Abstract

Background:

Due to the high prevalence of intrauterine pathologies, postmenopausal women are more eligible for hysteroscopy procedure. Cervical dilatation is always a major challenge for performing hysteroscopy. The present study aimed to determine the efficacy of vaginal Hyoscine N-butylbromide (HBB) on cervical dilatation prior to hysteroscopy in postmenopausal women.

Materials and Methods:

This open-label randomized controlled trial was conducted on postmenopausal women who were scheduled for hysteroscopy. Eligible patients were randomly assigned with a ratio of 1:1 to the intervention (received 20 mg HBB vaginally two hours prior to hysteroscopy) and control (did not receive HBB) groups. As the study outcomes, pre-hysteroscopy cervical dilatation (based on the passage of the dilator number 4 through the cervical canal) and the adverse event consequences were compared between the two groups.

Results:

Overall, 128 postmenopausal women who were eligible for hysteroscopy were included in the study, with 64 individuals in each group. The percentage of cervical dilatation in the intervention group was significantly higher than the control group (100 vs. 70.3%, P<0.001). Furthermore, none of the adverse event consequences differed significantly between the intervention and control groups: bleeding (3.1 vs. 3.1%, P>0.999), nausea and vomiting (4.7 vs. 0%, P=0.244), dry mouth (3.1 vs. 0%, P=0.496), dizziness (0 vs. 0%), and headache (0 vs. 0%).

Conclusion:

Based on the findings, vaginal HBB is effective without any significant side effects in cervical dilation of postmenopausal women (registration number: IRCT20220822055772N1).

Keywords: Cervical Dilatation, Hysteroscopy, Postmenopause, Scopolamine

Introduction

Operative hysteroscopy is the main procedure for treating intrauterine lesions with the lowest risk and invasiveness for the patients (1). The issue of cervical dilatation is a common concern that surgeons encounter during hysteroscopy. This problem is more noticeable in patients without a history of vaginal delivery, menopause, or cervical stenosis. Furthermore, during myomectomy with a hysteroscope, adequate cervical dilatation is required to allow the resectoscope enter the uterine cavity and remove the mass (2). Cervical dilatation is usually achieved mechanically by applying pressure through a mechanical dilator or bogie, which may cause complications. These complications encompass cervical rupture, creation of a false passage by entering through an abnormal route, bleeding, and uterine rupture. Nevertheless, if the cervix is prepared and softened prior to the hysteroscopy, these complications will be minimized (3).

Postmenopausal women have a stenotic cervical canal, which may be due to either congenital or acquired etiologies, such as procedures performed on the cervix, certain medical conditions (e.g., cervical trauma, infections, malignancies, radiation, and mass effects resulted from Nabothian cysts or massive leiomyomas of the cervix), or estrogen deficiency after menopause (4). A stenotic cervical canal due to mucosal atrophy makes hysteroscopy procedures painful. On the other hand, postmenopausal women have a higher risk of developing intrauterine pathologies; hence, they benefit the most from the hysteroscopy procedure. Consequently, these patients need to adopt methods for cervical dilatation, which will reduce their pain during the hysteroscopy (5).

Hyoscine is a pharmaceutical compound that exhibits anticholinergic, antispasmodic, analgesic, and sedative properties by directly affecting the smooth muscles of the digestive and genitourinary systems (6). The sedative properties of hyoscine can also alleviate pain (7), which has already been used for relaxation and analgesia during labor (8). Previous studies have reported that hyoscine could expedite the initial stage of labor, make the uterus dilate, prepare the cervix for hysteroscopy, and induce analgesia (9-12). Systemic administration of hyoscine may be accompanied by adverse effects, including dry mouth, urinary retention, and stomach irritation. These adverse effects can be reduced by vaginal administration of hyoscine, which results in a localized response and a more selective effect on the cervix (13).

Some researchers have recommended hyoscine injection directly to the cervix to achieve cervical dilatation during labor (14, 15) or hysteroscopy procedures (8). A previous study indicated that intravaginal hyoscine could facilitate cervical dilatation in premenopausal women when administered 8 and 2 hours before the hysteroscopy (16). However, studies regarding the efficacy of intravaginal hyoscine on cervical dilatation in postmenopausal women who are scheduled for hysteroscopy are limited. Thus, this study aimed to determine the efficacy of vaginal Hyoscine N-butylbromide (HBB) on cervical dilatation prior to hysteroscopy in postmenopausal women.

Materials and Methods

Study design and setting

This open-label randomized controlled trial with two parallel groups was conducted at Imam Hossein Hospital, Tehran, Iran, between April 2023 and December 2023. The study protocol was approved by the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT20220822055772N1). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (IR. SBMU.MSP. REC.1401.660) on March 11, 2023. The study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. All participants completed written informed consent.

Participants

The inclusion criteria were: postmenopausal women who were eligible for hysteroscopy due to postmenopausal bleeding, endometrial thickness exceeding 5 mm, or endometrial polyps detected during ultrasound examination; and willingness to participate in the study. Also, participants possessing the following characteristics were excluded from the study: having glaucoma, obstructive bowel disease, multiple sclerosis, acute heart failure, respiratory diseases, malignancies, and neoplastic tumors; not having undergone a previous surgical procedure on the cervix; hypersensitivity to hyoscine during the study; and reluctance to continue the study.

Data collection

In this study, data collection was based on the convenience sampling method. According to a study by Hadadian and Fallahian (8) and considering the following assumptions the minimum sample size to achieve acceptable external validity was estimated to be 84: α=5%, study power=80%, P1=56.7%, P2=33.3%, and dropout rate=15%.

N=2(A+B)2 P(1-P)/(P1-P2)2

Initially, eligible women underwent a physical examination to make sure that dilator #4 did not pass through their cervix. They were interviewed by a gynecologic and obstetrics resident to obtain baseline characteristics: age, body mass index (BMI), marital status, and a history of normal vaginal delivery (NVD).

Randomization, allocation, blinding, and intervention

The participants were randomized based on the simple randomization method using a random number table. They were equally assigned to intervention and control groups. All patients were required to fast for 6 hours before undergoing hysteroscopy in the operating room. The procedure was performed after spinal anesthesia, or in a few cases, under general anesthesia at the discretion of the anesthesiologist. Additionally, none of the patients received analgesics before the procedure. Intervention group intravaginally received two tablets of HBB (10 mg, produced by Poursina Pharmaceutical Company, Iran) two hours prior to the hysteroscopy procedure. Control group did not receive HBB prior to the hysteroscopy procedure. In this open-label study, there was no blinding.

Outcomes

As the primary outcome of the trial, women were reexamined a few minutes before the hysteroscopy by a gynecologic and obstetrics resident in terms of cervical dilatation. In this study, the passage of dilator number 4 through the cervix was considered as cervical dilatation. Furthermore, as secondary outcomes, bleeding and adverse event consequences (e.g., nausea and vomiting, dry mouth, headache, and dizziness) were recorded. Finally, two groups were compared in terms of the above outcomes.

Statistical analysis

Data were processed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, IBM, USA) software version 18.0. Variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation or frequency (%). Quantitative variables were compared between groups using independent-samples t test. Categorical variables were compared between groups using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests as indicated. In this study, P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

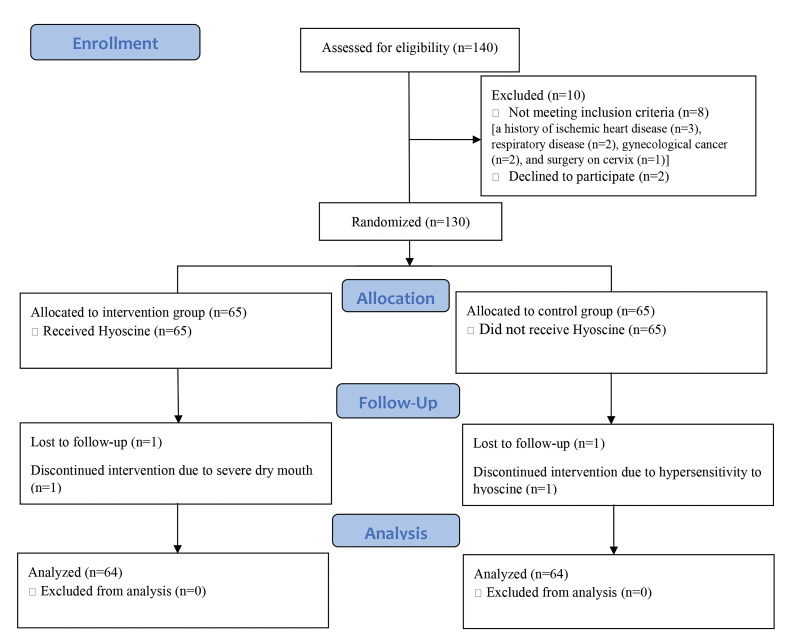

Out of 140 postmenopausal women who were assessed for enrollment, 130 individuals were randomized. They were equally allocated to the intervention and control groups, with 65 individuals in each group. Ultimately, a total of 128 women continued the follow-up period and entered the final analysis. Figure 1 depicts the CONSORT flow diagram of the study.

Fig 1.

CONSORT flow diagram of the study.

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the participants. Their mean age was 51.20 ± 8.17 years (range: 32-77 years). Most of the participants had normal BMI (53.9%), while others were overweight (42.2%) and obese (3.9%). Most of the participants had at least one NVD (71.4%), while others did not experience NVD (28.6%). In addition, the groups did not differ regarding baseline characteristics (P>0.05), except for BMI (P=0.001).

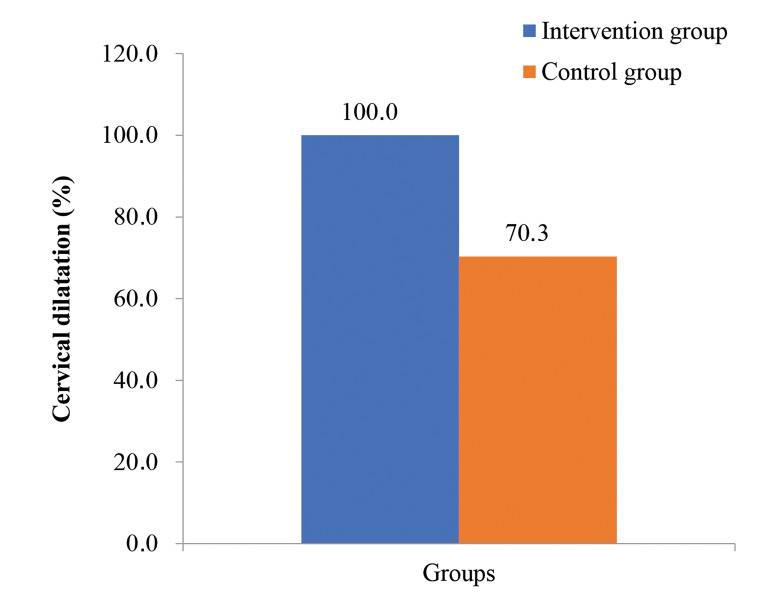

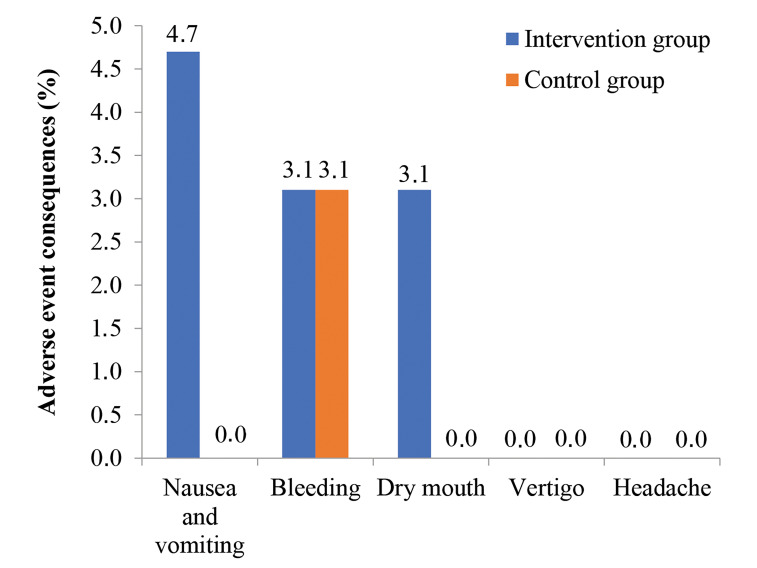

As shown in Figure 2, cervical dilatation percentage before hysteroscopy was significantly higher in the intervention group, who received HBB vaginally, compared with the control group (100 vs. 70.3%, P<0.001). Figure 3 illustrates the adverse event consequences followed by hysteroscopy. None of the participants differed significantly between groups: nausea and vomiting (4.7 vs. 0%, P=0.244), bleeding (3.1 vs. 3.1%, P>0.999), dry mouth (3.1 vs. 3.1%, P=0.496). Furthermore, none of them experienced dizziness and headache.

Fig 2.

Percentage of cervical dilatation in the intervention and control groups.

Fig 3.

Adverse event consequences followed by hysteroscopy.

Table 2 presents the percentage of cervical dilatation based on other variables (age, BMI, and history of NVD). In the intervention group, all women had cervical dilatation (comparison based on other variables was not applicable). However, in the control group, cervical dilatation may be affected by the history of NVD (P<0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the participants

|

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Intervention group (n=64) | Control group (n=64) | Total (n=128) | P value | |

|

| |||||

| Age (Y) | 52.06 ± 8.72 | 50.33 ± 7.55 | 51.20 ± 8.17 | 0.232a | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.001c | ||||

| <25.0 | 44 (68.8) | 25 (39.1) | 69 (53.9) | ||

| 25.0-30.0 | 20 (31.2) | 34 (53.1) | 54 (42.2) | ||

| >30.0 | 0 (0.0) | 5 (7.8) | 5 (3.9) | ||

| Marital status | N/A | ||||

| Married | 64 (100) | 64 (100) | 128 (100) | ||

| Single | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| History of NVD | 0.356b | ||||

| At least one NVD | 51 (35.2) | 37 (22.7) | 88 (28.6) | ||

| No previous NVD | 94 (64.8) | 126 (77.3) | 220 (71.4) | ||

|

| |||||

Values are reported as frequency (%) or mean ± standard deviation. BMI; Body mass index, N/A; Not applicable, NVD; Normal vaginal delivery, a ; Independent-samples t test, b; Chi-square test, c ; Fisher’s exact test

Table 2.

Cervical dilatation based on other variables

|

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Intervention group (n=64) | Control group (n=64) | P value | |

|

| ||||

| Age (Y) | ||||

| <50 | 30/30 (100) | 25/37 (67.6) | 0.001b | |

| ≥50 | 34/34 (100) | 20/27 (74.1) | 0.002b | |

| P value | N/A | 0.574a | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| <25 | 44/44 (100) | 16/25 (64.0) | <0.001b | |

| ≥25 | 20/20 (100) | 29/39 (74.4) | 0.012b | |

| P value | N/A | 0.376a | ||

| History of normal vaginal delivery | ||||

| Yes | 34/34 (100) | 39/41 (95.1) | 0.498b | |

| No | 30/30 (100) | 6/23 (26.1) | <0.001b | |

| P value | N/A | <0.001a | ||

|

| ||||

Values are reported as frequency (%). BMI; Body mass index, N/A; Not applicable, a; Chisquare test, and b; Fisher’s exact test.

Discussion

The present study was conducted to investigate the efficacy of vaginal HBB on cervical dilatation in postmenopausal women who were scheduled for hysteroscopy procedure. Our findings revealed that the administration of HBB vaginally prior to the hysteroscopy contributed to cervical dilatation. Additionally, the intervention group who received HBB had a similar rate of adverse event consequences compared with the control group. Thus, postmenopausal women eligible for hysteroscopy procedure can benefit from vaginal HBB as an effective intervention in cervical dilatation, with minimal adverse effects.

Cervical dilatation is a great challenge for labor and intrauterine procedures like hysteroscopy. Several factors, including proinflammatory cytokines, prostaglandins, relaxin, and ovarian steroids, are involved in cervical dilatation process (17). Conversely, inhibitory impulses via smooth muscle spasms often impair cervical dilatation (8). Cervical dilatation is the main issue determining the duration of hysteroscopy, which can be influenced by mechanical, pharmacological, and non-pharmacological factors. Medicinal agents are prostaglandins, oxytocin, sedatives, and smooth muscle relaxants. Antispasmodic drugs like HBB, drotaverine hydrochloride, phloroglucinol, and valethamate bromide can also facilitate cervical dilatation. HBB or scopolamine is an anticholinergic and antimuscarinic drug with spasmolytic effects on the smooth muscles of the female genital tract, especially through inhibiting the cervicouterine plexus. Hence, scopolamine has the ability to effectively induce cervical dilatation (14, 18).

In a study conducted by Hadadian et al. (8), the efficacy of vaginal hyoscine on cervical dilatation and consistency prior to performing hysteroscopy was compared with placebo. The results of the aforementioned study indicated that hyoscine administration could facilitate cervical dilatation in premenopausal women. However, it did not have much effect on cervical dilatation in postmenopausal women, which is inconsistent with our findings. This discrepancy can be attributed to the small sample size of Hadadian et al.’s (8) study, which makes it difficult to generalize their findings.

In another study, Hadadianpour et al. (16) examined the efficacy of HBB injections (locally in the cervical ostium 10 minutes before gynecological procedures) on the dilatation of stenotic cervixes. Based on their findings, cervical width increased in 57.5% of the participants, as assessed by the passage of dilator number 2 through the cervical canal. Also, the rate of cervical dilatation did not differ significantly between the intervention and control groups considering their ages. These findings are in complete agreement with our results. The only difference between the two studies was the method of HBB administration. The difficulties of HBB injection prompted us to investigate the effect of vaginal hyoscine tablets. Due to the rich blood supply of the cervix, vaginal administration of HBB can cause enhanced absorption, resulting in a greater effect on cervical dilatation (16). Another study by Gokmen Karasu et al. (10) showed rectally-inserted HBB reduced the need for pain medication compared to placebo and misoprostol on patients undergoing hysteroscopy. In our study, age did not interfere with the impact of HBB on cervical dilatation because all the included women were postmenopausal. The structure of cervical tissue is different in postmenopausal women than in premenopausal ones, especially in terms of collagen fibers. After menopause, all the samples had experienced age-related alterations in the cervical tissue structure. Hence, in our target population (postmenopausal women), the age difference did not have a confounding effect on the cervical dilatation (19).

Consistent with our findings, a study by Coimbra et al. (20) reported that the history of NVD was associated with the ease of cervical dilatation. This phenomenon might be attributed to increased pain tolerance and altered tissue structure of the cervix and pelvic floor muscles following mechanical pressure during vaginal delivery (21).

Furthermore, there are some underlying diseases which can play the role of confounding variables in cervical dilatation. Diabetes mellitus is associated with vasculopathy, which might interfere with cervical dilatation by impairing the dynamics of blood vessels of the cervix (22). Additionally, most women with breast cancer have a history of radiotherapy or tamoxifen administration, which causes severe vaginal dryness. The vaginal dryness reduces the absorption of HBB, thereby reducing its efficacy on cervical dilatation (23).

Based on the findings, a few samples had bleeding or drug-related adverse event consequences, the incidence of which did not differ between the intervention and control groups. Hyoscine is an anticholinergic drug that can cause dry mouth, constipation, palpitations, blurred vision, and flushing. However, most of them are mild and recover without any further intervention (24).

Our study had several limitations. Due to the financial restrictions, the control group did not receive a placebo. Conducting a double-blind controlled trial with a placebo-treated control group could provide more reliable results. In our study, cervical dilatation was assessed only using dilator number 4. It is suggested cervical dilatation be assessed using bogies of different sized dilators in future studies. It is also suggested to compare the duration of cervical dilatation with repeated examinations between the intervention and control groups to determine the efficacy of hyoscine with greater dimensions and precision.

Conclusion

The administration of vaginal HBB before the hysteroscopy procedure can facilitate cervical dilatation. Moreover, adverse event consequences following HBB administration were uncommon and almost equal to the control group. Thus, vaginal HBB is an effective intervention with few side effects in cervical dilatation in postmenopausal women who are candidiates for hysteroscopy procedure.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the Preventative Gynecology Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. They also appreciate the patients who kindly participated in the study. The authors declared that they had no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contributions

M.S.H.; Conceptualization, Supervision, and Revised manuscript critically for important intellectual content. F.F.; Supervision, Data acquisition, and Revised it critically for important intellectual content. H.N.; Methodology, Validation, and Writing-review and editing. S.B.; Conceptualization, Data acquisition, Statistical analysis, and Writing-review and editing. All authors have critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Romanski PA, Bortoletto P, Pfeifer SM. A framework approach for hysteroscopic uterine septum incision: partial and complete. Fertil Steril. 2022;118(1):205–206. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2022.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mirgaloybayat S, Madadian M, Tahermanesh K, Derakhshan R, Sarhadi S, Rokhgireh S. Comparative study of the effects of sublingual trinitroglycerin and sublingual misoprostol on cervical preparation before hysteroscopy: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2024;51(7):167–167. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hota T, Abuzeid O, Raju R, Holmes J, Hebert J, Abuzeid M. Management of false passage complication during operative hysteroscopy. Middle East Fertil Soc J. 2022;27(1):11–11. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vitale SG, De Angelis MC, Della Corte L, Saponara S, Carugno J, Laganà AS, et al. Uterine cervical stenosis: from classification to advances in management.Overcoming the obstacles to access the uterine cavity. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2024;309(3):755–764. doi: 10.1007/s00404-023-07126-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samy A, Nabil H, Abdelhakim AM, Mahy ME, Abdel-Latif AA, Metwally AA. Pain management during diagnostic office hysteroscopy in postmenopausal women: a randomized study. Climacteric. 2020;23(4):397–403. doi: 10.1080/13697137.2020.1742685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heshmatnia F, Jafari M, Karimi M, Azizi M, Sayadi M, Yadollahi P. Efficacy of hyoscine butylbromide and promethazine on the labor's active phase duration: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Research in Applied and Basic Medical Sciences. 2024;10(2):130–145. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papadopoulos G, Bourdoumis A, Kachrilas S, Bach C, Buchholz N, Masood J. Hyoscine N-butylbromide (Buscopan®) in the treatment of acute ureteral colic: what is the evidence? Urol Int. 2014;92(3):253–257. doi: 10.1159/000358015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hadadian S, Fallahian M. Assessing the efficacy of vaginal hyoscine butyl bromide on cervical ripening prior to intrauterine procedures: a double-blinded clinical trial. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2016;14(11):709–712. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riemma G, La Verde M, Schiattarella A, Cobellis L, De Franciscis P, Colacurci N, et al. Efficacy of hyoscine butyl-bromide in shortening the active phase of labor: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;252:218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gokmen Karasu AF, Aydin S, Ates S, Takmaz T, Comba C. Administration of rectal cytotec versus rectal buscopan before hysteroscopy. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2022;31(1):94–98. doi: 10.1080/13645706.2020.1748059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehranmehr N, Heidar Z, Hashemi E. The effect of injectable hyoscine and vaginal misoprostol on cervical preparation before hysteroscopy. J Pharm Negat Results. 2022;13(3):1304–1309. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rashwan ASSA, Alalfy M, Elkomaty SA, Helal OM, Hussein EA. Diclofenac potassium alone versus diclofenac potassium with hyoscine-n-butyl bromide (HBB) in reduction of pain in women undergoing office hysteroscopy: a double blind randomized, placebocontrolled trial. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2022;72(Suppl 1):340–345. doi: 10.1007/s13224-022-01648-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qahtani NH, Hajeri FA. The effect of hyoscine butylbromide in shortening the first stage of labor: A double blind, randomized, controlled, clinical trial. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2011;7:495–500. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S16415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohaghegh Z, Abedi P, Faal S, Jahanfar S, Surdock A, Sharifipour F, et al. The effect of hyoscine n- butylbromide on labor progress: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):291–291. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-2832-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirim S, Asicioglu O, Yenigul N, Aydogan B, Bahat N, Bayrak M. Effect of intravenous hyoscine-N-butyl bromide on active phase of labor progress: a randomized double blind placebo controlled trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28(9):1038–1042. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2014.942628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hadadianpour S, Tavana S, Tavana A, Fallahian M. Immediate dilation of a tight or stenotic cervix by intra-procedural administration of hyoscine butylbromide: a clinical trial. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2019;17(4):253–260. doi: 10.18502/ijrm.v17i4.4550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Timmons B, Akins M, Mahendroo M. Cervical remodeling during pregnancy and parturition. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21(6):353–361. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wood MA, Kerrigan KL, Burns MK, Glenn TL, Ludwin A, Christianson MS, et al. Overcoming the challenging cervix: identification and techniques to access the uterine cavity. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2018;73(11):641–649. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0000000000000614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurt I, Kulhan M, AlAshqar A, Borahay MA. Uterine collagen crosslinking: biology, role in disorders, and therapeutic implications. Reprod Sci. 2024;31(3):645–660. doi: 10.1007/s43032-023-01386-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coimbra AC, Falcão V, Pinto P, Cavaco-Gomes J, Fernandes AS, Martinho M. Predictive factors of tolerance in office hysteroscopy - a 3-year analysis from a tertiary center. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2023;45(1):38–42. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-1764361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toozs-Hobson P, Balmforth J, Cardozo L, Khullar V, Athanasiou S. The effect of mode of delivery on pelvic floor functional anatomy. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(3):407–416. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0455-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhamidipati T, Kumar M, Verma SS, Mohanty SK, Kacar S, Reese D, et al. Epigenetic basis of diabetic vasculopathy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022;13:989844–989844. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.989844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kiely BE, Liang R, Jang C, Magraith K. Safety of vaginal oestrogens for genitourinary symptoms in women with breast cancer. Aust J Gen Pract. 2024;53(5):305–310. doi: 10.31128/AJGP-02-23-6709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiappini S, Mosca A, Miuli A, Semeraro FM, Mancusi G, Santovito MC, et al. Misuse of anticholinergic medications: a systematic review. Biomedicines. 2022;10(2):355–355. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10020355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]