Abstract

Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), a cytokine with near omnipresence, is an integral part of many vital cellular processes across the human body. The family includes three isoforms: Transforming growth factor-beta 1, 2, and 3. These cytokines play a significant role in the fibrosis cascade. Diabetic kidney disease (DKD), a major complication of diabetes, is increasing in prevalence daily, and the classical diagnosis of diabetes is based on the presence of albuminuria. The occurrence of nonalbuminuric DKD has provided new insight into the pathogenesis of this disease. The emphasis on multifactorial pathways involved in developing DKD has highlighted some markers associated with tissue fibrosis. In diabetic nephropathy, TGF-β is significantly involved in its pathology. Its presence in serum and urine means that it could be a diagnostic tool while its regulation provides potential therapeutic targets. Completely blocking TGF-β signaling could reach untargeted regions and cause unanticipated effects. This paper reviews the basic details of TGF-β as a cytokine, its role in DKD, and updates on research carried out to validate its candidacy.

Keywords: Cytokine, diabetic kidney disease, fibrosis, transforming growth factor-beta

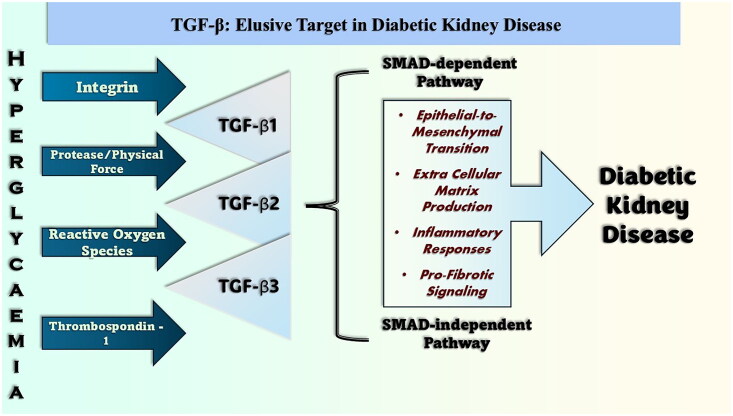

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is a significant global concern, impacting nearly 700 million individuals across the globe [1]. A lot of the time, this major problem is caused by having blood sugar that is too high for a long time. Hyperglycemia alters metabolic pathways, specifically affecting the breakdown of sugars, resulting in the production of detrimental molecules that can cause damage to cells [2].

High blood sugar damages kidney cells with advanced glycation end products (AGEs). Moreover, triggering the protein kinase C (PKC) signaling pathway aggravates cellular malfunction. These AGEs can narrow blood vessels, therefore lowering renal blood flow. Additionally, hyperglycemia can change hemodynamics by activating PKC. Finally, hyperglycemia induces inflammation in the kidney. This process produces reactive oxygen species (ROS) and free radicals that damage cells and aggravate disease [3–7].

Noninvasive urine and blood tests are the gold standard diagnostic tests for DKD. These tests measure the urine and serum creatinine levels. Furthermore, the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was calculated using the modification of diet in renal disease (MDRD) study equation and the creatinine equation of the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) [2,8,9].

However, a new branch has emerged from the existing DKD known as nonalbuminuric or normoalbuminuric DKD (NADKD). In these cases, patients do not show the classic symptoms of proteinuria until the later stages. Thus, there is a need for comprehensive assessments, including diabetes confirmation, kidney function tests, and potentially specific kidney damage markers [10,11]. Around half of the DKD population has been found to be nonalbuminuric [12,13]. Even though the pathogenesis has not been fully understood, a complex and eclectic flux is expected which is expected to include, age, atherosclerosis, cholesterol micro emboli, dyslipidemia, fibrosis, hypertension, inflammation, lipid toxicity, obesity, masking of albuminuria by renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors [14,15]. For multiple reasons, several novel markers are being investigated for their diagnostic and/or therapeutic potential.

Although there are many different pathways involved, many of them eventually lead to fibrosis of the kidneys. Active fibroblasts respond to injury by producing a large amount of extracellular matrix (ECM), which aids in wound healing. Extracellular matrix accumulation caused by recurrent injuries results from extended wound healing. This accumulation cannot be resolved by the body’s tissue rebuilding mechanisms; hence, organs scar. This fact is valuable enough to stimulate the search for fibrotic markers [16].

Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), a cytokine family with three isoforms, is essential for processes such as growth, cell differentiation, and apoptosis. Found in the late 1970s, these signaling molecules are produced by numerous cells and influence organismal homeostasis, repair, and development. Although TGF-β is rather common, it has been linked to various medical conditions, including cancer, fibrosis, and birth defects [17].

Research on the TGF-β’s involvement in DKD pathogenesis.is needed. Fibrosis, a common marker of DKD, is connected to TGF-β. Because of the presence of too much connective tissue, fibrosis results in organ scarring and loss of function. In DKD, TGF-β is supposed to boost kidney cell production of ECM proteins, which build connective tissue. Fibrosis and kidney failure result from overproduction. Directly targeting TGF-β in past studies on treating DKD has produced conflicting results. The difficulty is the complicated nature of TGF-β signaling. In addition to aggravating fibrosis in DKD, TGF-β is essential for several physiological functions. Completely blocking TGF-β signaling could have unanticipated effects [18–23].

1.1. History and discovery

TGF-β was first identified in 1978 by De Larco and Todaro as a ‘sarcoma growth factor’ that is produced by transformed murine fibroblasts. These factors were also able to convert normal fibroblasts to anchorage-independent colonies. In the 1980s, National Cancer Institute (NCI) investigators, headed by Michael Sporn and Anita B. Roberts, discovered the presence of TGF-β in cancer cells and demonstrated its ability to transform healthy cells into malignant cells. Shortly thereafter, they unexpectedly made a find. It was discovered that noncancerous cells also produce tumor-promoting factors [24].

2. Structure

The TGFβ family ligands are composed of a N-terminal signal peptide, a large prodomain (PD), and a C-terminal mature growth factor (GF). These polypeptides typically form dimers (homodimers or heterodimers) in the endoplasmic reticulum. The signal peptides are cleaved, and the dimerized GFs are also cleaved from the PDs, but the PDs remain noncovalently associated with their cognate GFs. The PD–GF complex, which may covalently associate with a latent TGF-β-binding protein (LTBP), is secreted into the ECM. Some TGFβ family proteins, like BMP4, BMP5, BMP7, and BMP9, are active in their PD-bound form, while others, such as MSTN/myostatin (GDF8) and GDF11, require the removal of PDs to bind to receptors [4]. This structure allows for diverse and regulated signaling mechanisms [25].

2.1. Isoforms of TGF-β

There are five isoforms of TGF beta, but only three are found in mammals, and all of them produce the same effects in vitro. In mammals, three separate genes produce the three closely linked isoforms TGF-β-1, -2, and -3. The remaining C-terminal region forms a 24-kDa homodimer to generate the three TGF-β isoforms, which are processed and secreted similarly in that intracellular proteolysis cleaves the N-terminal region to form an approximately 75-kDa homodimer called the latency-associated peptide (LAP) [26].

2.1.1. TGF-β1

TGF-β1 is produced by all cells of the renal epithelium and interstitium, including inflammatory cells. Immunity, cell differentiation, and development all require this protein. Nevertheless, in DKD, constantly high blood glucose levels activate TGF-β1, which causes excessive accumulation of scar tissue and kidney damage. While animal studies have shown that blocking activated TGF-β1 can reduce scarring, clinical studies have not shown favorable findings, most likely because of its concurrent reduction in beneficial functions. Researchers are looking at ways to especially target the negative aspects of TGF-β1 signaling or completely stop its activity. The development of effective treatments for DKD depends on thorough knowledge of the several routes by which TGF-β1 is regulated. Finding a way to minimize the negative effects of TGF-β1 while preserving its benefits will help us to provide a fresh way of treating DKD [27].

2.1.2. TGF-β2

In several biological processes, TGF-β2 regulates cell growth, differentiation, and development. TGF-β2 has many physiological effects on different organs. Its functions include tissue homeostasis, immunomodulation, wound healing, and embryonic development. TGF-β has two unique functions in the process of repair since it shows unique spatial and temporal expression patterns during the healing of skin lesions. It is yet unknown exactly how TGF-β2 causes scarring. While some studies speculate that TGF-β2 may contribute to scarring, others point to different effects [28].

2.1.3. TGF-β3

The protein β3 (TGFβ-3) is essential for many different biological activities. TGFβ-3 is involved in cell differentiation, embryogenesis, development, motility, and controlled death. It regulates the molecules involved in ECM synthesis and cellular adhesion development during palate development. By controlling the movements of epidermal and dermal cells in injured skin, this protein also plays a vital role in controlling lung development and supervising the process of wound healing. The control of cell growth and division can stop rapid or uncontrolled proliferation, thus stopping the development of tumors. TGF-β3 is fundamental for the development of tissues that undergo differentiation into skeletal muscles. It also affects the formation of blood vessels, the regulation of bone development, wound healing, and immune system operation. Both immediate and long-lasting scarless healing and a reduction in scarring are well-known properties of TGFβ-3. It also inhibits fibrosis during the process of wound healing. These phenomena are most often observed in the first phases of wound recovery, specifically in the moving outer layer of skin, and may impede the proliferation of keratinocytes without affecting the process of re-epithelialization [28].

3. Biosynthesis of latent forms

TGF-β1 transforms in vitro from a noncovalent to an active 25 kDa form under acidic conditions. There are three kinds of latent TGF-β1: α2-macroglobulin, small, and large. Moreover, the 25 kDa TGF-β isoform is bound by many soluble proteins. Pro-TGF-β1 is 361 amino acids long and is formed via post peptide signal cleavage [29].

TGF-β synthesis is regulated by a complicated mechanism that also determines its levels. Transcription in the cell nucleus is mediated by the TGF-β gene. From mRNA, cytoplasmic ribosomes translate the protein pre-pro-TGF-β. An endoplasmic reticulum-cleaved (ER-cleaved) signal peptide quickly draws on this precursor. A homodimer is formed in the ER via disulfide bonds between two pro-TGF-β monomers. Monomers of pro-TGF-β bind noncovalently to a protein fragment produced from precursors called LAP. TGF-β creates the dormant small latent complex (SLC). Cleavage of pro-TGF-β by the furin enzyme significantly modifies SLC. Although TGF-β requires cleavage to become active, its activation is delayed by its association with LAP partners. Recently, TGF-β-binding proteins are added late in biosynthesis. When LTBPs form -1, -3, or -4 covalent disulfide bonds with SLC LAP, large latent complex (LLC) formation occurs. The cell releases a mature TGF-β, LAP, and LTBP complex. LTBP of the LLC attachment matrix. The latent TGF-β complex is maintained in the reservoir until activation mechanisms are triggered. Fascinatingly, biological inactivity or delay is caused by interactions between the TGF-β dimer and LAP and LTBP. This complex packing mechanism precisely regulates the strong signaling properties of TGF-β [30–33].

4. TGF-β signaling

TGF-β pathway signaling depends on mothers suppressing decapentaplegic (SMAD) protein. Dysregulation of TGF-β/SMAD signaling has an impact on various disorders, including cancer, fibrosis, aberrant development, and CKD. In several diseases, SMADs control inflammation, fibrosis, and tissue repair. Renal fibrosis in CKD does not occur without overactivation of the TGF-β/SMAD pathway [20].

4.1. SMAD-dependent pathway

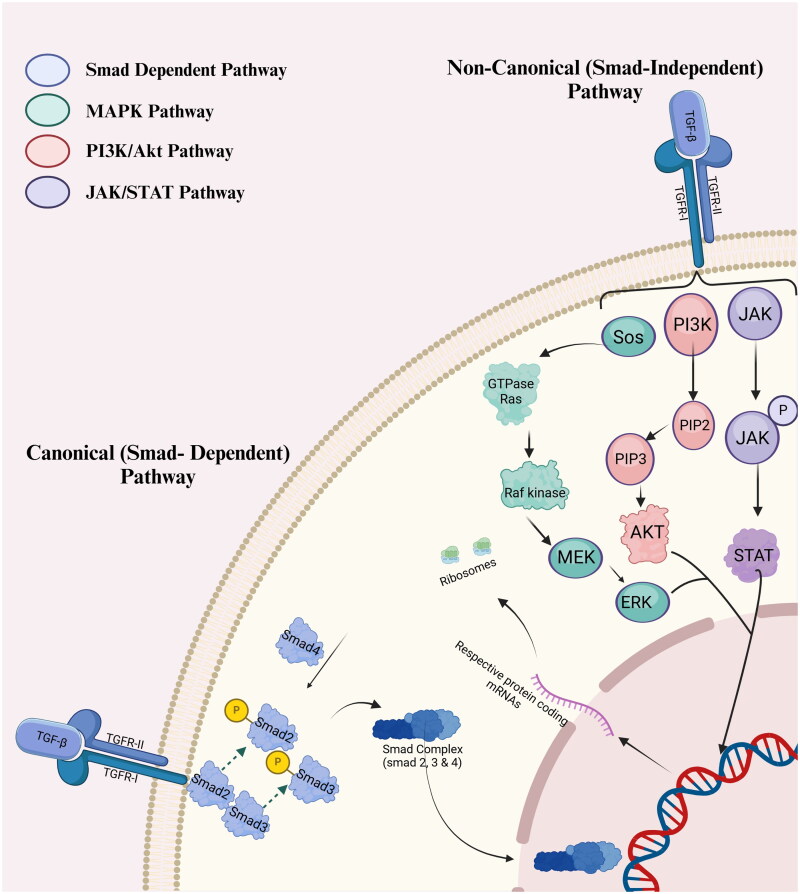

In the SMAD-dependent pathway, TGF-β signals are transferred from the cell membrane to the nucleus, resulting in different cellular reactions depending on the SMAD pathway. Ligand binding to heteromeric complexes, including type I (TβRI) and type II (TβRII) receptors, initiates the TGF-β signaling cascade. TβRII activates TβRI after ligand interaction, and TβRI phosphorylates receptor-regulated SMADs (R-SMADs), primarily SMAD2 and SMAD3. This pathway is triggered by the phosphorylation of R-SMAD at serine residues of the C-terminal SSXS motif. Translocating into the nucleus, phosphorylated R-SMADs and the common mediator SMAD (Co-SMAD)4, the shared mediator SMADs, create heterotrimeric complexes. Nuclear localization signals of SMAD proteins enhance nuclear translocation and Smad binding element (SBE) interactions with target gene promoters. Target gene transcription is controlled by SMAD complexes in the nucleus, which may directly bind to SBEs or interact with other transcription factors and cofactors. By means of transcriptional regulation, the environment and co-factors can either activate or suppress gene expression. Moreover, SMAD controls ECM synthesis, cell proliferation, differentiation, death, genes, and the cytoplasm [34–39] as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Smad dependent/independent pathways used by TGF-β for signaling.

4.2. SMAD-independent pathway

Unlike the traditional SMAD-dependent pathway, another SMAD-independent pathway delivers TGF-β signals into cells as illustrated in Figure 1. c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK). The AK strain activated both the AKT/PI3K and p38 MAPK signaling pathways and activated both the AKT/PI3K and p38 MAPK signaling pathways. MAPKs are phosphorylated and activated downstream effectors to control cellular responses when TGF-β is activated. Survival, proliferation, and migration are linked to ERK; cell proliferation, differentiation, death, and inflammation are linked to p38 MAPK and JNK. AKT/PI3K controls cell metabolism, survival, and growth. Non-SMAD pathways that combine various inputs and modify cellular responses in a context-dependent manner form the TGF-β signaling complex. TGF-β receptors must interact with and turn on downstream kinases and adaptors to activate SMAD-independent signaling molecules. In several cell processes, target proteins are phosphorylated when TGF-β activates p38 MAPK and JNK through mitogen-activated protein kinase 3/6 (MKK3/6) and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4 (MKK4 MAP) kinases. TGF-β is flexible and adaptable; it activates MAPK pathways even in the absence of SMAD proteins. TGF-β signaling is better regulated, and cells perform better when SMAD-independent pathways are linked to other signaling cascades, such as the NF-κB and Rho GTPases [40–45].

5. TGF-β activation

TGF-β activation is a crucial step in its functional regulation within the immune system. TGF-β is initially produced as a complex with inactive activity and must be activated to exert its biological effects. There are several mechanisms involved in the activation of latent TGF-β:

5.1. Physical force/protease-mediated activation

Latent transformation growth factor-β, a potent cytokine. Its biological activities are hidden by proteins such as LAP, which results in inactivity. TGF-β released from the cytoskeleton by actin filament contractions can trigger powerful signaling cascades. Actin contraction and TGF-β activation are related to complicated mechanisms, including cell biochemical signals and mechanical forces. Actin can activate proteases, which in turn activate TGF-β. Proteases shatter peptide bonds. Actin filament contraction sets off proteases that target the dormant TGF-β complex. By precisely cutting LAP and binding proteins, proteases release active TGF-β. The stiffness of the cell can also affect TGF-β activation. The increased stiffness caused by rearranging the actin network of the cell increases the mechanical pressure on the latent TGF-β complex. Increasing strain causes TGF-β to become activated. The important effects of TGF-β activation mediated by actin exist. When a wound heals, TGF-β release and regulated cell contraction are essential for tissue regeneration. Dysregulation of this process can lead to pathological fibrosis, which can result in excessive scar tissue and organ dysfunction [46].

5.2. Reactive oxygen species activation

For many physiological and pathological processes, the complex interaction between ROS and TGF-β is essential. ROS, which are composed of chemically ROS, are double weapons in biological systems. Oxidative stress and damage are caused by high ROS levels, whereas cellular signaling requires moderate amounts of ROS. By means of intricate chemical processes, ROS cause TGF-β expression. Importantly, the amino acid residues of the LAPs of the latent TGF-β complex are directly oxidized. When methionine residues are attacked, ROS hydroxyl radicals change the structure and produce bioactive TGF-β. Because ROS activate proteases, they can interfere with TGF-β complex interactions. TGF-β is released when proteases breakdown LAP and other binding proteins. TGF-β complex activation is triggered by ROS, increasing thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) synthesis and activity. TGF-β activation driven by ROS is essential for tissue repair and wound healing. Increased ROS levels at the wound site following tissue damage trigger TGF-β. Through its stimulation of cell migration, collagen deposition, and blood vessel development, TGF-β promotes tissue repair. However, there must be careful balance. Pathological fibrosis can result from TGF-β overactivation caused by chronically elevated ROS concentrations. The scarring of the kidneys, lungs, and liver can be severe when the ECM is overproduced [47,48].

5.3. Thrombospondin-1 binding

By binding to its LAP and severing its connection with the active cytokine, the ECM protein thrombospondin activates TGF-β. Latent TGF-β is activated by the ECM protein TSP-1. At first inactive, TGF-β needs special activation pathways to produce a variety of biological consequences. TSP-1 directly binds to TSP-1 for this process. The LAP of the latent TGF-β complex has a complementary sequence, leucine–serine–lysine–leucine (LSKL), which is bound to a particular amino acid sequence in TSP-1. This contact causes the latent TGF-β complex to shift conformationally, therefore, changing its shape and destabilizing its structure. TGF-β, which is active, is released, and its signaling ability is increased [49–51].

5.4. Integrin-mediated activation

Once associated with cell attachment to the ECM, integrin transmembrane receptors regulate physiological responses. TGF-β complexes, which are essential signaling molecules in many biological processes, are triggered by the integrins αvβ6 and αvβ8. Because active TGF-β is delivered through paracrine signaling, the latent complex must be activated by direct cell-to-cell interactions with αvβ6 integrin. A specific carboxyl-terminal region in the β6 subunit of αvβ6 integrin is necessary for active TGFβ. When these residues are altered or deleted, cancer cells cannot invade. TGFβ activation by αvβ6 is protease inhibitor-resistant and distinct from cytoplasmic domain activation by β6. Conversely, membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) and other metalloproteases are used by αvβ8 integrin to activate latent TGF-β complexes and release active TGF-β into the extracellular milieu. The fact that metalloprotease inhibitors can suppress TGF-β activation via αvβ8 points to a distinct mechanism. A distinct activation mechanism from that of αvβ6 is suggested by the lack of the β8 cytoplasmic region in αvβ8-mediated TGF-β stimulation. In both healthy and sick states, integrins are essential for TGF-β activation. Controlling fibrotic responses in tissue fibrosis depends critically on the integrins αvβ6 and αvβ8. Therapy targets for diseases involving aberrant TGF-β activity include integrins, which impact TGF-β signaling pathways. Complex relationships between integrins and signaling pathways are shown by integrin-mediated TGF-β activation. Although αvβ6 integrin activates TGF-β via cell contact, αvβ8 integrin releases active TGF-β via proteolysis catalyzed by a metalloprotease. Integrins αvβ6 and αvβ8 show their adaptability in changing TGF-β signaling by diverse architectures and activation strategies [52–54].

6. Downstream effects

TGF-β is an integral molecule of the organismal organization. This molecule is involved in embryonic development, wound healing, tissue homeostasis, and immune cells’ homeostasis in a healthy environment [55,56].

6.1. Wound healing

Wound healing depends critically on TGF-β, which also directs a set of mechanisms guaranteeing appropriate tissue restoration [57]. Combining inflammation, cell proliferation, ECM formation, angiogenesis, and tissue remodeling, wound healing is a complicated and well-coordinated process. Utilizing its regulating activities on different cells and GFs, TGF-β shapes every one of these phases [55,58,59].

6.1.1. Inflammation and immune response

Beginning in an inflammatory phase, wound healing depends on TGF-β in attracting immune cells to the damaged site and controlling their activity. After an injury, TGF-β is released from other cells in the wound region, including platelets. It functions as a chemoattractant for macrophages, neutrophils, and fibroblasts. Particularly helping macrophages to activate and migrate, TGF-β helps to coordinate the inflammatory response. Employing phagocytosis, macrophages eliminate dead cells, waste products, and infections. Furthermore, they generate cytokines that intensify the inflammatory reaction and activate other immune cells to create a protective surrounding against infection. TGF-β actively changes immune cell behavior, therefore, transcending simple immune cell recruitment. Once macrophages reach the wound site, TGF-β, for instance, causes them to generate extra cytokines and GFs like interleukin-1 (IL-1), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). This generates a positive feedback loop that maintains inflammation when needed and stimulates fibroblast and endothelial cell activity, facilitating the transition to the proliferative phase [60,61].

6.1.2. Fibroblast activation

Key cells in the synthesis of the ECM, which offers the required scaffold for tissue regeneration, are fibroblasts. After damage, TGF-β functions as a strong fibroblast activator. Fibroblasts migrate into the wound area, multiply, and develop into myofibroblasts – a specialized cell type essential for wound contraction – in response to TGF-β signaling. Alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) expressed by myofibroblasts enables them to produce contraction forces, helping to seal the wound. The function of TGF-β in fibroblast activation also entails encouraging their continuous presence and activity in the wound bed. It preserves the active state by autocrine signaling and causes the fibroblasts to produce more TGF-β. Strong contribution of fibroblasts to the deposition of ECM components like collagen, elastin, and fibronectin results from this continuous stimulation [62–64].

6.1.3. Extracellular matrix synthesis and remodeling

TGF-β controls the output of ECM in several ways. Through interactions with collagen and fibronectin, TGF-β increases ECM protein gene transcription in active fibroblasts. This is accomplished by overexpression of mRNAs linked to ECM, which generate more proteins. Utilizing nuclear factors such as nuclear factor-1, TGF-β stimulates collagen gene transcription, thereby generating more structural protein synthesis for strength and wound stability. Apart from driving ECM production, TGF-β controls ECM remodeling. Boosting fibroblast integrins and membrane receptors enhances cell–ECM interactions and wound site fibroblast mobility and function. Targeting ECM breakdown and boosting tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) production, TGF-β lowers MMP activity. This combination activity encourages early healing tissue generation and helps to prevent early ECM breakdown. During healing, ECM transforms tissue. By guaranteeing appropriate matrix design and lowering excess deposition, TGF-β balances ECM synthesis and breakdown, preventing fibrosis and scar tissue. To provide immediate structural support and long-term tissue integrity for efficient wound healing, TGF-β regulates ECM synthesis and remodeling [65].

6.2. Tissue homeostasis

TGF-β stops the cell cycle at the G1 phase, restricting cell proliferation. Key control of cell cycle progression, cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), is inhibited here, hence mediating this impact. Like p15 and p21, TGF-β activates cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CKIs) that bind to and stop CDKs, halting the cell cycle progression. Transcription factors, including forkhead box O3 (FOXO3), specific protein 1 (SP1), and Smad proteins, affect CKIs’ activation. Targeting elements that support cell growth, such as myelocytomatosis oncogene (MYC) and cell division cycle 25A (CDC25A), TGF-β also lowers cell proliferation by a complicated interaction of transcription factors and corepressors, which reduces MYC transcription. TGF-β also downregulates, inhibitor of differentiation/DNA binding 1 (ID1) and ID2, anti-apoptotic molecules that might encourage cell expansion. Among the several cell types, lymphocytes, hepatocytes, podocytes, glial cells, hematopoietic cells, and epithelial cells can be killed by TGF-β. Usually mediated by the B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) family of proteins, which control death, this impact is while downregulating anti-apoptotic members like, BCL-2 and BCL-extra large (BCL-XL), TGF-β can boost the expression of pro-apoptotic BCL-2 family members. TGF-β and cell death do, however, have a complex interaction. TGF-β occasionally seems to encourage cell survival. This relies on the particular type of cell, other signaling systems’ activity, and the cellular surroundings’ general background [56,66].

6.3. Immunity homeostasis

TGF-β controls the immune system through several roles. It alters proliferation, cell differentiation, and immunological reactions. TGF-β increases tumor immunosuppression and reduces T-lymphocyte proliferation and thymocyte development. Moreover, TGF-β is crucial in forming regulatory T cells (Tregs), fostering immunological tolerance, and preventing autoimmune disorders. TGF-β mainly suppresses the immune system, but its influence is not clear. Along with other cytokines, TGF-β can help proinflammatory T helper type 17 (TH17) cells – which link to autoimmune diseases – develop. This dual function highlights how context-dependent TGF-β is in influencing immune responses. Usually via the Smad2/3 pathway, TGF-β mostly influences immune response gene expression. It also reduces immunity by thereby inhibiting immune cell effector functions. Besides regulating developed immunological reactions, TGF-β is vital for the immune system’s growth [67,68].

7. Role of TGF-β in DKD

Studies using single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) have provided a thorough understanding of cell-specific expression patterns, providing vital data on the role of TGF beta in the pathogenesis of DKD. They were mostly found in mesangial cells, podocytes, and proximal tubular cells. TGF-β1 is expressed in increased ECM deposition and glomerulosclerosis, indicative of DKD progression. In case of worsening proteinuria, TGF-β1 in podocytes causes cytoskeletal reorganization and foot process effacement. Increased TGF-β1 levels seen in proximal tubular cells help induce epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and tubulointerstitial fibrosis, aggravating tubular damage. Also expressed in mesangial and endothelial cells is TGF-β2. Higher TGF-β2 levels in endothelial cells have been linked to capillary filtration and endothelial dysfunction, which compromise glomerular filtration. Together with TGF-β1, TGF-β2 increases the fibrotic reactions in mesangial cells. Although present in fewer amounts, TGF-β3 is detectable in distal tubular cells and interstitial fibroblasts, which helps to enable structural remodeling and interstitial fibrosis in later stages of DKD (DKD) [27,69,70].

Autophagy, a basic cellular function, breaks down and recycles many materials inside the cytoplasm – including organelles and big molecules – through lysosomal pathways. Macroautophagy, microautophagy, and chaperone-mediated autophagy are three types of autophagy. Of these, macroautophagy has attracted the greatest investigation. Autophagy has been shown to be under the control of TGF-β1, a cytokine fundamental to kidney fibrosis. In the framework of tubulointerstitial fibrosis, glomerulosclerosis, and diabetic nephropathy (DN), this management is crucial. By means of both Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways, which involve multiple signaling molecules, including PI3K/Akt and MAPKs, TGF-β1 can induce autophagy. TGF-β1-induced type I collagen breaks down during autophagy in mesangial cells, therefore negatively regulating matrix formation and possibly decreasing fibrosis. In tubular epithelial cells, the induction of autophagy by TGF-β1 is connected to cell survival and acts as a defensive mechanism against death. Nevertheless, the participation of autophagy in fibrosis is complex and dependent on the situation since there is evidence showing both defensive and stimulating effects on fibrogenesis. The formulation of therapeutic strategies for treating renal fibrosis depends on an understanding of the twofold roles of TGF-β1 in driving both collagen synthesis and autophagy [71].

7.1. Stimulation of ECM production

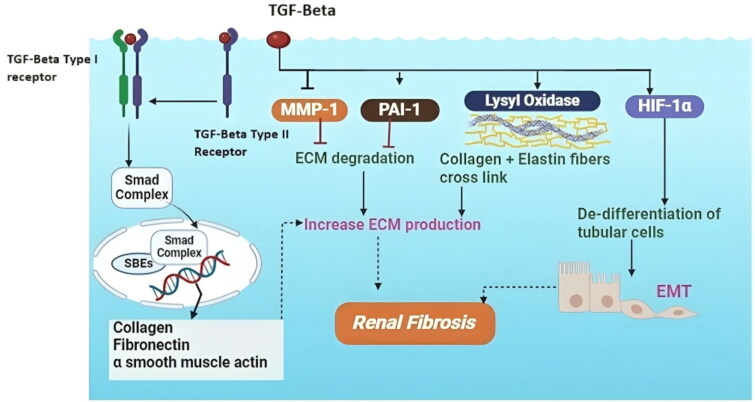

Diabetes patients with high blood glucose levels cause their kidney cells to produce excess TGF-β. The synthesis of ECM collagen and other proteins is then increased by a signaling cascade in which this molecule sets off the glomerular basement membrane, a filtration barrier that prevents waste from exiting the circulation, becomes firmer as a result of unregulated ECM formation, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Activation of TGF-β due to extracellular matrix production.

Furthermore, interfering with filtration is the mesangium enlargement in the glomerulus caused by the buildup of the ECM. Renal function is progressively compromised by this condition, called tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Because TGF-β affects ECM formation, kidney tissue hardens and scars, two hallmarks of DN. Fibrosis results in excessive fibronectin and collagen synthesis. This process depends on TGF-β since it increases the synthesis of ECM proteins. ECM deposition is enhanced by the overexpression of this gene, resulting in the disruption of tissue formation and function. By blocking matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), TGF-β also helps TIMPs develop, thereby preventing the destruction of the ECM. Because of differences in ECM synthesis and breakdown, ECM buildup increases tissue stiffness and fibrosis. Elastin and collagen cross-link to speed up ECM synthesis. TGF-β increases the function of lipoxygenase (LOX) and lysyl oxidase (LOXL), two enzymes that help to bind collagen. This enhanced cross-linking stiffens the ECM, strengthening its resistance to breakdown. Furthermore, via the EMT and EndMT pathways, excessive TGF-β stimulation reverses the specialized characteristics of proximal tubular and endothelial cells. Fibrosis results from the absence of some cell features in epithelial and endothelial cells as well as from the acquisition of mesenchymal cells [72–74] (Figure 2).

7.2. Induction of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

Diabetes-related high glucose levels cause renal epithelial cells – more especially those lining the tubules – to synthesize excessive amounts of TGF-β. Selective reabsorption in the tubules is made possible by densely packed epithelial cells. On their surface, they have unique proteins that help them connect and communicate with nearby cells. In contrast, mesenchymal cells release substantial amounts of ECM components, including collagen, and show migratory activity. Smads are activated by TGF-β; these proteins subsequently translocate into the nucleus and prevent the generation of epithelial adhesion proteins. Moreover, it increases mesenchymal marker production. Changes caused by molecular reprogramming cause epithelial cells to lose their tight connections and cobblestone-like shape and to acquire a more spindle-shaped and motile phenotype. They start synthesizing proteins known as ECM, which upsets the delicate balance between barrier function and reabsorption in the tubules. The EMT is a component of tubulointerstitial fibrosis, which is characterized by an overabundance of ECM. The tissue stiffens as a result, which interferes with its usual operation. Scar tissue and kidney stiffness are the outcomes of TGF-β-driven EMT and overproduction of ECM [75,76].

7.3. Activation of pro-fibrotic signaling pathways

Smad proteins phosphorylate and enter the nucleus after liganding to TGF-β receptors. They interact with coactivators and DNA to turn on genes that promote the synthesis of ECM components. Another important pathway is the MAPK pathway. Fibrosis-promoting genes are therefore expressed more strongly when TGF-β activates MAPKs such as ERK and p38. Furthermore, TGF-β can strengthen the fibrotic response by interacting with other signaling pathways, including the Notch, PI3K/Akt, and Wnt/β-catenin pathways. The profibrotic effects of TGF-β in DKD are coordinated by a complex network of signaling cascades. Glomerular basement membrane thickening, a filtration barrier in the kidneys that prevents waste products from being eliminated, is the consequence of increased synthesis of ECM proteins. The ECM builds inside the tubules, stiffens the tissue and upsets the delicate balance between secretion and reabsorption, thereby impairing function [77,78].

7.4. Enhancement of inflammatory responses

The interaction between TGF-β1 and interleukin (IL)-6 reveals the close equilibrium between inflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects. TGF-β1 attracts macrophages and other inflammatory cells, thereby augmenting the inflammatory response in a self-sustaining cycle. Commonly referred to as an anti-inflammatory agent, TGF-β1 plays several roles in particular settings. By promoting inflammation, IL-6 inhibits this equilibrium and causes glomerulosclerosis and interstitial fibrosis in DN. Chronic inflammation caused by TGF-β1 throws kidney function off and causes podocyte failure, increases glomerular basement membrane permeability, and increases protein levels in the urine. This process occurs in tubulointerstitial fibrosis. When released by drives T helper 17 (Th17) cells, IL-17 increases neutrophil generation and accumulation, hence aggravating inflammation. TGF-β1 stimulates NF-κB, a main inflammatory control mechanism, thereby promoting inflammation. Thus, proinflammatory molecules, including TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1, are generated. Activating immune cells and producing ROS damages kidney tissue. TGF-β1 increases IL-6 levels and Th17 cell proliferation in type 2 diabetes (T2D), hence exacerbating inflammation [77,79].

8. Diagnostic potential

TGF-β has many detrimental effects on podocytes in the pathophysiology of DKD. It generates an ECM that induces a shift in gene expression that results in dedifferentiation and causes podocytes to cease functioning through processes that promote apoptosis. This causes podocyte foot processes to become effaced and glomerular permeability to increase. TGF-β also reduces podocyte migration, therefore preventing the glomerular repair process. Regardless of whether albuminuria exists, these mechanisms cause podocyte death and glomerular sclerosis to develop. In addition to influencing podocytes, TGF-β damages tubular epithelial cells, promotes the formation of mesangial cells, and influences immunological reactions. Although albuminuria is a good sign, the absence of albumin in the urine does not always indicate that DKD has not progressed. The complicated nature of the action of TGF-β emphasizes the need to assess its diagnostic power. Some of these studies are summarized in Table 1 [79].

Table 1.

TGF-β as a diagnostic target in DKD.

| S. no. | Study | Year | Objective | Sample | Sample size | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Shaker et al. [80] | 2014 | To investigate TGF-β1 levels in T2DM patients with and without nephropathy | Urine and blood | 102 | TGF-β was found to be positively correlated with nephropathy |

| 2. | Shukla and coworkers [81] | 2018 | To study sera level of TGF-β1 in DKD patients of T2DM | Blood | 75 | Patients with T2DM demonstrated greater serum TGF-β1 levels. Furthermore, TGF-β1 levels were significantly raised in T2DM individuals with nephropathy relative to those without. |

| 3. | Pertseva et al. [82] | 2019 | To observe TGF-β1 and VCAM-1 levels in DK patients of type 1 and 2 diabetes | Blood | 124 | TGF-β 1 was found to be better diagnostic marker than VCAM-1 |

| 4. | Saeed Abbas and coworkers [83] | 2022 | To analyze the diagnostic potential of TGF-β in T2DM DKD patients | Blood | 120 | TGF-β was found significantly higher in DKD patients than healthy volunteers |

| 5. | Mezher et al. [84] | 2023 | To observe levels of IL-17a, 18 and TGF-β levels in DKD patients | Blood | 60 | The cytokines gave statistically significant results in prognosing DKD |

| 6. | Kulkarni et al. [85] | 2023 | To study the urinary TGF-β1 levels in DKD patients | Urine | 20 | Urinary TGF-β1 levels were found to be significantly higher in DKD patients than volunteers |

The diagnostic accuracy of urine and serum TGF-β1 as markers for DKD in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). One study tested the TGF-β1 levels in the urine and serum samples of 72 diabetic patients with varying degrees of nephropathy (normoalbuminuria, microalbuminuria, and macroalbuminuria), as well as in a control group of healthy people. Compared to those in the control group, all diabetic groups exhibited noticeably increased levels of urine and serum TGF-β1. The group with the most significant increase was the macroalbuminuria group. Particularly in the groups with more severe kidney illness (those with macroalbuminuria and microalbuminuria), the levels of TGF-β1 in the urine and serum as well as the concentration of total protein in the urine showed a strong positive correlation. Urinary and serum TGF-β1 levels not only increase in DN patients but also possibly correlate with the severity of the disorder. This finding implies that, together with conventional markers such as urine protein, these markers could be useful guides for disease diagnosis [80].

The researchers recruited 75 people and divided them into three groups: patients with T2DM but without DKD, patients with T2DM and DKD, and healthy people free of any medical conditions. The urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) of the DN group was significantly greater than that of both the control group, which consisted of healthy individuals without any medical conditions, and the non-DKD T2DM group, which included patients with T2DM but without DKD. Both groups with T2DM had higher blood TGF-β1 levels than the control group, with the T2DM group without nephropathy having a mean level of 17.98 ± 5.88 ng/ml and the T2DM group with DKD having a substantially higher mean level of 44.73 ± 18.45 ng/ml. A positive correlation exists between serum TGF-β1 levels and poor glycemic management (HbA1c, fasting/postprandial glucose) and renal function (serum creatinine, urine ACR). Conversely, eGFR was adversely linked with serum TGFβ1 levels. Research indicates that serum TGF-β1 can serve as a marker for DKD in T2DM patients. Moreover, the levels of serum TGF-β1 were positively correlated with indicators of poor glycemic control (HbA1c, fasting/postprandial glucose) and renal function (serum creatinine, urine ACR) and negatively correlated with the eGFR, suggesting that serum TGF-β1 levels can reveal the degree of glycemic control and the severity of the illness. Nevertheless, the study revealed no relationship between blood TGF-β1 levels and diabetes duration [81].

A study led by Pertseva et al. investigated how well TGF-β1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) might be used as blood biomarkers for DKD in patients diagnosed with type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes, respectively. There were 124 participants – those with diabetes and varying degrees of renal function – as well as a group of healthy people for comparison. Diabetic individuals show higher TGF-β1 and VCAM-1 levels than those of healthy controls. The values of both indices rose gradually as kidney function dropped. People with type 1 diabetes especially exhibited reduced TGF-β1 levels compared to those with T2D. The study found a negative link between TGF-β1/VCAM-1 and kidney function (eGFR), whereas it revealed a positive correlation between albuminuria, a sign of kidney injury. Both TGF-β1 and VCAM-1 show amazing potential as biomarkers depending on the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). With a flawless AUC of 1.0 for differentiating patients with DKD from healthy controls, independent of the type of diabetes, TGF-β1 specifically showed extraordinary diagnostic power. Measuring TGF-β1 and VCAM-1 levels in the blood could thus be a useful early approach for identifying DKD in diabetic patients [82].

This paper examined the possibility of serum TGF-β as a biomarker for early-stage DN in patients with T2DM. Based on their ACR, the 120 participants in the case-control study comprised 60 patients with T2DM split into normoalbuminuric, microalbuminuric, and macroalbuminuric groups as well as a control group of healthy people. Greater serum TGF-β levels were displayed by the T2DM groups than by the control one. Normal albuminuria had the lowest values; microalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria followed in order of lowest values as albuminuria progressed. Furthermore, whereas TGF-β levels are negatively connected to kidney function (eGFR), those levels directly correlate with indicators of renal failure like urea and ACR. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis revealed that TGF-β is a promising biomarker for early DN detection. At a given set threshold value, it has outstanding sensitivity (80%), specificity (95%), and general accuracy (83%). The findings show that higher levels of TGF-β in the blood could be connected to the beginning and development of DKD in persons with T2DM and might be utilized as a possible tool for identifying this condition at an early stage [83].

This research investigated the serum levels of TGF-β, IL-18, IL-17a, and other cytokines in Iraqi people with DKD. From October 2022 to January 2023, the research was conducted at Tikrit Teaching Hospital in the Salahaddin Governorate. Sixty blood samples were obtained from patients with diabetic renal disease. Using ELISA, the samples were subjected to analysis of the TGF-β, IL-18, and IL-17a markers. The investigation revealed significant differences (p < .05) among certain age categories within the clinical population. With 28% and 33%, respectively, people between 51 and 60 years of age and above 60 years of age scored highest. With corresponding scores of 8.3% and 13.3%, the 21–30 and 31–40 age groups, respectively, displayed noticeably lower marks. According to Pearson’s correlation analysis, patients (200.30 ± 59.50, 102.13 ± 50.82, and 57.15 ± 18.90) had greater levels of IL-18, IL-17a, and TGF-β than did healthy people (104.50 ± 31.01, 42.90 ± 10.55, and 31.90 TGF-β) (r = −0.270* Sig. = 0.037). For spotting patients with DKD, the IL-18, IL-17a, and TGF-β markers exhibited the highest sensitivity (98%, 96%, and 87%, respectively) and specificity (94%, 97%, and 80%, respectively). Statistics indicate that disease severity increases with age. During screening, the reliable markers for predicting DKD patient outcomes are IL-18, IL-17a, and TGF-β. Treating DKD could involve targeting these cytokines [84].

Another study attempted to evaluate the feasibility of urine TGF-β1 as a DKD diagnostic marker. A total of 10 patients with DKD and 10 healthy people were included in the control group. Compared to the control group (mean 29.03 ± 3.23 ng/24 h), the DKD group showed a statistically significant increase in urine TGF-β1 levels (mean 88.33 ± 12.44 ng/24 h). Although the DKD group had higher levels than did the control group, there was no clear correlation between the levels of TGF-β1 in the urine and other indices of renal function (eGFR) or glycemic control (HbA1c). These data show that patients with DKD – approximately 88.33 ng/24 h – may have higher urine TGF-β1 levels. These values might not, however, fairly represent the degree of blood sugar control or kidney function degradation. More studies are required to understand how urine TGF-β1 is related to the development of DKD [85].

9. Therapeutic potential of TGF-β

The therapeutic efficacy of TGF-β has also been studied, as summarized in Table 2. Baricitinib, an oral, reversible, selective inhibitor of Janus kinase 1 (JAK1) and JAK2, which play crucial roles in the JAK-STAT/TGF-β signaling pathway, a key mediator of inflammation in DKD. This phase 2, double-blind, dose-ranging study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of baricitinib on albuminuria in adults with T2D at high risk for DKD progression. A total of 129 participants were randomized to receive either placebo or varying doses of baricitinib (0.75–4 mg daily) for 24 weeks, followed by a washout period. The primary outcome, change in first morning urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR), demonstrated a significant reduction of 41% in the 4 mg daily group compared to placebo (p = .022). Additionally, baricitinib treatment led to decreased inflammatory biomarkers, although anemia was more frequently reported in the high-dose group, indicating a need for careful monitoring of adverse effects [86,87].

Table 2.

TGF-β as a therapeutic target in DKD.

| S. no. | Study | Year | Molecule | Target | Model | Administrated compound/vector | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Tuttle et al. [86,87] | 2018 | Baricitinib | JAK1 and JAK2 pathway | Type 2 diabetes patients with high risk of progressive DKD | 0.75 mg once daily, 0.75 mg twice daily, 1.5 mg once daily or 4 mg once daily | UACR decreased at weeks 12 and 24 and after 4–8 weeks of washout. Baricitinib 4 mg decreased inflammatory biomarkers over 24 weeks |

| 2. | Sun et al. [88] | 2020 | Fenofibrate | TGF-β1/smad3 and canonical Wnt pathways | Type 2 diabetic patients with microalbuminuria and hypertriglyceridemia | 200 mg OD | The study found that fenofibrate significantly reduced microalbuminuria and improved lipid levels (triglycerides and HDL-C) in type 2 diabetes patients with hypertriglyceridemia after 180 days of treatment. |

| 3. | Du et al. [89] | 2020 | Butyrate | Mesangial cells (miR-7a-5p/P311/TGF-β1 pathway) | Male db/db and db/m mice | 1 g/kg/day (sodium butyrate) | Butyrate supplementation alleviated the fibrosis in the kidney. |

| 4. | Zhou et al. [90] | 2021 | Tangshen formula | Tubulointerstitium | STZ-induced male Wistar rats; HK2 cell line | 1.2 g/kg/day | Following TSF treatment, rats suffering with DKD exhibited improved renal histology and reduced urine protein. TSF lowered fibrotic marker expression to stop collagen accumulation. |

| 5. | Wu et al. [91] | 2021 | Latent TGF-β1 | Tubulointerstitium (Arkadia/Smad7 signaling) | Transgenic TGF-β1 producing STZ-induced mice; recombinant human TGF-β protein cell cultures | – | Increased expression of latent TGF-β1 protected mice against the development of mesangial matrix expansion and thickening of the glomerular basement membrane was prevented. |

| 6. | Li et al. [92] | 2022 | Kirenol | TGF-β/Smads and the NF-κB signaling pathway | C57BL/6J male mice; mesangial cells | 2 mg/kg/day | Kirenol’s usage reduced Smad2/3’s phosphorylation as well as NF-κB’s kirenol reduces the TGF-β/Smads and NF-κB signaling pathways to thus minimize diabetic nephropathy. |

| 7. | Li et al. [93] | 2022 | miRNA-10 a/b | TGF-β receptor 1 | Renal biopsy samples; STZ-induced male C57BL/6J mice | Recombinant lentiviral vector pGLV-harboring miR-10a/b mimic or antisense | Reducing NLRP allowed miR-10a/b to be overexpressed, therefore addressing kidney fibrosis and inflammation. Direct targeting of TGFBR1 and control of TGF-β/Smad signaling will help to regulate renal fibrosis in diabetes mellitus. |

| 8. | Song et al. [94] | 2022 | Sestrin 2 | Podocyte (TSP-1/TGF-β1/Smad3 pathway) | Mouse podocytes; STZ-induced transgenic mice from C57BL/6J model | Recombinant mouse γ-interferon 10 U/ml | In diabetic rats, Sestrin2 lowered high levels of 24-hour urinary protein, blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, and triglyceride as well as urine 8-OHdG. The glomeruli of diabetic TgN mice also showed inhibition of the TSP-1/TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling pathway. |

| 9. | Ren et al. [95] | 2022 | Triptolide | Podocytes (kindlin-2 and EMT-related TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway) | Mice (male C57BL/Ksjs db/m normal and db/db diabetic mice aged 8 weeks) | 50 and 75 μg/kg/day | Triptolide treatment corrected functional impairments in diabetic mice and reduced structural damage. In diabetic mice, it lowered the expression of α-SMA and raised the levels of nephrin, podocin, and E-cadherin. In diabetic kidneys, triptolide treatment lowered the protein and mRNA levels of TGF-β1, p-SMAD3, and kindlin-2. |

| 10. | Song et al. [96] | 2023 | Bone morphogenic protein (BMP-7) | Smad signaling pathway and ferroptosis | Male C57BL/6 mice | 10 μg/72 h | Protein transduction domain (PTD)-fused BMP7 in micelles reduced kidney cells ferroptosis, decreased lipid peroxidation levels and improved glutathione levels in the kidneys. |

| 11 | Wang et al. [97] | 2023 | MAGI2 | Podocytes (TGF-β-Smad3/nephrin pathway) | Cell (kidney cells, human podocyte cell line of MPC5); Mice (male BKS.Cg-m+/+ Leprdb/J (db/db)) |

5 × 109 PFU of MAGI2 plasmid | Restoring MAGI2 improved kidney performance as well as limited podocyte death. |

Fenofibrate, a proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) agonist, has been shown to modulate TGF-β signaling, which plays a critical role in renal fibrosis and DN. By activating PPARα, fenofibrate can inhibit the expression of TGF-β and its downstream effects, thereby reducing inflammation and fibrosis in renal tissues. This study investigated the impact of fenofibrate on microalbuminuria in 56 patients with T2DM and hypertriglyceridemia over a 180-day period. Participants were randomly assigned to either a fenofibrate treatment group or a control group. Key results demonstrated that fenofibrate significantly decreased UACR, triglycerides (TGs), and uric acid (UA) levels, while increasing high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C). Furthermore, the reduction in UACR was positively correlated with decreases in TG and UA, suggesting that fenofibrate not only improves lipid profiles but also mitigates renal injury through the modulation of TGF-β signaling pathways, highlighting its potential therapeutic role in DN [88].

In this study, a short-chain fatty acid called butyrate was linked to possible protective effects. Butyrate has been shown to reduce fibrosis and stop the production of proteins, including P311 and TGF-β1, in diabetic mouse kidneys and in cells exposed to high glucose. Analysis further revealed a unique route (miR-7a-5p/P311/TGF-β1) that might be responsible for this beneficial effect. This pathway appears to involve a microRNA (miR-7a-5p) that targets P311. By reducing the synthesis of TGF-β1 and P311, fibrosis is eventually reduced. These results highlight the potential for regulating this pathway as a DKD therapy method; preclinical models indicate that adding butyrate may be a workable alternative [90,91]. The effectiveness of the traditional Chinese medication Tangshen formula (TSF) in reducing kidney fibrosis associated with DKD was investigated in this study. Both human kidney cells – especially human kidney 2 (HK2) cells – and rats were examined for the effects of TSF. In rats with DKD, TSF therapy notably decreased kidney damage compared with that in the control group. This was clearly shown by lower proteinuria and better tissue conditions. Mechanistically, TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling pathway and the expression of the long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) MEG3 could be influenced. TGF-β1 levels dropped; a crucial protein in the system was not phosphorylated; and lncRNA MEG3 was downregulated in rats upon TSF administration. In HK2 cells treated with high glucose, TSF administration also effectively compensated the rise in collagen synthesis and decrease in Smad3 phosphorylation to help to reduce DKD. These findings indicated that TSF may cure DKD by suppressing the TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling pathway and lncRNA MEG3 expression, hence lowering kidney fibrosis [90].

The GF TGF-β1 is often linked to aberrant levels of DKD. A new study suggests that one particular form of TGF-β1, latent TGF-β1, may be protective. Tests using genetically engineered mice showed that higher degrees of latent TGF-β1 protected the kidneys from damage caused by DKD. The two indicators of the protective effect were lower excretion of albumin in the urine (microalbuminuria) and reduced kidney scarring (fibrosis); blood glucose levels were not changed. Further investigation revealed that the suppression of Arkadia, a protein typically responsible for the degradation of another protein (Smad7), was the source of this positive effect. Smad7 suppresses the activation of detrimental signaling pathways connected to DKD development. These findings imply that as a DKD therapeutic approach, targeting the latent TGF-β1/Arkadia/Smad7 pathway could be beneficial [91].

In another study, researchers investigated the potential of kirenol as a DKD therapeutic agent. The effects of kirenol on two significant signaling pathways that are known to be involved in the development of DN were examined: the NF-κB pathway and the TGF-β/Smad pathway. They studied cell cultures as well as animal models. Giving kirenol caused the activity of several pathways to drop, which had several benefits. These comprised lowering of the expression of inflammatory markers, restoration of the levels of the protective protein IκBα, and declining synthesis of fibrosis-related proteins. Kirenol also reduced the thickening of the glomerular basement membrane, a structure in the kidney in charge of filtration, and stopped the fusion of two structures necessary for ensuring the greatest potential kidney function. These results imply that since kirenol may regulate these channels, it is a feasible treatment drug for DKD [92].

In this study, microRNA-10a and -10b (miR-10a/b) were found to be possible targets for thwarting this process. Blockers known to be engaged in the DKD-related signaling pathway (TGF-β/Smad) these microRNAs serve. Previous research revealed that TGFBR1, a crucial protein receptor linked in this process abnormally raised in DKD, is especially targeted to attain this control. Furthermore, proven by scientists to influence miR-10a/b development is a protein called XRN2. Especially in patients with DKD, lowered levels of miR-10a/b were associated with higher TGFBR1 levels and fibrosis. These findings imply that raising the expression of miR-10a/b could be one potential fibrosis treatment in DKD [93].

Low levels of the sestrin2 protein have been linked in studies to protect people with DKD from their effects. High blood glucose levels are a trademark of diabetes; podocytes can be damaged, and studies have indicated that increasing Sestrin2 expression helps prevent this damage. One particular signaling pathway (TSP-1/TGF-β1/Smad3) known to be linked in the development of DKD seems to be responsible for the observed protective effect. Sestrin2 could interfere with this process and help to lower podocyte damage. These results offer a fresh treatment approach to treat podocyte damage in DKD by stressing the possibility of raising Sestrin2 expression [94].

A recent study sought to ascertain whether podocyte EMT process inhibition by traditional Chinese medicine triptolide might lower DKD. Given to diabetic rats, triptolide yielded remarkable effects. Triptolide enhanced overall renal function and may have preserved podocytes. Triptolide’s ability to block a specific route connected to EMT points to a likely mechanism for this protective action. Reduced protein and mRNA levels related to EMT, including those of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), and enhanced levels of proteins connected to appropriate podocyte function, including nephrin, podocin, and E-cadherin, were identified. Moreover, triptolide reduced Kindlin-2 and TGF-β/Smad signaling pathways in line with EMT development. These findings imply that the use of triptolide could be a beneficial strategy for podocyte protection during DKD by means of certain pathways [95].

The loss of podocytes – specialized cells required for the glomerular filtration barrier (GFB) – defines DKD. Frequent in podocytes, studies point to a protective function for the protein membrane-associated guanylate kinase inverted 2 (MAGI2). Studies have indicated that MAGI2 levels drop in surroundings with high glucose levels as well as in patients with DKD. Fascinatingly, podocytes seem to be spared death by engaging with a particular pathway known as the TGF-β-Smad3/nephrin pathway, which increases MAGI2 production. Moreover, data supporting this idea came from animal models in which raising MAGI2 levels enhanced podocyte protection and kidney function in diabetic mice. These findings imply that a suitable DKD therapy approach could be MAGI2 expression modification [97].

10. Challenges for TGF-β inhibitor

Modulating TGF-β, rather than directly blocking TGF-β ligands/receptors, may be a good antifibrosis strategy based on experimental and clinical data for DKD. TGF-β stimulates autophagy, tissue regeneration, anti-inflammation, and healing of wounds. Still, the dosage schedule has to be taken very seriously since in animal studies a high dosage of TGF-β inhibition produced severe toxicity and low efficacy. More importantly, a possible therapeutic would involve creating molecules that prevent latent TGF-β1 from activating itself. Since TGF-β plays a prominent role in the pathophysiology of DKD, the TGF-β system is a desirable target to slow down the development of DKD, provided that the strategy preserves a reasonable balance between reno-protective and negative consequences [98,99].

11. Molecules other than TGF-β

TGF-β occupies a central position in the pathogenesis of fibrosis, and kidney disease, orchestrating cellular responses that drive tissue remodeling and dysfunction. However, these complex pathologies are not solely the domain of TGF-β. A diverse cast of cytokines and GFs, including connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), interleukin-6 (IL-6), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and TNF-α, significantly contribute to disease progression through distinct and often intertwined mechanisms.

11.1. CTGF

CTGF is a key factor in developing DKD as a downstream effector of TGF-β. TGF-β and CTGF interact to cause renal fibrosis. TGF-β induces CTGF expression by means of the Smad3 pathway, therefore, promoting ECM accumulation and EMT. Specifically, the JNK axis, the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway raises CTGF mRNA expression, therefore, aggravating this process. By boosting TGF-β-mediated fibrotic responses, CTGF creates a positive feedback loop that speeds fibrogenesis. Studies have shown that renal tissue CTGF overexpression correlates with fibrosis and DKD development. CTGF’s diagnostic potential is similar to TGF-β in detecting fibrotic activity. CTGF focuses on ECM remodeling, making it a powerful target for antifibrotic therapy. CTGF levels in urine and plasma may be indicators for early DKD identification, adding diagnostic value [100–102].

11.2. IL-6

IL-6, a multifunctional cytokine implicated in inflammation, immunological control, and fibrosis, accelerates DKD. IL-6, which is elevated in diabetes, induces the production of TGF-β. TGF-β then increases inflammation and encourages the synthesis of ECM proteins, therefore, causing kidney injury and scarring. IL-6 and TGF-β interact to produce a vicious cycle that speeds DKD’s development. Further, IL-6 activates STAT3 to promote mesangial cell proliferation, ECM deposition, and tubular damage. IL-6 focuses on inflammatory and immunological responses. DKD severity is linked to high IL-6 levels, and anti-IL-6 medications such as tocilizumab are being studied for renal inflammation reduction. IL-6 can be used as a biomarker for illness progression, supplementing TGF-β in identifying patients at risk of rapid deterioration. Targeting IL-6 pathways may complement antifibrotic medicines targeting TGF-β signaling [103–105].

11.3. MCP-1

MCP-1, a chemokine, and TGF-β interact to drive DKD progression. MCP-1 attracts monocytes that become macrophages, which then release TGF-β. TGF-β promotes fibrosis, leading to kidney scarring and dysfunction. MCP-1 is crucial for immune cell recruitment and inflammation. Urinary MCP-1 levels increase with DKD severity, suggesting a disease monitoring biomarker. Therapy targeting MCP-1 or its receptor (CCR2) may reduce renal inflammation and postpone disease progression [106–108].

11.4. PDGF

In DKD, mitogenic cytokine PDGF increases mesangial cell proliferation, ECM buildup, and vascular remodeling. In DKD, TGF-β and PDGF interact to promote fibrosis. TGF-β increases PDGF expression, leading to mesangial cell growth and ECM buildup. TGF-β’s fibrogenic responses are exacerbated by PDGF signaling, notably through PDGFR-β, leading to increased kidney damage. Furthermore, both GFs impact endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis, which are linked to shared signaling pathways such as PI3K/Akt, MAPK, and JAK/STAT. Early DKD causes glomerular hypertrophy and sclerosis due to PDGF signaling. PDGF plays a role in cellular proliferation and vascular damage. PDGF targets glomerular cell growth more specifically. PDGF inhibitors are being explored for antifibrotic effects since high PDGF levels in renal tissues and plasma are linked to DKD progression [109–112].

11.5. TNF-alpha

The pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α worsens renal injury in DKD by causing oxidative stress, inflammation, and death in renal cells. The GFB is disrupted by TNF-α, leading to proteinuria and tubular damage. While TGF-β predominantly contributes to fibrosis, TNF-α is primarily engaged in acute inflammatory reactions and vascular damage. TNF-α actually is also part of the precursors leading to TGF-β overproduction. High plasma and urine TNF-α levels are linked to DKD severity, and infliximab, a TNF-α inhibitor, shows promise in preclinical models. TNF-α, which targets inflammatory pathways, plays a role in disease progression alongside TGF-β, providing an additional therapeutic approach for DKD therapy [113–116].

12. Conclusions

The human body’s signaling molecule TGF-β controls a variety of cellular functions, such as a conductor. Being ubiquitous in practically all cell types, it is essential for growth, development, repair, and even the immune system. High blood glucose levels, however, cause an overproduction of TGF-β and consequently an overproduction of scar tissue in DKD patients. With this scar tissue, which also reduces the capacity to efficiently filter waste chemicals, the kidneys grow less functional. The dual character of this process makes it difficult to block TGF-β directly. Instead of completely inhibiting TGF-β, modifying its activities shows promise in slowing the progression of DKD with the least amount of unfavorable side effects.

Funding Statement

This review did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributions

Sushma Thimmaiah Kanakalakshmi: conceptualization, review, and supervision. Priya Rani: draft preparation and revisions. Sindhura Lakshmi Koulmane Laxminarayana: critical review and supervision. Shilna Muttickal Swaminathan: diagram conceptualization and preparation. Mohan Varadanayakanahalli Bhojaraja: conceptualization, review, and supervision. Shankar Prasad Nagaraju: conceptualization, review, and supervision. Sahana Shetty: review and supervision. The final manuscript was read and approved by all the authors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

No data were used for the research described in the article.

References

- 1.Naaman SC, Bakris GL.. Diabetic nephropathy: update on pillars of therapy slowing progression. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(9):1574–1586. doi: 10.2337/DCI23-0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alicic R, Nicholas SB.. Diabetic kidney disease back in focus: management field guide for health care professionals in the 21st century. Mayo Clin Proc. 2022;97(10):1904–1919. doi: 10.1016/J.MAYOCP.2022.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tuttle KR, Agarwal R, Alpers CE, et al. Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets for diabetic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2022;102(2):248–260. doi: 10.1016/J.KINT.2022.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ong KL, Stafford LK, McLaughlin SA, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with projections of prevalence to 2050: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet. 2023;402(10397):203–234. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01301-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faselis C, Katsimardou A, Imprialos K, et al. Microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2020;18(2):117–124. doi: 10.2174/1570161117666190502103733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alicic RZ, Rooney MT, Tuttle KR.. Diabetic kidney disease: challenges, progress, and possibilities. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(12):2032–2045. doi: 10.2215/CJN.11491116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matoba K, Takeda Y, Nagai Y, et al. Unraveling the role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of diabetic kidney disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(14):3393. doi: 10.3390/ijms20143393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Snider JT, Sullivan J, Van Eijndhoven E, et al. Lifetime benefits of early detection and treatment of diabetic kidney disease. PLOS One. 2019;14(5):e0217487. doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0217487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Diabetes Work Group . Clinical practice guideline for diabetes management in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2022;102(5S):S1–S127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jha R, Lopez-Trevino S, Kankanamalage HR, et al. Diabetes and renal complications: an overview on pathophysiology, biomarkers and therapeutic interventions. Biomedicines. 2024;12(5):1098. doi: 10.3390/BIOMEDICINES12051098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.An N, Wu BT, Yang YW, et al. Re-understanding and focusing on normoalbuminuric diabetic kidney disease. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13:1077929. doi: 10.3389/FENDO.2022.1077929/FULL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi S, Ni L, Gao L, et al. Comparison of nonalbuminuric and albuminuric diabetic kidney disease among patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13:871272. doi: 10.3389/FENDO.2022.871272/BIBTEX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scilletta S, Di Marco M, Miano N, et al. Update on diabetic kidney disease (DKD): focus on non-albuminuric DKD and cardiovascular risk. Biomolecules. 2023;13(5):752. doi: 10.3390/BIOM13050752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deng L, Li W, Xu G.. Update on pathogenesis and diagnosis flow of normoalbuminuric diabetes with renal insufficiency. Eur J Med Res. 2021;26(1):144. doi: 10.1186/S40001-021-00612-9/FIGURES/2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen C, Wang C, Hu C, et al. Normoalbuminuric diabetic kidney disease. Front Med. 2017;11(3):310–318. doi: 10.1007/S11684-017-0542-7/METRICS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prakoura N, Hadchouel J, Chatziantoniou C.. Novel targets for therapy of renal fibrosis. J Histochem Cytochem. 2019;67(9):701–715. doi: 10.1369/0022155419849386/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/10.1369_0022155419849386-FIG1.JPEG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clark DA, Coker R.. Molecules in focus transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β). Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1998;30(3):293–298. doi: 10.1016/S1357-2725(97)00128-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts AB, Anzano MA, Lamb LC, et al. New class of transforming growth factors potentiated by epidermal growth factor: isolation from non-neoplastic tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78(9):5339–5343. doi: 10.1073/PNAS.78.9.5339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santibañez JFS, Quintanilla M, Bernabeu C.. TGF-β/TGF-β receptor system and its role in physiological and pathological conditions. Clin Sci. 2011;121(6):233–251. doi: 10.1042/CS20110086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Massagué J. TGF-β signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67(1):753–791. doi: 10.1146/ANNUREV.BIOCHEM.67.1.753/CITE/REFWORKS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heldin CH, Moustakas A.. Signaling receptors for TGF-β family members. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2016;8(8):a022053. doi: 10.1101/CSHPERSPECT.A022053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poniatowski LA, Wojdasiewicz P, Gasik R, et al. Transforming growth factor beta family: insight into the role of growth factors in regulation of fracture healing biology and potential clinical applications. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015(1):137823. doi: 10.1155/2015/137823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang J, Liu F, Cooper ME, et al. Renal fibrosis as a hallmark of diabetic kidney disease: potential role of targeting transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) and related molecules. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2022;26(8):721–738. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2022.2133698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moses HL, Roberts AB, Derynck R.. The discovery and early days of TGF-β: a historical perspective. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2016;8(7):a021865. doi: 10.1101/CSHPERSPECT.A021865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jia S, Meng A.. TGFβ family signaling and development. Development. 2021;148(5):dev188490. doi: 10.1242/DEV.188490/237494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kubiczkova L, Sedlarikova L, Hajek R, et al. TGF-β – an excellent servant but a bad master. J Transl Med. 2012;10(1):183. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-183/FIGURES/4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao L, Zou Y, Liu F.. Transforming growth factor-beta1 in diabetic kidney disease. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:187. doi: 10.3389/FCELL.2020.00187/BIBTEX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun T, Huang Z, Liang WC, et al. TGFβ2 and TGFβ3 isoforms drive fibrotic disease pathogenesis. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13(605):eabe0407. doi: 10.1126/SCITRANSLMED.ABE0407/SUPPL_FILE/SCITRANSLMED.ABE0407_SM.PDF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hinck AP. Structural studies of the TGF-βs and their receptors – insights into evolution of the TGF-β superfamily. FEBS Lett. 2012;586(14):1860–1870. doi: 10.1016/J.FEBSLET.2012.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khalil N. TGF-β: from latent to active. Microbes Infect. 1999;1(15):1255–1263. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(99)00259-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyazono K, Heldin CH.. Latent forms of TGF-β: molecular structure and mechanisms of activation. Ciba Found Symp. 1991;157:81–97. doi: 10.1002/9780470514061.CH6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lawrence DA. Latent-TGF-β: an overview. Mol Cell Biochem. 2001;219(1–2):163–170. doi: 10.1023/A:1010819716023/METRICS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi M, Zhu J, Wang R, et al. Latent TGF-β structure and activation. Nature. 2011;474(7351):343–349. doi: 10.1038/nature10152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tzavlaki K, Moustakas A.. TGF-β signaling. Biomolecules. 2020;10(3):487. doi: 10.3390/BIOM10030487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aashaq S, Batool A, Mir SA, et al. TGF-β signaling: a recap of SMAD-independent and SMAD-dependent pathways. J Cell Physiol. 2022;237(1):59–85. doi: 10.1002/JCP.30529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Travis MA, Sheppard D.. TGF-β activation and function in immunity processing, secretion, and structure of TGF-β. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014;32(1):51–82. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu XY, Sun Q, Zhang YM, et al. TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway in tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:860588. doi: 10.3389/FPHAR.2022.860588/BIBTEX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li J, Zou Y, Kantapan J, et al. TGF-β/Smad signaling in chronic kidney disease: exploring post-translational regulatory perspectives (review). Mol Med Rep. 2024;30(2):143. doi: 10.3892/MMR.2024.13267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen L, Yang T, Lu DW, et al. Central role of dysregulation of TGF-β/Smad in CKD progression and potential targets of its treatment. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;101:670–681. doi: 10.1016/J.BIOPHA.2018.02.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Finnson KW, Almadani Y, Philip A.. Non-canonical (non-SMAD2/3) TGF-β signaling in fibrosis: mechanisms and targets. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2020;101:115–122. doi: 10.1016/J.SEMCDB.2019.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hariyanto NI, Yo EC, Wanandi SI.. Regulation and signaling of TGF-β autoinduction. Int J Mol Cell Med. 2021;10(4):234–247. doi: 10.22088/IJMCM.BUMS.10.4.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Montecchi-Palmer M, Bermudez JY, Webber HC, et al. TGFβ2 induces the formation of cross-linked actin networks (CLANs) in human trabecular meshwork cells through the Smad and non-Smad dependent pathways. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58(2):1288–1295. doi: 10.1167/IOVS.16-19672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gai L, Zhu Y, Zhang C, et al. Targeting canonical and non-canonical STAT signaling pathways in renal diseases. Cells. 2021;10(7):1610. doi: 10.3390/CELLS10071610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yuan Q, Tang B, Zhang C.. Signaling pathways of chronic kidney diseases, implications for therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):182. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01036-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang PMK, Zhang YY, Mak TSK, et al. Transforming growth factor-β signalling in renal fibrosis: from Smads to non-coding RNAs. J Physiol. 2018;596(16):3493–3503. doi: 10.1113/JP274492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wynn TA. Common and unique mechanisms regulate fibrosis in various fibroproliferative diseases. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(3):524–529. doi: 10.1172/JCI31487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barcellos-Hoff MH, Dix TA.. Redox-mediated activation of latent transforming growth factor-beta 1. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10(9):1077–1083. doi: 10.1210/MEND.10.9.8885242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu RM, Desai LP.. Reciprocal regulation of TGF-β and reactive oxygen species: a perverse cycle for fibrosis. Redox Biol. 2015;6:565–577. doi: 10.1016/J.REDOX.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murphy-Ullrich JE, Suto MJ.. Thrombospondin-1 regulation of latent TGF-β activation: a therapeutic target for fibrotic disease. Matrix Biol. 2018;68–69:28–43. doi: 10.1016/J.MATBIO.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murphy-Ullrich JE, Poczatek M.. Activation of latent TGF-β by thrombospondin-1: mechanisms and physiology. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2000;11(1–2):59–69. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6101(99)00029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Daniel C, Wiede J, Krutzsch HC, et al. Thrombospondin-1 is a major activator of TGF-β in fibrotic renal disease in the rat in vivo. Kidney Int. 2004;65(2):459–468. doi: 10.1111/J.1523-1755.2004.00395.X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Henderson NC, Sheppard D.. Integrin-mediated regulation of TGFβ in fibrosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832(7):891–896. doi: 10.1016/J.BBADIS.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sheppard D. Integrin-mediated activation of latent transforming growth factor β. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2005;24(3):395–402. doi: 10.1007/S10555-005-5131-6/METRICS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nishimura SL. Integrin-mediated transforming growth factor-β activation, a potential therapeutic target in fibrogenic disorders. Am J Pathol. 2009;175(4):1362–1370. doi: 10.2353/AJPATH.2009.090393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sureshbabu A, Muhsin SA, Choi ME.. TGF-β signaling in the kidney: profibrotic and protective effects. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;310(7):F596–F606. doi: 10.1152/AJPRENAL.00365.2015/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/ZH20061678230003.JPEG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Deng Z, Fan T, Xiao C, et al. TGF-β signaling in health, disease and therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):61. doi: 10.1038/s41392-024-01764-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mustoe TA, Pierce GF, Thomason A, et al. Accelerated healing of incisional wounds in rats induced by transforming growth factor-beta. Science. 1987;237(4820):1333–1336. doi: 10.1126/SCIENCE.2442813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zelisko N, Lesyk R, Stoika R.. Structure, unique biological properties, and mechanisms of action of transforming growth factor β. Bioorg Chem. 2024;150:107611. doi: 10.1016/J.BIOORG.2024.107611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zheng SY, Wan XX, Kambey PA, et al. Therapeutic role of growth factors in treating diabetic wound. World J Diabetes. 2023;14(4):364–395. doi: 10.4239/WJD.V14.I4.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen W. TGF-β regulation of T cells keywords. Annu Rev Immunol. 2023;41(1):483–512. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-101921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]