Abstract

The retina, a crucial neural tissue, is responsible for transforming light signals into visual information, a process that necessitates a significant amount of energy. Mitochondria, the primary powerhouses of the cell, play an integral role in retinal physiology by fulfilling the high-energy requirements of photoreceptors and secondary neurons through oxidative phosphorylation. In a healthy state, mitochondria ensure proper visual function by facilitating efficient conversion and transduction of visual signals. However, in retinal degenerative diseases, mitochondrial dysfunction significantly contributes to disease progression, involving a decline in membrane potential, the occurrence of DNA mutations, increased oxidative stress, and imbalances in quality-control mechanisms. These abnormalities lead to an inadequate energy supply, the exacerbation of oxidative damage, and the activation of cell death pathways, ultimately resulting in neuronal injury and dysfunction in the retina. Mitochondrial transplantation has emerged as a promising strategy for addressing these challenges. This procedure aims to restore metabolic activity and function in compromised cells through the introduction of healthy mitochondria, thereby enhancing the cellular energy production capacity and offering new strategies for the treatment of retinal degenerative diseases. Although mitochondrial transplantation presents operational and safety challenges that require further investigation, it has demonstrated potential for reviving the vitality of retinal neurons. This review offers a comprehensive examination of the principles and techniques underlying mitochondrial transplantation and its prospects for application in retinal degenerative diseases, while also delving into the associated technical and safety challenges, thereby providing references and insights for future research and treatment.

Keywords: age-related macular degeneration, Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy, mitochondrial transfer, mitochondrial transplantation, retinal degenerative diseases

Introduction

The retina is a crucial photosensitive tissue within the eye, responsible for receiving light signals and converting them into neural signals, which are then transmitted to the brain for visual recognition. Retinal cells, especially retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) and photoreceptors, consume a significant amount of energy during the process of light signal conversion. Accordingly, a substantial number of functioning mitochondria are required to provide the energy necessary for retinal activity (Wong-Riley, 2010). The metabolic energy consumption of the normal retina primarily depends on mitochondria. Known as the “energy factory” of the cell, mitochondria are responsible for the oxidation of nutrients, generating energy molecules, such as ATP, to meet the high energy requirements of the retina (Barron et al., 2004). Within the retina, mitochondria are mainly distributed in photoreceptor cells (rods and cones) and secondary neurons (horizontal, bipolar, and RGCs). Photoreceptor cells are the cells that directly respond to light signals and require a significant amount of energy to convert these light signals into electrical ones. Secondary neuronal cells are responsible for processing and transmitting the visual information received from photoreceptor cells to higher visual canters. Given that this information processing involves extensive neurotransmitter release and signal amplification, secondary neurons also have high metabolic activity, which requires a large amount of energy to sustain (Kisilevsky et al., 2020). Mitochondria generate the energy molecules essential for retinal function through oxidative phosphorylation, whereby electrons are transferred along protein complexes, ultimately resulting in ATP production (Chrysostomou et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2019). Retinal mitochondria are also involved in other important metabolic processes, such as fatty acid oxidation and amino acid metabolism.

Mitochondrial abnormalities play a significant role in the pathology of retinal degenerative diseases, profoundly affecting disease development and progression. Mitochondrial abnormalities manifest in several forms, including a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential, the accumulation of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations, increased oxidative stress, and dysregulation of mitochondrial quality control mechanisms (Subramaniam et al., 2020). For instance, the reduction in mitochondrial membrane potential observed in retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells in patients with age-related macular degeneration (AMD), which directly affects the normal function of these cells, is a consequence of impaired energy metabolism (Blasiak et al., 2017; Lakkaraju et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2021b). Because RPE cells play a crucial role in maintaining the health of photoreceptor cells, their dysfunction leads to the degeneration of photoreceptor cells in AMD (Strauss, 2005). Moreover, specific point mutations in mtDNA are closely associated with hereditary retinal diseases, such as Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON), in which the function of the respiratory chain is impaired, leading to disorders in energy metabolism, damage to RGCs, and, ultimately, vision impairment (Wong et al., 2017). Additionally, mitochondrial dysfunction results in increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), thereby exacerbating oxidative stress (You et al., 2024). ROS can damage lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids in retinal neurons, and the oxidative damage is particularly dangerous in the high-oxygen-demanding environment of the retina, potentially leading to the destruction of cellular structure and function (Kaarniranta et al., 2020; Hosoya et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2022). Furthermore, imbalances in the mitochondrial quality control system, such as defects in fusion, fission, and autophagy processes, can result in the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria within cells, leading to elevated production of harmful metabolic products and ROS, which further exacerbates the disease state (Angelova and Abramov, 2018). Mitochondrial dysfunction is a crucial factor in retinal degenerative diseases, as it not only reduces energy supply but also causes oxidative damage and activates cell death pathways, which, together, accelerate disease progression (Viscomi and Zeviani, 2023; Qu et al., 2024). Consequently, dysfunctional mitochondria represent potential therapeutic targets for these diseases.

Mitochondrial transplantation is a revolutionary biomedical procedure aimed at restoring the normal function and vitality of damaged or dysfunctional cells through the introduction of healthy mitochondria (McCully et al., 2022). This process involves delicate micromanipulation and plasma membrane fusion techniques, enabling the restoration of mitochondrial function through the fusion of healthy mitochondria with target cells (Cloer et al., 2023). Mitochondria are responsible for producing most of the energy required by the cell; they are “energy providers,” participating in the regulation of various signaling pathways and playing a vital role in maintaining cellular life. When cells are old or damaged, mitochondrial function is often the first cellular process to be affected. Therefore, supplementing these cells with healthy mitochondria can enhance cellular energy metabolism and help cells regain vitality (McCully et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2023a). In 2022, Jacoby et al. enriched CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells of children with single large-scale mtDNA deficiency syndrome with exogenous mitochondria from healthy mothers and injected the cells into the patients. After 6 to 12 months, the mtDNA content of peripheral blood cells increased in all the patients, and peripheral blood heterogeneity decreased in 4 out of 6 patients. This study marked an important milestone in translating the potential of mitochondrial transplantation into clinical practice. Mitochondrial transplantation can also enhance antioxidant capabilities, thus improving cellular defenses against oxidative damage. The introduction of healthy mitochondria can increase the concentration of antioxidants within cells, which effectively neutralize excessive ROS and free radicals, thus reducing their damaging effect on cells (Ma et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2021; Aharoni-Simon et al., 2022). Through this mechanism, mitochondrial transplantation helps maintain the health of retinal cells, slows down retinal degeneration caused by oxidative stress, and protects cells from oxidative damage, thus potentially slowing or preventing the progression of retinal degenerative diseases. Liu et al. (2023b) found that mitochondrial transplantation promoted apoptosis and inhibited cell proliferation in a cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) cell line. After transplantation, the activities of superoxide dismutase, glutathione, and catalase were significantly increased, PTEN expression was activated, and the levels of p-PI3K and p-AKT were reduced. These findings highlight the anti-CCA potential of mitochondrial transplantation, involving the regulation of cellular oxidative stress through the PTEN/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Mitochondrial transplantation also significantly influences cell survival and apoptosis signaling pathways. Through modulation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, mitochondrial transplantation can promote cell survival and exert anti-apoptotic effects, allowing cells to more effectively resist apoptosis triggered by oxidative stress and energy deficiency. Mitochondrial transplantation has broad application prospects for the treatment of retinal degenerative diseases. This procedure may restore cellular energy metabolism and delay the aging of retinal neurons (Kuang et al., 2023). It may also reverse the progression of certain retinal degenerative diseases and offer new possibilities for their treatment. However, the implementation of this therapeutic strategy faces multiple challenges (Figures 1 and 2).

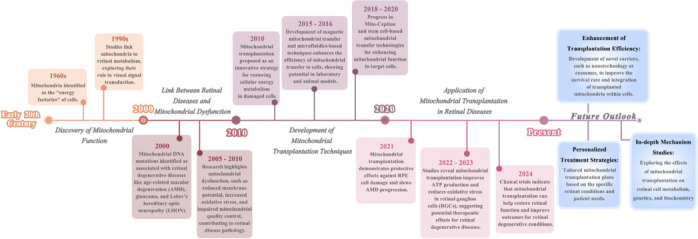

Figure 1.

The timeline of the development of mitochondrial transplantation as a treatment for retinal degenerative diseases.

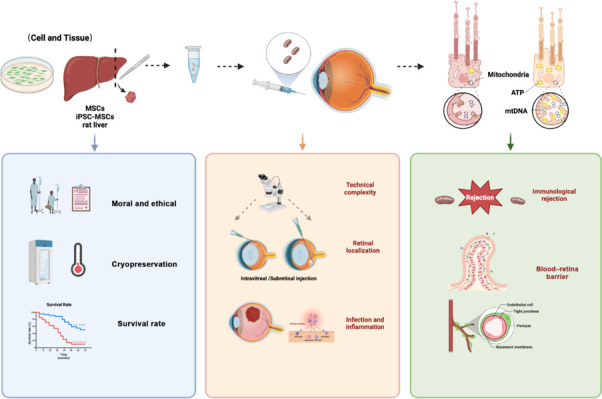

Figure 2.

The current status of mitochondrial transplantation for the treatment of retinal degenerative diseases.

This article summarizes the research status from several aspects, including natural pathways of mitochondrial transfer, artificial mitochondrial transplantation pathways, and the role of mitochondrial transplantation in the treatment of retinal degenerative diseases. Finally, the challenges and limitations faced by mitochondrial transplantation as a treatment method were summarized. Create with BioRender.com.

The aim of this review was to explore the possibilities of utilizing mitochondrial transplantation technology to treat retinal degenerative diseases as well as the associated challenges. Through continued research and technological progress, mitochondrial transplantation has transitioned from theory to practice, demonstrating potential in the treatment of a variety of diseases. In particular, this technique holds promise as a novel therapeutic option in the field of retinal degenerative diseases. In this review, we discuss in detail the principles and methods relating to mitochondrial transplantation, as well as its application prospects in retinal degenerative diseases. We also address the challenges faced by this technology, including technical difficulties and safety issues. Through this detailed analysis, we sought to provide a comprehensive perspective on the application of mitochondrial transplantation in the treatment of retinal degenerative diseases, offering references and insights for future research.

Retrieval Strategy

An online search was conducted using the PubMed database to retrieve articles published up to June 30, 2024. The following word combinations (MeSH terms) were used to maximize the specificity and sensitivity of the search: “retinal degenerative diseases,” “mitochondrial transplantation,” “mitochondrial transfer,” “age-related macular degeneration (AMD),” and “Leber’s hereditary optical neuropathy (LHON).” Titles and abstracts were further screened, and only studies exploring the relationship between mitochondrial transplantation and retinal degenerative diseases were included to investigate the current status of mitochondrial transplantation technology in the treatment of retinal degenerative diseases. The search was not restricted by language or learning type. Articles that involved mitochondrial transplantation but were not associated with retinal degenerative diseases were excluded.

Mitochondrial Abnormalities in Retinal Degenerative Diseases

Retinal degenerative diseases are characterized by the gradual loss of function and death of retinal neurons. Clinically, these diseases typically manifest as a progressive decline in vision, ultimately leading to blindness (Zhong and Sun, 2022). AMD is the most common form of retinal degenerative disease (Lin et al., 2015). Other types include genetically inherited retinal neuropathies such as LHON, which is triggered by mutations in mtDNA and follows a maternal inheritance pattern. Retinitis pigmentosa (RP), although primarily caused by nuclear gene mutations, can also result from mtDNA mutations (Pitchon et al., 2015; Figure 3).

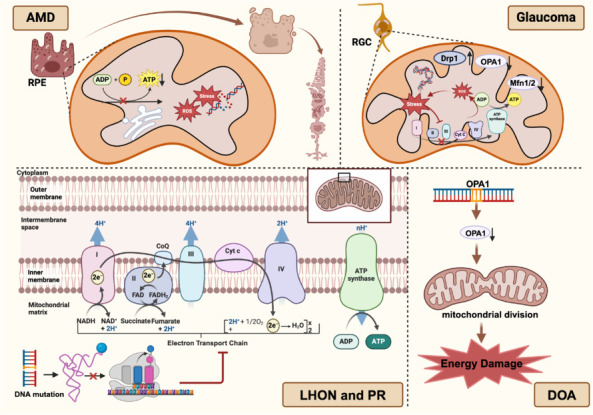

Figure 3.

Mitochondrial abnormalities in retinal degenerative diseases.

In age-related macular degeneration (AMD), mitochondria undergo abnormal changes due to oxidative stress and DNA damage, leading to reduced ATP synthesis and increased free radical production. In glaucoma, retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) are affected by oxidative stress, resulting in excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) production by mitochondria, causing damage to cellular DNA, proteins, and lipids. There is an imbalance in mitochondrial dynamics in glaucoma, characterized by the upregulation of the expression of the fission protein Drp1 and the downregulation of that of the fusion proteins Mfn1/2 and OPA1, causing mitochondrial network fragmentation and further weakening mitochondrial energy synthesis capabilities. In Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) and pigmentary retinopathy (PR), pathogenesis is closely related to specific point mutations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), typically located in genes encoding subunits of complex I (NADH dehydrogenase) of the electron transport chain. Meanwhile, mutations in the OPA1 gene are a key pathogenic feature of dominant optic atrophy (DOA). Created with BioRender.com.

Age-related macular degeneration

AMD is a retinal degenerative disease closely associated with mitochondrial dysfunction (Huang et al., 2024c; Khademi et al., 2024). Mitochondrial damage directly impacts the health of retinal cells, and can thus exacerbate the progression of AMD. It is estimated that nearly 200 million people worldwide are affected by AMD, and this number is projected to significantly increase over the coming decades due to the aging of the global population (Samanta et al., 2021; Amini et al., 2023). Although the pathogenesis of AMD is not yet fully understood, numerous studies have indicated that abnormalities in retinal neurons play an important role in its development (Kaarniranta et al., 2020). Mitochondria, which are responsible for energy metabolism and oxidative phosphorylation reactions, undergo abnormal changes with increasing age owing to factors such as oxidative stress and DNA damage, which affect their function and structure (Szeto, 2006). These changes can increase mitochondrial membrane permeability, reduce ATP synthesis, and promote free radical production, ultimately leading to apoptosis and retinal damage (Mandelker, 2008). In RPE cells of patients with AMD, the number of mitochondria is significantly reduced, and the mitochondria exhibit abnormal morphology, characterized by the expansion of the endoplasmic reticulum and the loss of cristae (Fisher and Ferrington, 2008). Mitochondrial function is also affected in RPE cells, manifesting as a decrease in ATP synthesis capacity and a reduction in respiratory chain enzyme activity (Kaarniranta et al., 2020). A reduction in the number and function of mitochondria can result in energy metabolism disorders in RPE cells, which, in turn, lead to cell death (Fisher and Ferrington, 2008). Moreover, an increase in free radical production in the mitochondrial membrane can result in oxidative stress and DNA damage, thereby accelerating the aging and degeneration of RPE cells (Plafker et al., 2012). Functional damage to RPE cells can weaken or eliminate the support they provide to photoreceptor cells. This leads to the accumulation of metabolic waste, insufficient oxygen supply, and decreased antioxidant capacity in photoreceptor cells, causing their degeneration and death (Lakkaraju et al., 2020).

Glaucoma

Glaucoma is an eye disease characterized by damage to the optic nerve and visual field loss and is closely associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. Mitochondrial damage can lead to insufficient energy supply to RGCs, thereby exacerbating optic nerve damage and disease progression (Osborne et al., 2016). Recent research has indicated that oxidative stress-related damage is significantly enhanced in RGCs of patients with glaucoma, primarily due to the destructive effect of excessive mitochondria-derived ROS on cellular DNA, proteins, and lipids (Wang et al., 2014). Oxidative stress not only damages mtDNA, compromising the normal function of the electron transport chain but can also lead to the production of more ROS, creating a vicious cycle (Wei et al., 1998). Moreover, an imbalance in mitochondrial dynamics, manifested by the upregulation of the fission protein Drp1 and the downregulation of the fusion proteins Mfn1/2 and OPA1, results in the fragmentation of the mitochondrial network, further impairing its potential for energy synthesis (Zhao et al., 2010; Bertholet et al., 2016).

Genetic perspectives have also offered crucial insights into the pathogenesis of glaucoma. Genome-wide association studies and other related investigations have identified multiple genetic loci associated with glaucoma risk, including those involving noteworthy mitochondrial function variants (Lascaratos et al., 2012; Bernstein et al., 2019; Aboobakar et al., 2023). These loci may be involved in mitochondrial biogenesis, quality control, and metabolic processes, thereby influencing glaucoma development. For instance, the MFN2, PDE6H, and TMEM136 genes have been linked to an increased risk of glaucoma (Nivison et al., 2017; Zenkel et al., 2017). RGCs from patients with glaucoma can exhibit mitochondrial calcium overload, a condition that disrupts mitochondrial energy metabolism and promotes apoptosis (Marshall et al., 2015). Additionally, abnormalities in mitochondrial energy metabolism are frequently detected in glaucoma, as evidenced by decreased ATP levels in RGCs of affected individuals, implying that insufficient energy supply may contribute to cellular dysfunction and death (Eells, 2019). These observations indicate that mitochondrial abnormalities play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of glaucoma.

Leber hereditary optic neuropathy

LHON is a hereditary disease directly linked to mitochondrial DNA mutations. Patients with this condition exhibit severely impaired mitochondrial function, leading to optic nerve cell damage and loss of vision (Abu-Amero, 2011). The pathogenesis of the disease is closely associated with specific point mutations in mtDNA (Sundaramurthy et al., 2021a), particularly within genes encoding subunits of complex I of the electron transport chain (NADH dehydrogenase), such as ND1, ND4, and ND6 (Majander et al., 1991; Chinnery et al., 2001; Kumar et al., 2012; Rezvani et al., 2013). The most commonly detected mutation in LHON, m.11778G>A in the ND4 gene, accounts for approximately 90% of all LHON cases. This mutation results in an amino acid change from glycine to arginine at position 165, which impairs the function of complex I (Ghelli et al., 1997). The second most frequently detected mutation, m.3460G>A (amino acid position 1140) (Sundaramurthy et al., 2021b), is also located in the ND4 gene and affects the same complex. Besides these two primary mutations, a series of rarer LHON-related mutations, including m.14484T>C, m.14502T>C, m.14502G>A, m.13708G>A, and m.13708T>C, often disrupt tRNA genes (tRNA-Lys, tRNA-Glu, tRNA-Ile, and tRNA-Asn) and impact mitochondrial protein synthesis (Graeber and Müller, 1998; Jiang et al., 2016; Ding et al., 2021). These variants affect the mitochondrial transfer of RNAs for lysine, glutamic acid, isoleucine, and asparagine, thereby interfering with the normal synthesis and function of mitochondrial proteins (Jiang et al., 2016). In patients with LHON, these mtDNA mutations directly disrupt the production of ATP during oxidative phosphorylation owing to the impaired function of the electron transport chain, leading to energy metabolism disorder (Hu et al., 2024). As RGCs are particularly dependent on mitochondrial energy production for their physiological functions, these mutations ultimately result in cellular degeneration and blindness (Cock et al., 1999). In summary, the clinical manifestations of LHON reflect visual pathway damage caused by mitochondrial dysfunction, while its inheritance pattern exhibits maternal characteristics, whereby all offspring carrying the relevant mutated mtDNA inherit this trait (Chalmers and Schapira, 1999; Huoponen, 2001).

Dominant optic atrophy

Dominant optic atrophy (DOA) is a hereditary optic nerve disorder related to mitochondrial dysfunction and is typically associated with mutations in the optic atrophy 1 (OPA1) gene, which affect mitochondrial fusion and fission. DOA displays a dominant inheritance pattern, and its primary clinical features include optic nerve atrophy, visual impairment, and color vision deficiencies (Zehden et al., 2022). The protein product of the OPA1 gene, OPA1, plays a crucial role in the maintenance of mitochondrial structure and function. It is involved in the regulation of mitochondrial inner membrane fusion and fission processes and is essential for the stability of the mitochondrial network and efficient energy conversion (Lee et al., 2017). Mutation of the OPA1 gene can lead to impaired OPA1 protein function, reducing mitochondrial fusion and increasing fission, thus disrupting the mitochondrial dynamic equilibrium. This imbalance can cause the collapse of the mitochondrial network, reduce energy production, and ultimately result in the damage or death of optic nerve cells (Rahhal-Ortuño et al., 2023). Notably, the clinical manifestation of DOA resulting from OPA1 gene mutation varies significantly among individuals. This variation may be related to the mitochondrial genetic background of the patients, as mtDNA from different individuals may contain modifiers or secondary mutations that can influence the severity and progression of the disease. Mutations in mtDNA other than in the OPA1 gene have also been associated with DOA. For instance, studies have reported mtDNA mutations related to complexes I, III, and IV in patients with DOA (Yu-Wai-Man et al., 2011). These complexes are critical components of the mitochondrial respiratory chain, and any mutation affecting their function can lead to reduced energy production, thus exacerbating damage to the optic nerve.

Pigmentary retinopathy

Pigmentary retinopathy (PR) comprises a group of hereditary eye diseases characterized by functional abnormalities in RPE cells and is closely associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. The clinical symptoms of PR include night blindness, visual impairment, and visual field defects. Over recent years, molecular genetic studies have revealed the important contribution of mtDNA mutations to the pathogenesis of this group of diseases (Zeviani and Carelli, 2021). Specifically, mtDNA mutations can lead to defects in mitochondrial protein synthesis, impaired function of the electron transport chain, and changes in the mitochondrial membrane potential, thereby affecting the metabolism and survival of retinal nerve cells. Mitochondrial gene mutations are not limited to point mutations (single-base substitutions, insertions, or deletions) but also include large-scale rearrangements involving multiple base deletions, duplications, or inversions. The role of these changes in hereditary retinal diseases has garnered increasing attention. For example, the m.3243A>G mutation is commonly found in patients with MELAS (mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes) syndrome, who often exhibit features of retinal pathology (Finsterer and Frank, 2016). Similarly, the m.11778G>A mutation is associated with NARP (neurological hearing loss, ataxia, and pigmentary retinopathy) syndrome (Nie et al., 2023). In addition, specific mutations in genes encoding mitochondrial tRNAs, such as the m.3243A>G mutation in the tRNA-Leu(UUR) gene and the m.12201T>C and m.12262C>T mutations in the tRNA-Ser(UCN) gene, have been confirmed to be associated with retinal pathology (Chujo and Suzuki, 2012). Other examples of mitochondrial mutations related to PR have also been reported, such as the m.8344A>G and m.8356T>C mutations, which have been associated with Leigh syndrome, a progressive neurodegenerative disorder often accompanied by retinal atrophy (Na and Lee, 2023); and the m.9885T>C and m.9206T>C mutations, which are linked to maternally inherited Bénédictin syndrome, which manifests as nystagmus and vision loss, in addition to other neurological symptoms. These findings provide new insights into the molecular basis of PR and lay the foundation for the development of molecular diagnostic and treatment strategies for this disease.

Natural Pathways of Mitochondrial Transfer

Mitochondria are highly dynamic, double-membrane-bound organelles within cells that undergo morphological changes through continuous fusion and fission processes, forming an interconnected network. Mitochondrial transfer between cells, which has recently attracted considerable attention, is crucial for facilitating the integration of exogenous mitochondria with the mitochondrial network of recipient cells, thereby significantly impacting their bioenergetic status and other functional attributes (Picca et al., 2018). Multiple natural pathways for mitochondrial transfer have been identified (Figure 4), some of which are detailed below.

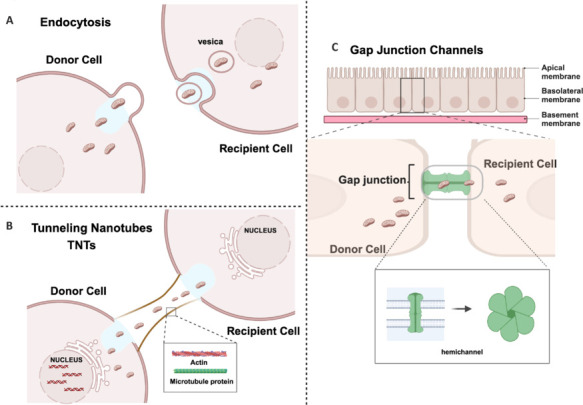

Figure 4.

Natural pathways of mitochondrial transfer between cells.

(A) Endocytosis is the cellular process via which cells internalize extracellular substances by enveloping them with their plasma membrane. (B) Tunnelling nanotubes (TNTs) are slender tubular connections formed between cells that allow for the direct transcellular exchange of materials, including mitochondria. (C) Gap junction channels are hexameric structures composed of connexin proteins. Cells transfer mitochondria between each other through these channels. Created with BioRender.com.

Endocytosis

Endocytosis is the process by which cells internalize extracellular substances by enveloping them with their plasma membrane. This mechanism can also facilitate the transfer of mitochondria between cells through a series of finely coordinated molecular events (Meng et al., 2020). The initial step of mitochondrial transfer involves the recognition of donor mitochondria. Specific cell membrane proteins or signaling molecules can act as receptors that interact with ligands on the surface of mitochondria. This interaction prompts the donor cell membrane to wrap around the targeted mitochondria, a process that requires both precise molecular recognition and changes in membrane dynamics, including the rearrangement of membrane lipids and proteins, resulting in the formation of an endocytic vesicle enclosing the mitochondria (Piacentino et al., 2022). As a vesicle forms, it separates from the membrane of the donor cell, carrying the selected mitochondria. ATP hydrolysis typically provides the energy required for this process (Chen et al., 2022). Notably, the formation and separation of endocytic vesicles are complex processes involving multiple proteins and signaling pathways that collectively ensure the stability and appropriate formation of vesicles. Subsequently, the endocytic vesicle is transported within the donor cell, finally transferring its contents to a recipient cell; this transport relies on cytoskeletal elements such as microtubules and actin filaments, which serve as tracks and driving forces (Holliday et al., 2019; Vinay and Belleannée, 2022). Additionally, various molecular motors such as dynein and kinesin participate in the movement of the endocytic vesicle, propelling it along cytoskeletal tracks towards its target (Jain et al., 2023). When the vesicle reaches the surface of the recipient cell, the next challenge is its fusion with the recipient cell membrane. This step requires the interaction between specific fusion proteins on the vesicle membrane and the corresponding proteins on the recipient cell membrane. This interaction initiates a cascade of events leading to membrane fusion and fission, ultimately allowing the mitochondria to be internalized by the recipient cell. Once inside, the transferred mitochondria must effectively integrate into the new cellular environment. This includes establishing connections with other mitochondria and organelles within the recipient cell and adapting to new biochemical surroundings (Jain et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2023c). The integration process may involve changes in proteins on the outer mitochondrial membrane and other signalling molecules to ensure functional compatibility and stability within recipient cells. The entire mitochondrial transfer process reflects the complexity and fine regulation of intercellular communication.

Tunneling nanotubes

Tunneling nanotubes (TNTs) are slender tubular connections formed between cells that can span considerable distances, allowing for direct intercellular exchange of materials, including mitochondria (Valappil et al., 2022). This process may involve the dynamic reorganization of actin and microtubule networks, as well as signalling pathways associated with the cytoskeleton. The initial formation of TNTs requires the coordinated action of a series of proteins. For instance, cytoskeletal proteins such as tubulin and actin provide structural support to the TNTs (Hanna et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2021a), while membrane-associated proteins, such as linker and adhesion proteins, participate in TNT formation and maintenance (Tishchenko et al., 2020). In addition, some specific cell membrane proteins, as well as receptor proteins located on the outer mitochondrial membrane, are considered to be vital for the interaction between TNTs and mitochondria. Moreover, through their effect on mitochondrial dynamics and distribution, mitochondrial calcium ion channels play an important role in regulating the movement of mitochondria along TNTs (Nemani et al., 2018). In addition to these proteins, some signalling pathways are involved in TNT-mediated mitochondrial transfer. The mTOR signalling pathway makes a significant contribution to TNT formation and maintenance, while the MAPK and PI3K/AKT signalling pathways participate in the regulation of TNT-mediated intercellular communication (Walters and Cox, 2021; Lin et al., 2024). The activation or inhibition of these signalling pathways can affect the function of TNTs and the efficiency of mitochondrial transfer. Some non-coding RNAs and low-molecular-weight RNAs can be transferred between cells via TNTs, thereby regulating signalling pathways and gene expression within target cells, which, in turn, influences mitochondrial function and transfer (Haimovich et al., 2021). In summary, TNT-mediated mitochondrial transfer is a complex process involving the fine regulation of various proteins and signalling pathways.

Gap junction channels

Gap junction channels (GJCs) are hexameric structures composed of connexin proteins. Each channel consists of two hemichannels, each measuring approximately 1.5–2 nm in diameter, that dock on the plasma membranes of two adjacent cells, forming a complete channel that allows for the direct exchange of substances between cells, thereby maintaining the stability of the internal and external cellular environments (Delvaeye et al., 2018). They serve as vital pathways for intercellular communication, enabling the direct exchange of ions, small molecules, and metabolites between neighboring cells, as well as the transcellular transfer of mitochondria (Liu et al., 2022). In response to specific stimuli, such as oxidative stress or inflammatory signals, GJCs allow the transfer of signalling molecules such as calcium ions (Ca2+), IP3, and cAMP, which regulate GJC gating and induce the movement of mitochondria towards the GJCs (Eugenin et al., 2012). Proteins on the mitochondrial surface, such as outer mitochondrial membrane proteins (TOMs) and voltage-dependent anion channels, specifically interact with GJCs during this process, facilitating mitochondria/GJC binding (Kim et al., 2019). Mitochondrial transfer is precisely controlled by a variety of factors, including the GJC gating state, ion concentration gradients inside and outside the cell, the mitochondrial membrane potential, and adhesive forces between cells. As mitochondria pass through GJCs, they may need to undergo fission and deformation to navigate the narrow channel, a process that requires precise spatiotemporal regulation to ensure that mitochondrial integrity and functionality are preserved. Once inside the recipient cell, mitochondria must adapt to their new environment, potentially involving adjustments to their membrane potential and fusion with mitochondria within the recipient cell. This mitochondrial transfer plays a role in various physiological and pathological processes, such as in a myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion injury model. Ruiz-Meana et al. (2014) found that GJCs protein improves mouse myocardial ischemia model by enhancing mitochondrial function. Enhancing the function of GJCs can promote the transfer of healthy mitochondria from undamaged to damaged cells, thus reducing cell death and improving heart function (Rodríguez-Sinovas et al., 2018). The GJC-mediated transcellular transfer of mitochondria is a complex, multistep process involving signal recognition, interactions between mitochondria and GJCs, the transversal of mitochondria, and integration within the recipient cell. However, despite extensive investigation, the underlying molecular mechanisms remain unclear.

Artificial Mitochondrial Transplantation Pathways

The mitochondrial transfer mechanism (Torralba et al., 2016; Chen and Chen, 2024) offers novel perspectives for understanding the role of mitochondria in the regulation of cellular metabolism and their function under different physiological and pathological conditions. It also forms the basis for the treatment of related diseases through mitochondrial transplantation (Zhang et al., 2017; Zhang and Miao, 2023), an innovative therapeutic concept centered on the transfer of healthy mitochondria into damaged or dysfunctional cells to restore or enhance their bioenergetic and physiological functions. This therapeutic approach has shown significant potential for treating a wide array of diseases, particularly neurodegenerative disorders (Gollihue and Norris, 2020), muscular atrophy (Kubat et al., 2023), metabolic diseases (Torralba et al., 2016), and other conditions associated with mitochondrial dysfunction (Chow et al., 2017; Park et al., 2021; Noh et al., 2024). The technical advancements in artificial mitochondrial transplantation are summarized below.

In vitro studies on mitochondrial transplantation techniques

The magnetic mitochondrial transfer method

Several research teams have proposed the use of specific anti-TOM22 antibody-conjugated magnetic microbeads and a magnetic plate to achieve efficient mitochondrial transfer to donor cells (Hornig-Do et al., 2009; Franko et al., 2013; Macheiner et al., 2016). Initially, the magnetic microbeads, which are surface-modified with antibodies capable of recognizing and attaching to the TOM22 protein on the outer mitochondrial membrane, bind to mitochondria. This specific binding allows the magnetic microbeads to precisely connect to healthy functional mitochondria. A strong magnetic field is then used to guide the microbead-attached mitochondria towards the donor cells. Owing to the effect of the magnetic field, mitochondria can be rapidly attracted to the donor cells and be internalized via endocytosis. This process significantly enhances the efficiency and speed of mitochondrial transfer, allowing the transferred mitochondria to accumulate at high concentrations within the donor cells in a relatively short period (Hornig-Do et al., 2009). Macheiner et al. (2016) demonstrated that employing the magnetic mitochondrial transfer method not only significantly improves the efficiency of mitochondrial transfer but also notably enhances the respiration of the recipient cells. This occurs because the transplanted mitochondria retain their functionality in the new environment, providing the required energy for the cells. However, one potential issue with this method is that if non-functional mitochondrial particles are also captured by the anti-TOM22 antibodies on the magnetic microbeads, they can also be transferred to donor cells, thereby reducing the overall efficiency and effectiveness of the transfer process (Franko et al., 2013). Therefore, ensuring that only healthy, functional mitochondria bind to the magnetic microbeads is key to the success of this technique. Overall, magnetic mitochondrial transfer offers new possibilities for treating diseases related to mitochondrial dysfunction by enhancing the efficiency of mitochondrial transplantation and improving cellular energy metabolism.

Technologies based on droplet microfluidics

In 2022, Sun et al. developed a mitochondrial transfer technique based on droplet microfluidics and co-culture. This technology enabled efficient and high-throughput quantitative mitochondrial transfer at the single-cell level. The core of this technology lies in the use of a droplet microfluidics platform, which incorporates precisely controlled modules for droplet generation, observation, and collection, to encapsulate mitochondria and recipient cells within droplets of approximately 40 μm in diameter. The finite space of the droplets restricts the movement of free mitochondria, thereby increasing the likelihood of contact with recipient cells and subsequent endocytosis. Experiments have shown that following 2 hours of co-culture, over 70% of the free mitochondria can be absorbed by C2C12 myoblasts through endocytosis, and the number of absorbed mitochondria can be controlled by adjusting the concentration of the mitochondrial suspension. The advantage of droplet microfluidics lies in its ability to encapsulate single cells into monodisperse droplets, allowing high-throughput analysis and precise control over the local extracellular environment. This technique enables the manipulation of fluids at the nanoliter to picoliter scale within chip channels by precisely controlling the size, shape, and uniformity of the droplets.

Mito-Ception

The core of the Mito-Ception method is the effective extraction of mitochondria from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and their transfer into glioblastoma stem cells (GSCs). Healthy mitochondria are isolated from MSCs under cold conditions through a series of optimized biochemical steps, ensuring the preservation of mitochondrial function and structure. Subsequently, these mitochondria are co-cultured with GSCs, and centrifugal force is employed to facilitate the passage of mitochondria through the cell membrane into the GSCs, thereby achieving transfer. This process not only requires precise operational skills but also relies on specific reagents and equipment, such as EDTA-free protease inhibitors, specially formulated mitochondrial isolation reagents, and precisely controlled centrifuges (Nzigou Mombo et al., 2017). In this co-culture environment, specific chemical signals or natural tendencies facilitate the absorption of mitochondria by the recipient cells. As this process mimics natural phagocytosis, it is referred to as “Mito-Ception.” In 2015, Caicedo et al. found that the transfer of MSC-derived mitochondria using Mito-Ception technology not only improved the function of endogenous mitochondria within MDA-MB-231 cells but also increased energy metabolism and overall function in recipient cells. These findings indicated that the transferred mitochondria can maintain their biochemical activities within new host cells and may have a positive impact on damaged or dysfunctional mitochondria. In 2017, Nzigou Mombo et al. successfully transferred mitochondria from MSCs into a GSM line using the Mito-Ception technique. Jain et al. (2023) further demonstrated that this method not only ensured a high survival rate for the transplanted mitochondria but also enhanced their ability to sustain mitochondrial respiratory activity. This implied that the transferred mitochondria can continue to effectively participate in oxygen consumption and ATP production, both of which are crucial for maintaining the energy balance and overall health of cells.

In vivo studies of mitochondrial transplantation technology

Microinjection

The direct injection method serves to introduce exogenous mitochondria directly into recipient cells. First, healthy mitochondria must be isolated from donor cells or tissues. This is typically achieved through centrifugation to obtain a high-purity mitochondrial suspension. Subsequently, mitochondria can be labelled with specific fluorescent markers, allowing the assessment of their functionality and structural integrity through biochemical analysis. A microinjector or similar device can then be used to directly inject the mitochondria into the recipient tissue. Finally, the successful integration of mitochondria into recipient cells can be verified through microscopic observation and biochemical testing, and their impact on the function of recipient cells can be analyzed (Cloer et al., 2023). In neurodegenerative disease models, the direct injection of healthy mitochondria into damaged neurons can help restore their function (Bai et al., 2024). Chen et al. (2024) showed that the intravenous injection of small extracellular vesicles (EVs) from healthy mouse plasma into aged mice improved mitochondrial energy metabolism, extended lifespan, alleviated aging phenotypes, and improved age-related functional declines in various tissues. Moreover, Cowan et al. (2016) demonstrated that directly injecting mitochondria into the ischaemic region of a rabbit heart after myocardial infarction could reduce infarct size. Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a hereditary disease caused by mutations in mtDNA that affect muscle energy production and function. Dubinin et al. (2024) injected allogeneic mitochondria from healthy animals into the hind limbs of mdx mice (Duchenne muscular dystrophy model) via intramuscular injection, and found that it reduced skeletal muscle damage, lowered creatine kinase levels in muscles and serum, and enhanced grip strength and motor activity in the hind limbs of the animals. Furthermore, the ultrastructure of mitochondria and the interaction between the sarcoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria were normalized in the muscles of treated mdx mice (Dubinin et al., 2024). Norat et al. (2023) reported that directly injecting mitochondria into the brains of ischaemic stroke model rats reduced the extent of brain injury and improved the recovery of neurological function. These findings highlight the therapeutic potential of mitochondrial transplantation for central nervous system diseases and suggest that the direct injection method for mitochondrial transplantation holds promise for therapeutic applications. However, further research is needed to optimize this technique and assess its long-term effects. The advantage of the direct injection method relates to its ability to quickly and efficiently deliver mitochondria to target cells, which is particularly important for tissues or cells that require rapid repair. Additionally, compared to other complex transplantation techniques such as those involving biosynthetic carriers or genetic engineering methods, direct injection does not require complex equipment or lengthy cultivation processes. However, this technique has certain limitations, such as the challenge of precisely controlling the number of mitochondria injected into the cells during the injection process. Both excessive and insufficient quantities can impact the therapeutic effects. Furthermore, although the direct injection method is relatively simple to perform, ensuring the viability and integrity of mitochondria during the injection process requires precise operational techniques and equipment support. These are areas that will require technological innovation and improvements.

Nanotechnology-based targeted mitochondrial transplantation

In medicine, the application of nanotechnology has unlocked new possibilities, particularly for mitochondrial transplantation. To protect their integrity during delivery and enhance delivery efficiency, mitochondria are encapsulated in biocompatible and biodegradable nanomaterials, such as lipids or polymer nanoparticles (Yan et al., 2022; Yuan et al., 2023). These nanoparticles combine with mitochondria through specific techniques, such as ultrasonic agitation or rotary evaporation, forming an encapsulated complex, a process that requires precise control to ensure adequate encapsulation of the mitochondria. Subsequently, specific ligands or antibodies are modified on the surface of nanomaterials to improve stability and achieve precise localization to damaged tissue (Yan et al., 2022). Sun et al. (2023) reported a novel therapeutic agent, named the PEP-TPP-mitochondrial complex, which consists of a specially designed peptide (CSTSMLKAC, referred to as PEP) and a triphenylphosphonium cation (TPP+). This complex leverages the ability of PEP to sense ischaemic environments and accurately target damaged cardiac tissue. Upon reaching its target, PEP is released from the complex, allowing the mitochondria to be absorbed by heart cells or transferred through vascular endothelial cells. This process restores energy metabolism and mechanical contraction functions in cardiac cells while also reducing cell death and inflammatory responses. The intravenous transplantation of the PEP-TPP-mitochondrial complex effectively alleviated myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion injury, providing a novel strategy for the treatment of complications following heart attacks. Zhong et al. (2022) revealed that mitochondria encapsulated in nanotechnology-based carriers can cross the blood–brain barrier, offering new avenues for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. With the continuous advancement and optimization of nanotechnology, mitochondrial transplantation based on this method is expected to play an increasingly important role in medical treatment. The primary advantage of using nanotechnology for mitochondrial transplantation is its high precision. Using nanotechnology, mitochondria can be accurately targeted and delivered to damaged cells, improving the efficiency of treatment. Additionally, using nanocarriers, the timing and quantity of mitochondrial release can be controlled, ensuring therapeutic continuity and effectiveness. Nevertheless, this method has several limitations. First, the development and manufacture of nanotechnology-related drug delivery systems are costly and technically complex. Second, rigorous safety assessments are needed to evaluate the toxicity of nanomaterials to human cells. Finally, ensuring the stability of mitochondria during delivery and release also represents a challenging technical hurdle.

Exosome-mediated mitochondrial transplantation

Exosomes comprise a class of membrane vesicles secreted by cells into the external environment. They are characterized by a single or multiple lipid bilayer membrane structure that encapsulates numerous bioactive molecules, such as proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, and metabolic products (Kalluri and LeBleu, 2020). These contents can enter target cells through either exosomal membrane-associated proteins or receptor-mediated endocytosis, thereby affecting target cell function. Exosomes exhibit diverse morphological characteristics and are typically spherical, elliptical, or cup-shaped, with sizes ranging from 30 to 150 nanometers. Exosomes play important roles in intercellular communication and material transport and perform important biological functions (Krylova and Feng, 2023). Leveraging these natural mechanisms, healthy mitochondria can be transferred from donor to recipient cells via exosomes, thereby restoring or enhancing the function of damaged cells. Initially, exosomes containing mitochondria are isolated from healthy donor cells. Following their absorption by recipient cells through endocytosis, they fuse with the inner membrane of the recipient cell, releasing the mitochondria. These exosomal-encapsulated mitochondria subsequently interact and integrate with native mitochondria within the recipient cell, thereby enhancing its energy production and biosynthetic capabilities (D’Acunzo et al., 2022; Xia et al., 2022; Yan et al., 2023).

Exosome-mediated mitochondrial transplantation technology has shown significant potential for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases, especially ischaemic heart disease. The use of mitochondria-rich exosomes obtained from autologous stem cell-derived cardiac cells can effectively restore energy metabolism and function in the ischaemic myocardium (Hogan et al., 2019). Autologous exosomes have low immunogenicity and high biocompatibility. The natural targeting ability of exosomes and their capacity to penetrate biological barriers make them ideal carriers for delivering mitochondria directly into damaged tissues. Moreover, neural stem cells (NSCs) have been shown to transfer functional mitochondria to damaged cells through secreted EVs, providing new perspectives for the treatment of multiple sclerosis and other degenerative neurological diseases (Lee et al., 2016; Li et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020). Ikeda et al. (2021) reported that NSCs can package mitochondria within EVs and subsequently release them in recipient cells while maintaining normal mitochondrial ultrastructure and function. Following absorption by recipient cells, these mitochondria can integrate and restore mitochondrial function, thus improving cell survival rates and reducing inflammatory responses. Successful application in animal models not only confirmed the therapeutic potential of delivering functional mitochondria via NSC-derived EVs but also paved the way for developing new therapies targeting mitochondrial dysfunction. In summary, exosome-mediated mitochondrial transplantation technology, an emerging therapeutic approach, has demonstrated potential in treating various diseases in laboratory studies, particularly in the field of cardiovascular diseases.

The advantage of exosome-mediated mitochondrial transplantation technology lies in the fact that exosomes are naturally produced by cells, and thus have high compatibility and usually do not trigger strong immune responses, making them ideal biological carriers. Regarding limitations, exosome extraction and purification are technically demanding and relatively costly processes, which restrict their large-scale application. Additionally, the production and application of exosomes lack standardized methods, which may affect the consistency and reproducibility of results.

Role of Mitochondrial Transplantation in the Treatment of Retinal Degenerative Diseases

Mitochondrial transplantation, a cutting-edge biomedical technology, has garnered significant attention in the field of vision science over recent years, particularly given its potential as a treatment for retinal degenerative diseases (Lopez Sanchez et al., 2016). Retinal neurons have extremely high energy demands and rely on healthy mitochondria to sustain their function. When mitochondria become dysfunctional due to genetic or environmental factors, they lose the ability to effectively produce the necessary cellular energy, and retinal neurons begin to degenerate, ultimately leading to visual impairment. Mitochondrial transplantation seeks to restore the vitality of these energy-metabolism-compromised retinal neurons through the transfer of healthy, normally functioning mitochondria, potentially slowing or even halting disease progression (Subramaniam et al., 2020). This strategy is theoretically compelling because, if successfully implemented, it may offer a novel therapeutic pathway for retinal conditions that currently lack effective treatments.

Related experimental studies have demonstrated the potential of mitochondrial transplantation both in vitro and in animal models. Indeed, some studies have indicated that replenishing mitochondria can improve the survival rate of retinal neurons and partially restore visual function. Despite these encouraging preliminary results, mitochondrial transplantation still faces significant challenges in clinical applications.

Targeted mitochondrial transplantation for the treatment of retinal degenerative diseases related to retinal pigment epithelium/photoreceptors

RPE/photoreceptors, situated in the outer layers of the retina, have been implicated in a class of eye disorders, including AMD, RP, and choroidal neovascularization (Wu et al., 2022; Noh et al., 2023). Mitochondrial abnormalities are closely associated with the onset and progression of these diseases. Mitochondrial function can be influenced by a wide variety of factors, including genetic predisposition, environmental factors, and lifestyle choices. Compromised or abnormal mitochondrial function can lead to cellular metabolic disorders and augmented oxidative stress responses, which promote the development and progression of ocular diseases (Ruiz-Meana et al., 2014; Jiang et al., 2019).

Mitochondrial transplantation, a cutting-edge biotherapeutic strategy, has shown notable potential for the treatment of retinal degenerative diseases. Noh et al. (2024) showed that in an oligomeric (soluble) amyloid-beta (oAβ)-induced RPE cell damage model, the transplantation of mitochondria derived from MSCs elicited significant cytoprotective effects. These exogenous mitochondria not only restored energy metabolism in damaged cells but also prevented the destruction of tight junction proteins and promoted the clearance of intracellular oAβ. This finding offers new therapeutic insights for diseases that are associated with oAβ accumulation, such as AMD. In another study focusing on aging-related mechanisms, exogenous mitochondria were introduced into ARPE-19 cells that had been induced into a senescent state closely related to the pathogenesis of AMD (Chen and Chen, 2024). The results showed that mitochondrial transplantation effectively reversed several hallmarks of aging, that is, it reduced cell enlargement, suppressed senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity, inhibited the activation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), decreased the production of inflammatory cytokines, and downregulated the expression of senescence-associated proteins, including p21 and p16 (Noh et al., 2023). This suggests that mitochondrial transplantation may help counter or delay the progression of retinal degenerative diseases by enhancing the bioenergetic status of damaged cells and alleviating oxidative stress responses. Furthermore, Wu et al. (2022) demonstrated that the injection of allogeneic mitochondria into the vitreous cavity of Royal College of Surgeons (RCS) rats significantly slowed photoreceptor degeneration. These rats carry a mutation in MertK, a receptor tyrosine kinase gene, leading to impaired phagocytosis in retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells. The RCS rat is a well-established disease model for retinitis pigmentosa (RP) in humans (Deng et al., 2012; Conlon et al., 2013). Optical coherence tomography observations revealed that retina thickness loss was attenuated in rats receiving mitochondrial transplantation compared with that of controls, while visual evoked potential tests indicated that electrical signal conduction from the retina to the cerebral cortex was improved in treated rats.

Although these findings provide a theoretical basis and experimental evidence for the therapeutic value of mitochondrial transplantation in retinal degenerative diseases associated with mitochondrial dysfunction, further in-depth and detailed studies are warranted to explore the long-term safety, optimal transplantation methods, dose-response relationships, and potential clinical translation of this therapy.

Mitochondrial transplantation as a targeted therapeutic approach for retinal degenerative diseases associated with retinal ganglion cells

RGCs are located in the inner layer of the retina and are crucial for retinal health and visual signal transmission (Miao et al., 2023). Given their particularly high demand for oxygen and energy, RGCs are sensitive to mitochondrial dysfunction. Compromised mitochondrial function results in decreased ATP generation and an increase in the levels of ROS, which can lead to damage or even apoptosis in RGCs (Wang et al., 2014). For instance, glaucoma, a leading global cause of irreversible blindness, is closely associated with mitochondrial dysfunction in RGCs. These cells rely on mitochondria not only to meet their energy demands but also for their central role in regulating oxidative stress, calcium ion balance, and apoptotic pathways. The disruption of energy metabolism in these cells, as observed in LHON—a condition resulting from specific mitochondrial gene mutations that lead to degenerative changes in RGCs—leads to vision impairment (Subramaniam et al., 2022). In response to such diseases, the development of therapeutic strategies involving mitochondrial transplantation has gained increasing research attention, with the basic principle being the introduction of healthy mitochondria into damaged cells to restore normal function. In research on oxidative stress-related diseases such as neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, and cardiovascular diseases, rotenone is used as a chemical tool to induce oxidative stress (Zavatti et al., 2020). Vrathasha et al. (2022) found that mitochondrial transfer significantly improves ATP production and oxygen consumption under oxidative stress in rotenone-treated human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC)-derived RGCs, confirming the therapeutic potential of mitochondrial transplantation for improving cellular energy metabolism. Yang et al. (2020) generated hiPSCs from healthy individuals, asymptomatic LHON gene mutation carriers, and symptomatic LHON patients and identified a connection between the levels of ROS and the apoptosis of hiPSC-derived RGCs due to point mutations in the LHON-associated MT-ND4 gene. The authors further found that LHON-affected RGCs exhibited increased retrograde transport of mitochondria and decreased expression of the KIF5A protein, effects that were effectively reversed by the application of the antioxidant N-acetyl-L-cysteine. Introducing exogenous mitochondria into RGCs through co-culture or direct injection can effectively improve the survival rate of damaged cells, ameliorate oxidative stress, and exert therapeutic effects in animal models. For example, in a LHON model, mitochondrial transplantation slowed disease progression and partially restored visual function, showing potential for clinical application (Wong et al., 2017). Nascimento-Dos-Santos et al. (2020) confirmed the impact of the transplantation of active mitochondria isolated from the liver on the survival and axonal growth of RGCs after an optic nerve crush injury. They found that intact active mitochondria transplanted into the vitreous cavity of rats were absorbed by the retina, with improvements in oxidative metabolism and electrophysiological activity being detected one day after transplantation. Additionally, on day 14, cell survival was increased in the ganglion cell layer, while on day 28, more axons were observed to extend beyond the injured area compared with the controls; these effects depended on the structural integrity of the organelles. The progress of mitochondrial transplantation related to retinal diseases is shown in Figure 5, while publications on mitochondrial transplantation for retinal degenerative diseases are summarized in Table 1.

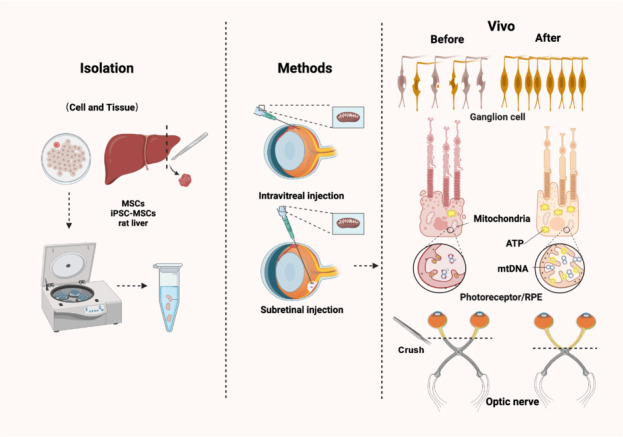

Figure 5.

Mitochondrial transplantation targeting retinal diseases.

Mitochondria are extracted from pluripotent stem cells and tissues. In vivo experiments, such as implantation through intravitreal injection or subretinal injection, among other methods, can improve the mitochondrial impairment-induced structural and functional damage in RGCs, photoreceptors, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), and optic nerve. Created with BioRender.com. iPSC: Induced pluripotent stem cell; MSCs: mesenchymal stem cells; RGCs: retinal ganglion cells.

Table 1.

Recent advances in mitochondrial transplantation for retinal degenerative diseases

| References | Study designs | Sources of isolation | Transplantation methods | Results | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noh et al., 2024 | In vitro and in vivo | Bone marrow mononuclear cells | Co-incubation, intravitreal injection | Transplanting mitochondria into RPE cells and mice exposed to oligomeric amyloid-beta can reduce mitochondrial impairment and prevent the degradation of tight junction proteins. | Exogenous mitochondrial delivery is a plausible therapeutic approach for treating AMD. |

| Noh et al., 2023 | In vitro | MSCs | Co-incubation | Mitochondrial transplantation improved function and mitigated the effects of senescence (increases in cell size, SA-β-Gal contents, nuclear factor kappa B activity, inflammation, and p21/p16 levels). | Exogenous mitochondrial delivery may be a plausible therapeutic approach for AMD. |

| Wu et al., 2022 | In vivo | Rat liver | Intravitreal injection | Evaluation of allogeneic mitochondrial transplantation as a novel treatment for retinal degeneration using Royal College of Surgeons rats, a model for inherited retinal degeneration resembling retinitis pigmentosa. | Mitochondria transplanted into the vitreous humor improves photoreceptor degeneration in Royal College of Surgeons rats and may hold potential for clinical use. |

| Vrathasha et al., 2022 | In vitro and in vivo | Human skeletal muscle cells | Co-incubation, intravitreal injection | hiPSC-RGCs were exposed to rotenone to induce oxidative stress. Subsequently, hiPSC-RGCs were incubated with exogenous mitochondria; additionally, exogenous mitochondria were administered through intravitreal injection into the retinas of C57BL/6 mice. | Mitochondrial transplantation is a viable therapeutic strategy for rescuing RGC function and can be used as a mitigating treatment for optic neuropathies. |

| Aharoni-Simon et al., 2022 | In vitro | C57BL/6 or BALB/c mouse livers | Co-incubation | Isolated mitochondria were introduced into C57BL/6 mouse-derived 661W retinal ganglion precursor-like cells and the dynamics of mitochondrial transplantation were examined under normal and oxidative-stress conditions in retinal ganglion precursor-like cells. | Moderation of oxidative stress significantly enhances exogenous mitochondrial survival in the cells. |

| Butcher, 2021 | In vitro | Human RPE cell line, ARPE-19 | Co-incubation | Human RPE cells were exposed to an AMD-relevant cytokine to simulate AMD-related pathological mitochondrial dysfunction and inflammatory responses. | Mitochondrial incorporation as a potential novel therapeutic strategy was effective in improving the bioenergetic state central to the pathogenesis of globally critical diseases such as AMD. |

| Nascimento-Dos-Santos et al., 2020 | In vivo | The liver | Intravitreal injection | Assessment of the effect of liver-isolated mitochondria on the survival of retinal ganglion cells and axonal outgrowth after optic nerve crush. | Mitochondria transplantation is a promising approach for future therapeutic interventions for central nervous system damage. |

| Jiang et al., 2020 | In vitro and in vivo | MSCs | Co-incubation, subretinal injection | The oxygen consumption rate was measured in recipient cells to assess the impact of intercellular mitochondrial transfer; additionally, the changes in metabolic gene expression within recipient cells that had received donated mitochondria were examined. | MSCs are efficient mitochondrial donors to various ocular cells; tunneling nanotubes and donated mitochondria lead to an improvement in metabolic function in recipient ocular cells. |

| Jiang et al., 2019 | In vivo | Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived MSCs (iPSC-MSCs) | Intravitreal injection | Intravitreally injected human iPSC-MSCs were investigated for their ability to rescue RGCs through mitochondria transfer in a mouse model of mitochondrial complex I (NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase) deficiency. | Intravitreally injected human iPSC-MSCs can donate mitochondria to retinal cells and protect RGCs against mitochondrial impairment-induced retinal degeneration. |

| Wong et al., 2017 | In vitro | Human epidermal keratinocytes (System Bioscience) | Cybrid generation | hiPSCs were used to model LHON; mutation-free iPSCs were generated via the replacement of LHON mtDNA. | Mitochondrial replacement may be a feasible strategy for correcting mtDNA mutations in iPSC-related models and could be applied to mtDNA disease models other than LHON. |

AMD: Age-related macular degeneration; hiPSCs: human iPSCs; iPSC: induced pluripotent stem cell; LHON: Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy; MSCs: mesenchymal stem cells; RGC: retinal ganglion cell; RPE: retinal pigment epithelial.

Mitochondrial transplantation therapy targeting Müller cell mitochondrial dysfunction

Mitochondrial dysfunction and Müller cell gliosis are important pathological features of blindness caused by retinal degeneration (Deng et al., 2012; Conlon et al., 2013; Zavatti et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2023). Müller cells, prominent macroglia in the retina, play critical roles in retinal metabolism, antioxidant defenses, and neural nutrition. Mitochondrial dysfunction has been identified as a key driver of Müller cell gliosis, a phenomenon that has been confirmed in diabetic retinopathy and AMD (Bringmann et al., 2006). Reshaping retinal Müller cell fate has been proposed as a key mechanism for treating degenerative retinal diseases. Huang et al. (2024a) found that retinal progenitor cells from human embryonic stem cell-derived organoids (hERO-RPCs) transferred EVs to Müller cells after subretinal transplantation into RCS rats. Furthermore, small EVs collected from hERO-RPCs were found to delay photoreceptor degeneration and protect retinal function in RCS rats. Hutto et al. (2023) investigated mitochondrial homeostasis in vertebrate cone photoreceptors and found that damaged mitochondria shifted from their normal cellular positions and were transferred to Müller cells, indicating that transmitophagy from cone cells to Müller cells occurs as a response to mitochondrial damage. Huang et al. (2024b) transplanted mitochondria from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) into Müller cells through cell fusion and TNTs and noted that the integration of BMSC-derived mitochondria (BMSCs mito) into Müller cells improved mitochondrial function, reduced oxidative stress and gliosis, and partially protected visual function in the degenerative rat retina.

Challenges and Limitations of Mitochondrial Transplantation in Treating Retinal Degenerative Diseases

The aim of ocular mitochondrial transplantation is to restore visual function via the introduction of healthy mitochondria into damaged retinal neurons. However, this approach faces various challenges, such as the technical complexity of ocular injections, the limited survival of transplanted mitochondria, and the possibility of immune rejection (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Difficulties and challenges in mitochondrial transplantation.

Mitochondrial transplantation faces a variety of challenges, such as the technical complexity of intraocular injections, limitations in the survival rate of transplanted mitochondria, the risk of immune rejection, and moral and ethical issues. Created with BioRender.com.

Technical complexity

Common approaches employed for ocular mitochondrial transplantation typically involve intravitreal, subretinal, and intravenous injections, which are the conventional drug delivery methods in ophthalmic research (Del Amo EM et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2022b). However, these procedures are technically difficult and can lead to complications. The challenges lie in the following points. First, the eyeball is a relatively small and enclosed spherical organ with various tissue barriers, such as the blood-ocular barrier and the vitreoretinal barrier. Precisely delivering transplanted mitochondria to target cells and ensuring their functionality remain significant challenges (Hashida and Nishida, 2023; Mishra et al., 2023). Administering transplanted mitochondria via intravenous injection is relatively uncomplicated, but breaching the blood-ocular barrier to reach the target tissue requires careful consideration. Intravitreal injection, while relatively simple, is hindered by the need to penetrate the vitreoretinal barrier to access the target cells (Lee et al., 2022a). Meanwhile, subretinal injection demands high precision at the injection site, necessitating accurate delivery of transplanted mitochondria into the space between the retina and the RPE, thus presenting operational difficulties (Hartman and Kompella, 2018; Simunovic et al., 2023). Secondly, the interior of the eyeball is an immunologically privileged site, where exogenous bacterial or fungal contamination can lead to severe infection and inflammation (Durand, 2017). Furthermore, complications arising from inadequately executed intraocular injections can cause retinal detachment, traumatic cataract, secondary glaucoma, and other complications, which can pose a serious threat to visual function if severe, making the procedure of mitochondrial transplantation in the eye challenging (Verma et al., 2020; Valentín-Bravo et al., 2022).

Survival rate of transplanted mitochondria

The survival rate of transplanted mitochondria is influenced by a variety of factors, with the quality of the isolated mitochondria being a primary determinant; optimizing the isolation method to enhance the quality of the extracted mitochondria is essential to ensure their successful entry into cells as well as their functionality post-transplantation (Kong et al., 2023). Additionally, to maintain their activity levels, isolated mitochondria should be stored at low temperatures only for short durations. Accordingly, isolated mitochondria must be used for transplant surgery within a short time to increase the success rate of the treatment (McCully et al., 2017; Doulamis and McCully, 2021). The scope for the application of mitochondrial transplantation is greatly restricted, and strict screening and assessment of mitochondria must be conducted before transplantation to ensure the selection of high-quality mitochondria (Hwang et al., 2021). Furthermore, different methods of mitochondrial transplantation have varying effects on the mitochondrial survival rate (Zhong et al., 2023). For instance, during mitochondrial transplantation through intravenous injection, the mitochondria must reach the target tissue or cells via the bloodstream, and factors such as haemodynamics and vascular permeability can affect their survival rate. For ocular mitochondrial transplantation, it is necessary to choose an appropriate administration method based on the disease mechanism and location to improve the survival rate of transplanted mitochondria. Thus, enhancing the survival rate of transplanted mitochondria is a key issue that needs to be addressed.

Immune rejection response

The immune system of ocular tissues is complex, and transplantation of heterologous cells may trigger an immune rejection response. Therefore, ensuring that mitochondria are not recognized as foreign bodies by the immune system and avoiding rejection are key issues for consideration (Hwang et al., 2021; Gurnani et al., 2024). Mitochondrial transplant rejection mainly includes the following aspects: 1) Differences in mtDNA. Mitochondria possess their own genome, mtDNA, which differs among individuals. Rejection may occur if the host immune system detects these differences and triggers an immune response, potentially resulting in rejection (Newman and Shadel, 2023). 2) Tissue incompatibility. Mitochondrial transplantation involves the injection of healthy mitochondria into damaged cells. If the host and donor tissue types do not match, such as in mitochondrial transplantation between humans, the host immune system may recognize the donor mitochondria as foreign bodies and trigger a rejection response (Smeets et al., 2023). 3) Immune monitoring and response. The immune system monitors and recognizes foreign substances. Once donor mitochondria are detected by the immune system, a series of immune response mechanisms may be activated, including inflammatory reactions and antibody production, to eliminate these foreign substances (Sattler, 2017; Műzes et al., 2022). Therefore, for mitochondrial transplantation therapy in eye diseases, it is necessary to optimize the selection and screening of mitochondria, regulate immune responses, and use immunosuppressants. In addition, research on mitochondrial transplantation is still in its early stages, and further experiments are required to verify its safety and effectiveness.

Moral and ethical issues

Given its interventionist nature, ocular mitochondrial transplantation must comply with ethical and legal regulations (Mitalipov and Wolf, 2014). Ensuring informed consent from patients and their full understanding of the potential risks is crucial. Additionally, owing to its novelty, mitochondrial transplantation therapy involves a range of complex moral and ethical issues (No authors listed, 2012; Zhang and Miao, 2023). For instance, patient autonomy is paramount; accordingly, patients have the right to be informed, and their participation in treatment must be voluntary. Furthermore, patients must fully understand the potential risks, advantages and disadvantages, and possible long-term effects of the treatment to allow them to make informed decisions. Secondary considerations include safety and efficacy, which must be ensured before mitochondrial transplantation therapy is administered in a clinical setting. This requires exhaustive laboratory research and clinical trials to assess the potential side effects and therapeutic outcomes. The long-term impact of ocular mitochondrial transplantation also needs to be considered. As mitochondrial transplantation for eye diseases is an emerging treatment method, there is a lack of long-term monitoring and follow-up with patients. Overall, mitochondrial transplantation therapy involves many complex moral and ethical issues that require multifaceted considerations and in-depth evaluation. Doctors, researchers, ethicists, and policymakers must work together to ensure the safety, fairness, and acceptability of treatment.

Limitations

Mitochondrial transplantation is an emerging therapeutic approach that has shown potential in treating retinal degenerative diseases; despite its promise, related research and reviews have also highlighted several significant limitations of this approach. First, studies to date have largely focused on animal models and in vitro experiments, and large-scale, long-term, clinical trial data to evaluate the safety and efficacy of mitochondrial transplantation in treating human retinal diseases is lacking. Second, the technical complexity of mitochondrial transplantation raises significant challenges in ensuring the successful integration and long-term functionality of the transplanted mitochondria within retinal cells. Additionally, the pathophysiology of retinal degenerative diseases is complex, and simple mitochondrial dysfunction often does not fully explain the progression of a given disease, suggesting that mitochondrial transplantation may not independently resolve all pathology-related issues. Moreover, individual differences and disease heterogeneity may lead to significant variability in how patients respond to mitochondrial transplantation, making it difficult to guarantee the universality and consistency of treatment. Therefore, although mitochondrial transplantation shows promise in treating retinal degenerative diseases, its practical application still faces many limitations, and future research should focus on its safety, efficacy, and operability.

Future Research Directions for Mitochondrial Transplantation in the Treatment of Retinal Degenerative Diseases

Mitochondrial transplantation for the treatment of retinal degenerative diseases is a cutting-edge field with significant therapeutic potential. Future research directions might include the following key areas. 1) Improving transplantation efficiency. Research should focus on how to enhance the efficiency and survival rate of mitochondria within retinal cells. This may involve developing new carrier systems, such as utilizing nanotechnology or exosomes, to transport mitochondria while also protecting them, ensuring they can effectively integrate into host cells. 2) Enhancing precise targeting techniques. Accurately delivering mitochondria to damaged retinal cells is also a crucial research direction. Engineered targeting strategies could include specific cell markers to enhance the reparative effects post-transplantation. 3) Increasing the long-term effects and assessing safety. As clinical trials progress, it will be essential to evaluate the long-term impact of mitochondrial transplantation on retinal function as well as its safety. This involves monitoring the durability of treatment effects and potential adverse reactions. 4) Performing more in-depth mechanistic studies. Understanding how mitochondrial transplantation affects the metabolic, genetic, and biochemical processes of retinal cells is also vital. Mechanistic studies will help optimize treatment plans and may reveal new therapeutic targets. 5) Customizing personalized treatment strategies. Given the heterogeneity of retinal degenerative diseases, future research should also explore how to tailor treatment plans based on specific patient conditions, including the type of mitochondria, timing, and method of transplantation. These areas will become the directions for further research into the development of mitochondrial transplantation technology.

Conclusion