Abstract

Fungal infections throughout the world appear to be increasing. This may in part be due to the increase in the population of patients that are susceptible to otherwise rare fungal infections resulting from the use of immune modulating procedures such as hematopoietic stem cell transplants and drugs like tissue necrosis factor antagonists. Histoplasma capsulatum, an endemic fungus throughout North and South America, is reemerging among HIV+ patients in Central and South America and among patients taking tissue necrosis factor antagonists and other biologics in North America. Fusarium species, a relatively rare fungal infection, is reemerging worldwide in the immunocompromised populations, especially those who are neutropenic like hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. A new yeast species is currently emerging worldwide: Candida auris, unknown just a decade ago. It is causing large healthcare-associated outbreaks on four continents and is spreading throughout the world through patient travel. In this review the epidemiology, pathology, detection and treatment of these three emerging and reemerging fungi will be discussed.

Keywords: Fungi, Histoplasma, Fusarium, Candida auris

Introduction

The worldwide incidence of fungal infections appears to be increasing.1 Although there are multiple reasons for this increase, one leading risk factor for invasive fungal infection is immune modulation of the host, including receipt of solid organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCT), and the use of immune modifiers such as tissue necrosis factor (TNF) antagonists to treat several chronic inflammatory diseases. The number of patients receiving HSCT has dramatically increased in the last decade, leading to marked increase in the number of patients experiencing at least transient neutropenia.2 TNF inhibitors are some of the top selling drugs in clinical practice; as their number and applications multiply, their use will keep increasing.3 However, the increase in HSCT and the widespread use of immune modifying drugs, among other factors, has created an entirely new population of patients at risk for fungal infections. The number of different fungi causing infections may be increasing as well. Endemic fungal infections caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, Blastomyces dermatitidis and Coccidioides immitis/posadasii appear to be on the rise. So have environmentally acquired infections such as aspergillosis, fusariosis and mucormycosis, and healthcare-associated infections like candidiasis. This review will discuss two fungi, H. capsulatum and Fusarium, which are not as frequently diagnosed as Candida, Aspergillus and the Mucorales, but which are reemerging, as they have found a niche among this new patient population. In addition, we will review characteristics of Candida auris, a yeast with substantial public health and hospital infection control implications which has suddenly appeared in the last decade.

Histoplasmosis

The causative agent of histoplasmosis is H. capsulatum, a thermally dimorphic fungus found in the environment and specifically associated with bird and bat guano.4 Although isolated cases occur in Africa, Asia, Australia and Europe, histoplasmosis is predominantly endemic to the United States and certain parts of Central and South America.5 Cases of histoplasmosis are increasing in the United States and this has caused an increased number of histoplasmosis-associated hospitalizations.6 While HIV has been the primary comorbidity associated with histoplasmosis hospitalization over the last several decades, histoplasmosis hospitalization is increasingly associated with diabetes, transplant, and the use of TNF blockers. It remains one of the more common AIDS defining illnesses in Central and South America, and because the symptoms of histoplasmosis mimic those of tuberculosis, it can be difficult to differentiate between these two syndromes without definitive laboratory testing.7,8

The majority of Histoplasma infections in normal hosts are subacute, with only about 5% of patients having an influenza-like illness.9 In patients with impaired cellular immunity or those who have been exposed to an overwhelming inoculum of conidia, infection normally begins as an acute pulmonary infection which can subsequently progress to a chronic cavitary infection. Histoplasmosis can also disseminate, especially to the reticuloendothelial system, liver, spleen, bone marrow, central nervous system, gastrointestinal tract, endocardium, and the skin.10

Symptoms of acute pulmonary pneumonia with Histoplasma include fever, headache, dyspnea and a dry cough.9 Radiographic findings include patchy infiltrates in one or more lobes, pulmonary nodules and enlarged hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes.11 In chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis a productive cough, night sweats, low-grade fever and weight loss are typical, and cavitation and fibrosis in the lungs can occur. Dissemination can manifest in immunocompromised patients or patients who have been exposed to an overwhelming inoculum. Nonspecific symptoms in patients with disseminated histoplasmosis include fever, fatigue, weight loss and general malaise. Respiratory symptoms are common, as are splenomegaly and hepatomegaly.4,9

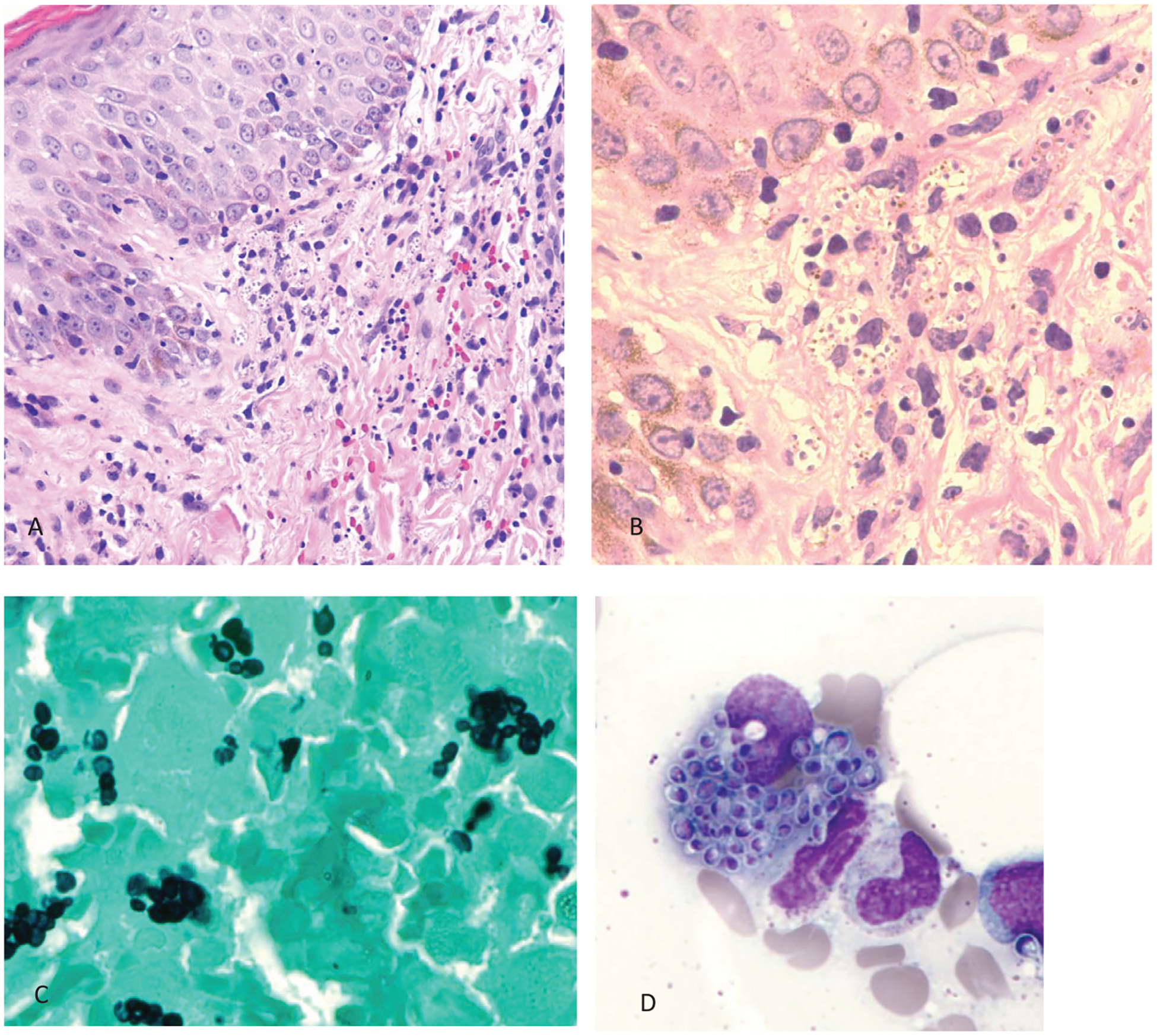

Histoplasma reproduces in tissue as round to oval, 2–4 μm, narrow-based budding yeast cells. These cells are typically found inside macrophages, hence their usual arrangement in clusters (Fig. 1), especially in lung tissue, but they can also be seen as free yeast cells. Histoplasma cells are best visualized in tissue using a methenamine silver or periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain. Giemsa staining is effective for visualizing Histoplasma cells in bronchoalveolar lavages (BAL). In culture at room temperature, Histoplasma is a slow-growing hyaline mold with club-shaped microconidia as well as tuberculate macroconidia. While visualization of hyphae in tissue can usually be used to rule out Histoplasma, in cardiac tissue Histoplasma can grow as short hyphae.12 Pathologists need to recognize that other small yeast can be confused with Histoplasma, thus it is best to describe the yeasts observed, budding pattern and arrangement as the diagnosis. They should state that the yeasts seen are likely Histoplasma and suggest the use of alternative tests such as the urine antigen test.

Fig. 1.

Case of disseminated histoplasmosis in skin and bone marrow. A: Skin with mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate in the upper dermis (hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification 100×). B: Higher magnification (250×) of hematoxylin and eosin stain showing macrophages filled up with Histoplasma. C: Grocott methenamine silver stain highlighting the Histoplasma inside the macrophages from the bone marrow biopsy (original magnification 250×). D: Macrophage with multiple Histoplasma from the bone marrow aspirate (Giemsa stain, original magnification 250×).

Culture is the gold standard for diagnosis of histoplasmosis. Both the yeast phase at 37 °C and the mold phase at 25 °C grow slowly and it can take up to four weeks to rule out Histoplasma by culture. The best specimens for culture are sputum or BAL for acute pulmonary infections, and blood culture, tissue biopsy, or bone marrow for disseminated infections. Under the best conditions culture is only positive in up to 75% of cases.13 Detection of Histoplasma urine antigen may be the most rapid and sensitive test for an acute infection.14–16 A serum antigen test is available but may not contribute to further detection when the urine antigen assay is used.17 Immunodiffusion and complement fixation tests for the detection of anti-Histoplasma antibodies are not commercially available but are available in some public health and commercial laboratories. Alone, they may not be ideal for detection of acute infection as antibodies can take 4–8 weeks to develop.18 Combining antigen and antibody testing can increase the sensitivity of detection of acute pulmonary histoplasmosis to 96%.19 There are many laboratory-developed molecular tests for Histoplasma, but none are commercially available.20,21 A commercially available chemiluminescent probe kit (Gen-Probe®) is useful for definitive identification of Histoplasma from an isolate.22

In otherwise healthy individuals mild histoplasmosis generally resolves without treatment. In cases of acute and chronic pulmonary or disseminated histoplasmosis treatment is generally amphotericin B followed by itraconazole for severe cases or intraconazole alone for less severe cases. The dose and duration of therapy depend both on the severity of the disease and the underlying immune status of the patient. Treatment guidelines are available.23

Fusariosis

Fusarium species are plant pathogens that are widely distributed across the world, thriving in both tropical and temperate regions and causing serious economic damage to commercial crops. The first case of human disease reported in the literature, a keratitis case, was not reported until 1958.24 Although keratitis is still the predominant manifestation of infection, Fusarium also causes localized infections of the respiratory tract and sinuses. In immunocompromised patients, especially those with profound neutropenia, dissemination to the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, kidneys, heart, liver, central nervous system and skin is common.25,26 Fusarium caused 22% of non-Aspergillus mold infections in the TRANSNET study of solid organ and stem cell transplant patients in the US, making it the most common mold in that patient population after Aspergillus and molds in the order Mucorales.27 The most common route of infection in the immunocompetent host is traumatic inoculation, especially in the presence of organic material. Airborne conidia, both inside and outside of the hospital setting, are likely the source of infection in immunocompromised patients, and conidia can become aerosolized through water systems such as sinks, showers and drains.28–30

The clinical manifestations of Fusarium infection cannot be distinguished from other common fungal infections such as Aspergillus. Sinusitis and pneumonia typically manifest the same as other fungal infections but are more likely to become invasive. However, unlike most other fungal infections, fusariosis often disseminates to the skin as painful red nodules that may ulcerate and develop into eschars, most commonly on the extremities. In a recent review of Fusarium infection, dissemination to the skin was present in 70% of the patients.31 There is no typical radiological pattern for fusariosis although the halo sign tends to be absent.32

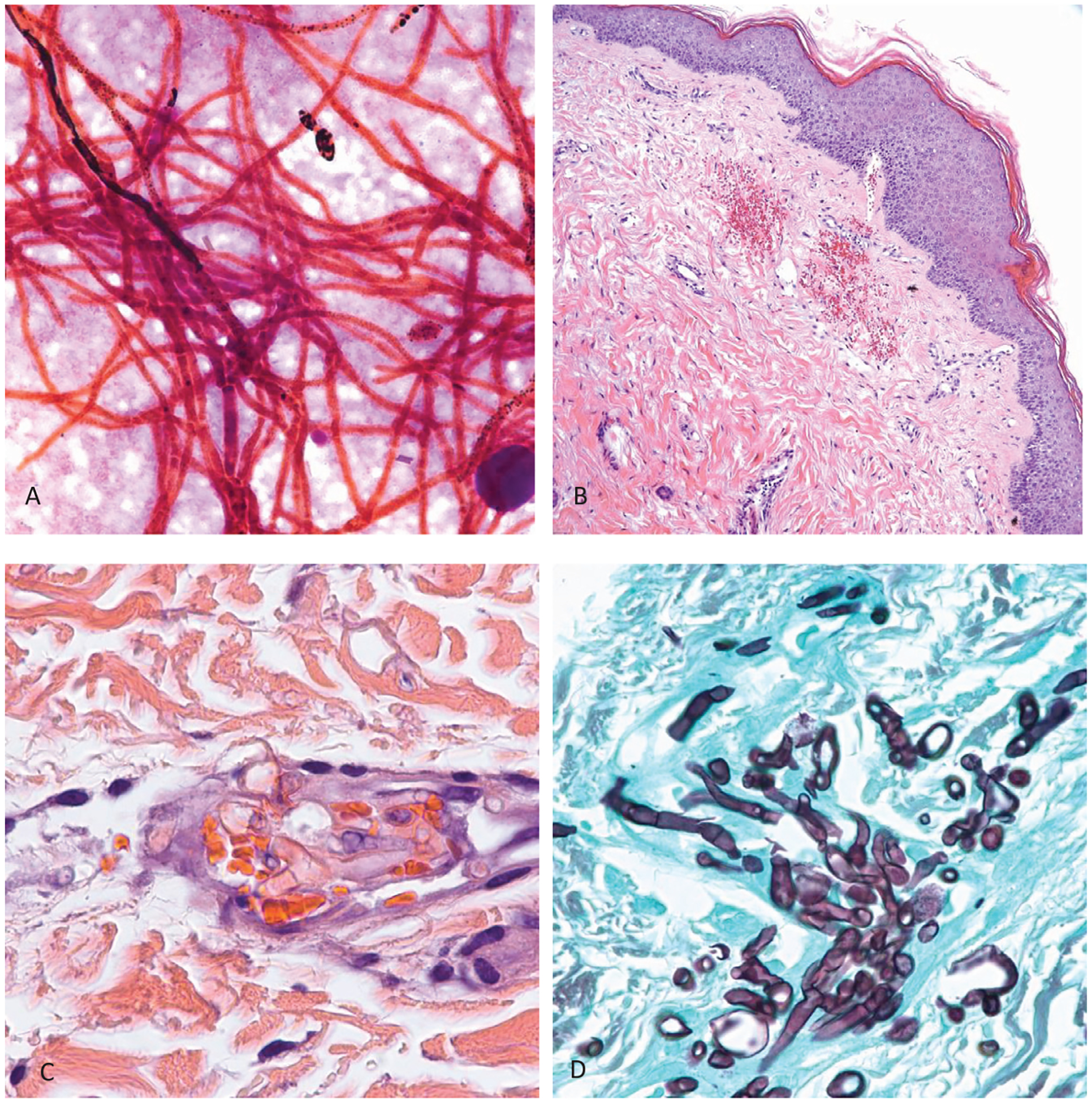

In tissue, Fusarium is seen as a hyaline, septated mold with acute to right angle branching similar to Aspergillus (Fig. 2). Thus, when pathologists see hyaline septated molds they should refrain from using the name of a species (Aspergillus, Fusarium or other) and rather describe the hyphae observed. In a comment they can name species that can produce similar morphologies: Aspergillus, Fusarium even Candida. Similar to the mucormycosis, Fusarium are angioinvasive and will cause thrombosis and necrosis of tissues. In vitro, but also sometimes in sinus or cavitary lesions, Fusarium reproduces asexually by producing 1–3 celled pyriform or fusiform microconidia as well as macroconidia with >2 cells that are banana-shaped or canoe-shaped. On most fungal media without cycloheximide it grows as a velvety to cottony colony that can be white, gray, lavender, purple, pink or salmon in color depending on the species. The most common species seen in clinical practice are members of the F. solani and F. oxysporum species complexes, but over 70 species have been isolated from human infections, some of which have not been named yet and are identified only by their DNA barcode.33–35

Fig. 2.

Case of disseminated fusariosis. A: Gram stain of blood culture showing abundant hyphae (original magnification 250×). B: Skin with petechial hemorrhages in the upper dermis (hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification 25×). C: Higher magnification (250×) of hematoxylin and eosin stain showing single hyaline hyphae with one septum inside a blood vessel in the upper dermis. D. Grocott methenamine silver stain highlighting abundant septated hyphae in the sinus debridement specimen from the same patient.

Definitive diagnosis generally relies on culture. Unlike most other filamentous fungi, Fusarium commonly grows in fungal blood culture.26 Culture can be derived from blood, BAL, sinus, or tissue. Skin biopsy is a very good source for culture.31 β-D-glucan is positive in cases of disseminated fusariosis but because this test is not specific for any particular fungus it is not useful for diagnosis.36 The galactomannan test, generally used to diagnose aspergillosis, cross-reacts with Fusarium.37 It is extremely difficult to identify Fusarium to species without the use of molecular tools. DNA sequencing is the best method for identification although MALDI-TOF may become an alternative in the future.38,39 Most isolates of Fusarium are placed in species complexes which is acceptable in clinical practice.33,40

Fusarium can be highly antifungal resistant and the resistance pattern varies from species to species, even within a species complex.41 Posaconazole and/or amphotericin B are the usual treatment although some isolates may respond to voriconazole.26 Surgical debridement is essential for the prevention of progression. Due to the underlying immune status of the susceptible population, even with antifungal treatment mortality is high.26

Candida auris

The previous two fungi, Histoplasma and Fusarium, are described as reemerging because both have been recognized by clinicians for a long time and may be increasing in prevalence due to a change in the susceptible population. However, there is one fungus that was previously unknown to clinical practice just a decade ago and is truly emerging; C. auris. This yeast was first described in 2009 from a single isolate recovered from the ear discharge of a patient in Japan.42 Since that time it has been identified around the world as a pathogen causing primarily bloodstream infections, but also, wound, urinary tract, and other infections.43 A recent look-back at multiple international culture collections confirmed that the emergence of C. auris is recent with only a couple isolates identified before 2011.44

The most common manifestation of C. auris infection is candidemia. There have also been infections of the central nervous system, respiratory tract, urogenital tract, abdomen, bone, and skin and soft tissue.45 In a review of 31 candidemia cases from New York the 30 day mortality was 39% and the 90 day mortality was 58%.46 Patients can also become colonized with C. auris in the axilla, groin, nares, ear and rectum. While colonization does not pose an immediate threat to the patient, colonized patients can subsequently become infected and they also pose a serious risk for colonization of other patients if infection control practices are not initiated in the hospital. At this time there is no known protocol for decolonization.46–48

It has also been shown through whole genome sequencing that four distinct clonal populations (clades) emerged simultaneously on three continents, South America, Asia and Africa, and these four clades have been responsible for further spread around the world. Despite being unknown only a decade ago, C. auris is now causing large healthcare-associated outbreaks all over the world, which is unusual for any Candida species.44,46,47,49,50 One of the unique aspects of C. auris epidemiology is that when it is introduced into a healthcare setting it has the ability to spread clonally from patient to patient as both a pathogen and a colonizer.46,48,51

C. auris is an ellipsoid to elongate ascomycete budding yeast that is 2–5 μm in size. It can grow at temperatures up to 42 °C and can survive in high salt environments (up to 10% NaCl).52 It generally grows singly or in pairs but it is able to form aggregates in liquid culture and there is evidence that it can form hyphae following passage through an animal host.53,54 Based on its own growth pattern and that of other Candida spp., it is likely that C. auris will appear in tissue sections as yeasts with rare hyaline hyphae.

Diagnosis of C. auris is the same as for other Candida species. It grows well in blood culture and from other specimens such as urine or wound exudates. There are extenuating factors that make identification difficult. Because it is a newly identified species, C. auris is not in the database of many conventional yeast identification systems, and biochemically it is very closely related to two other Candida species, C. haemulonii and C. duobushaemulonii which hinders distinguishing between the three species. C. auris can be accurately identified by DNA sequencing or by MALDI-TOF, provided it is in the database being used.55

Unlike most other Candida species, C. auris can acquire resistance to the three commonly used classes of antifungals; azoles, echinocandins and polyenes.44,56 Antifungal resistance is dependent upon the particular clone but approximately 70% of over 900 isolates in the CDC collection are resistant to at least one antifungal, 25% are resistant to at least two antifungals and 1% are resistant to all three available classes of antifungal, making those isolates essentially untreatable (CDC, unpublished data). Resistance to fluconazole is most common (almost 100% in isolates from South Asia), followed by resistance to amphotericin B (25% of isolates from South Asia), and resistance to echinocandins (5% of all isolates with no clonal association).44,46,56

The recommended treatment for C. auris is an echinocandin, which follows the Infectious Disease Society of America’s recommendations for the treatment of candidemia.57 Susceptibility testing should be performed on all isolates and therapy can be stepped down to an azole or up to amphotericin B if the isolate tests susceptible. Because of the high proportion of antifungal resistance for C. auris isolates, patients should be monitored closely for treatment failure no matter which antifungal is given.

When an isolate of C. auris is identified, the CDC recommends that strict infection control guidelines be followed (https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/candida-auris/c-auris-infection-control.html). This includes patient isolation and contact precautions. Cleaning and disinfecting the patient care environment is important as C. auris has been shown to contaminate patient rooms.46,47,58 Chlorine-based products are the most effective but other products are also effective. Products from List K published by the US Environmental Protection Agency are recommended (https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-registration/list-k-epas-registered-antimicrobial-products-effective-against-clostridium).

Conclusion

Although they may cause significant morbidity and mortality in susceptible populations, fungi can be overlooked as a cause of emerging infection. Surgeons may remove tissue or perform a biopsy on what is thought to be a malignant mass only to find out after it has been placed in formalin that it is a fungal mass.59,60 While only three specific fungi were discussed above, the overall number of fungal infections is increasing as the susceptible population expands. It is prudent for pathologists to keep fungi in mind as a cause of masses, swellings, and infiltrates as they receive frozen sections so that material is sent for microbiological culture. Pathologists should also be cognizant of the pitfalls of diagnosing fungal structures (hyphae or yeasts) in different specimens by species. With the increased armamentarium of antifungal agents, pathologists need to be aware that their descriptive diagnosis of yeast and hyphae will have significant impact to patient care.

References

- 1.Richardson M, Lass-Florl C. Changing epidemiology of systemic fungal infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14(Suppl 4):5–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niederwieser D, Baldomero H, Szer J, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation activity worldwide in 2012 and a SWOT analysis of the Worldwide Network for Blood and Marrow Transplantation Group including the global survey. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016;51:778–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biologic drugs set to top 2012 sales. Nature medicineNat Med. 2012;18:636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wheat LJ, Azar MM, Bahr NC, Spec A, Relich RF, Hage C. Histoplasmosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:207–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bahr NC, Antinori S, Wheat LJ, Sarosi GA. Histoplasmosis infections worldwide: thinking outside of the Ohio River valley. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2015;2:70–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benedict K, Derado G, Mody RK. Histoplasmosis-associated hospitalizations in the United States, 2001–2012. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3:ofv219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adenis AA, Valdes A, Cropet C, et al. Burden of HIV-associated histoplasmosis compared with tuberculosis in Latin America: a modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:1150–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adenis A, Nacher M, Hanf M, et al. Tuberculosis and histoplasmosis among human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients: a comparative study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;90:216–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kauffman CA. Histoplasmosis: a clinical and laboratory update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:115–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Assi MA, Sandid MS, Baddour LM, Roberts GD, Walker RC. Systemic histoplasmosis: a 15-year retrospective institutional review of 111 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007;86:162–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orlowski HLP, McWilliams S, Mellnick VM, et al. Imaging spectrum of invasive fungal and fungal-like infections. Radiographics. 2017;37:1119–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiley Z, Woodworth MH, Jacob JT, et al. Diagnostic importance of hyphae on heart valve tissue in histoplasma endocarditis and treatment with isavuconazole. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:ofx241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hage CA, Ribes JA, Wengenack NL, et al. A multicenter evaluation of tests for diagnosis of histoplasmosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:448–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Theel ES, Harring JA, Dababneh AS, Rollins LO, Bestrom JE, Jespersen DJ. Reevaluation of commercial reagents for detection of Histoplasma capsulatum antigen in urine. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:1198–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fandino-Devia E, Rodriguez-Echeverri C, Cardona-Arias J, Gonzalez A. Antigen detection in the diagnosis of histoplasmosis: a meta-analysis of diagnostic performance. Mycopathologia. 2016;181:197–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caceres DH, Samayoa BE, Medina NG, et al. Multicenter validation of commercial antigenuria reagents to diagnose progressive disseminated histoplasmosis in people living with HIV/AIDS in two Latin American countries. J Clin Microbiol. 2018:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Libert D, Procop GW, Ansari MQ. Histoplasma urinary antigen testing obviates the need for coincident serum antigen testing. Am J Clin Pathol. 2018;149:362–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wheat LJ. Histoplasmosis in Indianapolis. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14(Suppl 1):S91–S99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richer SM, Smedema ML, Durkin MM, et al. Improved diagnosis of acute pulmonary histoplasmosis by combining antigen and antibody detection. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:896–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buitrago MJ, Canteros CE, Frias De Leon G, et al. Comparison of PCR protocols for detecting Histoplasma capsulatum DNA through a multicenter study. Revista iberoamericana de micologia. 2013;30:256–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sampaio Ide L, Freire AK, Ogusko MM, Salem JI, De Souza JV. Selection and optimization of PCR-based methods for the detection of Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum. Revista iberoamericana de micologia. 2012;29:34–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stockman L, Clark KA, Hunt JM, Roberts GD. Evaluation of commercially available acridinium ester-labeled chemiluminescent DNA probes for culture identification of Blastomyces dermatitidis, Coccidioides immitis, Cryptococcus neoformans, and Histoplasma capsulatum. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:845–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wheat LJ, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:807–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mikami R, Stemmermann GN. Keratomycosis caused by Fusarium oxysporum. Am J Clin Pathol. 1958;29:257–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nucci F, Nouer SA, Capone D, Anaissie E, Nucci M. Fusariosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36:706–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muhammed M, Anagnostou T, Desalermos A, et al. Fusarium infection: report of 26 cases and review of 97 cases from the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2013;92:305–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park BJ, Pappas PG, Wannemuehler KA, et al. Invasive non-Aspergillus mold infections in transplant recipients, United States, 2001–2006. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1855–1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moretti ML, Busso-Lopes A, Moraes R, et al. Environment as a potential source of fusarium spp. invasive infections in immunocompromised patients. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2014;1:S38 S38. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anaissie EJ, Kuchar RT, Rex JH, et al. Fusariosis associated with pathogenic fusarium species colonization of a hospital water system: a new paradigm for the epidemiology of opportunistic mold infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1871–1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raad I, Tarrand J, Hanna H, et al. Epidemiology, molecular mycology, and environmental sources of Fusarium infection in patients with cancer. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2002;23:532–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nucci M, Anaissie E. Cutaneous infection by Fusarium species in healthy and immunocompromised hosts: implications for diagnosis and management. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:909–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marom EM, Holmes AM, Bruzzi JF, Truong MT, O’Sullivan PJ, Kontoyiannis DP. Imaging of pulmonary fusariosis in patients with hematologic malignancies. AJR. 2008;190:1605–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al-Hatmi AM, Van Den Ende AH, Stielow JB, et al. Evaluation of two novel barcodes for species recognition of opportunistic pathogens in Fusarium. Fungal Biol. 2016;120:231–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guarro J Fusariosis, a complex infection caused by a high diversity of fungal species refractory to treatment. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;32:1491–1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Al-Hatmi AM, Hagen F, Menken SB, Meis JF, de Hoog GS. Global molecular epidemiology and genetic diversity of Fusarium, a significant emerging group of human opportunists from 1958 to 2015. Emerg Microbes Iinfect. 2016;5:e124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Alexander BD, Kett DH, et al. Multicenter clinical evaluation of the (1–>3) beta-d-glucan assay as an aid to diagnosis of fungal infections in humans. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:654–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tortorano AM, Esposto MC, Prigitano A, et al. Cross-reactivity of Fusarium spp. in the Aspergillus Galactomannan enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:1051–1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Triest D, Stubbe D, De Cremer K, et al. Use of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry for identification of molds of the Fusarium genus. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:465–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balajee SA, Borman AM, Brandt ME, et al. Sequence-based identification of Aspergillus, fusarium, and mucorales species in the clinical mycology laboratory: where are we and where should we go from here. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:877–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Donnell K, Rooney AP, Proctor RH, et al. Phylogenetic analyses of RPB1 and RPB2 support a middle Cretaceous origin for a clade comprising all agriculturally and medically important fusaria. Fungal Genet Biol. 2013;52:20–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Al-Hatmi AM, Meis JF, de Hoog GS. Fusarium: molecular diversity and intrinsic drug resistance. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Satoh K, Makimura K, Hasumi Y, Nishiyama Y, Uchida K, Yamaguchi H. Candida auris sp. nov., a novel ascomycetous yeast isolated from the external ear canal of an inpatient in a Japanese hospital. Microbiol Immunol. 2009;53:41–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chowdhary A, Sharma C, Meis JF. Candida auris: a rapidly emerging cause of hospital-acquired multidrug-resistant fungal infections globally. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lockhart SR, Etienne KA, Vallabhaneni S, et al. Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:134–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jeffery-Smith A, Taori SK, Schelenz S, et al. Candida auris: a review of the literature. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2018:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adams E, Quinn M, Tsay S, et al. Candida auris in healthcare facilities, New York, USA, 2013–2017. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:1816–1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schelenz S, Hagen F, Rhodes JL, et al. First hospital outbreak of the globally emerging Candida auris in a European hospital. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2016;5:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsay S, Kallen A, Jackson BR, Chiller TM, Vallabhaneni S. Approach to the investigation and management of patients with Candida auris, an emerging multidrug-resistant yeast. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:306–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Calvo B, Melo AS, Perozo-Mena A, et al. First report of Candida auris in America: clinical and microbiological aspects of 18 episodes of candidemia. J Infect. 2016;73:369–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chowdhary A, Sharma C, Duggal S, et al. New clonal strain of Candida auris, Delhi, India. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:1670–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tsay S, Welsh RM, Adams EH, et al. Notes from the field: ongoing transmission of Candida auris in health care facilities - United States, June 2016–May 2017. MMWR. 2017;66:514–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Welsh RM, Bentz ML, Shams A, et al. Survival, persistence, and isolation of the emerging multidrug-resistant pathogenic yeast Candida auris on a plastic health care surface. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55:2996–3005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Borman AM, Szekely A, Johnson EM. Comparative pathogenicity of United Kingdom isolates of the emerging pathogen Candida auris and other key pathogenic Candida species. mSphere. 2016:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yue H, Bing J, Zheng Q, et al. Filamentation in Candida auris, an emerging fungal pathogen of humans: passage through the mammalian body induces a heritable phenotypic switch. Emerg Microb Infect. 2018;7:188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mizusawa M, Miller H, Green R, et al. Can multidrug-resistant Candida auris be reliably identified in clinical microbiology laboratories. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55:638–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chowdhary A, Anil Kumar V, Sharma C, et al. Multidrug-resistant endemic clonal strain of Candida auris in India. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33:919–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:e1–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Escandon P, Chow NA, Caceres DH, et al. Molecular epidemiology of Candida auris in Colombia Reveals a highly related, countrywide colonization with regional patterns in Amphotericin B resistance. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gazzoni FF, Severo LC, Marchiori E, et al. Fungal diseases mimicking primary lung cancer: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Mycoses. 2014;57:197–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schweigert M, Dubecz A, Beron M, Ofner D, Stein HJ. Pulmonary infections imitating lung cancer: clinical presentation and therapeutical approach. Ir J Med Sci. 2013;182:73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]