Abstract

Background

While observational studies have demonstrated a potential link between inflammatory cytokines and oral diseases, the question of causality is warranting further investigation. This study aimed to comprehensively assess the potential causal role of 41 inflammatory cytokines in common oral diseases.

Methods

A two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR) study was conducted using the summary statistics from the largest publicly available genome-wide association study (GWAS) for 41 inflammatory cytokines and common oral diseases (indicated by the index of decayed and filled tooth surfaces divided by number of tooth surfaces (DFSS), index of decayed, missing and filled tooth surfaces (DMFS), number of natural teeth, and periodontitis). Inverse variance weighted regression (IVW) was used as the primary method to estimate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for assessing the causal effect. Sensitivity analyses with other four analytical approaches were performed to test the validity of our findings.

Results

Increased levels of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and stem cell growth factor beta (SCGF-β) were significantly associated with the risk of DFSS, with the ORs of 1.058 (95% CI: 1.004-1.115, P = .033) and 1.035 (95% CI:1.002-1.069, P = .038), respectively. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA) exhibited a negative association with DMFS (OR = 0.934, 95% CI: 0.886-0.985, P = .012). Furthermore, interleukin-9 (IL-9) was associated with in increased risk of periodontitis (OR = 1.148, 95% CI:1.031-1.277, P = .011). Additionally, no significant association was found between inflammatory cytokines and the number of natural teeth. Sensitivity analyses yielded generally consistent results.

Conclusions

This MR study provides evidence supporting potential causal associations of four inflammatory cytokines (HGF, SCGF-β, IL-1RA, IL-9) with the risk of common oral diseases, which may contribute to the development of more targeted prevention strategies for these diseases.

Key words: Inflammatory cytokines, Mendelian randomization, Oral diseases, Dental caries, Periodontitis

Introduction

Oral disorders, encompassing a range of conditions from dental caries to periodontitis, are among the most prevalent health issues globally. Dental caries, is a disease of dental hard tissues and has been related to multi-factorial etiology.1 It is a leading cause of tooth loss and affects individuals across all age groups, characterized by the demineralization of tooth enamel. Periodontitis, an inflammatory disease affecting the tissues supporting the teeth, can lead to tooth loss and has been linked to systemic health complications. The burden of these oral diseases extends beyond pain and dysfunction, contributing significantly to healthcare costs and impacting quality of life.2,3 Despite advancements in preventive measures and treatment strategies, the prevalence of these disorders remains high, highlighting the need for a deeper understanding of their underlying mechanisms.

Previous studies have explored the association between inflammation and oral disorders, identifying various cytokines implicated in the pathogenesis of dental caries 4,5 and periodontitis.6, 7, 8 However, many of these investigations have been observational in nature, making it challenging to discern causality from correlation. Additionally, the focus has often been limited to a select few cytokines, neglecting the complex interplay within the broader cytokine network that likely influences oral health, which may obscure potential targets for prevention or treatment interventions.

Mendelian randomization (MR) is an epidemiological method that uses genetic variants as instrumental variables (IV) to assess the causal relationship between an exposure and an outcome. The underlying principle of MR is that genetic variants are randomly assigned at conception, thereby minimizing the confounding factors and reverse causation typically found in observational studies. Specifically, MR assumes that the association between a genetic variant and the outcome is mediated solely through the exposure, providing an estimate of the causal effect of the exposure on the outcome that is free from many of the biases that can affect traditional observational studies.9 MR study has been used to investigate the association between various factors and periodontitis, such as Crohn's disease,10 hypertension,11 nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.12 However, to date, fewer studies have comprehensively explored the roles of inflammatory cytokines in oral disorders based on MR methods. To address these gaps, we conducted a two-sample MR study, examining the association between 41 inflammatory cytokines and four common oral diseases (indicated by the index of decayed, missing and filled tooth surfaces (DMFS), index of decayed and filled tooth surfaces divided by number of tooth surfaces (DFSS), number of natural teeth, and periodontitis). By utilizing genetic variants associated with the levels of 41 inflammatory cytokines as IVs, this study design allows for stronger causal inferences compared to traditional observational studies, and may provide insights into the complex etiology of oral diseases and offer a foundation for the development of targeted preventive strategies and therapeutic interventions.

Methods

Study design

This study employed a MR design, utilizing genetic variants as IVs to explore the causal associations between inflammatory cytokines and common oral diseases. The fundamental tenets of MR analysis encompass the following key assumptions: (1) a robust correlation exists between the instrumental variable and the exposure factor (association assumption), (2) the instrumental variable remains independent of the confounding variables (independence assumption), and (3) the instrumental variable exerts its impact on the outcome solely through the exposure factor, precluding any alternative pathways to influence the outcome.13

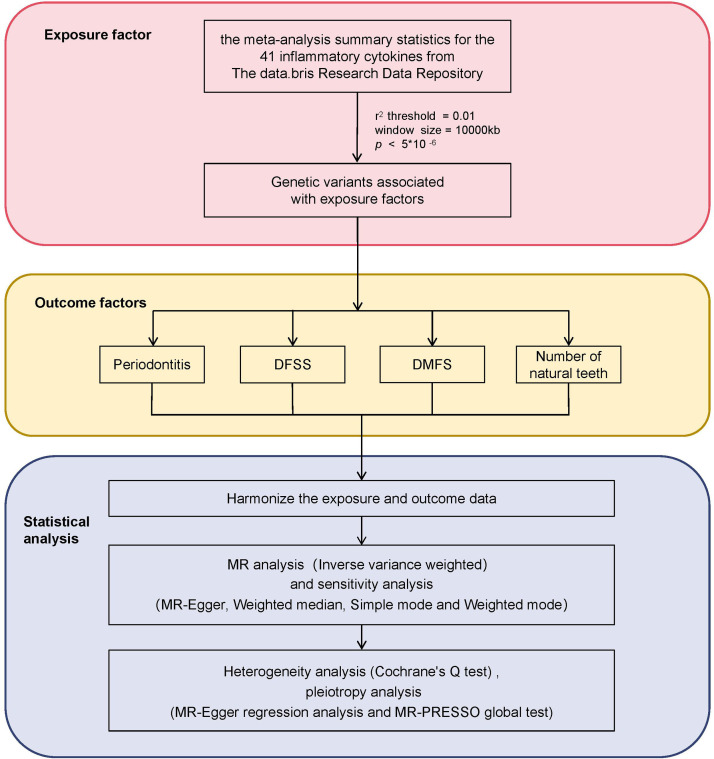

This study was conducted using publicly available data with appropriate ethical approval for the original data collection. All data used in this analysis were anonymized or de-identified, and no identifiable information was accessed or used. Therefore, no additional ethical approval was required for this secondary analysis of de-identified data. The study adheres to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human subjects. Additionally, this study followed the STROBE reporting guideline for MR studies.14 The flow of this study can be seen in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the methodology in this study, including the selection of inflammatory cytokines, common oral diseases, and statistical techniques applied for Mendelian randomization analysis. The common oral diseases were indicated by the index of decayed and filled tooth surfaces divided by number of tooth surfaces (DFSS), index of decayed, missing and filled tooth surfaces (DMFS), number of natural teeth, and periodontitis).

Genetic instruments for inflammatory cytokines

The inflammatory cytokine dataset was obtained from the following website: https://data.bris.ac.uk/data/dataset/3g3i5smgghp0s2uvm1doflkx9x#, which a comprehensive study elucidating genome variant linkages with 41 cytokines and growth factors among a cohort comprising 8,293 Finnish individuals (Supplemental Table 1). This dataset encompasses the summary statistics of a GWAS concerning inflammatory cytokines, meticulously conducted across three Finnish cohorts (YFS, FINRISK 1997, and FINRISK 2002). The mean participant ages stand at 37 years for the YFS study and 60 years for the FINRISK survey.

In detail, the processing of the cytokine dataset involved the following steps: First, the selection of SNPs strongly associated with inflammatory factors was based on a genome-wide significant threshold of P < 5 × 10−8. However, recognizing the limited number of SNPs identified for certain cytokines under this stringent criterion, a less restrictive threshold of P < 5 × 10−6 was adopted for those cytokines. This adjustment allowed for a more comprehensive analysis without sacrificing the integrity of the dataset. Second, to mitigate potential biases stemming from linkage disequilibrium (LD), SNPs in high LD were excluded through a clustering approach. The LD threshold for clustering was set at r²<0.01, with a clustering window size of 10,000 kilobases (kb). Alignment verification between exposures and outcomes was conducted to ensure consistency and accuracy across the dataset. Additionally, SNP loci lacking allele information, exhibiting incompatible alleles, or featuring palindromic or reverse repetitive sequences were systematically removed to maintain the quality and integrity of the dataset. Outliers in IVs were addressed using the MR multivariate residual method. The strength of each selected instrument was assessed using the F-statistic, calculated as F = R² × (N−2)/(1−R²), where R² represents the phenotypic variance explained by each genetic variant in relation to the cytokine exposure and N is the sample size.

Data sources for outcomes

In this study, the GWAS data for four common oral disorders (indicated by the index of decayed, missing and filled tooth surfaces (DMFS), index of decayed and filled tooth surfaces divided by number of tooth surfaces (DFSS), number of natural teeth, and periodontitis) were derived from the Gene-Lifestyle Interactions in Dental Endpoints (GLIDE) consortium in conjunction with the UK Biobank,15 is publicly accessible at the following link: https://doi.org/10.5523/bris.2j2rqgzedxlq02oqbb4vmycnc2. All participants were of European ancestry. The sample size was 26792 for DMFS, 26533 for DFSS and 27949 for number of natural teeth. while periodontitis contained 17353 cases and 28210 controls. Data for the DMFS and DFSS were obtained from clinical dental records. In addition to self-reported studies, data for number of natural teeth were obtained from clinical dental records. Periodontitis was diagnosed using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/American Academy of Periodontology definition or similar criteria.16 Detailed information on the outcomes can be found in Supplemental Table 2.

Statistical analyses

To harmonize the exposure and outcome datasets for this MR study, we mapped the SNPs from the exposure (inflammatory cytokines) and outcome (DMFS, DFSS, number of natural teeth, and periodontitis) datasets to ensure that the effect sizes corresponded correctly. This included checking for allele orientation and harmonizing effect alleles across datasets to mitigate any potential biases in causal inference. When harmonizing exposure and outcome datasets, β-nerve growth factor (β-NGF) was deleted for incompatible alleles of the following SNPs: rs71641308, rs7970581, rs73472576, and rs28637706, and thus there were no suitable SNPs to use in the MR analysis. Consequently, only 40 inflammatory cytokines were included in the subsequent MR analysis. The primary MR analysis employed the inverse variance weighted (IVW) method to evaluate the association between inflammatory cytokines and periodontitis. The IVW method is a widely used statistical technique in MR studies that combines estimates from multiple SNPs to provide a robust estimate of the causal effect of an exposure on an outcome. This method is particularly useful when there are multiple genetic instruments available for the exposure of interest. The formula used in the IVW method can be expressed mathematically as: , where is the overall causal effect estimate, are the individual SNP estimates, and are the weights assigned to those estimates (typically the inverse of the variance).17

Four analytical approaches, including MR Egger regression (MR-Egger), Weighted-median, Simple mode, and Weighted mode, were employed to conduct a sensitivity analysis. These methods quantified the causal effects in terms of odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Scatter plots were utilized to delineate the association between SNP impact on exposure and SNP impact on outcome. Heterogeneity among SNPs was evaluated using Cochran's Q test. Assessment of horizontal pleiotropy was carried out through the MR-PRESSO global test and MR-Egger intercept, with a P value exceeding 0.05 indicating the absence of horizontal pleiotropy. To address pleiotropy, the relationship between inflammatory cytokines and oral disorders was investigated using MR-PRESSO to identify and exclude outliers. Furthermore, a leave-one-out analysis was conducted to evaluate the impact of individual SNPs on the MR estimates by systematically removing each SNP and examining resultant changes, thereby elucidating the influence of specific SNPs on the outcomes.

Statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.3.1), and the packages used in the analysis process were ‘TwoSample’ (version 0.5.7) and ‘MR-PRESSO’ (version 1.0). All statistical tests were two-sided, with a significance level of 0.05 utilized to establish statistical significance.

Results

Association of inflammatory cytokines with dental caries

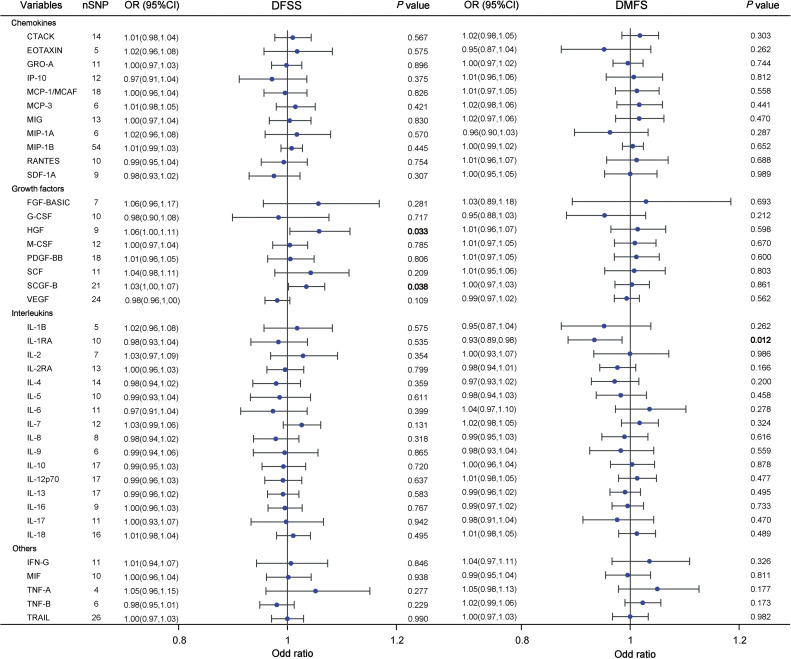

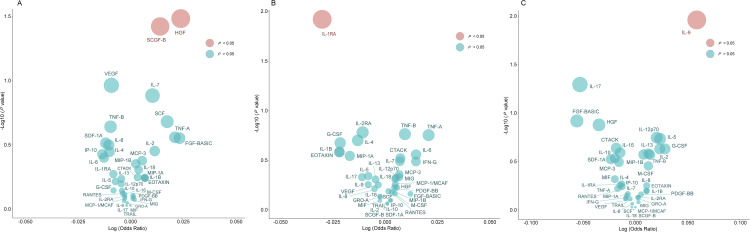

In our MR study, we found some potential causal associations between inflammatory cytokines and dental caries using DFSS and DMFS metrics, the results are presented in Figure 2. Our primary analysis, utilizing the IVW method, found significant evidence for an association between hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and DFSS (OR = 1.058, 95% CI=1.004-1.115, P = .033). Similarly, stem cell growth factor beta (SCGF-β) exhibited an inverse relationship with the risk of DFSS (OR = 1.035, 95% CI=1.002-1.069, P = .038, Figure 3A). Conversely, interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA) was negatively associated with the risk of DMFS (OR = 0.934, 95% CI=0.886-0.985, P = .012, Figure 3B).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot results for analyzing potential causal relationships between inflammatory cytokines and dental caries using DFSS and DMFS indicators. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using the inverse variance weighted method. Each point represents an estimate of the effect size, with horizontal lines indicating 95% CI. Significant P values (P < .05) are bolded. Abbreviations: SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; DFSS, decayed and filled tooth surfaces divided by number of tooth surfaces; DMFS, decayed, missing and filled tooth surfaces.

Fig. 3.

Bubble plots of potential associations of inflammatory cytokines with three outcomes using the IVW method. A, For DFSS (index of decayed and filled tooth surfaces divided by number of tooth surfaces); B, For DMFS (index of decayed, missing and filled tooth surfaces); C, For periodontitis. The y-axis represents the −log10 (P value) effect for the association, while the x-axis illustrates the corresponds log (odds ratio) effect for each cytokine on three distinct outcomes. A red bubble signifies a P value of less than .05, whereas a blue bubble denotes a P value greater than or equal to .05.

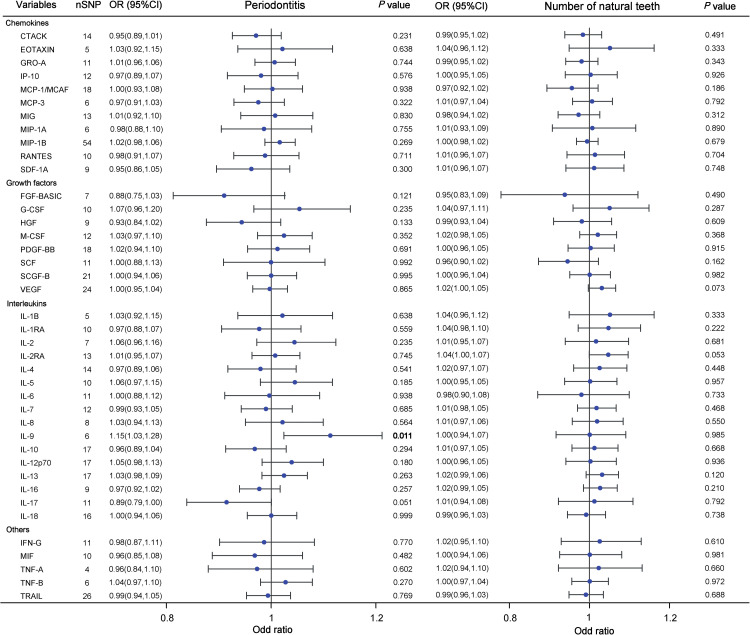

Association of inflammatory cytokines with periodontitis and the number of natural teeth

As shown in Figure 4, the IVW analyses indicated that genetically predicted interleukin-9 (IL-9) was significantly associated with the increased risk of periodontitis (OR = 1.148, 95% CI=1.031-1.277, P = .011, Figure 3C). However, we did not observe any significant association between other 39 inflammatory cytokines and the risk of periodontitis (all P > .05). Additionally, the IVW models also showed that genetic predisposition of inflammatory cytokines concentration was not significantly associated with the number of natural teeth (Figure 4).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot results for analyzing potential causal relationships between inflammatory cytokines and dental caries using periodontitis and the number of natural teeth indicators. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using the inverse variance weighted method. Each point represents an estimate of the effect size, with horizontal lines indicating 95% CI. Significant P values (P < .05) are bolded. Abbreviations: SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Heterogeneity and pleiotropy analysis

In the analysis of heterogeneity using Cochrane's Q test, there was no significant evidence of heterogeneity was observed in the impact of IL-9, HGF, SCGF-β, or IL-1RA on the susceptibility to periodontitis (all P > .05, Supplemental Table 3). The presence of directional pleiotropy in SNPs was examined by assessing their intercept terms and conducting MR-Egger regression analysis. As illustrated in Supplemental Table 3, the intercept terms did not deviate significantly from zero, indicating the absence of directional pleiotropy for the four inflammatory cytokines (all intercept terms, P > .05). Furthermore, the MR-PRESSO global test did not detect any substantial horizontal pleiotropy for four cytokines (all P > .05).

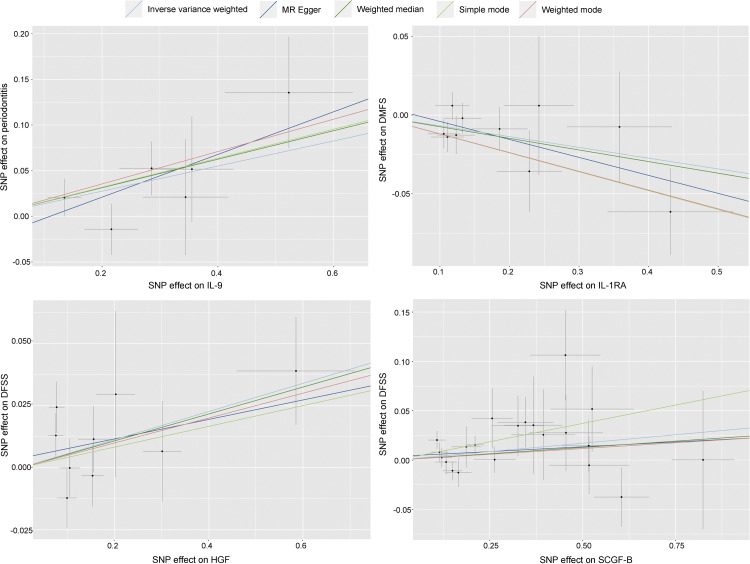

Sensitivity analyses

Four analysis methods were used, including MR Egger regression (MR-Egger), Weighted-median, Simple mode, and Weighted mode, and the statistical results obtained were generally consistent with the IVW analyses (Supplemental Table 4-7). Scatter plots (Figure 5) were used to demonstrate IL-9, HGF, SCGF-β, and IL-1RA causality estimates. Each point in the scatter plot represents an SNP. The effect of one SNP on inflammatory cytokines is showed on the horizontal axis, and the effect of the same SNP on periodontitis is on the vertical axis. The vertical and horizontal lines around each point show the 95% confidence interval (CI) for each SNP. The trend directions of the scatter plots reinforce the reliability of the above results. The funnel plot reinforces the results of the MR-Egger intercept test, and Supplemental Figure 1 illustrates that genetic pleiotropy did not lead to biased causal effect estimates. In Supplemental Figure 1, Panel A illustrates the relationship between HGF and DFSS, Panel B depicts the association between SCGF-β and DFSS, Panel C represents the correlation between IIL-1RA and DMFS, and Panel D shows the link between IL-9 and periodontitis. The leave-one-out method was used to determine the impact of each SNP on the results of the analysis (Supplemental Figure 2). The overall error lines for IL-9, HGF, SCGF-β, and IL-1RA did not change much, and the removal of a SNP did not result in a causal effect that caused the remaining SNPs to cross the confidence interval to the opposite side, indicating that no individual SNPs had an effect on the overall results.

Fig. 5.

Scatter plots showing causality estimates for IL-9, HGF, SCGF-β and IL-1RA using five methods (IVW, MR-Egger, Weighted-median, Simple mode, and Weighted mode). Scatter diagrams illustrate the per-allele correlation with the risk of outcome (y-axis) versus the per-allele correlation with one standard deviation of exposure (x-axis), with grey vertical and horizontal lines indicating the 95% confidence intervals for each SNP. Each dot represents one of the SNPs used in the genetic instrument variables. The slope of each line corresponds to the estimated MR effect of each method. Abbreviations: SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; DFSS, decayed and filled tooth surfaces divided by number of tooth surfaces; DMFS, decayed, missing and filled tooth surfaces.

Discussion

In this two-sample Mendelian randomization study, HGF and SCGF-β were found to be potentially associated with the risk of DMFS, while IL-1RA exhibited a negative association with the risk of DFSS. Additionally, a significant association was also observed between genetically predicted IL-9 levels and the susceptibility to periodontitis. Notably, these results were generally consistent by various sensitivity analyses, emphasizing the robustness of our findings. Our study provides insight into the causal relationship between several inflammatory cytokines and oral disorders.

HGF, a polypeptide growth factor categorized within the plasminogen family,18 has been shown to have a protective effect in the early stages of periodontitis, but becomes pathogenic and bone destructive in later stages.19 It has been shown that periodontitis increases the expression of HGF in periodontal tissues, and that in the early stages HGF attenuates early bone damage and reduces serum bone resorption markers. Nonetheless, persistent overexpression of HGF may contribute to the alveolar bone destruction in periodontitis by regulating IL-17, ultimately precipitating irreversible and chronic alveolar bone loss.20 Its impact on matrix remodeling by stimulating matrix metalloproteinases production during tissue healing 21 has led to suggestions of their potential use as markers for periodontitis. Additionally, the association of periodontitis with the presence and number of treated/untreated root carious lesions has been observed,22 with caries also being positively linked to the risk of periodontitis.23 Our findings are consistent with previous studies that have demonstrated a causal association between HGF and DFSS. Given HGF's involvement in various wound healing processes, disruptions in HGF signaling may contribute to defects in multiple regenerative mechanisms,24 potentially impacting the progression of tooth damage and loss of surfaces.

Derived from synthetic blood progenitor cells, the stem cell growth factor (SCGF) stands out as a potent factor triggering cellular activation and orchestrating the stimulation of human stem cells and immune cells in vivo. With its alpha and beta subtypes,25 SCGF-β has recently come into focus for its involvement in the inflammatory cascades underpinning metabolic disorders associated with systemic sclerosis,26 preeclampsia,27 cardiovascular conditions,28,29 and beyond. Despite its burgeoning relevance, investigations into the interplay between SCGF-β and caries status, particularly DMFS, remain limited. Several studies have demonstrated that SCGF-β can promote the migration and infiltration of neutrophils and monocytes into inflamed tissues.30 These immune cells release various enzymes and pro-inflammatory mediators that contribute to the demineralization of enamel and dentin. Additionally, SCGF-β has been shown to upregulate matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs),31 which are key players in the degradation of extracellular matrix components during caries progression. Moreover, SCGF-β interacts with its cognate receptor, CXCR4, expressed on various immune cell types.32 This interaction activates downstream signaling pathways that enhance cellular survival, proliferation, and chemotaxis. Such effects could potentially exacerbate the inflammatory response associated with dental caries. To our knowledge, this is the first MR study on the causal relationship between circulating levels of cytokines and DMFS. Further in-depth studies, especially those delving into mechanistic aspects, are warranted to delineate the precise impact of circulating SCGF-β levels on DMFS.

Our study revealed a significant negative correlation between Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA) levels and the risk of DFSS. IL-1RA, known for its anti-inflammatory properties as a natural antagonist of the IL-1 receptor, plays a crucial role in regulating the IL-1α/β-mediated signaling pathway. Previous research has consistently linked IL-1RA levels to the severity of periodontal disease, demonstrating a progressive reduction in IL-1RA levels in gingival tissue with the advancement of periodontitis.33Our findings align with existing evidence and support the notion that IL-1RA may have a protective effect against dental caries, underscoring the potential therapeutic implications of targeting IL-1RA in the prevention and management of dental caries.

The elevated levels of IL-9 observed in patients with gingivitis compared to those with healthy individuals align with our finding of a positive association between IL-9 and the risk of periodontitis. IL-9, as a pro-inflammatory cytokine derived from T-cells, plays a role in regulating both innate and adaptive immunity.34 Our study highlights a potential link between IL-9 and periodontal health, suggesting that IL-9 may contribute to the pathogenesis of periodontitis through mechanisms involving type 2 innate lymphocytes (ILC2s), regulatory T (Treg) cells,35 and genes associated with metabolic pathways. Moreover, the ability of IL-9 to promote osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption underscores its potential impact on structural damage in inflammatory bone diseases like periodontitis.36 Further research into the specific molecular pathways through which IL-9 influences periodontal health could provide valuable insights for targeted therapeutic interventions aimed at mitigating the progression of periodontal diseases.

Our MR study was the first study to comprehensively inflammatory factors and common oral disorders using a large GWAS data. However, some limitations should also be considered. First, the selection of genetic instruments for inflammatory cytokines was based on a P value threshold setting of 5 × 106. While this threshold was also commonly used in GWAS and allowed us to include a broader range of genetic variants, it also raises concerns about the potentially introducing weak instrument bias. Therefore, more genetic variants that are more strongly associated with the inflammatory cytokines needed to be identified in the future to confirm the causal relationship observed in our study. Second, considering that the purpose of this study was to preliminarily explore inflammatory factors related to oral disorders, our analyses did not perform FDR correction on the P value, which raises concerns regarding the potential for type I errors. Given the exploratory nature of our study, the use of a more stringent statistical control with a larger sample size in future research is essential to enhance the reliability of the findings. Third, our analyses were limited to data from European populations, which may restrict the generalizability of our findings to other ethnic groups. Given the known variations in genetic backgrounds and environmental exposures across different ethnicities, it is plausible that the associations between inflammatory cytokines and oral diseases may exhibit ethnic-specific patterns. Therefore, future studies in more diverse populations are warranted to validate and extend our findings, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the complex interplay between inflammatory cytokines and oral diseases across different ethnicities. Additionally, while our study provides significant insights into the association of inflammatory cytokines with common oral diseases, it is important to note that other oral diseases were not included in this analysis. Future studies should aim to explore a broader spectrum of oral health conditions to enhance our understanding of the role of inflammatory cytokines in oral disease pathogenesis.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this two-sample MR study provides evidence supporting certain inflammatory cytokines (such as HGF, SCGF-β, IL-1RA, IL-9) were associated with the risk of common oral disorders. Our findings may provide a basis for revealing the potential role of inflammation in common oral disorders and the prevention of these diseases.

Author contributions

FC and HL conceived the study and provided overall guidance. FC, ZL, and XH prepared the first draft and finalized the manuscript based on comments from all other authors. BX and YH were mainly responsible for data collection and statistical analyses. BH and LL calibrated the data and completed the visualization. All authors gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Z.-L. Liu and X.-Y. Huang contributed equally.

Conflict of interest

None disclosed.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by Fujian Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (2021J01794).

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.identj.2024.10.025.

Contributor Information

Huanhuan Liu, Email: mxd0917@163.com.

Fa Chen, Email: chenfa@fjmu.edu.cn.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Mathur VP, Dhillon JK. Dental Caries: A Disease Which Needs Attention. Indian J Pediatr. 2018;85:202–206. doi: 10.1007/s12098-017-2381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loesche W. Dental caries and periodontitis: contrasting two infections that have medical implications. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2007;21:471–502. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2007.03.006. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herrera D, Retamal-Valdes B, Alonso B, Feres M. Acute periodontal lesions (periodontal abscesses and necrotizing periodontal diseases) and endo-periodontal lesions. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S85–s102. doi: 10.1002/JPER.16-0642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slots J. Periodontitis: facts, fallacies and the future. Periodontology 2000. 2017;75:7–23. doi: 10.1111/prd.12221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hajishengallis G, Lamont RJ, Koo H. Oral polymicrobial communities: assembly, function, and impact on diseases. Cell Host Microbe. 2023;31:528–538. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2023.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou L, Zhang Y-F, Yang F-H, Mao H-Q, Chen Z, Zhang L. Mitochondrial DNA leakage induces odontoblast inflammation via the cGAS-STING pathway. Cell Communication and Signaling. 2021;19:58. doi: 10.1186/s12964-021-00738-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li X, Kiprowska M, Kansara T, Kansara P, Li P. Neuroinflammation: a distal consequence of periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2022;101:1441–1449. doi: 10.1177/00220345221102084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hajishengallis G. Immunomicrobial pathogenesis of periodontitis: keystones, pathobionts, and host response. Trends Immunol. 2014;35:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sekula P, Del Greco MF, Pattaro C, Köttgen A. Mendelian randomization as an approach to assess causality using observational data. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:3253–3265. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016010098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vinţeler N, Feurdean CN, Petkes R, et al. Biomaterials functionalized with inflammasome inhibitors—premises and perspectives. Journal of Functional Biomaterials. 2024;15:32. doi: 10.3390/jfb15020032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qing X, Zhang C, Zhong Z, et al. Causal association analysis of periodontitis and inflammatory bowel disease: a bidirectional mendelian randomization study. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2024;30:1251–1257. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izad188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Czesnikiewicz-Guzik M, Osmenda G, Siedlinski M, et al. Causal association between periodontitis and hypertension: evidence from Mendelian randomization and a randomized controlled trial of non-surgical periodontal therapy. European Heart Journal. 2019;40:3459–3470. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qiao F, Li X, Liu Y, Zhang S, Liu D, Li C. Periodontitis and NAFLD-related diseases: a bidirectional two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Oral Diseases. 2024;30:3452–3461. doi: 10.1111/odi.14785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenland S. An introduction to instrumental variables for epidemiologists. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47:358. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyx275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skrivankova VW, Richmond RC, Woolf BAR, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology using mendelian randomization: the STROBE-MR statement. Jama. 2021;326:1614–1621. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.18236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haworth S, Kho PF, Holgerson PL, et al. Assessment and visualization of phenome-wide causal relationships using genetic data: an application to dental caries and periodontitis. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2020;29:300–308. doi: 10.1038/s41431-020-00734-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burgess S, Butterworth A, Thompson SG. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data. Genet Epidemiol. 2013;37:658–665. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Q, Sun Y, Zhou T, Jiang C, A L, Xu W. Gut microbiota-dependent trimethylamine n-oxide pathway contributes to the bidirectional relationship between intestinal inflammation and periodontitis. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2023;12 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.1125463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molnarfi N, Benkhoucha M, Funakoshi H, Nakamura T, Lalive PH. Hepatocyte growth factor: a regulator of inflammation and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14:293–303. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao X, Liu W, Wu Z, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor is protective in early stage but bone-destructive in late stage of experimental periodontitis. J Periodontal Res. 2024;59:565–575. doi: 10.1111/jre.13237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao X, Liu W, Wu Z, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor is protective in early stage but bone-destructive in late stage of experimental periodontitis. Journal of Periodontal Research. 2024;59:565–575. doi: 10.1111/jre.13237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bennett JH, Morgan MJ, Whawell SA, et al. Metalloproteinase expression in normal and malignant oral keratinocytes: stimulation of MMP-2 and -9 by scatter factor. European Journal of Oral Sciences. 2001;108:281–291. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2000.108004281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Romandini P, Marruganti C, Romandini WG, Sanz M, Grandini S, Romandini M. Are periodontitis and dental caries associated? A systematic review with meta-analyses. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2023;51:145–157. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.13910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Y, Xiang Y, Ren H, et al. Association between periodontitis and dental caries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Oral Investigations. 2024;28:306. doi: 10.1007/s00784-024-05687-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rathnayake N, Åkerman S, Klinge B, et al. Salivary biomarkers of oral health – a cross-sectional study. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2012;40:140–147. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stefanantoni K, Sciarra I, Vasile M, et al. Elevated serum levels of macrophage migration inhibitory factor and stem cell growth factor β in patients with idiopathic and systemic sclerosis associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Reumatismo. 2015;66:270–276. doi: 10.4081/reumatismo.2014.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang Z, Yao X, Lan W, et al. Associations of the circulating levels of cytokines with risk of systemic sclerosis: a bidirectional Mendelian randomized study. Frontiers in Immunology. 2024;15 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1330560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li C, Tian Y, Dougarem D, Sun L, Zhong Z. Systemic inflammatory regulators and preeclampsia: a two-sample bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Frontiers in Genetics. 2024;15 doi: 10.3389/fgene.2024.1359579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santiago HdC, Wang Y, Wessel N, et al. Measurement of multiple cytokines for discrimination and risk stratification in patients with Chagas’ disease and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2021;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi C, Pamer EG. Monocyte recruitment during infection and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:762–774. doi: 10.1038/nri3070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Almeida LGN, Thode H, Eslambolchi Y, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases: from molecular mechanisms to physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev. 2022;74:712–768. doi: 10.1124/pharmrev.121.000349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mego M, Cholujova D, Minarik G, et al. CXCR4-SDF-1 interaction potentially mediates trafficking of circulating tumor cells in primary breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:127. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2143-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, Wessel N, Kohse F, et al. Measurement of multiple cytokines for discrimination and risk stratification in patients with Chagas' disease and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goswami R, Kaplan MH. A brief history of IL-9. The Journal of Immunology. 2011;186:3283–3288. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rauber S, Luber M, Weber S, et al. Resolution of inflammation by interleukin-9-producing type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Nature Medicine. 2017;23:938–944. doi: 10.1038/nm.4373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kar S, Gupta R, Malhotra R, et al. Interleukin-9 facilitates osteoclastogenesis in rheumatoid arthritis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021;22:10397. doi: 10.3390/ijms221910397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.