Abstract

Reduced histone acetylation in the brain causes transcriptional dysregulation and cognitive impairment that are key initial steps in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) etiology. Unfortunately, current treatment strategies primarily focus on histone deacetylase inhibition (HDACi) that causes detrimental side effects due to non-specific acetylation. Here, we test Tip60 histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activation as a therapeutic strategy for selectively restoring cognition-associated histone acetylation depleted in AD by developing compounds that enhance Tip60’s neuroprotective HAT function. Several compounds show high Tip60-binding affinity predictions in silico, enhanced Tip60 HAT action in vitro, and restore Tip60 knockdown mediated functional deficits in Drosophila in vivo. Furthermore, compounds prevent neuronal deficits and lethality in an AD-associated amyloid precursor protein neurodegenerative Drosophila model and remarkably, restore expression of repressed neuroplasticity genes in the AD brain, underscoring compound specificity and therapeutic effectiveness. Our results highlight Tip60 HAT activators as a promising therapeutic neuroepigenetic modulator strategy for AD treatment.

Subject terms: Alzheimer's disease, Virtual screening, Drosophila, Phenotypic screening

In this work, authors test Tip60 HAT activation as a therapeutic strategy for selectively restoring cognition-associated histone acetylation depleted in AD by developing compounds that bind to and enhance Tip60’s neuroprotective HAT function.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia and imposes a huge public health burden, yet disease-modifying treatments remain elusive. Although genetic abnormalities have been the center of AD research, >90% AD cases are sporadic, implicating a causal role for neuroepigenetic abnormalities. The severity of AD progression is dependent upon the complex interplay between genetics, age, and environmental factors orchestrated in large part, by neuroepigenetic histone acetylation-mediated gene regulatory mechanisms1. Histone acetylation homeostasis in the brain is maintained by the antagonizing activities of histone acetyltransferase (HAT) and histone deacetyltransferase (HDAC) enzymes that generate and erase cognition-linked histone acetylation marks, respectively2,3. Accordingly, decreased histone acetylation resulting from reduced HAT and/or increased HDAC activity causes chromatin packaging alterations in neurons with concomitant transcriptional dysregulation, ultimately resulting in the debilitating cognitive deficits that adversely affect AD patients3–8. As such, small molecular compounds designed to increase histone acetylation levels in the brain are a research hotspot for the development of cognitive-enhancing drugs for AD9–11. Unfortunately, many current pharmacological treatments are primarily centered on histone deacetylase inhibitors that while promising in reversing AD cognitive impairment, have limited translational potential due to detrimental side effects caused by non-specific global hyperacetylation and inhibition of required HDACs for cognition12. Alternatively, histone acetylation homeostasis can be selectively restored by activation of specific HATs, many of which display unique functions in writing the site-specific histone acetylation marks required for promoting neuronal gene expression9,13,14. Thus, although HDAC inhibition has been widely studied for promoting histone acetylation in the neurodegenerative brain, HAT activation serves as a promising therapeutic strategy that remains to be fully explored.

To this end, our laboratory has identified a neuroprotective role for Tat interactive protein 60 kDa (Tip60) HAT domain in AD. Tip60 HAT plays a non-redundant neural function in “writing” distinct global neuroepigenetic acetylation signatures at cognition-linked gene loci required for modulating their expression15–17. Reduced Tip60 protein levels are found in the brains of human postmortem AD hippocampus and in a well-characterized AD-associated amyloid precursor protein (APP) neurodegenerative Drosophila model causing decreased Tip60 mediated acetylation at cognition-associated histone marks with concomitant repression of critical neuroplasticity genes18. Importantly, genetically increasing Tip60 in the Drosophila AD brain acts to prevent such global histone hypoacetylation to specifically activate repressed neuroplasticity genes18,19. Increasing Tip60 levels is also sufficient to prevent against multiple neural processes impaired in early stages of AD that include axonal outgrowth/transport, learning/memory, circadian rhythm, synaptic plasticity, locomotor function, apoptotic-driven neurodegeneration, and neuroplasticity gene control17,18,20–26. Together, these studies support an overall neuroprotective role for Tip60 in multiple neural cognitive circuits impaired in AD and provide a strong foundation for Tip60 activation as a promising therapeutic strategy for AD.

In this work, we test the hypothesis that pharmacological selective enhancement of Tip60’s histone acetylation activity will promote neuroprotective function in AD. We carried out two ligand-based virtual screening approaches utilizing either a lead HAT activator CTB substructure or a pharmacophore-based method27 to identify compounds that share structural or functional similarities to CTB, respectively. Thirteen compounds with top Tip60 docking scores and favorable predicted drug-like properties and blood–brain barrier penetration were selected and custom synthesized. The compounds were then tested for functional efficacy and specificity to Tip60 in an in vitro histone acetylation assay and for ability to restore neuronal functional deficits in vivo in both Tip60 knockdown Drosophila and a well-characterized AD-associated amyloid precursor protein (APP) neurodegenerative Drosophila model. We propose the small-molecule Tip60 HAT activators developed here will serve as effective chemical entities for specific histone acetylation-based cognition-enhancing drugs for AD.

Results

CTB and CTPB are predicted to bind with Tip60’s HAT domain

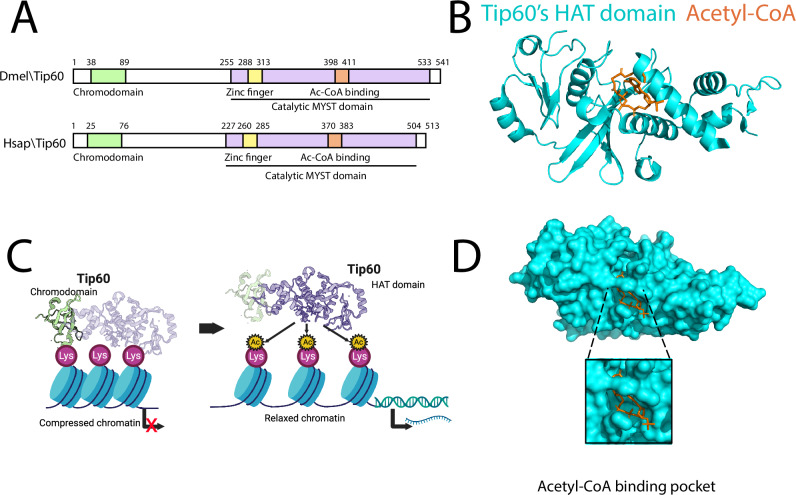

CTB and CTPB are trifluoromethyl phenyl benzamides and activate p300 acetyltransferase11. To determine if these p300 HAT activators also interact with Tip60’s HAT domain, we used an in silico GOLD protein–ligand docking algorithm28. Tip60 contains two domains: an N-terminal chromodomain that recognizes methylated lysine residues on histone proteins and recruits Tip60 to target gene loci and a C-terminal catalytic MYST HAT domain that transfers the acetyl group from Acetyl-CoA to histone proteins for acetylation (Fig. 1A, B). The 3D crystal structure of Tip60’s HAT domain (isoform 3) in complex with Acetyl coenzyme A in X-ray diffraction with resolution of 2.30 Å was obtained from Protein Data Bank (PDB:2ou2). The Acetyl-CoA binding site in the acetyltransferase domain of Tip60 was identified by filtering for residues within 10 Å (Fig. 1C, D). Upon docking, both CTB and CTPB were predicted to interact with Tip60’s HAT domain with a favorable docking score of 52 and 59, respectively (Fig. 2A). Despite its slightly lower docking score, CTB displayed favorable characteristics over CTPB, including its smaller size (343 vs. 554 Dalton) and lack of insoluble long hydrophobic side chain, along with trifluorides (–CF3), all critical for blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability29,30, making CTB the favorable lead for Tip60-activator drug design.

Fig. 1. Tip60 promotes neural gene expression via histone acetylation function.

A Structural similarity between Drosophila Tip60 (Uniprot: Q960X4) and human Tip60 (Uniprot: Q92993) proteins with two major protein domains: N-terminal chromodomain and C-terminal catalytic MYST HAT domain. B Tip60’s histone acetylation mechanism. The chromodomain recognizes methylated lysine residues on histone proteins for Tip60 recruitment to target genes. The catalytic MYST HAT domain acetylates histone, which then relaxes the chromatin allowing for gene expression. (Created in BioRender. Bhatnagar, A. (2025). https://BioRender.com/v41y997). C 3D Modeled structure of Tip60’s catalytic HAT domain (PDB:2ou2) represented as cyan-colored ribbons with acetyl-CoA represented as orange licorice sticks. D Acetyl-CoA binding pocket is present inside the Tip60’s catalytic HAT domain represented in the surface model. Dmel Drosophila melanogaster, Hsap Homosapian, MYST human MOZ, yeast YbF2, yeast Sas2, mammalian Tip60, Tip60 Tat-interacting protein 60 kDa, Acetyl-CoA acetyl-Coenzyme A, HAT histone acetyltransferase.

Fig. 2. CTB and CTPB as potential leads for Tip60 activation drug discovery.

A In silico GOLD protein–ligand docking software was used to dock CTB and CTPB ligands on Tip60’s HAT domain (PDB:2ou2). Predicted chemical interactions, acceptors and donor as well as arene-H bonding are represented using Molecular Operating Environment (MOE). The ligand chemical structures are centered within interacting amino acids of Tip60’s HAT domain that are either polar (purple) or greasy (green). B CTB physically binds with Tip60 protein in vitro. Surface plasma resonance binding plot shows fraction of sites occupied (Y axis) and compound concentration (M, X axis) for CTB (black), CTPB (blue) and WM8014 (red). The concentration of Tip60 on the surface was estimated using [Tip60] = response (captured RU)/100* MW. To plot the % bound isotherm as a function of concentration, it is assumed that binding is 1:1 and the following equation is used: %A bound to B is 100AB/Bt = [Kd+At+Bt - SQRT((Kd+At+Bt)2 − 4*At*Bt)]/(2*Bt) where A = C and B=Tip60. The compounds were theoretically fitted using previously published KD value for WM8014, a known Tip60 inhibitor32. Each compound was injected in duplicate at concentrations ranging from 0.21 to 50 μM (n = 2) and error bars represent SD. C, D CTB (C) and CTPB (D) partially prevent Tip60 knockdown mediated locomotor defects in vivo. Dose-dependent response of CTB and CTPB oral drug administration from 10 to 100 μM or vehicle (DMSO). Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001. Whiskers indicate minimum and maximum. For all whisker blox plots, center line represents the median. Bounds of box indicate 25th to 75th percentile. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Precise n and P values for each experiment are included in Supplementary Data Table 7. CTB N-(4-Chloro-3-triflouromethyl-phenyl)−2-ethoxy-benzamide, CTPB N-(4-Chloro-3-triflouromethykl-phenyl)−2-ethoxy-6-pentadecyl-benzamide, Veh Vehicle, WT wild-type, DMSO dimethylsulfoxide.

CTB directly binds and activates Tip60’s HAT function

We next validated if CTB and CTPB directly bind with the Tip60 protein to exert functional effects. We used surface plasma resonance (SPR)31, an optical detection technique used to study label-free biomolecular interactions between a ligand (Tip60 protein) and analytes (candidate compounds dissolved in DMSO) in real time (Fig. 2B). CTB, CTPB, and WM8014 (a known Tip60 inhibitor for a positive control) were sequentially passed through a GST-Tip60 antibody captured biosensor chip in increasing drug concentrations and changes in intensity of reflected light was measured as calculated as % bound sites. The SPR results were corrected for non-specific binding on reference surface and DMSO calibration to account for direct Tip60-compound complexes on the experimental chip (Supplementary Table 1). The binding affinity of CTB and CTPB were ranked relative to the previously published KD values for WM8014-Tip60 binding32. All three compounds showed direct binding with Tip60 protein. CTB showed slightly higher binding affinity (KD = 28.6 ± 3.5 μM) than CTPB (KD = 67.4 ± 6.0 μM) and known Tip60 inhibitor WM8014 (KD = 54.9 ± 3.2 μM), where KD is the dissociation constant. These results support the favorability of CTB as the lead compound for Tip60 activation drug design.

We next tested if these compounds exert functional effects on Tip60 in vivo. Drosophila is a robust effective model to functionally test the efficacy of pharmacological drugs and has been widely used for drug screening in various neurological disorders33–35. Using the Gal4-UAS targeted gene expression system36, the expression of UAS-Tip60 RNAi in all neurons can be modulated using the pan-neuronal elav-Gal4 driver line. The resulting progeny with elav-Gal4;UAS-Tip60-RNAi genotype is referred to as the Tip60-RNAi knockdown model. The elav-Gal4 driver line alone serves as the wild-type control in these experiments. We first confirmed that Tip60 mRNA levels are significantly reduced in the Tip60-RNAi model as compared to wild-type using RT-qPCR (Supplementary Fig. 1A). In addition, in line with our previous work20, we found Tip60 knockdown resulted in reduced larval locomotion as compared to wildtype (Fig. 2C, D), enabling us to use this model to test the functional efficacy of compounds to rescue the neuronal locomotion phenotype caused by Tip60 reduction. Larvae were reared on food either with compounds (CTB, CTPB) or without compounds (DMSO vehicle) using standard published protocol20 and a functional locomotion assay was used to assess improvement in locomotion defects caused by Tip60 reduction (Fig. 2C, D). Treatment of larvae with either CTB and CTPB showed significant rescue for locomotor ability with CTB showing more robust therapeutic effects than CTPB (Fig. 2C, D). In summary, the direct binding of CTB to Tip60 and activation of its HAT activity in vitro along with prevention of Tip60 knockdown associated locomotor function in vivo further validated the choice of CTB as a lead compound suitable for Tip60-activator drug design.

Substructure-based virtual screening of Tip60 modulators

CTB was used in a substructure search to identify analogs with better specificity for Tip60. Importantly, since fluorides are essential for BBB permeability29 and the relative positioning of trifluorides (–CF3) with the chloride (-Cl) in CTB are essential for HAT activation11, we ensured retention of these halogens in our Tip60-specific HAT activator design. A ligand substructure-based virtual screening approach using the commercially available ZINC15 chemical database was performed37 (Fig. 3A). Structures of the top 100 compound hits were then docked to Tip60’s HAT domain using the GOLD protein–ligand docking algorithm38. Each protein-compound interaction was scored using GOLD total docking score that is a summation of individual scores obtained via ligand atom contributions and their interaction types. These 100 compounds ranged in docking scores from 43 to 68, with higher score correlating with favorable protein–ligand binding energy. Of note, CTB ranked 57th in the best docking scores, suggesting more than half of our identified compounds were predicted to have better Tip60 binding than CTB. Based on the GOLD docking scores, the top 10 compounds (designated as C1–C10) were successfully synthesized for further analysis (Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 3. Substructure-based virtual screening pipeline and in vivo testing for Tip60 HAT activators.

A CTB was used as a query ligand to screen compounds with a similar substructure in curated ZINC15 compound library. Top 100 compounds with similar structure as CTB were then individually docked on Tip60’s HAT domain (PDB:2ou2) using GOLD protein–ligand docking software. Top 15 compounds with the best docking scores were selected and 10 out of these 15 compounds were synthesized for further testing, now referred to as C1–C10. (Created in BioRender. Bhatnagar, A. (2025) https://BioRender.com/v38v616). (B–K) In vivo locomotion testing of C1–C10 compounds using Drosophila Tip60 knockdown model under elavC155 pan-neuronal Gal4 driver to assess compound efficacy on locomotion speed. Locomotion results are for Tip60-RNAi knockdown larvae fed with vehicle only or different indicated compound concentrations prepared in vehicle, revealing high-performing compounds (B–D), low-performing compounds (E–J) and non-performing compound (K). Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. For all box and whisker plots, center line represents the median. Bounds of box indicate 25th to 75th percentile. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Precise n and P values for each experiment are included in Supplementary Data Table 7. Tip60 Tat-interacting protein 60 kDa, CTB N-(4-Chloro-3-triflouromethyl-phenyl)−2-ethoxy-benzamide, Veh vehicle, WT wild-type.

In vivo testing of substructure-based Tip60 modulators

The 10 compounds (C1–C10) were next tested in an in vivo Drosophila larval locomotor assay to assess their functional effectiveness in rescuing locomotor defects induced by Tip60-RNAi knockdown20. Out of the 10 compounds, C2, C5, and C8 were the highest performers and rescued locomotor deficits at lower drug concentrations as compared to CTB (Fig. 3B–D). Compounds C1, C3, C6, C7, C9, and C10 were the low-performing compounds (Fig. 3E–J) since they performed either similar to CTB or slightly better in rescuing locomotor defects. Unlike the other compounds, C4 had no effect in this assay possibly due to its insolubility or inability to target and/or activate Tip60 (Fig. 3K). Together, these results show that several substructure-based compounds for Tip60 HAT activation fully rescue locomotor deficits in Tip60- RNAi-knockdown larvae.

Pharmacophore-based virtual screening of Tip60 modulators

To design molecules that were not restricted to the CTB core structure, the pharmacophore-based virtual screening method was used to design additional Tip60 HAT activators39,40. In the first pharmacophore search (PP1), all CTB pharmacophore features (Fig. 4) were retained, except only one of the aromatic rings was included, resulting in ~5800 hits. In the second pharmacophore search (PP2), all CTB pharmacophore features were retained except only one of the aromatic rings was included and only one feature out of aromatic ring F1, hydrogen acceptor F4 or hydrophobic site F6 was included, resulting in 13,147 hits. Combining these two screens, a total of ~19,000 hits were obtained that were then docked to Tip60’s HAT domain using GOLD docking software. Using a filter cutoff of Gold docking score of 78 or higher, 38 compounds were identified that were triaged based on high docking score, ease of synthesis and similarity in core structure. Among these 38, 13 compounds (designated as P1–P13), with docking scores ranging from 78 to 81 were chosen for further testing (Supplementary Table 3).

Fig. 4. Pharmacophore-based virtual screening pipeline for Tip60 HAT activators.

A Synthesis of compounds. CTB was used as a query ligand to screen compounds with a similar pharmacophoric model in the curated ZINC15 compound library. Top ~19,000 compounds with similar pharmacophore as CTB were then individually docked on Tip60’s HAT domain (PDB:2ou2) using GOLD protein–ligand docking software. Using a filter for Gold docking score >78, top 38 compounds with best docking scores were selected and 13 of these compounds were custom synthesized for further testing, now referred to as P1–P13. (Created in BioRender. Bhatnagar, A. (2025) https://BioRender.com/t67v064). B Pharmacophore modeling on CTB ligand. Using the Molecular Operating Environment (MOE), six pharmacophore features for CTB (gray licorice sticks) were screened as follows: F1 aromatic ring (orange); F2 aromatic ring (orange); F3 hydrogen donor (magenta); F4 hydrogen acceptor (cyan); F5 hydrophobic (green), and F6 hydrophobic (green). Different combinations of these pharmacophore features were used for virtual screening on ZINC15 compound library. Tip60 Tat-interacting protein 60 kDa, CTB N-(4-Chloro-3-triflouromethyl-phenyl)−2-ethoxy-benzamide, Hyd hydrophobic, Aro aromatic, Don donor, Acc acceptor.

HAT activity assay to identify Tip60-activator compounds

The 13 hits from the pharmacophore-based screen were tested for activation or inhibition of Tip60’s HAT activity using an in vitro histone acetylation assay. This assay screening identified 4 compounds (P1-P4) that reduced Tip60’s HAT activity with P3 demonstrating a similar level of Tip60 HAT inhibitory activity as the known inhibitor WM8014 (Fig. 5A–C). Remarkably, 5 out of the 13 compounds (P6, P9, P10, P11, and P13) enhanced Tip60’s HAT activity with P6, P10 and P13 compounds displaying the highest level of Tip60 HAT activation (Fig. 6A, C, D). To test compound specificity, we repeated the in vitro HAT assay this time using purified p300 HAT and found that as predicted by our computational design, the P compounds did not promote p300 activity, with P10 and P13 showing the highest specificity for Tip60 over p300 (Fig. 6B, C). In addition, we observed that the P compounds had better specificity and efficacy to Tip60 HAT compared to the previously identified compound CTB. Thus, several pharmacophore-based candidate compounds for Tip60 modulation show direct targeting to Tip60 HAT that either enhances or reduces its HAT activity in vitro.

Fig. 5. Tip60 HAT inhibitors identified via in vitro histone acetylation assay.

A Histone acetylation assay shows Tip60 mediated Histone H4 acetylation in the presence of vehicle (DMSO, red), WM8014 (known Tip60 inhibitor, yellow) or pharmacophore-based P4, P3, P2, and P1 compounds (green) at 20 μM concentration. Background (blue) contains all reaction mixture, however, Histone H4 peptide is added after stopping the reaction to account for background fluorescence. Y axis represents arbitrary fluorescence units (AFU) acquired on a spectrophotometer. Histogram represents n = 2 biological replicates. B Calculation of specific enzyme activity (pmol/min/μg) and percent decrease in Tip60’s HAT activity for different treatments. C Compound structures where m (molecule) and number (docking score) are indicated. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. DMSO dimethylsulfoxide, Tip60 Tat-interacting protein 60 kDa.

Fig. 6. Tip60 HAT activators identified via in vitro histone acetylation assay.

A, B Histone acetylation assay shows Tip60 (A) or p300 (B) mediated Histone H4 acetylation in the presence of vehicle (DMSO, red), CTB (p300 HAT activator, orange) or pharmacophore-based P6, P9, P10, and P11, P13 compounds (green) at 20 μM concentration. Background (blue) contains all reaction mixture, except for Histone H4 peptide which is added after stopping the reaction to account for background fluorescence. Y axis represents arbitrary fluorescence units (AFU) acquired on a spectrophotometer. Histogram represents n = 2 biological replicates. C Calculation of specific enzyme activity (pmol/min/μg) and percent increase in Tip60 or p300’s HAT activity for different treatments. D Compound structures where m (molecule) and number (docking score) are indicated. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. CTB N-(4-Chloro-3-triflouromethyl-phenyl)−2-ethoxy-benzamide, HAT histone acetyltransferase, DMSO dimethylsulfoxide, Tip60 Tat-interacting protein 60 kDa.

In vivo testing of pharmacophore-based Tip60 modulators

The best Tip60 HAT activators (P6, P10, and P13) were tested in the Drosophila larval locomotor assay to assess their functional efficacy in rescuing Tip60-RNAi knockdown-mediated locomotor defects20. Larvae were reared on food either with compounds dissolved in DMSO or vehicle (DMSO) only and functional locomotion assays were performed on third-instar larvae. Both P10 and P13 compounds rescued Tip60 knockdown-induced locomotion deficits in a dose-dependent manner with P10 significantly improving the performance at a low dose of 10 nM and P13 from 1 μM and above (Fig. 7A–C). P6 compound, while effective at 10 nM, did not have consistent dose-dependent effects in the assay. This may be due to P6 not getting absorbed readily into some larvae, and/or insolubility of the drug in the food at high concentrations. Further, the compounds were tested for sustained performance of the larvae to complete crossing the plate and their ability to reach the wall (Fig. 7D–F). Consistent with locomotion assay results, P13 improved the sustained performance of larvae in reaching the wall compared to wild-type controls at a 1 μM drug concentration. To rule out off-target Tip60-RNAi effects, we used a second Tip60-RNAi fly line (Tip60-RNAi-2) harboring a different Tip60 mRNA target sequence that displays a more severe locomotion phenotype to validate the effects of the compounds. Results from this behavioral assay showed compounds C2, P10, and P13 rescued locomotor deficits in these larvae (Supplementary Fig. 2), validating the specificity of these compounds towards Tip60 and the robustness of the assay.

Fig. 7. Oral administration of pharmacophore-based compounds prevent Tip60 knockdown-mediated locomotion deficits in vivo.

A–F In vivo locomotion testing of C1–C10 compounds using Drosophila Tip60 knockdown model under elavC155 pan-neuronal Gal4 driver to assess compound efficacy on locomotion ability to cross 0.5-cm grid lines in 30 s. Locomotion results are for Tip60-RNAi knockdown larvae fed with vehicle only or different indicated concentrations of high-performing P compounds identified in in vitro HAT assay for compounds P6 (A), P10 (B), and P13 (C). Compound efficacy for third-instar larvae ability to cross entire plate for P6 (D) P10 (E), and P13 (F). Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. For all box and whisker plots, center line represents the median. Bounds of box indicate 25th to 75th percentile. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Precise n and p values for each experiment are included in Supplementary Data Table 7. Tip60 Tat-interacting protein 60 kDa, Veh vehicle, WT wild-type.

Efficacy of P compounds in AD-associated APP Drosophila

Early pre-clinical and late AD neurodegenerative stages in humans are conserved both epigenetically and pathologically in a well-characterized and widely used Drosophila AD-associated amyloid precursor protein (APP) model that inducibly expresses full-length human APP pan-neuronally18,22. The brains of third-instar APP larvae that model early-stage AD neurodegeneration display reduced Tip60 protein levels and deficits in cognitive ability, synaptic plasticity, axonal transport and outgrowth, and apoptotic neuronal cell death in the brain17,20,24. AD larval brains also exhibit robust genome-wide early alterations that include reduced Tip60 protein levels and chromatin binding at critical neuroplasticity genes that trigger transcriptional dysregulation18,19. Such alterations are accompanied by locomotion impairment caused by these neuronal defects. The brains of 7-day-old adult flies that model late stages of AD are characterized by reduced Tip60 protein levels, Aβ plaques in the brain, cognitive deficits, and lethality18,19. Such characteristics make APP Drosophila a powerful AD model to test the functional effectiveness of therapeutic drugs in both early and late stages of AD neurodegenerative progression, in vivo.

We sought to test the therapeutic potential of the top four compounds (C2, P6, P10, P13) in protecting against the severe functional locomotion deficits that AD-associated APP Drosophila third-instar larvae display. Larvae were reared on food either with compounds dissolved in DMSO or vehicle (DMSO), and the locomotion assay was performed. All four compounds significantly rescued larval locomotor ability in a dose-dependent manner starting from 1 μM onwards for the P compounds and at 50 and 100 μM for the C2 compound (Fig. 8A–D). Further, the compounds also provided sustained effects in the larvae to complete the assay and to reach the wall (Fig. 8E–H).

Fig. 8. Oral administration of P10 and P13 compounds prevent locomotion deficits and neuroplasticity gene repression in an AD-associated Drosophila APP model.

Locomotion assay measuring compound efficacy for speed of third-instar larvae expressing human APP under elavC155 pan-neuronal Gal4 driver for compounds C2 (A), P6 (B), and P10 (C) and P13 (D). Compound efficacy for third-instar APP larvae ability to cross entire plate for compounds C2 (E) P6 (F), P10 (G) and P13 (H). Statistical significance calculated using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. For all box and whisker plots, center line represents the median. Bounds of box indicate 25th to 75th percentile. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Precise n and P values for each experiment are included in Supplementary Data Table 7. I Real-time qPCR using primer sets that amplify confirmed Tip60 neuroplasticity direct target genes (shaker, futsch, dsh, dlg) was performed using brain tissue dissected from third-instar larvae expressing human APP under elav155 pan-neuronal GAL4 driver. Larvea were grown on food containing either vehicle, or compounds P10 or P13. Histogram represents the fold change in gene expression relative to elav control flies. Statistical significance was calculated using two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons. (n = 40 brains per replicate; 3 replicates). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. Error bars indicate SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Tip60 Tat-interacting protein 60 kDa, WT wild-type, APP amyloid precursor protein, Veh vehicle, RPL32 ribosomal protein L32, DLG Disc-large 1, DSH disheveled.

Transcriptional dysregulation of neuroplasticity genes in the brain is a key step in AD etiology4,6. We previously demonstrated that critical Drosophila homologs of major mammalian cognition genes that are direct targets of Tip60 (shaker, futsch, dlg, dsh) are repressed in the AD-associated APP neurodegenerative Drosophila brain and restored by genetically increasing Tip60 levels18. Since HAT activity is a key mechanism by which Tip60 exerts its transcriptional action, we asked if P compounds could also reactivate inappropriately repressed neuroplasticity genes in the APP larval brain. To test this, APP larvae were reared on food containing the most effective drug concentrations for P10 or P13 and brains were dissected for neural gene expression analysis for shaker, futsch, dlg, dsh (Fig. 8I). We found that P13 and P10 both significantly activated the synaptic bouton regulator gene futsch, and the potassium ion channel gene shaker, and caused a trending increase for neuroplasticity scaffolding gene dlg18,41. P13 also significantly activated Wnt signaling pathway gene disheveled (dsh) that is causatively associated with AD when disrupted41 (Fig. 8I). Expression of Tip60 (Fig. 8I) and APP (Supplementary Fig. 1B) remained unchanged in response to both compounds, verifying that the therapeutic action of these compounds was not limited to affecting Drosophila Tip60 or APP expression levels. Together, these results underscore the therapeutic and transcriptional mechanistic potential of the pharmacophore-based compounds P10 and P13 in preventing AD-associated deficits.

P compounds rescue lethality in AD-associated APP Drosophila

Since both P10 and P13 compounds significantly improved neurodegenerative phenotypes in early stages of AD, we next assessed their effectiveness over long-term adult survival. APP neurodegeneration results in a significantly reduced lifespan with median survival of 23 days for APP flies versus 39 days for elav control flies42, reminiscent of the reduced life expectancy in AD patients. To assess compounds effect on early APP lethality, a pupation/eclosion assay was performed where larvae were reared on food with or without the most effective P10 or P13 compound concentrations, and the number of flies that pupated and then eclosed from their pupal cases over a 10-day period was assessed. We found that both compounds significantly rescued early pupal lethality and improved eclosion rates with P13 exhibiting more robust effects (Fig. 9A, B, D, E). Next, the effect of P10 and P13 on long-term adult survival was assessed. To determine if compounds were most effective at early or late stages of AD-associated APP neurodegeneration, the most effective compound concentrations for P10 and P13 were added to food beginning at either embryogenesis (Day 0), adult Day 3 prior to Aβ brain plaque formation or adult Day 7 post-Aβ brain plaque formation19. Flies were changed into fresh vials containing fresh drug every 4 days over 40 days and lethality on each day was recorded. Results from this study showed that both P10 and P13 compounds significantly extended APP fly lifespan when compared to elav control flies (Fig. 9C, F and Supplementary Fig. 3A–F). Both compounds showed the most robust effects when fed to APP flies beginning at Day 7 in which median survival was restored to healthy control levels (40 days for both P10 and P13 versus 39 days for control) and Day 3 (37 days for P10; 33 days for P13) in contrast to Day 0 (31 days for P10; 30 days for P13) (Fig. 9C, F). These results suggest that compounds are most effective at promoting longevity when administered at later stages of disease progression when Tip60 levels are most reduced and require reactivation to promote histone acetylation homeostasis. In summary, oral administration of pharmacophore-based Tip60 activators P10 and P13 showed consistent and robust prevention of lethality in AD-associated APP flies as well as promoted their longevity, highlighting their therapeutic potential for AD treatment.

Fig. 9. Oral administration of P10 and P13 compounds promotes longevity in an AD-associated Drosophila APP neurodegenerative model.

Compound efficacy on the percent of APP larvae that pupate over a 7-day period for compounds P10 (A) and P13 (D). Minimum of 30 pupae per vial per condition; 3 biological replicates. Compound efficacy on the percent of adult APP flies that eclose over a 7-day period for compounds P10 (B) and P13 (E). Statistical significance was calculated using two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. Whiskers indicate minimum and maximum. For all box and whisker plots, center line represents the median. Bounds of box indicate 25th to 75th percentile. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Precise n and p values for each experiment are included in Supplementary Data Table 7. C, F Longevity graph depicting probability of survival for the five treatment groups over a 40-day period. n = 3 biological replicates. For all experiments, statistical significance was calculated using Logrank (Mantel–Cox) Test and Gehan–Breslow–Wilcoxon two-sided test with no adjustments for multiple comparisons. ****P < 0.0001. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. APP amyloid precursor protein, Veh vehicle, WT wild-type, DMSO dimethylsulfoxide.

Discussion

Specific HATs have emerged as regulators with unique functions that grant access to genes essential for neuroplasticity and higher-order brain function8. Unlike many HDACs that have overlapping functions, specific HATs serve as unique causative agents for memory-impairing histone acetylation reduction in the AD brain, and hence, promising targets for cognitive-enhancing pharmacological strategies10,15. One likely candidate is Tip60, a HAT we have previously shown to have neuroprotective function in AD18–20. Unfortunately, HAT activation therapies have been limited by the difficulty of designing small-molecule modulators that can activate, and not inhibit, enzyme activity9,15. Here, we develop compounds that enhance Tip60’s HAT activity with the potential to serve as a promising therapeutic strategy for AD. To design these compounds, we utilized virtual screening, which is a standard tool in modern drug discovery that utilizes computational methods for screening huge and diverse compound libraries to identify those structures most likely to bind to a desired target40,43,44. Broadly, virtual screening can be performed via ligand-based or structure-based methods that utilizes knowledge of a ligand known to bind to the desired target or the 3D structure of the target protein, respectively43. Here, since we identified CTB as a suitable lead for Tip60-activator drug design, we carried out ligand-based virtual screening utilizing two different approaches for the identification of optimized lead compounds with increased Tip60 specificity. First, we performed CTB substructure-based virtual screening to identify compounds that retain CTB’s core substructure with additional favorable functional groups that might improve binding affinity towards Tip60. However, we found that the top 10 compounds (C1–C10) with the highest docking scores on Tip60’s HAT domain only slightly increased docking predictions from a score of 52 for CTB to 58–68 for these compounds, suggesting only a minimal improvement in Tip60-specific targeting, although some C compounds did rescue Tip60 knockdown neuronal locomotion defects, in vivo. To overcome this low Tip60-specificity issue, we utilized a second approach that involves CTB pharmacophore-based virtual screening to identify compounds that retain CTB’s functional characteristics without necessarily retaining the core substructure. Since this approach broadens our compound search filters to allow for structural modifications without the restricted substructure with halogens, these modulators are expected to be uniquely specific towards Tip60 with the caveat that not all identified compounds would be HAT activators. Indeed, we found that the top 13 compounds (P1–P13) with highest docking scores on Tip60’s HAT domain showed marked increase in docking predictions from a score of 52 for CTB to 78–81 for these P compounds, suggesting these compounds have better specificity to Tip60. However, upon testing them in our in vitro histone acetylation assay, we found that these modulators contained a mixture of Tip60 HAT activators as well as inhibitors. After filtering out the inhibitors, we were able to identify compounds that show strong predicted binding affinity towards Tip60 enzyme in silico and can specifically activate Tip60’s HAT function in a HAT assay in vitro. Together, these results show that several compounds designed via substructure-based and pharmacophore-based virtual screening are potent Tip60 HAT activators with high Tip60 specificity and efficacy as observed in in vitro and in vivo assays.

Small molecules designed to increase histone acetylation are currently a research hotspot for the development of cognitive-enhancing drugs for several neurodegenerative diseases, including AD and focus primarily on inhibition of HDACs5. Accordingly, several HDAC inhibitors (HDACi) show promise in reversing cognition in AD mice models by increasing global histone acetylation45–47. Indeed, two HDAC inhibitors, Vorinostat (SAHA, Zolinza)48 and Nicotinamide (Vitamin B3)49 have now advanced to Phase I and Phase II clinical trials for treatment of AD, respectively. Unfortunately, most available HDAC inhibitors cause detrimental side effects due to their non-selective nature in targeting multiple HDACs resulting in non-specific global hyperacetylation and gene activation and inhibition of required HDAC function in cognition, thereby limiting their use in the development of AD therapeutics12,50. For example, Vorinostat is a pan-inhibitor for class I and class II HDACs (HDACs 1-10) and although effective in AD animal models, is not considered beneficial at safe doses for humans and its negative side effects likely prohibit its use for AD population51,52. Similarly, Nicotinamide is a pan-inhibitor for all class III sirtuin HDACs (SIRT1-7) that has failed to improve cognitive function in Phase II clinical trial for treatment of mild to moderate AD53 and shown to exacerbate Parkinson’s pathology54.

Alternatively, fine-tuning of histone acetylation levels by activating specific HATs is a promising therapeutic strategy for treating neurodegenerative diseases9,10,15. Available HAT activators exclusively target HATs that fall under the p300/CBP (KAT3) HAT family and include lead compounds CTB and CTBP that both target p30055. We reasoned that generating selective Tip60 HAT activator compounds would represent a major advance over these KAT3 HAT activators for the following reasons. First, Tip60 belongs to the MYST family of HATs that have a distinct catalytic HAT domain resulting in enzymes that differ from the KAT3 family with regards to protein structure and the specific histone modification substrates and genes they target16,56. Second, no MYST family HAT activators have been published prior to this study9,15. Third, although p300 HAT is a ubiquitously expressed global transcriptional regulator that has been implicated in cancer57,58, there is no direct evidence supporting that it plays a neuroprotective role in AD in vivo. In contrast, Tip60 HAT is downregulated in postmortem AD patients’ brains and multiple Drosophila AD models, and restoring Tip60 levels is sufficient to reverse the neuroepigenetic synaptic plasticity gene repression and cognition deficits in flies modeling AD18,19. As a cautionary note, site-specific target histone acetylation for selective HAT activators is an important consideration in compound design as histone modification alterations are likely nuanced, and may vary for different diseases, stages and brain subregions. For example, Marzi et al. found histone acetylation to be differentially altered in AD patients for H3K27ac in the postmortem entorhinal cortex brain region, whereas while most sites were depleted for acetylation, some were enriched59. In contrast, Nativio et al. found dramatic loss of H4K16ac in the proximity of genes associated with aging and AD in the lateral temporal lobe of postmortem AD patients’ brains60. Accordingly, Hendrickx et al. demonstrated APP-mediated hypoacetylation of H4 at critical learning and memory genes in prefrontal cortex of mouse brain61. To this end, several key studies support that H4K16 is a preferential histone acetylation target for Tip60 HAT over CBP/p3001,9,25,56,62, and importantly, H4K16 acetylation is directly implicated in cognition1,18 and AD60, potentially making Tip60 HAT activators compounds a more selective and effective AD treatment over KAT3 HAT activators9. In support of this concept, here we show that our Tip60 activators P10 and P13 are more effective in rescuing AD-associated neuronal functional locomotion deficits in APP larvae than the C2 compound that displays higher resemblance to KAT3 HAT activator CBT. Furthermore, P compounds promote longevity in APP flies and restore expression of repressed Tip60 neuroplasticity target genes in the AD fly brain. In this regard, our previous genome-wide chromatin binding and transcriptome studies revealed that AD-associated APP larval brains exhibit enhanced HDAC2 and reduced Tip60 binding at identical neuroplasticity genes genome-wide with concomitant transcriptional dysregulation that is conserved at orthologous human genes in AD patient hippocampi19. Our results support a model by which Tip60 and HDAC2 compete for binding at the same neuronal genes, with their access dependent upon the disease state19. Genetically increasing Tip60 levels in the APP brain reduced both inappropriately enhanced HDAC2 levels and binding enrichment at Tip60 neuronal target genes, allowing for restoration of Tip60-mediated histone acetylation and gene expression18,19. Thus, we speculate that pharmacological activation of the reduced Tip60 in the human and Drosophila AD brain by our P compounds recapitulates this mechanism to promote neuronal gene activation under AD conditions (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. Tip60 HAT activation as a unique therapeutic strategy for restoring histone acetylation homeostasis mediated cognition in Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

In the healthy brain (left), the balance between Tip60 HAT and HDAC2 enzymes maintains histone acetylation homeostasis necessary for chromatin relaxation and neural gene expression that drives dynamic neural processes. However, in the AD brain (right), loss of Tip60 HAT and/or gain of HDAC2 activity results in reduced histone acetylation levels that condenses chromatin and represses critical neuronal genes resulting in cognitive decline. Tip60 activators selectively enhance its catalytic function to restore histone acetylation levels in the AD brain that should promote expression of critical neural genes and therefore, ameliorate cognitive function in the AD brain. (Created in BioRender. Bhatnagar, A. (2025) https://BioRender.com/a43t168).

In conclusion, we have developed a series of Tip60 selective activators and demonstrated their efficacy in a proof-of-concept study in improving motor and cognitive deficits in a Drosophila model of AD. Some of the limitations in this study include (a) lack of in vivo mammalian studies, to demonstrate the translational potential of our compounds and (b) limited exploration of the pharmacokinetics and safety/toxicology studies under systemic administration of the compounds. While we acknowledge these limitations in the current study, it must be noted that the MYST HAT domain in the Drosophila and the human Tip60 shows 89% similarity and 80% identity of amino acids, and their three-dimensional modeled structures of the HAT domains superimpose with a root mean squared deviation of <1 Å. In addition to the high protein structural similarity, Tip60’s protein function is conserved with the mammalian systems as well. Tip60 direct gene targets identified in the Drosophila brain for AD-associated changes in gene expression18,19 or RNA splicing63 were found to be similarly targeted in the human postmortem brain19,63. Based on this information, our design strategy was to use the human Tip60 structure (Fig. 1) to design drugs and perform in vitro testing using the human Tip60 protein (SPR; Fig. 2B) and HAT assay (Fig. 6). Interestingly, our compounds restore brain-specific expression of critical Drosophila homologs of major mammalian cognition genes that are direct targets of Tip60 and repressed in the AD-associated APP neurodegenerative Drosophila brain, demonstrating Tip60 conservation across both the species (Fig. 8I).

Throughout the drug discovery process, we have selected for optimal pharmacokinetics properties wherever feasible. For example, Fluorine (F) substitution has been well documented to help small compounds cross blood–brain barrier (BBB) by increasing the lipophilicity of the compound30. Therefore, in both of the drug design approaches, we attempted to either keep the fluorine halogen or substitute it for another hydrophobic molecule29. However, there are limitations to these approaches as in general, drug discovery routinely involve multiple rounds of testing and optimization before finding the most clinically effective compounds43. Therefore, future directions of this project will involve lead optimization with targeted medicinal chemistry to obtain late leads that will be tested for in vivo pharmacokinetics and efficacy in mammalian models of AD. Since AD is a complex disease involving genetic and epigenetic factors, Tip60 activators may be suitable as a combinatorial therapy along with genetic therapeutic strategies, and these small molecules provide an opportunity to explore these combination therapies.

Methods

Fly strains and crosses

All fly lines were raised on standard yeast Drosophila medium (Applied Scientific Jazz Mix Drosophila Food, Thermo Fischer Scientific) at 25 °C with 12/12-h light/dark cycle. The pan-neuronal driver elavC155-Gal4, transgenic Tip60-RNAi line 1(UAS-Tip60 RNAi-1; Stock 28563), and the transgenic UAS lines carrying human APP 695 isoform (UAS-APP) were obtained from Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center. Tip60-RNAi-2 mediated knockdown line (UAS-Tip60 RNAi-2) was gifted to us by Dr. Nancy Bonini (University of Pennsylvania). Tip60-RNAi target sequence was tested using BLAST tools to confirm predicted uniqueness within the fly genome to rule out off-target effects. For neural Tip60 knockdown and APP expression, the elavC155-Gal4 driver line was crossed with UAS-Tip60RNAi or UAS-APP, and the progeny was collected as Tip60 knockdown model (elavC155-Gal4/UAS-Tip60 RNAi) or AD-associated APP model (elavC155-Gal4/UAS-APP). For wild-type control, the elavC155-Gal4 driver line was crossed with itself (elavC155-Gal4/ elavC155-Gal4). w1118 is the genetic background for all fly lines used. Outcross controls are shown in Supplementary Fig. 4A–D. Model validation was performed by confirming reduced Tip60 mRNA levels in Tip60-RNAi model as compared to wild-type using real-time PCR. For all experiments, both males and females were used.

Drug delivery

All compounds were purchased from Enamine, Princeton BioMolecular Research and ChemBridge libraries and their source, and identity chemical names and purity and their NMR/LCMS profiles are listed in Supplementary Table 6 and Supplementary Methods. Methods of synthesis are available from the respective library the compound was purchased from. All compounds fully comply with the chemical probes small-molecule guidelines. The compounds were incorporated into the fly food and fed to the progeny larvae and flies. DMSO was used as a vehicle to prepare drug solutions. The fly food was prepared under standard conditions and aliquoted into individual vials. The drug solutions were then added to the fly vials with final DMSO concentration ≤0.01% and DMSO only was used as a control. The parental crosses were set up in the drug food vials so that the resulting progeny larvea feed on the drug immediately upon hatching from egg casing unless otherwise indicated.

In silico ligand-based virtual screening

A curated version of ZINC15 compound library37 of commercially available compounds was used for high-throughput virtual screening. For the substructure search, the SMILES (CCOC1 = CC = CC = C1C( = O)NC2 = CC( = C(C = C2)Cl)C(F)(F)F) for CTB compound (PubChem: 729859): N-[4-chloro-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-2-ethoxybenzamide were inserted in the query section. The top 100 compounds were exported as a.mol2 file that was used for protein–ligand docking on the GOLD software28. GOLD software is widely used for virtual screening of protein–ligand interactions and lead optimization38,64,65. For pharmacophore-based search, CTB was docked on Tip60’s HAT domain (PDB:2ou2), and interactions were limited with filters H-bond = −0.2, distance 6 Å and energy = −0.5 to isolate the “overall” essence of the structure‐activity knowledge. Drug-like compounds were screened on a curated ZINC15 database with purchasable compounds using two pharmacophore modeling searches. Major pharmacophore modeling features include H-bond acceptor, H-bond donor, anionic, cationic, hydrophobic, and aromatic groups. To generate a pharmacophore model of CTB, we utilized the pharmacophore editor feature in Molecular Operating Environment (Chemical Computing Group ULC). A total of six pharmacophore features were identified in CTB: two aromatic rings (F1, F2), one hydrogen donor site (F3), one hydrogen acceptor site (F4), and two hydrophobic sites (F5, F6) (Fig. 4). Using these pharmacophore features, a standard pharmacophore-based virtual screening pipeline was employed for identification of Tip60 HAT activators (Fig. 4). and results were combined and filtered for GOLD docking score of 78. Since fluorine (F) substitution has been well documented to help small compounds cross blood–brain barrier (BBB) by increasing lipophilicity of the compound44,66, we retained fluorine halogen or found another hydrophobic group for substitution in our compounds. Supplementary Table 4 provide additional information about our high-throughput screening of small molecules for Substructure-based and Pharmacophore-based virtual screens, respectively.

In silico protein–ligand docking

All protein–ligand docking was performed using genetic algorithm methodology of GOLD docking software (Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre)28. Twenty conformations were used for every ligand to sample the conformational space. The Acetyl-CoA binding pocket of Tip60’s HAT domain (PDB:2ou2) was identified by using a 10 Å filter and was composed of the following residues: LEU354, GLU351, HIS274, ILE318, ASP273, PHE271, CYS317, SER355, LEU272, LEU357, SER361, THR320, GLY330, GLY328, LYS331, ARG326, GLN325, ARG327, and TYR324. A flexible docking option was used so both the protein and the ligands are treated flexibly to optimize the fit. The protein−ligand complexes were scored using the default Gold score method available from the GOLD docking program.

In vitro surface plasma resonance (SPR)

Briefly, a GST capture assay was optimized to tether GST-Tip60 on a sensor surface and measure compounds (WM8014, CTB and CTBP) binding with an expected stoichiometry S = 1. All SPR immobilization and binding experiments were performed at 25 °C using a high-sensitivity Biacore S200 instrument (GE Healthcare) bearing a CM5 sensor. A CM5 sensor chip was docked and derivatized by amine coupling to capture anti-GST antibody (Invitrogen MA4-004). Surfaces were activated sequentially by injecting 7 min, 35 µL of a mixture of 1:1 of freshly prepared 50 mM NHS (N-hydroxysuccinamide): 200 mM EDC (1-ethyl-3-(3-(dimethylamino) propyl) carbodiimide). Immediately after, anti-GST antibody was injected 10 min at 5 µL/min, followed by immobilization of GST-Tip60 protein (Abcam: ab268696) at 1 µL/min. GST protein (Rockland 000-001-200) was captured on a reference surface used to correct the compounds binding signal. A dose-response assay to control for captured GST-TIP60 activity was conducted using anti-Tip60 antibody (Abcam #23886) at concentrations spanning 1.16–250 nM. Binding of compounds was first measured using an equilibrium titration mode. The HAT-optimized running and sample buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 500 mM NaCl, 0.05% [v/v] Tween 20, 5 mM DTT, 10% [w/v] glycerol, 2% [v/v] DMSO) was used. Off-rates were fast (0.7–1/s) so no regeneration was required as compounds formed were fully dissociated in running buffer. Direct binding was determined by injecting ligands in duplicates at concentrations spanning 0.0078–50 μM with running buffer injections in between. The data was corrected for non-specific binding to the reference surface containing anti-GST antibody only as well as corrected for DMSO solvent in which the compounds were dissolved (Supplementary Table 1). For DMSO corrections, the established method was taken from ref. 67. Briefly, a series of five calibration solutions (running buffer with 2.5 ± 0.37% DMSO concentrations) were run at the beginning and end of each experiment. The responses of the calibration solutions, obtained from the reference surface, covered a range from −100 to +2500 RU relative to the baseline. A DMSO calibration curve was created by plotting the difference in response between Tip60 and GST reference flow cell versus response in reference flow cell to determine the DMSO correction factor from the slope of the line. The corrected responses were transformed into % bound sites and plotted against the compound concentration. The concentration of Tip60 on the surface was estimated using [Tip60] = response (captured RU)/100* MW. To plot the % bound isotherm as a function of concentration, it is assumed that binding is 1:1 and the following equation is used: %A bound to B is 100AB/Bt = [Kd+At+Bt – SQRT((Kd+At+Bt)2-4*At*Bt)]/(2*Bt) where A=Compound and B=Tip60. Given the low solubility of the compounds, concentrations >50 μM could not be tested using SPR and hence the KD values for the compounds were derived relative to the previously published KD value for WM8014, a known Tip60 inhibitor32.

In vivo locomotor speed and line crossing assays

The line crossing apparatus consisted of a Petri dish containing 2.5% agar positioned on a 0.5 cm2 grid paper. Wandering third instar of either sex larvae were collected from fly vials and rinsed with distilled water. The larvae were placed in the center of Petri dish and allowed to acclimate for 1 min. After initial acclimation, the larvae were recorded for 30 s on the plate. Larval speed (mm/s) was analyzed using Tracker software (http://physlets.org/tracker/) using the videos of distance individual larvae traveled in 1 min. For the line crossing assay, the number of lines crossed by the head of a larvae in 30 s on a grid 0.5 cm × 0.5 cm was recorded. We observed no locomotion deficits for all outcross controls (elav × w1118; w1118 x UAS-Tip60RNAi; w1118 x UAS-APP) (Supplementary Fig. 3).

In vitro histone acetylation activity assay

HAT assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions in HAT Assay Kit (Active Motif 56100). Briefly, 375 ng Tip60 protein (Active motif: 81975) was incubated with 50 μM Histone H4 peptide, 50 μM Acetyl-CoA, and indicated drug concentrations for 30 min at room temperature. After stopping the reaction and developing free sulfhydryl groups, absorbance was recorded at excitation 360–390 nm and emission 460–490 nm using Glomax fluorescence microplate reader. Specific enzyme activity (pmol/min/μg) was calculated by (1) Subtracting background fluorescence from that of assay samples to obtain arbitrary fluorescence units (AFU). (2) Dividing the difference by the incubation time to obtain AFU/min. (3) Dividing the AFU/min by the slope of the standard curve in AFU/pmol to obtain the rate in pmol/min. (4) Dividing pmol/min by the amount of enzyme used to obtain final readings in pmol/min/μg.

Reverse transcriptase real-time PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from 50 staged third-instar larval brains using the Quick-RNA Miniprep kit (Zymo research). cDNA was prepared using the SuperScript II reverse transcriptase kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with 1 μg of total RNA. Primers were designed using NCBI Primer-BLAST and the primer pair specificity was analyzed using the reference sequence database of Drosophila melanogaster (taxid: 7227). RT-qPCRs were performed in a 10 μl reaction volume containing cDNA, 1 μM Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), and 10 μM forward and reverse primers. All primer sequences used are included in Supplementary Table 5. Real-time. qPCR was performed using an ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Fold change in mRNA expression was determined by the δδCt method relative to wild-type using Rpl32 as the housekeeping gene.

In vivo pupation and eclosion assay

Parental crosses were set up on fly food media containing either indicated drug solutions or DMSO vehicle (control) at 25 °C. For each drug, the most effective concentrations determined via locomotion assay were used. Parental crosses were removed 7 days after to ensure pupation and eclosion data is soley from progeny. The progeny pupation was assessed by counting individual pupa from days 11 to 21 of their lifecycle and recorded daily. Eclosion rate for both sexes was assessed by counting the total amount of progeny flies that eclosed from the pupal case completely divided by the total number of pupae per vial.

In vivo longevity assay

Parental crosses were set up on fly food media containing either drug solutions or DMS0 vehicle (control). For each drug, the most effective drug concentration determined via locomotion assay was used. Newly eclosed adult flies of either sex were collected within a 24-h period and transferred to a vial containing drug or DMSO with a minimum of 48 flies tested per genotype. This day was marked as “Day 0”. The flies were transferred to new vials containing fresh food with respective drug or DMSO solutions every 4 days, and the surviving flies were counted daily. The experiment was discontinued on day 40, 10 days after there were no surviving APP flies.

Experimental design and statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 9.5.1 software package. For qPCR analysis in Fig. 8I, statistical significance was calculated using two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons with P < 0.05. For qPCR analysis in Supplementary Fig. 1, statistical significance was calculated using unpaired two-tailed T test with P < 0.05. For locomotor speed assays, statistical significance between the wild-type with vehicle, Tip60-RNAi or APP with vehicle and Tip60-RNAi or APP with various drug concentrations was calculated using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons with P < 0.05. For HAT assay, the statistical significance of drugs on enzyme activity was calculated using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons to the DMSO control sample. For the longevity assay, statistical significance was calculated using Logrank (Mantel–Cox) Test and Gehan–Breslow–Wilcoxon Test. No data were excluded from the analysis. All specific sample numbers (n) and F values for each experiment are provided in Supplementary Table 7.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Tip60-compound panel analysis was supported by the Drexel-SKCC/TJU Biacore S200™ Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Biosensor Shared Instrument Facility (https://drexel.edu/medicine/research/facilities/biacore-s200-surface-plasmon-resonance-biosensor) with assistance of Gabriela Canziani, S200 manager-operator, and the guidance of Irwin Chaiken professor at the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology and facility director. Research reported in this publication was supported by the Office Of The Director, National Institutes Of Health under Award Number S10OD027009 that funded the S200 biosensor. Drosophila Tip60 RNAi-2 was generously gifted by Drs. Nancy Bonini and Xiuming Quan, University of Pennsylvania. All work was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke grants RF1NS095799 and R01NS095799 to F.E.

Author contributions

A.B., C.M.T., S.K., and F.E. designed research; A.B., C.M.T., G.G.N., R.D., A.Z., B.M., and N.C. performed research; A.B., C.M.T., G.G.N., R.D., N.C., B.M., and F.E. analyzed the data; A.B. and F.E. wrote the paper; A.B., C.M.T., G.G.N., S.K., and F.E. edited the paper.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Anna King, Andrew Phipps and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper as a Source Data file.

Competing interests

Compounds C1–C10 and P1–P13 described in this manuscript are listed in the U. S. Patent Application No. 18/891,352, filed September 20, 2024; S.K., A.B., and F.E. are named inventors on the patent. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Akanksha Bhatnagar, Christina M. Thomas.

These authors jointly supervised this work: Aprem Zaya, Rohan Dasari, Neha Chongtham, Bijaya Manandhar.

Contributor Information

Sandhya Kortagere, Email: sk673@drexel.edu.

Felice Elefant, Email: fe22@drexel.edu.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-025-58496-w.

References

- 1.Stilling, R. M. & Fischer, A. The role of histone acetylation in age-associated memory impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem.96, 19–26 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Killin, L. O., Starr, J. M., Shiue, I. J. & Russ, T. C. Environmental risk factors for dementia: a systematic review. BMC Geriatrics16, 1–28 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peserico, A. & Simone, C. Physical and functional HAT/HDAC interplay regulates protein acetylation balance. J. Biomed. Biotechnol.2011, 371832 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berson, A., Nativio, R., Berger, S. L. & Bonini, N. M. Epigenetic regulation in neurodegenerative diseases. Trends Neurosci.41, 587–598 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saha, R. & Pahan, K. HATs and HDACs in neurodegeneration: a tale of disconcerted acetylation homeostasis. Cell Death Differ.13, 539 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gräff, J. et al. An epigenetic blockade of cognitive functions in the neurodegenerating brain. Nature483, 222 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu, X., Wang, L., Yu, C., Yu, D. & Yu, G. Histone acetylation modifiers in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Cell. Neurosci.9, 226–226 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peixoto, L. & Abel, T. The role of histone acetylation in memory formation and cognitive impairments. Neuropsychopharmacology38, 62–76 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Selvi, B. R., Cassel, J.-C., Kundu, T. K. & Boutillier, A.-L. Tuning acetylation levels with HAT activators: therapeutic strategy in neurodegenerative diseases. Biochim. et. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gene Regul. Mechan.1799, 840–853 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schneider, A. et al. Acetyltransferases (HATs) as targets for neurological therapeutics. Neurotherapeutics10, 568–588 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mantelingu, K. et al. Activation of p300 histone acetyltransferase by small molecules altering enzyme structure: probed by surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B111, 4527–4534 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Didonna, A. & Opal, P. The promise and perils of HDAC inhibitors in neurodegeneration. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol.2, 79–101 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rouaux, C. et al. Critical loss of CBP/p300 histone acetylase activity by caspase‐6 during neurodegeneration. EMBO J.22, 6537–6549 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valor, L. M. et al. Lysine acetyltransferases CBP and p300 as therapeutic targets in cognitive and neurodegenerative disorders. Curr. Pharm. Des.19, 5051–5064 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pirooznia, S. K. & Elefant, F. Targeting specific HATs for neurodegenerative disease treatment: translating basic biology to therapeutic possibilities. Front. Cell. Neurosci.7, 30 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim, C.-H. et al. The chromodomain-containing histone acetyltransferase TIP60 acts as a code reader, recognizing the epigenetic codes for initiating transcription. Biosci., Biotechnol. Biochem.79, 532–538 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu, S. et al. Epigenetic control of learning and memory in Drosophila by Tip60 HAT action. Genetics198, 1571–1586 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Panikker, P. et al. Restoring Tip60 HAT/HDAC2 balance in the neurodegenerative brain relieves epigenetic transcriptional repression and reinstates cognition. J. Neurosci.38, 4569–4583 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beaver, M. et al. Chromatin and transcriptomic profiling uncover dysregulation of the Tip60 HAT/HDAC2 epigenomic landscape in the neurodegenerative brain. Epigenetics17, 786–807 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson, A. A., Sarthi, J., Pirooznia, S. K., Reube, W. & Elefant, F. Increasing Tip60 HAT levels rescues axonal transport defects and associated behavioral phenotypes in a Drosophila Alzheimer’s disease model. J. Neurosci.33, 7535–7547 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lorbeck, M., Pirooznia, K., Sarthi, J., Zhu, X. & Elefant, F. Microarray analysis uncovers a role for Tip60 in nervous system function and general metabolism. PLoS ONE6, e18412 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pirooznia, S. K. et al. Tip60 HAT activity mediates APP induced lethality and apoptotic cell death in the CNS of a Drosophila Alzheimer’s disease model. PLoS ONE7, e41776 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarthi, J. & Elefant, F. dTip60 HAT activity controls synaptic bouton expansion at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. PLoS ONE6, e26202 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu, S., Panikker, P., Iqbal, S. & Elefant, F. Tip60 HAT action mediates environmental enrichment induced cognitive restoration. PLoS ONE11, e0159623 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu, X., Singh, N., Donnelly, C., Boimel, P. & Elefant, F. The cloning and characterization of the histone acetyltransferase human homolog Dmel\TIP60 in Drosophila melanogaster: Dmel\TIP60 is essential for multicellular development. Genetics175, 1229–1240 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Beaver, M. et al. Disruption of Tip60 HAT mediated neural histone acetylation homeostasis is an early common event in neurodegenerative diseases. Sci. Rep.10, 18265 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kortagere, S. & Welsh, W. J. Development and application of hybrid structure based method for efficient screening of ligands binding to G-protein coupled receptors. J. Compout. Aided Mol. Des.12, 789–802 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones, G., Willett, P., Glen, R. C., Leach, A. R. & Taylor, R. Development and validation of a genetic algorithm for flexible docking. J. Mol. Biol.267, 727–748 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gentry, C. et al. The effect of halogenation on blood–brain barrier permeability of a novel peptide drug☆. Peptides20, 1229–1238 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castillo-Garit, J. A., Casanola-Martin, G. M., Le-Thi-Thu, H., Pham-The, H. & Barigye, S. J. A simple method to predict blood-brain barrier permeability of drug-like compounds using classification trees. Med Chem.13, 664–669 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang, Y., Zeng, X. & Liang, J. Surface plasmon resonance: an introduction to a surface spectroscopy technique. J. Chem. Educ.87, 742–746 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baell, J. B. et al. Inhibitors of histone acetyltransferases KAT6A/B induce senescence and arrest tumour growth. Nature560, 253–257 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Su, T. T. Drug screening in Drosophila; why, when, and when not? Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol.8, e346 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gasque, G., Conway, S., Huang, J., Rao, Y. & Vosshall, L. B. Small molecule drug screening in Drosophila identifies the 5HT2A receptor as a feeding modulation target. Sci. Rep.3, srep02120 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lenz, S., Karsten, P., Schulz, J. B. & Voigt, A. Drosophila as a screening tool to study human neurodegenerative diseases. J. Neurochem.127, 453–460 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brand, A. H. & Perrimon, N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development118, 401–415 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sterling, T. & Irwin, J. J. ZINC 15—ligand discovery for everyone. J. Chem. Inf. Modeling55, 2324–2337 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones, G., Willett, P. & Glen, R. C. Molecular recognition of receptor sites using a genetic algorithm with a description of desolvation. J. Mol. Biol.245, 43–53 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kortagere, S., Krasowski, M. D. & Ekins, S. Ligand-and structure-based pregnane S receptor models. Methods Mol. Biol.929, 359–375 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lill, M. In In Silico Models for Drug Discovery (ed. Kortagere, S.) 1–12 (Humana Press, 2013).

- 41.Miech, C., Pauer, H. U., He, S. & Schwarz, T. L. Presynaptic local signaling by a canonical wingless pathway regulates development of the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. J. Neurosci.28, 10875–10884 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhatnagar, A. et al. Novel EAAT2 activators improve motor and cognitive impairment in a transgenic model of Huntington’s disease. Front. Behav. Neurosci.17, 1176777 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rudrapal, M. & Egbuna, C. Computer Aided Drug Design (CADD): From Ligand-Based Methods to Structure-Based Approaches (Elsevier, 2022).

- 44.Kortagere, S., Ekins, S. & Welsh, W. J. Halogenated ligands and their interactions with amino acids: implications for structure-activity and structure-toxicity relationships. J. Mol. Graph Modeling2, 170–177 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomas, E. A. et al. The HDAC inhibitor 4b ameliorates the disease phenotype and transcriptional abnormalities in Huntington’s disease transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA105, 15564–15569 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang, C. & Zhang, C. Novel HDAC11 inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease treatment in preclinical models. Alzheimer’s. Dement.18, e069366 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Janczura, K. J. et al. Inhibition of HDAC3 reverses Alzheimer’s disease-related pathologies in vitro and in the 3xTg-AD mouse model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA115, E11148–E11157 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 48.NCT03056495. Clinical Trial to Determine Tolerable Dosis of Vorinostat in Patients With Mild Alzheimer Disease, 2017. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03056495.

- 49.NCT03061474. Nicotinamide as an Early Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment (NEAT), 2017. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03061474.

- 50.Jeong, H. et al. Pan-HDAC inhibitors promote Tau aggregation by increasing the level of acetylated Tau. Int. J. Mol. Sci.20, 4283 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hanson, J. E. et al. SAHA enhances synaptic function and plasticity in vitro but has limited brain availability in vivo and does not impact cognition. PLoS ONE8, e69964 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cognitive-vitality-report. Vorinostat (Zolinza). Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundationhttps://www.alzdiscovery.org (2018).

- 53.Phelan, M., Mulnard, R., Gillen, D. & Schreiber, S. Phase II clinical trial of nicotinamide for the treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. J. Geriatr. Med. Gerontol.3, e21 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harrison, I. F., Powell, N. M. & Dexter, D. T. The histone deacetylase inhibitor nicotinamide exacerbates neurodegeneration in the lactacystin rat model of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurochem.148, 136–156 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Devipriya, B., Parameswari, A. R., Rajalakshmi, G., Palvannan, T. & Kumaradhas, P. Exploring the binding affinities of p300 enzyme activators CTPB and CTB using docking method. Indian J. Biochem Biophys.47, 364–369 (2010). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berndsen, Ca. D. JM. Catalysis and Substrate selection by histone/protein lysine acetyltransferase. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol.18, 682–689 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lau, O. D. et al. HATs off: selective synthetic inhibitors of the histone acetyltransferases p300 and PCAF. Mol. Cell5, 589–595 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen, Q. et al. Histone acetylatransferases CBP/p300 in tumorigenesis and CBP/p300 inhibitors as promising novel anticancer agents. Theranostics12, 4935–4948 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marzi, S. et al. A histone acetylome-wide association study of Alzheimer’s disease identifies disease-associated H3K27ac differences in the entorhinal cortex. Nat. Neurosci.21, 1618–1627 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Natvio, R. et al. Dysregulation of the epigenetic landscape of normal aging in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci.21, 497–505 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hendrickx, A. et al. Epigenetic regulations of immediate early genes experssion involved in memory formation by the amyloid precursor protein of Alzheimer disease. PLoS ONE9, e99467 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kimura, A. & Horikoshi, M. Tip60 acetylates six lysines of a specific class in core histones in vitro. Genes Cells3, 789–800 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bhatnagar, A. et al. Tip60’s novel RNA-binding function modulates alternative splicing of pre-mRNA targets implicated in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci.43, 2398–2423 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Verdonk, M. L., Cole, J. C., Hartshorn, M. J., Murray, C. W. & Taylor, R. D. Improved protein–ligand docking using GOLD. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Bioinforma.52, 609–623 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cole, J., Nissink, J. & Taylor, R. Protein-ligand docking and virtual screening with GOLD. Virtual Screen. Drug Discov.1, 379–415 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 66.The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, 2015. Version 2.0 Schrödinger, LLC.

- 67.Frostell-Karlsson, Å. et al. Biosensor analysis of the interaction between immobilized human serum albumin and drug compounds for prediction of human serum albumin binding levels. J. Med. Chem.43, 1986–1992 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Source data are provided with this paper as a Source Data file.