Abstract

AKAPs (A-kinase–anchoring proteins) act as scaffold proteins that anchor the regulatory subunits of the cAMP-dependent PKA (protein kinase A) to coordinate and compartmentalize signaling elements and signals downstream of Gs-coupled GPCRs (G protein–coupled receptors). The β2AR (β-2-adrenoceptor), as well as the Gs-coupled EP2 and EP4 (E-prostanoid) receptor subtypes of the EP receptor subfamily, are effective regulators of multiple airway smooth muscle (ASM) cell functions whose dysregulation contributes to asthma pathobiology. Here, we identify specific roles of the AKAPs Ezrin and Gravin in differentially regulating PKA substrates downstream of the β2AR, EP2R (EP2 receptor) and EP4R. Knockdown of Ezrin, Gravin, or both in primary human ASM cells caused differential phosphorylation of the PKA substrates VASP (vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein) and HSP20 (heat shock protein 20). Ezrin knockdown, as well as combined Ezrin and Gravin knockdown, significantly reduced the induction of phospho-VASP and phospho-HSP20 by β2AR, EP2R, and EP4R agonists. Gravin knockdown inhibited the induction of phospho-HSP20 by β2AR, EP2R, and EP4R agonists. Knockdown of Ezrin, Gravin, or both also attenuated histamine-induced phosphorylation of MLC20. Moreover, knockdown of Ezrin, Gravin, or both suppressed the inhibitory effects of Gs-coupled receptor agonists on cell migration in ASM cells. These findings demonstrate the role of AKAPs in regulating Gs-coupled GPCR signaling and function in ASM and suggest the therapeutic utility of targeting specific AKAP family members in the management of asthma.

Keywords: ASM, prostaglandin, G protein–coupled receptor, AKAPs, cell migration

Clinical Relevance

AKAPs (A-kinase–anchoring proteins) regulate signaling by G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) by coordinating the location of key signaling molecules. The findings of this study lend new insight into how AKAP subtypes in human airway smooth muscle function to regulate the signaling effected by GPCR agonists, such as exogenous β-agonist, and by prostaglandin E2 produced by the cell when subjected to inflammatory mediators. Such knowledge could be exploited to improve the therapeutic efficacy to prorelaxant and antiremodeling GPCR agonists for asthma.

AKAPs (A-kinase-anchoring proteins) are scaffold proteins that anchor the regulatory R-subunits of the cAMP-dependent kinase (a.k.a. PKA [protein kinase A]) to control the magnitude and localization of cAMP-PKA–dependent signaling (1, 2). AKAPs coordinate the localization of not only effectors (PKA, adenylyl cyclase) but also feedback regulators (phosphodiesterases, arrestins) of the Gs family of GPCRs (G protein–coupled receptors) such as the β2AR (β-2-adrenoceptor) and the prostaglandin-activated EP2 and EP4 receptors (3, 4).

Although much of our early understanding of AKAPs arose from studies using artificial cell lines, more recent studies of physiologically relevant cell types including brain (5) cardiac (6, 7), vascular (8), immune (9, 10), and airway smooth muscle (ASM) cells (2, 11, 12) have helped elucidate AKAP’s roles in regulating GPCR signaling and function. Studies in rat neonatal cardiomyocytes have reported that AKAPs such as AKAP100 (13) and mAKAP (14) are targeted to the nuclear membrane. AKAP-Lbc has been reported to induce phenylephrine-mediated cardiac hypertrophy, as downregulation of AKAP-Lbc via RNA interference inhibited phenylephrine-stimulated cardiac hypertrophy (7). Dransfield and coworkers reported that the AKAP Ezrin (a.k.a. AKAP78) is essential for tethering and regulating PKA near the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator in parietal cells (15). Ezrin knockdown in Jurkat T cells inhibited cAMP-mediated inhibition of T-cell proliferation and IL-2 production (16). Gravin (AKAP12) has been shown to inhibit prostatic hyperplasia in murine tissue (17). Gravin has also been reported to maintain vascular integrity in endothelial cells of zebrafish embryos. Gravin-null embryos possess severe hemorrhages compared with wild-type embryos (8). In studies of human umbilical vein endothelial cells, Gravin was shown to regulate actin cytoskeleton regulator-PAK2 and connector protein-AF6 to maintain endothelial cell integrity during vascular development (8).

Airway smooth muscle (ASM) is a cell type whose principal functions (contraction, proliferation, migration, and secretory) are frequently detrimental (to the point of having been described as dispensable, reinforcing the long-held notion that ASM is “vestigial” and justifying the use of thermal ablation [18–20]) and are key pathogenic drivers of the obstructive lung disease asthma. Moreover, cAMP/PKA-dependent signaling is the primary physiological and therapeutic means of inhibiting these functions, so an understanding of how such signaling is effected and regulated is paramount in the fields of airway and asthma biology and pharmacology. We have previously reported that, in human ASM cells, inhibition of all AKAPs with the AKAP disruptors Ht-31 or AKAP-IS results in no change in global measures of β-agonist–induced cellular cAMP or phosphorylation of PKA substrates (2). However, assessment of localized cAMP transients using adenovirus-mediated expression of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels, revealed that Ht-31 could significantly extend the duration of β-agonist–stimulated, plasma membrane–delineated cAMP transients, suggesting at the very least a role for AKAPs in regulating spatiotemporal features of cAMP accumulation and signaling in ASM.

Because our approach in the study of Horvat and colleagues (2) involved inhibition of all cellular AKAPs, and the collective effect of such could reflect the competing actions of AKAPs, it remained undetermined whether and how targeting specific AKAPs could sufficiently affect measures of GPCR signaling in ASM and in turn affect ASM function. Accordingly, in the present study, we tested the effects of targeting specific AKAPs in ASM on the signaling and function of multiple Gs-coupled GPCRs.

Methods

Reagents and Antibodies

Isoproterenol (Iso), PGE2 (prostaglandin E2), and primary antibody anti-AKAP12 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. EP2R agonist ONO-AE-259-01 and EP4R agonist ONO-AE-329 were provided by ONO Pharmaceuticals. In the following text and figures, they are referred to as ONO-259 and ONO-329, respectively. PDGF (platelet-derived growth factor) and primary antibodies against Ezrin and pMLC20 (myosin light chain 20) were purchased from CST. Antibody against phospho-HSP20 (pHSP20) was purchased from Abcam. Secondary antibodies used were anti-rabbit 800 or anti-mouse 680 purchased from LiCOR. All other agents were purchased from sources described previously (2, 21).

ASM Cell Culture and siRNA-mediated Knockdown of AKAPs

Airway smooth muscle cells were isolated from deidentified human tracheae and cultured in Ham’s F-12 media with 10% FBS as described previously (2, 22). ASM cells were transfected with siRNA oligos as described previously (22). Briefly, scrambled (Scr; control) siRNA (5′-GCG CGC UUU GUA GGA UUC GdTdT-3′), or Ezrin- or AKAP12-ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool siRNA were reconstituted using 1× siRNA buffer. The DharmaFECT-siRNA complex was prepared per the manufacturer’s instructions and added to ASM cells in serum-free F-12 media for 18 hours. The following day, cells were harvested and plated in 12- or 96-well tissue culture plates in complete F-12 media with 10% FBS per experimental requirements.

Signal Transduction and Immunoblotting

Control (Scr siRNA–transfected) and AKAP knockdown cells were harvested and plated 24 hours after transfection in 12-well dishes at a density of 45 × 103 per well in complete F-12 media. Cells were allowed to grow for 18 hours, and growth was arrested the next day for 24 hours in serum-free F-12 media. Cells were treated for 10 minutes with vehicle or Gs-coupled GPCR agonists as indicated, followed by a 10-minute stimulation with histamine (1 μM). The concentrations of Gs-coupled receptor agonists (Iso [1 µM], EP2R agonist ONO-259 [10 nM], EP4R agonist ONO-329 [10 nM]) were chosen based on previously identified demonstration of efficacy in regulating phosphorylation of MLC20 and the PKA substrates VASP (vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein) and HSP20 (23, 24). Concentrations of ONO-259 and ONO-329 were limited to 10 nM to ensure specificity of targeting EP2 and EP4 receptors, respectively (23). To assess changes in phosphorylated myosin light chain (pMLC20), samples were generated as described previously (25) and electrophoresed on 4–12% NuPAGE gels (Invitrogen), followed by a dry transfer. For all other proteins, samples were run on SDS gels and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane and blocked with 3% BSA for 1 hour, followed by overnight incubation with primary antibodies (1:1,000). The next day, membranes were washed with 1× Tris-buffered saline solution with Tween 20 and incubated for 1 hour with Li-COR secondary antibodies (1:10,000). Immunoreactive protein bands were quantified using the Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences). VASP phosphorylation was quantified as the percentage of total VASP (46-kD and 50-kD bands) represented by a species that migrates at 50 kD per previous reports (25, 26). Data for HSP20 and MLC20 phosphorylation are quantified by dividing the band intensity by the (matched) actin band intensity.

Gel Contraction Assay

Transfected ASM cells were harvested and resuspended in a mixture of collagen I and F-12 media with 0.1% FBS. A cell suspension of 50,000 per well was plated in 96-well plates and allowed to cure for 1 hour before adding F-12 media with 0.1% BSA to each well (27, 28). On the day of the experiment, gels were gently released from the edges of the well and imaged before the addition of vehicle or agonists. Gels were stimulated with agonists, and images were acquired for 10 minutes after each addition of agonist using the FL Auto Imaging System bright-field microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The gel images were used to calculate the area of the gel at each time point using ImageJ software. A free hand tool was used to highlight the edge of the gel, and the percentage change in the area of the collagen gel was calculated as a readout for ASM contraction.

Regulation of the Actin Cytoskeleton

Regulation of F- and G-actin by AKAPs was determined by immunofluorescence as described previously (29). Briefly, cells subjected to Ezrin and Gravin knockdown were treated with vehicle, histamine (1 μM), or PDGF (10 ng/ml) with or without Iso (1 μM) pretreatment. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, followed by labeling the F-actin with rhodamine-phalloidin (red) and G-actin with Alexa Fluor-DNase I (green) (Life Technologies). To determine changes in F/G ratio, cells were imaged, and fluorescence intensities were quantified using a Leica DMI 6000 microscope as described previously (21).

Cell Migration Assay

Transfected ASM cells were plated in Ibidi cell culture inserts at a density of 17 × 103. Cells were allowed to grow overnight, then growth was arrested using serum-free F-12 media the following day. On the day of the experiment, the insert was carefully removed and treated with Gs-coupled GPCR agonists for 10 minutes before the addition of PDGF. Images of the cells were acquired using the EVOS FL auto imaging system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) before and 3, 6, 18, and 24 hours after treatment with agonists. Images were analyzed using ImageJ as described previously (30). Briefly, 8-bit images were processed using the band-pass filter. After the threshold was adjusted, an additional minimum filter was used to highlight the cell edges. The area between cell edges was measured using the free hand wand tool. Percentage of migration was determined by measuring the area between the cell edges over different time points.

Regulation of Cytokine-induced PKA Activity

To assess the effect of combined Ezrin and Gravin knockdown on the PKA activity induced by IL-1β in the presence of EGF (epidermal growth factor) (31), cells subjected to Ezrin and Gravin knockdown were plated in a 12-well plate at a density of 45 × 103 cells per well in serum containing F12 media. The cells were starved in a serum-free media for 24 hours, washed three times in PBS solution, then treated with vehicle or EGF (10 ng/ml) plus IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for 24 hours. Lysates were collected, and COX-2 and pVASP levels were assessed by immunoblotting.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means ± SEM. Experiments employing human ASM cultures were repeated with cultures from n different donors. Statistically significant differences among vehicle/treatment groups were assessed by one-way or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis or Student’s t test where appropriate, with values of P < 0.05 sufficient to reject the null hypothesis, using Prism 7.0 software (GraphPad).

Results

Ezrin and Gravin Regulation of Gs-coupled GPCR Signaling in ASM Cells

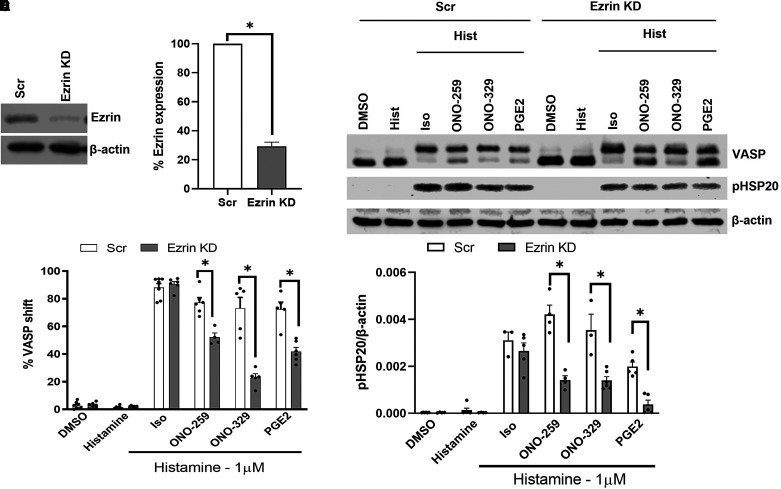

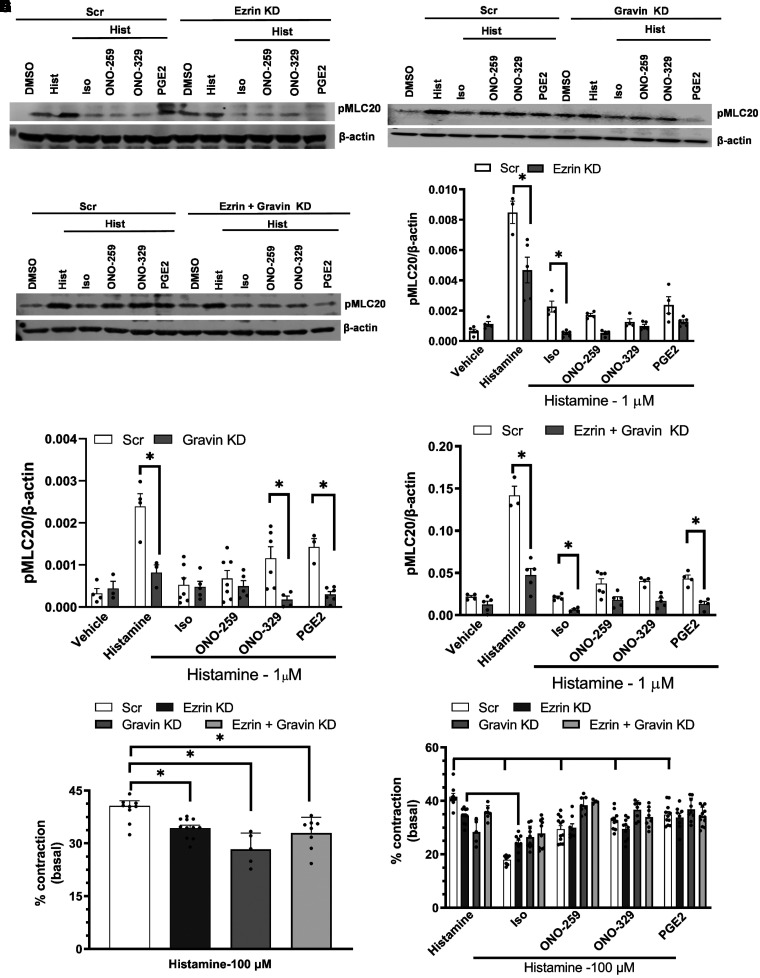

Human ASM cells transfected with Ezrin or Gravin SMARTpool siRNA exhibited >70% knockdown of Ezrin (Figures 1A and 1B) or Gravin (Figures 2A and 2B) per immunoblot analysis. Effects on Gs-coupled GPCR agonist–induced PKA activity (performed with histamine costimulation to allow for matched analyses of pMLC20 regulation and cell contraction; see below) was determined by analyzing changes in phosphorylation of the PKA substrates VASP and HSP20. ASM cells subjected to Ezrin knockdown had significantly reduced induction of phospho-VASP (pVASP; the slower-migrating 50-kD band) (Figures 1C and 1D) and pHSP20 (Figures 1C and 1E) in response to ONO-259, ONO-329, and PGE2, whereas Iso-stimulated levels were unaffected. Gravin knockdown significantly reduced pVASP levels induced by ONO-329 (Figures 2C and 2D) and significantly reduced pHSP20 levels in cells stimulated with each of the four stimuli (Figures 2C and 2E). Combined knockdown of Ezrin and Gravin resulted in an approximate 50–60% knockdown of Ezrin and 70–80% knockdown of Gravin (Figures 3A and 3B). Unlike individual AKAP knockdown, dual knockdown had a more profound effect on pVASP regulation, significantly reducing pVASP and pHSP20 levels induced by Iso, ONO-259, ONO-329, and PGE2 (Figures 3C and 3E).

Figure 1.

Ezrin regulates Gs/PKA (protein kinase A)–mediated signaling induced by EP (E-prostanoid) ligands. Airway smooth muscle (ASM) cells were transfected with Ezrin siRNA, and downregulation of Ezrin expression was confirmed by immunoblot (A and B). Agonist-induced PKA activation was analyzed based on changes in phosphorylation of VASP (vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein) and HSP20 (heat shock protein) (C). VASP phosphorylation was significantly reduced in Ezrin-knockdown (KD) ASM cells stimulated with ONO-259 (10 nM), ONO-329 (10 nM), and PGE2 (prostaglandin E2; 10 nM), but not isoproterenol (Iso; 1 μM) (D). Phospho-HSP20 levels were significantly reduced in Ezrin-KD ASM cells treated with ONO-259, ONO-329, and PGE2 (E). N = 4–5 primary ASM cell cultures *P < 0.05, control scrambled (Scr) siRNA– versus Ezrin siRNA–transfected cells. Hist = histamine.

Figure 2.

Gravin regulates Gs/PKA-mediated signaling induced by β2AR and EPR ligands. KD of Gravin expression in ASM cells by siRNA transfection was confirmed by immunoblot (A) and quantified (B). PKA activity was analyzed by changes in phosphorylation of VASP and HSP20 (C). VASP phosphorylation was significantly reduced in Gravin-KD ASM cells stimulated with ONO-329 (10 nM) (D). Phospho-HSP20 levels were significantly reduced in Gravin-KD ASM cells preincubated with Iso (1 μM), ONO-259 (10 nM), ONO-329 (10 nM), and PGE2 (10 nM) (E). N = 4–5 primary ASM cell cultures. * P < 0.05 Scr siRNA– versus Gravin siRNA–transfected cells.

Figure 3.

Ezrin and Gravin regulate Gs/PKA-signaling induced by β2AR and EPR ligands. KD efficiency of Gravin and Ezrin in primary ASM cells by siRNA transfection was confirmed by immunoblotting (A and B). Agonist-induced PKA activation was analyzed by changes in phosphorylation of VASP and HSP20 (C). VASP phosphorylation was significantly reduced in Ezrin plus Gravin KD ASM cells stimulated with Iso (1 μM), ONO-259 (10 nM), ONO-329 (10 nM), and PGE2 (10 nM) compared with Scr-siRNA transfected cells (D). Phospho-HSP20 levels were significantly reduced by KD of Ezrin and Gravin in ASM cells stimulated with Iso, ONO-259, and PGE2 (E). N = 3–5 primary ASM cell cultures. *P < 0.05 Scr siRNA– versus AKAP (A-kinase–anchoring proteins) siRNA–transfected ASM cells.

Ezrin and Gravin Knockdown Effects on the Regulation of ASM Procontractile Signaling and Contraction

Consistent with previous studies (23–25), treatment with all tested Gs-coupled GPCR agonists significantly inhibited the induction of pMLC20 levels (Figures 4A–4F) and ASM gel contraction (Figures 4G–4H) stimulated by the procontractile agonist histamine in control (Scr siRNA–transfected) ASM cells. Interestingly, knockdown of Ezrin (Figures 4A and 4D), Gravin (Figures 4B and 4E), or both (Figures 4C and 4F) significantly reduced the pMLC20 induction and ASM contraction (Figures 4G and 4H) by histamine in control cells, and this effect predictably constrained the ability to interpret knockdown effects on the ability of Gs-coupled receptor agonists to inhibit histamine-induced pMLC20 levels and ASM contraction (Figures 4G and 4H). Cells subjected to Ezrin knockdown showed significantly decreased histamine-induced pMLC20 levels when treated with Iso compared with Iso-treated Scr siRNA–transfected cells. In cells subjected to Ezrin knockdown, a further decrease in histamine-induced pMLC20 levels was observed when treated with all Gs-coupled GPCR agonists compared with Ezrin-knockdown cells treated only with histamine (Figure 4D). Cells subjected to Gravin knockdown had significantly reduced histamine-induced pMLC20 levels in cells treated with PGE2 and ONO-329 compared with control cells treated with the other Gs-coupled GPCR agonists (Figure 4E). Knockdown of Ezrin and Gravin resulted in significantly decreased histamine-induced pMLC20 levels in cells treated with Iso and PGE2 compared with control cells. In gel contraction assays performed in parallel, knockdown of Ezrin, Gravin, or both significantly reduced histamine-stimulated contraction compared with control cells (Figures 4G and 4H). The percentage of histamine-stimulated contraction was measured by assessing the difference between the area of the gel before and after histamine addition. In control cells, each of the Gs-coupled GPCR agonists significantly reduced histamine-stimulated gel contraction (Figure 4H). In cells subjected to Ezrin knockdown, Iso, but not ONO-259, ONO-329, or PGE2, retained the ability to significantly inhibit histamine-induced contraction. In cells subjected to Gravin knockdown or combined Gravin and Ezrin knockdown, all agents lost the ability to inhibit histamine-induced contraction (Figure 4H).

Figure 4.

Reduced expression of AKAP(s) does not affect β2AR or EPR regulation of ASM pMLC20 (myosin light chain 20) and cell contraction. ASM cells in which Ezrin (A), Gravin (B), or both (C) were knocked down were analyzed for changes in Gq-coupled GPCR-regulated pMLC20 induction. Induction of pMLC20 by histamine was significantly reduced by all Gs-coupled GPCR agonists in Scr siRNA–transfected ASM cells. Induction of pMLC20 by histamine was significantly reduced by KD of Ezrin (D), Gravin (E), or both (F). KD of Ezrin further augmented the reduction of pMLC20 by Iso (1 μM), ONO-259 (10 nM), ONO-329 (10 nM), and PGE2 (10 nM) (D). KD of Gravin did not significantly affect β2AR-, EP2-, or EP4-mediated inhibition of MLC20 phosphorylation (E). Cells with Ezrin and Gravin KD had significantly reduced pMLC20 by Iso (F). ASM cells with Ezrin, Gravin, or Ezrin plus Gravin KD plated in a collagen gel matrix had significantly reduced percentages of contraction compared with Scr cells when stimulated by histamine alone (G). Treatment with Iso, ONO-259, or ONO-329 significantly inhibited histamine-stimulated contraction in Scr cells (H). Iso treatment significantly enhanced the inhibition of histamine-stimulated contraction in Ezrin-KD cells. Cells with Gravin or Ezrin plus Gravin KD treated with Iso, ONO-259, or ONO-329 had no significant change in histamine-stimulated contraction relative to histamine-alone stimulation (H). N = 4–5 primary ASM cultures. *P < 0.05, Scr siRNA–transfected versus AKAP siRNA–transfected ASM cells. †P < 0.05, Scr siRNA–transfected ASM cells treated with histamine versus Scr siRNA–transfected ASM cells treated with Gs-coupled GPCR agonist. ‡P < 0.05, AKAP siRNA–transfected cells treated with histamine versus AKAP siRNA–transfected ASM cells treated with Gs-coupled GPCR agonist.

Ezrin and Gravin Knockdown Effects on Regulation of ASM Cell Migration

Transfected ASM cells plated in Ibidi inserts were assessed for percentage migration over a period of 24 hours (Figure 5A). Cells were briefly cultured in serum-free media, followed by PDGF treatment with or without Gs-coupled GPCR agonists. Under unstimulated (vehicle-treated) conditions, basal migration was low in all groups, but was increased in cells subjected to knockdown of Ezrin, Gravin, or both compared with Scr siRNA–transfected (control) ASM cells (Figure 5B). PDGF significantly increased migration in control cells compared with vehicle-treated cells and in PDGF-treated Ezrin, Gravin, or combined knockdown cells (Figure 5C). In control cells, each of the Gs-coupled GPCR agonists significantly reduced PDGF-stimulated migration (Figure 5C). Except in Ezrin-knockdown cells treated with Iso, knockdown of Ezrin, Gravin, or both caused each of the GPCR agonists to lose their inhibitory effect on PDGF-stimulated migration. All Gs-coupled GPCR agonist–mediated inhibition of migration was absent in Gravin- or combined-knockdown cells (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

AKAPs regulate β2AR and EPR agonist–mediated inhibition of ASM cell migration. Scr- and AKAP(s) siRNA–transfected ASM cells were plated in Ibidi inserts, starved for 24 hours, then pretreated with vehicle, Iso (1 μM), PGE2 (10 nM), ONO-259 (10 nM), or ONO-329 (10 nM) for 10 minutes, followed by treatment with 10 ng/ml platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF). Images were acquired before and 24 hours after treatment (A) and quantified using ImageJ (B). Scale bars, 600 μm. Ezrin, Gravin, or Ezrin plus Gravin KD significantly increased migration in PDGF-stimulated (vs. vehicle) cells. Iso, PGE2, ONO-259, or ONO-329 treatment significantly inhibited PDGF-stimulated migration in Scr cells (C). Ezrin KD significantly enhanced the inhibitory effect of Iso on PDGF-stimulated migration. N = 3–5 primary ASM cultures. **P < 0.05, Scr siRNA–transfected untreated cells versus AKAP siRNA–transfected untreated ASM cells. *P < 0.05, Scr siRNA–transfected untreated cells versus AKAP siRNA–transfected PDGF treated ASM cells. †P < 0.05 Scr siRNA–transfected cells treated with PDGF versus Scr siRNA cells treated with Gs-coupled GPCR agonist. ‡P < 0.05, Ezrin siRNA–transfected cells treated with PDGF versus Ezrin siRNA–transfected ASM cells treated with Gs-coupled GPCR agonist.

Ezrin and Gravin Knockdown Effects on Regulation of Actin Cytoskeleton

To gain further mechanistic insight to the aforementioned effects of Ezrin and Gravin knockdown on ASM contraction and migration, we examined regulation of the actin cytoskeleton by Ezrin or Gravin by immunostaining ASM cells with rhodamine-phalloidin and Alexa-488 DNase I to stain F- and G-actin, respectively. Changes in fluorescence intensities following vehicle, histamine, or PDGF treatment with or without Iso were quantified. Representative images and quantification (Figure 6) show no significant difference in F/G ratio between Scr and Ezrin plus Gravin knockdown cells treated with vehicle, histamine, or PDGF. Iso induced a significant reduction in F/G actin ratio in histamine-treated Scr cells. However, this effect was significantly reversed in Ezrin plus Gravin knockdown cells, suggesting a mechanism for the higher contraction percentage seen in the Iso-pretreated Ezrin and Gravin knockdown cells compared with Iso-pretreated Scr cells in the gel contraction assay (Figure 4H).

Figure 6.

Reduced expression of AKAP(s) affects β2AR regulation of the ASM F/G actin ratio. Scr and Ezrin plus Gravin siRNA–transfected ASM cells treated with vehicle, histamine (1 μM), or PDGF (10 ng/ml) for 10 minutes with or without pretreatment with Iso (1 μM) for 10 minutes. Images were acquired (A), and fluorescence intensities of rhodamine-phalloidin and DNase I were quantified to determine F/G actin ratio (B). Iso-pretreated Scr siRNA–transfected cells were significantly decreased versus histamine-treated Scr siRNA–transfected cells. Iso-pretreated Ezrin plus Gravin KD had a significantly increased F/G actin ratio versus Scr siRNA–transfected ASM cells. Scale bars, 50 μm. N = 6 primary ASM cultures. *P < 0.05, Iso-treated Scr siRNA–transfected cells versus histamine-treated Scr siRNA–transfected cells. *P < 0.05, Iso-treated Scr siRNA–transfected cells versus Ezrin plus Gravin siRNA–transfected cells.

Ezrin and Gravin Knockdown Cells Regulate PKA Activity in EGF- and IL-1β–treated ASM Cells

Finally, to explore the effects of Ezrin and Gravin knockdown under conditions relevant to asthma and/or allergic inflammation, we treated human ASM cells with EGF and IL-1β for 24 hours. EGF and IL-1β levels are increased in BAL fluid from asthmatic patients (32–34), and previous studies by our laboratory have demonstrated that treatment of ASM with these agents together induces significant ASM PKA activity via the induction of COX-2 and PGE2 (31). A representative immunoblot (Figure 7A) and respective quantification (Figure 7B) show that EGF plus IL-1 treatment induced PKA activity, resulting in pVASP induction, with Ezrin plus Gravin knockdown inhibiting this induction despite having no effect on COX-2 induction.

Figure 7.

Ezrin and Gravin KD cells regulate PKA activity in EGF- and IL-1β–treated ASM cells. Scr and Ezrin plus Gravin siRNA–transfected ASM cells treated with vehicle or EGF (10 ng/ml) plus IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for 24 hours. Protein lysate was analyzed by immunoblot (A) and quantified (B) for phosphorylation of VASP and (C) COX2. EGF- and IL-1β–treated Ezrin plus Gravin KD cells had significantly reduced pVASP versus treated Scr cells. N = 3–6 primary ASM cell cultures. *P < 0.05, Scr siRNA– versus Ezrin plus Gravin siRNA–transfected cells.

Discussion

The findings of the present study demonstrate, for the first time, the key roles of the AKAPs Ezrin and Gravin in regulating Gs-coupled GPCR signaling in ASM cells and the physiological relevance of such regulation. Previously, our laboratory demonstrated that targeting all AKAPs in ASM cells with Ht-31 or the in silico–designed AKAP-IS did not affect β2AR-mediated whole-cell cAMP accumulation or the induction of (PKA-phosphorylated) p-VASP (2). However, Morgan and colleagues also revealed that Ht-31 regulated localized cAMP levels, as Ht-31 extended the duration of Iso-stimulated cAMP transients near the plasma membrane, prompting the more expansive assessment of AKAP-dependent regulation of ASM Gs-coupled GPCR signaling and associated functional effects presented herein.

As noted above, because cAMP/PKA signaling is the principal physiological and therapeutic means of inhibiting pathological ASM functions, understanding the cellular mechanisms that regulate the magnitude or duration of such signaling has been of intense interest to lung and lung disease research for decades (4, 35, 36). We and others have demonstrated that targeting various mechanisms of β2AR desensitization, such as GRK (GPCR kinase) or arrestin-mediated desensitization, causes augmented ASM cAMP/PKA signaling, and, importantly, this effect on signaling translates into an increased ability of β-agonists to relax contracted ASM in cell, tissue, and in vivo models (37–40). Only recently, however, have adequate tools for characterizing compartmentalized signaling emerged to investigate whether mechanisms affecting localization of signaling exist and are of any consequence. Studies in rat hippocampal neurons (41), murine primary cells of the kidney cortical collecting ducts (42), human aortic smooth muscle cells (43), and human embryonic kidney 293 cells (44) have shown that Ht-31 or AKAP-IS competes with AKAPs to bind to the RII subunit of PKA to perturb the RII-AKAP compartmentalization (45). Ht-31 and AKAP-IS can, however, bind and activate the RI subunit instead of RII in addition to allowing the aberrant compartmentalization of PKA and its activity (46). Disruption of RII-AKAP using Ht-31 results in inhibition of PKA-mediated regulation of AMAP (a-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methly-4-isoxazole-propionic acid)/Kainate and fast excitatory synaptic currents in rat hippocampal neurons. In human aortic smooth muscle, Ht31 significantly attenuates PGE2-mediated PKA phosphorylation activity; however, in mouse cortical collecting duct cells, Ht-31 increases PKA phosphorylation without affecting cAMP levels. We previously found no significant effect of either drug on the indices of PKA activity in whole-cell lysates of human ASM (2).

β2ARs have been shown to reside in the same lipid rafts with adenylyl cyclases (such as AC6), which dictate the second messenger response by regulating the spatial temporal compartmentalization of cAMP-PKA (47). EP2/4 receptors induce a cAMP response, yet appear to reside in raft and nonraft domains. AKAP subtypes can vary in location, but most tend to be diffuse in the cytosol, and they coordinate multiple proteins (kinases, PDEs, even effectors like AC) in locales presumably near substrates to address cell needs. Our data do indeed suggest that the (differential) regulation of PKA substrates VASP and HSP20 by Ezrin and Gravin involve compartmentalization. In vascular smooth muscle cells, VASP was reported to localize in complex with Ezrin near the microtubules and dense bodies, allowing Ezrin-VASP to coordinate the assembly of the actomyosin complex (48, 49). In human endothelial cells, Gravin was reported to complex with VASP near junctional barriers to regulate junctional permeability (50). Our data seem to suggest that Gravin may play a greater role (vs. Ezrin) in coordinating PKA phosphorylation of HSP20 mediated by most Gs-coupled GPCRs; perhaps Gravin has a more diffused cytosolic distribution, enabling this effect (51).

We (2) and others (11, 12) have identified AKAP9, AKAP12 (Gravin), AKAP78 (Ezrin), AKAP5, and AKAP2 as the most abundantly expressed AKAPs in human ASM. Previously published data from the Schmidt laboratory suggest that AKAPs may be targeted therapeutically to manage ASM contractility in obstructive lung diseases. Baarsma and coworkers reported that human ASM cells treated with Ht-31 had reduced mRNA and protein levels of AKAP8, which were associated with increased cell cycle progression as evidenced by increased incorporation of 3H-thymidine and increased cyclin D1 levels (11). Ht-31 treatment also induced an increase in contractile proteins SMA and calponin in cultured human ASM cells and human tracheal tissue, and human tracheal rings incubated with Ht-31 were hypercontractile compared with their respective controls (11). Moreover, changes in AKAP expression may play a role in the pathobiology of lung diseases; Poppinga and coworkers reported that ASM cells from patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and those treated with cigarette smoke had reduced levels of AKAP(s), which affected the efficacy of inhaled antiinflammatory and anticholinergic agents (12).

The effect of knockdown of individual AKAP(s) on the regulation of PKA in human ASM cells is yet unknown, and the few studies to date exploring AKAPs in ASM have been descriptive or limited to characterizing the effects of Ht-31 or AKAP-IS. Because our previous study suggested that competing actions of AKAP subtypes that may compromise any therapeutic effect of global AKAP inhibition (2), here we chose the approach of subtype-selective targeting. In the present study, we demonstrate that specific targeting of Ezrin or Gravin is capable of significantly regulating, albeit somewhat variably, the phosphorylation of two important PKA substrates, VASP and HSP20, in ASM cells, and that such regulation results in a loss of the inhibitory effect of various Gs-coupled GPCR agonists on ASM cell migration. Interpretation of the effects of knockdown of Ezrin, Gravin, or both on the prorelaxant effect of Gs-coupled GPCRs was confounded by the significant effect of knockdown on histamine-stimulated MLC20 phosphorylation and contraction in the absence of prorelaxant agonists.

Increases in ASM mass, a hallmark of airway remodeling in asthma, are believed to be dependent on ASM proliferation, hypertrophy, and migration (52–56). Thus, the ability of knockdown of Ezrin, Gravin, or both to inhibit the phosphorylation of VASP by β2AR, EP2R, or EP4R stimulation is mechanistically consistent with this observation and suggests that Ezrin and Gravin control the spatiotemporal features of PKA activity promoted by these receptors to facilitate VASP-dependent regulation of ASM migration. VASP has been reported to act as an actin stabilizer, and, upon phosphorylation, gets localized at the membrane, where it complexes with actin via vinculin (57). Similarly, phosphorylation of HSP20 has been shown to play a role in the migration of smooth muscle cells in different animal models in which relaxation is regulated by the phosphorylation of serine 16 of HSP20 (58–60). HSP20, especially in its phosphorylated form, has been reported to inhibit migration in hepatocellular carcinoma cells upon treatment with TGF-α (61), essentially through regulation of the actin cytoskeleton (62). The exact mechanism involving phosphorylated HSP20 in relaxing smooth muscle remains unclear, possibly involving cytoskeleton regulation by inducing F-actin depolymerization via dephosphorylation of cofilin (58, 63). Although knockdown of Ezrin plus Gravin failed to alter the F/G actin ratio under conditions of PDGF plus Iso stimulation (Figure 6), this result likely reflects the fact that AKAPs regulate actin in discrete locations (leading and lagging edge) during migration, when quantitative whole cell changes do not occur.

Additionally, our data suggest that AKAPs regulate PKA activity mediated by cytokine-induced COX-2, as Ezrin plus Gravin knockdown cells had significantly reduced pVASP levels after chronic EGF and IL-1β treatment (Figure 7). Previous studies have shown that 18 hours of treatment of human ASM with EGF plus IL-1β induces COX-2 (31) that mediates inhibition of growth factor– and serum-dependent cell proliferation (53) and migration (64). Herein we observed that the inhibitory effect of Ezrin and Gravin knockdown on pVASP induction by EGF and IL-1β occurred in the absence of any effect on COX-2 induction, suggesting that the regulation of PKA activity occurred via the mechanisms observed for EP2/EP4 regulation. Thus, beyond regulating the signaling and functional efficacy of β-agonists, Ezrin and Gravin regulate the cell biology of ASM in response to inflammatory mediators.

Conversely, the regulation of subcellular PKA activity by Ezrin and Gravin may not be critical to PKA-dependent regulation of ASM contraction. The inhibition of histamine-stimulated phosphorylation of MLC20 by β2AR, EP2R, and EP4R was still preserved, and, in some instances, was augmented by Ezrin and Gravin knockdown. Again, that Ezrin and Gravin knockdown significantly decreased the inhibition of histamine-stimulated phosphorylation of MLC20 in the absence of Gs-coupled GPCR activation complicates interpretation. Why such inhibition occurs is unclear; previous studies in human erythroleukemia cells (65), human breast carcinoma (MCF-7) cells (66), and rat intercostal muscle tissue (67) have demonstrated the ability of AKAPs to bind and coordinate PKC activity (68), and PKC activity is known to contribute to MLC20 phosphorylation and ASM contraction (35, 69).

In summary, our study demonstrates for the first time that inhibition of ASM cell migration mediated by Gs-coupled receptor agonists is regulated by AKAPs, likely mechanistically linked to the PKA-dependent regulation of VASP and HSP20. Additional characterization of AKAP-dependent regulation of ASM GPCR signaling and function, and of the effect of other regulators of signaling compartmentalization such as phosphodiesterases (70) and lipid rafts (71), will likely identify strategies to enhance the therapeutic signaling capacity of GPCR ligands in obstructive lung diseases.

Footnotes

Supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants HL058506 and HL169522 (R.B.P.), HL145392 (R.B.P. and D.D.T), HL153602 (A.P.N.), and HL150560 and HL137030 (D.A.D).

Author Contributions: R.B.P. and D.A.D.: conceptualization, project administration, supervision. E.J., A.P.N., A.H.C., I.D., A.K.J., R.W., and D.D.T.: performing experiments, data curation, writing original draft. R.B.P., D.A.D., A.P.N., E.J., A.H.C., I.D., and A.K.J.: reviewing and editing.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2023-0358OC on August 14, 2024

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Diviani D, Dodge-Kafka KL, Li J, Kapiloff MS. A-kinase anchoring proteins: scaffolding proteins in the heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol . 2011;301:H1742–H1753. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00569.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Horvat SJ, Deshpande DA, Yan H, Panettieri RA, Codina J, DuBose TD, Jr, et al. A-kinase anchoring proteins regulate compartmentalized camp signaling in airway smooth muscle. FASEB J . 2012;26:3670–3679. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-201020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stangherlin A, Zaccolo M. Local termination of 3′-5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate signals: the role of A kinase anchoring protein–tethered phosphodiesterases. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol . 2011;58:345–353. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3182214f2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Penn RB. Embracing emerging paradigms of g protein-coupled receptor agonism and signaling to address airway smooth muscle pathobiology in asthma. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol . 2008;378:149–169. doi: 10.1007/s00210-008-0263-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sanderson JL, Dell’Acqua ML. AKAP signaling complexes in regulation of excitatory synaptic plasticity. Neuroscientist . 2011;17:321–336. doi: 10.1177/1073858410384740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mauban JR, O’Donnell M, Warrier S, Manni S, Bond M. AKAP-scaffolding proteins and regulation of cardiac physiology. Physiology (Bethesda) . 2009;24:78–87. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00041.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Appert-Collin A, Cotecchia S, Nenniger-Tosato M, Pedrazzini T, Diviani D. The A-kinase anchoring protein (AKAP)-Lbc-signaling complex mediates alpha1 adrenergic receptor-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A . 2007;104:10140–10145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701099104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kwon HB, Choi YK, Lim JJ, Kwon SH, Her S, Kim HJ, et al. AKAP12 regulates vascular integrity in zebrafish. Exp Mol Med . 2012;44:225–235. doi: 10.3858/emm.2012.44.3.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Troger J, Moutty MC, Skroblin P, Klussmann E. A-kinase anchoring proteins as potential drug targets. Br J Pharmacol . 2012;166:420–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01796.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gordon T, Grove B, Loftus JC, O’Toole T, McMillan R, Lindstrom J, et al. Molecular cloning and preliminary characterization of a novel cytoplasmic antigen recognized by myasthenia gravis sera. J Clin Invest . 1992;90:992–999. doi: 10.1172/JCI115976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Baarsma HA, Han B, Poppinga WJ, Driessen S, Elzinga CRS, Halayko AJ, et al. Disruption of AKAP-PKA interaction induces hypercontractility with concomitant increase in proliferation markers in human airway smooth muscle. Front Cell Dev Biol . 2020;8:165. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Poppinga WJ, Heijink IH, Holtzer LJ, Skroblin P, Klussmann E, Halayko AJ, et al. A-kinase-anchoring proteins coordinate inflammatory responses to cigarette smoke in airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol . 2015;308:L766–L775. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00301.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yang J, Drazba JA, Ferguson DG, Bond M. A-kinase anchoring protein 100 (AKAP100) is localized in multiple subcellular compartments in the adult rat heart. J Cell Biol . 1998;142:511–522. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.2.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kapiloff MS, Schillace RV, Westphal AM, Scott JD. mAKAP: an A-kinase anchoring protein targeted to the nuclear membrane of differentiated myocytes. J Cell Sci . 1999;112(pt 16):2725–2736. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.16.2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dransfield DT, Bradford AJ, Smith J, Martin M, Roy C, Mangeat PH, et al. Ezrin is a cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase anchoring protein. EMBO J . 1997;16:35–43. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ruppelt A, Mosenden R, Gronholm M, Aandahl EM, Tobin D, Carlson CR, et al. Inhibition of T cell activation by cyclic adenosine 5′-monophosphate requires lipid raft targeting of protein kinase A type I by the A-kinase anchoring protein ezrin. J Immunol . 2007;179:5159–5168. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Akakura S, Huang C, Nelson PJ, Foster B, Gelman IH. Loss of the ssecks/gravin/akap12 gene results in prostatic hyperplasia. Cancer Res . 2008;68:5096–5103. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cox PG, Miller J, Mitzner W, Leff AR. Radiofrequency ablation of airway smooth muscle for sustained treatment of asthma: preliminary investigations. Eur Respir J . 2004;24:659–663. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00054604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mitzner W. Airway smooth muscle: the appendix of the lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2004;169:787–790. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200312-1636PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirst SJ. In: Encyclopedia of respiratory medicine. Laurent GJ, Shapiro SD, editors. Oxford, UK: Academic Press; 2006. Smooth muscle cells | airway; pp. 96–105. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nayak AP, Lim JM, Arbel E, Wang R, Villalba DR, Nguyen TL, et al. Cooperativity between beta-agonists and c-Abl inhibitors in regulating airway smooth muscle relaxation. FASEB J . 2021;35:e21674. doi: 10.1096/fj.202100154R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Saxena H, Deshpande DA, Tiegs BC, Yan H, Battafarano RJ, Burrows WM, et al. The GPCR OGR1 (GPR68) mediates diverse signalling and contraction of airway smooth muscle in response to small reductions in extracellular pH. Br J Pharmacol . 2012;166:981–990. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01807.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Michael JV, Gavrila A, Nayak AP, Pera T, Liberato JR, Polischak SR, et al. Cooperativity of E-prostanoid receptor subtypes in regulating signaling and growth inhibition in human airway smooth muscle. FASEB J . 2019;33:4780–4789. doi: 10.1096/fj.201801959R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yan H, Deshpande DA, Misior AM, Miles MC, Saxena H, Riemer EC, et al. Anti-mitogenic effects of beta-agonists and PGE2 on airway smooth muscle are PKA dependent. FASEB J . 2011;25:389–397. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-164798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nayak AP, Javed E, Villalba DR, Wang Y, Morelli HP, Shah SD, et al. Pro-relaxant EP receptors functionally partition to different pro-contractile receptors in airway smooth muscle. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol . 2023;69:584–591. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2022-0445OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goncharova EA, Goncharov DA, Zhao H, Penn RB, Krymskaya VP, Panettieri RA., Jr Beta2-adrenergic receptor agonists modulate human airway smooth muscle cell migration via vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol . 2012;46:48–54. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0217OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shah SD, Lind C, De Pascali F, Penn RB, MacKerell AD, Jr, Deshpande DA. In silico identification of a beta(2)-adrenoceptor allosteric site that selectively augments canonical beta(2)AR-GS signaling and function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A . 2022;119:e2214024119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2214024119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Harford TJ, Rezaee F, Gupta MK, Bokun V, Naga Prasad SV, Piedimonte G. Respiratory syncytial virus induces beta(2)-adrenergic receptor dysfunction in human airway smooth muscle cells. Sci Signal . 2021;14:eabc1983. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.abc1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nayak AP, Javed E, Villalba DR, Wang Y, Morelli HP, Shah SD, et al. Prorelaxant E-type prostanoid receptors functionally partition to different procontractile receptors in airway smooth muscle. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol . 2023;69:584–591. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2022-0445OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Venter C, Niesler CU. Rapid quantification of cellular proliferation and migration using ImageJ. Biotechniques . 2019;66:99–102. doi: 10.2144/btn-2018-0132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pascual RM, Carr EM, Seeds MC, Guo M, Panettieri RA, Jr, Peters SP, et al. Regulatory features of interleukin-1beta-mediated prostaglandin E2 synthesis in airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol . 2006;290:L501–L508. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00420.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nayak AP, Deshpande DA, Penn RB. New targets for resolution of airway remodeling in obstructive lung diseases. F1000Res . 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-680. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.14581.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Puddicombe SM, Polosa R, Richter A, Krishna MT, Howarth PH, Holgate ST, et al. Involvement of the epidermal growth factor receptor in epithelial repair in asthma. FASEB J . 2000;14:1362–1374. doi: 10.1096/fj.14.10.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhang S, Fan Y, Qin L, Fang X, Zhang C, Yue J, et al. Il-1beta augments TGF-beta inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition of epithelial cells and associates with poor pulmonary function improvement in neutrophilic asthmatics. Respir Res . 2021;22:216. doi: 10.1186/s12931-021-01808-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Billington CK, Penn RB. Signaling and regulation of g protein-coupled receptors in airway smooth muscle. Respir Res . 2003;4:2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Billington CK, Ojo OO, Penn RB, Ito S. Camp regulation of airway smooth muscle function. Pulm Pharmacol Ther . 2013;26:112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pera T, Hegde A, Deshpande DA, Morgan SJ, Tiegs BC, Theriot BS, et al. Specificity of arrestin subtypes in regulating airway smooth muscle G protein-coupled receptor signaling and function. FASEB J . 2015;29:4227–4235. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-273094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gupta MK, Asosingh K, Aronica M, Comhair S, Cao G, Erzurum S, et al. Defective resensitization in human airway smooth muscle cells evokes beta-adrenergic receptor dysfunction in severe asthma. PLoS One . 2015;10:e0125803. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nino G, Hu A, Grunstein JS, Grunstein MM. Mechanism regulating proasthmatic effects of prolonged homologous beta2-adrenergic receptor desensitization in airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol . 2009;297:L746–L757. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00079.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. An SS, Wang WC, Koziol-White CJ, Ahn K, Lee DY, Kurten RC, et al. Tas2r activation promotes airway smooth muscle relaxation despite beta(2)-adrenergic receptor tachyphylaxis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol . 2012;303:L304–L311. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00126.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rosenmund C, Carr DW, Bergeson SE, Nilaver G, Scott JD, Westbrook GL. Anchoring of protein kinase a is required for modulation of AMPA/kainate receptors on hippocampal neurons. Nature . 1994;368:853–856. doi: 10.1038/368853a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ando F, Mori S, Yui N, Morimoto T, Nomura N, Sohara E, et al. AKAPs-PKA disruptors increase AQP2 activity independently of vasopressin in a model of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Nat Commun . 2018;9:1411. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03771-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Taylor EJA, Pantazaka E, Shelley KL, Taylor CW. Prostaglandin E2 inhibits histamine-evoked Ca(2+) release in human aortic smooth muscle cells through hyperactive cAMP signaling junctions and protein kinase A. Mol Pharmacol . 2017;92:533–545. doi: 10.1124/mol.117.109249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Alto NM, Soderling SH, Hoshi N, Langeberg LK, Fayos R, Jennings PA, et al. Bioinformatic design of a-kinase anchoring protein-in silico: a potent and selective peptide antagonist of type II protein kinase A anchoring. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A . 2003;100:4445–4450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0330734100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Burton KA, Johnson BD, Hausken ZE, Westenbroek RE, Idzerda RL, Scheuer T, et al. Type II regulatory subunits are not required for the anchoring-dependent modulation of Ca2+ channel activity by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A . 1997;94:11067–11072. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.11067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Motawea HK, Blazek AD, Zirwas MJ, Pleister AP, Ahmed AA, McConnell BK, et al. Delocalization of endogenous A-kinase antagonizes Rap1-Rho-alpha2c-adrenoceptor signaling in human microvascular smooth muscle cells. J Cytol Mol Biol . 2014;1:1000002. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bogard AS, Adris P, Ostrom RS. Adenylyl cyclase 2 selectively couples to E prostanoid type 2 receptors, whereas adenylyl cyclase 3 is not receptor-regulated in airway smooth muscle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther . 2012;342:586–595. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.193425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Markert T, Krenn V, Leebmann J, Walter U. High expression of the focal adhesion- and microfilament-associated protein VASP in vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells of the intact human vessel wall. Basic Res Cardiol . 1996;91:337–343. doi: 10.1007/BF00788712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Buenaventura RGM, Merlino G, Yu Y. Ez-metastasizing: the crucial roles of ezrin in metastasis. Cells . 2023;12:1620. doi: 10.3390/cells12121620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Weissmuller T, Glover LE, Fennimore B, Curtis VF, MacManus CF, Ehrentraut SF, et al. HIF-dependent regulation of AKAP12 (gravin) in the control of human vascular endothelial function. FASEB J . 2014;28:256–264. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-238741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Guillory AN, Yin X, Wijaya CS, Diaz Diaz AC, Rababa’h A, Singh S, et al. Enhanced cardiac function in gravin mutant mice involves alterations in the beta-adrenergic receptor signaling cascade. PLoS One . 2013;8:e74784. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gerthoffer WT. Migration of airway smooth muscle cells. Proc Am Thorac Soc . 2008;5:97–105. doi: 10.1513/pats.200704-051VS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Misior AM, Yan H, Pascual RM, Deshpande DA, Panettieri RA, Penn RB. Mitogenic effects of cytokines on smooth muscle are critically dependent on protein kinase A and are unmasked by steroids and cyclooxygenase inhibitors. Mol Pharmacol . 2008;73:566–574. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.040519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Schmidt M, Sun G, Stacey MA, Mori L, Mattoli S. Identification of circulating fibrocytes as precursors of bronchial myofibroblasts in asthma. J Immunol . 2003;171:380–389. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.1.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chang Y, Al-Alwan L, Risse PA, Roussel L, Rousseau S, Halayko AJ, et al. Th17 cytokines induce human airway smooth muscle cell migration. J Allergy Clin Immunol . 2011;127:1046–1053.e1041-1042. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Joubert P, Hamid Q. Role of airway smooth muscle in airway remodeling. J Allergy Clin Immunol . 2005;116:713–716. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wu Y, Gunst SJ. Vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) regulates actin polymerization and contraction in airway smooth muscle by a vinculin-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem . 2015;290:11403–11416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.645788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mymrikov EV, Seit-Nebi AS, Gusev NB. Large potentials of small heat shock proteins. Physiol Rev . 2011;91:1123–1159. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00023.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Brophy CM, Lamb S, Graham A. The small heat shock-related protein-20 is an actin-associated protein. J Vasc Surg . 1999;29:326–333. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(99)70385-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Dreiza CM, Brophy CM, Komalavilas P, Furnish EJ, Joshi L, Pallero MA, et al. Transducible heat shock protein 20 (HSP20) phosphopeptide alters cytoskeletal dynamics. FASEB J . 2005;19:261–263. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2911fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Matsushima-Nishiwaki R, Toyoda H, Nagasawa T, Yasuda E, Chiba N, Okuda S, et al. Phosphorylated heat shock protein 20 (HSPB6) regulates transforming growth factor-alpha-induced migration and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. PLoS One . 2016;11:e0151907. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Salter B, Pray C, Radford K, Martin JG, Nair P. Regulation of human airway smooth muscle cell migration and relevance to asthma. Respir Res . 2017;18:156. doi: 10.1186/s12931-017-0640-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Komalavilas P, Penn RB, Flynn CR, Thresher J, Lopes LB, Furnish EJ, et al. The small heat shock-related protein, HSP20, is a camp-dependent protein kinase substrate that is involved in airway smooth muscle relaxation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol . 2008;294:L69–L78. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00235.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Englesbe MJ, Deou J, Bourns BD, Clowes AW, Daum G. Interleukin-1beta inhibits PDGF-BB-induced migration by cooperating with PDGF-BB to induce cyclooxygenase-2 expression in baboon aortic smooth muscle cells. J Vasc Surg . 2004;39:1091–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Nauert JB, Klauck TM, Langeberg LK, Scott JD. Gravin, an autoantigen recognized by serum from myasthenia gravis patients, is a kinase scaffold protein. Curr Biol . 1997;7:52–62. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ng T, Parsons M, Hughes WE, Monypenny J, Zicha D, Gautreau A, et al. Ezrin is a downstream effector of trafficking PKC-integrin complexes involved in the control of cell motility. EMBO J . 2001;20:2723–2741. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.11.2723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Perkins GA, Wang L, Huang LJ, Humphries K, Yao VJ, Martone M, et al. PKA, PKC, and AKAP localization in and around the neuromuscular junction. BMC Neurosci . 2001;2:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-2-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Limaye AJ, Bendzunas GN, Kennedy EJ. Targeted disruption of PKC from AKAP signaling complexes. RSC Chem Biol . 2021;2:1227–1231. doi: 10.1039/d1cb00106j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Dixon RE, Santana LF. A Ca2+- and PKC-driven regulatory network in airway smooth muscle. J Gen Physiol . 2013;141:161–164. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201210953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Schmidt M, Cattani-Cavalieri I, Nunez FJ, Ostrom RS. Phosphodiesterase isoforms and cAMP compartments in the development of new therapies for obstructive pulmonary diseases. Curr Opin Pharmacol . 2020;51:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Gosens R, Stelmack GL, Dueck G, Mutawe MM, Hinton M, McNeill KD, et al. Caveolae facilitate muscarinic receptor-mediated intracellular Ca2+ mobilization and contraction in airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol . 2007;293:L1406–L1418. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00312.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]