognitive and relational facets of social capital. Many respondents in end-of-conference questionnaires and follow-up surveys, as well as in individual interviews, expressed ideas related to these concepts. Workshop participants mentioned specific aspects of social capital in their responses to the end-of-conference questionnaire's open-ended query, “In what specific way has the workshop been meaningful or valuable to you?” (Supplemental Table S3). More than half (54%) of participants referenced interacting with like-minded individuals or institutional teams and relationship development in their responses, for example, illustrated by “The number of regional area connections it fosters is amazing. We have plans to set up a secondary meeting in our local area to continue and extend these connections, without MWGP PULSE this would not have been possible” (structural facet of social capital). Another participant wrote, “It allowed me to meet with like-minded individuals and to see where our own program falls relative to others moving towards V&C”(relational). In the follow-up survey question regarding how participation in the MWGP CoP advanced change efforts at their department or institution (Supplemental Table S5), 15 of 42 respondents referenced social capital development related to structural, cognitive, and relational facets. For example, a 2017 respondent commented, “Being aware of others facing similar challenges and connecting with those people has built a sense of community.” These themes were supported by numerical responses to Likert-like questions on the end-of-conference questionnaire (Supplemental Table S6). For example, respondents were strongly positive in their responses to questions related to networking. On a scale of 1 (negligibly) to 5 (fully), median was 5 (mode: 5; mean: 4.4) for question 6, “To what extent has the workshop afforded you opportunities to make connections with like-minded individuals?” (relational facet of social capital). Median was 5 (mode: 5; mean: 4.6) for question 3, “To what extent has the workshop helped you to feel part of a larger effort to improve undergraduate biology education?” (reputational), and median was 5 (mode: 5; mean: 4.4) for question 5, “To what extent are the concerns of the network relevant to you?” (relational).

One facet of social capital promoted by CoP involves understanding and appreciating the “knowledge and knowing capability of the collective” (Wenger et al., 2011; intellectual capital). Both end-of-conference questionnaires and follow-up surveys (Supplemental Tables S3 and S5) demonstrated the importance to teams of time and space to work together. Of 158 respondents to the open-ended question in the end-of-conference questionnaire (Supplemental Table S3), 14% referenced the fact that the workshops provided protected time and/or space to work productively with their team, away from distractions and other responsibilities. For example, one conference participant mentioned, “Providing space and time (and expectations of results!) to work with my team,” as a way in which the workshop had been valuable to them. In addition, 19% of respondents commented on teamwork collaborative processes and functioning as most valuable (“I especially benefited from the teamwork sessions. It is encouraging to share ideas and passions and even commiserate with colleagues while working on a plan using the creative problem-solving approach…”). In the follow-up survey (Supplemental Table S5), a few respondents (4 of 42 total respondents across both years of the survey) also mentioned time and space at the workshops, for example, “gave us time as a team to reflect on the changes we needed to make (to identify the problems and challenges) and to identify how we could effect that change…” when asked how participation in the MWGP CoP advanced change efforts in their department.

Social capital themes were also apparent in the interviews conducted by the external evaluation team with 11 individuals, each representing a different institutional team that had participated in at least two MWGP CoP summer conferences. This analysis identified 20 attempted changes, with 16 of those accomplished or partially accomplished and four derailed. In 10 out of 16 accomplished and partial changes, structural, cognitive, and relational facets of social capital (networking) were described as assisting those changes. (“Any of the PULSE meetings that we have attended, it seems like there are always people that are interested in partnering … So, I think just having an outlet where we can sit, talk, and make those connections is really important and critical.”) In addition, identity was an important theme, both at the individual and department level (relational, cognitive: “We thought a lot about our own identity… in terms of what is the vision of our own university compared with other institutions….”) This indicates the participants perceived that MWGP-promoted networking fostered their efforts at change, supporting an association between development of social capital and promoting the adoption of V&C principles, reflecting evidence-based practices designed to improve teaching and learning.

Human Capital.

Another important goal of the MWGP CoP summer conferences was to provide participants with skills in creative problem-solving and facilitative leadership. Development of these skills falls into the human capital category. The results of surveys and interviews were somewhat inconsistent regarding the impact of these skills—overall, participants seemed to be less confident in their ability to implement them, but responses to open-ended questions and individual interviews provide strong evidence that these skills are in fact being used to implement departmental changes. Participants’ responses to Likert-like questions regarding their confidence in these skills were the lowest on the end-of-conference questionnaire (Supplemental Table S6: question 9, “To what extent do you feel equipped to implement the basic strategies of creative problem-solving?” median = 4, mode = 4, mean = 3.6; and question #10, “To what extent do you feel equipped to facilitate (e.g., through strategies of creative problem-solving) discussions in your department leading to a shared vision and plan of action?” median = 4, mode = 4, mean = 3.8). Similarly, on the follow-up survey Likert-like items (Supplemental Table S7), some of the questions regarding use of creative problem-solving strategies were among the lower rated items (median, mode, and mean were 2, 2, 2.4 for question 4 and were 3, 4, 2.9 for question 5). However, other survey responses suggested consensus-building and collaborative processes (creating a shared vision, using an “interconnected systems” perspective, consensus-based, collaborative decision-making) were being used in departments (median and mode ≥4, mean 3.4 to 4.3, on questions 1, 2, 3, and 8; Supplemental Table S7), consistent with skills inculcated during the workshops. Support for implementation of facilitative leadership skills and collaborative consensus-building processes also comes from responses to the open-ended question on the follow-up survey (Supplemental Table S5), “Has participation in the PULSE MWGP network … advanced efforts at change in your department/institution? Specifically, how so?.” Thirteen of 42 respondents across both years referenced leadership skills they acquired that led to improved departmental discussions about change efforts, for example, one participant wrote, “[workshop participants became] activators for the change process to move forward in the department.” Similarly, open ended responses to the question “What has been valuable or meaningful to you?” on the end-of-conference questionnaires (Supplemental Table S3) frequently mentioned collaborative skills gained (19% of respondents).

The external consultant interviews further confirm the importance of building human capital through employing facilitative leadership skills and creative problem-solving strategies, in that interviewees mentioned critical group and planning processes that were learned at the MWGP CoP workshops assisted their change efforts. Interviewee comments about 18/20 attempted changes mentioned group processes (creative problem-solving and/or facilitative leadership skills). For example, “We did our own convergent and divergent thinking because the three of us that were there had attended a PULSE conference before and understood how to do that…” One interviewee (from a department in which changes had been derailed) commented, “In those workshops, we had learned a lot about productive group building and productive ways of getting convergence among multiple individuals… it worked. People were engaged, People were contributing…” In addition, in 16/20 attempted changes, interviewees mentioned collaborative planning processes as key assistors, often started at the MWGP conference, and in 15/20 overcoming resistance as important. In these comments, the process of planning during the conference using creative problem-solving and the skills to get buy-in were credited to the learning and experience gained at the MWGP conference. (“We really used that time [at the MWGP conference] to also brainstorm how we can get the department on board with some significant changes.”) Follow-up survey respondents (13/42) also commented on development of facilitative leadership skills and improvements in departmental dynamics.

Another facet of human capital development is reflected in the increased motivation, inspiration, empowerment, and agency reported by participants. Conference attendance motivated or inspired participants to engage in departmental change processes as reflected in the end-of-conference questionnaires. Participants completing the questionnaire responded positively to Likert-like questions (Supplemental Table S6) about feeling inspired by the conference (question #13: 4.3, 5, 4.4 for median, mode, mean) and feeling that the conference furthered their desire to prompt educational improvements (question #15: 5, 5, 4.5 for median, mode, mean). Of 158 respondents, 19% mentioned inspiration and/or motivation in their answers to the open-ended question (Supplemental Table S3) regarding specific ways in which the conference had been valuable or meaningful to them. For example, one conference participant wrote, “For me the most valuable part of this [conference] workshop was the feeling of enthusiasm and inspiration gained from seeing faculty and administrators who are genuinely interested in improving.” Follow-up surveys (Supplemental Table S5) also provided evidence for agency, for example, “…[conference participants] became activators for the change process to move forward in the department” and “It fired me up. I wouldn't have taken any role on campus like I did with assessment and accreditation without PULSE. It was not even on my radar that that was the kind of leadership that our campus needed….”

Tangible Capital.

The MWGP summer conferences included keynote speakers and separate sessions focused on sharing expertise and, in some cases, providing training in evidence-based practices for teaching, learning outcomes assessment, teaching evaluation, etc. In addition, participants were made aware of and used resources such as the PULSE rubrics and the V&C report. The knowledge resources acquired during these workshop components was often cited by conference participants as an important factor in responses to open-ended questions. For example, 39% of respondents to the end-of-conference surveys (Supplemental Table S3) cited aspects of this professional development as valuable or meaningful. Some representative comments are: “Before the workshop I didn't know about or fully understand the concepts of higher order cognition or metacognition. I think these are great principles to incorporate into my future courses,” and “Valuable: Framework for assessment of change (BioCore Guide test); …; guest speakers.” More than half of the respondents to the network follow-up surveys (Supplemental Table S5) highlighted similar professional development at the workshops, for example “Learning about assessment plans, tools, and learning objectives was critical to our success,” and “implementing the PULSE rubrics has informed changes at course/curriculum level.” In addition, numerical answers to one of the Likert-like items in the end-of-conference questionnaire (Supplemental Table S6) support the idea of gains in tangible capital: question #8,”To what extent has the workshop broadened your awareness of the talents, expertise, and support available through the members of the network?” median = 4, mode = 5, mean = 4.3). In the external evaluator interviews with participants in at least two conferences, gaining tangible capital was also an important theme. Descriptions of 13/20 attempted changes mentioned V&C and 6/20 mentioned the PULSE Rubrics.

Research Purpose 2, on Whether Change Occurred

To address whether departments increased alignment with V&C principles, we convergently triangulated three partly overlapping strands of data: 1) departmental teams’ self-scoring with the PULSE Snapshot Rubric (n = 12); 2) in-depth interviews conducted in 2019 by external consultants (n = 11); and 3) written comments on a follow-up survey administered in 2017 and 2023 (n = 32).

Twelve departmental teams scored their programs at two timepoints with the Rubric (paired Rubric scorings). From the initial to the follow-up scorings, the mean change per Rubric item per institution was +0.3 units (SD = 0.4, with P1-tail = 0.018 via Wilcoxon signed-ranks test) on the 5-unit range of each Rubric item. In other words, scores improved as time progressed. The estimate of probability of superiority offers a measure of effect size; it can range from 0 to 1 and reflects the tendency of scores from one group to exceed another group's scores. This estimate for the paired samples was 0.75. This means that 3 out of 4 randomly sampled pre-post scorings on a Rubric item will show a gain, with the follow-up scoring (the post) exceeding the initial scoring (the pre).

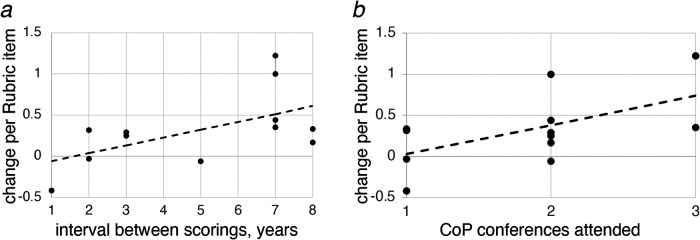

Scatter plots showed that the mean change per Rubric item for each institution correlated with interval between initial and follow-up scorings (Figure 4A), as well as with number of MWGP CoP conferences in which the institutional team participated (Figure 4B; abscissa omits conference at which “follow-up” scoring was done). In both cases, the regression coefficient was 0.6 (P2tail = 0.05); data were insufficient for multiple regression.

FIGURE 4.

(A) Mean change per Rubric item versus interval between initial and follow-up scoring on Rubric by institution. (B) Mean change per Rubric item versus number of MWGP CoP conferences attended from initial scoring up to, but excluding, follow-up scoring on Rubric by institution. In both cases, the regression coefficient was 0.6 (P2tail = 0.05). Data were insufficient for multiple regression (e.g., regression allowing for interaction between the two predictors, years and conferences, yielded F-statistic = 2.0 and P = 0.2).

We also examined the change between initial and follow-up scorings for each of the 17 items, averaged across institutions. Statistically significant gains occurred on five Rubric items, regardless whether raw score (presented in Figure 5, allowing comparison with other published reports of Rubric scores) or normalized change (data not shown; for definition, see Marx and Cummings, 2007) were analyzed: one on course-level assessment, one on program-level assessment, two on pedagogy and higher level learning, and one on infrastructure and climate. These statistical inferences remained valid after limiting the false discovery rate to 0.2 and even reducing the rate to 0.1. We have insufficient data to address why changes occurred with certain items but not others, even in the same category, for example, course-level assessment (items C4 and C5) or program-level assessment (items D6 and D7). That results from analyses of raw score and normalized change were concordant argues against a “ceiling” effect, wherein significant gains are absent in cases in which initial Rubric item scores are close to the upper bound of 4. A reasonable inference is that the areas in which gains were made reflect the prioritized areas on which departments focused energy.

FIGURE 5.

Scorings by Rubric item (i.e., criterion). The scorings were self-reported by departmental teams and reflected the teams’ perceptions of the whole department. Initial (patterned) and follow-up (solid) scorings for each of the 17 items, averaged across institutions. Error bars give +1 SD. Asterisks atop columns in the graph indicate significance, evaluated via Wilcoxon signed-rank test with false discovery rate among the 17 tested hypotheses limited to 0.2. Rubric items are listed subsequently, with significance indicated by bold font. The number of initial and follow-up pairings is indicated by n.

A1: Integration of core concepts into the curriculum, n = 12

B2: Integration of core competencies into the curriculum, n = 12

B3: Extent of core competency integration into the curriculum, n = 12

C4: Linkage of summative assessments to learning outcomes, n = 7, P1tailed = 0.031

C5: Evaluation of time devoted to student-centered activities in courses, n = 12

D6: Assessment of the six V&C competencies at the program level, n = 12, P1tailed = 0.024

D7: Use of data on program effectiveness, n = 7

E8: Opportunities for inquiry, ambiguity, analysis, and interpretation in coursework, n = 12

E9: Student metacognitive development, n = 12, P1tailed = 0.012

E10: Student higher-order cognitive processes, n = 12

E11: Alignment of pedagogical approaches with evidence-based practices, n = 12, P1tailed = 0.020

E12: Awareness of national efforts in undergraduate STEM education reform, n = 7

F13: Intramural and/or extramural mentored research: student participation, n = 12

F14: Supplemental student engagement opportunities, n = 12

G15: Flexibility of teaching spaces, n = 7

G16: Mechanisms for collaborative communication on significant educational challenges, n = 7

G17: Teaching in formal evaluation of faculty, n = 12, P1tailed = 0.024

Offsetting limitations in using Rubrics to gauge change in departmental culture were two strands of qualitative data. Via convergent triangulation, we wanted to examine whether free responses about departmental changes from the interviews and surveys reflected the quantitative changes Rubric scorings illustrated in Figure 5. Changes cited in the interviews echo the statistically significant gains on Rubric items related to assessment, as well as pedagogy and higher-level learning. Inductive coding of the 11 interviews identified a total of 20 changes that had been attempted and discussed in detail during the interview; two interviewees reported on only one change effort, while others reported on two. Four of the 20 change processes derailed: three processes related to assessment and one related to departmental dynamics. The 16 successful change processes fell into multiple categories: 44% (7 of 16) related to teaching, 25% (4/16) to assessment, 25% (4/16) to curriculum, and 6% (1/16) to departmental dynamics. The following quotes illustrate these categories:

teaching: “Just working on the decision [to require biology majors to complete one course-based research experience, CURE], laying out what it would look like … We talk about the [CURE courses] a lot at faculty meetings and we've had a couple of faculty retreats over the past year or so where this course in particular has come up.”

assessment: “Every program in our department … has specific student learning outcomes now, and all those learning outcomes are now measurable.”

curriculum: “Not only had we had [sic] established our new intro bio class, but that really spurred thinking about major curriculum change … We mapped […] our curriculum so that we could make sure everything was covered and see what we lacked […] We actually spent a year with extra meetings […] We had to write up a whole curriculum proposal for the [institution to approve the changes] […] so it was a pretty big change for our department.”

departmental dynamics: “we had to figure out how to … not talk over others… We implemented a stick that you had to pass around before you could talk and I was kind of the moderator and the bailiff, but I didn't really try to engage the conversations a lot unless I needed clarity […]”

That transformation occurred in areas of curriculum, assessment, and pedagogy, as well as departmental dynamics, was also supported by analysis of written responses to the following query on the MWGP follow-up survey: “From the time of your initial MWGP workshop, what specific changes have been planned? Which have been enacted?” Inductive coding of responses (see Supplemental Table S4) revealed four coding categories (themes) of change. The coding category of curricular review and revision was represented in 69% of the 2017 responses and 53% of the 2023 responses. Slightly less represented was the coding category of assessment (50% for 2017 responses; 33% for 2023 responses). Another category was similarly represented (46% for 2017 and 33% for 2023) and was termed by coders, “build consensus, broaden engagement and buy-in,” aligning with the category of departmental dynamics elucidated in coding of interviews. A fourth coding category covered changes of classroom pedagogy and was represented in 27% of the responses from both 2017 and 2023.

Thus, regarding the second research purpose, quantitative results from Rubric scorings and qualitative findings from analyses of interviews and follow-up surveys agreed on MWGP CoP members’ having heightened alignment of their programs with the principles of V&C as measured by Rubrics. Interestingly, the Rubrics do not have items that measure departmental dynamics, although some elements of the climate rubric reflect aspects of social interaction (e.g., Snapshot Rubric Item G16: Mechanisms for collaborative communication on significant educational challenges). The qualitative data provide additional insight into how change occurs that goes beyond the recommendations of V&C, as captured in the Snapshot Rubric.

Change Efforts and Capital Development.

We asked whether development of knowledge capital correlated with change efforts’ success. This could be analyzed directly from the interviews, concerning 16 successful and four derailed change processes. The analysis (Figure 6) revealed strong use of human and social capital in successful change efforts but not derailed ones.

FIGURE 6.

Successful change efforts tap each of the knowledge capitals as revealed in the external evaluator interviews: successful (solid column), derailed (dotted column).

To appraise the generalizability of the association of departmental change with human, social, and tangible capital, as illustrated by Figure 6, we similarly deductively coded responses to the follow-up survey (Supplemental Tables S4 and S5) to its open-ended questions about departmental change catalyzed by participation in the MWGP CoP. The findings corroborated linkage between the three capitals and successful change efforts in the respondents’ departments. Within the pool of 32 institutional responses, the coding category of human capital was reported by 23 institutions (72% of 32), social capital by 20 (63%), and tangible capital by 22 (69%). Multiple capitals were frequently represented in the responses: two kinds of capital were represented in 12 (38% of 32), and three kinds in 12 (38%). Reference to a capital was absent in only 3 (9%). Thus, as in the interviews, participation in the MWGP CoP was seen by respondents as advancing efforts at departmental change, generally by multiple forms of capital.

DISCUSSION

Development of Capital Through CoPs

The first research question explored whether the MWGP CoP effectively developed social, human, and tangible forms of knowledge capital, as would a CoP that stimulates innovation and organizational improvement. While directly informed by CoP change theory, the question also related to the other two change theories, Participatory Organizational Change and Organizational Justice, since these theories are reflected in the knowledge capital that we sought to develop through the CoP. Data from end-of conference questionnaires, follow-up surveys, and interviews all provided evidence that the CoP effectively cultivated knowledge capital. This evidence is important, given our hypothesis that development of knowledge capital is a precondition for reaching the project's long-term goal of increased implementation of the principles of V&C.

Social Capital.

Marshaling evidence from seven organizations, Lesser and Stork (2001) contend that organizational value of CoPs arises from the social capital created by CoPs and the behavioral changes flowing from this form of capital. Both within and beyond teams, growth of structural, cognitive, and relational facets of social capital was revealed in data themes related to development of linkages and shared understanding with other participants, the recognition of kindred spirits, and an appreciation of the knowledge and knowing that emerged from teamwork. These themes speak to the collaboration and collegiality noted by Shadle et al. (2017) as a major perceived driver for adoption of evidence-based instructional practices. Additionally, shared understandings and recognition of kindred spirits speak to identification-based trust (Lewicki and Wiethoff, 2000). In problem-solving, trust is pivotal: it enables groups to benefit in their problem-solving from diversity of perspectives, backgrounds, and approaches, all contributing to “task conflict,” a positive form of conflict (De Dreu and Van de Vliert, 1997), while protecting groups from relationship conflict (Simons and Peterson, 2000). Additionally, the themes from qualitative analyses speak to two facets of psychological well-being that are valuable during change processes: positive relationships and a sense of self-transcendent purpose (i.e., the feeling of being part of something bigger than oneself). Social connections and the sense of belonging afforded by them have been causally linked to motivation and persistence on tasks (Walton et al., 2012), thus offering an explanation, for example, of the importance of social connections in professors’ engagement with teaching professional development (Bouwma-Gearhart, 2012). Social connections fulfill a core human psychological need highlighted in interrelated writings on eudaimonia (Ryff, 1989), belongingness (Baumeister and Leary, 1995), and self-determination (e.g., Ryan and Deci, 2000). Efforts at organizational change can also benefit from participants’ having a sense of self-transcendent purpose, which buffers against professional burnout (Schwartz, 2007; Crea and Francis, 2022). Thus, social capital can play diverse roles in a collaborative change process. Intriguingly, in data from interviews, descriptions of successful change efforts referred to markers of social capital; derailed ones did not.

Tangible Capital.

With its social connections, the MWGP CoP facilitated spread of tangible capital in varied forms related to knowledge resources, for example, instruments for course-level and program-level assessment, meta-cognitive prompts and techniques for scaffolding higher-order learning, curriculum mapping tools, and the PULSE Rubrics. The value of these knowledge resources was cited often by conference participants in the textual data. In providing an avenue for enhancing assessment, these knowledge resources link to one of the top four perceived drivers of reformed teaching in STEM (Shadle et al., 2017) and to one of three key elements discerned in a study of successful department-level change in biology departments (Peteroy-Kelly et al., 2019). Yet, the analysis of interviews about derailed change efforts suggests that tangible capital was insufficient to drive successful change in the absence of strong use of social and human capital (Figure 6). A connection can be drawn from this interpretation and an international study of reform in undergraduate engineering programs (The Royal Academy of Engineering, 2012). The study found that published pedagogical evidence generally was not a driver of successful change.

Human Capital.

The value of knowledge resources depends on knowing how to use them and having the confidence to do so. This “know how” reflects human capital, as do key skills developed in the MWGP CoP: skills of creative problem-solving, facilitative leadership, and a problem-solving approach to conflict resolution. In our study, the use of human capital, like social capital, distinguished successful change efforts from those that derailed (see Figure 6). On end-of-conference questionnaires, participants gave middling scores on their confidence to use these problem-solving and leadership skills; yet, themes from multiple strands of qualitative data gave evidence for participants’ using these skills in home departments to work toward a shared vision and to unite behind a path toward it. Development of these skills in the CoP linked the first and second change theories (CoP; Participatory Organizational Change) to Organizational Justice change theory. The human capital developed in the MWGP CoP relates directly to the notion of organizational justice (Colquitt et al., 2001) and hence workplace well-being (Soren and Ryff, 2023). In giving voice to all participants and leveling status among them, the strategies of creative problem-solving, facilitative leadership, and a problem-solving approach to conflict resolution engender a sense of fairness in a group's procedures (procedural justice) informed by equity theory (Thibaut and Walker, 1978; Greenberg, 1987). From procedural justice grows commitment, cooperative behavior, and trust (Konovsky et al., 1987; Folger and Konovsky, 1989; Korsgaard et al., 1995). Trust has particular significance to groups with diversity, as previously noted in the section on social capital: trust enables groups to harness differences of ideas and perspectives—task conflict—for improved problem-solving and to prevent this diversity from fueling relationship conflict (Zand, 1972; De Dreu and Van de Vliert, 1997; Simons and Peterson, 2000). The importance of procedural justice and other facets of organizational justice (Colquitt et al., 2001) grows as groups become more diverse (Mayer et al., 1995).

Evidence for Change in Departments

CoP change theory envisions development of capital as an early cycle of value creation, to be followed by another cycle in which the capital is put to use. The project's second research question addressed this later cycle of value creation by asking whether participation in the MWGP CoP associates with the perception of departmental adoption of the principles of V&C. As revealed in Rubric scores, CoP participants did discern increased alignment with the principles, as well as changes in departmental interactions and decision-making processes predicted by Participatory Organizational Change and Organizational Justice theories.

Comparison of initial and follow-up Rubric scorings of departments by CoP participants (Figure 5) revealed a cultural shift in departments, as reflected in statistically significant gains related to course-level and program-level assessment (Rubric items C4 and D6), higher-level learning (Rubric items E9 and E11), and teaching evaluation (Rubric item G17). This shift was corroborated in analyses of network follow-up surveys and interviews. Although aligning with realism ontologically, objectivism epistemologically, and postpositivism philosophically, the project was not designed to test causality directly. While no single strand of data thus could demonstrate causality, the convergence among three strands of data points to strong association between participation in the MWGP CoP and adoption of V&C principles, reflecting inclusive, evidence-based practices. Bradford Hill (1965) set forth criteria to consider before concluding that an association permits interpretation of causation. One criterion is strength of association, as provided by Figure 6, based on in-depth interviews. Related to another criterion, temporality, both follow-up surveys and interviews probed the changes specifically ensuing participation in the CoP. A third criterion is evidence of a response dependent on dosage, such as suggested by Figure 4B, showing greater change of Rubric scorings as the number of CoP conferences in which a team participates increases. Plausibility and coherence are two additional criteria met in this study, since informed by change theories. Relatedly, another criterion is consistency with other studies, for example in our case, stories of value creation by CoPs (Wenger and Snyder, 2000), as well as data from a randomized, controlled study of CoPs in the context of adoption of evidence-based practices in healthcare (Barwick et al., 2009).

The areas in which gains were made reflect the prioritized areas on which departments focused energy. Attention to assessment and curriculum within our sampled departments parallels effort to these same areas by teams that participated in the Northwest Regional PULSE Network, with its workshops on harnessing systems thinking to drive change (Stavrianeas et al., 2022). Assessment is an important area on which to focus. A validation study with the PULSE Rubrics found scores on assessment items to rank among the lowest (Brancaccio-Taras et al., 2016); yet, a key ingredient for successful change within undergraduate biology programs comprises organizational emphasis on assessment and use of the data (Peteroy-Kelly et al., 2019). A similar finding about the pivotal role of assessment was found in an international study of change in undergraduate engineering programs (The Royal Academy of Engineering, 2012).

Representatives of departments that sent teams to the conferences described additional ways not captured by the Rubrics in which change was seen. In particular, the qualitative analyses of follow-up surveys and interviews noted improved departmental dynamics. This improvement speaks to skills developed within the MWGP CoP—creative problem-solving, facilitative leadership, a problem-solving approach to conflict resolution—in support of principles of Participatory Organizational Change and Organizational Justice change theories.

Reflection on the Project's Chosen Change Theories

A worthwhile question asks what was gained by merging the three change theories. Participatory Organizational Change theory prompted the focus on skills of creative problem-solving, facilitative leadership, and a problem-solving approach to conflict resolution. The focus clarified how to achieve the leaderful practice, dialogue, and deliberation envisaged in Participatory Organizational Change theory, as well as the forms of justice envisioned by Organizational Justice change theory. The focus also gave substance to the CoP and as such provided the CoP's first cycle of value creation (Wenger et al., 2011). Yet, however important the skills of creative problem-solving, facilitative leadership, and a problem-solving approach to conflict resolution were, the data also revealed the importance of social connection and interaction—the social capital accruing in a CoP. Wenger et al. (2011) caution against underestimating social capital, and Lesser and Storck (2001) highlight the pivotal role of trust, mutual obligation, and shared understanding in enabling CoPs to create organizational value. Consequently, we see dignity and interactional justice more broadly as key components that keep CoPs and the skills of creative problem-solving, facilitative leadership, and a problem-solving approach to conflict resolution from being empty shells. It is through dignity that a cognitive understanding of others’ perspectives becomes an emotional understanding, one that recognizes the human worth of each person and that engenders a sense of true belonging (Hicks, 2011). In this regard, our findings and interpretations echo the framework of Belonging, Dignity, and Justice that is being advanced as an alternative to Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (Davis, 2021).

Limitations and Opportunities for Future Study

To quantitatively measure change in teaching and learning practices, we used the PULSE Snapshot Rubric (v1.0), with only 17 items out of 66 on the full PULSE Rubrics (v1.0). This tool was designed to help departments/teams reflect and quickly come to consensus on areas in which they felt their departments needed to make progress. These areas then became the focus of their action planning. Obtaining consensus scores on the full Rubrics requires extensive discussion and time investment that is impractical in this setting. Because of the limited nature of the information provided by Snapshot Rubrics in each major rubric category, it is not surprising some scores did not change, even if the department might have made changes in that area.

As noted throughout, the Rubric scores used to evaluate changes in teaching and learning in departments were self-evaluations by team members, which included department chairs and faculty engaged in curricular planning, rather than evaluations by external evaluators. Several lines of evidence support the idea that the self-reported, collaboratively generated Rubric scorings are accurate. First, qualitative data from interviews and follow-up surveys contained direct statements from department members about what had changed and how participation in MWGP CoP had facilitated those changes. In those statements, some cited changes reflected categories that showed significant change based on rubric scores. Second, in the PULSE Recognition program, departments generate consensus scores on the full PULSE Rubrics. Evaluators that visit those departments find those scores to be highly accurate. This concordance suggests that scores generated by consensus of a group of knowledgeable faculty will tend to accurately reflect the department's state. Third, the two scorings for our project (initial and follow-up, 2 or more years later) were done independently, usually by teams who differed in overall composition. It seems unlikely that deliberate rescoring at a higher level would be possible given the lack of review of previous scores and new team composition. Finally, in discussions at the conference, participants openly shared information about their departments, both strengths and weaknesses. They sought advice and feedback from others in their efforts to improve teaching and learning. There is no incentive to “cheat” by misrepresenting their department's state.

Over the course of this project, our understanding of the pivotal role of departmental dynamics in change processes—and as a valuable focus for a change process itself—has increased. Our data support that these social aspects are important to participants and necessary for change. Organizationally just, positive interpersonal behaviors do not appear explicitly in our quantitative measure of change, the PULSE Rubrics. Our qualitative data filled the gap. In a future study we would incorporate quantitative, valid, reliable measures of team function and perceptions of distributive and procedural justice.

Our approach left unstudied whether retrenchment occurred or whether participation in the MWGP CoP forestalled retrenchment. Retrenchment or discontinuation of curricular reforms was reported to be common in undergraduate engineering reform efforts, and often the loss of ground occurred by slow drift (The Royal Academy of Engineering, 2012), over a timeframe beyond our study. Also unstudied was whether the changes documented in our study reflected solely single-loop learning, wherein a problem is fixed, or additionally revealed double-loop learning, wherein mental models and assumptions underlying the problem are questioned and challenged (Argyris, 1977). Based on the qualitative analyses, we speculate that double-loop learning is being fostered by the three forms of capital cultivated in the MWGP CoP, particularly human and social capitals reflected in improved interpersonal dynamics and forthright departmental self-reflection. A future study could profitably examine the kind of learning taking place in departments, as well as whether positive change endures. Also deserving study in future are structures and factors beyond the department that constrain its agency and bear on opportunities for action and reform. Our methods were not designed to capture information about structures and factors such as administrative reorganization, shifting institutional requirements, and local and state political influences on the department.

Conclusions and Implications

How do we advance departments’ implementation of inclusive and evidence-based practices in support of deepening students’ conceptual understanding, developing scientific competencies, sparking wonder and appreciation for science, and meeting the nation's need for a scientifically literate populace and technically skilled workforce? Our study offers one answer, namely, by developing through a CoP three forms of knowledge capital: 1) human, focusing on skills of creative problem-solving, facilitative leadership, and a problem-solving approach to conflict resolution, as well as the confidence and sense of agency to use these skills; 2) social, drawing on connections, relationships, and shared understandings; and 3) tangible, involving sharing of knowledge resources for assessment and benchmarking. Development of these capitals promotes the leaderful practice, dialogue, and deliberation envisaged in Participatory Organizational Change theory, as well as the forms of justice envisioned by Organizational Justice change theory. They do so by promoting organizational practices, behaviors, and beliefs that honor the dignity of each member, thereby inclusively empowering members to contribute perspectives, to share leadership, and to grow ideas collaboratively. In addition to outlining how to develop these knowledge capitals, our study shows the importance and centrality in a change process of their development, especially of human and social forms. Two quotes from the 2017 follow-up survey come to fore in capturing the leverage afforded by the CoP:

We started with an idea and no clue how to start. The network and workshop helped us take the first step and then guided us along the way. Learning about assessment plans, tools, and learning objectives was critical to our success. (response 17-18)

PULSE meetings have been instrumental in providing education and sharing of ideas of how to create the dialog among faculty and administrators. It has been an effective way to create leaders in the department. I was surprised that I became a leader in our department. It has been rewarding. (response 17-18)

Development of these capitals helps unlock the full human potential of departmental members, faculty proximally and students ultimately, thereby enhancing human flourishing and well-being (Soren and Ryff, 2023). These findings underscore the substantial positive leverage that a CoP centered on organizational justice, fostered by skills in creative problem-solving and facilitative leadership, can bring to departmental change.