Abstract

Genetic variations of signaling modulator protein LNK (also called SH2B3) are associated with relatively mild myeloproliferative phenotypes in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN). However, these variations can induce more severe MPN disease and even leukemic transformation when co-existing with other driver mutations. In addition to the most prevalent driver mutation JAK2V617F, LNK mutations have been clinically identified in patients harboring CBL inactivation mutations, but its significance remains unclear. Here, using a transgenic mouse model, we demonstrated that mice with the loss of both Lnk and Cbl exhibited severe splenomegaly, extramedullary hematopoiesis and exacerbated myeloproliferative characteristics. Moreover, a population of Mac1+ myeloid cells expressed c-Kit in aged mice. Mechanistically, we discovered that LNK could pull down multiple regulatory subunits of the proteosome. Further analysis confirmed a positive role of LNK in regulating proteasome activity, independent of its well-established function in signaling transduction. Thus, our work reveals a novel function of LNK in coordinating with the E3 ligase CBL to regulate myeloid malignancies.

Keywords: SH2B3, CBL, MPN, Leukemia, Proteasome

Introduction

Throughout life, a small population of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in the bone marrow continously produces and replenishes blood cells. The coordinated cytokine-activated signaling pathway plays a pivotal role in controlling the balance between HSC self-renewal and differentiation. JAK2 is a central tyrosine kinase crucial for transmitting signals from various cytokines, such as thrombopoietin (Tpo), erythropoietin (Epo), and GM-CSF, to their respective receptors, thereby initiating a cascade of signaling events in different types of hematopoietic cells [1]. Meanwhile, a series of negative regulators within cell ensures appropriate signaling amplitude and duration, thereby preventing oncogenic transformation.

LNK (also known as SH2B3) is a well-known adaptor protein that constrains JAK2 signaling derived from a variety of cytokines in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) [2–4]. LNK, along with the other two members APS and SH2B1 comprises the SH2B family of adaptor proteins, that contain a dimerization domain, a proline-rich motif, a central Pleckstrin homology (PH) domain, a Src homology 2 (SH2) domain and several phosphorylation sites. LNK regulates the development of multiple blood cells through lineage-specific cytokines. Lnk-deficient mice exhibit a dramatic increase in white blood cells and platelets in the peripheral blood [2, 5], as well as immature B cells and erythroid progenitors in the bone marrow and spleen [3, 6, 7]. More importantly, Lnk deficiency leads to a 10–15 fold increase in the number of HSCs with superior transplantable ability [4, 8]. These phenotypes observed in Lnk-deficient mice are largely attributable to its inhibitory role in regulating JAK2 activation in response to cytokines.

Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) represent a heterogenous group of HSC diseases, characterized by overproduction of mature myeloid cells. Many MPNs result from uncontrolled signal transduction pathway, exemplified by the constitutively active BCR-ABL fusion protein in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and JAK2 activating mutation V617F in polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET), and myelofibrosis (MF). As a key negative regulator of JAK2 signaling, Lnk loss alone does not induce myeloproliferative diseases in young mice, although aged mice develop a CML-like MPN without blast crisis. However, in the context of JAK2V617F mutation, Lnk deficiency renders HSCs hypersensitive to cytokine stimulation and exacerbates JAK2V617F-induced MPN [9]. Consistent with the observations in mice, LNK mutations have been reported in many subtypes of MPN patients [10], and some mutations tend to co-exist with JAK2V617F as well as other driver mutations [11], highlighting the clinical relevance of LNK activity to MPN pathobiology.

Casitas B lineage lymphoma (CBL) proteins are a conserved family of RING finger (RF) E3 ubiquitin ligases, known for ubiquitinating receptor and non-receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs). This process is crucial in the development of hematopoietic and immune cells [12]. Clinically, CBL mutations are found in a wide variety of myeloid neoplasms, predominantly located in the RF and linker regions, which disrupt the E3 ligase activity and lead to the overactivation of signaling pathways [13]. Interestingly, LNK loss-of-function mutations have been reported to co-exist with CBL E3-dead mutations in both CMML and JMML patients [14, 15], but the functional and clinical significance of this co-occurrence has not been investigated. Moreover, Lnk deficiency facilitates the initiation of myeloproliferative dysplasia (MPD) in a mouse model in cooperation with BCR/ABL fusion gene, which does not directly interact with LNK [9]. Additionally, Lnk deficiency can fully restore defective HSC function in Fancd2−/− mice, a process only partially dependent on cytokine/JAK2 signaling [16]. These observations suggest that LNK may have other functions independent of CBL/JAK2 signaling axis.

Emerging evidence suggests LNK/SH2B3 as an important suppressor of hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) disease. A number of LNK inactivation mutations have been identified in many subtypes of MPNs [10], with some mutations co-existing with CBL E3-dead mutations (CBLmut) in patients. We previously showed that LNK recruits JAK2 to CBL family E3 ligases in response to cytokine stimulation, a process required for JAK2 ubiquitination and subsequent degradation in proteasomes [17]. In this study, using a Cbl;Lnk double knockout (DKO) mouse model, we investigated the pathological role of Lnk in constraining myeloproliferative diseases induced by Cbl loss and its potential novel function independent of JAK2 signaling. Remarkably, we found that Cbl;Lnk DKO mice exhibited an expanded pool of HSCs in the spleen, splenomegaly and increased number of circulating white blood cell counts in young adult mice compared to Cbl single KO mice, with this phenotype persisting in aged mice. HSCs from the bone marrow of young DKO mice demonstrated superior repopulation ability in recipient mice. Furthermore, we identified a new role of LNK in controlling protein homeostasis through the modulation of proteasome activity. Thus, our data suggest that LNK and CBL have cooperative functions in the pathobiology of myeloproliferative diseases.

Materials and Methods

Mice and Cell Lines

Germline Lnk−/− mice were kindly provided by Tony Pawson and Laura Velazquez (Samuel Lunenfeld Research Institute, Toronto, Ontario, Canada). Cbl−/− mice were originally from Wallace Y. Langdon (University of Western Austrilia, Crawley, Australia). Cbl;Lnk double knockout (DKO) mice were generated by crossing Cbl−/− and Lnk−/− mice. CD45.1-positive SJL mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory, and CD45.1/2-double positive F1 mice were obtained by crossing C57/BL6 with SJL mice. Both male and female mice were used indiscriminately in this study.

Human erythroleukemia cell line TF-1 was cultured in RPMI1640 media with 10% calf serum and 2 ng/mL human GM-CSF (PeproTech). TF-1 cells with Lnk knockout or knockdown were generated as previously described [17].

Complete Blood Count (CBC) and Flow Cytometry

Peripheral blood was drawn retro-orbitally into EDTA-coated tubes from mice of different genotypes at the indicated ages. Complete blood counts (CBC) were analyzed using a Hemavet950 (Drew Scientific Inc).

For lineage cell staining, peripheral blood was lysed with RBC lysis buffer (0.8% NH4Cl, 10uM EDTA, pH7.4–7.6) for 10 min at 4 °C to get rid of red blood cells. The resultant mononuclear cells (MNCs) were blocked with Fc blocker for 5 min at 4 °C, followed by staining with a panel of fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies: anti-Gr1 (RB-8C5), anti-Mac1 (M1/70), anti-CD3 (145-2c11) and anti-B220 (RA3-6B2) for 30 min at 4 °C. After washing with flow buffer (0.5% BSA, 1 mM EDTA in PBS), cells were resuspended in a propidium iodide (PI)- or DAPI-containing flow buffer and subjected to flow cytometry analysis. To distinguish donor, competitor and recipient cells, anti-CD45.2 (104) and anti-CD45.1 (A20) were included in the staining panel. All the above antibodies were purchased from Invitrogen.

The staining of HSPC subpopulations was performed as previously described [18]. Briefly, after a quick lysis of red blood cells with RBC lysis buffer for 1 min, total BM or spleen cells were stained with biotin-conjugated mixture of antibodies against lineage markers, including Gr1 (RB6–8C5), Mac1 (M1/70), B220 (RA3–6B2), CD19 (eBio1D3), Ter119 (TER-119), CD5 (53–7.3), CD4 (GK1.5) and CD8 (53–6.7). These lineage markers were combined with antibodies against stem cell surface markers, including APC-Cy7-c-Kit (2B8), PerCP-Cy5.5-Sca1 (E13–161.7 or D7), FITC-CD48 (HM48–1), PE-Cy7-CD150 (TC15–12F12.2), APC-CD34 (RAM34), and PE–Flk2 (A2F10.1) for 30 min on ice. Biotin-conjugated antibodies were further stained with streptavidin-PE-TexasRed (Invitrogen SA1017) for 30 min on ice. Samples were resuspended in DAPI-containing flow buffer, and analyzed using a BD FACS Fortessa flow cytometer. Different HSPC subpopulations were defined as follows: long-term stem cells (LT-HSCs, Lin−Sca1+c-Kit+Flk2−CD150+CD48−), short-term stem cells (ST-HSCs, Flk2−CD150−CD48−LSK), multiple potent progenitors (megakaryocyte/erythroid-biased MPP2, Flk2−CD150+CD48+ LSK; myeloid-biased MPP3, Flk2−CD150−CD48+ LSK; lymphoid-biased MPP4, Flk2+CD150−LSK) [19].

Competitive Bone Marrow Transplantation (BMT)

1 million of total BM cells from 2-month-old mice were harvested from Cbl−/− or Cbl;Lnk DKO (donor cells, CD45.2) mice were mixed with the same number of BM cells from SJL WT mice (competitor cells, CD45.1), and injected into lethally irradiated F1 WT mice (recipient mice, CD45.1/2). Donor cell percentage or donor-derived lineage cell percentage was flow cytometrically examined every four weeks post-transplantation for 4 months. After 16 weeks, the number of donor-derived HSCs in spleen was calculated.

Tandem Immunoaffinity Purification

TF-1/BCR-ABL cells stably expressing FH (Flag/HA)-double tagged Lnk were used for tandem immunoaffinity purification, with cells expressing pOZ-FH empty vector as a control. Five hundred million of cells for each group were harvested and washed with cold PBS. Since Lnk is a cytoplasmic protein, the nuclear fraction was removed using hypotonic buffer and homogenization method. Specifically, we added five volumes of hypotonic buffer (10 mM Tris, pH7.4, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 3uM Na3VO4, 2uM NaF, 1 mM EDTA, 1uM PMSF and proteinase cocktail inhibitor (Roche)) and resuspended the cell pellet carefully to wash off any residual PBS. After centrifugation, the cells were resuspended again in two volumes of hypotonic buffer for 10 min on ice to allow cells to swell. The swollen cells were then homogenized with a Dounce homogenizer. For complete cell lysis, we added 11% of 10X lysis buffer (100 mM Tris pH7.4, 1.2 M NaCl, 2% NP-40, 10% Glycerol, 3uM Na3VO4, 2uM NaF, 1 mM EDTA, 1uM PMSF and proteinase cocktail inhibitor (Roche)) dropwise while vortexing, followed by centrifugation at 30, 000 rpm for 1 h at 4 °C. The lysate was then cleared with a 0.2um syringe filter to remove the lipid layer.

For the initial round of immunoprecipitation with the Flag antibody, 200uL Flag-M2 (Sigma) beads were washed with IP buffer (10 mM Tris pH7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 10% Glycerol, 3uM Na3VO4, 2uM NaF, 1 mM EDTA, 1uM PMSF and proteinase cocktail inhibitor (Roche)) twice and then added to the lysate. The binding was maintained at 4 °C for 4 h with constant rocking. Following three washes of the beads with IP buffe, 200uL of 3XFlag peptide was added to the beads at a final concentration of 100ug/mL in IP buffer, and the mixture was incubated at 4 °C for 30 min. “FLAG elute 1” was obtained by a spin-down for 1 min at 4,000 rpm. The elution was repeated with the 3XFlag peptide to obtain “FLAG elute 2”. The beads were retained for SDS-PAGE analysis to assess elution efficiency.

For the subsequent round of immunoprecipitation with the HA antibody, the two “FLAG elutes” were combined, the pre-washed HA-3F10 beads were added for an overnight incubation at 4 °C. Following three washes with IP buffer, the beads were treated with 50uL of 0.1 M pH2.5 glycine and incubated at room temperature for 15 min with occasional mixing. Subsequently, 1/10 volume of 1 M pH8.0 Tris was added to neutralize the glycine. The resulting supernatant was then transferred to a new tube and utilized for mass spectrometry analysis.

Quantitative Proteomics with Stable Isotope Labeling by/with Amino Acids in Cell Culture (SILAC)

The impact of Lnk loss on total proteomics was investigated by comparing the proteomics of TF-1 control cells with TF-1/Lnk KO cells using mass spectrometry. Specifically, TF-1 control cells were cultured in the light media consisting of 225 mL SILAC RPMI1640 (88365 ThermoFisher), 25 mL dialyzed FCS, 2.5 mL Pen/Strep, 2.5 mL Glumax, 2.5 mL sodium pyruvate (11360070, ThermoFisher), 2.5 mL MEM NEAA (11140050, Thermo), 5 mL HEPES (15630080, ThermoFisher), 2uL Betamercaptoethanol, 250uL lysine (K0, L8662, Sigma), and 250uL arginine (R0, A8094, Sigma)). Lnk KO cells were cultured in the heavy-labelled media, with a similar composition to the light media except that K0 and R0 were substituted with C13-isotope labelled lysine (K8, 89987, ThermoFisher) and arginine (R10, 88210, ThermoFisher), respectively. Both cell lines were cultured and expanded simultaneously. By day10, the heavy-labelled cells were checked for at least 90% incorporation of C13 lysine and arginine. The cells were harvested for mass spectrometry analysis.

In Vivo Protein Synthesis Rate by OP-Puro (O-propargyl-puromycin) Assay

The in vivo measurement of protein synthesis rate using OP-Puro assay was conducted following a previously published protocol [20]. Specifically, OP-Puro (Cat# HY-15680, MCE; pH6.4–6.6 dissolved in PBS) was intraperitoneally administered at a dose of 50 mg/kg body weight to WT or Lnk KO mice. The mice were euthanized 1 h after drug administration to allow for OP-Puro incorporation into translating peptides. Total BM cells were harvested and live stained with a surface marker panel for HSPCs. The cells were then fixed with BD Cytofix solution for 20 min at 4 °C, followed by washing with BD Perm/Wash buffer. After permeabilization with BD Cytoperm Plus solution, the cells were refixed in Cytofix solution for an additional 5 min. The incorporated OP-puro in the cells was detected using Click-iT puls OPP Alexa Fluor 488 kit (Cat#C10458, Invitrogen), which involves an azide-alkyne reaction, following the manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequently, the cells were resuspended in flow buffer and analyzed on a BD Fortessa cytometer.

Measurement of Proteasome Activity

The activity of the proteasome was assessed using Proteasome-Glo assay systems according to the manufacturer’s manuals. Briefly, TF1 cells with LNK knockdown (shLNK#1 and #2) as well as shLuc control cells were lysed with 1% NP-40 lysis buffer (without protease inhibitors) on ice for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 13, 000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. Protein concentration was determined by the BCA method. A total of 6ug of protein, diluted in 50uL HEPES buffer, was mixed with an equal volume of Proteasome-Glo reagent in a white 96-well plate. The mixture was incubated in the dark for 10–30 min, and luminescence was then measured using a plate-reading luminometer. The luminescent substrate Suc-LLVY-Glo™ (Cat.# G8621, Promega) was employed to detect the chymotrypsin-like activity of proteasomes, while Z-nLPnLD-Glo™ (Cat.# G8641, Promega) was used for Caspase-like activity. The proteasome inhibitor MG132 (10 μM) served as a negative control to inhibit overall proteolytic activity of proteasomes.

Data Analysis

Statistical analysis for complete blood count assay was conducted using unpaired two-tailed student’s t test in Excel. Flow cytometric data of BM, spleen or peripheral blood in both primary and transplanted mice were analyzed using FlowJo software and quantified by GraphPad Prism. Error bars represent mean ± SEM. The value of “n” for the number of repeats in each experiment was specified in the figure legends. Statistical significance was determined as follows: ns, not significant; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Results

Combined Loss of Cbl and Lnk in Mice Leads to a Myeloproliferative Phenotype

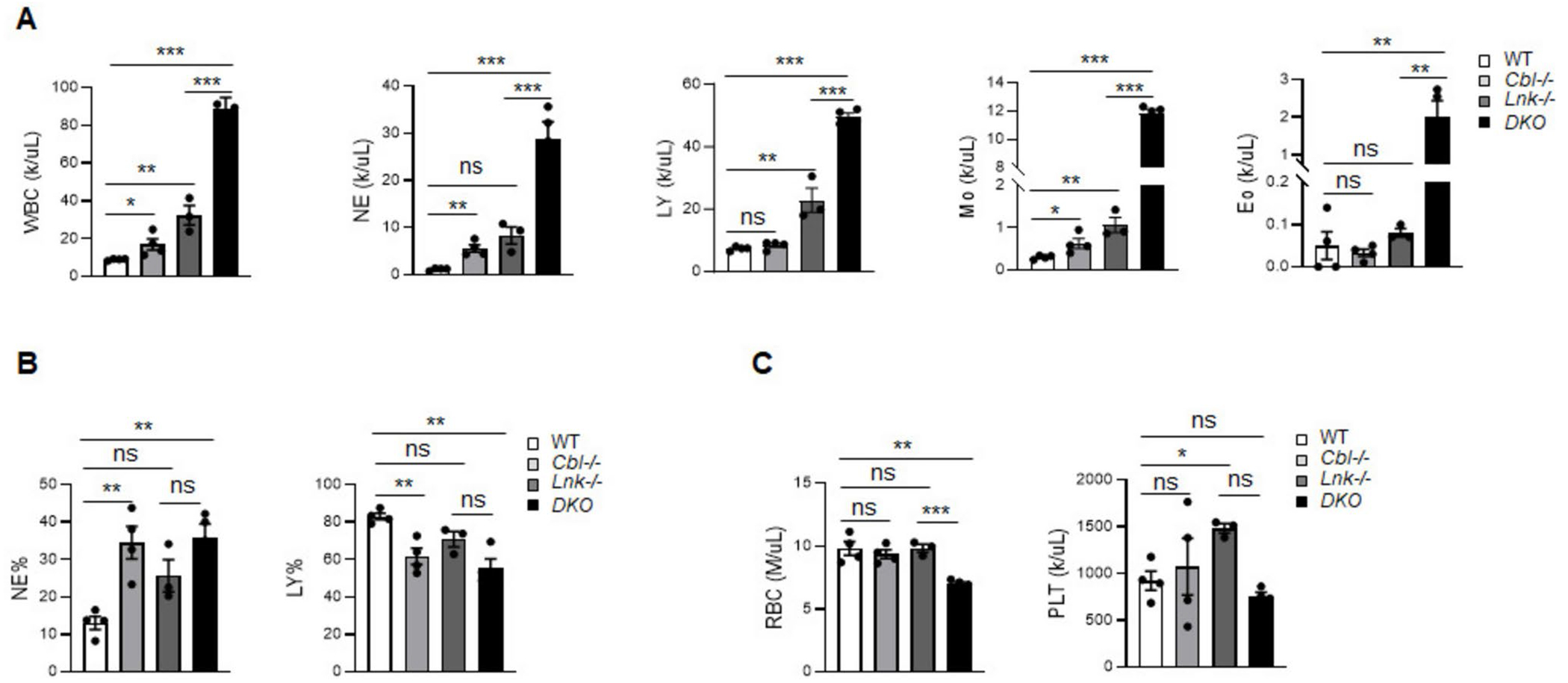

To investigate the functional role of LNK in the pathology of CBLmut MPN, we generated a germline double knockout mouse model deficient in both Cbl and Lnk genes (referred to as Cbl;Lnk DKO hereafter). As previously reported [21], Cbl−/− mice at a young age of 2–3 months exhibited almost comparable complete blood count parameters in the periphery blood in comparison to wild type (WT) mice (Supplementary Table 1). By 5 months of age, these mice showed a significant increase in circulating WBC, neutrophils and monocytes, but not in lymphocytes or red blood cells (RBC) (Fig. 1 A-C), indicative of a mild myeloproliferative phenotype. In stark contrast, Cbl;Lnk DKO mice exhibited significant illness, characterized by hunched posture, scratched skin and substantial weight loss by 5 to 9 months of age. Further analysis showed that these mice displayed marked increases in WBC, neutrophils, monocytes, eosinophils as well as lymphocytes compared to Cbl−/− mice (Supplementary Table 1), with these changes becoming more pronounced by 5 months (Fig. 1A, B), when RBC levels were dramatically decreased (Fig. 1C). Together, these observations indicate that DKO mice succumb to a severe MPN disease in the middle age, highlighting the cooperative pathological effects of Lnk and Cbl loss in MPN.

Fig. 1.

Cbl;Lnk DKO mice develop a severe myeloproliferative disease. A Complete blood count analysis of the periphery blood (PB) of the indicated mice. B Percentage of neutrophils (NE) and lymphocytes in PB of the indicated mice. C Red blood cell (RBC) and platelet count in PB of the indicated mice. Data from A-C were obtained from 5-month-old mice (WT, n = 4; Cbl−/−, n = 3; Lnk−/−, n = 4; DKO, n = 4). Each symbol represents a mouse. Error bars represent SE. p values were calculated by unpaired student’s t-test. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns, not significant

Aged Cbl;Lnk DKO Mice are Predisposed to Malignant Transformation

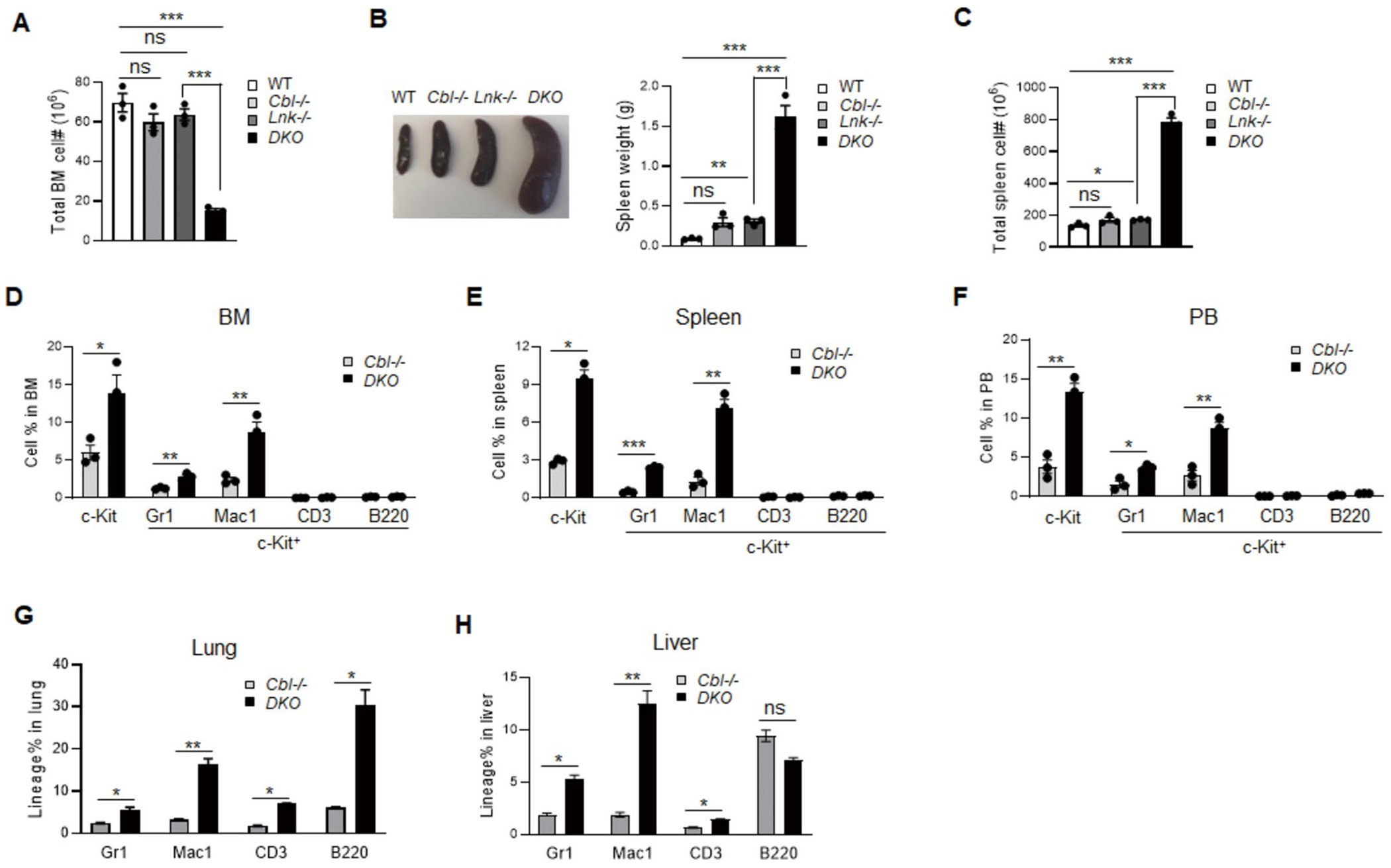

We next characterized the bone marrow (BM) and spleen of Cbl;Lnk DKO mice at 5 months of age. While Cbl and Lnk single knockout mice showed similar total BM cell numbers to WT mice, DKO mice exhibited a significant decrease in BM cell numbers (Fig. 2A). In contrast, DKO mice exhibited pronounced splenomegaly, with spleens over 10 times larger and containing significantly more cells (Fig. 2B, C). These observations indicate a severe occurrence of extramedullary hematopoiesis in the DKO mice.

Fig. 2.

Leukemia transformation in old Cbl;Lnk DKO mice. A Total BM cellularity in the indicated mice. B Left panel shows the representative image of spleens from the indicated mice; Right panel is the statistical data of spleen weight. C Statistics of total cell numbers in the spleen from indicated mice. D-F Percentage of lineage cells in the BM (D), spleen (E), and PB (F) as analyzed by flow cytometry. G, H Percentage of lineage cells in the lung (G) and liver (H) as analyzed by flow cytometry. All data from A-H were obtained from 5-month-old mice (n = 3 for each genotype). Each symbol represents a mouse. Error bars represent SE. p values were calculated by unpaired student’s t-test. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns, not significant

Since we have extensively characterized the normal and diseased hematopoiesis in Lnk−/− mice [4, 7, 9, 17, 22], we focus on DKO mice along with Cbl−/− mice as a control in the following studies. By comparing the lineage blood cell composition between DKO and Cbl−/− mice, we found that DKO mice exhibited a significant increase in the percentage of Gr1+ and Mac1+ cells in the BM, spleen and PB. Importantly, an elevated population of c-Kit+ cells were detected in DKO mice, with a large portion being Mac1-positive and a smaller portion being Gr1-positive. Notably, no c-Kit+ cells were found in lymphocytes (Fig. 2D-F). In addition, we observed extensive infiltration of lineage cells, including some lymphocytes into non-hematopoietic organs such as the lung and liver in DKO mice, but not in Cbl−/− mice (Fig. 2G, H). These data indicate that Cbl;Lnk DKO mice suffer from a more severe MPN phenotype, along with a tendency towards malignant transformation.

MPN Phenotype Induced by Cbl and Lnk Deficiency are Transferable in Mice

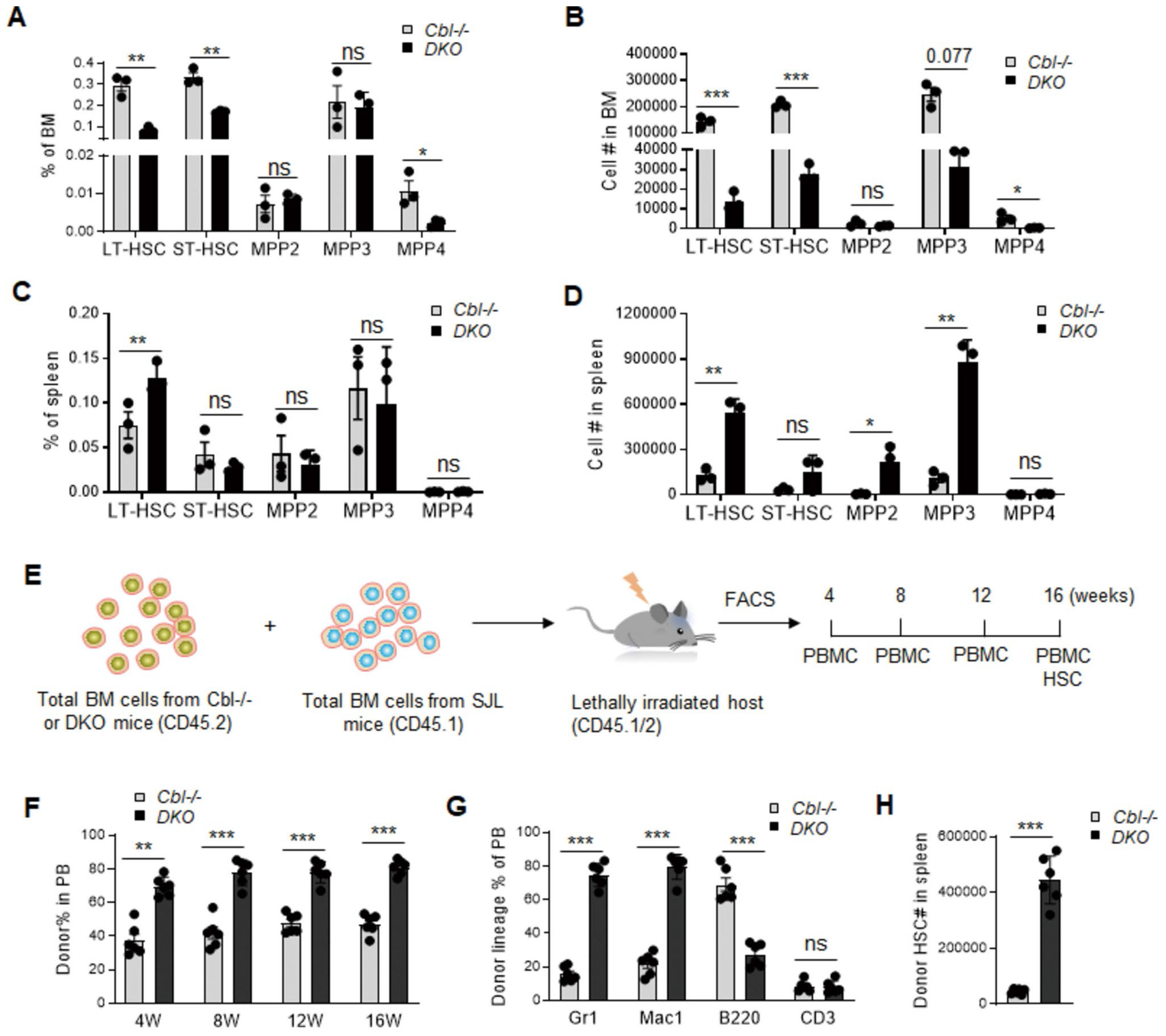

Both MPN and leukemia arise from unrestrained proliferation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs). Given that Cbl; Lnk DKO mice have been confirmed to suffer from MPN, we compared the frequency and number of HSPC compartments in Cbl−/− and DKO mice according to a previously described gating strategy [19]. In the BM, both long-term and short-term HSCs (LT-HSC: CD150+CD48−Flk2− LSK and ST-HSC: CD150−CD48−Flk2− LSK, respectively) were decreased in DKO mice compared to Cbl−/− mice (Fig. 3A, B), largely attributed to the disruption of normal hematopoiesis by leukemia cells. However, in the spleen, we observed a dramatic increase in the percentage and total numbers of LT-HSC (Fig. 3C), megakaryocyte-erythrocyte (MegE) biased multi-potent progenitor 2 (MPP2) as well as granulocyte–macrophage (GM) biased MPP3 (Fig. 3D), consistent with the expansion of myeloid cells in blood.

Fig. 3.

Cbl;Lnk DKO HSPCs show superior transplantability. A-B Frequency (A) and number (B) of HSPC compartments in the BM of Cbl−/− and DKO mice. C-D Frequency (C) and number (D) of HSPC compartments in the spleen of Cbl−/− and DKO mice. E Competitive transplantation and analysis strategy of Cbl−/− and DKO mice. F Donor-derived cell percentage in the PB of recipient mice at 4, 8, 12, 16 weeks post-transplantation. G Lineage cell percentage in donor-derived cells at 16 weeks post-transplantation. H Donor-derived LT-HSC cell number in the spleen of recipient mice after 16 weeks posttransplantation. Data from A-D were obtained from 5-month-old mice (n = 3 for each genotype). Data from F–H were obtained from PB of recipient mice (n = 6 for each group). Each symbol represents a mouse. Error bars represent SE. p values were calculated by unpaired student’s t-test. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns, not significant

Next, we investigated the transplantation and disease-initiating ability of HSPCs from Cbl;Lnk DKO mice. Competitive transplantation was performed by injecting 1 million total BM cells from Cbl−/− or Cbl;Lnk DKO mice (CD45.2+) together with an equal number of competitive BM cells (CD45.1+) into lethally irradiated recipient mice (CD45.1/2+). Every four weeks post-transplantation, we examined the percentage of donor-derived cells in blood (Fig. 3E). Our data showed that HSPCs from DKO mice exhibited superior transplantation ability compared to those from Cbl−/− mice (Fig. 3F). Additionally, these donor cells exhibited a more pronounced differentiation bias towards myeloid cells as analyzed by flow cytometry (Fig. 3G), indicating their intrinsic MPN-initiating potential. Moreover, we observed a higher number of donor-derived HSCs residing in the spleen of recipients transplanted with Cbl;Lnk DKO cells compared to Cbl−/− cells (Fig. 3H). Altogether, these data further confirm the critical role of LNK in restraining HSPC transplantation and MPN disease-initiating capacity in the context of Cbl deficiency.

LNK Deficiency Inhibits Proteasome Activity

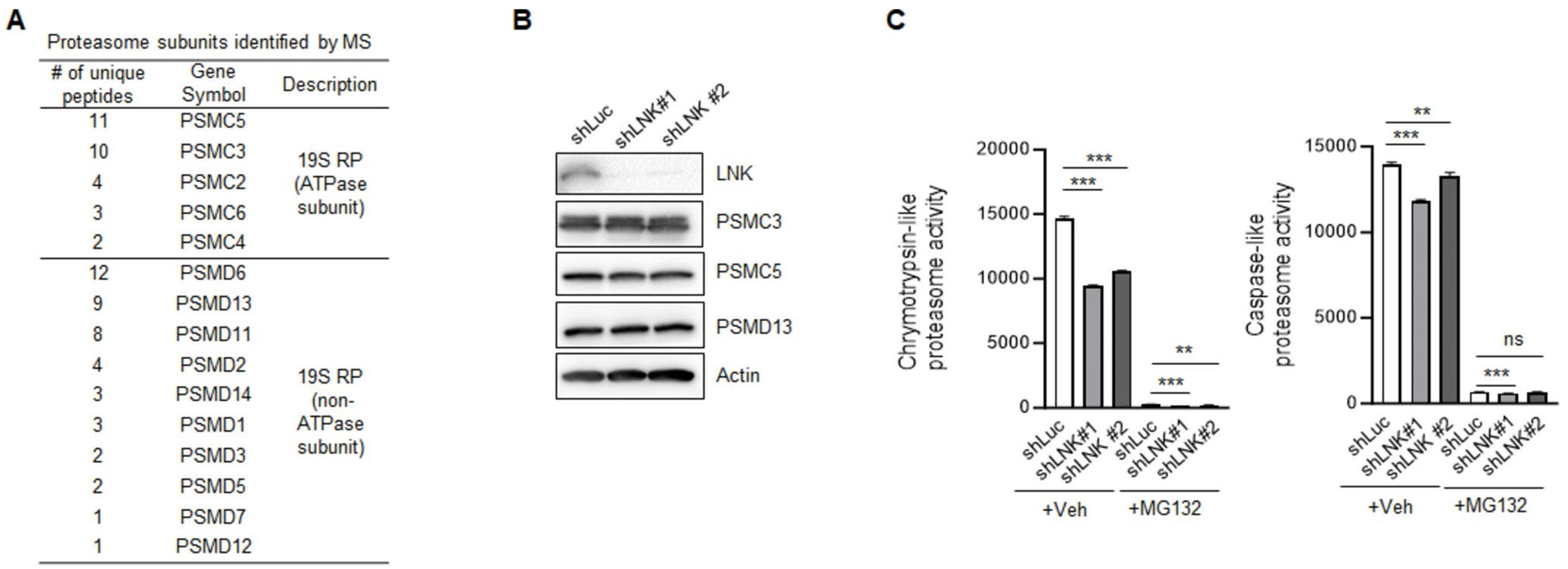

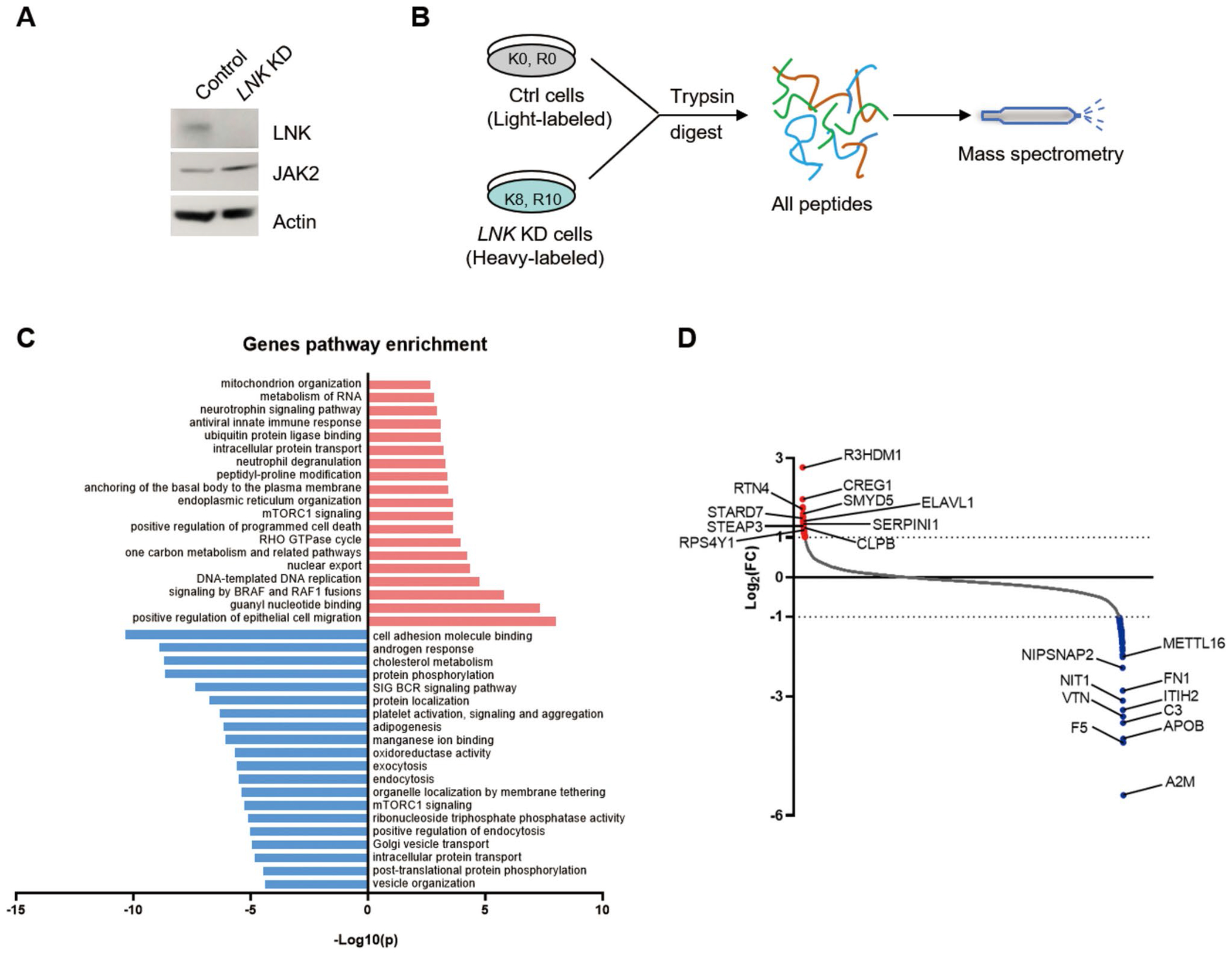

We previously demonstrated that Cbl family E3 ligases ubiquitinates and degrades JAK2 in HSPCs and myeloid leukemia cells through the adaptor protein Lnk [17]. Our new data indicate that Cbl;Lnk DKO mice exhibited a more severe MPN phenotype than their single knockout mice, and even develop leukemia transformation. This suggests that Lnk has additional roles beyond JAK/STAT signaling. To investigate these new mechanisms, we performed sequential immunoprecipitation (IP) by tagging Lnk with Flag/HA double tags, followed by mass spectrometry (MS) to identify potential interacting proteins (Supplementary Table 2). In our IP/MS data, we identified most of the previously reported Lnk-interactors, such as JAK2, CBL and 14–3-3 [4, 17, 22], suggesting the high reliability of the experiment. In addition, we found a number of proteins in the IP/MS that belong to the 19S regulatory particle (RP) of the proteasome, but not 20S catalytic particle (CP) (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

LNK positively regulates proteasome activity. A Proteasome subunits identified in LNK immunoprecipitation/mass spectrometry (IP/MS). B Immunoblot of PSMC3, PSMC5 and PSMD13 in shLuc control and two separate LNK-deficient TF-1 cell lines. C The chymotrypsin-like and caspase-like proteolytic activities of the proteasome from shLuc control and LNK-deficient TF-1 cell lines. Data from C were independently repeated three times. Error bars represent SE. p values were calculated by unpaired student’s t-test. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns, not significant

The 19S regulatory particle binds to and activates the 20S catalytic particle to degrade unwanted ubiquitin-tagged proteins in a cell. These facts prompted us to investigate the potential role of LNK in the level and activity of proteasomes. LNK-deficient TF-1 cells exhibited proteasome levels comparable to those of control cells, as evidenced by immunoblotting with PSMC3, PSMC5, and PSMD13, three subunits of the 19S regulatory particle identified in the IP/MS (Fig. 4B). Using luminescent peptide substrates, we found that silencing LNK with two independent shRNAs significantly reduced the chymotrypsin-like and caspase-like proteolytic activities of the proteasome, even in the presence of the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that LNK plays a previously unrecognized role in regulating proteasome activity.

The Altered Proteome in LNK-deficient Cells

Having established the positive role of Lnk in regulating proteasome activity, we investigated the changes of total proteomics induced by LNK loss. To this end, we utilized SILAC (Stable Isotope Labeling by Amino Acids in Cell Culture) technique combined with mass spectrometry to quantitatively compare the levels of total proteins in LNK KD and control cells (Fig. 5A, B). Protein levels in LNK KD cells with fold changes of 50% greater or less than those in control cells were classified as differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (Supplementary Table 3). Gene pathway enrichment analysis of these DEGs revealed that LNK loss resulted in significant alterations in various pathways, including cell migration, intracellular transportation, signal transduction and cell metabolism (Fig. 5C). We highlighted the proteins with the most pronounced changes in their levels (Fig. 5D). These proteins are involved in a wide range of physiological processes, suggesting that LNK plays an important role in multiple physiological functions.

Fig. 5.

LNK loss leads to an altered proteome. A Immunoblot of LNK in shLuc control and shLNK (KD) TF-1 cells. JAK2 is a positive control that is known to be upregulated in LNK KD cells. B Schematic representation of SILAC technique and mass spectrometry. to determine the proteomes of shLuc control and LNK KD cells. C Gene pathway enrichment of differentially expressed genes (DEG) identified by SILAC/MS in LNK KD cells compared with control cells. Proteins with fold changes larger or smaller than 50% were defined as DEG. Red and blue bars indicate up- and down-regulated pathways, respectively. D Proteins with most significantly up- (red dots) and down-regulated (blue dots) changes in LNK KD cells were indicated

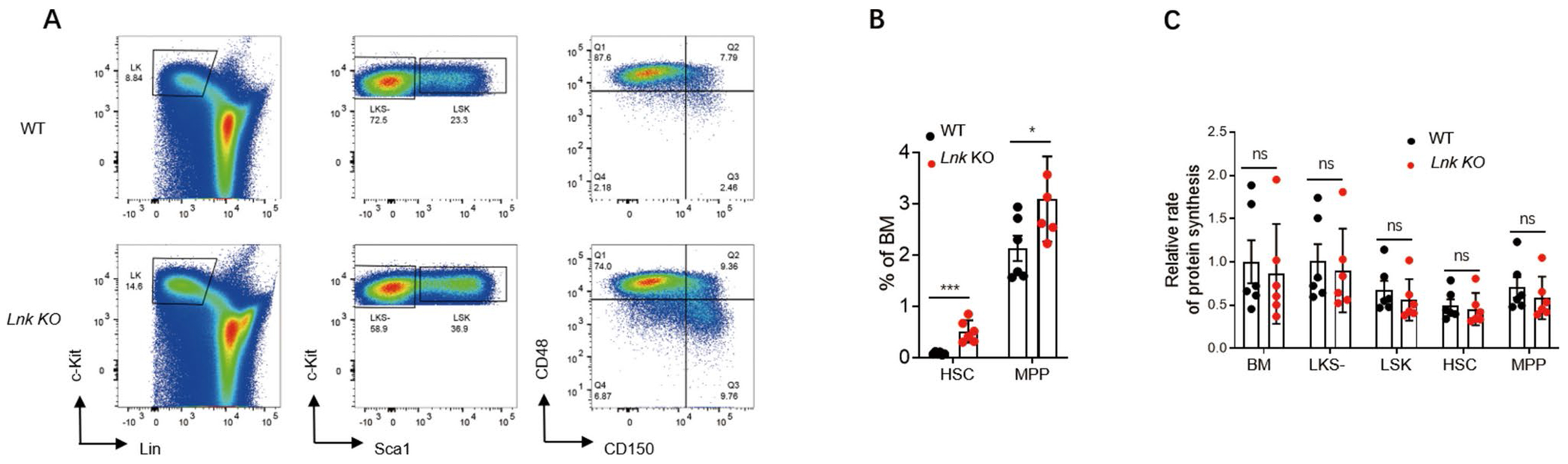

The rate and fidelity of protein synthesis are essential not only for maintaining proteostasis but also for the fitness and function of HSCs [18, 20]. Receptor-mediated signaling transduction is one factor that regulates protein translation. Given the critical role of LNK in regulating multiple signaling pathways [10], we therefore investigated the potential impact of LNK loss on the translation rate in HSPCs. To this end, we employed the in vivo O-Propargyl-Puromycin incorporation assay to quantify the translation rate. Consistent with a previous report [4], Lnk KO mice exhibited an expanded pool of HSCs (Fig. 6A, B). Importantly, Lnk-deficient HSCs and MPPs showed a comparable protein translation rate to that of WT mice (Fig. 6C). Together, these data reveal a novel role for LNK in controlling proteostasis by regulating proteasome activity rather than the protein translation rate.

Fig. 6.

LNK loss does not affect the protein synthesis rate of HSPCs. A Representative flow plots of HSPC subpopulations in bone marrows of WT and Lnk KO mice. B Percentages of HSCs and MPPs in bone marrows of WT (n = 6) and Lnk KO (n = 6) mice as shown in A. C Statistics of relative protein synthesis rates in the indicated populations of bone marrow cells from WT (n = 6) and Lnk KO (n = 6) mice. Each symbol in B and C represents a mouse. Error bars represent SE. p values were calculated by unpaired student’s t-test. *p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns, not significant

Discussion

CBL family of E3 ligases is involved in regulating various signal transduction pathways by modulating receptor and non-receptor tyrosine kinases [12]. Several CBL E3-dead mutations have been identified in both hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic malignancies [13, 23]. We previously demonstrated that CBL E3 ligases are responsible for the ubiquitination and degradation of JAK2 in proteasomes through the adaptor protein LNK. JAK2 inhibitor Ruxolitinib can effectively mitigate the MPN phenotype in a Cbl;Cbl-b dual knockout mouse model and primary acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patient samples [17]. Polymorphisms and mutations in LNK have been identified in a wide range of hematologic disorders, including excessive platelet production and lymphoid or myeloid leukemia [24–28], suggesting its role as a cancer predisposition factor. These observations prompt us to further investigate the pathologic significance of LNK inactivation in the context of CBL loss.

In this study, we generated a Cbl and Lnk dual knockout mouse model (DKO) to simultaneously inactivate their functions. Notably, young adult DKO mice (8 weeks old) exhibited a dramatic increase in circulating white blood cells (WBC) compared to Cbl or Lnk single knockout mice. The WBC count further increased with age (5 months old), accompanied by a decreased RBC count. Significantly, a proportion of Mac1+ cells became c-Kit+ in the peripheral blood of DKO mice, but not in Cbl−/− or Lnk−/− mice. Additionally, we observed a striking expansion of HSPCs in the spleen of DKO mice at 5 months of age. Collectively, these findings indicate that Cbl and Lnk dual depletion induces a severe MPN and leukemia transformation.

CBL and its family member CBL-b share structural similarity and exhibit functional redundancy in regulating signal transduction. As germline double knockout mice for Cbl and Cbl-b were embryonically lethal, we and others have previously utilized conditional Cbl and Cbl-b double knockout mouse models (Cblf/f;Cbl-bf/f;Vav-Cre or Cblf/f;Cbl-bf/f;CreERT2) mice to investigate their roles in HSC biology. Both models displayed myeloproliferative disorders associated with elevated and uncontrolled signal transduction pathways, albeit from different tyrosine kinases [17, 29]. However, co-mutations of Cbl and Cbl-b have not been reported in the same patient with hematologic malignancies. Consequently, these mouse models do not fully reflect the clinical outcomes of patients carrying CBL mutations. Our work examined the impact of dual inactivation of Cbl and Lnk on HSC fitness and disease development, based on the clinical co-existence of mutations in both genes, thereby providing important insights for the treatment of such patients.

As an adaptor protein preferentially expressed in hematopoietic cells, LNK has been extensively studied in the context of normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Although most studies have focused on its negative role in signal transduction, its functions in other cellular activities remain underexplored. In this study, we unveil a new role of LNK in regulating proteasome activity. While the levels of proteasomes remain unchanged in LNK-deficient cells, the proteasome activity is significantly reduced. We propose that LNK might facilitate the assembly or proper conformation of proteasomes, which could be disrupted in LNK-deficient cells. It is noteworthy that our IP/MS results identified several proteasome subunits as novel Lnk interactors in the hematopoietic TF-1 cell line with stable BCR-ABL expression. However, this was not reproduced in 293 T cells. One possible explanation for this discrepancy is the differing cellular components present in the two cell lines. Additionally, the interaction between Lnk and the proteasome may be dependent on post-translational modifications, particularly BCR-ABL-induced phosphorylation of Lnk or other cellular mediators. We compared the total proteome changes between control and Lnk-deficient cells by SILAC/mass spectrometry. However, due to the negative role of Lnk in regulating cytokine/receptor/JAK2 signaling and potentially other unknown functions, we cannot exclude the contribution of transcriptional changes to the altered proteome.

We previously showed that Lnk deficiency alone leads to a dramatic increase in HSC number and superior transplantability [4]. Although both Lnk−/− and Cbl−/− mice exhibited only mild MPN at advanced age [9, 21], our study revealed that Cbl;Lnk DKO mice succumb to severe MPN between 5 and 9 months of age and show mild signs of malignant transformation, demonstrating their combinatorial roles in MPN development. However, since we did not directly compare the engraftment of bone marrow cells from Cbl;Lnk DKO mice with those from Lnk−/− mice in this study, we approach our conclusions about the combinatorial contributions to transplantability and MPN-initiating capacity with caution.

Taken together, our study demonstrates the combined effect of dual loss-of-function of Cbl and Lnk in exacerbating MPN progression in a mouse model. Notably, we uncover a new role of LNK in modulating proteasome activity, advancing our understanding of myeloproliferative diseases linked to genetic alterations in LNK.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Wallace Y. Langdon for kindly providing us Cbl−/− mice.

Funding

KL is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China grant 82370110 and Shenzhen Medical Academy of Research and Translation grant B2302017. HH is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China grant 82173131.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s12015-024-10825-0.

Code Availability Not applicable.

Ethical Approval All the animal studies were performed under an approved protocol by the Institutional Animal Care and Use committee of Hunan University.

Consent to Participate Not applicable.

Consent for Publication Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Watowich SS, et al. (1996). Cytokine receptor signal transduction and the control of hematopoietic cell development. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology, 12, 91–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tong W, & Lodish HF (2004). Lnk inhibits Tpo-mpl signaling and Tpo-mediated megakaryocytopoiesis. Journal of Experimental Medicine, 200(5), 569–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tong W, Zhang J, & Lodish HF (2005). Lnk inhibits erythropoiesis and Epo-dependent JAK2 activation and downstream signaling pathways. Blood, 105(12), 4604–4612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bersenev A, et al. (2008). Lnk controls mouse hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and quiescence through direct interactions with JAK2. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 118(8), 2832–2844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Velazquez L, et al. (2002). Cytokine signaling and hematopoietic homeostasis are disrupted in-deficient mice. Journal of Experimental Medicine, 195(12), 1599–1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takaki S, et al. (2000). Control of B cell production by the adaptor protein Lnk: Definition of a conserved family of signal-modulating proteins. Immunity, 13(5), 599–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng Y, et al. (2016). LNK/SH2B3 regulates IL-7 receptor signaling in normal and malignant B-progenitors. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 126(4), 1267–1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seita J, et al. (2007). Lnk negatively regulates self-renewal of hematopoietic stem cells by modifying thrombopoietin-mediated signal transduction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104(7), 2349–2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bersenev A, et al. (2010). Lnk constrains myeloproliferative diseases in mice. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 120(6), 2058–2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maslah N, et al. (2017). The role of LNK/SH2B3 genetic alterations in myeloproliferative neoplasms and other hematological disorders. Leukemia, 31(8), 1661–1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ha JS, & Jeon DS (2011). Possible new mutations in myeloproliferative neoplasms. American Journal of Hematology, 86(10), 866–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang R, Langdon WY & Zhang J (2022). Negative regulation of receptor tyrosine kinases by ubiquitination: Key roles of the Cbl family of E3 ubiquitin ligases. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 13. 10.3389/fendo.2022.971162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leardini D, et al. (2022). Role of CBL mutations in cancer and non-malignant phenotype. Cancers, 14(3), 839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baccelli F, et al. (2022). Immune dysregulation associated with co-occurring germline e CBL and SH2B3 variants. Human Genomics, 16(1). 10.1186/s40246-022-00414-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oh ST, et al. (2010). Identification of novel mutations in patients with chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms and related disorders. Blood, 116(21), 143–144. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balcerek J, et al. (2018). Lnk/Sh2b3 deficiency restores hematopoietic stem cell function and genome integrity in Fancd2 deficient Fanconi anemia. Nature Communications, 9(1), 3915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lv K, et al. (2017). CBL family E3 ubiquitin ligases control JAK2 ubiquitination and stability in hematopoietic stem cells and myeloid malignancies. Genes & Development, 31(10), 1007–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lv K, et al. (2021). HectD1 controls hematopoietic stem cell regeneration by coordinating ribosome assembly and protein synthesis. Cell Stem Cell, 28(7), 1275–1290 e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pietras EM, et al. (2015). Functionally distinct subsets of lineage-biased multipotent progenitors control blood production in normal and regenerative conditions. Cell Stem Cell, 17(1), 35–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Signer RA, et al. (2014). Haematopoietic stem cells require a highly regulated protein synthesis rate. Nature, 509(7498), 49–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rathinam C, et al. (2010). Myeloid leukemia development in c-Cbl RING finger mutant mice is dependent on FLT3 signaling. Cancer Cell, 18(4), 341–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang J, et al. (2012). 14-3-3 regulates the LNK/JAK2 pathway in mouse hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 122(6), 2079–2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kales SC, et al. (2010). Cbl and human myeloid neoplasms: The Cbl oncogene comes of age. Cancer Research, 70(12), 4789–4794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perez-Garcia A, et al. (2013). Genetic loss of SH2B3 in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood, 122(14), 2425–2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trifa AP, et al. (2020). SH2B3 (LNK) rs3184504 polymorphism is correlated with V617F-positive myeloproliferative neoplasms. Revista Romana De Medicina De Laborator, 28(3), 267–277. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sinclair PB, et al. (2019). SH2B3 inactivation through CN-LOH 12q is uniquely associated with B-cell precursor ALL with iAMP21 or other chromosome 21 gain. Leukemia, 33(8), 1881–1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soranzo N, et al. (2009). A genome-wide meta-analysis identifies 22 loci associated with eight hematological parameters in the HaemGen consortium. Nature Genetics, 41(11), 1182–U38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gieger C, et al. (2011). New gene functions in megakaryopoiesis and platelet formation. Nature, 480(7376), 201–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.An W, et al. (2016). VAV1-Cre mediated hematopoietic deletion of CBL and CBL-B leads to JMML-like aggressive early-neonatal myeloproliferative disease. Oncotarget, 7(37), 59006–59016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.