Abstract

We report the cyclotrimerization reactions of triynes using Mn(I) complexes derived from MnBr(CO)5 and phosphine ligands, such as 1,1-bis(diphenylphosphino)methane (dppm). These reactions are driven by irradiation under mild conditions (30–80 °C) without the need of additional photoinitiators. Our catalytic screening revealed that counteranions and ligands significantly influence the process. This method accommodates a broad range of functionalities in the substrates, including alkyl, aryl, Bpin, SiMe3, GeEt3, PPh2, pyridyl, and thienyl moieties, without notable interference in the transformation. Additionally, this method enables reactions with oligoalkynes-like (un)substituted hexaynes, producing 2-fold cyclization products in very good yields. Under stoichiometric conditions, the cyclization of diynes with phosphaalkynes results in the unique photochemical synthesis of phosphinines. Experimental and theoretical mechanistic studies indicate that the dissociation of the diphosphine ligand precedes the involvement of the Mn carbonyl species in the catalytic cycle. The ligand plays a crucial role in stabilizing the catalyst during the catalytic transformation and preventing the formation of unreactive cluster species.

Keywords: manganese, [2 + 2 + 2] cycloaddition, oligoalkynes, reaction mechanism, arenes

Introduction

The de novo synthesis of (hetero)aromatic compounds from smaller building blocks has become an attractive target over the last decades, benefiting from the rapid development of synthetic methods in organic syntheses and (bio)catalytic science. In many cases, such transformations require a multistep approach to assemble the aromatic core, and the extension of the aromatic system to a larger carbo- or heterocyclic congener is a common methodology. The toolbox for the one-step construction of (hetero)arenes from simple alkyne building blocks is limited, with the cyclotrimerization reaction of alkynes and heterocumulenes being the prime example.1 Such a reaction requires catalytic facilitation to overcome the intrinsically high activation barrier, which was theoretically described for the formation of benzene from acetylene.2 Transition metal catalysts for the (catalytic) mediation of [2 + 2 + 2] cycloaddition reactions of an increasingly large substrate array comprising alkynes, oligoalkynes, nitriles, and other heterocumulenes have evolved toward maturity for metals from groups 8–10, namely, ruthenium, cobalt, rhodium, iridium, and nickel.3−5 Besides these commonly used transition metals, other metals including, e.g., niobium,6 molybdenum,7 iron,8 or palladium9 have seen less significant evolution or have just been investigated for a limited scope of substrates but reveal interesting novel possibilities for cyclotrimerizations. Especially 3d transition metal catalysis can open new alleys of reactivity, as was showcased recently by the catalytic utilization of iron10 and cobalt11 for the cyclotrimerization of unusual substrates like phosphaalkynes with alkynes, leading to substituted phosphinines. Although metal-free formal cyclotrimerizations have been reported,12 they include alternative pathways or reactions under more drastic conditions to yield the cycloaddition products. Only quite recently, electro- and photochemical methodologies have been disclosed for transition metal-free cyclotrimerization reactions of alkynes and nitriles, regioselectively furnishing substituted pyridines.13

In general, for the middle range of 3d transition metals like iron, manganese, or chromium significantly fewer catalytic procedures for the assembly of alkynes to furnish benzene derivatives are known so far. While iron is the pacemaker among those, chromium has only seen exemplary stoichiometric application, in combination with other metals.14 Iron-catalyzed cyclotrimerization reactions include particular precatalysts such as isolated metalates, in situ generated systems, bimetallic catalysts, and electro- and photochemically driven transformations. Also, CpFe-based catalysts have been reported for successful cyclotrimerization reactions to furnish benzenes and pyridines.15 Concerning the group 7 metals, only manganese and rhenium compounds are catalytically applied in organic synthesis, particularly in C–C and C–H activation reactions.16

Recently reported manganese-catalyzed transformations include hydrogenation, transfer hydrogenation, hydrohetero-functionalization, and cross-coupling reactions as well as radical-mediated reactions, among others.17,18 Very few singular examples appear as formal cyclotrimerization reactions and reveal peculiarities concerning substrates and mechanisms compared to other transition metal complexes.19 One of the earliest examples was reported in a general investigation of transition metal carbonyls for the cyclotrimerization of diphenylacetylene to hexaphenylbenzene under rather drastic conditions using Mn2(CO)10 (Scheme 1, top).20 The Mn(I)-catalyzed cyclization of phenylacetylene (1) and 2,4-pentanedione (2) led to the formation of substituted p-terphenyl product 3 (Scheme 1, middle).21

Scheme 1. Known and Novel Manganese–Carbonyl-Catalyzed Formal Cyclotrimerizations of Alkynes toward Arene and Heteroarene Products.

Such cyclization reactions are also known in very few cases for the rhenium complexes [Re2(CO)10] or [ReBr(CO)3(THF)2], also furnishing substituted arenes from 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds and terminal alkynes. However, the mechanistic rationale for these transformations rather includes formal [2 + 1 + 2 + 1] or [2 + 2 + 1 + 1] cycloaddition steps than the known cyclotrimerization pathways.22 Recently, an approach toward Mn-catalyzed cyclotrimerization using photoredox catalysis was reported, covering the reaction between diynes and acetylenes as a classical substrate combination.23 This methodology required large catalyst loading of a Mn(II) salt such as Mn(acac)2, an additional photoredox catalyst, chlorobenzene as a (partial) solvent, and reaction times up to 12 h. Another formal cyclization of diynes with indoles leading to annulated benzenes was reported via C–H annulation requiring a 2-pyridyl directing group for the sequential alkyne insertion.24

The reactivity of Mn2(CO)10 is in some aspects reminiscent of the reactivity of Co2(CO)8, which has seen increasing application as a cyclotrimerization catalyst in recent years.25 These binary metal carbonyl complexes share significant structural similarities, as they are dinuclear complexes, with two additional CO ligands on the manganese complex to fulfill the formal 18-electron rule. The use of Co2(CO)8 in alkyne chemistry is well documented as it can act beside its catalytic activity as a unique protecting group of the alkyne moiety.26 On the contrary to manganese, the CoX(CO)4 (X = I, Br) compounds are rather unstable and delicate to handle, while congeners such as MnBr(CO)5 are well-known and stable as well as commercially available. The catalytic potential of manganese in comparison to its higher 3d metal congeners iron and cobalt was revealed in recent years, particularly for (de)hydrogenation reactions.27 An interesting connection between transition metal compounds and catalytic activity was proposed in terms of diagonal relationships in the periodic table.28 Here, a connection in the diagonal triad Mn–Ru–Ir was discussed for hydrogenation and transfer hydrogenation reactions, aligning comparable reactivities for Mn(I) as well as Ru(II) complexes. This is particularly interesting since Co(I) and Ru(II) complexes are frequently utilized catalysts in catalytic [2 + 2 + 2] cycloaddition reactions.

In a number of investigations, manganese carbonyls were used directly as catalysts under photochemical conditions, also due to the ease of modification by substitution of the CO groups with other heteroatom ligands. We envisioned the possibility of exploiting this reactivity for cyclotrimerization reactions of triynes and heterocumulenes under photochemical conditions, thus possibly allowing particularly mild conditions and the opportunity to fine-tune the reactivity via additional ligands. We also concentrate on unusual substitution patterns and structures in the alkyne substrates, including functionalization with heteroatom-containing groups. Subsequent cyclization should result in the formation of arenes which are difficult to synthesize and open new venues toward the preparation of functional molecules (Scheme 1, below).

Results and Discussion

In the initial experiments, we used compound 4 as a conventional triyne as the testing substrate to evaluate the general reactivity in cases when the catalyst is not expected to undergo a reaction with the terminal C–H bonds. A thermal blind reaction (microwave, 150 °C, 2 h) under the exclusion of light did not yield any cyclization product. The initial screening reactions were performed at 30 °C under irradiation at 450 nm wavelength for 30 min, to identify any reactivity at this mild temperature, utilizing 10 mol % of manganese, rhenium, or molybdenum catalysts. The results of this screening are displayed in Table 1 for the precatalysts Mn1–5 (entries 1–5), Re (entry 6), and Mo (entry 7). The catalytic activities of these complexes are quite different, with Mn1 and Mn2 being the most active neutral complexes. Except for Mn2(CO)10 (Mn5) all other metal carbonyls provided very small amounts of 5, including the heavy group congener rhenium (Re). Further screening results including reactions in different photochemical reaction setups with Mn1–Mn5 and solvents are compiled in the Supporting Information.

Table 1. Screening of Manganese(I) Precatalysts.

| # | precatalyst | yield 5 [%]a |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | MnBr(CO)5 (Mn1) | 42 |

| 2 | MnCl(CO)5 (Mn2) | 27 |

| 3 | Mn(OTf)(CO)5 (Mn3) | 11 |

| 4 | Cp’Mn(CO)3 (Mn4) | <5 |

| 5 | Mn2(CO)10 (Mn5) (5 mol %) | 20 |

| 6 | ReBr(CO)5 (Re) | <5 |

| 7 | Mo(CO)6 (Mo) | 11 |

Determination of yield by GC-MS with external calibration.

After investigating the general reactivity of the simple manganese–carbonyl complexes, we started our further investigation with the screening of different ligands toward their influence and modification of the catalytic performance of the most suitable manganese(I) precursor Mn1 (Table 2). As constraints, we utilized the same substrate and overall reaction conditions but kept the reaction times short (15 min) to evaluate the productivity of the in situ formed catalyst system. The addition of PPh3 (L1) as a simple monodentate ligand already led to a nearly complete conversion of triyne 4 and a very high yield of 5 (entry 1, Table 2).

Table 2. Screening Results from Reactions with Mn1 and Mono- and Bidentate Ligands.

| # | ligand | yield 5 [%]a |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | triphenylphosphine (L1) | 98 |

| 2 | triphenylphosphite (L2) | 46 |

| 3 | tris(1-naphthyl) phosphine (L3) | 28 |

| 4 | tris(pentafluorophenyl) phosphine (L4) | 18 |

| 5 | triisopropylphosphine (L5) | 51 |

| 6 | 1,1-bis(diphenylphosphino) methane (dppm, L6) | >99 |

| 7 | 1,2-bis(diphenylphosphino) ethane (dppe, L7) | <5 |

| 8 | 1,3-bis(diphenylphosphino) propane (dppp, L8) | <5 |

| 9 | 1,2-bis(diphenylphosphino) benzene (dppbenz, L9) | <5 |

| 10 | no ligand | 24 |

Determination of yield by GC-MS with external calibration.

Application of other phosphines with different steric or electronic properties or triphenylphosphite (L2-L5) led to rather low yields (entries 2–5, Table 2). The application of the chelating ligand 1,1-bis(diphenylphosphino) methane (dppm, L6), however, led to a significant improvement of the yield to >99% (entry 6, Table 2), only comparable to the use of PPh3 (L1, 98%) as a ligand (entry 1, Table 2). Investigation of other chelating ligands (L7–L9) did not lead to improved product formation (entries 7–9, Table 2). The test reaction using only MnBr(CO)5 (Mn1) resulted in 24% product formation after irradiation for 15 min without any additional ligand, clearly demonstrating the beneficial effect of L1 and L6 (entry 10, Table 2). From these experiments, it was concluded that the phosphine ligands L1 and L6 presumably modify the catalyst system toward a higher cyclization rate and longer activity, preventing early deactivation as can be presumed for the ligand-free system only using Mn1 as a precatalyst.

Following evaluation of the optimal catalyst system, we turned our attention to screen the substrate scope for this photocatalytic Mn(I)-diphosphine system (Chart 1). The molecular precatalyst fac-MnBr(CO)3(dppm) (Mn7) was conveniently synthesized from MnBr(CO)5 (Mn1) and dppm (6) and isolated with 91% yield as pure, easy to handle, and for short periods air-stable solid. Cyclization studies using terminally unsubstituted and differently bridged triynes (4, 6–10) yielded the corresponding arene products 5 and 11–15 with different yields at 30 and 80 °C reaction temperatures (Chart 1). The results indicated that ether-bridging is superior to exclusive bridging by malonate (11) or amide (12) tethers. Triynes containing different bridging units while keeping the tether length identical, however, were obtained in moderate yields, corroborating the importance of the nature of the bridging groups. The best result was obtained by an ether-amide bridging to yield the arene 14 with 78% yield after irradiation at 80 °C for 1 h.

Chart 1. Investigation of Triynes Comprising Different Alkyne-Bridging Units.

The substrate scope investigation was therefore extended to functionalized triynes 16–36, based on the overall structure of ether-bridged triyne 4 (Chart 2). We established efficient synthetic pathways for these substrates to provide a large structural variety of different functional groups and useful amounts of cyclization substrates for further elaborations. These results demonstrated the efficiency of the catalytic system for converting even standard triynes to the expected products 37 and 38 with excellent yields at 30 °C. The synthesis of the ortho-diborylated arene 39 with 89% yield is particularly remarkable, as the identical transformation of the terminally diborylated precursor using a CpCo(I) precatalyst under microwave conditions at 200 °C gave only 24% of 39 beside partially or completely deborylated side products.29 The cyclization of a previously unknown and newly synthesized pentayne 19 containing two terminal 1,3-butadiyne units was also successful under these very mild reaction conditions, yielding the 1,2-bisethinylated fully substituted benzene 40 with a 72% yield. The influence of electronically different groups in the para-position of the terminal arene introducing CF3 or OMe substituents was investigated for triynes 20–22. Excellent results were only obtained for CF3 groups as shown for product 41, comparable to compound 38. On the other hand, the unsymmetrically or the symmetrically para-methoxy-functionalized triynes 21 and 22 led under identical reaction conditions to a lower yield of 42 (56%) and 43 (47%). An interesting position of substitution effect has been found in triaryls 44 and 45, where at 30 °C the terminal 2-naphthyl-substituted triyne 24 was converted with an excellent yield to triaryl 44, compared to the significantly lower yield for the conversion of terminal 1-naphthyl-substituted triyne 25. Increasing the reaction temperature to 80 °C, however, led to the cyclization of triyne 25 with up to 91% yield, compared to 41% yield at 30 °C to the triaryl 45, indicating the necessity of higher reaction temperatures with increasing steric demand of the arene. The methodology also allowed the cyclization of 2-thienyl-substituted triyne 25 with an impressive 89% yield at 30 °C, leading to the unknown bisthienyl compound 46. An intriguing synthesis of an ortho-di-2-indenyl substituted arene 47 could also be realized in 92% yield, delivering a potential new ligand blueprint for metallocene synthesis. We further exploited this possibility by synthesizing unsymmetrical, 2-indenyl-substituted triynes 27–29 with additional heteroatom-containing substituents. In this case, the aryl-substituted 2-indenes 48, 49, and 50 could be successfully obtained with yields up to 89% at only 30 °C. Turning our attention also toward further heteroatom-functionalized triynes, the cyclization of triyne substrates 30 and 31 gave the 1,2-bissilylated and 1,2-bisgermylated compounds 51 and 52 with very good yields. Substitution of the triyne backbone with 2-methoxy-1-naphthyl groups led to a 23% yield for triaryl 53 under standard cyclization conditions at 80 °C, while the unreacted 32 was reisolated in pure form. This is another significant advantage of the presented methodology, in which unreacted triyne substrates can often be recovered after the reaction, and no significant side reactions are encountered. However, attachment of phenanthrene or pyrene groups allows the isolation of triaryls 54 and 55 with up to 84% yield. Interestingly, when triyne 35 bearing 2-pyridyl substituents was subjected to cyclization, heterotriaryl 56 was obtained with a nearly quantitative yield. Finally, applying an unsymmetrically substituted triyne containing the sterically rather bulky 2-methoxy-1-naphthyl group, triaryl 57 was still isolated in 52% yield. As a general trend, sterically large terminal aryl substituents require elevated reaction temperature to reach maximum conversion. From the initial studies using an air-cooled photoreactor, we switched to a water-cooled reactor for the entire study, allowing precise temperature control over the entire reaction time. The role of temperature in photocatalytic reactions has been investigated for several photoreactor models for a number of selected reactions and it was found that the temperature can exert a significant influence, either in a negative or positive fashion.30 The overall influence of temperature as a parameter in photocatalytic reactions has only rarely been studied systematically.31 For cobalt-catalyzed cyclotrimerization reactions using gaseous acetylene and nitrile substrates, the temperature dependence of the reaction outcome was causing side product formation (benzene) by influencing the solubility of the acetylene in the reaction solvent.32 In our case, solubility issues with dependence on the reaction temperature have never been observed.

Chart 2. Substrate Screening for the Photocatalytic Mn(I)-Catalyzed [2 + 2 + 2] Cycloaddition Reaction Using a Variety of Functionalized Triynes (Isolated Yields).

Further reactions with selected structurally challenging reaction partners revealed the potential of the Mn-catalyzed transformation (Chart 3). Besides intramolecular cyclizations, we investigated the intermolecular reaction of phenylacetylene as well as benzonitrile with dipropargyl ether as substrates for the synthesis of the corresponding carbo- or heterocyclic products with our catalyst system; however, under the investigated reaction conditions only in the case of the phenylacetylene, the formation of the corresponding 1,3,5- and 1,2,4-triphenylbenzenes in a regiomer ratio of ca. 1:1 with 12% overall product yield was observed.

Chart 3. Showcase of Complex Substrates for Successful Cyclotrimerization Reactions Using Precatalyst Mn7 (Isolated Yields).

We switched to a completely intramolecular reaction using cyanodiyne 58 and found the formation of pyridine 59 with 52% yield at 80 °C. Obviously, the formation of pyridines in principle is possible but ideally requires a completely intramolecular approach under the investigated conditions. For the next example, we developed efficient synthetic approaches toward the hexaynes 60, 62, and 64.33 The subsequent cyclization under optimized reaction conditions led to the formation of the fully substituted biphenyl derivative 61 in 48% yield, while unreacted starting material could simply be reisolated in pure form. The unsubstituted hexayne 62 as well as the phenyl-bridged hexayne 64 were converted to the biphenyl or para-terphenyl derivatives 63 and 65 with excellent 86 and 84% yield. Again, the transformations leave only separable unreacted starting materials behind. The cyclization of the arene-bridged triyne 66 resulted in the formation of the helical structure 67 with 36% yield. These examples illustrate the capabilities of photocatalyzed cyclotrimerizations based on Mn(I)-carbonyl catalysts for rapid transformation of complex substrates at mild temperatures.

We further investigated the reaction of diynes with phosphaalkynes, which was recently reported using 3d transition metal catalysts based on FeII or CoII compounds for the formation of phosphinines.10,11,34 Reactions of phosphaalkynes with low-valent metal complexes often lead to the (undesired) formation of P-ring systems, which strongly coordinate the catalyst and inhibit further reactions.35 Manganese complexes with phosphinines are also reported.36 The reactivity of the C≡N and the C≡P moieties in cycloadditions is quite dependent on the catalyst due to their different electronic properties, with the phosphalkynes having more similarity with a C≡C triple bond than the nitriles.37 We set out to evaluate possible reactivity in the reaction of phosphaalkynes with diynes using higher amounts of the most efficient precatalyst Mn7 under irradiation. To our delight, transformations between diynes and mesitylphosphaalkyne (PA1) or adamantylphosphaalkyne (PA2) applying stoichiometric amounts of Mn7 were found to be successful and delivered the phosphinines 68–71 with yields of up to 42% (Chart 4).

Chart 4. [2 + 2 + 2] Cycloaddition of Diynes and Phosphaalkynes Using Mn7 in Stochiometric Amounts (Isolated Yields).

Dipropargylether as well as dipropargylmalonate worked with PA1 to give products 68 and 69, and also PA2 reacted in a similar yield to product 70. Dipropargylic ether proved to be particularly suitable as already observed for the cobalt catalysis, since homocyclization of the diyne is a neglectable process.38 Interestingly, in the formation of 71a and 71b the more crowded substituted phosphinine 71a is formed in a large excess. This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first photo- and transition metal-mediated phosphinine synthesis under rather mild conditions reported yet.

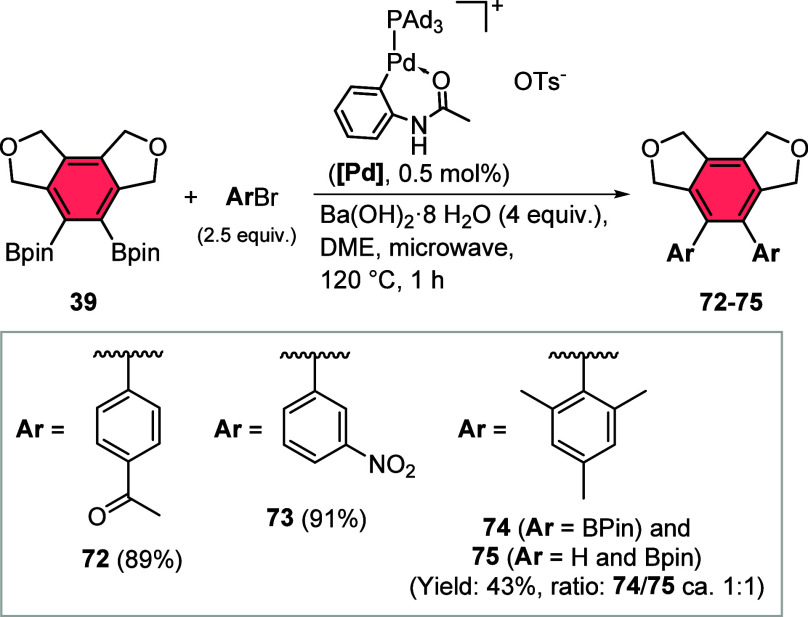

Since our catalyst system allowed the facile preparation of larger amounts of the bisborylated compound 39 it can be regarded as a versatile platform for the introduction of substituents in the 1,2-position for the formation of hexasubstituted benzenes. Naturally, as the most common feature, we evaluated the possibility of further elaboration by Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reaction of 39 under standard conditions using a highly active palladium catalyst and selected functionalized aryl halides as coupling partners (Chart 5). Initial experiments proved the complex [Pd] as a very suitable precursor for rapid reactions under convenient conditions, possessing tri(1-adamantly)phosphine (PAd3) as an electron-rich monodentate ligand.39 Coupling reactions with aryl bromides bearing substituents in the meta- and para-position gave products 72 and 73 with excellent yields of up to 91%. Attempted coupling with sterically demanding 1-bromomesityl also proceeded to the highly substituted desired product 74, however, with this challenging substrate also protodeboronation occurred to yield the monocoupling product 75. Both products were obtained in a roughly 1:1 ratio with a 43% overall yield.

Chart 5. Follow-up Chemistry with Compound 39: Synthesis of Highly Substituted Benzenes by Suzuki–Miyaura Reactions with Aryl Bromides (Isolated Yields).

Discussion of Mechanistic Aspects

Furthermore, we are interested in the reaction mechanism of this unique and unusual photocatalytic cyclotrimerization process, applying manganese(I) complexes. Reaction mechanisms in the field of transition metal-catalyzed [2 + 2 + 2] cycloadditions have been known to follow a general overall pathway with a large variety of mechanistic intricacies, depending on the catalyst metal applied.40 As a common intermediate in most cases regardless of the metal, however, the formation of metallacyclopentadienes from two alkyne moieties was proposed and is now widely accepted based on experimental and theoretical data.41 In the case of manganese, conceivable and isolable manganacyclopentadiene intermediates have not yet been postulated. The (thermal) stoichiometric reaction of 1,6-diynes with MeMn(CO)5 also follows a unique route, as demonstrated by an investigation by Hong and Chung.42 It proceeded via the manganaacetylation of a triple bond and the formation of an isolable compound. This reaction involves the insertion of a carbonyl ligand instead of a metallacyclopentadiene intermediate during the formation of [2,3]-fused cyclopentadiene compounds. Subsequent oxidation with trimethylamine oxide and hydrolysis furnished the [2,3]-annulated cyclopentadienes possessing a tertiary alcohol group. The insertion step is well-known for cobalt complexes possessing CO ligands, exemplified in [2 + 2 + 1]-type cycloaddition reactions of alkynes,43 including photochemical assistance in the exchange of CO groups for alkynes in the initial part of the catalytic cycle.44 A potential intermediate of the cobalt-catalyzed process has been isolated by the group of Vollhardt.45 Detailed studies on organometallic intermediates for the reaction of manganese–carbonyl complexes toward cyclization-type transformations with alkynes are scarce. On the contrary, significant effort is devoted to the photochemistry of manganese–carbonyl complexes containing N-heterocyclic ligands, e.g., for CO2 reduction or CO release.46,47

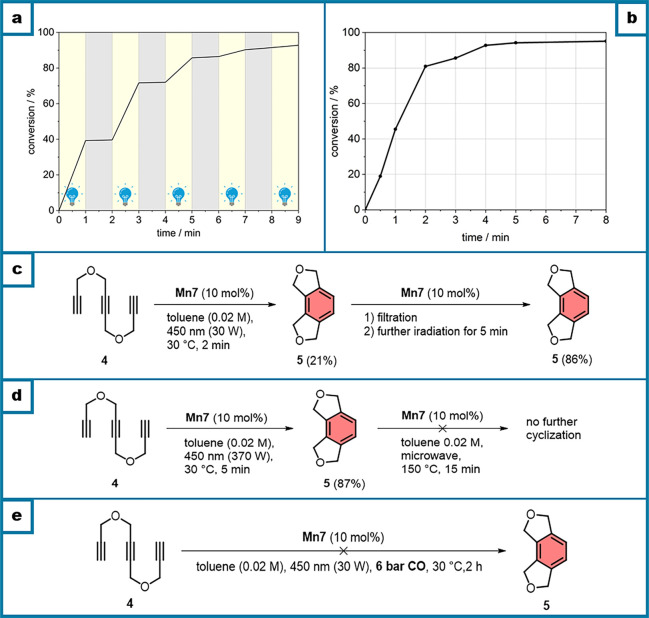

Since mainly cobalt complexes are known for versatile and general photocatalyzed cyclotrimerization reactions without any photoinitiator, we investigated the role of irradiation for the manganese catalysis and performed a light on–off experiment using triyne 4 (Scheme 2a). It clearly showed that the reaction only proceeds under irradiation. We also investigated the conversion–time relationship with triyne 4 and found that the reaction is very rapid, with approximately 80% conversion after 2 min (Scheme 2b). Since we observed the formation of a precipitate after starting the reaction, we made a filtration test by filtering off the formed precipitate and further irradiation of the clear solution, leading to excellent conversion of the triyne 4, allowing us to conclude that the solid formed is not participating in the catalysis (Scheme 2c). For comparison, we also performed the reaction under thermal conditions at 150 °C (microwave), which did not lead to any conversion of triyne 4.

Scheme 2. (a) Light On–Off Experiment Using Mn7 and Triyne 4, (b) Time–Yield Plot for the Cyclization Reaction Triyne 4 Using Mn7, (c) Filtration Test, (d) Control Experiments to Exclude Thermal Background Reactions, and (e) Attempted Cyclization under CO Atmosphere.

This was also observed when performing first a photochemical reaction and then later continuing with thermal heating, where no further reaction was observed (Scheme 2d). Finally, to further elucidate the presence of excess CO for the reaction, we performed the reaction in a CO-pressurized flask and could not find any conversion of the triyne upon irradiation, demonstrating that a large excess of CO successfully inhibited the reaction (Scheme 2e).

For a direct comparison of the performance of the molecularly defined precatalyst Mn7 with the catalyst system obtained from Mn1 in combination with either dppm or PPh3, we applied triyne 21 as the testing substrate. This compound not only demonstrated excellent reactivity in substrate scope evaluations but also offered a straightforward, high-yield synthesis from triyne 4 while providing an additional nucleus for the NMR spectroscopic analysis of potential side products during the cyclization reactions. In these comparative experiments, cyclization product 41 was obtained with 91% yield when applying Mn7, and with 86 or 84% yield when using Mn1 in combination with either the bidentate (dppm, L6) or monodentate (PPh3,L1) ligand in situ. Additional experimentation of the in situ catalyst system was conducted as we hypothesized further CO dissociation from Mn1 under photochemical reaction conditions, and subsequent removal of the gaseous CO from the reaction mixture could potentially favor the deactivation of the catalyst by cluster formation. We tested the addition of an isonitrile as the ligand instead of phosphines with Mn1 for eventual stabilization of the active catalyst. However, the application of 2,6-diisopropylphenyl isonitrile did not show the intended effect, as product 41 was obtained with only 17% yield, indicating deactivation of the catalyst by coordination of the isonitrile (compare compiled results in the Supporting Information).

The 31P NMR investigation of a solution of MnBr(CO)3(dppm) (Mn7) and a 1:1 mixture of Mn1 and bidentate ligand dppp under photochemical conditions already provided clear proof of the different behavior of the species under irradiation. While in the case of Mn7 after 10 min only the free dppm ligand signal was visible at −22 ppm, in the case of MnBr(CO)3(dppp) the complex was formed under photochemical conditions and remained stable (see SI, Figure SI-6 and SI-8). Also, the 1H NMR resonances for precatalyst Mn7 became broader, suggesting that paramagnetic species may have been formed, while the spectrum of the formed complex MnBr(CO)3(dppp) remained unchanged over time (see SI, Figures SI-7 and SI-9). In the case of precatalyst Mn7, the resulting species were catalytically inactive when the triyne substrate was not present at the start of the irradiation but was added later, while the irradiation was continued. This suggests that the precatalyst in the absence of the cyclization substrate is decomposing to one or more new species with higher nuclearity.

Since the observed line broadening in the 1H NMR spectra suggested the formation of paramagnetic species upon irradiation, we conducted in situ EPR measurements of Mn1 and Mn7 and observed the evolution of a broad singlet signal over time (see SI, Figure SI-10). This signal is characteristic of MnII clusters. Most probably, these clusters are part of the catalytically inactive solid residue, the formation of which was observed during the catalytic tests (vide supra). Note that the intact Mn1 and Mn7 species in solution contain a MnI central atom, which is not EPR active. Thus, the formation of MnII clusters by in situ EPR points to the partial decomposition of the initial Mn complexes under reaction conditions. By monitoring the area (double integral) of the EPR signal as a function of time, it was found that the extent of MnII cluster formation depends on the presence of ligands (Scheme 3a). While the fastest cluster formation was observed for MnBr(CO)5 (Mn1), MnBr(CO)3(dppm) (Mn7) was much more stable under the same reaction conditions. Cluster formation could be significantly reduced and even totally suppressed by adding dppm or dppp, respectively, to the solution of Mn1. This points to the stabilizing effect of these ligands. Subsequent addition of the triyne substrate 4 accelerated the decomposition of Mn7 and Mn1 even in the presence of the dppm and dppp ligands (Scheme 3b). These results suggest that cluster formation from Mn1 and Mn7 might be initiated by the formation of vacant coordination sites upon release of CO (also supported by DFT calculations, vide infra) and depends on how fast these sites are filled by ligand or substrate molecules.

Scheme 3. Double Integration of EPR Spectra of a Mixture of (a) Mn1 (1 mM) and Different Ligands (1 mM); and (b) in Addition of Triyne 4 (10 mM).

Interestingly, the partial decomposition of Mn1 in combination with dppm as well as isolated precatalyst Mn7 has only a negligible impact on the catalytic performance as almost the same high yields for the cyclization process were obtained with triyne 4 (Table 2, entry 6 and Chart 1). Obviously, this decomposition comprises only a minor part of the total Mn content in the solution, rendering sufficient intact Mn complex molecules available to drive the catalytic reaction.

The ATR-IR experiments revealed the degradation of Mn7 and Mn1 under irradiation conditions. Both the manganese complexes were decomposed to species with vibrational bands shifted toward lower wavenumbers (see SI, Figures SI-12 and SI-13). However, the decomposition of Mn in the presence of the dppm ligand was confirmed to be slower than without the ligand. In the presence of triyne 4, the concentration profile of the cyclization product showed a steady increase over the entire investigated period, which is interestingly in correlation with the development of the free dppm ligand. Regarding the Mn complex, two species were determined during the irradiation. The first one is the precatalyst Mn7, which was gradually converted to a new manganese species. Compared to the degraded species from Mn7, this new species possesses an additional broad vibrational band in the region between 1970 and 2040 cm–1, which might be due to the coordination of the Mn center and triyne 4.

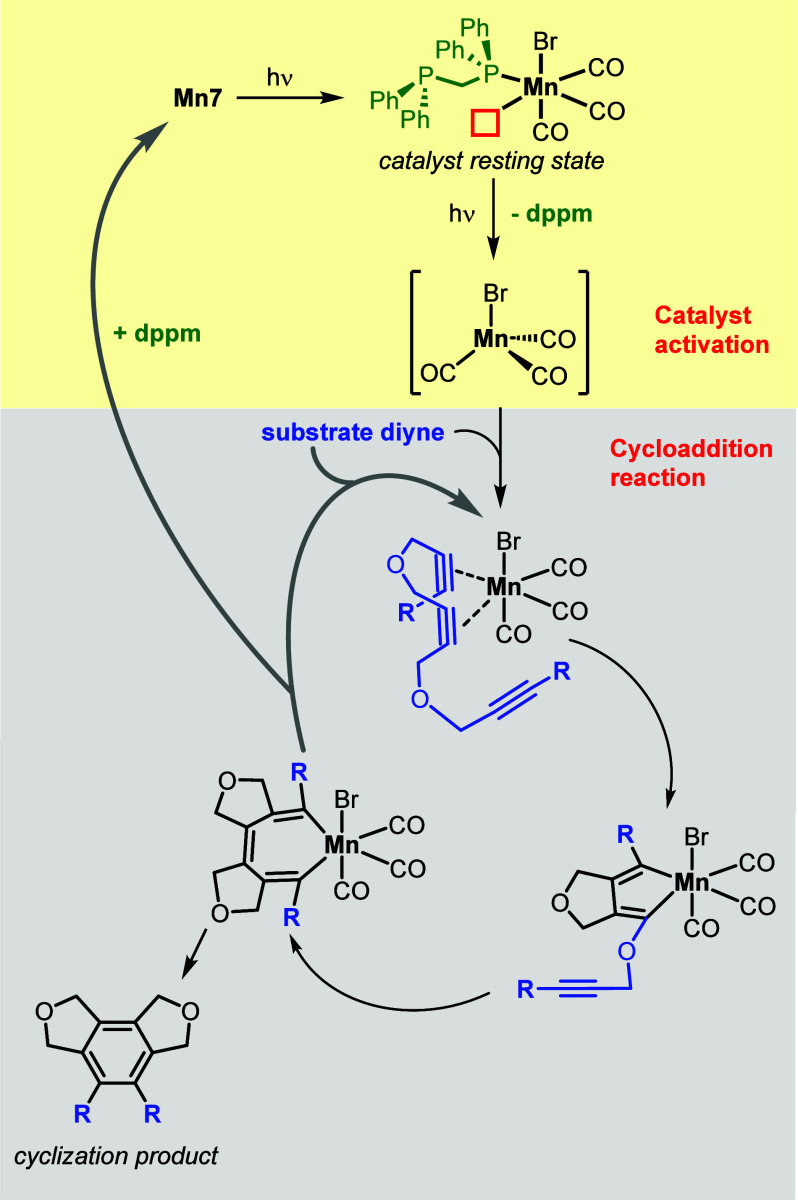

Based on the literature precedent for other [2 + 2 + 2] cycloadditions40 and our own experience, we investigated the potential reaction mechanism by theoretical methods, and the details of computational methods, structures, energies, and stabilities of substrates and precatalysts as well as possible intermediates are given in the Supporting Information. While MnBr(CO)5 (Mn1) is catalyzing the cycloaddition reaction under irradiation, the addition of PPh3 or dppm as the ligand significantly improves the cyclization process, as our experiments have demonstrated. Other ligands specifically acted detrimental or even prevented any cyclization reaction. These studies are therefore directed toward a general understanding of the overall catalytic cycle and similarities and differences to reaction mechanisms of other transition metals as well as the specific understanding of the role of donor ligands in the precatalyst Mn7 for the improvement of performance in the [2 + 2 + 2] cycloaddition.

For the theoretical study, we first evaluated the possible first steps starting from MnBr(CO)5 (Mn1) and found CO ligand dissociation, resulting in the formation of MnBr(CO)3 (A) energetically more favorable over heterolytic and homolytic Br–Mn bond dissociation to form a Mn(CO)5 cation and a radical (Figure SI-14), respectively. Starting from MnBr(CO)3 (A), which has a tetragonal structure with 14 valence electrons in the singlet state, the cyclization sequences of triyne 17 are computed. Starting from both facial and meridional configuration of complex (Mn7), the most preferred route is dppm decoordination and the most favored intermediate is MnBr(CO)3 (A) (Figure SI-16). Therefore, we computed the reaction starting from MnBr(CO)3 (A) and triyne 17. The proposed mechanism is shown in Scheme 4. The coordination of complex A and triyne 17 leading to intermediate B is exergonic by ∼5 kcal/mol, and subsequently overcoming an apparent activation barrier of nearly 15.69 kcal/mol led to the slightly exothermic formation of manganacyclopentadiene C, from which upon presumed insertion of the third triple bond the product E is formed in a highly exothermic reaction via D.

Scheme 4. Presumed Reaction Mechanism for the Manganese-Catalyzed Cyclization of Triyne 17 from Theoretical Calculations.

These results show that complex A, once formed, can react easily with triyne 17 to form the cyclization product via a rather small apparent barrier (10.61 kcal/mol). This agrees with the experimental condition of low temperature and short time. The most energy-demanding step is the decoordination of CO and dppm (38.63 and 36.21 kcal/mol, respectively), and such energy cost reveals why the reaction needs light irradiation and why it is not active only under thermal conditions at 150 °C. To check the influence of bulky substituents on the cyclization, the reaction of the triyne with 1-naphthyl substituents was computed (Chart 2, product 45). However, it was found that the computed Gibbs free energy barrier and the reaction Gibbs free energy from complex B to complex C are close to those of the related compound 38 with phenyl substituent (16.04 vs 15.69 and −7.24 vs −4.52 kcal/mol). In addition, the cyclization energy from the substrate to product 45 is nearly the same as found for product 38 possessing phenyl groups (−110.66 vs −114.24 kcal/mol). All these data corroborate that the substitutes do not significantly affect the reaction kinetics and thermodynamics.

Since the CO ligand decoordinated from MnBr(CO)5 will escape from the system, the coordinatively unsaturated MnBr(CO)3 (A) will either form clusters or react with a different ligand, such as dppm. As found in our control experiments, the cyclization reaction with MnBr(CO)5 (Mn1) results in increased cluster formation and shows no cyclization when the reaction is conducted under a CO pressure with Mn7.

The catalytic cycle in Scheme 5 compiles the experimental and theoretical work toward the mechanism elucidation, exemplified for precatalyst Mn7. The experiments corroborated that the monodentate ligand PPh3 can provide equal coordinative support to the “MnBr(CO)3” fragment as a catalytically active species compared to dppm. The phosphine does not adopt a role as a steering ligand during the catalytic cycle but rather acts as a pure spectator ligand in the back row to provide support in preventing catalyst decomposition and aggregation to catalytically inactive species.48 The cycle represents a photochemically driven activation part, providing the active species and presumably also a thermally driven part for the cyclization to convert the triyne starting material, indicated by improved cyclization results for sterically larger substrates (compare Chart 2 with the results for the formation of triaryl 45 at different temperatures).

Scheme 5. Tentative Catalytic Mechanism of the Manganese-Catalyzed [2 + 2 + 2] Cycloaddition Reaction.

Conclusions

In this investigation, we report on the first use of the manganese(I)–carbonyl complex MnBr(CO)5 as a catalyst for the [2 + 2 + 2] cycloaddition of functionalized triynes under mild photochemical conditions using irradiation at 450 nm wavelength to rapidly furnish the aromatic reaction products without requiring any other additional photo(redox)catalyst. The application of the small bite angle ligand 1,1-bis(diphenylphosphino)methane (dppm) to assemble the precatalyst MnBr(CO)3(dppm) significantly improves the performance and allows the isolation of high product yields within rather short reaction times. Reactions were usually performed at 30 °C, but depending on the substituents in the substrates, an increase of the reaction temperature to 80 °C leads to optimized yields even for larger substituents. The implementation of efficient synthetic pathways for the assembly of oligoalkynes from simple building blocks including the installation of a large variety of functional groups (e.g., substituted aryl, indenyl, Bpin, SiMe3, PPh2, pyridyl, thienyl) allows the assembly of highly substituted benzene derivatives including examples for further derivatization by cross-coupling reactions. The cyclizations can also be performed with hexaynes, leading to the corresponding biphenyl products in a 2-fold cyclization process. The successful performance was exemplarily demonstrated for cyanodiynes, leading to the substituted pyridine core. Application of the catalyst under stoichiometric reactions in the transformation between diynes and phosphaalkyne led to the first photomediated synthesis of phosphinines under rather mild reaction conditions. The reaction mechanism was investigated by spectroscopic and theoretical methods to elucidate the initiation of the catalytically active species and its entry into the catalytic cycle. The applied dppm and PPh3 ligands are only required for the fast generation and the stabilization of the catalytically active “MnBr(CO)3” fragment but are not involved in the catalytic cycle. Further computation confirmed the progression of the catalytic cycle via oxidative cyclization and insertion of the third alkyne moiety toward a manganacycloheptatriene intermediate and final ring closure via reductive elimination, yielding the aromatic product.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank LIKAT for financial support. M.H. thanks the JKU for financial support. This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) I 5385.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscatal.5c00349.

Detailed experimental information on the synthesis of starting materials and products, computational details, and spectral data for all synthesized compounds (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

We have previously shared a preprint of this work on ChemRxiv (Baumann, B.N.; Dam, P.; Rabeah, J.; Kubis, C.; Brückner, A.; Jiao, H.; Hapke, M. Manganese-catalyzed [2 + 2 + 2] Cycloaddition Reactions. ChemRxiv. 2024, DOI: 10.26434/chemrxiv-2024–0rrg8).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Vollhardt K. P. C. Transition-metal-catalyzed acetylene cyclizations in organic synthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 1977, 10, 1–8. 10.1021/ar50109a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cioslowski J.; Liu G.; Moncrieff D. The concerted trimerization of ethyne to benzene revisited. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2000, 316, 536–540. 10.1016/S0009-2614(99)01319-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K.Transition-Metal-Mediated Aromatic Ring Construction; John Wiley & Sons, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hapke M.; Weding N.; Kral K.. Cyclotrimerization Reactions of Alkynes. In Applied Homogeneous Catalysis with Organometallic Compounds, Vol. 1, 3rd ed (Eds.: Cornils B.; Herrmann W. A.; Beller M.; Paciello R.); Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2018; pp 375–410. [Google Scholar]

- a Yamamoto Y. Recent advances in intramolecular alkyne cyclotrimerization and its applications. Curr. Org. Chem. 2005, 9, 503–519. 10.2174/1385272053544399. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Chopade P. R.; Louie J. [2 + 2 + 2] Cycloaddition reactions catalyzed by transition metal complexes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2006, 348, 2307–2327. 10.1002/adsc.200600325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Gandon V.; Aubert C.; Malacria M. Recent progress in cobalt-mediated [2 + 2 + 2] cycloaddition reactions. Chem. Commun. 2006, 2209–2217. 10.1039/b517696b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Agenet N.; Buisine O.; Slowinski F.; Gandon V.; Aubert C.; Malacria M. Cotrimerizations of acetylenic compounds. Org. React. 2007, 68, 1–302. 10.1002/0471264180.or068.01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Tanaka K. Cationic Rhodium(I)/BINAP-Type bisphosphine complexes: versatile new catalysts for highly chemo-, regio-, and enantioselective [2 + 2 + 2] cycloadditions. Synlett 2007, 2007, 1977–1993. 10.1055/s-2007-984541. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Scheuermann C. J.; Ward B. D. Selected recent developments in organo-cobalt chemistry. New J. Chem. 2008, 32, 1850–1880. 10.1039/b802689k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Galan B. R.; Rovis T. Beyond Reppe: Building Substituted Arenes by Cycloadditions of [2 + 2 + 2]-Cycloadditions of Alkynes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 2830–2834. 10.1002/anie.200804651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Tanaka K. Transition-metal-catalyzed enantioselective [2 + 2 + 2] cycloadditions for the synthesis of axially chiral biaryls. Chem. - Asian J. 2009, 4, 508–518. 10.1002/asia.200800378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Domínguez G.; Pérez-Castells J. Recent advances in [2 + 2 + 2] cycloaddition reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 3430–3444. 10.1039/c1cs15029d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Hua R.; Abrenica M. V. A.; Wang P. Cycloaddition of Alkynes: Atom-economic protocols for constructing Six-Membered Cycles. Wang. Curr. Org. Chem. 2011, 15, 712–729. 10.2174/138527211794519023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; k Tanaka K.; Shibata Y. Rhodium-Catalyzed [2 + 2 + 2] cycloaddition of alkynes for the synthesis of substituted benzenes: catalysts, reaction scope, and synthetic applications. Synthesis 2012, 44, 323–350. 10.1055/s-0031-1289665. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; l Ruijter E.; Broere D. Recent Advances in Transition-Metal-Catalyzed [2 + 2 + 2]-Cyclo(co)trimerization Reactions. Synthesis 2012, 44, 2639–2672. 10.1055/s-0032-1316757. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; m Okamoto S.; Sugiyama Y.-K. From the development of catalysts for alkyne and Alkyne-Nitrile [2 + 2 + 2] cycloaddition reactions to their use in polymerization reactions. Synlett 2013, 24, 1044–1060. 10.1055/s-0032-1316913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; n Amatore M.; Aubert C. Recent advances in stereoselective [2 + 2 + 2] cycloadditions. C. Aubert. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 2015, 265–286. 10.1002/ejoc.201403012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; o Thakur A.; Louie J. Advances in Nickel-Catalyzed cycloaddition reactions to construct carbocycles and heterocycles. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 2354–2365. 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; p Domínguez G.; Pérez-Castells J. Alkenes in [2 + 2 + 2] cycloadditions. Chem. - Eur. J. 2016, 22, 6720–6739. 10.1002/chem.201504987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; q Hilt G.; Röse P. Cobalt-Catalysed Bond Formation Reactions; Part 2. Synthesis 2016, 48, 463–492. 10.1055/s-0035-1560378. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; r Kotha S.; Lahiri K.; Sreevani G. Design and Synthesis of Aromatics through [2 + 2 + 2] Cyclotrimerization. Synlett 2018, 29, 2342–2361. 10.1055/s-0037-1609584. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; s Staudaher N. D.; Stolley R. M.; Louie J. [2 + 2 + 2] Cycloadditions of Alkynes with Heterocumulenes and Nitriles. Organic Reactions 2019, 1–202. 10.1002/0471264180.or097.01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; t Ratovelomanana-Vidal V.; Matton P.; Huvelle S.; Haddad M.; Phansavath P. Recent progress in metal-catalyzed [2 + 2 + 2] cycloaddition reactions. Synthesis 2022, 54, 4–32. 10.1055/s-0040-1719831. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Masuda T.; Mouri T.; Higashimura T. Cyclotrimerization of phenylacetylene catalyzed by halides of niobium and tantalum. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1980, 53, 1152–1155. 10.1246/bcsj.53.1152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Du Toit C. J.; Du Plessis J. A. K.; Lachmann G. Siklotrimerisasie van fenielasetileen deur niobium (V) chloried én ondersoek na die reaksieverloop. S. Afr. J. Chem. 1985, 38, 195–198. [Google Scholar]; c Obora Y.; Takeshita K.; Ishii Y. NbCl3-catalyzed [2 + 2 + 2] intermolecular cycloaddition of alkynes and alkenes to 1,3-cyclohexadiene derivatives. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009, 7, 428–431. 10.1039/B820352K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Satoh Y.; Obora Y. Active Low-Valent Niobium Catalysts from NbCl5 and Hydrosilanes for Selective Intermolecular Cycloadditions. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 8569–8573. 10.1021/jo201757w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Matsuura M.; Fujihara T.; Kakeya M.; Sugaya T.; Nagasawa A. Dinuclear niobium(III) and tantalum(III) complexes with thioether and selenoether ligands [{MIIIX2(L)}2(μ-X)2(μ-L)] (M = Nb, Ta; X = Cl, Br; L = R2S, R2Se): Syntheses, structures, and the optimal conditions and the mechanism of the catalysis for regioselective cyclotrimerization of alkynes. J. Organomet. Chem. 2013, 745–746, 288–298. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2013.07.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Satoh Y.; Obora Y. Low-Valent Niobium-Catalyzed intermolecular [2 + 2 + 2] cycloaddition of tert-Butylacetylene and arylnitriles to form 2,3,6-trisubstituted pyridine derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 7771–7776. 10.1021/jo401399y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Simon C.; Amatore M.; Aubert C.; Petit M. Mild Niobium-Catalyzed [2 + 2 + 2] cycloaddition of sila-triynes: easy access to polysubstituted benzosilacyclobutenes. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 844–847. 10.1021/ol503663k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Czeluśniak I.; Kocięcka P.; Szymańska-Buzar T. The effect of the oxidation state of molybdenum complexes on the catalytic transformation of terminal alkynes: Cyclotrimerization vs. polymerization. J. Organomet. Chem. 2012, 716, 70–78. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2012.05.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Kotha S.; Sreevani G. Molybdenum hexacarbonyl: air-stable catalyst for microwave assisted intermolecular [2 + 2 + 2] co-trimerization involving propargyl halides. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015, 56, 5903–5908. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2015.09.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Kotha S.; Sreevani G. [2 + 2 + 2] Cyclotrimerization with Propargyl Halides as Copartners: Formal Total Synthesis of the Antitumor Hsp90 Inhibitor AT13387. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 1850–1855. 10.1021/acsomega.7b01976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Kotha S.; Sreevani G. Diversity-Oriented approach to spirorhodanines via a [2 + 2 + 2] cyclotrimerization. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 5935–5941. 10.1002/ejoc.201800775. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Wang C.; Wan B. Recent advances in the iron-catalyzed cycloaddition reactions. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2012, 57, 2338–2351. 10.1007/s11434-012-5141-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Majumdar K. C.; De N.; Ghosh T.; Roy B. Iron-catalyzed synthesis of heterocycles. Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 4827–4868. 10.1016/j.tet.2014.04.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Bauer I.; Knölker H.-J. Iron catalysis in organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 3170–3387. 10.1021/cr500425u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Wang C.; Wang D.; Xu F.; Pan B.; Wan B. Iron-catalyzed cycloaddition reaction of diynes and cyanamides at room temperature. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 3065–3072. 10.1021/jo400057t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Minakawa M.; Ishikawa T.; Namioka J.; Hirooka S.; Zhou B.; Kawatsura M. Iron-catalyzed [2 + 2 + 2] cycloaddition of trifluoromethyl group substituted unsymmetrical internal alkynes. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 41353–41356. 10.1039/C4RA06973K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Lipschutz M. I.; Chantarojsiri T.; Dong Y.; Tilley T. D. Synthesis, characterization, and alkyne trimerization catalysis of a heteroleptic two-coordinate FeI Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 6366–6372. 10.1021/jacs.5b02504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Brenna D.; Villa M.; Gieshoff T. N.; Fischer F.; Hapke M.; Von Wangelin A. J. Iron-Catalyzed cyclotrimerization of terminal alkynes by dual catalyst activation in the absence of reductants. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 8451–8454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Bhatt D.; Chowdhury H.; Goswami A. Atom-Economic Route to Cyanoarenes and 2,2′-Dicyanobiarenes via Iron-Catalyzed Chemoselective [2 + 2 + 2] Cycloaddition Reactions of Diynes and Tetraynes with Alkynylnitriles. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 3350–3353. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b01217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Xie Y.; Wu C.; Jia C.; Tung C.-H.; Wang W. Iron–cobalt-catalyzed heterotrimerization of alkynes and nitriles to polyfunctionalized pyridines. Org. Chem. Front. 2020, 7, 2196–2201. 10.1039/D0QO00693A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; j Féo M.; Bakas N. J.; Radović A.; Parisot W.; Clisson A.; Chamoreau L.-M.; Haddad M.; Ratovelomanana-Vidal V.; Neidig M. L.; Lefèvre G. Thermally stable Redox noninnocent Bathocuproine-Iron complex for cycloaddition reactions. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 4882–4893. 10.1021/acscatal.3c00353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Overviews on the application of Pd-catalysed cyclizations with arynes:; a Pérez D.; Peña D.; Guitián E. Aryne cycloaddition reactions in the synthesis of large polycyclic aromatic compounds. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 2013, 5981–6013. 10.1002/ejoc.201300470. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Pozo I.; Guitián E.; Pérez D.; Peña D. Synthesis of nanographenes, starphenes, and sterically congested polyarenes by aryne cyclotrimerization. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 2472–2481. 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Gevorgyan V.; Radhakrishnan U.; Takeda A.; Rubina M.; Rubin M.; Yamamoto Y. Palladium-Catalyzed highly chemo- and regioselective formal [2 + 2 + 2] sequential cycloaddition of alkynes: a renaissance of the well known trimerization reaction?. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 2835–2841. 10.1021/jo0100392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Yamamoto Y.; Nagata A.; Nagata H.; Ando Y.; Arikawa Y.; Tatsumi K.; Itoh K. Palladium(0)-Catalyzed Intramolecular [2 + 2 + 2] Alkyne Cyclotrimerizations with Electron-Deficient Diynes and Triynes. Chem. - Eur. J. 2003, 9, 2469–2483. 10.1002/chem.200204540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Zhang Y.; Wu W.; Fu C.; Huang X.; Ma S. Benzene construction via Pd-catalyzed cyclization of 2,7-alkadiynylic carbonates in the presence of alkynes. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 2228–2235. 10.1039/C8SC04681F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Zhang Y.; Fu C.; Huang X.; Ma S. Construction of Benzopolycycles via Pd-Catalyzed Intermolecular Cyclization of 2,7-Alkadiynylic Carbonates with Terminal Propargyl Tertiary Alcohols. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 3523–3527. 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b00746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Whitesides G. M.; Ehmann W. J. Cyclotrimerization of 2-butyne-1,1,1-d3 by triphenyltris(tetrahydrofuran)chromium(III). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968, 90, 804–805. 10.1021/ja01005a053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Nakajima K.; Takata S.; Sakata K.; Nishibayashi Y. Synthesis of Phosphabenzenes by an Iron-Catalyzed [2 + 2 + 2] Cycloaddition Reaction of Diynes with Phosphaalkynes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 7597–7601. 10.1002/anie.201502531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gläsel T.; Jiao H.; Hapke M. Synthesis of Phosphinines from CoII-Catalyzed [2 + 2 + 2] Cycloaddition Reactions. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 13434–13444. 10.1021/acscatal.1c03483. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hapke M Transition metal-free formal [2 + 2 + 2] cycloaddition reactions of alkynes. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 5719–5729. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.10.083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Wang K.; Meng L.-G.; Wang L. Visible-Light-Promoted [2 + 2 + 2] Cyclization of Alkynes with Nitriles to Pyridines Using Pyrylium Salts as Photoredox Catalysts. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 1958–1961. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ghosh M.; Mandal T.; Lepori M.; Barham J. P.; Rehbein J.; Reiser O. Electrochemical Homo- and Crossannulation of Alkynes and Nitriles for the Regio- and Chemoselective Synthesis of 3,6-Diarylpyridines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202411930 10.1002/anie.202411930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T.; Liu Y.; Iesato A.; Chaki S.; Nakajima K.; Kanno K.-I. Formation of linear tetramers of diarylalkynes by the ZR/CR system. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 11928–11929. 10.1021/ja052864w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Fürstner A.; Majima K.; Martín R.; Krause H.; Kattnig E.; Goddard R.; Lehmann C. W. A cheap metal for a “Noble” task: Preparative and mechanistic aspects of cycloisomerization and cycloaddition reactions catalyzed by Low-Valent iron complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 1992–2004. 10.1021/ja0777180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Richard V.; Ipouck M.; Mérel D. S.; Gaillard S.; Whitby R. J.; Witulski B.; Renaud J.-L. Iron(II)-catalysed [2 + 2 + 2] cycloaddition for pyridine ring construction. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 593–595. 10.1039/C3CC47700B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Baumann B. N.; Lange H.; Seeberger F.; Büschelberger P.; Wolf R.; Hapke M. Cobalt and iron metallates as catalysts for cyclization reactions of diynes and triynes: [2 + 2 + 2] Cycloaddition vs. Garratt-Braverman reaction. Mol. Catal. 2023, 550, 113482 10.1016/j.mcat.2023.113482. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Kuninobu Y.; Takai K. Organic reactions catalyzed by rhenium carbonyl complexes. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 1938–1953. 10.1021/cr100241u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kuninobu Y.; Takai K. Development of novel and highly efficient methods to construct Carbon–Carbon bonds using Group 7 Transition-Metal catalysts. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2012, 85, 656–671. 10.1246/bcsj.20120015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Valyaev D. A.; Lavigne G.; Lugan N. Manganese organometallic compounds in homogeneous catalysis: Past, present, and prospects. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2016, 308, 191–235. 10.1016/j.ccr.2015.06.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sortais J.-B.Manganese catalysis in organic synthesis; John Wiley & Sons, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- a Cahiez G.; Duplais C.; Buendia J. Chemistry of Organomanganese(II) compounds. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 1434–1476. 10.1021/cr800341a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Carney J. R.; Dillon Barry. R.; Thomas S. P. Recent advances of manganese catalysis for organic synthesis. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 2016, 3912–3929. 10.1002/ejoc.201600018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Liu W.; Ackermann L. Manganese-Catalyzed C–H activation. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 3743–3752. 10.1021/acscatal.6b00993. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Cano R.; Mackey K.; McGlacken G. P. Recent advances in manganese-catalysed C–H activation: scope and mechanism. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2018, 8, 1251–1266. 10.1039/C7CY02514A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Hu Y.; Zhou B.; Wang C. Inert C–H bond transformations enabled by organometallic manganese catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 816–827. 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Yang X.; Wang C. Manganese-Catalyzed hydrosilylation reactions. Chem. - Asian J. 2018, 13, 2307–2315. 10.1002/asia.201800618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Wang Y.; Wang M.; Li Y.; Liu Q. Homogeneous manganese-catalyzed hydrogenation and dehydrogenation reactions. Chem. 2021, 7, 1180–1223. 10.1016/j.chempr.2020.11.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; h Son J. Sustainable manganese catalysis for late-stage C–H functionalization of bioactive structural motifs. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 17, 1733–1751. 10.3762/bjoc.17.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Ali S.; Rani A.; Khan S. Manganese-catalyzed C H functionalizations driven via weak coordination: Recent developments and perspectives. Tetrahedron Lett. 2022, 97, 153749 10.1016/j.tetlet.2022.153749. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikai N.; Zhang S.-L.; Yamagata K.-I.; Tsuji H.; Nakamura E. Mechanistic study of the Manganese-Catalyzed [2 + 2 + 2] annulation of 1,3-Dicarbonyl compounds and terminal alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 4099–4109. 10.1021/ja809202y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hübel W.; Hoogzand C. Die cyclisierende Trimerisierung von Alkinen mit Hilfe von Metallcarbonyl-Verbindungen. Chem. Ber. 1960, 93, 103–115. 10.1002/cber.19600930118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Kuninobu Y.; Nishi M.; S S. Y.; Takai K. Manganese-Catalyzed Construction of Tetrasubstituted Benzenes from 1,3-Dicarbonyl Compounds and Terminal Acetylenes. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 3009–3011. 10.1021/ol800969h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kawata A.; Kuninobu Y.; Takai K. Rhenium-catalyzed regio- and stereoselective dimerization and cyclotrimerization of terminal alkynes. Chem. Lett. 2009, 38, 836–837. 10.1246/cl.2009.836. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Kuninobu Y.; Iwanaga T.; Nishi M.; Takai K. Rhenium-catalyzed Regioselective Synthesis of Phenol Derivatives from 1,3-Diesters and Terminal Alkynes. Chem. Lett. 2010, 39, 894–895. 10.1246/cl.2010.894. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuninobu Y.; Nishi M.; Kawata A.; Takata H.; Hanatani Y.; Salprima Y. S.; Iwai A.; Takai K. Rhenium- and Manganese-Catalyzed Synthesis of Aromatic Compounds from 1,3-Dicarbonyl Compounds and Alkynes. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 334–341. 10.1021/jo902072q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y.; He Y.; Wang X.; Lu L.; Zhou Z.; Song X.; Tian W.; Xiao Q. Photoredox-Enabled Manganese-Catalyzed [2 + 2 + 2] Cycloaddition of Alkynes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2024, 366, 1545–1550. 10.1002/adsc.202400024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yi X.; Chen K.; Chen W. Manganese-Catalyzed Sequential Annulation between Indoles and 1,6-Diynes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2018, 360, 4497–4501. 10.1002/adsc.201801043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gläsel T.; Hapke M.. Cobalt-catalyzed [2 + 2 + 2] cycloaddition reactions. In The Chemistry of Organocobalt Compounds (Eds.: Gosmini C.; Marek I.; Liebman J. F.; Rappaport Z.. Wiley & Sons, 2024; pp 301–369. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn D. R.; Gawel P.; Xiong Y.; Christensen K. E.; Anderson H. L. Synthesis of polyynes using dicobalt masking groups. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 2077–2086. 10.1021/acs.joc.7b03015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallmeier F.; Kempe R. Manganese Complexes for (De)Hydrogenation catalysis: A Comparison to Cobalt and Iron Catalysts. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 46–60. 10.1002/anie.201709010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashima K. Diagonal Relationship among Organometallic Transition-Metal Complexes. Organometallics 2021, 40, 3497–3505. 10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iannazzo L.; Vollhardt K. P. C.; Malacria M.; Aubert C.; Gandon V. Alkynylboronates and -boramides in CoI- and RhI-Catalyzed [2 + 2 + 2] Cycloadditions: Construction of Oligoaryls through Selective Suzuki Couplings. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 3283–3292. 10.1002/ejoc.201100371. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Svejstrup T. D.; Chatterjee A.; Schekin D.; Wagner T.; Zach J.; Johansson M. J.; Bergonzini G.; König B. Effects of Light Intensity and Reaction Temperature on Photoreactions in Commercial Photoreactors. ChemPhotoChem. 2021, 5, 808–814. 10.1002/cptc.202100059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bloh J. Z. A Holistic Approach to Model the Kinetics of Photocatalytic Reactions. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 128. 10.3389/fchem.2019.00128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller B.; Heller D.; Wagler P.; Oehme G. Control of selectivity in the cobalt(I)-catalysed cocyclisation of alkynes with nitriles. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 1998, 136, 219–233. 10.1016/S1381-1169(98)00058-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser-Hay coupling of propragyl alcohol and ethynyltrimethylsilane resulted in the efficient synthesis of the homo- and heterocoupled products, which were then brominated or directly applied to synthesize pentayne 19 and hexayne 62 by final etherification. See the Supporting Information for details.

- Coles N. T.; Sofie Abels A.; Leitl J.; Wolf R.; Grützmacher H.; Müller C. Phosphinine-based ligands: Recent developments in coordination chemistry and applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 433, 213729 10.1016/j.ccr.2020.213729. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Hitchcock P. B.; Maah M. J.; Nixon J. F. First example of cyclodimerisation of a phospha-alkyne to a 1,3-diphosphacyclobutadiene. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1986, 737–738. 10.1039/C39860000737. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Matos R. M.; Nixon J. F.; Okuda J. Cyclodimerisation and addition reactions of ButC≡P at a cobalt(I) centre. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1994, 222, 13–20. 10.1016/0020-1693(94)03888-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Wolf R.; Schnöckelborg E.-M. A reactive iron napthalene complex provides convenient access to the Cp*Fe– synthon (Cp*=C5Me5). Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 2832–2834. 10.1039/b926986j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Wolf R.; Ehlers A. W.; Khusniyarov M. M.; Hartl F.; De Bruin B.; Long G. J.; Grandjean F.; Schappacher F. M.; Pöttgen R.; Slootweg J. C.; Lutz M.; Spek A. L.; Lammertsma K. Homoleptic Diphosphacyclobutadiene Complexes [M(η4-P2C2R2)2]x– (M = Fe, Co; x = 0, 1). Chem. - Eur. J. 2010, 16, 14322–14334. 10.1002/chem.201001913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Nief F.; Charrier C.; Mathey F.; Simalty M. Reaction des phosphorines avec les cymantrenes. Synthese d’un complexe sandwich η5-cyclopentadienyl-η6-phosphorine-manganese. Organomet. Chem. 1980, 187, 277–285. 10.1016/S0022-328X(00)81796-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Fischer J.; De Cian A.; Nief F. Structure of η5-cyclopentadienyl(η6–2,4,6-triphenylphosphorin)manganese(I). Acta Crystallogr. 1981, B37, 1067–1071. 10.1107/S0567740881005074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Waschbüch K.; Floch P. L.; Ricard L.; Mathey F. 2-Phosphanylphosphinines as bridging ligands for dinuclear transition metal carbonyls. Chem. Ber. 1997, 130, 843–849. 10.1002/cber.19971300706. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Hartl F.; Mahabiersing T.; Floch P. L.; Mathey F.; Ricard L.; Rosa P.; Záliš S. Electronic Properties of 4,4‘,5,5‘-Tetramethyl-2,2‘-biphosphinine (tmbp) in the Redox Series fac-[Mn(Br)(CO)3(tmbp)], [Mn(CO)3(tmbp)]2, and [Mn(CO)3(tmbp)]−: Crystallographic, Spectroelectrochemical, and DFT Computational Study. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 42, 4442–4455. 10.1021/ic0206894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolay A.; Ziegler M. S.; Small D. W.; Grünbauer R.; Scheer M.; Tilley T. D. Isomerism and dynamic behavior of bridging phosphaalkynes bound to a dicopper complex. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 1607–1616. 10.1039/C9SC05835D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- We have repeated the cycloaddition experiment using only the dipropargylic ether and manganese catalyst 7 without the phosphaalkyne. The dimeric cyclization product was obtained as the exclusive product, however, only with 9% yield. See the SI for details.

- Chen L.; Ren P.; Carrow B. P. Tri(1-adamantyl)phosphine: Expanding the Boundary of Electron-Releasing Character Available to Organophosphorus Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 6392–6395. 10.1021/jacs.6b03215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roglans A.; Pla-Quintana A.; Solà M. Mechanistic studies of Transition-Metal-Catalyzed [2 + 2 + 2] cycloaddition reactions. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 1894–1979. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Takahashi T.; Zhou L.; Li S.; Kanno K.-I. Recent development for formation of aromatic compounds via metallacyclopentadienes as metal-containing heterocycles. Heterocycles 2010, 80, 725–738. 10.3987/REV-09-SR(S)6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Li S.; Zhou L.; Kanno K.; Takahashi T. Recent development for enantioselective synthesis of aromatic compounds from alkynes via metallacyclopentadienes. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2011, 48, 517–528. 10.1002/jhet.555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Ma W.; Yu C.; Chen T.; Xu L.; Zhang W.-X.; Xi Z. Metallacyclopentadienes: synthesis, structure and reactivity. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 1160–1192. 10.1039/C6CS00525J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S. H.; Chung Y. K. Synthesis of [2,3]-fused bicyclic cyclopentadiene derivatives by the cycloaddition reaction of diyne with methylmanganese carbonyl complex. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 4843–4846. 10.1016/S0040-4039(98)00917-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Son S. U.; Choi D. S.; Chung Y. K.; Lee S.-G. Dicobalt Octacarbonyl-Catalyzed Tandem [2 + 2 + 1] and [2 + 2 + 2] Cycloaddition Reaction of Diynes with Two Phenylacetylenes under CO. Org. Lett. 2000, 2, 2097–2100. 10.1021/ol000108j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Son S. U.; Yoon Y. A.; Choi D. S.; Park J. K.; Kim B. M.; Chung Y. K. Dicobalt octacarbonyl catalyzed carbonylated cycloaddition of triynes to functionalized tetracycles. Org. Lett. 2001, 3, 1065–1067. 10.1021/ol015635x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomont J. P.; Nguyen S. C.; Zoerb M. C.; Hill A. D.; Schlegel J. P.; Harris C. B. Observation of a Short-Lived triplet precursor in CpCo(CO)-Catalyzed alkyne cyclotrimerization. Organometallics 2012, 31, 3582–3587. 10.1021/om300058y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Diercks R.; Eaton B. E.; Gürtzgen S.; Jalisatgi S.; Matzger A. J.; Radde R. H.; Vollhardt K. P. C. The first Metallacyclopentadiene(Alkyne) complexes and their discrete isomerization to η4-Bound arenes: the missing link in the prevalent mechanism of transition metal catalyzed alkyne cyclotrimerizations, as exemplified by cyclopentadienylcobalt. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 8247–8248. 10.1021/ja981766q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Dosa P. I.; Whitener G. D.; Vollhardt K. P. C.; Bond A. D.; Teat S. J. Cobalt-Mediated Synthesis of angular [4]Phenylene: structural characterization of a Metallacyclopentadiene(Alkyne) intermediate and its thermal and photochemical conversion. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 2075–2078. 10.1021/ol025956o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henke W. C.; Otolski C. J.; Moore W. N. G.; Elles C. G.; Blakemore J. D. Ultrafast spectroscopy of [Mn(CO)3] complexes: tuning the kinetics of light-driven CO release and solvent binding. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 2178–2187. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b02758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reviews on CO2 reduction using manganese-carbonyl complexes:; a Sinopoli A.; La Porte N. T.; Martinez J. F.; Wasielewski M. R.; Sohail M. Manganese carbonyl complexes for CO2 reduction. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 365, 60–74. 10.1016/j.ccr.2018.03.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Stanbury M.; Compain J.-D.; Chardon-Noblat S. Electro- and photoreduction of CO2 driven by manganese-carbonyl molecular catalysts. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 361, 120–137. 10.1016/j.ccr.2018.01.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Grills D. C.; Ertem M. Z.; McKinnon M.; Ngo K. T.; Rochford J. Mechanistic aspects of CO2 reduction catalysis with manganese-based molecular catalysts. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 374, 173–217. 10.1016/j.ccr.2018.05.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Siritanaratkul B.; Eagle C.; Cowan A. J. Manganese carbonyl complexes as selective electrocatalysts for CO2 reduction in water and organic solvents. Acc. Chem. Res. 2022, 55, 955–965. 10.1021/acs.accounts.1c00692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- There are relatively few and systematic reports on the photochemically induced dissociation of phosphines from transition metal complexes and transition metal carbonyl compounds. In most cases the ligand dissociation has been investigated in connection to catalytic and coordination chemistry. Exemplary selected references:; a Kunin A. J.; Eisenberg R. Photochemical carbonylation of benzene by iridium(I) and rhodium(I) square-planar complexes. Organometallics 1988, 7, 2124–2129. 10.1021/om00100a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Goumans T. P. M.; Ehlers A. W.; van Hemert M. C.; Rosa A.; Baerends E.-J.; Lammertsma K. Photodissociation of the Phosphine-Substituted Transition Metal Carbonyl Complexes Cr(CO)5L and Fe(CO)4L: A Theoretical Study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 3558–3567. 10.1021/ja029135q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Batool M.; Martin T. A.; Naser M. A.; George M. W.; Macgregor S. A.; Mahon M. F.; Whittlesey M. K. Comparison of the photochemistry of organometallic N-heterocyclic carbene and phosphine complexes of manganese. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 11225–11227. 10.1039/c1cc14467g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Procacci B.; Duckett S. B.; George M. W.; Hanson-Heine M. W. D.; Horvath R.; Perutz R. N.; Sun X.-Z.; Vuong K. Q.; Welch J. A. Competing Pathways in the Photochemistry of Ru(H)2(CO)(PPh3)3. Organometallics 2018, 37, 855–868. 10.1021/acs.organomet.7b00802. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.