Abstract

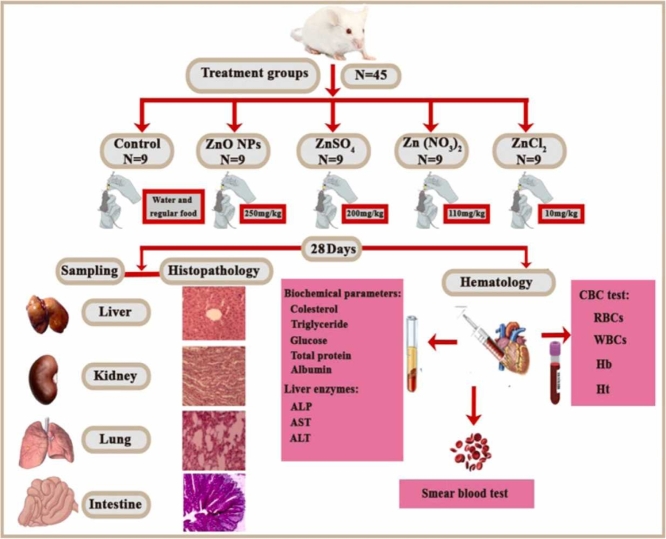

The aim of this study was to investigate the toxicity of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) compared to different zinc salts (ZnSO4, Zn(NO3)2, and ZnCl2) in male mice. For this purpose, 45 male mice were divided into five groups of nine (one control group). Mice were exposed to ZnO NPs and various zinc salts for 28 days, while the control group remained unexposed. After the exposure period, the mice were euthanized, and hematological, biochemical, enzymatic, and histopathological changes were recorded. Most hematological (RBC, WBC, Hb, Ht counts), biochemical (cholesterol, triglyceride, glucose, total protein, and albumin), and enzymatic parameters alkaline phosphatase (ALP), aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were significantly different in exposed mice compared to the control group (p < 0.05). The number of erythrocytes in mice exposed to ZnCl2 for 28 days (7.84 ± 1.41 × 106 mm3) was significantly lower than in the control group (10.11 ± 1.14 ×106 mm3) (p < 0.05). Additionally, mice exposed to ZnCl2 had significantly lower white blood cell (WBC) counts, hemoglobin (Hb), and hematocrit (Ht) levels than the control group (p < 0.05). Zn-exposed mice developed deformed erythrocytes, including dacrocytes, keratocytes, and ovalocytes, likely due to cytogenetically damaged RBC precursors. ZnO NPs and its various salts caused degeneration in hepatocytes, thickening and inflammatory cell infiltration in the renal capsule, congestion in the blood vessels of the lungs, and swelling of goblet cells in the intestine. Adding to the wealth of literature on the toxicity of ZnO NPs and zinc salts, especially ZnCl2, our study highlights the ecotoxicity of these compounds in mice. Effective and timely measures should be taken to reduce the use of ZnO NPs and its various salts worldwide.

Keywords: Ecotoxicity, Histopathology, Biochemical parameters, Hematological changes, Enzymatic activity

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

RBCs, Hb and Ht count were significantly reduced in mice exposed to ZnCl2 compared to the control group.

-

•

Most biochemical and enzymatic parameters were significantly different in exposed mice when compared to the control group.

-

•

The severity of morphological changes of erythrocytes exposed to ZnCl2 is much higher than other studied groups.

-

•

The severity of histopathological damage observed in the tissues of mice exposed to ZnCl2 was much greater than that of other groups.

1. Introduction

Nanoparticles (NPs) are now widespread in many industries, including cosmetics, packaging, automotive, electronics, healthcare, and textiles. As their production and use grow, so does the risk of human exposure. Despite their harmful effects, no measures are being taken to control their spread or limit their production. Enforceable global standards are urgently needed to protect public and environmental health [53], [75]. Literature review indicates that nanoparticles (NPs) damage human cell lines through mechanisms like oxidative stress and genotoxicity [37], [55]. Nanoparticles (NPs), which are less than 100 nm in size, can easily penetrate cell membranes. Produced as byproducts of combustion, NPs are linked to negative health impacts and contaminate soil and water [35], [37], [78]. Nanoparticles (NPs) can interact with other environmental pollutants, leading to increased toxicity. Their variable shape, size, and chemical composition enhance environmental risks. Warnings highlight NPs' negative global health impacts and their contribution to health inequity [21], [27], [35], [46], [73]. Zinc salts such as ZnCl2 cause oxidative stress and inflammation. Research has shown that zinc chloride affects neurotransmitter levels, leading to increased levels of aminergic neurotransmitters in various brain regions such as the hippocampus, olfactory lobe, and cerebellum [32]. Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) are extensively used in various industries, including medicine, electronics, chemicals, and consumer products. ZnO NPs are toxic to various organisms and can damage tissues through mechanisms like oxidative stress. This damage has been documented in animal models and human cell lines. Studies have shown histopathological changes in mice liver and kidney tissues after exposure to ZnO NPs. Hematology and histopathology are commonly used to study the impact of pollutants on organisms due to their effectiveness in detecting adverse effects [70], [74], [79], [80], [96]. Hematological biomarkers such as red blood cells (RBC), white blood cells (WBC), hemoglobin (Hb), and hematocrit (Ht%) are used to assess the health or sickness of mice, indicating oxygen-carrying capacity and immune system health. Serum parameters, including glucose, total protein, cholesterol, triglycerides, globulin, albumin, bilirubin, creatinine, and cortisol, provide insights into metabolism and health status, helping elucidate the toxic effects of metals. Additional parameters like MCV (Mean Corpuscular Volume), MCH (Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin), and MCHC (mean corpuscular hemogolobin concentration) are important for diagnosing anemia. Liver enzyme activity is used to detect stress, liver damage, or malfunction [19], [25], [74].

Enzymes like aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) are primarily produced in the liver but can leak into the bloodstream under stressful conditions, making them useful indicators of health and sickness in organisms [74]. The high level of ALP is associated with an increased risk of lung cancer and cancer-related mortality [49]. Elevated ALT and AST indicate liver damage, such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatitis [47], [69]. Liver and kidney tissues, known for their high absorption of pollutants, are suitable for histopathological examination to assess damage caused by ZnO NPs [71], [78]. Studies indicate that metal oxide nanoparticles and their salts exhibit varying toxic effects on different tissues. For example, selenium nanoparticles (Se-NPs) are more toxic to gill and liver tissues of iridescent shark catfish compared to selenium salts [56]. Conversely, iron nitrate (Fe(NO3)3) salt shows greater toxicity than Fe3O4 nanoparticles in various tissues of black fish [78]. Therefore, a comprehensive ecotoxicological assessment comparing ZnO NPs and zinc salts is essential. This study aims to investigate the toxicity of ZnO NPs versus its various salts on hematological parameters, biochemical profiles, liver enzymes, and tissue damage in the liver, kidney, lung, and intestine of male mice.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. ZnO NPs and zinc salts characterization

The ZnO nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) were systematically characterized using powder X-ray Diffraction (XRD) and Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) (Spectrum Two, Perkin Elmer, USA). XRD analysis was performed using equipment from Philips, Netherlands, to determine the crystal structure of the nanoparticles. FTIR spectroscopy was utilized to identify the presence and types of functional groups on the ZnO NPs. The ZnO NPs, obtained with 99 % purity, were sourced from 3302 Twig Leaf Lane, Houston, TX 77084, USA (Product code: 1314–13–2). Zinc salts, including ZnSO4·6 H2O, Zn(NO3)2·6 H2O, and ZnCl2·6 H2O, were procured from Merck (Merck, Germany).

2.2. Calculation of the LC50-96h and experimental design

The lethal concentration of ZnO and various salts on male mice (28–30 g) was investigated according to OECD guideline No. 233 to finally calculate the LC50–96h. For this purpose, five mice were exposed to different concentrations of ZnO and its various salts (1, 10, 30, 50, 100, 300, 500 mg/kg bw) for 96 hours with three replicates. Mortality rates were recorded at 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours at each concentration, and the lethal concentration 50 was calculated using probit software. The LC50–96h was calculated to be 500.08, 400.02, 220.11, and 20.03 mg/kg bw for ZnO, ZnSO4, Zn (NO3)2, and ZnCl2, respectively. Finally, 50 % of the LC50–96h was selected as the concentration used in this study.

In this study, 45 male mice (28–30 g) from Birjand University of Medical Sciences were used. They were kept on a standard diet with free access to food and water, under controlled conditions (12-hour light/dark cycle, 20–25°C, and relative humidity). The mice were acclimated to the lab environment for one week before being randomly divided into five groups of nine.

The groups were as follows:

-

•

Group A: Control (regular food and water).

-

•

Group B: 250 mg/kg body weight (bw) of ZnO nanoparticles [96].

-

•

Group C: 200 mg/kg bw of ZnSO4 [96].

-

•

Group D: 110 mg/kg bw of Zn(NO3)2 [90].

-

•

Group E: 10 mg/kg bw of ZnCl2 [16].

All groups received their respective treatments via oral gavage for 28 days. Following the completion of the relevant experiments, the mice were euthanized.

2.3. Measurement of zinc ion concentration in different tissues of mice

During the bioaccumulation period (7, 14, and 28 days), liver, kidney, intestine, and lung tissues from mice exposed to ZnO NPs, ZnSO4, Zn(NO3)2, and ZnCl2 were isolated after anesthetization with ketamine-xylazine. Each tissue was placed in a glass tube with 5 ml of nitric acid (HNO3) and 2.5 ml of perchloric acid (HClO4). The tubes were heated in a water bath at 80°C for 4–6 hours until digestion was complete. The digested samples were filtered, and the remaining liquid was diluted to 20 ml with distilled water. Zinc ion concentration in each tissue was measured using graphite furnace atomic absorption spectroscopy (ContrAA 700, Analytik Jena AG, Germany) [53].

2.4. plasma and serum collection

Blood samples were collected from the hearts of anesthetized mice using a syringe with a 23-gauge needle. A mixture of ketamine and xylazine was used to anesthetize the mice. The blood was placed in pre-labeled potassium EDTA anticoagulant tubes, stored in an ice box, and then transferred to a −20°C refrigerator. For serum collection, 1 ml of blood was placed in Eppendorf tubes (Pars Payvand Co.) without anticoagulant and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes. The supernatant was transferred to clean, labeled Eppendorf tubes and stored at −20°C for further tests [93]. Given that chemical euthanasia methods can cause changes in the quality of tissues and analytes, physical euthanasia methods such as decapitation were used in this study. This method is painless and inexpensive, and the animal experiences less fear and anxiety than chemical methods. Decapitation, as a method of physical euthanasia, induces rapid and painless death via immediate disruption of the nervous system, and, unlike chemical euthanasia, does not alter metabolic markers [97]. In this method, the head of the mouse is quickly cut off by guillotine [66].

2.5. Bioaccumulation of ZnO NPs and Zinc salts in mice serum

To measure zinc accumulation in the serum, blood was collected from the mice's hearts at 7, 14, and 28 days and placed into Eppendorf tubes. The samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes to separate the serum. The serum was transferred to clean test tubes, mixed with 2 ml of nitric acid and 1 ml of perchloric acid, and subjected to acidic digestion in a water bath for 2 hours. After cooling to room temperature, the samples were filtered to remove impurities, stored in clean containers, and kept in a refrigerator. They were analyzed a week later using graphite furnace atomic absorption spectroscopy. The detection limit for zinc was 0.55 µg/l with a relative standard deviation of 2 % [74].

2.6. Hematology

The differential count of RBCs was performed manually after dilution with an isotonic salt solution using a Neubauer slide. The blood sample was vigorously shaken to ensure homogeneity. A 1:200 dilution of blood and isotonic salt solution (0.85 g NaCl in 100 ml distilled water) was prepared in an RBC counting pipette, and counts were done under a light microscope. For WBC count, a 1:20 dilution of the blood sample and Marcano's solution (2 ml CH₃COOH, 1 ml 1 % dolegensin violet solution, and 100 ml distilled water) was made using a WBC melange pipette.

| Number RBCs in per mm3 of blood = Total number of RBCs counted in 5 small squares of Neuobuer slide × 200 × 10 × 5 | (1) |

Number 10 is a correction factor to account for the distance between slide and slider

Number 200 is a dilution factor

The number of WBCs on the Neuobuer slide (in 4 cells for WBCs) was then calculated under a microscope using

| (2) |

W: Number of WBCs in each Neuobuer slide house

Number 10 is a correction factor of the distance between slide and slider

Number 20 is a dilution factor

Hemoglobin levels were estimated by hemoglobinometer.

A hemoglobinometer, consisting of a pipette, hemometer tube, stirring rod, and dropper, was used. Hydrochloric acid was added to the calibrated hemometer tube up to a designated mark. The tube was placed in the hemoglobinometer, and 20 µl of blood was pipetted into it. The blood and acid were mixed with a stirrer and left for 10 minutes to form hematin acid. Distilled water was then added drop by drop until the color of the solution matched the calibration tube. The hemoglobin level (gm/dl) was read from the hemometer tube [42], [63].

To measure hematocrit, capillary tubes were filled two-thirds with blood, and the openings were sealed with hematocrit paste. The tubes were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 minutes. The percentage of hematocrit was then calculated using the Eq. 3 [26], [41].

| (3) |

Globular indices such as MCV, MCH and MCHC were calculated using a Symex xs-800i device.

2.7. Erythrocytes changes

At the end of the 28-day bioaccumulation period, blood was collected, and a blood smear was prepared on a glass slide. The slide was air-dried, fixed with methanol, and stained with Giemsa stain. Erythrocyte structural changes were then examined under a light microscope [39].

2.8. Biochemical analysis

Biochemical markers including cholesterol, triglyceride, glucose, total protein, albumin, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL) along with enzymatic parameters such as Aspartate Amino Transferase (AST), Alanine Amino Transaminase (ALT), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP), were analyzed using a Hitachi 917 biochemical autoanalyzer device from Hitachi Company, Japan. Serum samples, prepared as described earlier, were used for analysis with commercial kits from Pars Azmoun Company, Iran (Registration Code 34998). Detailed methods can be found in the literature [36], [40].

2.9. Histopathological examinations

The tissues (liver, kidney, lung, and intestine) from mice in all five experimental groups (including one control group) were collected after 28 days. The samples were fixed in 10 % formalin for 24 hours. Dehydration was carried out using a series of alcohol concentrations (50 %, 70 %, 80 %, 90 %, and 96 %), with each step lasting one hour. Subsequently, the samples were infiltrated with liquid paraffin for 5 hours at 60 degrees Celsius, followed by embedding and sectioning into 5-micrometer sections using a microtome. Hematoxylin-eosin stain was applied to the sections for visualization. Finally, the tissue sections were examined and photographed using a Nikon Eclips-E200 light microscope [53].

2.10. Statistical analysis

SPSS software version 20 was utilized for data analysis. The normality of the data was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, revealing that the data (presented as mean ± standard deviation) were not normally distributed. Consequently, differences between groups were evaluated using the Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test, with significance set at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of Zinc oxide NPs

The properties of ZnO nanoparticles (NPs) were evaluated using X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) and Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), as shown in Fig. 1. The XRD pattern (Fig. 1a) displayed diffraction peaks at 2θ angles of 31.52°, 34.63°, 36.39°, 47.62°, 56.83°, 62.94°, and 68.15°, corresponding to the (100), (002), (101), (102), (110), (103), and (112) reflection planes of ZnO, respectively[79]. The FTIR spectrum (Fig. 1b) showed peaks at 433.08 and 1498.35 cm⁻¹ , indicating Zn-O bonds, a peak at 1740 cm⁻¹ corresponding to C O bonds, and a broad band at 3433 cm⁻¹ indicating O-H bonds, which may suggest the presence of impurities or moisture absorption [6], [92].

Fig. 1.

(a) X-ray spectroscopy analysis of ZnO NPs and (b) Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy of ZnO NPs (FTIR).

3.2. Zn concentration in different tissues of mice

The bioaccumulation trends of ZnO NPs, ZnSO4, Zn(NO3)2, and ZnCl2 in the liver, kidney, lung, and intestine tissues of mice are illustrated in Fig. 2. The bioaccumulation patterns observed are as follows: for ZnO NPs, ZnSO4, and Zn(NO3)2, the order is intestine > liver > lung > kidney; for ZnCl2, the order is liver > intestine > lung > kidney. Additionally, the amount of bioaccumulation of these zinc compounds in various tissues increased over time from 7 to 14 days.

Fig. 2.

Accumulation of Zinc (µg/g) in the liver, kidney, intestine, and lung tissues of mice exposed to ZnO NPs, ZnSO4, Zn(NO3)2, and ZnCl2.

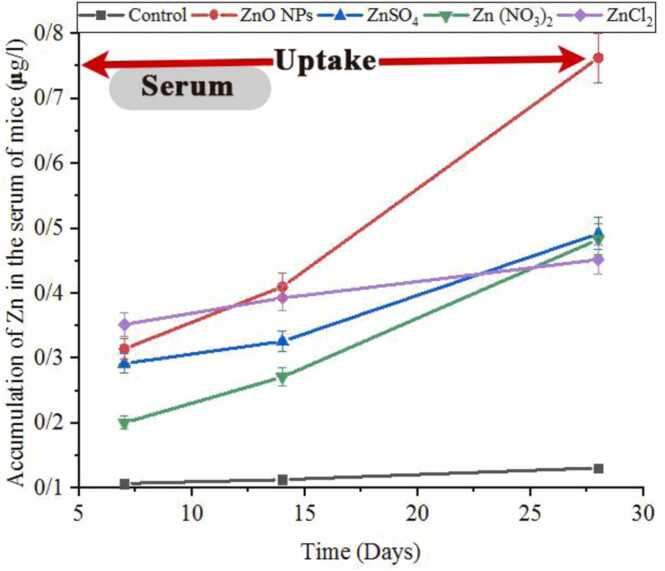

3.3. Bioaccumulation of Znic in mice serum exposed to ZnO NPs and Zinc salts

Fig. 3 shows the levels of Zinc (µg/l) in the serum of mice exposed to ZnO NPs and other zinc salts over 7, 14, and 28 days. Zinc bioaccumulation increased over time, with the highest levels observed at 28 days. After 28 days, the bioaccumulation pattern was: ZnO NPs > ZnSO4 > Zn(NO3)2 > ZnCl2 > control.

Fig. 3.

Accumulation of Zinc (µg/l) in the blood of mice exposed to ZnO NPs and other zinc salts.

3.4. Impact of ZnO nanoparticles and Zinc salts on hematological parameters in mice

3.4.1. RBC, WBC, hemoglobin, and hematocrit

The effects of ZnO NPs and the salts ZnSO4, Zn(NO3)2, and ZnCl2 on hematological parameters in mice are shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Changes in the number of red and white blood cells, hemoglobin levels, and hematocrit (%) in mice exposed to Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) and other Zinc salts for 28 days: * indicates a significant difference compared to the control group (p < 0.05).

The number of RBCs (million/mm3) in the blood of mice exposed to ZnO NPs (9.74 ± 1.16), ZnSO4 (9.18 ± 1.92), Zn(NO3)2 (8.13 ± 0.65), and ZnCl2 (7.84 ± 1.41) had decreased RBC counts compared to the control group (10.11 ± 1.14). This decrease was significant for Zn(NO3)2 and ZnCl2 (p < 0.05).

The number of WBCs (thousand/mm3) in the blood of mice exposed to ZnO NPs (3.57 ± 0.53), ZnSO4 (3.23 ± 0.77), and Zn(NO3)2 (2.78 ± 0.41) showed a decrease in WBC count compared to the control group (3.60 ± 0.62), but this was not significant. In contrast, mice exposed to ZnCl2 (4.38 ± 0.70) had significantly higher WBC counts than the control group (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5).

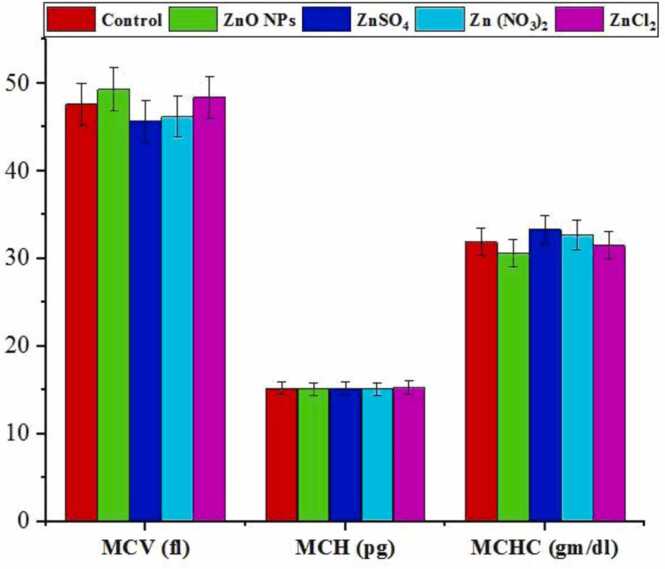

Fig. 5.

The hematological effects of exposure to Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) in mice over 28 days, compared to exposure to other Zinc salts. Parameters measured include mean corpuscular volume of erythrocytes (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC).

Hb levels in mice exposed to ZnO NPs (14.9 ± 4.29) and ZnSO4 (14.8 ± 2.07) decreased compared to the control group (15.9 ± 4.29), though not significantly. However, the decrease was significant for Zn(NO3)2 (13.9 ± 2.08) and ZnCl2 (13.7 ± 3.83) (p < 0.05).

Ht levels in mice exposed to ZnO NPs (46.2 ± 12.19), ZnSO4 (44.8 ± 3.13), Zn(NO3)2 (44.1 ± 3.96), and ZnCl2 (39.8 ± 5.57) decreased compared to the control group (46.4 ± 12.52), with a significant reduction for ZnCl2 (p < 0.05). Behavioral changes observed in mice exposed to ZnCl2 include mild tremors, decreased locomotor activity, restlessness, and increased salivation and tearing, which are less severe in mice exposed to ZnO NPs, Zn(NO3)2, and ZnSO4.

3.4.2. MCV, MCH and MCHC

The changes in MCV, MCH, and MCHC indices across different study groups are shown in Fig. 5. The results indicate that there are no significant differences (p < 0.05) in MCV, MCH, and MCHC levels when compared to the control group.

3.5. Erythrocyte changes

Fig. 6 illustrates structural changes in erythrocytes after 28 days in treatment groups compared to the control group. Erythrocytes in the control group appear normal. Morphological changes observed in erythrocytes exposed to ZnO NPs include Dacrocyte and Keratocyte formations. Exposure to ZnSO4 resulted in Dacrocyte and Ovalocyte formations, while exposure to Zn(NO3)2 led to Keratocyte, Ovalocyte, and Schistocyte formations. Mice exposed to ZnCl2 exhibited extensive erythrocyte deformities, including Dacrocyte, Keratocyte, Ovalocyte, and Schistocyte formations. The results indicate that the severity of morphological damage in erythrocytes exposed to ZnCl2 is notably higher compared to the other groups.

Fig. 6.

The effects of Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) and other Zinc salts on the structure of erythrocytes in mice following 28 days of exposure.

3.6. Effect of ZnO NPs and Zinc salts on serum biochemical parameters

3.6.1. Cholesterol, triglyceride and glucose levels

Table 1 presents changes in various biochemical parameters in blood serum following exposure to ZnO nanoparticles (NPs) and zinc salts. Serum cholesterol levels in mice exposed to ZnO NPs, ZnSO4, Zn(NO3)2, and ZnCl2 are higher compared to the control group, with significance observed only for ZnCl2 (p < 0.05). Serum triglyceride levels in mice exposed to ZnO NPs, ZnSO4, Zn(NO3)2, and ZnCl2 are lower than in the control group, with significance noted for Zn(NO3)2 and ZnCl2 (p < 0.05). Serum glucose levels in mice exposed to ZnO NPs, ZnSO4, Zn(NO3)2, and ZnCl2 are significantly higher compared to the control group (p < 0.05).

Table 1.

Results of biochemical biomarkers of toxicity in mice exposed to Zinc oxide nanoparticles and other Zinc salts for 28 days.

| Parameters | Days | Control | ZnO NPs | ZnSO4 | Zn (NO3)2 | ZnCl2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cholesterol(mg/dl) | 28 | 151 ± 7.5 | 157 ± 18.8 | 153 ± 12.2 | 167 ± 30.1 | 189 ± 39.6* |

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) | 28 | 193 ± 46.3 | 191 ± 34.3 | 177 ± 28.3 | 168 ± 23.5* | 168 ± 30.2* |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 28 | 101 ± 19.1 | 137 ± 17.8* | 134 ± 13.4* | 143 ± 15.7* | 224 ± 53.7* |

| Protein (mg/dl) | 28 | 3.9 ± 0.5 | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 3.1 ± 0.3 | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 2.7 ± 0.5* |

| Albumin (mg/dl) | 28 | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 2.8 ± 0.5* | 2.8 ± 0.4* | 2.9 ± 0.4* | 2.2 ± 0.6* |

| HDL (mg/dl) | 28 | 49 ± 6.5 | 43 ± 11.2 | 43 ± 9.4 | 41 ± 14.6 | 27 ± 6.3* |

| LDL (mg/dl) | 28 | 51 ± 13.1 | 53 ± 9.7 | 53 ± 10.3 | 57 ± 17.2 | 83 ± 14.8* |

Values are represented as means ± SD (n = 3). The different superscripts show significant differences (P < 0.05)

3.6.2. Total protein and albumin levels

Based on the results, the findings from Table 1 indicate that the protein levels in serum exposed to ZnO NPs, ZnSO4, Zn(NO3)2, and ZnCl2 were lower compared to the control group, with significance observed only for ZnCl2 (p < 0.05). Serum albumin levels exposed to ZnO NPs, ZnSO4, Zn(NO3)2, and ZnCl2 were significantly lower than in the control group (p < 0.05).

3.6.3. HDL and LDL levels

Table 1 shows serum HDL and LDL levels. Based on the results obtained, HDL levels in mice exposed to ZnO NPs and its various salts decreased compared to the control group. Serum HDL levels in mice exposed to ZnCl2 were significantly (p < 0.05) lower than in the control group. The results show that LDL levels in the ZnCl2 exposed group were significantly (p < 0.05) higher than the control group.

3.6.4. Impact of ZnO NPs and Zinc salts on enzymatic parameters of serum

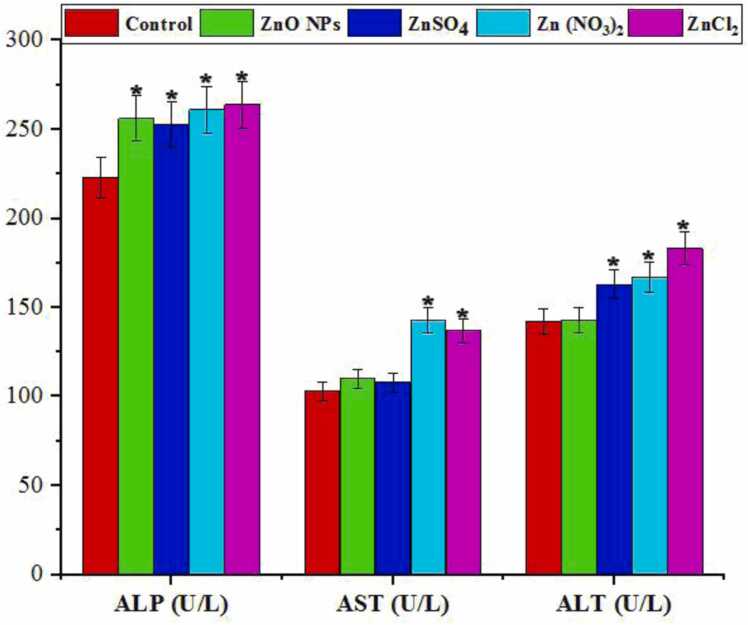

Exposure to zinc compounds resulted in a significant increase in liver enzymes (ALP, AST, and ALT) (p < 0.05), as depicted in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

summarizes the blood serum enzyme activity in mice exposed to Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) and other Zinc salts for 28 days (n = 2). The enzymes evaluated include alkaline phosphatase (ALP), aspartate amino transferase (AST), and alanine amino transferase (ALT). * denotes a significant difference compared to the control group (P < 0.05).

3.7. The effect of ZnO NPs and zinc salts on the weight and behavior of exposed mice

Table 2 summarizes the findings related to weight loss and behavioral changes in mice exposed to zinc compounds. All groups exposed to zinc compounds showed weight loss by the end of the study period, with significance observed only in the ZnCl2 group (P < 0.05). Behaviorally, mice exposed to ZnCl2 exhibited reduced motor activity and food consumption, with these effects becoming more pronounced over time.

Table 2.

Weight changes of mice exposed to zinc oxide nanoparticles and zinc salts. * denotes significant difference with the control group.

| Control | 7 Days |

14 Days |

28 Days |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 ± 1.15 | 30 ± 2.24 | 29 ± 1.38 | |

| ZnO NPs | 28 ± 2.71 | 27 ± 2.16 | 26 ± 2.52 |

| ZnSO4 | 28 ± 3.12 | 26 ± 3.62 | 26 ± 2.93 |

| Zn (NO3)2 | 29 ± 1.18 | 29 ± 1.73 | 27 ± 1.37 |

| ZnCl2 | 30 ± 2.15 | 27 ± 1.62 | 25 ± 2.18* |

3.8. Histopathological studies

3.8.1. Liver tissue damage

Fig. 8 illustrates a series of histopathological changes observed in the liver tissue of mice exposed to Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) and its various salts. The control group exhibits a normal structure of the central vein. Mice exposed to ZnO NPs show a dilated central vein (cv). Liver tissue exposed to ZnSO4 displays dilation of the central vein (cv) and rupture of the central vein wall (rcv). Histopathological changes in the liver of mice exposed to Zn(NO3)2 include dilation of the central vein (cv) and hepatocyte degeneration (d). Liver tissue from mice exposed to ZnCl2 shows dilation of the central vein (cv), portal vein (pv), aggregation of melanomacrophages next to the central vein (m), infiltration of inflammatory cells (if), and degeneration of liver cells (d). The severity of liver damage in the ZnCl2-exposed group is notably higher compared to the other groups studied.

Fig. 8.

Histopathological liver damage observed in mice exposed to Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) and various zinc salts after 28 days. CV: Dilatation in the central vein; RCV: Rupture of the wall of the central vein; D: Degeneration in hepatocytes; PV: Dilatation in the portal vein; M: Aggregation of melanomacrophage next to the central vein; IF: Infiltration of inflammatory cells. Images were captured using H&E staining at 40x magnification.

3.8.2. Kidney tissue damage

Fig. 9 illustrates histological damage in the kidney tissue of mice exposed to Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) and various zinc salts after 28 days. The control group displays normal kidney tissue structure. Kidney tissue exposed to ZnO NPs shows thickening and inflammatory cell infiltration in the renal capsule (g). Exposure to ZnSO4 results in thickening and inflammatory cell infiltration in the renal capsule (g) and degeneration in the lining epithelium of tubules (d). Kidney tissue exposed to Zn(NO3)2 exhibits perivascular inflammatory cell infiltration (m) and degeneration in the lining epithelium of tubules (d). Damage in the kidney tissue of mice exposed to ZnCl2 is severe, characterized by perivascular inflammatory cell infiltration (m), focal inflammatory cell infiltration between tubules in the perivascular area (v), and thickening and inflammatory cell infiltration in the renal capsule (g).

Fig. 9.

Histopathological kidney damage observed in mice exposed to Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) and various zinc salts after 28 days. g: Thickening and inflammatory cell infiltration in the renal capsule; m: Perivascular inflammatory cell infiltration; d: Degeneration in the lining epithelium of tubules; v: Focal inflammatory cell infiltration between tubules in the perivascular area. Images were captured using H&E staining at 40x magnification.

3.8.3. Lung tissue damage

Fig. 10 depicts histopathological damages observed in the lung tissue of mice exposed to Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) and various zinc salts after 28 days. In the control group, normal structures of air alveoli (a) and bronchioles (b) are observed. Lung tissue exposed to ZnO NPs, ZnSO4, and Zn(NO3)2 shows peribronchiolar inflammatory cell infiltration (m) and emphysema in air alveoli (e). Exposure to ZnCl2 results in severe histopathological damage in the lungs, including emphysema in air alveoli (e), peribronchiolar inflammatory cell infiltration (m), and congestion of blood vessels (v).

Fig. 10.

summarizes histopathological lung damage observed in mice exposed to Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) and various zinc salts after 28 days. Control group: Normal structure of air alveoli (a) and bronchioles (b). e: Emphysema in air alveoli, m: Peribronchiolar inflammatory cell infiltration, v: Congestion of blood vessels. The images were captured using H&E staining at 40x magnification.

3.8.4. Intestine tissue damage

Fig. 11 depicts the impact of Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) and various zinc salts on the intestinal tissue of mice following 28 days of exposure. The control group exhibits normal intestinal tissue structure. Mice exposed to ZnO NPs showed swelling of goblet cells (SG) and an increase in goblet cell number (INGC). Similarly, exposure to ZnSO4 resulted in goblet cell swelling (SG) and increased goblet cell count (INBC). In mice exposed to Zn (NO3)2 and ZnCl2, there was observed swelling and an increase in both goblet cell (SG) and blood cell numbers (INBC). Notably, the intestinal tissue damage intensity was notably higher in the ZnCl2-exposed group compared to others.

Fig. 11.

Histopathological Intestine Damage in Mice Exposed to Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) and Various Zinc Salts After 28 Days. SG: Swelling of the number of goblet cells, INGC: increase in the number of goblet cells, INBC: increase in the number of blood cells. Images were captured using H&E staining at 40x magnification.

4. Discussion

Metal nanoparticles, including zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs), have infiltrated our environment and daily lives with minimal precautionary measures. This has had significant adverse impacts on the environmental health of organisms, as revealed by literature reviews highlighting their cytotoxic, genotoxic, and epigenetic effects [86]. Various organisms, including mice studied here, are particularly susceptible to these pollutants, showing changes in molecular physiology and behavior. Exposure to ZnO NPs and its salts resulted in altered levels of red and white blood cells, structural deformities in erythrocytes, and extensive histopathological damage in liver, kidney, lung, and intestinal tissues among the studied mice.

4.1. Bioaccumulation of ZnO NPs and Zinc salts

Various studies examining the toxicity and bioaccumulation of different nanoparticles and their salts present conflicting findings. Some research suggests that metal nanoparticles exhibit greater toxicity and bioaccumulation compared to their corresponding salts [18], [48], whereas other studies indicate that metal salts can be more toxic than their nanoparticles [53], [78], [80]. In our study, all tested compounds were found to bioaccumulate in mice tissues. Specifically, ZnO NPs, ZnSO4, and Zn (NO3)2 showed a bioaccumulation pattern of intestine > liver > lung > kidney based on the obtained results.

Furthermore, the bioaccumulation pattern of ZnCl2 is liver, intestine, lung and kidney, respectively. Surprisingly, despite the accumulation of ZnO more than ZnCl2 in various tissues, ZnCl2 caused significant damage to the blood and tissues of mice. This discrepancy suggests that while ZnO NPs may accumulate in tissues, potentially reducing their toxicity through sequestration, other zinc salts like ZnCl2, which do not accumulate as much in tissues, may circulate more freely within the digestive system, leading to greater damage across various tissues [53]. The high metabolic activity observed in the liver and intestinal tissues likely contributes to the pronounced accumulation of ZnO NPs in these areas [78].

In a similar study, Kharkan and collogues found that nickel oxide nanoparticles (NiO NPs) predominantly accumulated in the intestinal tissue of black fish (Capoeta fusca), whereas nickel sulfate (NiSO4), nickel nitrate (Ni (NO3)2), and nickel chloride (NiCl2) accumulated primarily in the kidney. They observed that the high metabolic activity of the intestine facilitated the absorption of NiO NPs, potentially reducing its toxicity through sequestration in tissues. In contrast, other nickel compounds were absorbed to a lesser extent in tissues, allowing them to circulate more freely and potentially cause more widespread damage across different tissues [53].

Sayadi et al. [78] found that iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4 NPs) accumulate more readily in the tissues of black fish compared to iron nitrate (Fe (NO3)3), which is present in lower amounts. Despite higher accumulation of Fe3O4 NPs in black fish tissues, Fe (NO3)3 induced greater damage in these tissues [78]. Additionally, Zinicovscaia et al. [100] reported that silver nanoparticles exhibited the highest bioaccumulation in liver tissue, followed by the brain, with the lowest accumulation observed in the blood of mice.

4.2. Bioaccumulation of Zinc in mice blood exposed to ZnO NPs and Zinc salts

This study confirms significant bioaccumulation of zinc in mice serum and highlights the severe toxic effects of both zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) and zinc salts. Zinc was found to accumulate extensively in various tissues, leading to oxidative damage, which aligns with previous findings in the literature.

4.3. RBC, WBC, Ht and Hb count

Exposure to ZnO NPs and various zinc salts resulted in significant hematopoietic tissue damage in mice, as evidenced by altered RBC morphology and micronuclei formation [81], [83]. Compared to the control group, mice exposed to these compounds showed a notable decrease in RBC count, WBC count, Hb and Ht levels (p < 0.05). Notably, WBC count was significantly higher in the ZnCl2-exposed group compared to controls (p < 0.05). These findings underscore the damaging effects of ZnO NPs and zinc salts on the structure and function of hematopoietic cells, consistent with previous research [57].

Exposure to ZnCl2 resulted in anemia in mice, characterized by normocytic type as indicated by stable MCV, MCH, and MCHC levels compared to the control group (Fig. 5). The reduced counts of RBCs, hematocrit, and hemoglobin suggest that anemia may stem from impaired red blood cell production in the bone marrow rather than hemolysis, as MCV did not increase, which would typically occur in hemolytic anemia. The significant declines in hematocrit and hemoglobin levels observed in mice exposed to ZnO NPs and other zinc salts likely result from the accumulation of these compounds in erythrocytes, leading to structural and functional changes and consequent detrimental effects [9]. Similar findings of decreased RBCs, WBCs, hemoglobin, and hematocrit in animals exposed to various nanoparticles and salts have been reported in other studies [10], [29], [89].

The widespread use of ZnO NPs and various zinc salts, notably ZnCl2, has proceeded without adequate precaution for decades, leading to evident dangers to human health and the environment. Restricting the use of these compounds is crucial, alongside prioritizing the cleanup of contaminated sites as a top global priority.

4.4. Calculated hematological indices

The study observed that changes in RBC, Hb, and Ht values could influence calculated indices such as MCV, MCH, and MCHC, as they are derived from these parameters. However, no significant differences were detected in MCV, MCH, and MCHC levels among mice exposed to ZnO NPs, ZnSO4, Zn (NO3)2, and ZnCl2 in this research. This finding aligns with similar observations in current literature [51], [74], [87], [93].

4.5. Structural changes in erythrocytes

The current study highlights the significance of investigating erythrocyte morphology in toxicological research, as it provides insights into the effects of toxins on living systems. After 28 days of exposure to various Zn compounds, this research observed significant erythrocyte deformations (Fig. 6). Red blood cells exposed to zinc oxide nanoparticles exhibited morphological changes, specifically the formation of Dacrocytes (tear-drop shaped cells) and keratocytes (cells with horn-like projections). Exposure to ZnSO4 resulted in the formation of Dacrocytes and ovalocytes (elliptical-shaped red blood cells). In contrast, exposure to Zn(NO3)2 induced the formation of schistocytes (crescent-shaped or triangular fragmented red blood cells) in addition to Dacrocytes and ovalocytes. Exposure to ZnCl2 induced severe morphological alterations, resulting in the presence of Dacrocytes, keratocytes, ovalocytes, and schistocytes (crescent-shaped or triangular fragmented red blood cells).

The study reveals that ZnCl2 exposure causes significantly more severe morphological damage to erythrocytes compared to other groups. Dacrocytes form teardrop shapes, keratocytes result from fibrin strands cutting erythrocytes, ovalocytes appear oval-shaped, and schistocytes are fragmented erythrocytes often triangular in shape [67]. Nanoparticles, including Zn compounds, can induce toxicity by interacting with cell receptors, cytoplasm, or organelle membranes, leading to structural and functional cellular changes that disrupt normal cell function [58]. Previous research by Pleskova et al. [67] demonstrated that magnetite nanoparticles can penetrate erythrocyte membranes, causing poikilocytosis and anisocytosis. Studies on various organisms have shown that nanoparticles like silver nanoparticles can induce nuclear pyknosis, vacuolated cytoplasm, and micronuclei in erythrocytes, emphasizing their toxic effects [74], [82], [95].

4.6. Biochemical parameters

4.6.1. Cholesterol, triglycerides, and glucose level

Exposure to Zinc compounds resulted in elevated blood cholesterol levels in mice, a recognized biomarker of stress induced by environmental toxicants [54]. The rise in cholesterol was associated with liver dysfunction, as indicated by changes in ALP, AST, and ALT enzyme activities (Fig. 7 and Fig. 8) [74]. Similar effects have been observed with other heavy metals, where increased cholesterol levels correlated with liver tissue disturbance and enzyme activity changes [77], [8]. These findings underscore the impact of environmental contaminants on lipid metabolism and liver function in various organisms [50], [74], [94].

The study results indicate that exposure to ZnO NPs, ZnSO4, Zn (NO3)2, and ZnCl2 led to lower serum triglyceride levels compared to the control group, with significant differences observed for Zn (NO3)2 and ZnCl2 (p < 0.05). This reduction in triglycerides in the blood is often associated with liver damage and dysfunction, as suggested by previous research [74]. These findings are consistent with other studies that have reported similar effects of environmental contaminants on lipid metabolism [21], [59].

The study found that exposure to zinc compounds, including ZnO NPs, ZnSO4, Zn (NO3)2, and ZnCl2, resulted in increased blood glucose levels in mice, indicating stress and increased energy expenditure to cope with stressors. This rise in glucose levels suggests mechanisms such as the breakdown of stored glycogen or accelerated gluconeogenesis, a metabolic process generating glucose from non-carbohydrate sources, which is enhanced during stress [74]. Similar effects on glucose metabolism have been reported in other studies investigating the impact of environmental stressors on organisms [20], [24], [38].

4.6.2. Total protein and albumin level

The study observed decreased levels of total protein and albumin in mice exposed to zinc compounds, indicating potential liver and kidney damage that could impair protein synthesis [74]. Albumin, crucial for transporting various substances in the blood, particularly reflects liver function [84]. The reduction in protein levels may be linked to increased gluconeogenesis, a process that provides energy in response to stress induced by zinc exposure [74]. This study's findings align with previous research highlighting the impact of zinc compounds on protein metabolism and organ function [11], [12], [3].

4.6.3. HDL and LDL levels

high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) are lipoproteins made of fat and protein. HDL is known as "good cholesterol" because it carries cholesterol to the liver to be excreted from the body. In fact, HDL helps the body get rid of excess cholesterol. And hence, it is less likely to lodge in the arteries. In contrast, LDL is called “bad fat” because it carries cholesterol to your arteries, where it can build up in your artery walls. Based on the results obtained, ZnCl2 causes a significant decrease in HDL and a significant increase in LDL compared to the control group. These results are consistent with other studies [99], [5].

4.6.4. ALP, AST and ALT activities

The study highlights significant elevations in serum ALP, AST, and ALT levels in mice exposed to various zinc compounds, suggesting liver injury and hepatocyte damage [33]. These enzymes are crucial indicators of liver function and their increase in serum can signify liver dysfunction due to zinc toxicity [88]. ALP, associated with hepatocyte membrane integrity, showed alterations, indicating potential damage to liver cells [61]. This aligns with ecotoxicological findings where serum enzymes serve as sensitive biomarkers of pollutant exposure and health risks in organisms [64]. Previous studies also support our findings on the toxic effects of zinc compounds on liver enzymes [14], [4], [58], [62], [74].

4.7. Histopathological studies

4.7.1. Liver tissue damage

The liver, a vital organ, plays a central role in detoxifying pollutants in organisms [7]. Comprising 80 % of liver cells, hepatocytes' membrane health is crucial for proper liver function. Physicochemically, ZnO NPs can disrupt liver function due to their properties, potentially entering liver cells and causing dysfunction in mice [13], [2].

The liver exposed to ZnO NPs shows a dilated central vein, while mice exposed to ZnCl2 exhibit more severe liver damage including dilation in the central and portal veins, aggregation of melanomacrophages, inflammatory cell infiltration, and liver cell degeneration. This indicates that ZnCl2 induces more pronounced liver damage compared to other compounds studied. Nanoparticles entering the body accumulate in the liver and kidneys, where they are absorbed by cells. Liver macrophages remove nanoparticles, generating free radicals. Free radicals from ZnO NPs may lead to lipid peroxidation of liver membranes, reducing membrane fluidity, disrupting cell structure, and ultimately causing liver cell damage [88].

Abd-Alsahib and Faris [2] reported that graphene oxide nanoparticles (GO NPs) induce damage in liver cells of mice, including nucleus proliferation, thickening, inflammatory cell infiltration, and tissue bleeding. Sayadi and Kharkan [77] found that exposure to various heavy metals causes structural damage in the gill tissue of black fish (Capoeta fusca), such as fusion and shortening of secondary lamellae, and in intestinal tissue, they observed swelling and increased numbers of goblet cells. Kharkan et al. [53] studied the effects of NiO NPs and its salts on black fish gills, noting fusion and shortening of secondary lamellae, with Ni (NO3)2 showing greater damage than NiO NPs. Abd El-Aziz et al. [1] investigated the impact of Fe3O4 NPs on mice liver tissue, observing changes in liver cell morphology and the formation of inflammatory Kupffer cells. These studies highlight various detrimental effects of nanoparticles and heavy metals on different tissues and organisms, underscoring their potential toxicological impacts.

4.7.2. Kidney tissue damage

The kidney tissue is particularly vulnerable to pollutants like nanoparticles, which accumulate there extensively [91]. Studies confirm that ZnO NPs and its salts induce toxicity through oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation, leading to oxidative responses and apoptosis [44]. In mice exposed to ZnO NPs and its salts, histopathological analysis revealed perivascular and focal inflammatory cell infiltrations, as well as thickening and inflammatory cell infiltration in the renal capsule (Fig. 9). The small size of nanoparticles enhances their surface area, making them highly reactive and increasing their absorption across biological membranes [23]. As the use of ZnO NPs grows, so does the potential for increased exposure to these nanoparticles [13], [68].

In studies similar to this research, Esmaeillou et al. [30] found that ZnO NPs induce severe toxicological effects on the kidney, including glomerular segmentation, hydropic degeneration in epithelial cells, necrosis of tubular epithelial cells, and swelling in proximal tubule epithelial cells. Fadia et al. [31] reported that gold nanoparticles (GNPs) cause congested vessels, lymphocytic infiltration, tubular degeneration, and necrosis in mice kidney tissue. Ibrahim et al. [45] observed diminished and distorted glomeruli, leukocyte infiltration, edema exudate, and necrosis in mice kidney exposed to GNPs. These findings align with previous studies highlighting the nephrotoxic effects of nanoparticles [22], [28], [65].

4.7.3. Lung tissue damage

Histological examinations revealed significant damage in the lung tissue of mice exposed to ZnO NPs and its various salts, including emphysema in air alveoli, peribronchiolar inflammatory cell infiltration, and dilatation/congestion of blood vessels (Fig. 10). The severity of these injuries was notably higher in the group exposed to ZnCl2 compared to others. Due to their small size, pollutants like ZnO NPs can easily enter the lungs, initiating biological and toxicological responses. The initial damage observed in lung tissues includes destruction of alveolar walls leading to emphysema. Oxidative stress is implicated as a potential mechanism underlying lung damage, where ZnO NPs and its salts induce excessive production of free radicals. These reactive oxygen species can bind to lipids, proteins, and DNA, exacerbating oxidative stress and causing tissue damage [34], [85].

Studies on various nanoparticles highlight their detrimental effects on lung tissues. Wu et al. [98] found that amine-polystyrene nanoplastics (APS-NPs) induce oxidative stress leading to destruction of lung alveolar walls in mice. Rashad and Abdelwahab [72] reported that titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs) cause thickening of interalveolar septa and increased macrophage presence in mouse lungs. Han et al. [43] observed in rats that copper oxide nanoparticles (CuO NPs) lead to alveolar wall thickening and necrosis, attributing these damages to oxidative stress triggered by CuO NPs. Similar findings from other studies corroborate these results [15], [60], emphasizing the role of oxidative stress in nanoparticle-induced lung damage.

4.7.4. Intestine tissue damage

Research on the effects of metals and nanoparticles on various tissues has extensively focused on organs like the liver and kidney, yet the impact on intestinal tissues has been relatively understudied. The intestine serves as a critical route for exposure to a wide range of toxic substances and is directly susceptible to their effects [17]. This study documents significant damage in the intestines of mice exposed to ZnO NPs and its various salts, including swelling and increased numbers of goblet cells, and elevated blood cell counts. Among these compounds, ZnCl2 causes notably severe damage compared to others. The increasing use of ZnO NPs and zinc salts raises concerns about heightened exposure for humans and other organisms. While zinc is essential in small amounts for enzyme and protein activation, elevated concentrations can be toxic to many species. Zinc's ability to penetrate cell membranes can lead to various histological damages within cells [52]. Studies by Sayadi et al. [78], [79] and Kharkan et al. [53] similarly report on nanoparticles and metal salts causing intestinal damage in black fish, including swelling and increased goblet cell numbers. The severity of damage varies among different compounds, with some salts like Fe (NO3)3 and NiCl2 causing more significant harm. These findings align with other research documenting similar impacts [77], [76].

5. Conclusions

ZnO NPs and its various salts cause significant changes in biochemical parameters, liver enzymes, hematology, and histopathology of mice compared to the control group. In light of these findings, urgent measures are needed to restrict the use of ZnO NPs and zinc salts, mitigate environmental contamination, and prioritize the cleanup of affected sites. Adopting stringent regulations and comprehensive risk assessments can help safeguard human health and ecosystem integrity against the growing threat posed by metal nanoparticles.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Kharkan Javad: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Resources, Investigation. Rezaei Mohammad Reza: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition. Yazdanshenas Mohammad Reza: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Handling Editor : Prof. L.H. Lash

Data Availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Abd El-Aziz Y.M., Hendam B.M., Al-Salmi F.A., Qahl S.H., Althubaiti E.H., Elsaid F.G., Abu Almaaty A.H. Ameliorative effect of pomegranate peel extract (PPE) on hepatotoxicity prompted by iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe2O3-NPs) in mice. Nanomater. (Basel) 2022;12(17):3074. doi: 10.3390/nano12173074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abd-Alsahib E.F., Faris S.A. Histopathological changes resulting from the effect of nano-graphene oxide on the liver in laboratory rats. Int J. Health Sci. 2022;6(S3):11208–11228. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdel-Daim M.M., Eissa I.A., Abdeen A., Abdel-Latif H.M., Ismail M., Dawood M.A., Hassan A.M. Lycopene and resveratrol ameliorate zinc oxide nanoparticles-induced oxidative stress in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. Environ. Toxicol. Pharm. 2019;69:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2019.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdel-Khalek A.A., Kadry M.A., Badran S.R., Marie M.A.S. Comparative toxicity of copper oxide bulk and nano particles in Nile tilapia; oreochromis niloticus: biochemical and oxidative stress. J. Basic Appl. Zool. 2015;72:43–57. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abd-Rabo M.M., Wahman L.F., El Hosary R., Ahmed I.S. High-fat diet induced alteration in lipid enzymes and inflammation in cardiac and brain tissues: assessment of the effects of atorvastatin-loaded nanoparticles. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2020;34(5) doi: 10.1002/jbt.22465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adeleke J.T., Theivasanthi T., Thiruppathi M., Swaminathan M., Akomolafe T., Alabi A.B. Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue by ZnO/NiFe2O4 nanoparticles. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018;455:195–200. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmad A., Pillai K.K., Najmi A.K., Ahmad S.J., Pal S.N., Balani D.K. Evaluation of hepatoprotective potential of jigrine post-treatment against thioacetamide induced hepatic damage. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002;79(1):35–41. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00349-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aldulaimi A.M.A., Al Jumaily A.A.I.H., Husain F.F. The effect of aqueous Urtica dioica extract in male rats exposed to copper sulfate poisoning. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021;735(1) IOP Publishing 735(2021):012-008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ale A., Rossi A.S., Bacchetta C., Gervasio S., de la Torre F.R., Cazenave J. Integrative assessment of silver nanoparticles toxicity in Prochilodus lineatus fish. Ecol. Indic. 2018;93:1190–1198. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ali A.A.M. Evaluation of some biological, biochemical, and hematological aspects in male albino rats after acute exposure to the nano-structured oxides of nickel and cobalt. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res Int. 2019;26(17):17407–17417. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-05093-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ali A.A.M., Mansour A.B., Attia S.A. The potential protective role of apigenin against oxidative damage induced by nickel oxide nanoparticles in liver and kidney of male Wistar rat, Rattus norvegicus. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res Int. 2021;28:27577–27592. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-12632-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alkaladi A., El-Deen N.A.N., Afifi M., Zinadah O.A.A. Hematological and biochemical investigations on the effect of vitamin E and C on Oreochromis niloticus exposed to zinc oxide nanoparticles. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2015;22(5):556–563. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amara S., Slama I.B., Mrad I., Rihane N., Khemissi W., El Mir L., Sakly M. Effects of zinc oxide nanoparticles and/or zinc chloride on biochemical parameters and mineral levels in rat liver and kidney. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2014;33(11):1150–1157. doi: 10.1177/0960327113510327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amjad S., Sharma A.K., Serajuddin M. Toxicity assessment of cypermethrin nanoparticles in Channa punctatus: behavioural response, micronuclei induction and enzyme alteration. Regul. Toxicol. Pharm. 2018;100:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2018.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bai K.J., Chuang K.J., Chen J.K., Hua H.E., Shen Y.L., Liao W.N., Chuang H.C. Investigation into the pulmonary inflammopathology of exposure to nickel oxide nanoparticles in mice. Nanomedicine. 2018;14(7):2329–2339. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bayram E.N., Al-Bakri N.A., Al-Shmgani H.S. Zinc chloride can mitigate the alterations in metallothionein and some apoptotic proteins induced by cadmium chloride in mice hepatocytes: a histological and immunohistochemical study. J. Toxicol. 2023;2023 doi: 10.1155/2023/2200539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bondarenko O., Juganson K., Ivask A., Kasemets K., Mortimer M., Kahru A. Toxicity of Ag, CuO and ZnO nanoparticles to selected environmentally relevant test organisms and mammalian cells in vitro: a critical review. Arch. Toxicol. 2013;87:1181–1200. doi: 10.1007/s00204-013-1079-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boran H., Şaffak S. Comparison of dissolved nickel and nickel nanoparticles toxicity in larval zebrafish in terms of gene expression and DNA damage. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2018;74:193–202. doi: 10.1007/s00244-017-0468-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Canli E.G., Atli G., Canli M. Response of the antioxidant enzymes of the erythrocyte and alterations in the serum biomarkers in rats following oral administration of nanoparticles. Environ. Toxicol. Pharm. 2017;50:145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2017.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Canli E.G., Dogan A., Canli M. Serum biomarker levels alter following nanoparticle (Al2O3, CuO, TiO2) exposures in freshwater fish (Oreochromis niloticus) Environ. Toxicol. Pharm. 2018;62:181–187. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2018.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Z., Han S., Zheng P., Zhou D., Zhou S., Jia G. Effect of oral exposure to titanium dioxide nanoparticles on lipid metabolism in Sprague-Dawley rats. Nanoscale. 2020;12(10):5973–5986. doi: 10.1039/c9nr10947a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Z., Meng H., Xing G., Chen C., Zhao Y., Jia G., Wan L. Acute toxicological effects of copper nanoparticles in vivo. Toxicol. Lett. 2006;163(2):109–120. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christian P., Kammer F., Baalousha M., Hofmann T. The ecotoxicology and chemistry of nanoparticles. Ecotoxicology. 2008;17(5):287–314. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clark N.J., Shaw B.J., Handy R.D. Low hazard of silver nanoparticles and silver nitrate to the haematopoietic system of rainbow trout. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018;152:121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dehkordi, R.A.F., Pasalar, S., Dehkordi, S.H., Karimi, B., 2023. The Combinatory Effects of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) and Thiamine on Skin of Alloxan-Induced Diabetic Mice; a Stereological and Biochemical Study. Res Sq.

- 26.Duncan J.R., Mahaffey E.A., Prasse K.W. Vol. 243. Iowa State University Press; Ames: 1994. (Veterinary laboratory medicine). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dunphy Guzmán K.A., Taylor M.R., Banfield J.F. Environmental risks of nanotechnology: national nanotechnology initiative funding 2000-2004. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006;40:1401–1407. doi: 10.1021/es0515708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.El-Masry T., Altwaijry N., Alotaibi B., Tousson E., Alboghdadly A., Saleh A. Chicory (Cichorium intybus L.) extract ameliorates hydroxyapatite nanoparticles induced kidney damage in rats. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020;33(3):1251–1260. [Google Scholar]

- 29.El-Naggar S.A., Ayyad E.S.K.T., Kandyel R.M., Salem M.L. Phoenix dactylifera seed extract ameliorates toxicity induced in mice by silver nanoparticles through antioxidant effects. Int. J. Cancer. Biomed. Res. 2021;5(4):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Esmaeillou M., Moharamnejad M., Hsankhani R., Tehrani A.A., Maadi H. Toxicity of ZnO nanoparticles in healthy adult mice. Environ. Toxicol. Pharm. 2013;35(1):67–71. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fadia B.S., Mokhtari-Soulimane N., Meriem B., Wacila N., Zouleykha B., Karima R., Thorat N.D. Histological injury to rat brain, liver, and kidneys by gold nanoparticles is dose-dependent. ACS Omega. 2022;7(24):20656–20665. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.2c00727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Famurewa A.C., Edeogu C.O., Offor F.I., Besong E.E., Akunna G.G., Maduagwuna E.K. Downregulation of redox imbalance and iNOS/NF-ĸB/caspase-3 signalling with zinc supplementation prevents urotoxicity of cyclophosphamide-induced hemorrhagic cystitis in rats. Life Sci. 2021;266 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farkas J., Farkas P., Hyde D. Liver and gastroenterology tests. In: Lee, M., 3rd (Ed.), Basic Skills in Interpreting Laboratory Data. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm., Bethesda. 2004:330–336. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Folkmann J.K., Risom L., Jacobsen N.R., Wallin H., Loft S., Møller P. Oxidatively damaged DNA in rats exposed by oral gavage to C60 fullerenes and single-walled carbon nanotubes. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009;117(5):703–708. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Friedlander S.K., Pui D.Y. Emerging issues in nanoparticle aerosol science and technology. J. Nanopart. Res. 2004;6(2):313–320. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gautam K., Pant V., Pradhan S., Pyakurel D., Bhandari B., Shrestha A. Blood lead levels in rag-pickers of Kathmandu and its association with hematological and biochemical parameters. EJIFCC. 2020;31(2):125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gautam R., Yang S., Maharjan A., J.o.J, Acharya M., Heo Y., Kim C. Prediction of skin sensitization potential of silver and zinc oxide nanoparticles through the human cell line activation test. Front Toxicol. 2021;3:26. doi: 10.3389/ftox.2021.649666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghafari F.H., Binde D.H., Jamali H., Hasanpour S., Mehdipour N., Rashidiyan G. The protective role of vitamin E on Oreochromis niloticus exposed to ZnONP. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017;144:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ghiasi F., Mirzargar S., Badakhshan H., Shamsi S. Lysozyme in Serum Leukocyte count and phagocytic index in cyprinus carpio under the Wintering Conditions. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2010;5(2):113–119. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gholamhosseini A., Hosseinzadeh S., Soltanian S., Banaee M., Sureda A., Rakhshaninejad M., Anbazpour H. Effect of dietary supplements of Artemisia dracunculus extract on the haemato-immunological and biochemical response, and growth performance of the rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Aquac. Res. 2021;52(5):2097–2109. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gross W.B., Siegel H.S. Evaluation of the heterophil/lymphocyte ratio as a measure of stress in chickens. Avian Dis. 1983:972–979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gulati S., Verma P. Distinguishing blood as normal or menstrual through instrumental analysis. Ann. Rom. Soc. Cell Biol. 2021:4499–4503. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han B., Pei Z., Shi L., Wang Q., Li C., Zhang B., Zhang R. TiO2 nanoparticles caused DNA damage in lung and extra-pulmonary organs through ROS-activated FOXO3a signaling pathway after intratracheal administration in rats. Int J. Nanomed. 2020:6279–6294. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S254969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang C.C., Aronstam R.S., Chen D.R., Huang Y.W. Oxidative stress, calcium homeostasis, and altered gene expression in human lung epithelial cells exposed to ZnO nanoparticles. Toxicol. Vitr. 2010;24(1):45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ibrahim K.E., Al-Mutary M.G., Bakhiet A.O., Khan H.A. Histopathology of the liver, kidney, and spleen of mice exposed to gold nanoparticles. Molecules. 2018;23(8):1848. doi: 10.3390/molecules23081848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Iftikhar M., Noureen A., Uzair M., Jabeen F., Abdel, Daim M., Cappello T. Perspectives of nanoparticles in male infertility: evidence for induced abnormalities in sperm production. Int J. Environ. Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):1758. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iluz-Freundlich D., Zhang M., Uhanova J., Minuk G.Y. The relative expression of hepatocellular and cholestatic liver enzymes in adult patients with liver disease. Ann. Hepatol. 2020;19(2):204–208. doi: 10.1016/j.aohep.2019.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johari S.A., Sarkheil M., Tayemeh M.B., Veisi S. Influence of salinity on the toxicity of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) and silver nitrate (AgNO3) in halophilic microalgae, Dunaliella salina. Chemosphere. 2018;209:156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.06.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Katzke V., Johnson T., Sookthai D., Hüsing A., Kühn T., Kaaks R. Circulating liver enzymes and risks of chronic diseases and mortality in the prospective EPIC-Heidelberg case-cohort study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(3) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaur A., Kaur K. Impact of nickel-chrome electroplating effluent on the protein and cholesterol contents of blood plasma of Channa punctatus(Bl.) during different phases of the reproductive cycle. J. Environ. Biol. 2006;27(2):241–245. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaviani E.F., Naeemi A.S., Salehzadeh A. Influence of copper oxide nanoparticle on hematology and plasma biochemistry of Caspian trout (Salmo trutta caspius), following acute and chronic exposure. Pollution. 2019;5(1):225–234. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Keller A.A., Wang H., Zhou D., Lenihan H.S., Cherr G., Cardinale B.J., J.i.Z Stability and aggregation of metal oxide nanoparticles in natural aqueous matrices. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010;44(6):1962–1967. doi: 10.1021/es902987d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kharkan J., Sayadi M.H., Hajiani M., Rezaei M.R., Savabieasfahani M. Toxicity of nickel oxide nanoparticles in Capoeta fusca, using bioaccumulation, depuration, and histopathological changes. Glob. J. Environ. Sci. Manag. 2023;9(3):427–444. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim J.H., Kang J.C. The selenium accumulation and its effect on growth, and haematological parameters in red sea bream, Pagrus major, exposed to waterborne selenium. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2014;104:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krishnaiah D., Khiari M., Klibet F., Kechrid Z. In Toxicology. Academic Press; 2021. Oxidative stress toxicity effect of potential metal nanoparticles on human cells; pp. 107–117. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kumar N., Krishnani K.K., Singh N.P. Comparative study of selenium and selenium nanoparticles with reference to acute toxicity, biochemical attributes, and histopathological response in fish. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018;25:8914–8927. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-1165-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Massarsky A., Abraham R., Nguyen K.C., Rippstein P., Tayabali A.F., Trudeau V.L., Moon T.W. Nanosilver cytotoxicity in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) erythrocytes and hepatocytes. Comp. Biochem Physiol. C. Toxicol. Pharm. 2014;159:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matouke M.M., Sanusi H.M., Eneojo A.S. Interaction of copper with titanium dioxide nanoparticles induced hematological and biochemical effects in Clarias gariepinus. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res Int. 2021;28:67646–67656. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-15148-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mirjani R., Faramarzi M.A., Sharifzadeh M., Setayesh N., Khoshayand M.R., Shahverdi A.R. Biosynthesis of tellurium nanoparticles by Lactobacillus plantarum and the effect of nanoparticle-enriched probiotics on the lipid profiles of mice. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2015;9(5):300–305. doi: 10.1049/iet-nbt.2014.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mo Y., Jiang M., Zhang Y., Wan R., Li J., Zhong C.J., Zhang Q. Comparative mouse lung injury by nickel nanoparticles with differential surface modification. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2019;17(1):1–18. doi: 10.1186/s12951-018-0436-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Molina R., Moreno I., Pichardo S., Jos A., Moyano R., Monterde J.G., Cameán A. Acid and alkaline phosphatase activities and pathological changes induced in Tilapia fish (Oreochromis sp.) exposed subchronically to microcystins from toxic cyanobacterial blooms under laboratory conditions. Toxicon. 2005;46(7):725–735. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Naguib M., Mahmoud U.M., Mekkawy I.A., Sayed A.E.D.H. Hepatotoxic effects of silver nanoparticles on Clarias gariepinus; biochemical, histopathological, and histochemical studies. Toxicol. Rep. 2020;7:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2020.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Namita N., Ranjan D. A cross-sectional study of association between hemoglobin level and body mass index among adolescent age group. Natl. J. Physiol. Pharm. Pharm. 2019;9(8):746–750. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nel A.E., Mädler L., Velegol D., Xia T., Hoek E.M. V; Somasundaran P.; Klaessig F.; Castranova V.; Thompson M. Understanding Biophysicochemical Interactions at the Nano-Bio Interface. Nat. Mater. 2009;8:543–557. doi: 10.1038/nmat2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Patlolla A.K., Rondalph J., Tchounwou P.B. Biochemical and histopathological evaluation of graphene oxide in Sprague-Dawley rats. Austin J. Environ. Toxicol. 2017;3(1):1021. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pierozan P., Jernerén F., Ransome Y., Karlsson O. The choice of euthanasia method affects metabolic serum biomarkers. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2017;121(2):113–118. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pleskova S.N., Gornostaeva E.E., Kryukov R.N., Boryakov A.V., Zubkov S.Y. Changes in the architectonics and morphometric characteristics of erythocytes under the influence of magnetite nanoparticles. Cell Tissue Biol. 2018;12:127–134. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pujalté I., Passagne I., Brouillaud B., Tréguer M., Durand E., Ohayon-Courtès C., L'Azou B. Cytotoxicity and oxidative stress induced by different metallic nanoparticles on human kidney cells. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2011;8:1–16. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-8-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Qin S., Wang J., Yuan H., He J., Luan S., Deng Y. Liver function indicators and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: a bidirectional mendelian randomization study. Front. Genet. 2024;14 doi: 10.3389/fgene.2023.1260352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rahdar A., Hajinezhad M.R., Bilal M., Askari F., Kyzas G.Z. Behavioral effects of zinc oxide nanoparticles on the brain of rats. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2020;119 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ramadan A.G., Yassein A.A., Eissa E.A., Mahmoud M.S., Hassan G.M. Biochemical and histopathological alterations induced by subchronic exposure to zinc oxide nanoparticle in male rats and assessment of its genotoxicicty. J. Umm Al-Qura Univ. Appl. Sci. 2022;8(1-2):41–49. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rashad W.A., Abdelwahab O.A. Toxic effect of titanium dioxide nanoparticles on the lung of adult male albino rat and possible protective role of β-carotene: light and electron microscopic study. Egypt. J. Histol. 2021;44(2):425–435. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Salamanca-Buentello F., Daar A.S. Nanotechnology, equity and global health. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021;16(4):358–361. doi: 10.1038/s41565-021-00899-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Samim A.R., Vaseem H. Assessment of the potential threat of nickel (II) oxide nanoparticles to fish Heteropneustes fossilis associated with the changes in haematological, biochemical and enzymological parameters. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res Int. 2021;28(39):54630–54646. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-14451-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Santos C.S., Gabriel B., Blanchy M., Menes O., García D., Blanco M., Neto V. Industrial applications of nanoparticles–a prospective overview. Mater. Today Proc. 2015;2(1):456–465. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sayadi M.H., Kharkan J., Shekari H., Rezaei A. Acute toxicity and histopathological changes in gill and intestine of Gambusia holbrooki Girard, 1859 fish exposed to paraquat at different pH, hardness and temperatures. J. Nat. Environ. 2023;76(1):133–147. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sayadi M.H., Kharkan J. Investigating the histological damage of different heavy metals on aqueduct fish (Capoeta fusca) Aquac. Sci. 2022;10(2):149–161. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sayadi M.H., Mansouri B., Shahri E., Tyler C.R., Shekari H., Kharkan J. Exposure effects of iron oxide nanoparticles and iron salts in blackfish (Capoeta fusca): Acute toxicity, bioaccumulation, depuration, and tissue histopathology. Chemosphere. 2020;247 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.125900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sayadi M.H., Pavlaki M.D., Loureiro S., Martins R., Tyler C.R., Mansouri B., Shekari H. Co-exposure of zinc oxide nanoparticles and multi-layer graphenes in blackfish (Capoeta fusca): evaluation of lethal, behavioural, and histopathological effects. Ecotoxicology. 2022;31(3):425–439. doi: 10.1007/s10646-022-02521-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sayadi M.H., Pavlaki M.D., Martins R., Mansouri B., Tyler C.R., Kharkan J., Shekari H. Bioaccumulation and toxicokinetics of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) co-exposed with graphene nanosheets (GNs) in the blackfish (Capoeta fusca) Chemosphere. 2021;269 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.128689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sayed A.E.D.H., Kataoka C., Oda S., Kashiwada S., Mitani H. Sensitivity of medaka (Oryzias latipes) to 4-nonylphenol subacute exposure; erythrocyte alterations and apoptosis. Environ. Toxicol. Pharm. 2018;58:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2017.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shabrangharehdasht M., Mirvaghefi A., Farahmand H. Effects of nanosilver on hematologic, histologic and molecular parameters of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Aquat. Toxicol. 2020;225 doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2020.105549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shaluei F., Hedayati A., Jahanbakhshi A., Kolangi H., Fotovat M. Effect of subacute exposure to silver nanoparticle on some hematological and plasma biochemical indices in silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2013;32(12):1270–1277. doi: 10.1177/0960327113485258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shamsi A., Mohammad T., Anwar S., Alajmi M.F., Hussain A., Hassan M.I., Islam A. Probing the interaction of Rivastigmine Tartrate, an important Alzheimer's drug, with serum albumin: attempting treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Int J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;148:533–542. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.01.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sharififar F., Moshafi M.H., Mansouri S.H., Khodashenas M., Khoshnoodi M. In vitro evaluation of antibacterial and antioxidant activities of the essential oil and methanol extract of endemic Zataria multiflora Boiss. Food Control. 2007;18(7):800–805. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sibiya A., Jeyavani J., Santhanam P., Preetham E., Freitas R., Vaseeharan B. Comparative evaluation on the toxic effect of silver (Ag) and zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles on different trophic levels in aquatic ecosystems: A review. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2022;42(12):1890–1900. doi: 10.1002/jat.4310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Soliman H.A., Hamed M., Sayed A.E.D.H. Investigating the effects of copper sulfate and copper oxide nanoparticles in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) using multiple biomarkers: the prophylactic role of Spirulina. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res Int. 2021;28:30046–30057. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-12859-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sookoian S., Pirola C.J. Alanine and aspartate aminotransferase and glutamine-cycling pathway: their roles in pathogenesis of metabolic syndrome. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012;18(29):3775–3781. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i29.3775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Srivastav A.K., Kumar M., Ansari N.G., Jain A.K., Shankar J., Arjaria N., Singh D. A comprehensive toxicity study of zinc oxide nanoparticles versus their bulk in Wistar rats: toxicity study of zinc oxide nanoparticles. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2016;35(12):1286–1304. doi: 10.1177/0960327116629530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tekuri S.K., Bassaiahgari P., Gali Y., Amuru S.R., Pabbaraju N. Determination of median lethal dose of zinc chloride in wistar rat. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2021;9(3):393–399. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Thomas L.D., Hodgson S., Nieuwenhuijsen M., Jarup L. Early kidney damage in a population exposed to cadmium and other heavy metals. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009;117(2):181–184. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Trindade L.G., Minervino G.B., Trench A.B., Carvalho M.H., Assis M., Li M.S., Longo E. Influence of ionic liquid on the photoelectrochemical properties of ZnO particles. Ceram. Int. 2018;44(9):10393–10401. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Vali S., Mohammadi G., Tavabe K.R., Moghadas F., Naserabad S.S. The effects of silver nanoparticles (Ag-NPs) sublethal concentrations on common carp (Cyprinus carpio): Bioaccumulation, hematology, serum biochemistry and immunology, antioxidant enzymes, and skin mucosal responses. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020;194:110–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Vaseem H., Banerjee T.K. Toxicity analysis of effluent released during recovery of metals from polymetallic sea nodules using fish haematological parameters. Funct. Ecosys. 2012:249–260. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Vidya P.V., Chitra K.C. Evaluation of genetic damage in exposed to selected nanoparticles by using micronucleus and comet bioassays. Ribarstvo. 2018;76(3):115–124. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wang C., Cheng K., Zhou L., He J., Zheng X., Zhang L., Wang T. Evaluation of long-term toxicity of oral zinc oxide nanoparticles and zinc sulfate in mice. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2017;178:276–282. doi: 10.1007/s12011-017-0934-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Watanabe M., Hashimoto K., Ishii Y., Takimoto H.R., Nikaido Y., Sasaki N. Assessment of thiamylal sodium as a euthanasia drug in mice. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2024;86(5):480–484. doi: 10.1292/jvms.24-0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wu Y., Yao Y., Bai H., Shimizu K., Li R., Zhang C. Investigation of pulmonary toxicity evaluation on mice exposed to polystyrene nanoplastics: The potential protective role of the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine. Sci. Total Environ. 2023;855 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Xiao S., Mao L., Xiao J., Wu Y., Liu H. Selenium nanoparticles inhibit the formation of atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E deficient mice by alleviating hyperlipidemia and oxidative stress. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021;902 doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.174120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zinicovscaia I., Pavlov S.S., Frontasyeva M.V., Ivlieva A.L., Petritskaya E.N., Rogatkin D.A., Demin V.A. Accumulation of silver nanoparticles in mice tissues studied by neutron activation analysis. J. Radio. Nucl. Chem. 2018;318:985–989. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.