Abstract

Men taking anti-oxidant vitamin E supplements have increased prostate cancer (PC) risk. Whether pro-oxidants protect from PC remained unclear.

We show that a pro-oxidant vitamin K precursor (MSB) suppresses PC progression in mice, killing cells through an oxidative cell death: MSB antagonizes the essential class III PI 3-Kinase VPS34, the regulator of endosome identity and sorting, through oxidation of key cysteines, pointing to a redox checkpoint in sorting. Testing MSB in a myotubular myopathy model that is driven by loss of MTM1, the phosphatase antagonist of VPS34, we show that dietary MSB improved muscle histology, function and extended life span.

These findings enhance our understanding of pro-oxidant selectivity and show how definition of the pathways they impinge on can give rise to unexpected therapeutic opportunities.

Introduction

With an estimated 299,000 new diagnoses in 2024, prostate cancer (PC) remains the second most frequent tumor diagnosed in men and the second leading cause of male cancer deaths in America (1). Therapeutic options for localized PC are effective, however, metastatic PC is a yet incurable disease because standard of care anti-androgen therapy over time results in relapse of incurable disease. Therefore, there is much interest in how lifestyle and diet affect this slow growing cancer. The SELECT trial followed some 35,000 men over 10 years to test for benefits of dietary anti-oxidant supplements on risk of PC diagnosis. The trial unambiguously revealed the tumor promoting, not reducing effects of anti-oxidants on PC (2, 3). However, it has remained unclear if vice versa, pro-oxidant supplements are a viable strategy to stave off the disease. Therefore we tested if pro-oxidant therapy could protect from PC progression.

Dietary MSB treatment suppresses prostate cancer progression

We used RapidCaP, an approach for somatic gene transfer of Cre-recombinase and luciferase transgenes into prostate of PtenloxP/loxP; Trp53loxP/loxP mice. This results in focal tumor initiation followed by lethal metastasis at high penetrance in a fully native environment (4–6). We monitored intensity and spread of PC by weekly bioluminescence imaging (BLI) to combine the rigor of genetically engineered mouse (GEM) models with an unbiased account of disease progression throughout the body. As pro-oxidants, we tested two approaches: the vitamin K precursor menadione (also known as vitamin K3, VK3), administered in its water soluble form, menadione sodium bisulfate (MSB), and the combination of MSB with vitamin C (VC). VC has been shown to oxidize cancer cells in vitro and in vivo (7–10). The selective uptake and intracellular reduction of dehydroascorbic acid in a genetically engineered mouse (GEM) model for PC has been demonstrated using hyperpolarized magnetic resonance spectroscopy (8, 11), and the combination with MSB has been proposed to enhance pro-oxidant function (12). Twenty-five animals with a spectrum of primary and metastatic disease burden as judged by BLI were enrolled and randomized into the 3 trial arms: Water (10 animals), MSB (in drinking water at 150 μg/ ml, 7 animals), or MSB plus vitamin C (MSB & VC, = MSB plus 1.5 mg/ ml of sodium ascorbate, 8 animals). Treatments were prepared freshly from powder every day.

Imaging the 3 cohorts weekly for 18 weeks revealed that in contrast to the steady disease progression in the water control group, the two treatment groups showed a marked treatment response, durable response and no adverse weight change compared to water (Fig. 1A, B, fig. S1A–C). This was in contrast to castration therapy of RapidCaP, where a treatment response is shorter than 60 days and invariably followed by castration resistance, as seen by sharp BLI increase and lethal disease progression (see Fig. 1C and (4)). One animal each in the MSB and in the MSB & VC treatment group also showed lethal 1300% and 1400% increase in disease burden (fig. S1B,C), and they were confirmed as statistical outliers. In spite of the previously reported in vitro synergy (12), VC addition did not improve on MSB treatment in our hands. We measured vitamin C and found no VC increase beyond endogenous levels in liver and prostate of trial animals upon oral VC (fig. S2A,B). Note that mice, like most mammals (but not humans), are able to generate their own VC. This finding suggested that high dose injection of VC is critical to study its oxidative anti-cancer efficacy in mice, as has been published previously in prostate (8, 11) and colorectal cancer (9). In contrast, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis confirmed that the oral MSB treatment regimen delivered MSB to prostate, where it acted as a pro-oxidant (Fig. 1D, fig. S2C). No effects on coagulation were seen upon oral MSB (fig. S2D).

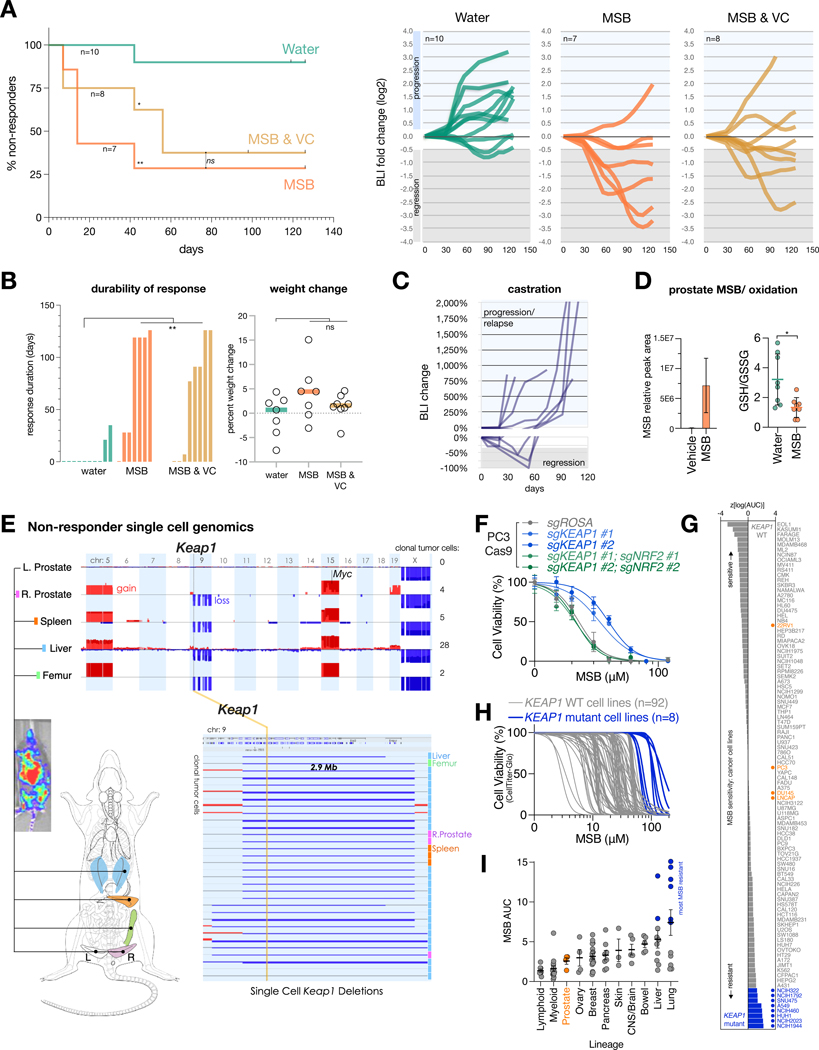

Figure 1. MSB suppresses PC progression and induces oxidative stress.

(A) Left: Kaplan-Meier analysis of treatment response as defined by 4 consecutive BLI measurements showing partial response using RECIST criteria (at least 30% reduction in BLI, see also fig. S1A). P values were calculated using the Mantel-Cox test. ns, not significant. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Right: line plots showing disease progression over time based on weekly log2-fold change in tumor BLI signal for each trial mouse (moving average of 5 consecutive measurements). Bounds based on RECIST criteria for regression (at least 30%) and progression (at least 20%) are indicated in gray and blue shading, respectively. Start-/ endpoint BLI images and analyses are shown in fig. S1A–C.

(B) Left: Durability of treatment response (at least 30% reduction) in the three trial arms. Right: percent weight change over 18 weeks (126 days). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test for multiple comparisons of treatments vs water group was used. **P < 0.01, ns, not significant.

(C) Reference RapidCaP trial for standard of care castration therapy as published in (4), showing regression and relapse kinetics.

(D) Left: LC-MS analysis of MSB abundance in the prostates of animals treated with water or MSB (n=5 biologically independent samples). Right: Redox status indicated by the GSH/GSSG ratios in prostates of mice treated with water (n=8 biologically independent samples) or MSB (n=8 biologically independent samples). Data are mean ±s.e.m (left) and mean ±s.d (right). P values were calculated using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test. *P < 0.05.

(E) Single nucleus whole genome copy number analysis (CNA) of a resistant RapidCaP clone that has metastasized from prostate to liver, spleen, and bone and harbors a deletion involving Keap1. See Figures S1C and S2G for disease progression.

(F) Cell viability curves for the indicated CRISPR-Cas9 derived isogenic human PC3 cell lines treated with increasing concentrations of MSB for 24 hours (n=3 biologically independent samples). Data are mean ± s.d.

(G) Waterfall plot of z-scores of log(AUC) values, representing MSB sensitivities of 100 cancer cell lines. Blue indicates cancer cell lines with KEAP1-loss of function, damaging or hotspot mutations. PC cell lines are shown in orange.

(H) Cell viability curves of the 100 cancer cell lines (gray = KEAP1 WT; blue = KEAP1 mutant) treated with increasing concentrations of MSB for 24 hours (n=3 biologically independent samples).

(I) Relationship between MSB potency and lineage for a subset of cancer cell lines tested in (H). Cancer cell types are ranked by their average MSB sensitivity. Blue indicates cancer cell lines with KEAP1-loss of function, damaging or hotspot mutations. PC cell lines are shown in orange. Data are mean ± s.e.m.

We reasoned that the resistant tumors might contain valuable information on the underlying mechanisms behind both MSB-induced disease regression and resistance. Since the native tumors and metastases of the RapidCaP system are much smaller than in human, we could not simply harvest lesions for molecular probing. Instead, we turned to single nucleus sequencing of whole genome copy number alteration (CNA), the driving force behind PC evolution (13, 14). Luciferase-guided harvesting of suspected tumor regions (see fig. S2E, bottom) followed by FACS sorting of DAPI stained nuclei indeed allowed us to isolate 414 single nuclei from 5 tissues of an MSB-resistant animal: left anterior prostate (normal control lobe), right anterior prostate (tumor-containing lobe), femur, spleen, and liver. These were subjected to single nucleus whole genome sequencing (SNS) to identify and characterize the cancer cells, as previously published for human PC samples (15, 16). The genomes at each site included many tumor-diluting putative normal cells (0% CNA), just like the normal left anterior prostate (fig. S2E). In contrast, the right anterior prostate (origin of disease in RapidCaP) and the luciferase-positive metastatic sites both also harbored cells with significantly (P < 0.0001) increased spontaneous CNA (note that the Cre-mediated Pten/ Trp53 deletions are below our CNA detection limit of 600 kb). This resembled the principle of progression first shown in human PC (13). Furthermore, analysis of all 414 single nucleus genomes also revealed cells with recurrent CNA (fig. S2F). Focus on 60 cancer cells with clonal CNA revealed increasing degrees of complexity: prostate < spleen < liver, potentially delineating a route of metastasis (fig. S2G–I). As shown in Fig. 1E, the cancer clone featured two whole chromosome gains including Myc on chr.15 as published previously (4), and 7 deletions on chromosome 9, of which two were focal (smaller than 3 Mbp). One of these deletions contained the Keap1 gene, a tumor suppressor and master sensor of oxidative stress (17, 18).

We confirmed increased tolerance to MSB in Keap1–/– MEFs and using CRISPR/Cas9 in human PC3 and LNCaP, consistent with an increase in redox buffering capacity (Fig. 1F, fig. S3A–C). Next, we individually tested 100 cancer cell lines from our institute (Data S1) for sensitivity to MSB. We found that specifically those with known pre-existing loss of function KEAP1 mutations were most MSB resistant (Fig. 1G, H) and our query of the Broad’s DepMap 23Q2 dataset for gene essentiality (19) suggested that the top genetic dependency specific to the MSB resistant cell lines is the oncogenic transcription factor NRF2 (encoded by NFE2L2), which is suppressed by KEAP1 (fig. S3D–F). We confirmed this imputed connection to MSB using CRISPR-Cas9: human LNCaP and metastasis-derived PC3 cells become more MSB-tolerant after loss of KEAP1, but co-targeting of NRF2 ablates this effect, consistent with the epistatic genetic relationship (Fig. 1F, fig. S3C, G, H). A metastatic sub-clone harboring amplification of NRF2 (Nfe2l2 gene) was found by SNS analysis of a liver and lung metastasis in a non-responder animal (fig. S3I).

In sum, our experiment in a pre-clinical GEM model for metastatic prostate cancer revealed 1: a marked reduction of disease progression upon prolonged oral MSB administration, 2: that unlike with castration therapy in RapidCaP, lethal therapy resistance was rare with MSB. And genomics revealed 3: that therapy resistance may be controlled by the KEAP1-NRF2 antioxidant system, suggesting that cancer cells were under oxidative selection pressure. Since human PC cell lines rank among the most MSB-sensitive by lineage (Fig. 1I), and since the KEAP1-NRF2 pathway is rarely altered in human PC (14), we reasoned that there should be little a priori genetic resistance to MSB. Therefore, we sought to better understand how exactly MSB acts on cancer cells.

MSB triggers a thiol-dependent cell death modality

As in the prostate (Fig. 1D), MSB also caused glutathione (GSH) depletion in vitro (Fig. 2A, fig. S4A) and increased cytoplasmic reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels (Fig. 2B). We therefore tested cell-autonomous mechanisms underlying the MSB-effect. As suspected, cell viability inversely correlated with cell death, and this MSB-kill was effectively prevented by supplementing glutathione (GSH) or its precursor N-acetylcysteine (NAC), but not downstream cysteine metabolites (fig. S4B–C). Pre-incubation of the strongly cell-permeable GSH ethyl ester effectively desensitized cells to MSB, confirming that reductive protection happens inside the cell (fig. S4D). To quantify and compare protective versus sensitizing effects of modulators on MSB-kill, we calculated changes in normalized Areas Under the Curve (ΔAUCn, diagram in fig. S4E) and generated ΔAUCn heatmaps ordered by unsupervised hierarchical clustering. This approach allowed us to comprehensively and quantitatively summarize properties of MSB-kill. Thus, the kill curves of cysteine metabolite effects from fig. S4C are succinctly captured with a heatmap, as shown in Fig. 2C.

Figure 2. MSB triggers an oxidative cell death modality.

(A) GSH/GSSG ratios (n=3 biologically independent samples).

(B) Cytoplasmic ROS levels quantified by staining of CM-H2DCFDA followed by flow cytometry (n=3 biologically independent samples) in vehicle, NAC (0.5 mM), MSB (20 μM), or MSB+NAC treated Pten−/−; Trp53−/− MEFs, 4 hours post treatment. Data are mean ± s.d. P values were calculated using one-way ANOVA. **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001.

(C) Heatmap plotting ΔAUCn values depicts the extent of protection conferred by different cysteine metabolites from MSB-induced cell death. ΔAUCn > 0 or yellow color indicates that the respective cysteine metabolite protects from MSB induced cell death.

(D) A heatmap of the differential sensitivities for 40 compounds (rows) in the CRISPR-Cas9 derived isogenic PC3 cell lines (columns). ΔAUCn > 0 (or yellow) indicates increased resistance and ΔAUCn < 0 (or red) indicates increased sensitivity to a particular compound. ΔAUCn = 0 (or black) indicates no differential sensitivity between the isogenic cell lines. Erastin, RSL3, MSB, and H2O2 (indicated in blue) are grouped together through unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis.

(E) Top: modulatory profiling depicting the effect of 14 cell death modulators (columns) on MSB-induced cell death or other distinct cell death pathways induced by the indicated compounds (rows) in Pten−/−; Trp53−/− MEFs. ΔAUCn > 0 (or yellow color) indicates a protective effect of the modulator from the cell death pathway/compound, while ΔAUCn < 0 (or red color) indicates that the given modulator renders cells more sensitive to the cell death pathway/compound. ΔAUCn = 0 (or black color) indicates that the given modulator has no effect on the cytotoxic effect of the compound. Bottom: viability curves of Pten−/−; Trp53−/− MEFs treated with increasing concentrations of MSB for 24 hours, alone or in combination with GSH (0.5 mM, left) or ferrostatin-1 (2.5 μM, right) (n=3 biologically independent samples). Data are mean ± s.d.

(F) Left: modulatory profiling depicting the effect of 11 redox/ROS modulators (columns) on toxicity induced by MSB, other pro-oxidative, or non-oxidative compounds (rows) in Pten−/−; Trp53−/− MEFs. Right: viability curves of Pten−/−; Trp53−/− MEFs treated with increasing concentrations of erastin (top) or MSB (bottom) for 24 hours, alone or in combination with the lipophilic antioxidant vitamin E (100 μM) (n=3 biologically independent samples). Data are mean ± s.d.

(G) Production of lipid reactive oxygen species measured and quantified by staining of C11-BODIPY 6 hours post vehicle, NAC (0.5 mM), MSB (20 μM), NAC+MSB, erastin (0.3 μM) or erastin+NAC treatment in Pten−/−; Trp53−/− MEFs followed by flow cytometry (n=3 biologically independent samples). Data are mean ± s.d. P values were calculated using one-way ANOVA. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

(H) Transmission electron microscopy images of Pten−/−; Trp53−/− EpCaP cells (left, scale bar, 1 μm) or PC3 cells (right, scale bar, 2 μm) upon vehicle or MSB (30 μM) treatment.

(I) Quantification of the number of enlarged vesicles in EpCaP cells (left) or PC3 cells (right) treated with vehicle or MSB (30 μM). Data are mean ± s.d. P values were calculated using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test. ****P < 0.0001.

We next tested if MSB engages a discrete death pathway, because previous literature has implicated multiple redundant and also mutually exclusive cell death pathways (20–22). Several observations prompted us to first test if MSB acts through perturbation of the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC): the plant K-vitamer phylloquinone (VK1, fig. S4F) is essential in photosystem I of the chloroplast ETC (23). Ubiquinone, the mitochondrial electron carrier, is structurally related to the K-vitamer menaquinone (VK2, fig. S4F), and Pten/ Trp53 mutant PC cells are vulnerable to mitochondrial complex I inhibition (24–27). Yet we found that MSB-kill was not suppressed by yeast NDI1, a rescue transgene for mitochondrial complex I inhibitors (28), and MSB did not induce mitochondrial ROS (fig. S4G–I).

We next screened drugs with known cytotoxic mechanisms (fig. S5A) to determine if any of them share properties with MSB, using the CRISPR-derived isogenic KEAP1-mutant PC3 cells (Fig. 2D). Clustering analysis of this screen revealed that only three of 40 cytotoxic agents were similar to MSB: H2O2, as well as erastin and RSL3, two inducers of ferroptosis (29, 30). Additionally, we confirmed that the transcriptome changes upon MSB and erastin were strongly correlated (fig. S5B). Thus, to pharmacologically define the cell death pathway engaged by MSB more precisely, we used a process called modulatory profiling (31, 32). Three well-known modalities of cell death (apoptosis, programmed necrosis, and ferroptosis) were triggered and then blocked using their respective pathway specific modulators (see Data S2) for more information and expected mechanism). The resulting signatures were compared to that of MSB. As shown in Fig. 2E, pan-caspase inhibitors, z-VAD-fmk and qVD-oph, selectively protected from staurosporine induced apoptosis, but conferred no protection from MSB-kill. Bax–/–; Bak–/– MEFs remained MSB sensitive and we found no caspase activation, ATP-depletion, or autophagosome accumulation (fig. S5C–E). H2O2-mediated programmed necrosis was suppressed by replenishing NAD+ using alternative electron acceptors (AKB and EP) or the PARP inhibitor DPQ (9, 33) and by the intracellular calcium chelator BAPTA-AM. Erastin-induced ferroptosis was suppressed effectively by lipid ROS scavenger ferrostatin-1, the iron chelator desferoxamine (DFO), the lysosomal inhibitor bafilomycin A-1, or GSH (Fig. 2E). However, MSB-kill did not share any of the signatures with the above cell death modalities (Fig. 2E, bottom row). Glutathione was the only functional modulator that it shared with erastin. Together, these findings suggested that MSB killed cells through a specific type of oxidative stress that was unaffected by key modulators of ferroptosis, like ferrostatin-1. This was confirmed in human and mouse derived PC cells (fig. S5F).

We further tested how compartmentalized oxidative stress induction compared to MSB using phenformin (mitochondria), chloroquine (lysosomes), and doxorubicin (nucleus), and each was rescued by their known respective modulators (Fig. 2E). However, none of these suppressed MSB-kill, and vice versa, GSH only prevented MSB-kill, but not death by these other oxidants. This suggested that MSB can target a distinct thiol sensitive cell death pathway.

To better understand this thiol selective pathway, we tested the effects of 11 known redox modulators on MSB toxicity and on 4 other pro-oxidant compounds. As shown in Fig. 2F, staurosporine served as a negative control compound for the 11 modulators. Buthionine sulphoximine (BSO), an inhibitor of glutathione production generally sensitized cells to all five pro-oxidant compounds (erastin, MSB, Napabucasin-BBI608, 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene or DMNQ, H2O2) while DNCB (an inhibitor of thioredoxin reductase) was more MSB-specific. Conversely, the NADPH oxidase (NOX) inhibitor diphenyleneiodonium chloride (DPI) protected from 4 of the 5 pro-oxidants, albeit only weakly for MSB. Clustering analysis of the modulators revealed two critical differences between erastin and MSB. Most importantly Vitamin E (α-tocopherol), the specific inhibitor of lipid peroxidation, blocked ferroptosis by erastin, but it had no effect on MSB-kill (Fig. 2F heatmap and kill curves). Another lipophilic anti-oxidant, dibutylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), also selectively rescued from erastin, but not from MSB. This was in contrast to the thiol reducing agents NAC and β-mercaptoethanol (β-ME). The findings were confirmed in human and mouse derived PC cells (fig. S5F). Most notably, we found that in contrast to erastin, MSB did not cause lipid peroxidation, the defining feature of ferroptosis, as seen using flow cytometry analysis of the membrane lipid-ROS reporter BODIPY-C11 (Fig. 2G).

Finally, we used transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to analyze morphological features of MSB-induced cell death in human PC3- and RapidCaP-derived epithelial PC-cells (EpCaP). This revealed a significant (P < 0.0001) build-up of cytoplasmic vacuoles (Fig. 2H, I, fig. S5G); however, we did not note features of classical cell death pathways such as chromatin condensation (34).

Taken together, our analyses suggest that MSB kills through an oxidative cell death mechanism that shares biochemical and genetic features with ferroptosis, such as thiol depletion and KEAP1-dependence, but is independent of lipid peroxidation and morphologically distinct.

Genome-wide screens for functional regulators of MSB-kill

To distinguish events that are causal to MSB-kill from those that are merely correlated, we decided to 1: use CRISPR-Cas9 screens that nominate functionally relevant genes of MSB-kill, 2: perform the screens genome-wide so that underlying principles are more objectively revealed than by focused pathway screens, and 3: perform both positive and negative selection screens that approach the question from opposite sides.

A sensitization screen administered sub-lethal MSB to identify gene alterations that only become detrimental upon exposure to EC10 concentration (‘MSBlow’, negative selection). A resistance screen was also done to identify gene alterations that confer a survival advantage to a high concentration (EC50, ‘MSBhigh’ positive selection). Both screens compared the fitness effect of the gene perturbation plus vehicle with that of gene perturbation plus MSB. We used the Broad Institute’s Brunello whole-genome sgRNA library of 76,441 sgRNAs targeting 19,114 human coding genes (4 sgRNAs per gene) and 1000 control sgRNAs in the human metastasis-derived PC3 cell line.

Gene ontology analysis of the leading edge hits in the sensitizing screen (MSBlow) revealed genes mediating endocytosis (Fig. 3A, fig. S6A, Data S3): endophilin A3 (SH3GL3), which mediates Fast Endophilin Mediated Endocytosis (FEME (35), reviewed in (36)), as well as effectors of macropinocytosis and membrane ruffling (ELMO2, NCKAP1, ACTN2, KXD1). Gene ontology analysis of the MSBhigh positive selection screen showed enrichment specifically for late endosome associated genes (fig. S6B, C). These included RAB7-GTPase effectors of late endosomal trafficking (WDR91, FYCO1), maturation (RAB9A, SCARB2, ANXA8), and acidification (CLCN4, ATP13A2, Data S3), suggesting that their loss increased tolerance to MSB. Together, these data suggested that cell kill by MSB is functionally linked to endocytosis. More specifically, it suggested that inhibiting early steps of endocytosis and endosome formation could support MSB-kill, while inhibiting late endosomal progression, could suppress MSB-kill.

Figure 3. Genome-wide functional regulators of MSB-kill.

(A) Genome-wide CRISPR screens showing log2 fold change in abundance for genes upon MSB vs vehicle treatment in PC3-Cas9 cells. Gene ranked leading edge and lagging tail of the sensitizing screen at 15 μM MSB and of the resistance screen at 30 μM MSB are shown left and right, respectively (light blue circles in background). Inserts show endocytosis regulators (red and purple crosses) among the top 50 (dark blue circles). Core apoptosis and autophagy genes are marked as green and gray crosses, respectively. The role of VPS15 in generating early endosome identity as part of the VPS34 complex and its antagonist, MTM1, is drawn.

(B) Top: domain architecture of human VPS15 (encoded by PIK3R4). Locations of domain targeting sgRNAs are shown (arrowheads). Bottom: competition assay in indicated human PC cells stably expressing Cas9. Data are mean ± s.e.m, n=4 biologically independent samples.

(C) CRISPR design and results for validation of MTM1 gene targeting, shown as in (B).

(D) Left: confocal images of RapidCaP derived cells stably expressing tdTomatoFP (red), fixed after 4 hours of treatment with vehicle or MSB (15 μM). The cells were cultured in medium supplemented with fluorescein-dextran (3 kDa) for the duration of the treatment. Arrowheads point to dextran-positive vacuoles. Scale bar, 5 μm. Right: quantification of the number of dextran positive vacuoles per cell after 4 hours of treatment with vehicle (n=47 cells) or MSB (n=49 cells). Data are mean ± s.e.m. P values were calculated using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test. ****P < 0.0001.

(E) 17,199 genes ranked based on the correlation of their essentiality profile with that of PIK3R4 in 1095 cancer cell lines using CRISPR screening data from the Broad's DepMap database (23Q2).

(F) Summary of protein and gene constituents of VPS34 complex I and II. The complex I - II - exclusive genes are highlighted.

We noted that VPS15 was among the leading edge sensitizing CRISPR-hits (Fig. 3A, PIK3R4 gene). This stood out because VPS15 is a component of the endosomal class III PI 3-Kinase VPS34 complex (37). This complex defines the cell’s early endosomal compartment by marking it with the phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate, PI(3)P lipid (reviewed in (38)). This compartment is the central hub for endocytic routes as they are being funneled through it. Intriguingly, the MTM1 phosphatase was in the leading edge of the MSB resistance screen. This phosphatase is the direct antagonist of endosomal VPS34 kinase (39) (Fig. 3A) because it reverts PI(3)P back into PI. This immediately suggested that a single enzyme-regulated reaction step could be at the core of MSB-kill: production vs elimination of the lipid phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate (PI(3)P, see Fig. 3A, cartoon) (40). We therefore tested this hypothesis.

First, we validated these 2 screen hits using 2 independent domain focused sgRNAs in 3 human primary and metastatic PC cell lines. Competition assays confirmed that CRISPR-targeting of VPS15 (encoded by PIK3R4) confers sensitivity to MSB-kill compared to control guides. In contrast, targeting of MTM1 boosted tolerance to MSB (Fig. 3B, C and fig. S6D–J). Next, we validated that class III PI 3-Kinase VPS34 (PIK3C3 gene) function is essential in 3 prostate cancer cell lines using 2 independent sgRNAs targeting the kinase domain (fig. S7A, B). CRISPR-targeting of MTM1 rescued the cells (at least in part) from the deleterious effect of PIK3C3-ablation, in line with the enzymatic antagonism of this kinase-phosphatase pair (fig. S7C).

VPS34 kinase initiates autophagy through complex I, while complex II establishes the endosomal compartment (37). We found that MSB inhibited both autophagic flux (fig. S7D) and resulted in stalled endocytic uptake of extracellular dextran dye (Fig. 3D, fig. S7E–G) consistent with the TEM results (Fig. 2H). The genome wide CRISPR database on over 1000 cancer cell lines curated at the Broad Institute (DepMap, 23Q2) showed that the proteins specific to the endosomal VPS34 complex II are top correlates to VPS15 genome-wide: PIK3C3, followed by UVRAG and BECN1 (Fig. 3E). Importantly, UVRAG is cell essential and exclusive to the endocytosis complex (II). In contrast, the autophagy complex exclusive ATG14 is non-essential and did not correlate with VPS15 (Fig. 3E, F). This was consistent with our screen results: while gene alterations involving thiol metabolism, ROS detoxification, and oxidoreductase pathways were validated synergy hits with MSB (fig. S7H–J), hallmark genes of autophagy, apoptosis, and other prominent cell death pathways were not (Fig. 3A, Data S3).

Taken together, these results led us to hypothesize that the endosomal PI 3-Kinase VPS34 complex is a functional target of MSB-kill (see cartoon Fig. 3A), and that MSB controls class III PI 3-Kinase VPS34 indirectly or directly in a redox-sensitive manner.

Endosomal Class III PI 3-Kinase VPS34 is a functional target of menadione-kill

We first used time lapse microscopy to test the hypothesis that menadione kills cells by oxidative suppression of the endosomal VPS34-kinase complex. This allowed us to observe and quantify the steps that lead to cell death in greater detail. To this end, we generated epithelial non-migratory prostate cancer cells derived from a RapidCaP (Pten–/–;Trp53–/–) tumor (EpCaP cells) to enable cell-death imaging over a 24 hour period. The cells express tdTomatoFP representing cytosol and revealing obvious changes in the cytoplasm.

First, we recorded the cell death induced by the class III selective PI 3-Kinase VPS34 inhibitor, VPS34-IN1 (41). As shown in Fig. 4A and the associated Movie S1 and Movie S2 files, we noted 3 separate events upon VPS34-IN1 treatment: cytoplasmic vacuolization, steadily intensifying plasma membrane (PM) blebbing, and terminal burst of cells as seen by complete loss of the tdTomatoFP cytosolic marker. To statistically compare this sequence of events, onset of vacuolization and time to burst were charted as Kaplan-Meier plots. As shown (Fig. 4B), vehicle treatment caused few background burst and vacuolization events. Of note, vacuolization followed by cell death are indeed the phenotypes observed upon genetic VPS34 (Pik3c3-) loss as studied by others (42, 43) and us (44) in mouse primary fibroblasts (MEFs) using the Cre-loxP system. Adding the NAC reducing agent to the kinase inhibitor did not change the kinetics, the extent of vacuolization, or burst events (see Fig. 4B VPS34-IN1 + NAC, Movie S3 file and fig. S8A). Analysis of MSB (Fig. 4C–D and the associated Movie S4 and Movie S5 files) showed that it closely phenocopied the VPS34-IN1 induced vacuolization, blebbing, and burst sequence of events. But in strong contrast, reduction with NAC eliminated vacuolization and PM bursts to background levels (Fig. 4D MSB + NAC, fig. S8A, Movies S4, S5). Next we tested if menadione inhibits class III PI 3-Kinase VPS34 function of generating the PI(3)P marker on endosomes. The cells imaged in Fig. 4A–D are also transgenic for GFP-2xFYVE, the commonly used reporter (45) for PI(3)P, allowing us to ask if and when PI(3)P was affected. As expected (Fig. 4E), the typical GFP-2xFYVE punctate signal was sharply reduced by the kinase inhibitor VPS34-IN1, indicating loss of PI(3)P positive vesicles. MSB had a similar, albeit slower effect, also before overt vacuolization, as seen in the imaging and quantification (Fig. 4E, F, fig. S8B, and associated Movies S6–S9). The addition of NAC to MSB eliminated the effect on GFP-2xFYVE puncta, making it indistinguishable from vehicle treatment (fig. S8B). To test if the cell death phenotypes were generalizable beyond the PTEN/ TP53-mutant background and beyond prostate cancer, we went through our results from MSB-kill in 100 cancer cell lines (Fig. 1H, I) and used 5 sensitive cell types from unrelated cancers. This showed that burst was also preceded by vacuolization, and that the process was thwarted by NAC (fig. S8C). Note that xFP or other cytosol markers are needed to report integrity of cells prior to PM burst at the time of fixation/ permeabilization. Quantitative immunofluorescence in the PC3 cells validated that MSB, like VPS34-IN1, reduced PI(3)P-positive vesicles at both the MSBlow and the MSBhigh screen concentrations, producing a diffuse cytoplasmic GFP-2XFYVE signal (Fig. 4G, fig. S9A). CRISPR-targeting of VPS34 kinase phenocopied these effects of MSB and VPS34-IN1 (Fig. 4G, fig. S9A).

Figure 4. VPS34 is a functional target of menadione.

(A) Cell death analysis using EC100 dose of VPS34-IN1. Still images from time lapse (20 minute interval) recording of treated EpCaP cells at indicated time points. Arrows point to cell blebbing events in the field of view. Scale bar, 10 μm, inset box width, 20 μm. Please see associated Movies S1–S3.

(B) Kaplan-Meier event analysis for VPS34-IN1 (40 μM) (n=177 cells), VPS34-IN1 (40 μM) + NAC (500 μM) (n=84 cells), and vehicle (n=74 cells), scoring for 1) onset of vacuolization, as defined by time of appearance of cytoplasmic vesicles ≥ 3 μm diameter and 2) burst time as scored by between-frame depletion of cytosolic tdTomato, indicating PM rupture (please see associated Movies S1–S3). P values were calculated using Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test: VPS34-IN1 vs VPS34-IN1+NAC (vacuolization: P = 0.5912, burst: P = 0.3036); VPS34-IN1 vs vehicle (vacuolization: P < 0.0001, burst: P < 0.0001).

(C) Cell death analysis recorded and labeled as in (A), but using EC100 dose of MSB. Scale bar, 10 μm, inset box width, 20 μm. Please see associated Movies S4 and S5.

(D) Kaplan-Meier event analysis for MSB (30 μM) (n=127 cells), MSB (30 μM) + NAC (500 μM) (n=200 cells), scoring for 1) onset of vacuolization and 2) burst time, as described in (B). P values were calculated using Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test: MSB vs MSB+NAC (vacuolization: P < 0.0001, burst: P < 0.0001); MSB vs vehicle (vacuolization: P < 0.0001, burst: P < 0.0001).

(E) Still images of the PI(3)P - early endosome marker GFP-2xFYVE in time lapse recordings from (A) and (C) with indicated treatments and times. Scale bar, 10 μm, inset box width, 20 μm. Please see associated Movies S6–S9.

(F) Quantification of 2XGFP-FYVE puncta from time lapse experiments shown in (A-E) for vehicle, MSB and VPS34-IN1 treatment over time. Note that the marked reduction in both treatment conditions occurs prior to cell burst (before 480 minutes), as determined in (B) and (D).

(G) Number of PI(3)P positive vesicles in PC3-Cas9 cells fixed after 4 hours of treatment with indicated small molecules or expression of indicated sgRNAs (vehicle n=40, MSB-low, 15 μM, n=15, MSB-high, 25 μM, n=51, VPS34-IN1, 10 μM, n=14, sgROSA n=21, sgPIK3C3 #5 n=13, sgPIK3C3 #8 n=22). Data are mean ± s.e.m. P values were calculated using one-way ANOVA. ns, not significant, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001.

(H) Cartoon for RAB5-mediated recruitment of VPS34 complex II to an endosomal membrane and its suppression by the kinase inhibitor VPS34-IN1 and pro-oxidant MSB.

(I) Left top: confocal images of EpCaP cells stably expressing tdTomato and transiently expressing RAB5-GFP after 4 hours of treatment with vehicle or MSB (15 μM). Scale bar, 5 μm. Left bottom: quantification of mean RAB5-GFP positive vesicle volume per cell after vehicle (n=14) or MSB (15 μM, n=12) treatment. Data are mean ± s.e.m. P values were calculated using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test. ****P < 0.0001. Right: quantification of RAB5-mRFP positive vacuoles per cell in VPS34 (Pik3c3loxP/loxP) conditional KO-MEF after vehicle (n=33), MSB (20 μM, n=23), VPS34-IN1 (10 μM, n=13) treatment, control (n=22) or Cre-mediated kinase ablation (n=16). Data are mean ± s.d. P values were calculated using one-way ANOVA. ns, not significant, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

The small GTPase RAB5 recruits and activates VPS34 complex II on early endosomes (46) (see cartoon, Fig. 4H, and (37, 38) for reviews), so we next tested if MSB interferes with the positioning of RAB5a. However, we found abundant RAB5a decoration of MSB-induced vacuoles indistinguishable from pharmacological inhibition (VPS34-IN1) and genetic targeting of PI 3-Kinase VPS34 (PIK3C3) in human and mouse cells using CRISPR-Cas9 and Cre-loxP, respectively (Fig. 4I, fig. S9B, C). We next compared MSB effects with PIKFYVE inhibition. PIKFYVE converts PI(3)P on early endosomes to PI(3,5)P2 for endo-lysosomal progression. PIKFYVE inhibition results in large vacuoles marked by late endosomal protein lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1). In contrast, MSB or VPS34-IN1 treated cells presented LAMP1-negative vacuoles, as shown in fig. S10A. Class II PI 3-Kinases generate PI(3)P at the plasma membrane. Pharmacological targeting and screen analysis indicated that they offer no major protection from MSB-kill consistent with dominant PI(3)P production by the class III kinase VPS34 (38). At the same time, MSB did not perturb PIK3C2A function (fig. S10B–E).

Together our results thus far supported two major conclusions: MSB can kill cells by indirectly or directly antagonizing endosomal PI 3-Kinase/ VPS34, and this regulation is under redox control. Mechanistically, MSB-induced stalling of endocytosed vesicles is likely because two major downstream processing pathways depend on endosomal PI(3)P deposition onto RAB5 positive vesicles for coincident detection: recycling to the PM requires PI(3)P on vesicles that is to be converted to PI(4)P, whereas progression into the endo-lysosomal degradative pathway requires first recognition, then conversion of PI(3)P into PI(3,5)P2 (reviewed in (38)).

Thus, our data hinted at the existence of a redox checkpoint at the stage of endosomal identification.

MSB oxidizes cysteines required for endosomal VPS34 function and survival

To test if MSB oxidizes PI 3-Kinase VPS34, we immunoprecipitated the kinase from MSB- or vehicle-treated cells (of note, MSB did not affect VPS34 levels, as seen in fig. S10F). We then subjected it to a sequential alkylation and reduction process that reveals cysteine modification states by mass spectrometry (fig. S11A). As shown in Fig. 5A and fig. S11B–D, we recovered 9 of a total 11 VPS34 cysteines and found that in peptide 1 (Cys54 / Cys61) and peptide 2 (Cys226), MSB caused a depletion in free thiol and a concomitant increase in reversible oxidation. Catalytic domain cysteines and negative control peptides were among the unaffected. Peptide 1 (Cys54 / Cys61) maps to the C2 domain, which controls formation and function of the hetero-tetrameric VPS34 complex (47) and has been proposed as a hub for post-translational control of VPS34 (48). We confirmed using recombinant-purified VPS34 complexes in ADP Glo kinase assays (49, 50), that the activities of full-length VPS34, VPS34 Complex I (CI) and VPS34 Complex II (CII) were all inhibited by MSB (fig. S11E).

Figure 5. Dietary menadione extends lifespan in a myotubular myopathy model.

(A) Top: Domain architecture of human class III PI 3-Kinase VPS34. Bottom: Heatmap representation of percent depletion in free thiol status of VPS34 cysteines in MSB-treated cells compared to vehicle.

(B) Left: Log2 fold change in relative abundance of GFP-positive Pik3c3Δ/Δ cells, expressing the indicated VPS34 mutants, 18 days post Cre infection (n=3 each). Right: competition-based proliferation assay in Cre and GFP-expressing Pik3c3loxP/loxP MEFs expressing the indicated VPS34 mutants. Percent GFP-positive cells, normalized to day 6 post Cre.GFP infection, are measured over time. Data are mean ± s.e.m. P values were calculated using one-way ANOVA. ns, not significant, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001.

(C) Confocal images of Pik3c3loxP/loxP MEFs stably expressing RAB5-mRFP (gray) and the indicated VPS34 mutants, 10 days post adeno-empty or Cre infection. Arrowheads point to RAB5 coated endocytic vacuoles (“v”). “nl” indicates normal RAB5-positive early endocytic vesicles. Scale bar, 5 μm.

(D) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for Mtm1 WT and KO male mice, enrolled on the day of weaning to receive regular drinking water or MSB dissolved in the drinking water (Mtm1 WT, water n=16; Mtm1 WT, MSB n=14; Mtm1 KO, water n=16; Mtm1 KO, MSB n=17). P value was calculated by Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. ****P < 0.0001.

(E) Body mass of Mtm1 WT and KO male mice from trial shown in (D): Mtm1 WT, water n=15; Mtm1 WT, MSB n=13; Mtm1 KO, water n=16; Mtm1 KO, MSB n=17. P value was calculated using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test. **P < 0.01.

(F) Photographs of untreated and treated Mtm1 WT and KO male littermates from 2 litters (36 days old), showing observed differences in size between genotypes and treatment groups.

(G) Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin staining in TA muscle sections of Mtm1 WT and KO mice from the indicated trial arms. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(H) Left: Minimum Feret diameter (MinFeret) distribution of TA fibers in Mtm1 WT and KO male mice from the indicated treatment arms. Middle Panels: Frequency of TA fibers with MinFeret diameter lower than 35 μm and higher than 35 μm, respectively. Right panels: Fraction of fibers with mislocalized nuclei and abnormal SDH staining. P values were calculated using one-way ANOVA. ns, not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001

(I) Representative images of SDH activity in TA muscle sections of Mtm1 WT and KO mice from the indicated trial arms. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(J) Representative images depicting TA ultrastructure by TEM, from untreated or MSB treated Mtm1 WT and KO mice. Magnification of a triad is shown in TA of Mtm1 WT mice. “mito” or “mi” indicates mitochondria. Scale bar, 1 μm.

We then tested if these VPS34 candidate cysteines could indeed control cell viability. To this end, we performed gene knockout - plasmid rescue experiments using the VPS34 (Pik3c3loxP/loxP) conditional knockout MEFs. These were stably transduced with the candidate VPS34-mutants carrying cysteine to alanine or cysteine to aspartate substitutions. The latter served as bona fide oxido-mimetic missense mutations. Upon infection with Cre.GFP lentivirus, the endogenous VPS34 was lost and the fitness of the VPS34-mutant rescue plasmids was scored as the fraction of GFP-positive cells in each condition. Figure 5B (empty vector) shows that recombination of the endogenous VPS34 without replacement strongly depleted these cells (see also fig. S11F). In contrast, the VPS34 WT plasmid effectively rescued the Pik3c3Δ/Δ cells. Importantly, all mutants of Cys54 and Cys61 were unable to rescue cells. This suggested that 1: these two cysteines are essential for VPS34 function, and 2: that their oxidation could inactivate the kinase complex. In contrast, the Cys226 mutants remained functional.

Finally, we assessed if mutation of these cysteines recapitulate inactivation of endosomal VPS34 complex II, by analyzing the cellular phenotypes. As shown in Figure 5C (and fig. S12A), the Cys 54 and Cys61 mutants showed strong RAB5-positive vacuole formation (compare to fig. S9). Thus, the mutants gave rise to the hallmark of MSB kill, without MSB.

Collectively, our analysis showed that Cys54 and Cys61, which can be reversibly oxidized by MSB, are required for endosomal VPS34 function. Therefore, they are strong candidates for an evolutionarily conserved redox switch on VPS34 (fig. S12B) that controls the oxidative cell death caused by MSB.

Dietary menadione extends life span in a fatal disease driven by PI 3-Kinase VPS34

Since MSB antagonizes PI 3-Kinase VPS34, we next tested if it can effectively suppress a fatal human disease syndrome that involves this kinase, when administered orally as we did in the prostate cancer trial.

X-linked myotubular myopathy (XLMTM, OMIM #310400) is a heritable fatal disease in boys caused by mutation of the MTM1 gene on chromosome X. Since MTM1 phosphatase is the direct antagonist of PI 3-Kinase VPS34 (see Fig. 3A), these patients suffer from unopposed PI(3)P production. This has been successfully tested in patient-derived cells (51).

The Mtm1-knockout mice fully recapitulate the most severe XLMTM phenotype, lethality in infant boys (52, 53). As shown (Fig. 5D), Mtm1-deficient male mice (Mtm1KO/Y, aka Mtm1-KO) succumb to the disease at a median one month of age due to extensive failure of muscle buildup, as described (52). In contrast, giving MSB in drinking water significantly (P < 0.0001) expanded overall survival to a median 62 days (Fig. 5D, see also the separate second trial below). Importantly, MSB was administered as in the cancer trial (Fig. 1): in drinking water, and at the same concentration. As previously (54), enrollment and treatment of pups was started after weaning at 21 days of age (fig. S13A), when KO males already manifested disease symptoms (fig. S13B, WT vs KO). We confirmed that treatment decreased GSH/GSSG ratios in Mtm1KO/Y mice (fig. S13A). Body weight analysis of the entire trial (Fig. 5E) showed significantly (P < 0.0001) more weight gain in MSB-treated Mtm1KO/Y mice compared to this genotype on water, in spite of indistinguishable weights at enrollment day 21 (Fig. 5E, right panel, KOwater vs. KOMSB). In agreement, body images of 3 sets of littermates on the 4 treatment arms indicated that MSB-treated KO-animals were larger than their KO-littermates lacking MSB treatment (Fig. 5F and fig. S13C).

Histological analysis of untreated Mtm1KO/Y muscles showed the previously reported myofiber hypotrophy and organelle mislocalization (52, 55) (Fig. 5G), and the shift toward smaller fiber peak diameters compared to WT muscles (Fig. 5H). Upon MSB treatment, muscle fiber size was increased in Mtm1KO/Y mice compared to the untreated knockout animals, which exhibited a higher fiber number with a small diameter (< 35 μm) and a lower number of fibers with a large diameter (> 35 μm, Fig. 5H). The hallmark mispositioning of nuclei and mitochondria (52) was observed in 4% of Mtm1KO/Y fibers and decreased to 2.4% in the MSB-treated knockout mice (Fig. 5H). Abnormal cell-peripheral mitochondria (revealed by SDH and NADH staining, Fig. 5H, I, fig. S13D) was seen in 94% of untreated and decreased to 27% in MSB-treated Mtm1KO/Y mice. Thus, MSB treatment of Mtm1KO/Y mice improved several histopathological defects in muscle fiber. Muscle ultrastructure analysis by TEM confirmed Mtm1 knockout phenotypes (Fig. 5J): disorganized sarcomeres with misaligned Z-disks, undetectable M-line and absence of mitochondria between myofibers. Although T-tubules are observed in untreated Mtm1KO/Y mice, triads were not. In MSB-treated Mtm1KO/Y mice, sarcomere alignment was ameliorated and mitochondria localized between myofibers, similar to WT muscle. T-tubules were also visible but triads were not restored.

Overall, muscle histology and myofiber ultrastructure were improved following MSB administration in Mtm1KO/Y mice.

Open field cage monitoring (fig. S13E, F) revealed that MSB improved active time, distance traveled and median speed, while the number of rears in Mtm1KO/Y mice was not significantly different from WT only upon MSB treatment. As expected, there was no significant difference in exploratory pattern (fig. S13G). To study onset of clinical parameters in greater detail, we carried out a second trial (fig. S13H) and found that MSB treatment significantly delayed the onset of hindlimb paralysis (P < 0.001) (fig. S13I). Finally, we used the clinical score method to assess disease progression (54), and found a significant (P < 0.01) improvement for the Mtm1KO/Y cohort treated with MSB, compared to water (fig. S13J).

Taken together, our data suggested that MSB-mediated targeting of PI 3-Kinase VPS34 can be used towards effective suppression of this debilitating genetic disease in mice.

Discussion

Ample evidence exists for the tumor and metastasis promoting role of dietary antioxidants (2, 3, 56–58). But it has remained ill-defined if vice versa, pro-oxidants can suppress cancer. We have found that dietary administration of the pro-oxidant vitamin K precursor menadione sodium bisulfite (MSB) suppresses prostate cancer progression. We also show that menadione triggers an oxidative cell death by antagonizing the primordial class III PI 3-Kinase VPS34, thus blocking endosomal sorting. This suggests a therapeutic opportunity, given the evidence of prostate cancer promotion by dietary antioxidants (2, 3).

There is an emerging picture of how various oxidative and ROS inducing interventions affect core cellular processes selectively, instead of broadly. Compartments and localization play a central role in specificity: membrane lipids are the sites for ferroptosis induction, mitochondria for electron transport chain inhibitors, and irradiation or chemotherapy can oxidize DNA in the cell nucleus (9, 29, 59–68).

Here, we discovered a type of cell death controlled by oxidative depletion of PI(3)P, the token of endosomal identity. This suggests that endosomal progression is under a redox checkpoint. This checkpoint monitors the redox state of key cysteines on endosomal PI 3-Kinase VPS34, licensing it to generate the early endosomal (EE) compartment by marking it with PI(3)P.

We propose to name this new modality triaptosis, for cell death by depletion of 3-(Greek: Tría)-phosphoinositide. Upstream, early endosomes (EEs) are the fusion hub for the multiple incoming clathrin-dependent and -independent endocytic vesicles. Downstream, they are the dispatching hub that guides proteins, cargo, and membranes towards either the late endo-lysosomal compartments, or back towards the cell surface (38) by virtue of the coincident detection of RAB5 and PI(3)P. In triaptosis, loss of PI(3)P effectively de-identifies endosomes, thus disabling their downstream sorting, while incoming vesicles continue to fuse into these bloating structures.

This prompts the general question why an ancestral protein complex like Class III PI-3Kinase VPS34 and a cell essential process like endocytosis evolved to be under redox control. We speculate that iron metabolism may represent a prototypical case for this checkpoint. Iron is an essential nutrient that is taken up by receptor mediated endocytosis and released through the endolysosomal system. Iron is then effectively liganded and stored, but there also exists an unliganded ‘labile’ iron pool that is toxic to cells because it generates hydroxyl radicals from H2O2 via the Fenton reaction (67). Hence, it makes sense for cells to limit iron uptake/ endocytosis when under oxidative stress. Indeed, suppression of iron/ transferrin receptor uptake, recycling, and also lysosomal processing have been observed after menadione treatment several decades ago (69), entirely consistent with our finding of PI 3-Kinase VPS34 suppression by this oxidant.

Clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME) is the major route of nutrient uptake and PM receptor regulation. Clathrin-independent endocytosis (CIE) routes also exist and they are key in cancer: mutant Ras boosts macropinocytosis through class I PI 3-Kinase (70, 71). After PTEN loss, unchecked action of class I PI 3-Kinase promotes macropinocytosis and also fast endophilin mediated endocytosis (FEME), another type of CIE. Indeed, endophilin and drivers of macropinocytosis were among the top hits in the sensitizing screen (Fig. 3A), consistent with the ability of CIE pathways to support fitness of the prostate cancer cells under low-dose MSB oxidative stress. This is because by triggering the proposed endosomal redox checkpoint, PI(3)P levels drop, and VPS34-independent sources of PI(3)P become critical. This requires an elaborate and inefficient enzymatic detour that depends on class I and class II PI 3-Kinases and a multitude of PIP metabolizing enzymes (38, 72). Thus, it is entirely expected that these alternatives cannot prevent triaptosis upon class III PI 3-Kinase VPS34 inactivation, because 70%-80% of the cell’s PI(3)P pool is produced in a single step by this enzyme (38, 73, 74). In stark contrast however, thiol reducing power, completely rescued triaptosis, suggesting that cells with sufficient reducing reserves can overcome this stress. This may be the basis for our observed therapeutic window.

The generation of mouse models for XLMTM and related centronuclear myopathy syndromes has led to several successful pre-clinical trials and this has spawned a number of clinical trials to help affected patients (75). Problems associated with human gene therapy (76) have unfortunately stymied the translation of highly successful gene therapy in mice and dogs that reconstituted the Mtm1 gene. At the same time, new human trials have been started based on the unexpected pre-clinical success with drug repurposing: it was shown that tamoxifen can be used to strongly ameliorate the disease in Mtm1-KO mice (54, 77). Moreover, it has been shown that loss of class II PI 3-Kinase (Pik3c2b) reverses the lethal Mtm1-KO phenotype, while the pan-PI 3-Kinase inhibitor wortmannin extends survival in these mice (51, 78–80). It will be important to see how progress with the therapeutic windows of PI 3-Kinase class II and class III inhibitors impact the design of myotubular myopathy trials. While key points for clinical translation remain to be tested (dose-response, drug accumulation in muscle, force generation), it is encouraging that the improvements in life span and activity may be linked to improvements in muscle histology and myofiber ultrastructure. Thus, our pre-clinical results based on dietary menadione have the potential to expand the toolbox for therapy of XLMTM and perhaps even other centronuclear myopathies, more broadly.

Taken together, we suggest that our discovery of cell death by triaptosis and the opportunity for suppressing class III PI 3-Kinase VPS34 with the pro-vitamin menadione may offer much needed lines of attack in multiple human disease settings.

Materials and Methods Summary

Generation of RapidCaP mice

PtenloxP/loxP; Trp53loxP/loxP transgenic mice were used in this study. All protocols for mouse experiments were in accordance with institutional guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). PtenloxP/loxP; Trp53loxP/loxP transgenic mice were generated by crossing PtenloxP/loxP mice with Trp53loxP/loxP mice. Eight-week-old PtenloxP/loxP; Trp53loxP/loxP transgenic male mice were used for RapidCaP surgery. The detailed method has been described previously (4, 5, 81). After exposure to anesthesia (isoflurane, 2%), the lower half of the abdomen was shaved and the mouse was placed in a sterile surgical hood. The mouse was constantly exposed to isoflurane via a nose cone for the entire duration of the 10-minute surgery. The shaved region was cleaned with betadine, followed by ethanol thrice. A 0.5 inch incision in both the skin and peritoneum was made along the lower abdomen, to the right of the midline, to allow the right anterior prostate to be exposed. The right anterior prostate is removed from the body and placed on a sterile drape. 20 μl of concentrated Luc.Cre virus (Addgene plasmid #20905, 2.5x107 TU/ml), purchased from the University of Iowa’s Viral Vector Core, was injected into the right anterior prostate. The incision was then sutured with absorbable sutures and the skin stapled shut using 2 to 3 stainless steel EZ Clip wound closures. Animals were observed for complete recovery from anesthesia and warmed under a heating lamp to regain the ability to maintain sternal recumbence and given DietGel.

Generation of MTM mice

MTM heterozygous female mice (Mtm1+/−), containing a targeted deletion in exon 4 of one Mtm1 (52) were crossed with Mtm1+/Y males and were maintained on a C57BL/6J background for several generations, following confirmation of the genetic background using externally validated genetic monitoring SNP panels (MiniMUGA array, Transnetyx). For genotyping, genomic DNA was isolated via tail clips and subjected to PCR analysis using the following primers -

Forward: 5’-AGCACATGGGAGGTTGAG-3’; Reverse: 5’-GGCTTTAACCAAGGATTCACA-3’

The presence of WT and Mtm1δ4 alleles result in a 0.9 kb and 0.2 kb DNA fragment respectively.

Animal trials

For trials on RapidCaP animals, mice with sustained disease as determined by 4 weeks of bioluminescence imaging were randomized and assigned to 3 cohorts receiving water control (n=7), a dose of 0.15 mg/ml of MSB (Sigma-Aldrich, M5750) (n=7), or a combination of 0.15 mg/ml MSB with 15 mg/ml Vitamin C (Sigma-Aldrich, A7631) (n=8). The compounds were dissolved fresh daily in autoclaved water and provided to the mice ad libitum. Drug consumption was recorded daily (ml) to ensure consistent dosing between and within cohorts. Mice were monitored weekly for weight loss as well as disease progression via bioluminescence imaging. At the end of the 18-week trial period, mice were humanely euthanized and the prostates were excised and flash frozen for mass spectrometry analysis. For bioluminescence imaging, mice were intraperitoneally (IP) injected with D-Luciferin (GoldBio, 115144–35-9) (50 mg/kg) and analyzed using an IVIS Spectrum system (Caliper Life Sciences) ten minutes after IP injection. For signal quantification Living Image was used. The two animals with Δendpoints > 3rd quartile + 1.5 x inter-quartile range of their respective cohort: MSB#8=1312% > 118.5; MSB & VC#8=1379% > 293.0 were defined as statistical outliers.

To determine effects on coagulation, naive mice were dosed with increasing concentrations of MSB (0.15 mg/ml to 0.75 mg/ml). The treatment was provided ad libitum and made fresh daily. Blood coagulation was tested biweekly using the Roche CoaguChek XS device. Mice were restrained and a small tail vein puncture was performed. Within 15 seconds of the tail vein puncture, 50 μl of blood was dripped on to the CoaguChek test strip and the reading was recorded.

Vitamin C levels were determined and showed no increase in normal liver (MSB & VC: 2.05 nmol/mg S.D. = 0.65 nmol/mg vs. water: 2.46 nmol/mg, S.D. = 0.02 nmol/mg) and prostate (MSB & VC:1.78 nmol/mg S.D. = 0.29 nmol/mg vs. water: 1.64 nmol/mg, S.D. = 0.14 nmol/mg) of 3 trial animals each using the Ascorbic Acid Assay Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, MAK074–1KT).

For transplantation experiments in Nu/J male mice (JAX stock #002019), 100,000 RapidCaP derived Pten−/−; Trp53−/− EpCaP cells were mixed with an equal volume of Matrigel and then subcutaneously injected. The tumors were allowed to engraft and then (10 days post injection), mice were enrolled on a randomized basis to be treated with PBS or MSB (50 mg/kg). The treatment was delivered via IP injections on a daily basis. At the end of one week, mice were humanely euthanized and the prostates were excised and flash frozen for mass spectrometry analysis. For transplantation experiments in C57BL/6 male mice, 250,000 RapidCaP derived Pten−/−; Trp53−/− EpCaP cells were mixed with an equal volume of Matrigel and then orthotopically injected into the right anterior prostate using the surgical procedure for RapidCaP generation as described earlier. The tumors were allowed to engraft and then (10 days post injection), mice were enrolled on a randomized basis to receive regular drinking water or 0.15 mg/ml of MSB dissolved in the drinking water. The compounds were dissolved fresh in autoclaved water, thrice a week, and provided to the mice ad libitum. At the end of ten days, mice were humanely euthanized and the prostates were excised and flash frozen for RNA extraction.

For the MTM trials, Mtm1 WT (Mtm1WT/Y or Mtm1+/Y) and Mtm1 KO (Mtm1KO/Y) male mice were weaned on post-natal day 21 and randomly enrolled to receive regular drinking water or 0.15 mg/ml of MSB dissolved in the drinking water. The compounds were dissolved fresh in autoclaved water, thrice a week, and provided to the mice ad libitum. Mtm1KO/Y animals were kept on the respective treatments until death as the endpoint. Animal weights were recorded on days 21, 24, 26, and 28, and then on a weekly basis.

For phenotypic assessment of mouse motor functions, we analyzed activity of the animals using an open field test. Mouse mobility was tested in a 40 cm (L) × 22 cm (W) × 25 cm (H) black acrylic box. A camera was mounted above the box and connected to a PC via USB2.0 cable for video recording. The axis of the camera was perpendicular to the box ground, so that the videos showed mouse movements on the horizontal plane. On the test day, mice in their home cages were transferred to the test room at least one hour before the test started. Each mouse was gently loaded to the center of box ground by hand and then allowed to explore the box freely for 3 minutes while video recording was on. After that, the mouse was returned to its home cage and home room. The box was cleaned using 70% alcohol and paper towels between consecutive animals. Tests were done on 3 days post enrollment to a treatment condition.

The first 3 minutes after the mouse was loaded into the box were analyzed from video files. The (x, y) coordinates of mouse location on each frame of video recordings were determined using the python package ezTrack (82). The resulting coordinates were then transformed to derive displacement, di = [(xi − xi−1)2 + (yi − yi−1)2]0.5 and mobility vi = (di) × (frame rate) for the ith frame. A separate video clip of a mouse sitting at a fixed location without overt displacement by eye was used to set the threshold of movement for all other mice. Any frame with displacement above that threshold was considered as an active frame. Proportion of active time was calculated as percentage of active frames to all frames in 3 minutes. Total displacement was the sum of displacement in the active time.

Electron microscopy: TA muscles were fixed by immersion in 2.5% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH=7.4), then washed in cacodylate buffer for 30 minutes. Muscles were postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer for 1 hour at 4°C, and dehydrated through graded alcohol (50, 70, 90, and 100%) and propylene oxide for 30 minutes each. The samples were embedded in Epon 812 before semithin sections were cut at 2 μm. Ultrathin sections were cut at 70 nm (Leica Ultracut UCT) and contrasted with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Sections were observed at 70kv with a Morgagni 268D electron microscope (FEI Electron Optics, Eindhoven, the Netherlands). Images were captured digitally by Mega View III camera (Soft Imaging System). The number of T-tubule per sarcomere and T-tubule direction were measured manually.

Histology: 8 μm thick transversal cryosections of TA muscles were collected on glass slides and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (HE) or succinate dehydrogenase (SDH). Light microscopic images were acquired using a Nanozoomer 2HT slide scanner (Hamamatsu Photonics). Myofiber size was measured by the Cellpose segmentation algorithm on HE sections (83). Images were analyzed using FIJI analysis software. Myofiber MinFeret diameter (μm) and nuclei mislocalization analyses were performed on HE images. SDH images were used for analysis of mitochondria mispositioning. Fibers with abnormal SDH staining and nuclei positioning were counted manually using the cell counter plugin in FIJI analysis software. Myofiber size, abnormal SDH staining and nuclei mislocalization were determined from fibers of the whole muscle section.

Single nucleus processing for whole genome sequencing

For single cell genomics, we used the Single Nucleus Sequencing (SNS) approach. Animals were euthanized via CO2 exposure, tissues of interest were harvested and imaged on the Xenogen/ IVIS after application of luciferin ex vivo. Regions with BLI signal were then dissected and flash frozen. To isolate cells from the bone, femur was flushed with PBS, collected and BLI imaged to confirm presence of mutant cells followed by staining with CD45 antibody and sorting of the CD45-negative population by FACS. Nuclei were isolated for SNS from frozen and FACS sorted samples using the previously published protocol (84). Samples were lysed in the NST-DAPI buffer (15): [800 ml of NST (146 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris base at pH 7.8, 1 mM CaCl2, 21 mM MgCl2, 0.05% BSA, 0.2% NP-40)], 200 ml of 106 mM MgCl2, 10 ml of 500 mM EDTA at pH 8.0, and 10 mg of DAPI (Cell Signaling Technology, 4083S). Nuclei were prepared by gently centrifuging the cell lysis solution at 1,000 rpm for 5 minutes to pellet them followed by removal of supernatant and addition of 1 ml of NST-DAPI buffer to the cell pellet. Suspensions of nuclei were filtered through a 25 mm cell strainer prior to flow sorting. Single nuclei were sorted by FACS using the BD Biosystems SORP flow cytometer and single nuclei were deposited into individual wells of a 96-well plate.

For whole-genome amplification (WGA) and Illumina library construction, the Seqplex DNA amplification kit (Sigma-Aldrich, SEQXE-50RXN) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Before library preparation the Seqplex primers were first removed enzymatically. 1 μg of WGA product was then end-repaired, A-tailed and ligated to TruSeq adapters (illumina). The ligated DNA was purified using AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter) then pooled, amplified and quantified for sequencing using a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent). The pools were sequenced on the Illumina NextSeq 500 instrument using single read 76 bp.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge all the members of the Trotman Lab, Drs. Xuejun Jiang, Volker Haucke, Silke Gillessen-Sommer, Andrei Chabes, Claudia Tonelli, Tobiloba Oni, Kin On and Tom Miller and Stephen Coutts for valuable advice and critical discussion of the data and manuscript. We thank Drs. Gina DeNicola, Viraj Sanghvi, Nicholas Tonks, Masayuki Yamamoto and Wei Xing Zong for reagents, and Pamela Moody and Cassandra Viola for help with FACS procedures, the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Animal Resources team, Dr. Rachel Rubino, Lisa Bianco, Jodi Coblentz, and Michael Cahn for help with animal work; Amy Brady and Julie Cheong for supplying validated cancer cell lines from CSHL’s tissue culture facility and Dorothy Tsang for help with the article. We thank Dr. Qing Gao, Aigoul Nourjanova, Denise Hoppe-Cahn, Kristin Milicich, Logan Stecher and Kayla Anne-Javier for help with histologic procedures and analysis.

Funding

This work was directly supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) 1R01CA275128 (L.C.T.) and NCI 5R01CA137050 (L.C.T.), the Pershing Square Sohn Cancer Research Alliance (L.C.T.), funds from IC-MedTech (L.C.T.), the Department of Defense grant DoD W81XWH-22–10-358 (M.R.D.), the Simons Foundation, Life Sciences Founders Directed Giving-Research award number 519054 (M.W)., a research collaboration grant between AstraZeneca UK Limited and the Medical Research Council, reference BSF2–10 (R.L.W.),the Mark Foundation for Cancer Research 20–028-EDV (T.J.) and NCI R01CA193256 (J.W.L.). D.A.T. is a distinguished scholar and Director of the Lustgarten Foundation–designated Laboratory of Pancreatic Cancer Research, supported by the Thompson Foundation, the Pershing Square Foundation, the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and Northwell Health Affiliation, the Northwell Health Tissue Donation Program, the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Association, and the National Institutes of Health (5P30CA45508, U01CA210240, R01CA229699, U01CA224013, 1R01CA188134, and 1R01CA190092). This research was furthermore supported by the Robertson Research Fund of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (L.C.T) and it was done in collaboration with the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory shared resources, which are supported by the National Institutes of Health (Cancer Center Support Grant 5P30CA045508 (D.A.T.) to support the flow cytometry, microscopy, functional genomics, tissue culture, mass spectrometry, genome sequencing, gene targeting, animal husbandry and histology analysis of this project.

Footnotes

Competing Interests

R.L.W. received research funding from a grant involving AstraZeneca UK Limited. Unrelated to this work, M.E. has stock options in Agios Pharmaceuticals and was on the advisory board of Vividion Therapeutics. D.G.N has patent WO2008110777 issued (Modulators of vegf splicing as pro- and anti-angiogenic agents) with royalties paid and owns stock in D.G.N in Arvinas, Inc, D.A.T. receives stock options from Leap Therapeutics, Cygnal Therapeutics, Mestag Therapeutics, Xilis and Dunad, all unrelated to the project. Also unrelated to this project, D.A.T. is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board for Leap Therapeutics, Cygnal Therapeutics, Mestag Therapeutics, Xilis and Dunad, a scientific co-founder of Mestag Therapeutics and has received research grant support from Fibrogen, Mestag, and ONO Therapeutics and has has received consulting income from Amgen, all unrealted to this work. S.D.D. is founder and CSO of Amaroq Therapeutics Ltd and RNAfold.AI Pty Ltd, T.J. consults Flagship pioneering and LeapTx, L.C.T. consults Health Advances LLC unrelated to this work.

Data and materials availability:

All data are available in the manuscript and or the supplementary materials.

References and Notes

- 1.Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A, Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin 74, 12–49 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lippman SM et al. , Effect of selenium and vitamin E on risk of prostate cancer and other cancers: the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA 301, 39–51 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein EA et al. , Vitamin E and the risk of prostate cancer: the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA 306, 1549–1556 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cho HJ et al. , RapidCaP, a Novel GEM Model for Metastatic Prostate Cancer Analysis and Therapy, Reveals Myc as a Driver of Pten-Mutant Metastasis. Cancer Discovery 4, 318–333 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nowak DG et al. , MYC Drives Pten/Trp53-Deficient Proliferation and Metastasis due to IL6 Secretion and AKT Suppression via PHLPP2. Cancer Discov 5, 636–651 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taranda J. et al. , Combined whole-organ imaging at single-cell resolution and immunohistochemical analysis of prostate cancer and its liver and brain metastases. Cell reports 37, 110027 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liang WJ, Johnson D, Jarvis SM, Vitamin C transport systems of mammalian cells. Mol Membr Biol 18, 87–95 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keshari KR et al. , Hyperpolarized 13C dehydroascorbate as an endogenous redox sensor for in vivo metabolic imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 18606–18611 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yun J. et al. , Vitamin C selectively kills KRAS and BRAF mutant colorectal cancer cells by targeting GAPDH. Science 350, 1391–1396 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magri A. et al. , High-dose vitamin C enhances cancer immunotherapy. Sci Transl Med 12, (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keshari KR et al. , Hyperpolarized [1–13C]dehydroascorbate MR spectroscopy in a murine model of prostate cancer: comparison with 18F-FDG PET. J Nucl Med 54, 922–928 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verrax J. et al. , Enhancement of quinone redox cycling by ascorbate induces a caspase-3 independent cell death in human leukaemia cells. An in vitro comparative study. Free Radic Res 39, 649–657 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor BS et al. , Integrative genomic profiling of human prostate cancer. Cancer Cell 18, 11–22 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Armenia J. et al. , The long tail of oncogenic drivers in prostate cancer. Nat Genet 50, 645–651 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alexander J. et al. , Utility of Single-Cell Genomics in Diagnostic Evaluation of Prostate Cancer. Cancer Research 78, 348–358 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim B, Lin Y, Navin N, Advancing Cancer Research and Medicine with Single-Cell Genomics. Cancer Cell 37, 456–470 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanchez-Vega F. et al. , Oncogenic Signaling Pathways in The Cancer Genome Atlas. Cell 173, 321–337 e310 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tonelli C, Chio IIC, Tuveson DA, Transcriptional Regulation by Nrf2. Antioxid Redox Signal 29, 1727–1745 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyers RM et al. , Computational correction of copy number effect improves specificity of CRISPR-Cas9 essentiality screens in cancer cells. Nat Genet 49, 1779–1784 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerasimenko JV et al. , Menadione-induced apoptosis: roles of cytosolic Ca(2+) elevations and the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. J Cell Sci 115, 485–497 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loor G. et al. , Menadione triggers cell death through ROS-dependent mechanisms involving PARP activation without requiring apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med 49, 1925–1936 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Armstrong JA et al. , Oxidative stress alters mitochondrial bioenergetics and modifies pancreatic cell death independently of cyclophilin D, resulting in an apoptosis-to-necrosis shift. J Biol Chem 293, 8032–8047 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ben-Shem A, Frolow F, Nelson N, Crystal structure of plant photosystem I. Nature 426, 630–635 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green DE, Tzagoloff A, The mitochondrial electron transfer chain. Arch Biochem Biophys 116, 293–304 (1966). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kroger A, Klingenberg M, The kinetics of the redox reactions of ubiquinone related to the electron-transport activity in the respiratory chain. Eur J Biochem 34, 358–368 (1973). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vos M. et al. , Vitamin K2 is a mitochondrial electron carrier that rescues pink1 deficiency. Science 336, 1306–1310 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naguib A. et al. , Mitochondrial Complex I Inhibitors Expose a Vulnerability for Selective Killing of Pten-Null Cells. Cell Rep 23, 58–67 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wheaton WW et al. , Metformin inhibits mitochondrial complex I of cancer cells to reduce tumorigenesis. Elife 3, e02242 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dixon SJ et al. , Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 149, 1060–1072 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang WS, Stockwell BR, Ferroptosis: Death by Lipid Peroxidation. Trends Cell Biol 26, 165–176 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolpaw AJ et al. , Modulatory profiling identifies mechanisms of small molecule-induced cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, E771–780 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shimada K. et al. , Global survey of cell death mechanisms reveals metabolic regulation of ferroptosis. Nat Chem Biol 12, 497–503 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sullivan LB et al. , Supporting Aspartate Biosynthesis Is an Essential Function of Respiration in Proliferating Cells. Cell 162, 552–563 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galluzzi L. et al. , Molecular mechanisms of cell death: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2018. Cell Death Differ 25, 486–541 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boucrot E. et al. , Endophilin marks and controls a clathrin-independent endocytic pathway. Nature 517, 460–465 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watanabe S, Boucrot E, Fast and ultrafast endocytosis. Curr Opin Cell Biol 47, 64–71 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Backer JM, The intricate regulation and complex functions of the Class III phosphoinositide 3-kinase Vps34. Biochem J 473, 2251–2271 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Posor Y, Jang W, Haucke V, Phosphoinositides as membrane organizers. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 23, 797–816 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blondeau F. et al. , Myotubularin, a phosphatase deficient in myotubular myopathy, acts on phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate pathway. Hum Mol Genet 9, 2223–2229 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cao C, Laporte J, Backer JM, Wandinger-Ness A, Stein MP, Myotubularin lipid phosphatase binds the hVPS15/hVPS34 lipid kinase complex on endosomes. Traffic 8, 1052–1067 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bago R. et al. , Characterization of VPS34-IN1, a selective inhibitor of Vps34, reveals that the phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate-binding SGK3 protein kinase is a downstream target of class III phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Biochem J 463, 413–427 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jaber N. et al. , Class III PI3K Vps34 plays an essential role in autophagy and in heart and liver function. P Natl Acad Sci USA 109, 2003–2008 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Law F. et al. , The VPS34 PI3K negatively regulates RAB-5 during endosome maturation. J Cell Sci 130, 2007–2017 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Naguib A. et al. , PTEN Functions by Recruitment to Cytoplasmic Vesicles. Mol Cell 58, 255–268 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gillooly DJ et al. , Localization of phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate in yeast and mammalian cells. EMBO J 19, 4577–4588 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Christoforidis S. et al. , Phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinases are Rab5 effectors. Nat Cell Biol 1, 249–252 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rostislavleva K. et al. , Structure and flexibility of the endosomal Vps34 complex reveals the basis of its function on membranes. Science 350, aac7365 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ohashi Y, Tremel S, Williams RL, VPS34 complexes from a structural perspective. J Lipid Res 60, 229–241 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller S. et al. , Shaping development of autophagy inhibitors with the structure of the lipid kinase Vps34. Science 327, 1638–1642 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tremel S. et al. , Structural basis for VPS34 kinase activation by Rab1 and Rab5 on membranes. Nat Commun 12, 1564 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ketel K. et al. , A phosphoinositide conversion mechanism for exit from endosomes. Nature 529, 408–412 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Buj-Bello A. et al. , The lipid phosphatase myotubularin is essential for skeletal muscle maintenance but not for myogenesis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99, 15060–15065 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]